User login

‘Malicious peer review’ destroyed doc’s career, he says

Cardiothoracic surgeon J. Marvin Smith III, MD, had always thrived on a busy practice schedule, often performing 20-30 surgeries a week. A practicing surgeon for more than 40 years, Dr. Smith said he had no plans to slow down anytime soon.

But Dr. Smith said his career was derailed when leaders at Methodist Healthcare System of San Antonio initiated a sudden peer review proceeding against him. The hospital system alleged certain surgeries performed by Dr. Smith had excessive mortality rates. When he proved the data inaccurate, Dr. Smith said administrators next claimed he was cognitively impaired and wasn’t safe to practice.

Dr. Smith has now been embroiled in a peer review dispute with the hospital system for more than 2 years and says the conflict has essentially forced him out of surgical practice. He believes the peer review was “malicious” and was really launched because of complaints he made about nurse staffing and other issues at the hospital.

“I think it is absolutely in bad faith and is disingenuous what they’ve told me along the way,” said Dr. Smith, 73. “It’s because I pointed out deficiencies in nursing care, and they want to get rid of me. It would be a lot easier for them if I had a contract and they could control me better. But the fact that I was independent, meant they had to resort to a malicious peer review to try and push me out.”

Dr. Smith had a peer review hearing with Methodist in March 2021, and in April, a panel found in Dr. Smith’s favor, according to Dr. Smith. The findings were sent to the hospital’s medical board for review, which issued a decision in early May.

Eric A. Pullen, an attorney for Dr. Smith, said he could not go into detail about the board’s decision for legal reasons, but that “the medical board’s decision did not completely resolve the matter, and Dr. Smith intends to exercise his procedural rights, which could include an appeal.”

Methodist Hospital Texsan and its parent company, Methodist Health System of San Antonio, did not respond to messages seeking comment about the case. Without hearing from the hospital system, its side is unknown and it is unclear if there is more to the story from Methodist’s view.

The problem is not new, but some experts, such as Lawrence Huntoon, MD, PhD, say the practice has become more common in recent years, particularly against independent doctors.

Dr. Huntoon believes there is a nationwide trend at many hospitals to get rid of independent physicians and replace them with employed doctors, he said.

However, because most sham peer reviews go on behind closed doors, there are no data to pinpoint its prevalence or measure its growth.

“Independent physicians are basically being purged from medical staffs across the United States,” said Dr. Huntoon, who is chair of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons’ Committee to Combat Sham Peer Review. “The hospitals want more control over how physicians practice and who they refer to, and they do that by having employees.”

Anthony P. Weiss, MD, MBA, chief medical officer for Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center said it has not been his experience that independent physicians are being targeted in such a way. Dr. Weiss responded to an inquiry sent to the American Hospital Association for this story.

“As the authority for peer review rests with the organized medical staff (i.e., physicians), and not formally with the hospital per se, the peer review lever is not typically available as a management tool for hospital administration,” said Dr. Weiss, who is a former member of the AHA’s Committee on Clinical Leadership, but who was speaking on behalf of himself.

A spokesman for the AHA said the organization stands behinds Dr. Weiss’ comments.

Peer review remains a foundational aspect of overseeing the safety and appropriateness of healthcare provided by physicians, Dr. Weiss said. Peer review likely varies from hospital to hospital, he added, although the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act provides some level of guidance as does the American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics (section 9.4.1).

“In essence, both require that the evaluation be conducted in good faith with the intention to improve care, by physicians with adequate training and knowledge, using a process that is fair and inclusive of the physician under review,” he said. “I believe that most medical staffs abide by these ethical principles, but we have little data to confirm this supposition.”

Did hospital target doc for being vocal?

When members of Methodist’s medical staff first approached Dr. Smith with concerns about his surgery outcomes in November 2018, the physician says he was surprised, but that he was open to an assessment.

“They came to me and said they thought my numbers were bad, and I said: ‘Well my gosh, I certainly don’t want that to be the case. I need to see what numbers you are talking about,’ ” Dr. Smith recalled. “I’ve been president of the Bexar County Medical Society; I’ve been involved with standards and ethics for the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Quality health care means a whole lot to me.”

The statistical information provided by hospital administrators indicated that Dr. Smith’s mortality rates for coronary artery surgery in 2018 were “excessive” and that his rates for aortic surgery were “unacceptable,” according to a lawsuit Dr. Smith filed against the hospital system. Dr. Smith, who is double boarded with the American Board of Surgery and the American Board of Thoracic Surgery, said his outcomes had never come into question in the past. Dr. Smith said the timing was suspicious to him, however, considering he had recently raised concerns with the hospital through letters about nursing performance, staffing, and compensation.

A peer review investigation was initiated. In the meantime, Dr. Smith agreed to intensivist consults on his postoperative patients and consults with the hospital’s “Heart Team” on all preoperative cardiac, valve, and aortic cases. A vocal critic of the Heart Team, Dr. Smith had long contended the entity provided no meaningful benefit to his patients in most cases and, rather, increased hospital stays and raised medical expenses. Despite his agreement, Dr. Smith was later asked to voluntarily stop performing surgeries at the hospital.

“I agreed, convinced that we’d get this all settled,” he said.

Another report issued by the hospital in 2019 also indicated elevated mortality rates associated with some of Smith’s surgeries, although the document differed from the first report, according to the lawsuit. Dr. Smith says he was ignored when he pointed out problems with the data, including a lack of appropriate risk stratification in the report, departure from Society of Thoracic Surgeons data rules, and improper inclusion of his cases in the denominator of the ratio when a comparison was made of his outcomes with those hospitalwide. A subsequent report from Methodist in March 2019 indicated Dr. Smith’s surgery outcomes were “within the expected parameters of performance,” according to court documents.

The surgery accusations were dropped, but the peer review proceeding against Dr. Smith wasn’t over. The hospital next requested that Dr. Smith undergo a competency evaluation.

“When they realized the data was bad, they then changed their argument in the peer review proceeding and essentially started to argue that Dr. Smith had some sort of cognitive disability that prevented him from continuing to practice,” said Mr. Pullen. “The way I look at it, when the initial basis for the peer review was proven false, the hospital found something else and some other reason to try to keep Dr. Smith from practicing.”

Thus began a lengthy disagreement about which entity would conduct the evaluation, who would pay, and the type of acceptable assessment. An evaluation by the hospital’s preferred organization resulted in a finding of mild cognitive impairment, Dr. Smith said. He hired his own experts who conducted separate evaluations, finding no impairment and no basis for the former evaluation’s conclusion.

“Literally, the determinant as to whether I was normal or below normal on their test was one point, which was associated with a finding that I didn’t draw a clock correctly,” Dr. Smith claimed. “The reviewer said my minute hand was a little too short and docked me a point. It was purely subjective. To me, the gold standard of whether you are learned in thoracic surgery is the American Board of Thoracic Surgery’s test. The board’s test shows my cognitive ability is entirely in keeping with my practice. That contrasts with the one point off I got for drawing a clock wrong in somebody’s estimation.”

Conflict leads to legal case

In September 2020, Dr. Smith filed a lawsuit against Methodist Healthcare System of San Antonio, alleging business disparagement by Methodist for allegedly publishing false and disparaging information about Dr. Smith and tortious interference with business relations. The latter claim stems from Methodist refusing to provide documents to other hospitals about the status of Dr. Smith’s privileges at Methodist, Mr. Pullen said.

Because Methodist refused to confirm his status, the renewal process for Baptist Health System could not be completed and Dr. Smith lost his privileges at Baptist Health System facilities, according to the lawsuit.

Notably, Dr. Smith’s legal challenge also asks the court to take a stance against alleged amendments by Methodist to its Unified Medical Staff Bylaws. The hospital allegedly proposed changes that would prevent physicians from seeking legal action against the hospital for malicious peer review, according to Dr. Smith’s lawsuit.

The amendments would make the peer review process itself the “sole and exclusive remedy with respect to any action or recommendation taken at the hospital affecting medical staff appointment and/or clinical privileges,” according to an excerpt of the proposed amendments included in Dr. Smith’s lawsuit. In addition, the changes would hold practitioners liable for lost revenues if the doctor initiates “any type of legal action challenging credentialing, privileging, or other medical peer review or professional review activity,” according to the lawsuit.

Dr. Smith’s lawsuit seeks a declaration that the proposed amendments to the bylaws are “void as against public policy,” and a declaration that the proposed amendments to the bylaws cannot take away physicians’ statutory right to bring litigation against Methodist for malicious peer review.

“The proposed amendments have a tendency to and will injure the public good,” Dr. Smith argued in the lawsuit. “The proposed amendments allow Methodist to act with malice and in bad faith in conducting peer review proceedings and face no legal repercussions.”

Regardless of the final outcome of the peer review proceeding, Mr. Pullen said the harm Dr. Smith has already endured cannot be reversed.

“Even if comes out in his favor, the damage is already done,” he said. “It will not remedy the damage Dr. Smith has incurred.”

Fighting sham peer review is difficult

Battling a malicious peer review has long been an uphill battle for physicians, according to Dr. Huntoon. That’s because the Health Care Quality Improvement Act (HCQIA), a federal law passed in 1986, provides near absolute immunity to hospitals and peer reviewers in legal disputes.

The HCQIA was created by Congress to extend immunity to good-faith peer review of doctors and to increase overall participation in peer review by removing fear of litigation. However, the act has also enabled abuse of peer review by shielding bad-faith reviewers from accountability, said Dr. Huntoon.

