User login

MD jailed for road rage, career spirals downhill

It was a 95° F day in July 2015, and emergency physician Martin Maag, MD, was driving down Bee Ridge Road, a busy seven-lane thoroughfare in Sarasota, Fla., on his way home from a family dinner. To distance himself from a truck blowing black smoke, Dr. Maag says he had just passed some vehicles, when a motorcycle flew past him in the turning lane and the passenger flipped him off.

“I started laughing because I knew we were coming up to a red light,” said Dr. Maag. “When we pulled up to the light, I put my window down and said: ‘Hey, you ought to be a little more careful about who you’re flipping off! You never know who it might be and what they might do.’ ”

The female passenger cursed at Dr. Maag, and the two traded profanities. The male driver then told Dr. Maag: “Get out of the car, old man,” according to Dr. Maag. Fuming, Dr. Maag got out of his black Tesla, and the two men met in the middle of the street.

“As soon as I got close enough to see him, I could tell he really looked young,” Dr. Maag recalls. “I said: ‘You’re like 12 years old. I’m going to end up beating your ass and then I’m going to go to jail. Go get on your bike, and ride home to your mom.’ I don’t remember what he said to me, but I spun around and said: ‘If you want to act like a man, meet me up the street in a parking lot and let’s have at it like men.’ ”

The motorcyclist got back on his white Suzuki and sped off, and Dr. Maag followed. Both vehicles went racing down the road, swerving between cars, and reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour, Dr. Maag said. At one point, Dr. Maag says he drove in front of the motorcyclist to slow him down, and the motorcycle clipped the back of his car. No one was seriously hurt, but soon Dr. Maag was in the back of a police cruiser headed to jail.

Dr. Maag wishes he could take back his actions that summer day 6 years ago. Those few minutes of fury have had lasting effects on the doctor’s life. The incident resulted in criminal charges, a jail sentence, thousands of dollars in legal fees, and a 3-year departure from emergency medicine. Although Dr. Maag did not lose his medical license as a result of the incident, the physician’s Medicare billing privileges were suspended because of a federal provision that ties some felonies to enrollment revocations.

“Every doctor, every health professional needs to know that there are a lot of consequences that go with our actions outside of work,” he said. “In my situation, what happened had nothing to do with medicine, it had nothing to do with patients, it had nothing to do my professional demeanor. But yet it affected my entire career, and I lost the ability to practice emergency medicine for 3 years. Three years for any doctor is a long time. Three years for emergency medicine is a lifetime.”

The physician ends up in jail

After the collision, Dr. Maag pulled over in a parking lot and dialed 911. Several passing motorists did the same. It appeared the biker was trying to get away, and Dr. Maag was concerned about the damage to his Tesla, he said.

When police arrived, they heard very different accounts of what happened. The motorcyclist and his girlfriend claimed Dr. Maag was the aggressor during the altercation, and that he deliberately tried to hit them with his vehicle. Two witnesses at the scene said they had watched Dr. Maag pursue the motorcycle in his vehicle, and that they believed he crossed into their lane intentionally to strike the motorcycle, according to police reports.

“[The motorcyclist] stated that the vehicle struck his right foot when it hit the motorcycle and that he was able to keep his balance and not lay the bike down,” Sarasota County Deputy C. Moore wrote in his report. “The motorcycle was damaged on the right side near [his] foot, verifying his story. Both victims were adamant that the defendant actually and intentionally struck the motorcycle with his car due to the previous altercation.”

Dr. Maag told officers the motorcyclist had initiated the confrontation. He acknowledged racing after the biker, but said it was the motorcyclist who hit his vehicle. In an interview, Dr. Maag disputed the witnesses’ accounts, saying that one of the witnesses was without a car and made claims to police that were impossible from her distance.

In the end, the officer believed the motorcyclist, writing in his report that the damage to the Tesla was consistent with the biker’s version of events. Dr. Maag was handcuffed and taken to the Sarasota County Jail.

“I was in shock,” he said. “When we got to the jail, they got me booked in and fingerprinted. I sat down and said [to an officer]: ‘So, when do I get to bond out?’ The guy started laughing and said: ‘You’re not going anywhere. You’re spending the night in jail, my friend.’ He said: ‘Your charge is one step below murder.’”

‘I like to drive fast’

Aside from speeding tickets, Dr. Maag said he had never been in serious trouble with the law before.

The husband and father of two has practiced emergency medicine for more 15 years, and his license has remained in good standing. Florida Department of Health records show Dr. Maag’s medical license as clear and active with no discipline cases or public complaints on file.

“I did my best for every patient that came through that door,” he said. “There were a lot of people who didn’t like my personality. I’ve said many times: ‘I’m not here to be liked. I’m here to take care of people and provide the best care possible.’ ”

Sarasota County records show that Dr. Maag has received traffic citations in the past for careless driving, unlawful speed, and failure to stop at a red light, among others. He admits to having a “lead foot,” but says he had never before been involved in a road rage incident.

“I’m not going to lie, I like to drive fast,” he said. “I like that feeling. It just seems to slow everything down for me, the faster I’m going.”

After being booked into jail that July evening in 2015, Dr. Maag called his wife to explain what happened.

“She said, ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this. I’ve told you a million times, don’t worry about how other people drive. Keep your mouth shut,’” he recalled. “I asked her to call my work and let them know I wouldn’t be coming in the next day. Until that happened, I had never missed a day of work since becoming a physician.”

After an anxious night in his jail cell, Dr. Maag lined up with the other inmates the next morning for his bond hearing. His charges included felony, aggravated battery, and felony aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. A prosecutor recommended Dr. Maag’s bond be set at $1 million, which a judge lowered to $500,000.

Michael Fayard, a criminal defense attorney who represented Dr. Maag in the case, said even with the reduction, $500,000 was an outrageous bond for such a case.

“The prosecutor’s arguments to the judge were that he was a physician driving a Tesla,” Mr. Fayard said. “That was his exact argument for charging him a higher bond. It shouldn’t have been that high. I argued he was not a flight risk. He didn’t even have a passport.”

The Florida State Attorney’s Office did not return messages seeking comment about the case.

Dr. Maag spent 2 more nights in jail while he and his wife came up with $50,000 in cash, in accordance with the 10% bond rule. In the meantime, the government put a lien on their house. A circuit court judge later agreed the bond was excessive, according to Mr. Fayard, but by that time, the $50,000 was paid and Dr. Maag was released.

New evidence lowers charges

Dr. Maag ultimately accepted a plea deal from the prosecutor’s office and pled no contest to one count of felony criminal mischief and one count of misdemeanor reckless driving. In return, the state dropped the two more serious felonies. A no-contest plea is not considered an admission of guilt.

Mr. Fayard said his investigation into the road rage victim unearthed evidence that poked holes in the motorcyclist’s credibility, and that contributed to the plea offer.

“We found tons of evidence about the kid being a hot-rodding rider on his motorcycle, videos of him traveling 140 miles an hour, popping wheelies, and darting in and out of traffic,” he said. “There was a lot of mitigation that came up during the course of the investigation.”

The plea deal was a favorable result for Dr. Maag considering his original charges, Mr. Fayard said. He added that the criminal case could have ended much differently.

“Given the facts of this case and given the fact that there were no serious injuries, we supported the state’s decision to accept our mitigation and come out with the sentence that they did,” Mr. Fayard said. “If there would have been injuries, the outcome would have likely been much worse for Dr. Maag.”

With the plea agreement reached, Dr. Maag faced his next consequence – jail time. He was sentenced to 60 days in jail, a $1,000 fine, 12 months of probation, and 8 months of house arrest. Unlike his first jail stay, Dr. Maag said the second, longer stint behind bars was more relaxing.

“It was the first time since I had become an emergency physician that I remember my dreams,” he recalled. “I had nothing to worry about, nothing to do. All I had to do was get up and eat. Every now and then, I would mop the floors because I’m kind of a clean freak, and I would talk to guys and that was it. It wasn’t bad at all.”

Dr. Maag told no one that he was a doctor because he didn’t want to be treated differently. The anonymity led to interesting tidbits from other inmates about the best pill mills in the area for example, how to make crack cocaine, and selling items for drugs. On his last day in jail, the other inmates learned from his discharge paperwork that Dr. Maag was a physician.

“One of the corrections officers said: ‘You’re a doctor? We’ve never had a doctor in here before!’” Dr. Maag remembers. “He said: ‘What did a doctor do to get into jail?’ I said: ‘Do you really want to know?’ ”

About the time that Dr. Maag was released from jail, the Florida Board of Medicine learned of his charges and began reviewing his case. Mr. Fayard presented the same facts to the board and argued for Dr. Maag to keep his license, emphasizing the offenses in which he was convicted were significantly less severe than the original felonies charged. The board agreed to dismiss the case.

“The probable cause panel for the board of medicine considered the complaint that has been filed against your client in the above referenced case,” Peter Delia, then-assistant general counsel for the Florida Department of Health, wrote in a letter dated April 27, 2016. “After careful review of all information and evidence obtained in this case, the panel determined that probable cause of a violation does not exist and directed this case to be closed.”

A short-lived celebration

Once home, Dr. Maag was on house arrest, but he was granted permission to travel for work. He continued to practice emergency medicine. After several months, authorities dropped the house arrest, and a judge canceled his probation early. It appeared the road rage incident was finally behind him.

But a year later, in 2018, the doctor received a letter from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services informing him that because of his charges, his Medicare number had been revoked in November 2015.

