User login

FDA approves Baqsimi nasal powder for emergency hypoglycemia treatment

in patients aged 4 years and older.

Injectable glucagon has been approved in the United States for several decades.

The safety and efficacy of the Baqsimi powder was assessed in two studies with adults with diabetes and one with pediatric patients. In all three studies, a single dose of Baqsimi was compared with a single dose of glucagon injection, and Baqsimi adequately raised blood sugar levels in response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

The most common adverse events associated with Baqsimi include nausea, vomiting, headache, upper respiratory tract irritation, watery eyes, redness of eyes, and itchiness. The safety profile is similar to that of injectable glucagon, with the addition of nasal- and eye-related symptoms because of the method of delivery.

“There are many products on the market for those who need insulin, but until now, people suffering from a severe hypoglycemic episode had to be treated with a glucagon injection that first had to be mixed in a several-step process. This new way to administer glucagon may simplify the process, which can be critical during an episode, especially since the patient may have lost consciousness or may be having a seizure. In those situations, we want the process to treat the suffering person to be as simple as possible,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

in patients aged 4 years and older.

Injectable glucagon has been approved in the United States for several decades.

The safety and efficacy of the Baqsimi powder was assessed in two studies with adults with diabetes and one with pediatric patients. In all three studies, a single dose of Baqsimi was compared with a single dose of glucagon injection, and Baqsimi adequately raised blood sugar levels in response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

The most common adverse events associated with Baqsimi include nausea, vomiting, headache, upper respiratory tract irritation, watery eyes, redness of eyes, and itchiness. The safety profile is similar to that of injectable glucagon, with the addition of nasal- and eye-related symptoms because of the method of delivery.

“There are many products on the market for those who need insulin, but until now, people suffering from a severe hypoglycemic episode had to be treated with a glucagon injection that first had to be mixed in a several-step process. This new way to administer glucagon may simplify the process, which can be critical during an episode, especially since the patient may have lost consciousness or may be having a seizure. In those situations, we want the process to treat the suffering person to be as simple as possible,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

in patients aged 4 years and older.

Injectable glucagon has been approved in the United States for several decades.

The safety and efficacy of the Baqsimi powder was assessed in two studies with adults with diabetes and one with pediatric patients. In all three studies, a single dose of Baqsimi was compared with a single dose of glucagon injection, and Baqsimi adequately raised blood sugar levels in response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

The most common adverse events associated with Baqsimi include nausea, vomiting, headache, upper respiratory tract irritation, watery eyes, redness of eyes, and itchiness. The safety profile is similar to that of injectable glucagon, with the addition of nasal- and eye-related symptoms because of the method of delivery.

“There are many products on the market for those who need insulin, but until now, people suffering from a severe hypoglycemic episode had to be treated with a glucagon injection that first had to be mixed in a several-step process. This new way to administer glucagon may simplify the process, which can be critical during an episode, especially since the patient may have lost consciousness or may be having a seizure. In those situations, we want the process to treat the suffering person to be as simple as possible,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

NIH launches 5-year, $10 million study on acute flaccid myelitis

Researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham will lead a 5-year, federally-funded study of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) – a rare pediatric neurologic disease.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) awarded the $10 million grant to primary investigator David Kimberlin, MD, a UAB professor of pediatrics. Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, MD, professor of neurology and pathology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, is the co-principal investigator.

The university will organize and implement the international, multisite study. Its primary goal is to examine the incidence and distribution of AFM, and its pathogenesis and progression. Enrollment is expected to commence next fall. Investigators will enroll children with symptoms of AFM and follow them for 1 year. Household contacts of the subjects will serve as comparators.

In addition to collecting data about risk factors and disease progression, the researchers will collect clinical specimens, including blood and cerebrospinal fluid. More details about the design and study sites will be released then, according to a press statement issued by NIAID.

AFM targets spinal nerves and often develops after a mild respiratory illness. The disease mounted a global epidemic comeback in 2014, primarily affecting children; it has occurred concurrently with enterovirus outbreaks.

“Growing epidemiological evidence suggests that enterovirus-D68 [EV-D68] could play a role,” the statement noted. “Most people who become infected with EV-D68 are asymptomatic or experience mild, cold-like symptoms. Researchers and physicians are working to understand if there is a connection between these viral outbreaks and AFM, and if so, why some children but not others experience this sudden muscle weakness and paralysis.”

The study will draw on the expertise of the AFM Task Force, established last fall. The group comprises physicians, scientists, and public health experts from diverse disciplines and institutions who will assist in the ongoing investigation.

The AFM natural history study is funded under contract HHSN272201600018C.

Researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham will lead a 5-year, federally-funded study of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) – a rare pediatric neurologic disease.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) awarded the $10 million grant to primary investigator David Kimberlin, MD, a UAB professor of pediatrics. Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, MD, professor of neurology and pathology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, is the co-principal investigator.

The university will organize and implement the international, multisite study. Its primary goal is to examine the incidence and distribution of AFM, and its pathogenesis and progression. Enrollment is expected to commence next fall. Investigators will enroll children with symptoms of AFM and follow them for 1 year. Household contacts of the subjects will serve as comparators.

In addition to collecting data about risk factors and disease progression, the researchers will collect clinical specimens, including blood and cerebrospinal fluid. More details about the design and study sites will be released then, according to a press statement issued by NIAID.

AFM targets spinal nerves and often develops after a mild respiratory illness. The disease mounted a global epidemic comeback in 2014, primarily affecting children; it has occurred concurrently with enterovirus outbreaks.

“Growing epidemiological evidence suggests that enterovirus-D68 [EV-D68] could play a role,” the statement noted. “Most people who become infected with EV-D68 are asymptomatic or experience mild, cold-like symptoms. Researchers and physicians are working to understand if there is a connection between these viral outbreaks and AFM, and if so, why some children but not others experience this sudden muscle weakness and paralysis.”

The study will draw on the expertise of the AFM Task Force, established last fall. The group comprises physicians, scientists, and public health experts from diverse disciplines and institutions who will assist in the ongoing investigation.

The AFM natural history study is funded under contract HHSN272201600018C.

Researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham will lead a 5-year, federally-funded study of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) – a rare pediatric neurologic disease.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) awarded the $10 million grant to primary investigator David Kimberlin, MD, a UAB professor of pediatrics. Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, MD, professor of neurology and pathology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, is the co-principal investigator.

The university will organize and implement the international, multisite study. Its primary goal is to examine the incidence and distribution of AFM, and its pathogenesis and progression. Enrollment is expected to commence next fall. Investigators will enroll children with symptoms of AFM and follow them for 1 year. Household contacts of the subjects will serve as comparators.

In addition to collecting data about risk factors and disease progression, the researchers will collect clinical specimens, including blood and cerebrospinal fluid. More details about the design and study sites will be released then, according to a press statement issued by NIAID.

AFM targets spinal nerves and often develops after a mild respiratory illness. The disease mounted a global epidemic comeback in 2014, primarily affecting children; it has occurred concurrently with enterovirus outbreaks.

“Growing epidemiological evidence suggests that enterovirus-D68 [EV-D68] could play a role,” the statement noted. “Most people who become infected with EV-D68 are asymptomatic or experience mild, cold-like symptoms. Researchers and physicians are working to understand if there is a connection between these viral outbreaks and AFM, and if so, why some children but not others experience this sudden muscle weakness and paralysis.”

The study will draw on the expertise of the AFM Task Force, established last fall. The group comprises physicians, scientists, and public health experts from diverse disciplines and institutions who will assist in the ongoing investigation.