“The Health Care Quality Improvement Act presumes that what the hospital did was warranted and reasonable and shifts the burden to the physician to prove his innocence by a preponderance of evidence,” he said. “That’s an entirely foreign concept to most people who think a person should be considered innocent until proven guilty. Here, it’s the exact opposite.”

The HCQIA has been challenged numerous times over the years and tested at the appellate level, but continues to survive and remain settled law, added Richard B. Willner, DPM, founder and director of the Center for Peer Review Justice, which assists and counsels physicians about sham peer review.

In 2011, former Rep. Joe Heck, DO, (R-Nev.) introduced a bill that would have amended the HCQIA to prohibit a professional review entity from submitting a report to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) while the doctor was still under investigation and before the doctor was afforded adequate notice and a hearing. Although the measure had 16 cosponsors and plenty of support from the physician community, it failed.

In addition to a heavy legal burden, physicians who experience malicious peer reviews also face ramifications from being reported to the NPDB. Peer review organizations are required to report certain negative actions or findings to the NPDB.

“A databank entry is a scarlet letter on your forehead,” Dr. Willner said. “The rules at a lot of institutions are not to take anyone who has been databanked, rightfully or wrongfully. And what is the evidence necessary to databank you? None. There’s no evidence needed to databank somebody.”

Despite the bleak landscape, experts say progress has been made on a case-by-case basis by physicians who have succeeded in fighting back against questionable peer reviews in recent years.

In January 2020, Indiana ob.gyn. Rebecca Denman, MD, prevailed in her defamation lawsuit against St Vincent Carmel Hospital and St Vincent Carmel Medical Group, winning $4.75 million in damages. Dr. Denman alleged administrators failed to conduct a proper peer review investigation after a false allegation by a nurse that she was under the influence while on the job.

Indianapolis attorney Kathleen A. DeLaney, who represented Dr. Denman, said hospital leaders misled Dr. Denman into believing a peer review had occurred when no formal peer review hearing or proceeding took place.

“The CMO of the medical group claimed that he performed a peer review ‘screening,’ but he never informed the other members of the peer review executive committee of the matter until after he had placed Dr. Denman on administrative leave,” Ms. DeLaney said. “He also neglected to tell the peer review executive committee that the substance abuse policy had not been followed, or that Dr. Denman had not been tested for alcohol use – due to the 12-hour delay in report.”

Dr. Denman was ultimately required to undergo an alcohol abuse evaluation, enter a treatment program, and sign a 5-year monitoring contract with the Indiana State Medical Association as a condition of her employment, according to the lawsuit. She claimed repercussions from the false allegation resulted in lost compensation, out-of-pocket expenses, emotional distress, and damage to her professional reputation.

She sued the hospital in July 2018, alleging fraud, defamation, tortious interference with an employment relationship, and negligent misrepresentation. After a 4-day trial, jurors found in her favor, awarding Dr. Denman $2 million for her defamation claims, $2 million for her claims of fraud and constructive fraud, $500,000 for her claim of tortious interference with an employment relationship, and $250,000 for her claim of negligent misrepresentation.

A hospital spokesperson said Ascension St Vincent is pursuing an appeal, and that it looks “forward to the opportunity to bring this matter before the Indiana Court of Appeals in June.”

In another case, South Dakota surgeon Linda Miller, MD, was awarded $1.1 million in 2017 after a federal jury found Huron Regional Medical Center breached her contract and violated her due process rights. Dr. Miller became the subject of a peer review at Huron Regional Medical Center when the hospital began analyzing some of her surgery outcomes.

Ken Barker, an attorney for Dr. Miller, said he feels it became evident at trial that the campaign to force Dr. Miller to either resign or lose her privileges was led by the lay board of directors of the hospital and upper-level administration at the hospital.

“They began the process by ordering an unprecedented 90-day review of her medical charts, looking for errors in the medical care she provided patients,” he said. “They could find nothing, so they did a second 90-day review, waiting for a patient’s ‘bad outcome.’ As any general surgeon will say, a ‘bad outcome’ is inevitable. And so it was. Upon that occurrence, they had a medical review committee review the patient’s chart and use it as an excuse to force her to reduce her privileges. Unbeknown to Dr. Miller, an external review had been conducted on another patient’s chart, in which the external review found her care above the standards and, in some measure, ‘exemplary.’ ”

Dr. Miller was eventually pressured to resign, according to her claim. Because of reports made to the NPDB by the medical center, including a patient complication that was allegedly falsified by the hospital, Dr. Miller said she was unable to find work as a general surgeon and went to work as a wound care doctor. At trial, jurors awarded Dr. Miller $586,617 in lost wages, $343,640 for lost future earning capacity, and $250,000 for mental anguish. (The mental anguish award was subsequently struck by a district court.)

Attorneys for Huron Regional Medical Center argued the jury improperly awarded damages and requested a new trial, which was denied by an appeals court.

In the end, the evidence came to light and the jury’s verdict spoke loudly that the hospital had taken unfair advantage of Dr. Miller, Mr. Barker said. But he emphasized that such cases often end differently.

“There are a handful of cases in which physicians like Dr. Miller have challenged the system and won,” he said. “In most cases, however, it is a ‘David vs. Goliath’ scenario where the giant prevails.”

What to do if faced with malicious peer review

An important step when doctors encounter a peer review that they believe is malicious is to consult with an experienced attorney as early as possible, Dr. Huntoon said. “Not all attorneys who set themselves out to be health law attorneys necessarily have knowledge and expertise in sham peer review. And before such a thing happens, I always encourage physicians to read their medical staff bylaws. That’s where everything is set forth, [such as] the corrective action section that tells how peer review is to take place.”

Mr. Barker added that documentation is also key in the event of a potential malicious peer review.

“When a physician senses [the] administration has targeted them, they should start documenting their conversations and actions very carefully, and if possible, recruit another ‘observer’ who can provide a third-party perspective, if necessary,” Mr. Barker said.

Dr. Huntoon recently wrote an article with advice about preparedness and defense of sham peer reviews. The guidance includes that physicians educate themselves about the tactics used by some hospitals to conduct sham peer reviews and the factors that place doctors more at risk. Factors that may raise a doctor’s danger of being targeted include being in solo practice or a small group, being new on staff, or being an older physician approaching retirement as some bad-actor hospitals may view older physicians as being less likely to fight back, said Dr. Huntoon.

Doctors should also keep detailed records and a timeline in the event of a malicious peer review and insist that an independent court reporter record all peer review hearings, even if that means the physician has to pay for the reporter him or herself, according to the guidance. An independent record is invaluable should the physician ultimately issue a future legal challenge against the hospital.

Mr. Willner encourages physicians to call the Center for Peer Review Justice hotline at (504) 621-1670 or visit the website for help with peer review and NPDB issues.

As for Dr. Smith, his days are much quieter and slower today, compared with the active practice he was accustomed to for more than half his life. He misses the fast pace, the patients, and the work that always brought him great joy.

“I hope to get back to doing surgeries eventually,” he said. “I graduated medical school in 1972. Practicing surgery has been my whole life and my career. They have taken my identity and my livelihood away from me based on false numbers and false premises. I want it back.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiothoracic surgeon J. Marvin Smith III, MD, had always thrived on a busy practice schedule, often performing 20-30 surgeries a week. A practicing surgeon for more than 40 years, Dr. Smith said he had no plans to slow down anytime soon.

But Dr. Smith said his career was derailed when leaders at Methodist Healthcare System of San Antonio initiated a sudden peer review proceeding against him. The hospital system alleged certain surgeries performed by Dr. Smith had excessive mortality rates. When he proved the data inaccurate, Dr. Smith said administrators next claimed he was cognitively impaired and wasn’t safe to practice.

Dr. Smith has now been embroiled in a peer review dispute with the hospital system for more than 2 years and says the conflict has essentially forced him out of surgical practice. He believes the peer review was “malicious” and was really launched because of complaints he made about nurse staffing and other issues at the hospital.

“I think it is absolutely in bad faith and is disingenuous what they’ve told me along the way,” said Dr. Smith, 73. “It’s because I pointed out deficiencies in nursing care, and they want to get rid of me. It would be a lot easier for them if I had a contract and they could control me better. But the fact that I was independent, meant they had to resort to a malicious peer review to try and push me out.”

Dr. Smith had a peer review hearing with Methodist in March 2021, and in April, a panel found in Dr. Smith’s favor, according to Dr. Smith. The findings were sent to the hospital’s medical board for review, which issued a decision in early May.

Eric A. Pullen, an attorney for Dr. Smith, said he could not go into detail about the board’s decision for legal reasons, but that “the medical board’s decision did not completely resolve the matter, and Dr. Smith intends to exercise his procedural rights, which could include an appeal.”

Methodist Hospital Texsan and its parent company, Methodist Health System of San Antonio, did not respond to messages seeking comment about the case. Without hearing from the hospital system, its side is unknown and it is unclear if there is more to the story from Methodist’s view.

The problem is not new, but some experts, such as Lawrence Huntoon, MD, PhD, say the practice has become more common in recent years, particularly against independent doctors.

Dr. Huntoon believes there is a nationwide trend at many hospitals to get rid of independent physicians and replace them with employed doctors, he said.

However, because most sham peer reviews go on behind closed doors, there are no data to pinpoint its prevalence or measure its growth.

“Independent physicians are basically being purged from medical staffs across the United States,” said Dr. Huntoon, who is chair of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons’ Committee to Combat Sham Peer Review. “The hospitals want more control over how physicians practice and who they refer to, and they do that by having employees.”

Anthony P. Weiss, MD, MBA, chief medical officer for Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center said it has not been his experience that independent physicians are being targeted in such a way. Dr. Weiss responded to an inquiry sent to the American Hospital Association for this story.

