User login

Med school to pay $1.2 million to students in refunds and debt cancellation in FTC settlement

Although it disputed the allegations, The complaint referenced the school’s medical license exam test pass rate and residency matches along with violations of rules that protect consumers, including those dealing with credit contracts.

The school, based in the Caribbean with operations in Illinois, agreed to pay $1.2 million toward refunds and debt cancellation for students harmed by the marketing in the past 5 years.

“While we strongly disagree with the FTC’s approach to this matter, we did not want a lengthy legal process to distract from our mission of providing a quality medical education at an affordable cost,” Kaushik Guha, executive vice president of the parent of the school, Human Resources Development Services, said in a YouTube statement posted on the school’s website.

“Saint James lured students by lying about their chances of success,” Samuel Levine, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, said in a press release. The settlement agreement was with HRDS, which bills itself as providing students from “non-traditional backgrounds the opportunity to pursue a medical degree and practice in the U.S. or Canada,” according to the school’s statement.

The complaint alleges that, since at least April 2018, the school, HRDS, and its operator Mr. Guha has lured students using “phony claims about the standardized test pass rate and students’ residency or job prospects. They lured consumers with false guarantees of student success at passing a critical medical school standardized test, the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 Exam.”

For example, a brochure distributed at open houses claimed a first-time Step 1 pass rate of about 96.8%. The brochure further claimed: “Saint James is the first and only medical school to offer a USMLE Step 1 Pass Guarantee,” according to the FTC complaint.

The FTC said the USMLE rate is lower than touted and lower than reported by other U.S. and Canadian medical schools. “Since 2017, only 35% of Saint James students who have completed the necessary coursework to take the USMLE Step 1 exam passed the test.”

The school also misrepresented the residency match rate as “the same” as American medical schools, according to the complaint. For example, the school instructed telemarketers to tell consumers that the match rate for the school’s students was 85%-90%. The school stated on its website that the residency match rate for Saint James students was 83%. “In fact, the match rate for SJSM students is lower than touted and lower than that reported by U.S. medical schools. Since 2018, defendants’ average match rate has been 63%.”

The FTC also claims the school used illegal credit contracts when marketing financing for tuition and living expenses for students. “The financing contracts contained language attempting to waive consumers’ rights under federal law and omit legally mandated disclosures.”

Saint James’ tuition ranges from about $6,650 to $9,859 per trimester, depending on campus and course study, the complaint states. Between 2016 and 2020, about 1,300 students were enrolled each year in Saint James’ schools. Students who attended the schools between 2016 and 2022 are eligible for a refund under the settlement.

Saint James is required to notify consumers whose debts are being canceled through Delta Financial Solutions, Saint James’ financing partner. The debt will also be deleted from consumers’ credit reports.

“We have chosen to settle with the FTC over its allegations that disclosures on our website and in Delta’s loan agreements were insufficient,” Mr. Guha stated on the school website. “However, we have added additional language and clarifications any time the USMLE pass rate and placement rates are mentioned.”

He said he hopes the school will be “an industry leader for transparency and accountability” and that the school’s “efforts will lead to lasting change throughout the for-profit educational industry.”

Mr. Guha added that more than 600 of the school’s alumni are serving as doctors, including many “working to bridge the health equity gap in underserved areas in North America.”

The FTC has been cracking down on deceptive practices by for-profit institutions. In October, the FTC put 70 for-profit colleges on notice that it would investigate false promises the schools make about their graduates’ job prospects, expected earnings, and other educational outcomes and would levy significant financial penalties against violators. Saint James was not on that list, which included several of the largest for-profit universities in the nation, including Capella University, DeVry University, Strayer University, and Walden University.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although it disputed the allegations, The complaint referenced the school’s medical license exam test pass rate and residency matches along with violations of rules that protect consumers, including those dealing with credit contracts.

The school, based in the Caribbean with operations in Illinois, agreed to pay $1.2 million toward refunds and debt cancellation for students harmed by the marketing in the past 5 years.

“While we strongly disagree with the FTC’s approach to this matter, we did not want a lengthy legal process to distract from our mission of providing a quality medical education at an affordable cost,” Kaushik Guha, executive vice president of the parent of the school, Human Resources Development Services, said in a YouTube statement posted on the school’s website.

“Saint James lured students by lying about their chances of success,” Samuel Levine, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, said in a press release. The settlement agreement was with HRDS, which bills itself as providing students from “non-traditional backgrounds the opportunity to pursue a medical degree and practice in the U.S. or Canada,” according to the school’s statement.

The complaint alleges that, since at least April 2018, the school, HRDS, and its operator Mr. Guha has lured students using “phony claims about the standardized test pass rate and students’ residency or job prospects. They lured consumers with false guarantees of student success at passing a critical medical school standardized test, the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 Exam.”

For example, a brochure distributed at open houses claimed a first-time Step 1 pass rate of about 96.8%. The brochure further claimed: “Saint James is the first and only medical school to offer a USMLE Step 1 Pass Guarantee,” according to the FTC complaint.

The FTC said the USMLE rate is lower than touted and lower than reported by other U.S. and Canadian medical schools. “Since 2017, only 35% of Saint James students who have completed the necessary coursework to take the USMLE Step 1 exam passed the test.”

The school also misrepresented the residency match rate as “the same” as American medical schools, according to the complaint. For example, the school instructed telemarketers to tell consumers that the match rate for the school’s students was 85%-90%. The school stated on its website that the residency match rate for Saint James students was 83%. “In fact, the match rate for SJSM students is lower than touted and lower than that reported by U.S. medical schools. Since 2018, defendants’ average match rate has been 63%.”

The FTC also claims the school used illegal credit contracts when marketing financing for tuition and living expenses for students. “The financing contracts contained language attempting to waive consumers’ rights under federal law and omit legally mandated disclosures.”

Saint James’ tuition ranges from about $6,650 to $9,859 per trimester, depending on campus and course study, the complaint states. Between 2016 and 2020, about 1,300 students were enrolled each year in Saint James’ schools. Students who attended the schools between 2016 and 2022 are eligible for a refund under the settlement.

Saint James is required to notify consumers whose debts are being canceled through Delta Financial Solutions, Saint James’ financing partner. The debt will also be deleted from consumers’ credit reports.

“We have chosen to settle with the FTC over its allegations that disclosures on our website and in Delta’s loan agreements were insufficient,” Mr. Guha stated on the school website. “However, we have added additional language and clarifications any time the USMLE pass rate and placement rates are mentioned.”

He said he hopes the school will be “an industry leader for transparency and accountability” and that the school’s “efforts will lead to lasting change throughout the for-profit educational industry.”

Mr. Guha added that more than 600 of the school’s alumni are serving as doctors, including many “working to bridge the health equity gap in underserved areas in North America.”

The FTC has been cracking down on deceptive practices by for-profit institutions. In October, the FTC put 70 for-profit colleges on notice that it would investigate false promises the schools make about their graduates’ job prospects, expected earnings, and other educational outcomes and would levy significant financial penalties against violators. Saint James was not on that list, which included several of the largest for-profit universities in the nation, including Capella University, DeVry University, Strayer University, and Walden University.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although it disputed the allegations, The complaint referenced the school’s medical license exam test pass rate and residency matches along with violations of rules that protect consumers, including those dealing with credit contracts.

The school, based in the Caribbean with operations in Illinois, agreed to pay $1.2 million toward refunds and debt cancellation for students harmed by the marketing in the past 5 years.

“While we strongly disagree with the FTC’s approach to this matter, we did not want a lengthy legal process to distract from our mission of providing a quality medical education at an affordable cost,” Kaushik Guha, executive vice president of the parent of the school, Human Resources Development Services, said in a YouTube statement posted on the school’s website.

“Saint James lured students by lying about their chances of success,” Samuel Levine, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, said in a press release. The settlement agreement was with HRDS, which bills itself as providing students from “non-traditional backgrounds the opportunity to pursue a medical degree and practice in the U.S. or Canada,” according to the school’s statement.

The complaint alleges that, since at least April 2018, the school, HRDS, and its operator Mr. Guha has lured students using “phony claims about the standardized test pass rate and students’ residency or job prospects. They lured consumers with false guarantees of student success at passing a critical medical school standardized test, the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 Exam.”

For example, a brochure distributed at open houses claimed a first-time Step 1 pass rate of about 96.8%. The brochure further claimed: “Saint James is the first and only medical school to offer a USMLE Step 1 Pass Guarantee,” according to the FTC complaint.

The FTC said the USMLE rate is lower than touted and lower than reported by other U.S. and Canadian medical schools. “Since 2017, only 35% of Saint James students who have completed the necessary coursework to take the USMLE Step 1 exam passed the test.”