The AFM natural history study is funded under contract HHSN272201600018C.

Summary: American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement on concussion in sport

An estimated 1-1.8 million sport-related concussions (SRC) occur per year in patients younger than 18 years of age. Concussion is defined as “a traumatically induced transient disturbance of brain function.” More than 50% of concussions among high school youth are not related to organized sports and between 2% and 15% of athletes in organized sports will sustain a concussion during a season of play.

which will be described in this article. The guidelines include recommendations for imaging, treatment, and decision making regarding when as well as whether to return to play. Here is a brief summary of those recommendations.

Preseason: Preseason evaluation includes a preparticipation physical evaluation and discussion of concussion history as well as risk factors associated with prolonged concussion recovery. Neurocognitive tests are available for baseline evaluation. While these may assist with diagnosis and return-to-play decisions, there can be considerable variation in an individual’s baseline score as well as the possibility of changes in that baseline over time. Because of this potential for variability, these tests are not required or accepted as the standard of care.

Sideline assessment: Familiarity with the athlete is the best way to detect subtle changes in personality or performance. Looking at symptoms is still the most sensitive way to diagnose a concussion. Loss of consciousness, seizure, tonic posturing, lack of motor coordination, confusion, amnesia, difficulty with balance, or any cognitive difficulty should prompt removal from play for possible concussion. Once a potential injury is identified, how the athlete responds to the elements of orientation, memory, concentration, speech pattern, and balance should be evaluated. If an athlete has a probable or definite concussion, the athlete needs to be removed from play and cannot return to same-day play, and a more detailed evaluation needs to be done.

Office assessment: It is not unusual for symptoms and testing to normalize by the time an office visit occurs. If this is the case, the visit should focus on recommendations for safe return to school and sport. A standard office evaluation should include taking a history with details of the mechanism of injury and preexisting conditions – such as depression and prior concussion – that can affect concussion recovery. The history should focus on detecting symptoms that typically cause impairment from concussion: headache, ocular-vestibular issues leading to problems with balance, and cognitive issues with difficulty concentrating and remembering, as well as fatigue and mood issues such as anxiety, irritability, and depression. The physical exam should include assessment of ocular and vestibular function, gait, and balance in addition to a neurological exam.

Imaging: Head CT or MRI are rarely indicated. Intracranial bleeds are rare in the context of SRC but can occur. If there is concern for a bleed, then CT scan is the imaging test of choice. MRI may have value for evaluation for atypical or prolonged recovery.

Recovery time: The large majority (80%-90%) of concussed older adolescents and adults return to preinjury levels of function within 2 weeks; in younger athletes, clinical recovery may take up to 4 weeks. The best predictor of recovery from SRC is the number and severity of symptoms.

Treatment: For decades, cognitive and physical rest has been the standard of treatment. However, this is no longer the “gold standard” as it has been shown that strict rest (“cocoon therapy”) after SRC slows recovery and leads to an increased chance of prolonged symptoms. Current consensus guidelines support 24-48 hours of symptom-limited rest, both cognitive and physical, followed by a gradual increase in activity, staying below symptom-exacerbation thresholds. Activity, along with good sleep hygiene, appears to be helpful in facilitating recovery from SRC. In athletes with persistent post concussive symptoms that continue beyond the expected recovery time frame, activities of daily living, school, and exercise that do not significantly exacerbate symptoms are recommended.

Return to learning/play: A concussion can cause temporary deficits in attention, cognitive processing, short-term memory, and executive functioning. School personnel should be informed of the injury and assist in employing an individualized return to learn plan, including academic accommodations. Ultimately, return to sports activities should follow a successful return to the classroom. Return to play involves a stepwise increase in physical demands/activity without symptoms before a student is allowed to participate in full contact play.

Concussion-related risks: Continuing to participate in sports before resolution of concussion can worsen and prolong symptoms of SRC. Returning too early after concussion, before full recovery, increases the risk of recurrent SRC. During the initial post-injury period, returning to sports too early increases the risk for a rare but devastating possibility of second impact syndrome that can be a life-threatening repeat head injury. Studies of long-term mental health diagnoses are conflicting and inconsistent. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy has been described in athletes with a long history of concussions and repetitive sub-symptom head impacts. The degree of exposure needed appears to be variable and dependent on the individual.

Disqualification from play: Because each athlete is individually assessed after SRC, there are no evidence-based studies indicating how many concussions are “safe” for an athlete to have in a lifetime. The decision to stop playing sports is both serious and difficult for most athletes and requires shared decision making between clinician, the athlete, and the athlete’s parents. Factors to consider when determining if disqualification from play is warranted include:

- The total number of concussions experienced by a patient.

- Whether a patient has sustained subsequent concussions with progressively less forceful blows to the head.

- If a patient has sustained multiple concussions,whether the time to complete a full recovery after each concussion event increased.

The bottom line: “Cocoon therapy” is no longer recommended. Consensus guidelines endorse 24-48 hours of symptom-limited cognitive and physical rest followed by a gradual increase in activity, including noncontact physical activity that does not provoke symptoms.

Dr. Belogorodsky is a second-year resident and Dr. Fidler is an associate director in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

Harmon KG et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement on concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:213-25.

An estimated 1-1.8 million sport-related concussions (SRC) occur per year in patients younger than 18 years of age. Concussion is defined as “a traumatically induced transient disturbance of brain function.” More than 50% of concussions among high school youth are not related to organized sports and between 2% and 15% of athletes in organized sports will sustain a concussion during a season of play.

which will be described in this article. The guidelines include recommendations for imaging, treatment, and decision making regarding when as well as whether to return to play. Here is a brief summary of those recommendations.

Preseason: Preseason evaluation includes a preparticipation physical evaluation and discussion of concussion history as well as risk factors associated with prolonged concussion recovery. Neurocognitive tests are available for baseline evaluation. While these may assist with diagnosis and return-to-play decisions, there can be considerable variation in an individual’s baseline score as well as the possibility of changes in that baseline over time. Because of this potential for variability, these tests are not required or accepted as the standard of care.

Sideline assessment: Familiarity with the athlete is the best way to detect subtle changes in personality or performance. Looking at symptoms is still the most sensitive way to diagnose a concussion. Loss of consciousness, seizure, tonic posturing, lack of motor coordination, confusion, amnesia, difficulty with balance, or any cognitive difficulty should prompt removal from play for possible concussion. Once a potential injury is identified, how the athlete responds to the elements of orientation, memory, concentration, speech pattern, and balance should be evaluated. If an athlete has a probable or definite concussion, the athlete needs to be removed from play and cannot return to same-day play, and a more detailed evaluation needs to be done.

Office assessment: It is not unusual for symptoms and testing to normalize by the time an office visit occurs. If this is the case, the visit should focus on recommendations for safe return to school and sport. A standard office evaluation should include taking a history with details of the mechanism of injury and preexisting conditions – such as depression and prior concussion – that can affect concussion recovery. The history should focus on detecting symptoms that typically cause impairment from concussion: headache, ocular-vestibular issues leading to problems with balance, and cognitive issues with difficulty concentrating and remembering, as well as fatigue and mood issues such as anxiety, irritability, and depression. The physical exam should include assessment of ocular and vestibular function, gait, and balance in addition to a neurological exam.

Imaging: Head CT or MRI are rarely indicated. Intracranial bleeds are rare in the context of SRC but can occur. If there is concern for a bleed, then CT scan is the imaging test of choice. MRI may have value for evaluation for atypical or prolonged recovery.

