User login

Cosmetic Treatments for Skin of Color: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Vitiligo linked to moles, tanning ability, blistering sunburn

Upper extremity moles were associated with a 37% increase in the likelihood of vitiligo among white women, according to an analysis of the prospective Nurses’ Health Study.

“Women with a higher tanning ability and women who had a history of blistering sunburns in childhood were also found to have a higher risk of developing vitiligo,” Rachel Dunlap, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University in Providence, R.I., and her associates wrote in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Vitiligo is the most common cutaneous depigmentation disorder, but associated risk factors are poorly understood, the investigators noted. They examined ties between skin pigmentation, reactions to sun exposure, and new onset vitiligo in the Nurses’ Health Study, a population-based prospective cohort study. Study participants were asked to report the number of moles on their left arms measuring at least 3 mm in diameter, their reactions to sunburn and ability to tan during childhood, and whether they had vitiligo diagnosed by a physician. A total of 51,337 women answered the question about moles, and 68,590 women answered the question about vitiligo, the investigators said (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.02.004).

A total of 271 cases of vitiligo developed over 835,594 person-years. Women who reported at least one left arm mole larger than 3 mm were significantly more likely to report incident vitiligo, compared with women without moles (hazard ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.83), even after controlling for age, hair color, history of exposure to direct sunlight, skin tanning ability, and severity of reaction to sunburn. Developing an “average” tan or a “deep” tan after prolonged sun exposure also were significantly associated with vitiligo with hazard ratios of 2.28 (95% CI, 1.12-4.65) and 2.59 (95% CI, 1.21-5.54), respectively, “when compared to those who had minimal skin reactions or less severe burns when exposed to the sun,” the authors wrote.

A history of at least one blistering sunburn after 2 hours of sun exposure also predicted vitiligo (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.15-4.10), while hair color did not.

“The benefits of good sun protection can be expanded to include potential vitiligo prevention, which may be particularly applicable to adult patients with vitiligo who are concerned about their children developing the condition,” the investigators commented. “Future studies will examine the incidence of other influencing factors, such as melanoma and melanoma associated leukoderma in this population.”

External funding sources included the National Institutes of Health and Dermatology Foundation. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Upper extremity moles were associated with a 37% increase in the likelihood of vitiligo among white women, according to an analysis of the prospective Nurses’ Health Study.

“Women with a higher tanning ability and women who had a history of blistering sunburns in childhood were also found to have a higher risk of developing vitiligo,” Rachel Dunlap, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University in Providence, R.I., and her associates wrote in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Vitiligo is the most common cutaneous depigmentation disorder, but associated risk factors are poorly understood, the investigators noted. They examined ties between skin pigmentation, reactions to sun exposure, and new onset vitiligo in the Nurses’ Health Study, a population-based prospective cohort study. Study participants were asked to report the number of moles on their left arms measuring at least 3 mm in diameter, their reactions to sunburn and ability to tan during childhood, and whether they had vitiligo diagnosed by a physician. A total of 51,337 women answered the question about moles, and 68,590 women answered the question about vitiligo, the investigators said (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.02.004).

A total of 271 cases of vitiligo developed over 835,594 person-years. Women who reported at least one left arm mole larger than 3 mm were significantly more likely to report incident vitiligo, compared with women without moles (hazard ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.83), even after controlling for age, hair color, history of exposure to direct sunlight, skin tanning ability, and severity of reaction to sunburn. Developing an “average” tan or a “deep” tan after prolonged sun exposure also were significantly associated with vitiligo with hazard ratios of 2.28 (95% CI, 1.12-4.65) and 2.59 (95% CI, 1.21-5.54), respectively, “when compared to those who had minimal skin reactions or less severe burns when exposed to the sun,” the authors wrote.

A history of at least one blistering sunburn after 2 hours of sun exposure also predicted vitiligo (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.15-4.10), while hair color did not.

“The benefits of good sun protection can be expanded to include potential vitiligo prevention, which may be particularly applicable to adult patients with vitiligo who are concerned about their children developing the condition,” the investigators commented. “Future studies will examine the incidence of other influencing factors, such as melanoma and melanoma associated leukoderma in this population.”

External funding sources included the National Institutes of Health and Dermatology Foundation. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Upper extremity moles were associated with a 37% increase in the likelihood of vitiligo among white women, according to an analysis of the prospective Nurses’ Health Study.

“Women with a higher tanning ability and women who had a history of blistering sunburns in childhood were also found to have a higher risk of developing vitiligo,” Rachel Dunlap, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University in Providence, R.I., and her associates wrote in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Vitiligo is the most common cutaneous depigmentation disorder, but associated risk factors are poorly understood, the investigators noted. They examined ties between skin pigmentation, reactions to sun exposure, and new onset vitiligo in the Nurses’ Health Study, a population-based prospective cohort study. Study participants were asked to report the number of moles on their left arms measuring at least 3 mm in diameter, their reactions to sunburn and ability to tan during childhood, and whether they had vitiligo diagnosed by a physician. A total of 51,337 women answered the question about moles, and 68,590 women answered the question about vitiligo, the investigators said (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.02.004).

