User login

Women in GI: Career-spanning strategies to overcome gender bias

The gender gap in gastroenterology persists – currently, women constitute 39% of fellows, but only 22% of senior AGA members and less than 18% of all practicing gastroenterologists – and it has gained even greater significance within the “current historical moment” of the COVID pandemic and growing cognizance of systemic sexism and racism, according to experts.

During the pandemic, women have been more likely to stay home to care for ill family members and children affected by school closures, which increases their already disproportionate share of unpaid work, wrote Jessica Bernica, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston with her associates in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. They noted that, according to one study, this “holds true for female physicians, who despite their more privileged positions, also experience higher demands at home, impacting their ability to contribute to teaching, service, and research.”

At the same time, the pandemic has brought into focus which jobs are “truly essential” – and that they are “overwhelmingly [held] by women and people of color, who are often underpaid and undervalued,” the experts wrote. The growing focus on systemic racism has also increased awareness of the chronic gender discrimination faced by female minorities, as well as by women in general, they added. In the field of gastroenterology, inherent gender bias – both systemic and self-directed – can bar women from advancing beginning as early as medical school.

To help address these issues, the experts outlined key opportunities for change as women navigate professional “forks in the road” throughout their careers.

Throughout their careers

During medical school and residency, women can specifically request gastroenterology rotations (“ideally with both inpatient and outpatient exposure”), attend society conferences, participate in research themselves, and join a research track or serve as chief medical resident. When applying for gastroenterology fellowships, they can prioritize programs with female faculty, which were recently found to be more likely to hire female fellows.

During fellowship, women can avail themselves of female mentors, who can help them strategize about ways to address gender bias, connect with GI groups and societies, and learn endoscopy techniques, including “unique approaches ... [that] overcome the challenges of standard scope sizes and accessibility.” At the institutional level, opportunities to affect positive changes for women trainees include “formal education on the benefits of hands-on learning and encouraging explicit and open communication between parties regarding invitation to, comfort with, and type of physical contact prior to a case.”

After fellowship, early-career gastroenterologists should scrutinize contracts for details on pay and research support, and they should ideally join a practice that either already has many women physicians on staff, or that ensures salary transparency and has “parental leave policies that are compatible with [applicants’] personal and professional goals.” But the experts advocated caution about part-time positions, which may purport to offer more flexibility but turn into full-time work for part-time pay and can preclude participation in practice management.

The experts recommended midcareer female gastroenterologists call out their own achievements rather than waiting for recognition, “actively seek promotion and tenure,” negotiate their salaries (as men tend to do routinely), and think twice before accepting professional roles that are uncompensated or do not clearly promote career advancement.

Senior gastroenterologists have unique opportunities to spearhead changes in institutional policies and practices, according to the experts. Specific examples include “explicitly stating [in job listings] that salary is negotiable, creating transparent written compensation plans, and conducting audits of job offers” to help mitigate any inequities in pay or hiring practices. In addition, senior women gastroenterologists can mentor individual women in the field, implement formal trainings on implicit bias, ensure that their practice or department tracks the gender of gastroenterologists who join, leave, or are promoted.

The experts did not report receiving funding for the work. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

Gastroenterology is a male-dominated field; women represent only 18% of current practicing gastroenterologists. Fortunately more women are entering medicine, including our field of gastroenterology, with current statistics showing that 39% of fellows are women. There have been historical barriers to women’s entry into the gastroenterology field, but thanks to the efforts of great female leaders in gastroenterology and men who are allies of women in our field, we have seen some of these barriers start to weaken. However, there is much work yet to be done. In fact, many would argue our work is just beginning.

Hopefully we will all learn something from Bernica and colleagues’ important piece and continue to sponsor and encourage women to practice this great field so that someday our workforce will look more like the patients we are caring for.

Laura E. Raffals, MD, is with the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. She has no conflicts of interest.

Gastroenterology is a male-dominated field; women represent only 18% of current practicing gastroenterologists. Fortunately more women are entering medicine, including our field of gastroenterology, with current statistics showing that 39% of fellows are women. There have been historical barriers to women’s entry into the gastroenterology field, but thanks to the efforts of great female leaders in gastroenterology and men who are allies of women in our field, we have seen some of these barriers start to weaken. However, there is much work yet to be done. In fact, many would argue our work is just beginning.

Hopefully we will all learn something from Bernica and colleagues’ important piece and continue to sponsor and encourage women to practice this great field so that someday our workforce will look more like the patients we are caring for.

Laura E. Raffals, MD, is with the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. She has no conflicts of interest.

Gastroenterology is a male-dominated field; women represent only 18% of current practicing gastroenterologists. Fortunately more women are entering medicine, including our field of gastroenterology, with current statistics showing that 39% of fellows are women. There have been historical barriers to women’s entry into the gastroenterology field, but thanks to the efforts of great female leaders in gastroenterology and men who are allies of women in our field, we have seen some of these barriers start to weaken. However, there is much work yet to be done. In fact, many would argue our work is just beginning.

Hopefully we will all learn something from Bernica and colleagues’ important piece and continue to sponsor and encourage women to practice this great field so that someday our workforce will look more like the patients we are caring for.

Laura E. Raffals, MD, is with the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. She has no conflicts of interest.

The gender gap in gastroenterology persists – currently, women constitute 39% of fellows, but only 22% of senior AGA members and less than 18% of all practicing gastroenterologists – and it has gained even greater significance within the “current historical moment” of the COVID pandemic and growing cognizance of systemic sexism and racism, according to experts.

During the pandemic, women have been more likely to stay home to care for ill family members and children affected by school closures, which increases their already disproportionate share of unpaid work, wrote Jessica Bernica, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston with her associates in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. They noted that, according to one study, this “holds true for female physicians, who despite their more privileged positions, also experience higher demands at home, impacting their ability to contribute to teaching, service, and research.”

At the same time, the pandemic has brought into focus which jobs are “truly essential” – and that they are “overwhelmingly [held] by women and people of color, who are often underpaid and undervalued,” the experts wrote. The growing focus on systemic racism has also increased awareness of the chronic gender discrimination faced by female minorities, as well as by women in general, they added. In the field of gastroenterology, inherent gender bias – both systemic and self-directed – can bar women from advancing beginning as early as medical school.

To help address these issues, the experts outlined key opportunities for change as women navigate professional “forks in the road” throughout their careers.

Throughout their careers

During medical school and residency, women can specifically request gastroenterology rotations (“ideally with both inpatient and outpatient exposure”), attend society conferences, participate in research themselves, and join a research track or serve as chief medical resident. When applying for gastroenterology fellowships, they can prioritize programs with female faculty, which were recently found to be more likely to hire female fellows.

During fellowship, women can avail themselves of female mentors, who can help them strategize about ways to address gender bias, connect with GI groups and societies, and learn endoscopy techniques, including “unique approaches ... [that] overcome the challenges of standard scope sizes and accessibility.” At the institutional level, opportunities to affect positive changes for women trainees include “formal education on the benefits of hands-on learning and encouraging explicit and open communication between parties regarding invitation to, comfort with, and type of physical contact prior to a case.”

After fellowship, early-career gastroenterologists should scrutinize contracts for details on pay and research support, and they should ideally join a practice that either already has many women physicians on staff, or that ensures salary transparency and has “parental leave policies that are compatible with [applicants’] personal and professional goals.” But the experts advocated caution about part-time positions, which may purport to offer more flexibility but turn into full-time work for part-time pay and can preclude participation in practice management.

The experts recommended midcareer female gastroenterologists call out their own achievements rather than waiting for recognition, “actively seek promotion and tenure,” negotiate their salaries (as men tend to do routinely), and think twice before accepting professional roles that are uncompensated or do not clearly promote career advancement.

Senior gastroenterologists have unique opportunities to spearhead changes in institutional policies and practices, according to the experts. Specific examples include “explicitly stating [in job listings] that salary is negotiable, creating transparent written compensation plans, and conducting audits of job offers” to help mitigate any inequities in pay or hiring practices. In addition, senior women gastroenterologists can mentor individual women in the field, implement formal trainings on implicit bias, ensure that their practice or department tracks the gender of gastroenterologists who join, leave, or are promoted.

The experts did not report receiving funding for the work. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

The gender gap in gastroenterology persists – currently, women constitute 39% of fellows, but only 22% of senior AGA members and less than 18% of all practicing gastroenterologists – and it has gained even greater significance within the “current historical moment” of the COVID pandemic and growing cognizance of systemic sexism and racism, according to experts.

During the pandemic, women have been more likely to stay home to care for ill family members and children affected by school closures, which increases their already disproportionate share of unpaid work, wrote Jessica Bernica, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston with her associates in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. They noted that, according to one study, this “holds true for female physicians, who despite their more privileged positions, also experience higher demands at home, impacting their ability to contribute to teaching, service, and research.”

At the same time, the pandemic has brought into focus which jobs are “truly essential” – and that they are “overwhelmingly [held] by women and people of color, who are often underpaid and undervalued,” the experts wrote. The growing focus on systemic racism has also increased awareness of the chronic gender discrimination faced by female minorities, as well as by women in general, they added. In the field of gastroenterology, inherent gender bias – both systemic and self-directed – can bar women from advancing beginning as early as medical school.

To help address these issues, the experts outlined key opportunities for change as women navigate professional “forks in the road” throughout their careers.

Throughout their careers

During medical school and residency, women can specifically request gastroenterology rotations (“ideally with both inpatient and outpatient exposure”), attend society conferences, participate in research themselves, and join a research track or serve as chief medical resident. When applying for gastroenterology fellowships, they can prioritize programs with female faculty, which were recently found to be more likely to hire female fellows.

During fellowship, women can avail themselves of female mentors, who can help them strategize about ways to address gender bias, connect with GI groups and societies, and learn endoscopy techniques, including “unique approaches ... [that] overcome the challenges of standard scope sizes and accessibility.” At the institutional level, opportunities to affect positive changes for women trainees include “formal education on the benefits of hands-on learning and encouraging explicit and open communication between parties regarding invitation to, comfort with, and type of physical contact prior to a case.”

After fellowship, early-career gastroenterologists should scrutinize contracts for details on pay and research support, and they should ideally join a practice that either already has many women physicians on staff, or that ensures salary transparency and has “parental leave policies that are compatible with [applicants’] personal and professional goals.” But the experts advocated caution about part-time positions, which may purport to offer more flexibility but turn into full-time work for part-time pay and can preclude participation in practice management.

The experts recommended midcareer female gastroenterologists call out their own achievements rather than waiting for recognition, “actively seek promotion and tenure,” negotiate their salaries (as men tend to do routinely), and think twice before accepting professional roles that are uncompensated or do not clearly promote career advancement.

Senior gastroenterologists have unique opportunities to spearhead changes in institutional policies and practices, according to the experts. Specific examples include “explicitly stating [in job listings] that salary is negotiable, creating transparent written compensation plans, and conducting audits of job offers” to help mitigate any inequities in pay or hiring practices. In addition, senior women gastroenterologists can mentor individual women in the field, implement formal trainings on implicit bias, ensure that their practice or department tracks the gender of gastroenterologists who join, leave, or are promoted.

The experts did not report receiving funding for the work. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM TECHNIQUES AND INNOVATIONS IN GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

In the previous year, 70% of oncologists reported sexual harassment

A new survey of sexual harassment among U.S. oncologists has found that 70% reported incidents from peers and/or supervisors in the previous 12 months.

The incidence was higher among women than men (80% vs. 56%), a difference that was statistically significant (P < .0001).

However, after experiencing sexual harassment from coworkers, men and women were alike in terms of reporting similarly negative outcomes in mental health, sense of safety, and turnover intentions (e.g., leaving or quitting).

“Our findings demonstrate that the impact of sexual harassment on both men and women is tangible and is not different,” said lead author Ishwaria Subbiah, MD, a medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, during her presentation of the study on June 5 at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2021. The meeting was held virtually because of the pandemic.

“The survey’s recall period [about harassment] was in the previous 12 months. The respondents weren’t reflecting on a lifetime of events,” Dr. Subbiah said in an interview. “That’s part of what makes the findings that much more sobering.”

The release of the survey results roughly coincided with a furor within oncology circles over details that have now come to light about Axel Grothey, MD, a high-profile medical oncologist who was forced out of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., after having unethical sexual relations with mentees – only to move on to another major center with more mentees.

The new survey, which included 153 women and 118 men, was conducted in 2020.

Overall, 69% of respondents reported gender-based harassment, 17% reported unwanted sexual attention, and 3% reported sexual coercion from peers/supervisors. For the three types of sexual harassment, women reported higher rates of incidence; the greatest proportional disparity was in unwanted sexual attention (22% of women vs. 9% of men).