Recovery time: The large majority (80%-90%) of concussed older adolescents and adults return to preinjury levels of function within 2 weeks; in younger athletes, clinical recovery may take up to 4 weeks. The best predictor of recovery from SRC is the number and severity of symptoms.

Treatment: For decades, cognitive and physical rest has been the standard of treatment. However, this is no longer the “gold standard” as it has been shown that strict rest (“cocoon therapy”) after SRC slows recovery and leads to an increased chance of prolonged symptoms. Current consensus guidelines support 24-48 hours of symptom-limited rest, both cognitive and physical, followed by a gradual increase in activity, staying below symptom-exacerbation thresholds. Activity, along with good sleep hygiene, appears to be helpful in facilitating recovery from SRC. In athletes with persistent post concussive symptoms that continue beyond the expected recovery time frame, activities of daily living, school, and exercise that do not significantly exacerbate symptoms are recommended.

Return to learning/play: A concussion can cause temporary deficits in attention, cognitive processing, short-term memory, and executive functioning. School personnel should be informed of the injury and assist in employing an individualized return to learn plan, including academic accommodations. Ultimately, return to sports activities should follow a successful return to the classroom. Return to play involves a stepwise increase in physical demands/activity without symptoms before a student is allowed to participate in full contact play.

Concussion-related risks: Continuing to participate in sports before resolution of concussion can worsen and prolong symptoms of SRC. Returning too early after concussion, before full recovery, increases the risk of recurrent SRC. During the initial post-injury period, returning to sports too early increases the risk for a rare but devastating possibility of second impact syndrome that can be a life-threatening repeat head injury. Studies of long-term mental health diagnoses are conflicting and inconsistent. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy has been described in athletes with a long history of concussions and repetitive sub-symptom head impacts. The degree of exposure needed appears to be variable and dependent on the individual.

Disqualification from play: Because each athlete is individually assessed after SRC, there are no evidence-based studies indicating how many concussions are “safe” for an athlete to have in a lifetime. The decision to stop playing sports is both serious and difficult for most athletes and requires shared decision making between clinician, the athlete, and the athlete’s parents. Factors to consider when determining if disqualification from play is warranted include:

- The total number of concussions experienced by a patient.

- Whether a patient has sustained subsequent concussions with progressively less forceful blows to the head.

- If a patient has sustained multiple concussions,whether the time to complete a full recovery after each concussion event increased.

The bottom line: “Cocoon therapy” is no longer recommended. Consensus guidelines endorse 24-48 hours of symptom-limited cognitive and physical rest followed by a gradual increase in activity, including noncontact physical activity that does not provoke symptoms.

Dr. Belogorodsky is a second-year resident and Dr. Fidler is an associate director in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

Harmon KG et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement on concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:213-25.

An estimated 1-1.8 million sport-related concussions (SRC) occur per year in patients younger than 18 years of age. Concussion is defined as “a traumatically induced transient disturbance of brain function.” More than 50% of concussions among high school youth are not related to organized sports and between 2% and 15% of athletes in organized sports will sustain a concussion during a season of play.

which will be described in this article. The guidelines include recommendations for imaging, treatment, and decision making regarding when as well as whether to return to play. Here is a brief summary of those recommendations.

Preseason: Preseason evaluation includes a preparticipation physical evaluation and discussion of concussion history as well as risk factors associated with prolonged concussion recovery. Neurocognitive tests are available for baseline evaluation. While these may assist with diagnosis and return-to-play decisions, there can be considerable variation in an individual’s baseline score as well as the possibility of changes in that baseline over time. Because of this potential for variability, these tests are not required or accepted as the standard of care.

Sideline assessment: Familiarity with the athlete is the best way to detect subtle changes in personality or performance. Looking at symptoms is still the most sensitive way to diagnose a concussion. Loss of consciousness, seizure, tonic posturing, lack of motor coordination, confusion, amnesia, difficulty with balance, or any cognitive difficulty should prompt removal from play for possible concussion. Once a potential injury is identified, how the athlete responds to the elements of orientation, memory, concentration, speech pattern, and balance should be evaluated. If an athlete has a probable or definite concussion, the athlete needs to be removed from play and cannot return to same-day play, and a more detailed evaluation needs to be done.

Office assessment: It is not unusual for symptoms and testing to normalize by the time an office visit occurs. If this is the case, the visit should focus on recommendations for safe return to school and sport. A standard office evaluation should include taking a history with details of the mechanism of injury and preexisting conditions – such as depression and prior concussion – that can affect concussion recovery. The history should focus on detecting symptoms that typically cause impairment from concussion: headache, ocular-vestibular issues leading to problems with balance, and cognitive issues with difficulty concentrating and remembering, as well as fatigue and mood issues such as anxiety, irritability, and depression. The physical exam should include assessment of ocular and vestibular function, gait, and balance in addition to a neurological exam.

Imaging: Head CT or MRI are rarely indicated. Intracranial bleeds are rare in the context of SRC but can occur. If there is concern for a bleed, then CT scan is the imaging test of choice. MRI may have value for evaluation for atypical or prolonged recovery.

Recovery time: The large majority (80%-90%) of concussed older adolescents and adults return to preinjury levels of function within 2 weeks; in younger athletes, clinical recovery may take up to 4 weeks. The best predictor of recovery from SRC is the number and severity of symptoms.

Treatment: For decades, cognitive and physical rest has been the standard of treatment. However, this is no longer the “gold standard” as it has been shown that strict rest (“cocoon therapy”) after SRC slows recovery and leads to an increased chance of prolonged symptoms. Current consensus guidelines support 24-48 hours of symptom-limited rest, both cognitive and physical, followed by a gradual increase in activity, staying below symptom-exacerbation thresholds. Activity, along with good sleep hygiene, appears to be helpful in facilitating recovery from SRC. In athletes with persistent post concussive symptoms that continue beyond the expected recovery time frame, activities of daily living, school, and exercise that do not significantly exacerbate symptoms are recommended.

Return to learning/play: A concussion can cause temporary deficits in attention, cognitive processing, short-term memory, and executive functioning. School personnel should be informed of the injury and assist in employing an individualized return to learn plan, including academic accommodations. Ultimately, return to sports activities should follow a successful return to the classroom. Return to play involves a stepwise increase in physical demands/activity without symptoms before a student is allowed to participate in full contact play.

Concussion-related risks: Continuing to participate in sports before resolution of concussion can worsen and prolong symptoms of SRC. Returning too early after concussion, before full recovery, increases the risk of recurrent SRC. During the initial post-injury period, returning to sports too early increases the risk for a rare but devastating possibility of second impact syndrome that can be a life-threatening repeat head injury. Studies of long-term mental health diagnoses are conflicting and inconsistent. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy has been described in athletes with a long history of concussions and repetitive sub-symptom head impacts. The degree of exposure needed appears to be variable and dependent on the individual.

Disqualification from play: Because each athlete is individually assessed after SRC, there are no evidence-based studies indicating how many concussions are “safe” for an athlete to have in a lifetime. The decision to stop playing sports is both serious and difficult for most athletes and requires shared decision making between clinician, the athlete, and the athlete’s parents. Factors to consider when determining if disqualification from play is warranted include:

- The total number of concussions experienced by a patient.

- Whether a patient has sustained subsequent concussions with progressively less forceful blows to the head.

- If a patient has sustained multiple concussions,whether the time to complete a full recovery after each concussion event increased.

The bottom line: “Cocoon therapy” is no longer recommended. Consensus guidelines endorse 24-48 hours of symptom-limited cognitive and physical rest followed by a gradual increase in activity, including noncontact physical activity that does not provoke symptoms.

