User login

Flattening the curve: Viral graphic shows COVID-19 containment needs

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

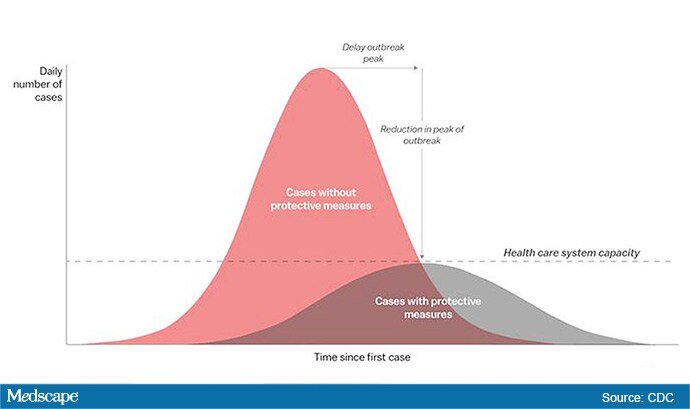

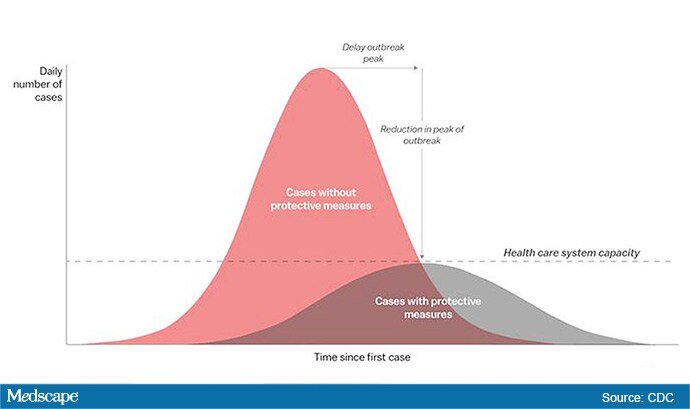

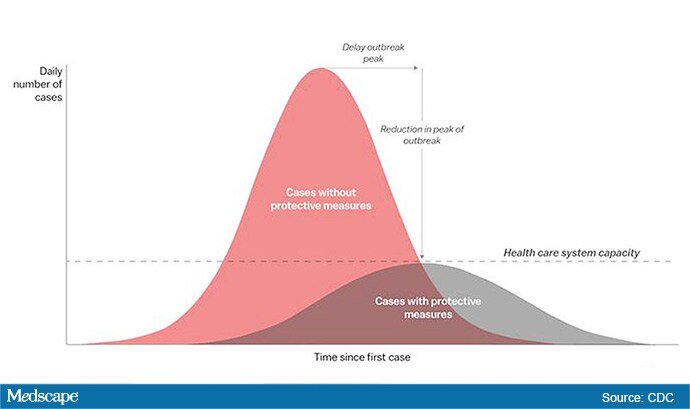

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

So you have a COVID-19 patient: How do you treat them?

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Clinicians are working out how to manage patients with or suspected of having COVID-19.

“Over the past couple of weeks, we’ve been preparing for the oncoming onslaught of patients,” said Lillian Wu, MD, of the HealthPoint network in the Seattle area of greater King County and president elect of the Washington Academy of Family Physicians.

Step One: Triage

The first step, Wu says, is careful triage.

When patients call one of the 17 clinics in the HealthPoint system, nurses gauge how sick they are. High fever? Shortness of breath? Do they have a chronic illness, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or a lung condition, that increases risk for infection and complications?

“If a patient has mild symptoms, we ask them to stay home or to check back in 24 hours, or we’ll reach out to them. For moderate symptoms, we ask them to come in, and [we] clearly mark on the schedule that it is a respiratory patient, who will be sent to a separate area. If the patient is severe, we don’t even see them and send them directly to the hospital to the ER,” Wu told Medscape Medical News.

These categories parallel the World Health Organization’s designations of uncomplicated illness, mild pneumonia, severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and septic shock. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises case by case regarding decisions as to outpatient or inpatient assignment.

“Patients who pass the initial phone triage are given masks, separated, and sent to different parts of the clinic or are required to wait in their cars until it’s time to be seen,” Wu said.

Step 2: Hospital Arrival

Once at the hospital, the CDC’s interim guidance kicks in.

“Any patient with fever, cough, and shortness of breath presenting with a history of travel to countries with high ongoing transmission or a credible history of exposure should be promptly evaluated for COVID-19,” said Raghavendra Tirupathi, MD, medical director, Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV; chair in infection prevention, Summit Health; and clinical assistant professor of medicine, Penn State School of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“We recommend obtaining baseline CBC with differential, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and procalcitonin. Clues for COVID-19 include leukopenia, seen in 30% to 45% of patients, and lymphocytopenia, seen in 85% of the patients in the case series from China,” Tirupathi said. He uses a respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction panel to rule out other pathogens.

Wu concurs. “This is the one time we are grateful when someone tests positive for the flu! If flu is negative and other common respiratory infections are negative, then we do a COVID-19 test,” she said.

But test results may be delayed. “At the University of Washington, it takes 8 hours, but commercial labs take up to 4 days,” Wu said. All patients with respiratory symptoms are treated as persons under investigation, for whom isolation precautions are required. In addition, for these patients, use of personal protective equipment by caregivers is required.

For suspected pneumonia, the American College of Radiography recommends chest CT to identify peripheral basal ground-glass opacities characteristic of COVID-19.

However, diagnosis should be based on detection of SARS-CoV-2, because chest images for COVID-19 are nonspecific – associated signs can also be seen in H1N1 influenza, SARS, and MERS.

Step 3: Supportive Care

Once a patient is admitted, supportive care entails “maintaining fluid status and nutrition and supporting physiological functions until we heal. It’s treating complications and organ support, whether that means providing supplementary oxygen all the way to ventilator support, and just waiting it out. If a patient progresses to acute respiratory distress syndrome, it becomes tougher,” said David Liebers, MD, chief medical officer and an infectious disease specialist at Ellis Medicine in Schenectady, New York.

Efforts are ramping up to develop therapeutics. Remdesivir, an investigational antiviral drug developed to treat Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fevers, shows activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.

Remdesivir has been used in a few patients on a compassionate-use basis outside of a clinical trial setting. “It’s a nucleotide analogue, and like other drugs of that class, it disrupts nucleic acid production. Some data suggest that it might have some efficacy,” Liebers said.

Antibiotics are reserved for patients suspected of having concomitant bacterial or fungal infections. Liebers said clinicians should be alerted to “the big three” signs of secondary infection – fever, elevated white blood cell count, and lactic acidosis. Immunosuppressed patients are at elevated risk for secondary infection.

Step 4: Managing Complications

Patients do die of COVID-19, mostly through an inability to ventilate, even when supported with oxygen, Liebers told Medscape Medical News. (According to Tirupathi, “The studies from China indicate that from 6%-10% of patients needed ventilators.”)