The types of sexual harassment are defined in a landmark 2018 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Gender harassment is nonverbal or verbal behaviors that are hostile, objectifying, and excluding of or conveying second-class status about a gender. Unwanted sexual attention is advances, including touching, and seeking a sexual relationship despite discouragement. Sexual coercion involves seeking compliance with sexual demands by making job-related threats or promising job-related benefits.

The commonality in the three harassments is their being “unwanted,” Dr. Subbiah explained.

Another commonality is that “sexual harassment is a tool of power that one person yields over another,” commented Marina Stasenko, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

Dr. Stasenko led a 2018 study that found that 64% of U.S. gynecologic oncologists reported sexual harassment during training or practice, a much longer recall period than the 1 year in Dr. Subbiah’s study.

However, things may be changing regarding sexual harassment – at least in terms of victims speaking out, said Dr. Stasenko. Perhaps discussing personal experience “is becoming less taboo,” she told this news organization. “The media spotlight on sexual harassment within medicine has been bright [recently].”

That was borne out last week – a number of oncologists who had been harassed told their stories on Twitter in reaction to the report about Dr. Grothey at one of America’s top medical centers. Also, in another sign of the moment, an academic oncologist publicly said that rumors about Dr. Grothey were long-standing. “Heard from many colleagues that this behavior was known in the field and went on for years. Years,” tweeted Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Other outcomes seem to make Dr. Grothey’s behavior at Mayo, which multiple oncologists said has occurred at every center, a watershed moment. Namely, he has been muted or dismissed by an array of organizations since the story broke.

ASCO disallowed Dr. Grothey from making presentations at the annual meeting (he was an author on 12 studies), the National Cancer Institute removed him from his position as co-chair of an influential steering committee that helps determine grant funding for research, and the OneOncology community care network dropped him as medical director of their research arm, as reported by The Cancer Letter. He was also removed from the OncoAlert Network, a global network of oncology professionals, and from the medical advisory board of Fight CRC, an advocacy group for patients with colorectal cancer, as reported by this news organization. His current employer, West Cancer Center, in Germantown, Tennessee, has also started an investigation.

In her presentation, Dr. Subbiah acknowledged a changing landscape, with “increasing attention in recent years” to sexual harassment thanks to the “broader cultural movements” of #metoo and #TIMESUP social media–based campaigns.

Another oncologist nodded to the recent news about Dr. Grothey at the Mayo Clinic and suggested Dr. Subbiah’s study was part of a historic struggle for equity for women. “Sadly, both timely and timeless,” tweeted medical oncologist Tatiana Prowell, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, about the new study.

Academia has a problem

To conduct their survey, Dr. Subbiah and her coinvestigators reached out to 1,000 randomly selected U.S. members of ASCO via the organization’s research survey pool, as well as through Twitter and Facebook. The invitation to participate described the survey as being about the “workplace experience of oncologists” and that it aimed to mitigate response bias.

Of the 271 survey respondents, 250 were oncologists in practice and 21 were residents/fellows. Nearly all were heterosexual (94%) and U.S. citizens (87%). A majority (53%) were White, 35% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 11% were Black or Hispanic. Most (68%) were more than 5 years out from training.

Most of the respondents (62%) were from academia.

“There is a big problem of sexual harassment in academic medicine,” said Pamela Kunz, MD, of Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., who was asked for comment. Dr. Kunz left Stanford University in 2020 after 19 years, citing repeated harassment.

“The institutions tend to protect the brand rather than the victim. Perpetrators are often not disciplined and may leave an institution under cover of a resignation only to go on and receive a better leadership role at another institution,” she said in an interview.

A “revolution” is needed to address the problem, Dr. Kunz said, citing needs to routinely discuss the topic, systems to measure and track it, methods to hold perpetrators accountable, and meaningful educational opportunities.

Harassment from patients/families also tallied

The new survey also queried participants with regard to sexual harassment from patients and/or families, which was reported by 67% of women and 35% of men (P < .0001).

As with harassment from peers/supervisors, gender harassment was the most common form and was reported by significantly higher percentages of women.

And as with coworkers, sexual harassment from patients/families was also significantly associated with detriments to mental health, workplace safety, and turnover intentions.

Sexual harassment from “insiders” (P = .001) but not patients (P = .55) was significantly associated with a decrease in a fourth metric in the study – job satisfaction.

“The goal of medicine and oncology is ‘ultimately to ease suffering,’” Dr. Subbiah said. That holds true for workplace wellness, including addressing harassment. “There should be no hesitation to go there and look at what is truly impacting the workplace,” she said.

“This is a difficult topic,” Dr. Subbiah acknowledged, adding that “the findings are sobering and merit open, global conversation among all oncology stakeholders.”

The study authors, Dr. Ganz, and Dr. Stasenko have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey of sexual harassment among U.S. oncologists has found that 70% reported incidents from peers and/or supervisors in the previous 12 months.

The incidence was higher among women than men (80% vs. 56%), a difference that was statistically significant (P < .0001).

However, after experiencing sexual harassment from coworkers, men and women were alike in terms of reporting similarly negative outcomes in mental health, sense of safety, and turnover intentions (e.g., leaving or quitting).

“Our findings demonstrate that the impact of sexual harassment on both men and women is tangible and is not different,” said lead author Ishwaria Subbiah, MD, a medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, during her presentation of the study on June 5 at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2021. The meeting was held virtually because of the pandemic.

“The survey’s recall period [about harassment] was in the previous 12 months. The respondents weren’t reflecting on a lifetime of events,” Dr. Subbiah said in an interview. “That’s part of what makes the findings that much more sobering.”

The release of the survey results roughly coincided with a furor within oncology circles over details that have now come to light about Axel Grothey, MD, a high-profile medical oncologist who was forced out of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., after having unethical sexual relations with mentees – only to move on to another major center with more mentees.

The new survey, which included 153 women and 118 men, was conducted in 2020.

Overall, 69% of respondents reported gender-based harassment, 17% reported unwanted sexual attention, and 3% reported sexual coercion from peers/supervisors. For the three types of sexual harassment, women reported higher rates of incidence; the greatest proportional disparity was in unwanted sexual attention (22% of women vs. 9% of men).

The types of sexual harassment are defined in a landmark 2018 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Gender harassment is nonverbal or verbal behaviors that are hostile, objectifying, and excluding of or conveying second-class status about a gender. Unwanted sexual attention is advances, including touching, and seeking a sexual relationship despite discouragement. Sexual coercion involves seeking compliance with sexual demands by making job-related threats or promising job-related benefits.

The commonality in the three harassments is their being “unwanted,” Dr. Subbiah explained.

Another commonality is that “sexual harassment is a tool of power that one person yields over another,” commented Marina Stasenko, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

Dr. Stasenko led a 2018 study that found that 64% of U.S. gynecologic oncologists reported sexual harassment during training or practice, a much longer recall period than the 1 year in Dr. Subbiah’s study.

However, things may be changing regarding sexual harassment – at least in terms of victims speaking out, said Dr. Stasenko. Perhaps discussing personal experience “is becoming less taboo,” she told this news organization. “The media spotlight on sexual harassment within medicine has been bright [recently].”

That was borne out last week – a number of oncologists who had been harassed told their stories on Twitter in reaction to the report about Dr. Grothey at one of America’s top medical centers. Also, in another sign of the moment, an academic oncologist publicly said that rumors about Dr. Grothey were long-standing. “Heard from many colleagues that this behavior was known in the field and went on for years. Years,” tweeted Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Other outcomes seem to make Dr. Grothey’s behavior at Mayo, which multiple oncologists said has occurred at every center, a watershed moment. Namely, he has been muted or dismissed by an array of organizations since the story broke.

ASCO disallowed Dr. Grothey from making presentations at the annual meeting (he was an author on 12 studies), the National Cancer Institute removed him from his position as co-chair of an influential steering committee that helps determine grant funding for research, and the OneOncology community care network dropped him as medical director of their research arm, as reported by The Cancer Letter. He was also removed from the OncoAlert Network, a global network of oncology professionals, and from the medical advisory board of Fight CRC, an advocacy group for patients with colorectal cancer, as reported by this news organization. His current employer, West Cancer Center, in Germantown, Tennessee, has also started an investigation.

In her presentation, Dr. Subbiah acknowledged a changing landscape, with “increasing attention in recent years” to sexual harassment thanks to the “broader cultural movements” of #metoo and #TIMESUP social media–based campaigns.

Another oncologist nodded to the recent news about Dr. Grothey at the Mayo Clinic and suggested Dr. Subbiah’s study was part of a historic struggle for equity for women. “Sadly, both timely and timeless,” tweeted medical oncologist Tatiana Prowell, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, about the new study.

Academia has a problem

To conduct their survey, Dr. Subbiah and her coinvestigators reached out to 1,000 randomly selected U.S. members of ASCO via the organization’s research survey pool, as well as through Twitter and Facebook. The invitation to participate described the survey as being about the “workplace experience of oncologists” and that it aimed to mitigate response bias.

Of the 271 survey respondents, 250 were oncologists in practice and 21 were residents/fellows. Nearly all were heterosexual (94%) and U.S. citizens (87%). A majority (53%) were White, 35% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 11% were Black or Hispanic. Most (68%) were more than 5 years out from training.

Most of the respondents (62%) were from academia.

“There is a big problem of sexual harassment in academic medicine,” said Pamela Kunz, MD, of Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., who was asked for comment. Dr. Kunz left Stanford University in 2020 after 19 years, citing repeated harassment.

“The institutions tend to protect the brand rather than the victim. Perpetrators are often not disciplined and may leave an institution under cover of a resignation only to go on and receive a better leadership role at another institution,” she said in an interview.

A “revolution” is needed to address the problem, Dr. Kunz said, citing needs to routinely discuss the topic, systems to measure and track it, methods to hold perpetrators accountable, and meaningful educational opportunities.

Harassment from patients/families also tallied

The new survey also queried participants with regard to sexual harassment from patients and/or families, which was reported by 67% of women and 35% of men (P < .0001).

As with harassment from peers/supervisors, gender harassment was the most common form and was reported by significantly higher percentages of women.

And as with coworkers, sexual harassment from patients/families was also significantly associated with detriments to mental health, workplace safety, and turnover intentions.

Sexual harassment from “insiders” (P = .001) but not patients (P = .55) was significantly associated with a decrease in a fourth metric in the study – job satisfaction.

“The goal of medicine and oncology is ‘ultimately to ease suffering,’” Dr. Subbiah said. That holds true for workplace wellness, including addressing harassment. “There should be no hesitation to go there and look at what is truly impacting the workplace,” she said.

“This is a difficult topic,” Dr. Subbiah acknowledged, adding that “the findings are sobering and merit open, global conversation among all oncology stakeholders.”

The study authors, Dr. Ganz, and Dr. Stasenko have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey of sexual harassment among U.S. oncologists has found that 70% reported incidents from peers and/or supervisors in the previous 12 months.

The incidence was higher among women than men (80% vs. 56%), a difference that was statistically significant (P < .0001).

However, after experiencing sexual harassment from coworkers, men and women were alike in terms of reporting similarly negative outcomes in mental health, sense of safety, and turnover intentions (e.g., leaving or quitting).

“Our findings demonstrate that the impact of sexual harassment on both men and women is tangible and is not different,” said lead author Ishwaria Subbiah, MD, a medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, during her presentation of the study on June 5 at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2021. The meeting was held virtually because of the pandemic.

“The survey’s recall period [about harassment] was in the previous 12 months. The respondents weren’t reflecting on a lifetime of events,” Dr. Subbiah said in an interview. “That’s part of what makes the findings that much more sobering.”

The release of the survey results roughly coincided with a furor within oncology circles over details that have now come to light about Axel Grothey, MD, a high-profile medical oncologist who was forced out of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., after having unethical sexual relations with mentees – only to move on to another major center with more mentees.

The new survey, which included 153 women and 118 men, was conducted in 2020.

Overall, 69% of respondents reported gender-based harassment, 17% reported unwanted sexual attention, and 3% reported sexual coercion from peers/supervisors. For the three types of sexual harassment, women reported higher rates of incidence; the greatest proportional disparity was in unwanted sexual attention (22% of women vs. 9% of men).

The types of sexual harassment are defined in a landmark 2018 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Gender harassment is nonverbal or verbal behaviors that are hostile, objectifying, and excluding of or conveying second-class status about a gender. Unwanted sexual attention is advances, including touching, and seeking a sexual relationship despite discouragement. Sexual coercion involves seeking compliance with sexual demands by making job-related threats or promising job-related benefits.

The commonality in the three harassments is their being “unwanted,” Dr. Subbiah explained.

Another commonality is that “sexual harassment is a tool of power that one person yields over another,” commented Marina Stasenko, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center.