Dr. Belogorodsky is a second-year resident and Dr. Fidler is an associate director in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

Harmon KG et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement on concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:213-25.

PHiD-CV with 4CMenB safe, effective for infants

Concomitant administration of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines is not only safe but also offers the potential to improve vaccine uptake and reduce the number of doctors’ visits required for routine vaccination, advised Marco Aurelio P. Safadi, MD, PhD, of Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, Brazil, and associates.

In a post hoc analysis of a phase 3b open-label study, Dr. Safadi and associates sought to evaluate immune response in pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) administered concomitantly with either meningococcal serogroup B (4CMenB) vaccine and CRM-conjugated meningococcal serogroup C vaccine (MenC-CRM) or with MenC-CRM alone using reduced schedules in 213 healthy infants aged 83-104 days. Study participants were enrolled and randomized to one of two groups between April 2011 and December 2014 at four sites in Brazil (Vaccine. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.021).

Similar immune response was seen with vaccine serotypes and vaccine-related pneumococcal serotypes 6A and 19A in children who had received concomitant administration of PHiD-CV, 4CMenB, and MenC-CRM without 4CMenB.

Dr. Safadi and associates pointed out that PHiD-CV was given in accordance with a 3+1 dosing schedule, while 4CMenB used a reduced 2+1 schedule, which was observed to produce an immune response and provide an acceptable safety profile.

The findings yielded valuable information for the 2+1 PHiD-CV vaccination schedule, which was recently introduced in Brazil, the researchers said. The post-booster results further reflect the “immunogenicity following 3-dose priming.”

The post hoc nature of this study design effectively demonstrated that or with MenC-CRM alone, they explained.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals. Three authors are employees of the GSK group of companies, and three others received a grant from the GSK companies, two of whom received compensation from other pharmaceutical companies. The institution of one of the authors received clinical trial fees from the GSK companies, and received personal fees/nonfinancial support/grants/other from the GSK companies and many other pharmaceutical companies.

Concomitant administration of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines is not only safe but also offers the potential to improve vaccine uptake and reduce the number of doctors’ visits required for routine vaccination, advised Marco Aurelio P. Safadi, MD, PhD, of Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, Brazil, and associates.

In a post hoc analysis of a phase 3b open-label study, Dr. Safadi and associates sought to evaluate immune response in pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) administered concomitantly with either meningococcal serogroup B (4CMenB) vaccine and CRM-conjugated meningococcal serogroup C vaccine (MenC-CRM) or with MenC-CRM alone using reduced schedules in 213 healthy infants aged 83-104 days. Study participants were enrolled and randomized to one of two groups between April 2011 and December 2014 at four sites in Brazil (Vaccine. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.021).

Similar immune response was seen with vaccine serotypes and vaccine-related pneumococcal serotypes 6A and 19A in children who had received concomitant administration of PHiD-CV, 4CMenB, and MenC-CRM without 4CMenB.

Dr. Safadi and associates pointed out that PHiD-CV was given in accordance with a 3+1 dosing schedule, while 4CMenB used a reduced 2+1 schedule, which was observed to produce an immune response and provide an acceptable safety profile.

The findings yielded valuable information for the 2+1 PHiD-CV vaccination schedule, which was recently introduced in Brazil, the researchers said. The post-booster results further reflect the “immunogenicity following 3-dose priming.”

The post hoc nature of this study design effectively demonstrated that or with MenC-CRM alone, they explained.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals. Three authors are employees of the GSK group of companies, and three others received a grant from the GSK companies, two of whom received compensation from other pharmaceutical companies. The institution of one of the authors received clinical trial fees from the GSK companies, and received personal fees/nonfinancial support/grants/other from the GSK companies and many other pharmaceutical companies.

Concomitant administration of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines is not only safe but also offers the potential to improve vaccine uptake and reduce the number of doctors’ visits required for routine vaccination, advised Marco Aurelio P. Safadi, MD, PhD, of Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, Brazil, and associates.

In a post hoc analysis of a phase 3b open-label study, Dr. Safadi and associates sought to evaluate immune response in pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) administered concomitantly with either meningococcal serogroup B (4CMenB) vaccine and CRM-conjugated meningococcal serogroup C vaccine (MenC-CRM) or with MenC-CRM alone using reduced schedules in 213 healthy infants aged 83-104 days. Study participants were enrolled and randomized to one of two groups between April 2011 and December 2014 at four sites in Brazil (Vaccine. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.021).

Similar immune response was seen with vaccine serotypes and vaccine-related pneumococcal serotypes 6A and 19A in children who had received concomitant administration of PHiD-CV, 4CMenB, and MenC-CRM without 4CMenB.

Dr. Safadi and associates pointed out that PHiD-CV was given in accordance with a 3+1 dosing schedule, while 4CMenB used a reduced 2+1 schedule, which was observed to produce an immune response and provide an acceptable safety profile.

The findings yielded valuable information for the 2+1 PHiD-CV vaccination schedule, which was recently introduced in Brazil, the researchers said. The post-booster results further reflect the “immunogenicity following 3-dose priming.”

The post hoc nature of this study design effectively demonstrated that or with MenC-CRM alone, they explained.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals. Three authors are employees of the GSK group of companies, and three others received a grant from the GSK companies, two of whom received compensation from other pharmaceutical companies. The institution of one of the authors received clinical trial fees from the GSK companies, and received personal fees/nonfinancial support/grants/other from the GSK companies and many other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM VACCINE

Hadlima approved as fourth adalimumab biosimilar in U.S.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Humira biosimilar Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd), making it the fourth adalimumab biosimilar approved in the United States, the agency announced.

Hadlima is approved for seven of the reference product’s indications, which include rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The product will launch in the United States on June 30, 2023. Other FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars – Amjevita (adalimunab-atto), Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) – similarly will not reach the U.S. market until 2023.

Hadlima is developed by Samsung Bioepis and commercialized by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

*This article was updated on July 24, 2019.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Humira biosimilar Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd), making it the fourth adalimumab biosimilar approved in the United States, the agency announced.

Hadlima is approved for seven of the reference product’s indications, which include rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The product will launch in the United States on June 30, 2023. Other FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars – Amjevita (adalimunab-atto), Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) – similarly will not reach the U.S. market until 2023.

Hadlima is developed by Samsung Bioepis and commercialized by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

*This article was updated on July 24, 2019.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Humira biosimilar Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd), making it the fourth adalimumab biosimilar approved in the United States, the agency announced.

Hadlima is approved for seven of the reference product’s indications, which include rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The product will launch in the United States on June 30, 2023. Other FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars – Amjevita (adalimunab-atto), Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) – similarly will not reach the U.S. market until 2023.

Hadlima is developed by Samsung Bioepis and commercialized by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

*This article was updated on July 24, 2019.

Most preschoolers with signs of ADHD aren’t ready for primary school

Are preschoolers with signs of ADHD ready for school? A new study suggests they’re far from prepared.

A small sample of children with symptoms of moderate to severe ADHD scored markedly lower than comparable children on 8 of 10 measures of readiness for primary education in a study published in Pediatrics.

These children require early identification and intervention,” Hannah T. Perrin, MD, of Stanford University and associates wrote.

There’s sparse research into the prevalence of ADHD symptoms in preschoolers, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that nearly half of children aged 4-5 years with the condition got no behavioral therapy from 2009 to 2010. About 25% received only medical treatment.

Dr. Perrin and colleagues recruited 93 children aged 4-6 years from the community. Their parents, who were compensated, took the Early Childhood Inventory-4 (ECI-4) questionnaire. It revealed that 80% (n = 45) of those diagnosed with ADHD had scores considered signs of moderate or severe ADHD symptom severity based on the parent ratings. Those with lower scores made up the comparison group (n = 48).