The school also misrepresented the residency match rate as “the same” as American medical schools, according to the complaint. For example, the school instructed telemarketers to tell consumers that the match rate for the school’s students was 85%-90%. The school stated on its website that the residency match rate for Saint James students was 83%. “In fact, the match rate for SJSM students is lower than touted and lower than that reported by U.S. medical schools. Since 2018, defendants’ average match rate has been 63%.”

The FTC also claims the school used illegal credit contracts when marketing financing for tuition and living expenses for students. “The financing contracts contained language attempting to waive consumers’ rights under federal law and omit legally mandated disclosures.”

Saint James’ tuition ranges from about $6,650 to $9,859 per trimester, depending on campus and course study, the complaint states. Between 2016 and 2020, about 1,300 students were enrolled each year in Saint James’ schools. Students who attended the schools between 2016 and 2022 are eligible for a refund under the settlement.

Saint James is required to notify consumers whose debts are being canceled through Delta Financial Solutions, Saint James’ financing partner. The debt will also be deleted from consumers’ credit reports.

“We have chosen to settle with the FTC over its allegations that disclosures on our website and in Delta’s loan agreements were insufficient,” Mr. Guha stated on the school website. “However, we have added additional language and clarifications any time the USMLE pass rate and placement rates are mentioned.”

He said he hopes the school will be “an industry leader for transparency and accountability” and that the school’s “efforts will lead to lasting change throughout the for-profit educational industry.”

Mr. Guha added that more than 600 of the school’s alumni are serving as doctors, including many “working to bridge the health equity gap in underserved areas in North America.”

The FTC has been cracking down on deceptive practices by for-profit institutions. In October, the FTC put 70 for-profit colleges on notice that it would investigate false promises the schools make about their graduates’ job prospects, expected earnings, and other educational outcomes and would levy significant financial penalties against violators. Saint James was not on that list, which included several of the largest for-profit universities in the nation, including Capella University, DeVry University, Strayer University, and Walden University.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York NPs join half of states with full practice authority

according to leading national nurse organizations.

New York joins 24 other states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories that have adopted FPA legislation, as reported by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Like other states, New York has been under an emergency order during the pandemic that allowed NPs to practice to their full authority because of staffing shortages. That order was extended multiple times and was expected to expire this month, AANP reports.

“This has been in the making for nurse practitioners in New York since 2014, trying to get full practice authority,” Michelle Jones, RN, MSN, ANP-C, director at large for the New York State Nurses Association, said in an interview.

NPs who were allowed to practice independently during the pandemic campaigned for that provision to become permanent once the emergency order expired, she said. Ms. Jones explained that the FPA law expands the scope of practice and “removes unnecessary barriers,” namely an agreement with doctors to oversee NPs’ actions.

FPA gives NPs the authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments – including prescribing medications – without oversight by a doctor or state medical board, according to AANP.

Before the pandemic, New York NPs had “reduced” practice authority with those who had more than 3,600 hours of experience required to maintain a collaborative practice agreement with doctors and those with less experience maintaining a written agreement. The change gives full practice authority to those with more than 3,600 hours of experience, Stephen A. Ferrara, DNP, FNP-BC, AANP regional director, said in an interview.

Ferrara, who practices in New York, said the state is the largest to change to FPA. He said the state and others that have moved to FPA have determined that there “has been no lapse in quality care” during the emergency order period and that the regulatory barriers kept NPs from providing access to care.

Jones said that the law also will allow NPs to open private practices and serve underserved patients in areas that lack access to health care. “This is a step to improve access to health care and health equity of the New York population.”

It’s been a while since another state passed FPA legislation, Massachusetts in January 2021 and Delaware in August 2021, according to AANP.

Earlier this month, AANP released new data showing a 9% increase in NPs licensed to practice in the United States, rising from 325,000 in May 2021 to 355,000.

The New York legislation “will help New York attract and retain nurse practitioners and provide New Yorkers better access to quality care,” AANP President April Kapu, DNP, APRN, said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to leading national nurse organizations.

New York joins 24 other states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories that have adopted FPA legislation, as reported by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Like other states, New York has been under an emergency order during the pandemic that allowed NPs to practice to their full authority because of staffing shortages. That order was extended multiple times and was expected to expire this month, AANP reports.

“This has been in the making for nurse practitioners in New York since 2014, trying to get full practice authority,” Michelle Jones, RN, MSN, ANP-C, director at large for the New York State Nurses Association, said in an interview.

NPs who were allowed to practice independently during the pandemic campaigned for that provision to become permanent once the emergency order expired, she said. Ms. Jones explained that the FPA law expands the scope of practice and “removes unnecessary barriers,” namely an agreement with doctors to oversee NPs’ actions.

FPA gives NPs the authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments – including prescribing medications – without oversight by a doctor or state medical board, according to AANP.

Before the pandemic, New York NPs had “reduced” practice authority with those who had more than 3,600 hours of experience required to maintain a collaborative practice agreement with doctors and those with less experience maintaining a written agreement. The change gives full practice authority to those with more than 3,600 hours of experience, Stephen A. Ferrara, DNP, FNP-BC, AANP regional director, said in an interview.

Ferrara, who practices in New York, said the state is the largest to change to FPA. He said the state and others that have moved to FPA have determined that there “has been no lapse in quality care” during the emergency order period and that the regulatory barriers kept NPs from providing access to care.

Jones said that the law also will allow NPs to open private practices and serve underserved patients in areas that lack access to health care. “This is a step to improve access to health care and health equity of the New York population.”

It’s been a while since another state passed FPA legislation, Massachusetts in January 2021 and Delaware in August 2021, according to AANP.

Earlier this month, AANP released new data showing a 9% increase in NPs licensed to practice in the United States, rising from 325,000 in May 2021 to 355,000.

The New York legislation “will help New York attract and retain nurse practitioners and provide New Yorkers better access to quality care,” AANP President April Kapu, DNP, APRN, said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to leading national nurse organizations.

New York joins 24 other states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories that have adopted FPA legislation, as reported by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). Like other states, New York has been under an emergency order during the pandemic that allowed NPs to practice to their full authority because of staffing shortages. That order was extended multiple times and was expected to expire this month, AANP reports.

“This has been in the making for nurse practitioners in New York since 2014, trying to get full practice authority,” Michelle Jones, RN, MSN, ANP-C, director at large for the New York State Nurses Association, said in an interview.

NPs who were allowed to practice independently during the pandemic campaigned for that provision to become permanent once the emergency order expired, she said. Ms. Jones explained that the FPA law expands the scope of practice and “removes unnecessary barriers,” namely an agreement with doctors to oversee NPs’ actions.

FPA gives NPs the authority to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments – including prescribing medications – without oversight by a doctor or state medical board, according to AANP.

Before the pandemic, New York NPs had “reduced” practice authority with those who had more than 3,600 hours of experience required to maintain a collaborative practice agreement with doctors and those with less experience maintaining a written agreement. The change gives full practice authority to those with more than 3,600 hours of experience, Stephen A. Ferrara, DNP, FNP-BC, AANP regional director, said in an interview.

Ferrara, who practices in New York, said the state is the largest to change to FPA. He said the state and others that have moved to FPA have determined that there “has been no lapse in quality care” during the emergency order period and that the regulatory barriers kept NPs from providing access to care.

Jones said that the law also will allow NPs to open private practices and serve underserved patients in areas that lack access to health care. “This is a step to improve access to health care and health equity of the New York population.”

It’s been a while since another state passed FPA legislation, Massachusetts in January 2021 and Delaware in August 2021, according to AANP.

Earlier this month, AANP released new data showing a 9% increase in NPs licensed to practice in the United States, rising from 325,000 in May 2021 to 355,000.

The New York legislation “will help New York attract and retain nurse practitioners and provide New Yorkers better access to quality care,” AANP President April Kapu, DNP, APRN, said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

University of Washington, Harvard ranked top medical schools for second year

It may seem like déjà vu, as not much has changed regarding the rankings of top U.S. medical schools over the past 2 years.

The University of Washington, Seattle retained its ranking from the U.S. News & World Report as the top medical school for primary care for 2023. Also repeating its 2022 standing as the top medical school for research is Harvard University.

In the primary care ranking, the top 10 schools after the University of Washington were the University of California, San Francisco; the University of Minnesota; Oregon Health and Science University; the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; the University of Colorado; the University of Nebraska Medical Center; the University of California, Davis; and Harvard. Three schools tied for the no. 10 slot: the University of Kansas Medical Center, the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical Center, and the University of Pittsburgh.