Liebers continued, “Others may develop sepsis or a syndrome of multisystem organ failure with renal and endothelial collapse, making it difficult to maintain blood pressure. Like with so many pathologies, it is a vicious circle in which everything gets overworked. Off-and-on treatments can sometimes break the cycle: supplementary oxygen, giving red blood cells, dialysis. We support those functions while waiting for healing to occur.”

A facility’s airborne-infection isolation rooms may become filled to capacity, but that isn’t critical, Liebers said. “Airborne precautions are standard to contain measles, tuberculosis, chickenpox, and herpes zoster, in which very small particles spread in the air,” he said.

Consensus is growing that SARS-CoV-2 spreads in large droplets, he added. Private rooms and closed doors may suffice.

Step 5: Discharge

Liebers said that as of now, the million-dollar question regards criteria for discharge.

Patients who clinically improve are sent home with instructions to remain in isolation. They may be tested again for virus before or after discharge.

Liebers and Wu pointed to the experience at EvergreenHealth Medical Center, in Kirkland, Washington, as guidance from the trenches. “They’re the ones who are learning firsthand and passing the experience along to everyone else,” Wu said.

“The situation is unprecedented,” said Liebers, who, like many others, has barely slept these past weeks. “We’re swimming in murky water right now.”

The epidemic in the United States is still months from peaking, Wu emphasized. “There is no vaccine, and many cases are subclinical. COVID-19 has to spread through the country before it infects a critical mass of people who will develop immunity. It’s too late to contain.”

Added Liebers, “It’s a constantly changing situation, and we are still being surprised – not that this wasn’t predicted.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Clinicians are working out how to manage patients with or suspected of having COVID-19.

“Over the past couple of weeks, we’ve been preparing for the oncoming onslaught of patients,” said Lillian Wu, MD, of the HealthPoint network in the Seattle area of greater King County and president elect of the Washington Academy of Family Physicians.

Step One: Triage

The first step, Wu says, is careful triage.

When patients call one of the 17 clinics in the HealthPoint system, nurses gauge how sick they are. High fever? Shortness of breath? Do they have a chronic illness, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or a lung condition, that increases risk for infection and complications?

“If a patient has mild symptoms, we ask them to stay home or to check back in 24 hours, or we’ll reach out to them. For moderate symptoms, we ask them to come in, and [we] clearly mark on the schedule that it is a respiratory patient, who will be sent to a separate area. If the patient is severe, we don’t even see them and send them directly to the hospital to the ER,” Wu told Medscape Medical News.

These categories parallel the World Health Organization’s designations of uncomplicated illness, mild pneumonia, severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and septic shock. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises case by case regarding decisions as to outpatient or inpatient assignment.

“Patients who pass the initial phone triage are given masks, separated, and sent to different parts of the clinic or are required to wait in their cars until it’s time to be seen,” Wu said.

Step 2: Hospital Arrival

Once at the hospital, the CDC’s interim guidance kicks in.

“Any patient with fever, cough, and shortness of breath presenting with a history of travel to countries with high ongoing transmission or a credible history of exposure should be promptly evaluated for COVID-19,” said Raghavendra Tirupathi, MD, medical director, Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV; chair in infection prevention, Summit Health; and clinical assistant professor of medicine, Penn State School of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“We recommend obtaining baseline CBC with differential, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and procalcitonin. Clues for COVID-19 include leukopenia, seen in 30% to 45% of patients, and lymphocytopenia, seen in 85% of the patients in the case series from China,” Tirupathi said. He uses a respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction panel to rule out other pathogens.

Wu concurs. “This is the one time we are grateful when someone tests positive for the flu! If flu is negative and other common respiratory infections are negative, then we do a COVID-19 test,” she said.

But test results may be delayed. “At the University of Washington, it takes 8 hours, but commercial labs take up to 4 days,” Wu said. All patients with respiratory symptoms are treated as persons under investigation, for whom isolation precautions are required. In addition, for these patients, use of personal protective equipment by caregivers is required.

For suspected pneumonia, the American College of Radiography recommends chest CT to identify peripheral basal ground-glass opacities characteristic of COVID-19.

However, diagnosis should be based on detection of SARS-CoV-2, because chest images for COVID-19 are nonspecific – associated signs can also be seen in H1N1 influenza, SARS, and MERS.

Step 3: Supportive Care

Once a patient is admitted, supportive care entails “maintaining fluid status and nutrition and supporting physiological functions until we heal. It’s treating complications and organ support, whether that means providing supplementary oxygen all the way to ventilator support, and just waiting it out. If a patient progresses to acute respiratory distress syndrome, it becomes tougher,” said David Liebers, MD, chief medical officer and an infectious disease specialist at Ellis Medicine in Schenectady, New York.

Efforts are ramping up to develop therapeutics. Remdesivir, an investigational antiviral drug developed to treat Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fevers, shows activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.

Remdesivir has been used in a few patients on a compassionate-use basis outside of a clinical trial setting. “It’s a nucleotide analogue, and like other drugs of that class, it disrupts nucleic acid production. Some data suggest that it might have some efficacy,” Liebers said.

Antibiotics are reserved for patients suspected of having concomitant bacterial or fungal infections. Liebers said clinicians should be alerted to “the big three” signs of secondary infection – fever, elevated white blood cell count, and lactic acidosis. Immunosuppressed patients are at elevated risk for secondary infection.

Step 4: Managing Complications

Patients do die of COVID-19, mostly through an inability to ventilate, even when supported with oxygen, Liebers told Medscape Medical News. (According to Tirupathi, “The studies from China indicate that from 6%-10% of patients needed ventilators.”)

Liebers continued, “Others may develop sepsis or a syndrome of multisystem organ failure with renal and endothelial collapse, making it difficult to maintain blood pressure. Like with so many pathologies, it is a vicious circle in which everything gets overworked. Off-and-on treatments can sometimes break the cycle: supplementary oxygen, giving red blood cells, dialysis. We support those functions while waiting for healing to occur.”

A facility’s airborne-infection isolation rooms may become filled to capacity, but that isn’t critical, Liebers said. “Airborne precautions are standard to contain measles, tuberculosis, chickenpox, and herpes zoster, in which very small particles spread in the air,” he said.

Consensus is growing that SARS-CoV-2 spreads in large droplets, he added. Private rooms and closed doors may suffice.

Step 5: Discharge

Liebers said that as of now, the million-dollar question regards criteria for discharge.

Patients who clinically improve are sent home with instructions to remain in isolation. They may be tested again for virus before or after discharge.

Liebers and Wu pointed to the experience at EvergreenHealth Medical Center, in Kirkland, Washington, as guidance from the trenches. “They’re the ones who are learning firsthand and passing the experience along to everyone else,” Wu said.

“The situation is unprecedented,” said Liebers, who, like many others, has barely slept these past weeks. “We’re swimming in murky water right now.”

The epidemic in the United States is still months from peaking, Wu emphasized. “There is no vaccine, and many cases are subclinical. COVID-19 has to spread through the country before it infects a critical mass of people who will develop immunity. It’s too late to contain.”

Added Liebers, “It’s a constantly changing situation, and we are still being surprised – not that this wasn’t predicted.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Clinicians are working out how to manage patients with or suspected of having COVID-19.