“As the authority for peer review rests with the organized medical staff (i.e., physicians), and not formally with the hospital per se, the peer review lever is not typically available as a management tool for hospital administration,” said Dr. Weiss, who is a former member of the AHA’s Committee on Clinical Leadership, but who was speaking on behalf of himself.

A spokesman for the AHA said the organization stands behinds Dr. Weiss’ comments.

Peer review remains a foundational aspect of overseeing the safety and appropriateness of healthcare provided by physicians, Dr. Weiss said. Peer review likely varies from hospital to hospital, he added, although the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act provides some level of guidance as does the American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics (section 9.4.1).

“In essence, both require that the evaluation be conducted in good faith with the intention to improve care, by physicians with adequate training and knowledge, using a process that is fair and inclusive of the physician under review,” he said. “I believe that most medical staffs abide by these ethical principles, but we have little data to confirm this supposition.”

Did hospital target doc for being vocal?

When members of Methodist’s medical staff first approached Dr. Smith with concerns about his surgery outcomes in November 2018, the physician says he was surprised, but that he was open to an assessment.

“They came to me and said they thought my numbers were bad, and I said: ‘Well my gosh, I certainly don’t want that to be the case. I need to see what numbers you are talking about,’ ” Dr. Smith recalled. “I’ve been president of the Bexar County Medical Society; I’ve been involved with standards and ethics for the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Quality health care means a whole lot to me.”

The statistical information provided by hospital administrators indicated that Dr. Smith’s mortality rates for coronary artery surgery in 2018 were “excessive” and that his rates for aortic surgery were “unacceptable,” according to a lawsuit Dr. Smith filed against the hospital system. Dr. Smith, who is double boarded with the American Board of Surgery and the American Board of Thoracic Surgery, said his outcomes had never come into question in the past. Dr. Smith said the timing was suspicious to him, however, considering he had recently raised concerns with the hospital through letters about nursing performance, staffing, and compensation.

A peer review investigation was initiated. In the meantime, Dr. Smith agreed to intensivist consults on his postoperative patients and consults with the hospital’s “Heart Team” on all preoperative cardiac, valve, and aortic cases. A vocal critic of the Heart Team, Dr. Smith had long contended the entity provided no meaningful benefit to his patients in most cases and, rather, increased hospital stays and raised medical expenses. Despite his agreement, Dr. Smith was later asked to voluntarily stop performing surgeries at the hospital.

“I agreed, convinced that we’d get this all settled,” he said.

Another report issued by the hospital in 2019 also indicated elevated mortality rates associated with some of Smith’s surgeries, although the document differed from the first report, according to the lawsuit. Dr. Smith says he was ignored when he pointed out problems with the data, including a lack of appropriate risk stratification in the report, departure from Society of Thoracic Surgeons data rules, and improper inclusion of his cases in the denominator of the ratio when a comparison was made of his outcomes with those hospitalwide. A subsequent report from Methodist in March 2019 indicated Dr. Smith’s surgery outcomes were “within the expected parameters of performance,” according to court documents.

The surgery accusations were dropped, but the peer review proceeding against Dr. Smith wasn’t over. The hospital next requested that Dr. Smith undergo a competency evaluation.

“When they realized the data was bad, they then changed their argument in the peer review proceeding and essentially started to argue that Dr. Smith had some sort of cognitive disability that prevented him from continuing to practice,” said Mr. Pullen. “The way I look at it, when the initial basis for the peer review was proven false, the hospital found something else and some other reason to try to keep Dr. Smith from practicing.”

Thus began a lengthy disagreement about which entity would conduct the evaluation, who would pay, and the type of acceptable assessment. An evaluation by the hospital’s preferred organization resulted in a finding of mild cognitive impairment, Dr. Smith said. He hired his own experts who conducted separate evaluations, finding no impairment and no basis for the former evaluation’s conclusion.

“Literally, the determinant as to whether I was normal or below normal on their test was one point, which was associated with a finding that I didn’t draw a clock correctly,” Dr. Smith claimed. “The reviewer said my minute hand was a little too short and docked me a point. It was purely subjective. To me, the gold standard of whether you are learned in thoracic surgery is the American Board of Thoracic Surgery’s test. The board’s test shows my cognitive ability is entirely in keeping with my practice. That contrasts with the one point off I got for drawing a clock wrong in somebody’s estimation.”

Conflict leads to legal case

In September 2020, Dr. Smith filed a lawsuit against Methodist Healthcare System of San Antonio, alleging business disparagement by Methodist for allegedly publishing false and disparaging information about Dr. Smith and tortious interference with business relations. The latter claim stems from Methodist refusing to provide documents to other hospitals about the status of Dr. Smith’s privileges at Methodist, Mr. Pullen said.

Because Methodist refused to confirm his status, the renewal process for Baptist Health System could not be completed and Dr. Smith lost his privileges at Baptist Health System facilities, according to the lawsuit.

Notably, Dr. Smith’s legal challenge also asks the court to take a stance against alleged amendments by Methodist to its Unified Medical Staff Bylaws. The hospital allegedly proposed changes that would prevent physicians from seeking legal action against the hospital for malicious peer review, according to Dr. Smith’s lawsuit.

The amendments would make the peer review process itself the “sole and exclusive remedy with respect to any action or recommendation taken at the hospital affecting medical staff appointment and/or clinical privileges,” according to an excerpt of the proposed amendments included in Dr. Smith’s lawsuit. In addition, the changes would hold practitioners liable for lost revenues if the doctor initiates “any type of legal action challenging credentialing, privileging, or other medical peer review or professional review activity,” according to the lawsuit.

Dr. Smith’s lawsuit seeks a declaration that the proposed amendments to the bylaws are “void as against public policy,” and a declaration that the proposed amendments to the bylaws cannot take away physicians’ statutory right to bring litigation against Methodist for malicious peer review.

“The proposed amendments have a tendency to and will injure the public good,” Dr. Smith argued in the lawsuit. “The proposed amendments allow Methodist to act with malice and in bad faith in conducting peer review proceedings and face no legal repercussions.”

Regardless of the final outcome of the peer review proceeding, Mr. Pullen said the harm Dr. Smith has already endured cannot be reversed.

“Even if comes out in his favor, the damage is already done,” he said. “It will not remedy the damage Dr. Smith has incurred.”

Fighting sham peer review is difficult

Battling a malicious peer review has long been an uphill battle for physicians, according to Dr. Huntoon. That’s because the Health Care Quality Improvement Act (HCQIA), a federal law passed in 1986, provides near absolute immunity to hospitals and peer reviewers in legal disputes.

The HCQIA was created by Congress to extend immunity to good-faith peer review of doctors and to increase overall participation in peer review by removing fear of litigation. However, the act has also enabled abuse of peer review by shielding bad-faith reviewers from accountability, said Dr. Huntoon.

“The Health Care Quality Improvement Act presumes that what the hospital did was warranted and reasonable and shifts the burden to the physician to prove his innocence by a preponderance of evidence,” he said. “That’s an entirely foreign concept to most people who think a person should be considered innocent until proven guilty. Here, it’s the exact opposite.”

The HCQIA has been challenged numerous times over the years and tested at the appellate level, but continues to survive and remain settled law, added Richard B. Willner, DPM, founder and director of the Center for Peer Review Justice, which assists and counsels physicians about sham peer review.

In 2011, former Rep. Joe Heck, DO, (R-Nev.) introduced a bill that would have amended the HCQIA to prohibit a professional review entity from submitting a report to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) while the doctor was still under investigation and before the doctor was afforded adequate notice and a hearing. Although the measure had 16 cosponsors and plenty of support from the physician community, it failed.

In addition to a heavy legal burden, physicians who experience malicious peer reviews also face ramifications from being reported to the NPDB. Peer review organizations are required to report certain negative actions or findings to the NPDB.

“A databank entry is a scarlet letter on your forehead,” Dr. Willner said. “The rules at a lot of institutions are not to take anyone who has been databanked, rightfully or wrongfully. And what is the evidence necessary to databank you? None. There’s no evidence needed to databank somebody.”

Despite the bleak landscape, experts say progress has been made on a case-by-case basis by physicians who have succeeded in fighting back against questionable peer reviews in recent years.

In January 2020, Indiana ob.gyn. Rebecca Denman, MD, prevailed in her defamation lawsuit against St Vincent Carmel Hospital and St Vincent Carmel Medical Group, winning $4.75 million in damages. Dr. Denman alleged administrators failed to conduct a proper peer review investigation after a false allegation by a nurse that she was under the influence while on the job.

Indianapolis attorney Kathleen A. DeLaney, who represented Dr. Denman, said hospital leaders misled Dr. Denman into believing a peer review had occurred when no formal peer review hearing or proceeding took place.

“The CMO of the medical group claimed that he performed a peer review ‘screening,’ but he never informed the other members of the peer review executive committee of the matter until after he had placed Dr. Denman on administrative leave,” Ms. DeLaney said. “He also neglected to tell the peer review executive committee that the substance abuse policy had not been followed, or that Dr. Denman had not been tested for alcohol use – due to the 12-hour delay in report.”

Dr. Denman was ultimately required to undergo an alcohol abuse evaluation, enter a treatment program, and sign a 5-year monitoring contract with the Indiana State Medical Association as a condition of her employment, according to the lawsuit. She claimed repercussions from the false allegation resulted in lost compensation, out-of-pocket expenses, emotional distress, and damage to her professional reputation.