The groups were similar, about 60% male and more than 50% white; neither difference between groups was statistically significant. However, those in the comparison group were much more likely to have non-Latino/non-Hispanic ethnicity; 61% in ADHD group vs. 91% in comparison group, P = .001.

The children were tested for school readiness through several measures in two 1- to 1.5-hour sessions.

The researchers reported that 79% of children in the ADHD group were not ready for school (impaired) vs. 13% of the comparison group. (odds ratio, 21, 95% confidence interval, 5.67-77.77, P = .001).

“We found that preschool-aged children with ADHD symptoms demonstrated significantly worse performance on 8 of 10 school readiness measures,” the authors added, “and significantly greater odds of impairment in four of five domains and overall school readiness.”

Dr. Perrin and associates cautioned that the findings rely on a convenience sample, are based on parent – but not teacher – input, do not include Spanish speakers, and do not follow children over the long term.

Going forward, they wrote, “family dynamics and social-emotional functioning should be assessed for each preschool-aged child with ADHD symptoms, and appropriate therapeutic interventions and community supports should be prescribed to enhance school readiness.”

The study authors had no disclosures. Study funders include the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, the Katharine McCormick Faculty Scholar Award, Stanford Children’s Health and Child Health Research Institute Pilot Early Career Award, and the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Perrin HT et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0038.

Are preschoolers with signs of ADHD ready for school? A new study suggests they’re far from prepared.

A small sample of children with symptoms of moderate to severe ADHD scored markedly lower than comparable children on 8 of 10 measures of readiness for primary education in a study published in Pediatrics.

These children require early identification and intervention,” Hannah T. Perrin, MD, of Stanford University and associates wrote.

There’s sparse research into the prevalence of ADHD symptoms in preschoolers, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that nearly half of children aged 4-5 years with the condition got no behavioral therapy from 2009 to 2010. About 25% received only medical treatment.

Dr. Perrin and colleagues recruited 93 children aged 4-6 years from the community. Their parents, who were compensated, took the Early Childhood Inventory-4 (ECI-4) questionnaire. It revealed that 80% (n = 45) of those diagnosed with ADHD had scores considered signs of moderate or severe ADHD symptom severity based on the parent ratings. Those with lower scores made up the comparison group (n = 48).

The groups were similar, about 60% male and more than 50% white; neither difference between groups was statistically significant. However, those in the comparison group were much more likely to have non-Latino/non-Hispanic ethnicity; 61% in ADHD group vs. 91% in comparison group, P = .001.

The children were tested for school readiness through several measures in two 1- to 1.5-hour sessions.

The researchers reported that 79% of children in the ADHD group were not ready for school (impaired) vs. 13% of the comparison group. (odds ratio, 21, 95% confidence interval, 5.67-77.77, P = .001).

“We found that preschool-aged children with ADHD symptoms demonstrated significantly worse performance on 8 of 10 school readiness measures,” the authors added, “and significantly greater odds of impairment in four of five domains and overall school readiness.”

Dr. Perrin and associates cautioned that the findings rely on a convenience sample, are based on parent – but not teacher – input, do not include Spanish speakers, and do not follow children over the long term.

Going forward, they wrote, “family dynamics and social-emotional functioning should be assessed for each preschool-aged child with ADHD symptoms, and appropriate therapeutic interventions and community supports should be prescribed to enhance school readiness.”

The study authors had no disclosures. Study funders include the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, the Katharine McCormick Faculty Scholar Award, Stanford Children’s Health and Child Health Research Institute Pilot Early Career Award, and the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Perrin HT et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0038.

Are preschoolers with signs of ADHD ready for school? A new study suggests they’re far from prepared.

A small sample of children with symptoms of moderate to severe ADHD scored markedly lower than comparable children on 8 of 10 measures of readiness for primary education in a study published in Pediatrics.

These children require early identification and intervention,” Hannah T. Perrin, MD, of Stanford University and associates wrote.

There’s sparse research into the prevalence of ADHD symptoms in preschoolers, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that nearly half of children aged 4-5 years with the condition got no behavioral therapy from 2009 to 2010. About 25% received only medical treatment.

Dr. Perrin and colleagues recruited 93 children aged 4-6 years from the community. Their parents, who were compensated, took the Early Childhood Inventory-4 (ECI-4) questionnaire. It revealed that 80% (n = 45) of those diagnosed with ADHD had scores considered signs of moderate or severe ADHD symptom severity based on the parent ratings. Those with lower scores made up the comparison group (n = 48).

The groups were similar, about 60% male and more than 50% white; neither difference between groups was statistically significant. However, those in the comparison group were much more likely to have non-Latino/non-Hispanic ethnicity; 61% in ADHD group vs. 91% in comparison group, P = .001.

The children were tested for school readiness through several measures in two 1- to 1.5-hour sessions.

The researchers reported that 79% of children in the ADHD group were not ready for school (impaired) vs. 13% of the comparison group. (odds ratio, 21, 95% confidence interval, 5.67-77.77, P = .001).

“We found that preschool-aged children with ADHD symptoms demonstrated significantly worse performance on 8 of 10 school readiness measures,” the authors added, “and significantly greater odds of impairment in four of five domains and overall school readiness.”

Dr. Perrin and associates cautioned that the findings rely on a convenience sample, are based on parent – but not teacher – input, do not include Spanish speakers, and do not follow children over the long term.

Going forward, they wrote, “family dynamics and social-emotional functioning should be assessed for each preschool-aged child with ADHD symptoms, and appropriate therapeutic interventions and community supports should be prescribed to enhance school readiness.”

The study authors had no disclosures. Study funders include the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, the Katharine McCormick Faculty Scholar Award, Stanford Children’s Health and Child Health Research Institute Pilot Early Career Award, and the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Perrin HT et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0038.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Liberalized low–glycemic-index diet effective for seizure reduction

BANGKOK – in a randomized, double-blind, 24-week, noninferiority study.

The low–glycemic-index diet (LGID) was introduced as a kinder, gentler, variant of the classic ketogenic diet for seizure frequency reduction. The ketogenic diet’s efficacy for this purpose is well established, but compliance is a problem and discontinuation rates are high. Yet even though the LGID was designed to be less onerous than the ketogenic diet, many children and parents also find the 7-days-a-week LGID to be excessively burdensome. This was the impetus for pitting the daily LGID against an intermittent version – 5 days on, 2 days off – in a randomized trial, Prateek K. Panda, MD, explained at the International Epilepsy Congress.

The hypothesis of this noninferiority trial was that adherence to the liberalized LGID would be similar to or better than that with the daily LGID regimen, with resultant similar reductions in seizure frequency. And further, that patients on the intermittent LGID would feel better because it would help improve depleted glycogen stores important for daily activity and that the liberalized diet would also be rated more favorably by caregivers, Dr. Panda said at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

The 24-week, single-center trial included 122 children ages 1-15 years with drug-resistant epilepsy. At baseline they averaged 99 seizures per week by parental diary despite being on a median of four antiepileptic drugs. A total of 88% of participants had some form of structural epilepsy; the rest had a probable or confirmed genetic cause for their seizure disorder, according to Dr. Panda of the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

The standard daily LGID was comprised of 10% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 60% fat, with only low–glycemic-index foods permitted. The cohort randomized to the liberalized diet ate that way on weekdays; however, on Saturdays and Sundays their diet was 20% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 50% fat, with both medium- and low–glycemic-index foods allowed.