Dr. Stasenko led a 2018 study that found that 64% of U.S. gynecologic oncologists reported sexual harassment during training or practice, a much longer recall period than the 1 year in Dr. Subbiah’s study.

However, things may be changing regarding sexual harassment – at least in terms of victims speaking out, said Dr. Stasenko. Perhaps discussing personal experience “is becoming less taboo,” she told this news organization. “The media spotlight on sexual harassment within medicine has been bright [recently].”

That was borne out last week – a number of oncologists who had been harassed told their stories on Twitter in reaction to the report about Dr. Grothey at one of America’s top medical centers. Also, in another sign of the moment, an academic oncologist publicly said that rumors about Dr. Grothey were long-standing. “Heard from many colleagues that this behavior was known in the field and went on for years. Years,” tweeted Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Other outcomes seem to make Dr. Grothey’s behavior at Mayo, which multiple oncologists said has occurred at every center, a watershed moment. Namely, he has been muted or dismissed by an array of organizations since the story broke.

ASCO disallowed Dr. Grothey from making presentations at the annual meeting (he was an author on 12 studies), the National Cancer Institute removed him from his position as co-chair of an influential steering committee that helps determine grant funding for research, and the OneOncology community care network dropped him as medical director of their research arm, as reported by The Cancer Letter. He was also removed from the OncoAlert Network, a global network of oncology professionals, and from the medical advisory board of Fight CRC, an advocacy group for patients with colorectal cancer, as reported by this news organization. His current employer, West Cancer Center, in Germantown, Tennessee, has also started an investigation.

In her presentation, Dr. Subbiah acknowledged a changing landscape, with “increasing attention in recent years” to sexual harassment thanks to the “broader cultural movements” of #metoo and #TIMESUP social media–based campaigns.

Another oncologist nodded to the recent news about Dr. Grothey at the Mayo Clinic and suggested Dr. Subbiah’s study was part of a historic struggle for equity for women. “Sadly, both timely and timeless,” tweeted medical oncologist Tatiana Prowell, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, about the new study.

Academia has a problem

To conduct their survey, Dr. Subbiah and her coinvestigators reached out to 1,000 randomly selected U.S. members of ASCO via the organization’s research survey pool, as well as through Twitter and Facebook. The invitation to participate described the survey as being about the “workplace experience of oncologists” and that it aimed to mitigate response bias.

Of the 271 survey respondents, 250 were oncologists in practice and 21 were residents/fellows. Nearly all were heterosexual (94%) and U.S. citizens (87%). A majority (53%) were White, 35% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 11% were Black or Hispanic. Most (68%) were more than 5 years out from training.

Most of the respondents (62%) were from academia.

“There is a big problem of sexual harassment in academic medicine,” said Pamela Kunz, MD, of Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., who was asked for comment. Dr. Kunz left Stanford University in 2020 after 19 years, citing repeated harassment.

“The institutions tend to protect the brand rather than the victim. Perpetrators are often not disciplined and may leave an institution under cover of a resignation only to go on and receive a better leadership role at another institution,” she said in an interview.

A “revolution” is needed to address the problem, Dr. Kunz said, citing needs to routinely discuss the topic, systems to measure and track it, methods to hold perpetrators accountable, and meaningful educational opportunities.

Harassment from patients/families also tallied

The new survey also queried participants with regard to sexual harassment from patients and/or families, which was reported by 67% of women and 35% of men (P < .0001).

As with harassment from peers/supervisors, gender harassment was the most common form and was reported by significantly higher percentages of women.

And as with coworkers, sexual harassment from patients/families was also significantly associated with detriments to mental health, workplace safety, and turnover intentions.

Sexual harassment from “insiders” (P = .001) but not patients (P = .55) was significantly associated with a decrease in a fourth metric in the study – job satisfaction.

“The goal of medicine and oncology is ‘ultimately to ease suffering,’” Dr. Subbiah said. That holds true for workplace wellness, including addressing harassment. “There should be no hesitation to go there and look at what is truly impacting the workplace,” she said.

“This is a difficult topic,” Dr. Subbiah acknowledged, adding that “the findings are sobering and merit open, global conversation among all oncology stakeholders.”

The study authors, Dr. Ganz, and Dr. Stasenko have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Under new administration, best time to lobby for health care may be now

The ambitious infrastructure bill now being debated in the US Congress might be one of the best immediate opportunities to lobby for legislative or policy changes in delivery of health care during the current Biden administration, according to an analysis delivered at the annual health policy and advocacy conference sponsored by the American College of Chest Physicians.

The infrastructure bill is likely to be pushed forward in the filibuster-proof reconciliation process, which means “that some things might get passed that otherwise would not,” explained Keith S. Studdard, Vice President, Jeffrey J. Kimbell & Associates, Washington, DC.

With few exceptions, the key players in the health care team of President Joe Biden’s new administration are in place, according to Mr. Studdard, who is a lobbyist and health care expert. By moving quickly to fill key positions, the new administration “got off to a good start” for a health care agenda that Mr. Studdard believes will be a focus of the Biden presidency. There is some degree of urgency.

“The amount of time [the Biden administration has] to get their agenda through is fairly limited,” Mr. Studdard reported. The problems include a slim majority of fellow Democrats in the House of Representatives (222 vs 213), no majority of Democrats over Republicans in the Senate (50 vs 50), and mid-term elections that are already looming.

“Midterms historically favor the opposition party,” Mr. Studdard said. He expects party lines to harden as the midterms approach, dissipating the already limited appetite for bipartisan cooperation.

The midterms provide the basis for trying to affect change in advance of legislative gridlock, but the recently announced $2 trillion infrastructure bill is an even more compelling impetus. Infrastructure in this case is not limited to the construction of bridges and roads. Rather, this bill “is a massive package that will almost certainly touch on health care policy,” according to Mr. Studdard.

As the infrastructure bill winds its way through the legislative process, Mr. Studdard expects there will be efforts to include language that favors expansion of services and funding for health care. This includes those related to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the temporary modifications permitted under the CARES Act, which was passed during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For those who think that waivers and exceptions introduced in the CARES Act, such as the expansion of telehealth, should be made permanent, “this will be your main shot on goal,” Mr. Studdard said.

The debates around the ambitious infrastructure bill are “all that we will be hearing about from the legislative standpoint for the next few months,” Mr. Studdard said. He expects major lobbying efforts in regard to this legislation from a vast array of interest groups, not just those with a stake in health care.

If the bill passes, it will likely to be greatly helped by a vote under the reconciliation process. Created in 1974 to allow expedited consideration of spending legislation, the reconciliation process allows bills to be enacted with a simple majority, which is 51 votes in the Senate and 218 votes in the House. Filibustering is not permitted.

This means that the infrastructure bill, like the CARES Act, which was also passed through the reconciliation process, can be made into law even if all 50 Republican senators vote against it. As she has already done three times since taking office—most recently for COVID19 relief bill in early March—Vice President Kamala Harris can break a 50-50 tie with her vote for the administration’s agenda.

Legislation is one of two paths for altering funding and rules regarding health care in the United States. Policy is the other. For reaching decision makers with influence on policy, Mr. Studdard provided a long list of agencies, political appointees, and elected representatives that could be targeted. Many, such as the director of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), are well known, but others might be overlooked without a detailed list of the players.

As one example, he pointed to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which is a relatively new organization within CMS. Led by Liz Fowler, a former Senate aide involved in writing the ACA, the CMMI has broad authority over several aspects of health policy, such as value-based care.

“The CCMI is something you should put on your radar. It moves with more flexibility than the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services],” Mr. Studdard said.

Mr. Studdard’s detailed overview of the intricacies of how to affect change in health policy and the likely trajectory under the Biden Administration included frequent comments about the traits, background, and goals of the specific decision makers he identified. The implication is that personal relations matter. Mr. Studdard indicated that knowing who to contact is just the first step.

For the Health Policy and Advocacy Committee, this information is critical. In his outline of the numerous paths for influencing health care policy, Mr. Studdard’s comments lead directly to strategies to lobbying goals for CHEST.

“CHEST and its Health Policy and Advocacy Committee are keeping a focus on health care policy to improve access and to improve care for our patients and reduce the burden on our providers,” according to the Chair of the Committee, Neil Freedman, MD, FCCP. Dr, Freedman is the Division Head Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy, and Immunology, Northshore University HeatlhSystem, Evanston, Illinois.

“We would hope that, in addition to the proposed infrastructure bill subsidizing some additional costs for the ACA and COBRA [Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act] and enhancing Medicaid eligibility, the bill would also provide some additional funding for the provider relief fund,” he said.

Mr. Studdard or his lobbying firm represent 62 clients with interests in health care policy.

The ambitious infrastructure bill now being debated in the US Congress might be one of the best immediate opportunities to lobby for legislative or policy changes in delivery of health care during the current Biden administration, according to an analysis delivered at the annual health policy and advocacy conference sponsored by the American College of Chest Physicians.

The infrastructure bill is likely to be pushed forward in the filibuster-proof reconciliation process, which means “that some things might get passed that otherwise would not,” explained Keith S. Studdard, Vice President, Jeffrey J. Kimbell & Associates, Washington, DC.

With few exceptions, the key players in the health care team of President Joe Biden’s new administration are in place, according to Mr. Studdard, who is a lobbyist and health care expert. By moving quickly to fill key positions, the new administration “got off to a good start” for a health care agenda that Mr. Studdard believes will be a focus of the Biden presidency. There is some degree of urgency.

“The amount of time [the Biden administration has] to get their agenda through is fairly limited,” Mr. Studdard reported. The problems include a slim majority of fellow Democrats in the House of Representatives (222 vs 213), no majority of Democrats over Republicans in the Senate (50 vs 50), and mid-term elections that are already looming.

“Midterms historically favor the opposition party,” Mr. Studdard said. He expects party lines to harden as the midterms approach, dissipating the already limited appetite for bipartisan cooperation.

The midterms provide the basis for trying to affect change in advance of legislative gridlock, but the recently announced $2 trillion infrastructure bill is an even more compelling impetus. Infrastructure in this case is not limited to the construction of bridges and roads. Rather, this bill “is a massive package that will almost certainly touch on health care policy,” according to Mr. Studdard.

As the infrastructure bill winds its way through the legislative process, Mr. Studdard expects there will be efforts to include language that favors expansion of services and funding for health care. This includes those related to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the temporary modifications permitted under the CARES Act, which was passed during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For those who think that waivers and exceptions introduced in the CARES Act, such as the expansion of telehealth, should be made permanent, “this will be your main shot on goal,” Mr. Studdard said.

The debates around the ambitious infrastructure bill are “all that we will be hearing about from the legislative standpoint for the next few months,” Mr. Studdard said. He expects major lobbying efforts in regard to this legislation from a vast array of interest groups, not just those with a stake in health care.

If the bill passes, it will likely to be greatly helped by a vote under the reconciliation process. Created in 1974 to allow expedited consideration of spending legislation, the reconciliation process allows bills to be enacted with a simple majority, which is 51 votes in the Senate and 218 votes in the House. Filibustering is not permitted.

This means that the infrastructure bill, like the CARES Act, which was also passed through the reconciliation process, can be made into law even if all 50 Republican senators vote against it. As she has already done three times since taking office—most recently for COVID19 relief bill in early March—Vice President Kamala Harris can break a 50-50 tie with her vote for the administration’s agenda.

Legislation is one of two paths for altering funding and rules regarding health care in the United States. Policy is the other. For reaching decision makers with influence on policy, Mr. Studdard provided a long list of agencies, political appointees, and elected representatives that could be targeted. Many, such as the director of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), are well known, but others might be overlooked without a detailed list of the players.

As one example, he pointed to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which is a relatively new organization within CMS. Led by Liz Fowler, a former Senate aide involved in writing the ACA, the CMMI has broad authority over several aspects of health policy, such as value-based care.

“The CCMI is something you should put on your radar. It moves with more flexibility than the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services],” Mr. Studdard said.

Mr. Studdard’s detailed overview of the intricacies of how to affect change in health policy and the likely trajectory under the Biden Administration included frequent comments about the traits, background, and goals of the specific decision makers he identified. The implication is that personal relations matter. Mr. Studdard indicated that knowing who to contact is just the first step.

For the Health Policy and Advocacy Committee, this information is critical. In his outline of the numerous paths for influencing health care policy, Mr. Studdard’s comments lead directly to strategies to lobbying goals for CHEST.

“CHEST and its Health Policy and Advocacy Committee are keeping a focus on health care policy to improve access and to improve care for our patients and reduce the burden on our providers,” according to the Chair of the Committee, Neil Freedman, MD, FCCP. Dr, Freedman is the Division Head Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy, and Immunology, Northshore University HeatlhSystem, Evanston, Illinois.