She sued the hospital in July 2018, alleging fraud, defamation, tortious interference with an employment relationship, and negligent misrepresentation. After a 4-day trial, jurors found in her favor, awarding Dr. Denman $2 million for her defamation claims, $2 million for her claims of fraud and constructive fraud, $500,000 for her claim of tortious interference with an employment relationship, and $250,000 for her claim of negligent misrepresentation.

A hospital spokesperson said Ascension St Vincent is pursuing an appeal, and that it looks “forward to the opportunity to bring this matter before the Indiana Court of Appeals in June.”

In another case, South Dakota surgeon Linda Miller, MD, was awarded $1.1 million in 2017 after a federal jury found Huron Regional Medical Center breached her contract and violated her due process rights. Dr. Miller became the subject of a peer review at Huron Regional Medical Center when the hospital began analyzing some of her surgery outcomes.

Ken Barker, an attorney for Dr. Miller, said he feels it became evident at trial that the campaign to force Dr. Miller to either resign or lose her privileges was led by the lay board of directors of the hospital and upper-level administration at the hospital.

“They began the process by ordering an unprecedented 90-day review of her medical charts, looking for errors in the medical care she provided patients,” he said. “They could find nothing, so they did a second 90-day review, waiting for a patient’s ‘bad outcome.’ As any general surgeon will say, a ‘bad outcome’ is inevitable. And so it was. Upon that occurrence, they had a medical review committee review the patient’s chart and use it as an excuse to force her to reduce her privileges. Unbeknown to Dr. Miller, an external review had been conducted on another patient’s chart, in which the external review found her care above the standards and, in some measure, ‘exemplary.’ ”

Dr. Miller was eventually pressured to resign, according to her claim. Because of reports made to the NPDB by the medical center, including a patient complication that was allegedly falsified by the hospital, Dr. Miller said she was unable to find work as a general surgeon and went to work as a wound care doctor. At trial, jurors awarded Dr. Miller $586,617 in lost wages, $343,640 for lost future earning capacity, and $250,000 for mental anguish. (The mental anguish award was subsequently struck by a district court.)

Attorneys for Huron Regional Medical Center argued the jury improperly awarded damages and requested a new trial, which was denied by an appeals court.

In the end, the evidence came to light and the jury’s verdict spoke loudly that the hospital had taken unfair advantage of Dr. Miller, Mr. Barker said. But he emphasized that such cases often end differently.

“There are a handful of cases in which physicians like Dr. Miller have challenged the system and won,” he said. “In most cases, however, it is a ‘David vs. Goliath’ scenario where the giant prevails.”

What to do if faced with malicious peer review

An important step when doctors encounter a peer review that they believe is malicious is to consult with an experienced attorney as early as possible, Dr. Huntoon said. “Not all attorneys who set themselves out to be health law attorneys necessarily have knowledge and expertise in sham peer review. And before such a thing happens, I always encourage physicians to read their medical staff bylaws. That’s where everything is set forth, [such as] the corrective action section that tells how peer review is to take place.”

Mr. Barker added that documentation is also key in the event of a potential malicious peer review.

“When a physician senses [the] administration has targeted them, they should start documenting their conversations and actions very carefully, and if possible, recruit another ‘observer’ who can provide a third-party perspective, if necessary,” Mr. Barker said.

Dr. Huntoon recently wrote an article with advice about preparedness and defense of sham peer reviews. The guidance includes that physicians educate themselves about the tactics used by some hospitals to conduct sham peer reviews and the factors that place doctors more at risk. Factors that may raise a doctor’s danger of being targeted include being in solo practice or a small group, being new on staff, or being an older physician approaching retirement as some bad-actor hospitals may view older physicians as being less likely to fight back, said Dr. Huntoon.

Doctors should also keep detailed records and a timeline in the event of a malicious peer review and insist that an independent court reporter record all peer review hearings, even if that means the physician has to pay for the reporter him or herself, according to the guidance. An independent record is invaluable should the physician ultimately issue a future legal challenge against the hospital.

Mr. Willner encourages physicians to call the Center for Peer Review Justice hotline at (504) 621-1670 or visit the website for help with peer review and NPDB issues.

As for Dr. Smith, his days are much quieter and slower today, compared with the active practice he was accustomed to for more than half his life. He misses the fast pace, the patients, and the work that always brought him great joy.

“I hope to get back to doing surgeries eventually,” he said. “I graduated medical school in 1972. Practicing surgery has been my whole life and my career. They have taken my identity and my livelihood away from me based on false numbers and false premises. I want it back.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiothoracic surgeon J. Marvin Smith III, MD, had always thrived on a busy practice schedule, often performing 20-30 surgeries a week. A practicing surgeon for more than 40 years, Dr. Smith said he had no plans to slow down anytime soon.

But Dr. Smith said his career was derailed when leaders at Methodist Healthcare System of San Antonio initiated a sudden peer review proceeding against him. The hospital system alleged certain surgeries performed by Dr. Smith had excessive mortality rates. When he proved the data inaccurate, Dr. Smith said administrators next claimed he was cognitively impaired and wasn’t safe to practice.

Dr. Smith has now been embroiled in a peer review dispute with the hospital system for more than 2 years and says the conflict has essentially forced him out of surgical practice. He believes the peer review was “malicious” and was really launched because of complaints he made about nurse staffing and other issues at the hospital.

“I think it is absolutely in bad faith and is disingenuous what they’ve told me along the way,” said Dr. Smith, 73. “It’s because I pointed out deficiencies in nursing care, and they want to get rid of me. It would be a lot easier for them if I had a contract and they could control me better. But the fact that I was independent, meant they had to resort to a malicious peer review to try and push me out.”

Dr. Smith had a peer review hearing with Methodist in March 2021, and in April, a panel found in Dr. Smith’s favor, according to Dr. Smith. The findings were sent to the hospital’s medical board for review, which issued a decision in early May.

Eric A. Pullen, an attorney for Dr. Smith, said he could not go into detail about the board’s decision for legal reasons, but that “the medical board’s decision did not completely resolve the matter, and Dr. Smith intends to exercise his procedural rights, which could include an appeal.”

Methodist Hospital Texsan and its parent company, Methodist Health System of San Antonio, did not respond to messages seeking comment about the case. Without hearing from the hospital system, its side is unknown and it is unclear if there is more to the story from Methodist’s view.

The problem is not new, but some experts, such as Lawrence Huntoon, MD, PhD, say the practice has become more common in recent years, particularly against independent doctors.

Dr. Huntoon believes there is a nationwide trend at many hospitals to get rid of independent physicians and replace them with employed doctors, he said.

However, because most sham peer reviews go on behind closed doors, there are no data to pinpoint its prevalence or measure its growth.

“Independent physicians are basically being purged from medical staffs across the United States,” said Dr. Huntoon, who is chair of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons’ Committee to Combat Sham Peer Review. “The hospitals want more control over how physicians practice and who they refer to, and they do that by having employees.”

Anthony P. Weiss, MD, MBA, chief medical officer for Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center said it has not been his experience that independent physicians are being targeted in such a way. Dr. Weiss responded to an inquiry sent to the American Hospital Association for this story.

“As the authority for peer review rests with the organized medical staff (i.e., physicians), and not formally with the hospital per se, the peer review lever is not typically available as a management tool for hospital administration,” said Dr. Weiss, who is a former member of the AHA’s Committee on Clinical Leadership, but who was speaking on behalf of himself.

A spokesman for the AHA said the organization stands behinds Dr. Weiss’ comments.

Peer review remains a foundational aspect of overseeing the safety and appropriateness of healthcare provided by physicians, Dr. Weiss said. Peer review likely varies from hospital to hospital, he added, although the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act provides some level of guidance as does the American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics (section 9.4.1).

“In essence, both require that the evaluation be conducted in good faith with the intention to improve care, by physicians with adequate training and knowledge, using a process that is fair and inclusive of the physician under review,” he said. “I believe that most medical staffs abide by these ethical principles, but we have little data to confirm this supposition.”

Did hospital target doc for being vocal?

When members of Methodist’s medical staff first approached Dr. Smith with concerns about his surgery outcomes in November 2018, the physician says he was surprised, but that he was open to an assessment.

“They came to me and said they thought my numbers were bad, and I said: ‘Well my gosh, I certainly don’t want that to be the case. I need to see what numbers you are talking about,’ ” Dr. Smith recalled. “I’ve been president of the Bexar County Medical Society; I’ve been involved with standards and ethics for the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Quality health care means a whole lot to me.”

The statistical information provided by hospital administrators indicated that Dr. Smith’s mortality rates for coronary artery surgery in 2018 were “excessive” and that his rates for aortic surgery were “unacceptable,” according to a lawsuit Dr. Smith filed against the hospital system. Dr. Smith, who is double boarded with the American Board of Surgery and the American Board of Thoracic Surgery, said his outcomes had never come into question in the past. Dr. Smith said the timing was suspicious to him, however, considering he had recently raised concerns with the hospital through letters about nursing performance, staffing, and compensation.

A peer review investigation was initiated. In the meantime, Dr. Smith agreed to intensivist consults on his postoperative patients and consults with the hospital’s “Heart Team” on all preoperative cardiac, valve, and aortic cases. A vocal critic of the Heart Team, Dr. Smith had long contended the entity provided no meaningful benefit to his patients in most cases and, rather, increased hospital stays and raised medical expenses. Despite his agreement, Dr. Smith was later asked to voluntarily stop performing surgeries at the hospital.

“I agreed, convinced that we’d get this all settled,” he said.