The primary outcome was the mean reduction in seizures per week by caregiver records at 24 weeks. The reduction from baseline was 54% in the strict LGID group and not significantly different at 49% in the intermittent LGID patients. Overall, 54% of patients in the strict LGID arm experienced a greater than 50% reduction in weekly seizure frequency, as did 50% on the liberalized diet, a nonsignificant difference.

There were five study dropouts in the strict LGID group and three in the liberalized LGID cohort. The two groups showed similar improvements over baseline in measures of social function, behavior, and cognition. Parents of children in the liberalized LGID group rated that diet as significantly less difficult to administer than those randomized to the strict LGID therapy.

Mean hemoglobin A1c improved in the strict LGID patients from 5.7% at baseline to 5.1% at both 12 and 24 weeks. The intermittent LGID group went from 5.6% to 5.0% and then to 5.2%. There was no correlation between HbA1c and reduction in seizure frequency. In contrast, serum beta-hydroxybutyrate levels showed a moderate correlation with seizure frequency, a novel finding which if confirmed might render beta-hydroxybutyrate useful as a biomarker, according to Dr. Panda.

Adverse events – mostly dyslipidemia and GI complaints such as vomiting or constipation – occurred in 25% of the strict LGID group and 13% with the intermittent LGID. All adverse events were mild.

Dr. Panda reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, sponsored by the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences.

SOURCE: Panda PK et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P056.

BANGKOK – in a randomized, double-blind, 24-week, noninferiority study.

The low–glycemic-index diet (LGID) was introduced as a kinder, gentler, variant of the classic ketogenic diet for seizure frequency reduction. The ketogenic diet’s efficacy for this purpose is well established, but compliance is a problem and discontinuation rates are high. Yet even though the LGID was designed to be less onerous than the ketogenic diet, many children and parents also find the 7-days-a-week LGID to be excessively burdensome. This was the impetus for pitting the daily LGID against an intermittent version – 5 days on, 2 days off – in a randomized trial, Prateek K. Panda, MD, explained at the International Epilepsy Congress.

The hypothesis of this noninferiority trial was that adherence to the liberalized LGID would be similar to or better than that with the daily LGID regimen, with resultant similar reductions in seizure frequency. And further, that patients on the intermittent LGID would feel better because it would help improve depleted glycogen stores important for daily activity and that the liberalized diet would also be rated more favorably by caregivers, Dr. Panda said at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

The 24-week, single-center trial included 122 children ages 1-15 years with drug-resistant epilepsy. At baseline they averaged 99 seizures per week by parental diary despite being on a median of four antiepileptic drugs. A total of 88% of participants had some form of structural epilepsy; the rest had a probable or confirmed genetic cause for their seizure disorder, according to Dr. Panda of the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

The standard daily LGID was comprised of 10% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 60% fat, with only low–glycemic-index foods permitted. The cohort randomized to the liberalized diet ate that way on weekdays; however, on Saturdays and Sundays their diet was 20% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 50% fat, with both medium- and low–glycemic-index foods allowed.

The primary outcome was the mean reduction in seizures per week by caregiver records at 24 weeks. The reduction from baseline was 54% in the strict LGID group and not significantly different at 49% in the intermittent LGID patients. Overall, 54% of patients in the strict LGID arm experienced a greater than 50% reduction in weekly seizure frequency, as did 50% on the liberalized diet, a nonsignificant difference.

There were five study dropouts in the strict LGID group and three in the liberalized LGID cohort. The two groups showed similar improvements over baseline in measures of social function, behavior, and cognition. Parents of children in the liberalized LGID group rated that diet as significantly less difficult to administer than those randomized to the strict LGID therapy.

Mean hemoglobin A1c improved in the strict LGID patients from 5.7% at baseline to 5.1% at both 12 and 24 weeks. The intermittent LGID group went from 5.6% to 5.0% and then to 5.2%. There was no correlation between HbA1c and reduction in seizure frequency. In contrast, serum beta-hydroxybutyrate levels showed a moderate correlation with seizure frequency, a novel finding which if confirmed might render beta-hydroxybutyrate useful as a biomarker, according to Dr. Panda.

Adverse events – mostly dyslipidemia and GI complaints such as vomiting or constipation – occurred in 25% of the strict LGID group and 13% with the intermittent LGID. All adverse events were mild.

Dr. Panda reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, sponsored by the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences.

SOURCE: Panda PK et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P056.

BANGKOK – in a randomized, double-blind, 24-week, noninferiority study.

The low–glycemic-index diet (LGID) was introduced as a kinder, gentler, variant of the classic ketogenic diet for seizure frequency reduction. The ketogenic diet’s efficacy for this purpose is well established, but compliance is a problem and discontinuation rates are high. Yet even though the LGID was designed to be less onerous than the ketogenic diet, many children and parents also find the 7-days-a-week LGID to be excessively burdensome. This was the impetus for pitting the daily LGID against an intermittent version – 5 days on, 2 days off – in a randomized trial, Prateek K. Panda, MD, explained at the International Epilepsy Congress.

The hypothesis of this noninferiority trial was that adherence to the liberalized LGID would be similar to or better than that with the daily LGID regimen, with resultant similar reductions in seizure frequency. And further, that patients on the intermittent LGID would feel better because it would help improve depleted glycogen stores important for daily activity and that the liberalized diet would also be rated more favorably by caregivers, Dr. Panda said at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

The 24-week, single-center trial included 122 children ages 1-15 years with drug-resistant epilepsy. At baseline they averaged 99 seizures per week by parental diary despite being on a median of four antiepileptic drugs. A total of 88% of participants had some form of structural epilepsy; the rest had a probable or confirmed genetic cause for their seizure disorder, according to Dr. Panda of the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

The standard daily LGID was comprised of 10% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 60% fat, with only low–glycemic-index foods permitted. The cohort randomized to the liberalized diet ate that way on weekdays; however, on Saturdays and Sundays their diet was 20% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 50% fat, with both medium- and low–glycemic-index foods allowed.

The primary outcome was the mean reduction in seizures per week by caregiver records at 24 weeks. The reduction from baseline was 54% in the strict LGID group and not significantly different at 49% in the intermittent LGID patients. Overall, 54% of patients in the strict LGID arm experienced a greater than 50% reduction in weekly seizure frequency, as did 50% on the liberalized diet, a nonsignificant difference.

There were five study dropouts in the strict LGID group and three in the liberalized LGID cohort. The two groups showed similar improvements over baseline in measures of social function, behavior, and cognition. Parents of children in the liberalized LGID group rated that diet as significantly less difficult to administer than those randomized to the strict LGID therapy.

Mean hemoglobin A1c improved in the strict LGID patients from 5.7% at baseline to 5.1% at both 12 and 24 weeks. The intermittent LGID group went from 5.6% to 5.0% and then to 5.2%. There was no correlation between HbA1c and reduction in seizure frequency. In contrast, serum beta-hydroxybutyrate levels showed a moderate correlation with seizure frequency, a novel finding which if confirmed might render beta-hydroxybutyrate useful as a biomarker, according to Dr. Panda.

Adverse events – mostly dyslipidemia and GI complaints such as vomiting or constipation – occurred in 25% of the strict LGID group and 13% with the intermittent LGID. All adverse events were mild.

Dr. Panda reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, sponsored by the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences.

SOURCE: Panda PK et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P056.