“We would hope that, in addition to the proposed infrastructure bill subsidizing some additional costs for the ACA and COBRA [Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act] and enhancing Medicaid eligibility, the bill would also provide some additional funding for the provider relief fund,” he said.

Mr. Studdard or his lobbying firm represent 62 clients with interests in health care policy.

The ambitious infrastructure bill now being debated in the US Congress might be one of the best immediate opportunities to lobby for legislative or policy changes in delivery of health care during the current Biden administration, according to an analysis delivered at the annual health policy and advocacy conference sponsored by the American College of Chest Physicians.

The infrastructure bill is likely to be pushed forward in the filibuster-proof reconciliation process, which means “that some things might get passed that otherwise would not,” explained Keith S. Studdard, Vice President, Jeffrey J. Kimbell & Associates, Washington, DC.

With few exceptions, the key players in the health care team of President Joe Biden’s new administration are in place, according to Mr. Studdard, who is a lobbyist and health care expert. By moving quickly to fill key positions, the new administration “got off to a good start” for a health care agenda that Mr. Studdard believes will be a focus of the Biden presidency. There is some degree of urgency.

“The amount of time [the Biden administration has] to get their agenda through is fairly limited,” Mr. Studdard reported. The problems include a slim majority of fellow Democrats in the House of Representatives (222 vs 213), no majority of Democrats over Republicans in the Senate (50 vs 50), and mid-term elections that are already looming.

“Midterms historically favor the opposition party,” Mr. Studdard said. He expects party lines to harden as the midterms approach, dissipating the already limited appetite for bipartisan cooperation.

The midterms provide the basis for trying to affect change in advance of legislative gridlock, but the recently announced $2 trillion infrastructure bill is an even more compelling impetus. Infrastructure in this case is not limited to the construction of bridges and roads. Rather, this bill “is a massive package that will almost certainly touch on health care policy,” according to Mr. Studdard.

As the infrastructure bill winds its way through the legislative process, Mr. Studdard expects there will be efforts to include language that favors expansion of services and funding for health care. This includes those related to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the temporary modifications permitted under the CARES Act, which was passed during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For those who think that waivers and exceptions introduced in the CARES Act, such as the expansion of telehealth, should be made permanent, “this will be your main shot on goal,” Mr. Studdard said.

The debates around the ambitious infrastructure bill are “all that we will be hearing about from the legislative standpoint for the next few months,” Mr. Studdard said. He expects major lobbying efforts in regard to this legislation from a vast array of interest groups, not just those with a stake in health care.

If the bill passes, it will likely to be greatly helped by a vote under the reconciliation process. Created in 1974 to allow expedited consideration of spending legislation, the reconciliation process allows bills to be enacted with a simple majority, which is 51 votes in the Senate and 218 votes in the House. Filibustering is not permitted.

This means that the infrastructure bill, like the CARES Act, which was also passed through the reconciliation process, can be made into law even if all 50 Republican senators vote against it. As she has already done three times since taking office—most recently for COVID19 relief bill in early March—Vice President Kamala Harris can break a 50-50 tie with her vote for the administration’s agenda.

Legislation is one of two paths for altering funding and rules regarding health care in the United States. Policy is the other. For reaching decision makers with influence on policy, Mr. Studdard provided a long list of agencies, political appointees, and elected representatives that could be targeted. Many, such as the director of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), are well known, but others might be overlooked without a detailed list of the players.

As one example, he pointed to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which is a relatively new organization within CMS. Led by Liz Fowler, a former Senate aide involved in writing the ACA, the CMMI has broad authority over several aspects of health policy, such as value-based care.

“The CCMI is something you should put on your radar. It moves with more flexibility than the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services],” Mr. Studdard said.

Mr. Studdard’s detailed overview of the intricacies of how to affect change in health policy and the likely trajectory under the Biden Administration included frequent comments about the traits, background, and goals of the specific decision makers he identified. The implication is that personal relations matter. Mr. Studdard indicated that knowing who to contact is just the first step.

For the Health Policy and Advocacy Committee, this information is critical. In his outline of the numerous paths for influencing health care policy, Mr. Studdard’s comments lead directly to strategies to lobbying goals for CHEST.

“CHEST and its Health Policy and Advocacy Committee are keeping a focus on health care policy to improve access and to improve care for our patients and reduce the burden on our providers,” according to the Chair of the Committee, Neil Freedman, MD, FCCP. Dr, Freedman is the Division Head Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy, and Immunology, Northshore University HeatlhSystem, Evanston, Illinois.

“We would hope that, in addition to the proposed infrastructure bill subsidizing some additional costs for the ACA and COBRA [Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act] and enhancing Medicaid eligibility, the bill would also provide some additional funding for the provider relief fund,” he said.

Mr. Studdard or his lobbying firm represent 62 clients with interests in health care policy.

REPORTING FROM THE CHEST HEALTH POLICY AND ADVOCACY CONFERENCE

E/M Coding in 2021: The Times (and More) Are A-Changin’

Effective on January 1, 2021, the outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes underwent substantial changes, which were the culmination of multiple years of revision and surveying via the American Medical Association (AMA) Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Current Procedural Terminology (RUC-CPT) process to streamline definitions and promote consistency as well as to decrease the administrative burden for all specialties within the house of medicine.1 These updates represent a notable change from the previous documentation requirements for this oft used family of codes. Herein, we break down some of the highlights of the changes and how they may be applied for some commonly used dermatologic diagnoses.