Another report issued by the hospital in 2019 also indicated elevated mortality rates associated with some of Smith’s surgeries, although the document differed from the first report, according to the lawsuit. Dr. Smith says he was ignored when he pointed out problems with the data, including a lack of appropriate risk stratification in the report, departure from Society of Thoracic Surgeons data rules, and improper inclusion of his cases in the denominator of the ratio when a comparison was made of his outcomes with those hospitalwide. A subsequent report from Methodist in March 2019 indicated Dr. Smith’s surgery outcomes were “within the expected parameters of performance,” according to court documents.

The surgery accusations were dropped, but the peer review proceeding against Dr. Smith wasn’t over. The hospital next requested that Dr. Smith undergo a competency evaluation.

“When they realized the data was bad, they then changed their argument in the peer review proceeding and essentially started to argue that Dr. Smith had some sort of cognitive disability that prevented him from continuing to practice,” said Mr. Pullen. “The way I look at it, when the initial basis for the peer review was proven false, the hospital found something else and some other reason to try to keep Dr. Smith from practicing.”

Thus began a lengthy disagreement about which entity would conduct the evaluation, who would pay, and the type of acceptable assessment. An evaluation by the hospital’s preferred organization resulted in a finding of mild cognitive impairment, Dr. Smith said. He hired his own experts who conducted separate evaluations, finding no impairment and no basis for the former evaluation’s conclusion.

“Literally, the determinant as to whether I was normal or below normal on their test was one point, which was associated with a finding that I didn’t draw a clock correctly,” Dr. Smith claimed. “The reviewer said my minute hand was a little too short and docked me a point. It was purely subjective. To me, the gold standard of whether you are learned in thoracic surgery is the American Board of Thoracic Surgery’s test. The board’s test shows my cognitive ability is entirely in keeping with my practice. That contrasts with the one point off I got for drawing a clock wrong in somebody’s estimation.”

Conflict leads to legal case

In September 2020, Dr. Smith filed a lawsuit against Methodist Healthcare System of San Antonio, alleging business disparagement by Methodist for allegedly publishing false and disparaging information about Dr. Smith and tortious interference with business relations. The latter claim stems from Methodist refusing to provide documents to other hospitals about the status of Dr. Smith’s privileges at Methodist, Mr. Pullen said.

Because Methodist refused to confirm his status, the renewal process for Baptist Health System could not be completed and Dr. Smith lost his privileges at Baptist Health System facilities, according to the lawsuit.

Notably, Dr. Smith’s legal challenge also asks the court to take a stance against alleged amendments by Methodist to its Unified Medical Staff Bylaws. The hospital allegedly proposed changes that would prevent physicians from seeking legal action against the hospital for malicious peer review, according to Dr. Smith’s lawsuit.

The amendments would make the peer review process itself the “sole and exclusive remedy with respect to any action or recommendation taken at the hospital affecting medical staff appointment and/or clinical privileges,” according to an excerpt of the proposed amendments included in Dr. Smith’s lawsuit. In addition, the changes would hold practitioners liable for lost revenues if the doctor initiates “any type of legal action challenging credentialing, privileging, or other medical peer review or professional review activity,” according to the lawsuit.

Dr. Smith’s lawsuit seeks a declaration that the proposed amendments to the bylaws are “void as against public policy,” and a declaration that the proposed amendments to the bylaws cannot take away physicians’ statutory right to bring litigation against Methodist for malicious peer review.

“The proposed amendments have a tendency to and will injure the public good,” Dr. Smith argued in the lawsuit. “The proposed amendments allow Methodist to act with malice and in bad faith in conducting peer review proceedings and face no legal repercussions.”

Regardless of the final outcome of the peer review proceeding, Mr. Pullen said the harm Dr. Smith has already endured cannot be reversed.

“Even if comes out in his favor, the damage is already done,” he said. “It will not remedy the damage Dr. Smith has incurred.”

Fighting sham peer review is difficult

Battling a malicious peer review has long been an uphill battle for physicians, according to Dr. Huntoon. That’s because the Health Care Quality Improvement Act (HCQIA), a federal law passed in 1986, provides near absolute immunity to hospitals and peer reviewers in legal disputes.

The HCQIA was created by Congress to extend immunity to good-faith peer review of doctors and to increase overall participation in peer review by removing fear of litigation. However, the act has also enabled abuse of peer review by shielding bad-faith reviewers from accountability, said Dr. Huntoon.

“The Health Care Quality Improvement Act presumes that what the hospital did was warranted and reasonable and shifts the burden to the physician to prove his innocence by a preponderance of evidence,” he said. “That’s an entirely foreign concept to most people who think a person should be considered innocent until proven guilty. Here, it’s the exact opposite.”

The HCQIA has been challenged numerous times over the years and tested at the appellate level, but continues to survive and remain settled law, added Richard B. Willner, DPM, founder and director of the Center for Peer Review Justice, which assists and counsels physicians about sham peer review.

In 2011, former Rep. Joe Heck, DO, (R-Nev.) introduced a bill that would have amended the HCQIA to prohibit a professional review entity from submitting a report to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) while the doctor was still under investigation and before the doctor was afforded adequate notice and a hearing. Although the measure had 16 cosponsors and plenty of support from the physician community, it failed.

In addition to a heavy legal burden, physicians who experience malicious peer reviews also face ramifications from being reported to the NPDB. Peer review organizations are required to report certain negative actions or findings to the NPDB.

“A databank entry is a scarlet letter on your forehead,” Dr. Willner said. “The rules at a lot of institutions are not to take anyone who has been databanked, rightfully or wrongfully. And what is the evidence necessary to databank you? None. There’s no evidence needed to databank somebody.”

Despite the bleak landscape, experts say progress has been made on a case-by-case basis by physicians who have succeeded in fighting back against questionable peer reviews in recent years.

In January 2020, Indiana ob.gyn. Rebecca Denman, MD, prevailed in her defamation lawsuit against St Vincent Carmel Hospital and St Vincent Carmel Medical Group, winning $4.75 million in damages. Dr. Denman alleged administrators failed to conduct a proper peer review investigation after a false allegation by a nurse that she was under the influence while on the job.

Indianapolis attorney Kathleen A. DeLaney, who represented Dr. Denman, said hospital leaders misled Dr. Denman into believing a peer review had occurred when no formal peer review hearing or proceeding took place.

“The CMO of the medical group claimed that he performed a peer review ‘screening,’ but he never informed the other members of the peer review executive committee of the matter until after he had placed Dr. Denman on administrative leave,” Ms. DeLaney said. “He also neglected to tell the peer review executive committee that the substance abuse policy had not been followed, or that Dr. Denman had not been tested for alcohol use – due to the 12-hour delay in report.”

Dr. Denman was ultimately required to undergo an alcohol abuse evaluation, enter a treatment program, and sign a 5-year monitoring contract with the Indiana State Medical Association as a condition of her employment, according to the lawsuit. She claimed repercussions from the false allegation resulted in lost compensation, out-of-pocket expenses, emotional distress, and damage to her professional reputation.

She sued the hospital in July 2018, alleging fraud, defamation, tortious interference with an employment relationship, and negligent misrepresentation. After a 4-day trial, jurors found in her favor, awarding Dr. Denman $2 million for her defamation claims, $2 million for her claims of fraud and constructive fraud, $500,000 for her claim of tortious interference with an employment relationship, and $250,000 for her claim of negligent misrepresentation.

A hospital spokesperson said Ascension St Vincent is pursuing an appeal, and that it looks “forward to the opportunity to bring this matter before the Indiana Court of Appeals in June.”

In another case, South Dakota surgeon Linda Miller, MD, was awarded $1.1 million in 2017 after a federal jury found Huron Regional Medical Center breached her contract and violated her due process rights. Dr. Miller became the subject of a peer review at Huron Regional Medical Center when the hospital began analyzing some of her surgery outcomes.

Ken Barker, an attorney for Dr. Miller, said he feels it became evident at trial that the campaign to force Dr. Miller to either resign or lose her privileges was led by the lay board of directors of the hospital and upper-level administration at the hospital.

“They began the process by ordering an unprecedented 90-day review of her medical charts, looking for errors in the medical care she provided patients,” he said. “They could find nothing, so they did a second 90-day review, waiting for a patient’s ‘bad outcome.’ As any general surgeon will say, a ‘bad outcome’ is inevitable. And so it was. Upon that occurrence, they had a medical review committee review the patient’s chart and use it as an excuse to force her to reduce her privileges. Unbeknown to Dr. Miller, an external review had been conducted on another patient’s chart, in which the external review found her care above the standards and, in some measure, ‘exemplary.’ ”

Dr. Miller was eventually pressured to resign, according to her claim. Because of reports made to the NPDB by the medical center, including a patient complication that was allegedly falsified by the hospital, Dr. Miller said she was unable to find work as a general surgeon and went to work as a wound care doctor. At trial, jurors awarded Dr. Miller $586,617 in lost wages, $343,640 for lost future earning capacity, and $250,000 for mental anguish. (The mental anguish award was subsequently struck by a district court.)

Attorneys for Huron Regional Medical Center argued the jury improperly awarded damages and requested a new trial, which was denied by an appeals court.

In the end, the evidence came to light and the jury’s verdict spoke loudly that the hospital had taken unfair advantage of Dr. Miller, Mr. Barker said. But he emphasized that such cases often end differently.

“There are a handful of cases in which physicians like Dr. Miller have challenged the system and won,” he said. “In most cases, however, it is a ‘David vs. Goliath’ scenario where the giant prevails.”

What to do if faced with malicious peer review

An important step when doctors encounter a peer review that they believe is malicious is to consult with an experienced attorney as early as possible, Dr. Huntoon said. “Not all attorneys who set themselves out to be health law attorneys necessarily have knowledge and expertise in sham peer review. And before such a thing happens, I always encourage physicians to read their medical staff bylaws. That’s where everything is set forth, [such as] the corrective action section that tells how peer review is to take place.”