A total of 271 cases of vitiligo developed over 835,594 person-years. Women who reported at least one left arm mole larger than 3 mm were significantly more likely to report incident vitiligo, compared with women without moles (hazard ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.83), even after controlling for age, hair color, history of exposure to direct sunlight, skin tanning ability, and severity of reaction to sunburn. Developing an “average” tan or a “deep” tan after prolonged sun exposure also were significantly associated with vitiligo with hazard ratios of 2.28 (95% CI, 1.12-4.65) and 2.59 (95% CI, 1.21-5.54), respectively, “when compared to those who had minimal skin reactions or less severe burns when exposed to the sun,” the authors wrote.

A history of at least one blistering sunburn after 2 hours of sun exposure also predicted vitiligo (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.15-4.10), while hair color did not.

“The benefits of good sun protection can be expanded to include potential vitiligo prevention, which may be particularly applicable to adult patients with vitiligo who are concerned about their children developing the condition,” the investigators commented. “Future studies will examine the incidence of other influencing factors, such as melanoma and melanoma associated leukoderma in this population.”

External funding sources included the National Institutes of Health and Dermatology Foundation. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Upper extremity moles, tanning ability, and a history of blistering sunburn were significant risk factors for vitiligo among white women.

Major finding: In the multivariate analysis, hazard ratios were 1.37 (95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.83), 2.28 (95% CI, 1.12-4.65), 2.59 (95% CI, 1.21-5.54), and 2.17 (95% CI, 1.15-4.10), respectively.

Data source: An analysis of 51,337 white women from the Nurses’ Health Study.

Disclosures: Funding sources included the National Institutes of Health and Dermatology Foundation. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Widespread Poikilodermatous Dermatomyositis Associated With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

To the Editor:

Dermatomyositis represents a rare idiopathic inflammatory process presenting with cutaneous lesions and muscular weakness. It often represents a paraneoplastic syndrome. We report the case of a 62-year-old man with a history of total-body poikiloderma and a recent diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Despite lacking typical features of the disease, a diagnosis of dermatomyositis was made. Our patient may represent a distinct poikilodermatous variant of dermatomyositis, sharing the generalized distribution of the erythrodermic subtype.

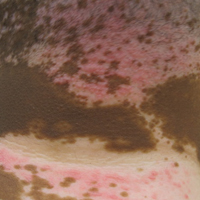

A 62-year-old man presented with pruritic poikiloderma involving the neck, arms, legs, abdomen, chest, and back of 2 years’ duration (Figure). He also experienced dysphagia and weakness of the legs. The rash was previously treated by other dermatologists with a combination of high-potency topical steroids and topical tacrolimus 0.1% without success. His history was notable for CLL, which had been diagnosed by a dermatologist 6 months prior to the current presentation. Prior to his visit to the dermatologist, the patient had received 6 chemotherapeutic sessions with a combination of rituximab and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of CLL. The rash did not improve with chemotherapy.

Repeat biopsies of affected regions only demonstrated features of mild interface dermatitis. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed scattered colloid body fluorescence for IgM. Because of bilateral weakness of the legs, a muscle biopsy was taken, which demonstrated severe atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, with neurogenic abnormalities detected in areas of lesser atrophy via abnormal muscle fiber–type grouping. Metabolic panel showed elevated muscle enzymes in the blood: creatine kinase, 243 U/L (reference range, 10–225 U/L); serum aldolase, 16 U/L (reference range, ≤8.1 U/L); lactate dehydrogenase, 314 U/L (reference range, 60–200 U/L). An autoimmune panel was negative for Jo-1, Scl-70, U1 ribonucleoprotein, DNA, desmoglein 1 and 3, and antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate was measured at 16 mm/h (reference range, 0–10 mm/h). Given these findings, the lesions were confirmed as a widespread poikilodermatous variant of dermatomyositis.

The patient was placed on a daily 50-mg dose of prednisone, which produced rapid improvement in scaling and erythema. Creatine kinase and serum aldolase levels normalized and motor strength increased. After 1 week the prednisone dosage was reduced to a daily 30-mg dose, and then 20 mg a week later. The skin lesions completely resolved within 4 to 5 months and the patient is currently on a prednisone dose of 5 mg, alternating with 2.5 mg of prednisone and rituximab infusion every 2 months.

Dermatomyositis is a rare entity with an incidence of approximately 0.5 to 1 per 100,000 individuals.1 It presents with a characteristic rash composed of Gottron papules; pathognomonic flat violaceous papules on the dorsal interphalangeal joints, elbows, or knees; and a heliotrope rash, a violaceous erythema involving the eyelids. Poikiloderma frequently is reported to present in a shawl-like distribution, encompassing the shoulders, arms, and upper back.1,2 Dermatomyositis of the poikilodermatous type can present in nonphotoexposed areas and photoexposed areas. The unusual feature is the total-body involvement, which is analogous to erythroderma.3

Our case may represent a distinct poikilodermatous manifestation sharing the distribution of the erythrodermic subtype. We believe that the skin lesions may have represented a paraneoplastic event presenting prior to diagnosis with CLL. Dermatomyositis has a strong association with cancer, with patients 3 times more likely to develop internal malignancy.4 Association is strongest for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as ovarian, lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancer. When associated with malignancy, symptoms of dermatomyositis or myositis typically precede the discovery of malignancy by an average of 1.9 years.5 Dermatomyositis has been previously reported to present as a paraneoplastic manifestation of CLL.6 One case has been reported of a patient with CLL who developed leukemia cutis presenting with poikiloderma in the characteristic dermatomyositis shawl-like distribution.7 The lack of dermal infiltration with leukemic cells in our patient, however, makes a paraneoplastic etiology much more likely.