“Over the past couple of weeks, we’ve been preparing for the oncoming onslaught of patients,” said Lillian Wu, MD, of the HealthPoint network in the Seattle area of greater King County and president elect of the Washington Academy of Family Physicians.

Step One: Triage

The first step, Wu says, is careful triage.

When patients call one of the 17 clinics in the HealthPoint system, nurses gauge how sick they are. High fever? Shortness of breath? Do they have a chronic illness, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or a lung condition, that increases risk for infection and complications?

“If a patient has mild symptoms, we ask them to stay home or to check back in 24 hours, or we’ll reach out to them. For moderate symptoms, we ask them to come in, and [we] clearly mark on the schedule that it is a respiratory patient, who will be sent to a separate area. If the patient is severe, we don’t even see them and send them directly to the hospital to the ER,” Wu told Medscape Medical News.

These categories parallel the World Health Organization’s designations of uncomplicated illness, mild pneumonia, severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and septic shock. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises case by case regarding decisions as to outpatient or inpatient assignment.

“Patients who pass the initial phone triage are given masks, separated, and sent to different parts of the clinic or are required to wait in their cars until it’s time to be seen,” Wu said.

Step 2: Hospital Arrival

Once at the hospital, the CDC’s interim guidance kicks in.

“Any patient with fever, cough, and shortness of breath presenting with a history of travel to countries with high ongoing transmission or a credible history of exposure should be promptly evaluated for COVID-19,” said Raghavendra Tirupathi, MD, medical director, Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV; chair in infection prevention, Summit Health; and clinical assistant professor of medicine, Penn State School of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“We recommend obtaining baseline CBC with differential, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and procalcitonin. Clues for COVID-19 include leukopenia, seen in 30% to 45% of patients, and lymphocytopenia, seen in 85% of the patients in the case series from China,” Tirupathi said. He uses a respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction panel to rule out other pathogens.

Wu concurs. “This is the one time we are grateful when someone tests positive for the flu! If flu is negative and other common respiratory infections are negative, then we do a COVID-19 test,” she said.

But test results may be delayed. “At the University of Washington, it takes 8 hours, but commercial labs take up to 4 days,” Wu said. All patients with respiratory symptoms are treated as persons under investigation, for whom isolation precautions are required. In addition, for these patients, use of personal protective equipment by caregivers is required.

For suspected pneumonia, the American College of Radiography recommends chest CT to identify peripheral basal ground-glass opacities characteristic of COVID-19.

However, diagnosis should be based on detection of SARS-CoV-2, because chest images for COVID-19 are nonspecific – associated signs can also be seen in H1N1 influenza, SARS, and MERS.

Step 3: Supportive Care

Once a patient is admitted, supportive care entails “maintaining fluid status and nutrition and supporting physiological functions until we heal. It’s treating complications and organ support, whether that means providing supplementary oxygen all the way to ventilator support, and just waiting it out. If a patient progresses to acute respiratory distress syndrome, it becomes tougher,” said David Liebers, MD, chief medical officer and an infectious disease specialist at Ellis Medicine in Schenectady, New York.

Efforts are ramping up to develop therapeutics. Remdesivir, an investigational antiviral drug developed to treat Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fevers, shows activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.

Remdesivir has been used in a few patients on a compassionate-use basis outside of a clinical trial setting. “It’s a nucleotide analogue, and like other drugs of that class, it disrupts nucleic acid production. Some data suggest that it might have some efficacy,” Liebers said.

Antibiotics are reserved for patients suspected of having concomitant bacterial or fungal infections. Liebers said clinicians should be alerted to “the big three” signs of secondary infection – fever, elevated white blood cell count, and lactic acidosis. Immunosuppressed patients are at elevated risk for secondary infection.

Step 4: Managing Complications

Patients do die of COVID-19, mostly through an inability to ventilate, even when supported with oxygen, Liebers told Medscape Medical News. (According to Tirupathi, “The studies from China indicate that from 6%-10% of patients needed ventilators.”)

Liebers continued, “Others may develop sepsis or a syndrome of multisystem organ failure with renal and endothelial collapse, making it difficult to maintain blood pressure. Like with so many pathologies, it is a vicious circle in which everything gets overworked. Off-and-on treatments can sometimes break the cycle: supplementary oxygen, giving red blood cells, dialysis. We support those functions while waiting for healing to occur.”

A facility’s airborne-infection isolation rooms may become filled to capacity, but that isn’t critical, Liebers said. “Airborne precautions are standard to contain measles, tuberculosis, chickenpox, and herpes zoster, in which very small particles spread in the air,” he said.

Consensus is growing that SARS-CoV-2 spreads in large droplets, he added. Private rooms and closed doors may suffice.

Step 5: Discharge

Liebers said that as of now, the million-dollar question regards criteria for discharge.

Patients who clinically improve are sent home with instructions to remain in isolation. They may be tested again for virus before or after discharge.

Liebers and Wu pointed to the experience at EvergreenHealth Medical Center, in Kirkland, Washington, as guidance from the trenches. “They’re the ones who are learning firsthand and passing the experience along to everyone else,” Wu said.

“The situation is unprecedented,” said Liebers, who, like many others, has barely slept these past weeks. “We’re swimming in murky water right now.”

The epidemic in the United States is still months from peaking, Wu emphasized. “There is no vaccine, and many cases are subclinical. COVID-19 has to spread through the country before it infects a critical mass of people who will develop immunity. It’s too late to contain.”

Added Liebers, “It’s a constantly changing situation, and we are still being surprised – not that this wasn’t predicted.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

President declares national emergency for COVID-19, ramps up testing capability

President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to allow for additional resources to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and announced increased testing capacity in partnership with private industry.

During a March 13 press conference, the president said the declaration would “open up access to up to $50 billion” for states and territories in combating the spread of the disease.

He also called on all states to “set up emergency operation centers, effective immediately” and for every hospital “to activate its emergency preparedness plan so that they can meet the needs of Americans everywhere.”

Additionally, he said the declaration will confer broad new authority on the Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that will allow him to “immediately waive provisions of applicable laws and regulations to give doctors, all hospitals, and health care providers maximum flexibility to respond to the virus and care for patients.”

Some of the powers he highlighted included the ability to waive laws to enable telehealth; to waive certain federal license requirements to allow doctors licensed in one state to offer services in other states; the ability to waive limits on beds in critical access hospitals; and to waive rules that hinder hospitals from hiring additional physicians.

The president also announced that more testing capacity will be made available within the next week, in partnership with private industry.

“We want to make sure that those who need a test can get a test very safely, quickly, and conveniently, but we don’t want people to take a test if we feel that they shouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

To help make that determination, a website, developed with Google, is expected to be launched the weekend of March 13 to will allow individuals to input their symptoms and risk factors to help determine if they should be tested. If certain criteria are met, the website will provide locations for drive-through testing facilities. Individuals will be tested using a nasal swab and will receive results within 24-36 hours.