Mr. Barker added that documentation is also key in the event of a potential malicious peer review.

“When a physician senses [the] administration has targeted them, they should start documenting their conversations and actions very carefully, and if possible, recruit another ‘observer’ who can provide a third-party perspective, if necessary,” Mr. Barker said.

Dr. Huntoon recently wrote an article with advice about preparedness and defense of sham peer reviews. The guidance includes that physicians educate themselves about the tactics used by some hospitals to conduct sham peer reviews and the factors that place doctors more at risk. Factors that may raise a doctor’s danger of being targeted include being in solo practice or a small group, being new on staff, or being an older physician approaching retirement as some bad-actor hospitals may view older physicians as being less likely to fight back, said Dr. Huntoon.

Doctors should also keep detailed records and a timeline in the event of a malicious peer review and insist that an independent court reporter record all peer review hearings, even if that means the physician has to pay for the reporter him or herself, according to the guidance. An independent record is invaluable should the physician ultimately issue a future legal challenge against the hospital.

Mr. Willner encourages physicians to call the Center for Peer Review Justice hotline at (504) 621-1670 or visit the website for help with peer review and NPDB issues.

As for Dr. Smith, his days are much quieter and slower today, compared with the active practice he was accustomed to for more than half his life. He misses the fast pace, the patients, and the work that always brought him great joy.

“I hope to get back to doing surgeries eventually,” he said. “I graduated medical school in 1972. Practicing surgery has been my whole life and my career. They have taken my identity and my livelihood away from me based on false numbers and false premises. I want it back.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA and power morcellation, gel for vaginal odor, and an intrauterine electrosurgery system

FDA guidance for power morcellation

“The FDA has granted marketing authorization for one containment system and continues to encourage innovation in this area” said the report. Olympus’ Pneumoliner is the only FDA cleared containment device to provide a laparoscopic option for appropriately identified patients undergoing myomectomy and hysterectomy. The containment system is sold with Olympus’ PK Morcellator, but the company says that it has made the Pneumoliner available to physicians choosing an alternate to the PK Morcellator, provided that there is device compatibility. The Pneumoliner “reduces the spread of benign tissue into the abdominal cavity, in which pathologies, like fibroids, may regrow when tissue or cells are inadvertently left behind,” according to Olympus.

Vaginal odor elimination gel

The gel is sold in 7 single-day applications, with a single tube used per day at bedtime to eliminate unwanted odor. To maintain freshness and comfort, a single tube of Relactagel can be used for 2 to 3 days after a woman’s menstrual cycle, says Kora Healthcare. The company warns that mild irritation can occur with product use during fungal infections or when small tears are present in the vaginal tissue and that use should be discontinued if irritation occurs. In addition, if trying to become pregnant Relatagel should not be used, advises Kora Healthcare, although the gel is not a contraceptive.

Intrauterine electrosurgery system

FDA guidance for power morcellation

“The FDA has granted marketing authorization for one containment system and continues to encourage innovation in this area” said the report. Olympus’ Pneumoliner is the only FDA cleared containment device to provide a laparoscopic option for appropriately identified patients undergoing myomectomy and hysterectomy. The containment system is sold with Olympus’ PK Morcellator, but the company says that it has made the Pneumoliner available to physicians choosing an alternate to the PK Morcellator, provided that there is device compatibility. The Pneumoliner “reduces the spread of benign tissue into the abdominal cavity, in which pathologies, like fibroids, may regrow when tissue or cells are inadvertently left behind,” according to Olympus.

Vaginal odor elimination gel

The gel is sold in 7 single-day applications, with a single tube used per day at bedtime to eliminate unwanted odor. To maintain freshness and comfort, a single tube of Relactagel can be used for 2 to 3 days after a woman’s menstrual cycle, says Kora Healthcare. The company warns that mild irritation can occur with product use during fungal infections or when small tears are present in the vaginal tissue and that use should be discontinued if irritation occurs. In addition, if trying to become pregnant Relatagel should not be used, advises Kora Healthcare, although the gel is not a contraceptive.

Intrauterine electrosurgery system

FDA guidance for power morcellation

“The FDA has granted marketing authorization for one containment system and continues to encourage innovation in this area” said the report. Olympus’ Pneumoliner is the only FDA cleared containment device to provide a laparoscopic option for appropriately identified patients undergoing myomectomy and hysterectomy. The containment system is sold with Olympus’ PK Morcellator, but the company says that it has made the Pneumoliner available to physicians choosing an alternate to the PK Morcellator, provided that there is device compatibility. The Pneumoliner “reduces the spread of benign tissue into the abdominal cavity, in which pathologies, like fibroids, may regrow when tissue or cells are inadvertently left behind,” according to Olympus.

Vaginal odor elimination gel

The gel is sold in 7 single-day applications, with a single tube used per day at bedtime to eliminate unwanted odor. To maintain freshness and comfort, a single tube of Relactagel can be used for 2 to 3 days after a woman’s menstrual cycle, says Kora Healthcare. The company warns that mild irritation can occur with product use during fungal infections or when small tears are present in the vaginal tissue and that use should be discontinued if irritation occurs. In addition, if trying to become pregnant Relatagel should not be used, advises Kora Healthcare, although the gel is not a contraceptive.

Intrauterine electrosurgery system

Communication Strategies in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Methods, Time Savings, and Perceived Patient Satisfaction