Time Is Time Is Time

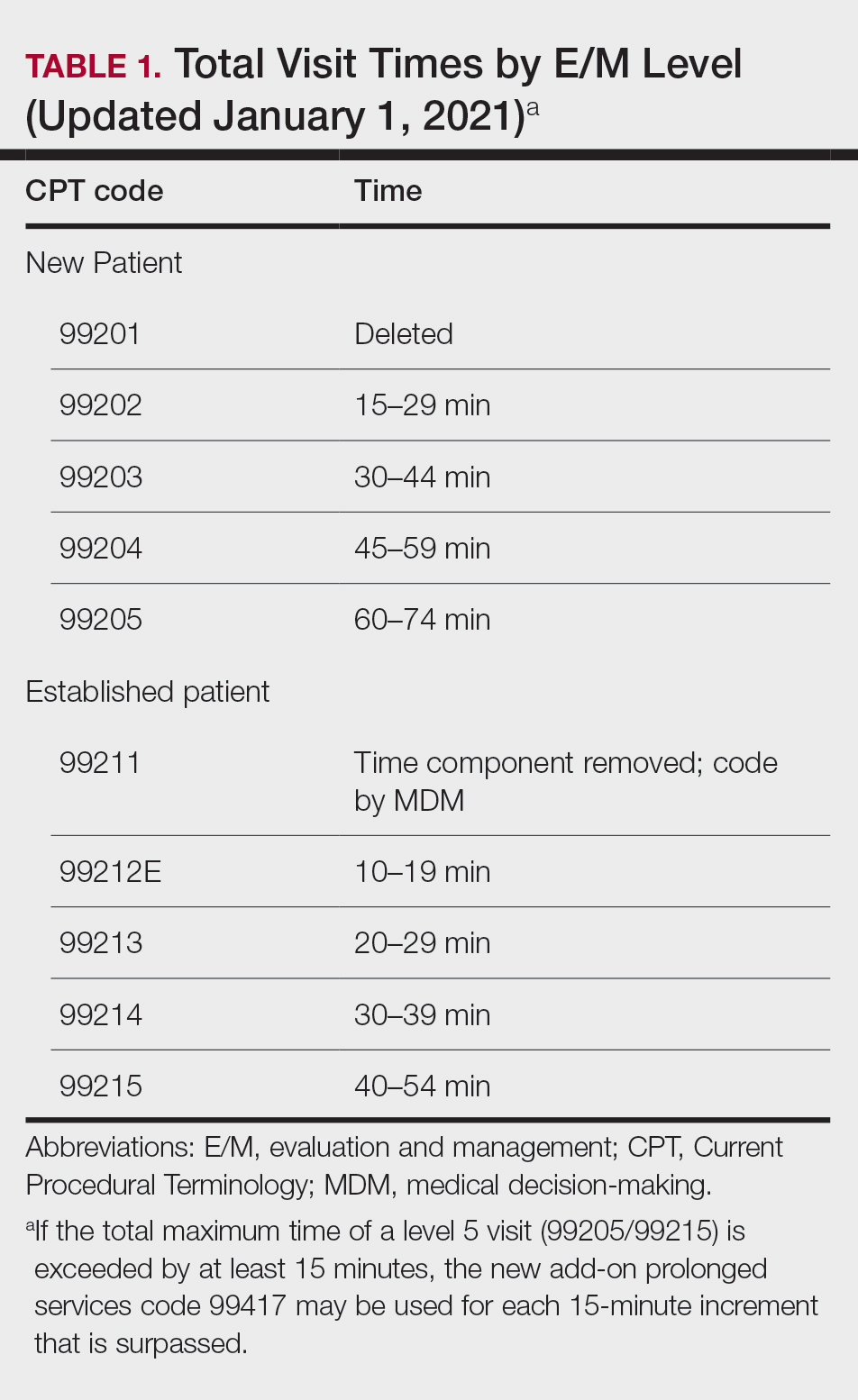

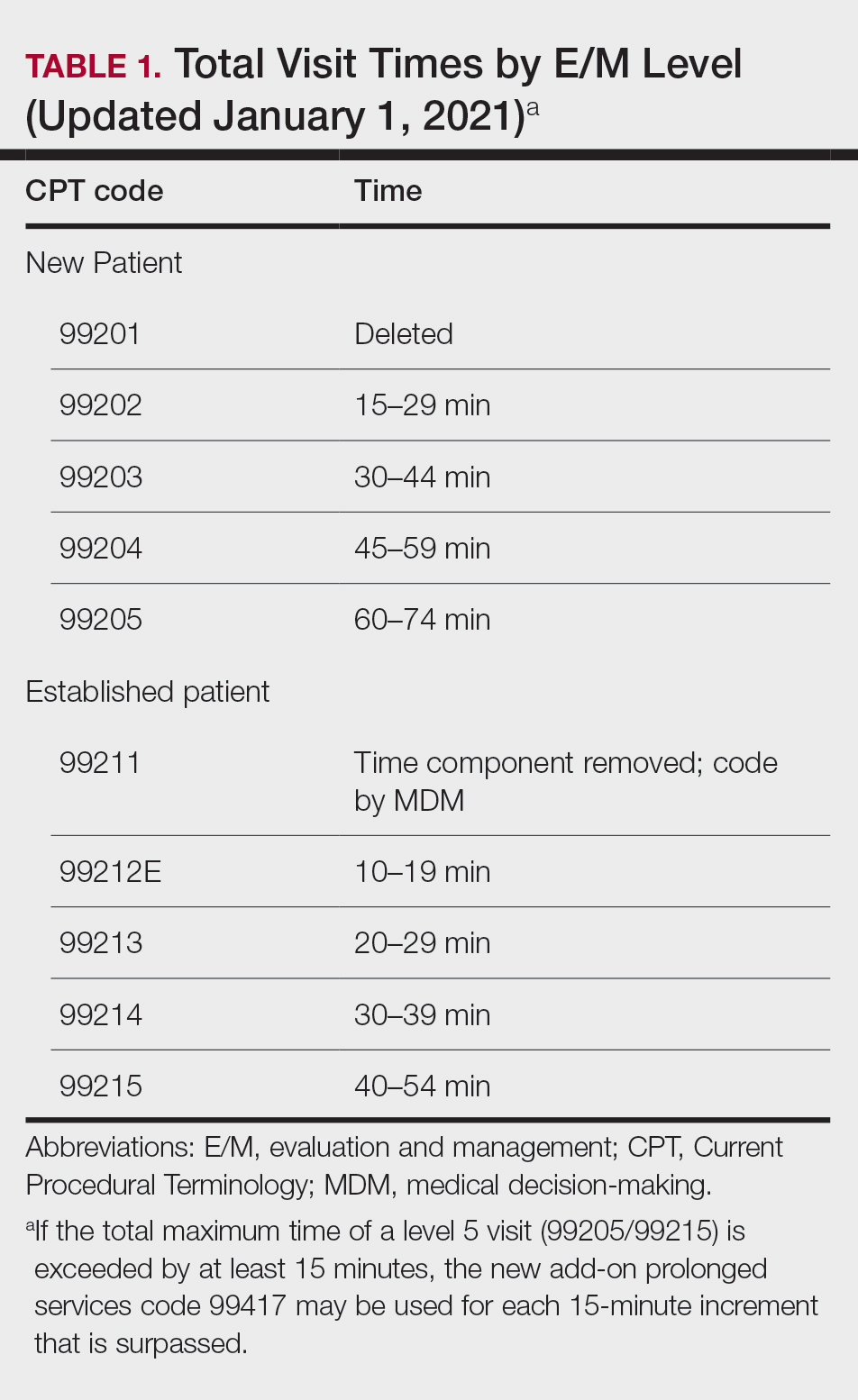

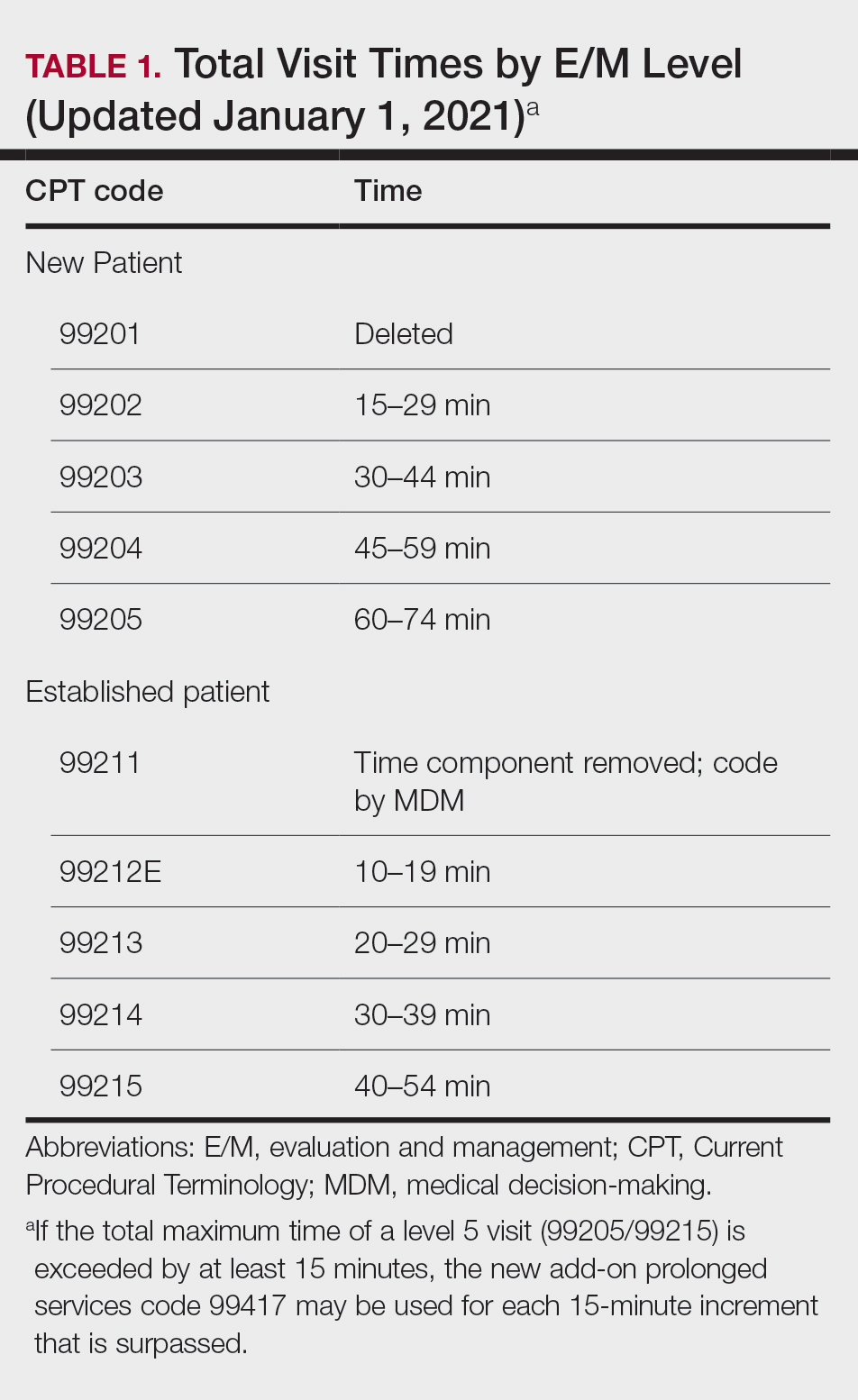

Prior to the 2021 revisions, a physician generally could only code for an E/M level by time for a face-to-face encounter dominated by counseling and/or care coordination. With the new updates, any encounter can be coded by total time spent by the physician with the patient1; however, clinical staff time is not included. There also are now clear guidelines of the time ranges corresponding to the level of E/M,1 as noted in Table 1.

Importantly, time now includes not just face-to-face time with the patient but also any time on the date of the encounter that the physician is involved in the care of the patient when not reported with a separate code. This can include reviewing notes or data before or after the examination, care coordination, ordering laboratory tests, and providing any documentation related to the encounter. Importantly, this applies only when these activities are done on the date of the encounter.

If you work with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (PA) who assists you and you are the one reporting the service, you cannot double-dip. For example, if your PA spends 10 minutes alone with a patient, you are in the room together for 5 minutes, the PA spends another 10 minutes alone with the patient afterward, and you do chart work for 10 minutes at the end of the day, the total time spent is 35 minutes, not 40 minutes, as you cannot count the time you and the PA spent together twice.

Decisions, Decisions

Evaluation and management coding also can be determined via the level of medical decision-making (MDM). Per the 2021 guidelines, MDM is comprised of 3 categories: (1) number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter, (2) amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed or analyzed, and (3) risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.1 To reach a certain overall E/M level, 2 of 3 categories must be met or exceeded. Let’s dive into each of these in a little more detail.

Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed at the Encounter

First, it is important to understand the definition of a problem addressed. Per AMA guidelines, this includes a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter that is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician. If the problem is referred to another provider without evaluation or consideration of treatment, it is not considered to be a problem addressed and cannot count toward this first category. An example could be a patient with a lump on the abdomen that you refer to plastic or general surgery for evaluation and treatment.