The testing is being done in partnership with retailers, including Target and Walmart (who are providing parking lot space for the pop-up testing facilities) and testing companies LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

The new test was developed by Roche and just received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

“We therefore expect up to a half-million additional tests will be available early next week,” President Trump said, adding that testing locations will “probably” be announced on Sunday, March 15.

A second application for a new test, submitted by Thermo Fisher, is currently under review at the FDA and is expected to be approved within the next 24 hours, he said. This would add an additional 1.4 million tests in the next week and 5 million within a month, according to the president.

President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to allow for additional resources to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and announced increased testing capacity in partnership with private industry.

During a March 13 press conference, the president said the declaration would “open up access to up to $50 billion” for states and territories in combating the spread of the disease.

He also called on all states to “set up emergency operation centers, effective immediately” and for every hospital “to activate its emergency preparedness plan so that they can meet the needs of Americans everywhere.”

Additionally, he said the declaration will confer broad new authority on the Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that will allow him to “immediately waive provisions of applicable laws and regulations to give doctors, all hospitals, and health care providers maximum flexibility to respond to the virus and care for patients.”

Some of the powers he highlighted included the ability to waive laws to enable telehealth; to waive certain federal license requirements to allow doctors licensed in one state to offer services in other states; the ability to waive limits on beds in critical access hospitals; and to waive rules that hinder hospitals from hiring additional physicians.

The president also announced that more testing capacity will be made available within the next week, in partnership with private industry.

“We want to make sure that those who need a test can get a test very safely, quickly, and conveniently, but we don’t want people to take a test if we feel that they shouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

To help make that determination, a website, developed with Google, is expected to be launched the weekend of March 13 to will allow individuals to input their symptoms and risk factors to help determine if they should be tested. If certain criteria are met, the website will provide locations for drive-through testing facilities. Individuals will be tested using a nasal swab and will receive results within 24-36 hours.

The testing is being done in partnership with retailers, including Target and Walmart (who are providing parking lot space for the pop-up testing facilities) and testing companies LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

The new test was developed by Roche and just received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

“We therefore expect up to a half-million additional tests will be available early next week,” President Trump said, adding that testing locations will “probably” be announced on Sunday, March 15.

A second application for a new test, submitted by Thermo Fisher, is currently under review at the FDA and is expected to be approved within the next 24 hours, he said. This would add an additional 1.4 million tests in the next week and 5 million within a month, according to the president.

President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to allow for additional resources to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and announced increased testing capacity in partnership with private industry.

During a March 13 press conference, the president said the declaration would “open up access to up to $50 billion” for states and territories in combating the spread of the disease.

He also called on all states to “set up emergency operation centers, effective immediately” and for every hospital “to activate its emergency preparedness plan so that they can meet the needs of Americans everywhere.”

Additionally, he said the declaration will confer broad new authority on the Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that will allow him to “immediately waive provisions of applicable laws and regulations to give doctors, all hospitals, and health care providers maximum flexibility to respond to the virus and care for patients.”

Some of the powers he highlighted included the ability to waive laws to enable telehealth; to waive certain federal license requirements to allow doctors licensed in one state to offer services in other states; the ability to waive limits on beds in critical access hospitals; and to waive rules that hinder hospitals from hiring additional physicians.

The president also announced that more testing capacity will be made available within the next week, in partnership with private industry.

“We want to make sure that those who need a test can get a test very safely, quickly, and conveniently, but we don’t want people to take a test if we feel that they shouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

To help make that determination, a website, developed with Google, is expected to be launched the weekend of March 13 to will allow individuals to input their symptoms and risk factors to help determine if they should be tested. If certain criteria are met, the website will provide locations for drive-through testing facilities. Individuals will be tested using a nasal swab and will receive results within 24-36 hours.

The testing is being done in partnership with retailers, including Target and Walmart (who are providing parking lot space for the pop-up testing facilities) and testing companies LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

The new test was developed by Roche and just received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

“We therefore expect up to a half-million additional tests will be available early next week,” President Trump said, adding that testing locations will “probably” be announced on Sunday, March 15.

A second application for a new test, submitted by Thermo Fisher, is currently under review at the FDA and is expected to be approved within the next 24 hours, he said. This would add an additional 1.4 million tests in the next week and 5 million within a month, according to the president.

After weeks of decline, influenza activity increases slightly

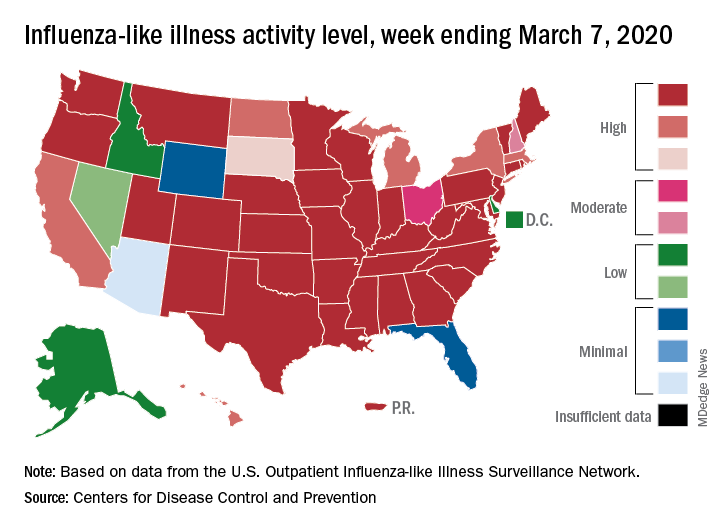

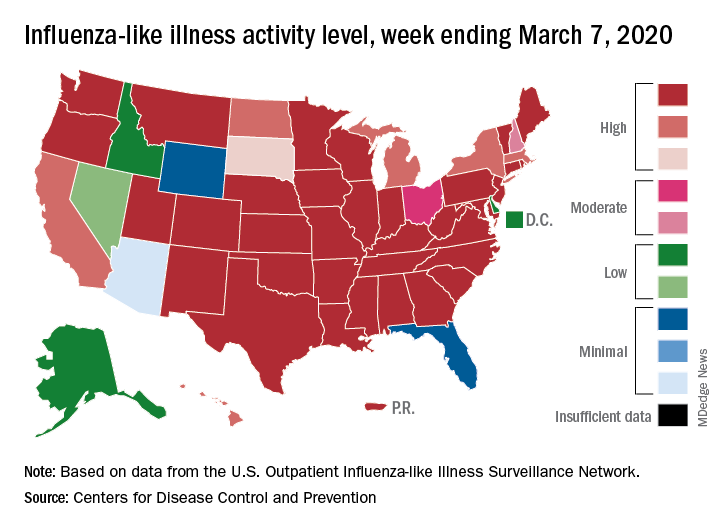

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

Lombardy ICU capacity stressed to breaking point by COVID-19 outbreak

The outbreak of COVID-19 in the Lombardy region of Italy has severely stressed the medical system and the current level of activity may not be sustainable for long, according to Maurizio Cecconi, MD, of the department of anesthesia and intensive care, Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan. Dr. Cecconi spoke via JAMA Live Stream interview with Howard Bauchner, MD, the Editor in Chief of JAMA.