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

Results

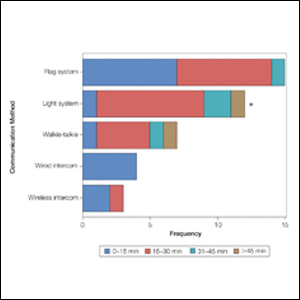

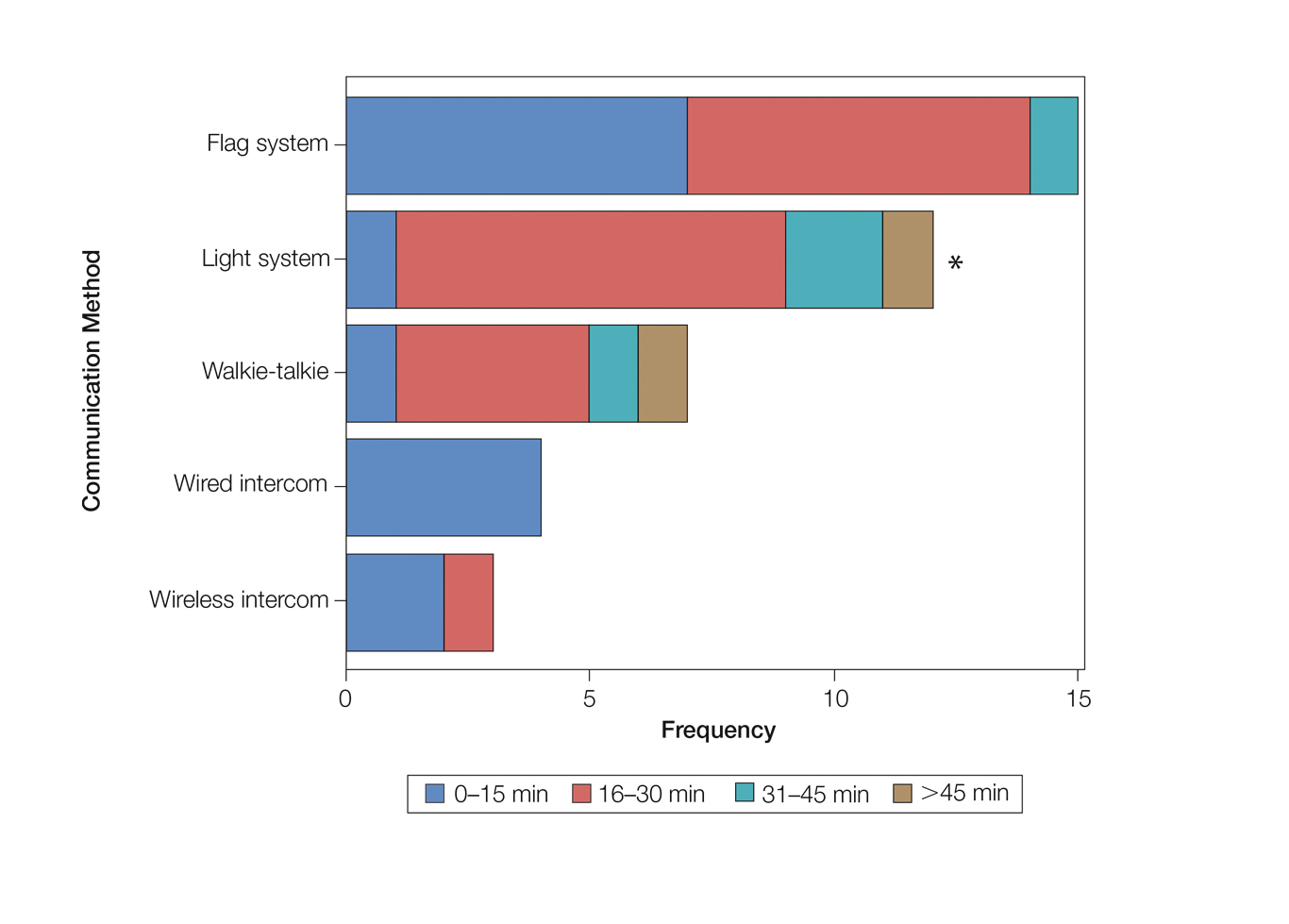

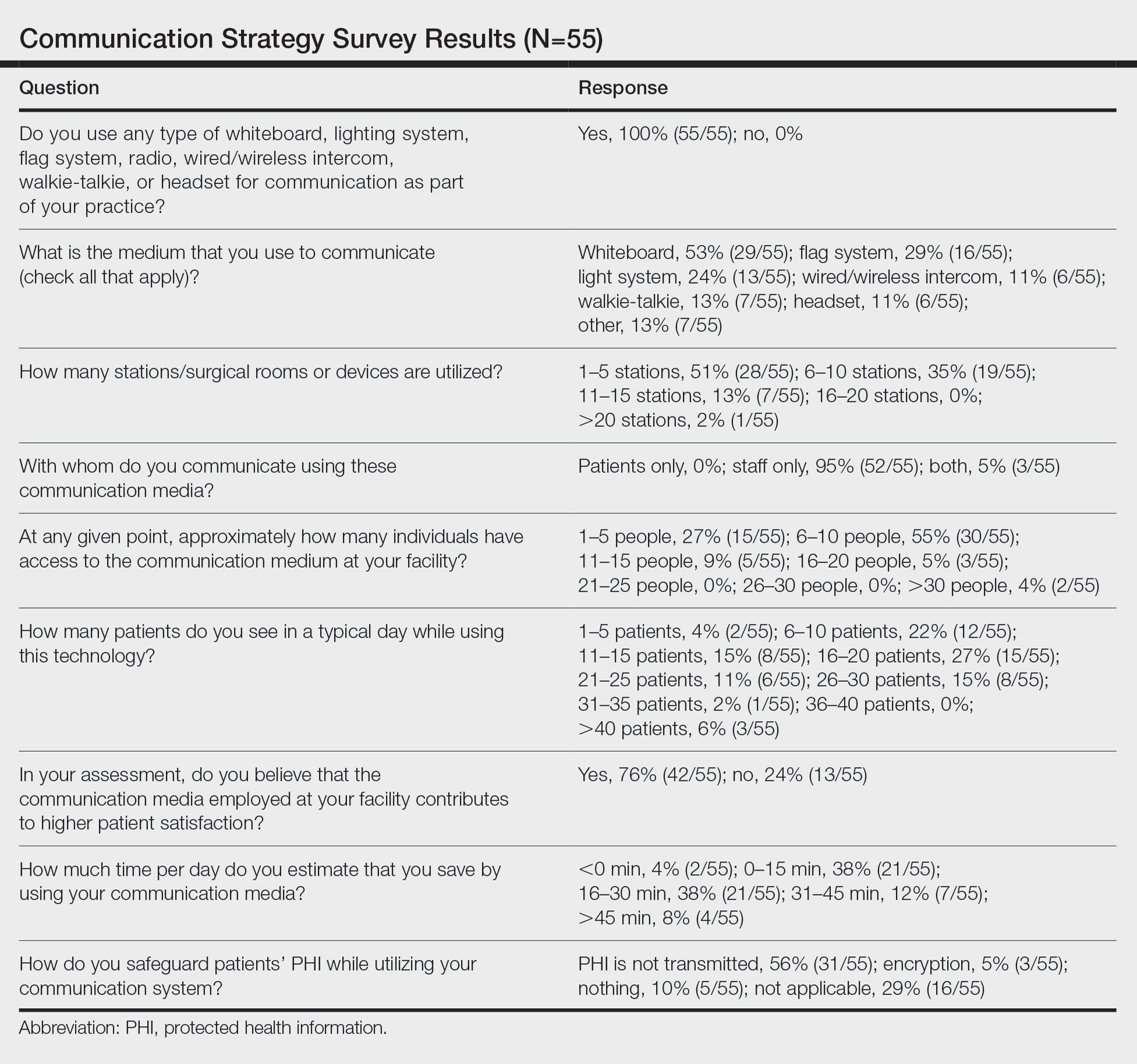

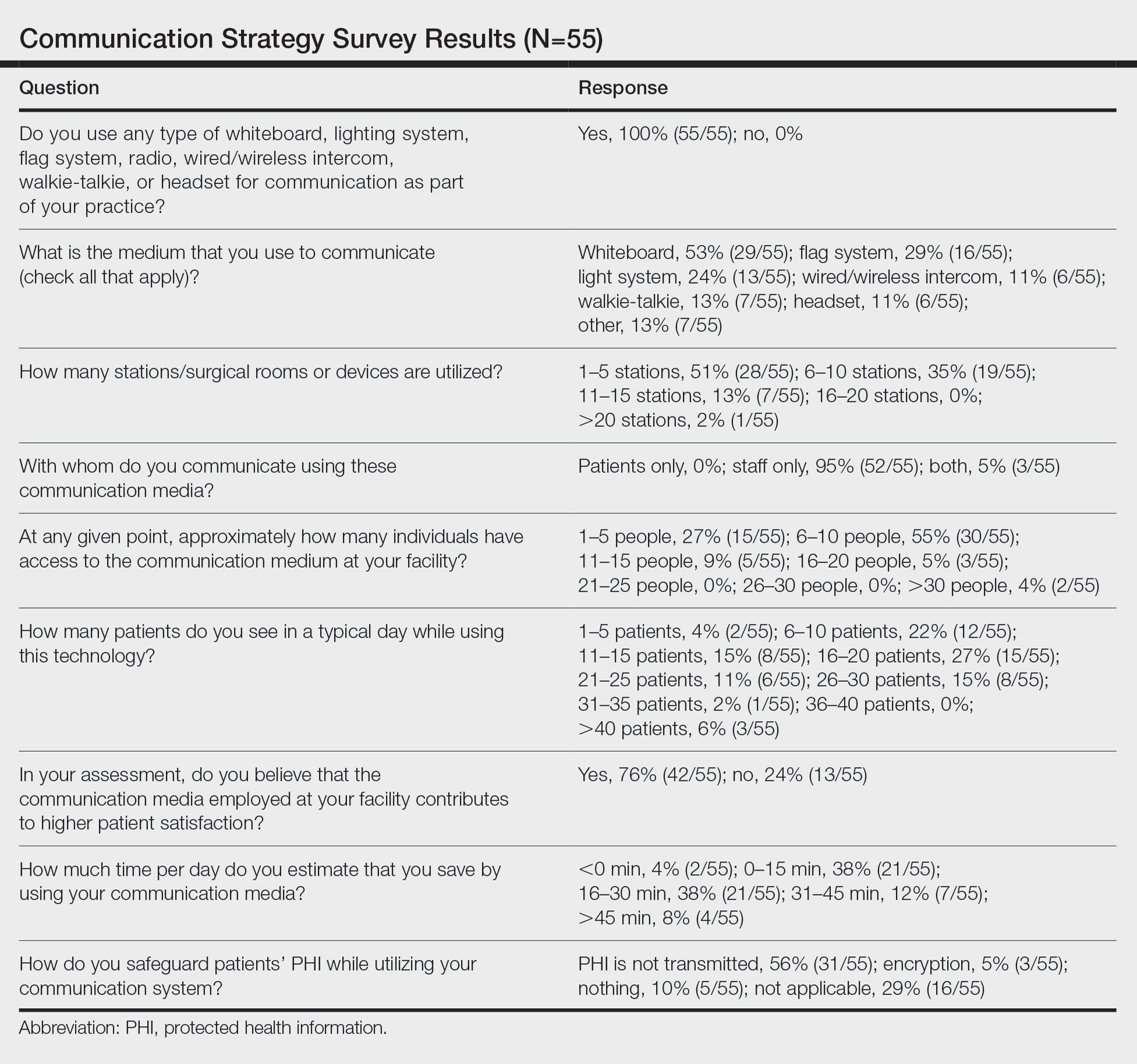