Our patient’s rash did not initially improve with treatment of CLL, but dermatomyositis associated with hematological malignancy may precede, occur simultaneously, or follow the diagnosis of malignancy.8 Additionally, symptoms of dermatomyositis do not always parallel the course of hematological malignancy outcome. However, rituximab has been used as a treatment of dermatomyositis and may have contributed some synergistic effect in combination with prednisone in our patient.9

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL, Schwartz RA. Dermatomyositis: cutaneous manifestations of its variants. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:625-630.

- Kovacs SO, Kovacs SC. Dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:899-920; quiz 921-992.

- Liu ZH, Wang XD. Acute-onset adult dermatomyositis presenting with erythroderma and diplopia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:751-752.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, et al. Computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:255-286.

- Ishida T, Aikawa K, Tamura T, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated with nephrotic syndrome and dermatomyositis. Intern Med. 1995;34:15-17.

- Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Huang CH, et al. T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia mimicking dermatomyositis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:144-146.

- Marie I, Guillevin L, Menard JF, et al. Hematological malignancy associated with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:615-620.

- Levine TD. Rituximab in the treatment of dermatomyositis: an open-label pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:601-607.

To the Editor:

Dermatomyositis represents a rare idiopathic inflammatory process presenting with cutaneous lesions and muscular weakness. It often represents a paraneoplastic syndrome. We report the case of a 62-year-old man with a history of total-body poikiloderma and a recent diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Despite lacking typical features of the disease, a diagnosis of dermatomyositis was made. Our patient may represent a distinct poikilodermatous variant of dermatomyositis, sharing the generalized distribution of the erythrodermic subtype.

A 62-year-old man presented with pruritic poikiloderma involving the neck, arms, legs, abdomen, chest, and back of 2 years’ duration (Figure). He also experienced dysphagia and weakness of the legs. The rash was previously treated by other dermatologists with a combination of high-potency topical steroids and topical tacrolimus 0.1% without success. His history was notable for CLL, which had been diagnosed by a dermatologist 6 months prior to the current presentation. Prior to his visit to the dermatologist, the patient had received 6 chemotherapeutic sessions with a combination of rituximab and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of CLL. The rash did not improve with chemotherapy.

Repeat biopsies of affected regions only demonstrated features of mild interface dermatitis. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed scattered colloid body fluorescence for IgM. Because of bilateral weakness of the legs, a muscle biopsy was taken, which demonstrated severe atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, with neurogenic abnormalities detected in areas of lesser atrophy via abnormal muscle fiber–type grouping. Metabolic panel showed elevated muscle enzymes in the blood: creatine kinase, 243 U/L (reference range, 10–225 U/L); serum aldolase, 16 U/L (reference range, ≤8.1 U/L); lactate dehydrogenase, 314 U/L (reference range, 60–200 U/L). An autoimmune panel was negative for Jo-1, Scl-70, U1 ribonucleoprotein, DNA, desmoglein 1 and 3, and antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate was measured at 16 mm/h (reference range, 0–10 mm/h). Given these findings, the lesions were confirmed as a widespread poikilodermatous variant of dermatomyositis.

The patient was placed on a daily 50-mg dose of prednisone, which produced rapid improvement in scaling and erythema. Creatine kinase and serum aldolase levels normalized and motor strength increased. After 1 week the prednisone dosage was reduced to a daily 30-mg dose, and then 20 mg a week later. The skin lesions completely resolved within 4 to 5 months and the patient is currently on a prednisone dose of 5 mg, alternating with 2.5 mg of prednisone and rituximab infusion every 2 months.

Dermatomyositis is a rare entity with an incidence of approximately 0.5 to 1 per 100,000 individuals.1 It presents with a characteristic rash composed of Gottron papules; pathognomonic flat violaceous papules on the dorsal interphalangeal joints, elbows, or knees; and a heliotrope rash, a violaceous erythema involving the eyelids. Poikiloderma frequently is reported to present in a shawl-like distribution, encompassing the shoulders, arms, and upper back.1,2 Dermatomyositis of the poikilodermatous type can present in nonphotoexposed areas and photoexposed areas. The unusual feature is the total-body involvement, which is analogous to erythroderma.3

Our case may represent a distinct poikilodermatous manifestation sharing the distribution of the erythrodermic subtype. We believe that the skin lesions may have represented a paraneoplastic event presenting prior to diagnosis with CLL. Dermatomyositis has a strong association with cancer, with patients 3 times more likely to develop internal malignancy.4 Association is strongest for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as ovarian, lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancer. When associated with malignancy, symptoms of dermatomyositis or myositis typically precede the discovery of malignancy by an average of 1.9 years.5 Dermatomyositis has been previously reported to present as a paraneoplastic manifestation of CLL.6 One case has been reported of a patient with CLL who developed leukemia cutis presenting with poikiloderma in the characteristic dermatomyositis shawl-like distribution.7 The lack of dermal infiltration with leukemic cells in our patient, however, makes a paraneoplastic etiology much more likely.