A summary of comments by Dr. Cecconi and two colleagues was simultaneously published in JAMA (2020 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031).

Dr. Cecconi discussed the progress and medical response to the swiftly expanding outbreak that began on Feb. 20. A man in his 30s was admitted to the Codogno Hospital, Lodi, Lombardy, Italy, in respiratory distress. He tested positive for a new coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In less than 24 hours, the hospital had 36 cases of COVID-19.

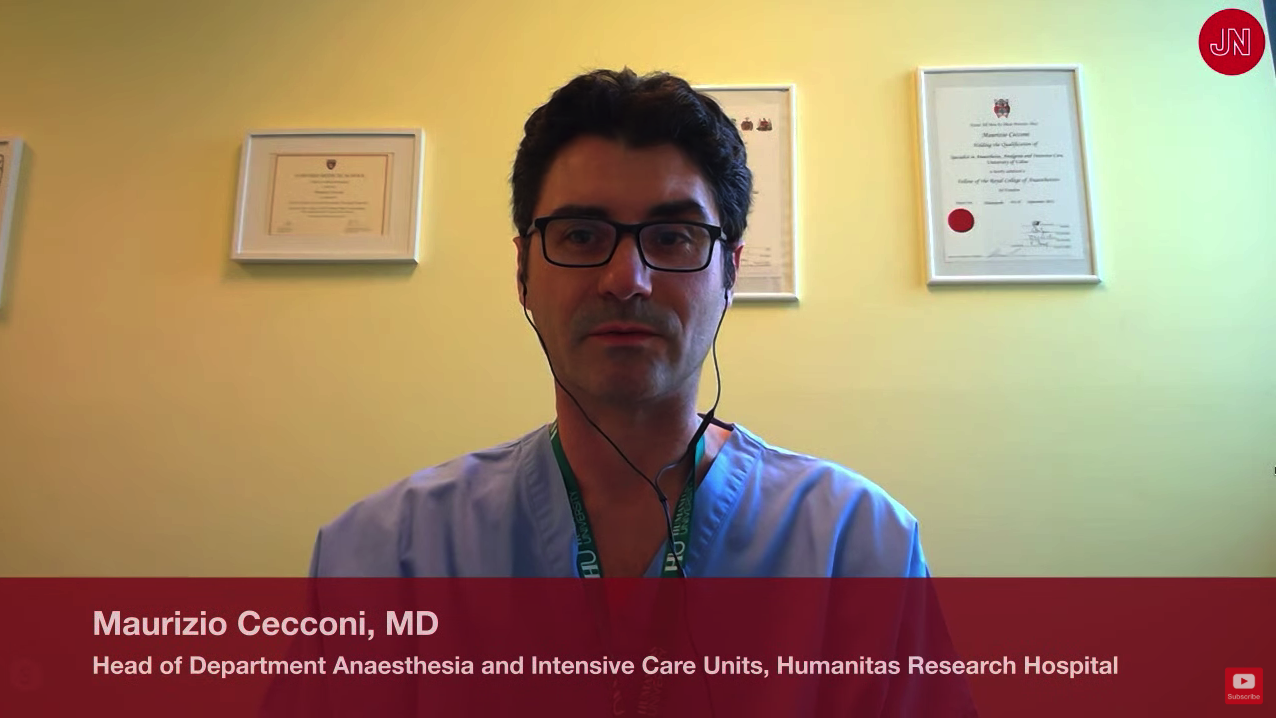

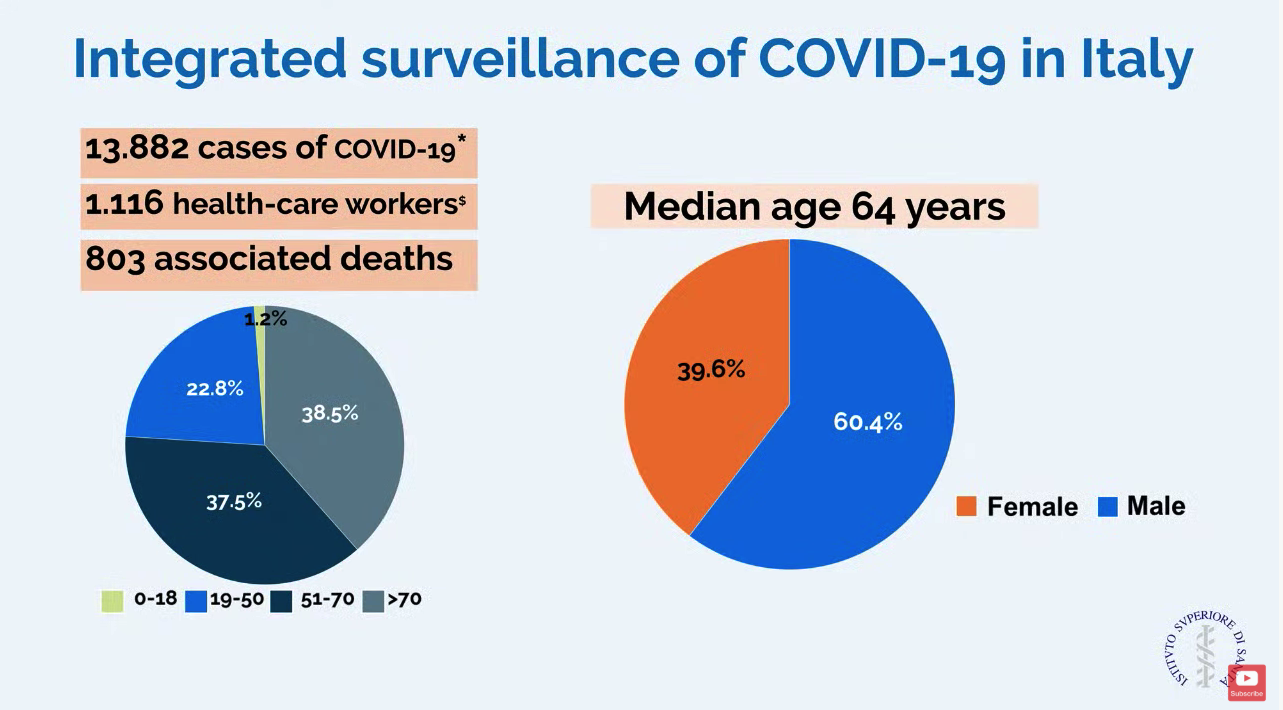

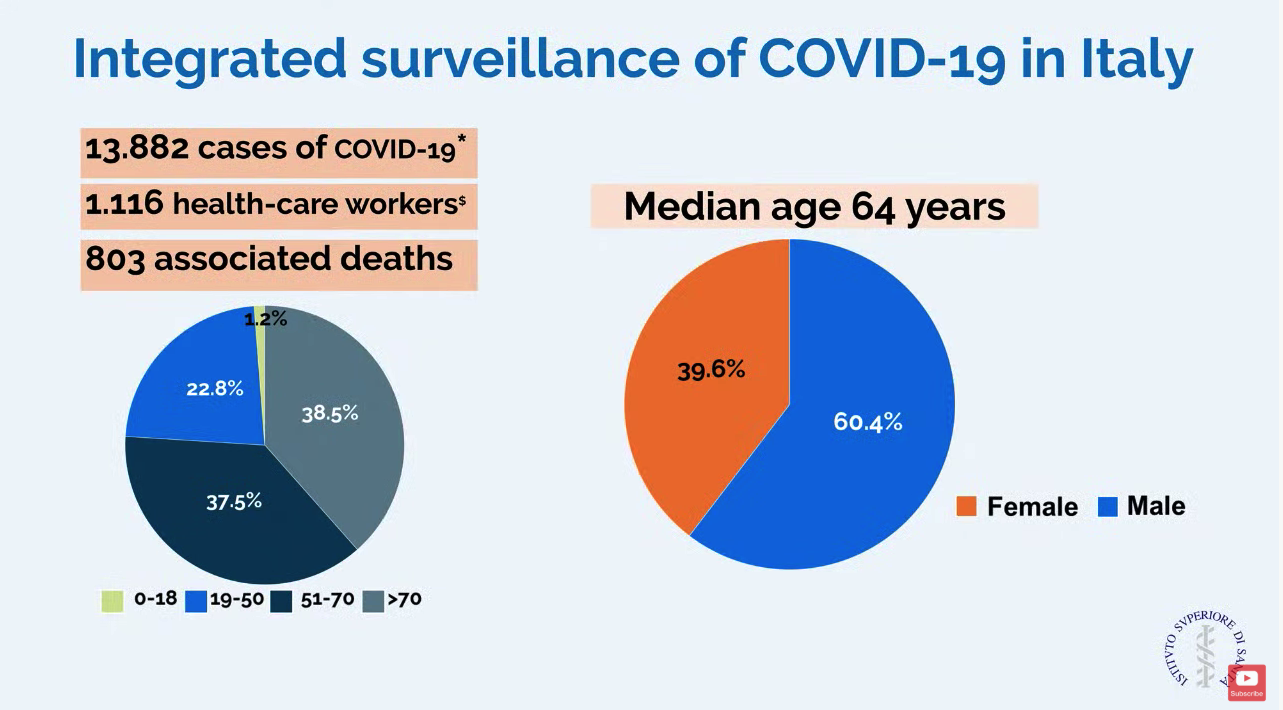

In a slide provided by the Italian National Health Service, the number of cases in Italy stands at 13,882 with 803 associated deaths.

ICU resources have been severely stressed. Before the outbreak, Lombardy had 720 ICU beds (about 5% of total beds). Within 48 hours of the first case, ICU cohorts were formed in 15 hub hospitals totaling 130 COVID-19 ICU beds. By March 7, the total number of dedicated cohorted COVID-19 ICU beds was 482.

“The proportion of ICU admissions represents 12% of the total positive cases, and 16% of all hospitalized patients,” compared with about 5% of ICU admissions reported from China. The difference may be attributable to different criteria for ICU admissions in Italy, compared with China, according to Dr. Cecconi and colleagues.

Dr. Cecconi mentioned that there were relatively few cases in children, and they had relatively mild disease. The death rate among patients remained under 1% up to age 59. For patients aged 60-69 years, the rate was 2.7%; for patients aged 70-79 years, the rate was 9.6%; for those aged 80-89, the rate was much higher at 16.6%.

Modeled forecasts of the potential number of cases in Lombardy are daunting. “The linear model forecasts that approximately 869 ICU admissions could occur by March 20, 2020, whereas the exponential model growth projects that approximately 14,542 ICU admissions could occur by then. Even though these projections are hypothetical and involve various assumptions, any substantial increase in the number of critically ill patients would rapidly exceed total ICU capacity, without even considering other critical admissions, such as for trauma, stroke, and other emergencies,” wrote Dr. Cecconi and his colleagues in JAMA. He said, “We could be on our knees very soon,” referring to the potential dramatic increase in cases.

Dr. Cecconi had some recommendations for other countries in which a major outbreak has not yet occurred. He recommended going beyond expanding ICU and isolation capacity and focus on training staff with simulation for treating these highly contagious patients. His medical center has worked hard to protect staff but 1,116 health care workers have tested positive for the virus. Conditions for staff are very difficult in full protective gear, and Dr. Cecconi commended the heroic work by these doctors and nurses.