The top five schools with the most graduates practicing in primary care specialties are Des Moines University, Iowa (50.6%); the University of Pikeville (Ky.) (46.8%); Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California (46%); William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Hattiesburg, Mississippi (44.7%); and A.T. Still University of Health Sciences, Kirksville, Missouri (44.3%).

Best for research

When it comes to schools ranking the highest for research, the Grossman School of Medicine at New York University takes the no. 2 spot after Harvard. Three schools were tied for the no. 3 spot: Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of California, San Francisco; and two schools for no. 6: Duke University and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. No. 8 goes to Stanford University, followed by the University of Washington. Rounding out the top 10 is Yale University.

Specialty ranks

The top-ranked schools in eight specialties are as follows:

- Anesthesiology: Harvard

- Family medicine: the University of Washington

- Internal medicine: Johns Hopkins

- Obstetrics/gynecology: Harvard

- Pediatrics: the University of Pennsylvania (Perelman)

- Psychiatry: Harvard

- Radiology: Johns Hopkins

- Surgery: Harvard

Most diverse student body

If you’re looking for a school with significant minority representation, Howard University, Washington, D.C., ranked highest (76.8%), followed by the Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University, Miami (43.2%). The University of California, Davis (40%), Sacramento, California, and the University of Vermont (Larner), Burlington (14.1%), tied for third.

Three southern schools take top honors for the most graduates practicing in underserved areas, starting with the University of South Carolina (70.9%), followed by the University of Mississippi (66.2%), and East Tennessee State University (Quillen), Johnson City, Tennessee (65.8%).

The colleges with the most graduates practicing in rural areas are William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine (28%), the University of Pikesville (25.6%), and the University of Mississippi (22.1%).

College debt

The medical school where graduates have the most debt is Nova Southeastern University Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Graduates incurred an average debt of $309,206. Western University of Health Sciences graduates racked up $276,840 in debt, followed by graduates of West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine, owing $268,416.

Ranking criteria

Each year, U.S. News ranks hundreds of U.S. colleges and universities. Medical schools fall under the rankings for best graduate schools.

U.S. News surveyed 192 medical and osteopathic schools accredited in 2021 by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education or the American Osteopathic Association. Among the schools surveyed in fall 2021 and early 2022, 130 schools responded. Of those, 124 were included in both the research and primary care rankings.

The criteria for ranking include faculty resources, academic achievements of entering students, and qualitative assessments by schools and residency directors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It may seem like déjà vu, as not much has changed regarding the rankings of top U.S. medical schools over the past 2 years.

The University of Washington, Seattle retained its ranking from the U.S. News & World Report as the top medical school for primary care for 2023. Also repeating its 2022 standing as the top medical school for research is Harvard University.

In the primary care ranking, the top 10 schools after the University of Washington were the University of California, San Francisco; the University of Minnesota; Oregon Health and Science University; the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; the University of Colorado; the University of Nebraska Medical Center; the University of California, Davis; and Harvard. Three schools tied for the no. 10 slot: the University of Kansas Medical Center, the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical Center, and the University of Pittsburgh.

The top five schools with the most graduates practicing in primary care specialties are Des Moines University, Iowa (50.6%); the University of Pikeville (Ky.) (46.8%); Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California (46%); William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Hattiesburg, Mississippi (44.7%); and A.T. Still University of Health Sciences, Kirksville, Missouri (44.3%).

Best for research

When it comes to schools ranking the highest for research, the Grossman School of Medicine at New York University takes the no. 2 spot after Harvard. Three schools were tied for the no. 3 spot: Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of California, San Francisco; and two schools for no. 6: Duke University and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. No. 8 goes to Stanford University, followed by the University of Washington. Rounding out the top 10 is Yale University.

Specialty ranks

The top-ranked schools in eight specialties are as follows:

- Anesthesiology: Harvard

- Family medicine: the University of Washington

- Internal medicine: Johns Hopkins

- Obstetrics/gynecology: Harvard

- Pediatrics: the University of Pennsylvania (Perelman)

- Psychiatry: Harvard

- Radiology: Johns Hopkins

- Surgery: Harvard

Most diverse student body

If you’re looking for a school with significant minority representation, Howard University, Washington, D.C., ranked highest (76.8%), followed by the Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University, Miami (43.2%). The University of California, Davis (40%), Sacramento, California, and the University of Vermont (Larner), Burlington (14.1%), tied for third.

Three southern schools take top honors for the most graduates practicing in underserved areas, starting with the University of South Carolina (70.9%), followed by the University of Mississippi (66.2%), and East Tennessee State University (Quillen), Johnson City, Tennessee (65.8%).

The colleges with the most graduates practicing in rural areas are William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine (28%), the University of Pikesville (25.6%), and the University of Mississippi (22.1%).

College debt

The medical school where graduates have the most debt is Nova Southeastern University Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Graduates incurred an average debt of $309,206. Western University of Health Sciences graduates racked up $276,840 in debt, followed by graduates of West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine, owing $268,416.

Ranking criteria

Each year, U.S. News ranks hundreds of U.S. colleges and universities. Medical schools fall under the rankings for best graduate schools.

U.S. News surveyed 192 medical and osteopathic schools accredited in 2021 by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education or the American Osteopathic Association. Among the schools surveyed in fall 2021 and early 2022, 130 schools responded. Of those, 124 were included in both the research and primary care rankings.

The criteria for ranking include faculty resources, academic achievements of entering students, and qualitative assessments by schools and residency directors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It may seem like déjà vu, as not much has changed regarding the rankings of top U.S. medical schools over the past 2 years.

The University of Washington, Seattle retained its ranking from the U.S. News & World Report as the top medical school for primary care for 2023. Also repeating its 2022 standing as the top medical school for research is Harvard University.

In the primary care ranking, the top 10 schools after the University of Washington were the University of California, San Francisco; the University of Minnesota; Oregon Health and Science University; the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; the University of Colorado; the University of Nebraska Medical Center; the University of California, Davis; and Harvard. Three schools tied for the no. 10 slot: the University of Kansas Medical Center, the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical Center, and the University of Pittsburgh.

The top five schools with the most graduates practicing in primary care specialties are Des Moines University, Iowa (50.6%); the University of Pikeville (Ky.) (46.8%); Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California (46%); William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Hattiesburg, Mississippi (44.7%); and A.T. Still University of Health Sciences, Kirksville, Missouri (44.3%).

Best for research

When it comes to schools ranking the highest for research, the Grossman School of Medicine at New York University takes the no. 2 spot after Harvard. Three schools were tied for the no. 3 spot: Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of California, San Francisco; and two schools for no. 6: Duke University and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. No. 8 goes to Stanford University, followed by the University of Washington. Rounding out the top 10 is Yale University.

Specialty ranks

The top-ranked schools in eight specialties are as follows:

- Anesthesiology: Harvard

- Family medicine: the University of Washington

- Internal medicine: Johns Hopkins

- Obstetrics/gynecology: Harvard

- Pediatrics: the University of Pennsylvania (Perelman)

- Psychiatry: Harvard

- Radiology: Johns Hopkins

- Surgery: Harvard

Most diverse student body

If you’re looking for a school with significant minority representation, Howard University, Washington, D.C., ranked highest (76.8%), followed by the Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University, Miami (43.2%). The University of California, Davis (40%), Sacramento, California, and the University of Vermont (Larner), Burlington (14.1%), tied for third.

Three southern schools take top honors for the most graduates practicing in underserved areas, starting with the University of South Carolina (70.9%), followed by the University of Mississippi (66.2%), and East Tennessee State University (Quillen), Johnson City, Tennessee (65.8%).

The colleges with the most graduates practicing in rural areas are William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine (28%), the University of Pikesville (25.6%), and the University of Mississippi (22.1%).

College debt

The medical school where graduates have the most debt is Nova Southeastern University Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Graduates incurred an average debt of $309,206. Western University of Health Sciences graduates racked up $276,840 in debt, followed by graduates of West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine, owing $268,416.

Ranking criteria

Each year, U.S. News ranks hundreds of U.S. colleges and universities. Medical schools fall under the rankings for best graduate schools.

U.S. News surveyed 192 medical and osteopathic schools accredited in 2021 by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education or the American Osteopathic Association. Among the schools surveyed in fall 2021 and early 2022, 130 schools responded. Of those, 124 were included in both the research and primary care rankings.