“It took them 3 years to find me and tell me, even though I never moved,” he said. “Medicare said because I never reported this, they were hitting me up with falsification of documentation because I had signed other Medicare paperwork saying I had never been barred from Medicare, because I didn’t know that I was.”

Dr. Maag hired a different attorney to help him fight the 3-year enrollment ban. He requested reconsideration from CMS, but a hearing officer in October 2017 upheld the revocation. Because his privileges had been revoked in 2015, Dr. Maag’s practice group had to return all money billed by Dr. Maag to Medicare over the 3-year period, which totaled about $190,000.

A CMS spokeswoman declined to comment about Dr. Maag’s case, referring a reporter for this news organization to an administrative law judge’s decision that summarizes the agency’s findings.

According to the summary, in separate reconsidered determinations, the CMS hearing officer concluded that the revocation was proper under section 424.535(a)(3). The regulation, enacted in 2011, allows CMS to revoke billing privileges if a provider was convicted of a federal or state felony within the preceding 10 years that the agency determines is detrimental to the Medicare program and its beneficiaries.

The hearing officer reasoned that Dr. Maag “had been convicted of a felony that is akin to assault and, even if it were not, his actions showed a reckless disregard for the safety of others.” She concluded also that CMS could appropriately revoke Dr. Maag’s Medicare enrollment because he did not report his felony conviction within 30 days as required.

Dr. Maag went through several phases of fighting the revocation, including an appeal to the Department of Health & Human Services Departmental Appeals Board. He argued that his plea was a no-contest plea, which is not considered an admission of guilt. Dr. Maag and his attorney provided CMS a 15-page paper about his background, education, career accomplishments, and patient care history. They emphasized that Dr. Maag had never harmed or threatened a patient, and that his offense had nothing to do with his practice.

In February 2021, Judge Carolyn Cozad Hughes, an administrative law judge with CMS, upheld the 3-year revocation. In her decision, she wrote that for purposes of revocation under CMS law, “convicted” means that a judgment of conviction has been entered by a federal, state, or local court regardless of whether the judgment of conviction has been expunged or otherwise removed. She disagreed with Dr. Maag’s contention that his was a crime against property and, therefore, not akin to any of the felony offenses enumerated under the revocation section, which are crimes against persons.

“Even disregarding the allegations contained in the probable cause affidavit, Petitioner cannot escape the undisputed fact, established by his conviction and his own admissions, that the ‘property’ he so ‘willfully and maliciously’ damaged was a motorcycle traveling at a high rate of speed, and, that two young people were sitting atop that motorcycle,” Judge Hughes wrote. “Moreover, as part of the same conduct, he was charged – and convicted – of misdemeanor reckless driving with ‘willful and wanton disregard for the safety of persons or property.’ Thus, even accepting Petitioner’s description of the events, he unquestionably showed no regard for the safety of the young people on that motorcycle.”

Judge Hughes noted that, although Dr. Maag’s crimes may not be among those specified in the regulation, CMS has broad authority to determine which felonies are detrimental to the best interests of the program and its beneficiaries.

A new career path

Unable to practice emergency medicine and beset with debt, Dr. Maag spiraled into a dark depression. His family had to start using retirement money that he was saving for the future care of his son, who has autism.

“I was suicidal,” he said. “There were two times that I came very close to going out to the woods by my house and hanging myself. All I wanted was to have everything go away. My wife saved my life.”

Slowly, Dr. Maag climbed out of the despondency and began considering new career options. After working and training briefly in hair restoration, Dr. Maag became a hair transplant specialist and opened his own hair restoration practice. It was a way to practice and help patients without having to accept Medicare. Today, he is the founder of Honest Hair Restoration in Bradenton, Fla.

Hair restoration is not the type of medicine that he “was designed to do,” Dr. Maag said, but he has embraced its advantages, such as learning about the business aspects of medicine and having a slower-paced work life. The business, which opened in 2019, is doing well and growing steadily.

Earlier this month, Dr. Maag learned CMS had reinstated his Medicare billing privileges. If an opportunity arises to go back into emergency medicine or urgent care, he is open to the possibilities, he said, but he plans to continue hair restoration for now. He hopes the lessons learned from his road rage incident may help others in similar circumstances.

“If I could go back to that very moment, I would’ve just kept my window up and I wouldn’t have said anything,” Dr. Maag said. “I would’ve kept my mouth shut and gone on about my day. Would I have loved it to have never happened? Yeah, and I’d probably be starting my retirement now. Am I stronger now? Well, I’m probably a hell of a lot wiser. But when all is said and done, I don’t want anybody feeling sorry for me. It was all my doing and I have to live with the consequences.”

Mr. Fayard, the attorney, says the case is a cautionary tale for doctors.

“No one is really above the law,” he said. “There aren’t two legal systems. You can’t just pay a little money and be done. At every level, serious charges have serious ramifications for everyone involved. Law enforcement and judges are not going to care of you’re a physician and you commit a crime. But physicians have a lot more on the line than many others. They can lose their ability to practice.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was a 95° F day in July 2015, and emergency physician Martin Maag, MD, was driving down Bee Ridge Road, a busy seven-lane thoroughfare in Sarasota, Fla., on his way home from a family dinner. To distance himself from a truck blowing black smoke, Dr. Maag says he had just passed some vehicles, when a motorcycle flew past him in the turning lane and the passenger flipped him off.

“I started laughing because I knew we were coming up to a red light,” said Dr. Maag. “When we pulled up to the light, I put my window down and said: ‘Hey, you ought to be a little more careful about who you’re flipping off! You never know who it might be and what they might do.’ ”

The female passenger cursed at Dr. Maag, and the two traded profanities. The male driver then told Dr. Maag: “Get out of the car, old man,” according to Dr. Maag. Fuming, Dr. Maag got out of his black Tesla, and the two men met in the middle of the street.

“As soon as I got close enough to see him, I could tell he really looked young,” Dr. Maag recalls. “I said: ‘You’re like 12 years old. I’m going to end up beating your ass and then I’m going to go to jail. Go get on your bike, and ride home to your mom.’ I don’t remember what he said to me, but I spun around and said: ‘If you want to act like a man, meet me up the street in a parking lot and let’s have at it like men.’ ”

The motorcyclist got back on his white Suzuki and sped off, and Dr. Maag followed. Both vehicles went racing down the road, swerving between cars, and reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour, Dr. Maag said. At one point, Dr. Maag says he drove in front of the motorcyclist to slow him down, and the motorcycle clipped the back of his car. No one was seriously hurt, but soon Dr. Maag was in the back of a police cruiser headed to jail.

Dr. Maag wishes he could take back his actions that summer day 6 years ago. Those few minutes of fury have had lasting effects on the doctor’s life. The incident resulted in criminal charges, a jail sentence, thousands of dollars in legal fees, and a 3-year departure from emergency medicine. Although Dr. Maag did not lose his medical license as a result of the incident, the physician’s Medicare billing privileges were suspended because of a federal provision that ties some felonies to enrollment revocations.

“Every doctor, every health professional needs to know that there are a lot of consequences that go with our actions outside of work,” he said. “In my situation, what happened had nothing to do with medicine, it had nothing to do with patients, it had nothing to do my professional demeanor. But yet it affected my entire career, and I lost the ability to practice emergency medicine for 3 years. Three years for any doctor is a long time. Three years for emergency medicine is a lifetime.”

The physician ends up in jail

After the collision, Dr. Maag pulled over in a parking lot and dialed 911. Several passing motorists did the same. It appeared the biker was trying to get away, and Dr. Maag was concerned about the damage to his Tesla, he said.

When police arrived, they heard very different accounts of what happened. The motorcyclist and his girlfriend claimed Dr. Maag was the aggressor during the altercation, and that he deliberately tried to hit them with his vehicle. Two witnesses at the scene said they had watched Dr. Maag pursue the motorcycle in his vehicle, and that they believed he crossed into their lane intentionally to strike the motorcycle, according to police reports.

“[The motorcyclist] stated that the vehicle struck his right foot when it hit the motorcycle and that he was able to keep his balance and not lay the bike down,” Sarasota County Deputy C. Moore wrote in his report. “The motorcycle was damaged on the right side near [his] foot, verifying his story. Both victims were adamant that the defendant actually and intentionally struck the motorcycle with his car due to the previous altercation.”

Dr. Maag told officers the motorcyclist had initiated the confrontation. He acknowledged racing after the biker, but said it was the motorcyclist who hit his vehicle. In an interview, Dr. Maag disputed the witnesses’ accounts, saying that one of the witnesses was without a car and made claims to police that were impossible from her distance.

In the end, the officer believed the motorcyclist, writing in his report that the damage to the Tesla was consistent with the biker’s version of events. Dr. Maag was handcuffed and taken to the Sarasota County Jail.

“I was in shock,” he said. “When we got to the jail, they got me booked in and fingerprinted. I sat down and said [to an officer]: ‘So, when do I get to bond out?’ The guy started laughing and said: ‘You’re not going anywhere. You’re spending the night in jail, my friend.’ He said: ‘Your charge is one step below murder.’”

‘I like to drive fast’

Aside from speeding tickets, Dr. Maag said he had never been in serious trouble with the law before.

The husband and father of two has practiced emergency medicine for more 15 years, and his license has remained in good standing. Florida Department of Health records show Dr. Maag’s medical license as clear and active with no discipline cases or public complaints on file.