In addition, Dr. Cecconi is focused on supportive care for patients and does not recommend using untried approaches on these patients that could cause harm. “Everyone wants to find a specific drug for these patients, but I say there is not particular drug at the moment.” He stressed that, despite the crisis, doctors should focus on evidence-based treatment and tried-and-true supportive care.

Disclosures by Dr. Cecconi are available on the JAMA website.

CORRECTION 3/13/2020 2.18 P.M. The death rate for patients aged 70-79 was corrected.

The outbreak of COVID-19 in the Lombardy region of Italy has severely stressed the medical system and the current level of activity may not be sustainable for long, according to Maurizio Cecconi, MD, of the department of anesthesia and intensive care, Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan. Dr. Cecconi spoke via JAMA Live Stream interview with Howard Bauchner, MD, the Editor in Chief of JAMA.

A summary of comments by Dr. Cecconi and two colleagues was simultaneously published in JAMA (2020 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031).

Dr. Cecconi discussed the progress and medical response to the swiftly expanding outbreak that began on Feb. 20. A man in his 30s was admitted to the Codogno Hospital, Lodi, Lombardy, Italy, in respiratory distress. He tested positive for a new coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In less than 24 hours, the hospital had 36 cases of COVID-19.

In a slide provided by the Italian National Health Service, the number of cases in Italy stands at 13,882 with 803 associated deaths.

ICU resources have been severely stressed. Before the outbreak, Lombardy had 720 ICU beds (about 5% of total beds). Within 48 hours of the first case, ICU cohorts were formed in 15 hub hospitals totaling 130 COVID-19 ICU beds. By March 7, the total number of dedicated cohorted COVID-19 ICU beds was 482.

“The proportion of ICU admissions represents 12% of the total positive cases, and 16% of all hospitalized patients,” compared with about 5% of ICU admissions reported from China. The difference may be attributable to different criteria for ICU admissions in Italy, compared with China, according to Dr. Cecconi and colleagues.

Dr. Cecconi mentioned that there were relatively few cases in children, and they had relatively mild disease. The death rate among patients remained under 1% up to age 59. For patients aged 60-69 years, the rate was 2.7%; for patients aged 70-79 years, the rate was 9.6%; for those aged 80-89, the rate was much higher at 16.6%.

Modeled forecasts of the potential number of cases in Lombardy are daunting. “The linear model forecasts that approximately 869 ICU admissions could occur by March 20, 2020, whereas the exponential model growth projects that approximately 14,542 ICU admissions could occur by then. Even though these projections are hypothetical and involve various assumptions, any substantial increase in the number of critically ill patients would rapidly exceed total ICU capacity, without even considering other critical admissions, such as for trauma, stroke, and other emergencies,” wrote Dr. Cecconi and his colleagues in JAMA. He said, “We could be on our knees very soon,” referring to the potential dramatic increase in cases.