Our patient’s rash did not initially improve with treatment of CLL, but dermatomyositis associated with hematological malignancy may precede, occur simultaneously, or follow the diagnosis of malignancy.8 Additionally, symptoms of dermatomyositis do not always parallel the course of hematological malignancy outcome. However, rituximab has been used as a treatment of dermatomyositis and may have contributed some synergistic effect in combination with prednisone in our patient.9

To the Editor:

Dermatomyositis represents a rare idiopathic inflammatory process presenting with cutaneous lesions and muscular weakness. It often represents a paraneoplastic syndrome. We report the case of a 62-year-old man with a history of total-body poikiloderma and a recent diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Despite lacking typical features of the disease, a diagnosis of dermatomyositis was made. Our patient may represent a distinct poikilodermatous variant of dermatomyositis, sharing the generalized distribution of the erythrodermic subtype.

A 62-year-old man presented with pruritic poikiloderma involving the neck, arms, legs, abdomen, chest, and back of 2 years’ duration (Figure). He also experienced dysphagia and weakness of the legs. The rash was previously treated by other dermatologists with a combination of high-potency topical steroids and topical tacrolimus 0.1% without success. His history was notable for CLL, which had been diagnosed by a dermatologist 6 months prior to the current presentation. Prior to his visit to the dermatologist, the patient had received 6 chemotherapeutic sessions with a combination of rituximab and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of CLL. The rash did not improve with chemotherapy.

Repeat biopsies of affected regions only demonstrated features of mild interface dermatitis. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed scattered colloid body fluorescence for IgM. Because of bilateral weakness of the legs, a muscle biopsy was taken, which demonstrated severe atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, with neurogenic abnormalities detected in areas of lesser atrophy via abnormal muscle fiber–type grouping. Metabolic panel showed elevated muscle enzymes in the blood: creatine kinase, 243 U/L (reference range, 10–225 U/L); serum aldolase, 16 U/L (reference range, ≤8.1 U/L); lactate dehydrogenase, 314 U/L (reference range, 60–200 U/L). An autoimmune panel was negative for Jo-1, Scl-70, U1 ribonucleoprotein, DNA, desmoglein 1 and 3, and antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate was measured at 16 mm/h (reference range, 0–10 mm/h). Given these findings, the lesions were confirmed as a widespread poikilodermatous variant of dermatomyositis.

The patient was placed on a daily 50-mg dose of prednisone, which produced rapid improvement in scaling and erythema. Creatine kinase and serum aldolase levels normalized and motor strength increased. After 1 week the prednisone dosage was reduced to a daily 30-mg dose, and then 20 mg a week later. The skin lesions completely resolved within 4 to 5 months and the patient is currently on a prednisone dose of 5 mg, alternating with 2.5 mg of prednisone and rituximab infusion every 2 months.

Dermatomyositis is a rare entity with an incidence of approximately 0.5 to 1 per 100,000 individuals.1 It presents with a characteristic rash composed of Gottron papules; pathognomonic flat violaceous papules on the dorsal interphalangeal joints, elbows, or knees; and a heliotrope rash, a violaceous erythema involving the eyelids. Poikiloderma frequently is reported to present in a shawl-like distribution, encompassing the shoulders, arms, and upper back.1,2 Dermatomyositis of the poikilodermatous type can present in nonphotoexposed areas and photoexposed areas. The unusual feature is the total-body involvement, which is analogous to erythroderma.3

Our case may represent a distinct poikilodermatous manifestation sharing the distribution of the erythrodermic subtype. We believe that the skin lesions may have represented a paraneoplastic event presenting prior to diagnosis with CLL. Dermatomyositis has a strong association with cancer, with patients 3 times more likely to develop internal malignancy.4 Association is strongest for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as ovarian, lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancer. When associated with malignancy, symptoms of dermatomyositis or myositis typically precede the discovery of malignancy by an average of 1.9 years.5 Dermatomyositis has been previously reported to present as a paraneoplastic manifestation of CLL.6 One case has been reported of a patient with CLL who developed leukemia cutis presenting with poikiloderma in the characteristic dermatomyositis shawl-like distribution.7 The lack of dermal infiltration with leukemic cells in our patient, however, makes a paraneoplastic etiology much more likely.

Our patient’s rash did not initially improve with treatment of CLL, but dermatomyositis associated with hematological malignancy may precede, occur simultaneously, or follow the diagnosis of malignancy.8 Additionally, symptoms of dermatomyositis do not always parallel the course of hematological malignancy outcome. However, rituximab has been used as a treatment of dermatomyositis and may have contributed some synergistic effect in combination with prednisone in our patient.9

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL, Schwartz RA. Dermatomyositis: cutaneous manifestations of its variants. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:625-630.

- Kovacs SO, Kovacs SC. Dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:899-920; quiz 921-992.

- Liu ZH, Wang XD. Acute-onset adult dermatomyositis presenting with erythroderma and diplopia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:751-752.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, et al. Computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:255-286.

- Ishida T, Aikawa K, Tamura T, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated with nephrotic syndrome and dermatomyositis. Intern Med. 1995;34:15-17.

- Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Huang CH, et al. T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia mimicking dermatomyositis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:144-146.

- Marie I, Guillevin L, Menard JF, et al. Hematological malignancy associated with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:615-620.

- Levine TD. Rituximab in the treatment of dermatomyositis: an open-label pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:601-607.

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL, Schwartz RA. Dermatomyositis: cutaneous manifestations of its variants. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:625-630.

- Kovacs SO, Kovacs SC. Dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:899-920; quiz 921-992.

- Liu ZH, Wang XD. Acute-onset adult dermatomyositis presenting with erythroderma and diplopia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:751-752.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

- Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, et al. Computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56:255-286.

- Ishida T, Aikawa K, Tamura T, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated with nephrotic syndrome and dermatomyositis. Intern Med. 1995;34:15-17.

- Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Huang CH, et al. T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia mimicking dermatomyositis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:144-146.

- Marie I, Guillevin L, Menard JF, et al. Hematological malignancy associated with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:615-620.

- Levine TD. Rituximab in the treatment of dermatomyositis: an open-label pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:601-607.

Practice Points

- Poikiloderma, even with an unusual clinical presentation, can be a useful clinical clue for the diagnosis of dermatomyositis or other collagen vascular disease.

- Dermatomyositis can be paraneoplastic and though often associated with epithelial malignancies and solid tumors can also be associated with leukemias.