“I did my best for every patient that came through that door,” he said. “There were a lot of people who didn’t like my personality. I’ve said many times: ‘I’m not here to be liked. I’m here to take care of people and provide the best care possible.’ ”

Sarasota County records show that Dr. Maag has received traffic citations in the past for careless driving, unlawful speed, and failure to stop at a red light, among others. He admits to having a “lead foot,” but says he had never before been involved in a road rage incident.

“I’m not going to lie, I like to drive fast,” he said. “I like that feeling. It just seems to slow everything down for me, the faster I’m going.”

After being booked into jail that July evening in 2015, Dr. Maag called his wife to explain what happened.

“She said, ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this. I’ve told you a million times, don’t worry about how other people drive. Keep your mouth shut,’” he recalled. “I asked her to call my work and let them know I wouldn’t be coming in the next day. Until that happened, I had never missed a day of work since becoming a physician.”

After an anxious night in his jail cell, Dr. Maag lined up with the other inmates the next morning for his bond hearing. His charges included felony, aggravated battery, and felony aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. A prosecutor recommended Dr. Maag’s bond be set at $1 million, which a judge lowered to $500,000.

Michael Fayard, a criminal defense attorney who represented Dr. Maag in the case, said even with the reduction, $500,000 was an outrageous bond for such a case.

“The prosecutor’s arguments to the judge were that he was a physician driving a Tesla,” Mr. Fayard said. “That was his exact argument for charging him a higher bond. It shouldn’t have been that high. I argued he was not a flight risk. He didn’t even have a passport.”

The Florida State Attorney’s Office did not return messages seeking comment about the case.

Dr. Maag spent 2 more nights in jail while he and his wife came up with $50,000 in cash, in accordance with the 10% bond rule. In the meantime, the government put a lien on their house. A circuit court judge later agreed the bond was excessive, according to Mr. Fayard, but by that time, the $50,000 was paid and Dr. Maag was released.

New evidence lowers charges

Dr. Maag ultimately accepted a plea deal from the prosecutor’s office and pled no contest to one count of felony criminal mischief and one count of misdemeanor reckless driving. In return, the state dropped the two more serious felonies. A no-contest plea is not considered an admission of guilt.

Mr. Fayard said his investigation into the road rage victim unearthed evidence that poked holes in the motorcyclist’s credibility, and that contributed to the plea offer.

“We found tons of evidence about the kid being a hot-rodding rider on his motorcycle, videos of him traveling 140 miles an hour, popping wheelies, and darting in and out of traffic,” he said. “There was a lot of mitigation that came up during the course of the investigation.”

The plea deal was a favorable result for Dr. Maag considering his original charges, Mr. Fayard said. He added that the criminal case could have ended much differently.

“Given the facts of this case and given the fact that there were no serious injuries, we supported the state’s decision to accept our mitigation and come out with the sentence that they did,” Mr. Fayard said. “If there would have been injuries, the outcome would have likely been much worse for Dr. Maag.”

With the plea agreement reached, Dr. Maag faced his next consequence – jail time. He was sentenced to 60 days in jail, a $1,000 fine, 12 months of probation, and 8 months of house arrest. Unlike his first jail stay, Dr. Maag said the second, longer stint behind bars was more relaxing.

“It was the first time since I had become an emergency physician that I remember my dreams,” he recalled. “I had nothing to worry about, nothing to do. All I had to do was get up and eat. Every now and then, I would mop the floors because I’m kind of a clean freak, and I would talk to guys and that was it. It wasn’t bad at all.”

Dr. Maag told no one that he was a doctor because he didn’t want to be treated differently. The anonymity led to interesting tidbits from other inmates about the best pill mills in the area for example, how to make crack cocaine, and selling items for drugs. On his last day in jail, the other inmates learned from his discharge paperwork that Dr. Maag was a physician.

“One of the corrections officers said: ‘You’re a doctor? We’ve never had a doctor in here before!’” Dr. Maag remembers. “He said: ‘What did a doctor do to get into jail?’ I said: ‘Do you really want to know?’ ”

About the time that Dr. Maag was released from jail, the Florida Board of Medicine learned of his charges and began reviewing his case. Mr. Fayard presented the same facts to the board and argued for Dr. Maag to keep his license, emphasizing the offenses in which he was convicted were significantly less severe than the original felonies charged. The board agreed to dismiss the case.

“The probable cause panel for the board of medicine considered the complaint that has been filed against your client in the above referenced case,” Peter Delia, then-assistant general counsel for the Florida Department of Health, wrote in a letter dated April 27, 2016. “After careful review of all information and evidence obtained in this case, the panel determined that probable cause of a violation does not exist and directed this case to be closed.”

A short-lived celebration

Once home, Dr. Maag was on house arrest, but he was granted permission to travel for work. He continued to practice emergency medicine. After several months, authorities dropped the house arrest, and a judge canceled his probation early. It appeared the road rage incident was finally behind him.

But a year later, in 2018, the doctor received a letter from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services informing him that because of his charges, his Medicare number had been revoked in November 2015.

“It took them 3 years to find me and tell me, even though I never moved,” he said. “Medicare said because I never reported this, they were hitting me up with falsification of documentation because I had signed other Medicare paperwork saying I had never been barred from Medicare, because I didn’t know that I was.”

Dr. Maag hired a different attorney to help him fight the 3-year enrollment ban. He requested reconsideration from CMS, but a hearing officer in October 2017 upheld the revocation. Because his privileges had been revoked in 2015, Dr. Maag’s practice group had to return all money billed by Dr. Maag to Medicare over the 3-year period, which totaled about $190,000.

A CMS spokeswoman declined to comment about Dr. Maag’s case, referring a reporter for this news organization to an administrative law judge’s decision that summarizes the agency’s findings.

According to the summary, in separate reconsidered determinations, the CMS hearing officer concluded that the revocation was proper under section 424.535(a)(3). The regulation, enacted in 2011, allows CMS to revoke billing privileges if a provider was convicted of a federal or state felony within the preceding 10 years that the agency determines is detrimental to the Medicare program and its beneficiaries.

The hearing officer reasoned that Dr. Maag “had been convicted of a felony that is akin to assault and, even if it were not, his actions showed a reckless disregard for the safety of others.” She concluded also that CMS could appropriately revoke Dr. Maag’s Medicare enrollment because he did not report his felony conviction within 30 days as required.

Dr. Maag went through several phases of fighting the revocation, including an appeal to the Department of Health & Human Services Departmental Appeals Board. He argued that his plea was a no-contest plea, which is not considered an admission of guilt. Dr. Maag and his attorney provided CMS a 15-page paper about his background, education, career accomplishments, and patient care history. They emphasized that Dr. Maag had never harmed or threatened a patient, and that his offense had nothing to do with his practice.

In February 2021, Judge Carolyn Cozad Hughes, an administrative law judge with CMS, upheld the 3-year revocation. In her decision, she wrote that for purposes of revocation under CMS law, “convicted” means that a judgment of conviction has been entered by a federal, state, or local court regardless of whether the judgment of conviction has been expunged or otherwise removed. She disagreed with Dr. Maag’s contention that his was a crime against property and, therefore, not akin to any of the felony offenses enumerated under the revocation section, which are crimes against persons.

“Even disregarding the allegations contained in the probable cause affidavit, Petitioner cannot escape the undisputed fact, established by his conviction and his own admissions, that the ‘property’ he so ‘willfully and maliciously’ damaged was a motorcycle traveling at a high rate of speed, and, that two young people were sitting atop that motorcycle,” Judge Hughes wrote. “Moreover, as part of the same conduct, he was charged – and convicted – of misdemeanor reckless driving with ‘willful and wanton disregard for the safety of persons or property.’ Thus, even accepting Petitioner’s description of the events, he unquestionably showed no regard for the safety of the young people on that motorcycle.”

Judge Hughes noted that, although Dr. Maag’s crimes may not be among those specified in the regulation, CMS has broad authority to determine which felonies are detrimental to the best interests of the program and its beneficiaries.

A new career path

Unable to practice emergency medicine and beset with debt, Dr. Maag spiraled into a dark depression. His family had to start using retirement money that he was saving for the future care of his son, who has autism.

“I was suicidal,” he said. “There were two times that I came very close to going out to the woods by my house and hanging myself. All I wanted was to have everything go away. My wife saved my life.”

Slowly, Dr. Maag climbed out of the despondency and began considering new career options. After working and training briefly in hair restoration, Dr. Maag became a hair transplant specialist and opened his own hair restoration practice. It was a way to practice and help patients without having to accept Medicare. Today, he is the founder of Honest Hair Restoration in Bradenton, Fla.

Hair restoration is not the type of medicine that he “was designed to do,” Dr. Maag said, but he has embraced its advantages, such as learning about the business aspects of medicine and having a slower-paced work life. The business, which opened in 2019, is doing well and growing steadily.

Earlier this month, Dr. Maag learned CMS had reinstated his Medicare billing privileges. If an opportunity arises to go back into emergency medicine or urgent care, he is open to the possibilities, he said, but he plans to continue hair restoration for now. He hopes the lessons learned from his road rage incident may help others in similar circumstances.

“If I could go back to that very moment, I would’ve just kept my window up and I wouldn’t have said anything,” Dr. Maag said. “I would’ve kept my mouth shut and gone on about my day. Would I have loved it to have never happened? Yeah, and I’d probably be starting my retirement now. Am I stronger now? Well, I’m probably a hell of a lot wiser. But when all is said and done, I don’t want anybody feeling sorry for me. It was all my doing and I have to live with the consequences.”