The criteria for ranking include faculty resources, academic achievements of entering students, and qualitative assessments by schools and residency directors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The power of the pause to prevent diagnostic error

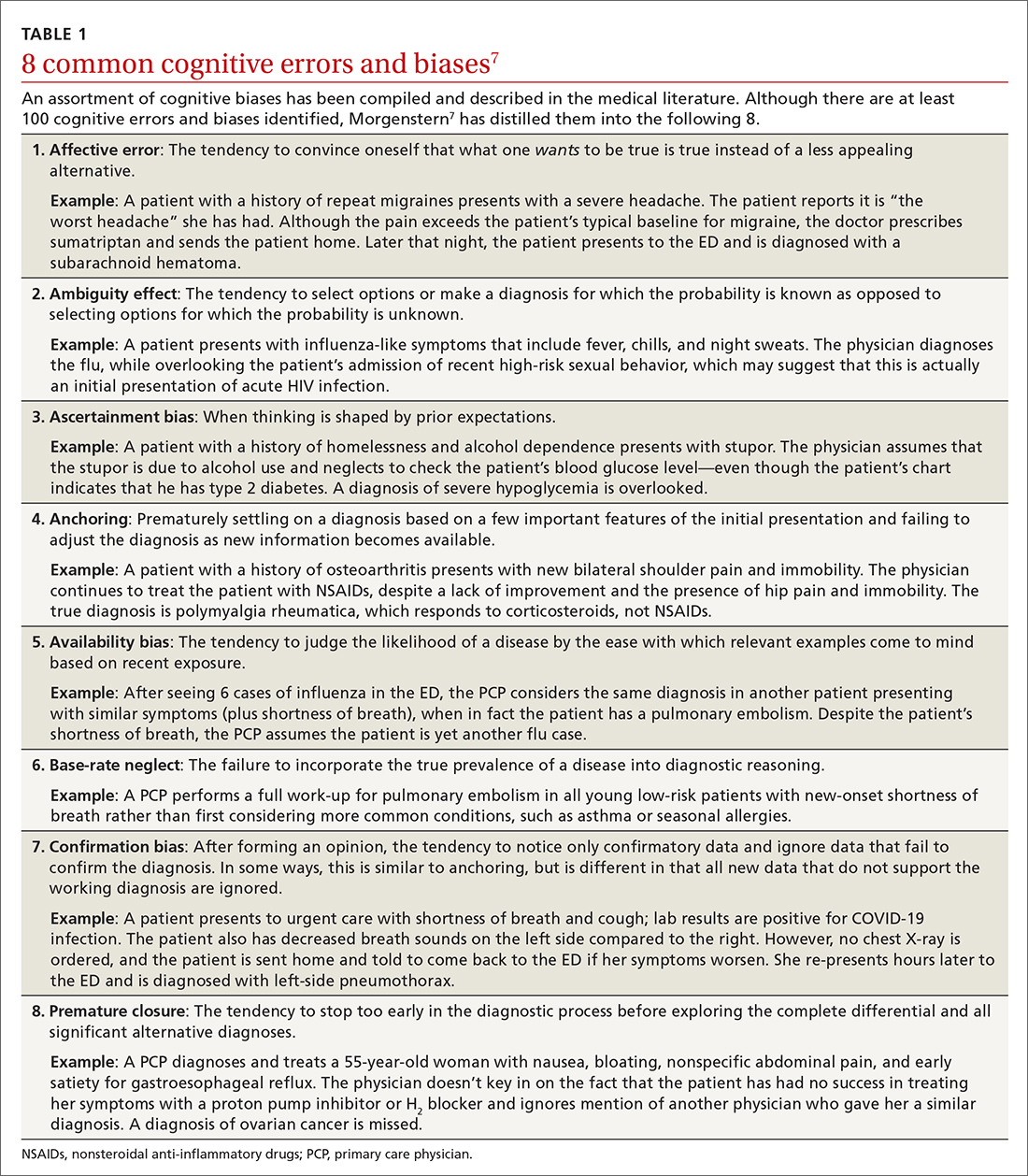

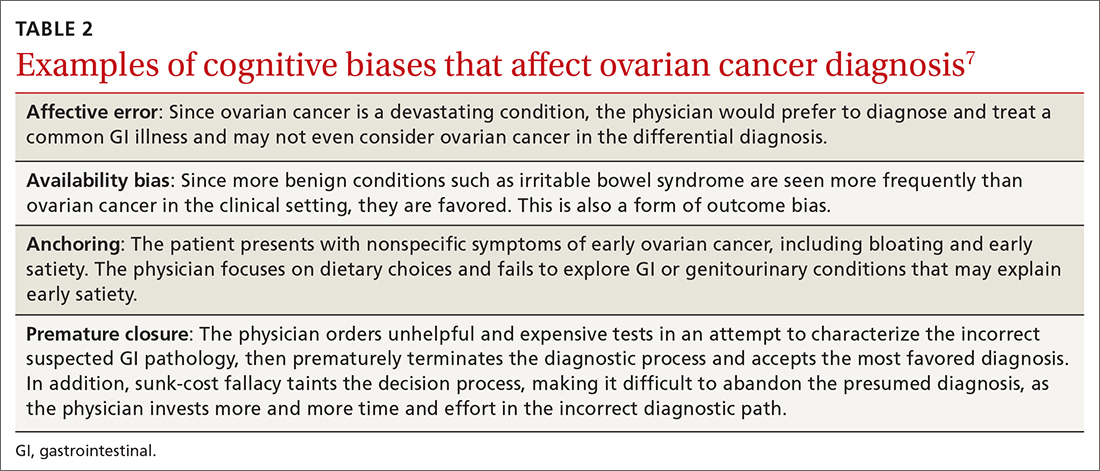

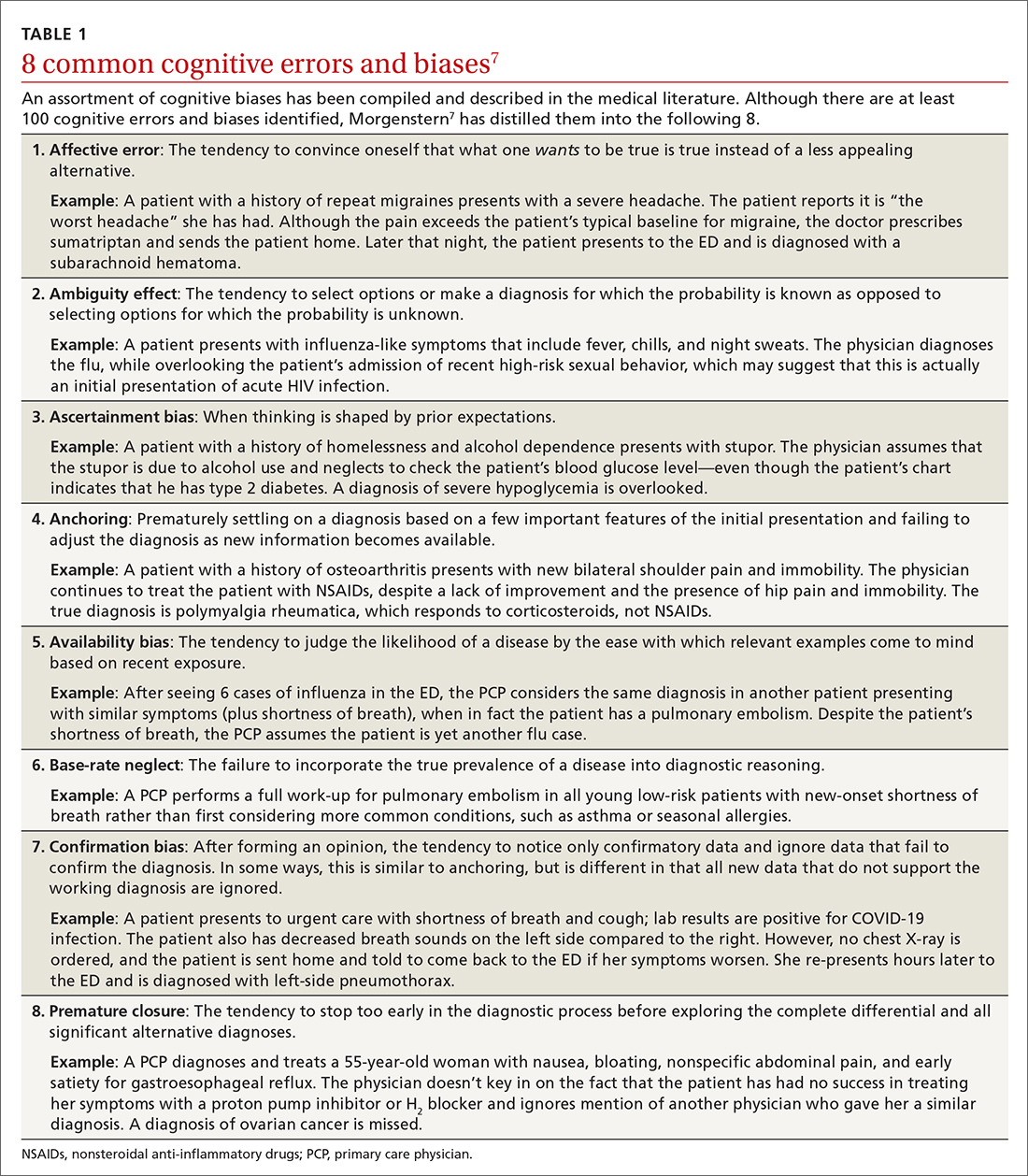

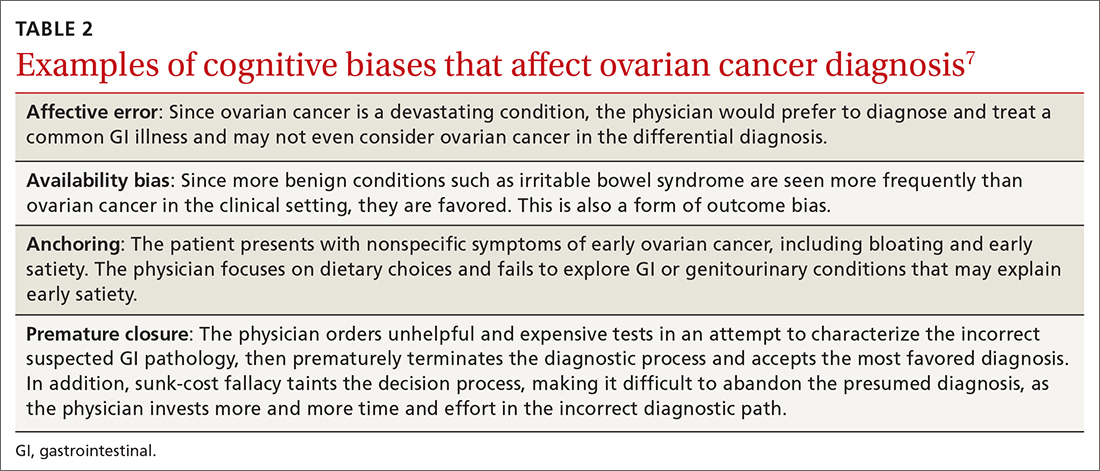

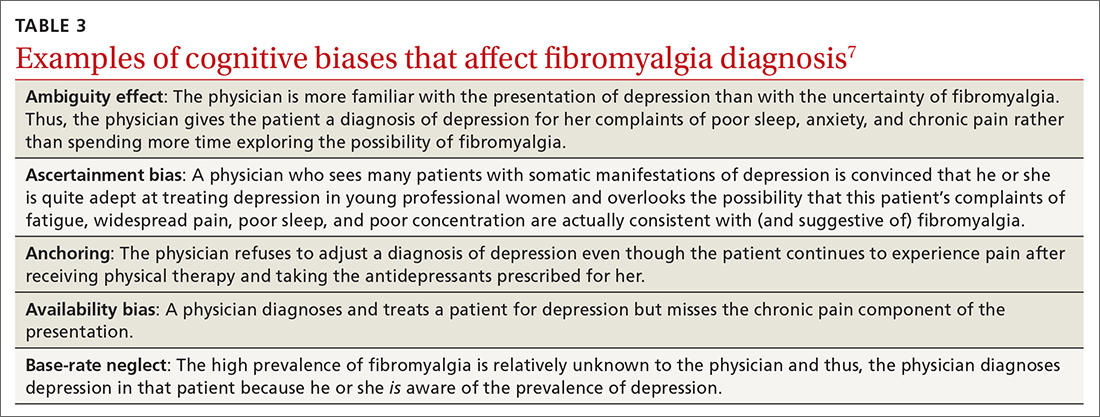

None of us like being wrong, especially about a patient’s diagnosis. To help you avoid diagnostic errors for 4 difficult diagnoses, read and study the article in this issue of JFP by Rosen and colleagues.1 They discuss misdiagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica, fibromyalgia, ovarian cancer, and Lewy body dementia to illustrate how we can go astray if we do not take care to pause and think through things carefully. They point out that, for quick and mostly accurate diagnoses, pattern recognition or type 1 thinking serves us well in a busy office practice. However, we must frequently pause and reflect, using type 2 thinking—especially when the puzzle pieces don’t quite fit together.

I still recall vividly a diagnostic error I made many years ago. One of my patients, whom I had diagnosed and was treating for hyperlipidemia, returned for follow-up while I was on vacation. My partner conducted the follow-up visit. To my chagrin, he noticed her puffy face and weight gain and ordered thyroid studies. Sure enough, my patient was severely hypothyroid, and her lipid levels normalized with thyroid replacement therapy.

A happier tale for me was making the correct diagnosis for a woman with chronic cough. She had been evaluated by multiple specialists during the prior year and treated with a nasal steroid for allergies, a proton pump inhibitor for reflux, and a steroid inhaler for possible asthma. None of these relieved her cough. After reviewing her medication list and noting that it included amitriptyline, which has anticholinergic adverse effects, I recommended she stop taking that medication and the cough resolved.

John Ely, MD, MPH, a family physician who has spent his academic career investigating causes of and solutions to diagnostic errors, has outlined important steps we can take. These include: (1) obtaining your own complete medical history, (2) performing a “focused and purposeful” physical exam, (3) generating initial hypotheses and differentiating them through additional history taking, exams, and diagnostic tests, (4) pausing to reflect [my emphasis], and (5) embarking on a plan (while acknowledging uncertainty) and ensuring there is a pathway for follow-up.2

To help avoid diagnostic errors, Dr. Ely developed and uses a set of checklists that cover the differential diagnosis for 72 presenting complaints/conditions, including syncope, back pain, insomnia, and headache.2 When you are faced with diagnostic uncertainty, it takes just a few minutes to run through the checklist for the patient’s presenting complaint.

1. Rosen PD, Klenzak S, Baptista S. Diagnostic challenges in primary care: identifying and avoiding cognitive bias. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:124-132.

2. Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Acad Med. 2011;86:307-313. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820824cd