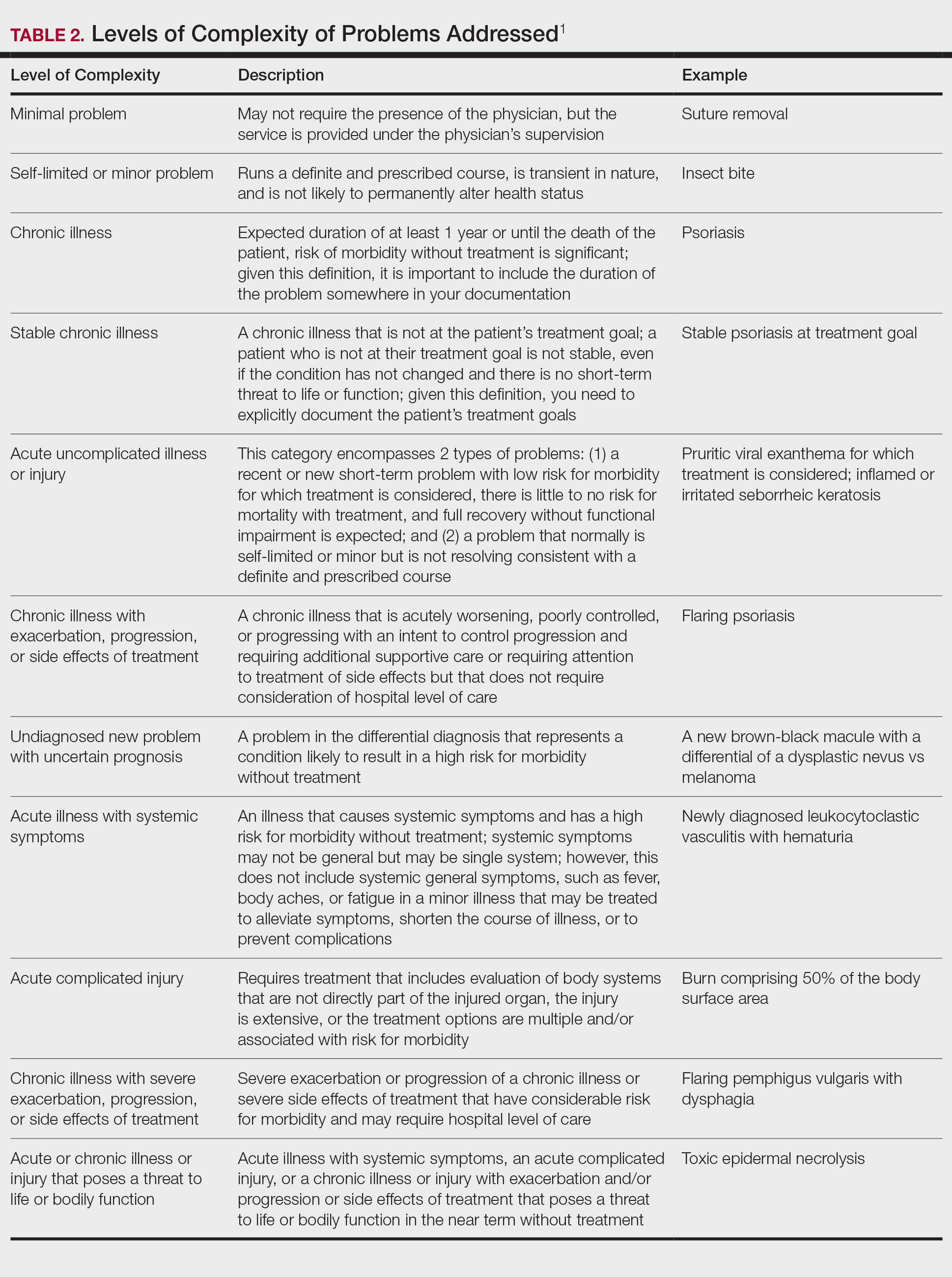

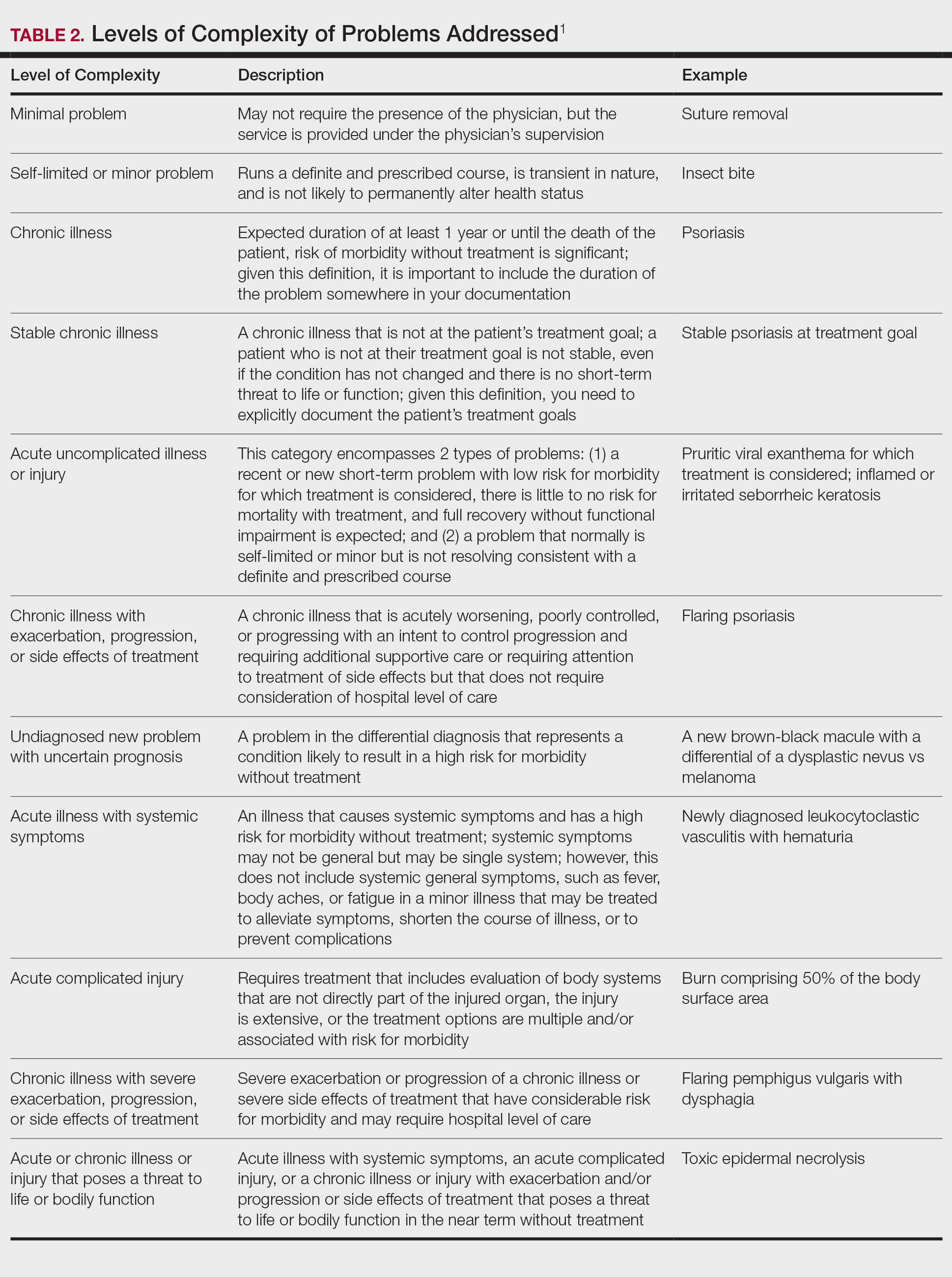

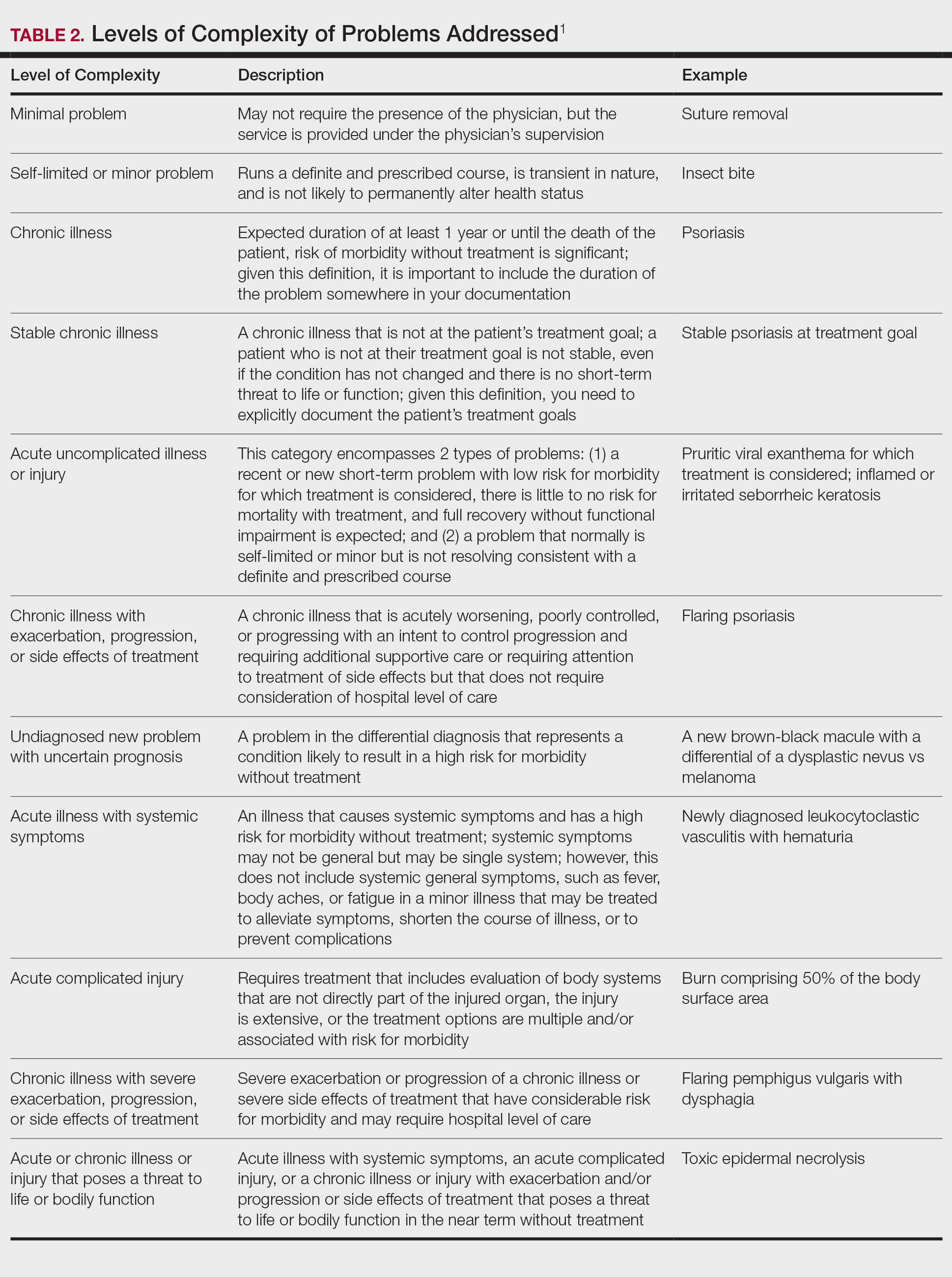

Once you have determined that you are addressing a problem, you will need to determine the level of complexity of the problem, as outlined in Table 2. Keep in mind that some entities and disease states in dermatology may fit the requirements of more than 1 level of complexity depending on the clinical situation, while there are many entities in dermatology that may not be perfectly captured by any of the levels described. In these situations, clinical judgement is required to determine where the problem would best fit. Importantly, whatever you decide, your documentation should support that decision.