Mr. Fayard, the attorney, says the case is a cautionary tale for doctors.

“No one is really above the law,” he said. “There aren’t two legal systems. You can’t just pay a little money and be done. At every level, serious charges have serious ramifications for everyone involved. Law enforcement and judges are not going to care of you’re a physician and you commit a crime. But physicians have a lot more on the line than many others. They can lose their ability to practice.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was a 95° F day in July 2015, and emergency physician Martin Maag, MD, was driving down Bee Ridge Road, a busy seven-lane thoroughfare in Sarasota, Fla., on his way home from a family dinner. To distance himself from a truck blowing black smoke, Dr. Maag says he had just passed some vehicles, when a motorcycle flew past him in the turning lane and the passenger flipped him off.

“I started laughing because I knew we were coming up to a red light,” said Dr. Maag. “When we pulled up to the light, I put my window down and said: ‘Hey, you ought to be a little more careful about who you’re flipping off! You never know who it might be and what they might do.’ ”

The female passenger cursed at Dr. Maag, and the two traded profanities. The male driver then told Dr. Maag: “Get out of the car, old man,” according to Dr. Maag. Fuming, Dr. Maag got out of his black Tesla, and the two men met in the middle of the street.

“As soon as I got close enough to see him, I could tell he really looked young,” Dr. Maag recalls. “I said: ‘You’re like 12 years old. I’m going to end up beating your ass and then I’m going to go to jail. Go get on your bike, and ride home to your mom.’ I don’t remember what he said to me, but I spun around and said: ‘If you want to act like a man, meet me up the street in a parking lot and let’s have at it like men.’ ”

The motorcyclist got back on his white Suzuki and sped off, and Dr. Maag followed. Both vehicles went racing down the road, swerving between cars, and reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour, Dr. Maag said. At one point, Dr. Maag says he drove in front of the motorcyclist to slow him down, and the motorcycle clipped the back of his car. No one was seriously hurt, but soon Dr. Maag was in the back of a police cruiser headed to jail.

Dr. Maag wishes he could take back his actions that summer day 6 years ago. Those few minutes of fury have had lasting effects on the doctor’s life. The incident resulted in criminal charges, a jail sentence, thousands of dollars in legal fees, and a 3-year departure from emergency medicine. Although Dr. Maag did not lose his medical license as a result of the incident, the physician’s Medicare billing privileges were suspended because of a federal provision that ties some felonies to enrollment revocations.

“Every doctor, every health professional needs to know that there are a lot of consequences that go with our actions outside of work,” he said. “In my situation, what happened had nothing to do with medicine, it had nothing to do with patients, it had nothing to do my professional demeanor. But yet it affected my entire career, and I lost the ability to practice emergency medicine for 3 years. Three years for any doctor is a long time. Three years for emergency medicine is a lifetime.”

The physician ends up in jail

After the collision, Dr. Maag pulled over in a parking lot and dialed 911. Several passing motorists did the same. It appeared the biker was trying to get away, and Dr. Maag was concerned about the damage to his Tesla, he said.

When police arrived, they heard very different accounts of what happened. The motorcyclist and his girlfriend claimed Dr. Maag was the aggressor during the altercation, and that he deliberately tried to hit them with his vehicle. Two witnesses at the scene said they had watched Dr. Maag pursue the motorcycle in his vehicle, and that they believed he crossed into their lane intentionally to strike the motorcycle, according to police reports.

“[The motorcyclist] stated that the vehicle struck his right foot when it hit the motorcycle and that he was able to keep his balance and not lay the bike down,” Sarasota County Deputy C. Moore wrote in his report. “The motorcycle was damaged on the right side near [his] foot, verifying his story. Both victims were adamant that the defendant actually and intentionally struck the motorcycle with his car due to the previous altercation.”

Dr. Maag told officers the motorcyclist had initiated the confrontation. He acknowledged racing after the biker, but said it was the motorcyclist who hit his vehicle. In an interview, Dr. Maag disputed the witnesses’ accounts, saying that one of the witnesses was without a car and made claims to police that were impossible from her distance.

In the end, the officer believed the motorcyclist, writing in his report that the damage to the Tesla was consistent with the biker’s version of events. Dr. Maag was handcuffed and taken to the Sarasota County Jail.

“I was in shock,” he said. “When we got to the jail, they got me booked in and fingerprinted. I sat down and said [to an officer]: ‘So, when do I get to bond out?’ The guy started laughing and said: ‘You’re not going anywhere. You’re spending the night in jail, my friend.’ He said: ‘Your charge is one step below murder.’”

‘I like to drive fast’

Aside from speeding tickets, Dr. Maag said he had never been in serious trouble with the law before.

The husband and father of two has practiced emergency medicine for more 15 years, and his license has remained in good standing. Florida Department of Health records show Dr. Maag’s medical license as clear and active with no discipline cases or public complaints on file.

“I did my best for every patient that came through that door,” he said. “There were a lot of people who didn’t like my personality. I’ve said many times: ‘I’m not here to be liked. I’m here to take care of people and provide the best care possible.’ ”

Sarasota County records show that Dr. Maag has received traffic citations in the past for careless driving, unlawful speed, and failure to stop at a red light, among others. He admits to having a “lead foot,” but says he had never before been involved in a road rage incident.

“I’m not going to lie, I like to drive fast,” he said. “I like that feeling. It just seems to slow everything down for me, the faster I’m going.”

After being booked into jail that July evening in 2015, Dr. Maag called his wife to explain what happened.

“She said, ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this. I’ve told you a million times, don’t worry about how other people drive. Keep your mouth shut,’” he recalled. “I asked her to call my work and let them know I wouldn’t be coming in the next day. Until that happened, I had never missed a day of work since becoming a physician.”

After an anxious night in his jail cell, Dr. Maag lined up with the other inmates the next morning for his bond hearing. His charges included felony, aggravated battery, and felony aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. A prosecutor recommended Dr. Maag’s bond be set at $1 million, which a judge lowered to $500,000.

Michael Fayard, a criminal defense attorney who represented Dr. Maag in the case, said even with the reduction, $500,000 was an outrageous bond for such a case.

“The prosecutor’s arguments to the judge were that he was a physician driving a Tesla,” Mr. Fayard said. “That was his exact argument for charging him a higher bond. It shouldn’t have been that high. I argued he was not a flight risk. He didn’t even have a passport.”

The Florida State Attorney’s Office did not return messages seeking comment about the case.

Dr. Maag spent 2 more nights in jail while he and his wife came up with $50,000 in cash, in accordance with the 10% bond rule. In the meantime, the government put a lien on their house. A circuit court judge later agreed the bond was excessive, according to Mr. Fayard, but by that time, the $50,000 was paid and Dr. Maag was released.

New evidence lowers charges

Dr. Maag ultimately accepted a plea deal from the prosecutor’s office and pled no contest to one count of felony criminal mischief and one count of misdemeanor reckless driving. In return, the state dropped the two more serious felonies. A no-contest plea is not considered an admission of guilt.

Mr. Fayard said his investigation into the road rage victim unearthed evidence that poked holes in the motorcyclist’s credibility, and that contributed to the plea offer.

“We found tons of evidence about the kid being a hot-rodding rider on his motorcycle, videos of him traveling 140 miles an hour, popping wheelies, and darting in and out of traffic,” he said. “There was a lot of mitigation that came up during the course of the investigation.”

The plea deal was a favorable result for Dr. Maag considering his original charges, Mr. Fayard said. He added that the criminal case could have ended much differently.

“Given the facts of this case and given the fact that there were no serious injuries, we supported the state’s decision to accept our mitigation and come out with the sentence that they did,” Mr. Fayard said. “If there would have been injuries, the outcome would have likely been much worse for Dr. Maag.”

With the plea agreement reached, Dr. Maag faced his next consequence – jail time. He was sentenced to 60 days in jail, a $1,000 fine, 12 months of probation, and 8 months of house arrest. Unlike his first jail stay, Dr. Maag said the second, longer stint behind bars was more relaxing.

“It was the first time since I had become an emergency physician that I remember my dreams,” he recalled. “I had nothing to worry about, nothing to do. All I had to do was get up and eat. Every now and then, I would mop the floors because I’m kind of a clean freak, and I would talk to guys and that was it. It wasn’t bad at all.”

Dr. Maag told no one that he was a doctor because he didn’t want to be treated differently. The anonymity led to interesting tidbits from other inmates about the best pill mills in the area for example, how to make crack cocaine, and selling items for drugs. On his last day in jail, the other inmates learned from his discharge paperwork that Dr. Maag was a physician.

“One of the corrections officers said: ‘You’re a doctor? We’ve never had a doctor in here before!’” Dr. Maag remembers. “He said: ‘What did a doctor do to get into jail?’ I said: ‘Do you really want to know?’ ”

About the time that Dr. Maag was released from jail, the Florida Board of Medicine learned of his charges and began reviewing his case. Mr. Fayard presented the same facts to the board and argued for Dr. Maag to keep his license, emphasizing the offenses in which he was convicted were significantly less severe than the original felonies charged. The board agreed to dismiss the case.