None of us like being wrong, especially about a patient’s diagnosis. To help you avoid diagnostic errors for 4 difficult diagnoses, read and study the article in this issue of JFP by Rosen and colleagues.1 They discuss misdiagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica, fibromyalgia, ovarian cancer, and Lewy body dementia to illustrate how we can go astray if we do not take care to pause and think through things carefully. They point out that, for quick and mostly accurate diagnoses, pattern recognition or type 1 thinking serves us well in a busy office practice. However, we must frequently pause and reflect, using type 2 thinking—especially when the puzzle pieces don’t quite fit together.

I still recall vividly a diagnostic error I made many years ago. One of my patients, whom I had diagnosed and was treating for hyperlipidemia, returned for follow-up while I was on vacation. My partner conducted the follow-up visit. To my chagrin, he noticed her puffy face and weight gain and ordered thyroid studies. Sure enough, my patient was severely hypothyroid, and her lipid levels normalized with thyroid replacement therapy.

A happier tale for me was making the correct diagnosis for a woman with chronic cough. She had been evaluated by multiple specialists during the prior year and treated with a nasal steroid for allergies, a proton pump inhibitor for reflux, and a steroid inhaler for possible asthma. None of these relieved her cough. After reviewing her medication list and noting that it included amitriptyline, which has anticholinergic adverse effects, I recommended she stop taking that medication and the cough resolved.

John Ely, MD, MPH, a family physician who has spent his academic career investigating causes of and solutions to diagnostic errors, has outlined important steps we can take. These include: (1) obtaining your own complete medical history, (2) performing a “focused and purposeful” physical exam, (3) generating initial hypotheses and differentiating them through additional history taking, exams, and diagnostic tests, (4) pausing to reflect [my emphasis], and (5) embarking on a plan (while acknowledging uncertainty) and ensuring there is a pathway for follow-up.2

To help avoid diagnostic errors, Dr. Ely developed and uses a set of checklists that cover the differential diagnosis for 72 presenting complaints/conditions, including syncope, back pain, insomnia, and headache.2 When you are faced with diagnostic uncertainty, it takes just a few minutes to run through the checklist for the patient’s presenting complaint.

None of us like being wrong, especially about a patient’s diagnosis. To help you avoid diagnostic errors for 4 difficult diagnoses, read and study the article in this issue of JFP by Rosen and colleagues.1 They discuss misdiagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica, fibromyalgia, ovarian cancer, and Lewy body dementia to illustrate how we can go astray if we do not take care to pause and think through things carefully. They point out that, for quick and mostly accurate diagnoses, pattern recognition or type 1 thinking serves us well in a busy office practice. However, we must frequently pause and reflect, using type 2 thinking—especially when the puzzle pieces don’t quite fit together.