REPORTING FROM IEC 2019

Painless Purple Streaks on the Arms and Chest

The Diagnosis: Factitial Purpura

Factitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is unclear, and the patient's history of the injury is hollow.2 Most often, there is sudden onset of the lesions without any warning or symptoms. When giving the history, the patient may appear unemotional, does not report pain, and denies self-infliction.1

In factitial purpura, the purple patches are clearly demarcated from uninvolved skin and have an unusual angular or geometric shape. The pattern typically takes the shape of the object used to create the purpura and lacks the features of recognizable dermatoses.2 In our patient and those with similar linear purpuric streaks, we use the term penny purpura to indicate that the lesions resulted from rubbing with a penny or other blunt object, similar to coining. The lesions occur in areas that are easily accessible and visible such as the arms, chest, or chin. It is suggested that the child unconsciously wants the lesions to be seen. Histologic findings in factitial purpura include disruption of collagen fiber bundles and extravasated red blood cells in the dermis.3 Unfortunately, evolving lesions may give nonspecific histologic findings; when the clinical lesions are typical, skin biopsy usually is unnecessary and may be misleading. Laboratory test results such as complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time usually are within reference range, as in our patient.

When evaluating these patients, confrontation is not recommended. More than two-thirds of affected patients have a history of trauma such as sexual/physical abuse or neglect, and the lesions typically arise during times of stress.1,3 Thus, treatment includes nonaccusatory measures and referral for psychologic evaluation. The purpura will rapidly heal when covered with an occlusive dressing.2

The differential diagnosis for penny purpura includes lesions that evolve from cupping and coining. Cupping is a type of complementary and alternative medicine that acts by correcting imbalances in the internal biofield and restoring the flow of qi, which determines the state of one's health and life span.4 Cupping is performed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical withdrawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the cup. When the flame exhausts the supply of oxygen, the skin is sucked into the mouth of the glass, and the skin is bruised painlessly.4

The differential also includes child maltreatment syndrome and other disorders that would potentiate bruising. Intravascular etiologies include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, coagulation disorders, and other causes of thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction.3 Extravascular etiologies include hereditary collagen vascular disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), malnutrition, and other disorders associated with a decrease in collagen and other tissues that support cutaneous vessels. Vascular etiologies include infectious (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia) and noninfectious vasculitis (eg, Henoch-Schönlein purpura), leaky capillary syndrome, drug reactions, and other disorders associated with a loss of vascular integrity.3

It is important to be able to differentiate self-inflicted lesions in a person who repeatedly acts as if he/she has a physical disorder from those that are created during the practices of cupping or any other cultural healing practice. Vascular disorders, malnutrition, and child abuse also should be excluded.3

For our patient with factitial purpura, we gently encouraged the family to work with the child's pediatrician and a pediatric psychologist to deal with stress related to the recurrent rash and asked them to think of the rash as a result of an external cause; however, we were careful not to blame anyone for the rash.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372; quiz 373.

- Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:247-257.

- Ring HC, Miller IM, Benfeldt E, et al. Artefactual skin lesions in children and adolescents: review of the literature and two cases of factitious purpura. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E27-E32.

- Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:127-134.

The Diagnosis: Factitial Purpura

Factitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is unclear, and the patient's history of the injury is hollow.2 Most often, there is sudden onset of the lesions without any warning or symptoms. When giving the history, the patient may appear unemotional, does not report pain, and denies self-infliction.1

In factitial purpura, the purple patches are clearly demarcated from uninvolved skin and have an unusual angular or geometric shape. The pattern typically takes the shape of the object used to create the purpura and lacks the features of recognizable dermatoses.2 In our patient and those with similar linear purpuric streaks, we use the term penny purpura to indicate that the lesions resulted from rubbing with a penny or other blunt object, similar to coining. The lesions occur in areas that are easily accessible and visible such as the arms, chest, or chin. It is suggested that the child unconsciously wants the lesions to be seen. Histologic findings in factitial purpura include disruption of collagen fiber bundles and extravasated red blood cells in the dermis.3 Unfortunately, evolving lesions may give nonspecific histologic findings; when the clinical lesions are typical, skin biopsy usually is unnecessary and may be misleading. Laboratory test results such as complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time usually are within reference range, as in our patient.

When evaluating these patients, confrontation is not recommended. More than two-thirds of affected patients have a history of trauma such as sexual/physical abuse or neglect, and the lesions typically arise during times of stress.1,3 Thus, treatment includes nonaccusatory measures and referral for psychologic evaluation. The purpura will rapidly heal when covered with an occlusive dressing.2

The differential diagnosis for penny purpura includes lesions that evolve from cupping and coining. Cupping is a type of complementary and alternative medicine that acts by correcting imbalances in the internal biofield and restoring the flow of qi, which determines the state of one's health and life span.4 Cupping is performed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical withdrawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the cup. When the flame exhausts the supply of oxygen, the skin is sucked into the mouth of the glass, and the skin is bruised painlessly.4

The differential also includes child maltreatment syndrome and other disorders that would potentiate bruising. Intravascular etiologies include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, coagulation disorders, and other causes of thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction.3 Extravascular etiologies include hereditary collagen vascular disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), malnutrition, and other disorders associated with a decrease in collagen and other tissues that support cutaneous vessels. Vascular etiologies include infectious (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia) and noninfectious vasculitis (eg, Henoch-Schönlein purpura), leaky capillary syndrome, drug reactions, and other disorders associated with a loss of vascular integrity.3

It is important to be able to differentiate self-inflicted lesions in a person who repeatedly acts as if he/she has a physical disorder from those that are created during the practices of cupping or any other cultural healing practice. Vascular disorders, malnutrition, and child abuse also should be excluded.3

For our patient with factitial purpura, we gently encouraged the family to work with the child's pediatrician and a pediatric psychologist to deal with stress related to the recurrent rash and asked them to think of the rash as a result of an external cause; however, we were careful not to blame anyone for the rash.

The Diagnosis: Factitial Purpura

Factitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is unclear, and the patient's history of the injury is hollow.2 Most often, there is sudden onset of the lesions without any warning or symptoms. When giving the history, the patient may appear unemotional, does not report pain, and denies self-infliction.1

In factitial purpura, the purple patches are clearly demarcated from uninvolved skin and have an unusual angular or geometric shape. The pattern typically takes the shape of the object used to create the purpura and lacks the features of recognizable dermatoses.2 In our patient and those with similar linear purpuric streaks, we use the term penny purpura to indicate that the lesions resulted from rubbing with a penny or other blunt object, similar to coining. The lesions occur in areas that are easily accessible and visible such as the arms, chest, or chin. It is suggested that the child unconsciously wants the lesions to be seen. Histologic findings in factitial purpura include disruption of collagen fiber bundles and extravasated red blood cells in the dermis.3 Unfortunately, evolving lesions may give nonspecific histologic findings; when the clinical lesions are typical, skin biopsy usually is unnecessary and may be misleading. Laboratory test results such as complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time usually are within reference range, as in our patient.