Dr. Cecconi had some recommendations for other countries in which a major outbreak has not yet occurred. He recommended going beyond expanding ICU and isolation capacity and focus on training staff with simulation for treating these highly contagious patients. His medical center has worked hard to protect staff but 1,116 health care workers have tested positive for the virus. Conditions for staff are very difficult in full protective gear, and Dr. Cecconi commended the heroic work by these doctors and nurses.

In addition, Dr. Cecconi is focused on supportive care for patients and does not recommend using untried approaches on these patients that could cause harm. “Everyone wants to find a specific drug for these patients, but I say there is not particular drug at the moment.” He stressed that, despite the crisis, doctors should focus on evidence-based treatment and tried-and-true supportive care.

Disclosures by Dr. Cecconi are available on the JAMA website.

CORRECTION 3/13/2020 2.18 P.M. The death rate for patients aged 70-79 was corrected.

The outbreak of COVID-19 in the Lombardy region of Italy has severely stressed the medical system and the current level of activity may not be sustainable for long, according to Maurizio Cecconi, MD, of the department of anesthesia and intensive care, Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan. Dr. Cecconi spoke via JAMA Live Stream interview with Howard Bauchner, MD, the Editor in Chief of JAMA.

A summary of comments by Dr. Cecconi and two colleagues was simultaneously published in JAMA (2020 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031).

Dr. Cecconi discussed the progress and medical response to the swiftly expanding outbreak that began on Feb. 20. A man in his 30s was admitted to the Codogno Hospital, Lodi, Lombardy, Italy, in respiratory distress. He tested positive for a new coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In less than 24 hours, the hospital had 36 cases of COVID-19.

In a slide provided by the Italian National Health Service, the number of cases in Italy stands at 13,882 with 803 associated deaths.

ICU resources have been severely stressed. Before the outbreak, Lombardy had 720 ICU beds (about 5% of total beds). Within 48 hours of the first case, ICU cohorts were formed in 15 hub hospitals totaling 130 COVID-19 ICU beds. By March 7, the total number of dedicated cohorted COVID-19 ICU beds was 482.

“The proportion of ICU admissions represents 12% of the total positive cases, and 16% of all hospitalized patients,” compared with about 5% of ICU admissions reported from China. The difference may be attributable to different criteria for ICU admissions in Italy, compared with China, according to Dr. Cecconi and colleagues.

Dr. Cecconi mentioned that there were relatively few cases in children, and they had relatively mild disease. The death rate among patients remained under 1% up to age 59. For patients aged 60-69 years, the rate was 2.7%; for patients aged 70-79 years, the rate was 9.6%; for those aged 80-89, the rate was much higher at 16.6%.

Modeled forecasts of the potential number of cases in Lombardy are daunting. “The linear model forecasts that approximately 869 ICU admissions could occur by March 20, 2020, whereas the exponential model growth projects that approximately 14,542 ICU admissions could occur by then. Even though these projections are hypothetical and involve various assumptions, any substantial increase in the number of critically ill patients would rapidly exceed total ICU capacity, without even considering other critical admissions, such as for trauma, stroke, and other emergencies,” wrote Dr. Cecconi and his colleagues in JAMA. He said, “We could be on our knees very soon,” referring to the potential dramatic increase in cases.

Dr. Cecconi had some recommendations for other countries in which a major outbreak has not yet occurred. He recommended going beyond expanding ICU and isolation capacity and focus on training staff with simulation for treating these highly contagious patients. His medical center has worked hard to protect staff but 1,116 health care workers have tested positive for the virus. Conditions for staff are very difficult in full protective gear, and Dr. Cecconi commended the heroic work by these doctors and nurses.

In addition, Dr. Cecconi is focused on supportive care for patients and does not recommend using untried approaches on these patients that could cause harm. “Everyone wants to find a specific drug for these patients, but I say there is not particular drug at the moment.” He stressed that, despite the crisis, doctors should focus on evidence-based treatment and tried-and-true supportive care.

Disclosures by Dr. Cecconi are available on the JAMA website.

CORRECTION 3/13/2020 2.18 P.M. The death rate for patients aged 70-79 was corrected.

REPORTING FROM JAMA LIVE STREAM

Internist reports from COVID-19 front lines near Seattle

KENT, WASHINGTON – The first thing I learned in this outbreak is that my sense of alarm has been deadened by years of medical practice. As a primary care doctor working south of Seattle, in the University of Washington’s Kent neighborhood clinic, I have dealt with long hours, the sometimes-insurmountable problems of the patients I care for, and the constant, gnawing fear of missing something and doing harm. To get through my day, I’ve done my best to rationalize that fear, to explain it away.

I can’t explain how, when I heard the news of the coronavirus epidemic in China, I didn’t think it would affect me. I can’t explain how news of the first patient presenting to an urgent care north of Seattle didn’t cause me, or all health care providers, to think about how we would respond. I can’t explain why so many doctors were dismissive of the very real threat that was about to explode. I can’t explain why it took 6 weeks for the COVID-19 outbreak to seem real to me.

If you work in a doctor’s office, emergency department, hospital, or urgent care center and have not seen a coronavirus case yet, you may have time to think through what is likely to happen in your community. We did not activate a chain of command or decide how information was going to be communicated to the front line and back to leadership. Few of us ran worst-case scenarios.

By March 12, we had 376 confirmed cases, and likely more than a thousand are undetected. The moment of realization of the severity of the outbreak didn’t come to me until Saturday, Feb. 29. In the week prior, several patients had come into the clinic with symptoms and potential exposures, but not meeting the narrow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention testing criteria. They were all advised by the Washington Department of Health to go home. At the time, it seemed like decent advice. Frontline providers didn’t know that there had been two cases of community transmission weeks before, or that one was about to become the first death in Washington state. I still advised patients to quarantine themselves. In the absence of testing, we had to assume everyone was positive and should stay home until 72 hours after their symptoms resolved. Studying the state’s FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] intently, I wrote insistent letters to inflexible bosses, explaining that their employees needed to stay home.

I worked that Saturday. Half of my patients had coughs. Our team insisted that they wear masks. One woman refused, and I refused to see her until she did. In a customer service–oriented health care system, I had been schooled to accommodate almost any patient request. But I was not about to put my staff and other patients at risk. Reluctantly, she complied.

On my lunch break, my partner called me to tell me he was at the grocery store. “Why?” I asked, since we usually went together. It became clear he was worried about an outbreak. He had been following the news closely and tried to tell me how deadly this could get and how quickly the disease could spread. I brushed his fears aside, as more evidence of his sweet and overly cautious nature. “It’ll be fine,” I said with misplaced confidence.

Later that day, I heard about the first death and the outbreak at Life Care, a nursing home north of Seattle. I learned that firefighters who had responded to distress calls were under quarantine. I learned through an epidemiologist that there were likely hundreds of undetected cases throughout Washington.