I still recall vividly a diagnostic error I made many years ago. One of my patients, whom I had diagnosed and was treating for hyperlipidemia, returned for follow-up while I was on vacation. My partner conducted the follow-up visit. To my chagrin, he noticed her puffy face and weight gain and ordered thyroid studies. Sure enough, my patient was severely hypothyroid, and her lipid levels normalized with thyroid replacement therapy.

A happier tale for me was making the correct diagnosis for a woman with chronic cough. She had been evaluated by multiple specialists during the prior year and treated with a nasal steroid for allergies, a proton pump inhibitor for reflux, and a steroid inhaler for possible asthma. None of these relieved her cough. After reviewing her medication list and noting that it included amitriptyline, which has anticholinergic adverse effects, I recommended she stop taking that medication and the cough resolved.

John Ely, MD, MPH, a family physician who has spent his academic career investigating causes of and solutions to diagnostic errors, has outlined important steps we can take. These include: (1) obtaining your own complete medical history, (2) performing a “focused and purposeful” physical exam, (3) generating initial hypotheses and differentiating them through additional history taking, exams, and diagnostic tests, (4) pausing to reflect [my emphasis], and (5) embarking on a plan (while acknowledging uncertainty) and ensuring there is a pathway for follow-up.2

To help avoid diagnostic errors, Dr. Ely developed and uses a set of checklists that cover the differential diagnosis for 72 presenting complaints/conditions, including syncope, back pain, insomnia, and headache.2 When you are faced with diagnostic uncertainty, it takes just a few minutes to run through the checklist for the patient’s presenting complaint.

1. Rosen PD, Klenzak S, Baptista S. Diagnostic challenges in primary care: identifying and avoiding cognitive bias. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:124-132.

2. Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Acad Med. 2011;86:307-313. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820824cd

1. Rosen PD, Klenzak S, Baptista S. Diagnostic challenges in primary care: identifying and avoiding cognitive bias. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:124-132.

2. Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Acad Med. 2011;86:307-313. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820824cd

Medical assistants identify strategies and barriers to clinic efficiency

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

Continue to: We developed and piloted...

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

RESULTS

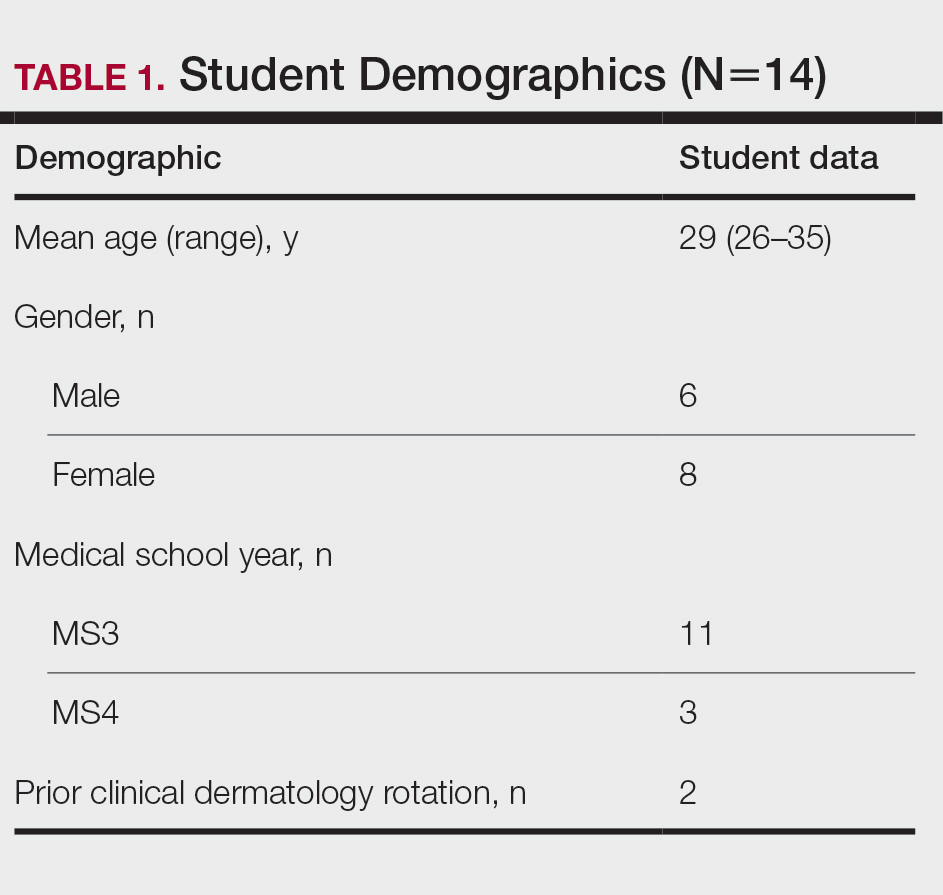

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Continue to: Efficiency and competing priorities