“The probable cause panel for the board of medicine considered the complaint that has been filed against your client in the above referenced case,” Peter Delia, then-assistant general counsel for the Florida Department of Health, wrote in a letter dated April 27, 2016. “After careful review of all information and evidence obtained in this case, the panel determined that probable cause of a violation does not exist and directed this case to be closed.”

A short-lived celebration

Once home, Dr. Maag was on house arrest, but he was granted permission to travel for work. He continued to practice emergency medicine. After several months, authorities dropped the house arrest, and a judge canceled his probation early. It appeared the road rage incident was finally behind him.

But a year later, in 2018, the doctor received a letter from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services informing him that because of his charges, his Medicare number had been revoked in November 2015.

“It took them 3 years to find me and tell me, even though I never moved,” he said. “Medicare said because I never reported this, they were hitting me up with falsification of documentation because I had signed other Medicare paperwork saying I had never been barred from Medicare, because I didn’t know that I was.”

Dr. Maag hired a different attorney to help him fight the 3-year enrollment ban. He requested reconsideration from CMS, but a hearing officer in October 2017 upheld the revocation. Because his privileges had been revoked in 2015, Dr. Maag’s practice group had to return all money billed by Dr. Maag to Medicare over the 3-year period, which totaled about $190,000.

A CMS spokeswoman declined to comment about Dr. Maag’s case, referring a reporter for this news organization to an administrative law judge’s decision that summarizes the agency’s findings.

According to the summary, in separate reconsidered determinations, the CMS hearing officer concluded that the revocation was proper under section 424.535(a)(3). The regulation, enacted in 2011, allows CMS to revoke billing privileges if a provider was convicted of a federal or state felony within the preceding 10 years that the agency determines is detrimental to the Medicare program and its beneficiaries.

The hearing officer reasoned that Dr. Maag “had been convicted of a felony that is akin to assault and, even if it were not, his actions showed a reckless disregard for the safety of others.” She concluded also that CMS could appropriately revoke Dr. Maag’s Medicare enrollment because he did not report his felony conviction within 30 days as required.

Dr. Maag went through several phases of fighting the revocation, including an appeal to the Department of Health & Human Services Departmental Appeals Board. He argued that his plea was a no-contest plea, which is not considered an admission of guilt. Dr. Maag and his attorney provided CMS a 15-page paper about his background, education, career accomplishments, and patient care history. They emphasized that Dr. Maag had never harmed or threatened a patient, and that his offense had nothing to do with his practice.

In February 2021, Judge Carolyn Cozad Hughes, an administrative law judge with CMS, upheld the 3-year revocation. In her decision, she wrote that for purposes of revocation under CMS law, “convicted” means that a judgment of conviction has been entered by a federal, state, or local court regardless of whether the judgment of conviction has been expunged or otherwise removed. She disagreed with Dr. Maag’s contention that his was a crime against property and, therefore, not akin to any of the felony offenses enumerated under the revocation section, which are crimes against persons.

“Even disregarding the allegations contained in the probable cause affidavit, Petitioner cannot escape the undisputed fact, established by his conviction and his own admissions, that the ‘property’ he so ‘willfully and maliciously’ damaged was a motorcycle traveling at a high rate of speed, and, that two young people were sitting atop that motorcycle,” Judge Hughes wrote. “Moreover, as part of the same conduct, he was charged – and convicted – of misdemeanor reckless driving with ‘willful and wanton disregard for the safety of persons or property.’ Thus, even accepting Petitioner’s description of the events, he unquestionably showed no regard for the safety of the young people on that motorcycle.”

Judge Hughes noted that, although Dr. Maag’s crimes may not be among those specified in the regulation, CMS has broad authority to determine which felonies are detrimental to the best interests of the program and its beneficiaries.

A new career path

Unable to practice emergency medicine and beset with debt, Dr. Maag spiraled into a dark depression. His family had to start using retirement money that he was saving for the future care of his son, who has autism.

“I was suicidal,” he said. “There were two times that I came very close to going out to the woods by my house and hanging myself. All I wanted was to have everything go away. My wife saved my life.”

Slowly, Dr. Maag climbed out of the despondency and began considering new career options. After working and training briefly in hair restoration, Dr. Maag became a hair transplant specialist and opened his own hair restoration practice. It was a way to practice and help patients without having to accept Medicare. Today, he is the founder of Honest Hair Restoration in Bradenton, Fla.

Hair restoration is not the type of medicine that he “was designed to do,” Dr. Maag said, but he has embraced its advantages, such as learning about the business aspects of medicine and having a slower-paced work life. The business, which opened in 2019, is doing well and growing steadily.

Earlier this month, Dr. Maag learned CMS had reinstated his Medicare billing privileges. If an opportunity arises to go back into emergency medicine or urgent care, he is open to the possibilities, he said, but he plans to continue hair restoration for now. He hopes the lessons learned from his road rage incident may help others in similar circumstances.

“If I could go back to that very moment, I would’ve just kept my window up and I wouldn’t have said anything,” Dr. Maag said. “I would’ve kept my mouth shut and gone on about my day. Would I have loved it to have never happened? Yeah, and I’d probably be starting my retirement now. Am I stronger now? Well, I’m probably a hell of a lot wiser. But when all is said and done, I don’t want anybody feeling sorry for me. It was all my doing and I have to live with the consequences.”

Mr. Fayard, the attorney, says the case is a cautionary tale for doctors.

“No one is really above the law,” he said. “There aren’t two legal systems. You can’t just pay a little money and be done. At every level, serious charges have serious ramifications for everyone involved. Law enforcement and judges are not going to care of you’re a physician and you commit a crime. But physicians have a lot more on the line than many others. They can lose their ability to practice.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patient-facing mobile apps: Are ObGyns uniquely positioned to integrate them into practice?

Incorporating mobile apps into patient care programs can add immense value. Mobile apps enable data collection when a patient is beyond the walls of a doctor’s office and equip clinicians with new and relevant patient data. Patient engagement apps also provide a mechanism to “nudge” patients to encourage adherence to their care programs. These additional data and increased patient adherence can enable more personalized care,1 and ultimately can lead to improved outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 1,657 patients with diabetes showed a 5% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values for those who used a diabetes-related app.2 The literature also shows positive results for heart failure, weight management, smoking reduction, and lifestyle improvement.3-5 Given their value, why aren’t patient engagement apps more routinely integrated into patient care programs?

From a software development perspective, mobile apps are fairly easy to create. However, from a user retention standpoint, creating an app with a large, sustainable userbase is challenging.5 User retention is measured in monthly active users. We are familiar with unused apps collecting digital dust on our smartphone home screens. A 2019 study showed that 25% of people typically use an application only once,6 and health care apps are not an exception. There are hundreds of thousands of mobile health apps on the market, but only 7% of these applications have more than 50,000 monthly active users. Further, 62% of digital health apps have less than 1,000 monthly active users.7

Using a new app daily or several times weekly requires new habit formation. Anyone who has tried to incorporate a new routine into their daily life knows how difficult habit formation can be. However, ObGyn patients may be particularly well suited to incorporate ObGyn-related apps into their care, given how many women already use mobile applications to track their menstrual cycles. A recent survey found that across all age groups, 47% of women use a mobile phone app to track their menstrual cycle,8 compared with 8% of US adults who regularly use an app to measure general health metrics.7 This removes one of the largest obstacles of market penetration since the habit of using an app for ObGyn purposes has already been established. As such, it presents an exciting opportunity to capitalize on the userbase already leveraging mobile apps to track their cycles and expand the patient engagement footprint into additional features that can broaden care to create a seamless, holistic patient application for ObGyn patient care.

One can envision a future in which a patient is “prescribed” an ObGyn app during their ObGyn appointment. Within the app, the patient can track their health data, engage with health providers, and gain access to educational materials. The clinician would be able to access data captured in the patient app at an aggregate level to analyze trends over time.

Current, patient-facing ObGyn mobile apps available for download on smartphones are for targeted aspects of ObGyn health. For example, there are separate apps for menstrual cycle tracking, contraception education, and medication adherence tracking. In the future, it would be ideal for clinicians and patients to have access to a single, holistic ObGyn mobile app that supports the end-to-end ObGyn patient journey, one in which clinicians could turn modules on or off given specific patient concerns. The technology for this type of holistic patient engagement platform exists, but unfortunately it is not as simple as downloading a mobile app. Standing up an end-to-end patient engagement platform requires enterprise-wide buy-in, tailoring user workflows, and building out integrations (eg, integrating provider dashboards into the existing electronic health record system). Full-scale solutions are powerful, but they can be expensive and time consuming to stand up. Until there is a more streamlined, outside-the-box ObGyn-tailored solution, there are patientfacing mobile apps available to support your patients for specific concerns.

Continue to: The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps...