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Be Reviewed and Analyzed

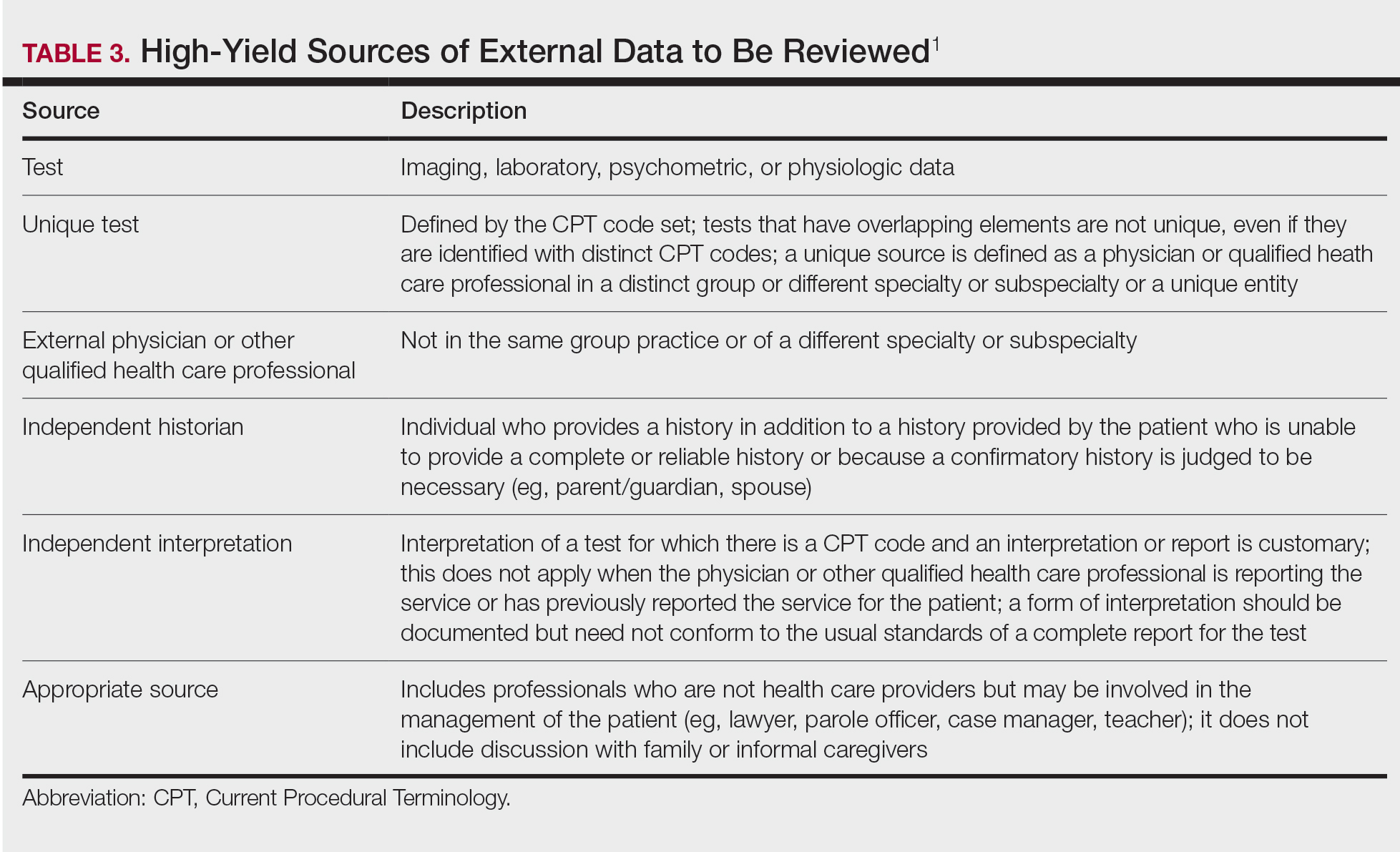

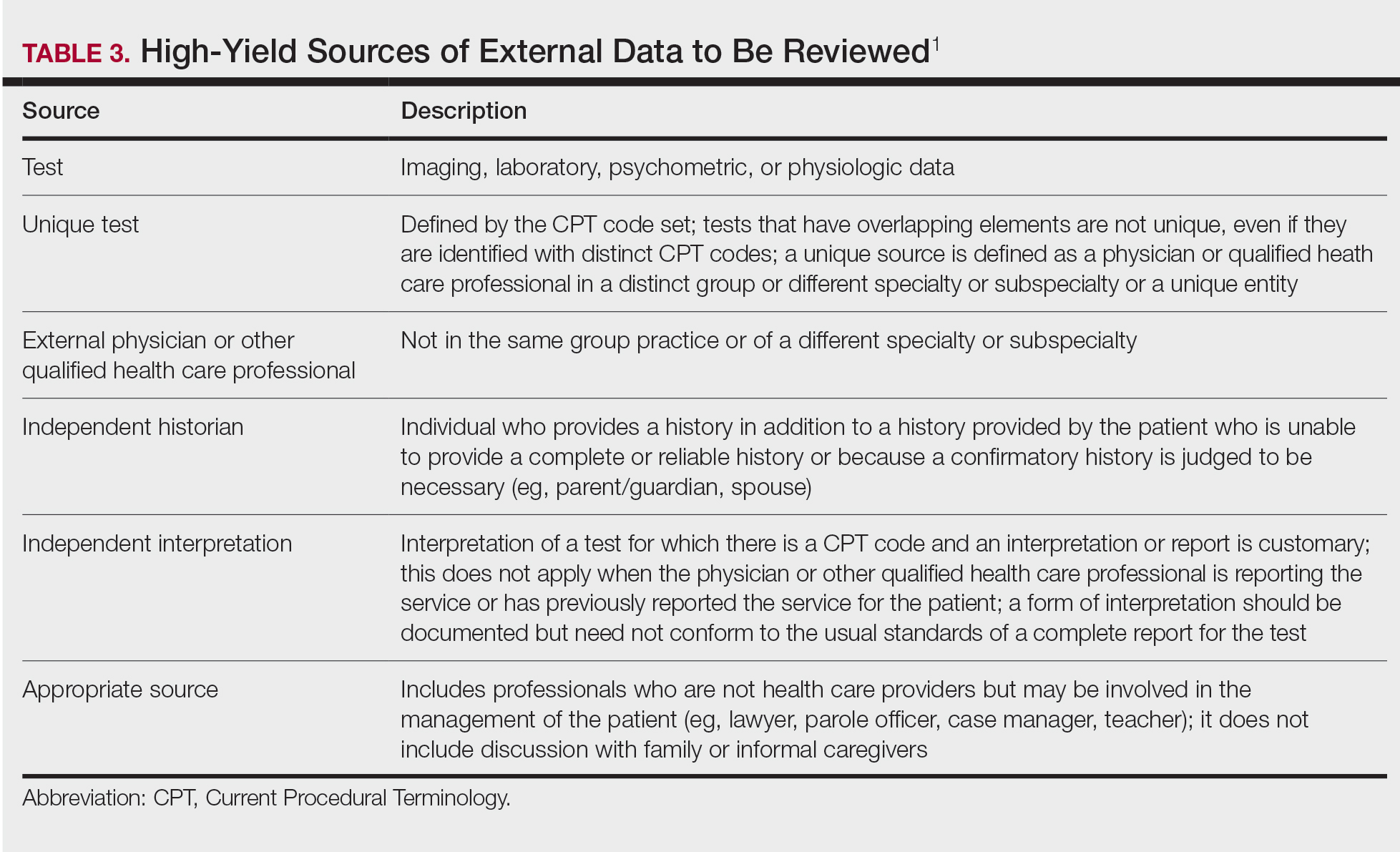

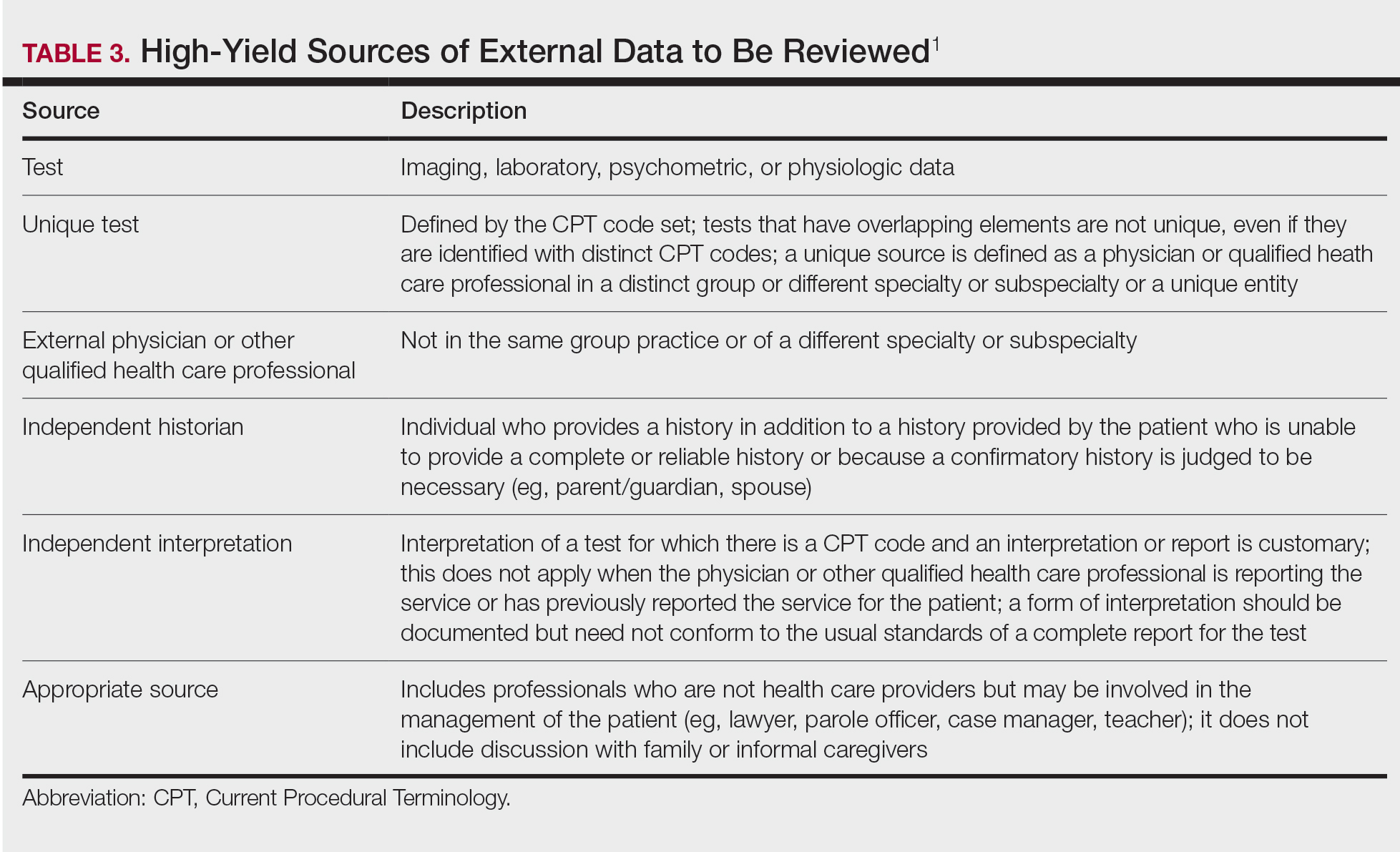

This category encompasses any external notes reviewed, unique laboratory tests or imaging ordered or reviewed, the need for an independent historian or discussion with external health care providers or appropriate sources, or independent interpretation of tests. Some high-yield definitions in this category are outlined in Table 3.

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

In this category, risk relates to both the patient’s diagnosis and treatment(s). Importantly, for treatment and diagnostic options, these include both the options selected and those considered but not selected. Risk is defined as the probability and/or consequences of an event and is based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician in the same specialty. In other words, think of the risk as compared to risk in the setting of other dermatologists diagnosing and/or treating the same condition.

Social determinants of health also play a part in this category and are defined as economic and social conditions that influence the health of individuals and communities. Social determinants of health can be indicated by the specific corresponding International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code and may need to be included in your billing according to specific institutional or carrier guidelines if they are a factor in your level of MDM.