When evaluating these patients, confrontation is not recommended. More than two-thirds of affected patients have a history of trauma such as sexual/physical abuse or neglect, and the lesions typically arise during times of stress.1,3 Thus, treatment includes nonaccusatory measures and referral for psychologic evaluation. The purpura will rapidly heal when covered with an occlusive dressing.2

The differential diagnosis for penny purpura includes lesions that evolve from cupping and coining. Cupping is a type of complementary and alternative medicine that acts by correcting imbalances in the internal biofield and restoring the flow of qi, which determines the state of one's health and life span.4 Cupping is performed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical withdrawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the cup. When the flame exhausts the supply of oxygen, the skin is sucked into the mouth of the glass, and the skin is bruised painlessly.4

The differential also includes child maltreatment syndrome and other disorders that would potentiate bruising. Intravascular etiologies include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, coagulation disorders, and other causes of thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction.3 Extravascular etiologies include hereditary collagen vascular disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), malnutrition, and other disorders associated with a decrease in collagen and other tissues that support cutaneous vessels. Vascular etiologies include infectious (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia) and noninfectious vasculitis (eg, Henoch-Schönlein purpura), leaky capillary syndrome, drug reactions, and other disorders associated with a loss of vascular integrity.3

It is important to be able to differentiate self-inflicted lesions in a person who repeatedly acts as if he/she has a physical disorder from those that are created during the practices of cupping or any other cultural healing practice. Vascular disorders, malnutrition, and child abuse also should be excluded.3

For our patient with factitial purpura, we gently encouraged the family to work with the child's pediatrician and a pediatric psychologist to deal with stress related to the recurrent rash and asked them to think of the rash as a result of an external cause; however, we were careful not to blame anyone for the rash.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372; quiz 373.

- Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:247-257.

- Ring HC, Miller IM, Benfeldt E, et al. Artefactual skin lesions in children and adolescents: review of the literature and two cases of factitious purpura. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E27-E32.

- Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:127-134.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372; quiz 373.

- Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:247-257.

- Ring HC, Miller IM, Benfeldt E, et al. Artefactual skin lesions in children and adolescents: review of the literature and two cases of factitious purpura. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E27-E32.

- Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:127-134.

A 10-year-old boy presented with painless purple streaks on the arms and chest of 2 months' duration. The rash recurred several times per month and cleared without treatment in 3 to 5 days. There was no history of trauma or medication exposure, and he was growing and developing normally.

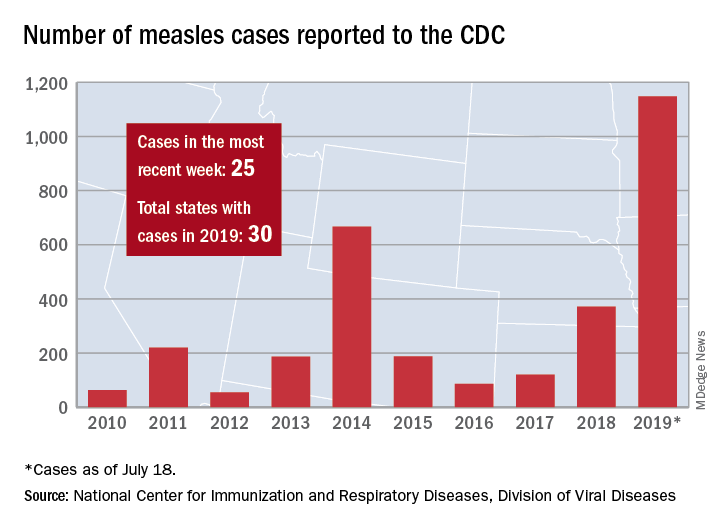

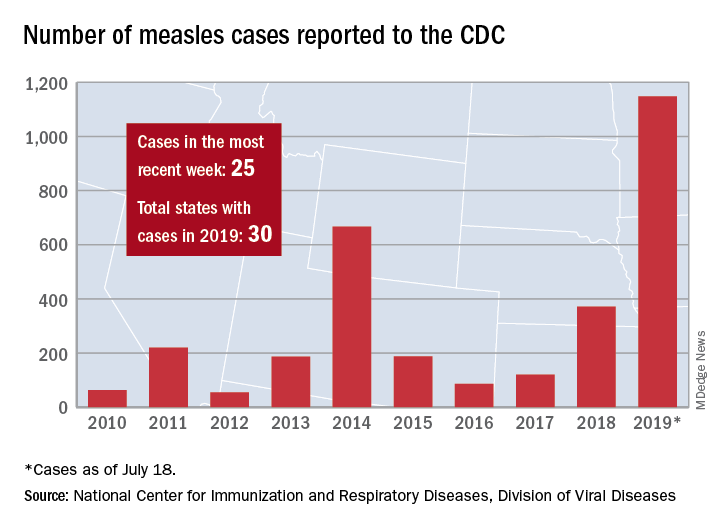

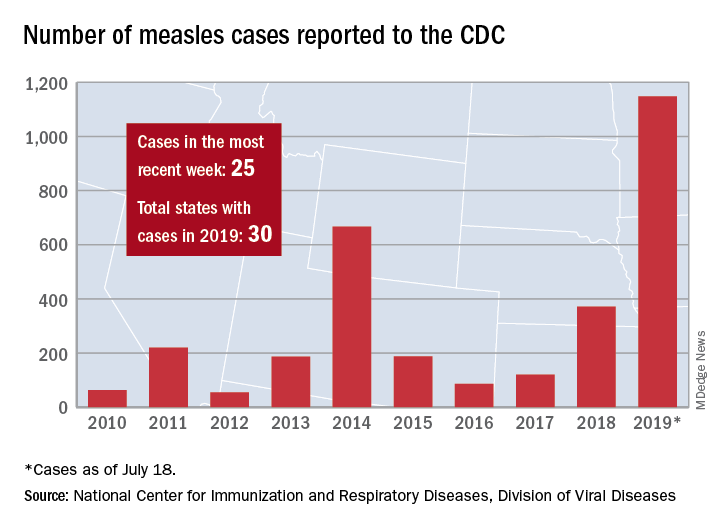

New measles outbreaks reported in Los Angeles and El Paso

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total number of confirmed cases of measles in the United States is now up to 1,148 for the year, which is 25 more than the previous week, the CDC said on July 22. The highest 1-week total for the year was the 90 cases reported during the week of April 11.

The number of outbreaks is back up to five as California returned to the list after a 1-week absence and El Paso, Tex., made its first appearance of the year. The current outbreak in California – the state’s fifth – is occurring in Los Angeles, which is now up to 16 total cases in 2019. El Paso just reported its fourth case on July 17, and the city’s health department noted that “it had been more than 25 years since El Paso saw its last case of measles before these four recent cases.” Outbreaks also are ongoing in Rockland County, N.Y.; New York City; and three counties in Washington State.

States that joined the ranks of the measles-infected during this most recent reporting week were Alaska and Ohio, which brings the total number to 30 for the year, the CDC said.

The Alaska Department of Health and Social Services said that it “has confirmed a single case of measles in an unvaccinated teenager from the Kenai Peninsula who recently traveled out of state to Arizona via Seattle.” The Ohio case is a “young adult from Stark County [who] recently traveled to a state with confirmed measles cases,” according to the state’s health department.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total number of confirmed cases of measles in the United States is now up to 1,148 for the year, which is 25 more than the previous week, the CDC said on July 22. The highest 1-week total for the year was the 90 cases reported during the week of April 11.

The number of outbreaks is back up to five as California returned to the list after a 1-week absence and El Paso, Tex., made its first appearance of the year. The current outbreak in California – the state’s fifth – is occurring in Los Angeles, which is now up to 16 total cases in 2019. El Paso just reported its fourth case on July 17, and the city’s health department noted that “it had been more than 25 years since El Paso saw its last case of measles before these four recent cases.” Outbreaks also are ongoing in Rockland County, N.Y.; New York City; and three counties in Washington State.

States that joined the ranks of the measles-infected during this most recent reporting week were Alaska and Ohio, which brings the total number to 30 for the year, the CDC said.

The Alaska Department of Health and Social Services said that it “has confirmed a single case of measles in an unvaccinated teenager from the Kenai Peninsula who recently traveled out of state to Arizona via Seattle.” The Ohio case is a “young adult from Stark County [who] recently traveled to a state with confirmed measles cases,” according to the state’s health department.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.