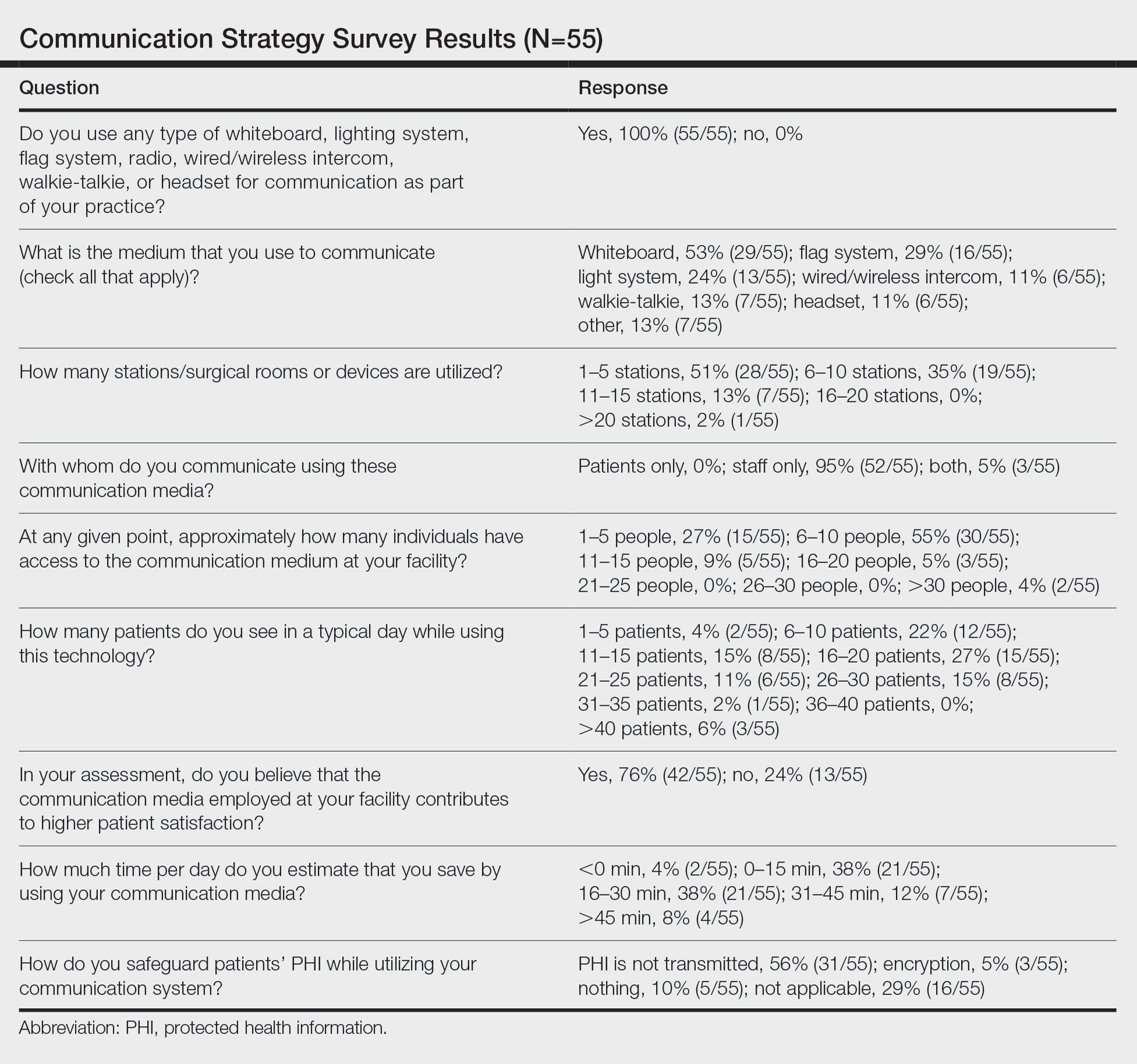

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

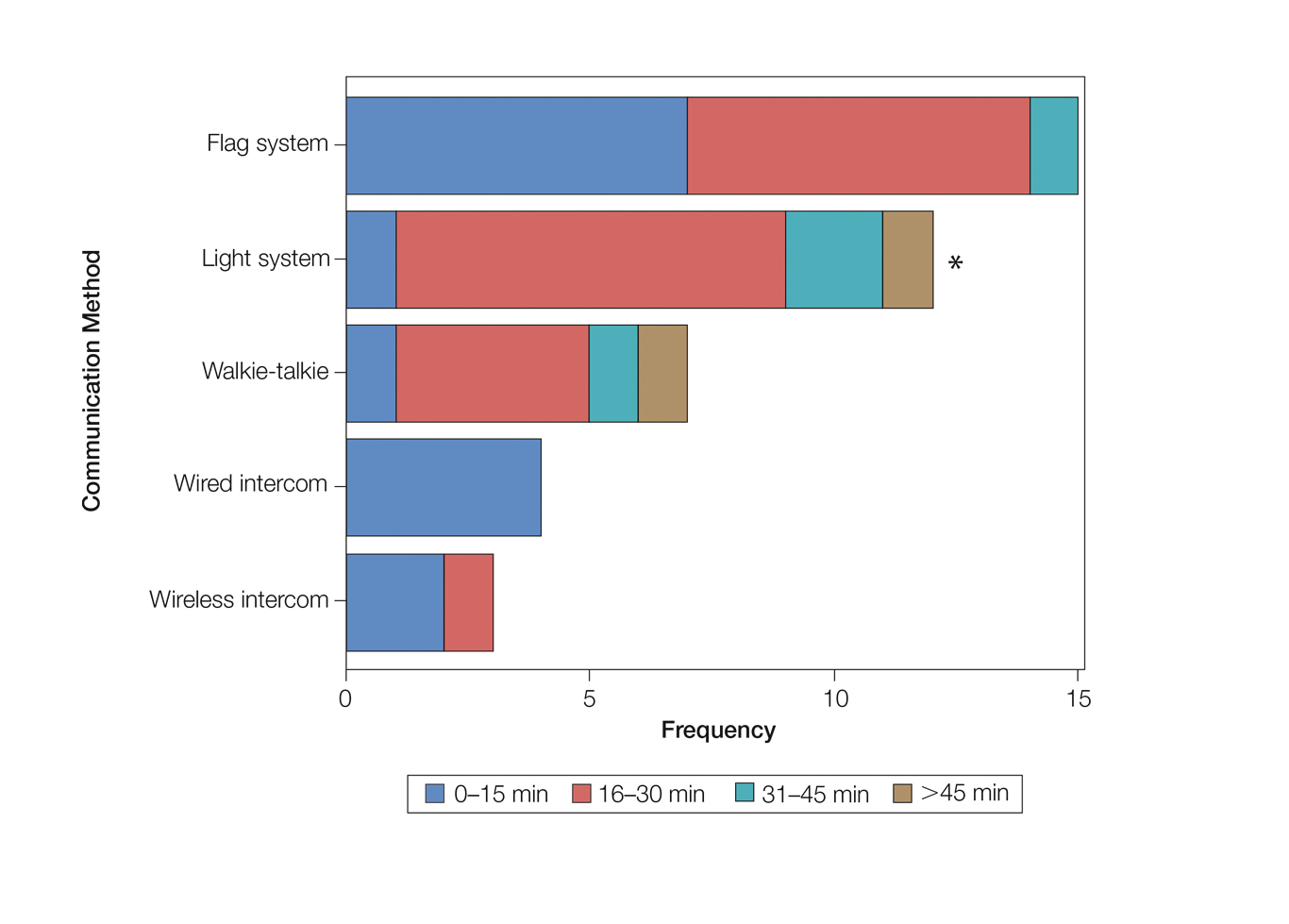

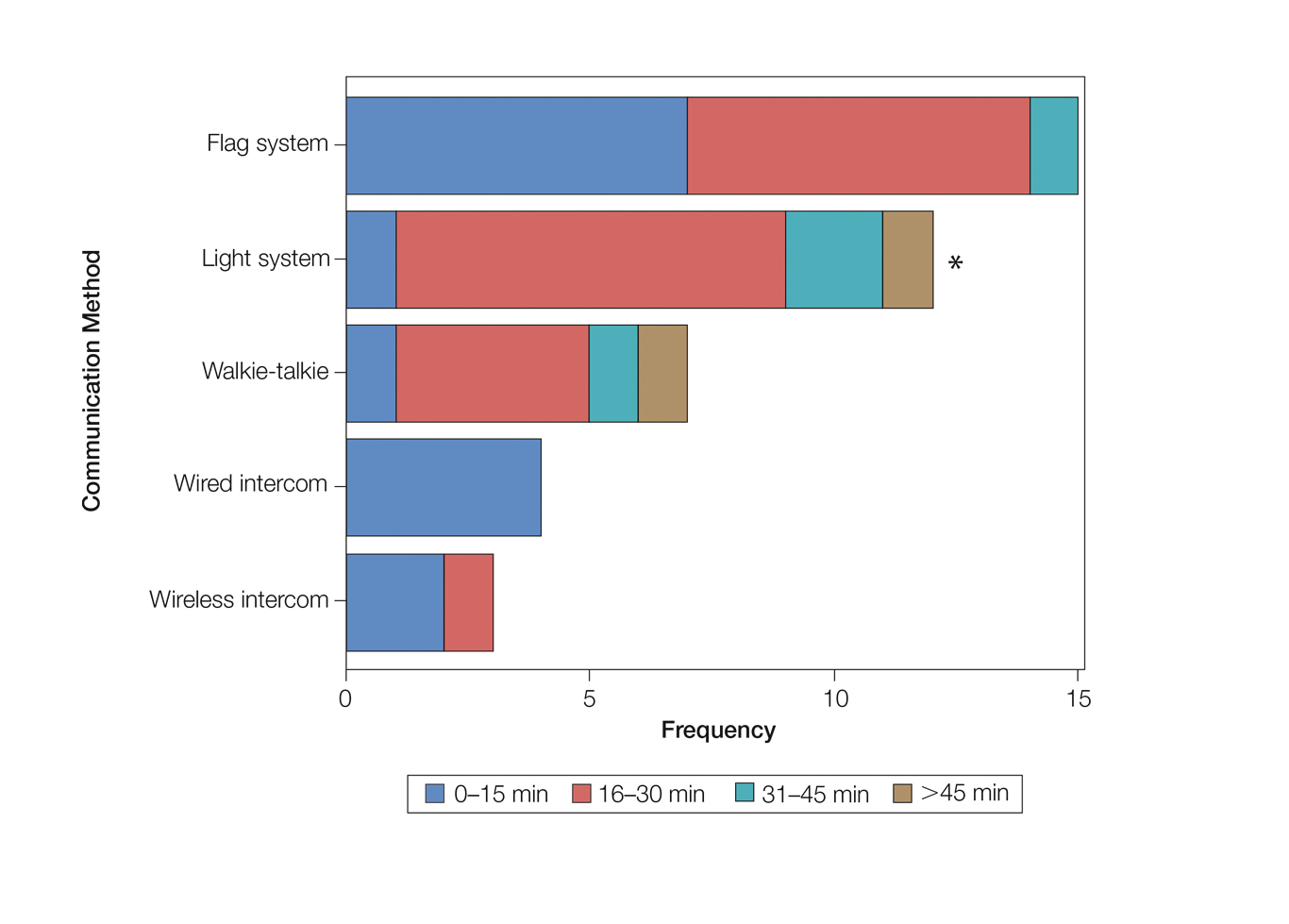

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

Results