Efficiency and competing priorities

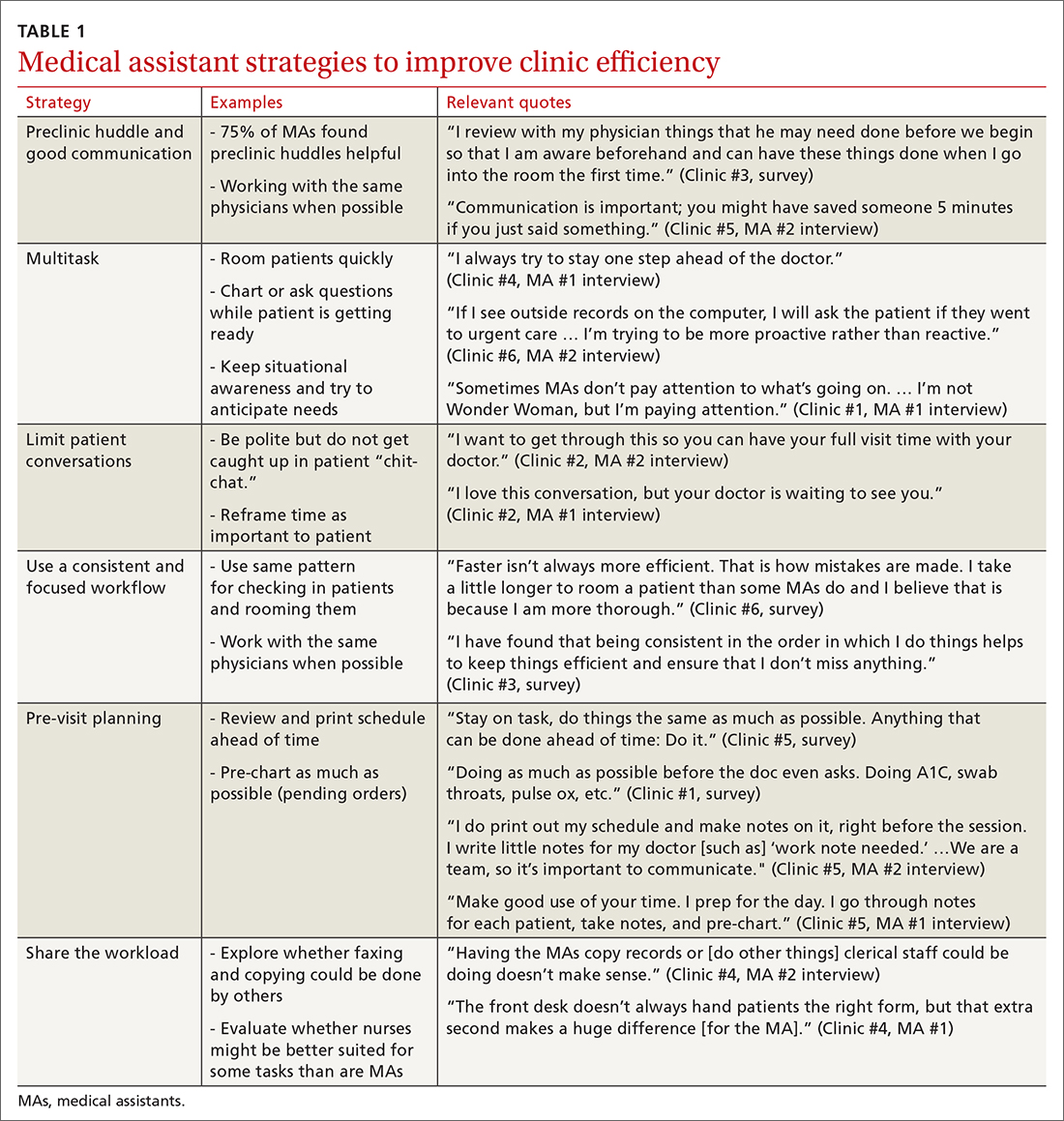

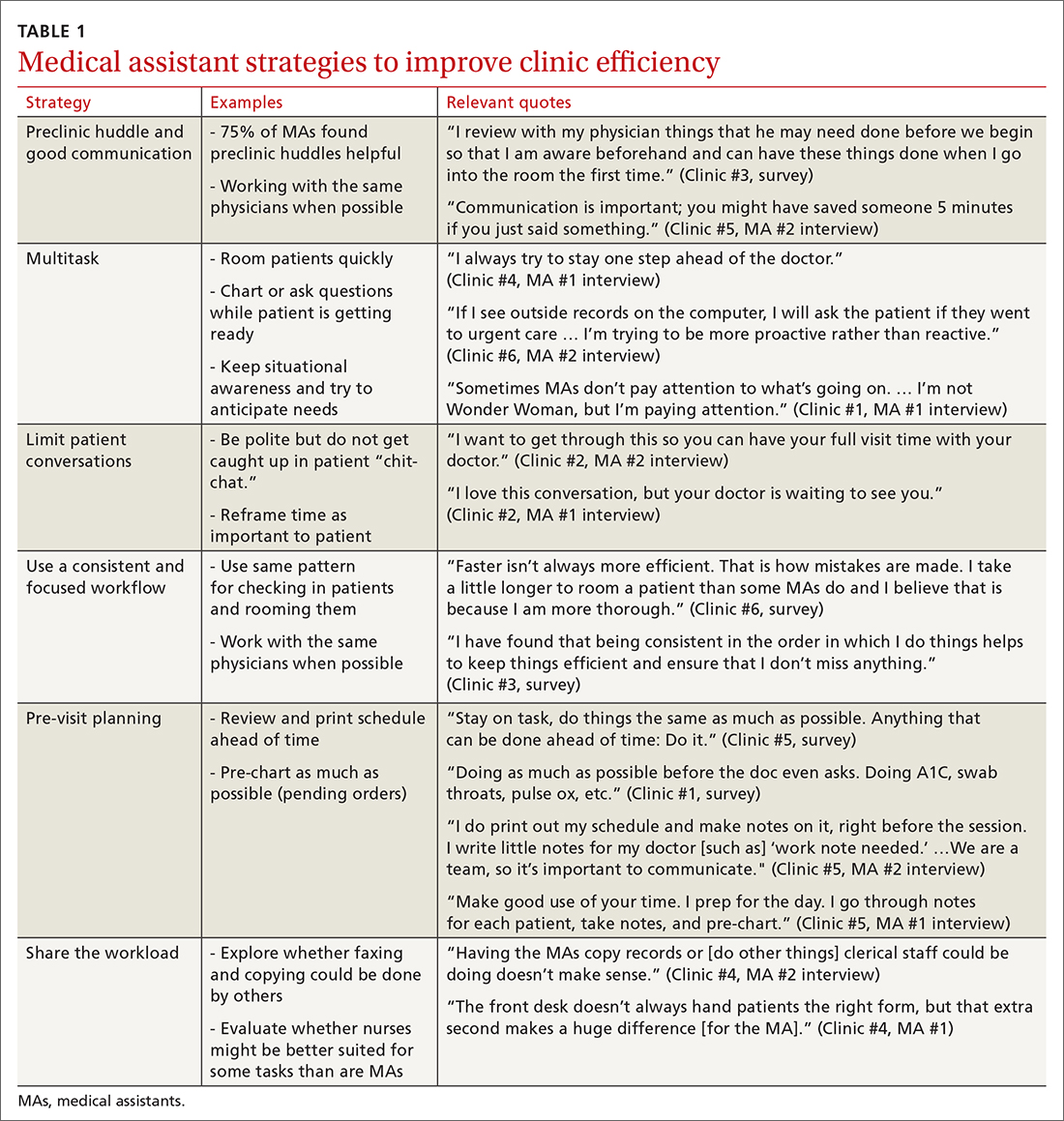

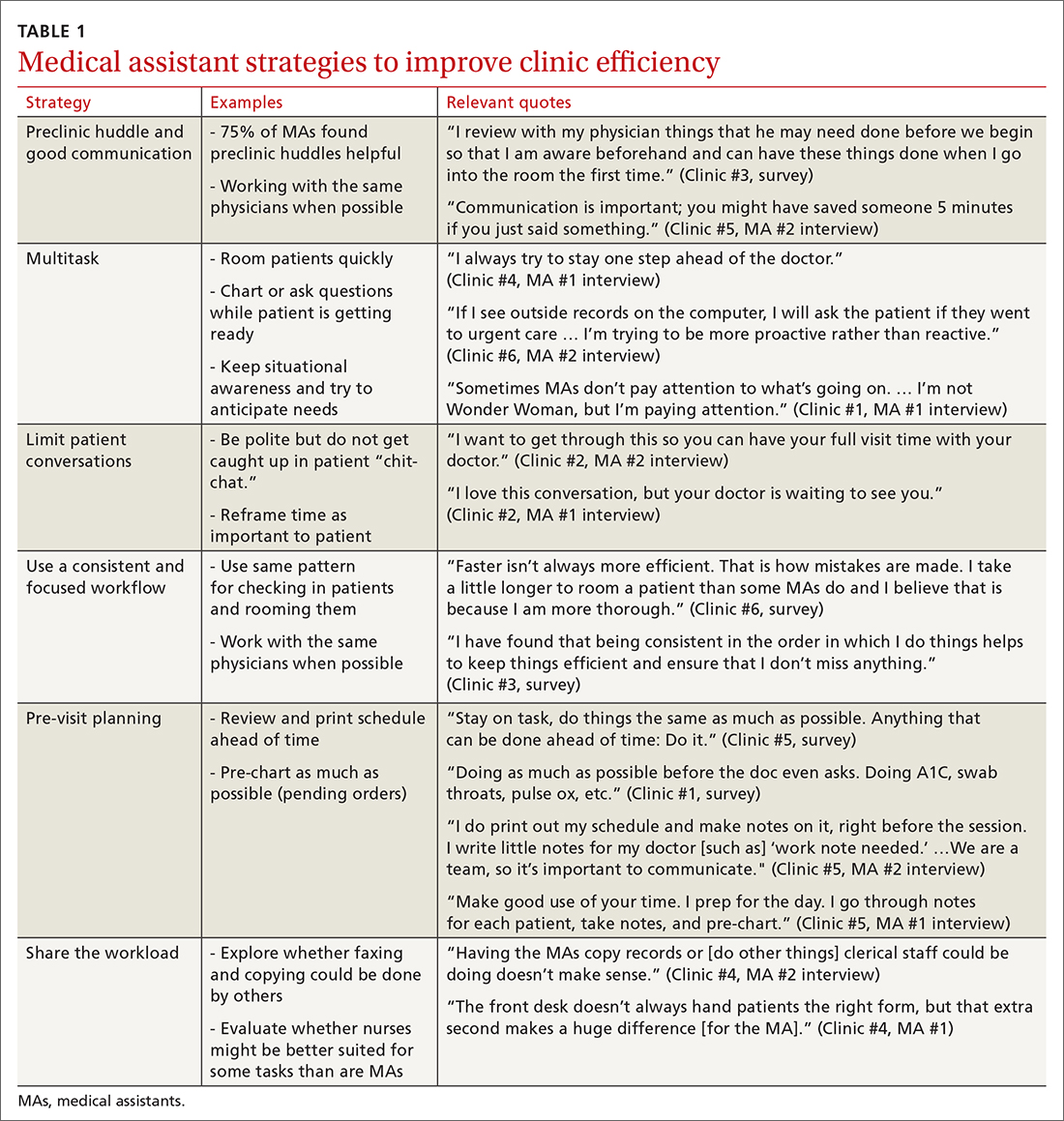

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

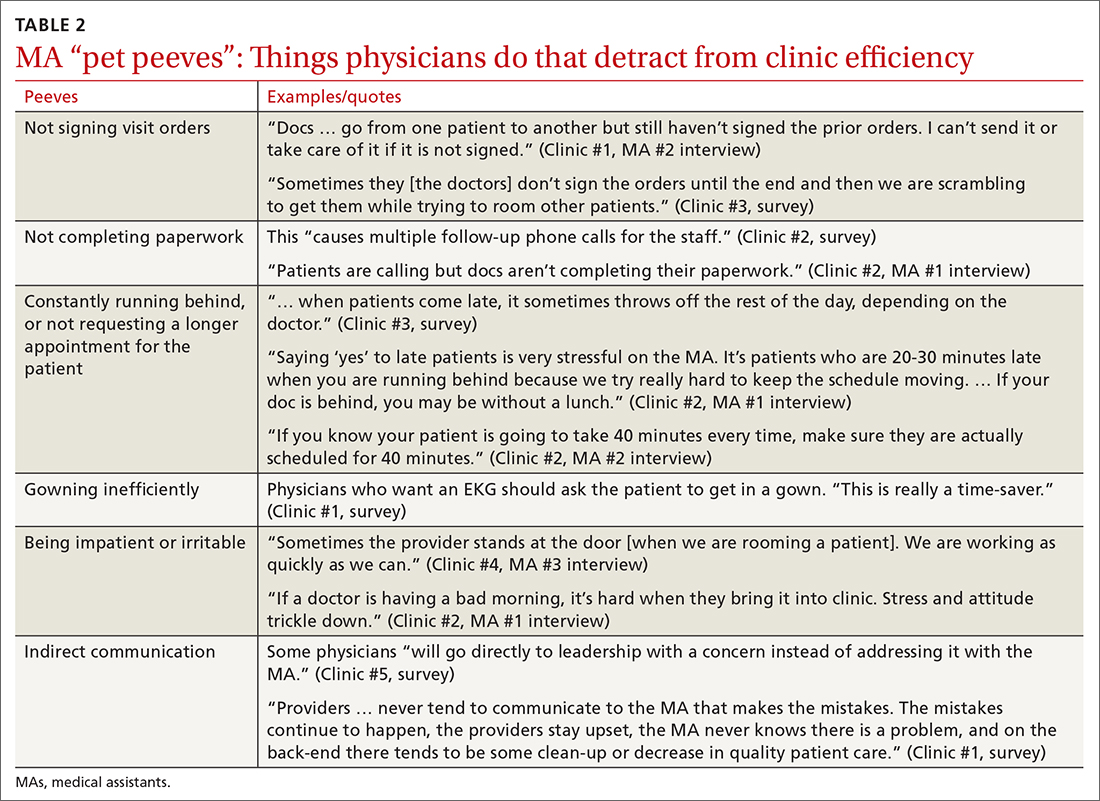

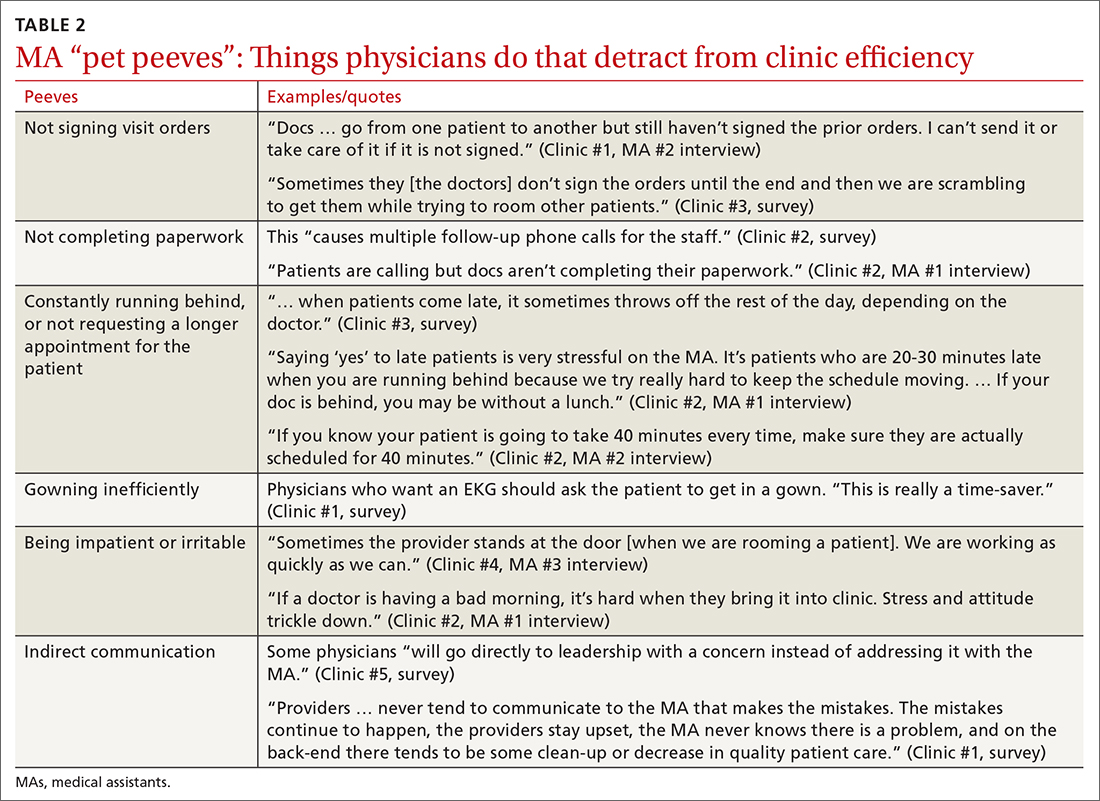

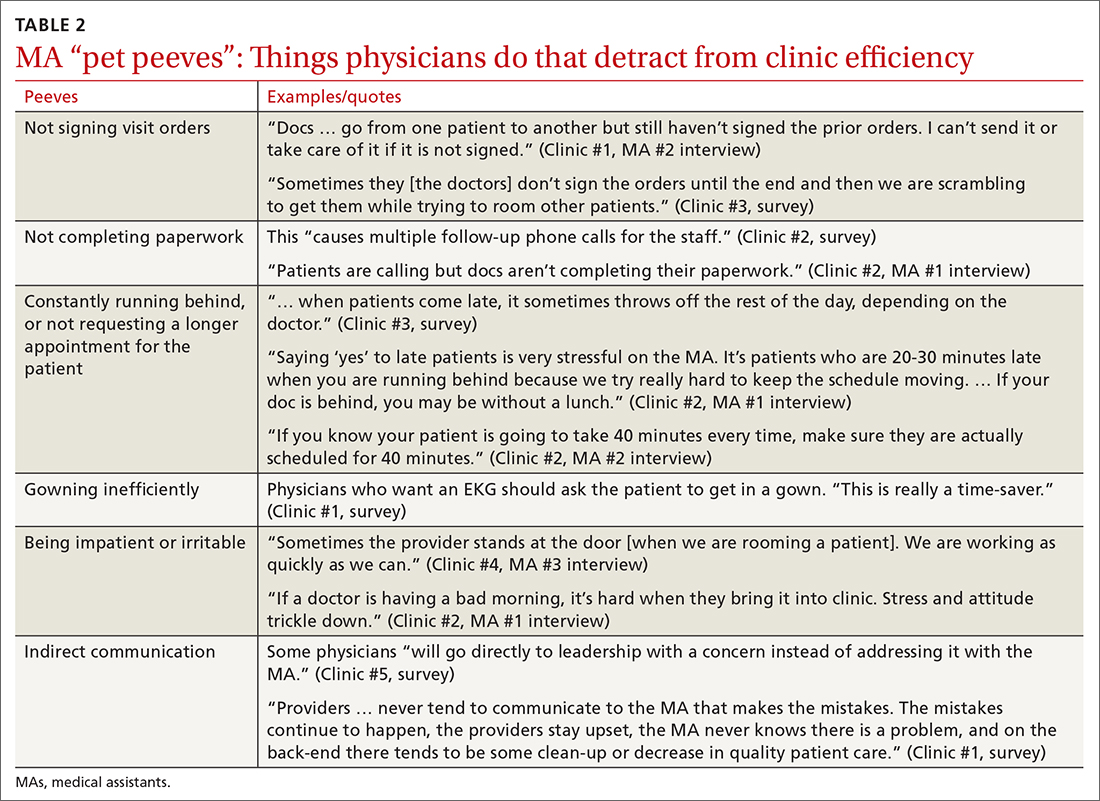

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“ Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“ [Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

Continue to: A minority of staff...

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Continue to: Almost all respondents...

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male-dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries.19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs.8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; [email protected]

1. Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

2. Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

3. Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/articles/medical-assisting-trends/

4. Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

5. Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medical-assisting-history/

6. Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

7. Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

8. Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

9. Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

10. STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_combined.pdf

11. Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

12. Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

13. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

14. Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

15. Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

16. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes319092.htm

17. Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

18. Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

19. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

20. Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

21. Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

22. Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11:187-201.

23. Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

24. O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

Continue to: We developed and piloted...

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Continue to: Efficiency and competing priorities

Efficiency and competing priorities

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“ Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“ [Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

Continue to: A minority of staff...

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Continue to: Almost all respondents...

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male-dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries.19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.