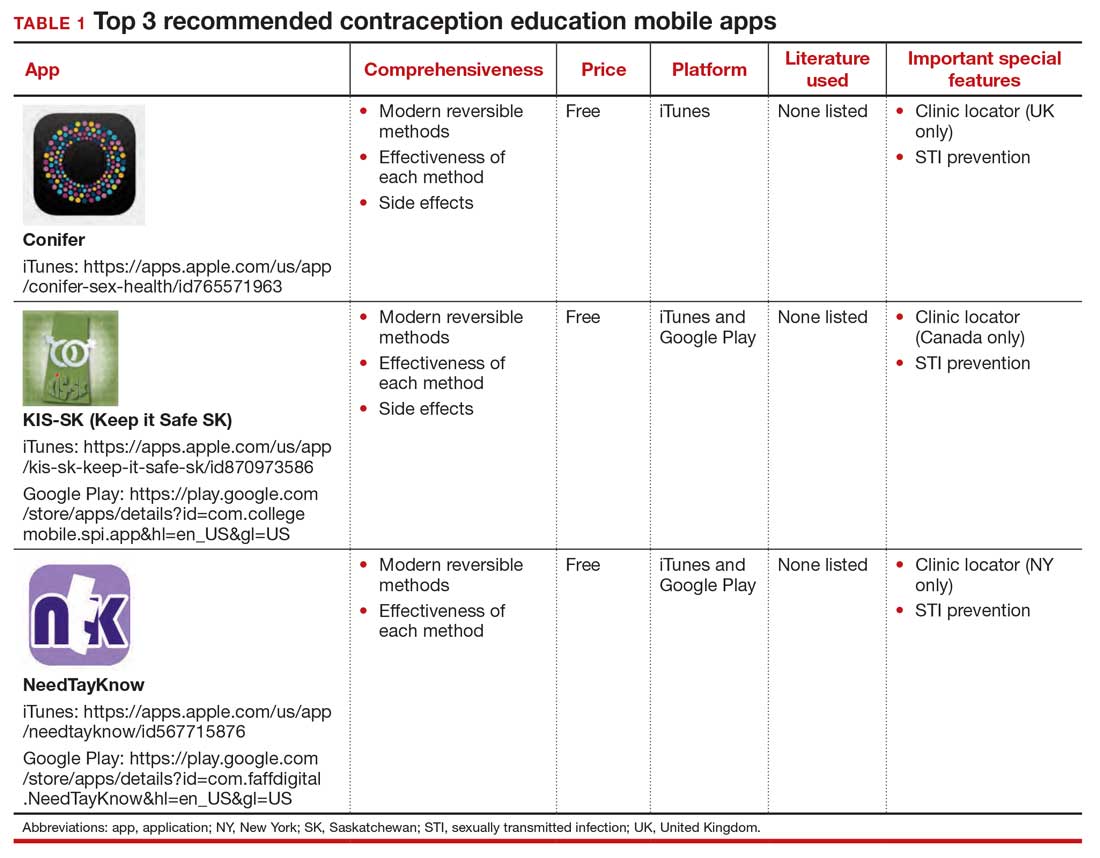

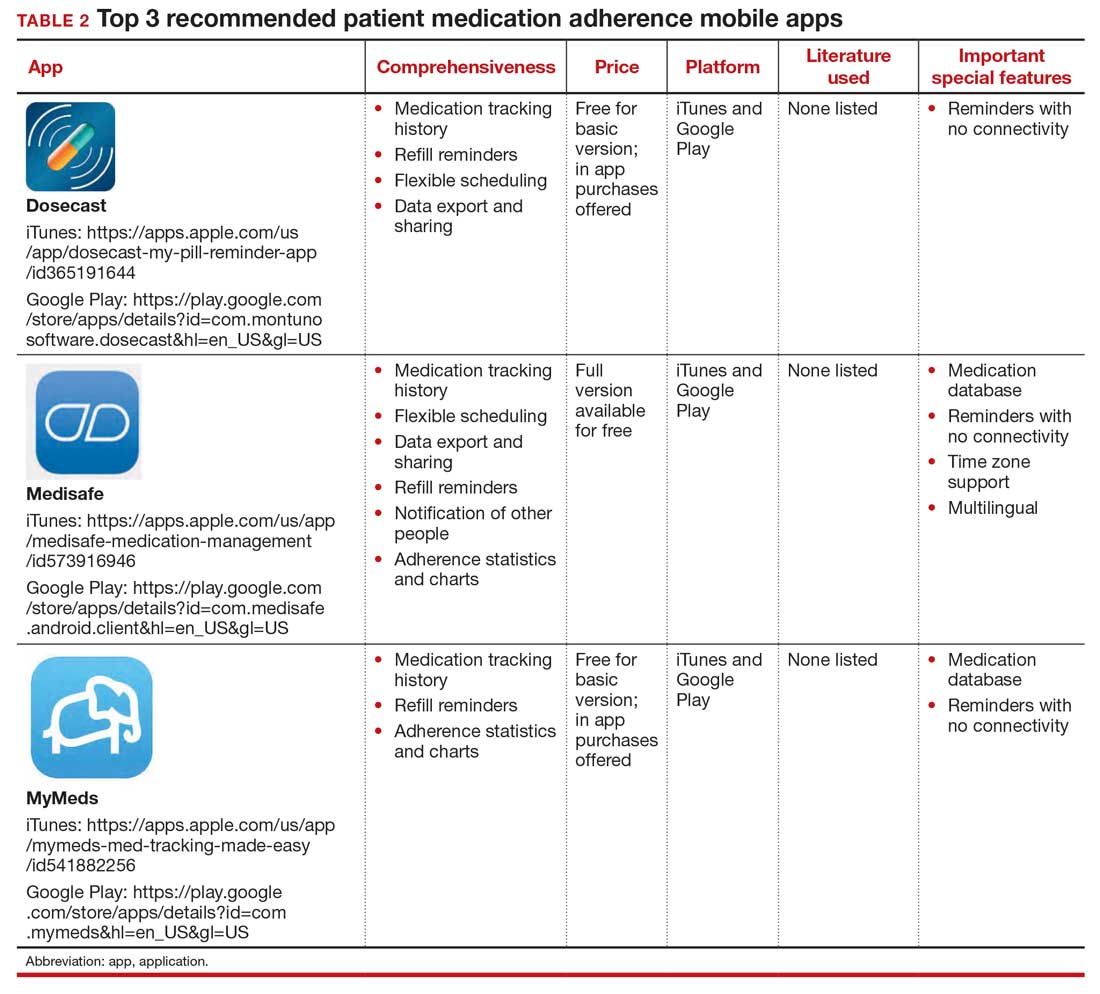

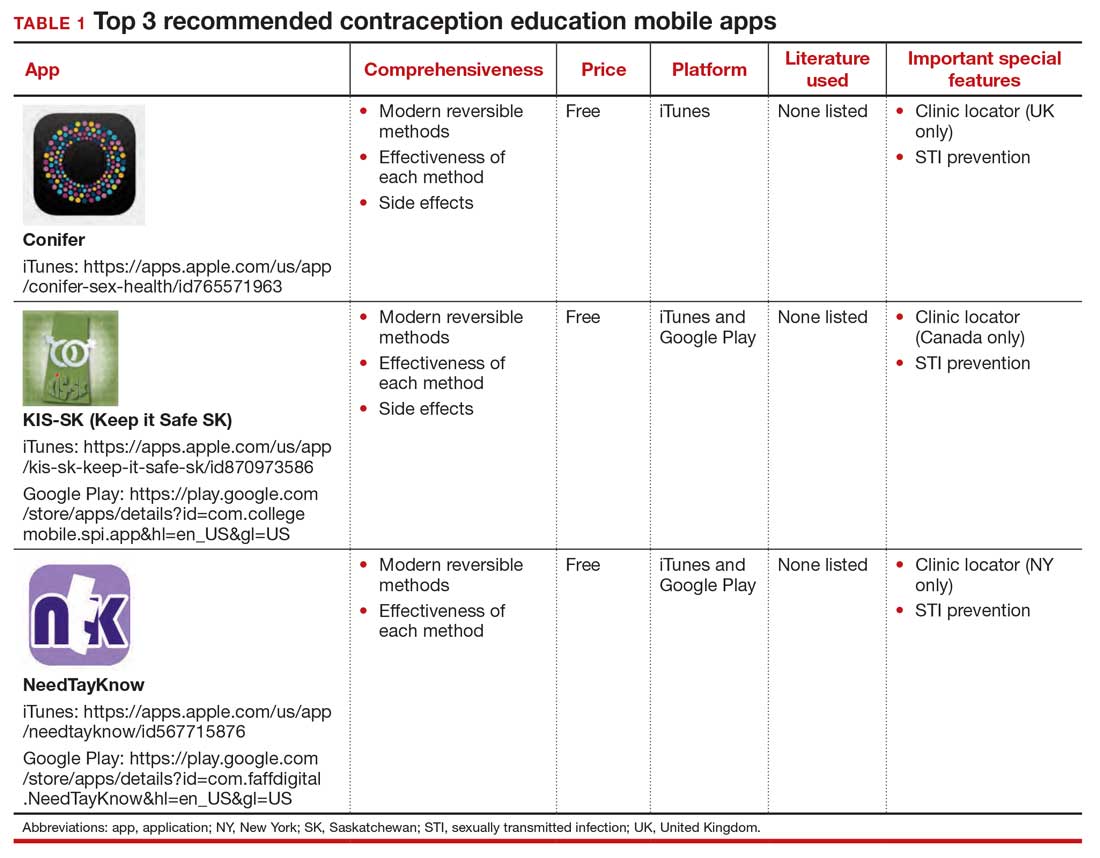

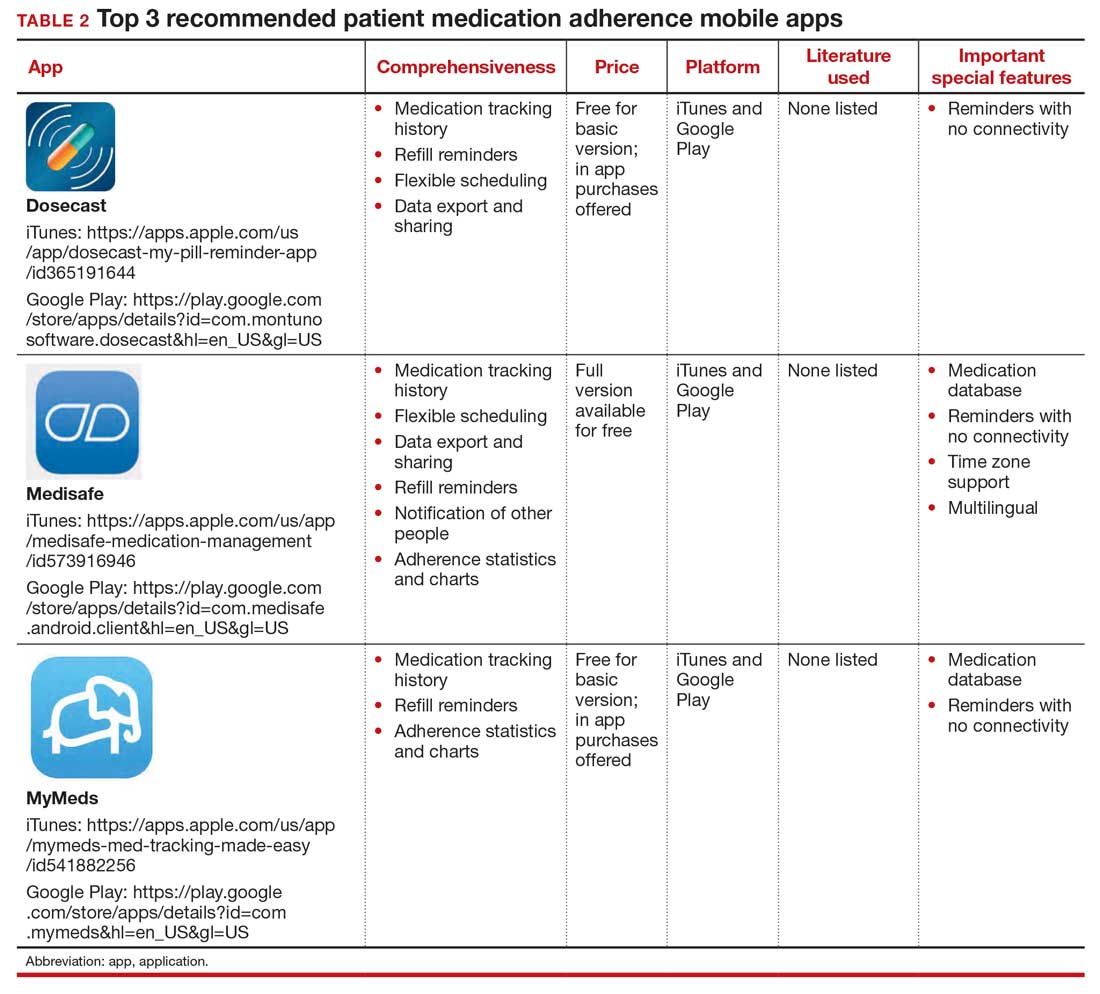

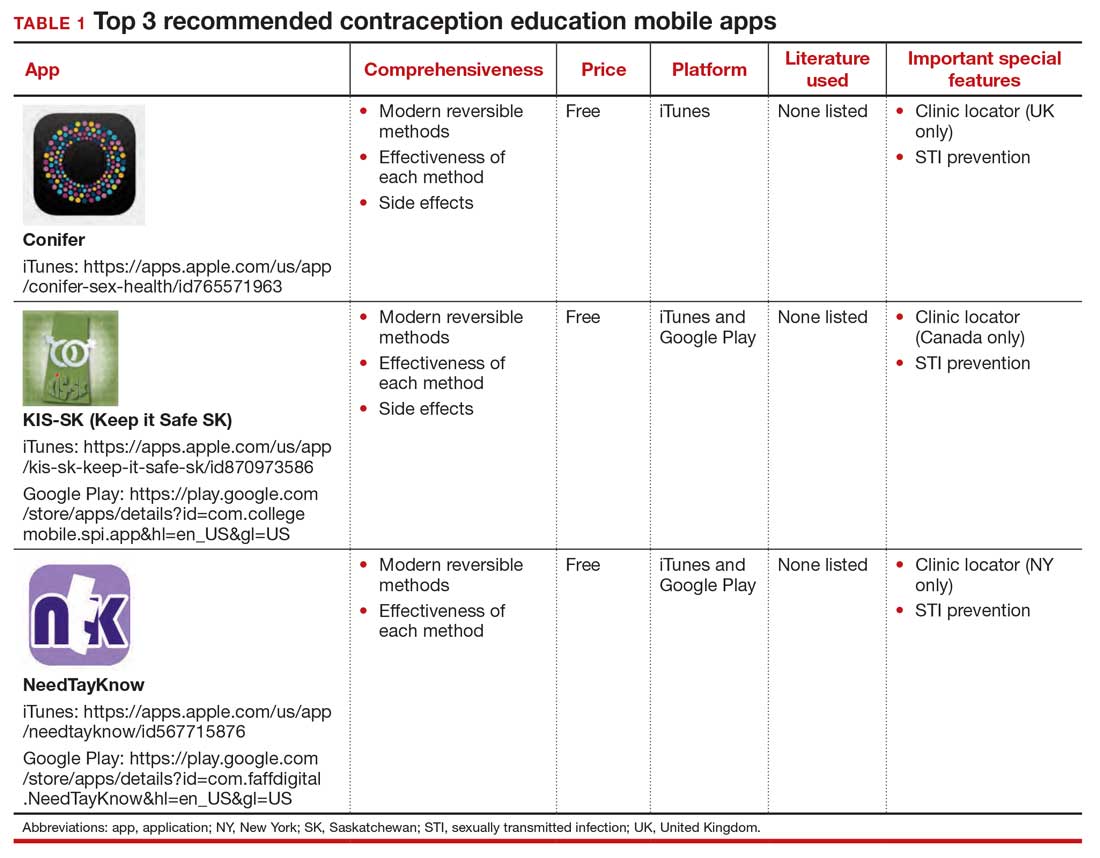

The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps from Moglia and colleagues9 are listed in Dr. Chen’s article, “Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients.”10 The top 3 recommended contraception education mobile apps from Lunde and colleagues11 are listed in TABLE 1 and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, important special features).12 The top 3 recommended patient medication adherence mobile apps from the study by Santo and colleagues13 are listed in TABLE 2. The apps in the Stoyanov et al14 study were evaluated using the 23-item Mobile App Rating System scale. ●

- van Dijk MR, Koster MPH, et al. Healthy preconception nutrition and lifestyle using personalized mobile health coaching is associated with enhanced pregnancy chance. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35:453-460. doi:10.1016/j. rbmo.2017.06.014.

- Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a metaanalysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2010.03180.x.

- Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl):S5-S12. doi:10.7326/m13-3005.

- Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:E86. doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:127. doi:10.1186/s12966- 016-0454-y.

- 25% of users abandon apps after one use. Upland Software website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://uplandsoftware.com /localytics/resources/blog/25-of-users-abandon-apps-afterone-use/.

- mHealth economics 2017/2018 – connectivity in digital health. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https:// research2guidance.com/product/connectivity-in-digitalhealth/.

- Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2017;2017:6876- 6888. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025635.

- Moglia M, Nguyen H, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:1153-1160. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444.

- Chen KT. Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients. OBG Manag. 2017;27:44-45.

- Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.012.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000842.

- Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, et al. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: a systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:E132. doi:10.2196/mhealth.6742.

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:E27. doi:10.2196 /mhealth.3422.