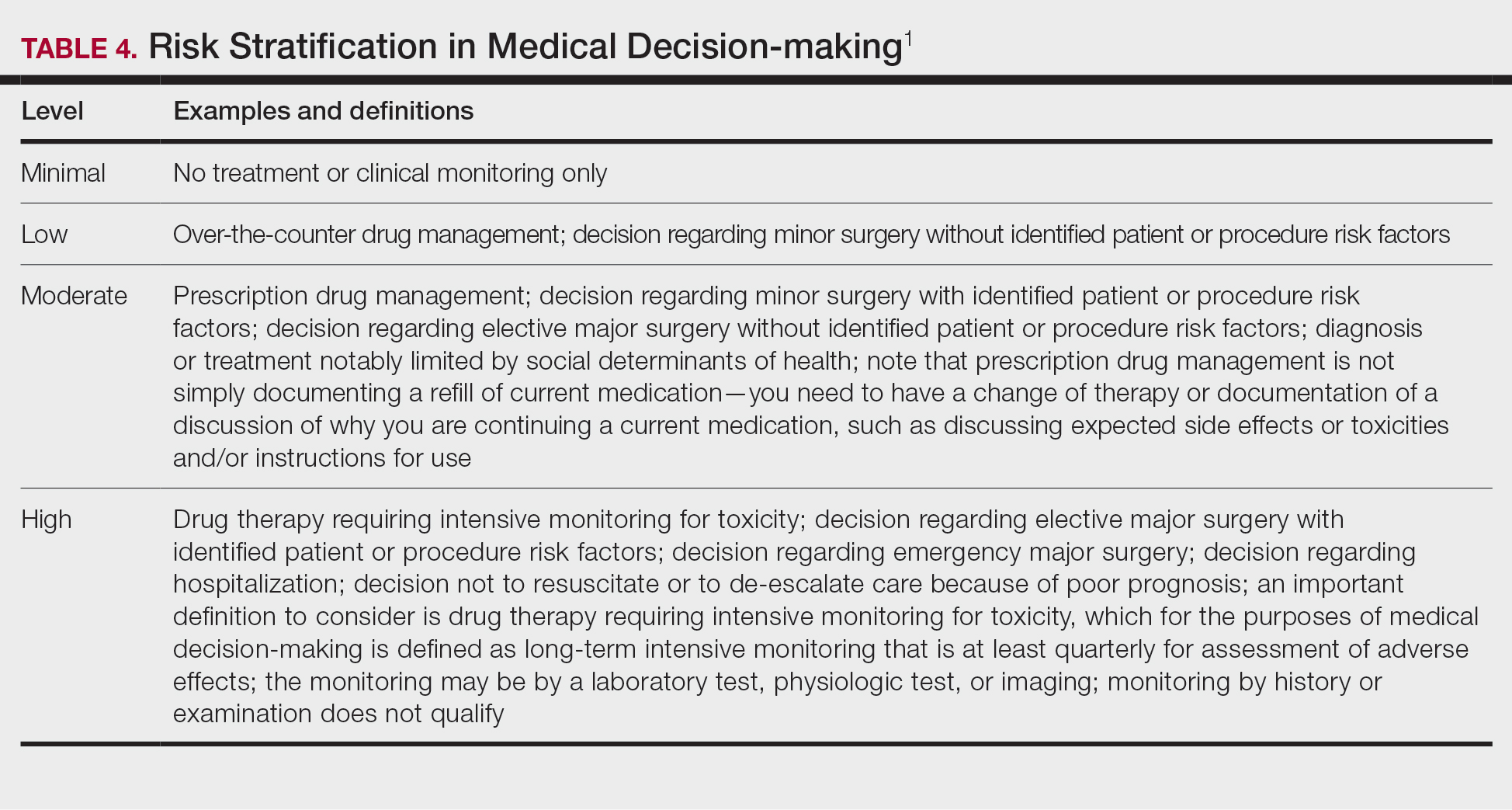

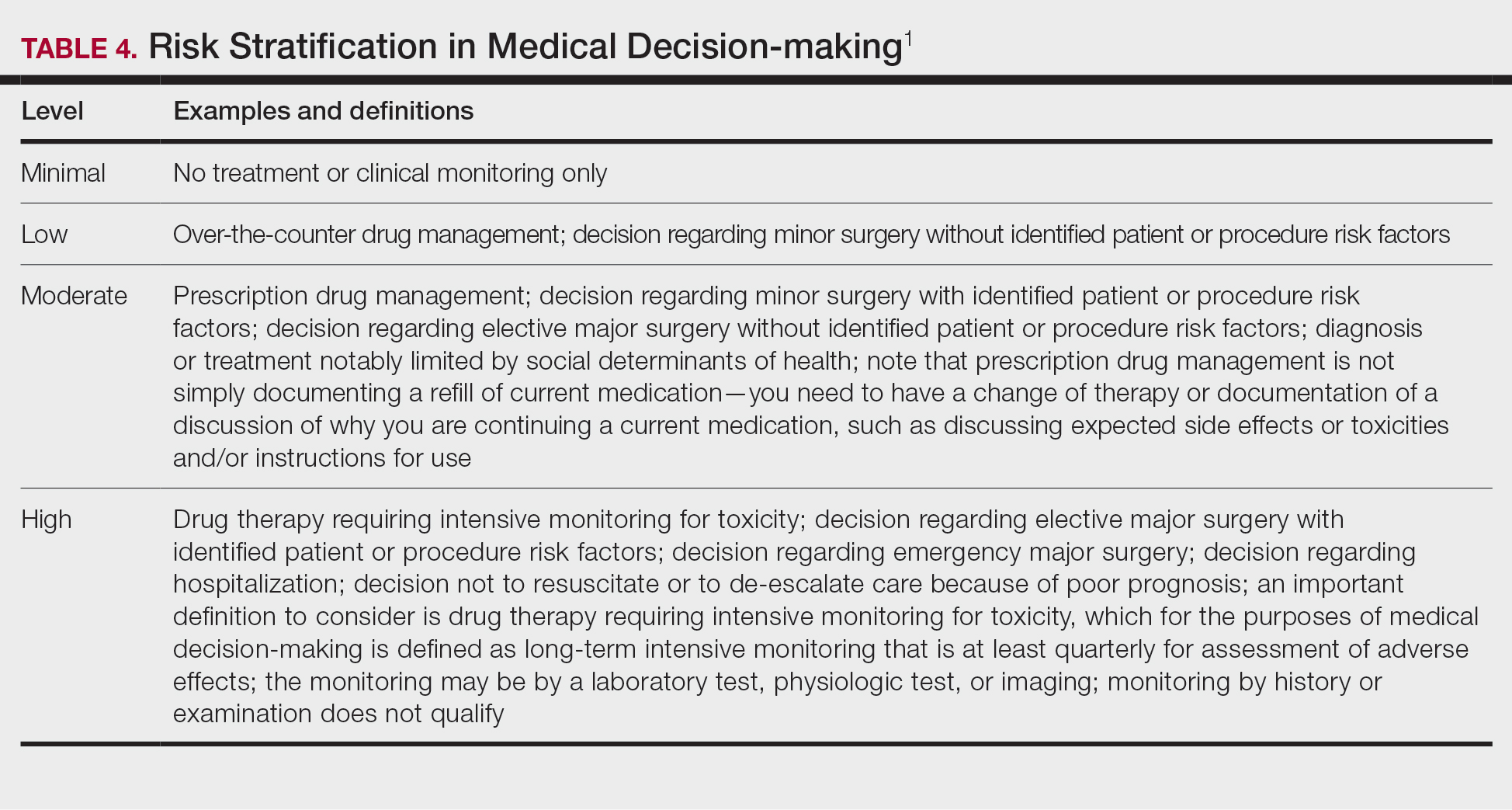

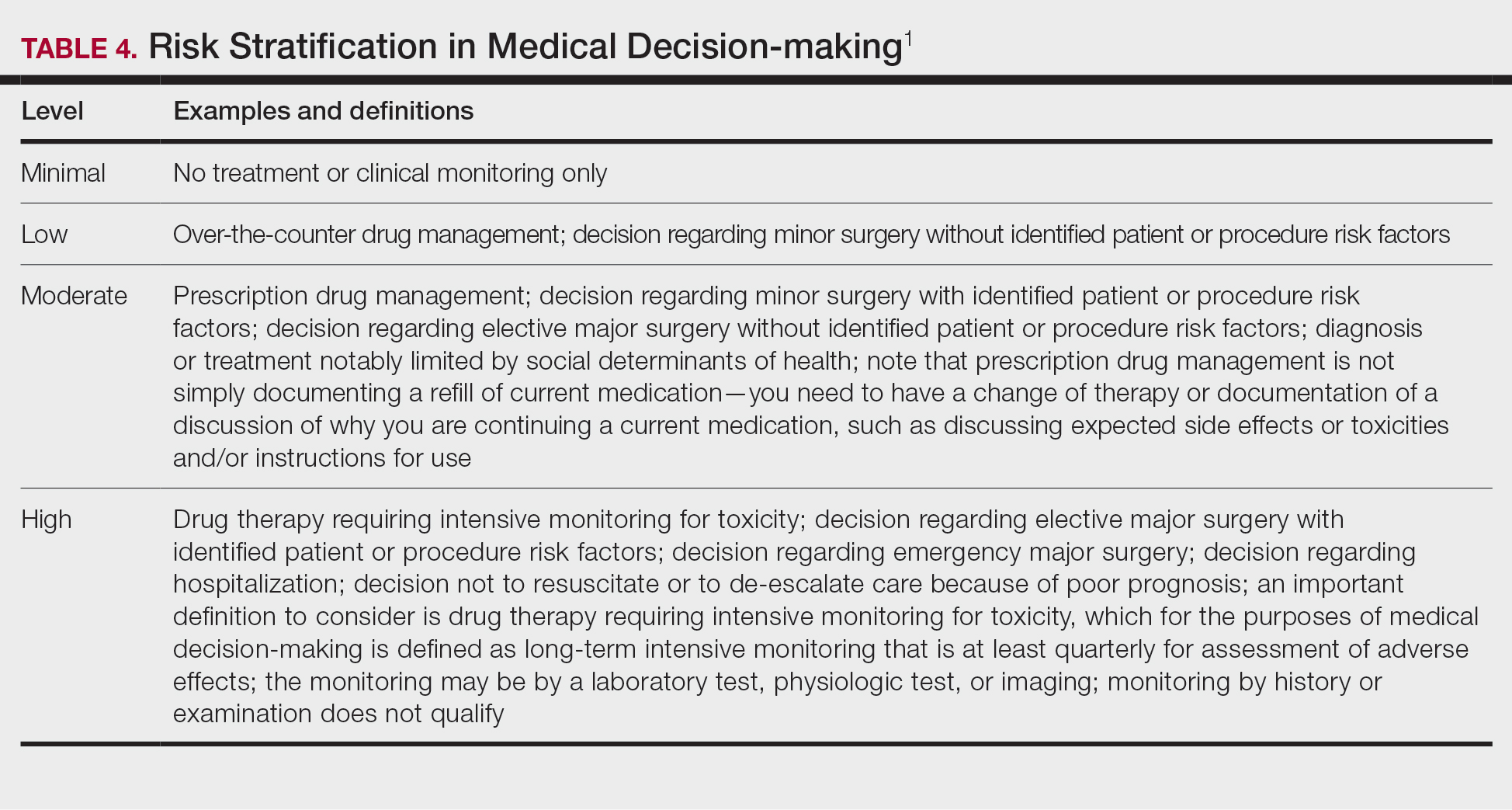

For the purposes of MDM, risk is stratified into minimal, low, moderate, and high. Some examples for each level are outlined in Table 4.

Putting It All Together

Once you have determined each of the above 3 categories, you can put them together into the MDM chart to ascertain the overall level of MDM. (The official AMA medical decision-making grid is available online [https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf]). Keep in mind that 2 of 3 columns in the table must be obtained in that level to reach an overall E/M level; for example, a visit that addresses 2 self-limited or minor problems (level 3) in which no data is reviewed (level 2) and involves prescribing a new medication (level 4), would be an overall level 3 visit.

Final Thoughts

The outpatient E/M guidelines have undergone substantial revisions; therefore, it is crucial to understand the updated definitions to ensure proper billing and documentation. History and physical examination documentation must be medically appropriate but are no longer used to determine overall E/M level; time and MDM are the sole options that can be used. Importantly, try to code as accurately as possible, documenting which problems were both noted and addressed. If you are unsure of a definition within the updated changes and MDM table, referencing the appropriate sources for guidance is recommended.

Although representing a considerable shift, the revaluation of this family of codes and the intended decrease in documentation burden has the ability to be a positive gain for dermatologists. Expect other code families to mirror these changes in the next few years.

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M) office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

Effective on January 1, 2021, the outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes underwent substantial changes, which were the culmination of multiple years of revision and surveying via the American Medical Association (AMA) Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Current Procedural Terminology (RUC-CPT) process to streamline definitions and promote consistency as well as to decrease the administrative burden for all specialties within the house of medicine.1 These updates represent a notable change from the previous documentation requirements for this oft used family of codes. Herein, we break down some of the highlights of the changes and how they may be applied for some commonly used dermatologic diagnoses.

Time Is Time Is Time

Prior to the 2021 revisions, a physician generally could only code for an E/M level by time for a face-to-face encounter dominated by counseling and/or care coordination. With the new updates, any encounter can be coded by total time spent by the physician with the patient1; however, clinical staff time is not included. There also are now clear guidelines of the time ranges corresponding to the level of E/M,1 as noted in Table 1.

Importantly, time now includes not just face-to-face time with the patient but also any time on the date of the encounter that the physician is involved in the care of the patient when not reported with a separate code. This can include reviewing notes or data before or after the examination, care coordination, ordering laboratory tests, and providing any documentation related to the encounter. Importantly, this applies only when these activities are done on the date of the encounter.

If you work with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (PA) who assists you and you are the one reporting the service, you cannot double-dip. For example, if your PA spends 10 minutes alone with a patient, you are in the room together for 5 minutes, the PA spends another 10 minutes alone with the patient afterward, and you do chart work for 10 minutes at the end of the day, the total time spent is 35 minutes, not 40 minutes, as you cannot count the time you and the PA spent together twice.

Decisions, Decisions

Evaluation and management coding also can be determined via the level of medical decision-making (MDM). Per the 2021 guidelines, MDM is comprised of 3 categories: (1) number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter, (2) amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed or analyzed, and (3) risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.1 To reach a certain overall E/M level, 2 of 3 categories must be met or exceeded. Let’s dive into each of these in a little more detail.

Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed at the Encounter

First, it is important to understand the definition of a problem addressed. Per AMA guidelines, this includes a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter that is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician. If the problem is referred to another provider without evaluation or consideration of treatment, it is not considered to be a problem addressed and cannot count toward this first category. An example could be a patient with a lump on the abdomen that you refer to plastic or general surgery for evaluation and treatment.

Once you have determined that you are addressing a problem, you will need to determine the level of complexity of the problem, as outlined in Table 2. Keep in mind that some entities and disease states in dermatology may fit the requirements of more than 1 level of complexity depending on the clinical situation, while there are many entities in dermatology that may not be perfectly captured by any of the levels described. In these situations, clinical judgement is required to determine where the problem would best fit. Importantly, whatever you decide, your documentation should support that decision.

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Be Reviewed and Analyzed

This category encompasses any external notes reviewed, unique laboratory tests or imaging ordered or reviewed, the need for an independent historian or discussion with external health care providers or appropriate sources, or independent interpretation of tests. Some high-yield definitions in this category are outlined in Table 3.

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

In this category, risk relates to both the patient’s diagnosis and treatment(s). Importantly, for treatment and diagnostic options, these include both the options selected and those considered but not selected. Risk is defined as the probability and/or consequences of an event and is based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician in the same specialty. In other words, think of the risk as compared to risk in the setting of other dermatologists diagnosing and/or treating the same condition.

Social determinants of health also play a part in this category and are defined as economic and social conditions that influence the health of individuals and communities. Social determinants of health can be indicated by the specific corresponding International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code and may need to be included in your billing according to specific institutional or carrier guidelines if they are a factor in your level of MDM.

For the purposes of MDM, risk is stratified into minimal, low, moderate, and high. Some examples for each level are outlined in Table 4.

Putting It All Together

Once you have determined each of the above 3 categories, you can put them together into the MDM chart to ascertain the overall level of MDM. (The official AMA medical decision-making grid is available online [https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf]). Keep in mind that 2 of 3 columns in the table must be obtained in that level to reach an overall E/M level; for example, a visit that addresses 2 self-limited or minor problems (level 3) in which no data is reviewed (level 2) and involves prescribing a new medication (level 4), would be an overall level 3 visit.

Final Thoughts

The outpatient E/M guidelines have undergone substantial revisions; therefore, it is crucial to understand the updated definitions to ensure proper billing and documentation. History and physical examination documentation must be medically appropriate but are no longer used to determine overall E/M level; time and MDM are the sole options that can be used. Importantly, try to code as accurately as possible, documenting which problems were both noted and addressed. If you are unsure of a definition within the updated changes and MDM table, referencing the appropriate sources for guidance is recommended.

Although representing a considerable shift, the revaluation of this family of codes and the intended decrease in documentation burden has the ability to be a positive gain for dermatologists. Expect other code families to mirror these changes in the next few years.

Effective on January 1, 2021, the outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes underwent substantial changes, which were the culmination of multiple years of revision and surveying via the American Medical Association (AMA) Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Current Procedural Terminology (RUC-CPT) process to streamline definitions and promote consistency as well as to decrease the administrative burden for all specialties within the house of medicine.1 These updates represent a notable change from the previous documentation requirements for this oft used family of codes. Herein, we break down some of the highlights of the changes and how they may be applied for some commonly used dermatologic diagnoses.

Time Is Time Is Time

Prior to the 2021 revisions, a physician generally could only code for an E/M level by time for a face-to-face encounter dominated by counseling and/or care coordination. With the new updates, any encounter can be coded by total time spent by the physician with the patient1; however, clinical staff time is not included. There also are now clear guidelines of the time ranges corresponding to the level of E/M,1 as noted in Table 1.

Importantly, time now includes not just face-to-face time with the patient but also any time on the date of the encounter that the physician is involved in the care of the patient when not reported with a separate code. This can include reviewing notes or data before or after the examination, care coordination, ordering laboratory tests, and providing any documentation related to the encounter. Importantly, this applies only when these activities are done on the date of the encounter.

If you work with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (PA) who assists you and you are the one reporting the service, you cannot double-dip. For example, if your PA spends 10 minutes alone with a patient, you are in the room together for 5 minutes, the PA spends another 10 minutes alone with the patient afterward, and you do chart work for 10 minutes at the end of the day, the total time spent is 35 minutes, not 40 minutes, as you cannot count the time you and the PA spent together twice.

Decisions, Decisions

Evaluation and management coding also can be determined via the level of medical decision-making (MDM). Per the 2021 guidelines, MDM is comprised of 3 categories: (1) number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter, (2) amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed or analyzed, and (3) risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.1 To reach a certain overall E/M level, 2 of 3 categories must be met or exceeded. Let’s dive into each of these in a little more detail.

Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed at the Encounter

First, it is important to understand the definition of a problem addressed. Per AMA guidelines, this includes a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter that is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician. If the problem is referred to another provider without evaluation or consideration of treatment, it is not considered to be a problem addressed and cannot count toward this first category. An example could be a patient with a lump on the abdomen that you refer to plastic or general surgery for evaluation and treatment.

Once you have determined that you are addressing a problem, you will need to determine the level of complexity of the problem, as outlined in Table 2. Keep in mind that some entities and disease states in dermatology may fit the requirements of more than 1 level of complexity depending on the clinical situation, while there are many entities in dermatology that may not be perfectly captured by any of the levels described. In these situations, clinical judgement is required to determine where the problem would best fit. Importantly, whatever you decide, your documentation should support that decision.

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Be Reviewed and Analyzed

This category encompasses any external notes reviewed, unique laboratory tests or imaging ordered or reviewed, the need for an independent historian or discussion with external health care providers or appropriate sources, or independent interpretation of tests. Some high-yield definitions in this category are outlined in Table 3.

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

In this category, risk relates to both the patient’s diagnosis and treatment(s). Importantly, for treatment and diagnostic options, these include both the options selected and those considered but not selected. Risk is defined as the probability and/or consequences of an event and is based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician in the same specialty. In other words, think of the risk as compared to risk in the setting of other dermatologists diagnosing and/or treating the same condition.