Microneedling With Platelet-Rich Plasma

Hyperpigmented Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

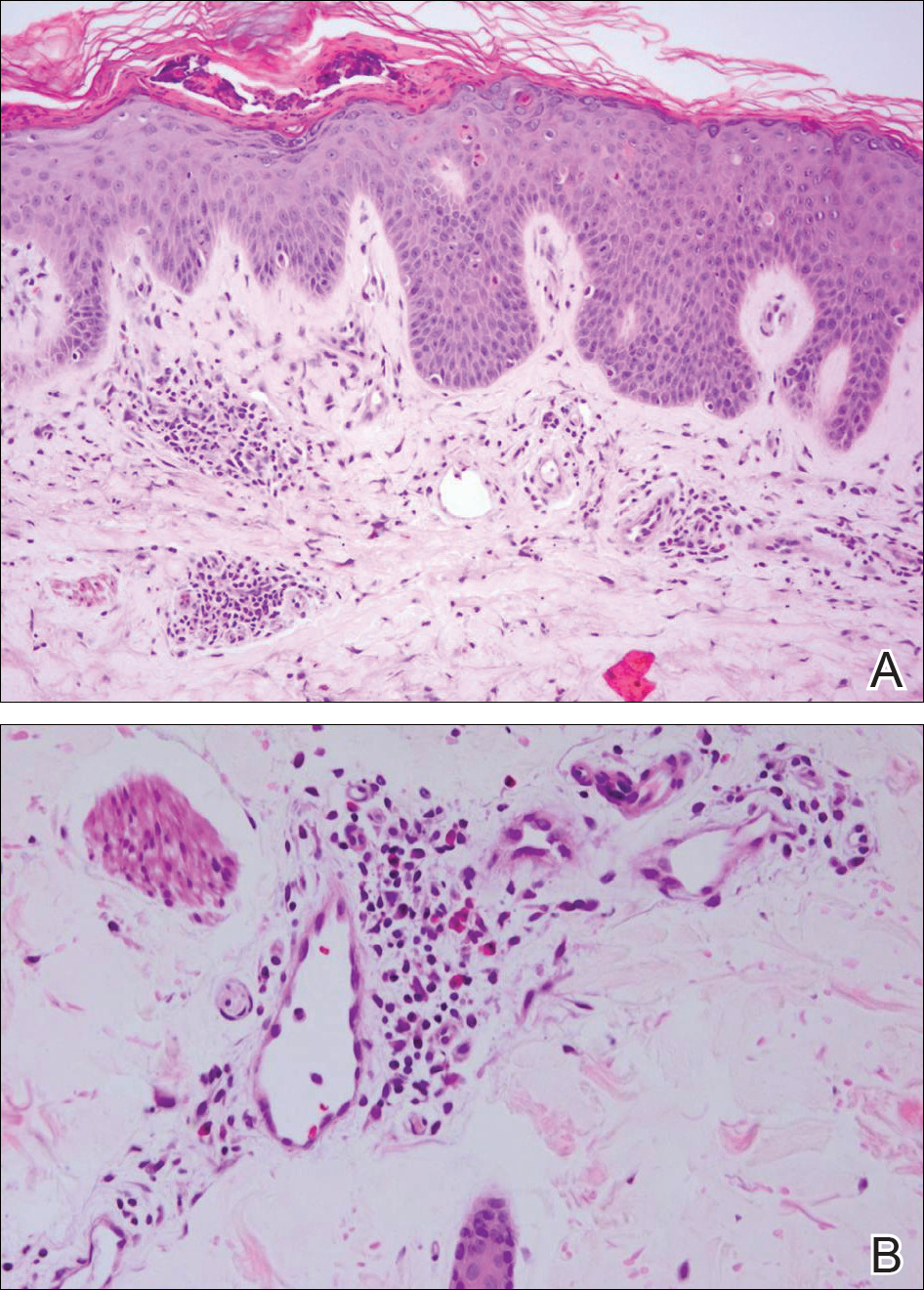

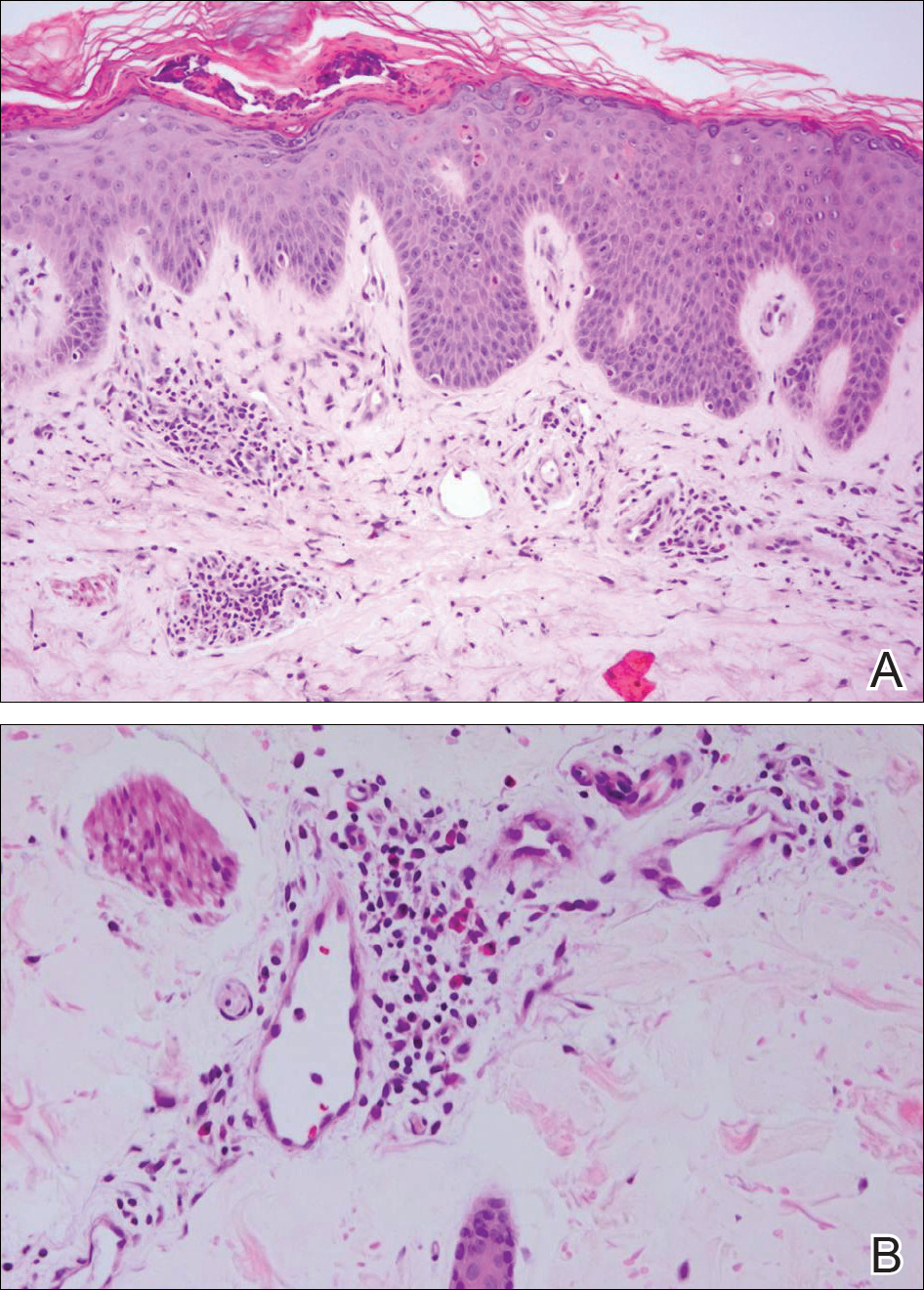

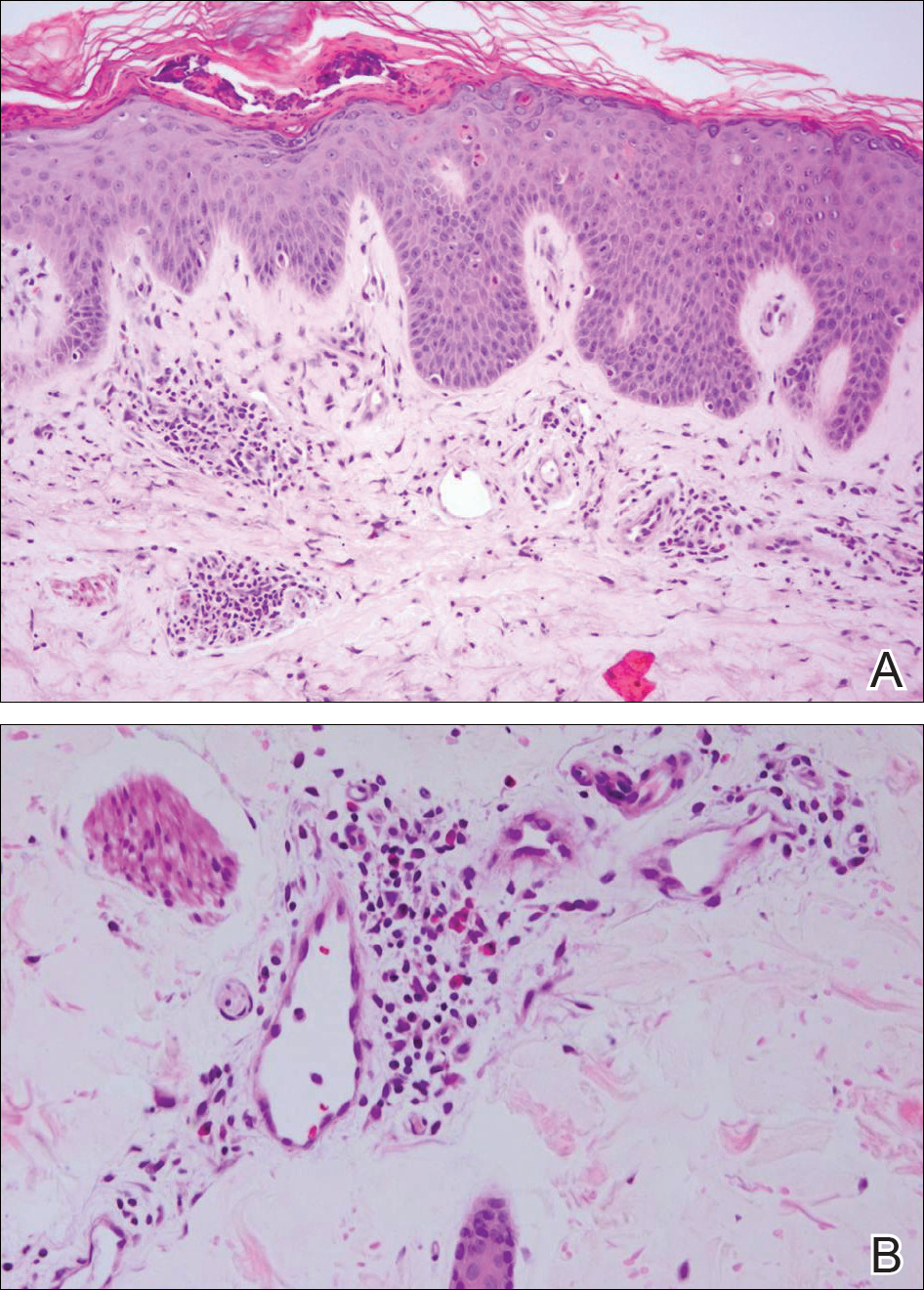

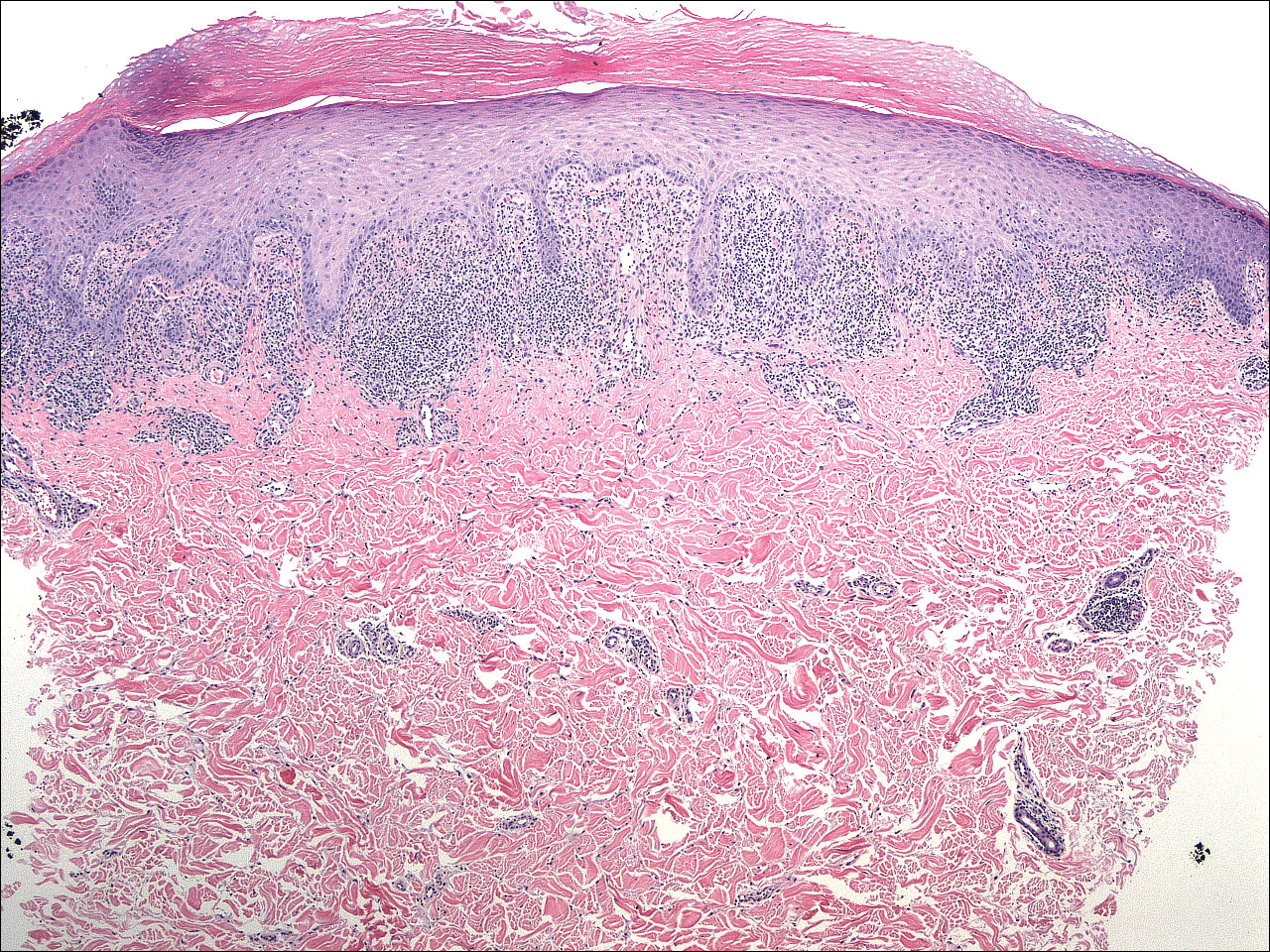

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

A 25-year-old Hispanic man with a history of juvenile idiopathic arthritis was admitted with a high-grade fever (temperature, >38.9°C) and diffuse nonlocalized abdominal pain of 2 days' duration. Physical