Incorporating mobile apps into patient care programs can add immense value. Mobile apps enable data collection when a patient is beyond the walls of a doctor’s office and equip clinicians with new and relevant patient data. Patient engagement apps also provide a mechanism to “nudge” patients to encourage adherence to their care programs. These additional data and increased patient adherence can enable more personalized care,1 and ultimately can lead to improved outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 1,657 patients with diabetes showed a 5% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values for those who used a diabetes-related app.2 The literature also shows positive results for heart failure, weight management, smoking reduction, and lifestyle improvement.3-5 Given their value, why aren’t patient engagement apps more routinely integrated into patient care programs?

From a software development perspective, mobile apps are fairly easy to create. However, from a user retention standpoint, creating an app with a large, sustainable userbase is challenging.5 User retention is measured in monthly active users. We are familiar with unused apps collecting digital dust on our smartphone home screens. A 2019 study showed that 25% of people typically use an application only once,6 and health care apps are not an exception. There are hundreds of thousands of mobile health apps on the market, but only 7% of these applications have more than 50,000 monthly active users. Further, 62% of digital health apps have less than 1,000 monthly active users.7

Using a new app daily or several times weekly requires new habit formation. Anyone who has tried to incorporate a new routine into their daily life knows how difficult habit formation can be. However, ObGyn patients may be particularly well suited to incorporate ObGyn-related apps into their care, given how many women already use mobile applications to track their menstrual cycles. A recent survey found that across all age groups, 47% of women use a mobile phone app to track their menstrual cycle,8 compared with 8% of US adults who regularly use an app to measure general health metrics.7 This removes one of the largest obstacles of market penetration since the habit of using an app for ObGyn purposes has already been established. As such, it presents an exciting opportunity to capitalize on the userbase already leveraging mobile apps to track their cycles and expand the patient engagement footprint into additional features that can broaden care to create a seamless, holistic patient application for ObGyn patient care.

One can envision a future in which a patient is “prescribed” an ObGyn app during their ObGyn appointment. Within the app, the patient can track their health data, engage with health providers, and gain access to educational materials. The clinician would be able to access data captured in the patient app at an aggregate level to analyze trends over time.

Current, patient-facing ObGyn mobile apps available for download on smartphones are for targeted aspects of ObGyn health. For example, there are separate apps for menstrual cycle tracking, contraception education, and medication adherence tracking. In the future, it would be ideal for clinicians and patients to have access to a single, holistic ObGyn mobile app that supports the end-to-end ObGyn patient journey, one in which clinicians could turn modules on or off given specific patient concerns. The technology for this type of holistic patient engagement platform exists, but unfortunately it is not as simple as downloading a mobile app. Standing up an end-to-end patient engagement platform requires enterprise-wide buy-in, tailoring user workflows, and building out integrations (eg, integrating provider dashboards into the existing electronic health record system). Full-scale solutions are powerful, but they can be expensive and time consuming to stand up. Until there is a more streamlined, outside-the-box ObGyn-tailored solution, there are patientfacing mobile apps available to support your patients for specific concerns.

Continue to: The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps...

The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps from Moglia and colleagues9 are listed in Dr. Chen’s article, “Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients.”10 The top 3 recommended contraception education mobile apps from Lunde and colleagues11 are listed in TABLE 1 and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, important special features).12 The top 3 recommended patient medication adherence mobile apps from the study by Santo and colleagues13 are listed in TABLE 2. The apps in the Stoyanov et al14 study were evaluated using the 23-item Mobile App Rating System scale. ●

Incorporating mobile apps into patient care programs can add immense value. Mobile apps enable data collection when a patient is beyond the walls of a doctor’s office and equip clinicians with new and relevant patient data. Patient engagement apps also provide a mechanism to “nudge” patients to encourage adherence to their care programs. These additional data and increased patient adherence can enable more personalized care,1 and ultimately can lead to improved outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 1,657 patients with diabetes showed a 5% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values for those who used a diabetes-related app.2 The literature also shows positive results for heart failure, weight management, smoking reduction, and lifestyle improvement.3-5 Given their value, why aren’t patient engagement apps more routinely integrated into patient care programs?

From a software development perspective, mobile apps are fairly easy to create. However, from a user retention standpoint, creating an app with a large, sustainable userbase is challenging.5 User retention is measured in monthly active users. We are familiar with unused apps collecting digital dust on our smartphone home screens. A 2019 study showed that 25% of people typically use an application only once,6 and health care apps are not an exception. There are hundreds of thousands of mobile health apps on the market, but only 7% of these applications have more than 50,000 monthly active users. Further, 62% of digital health apps have less than 1,000 monthly active users.7

Using a new app daily or several times weekly requires new habit formation. Anyone who has tried to incorporate a new routine into their daily life knows how difficult habit formation can be. However, ObGyn patients may be particularly well suited to incorporate ObGyn-related apps into their care, given how many women already use mobile applications to track their menstrual cycles. A recent survey found that across all age groups, 47% of women use a mobile phone app to track their menstrual cycle,8 compared with 8% of US adults who regularly use an app to measure general health metrics.7 This removes one of the largest obstacles of market penetration since the habit of using an app for ObGyn purposes has already been established. As such, it presents an exciting opportunity to capitalize on the userbase already leveraging mobile apps to track their cycles and expand the patient engagement footprint into additional features that can broaden care to create a seamless, holistic patient application for ObGyn patient care.

One can envision a future in which a patient is “prescribed” an ObGyn app during their ObGyn appointment. Within the app, the patient can track their health data, engage with health providers, and gain access to educational materials. The clinician would be able to access data captured in the patient app at an aggregate level to analyze trends over time.

Current, patient-facing ObGyn mobile apps available for download on smartphones are for targeted aspects of ObGyn health. For example, there are separate apps for menstrual cycle tracking, contraception education, and medication adherence tracking. In the future, it would be ideal for clinicians and patients to have access to a single, holistic ObGyn mobile app that supports the end-to-end ObGyn patient journey, one in which clinicians could turn modules on or off given specific patient concerns. The technology for this type of holistic patient engagement platform exists, but unfortunately it is not as simple as downloading a mobile app. Standing up an end-to-end patient engagement platform requires enterprise-wide buy-in, tailoring user workflows, and building out integrations (eg, integrating provider dashboards into the existing electronic health record system). Full-scale solutions are powerful, but they can be expensive and time consuming to stand up. Until there is a more streamlined, outside-the-box ObGyn-tailored solution, there are patientfacing mobile apps available to support your patients for specific concerns.

Continue to: The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps...

The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps from Moglia and colleagues9 are listed in Dr. Chen’s article, “Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients.”10 The top 3 recommended contraception education mobile apps from Lunde and colleagues11 are listed in TABLE 1 and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, important special features).12 The top 3 recommended patient medication adherence mobile apps from the study by Santo and colleagues13 are listed in TABLE 2. The apps in the Stoyanov et al14 study were evaluated using the 23-item Mobile App Rating System scale. ●

- van Dijk MR, Koster MPH, et al. Healthy preconception nutrition and lifestyle using personalized mobile health coaching is associated with enhanced pregnancy chance. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35:453-460. doi:10.1016/j. rbmo.2017.06.014.

- Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a metaanalysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2010.03180.x.

- Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl):S5-S12. doi:10.7326/m13-3005.

- Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:E86. doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:127. doi:10.1186/s12966- 016-0454-y.

- 25% of users abandon apps after one use. Upland Software website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://uplandsoftware.com /localytics/resources/blog/25-of-users-abandon-apps-afterone-use/.

- mHealth economics 2017/2018 – connectivity in digital health. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https:// research2guidance.com/product/connectivity-in-digitalhealth/.

- Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2017;2017:6876- 6888. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025635.

- Moglia M, Nguyen H, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:1153-1160. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444.

- Chen KT. Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients. OBG Manag. 2017;27:44-45.

- Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.012.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000842.

- Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, et al. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: a systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:E132. doi:10.2196/mhealth.6742.

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:E27. doi:10.2196 /mhealth.3422.

- van Dijk MR, Koster MPH, et al. Healthy preconception nutrition and lifestyle using personalized mobile health coaching is associated with enhanced pregnancy chance. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35:453-460. doi:10.1016/j. rbmo.2017.06.014.

- Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a metaanalysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2010.03180.x.

- Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl):S5-S12. doi:10.7326/m13-3005.

- Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:E86. doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:127. doi:10.1186/s12966- 016-0454-y.

- 25% of users abandon apps after one use. Upland Software website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://uplandsoftware.com /localytics/resources/blog/25-of-users-abandon-apps-afterone-use/.

- mHealth economics 2017/2018 – connectivity in digital health. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https:// research2guidance.com/product/connectivity-in-digitalhealth/.

- Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2017;2017:6876- 6888. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025635.

- Moglia M, Nguyen H, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:1153-1160. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444.

- Chen KT. Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients. OBG Manag. 2017;27:44-45.

- Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.012.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000842.

- Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, et al. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: a systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:E132. doi:10.2196/mhealth.6742.

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:E27. doi:10.2196 /mhealth.3422.

Dermatoethics for Dermatology Residents

As dermatology residents, we have a lot on our plates. With so many diagnoses to learn and treatments to understand, the sheer volume of knowledge we are expected to be familiar with sometimes can be overwhelming. The thought of adding yet another thing to the list of many things we already need to know—least of all a topic such as dermatoethics—may be unappealing. This article will discuss the importance of ethics training in dermatology residency as well as provide helpful resources for how this training can be achieved.

Professionalism as a Core Competency

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) considers professionalism as 1 of its 6 core competencies.1 These competencies provide a conceptual framework detailing the domains physicians should be proficient in before they can enter autonomous practice. When it comes to professionalism, residents are expected to demonstrate compassion, integrity, and respect for others; honesty with patients; respect for patient confidentiality and autonomy; appropriate relationships with patients; accountability to patients, society, and the profession; and a sensitivity and responsiveness to diverse patient population.1

The ACGME milestones are intended to assess resident development within the 6 competencies with more specific parameters for evaluation.2 Those pertaining to professionalism evaluate a resident’s ability to demonstrate professional behavior, an understanding of ethical principles, accountability, and conscientiousness, as well as self-awareness and the ability to seek help for personal or professional well-being. The crux of the kinds of activities that constitute acquisition of these professional skills are specialty specific. The ACGME ultimately believes that having a working knowledge of professionalism and ethical principles prepares residents for practicing medicine in the real world. Because of these requirements, residency programs are expected to provide resources for residents to explore ethical problems faced by dermatologists.

Beyond “Passing” Residency

The reality is that learning about medical ethics and practicing professional behavior is not just about ticking boxes to get ACGME accreditation or to “pass” residency. The data suggest that having a strong foundation in these principles is good for overall personal well-being, job satisfaction, and patient care. Studies have shown that unprofessional behavior in medical school is correlated to disciplinary action by state licensing boards against practicing physicians.3,4 In fact, a study found that in one cohort of physicians (N=68), 95% of disciplinary actions were for lapses in professionalism, which included activities such as sexual misconduct and inappropriate prescribing.4 Behaving appropriately protects your license to practice medicine.