examination revealed tachycardia, axillary lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cutaneous findings consisted of striking hyperpigmented patches on the chest and back, and hyperpigmented scaly lichenoid papules and plaques on the upper and lower extremities. The plaques on the lower extremities exhibited koebnerization. The patient reported that the eruption initially presented at 16 years of age as pruritic papules on the legs, which gradually spread to involve the arms, chest, and back. Prior treatments of juvenile idiopathic arthritis included prednisone, methotrexate, infliximab, and etanercept, though they were intermittent and temporary. Over time, the cutaneous eruption evolved into its current morphology and distribution, with periods of clearance observed while receiving systemic medications.

Telmisartan-Induced Lichen Planus Eruption Manifested on Vitiliginous Skin

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

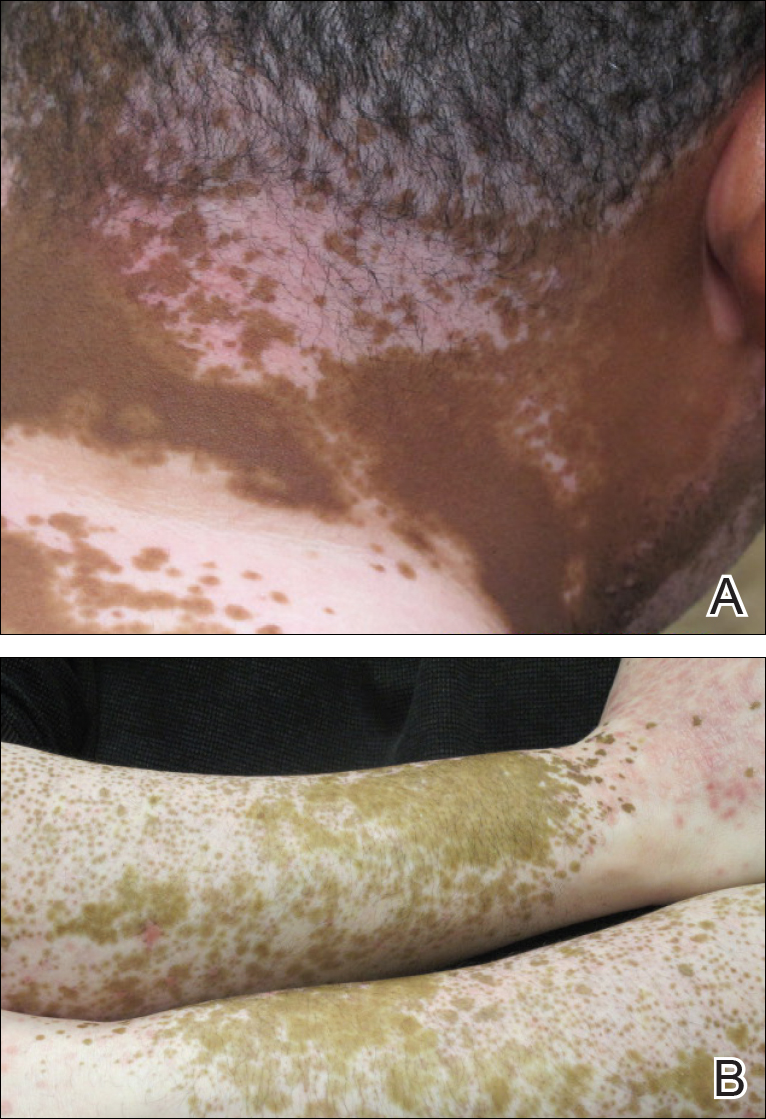

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13