On Monday, our clinic decided to convert all cases with symptoms into telemedicine visits. Luckily, we had been building the capacity to see and treat patients virtually for a while. We have ramped up quickly, but there have been bumps along the way. It’s difficult to convince those who are anxious about their symptoms to allow us to use telemedicine for everyone’s safety. It is unclear how much liability we are taking on as individual providers with this approach or who will speak up for us if something goes wrong.

Patients don’t seem to know where to get their information, and they have been turning to increasingly bizarre sources. For the poorest, who have had so much trouble accessing care, I cannot blame them for not knowing whom to trust. I post what I know on Twitter and Facebook, but I know I’m no match for cynical social media algorithms.

Testing was still not available at my clinic the first week of March, and it remains largely unavailable throughout much of the country. We have lost weeks of opportunity to contain this. Luckily, on March 4, the University of Washington was finally allowed to use their homegrown test and bypass the limited supply from the CDC. But our capacity at UW is still limited, and the test remained unavailable to the majority of those potentially showing symptoms until March 9.

I am used to being less worried than my patients. I am used to reassuring them. But over the first week of March, I had an eerie sense that my alarm far outstripped theirs. I got relatively few questions about coronavirus, even as the number of cases continued to rise. It wasn’t until the end of the week that I noticed a few were truly fearful. Patients started stealing the gloves and the hand sanitizer, and we had to zealously guard them. My hands are raw from washing.

Throughout this time, I have been grateful for a centralized drive with clear protocols. I am grateful for clear messages at the beginning and end of the day from our CEO. I hope that other clinics model this and have daily in-person meetings, because too much cannot be conveyed in an email when the situation changes hourly.

But our health system nationally was already stretched thin before, and providers have sacrificed a lot, especially in the most critical settings, to provide decent patient care. Now we are asked to risk our health and safety, and our family’s, and I worry about the erosion of trust and work conditions for those on the front lines. I also worry our patients won’t believe us when we have allowed the costs of care to continue to rise and ruin their lives. I worry about the millions of people without doctors to call because they have no insurance, and because so many primary care physicians have left unsustainable jobs.

I am grateful that few of my colleagues have been sick and that those that were called out. I am grateful for the new nurse practitioners in our clinic who took the lion’s share of possibly affected patients and triaged hundreds of phone calls, creating note and message templates that we all use. I am grateful that my clinic manager insisted on doing a drill with all the staff members.

I am grateful that we were reminded that we are a team and that if the call center and cleaning crews and front desk are excluded, then our protocols are useless. I am grateful that our registered nurses quickly shifted to triage. I am grateful that I have testing available.

This week, for the first time since I started working, multiple patients asked how I am doing and expressed their thanks. I am most grateful for them.

I can’t tell you what to do or what is going to happen, but I can tell you that you need to prepare now. You need to run drills and catch the holes in your plans before the pandemic reaches you. You need to be creative and honest about the flaws in your organization that this pandemic will inevitably expose. You need to meet with your team every day and remember that we are all going to be stretched even thinner than before.

Most of us will get through this, but many of us won’t. And for those who do, we need to be honest about our successes and failures. We need to build a system that can do better next time. Because this is not the last pandemic we will face.

Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is a general internist at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent. She completed her residency at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and specializes in addiction medicine. She also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

KENT, WASHINGTON – The first thing I learned in this outbreak is that my sense of alarm has been deadened by years of medical practice. As a primary care doctor working south of Seattle, in the University of Washington’s Kent neighborhood clinic, I have dealt with long hours, the sometimes-insurmountable problems of the patients I care for, and the constant, gnawing fear of missing something and doing harm. To get through my day, I’ve done my best to rationalize that fear, to explain it away.

I can’t explain how, when I heard the news of the coronavirus epidemic in China, I didn’t think it would affect me. I can’t explain how news of the first patient presenting to an urgent care north of Seattle didn’t cause me, or all health care providers, to think about how we would respond. I can’t explain why so many doctors were dismissive of the very real threat that was about to explode. I can’t explain why it took 6 weeks for the COVID-19 outbreak to seem real to me.

If you work in a doctor’s office, emergency department, hospital, or urgent care center and have not seen a coronavirus case yet, you may have time to think through what is likely to happen in your community. We did not activate a chain of command or decide how information was going to be communicated to the front line and back to leadership. Few of us ran worst-case scenarios.

By March 12, we had 376 confirmed cases, and likely more than a thousand are undetected. The moment of realization of the severity of the outbreak didn’t come to me until Saturday, Feb. 29. In the week prior, several patients had come into the clinic with symptoms and potential exposures, but not meeting the narrow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention testing criteria. They were all advised by the Washington Department of Health to go home. At the time, it seemed like decent advice. Frontline providers didn’t know that there had been two cases of community transmission weeks before, or that one was about to become the first death in Washington state. I still advised patients to quarantine themselves. In the absence of testing, we had to assume everyone was positive and should stay home until 72 hours after their symptoms resolved. Studying the state’s FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] intently, I wrote insistent letters to inflexible bosses, explaining that their employees needed to stay home.

I worked that Saturday. Half of my patients had coughs. Our team insisted that they wear masks. One woman refused, and I refused to see her until she did. In a customer service–oriented health care system, I had been schooled to accommodate almost any patient request. But I was not about to put my staff and other patients at risk. Reluctantly, she complied.

On my lunch break, my partner called me to tell me he was at the grocery store. “Why?” I asked, since we usually went together. It became clear he was worried about an outbreak. He had been following the news closely and tried to tell me how deadly this could get and how quickly the disease could spread. I brushed his fears aside, as more evidence of his sweet and overly cautious nature. “It’ll be fine,” I said with misplaced confidence.

Later that day, I heard about the first death and the outbreak at Life Care, a nursing home north of Seattle. I learned that firefighters who had responded to distress calls were under quarantine. I learned through an epidemiologist that there were likely hundreds of undetected cases throughout Washington.

On Monday, our clinic decided to convert all cases with symptoms into telemedicine visits. Luckily, we had been building the capacity to see and treat patients virtually for a while. We have ramped up quickly, but there have been bumps along the way. It’s difficult to convince those who are anxious about their symptoms to allow us to use telemedicine for everyone’s safety. It is unclear how much liability we are taking on as individual providers with this approach or who will speak up for us if something goes wrong.

Patients don’t seem to know where to get their information, and they have been turning to increasingly bizarre sources. For the poorest, who have had so much trouble accessing care, I cannot blame them for not knowing whom to trust. I post what I know on Twitter and Facebook, but I know I’m no match for cynical social media algorithms.

Testing was still not available at my clinic the first week of March, and it remains largely unavailable throughout much of the country. We have lost weeks of opportunity to contain this. Luckily, on March 4, the University of Washington was finally allowed to use their homegrown test and bypass the limited supply from the CDC. But our capacity at UW is still limited, and the test remained unavailable to the majority of those potentially showing symptoms until March 9.

I am used to being less worried than my patients. I am used to reassuring them. But over the first week of March, I had an eerie sense that my alarm far outstripped theirs. I got relatively few questions about coronavirus, even as the number of cases continued to rise. It wasn’t until the end of the week that I noticed a few were truly fearful. Patients started stealing the gloves and the hand sanitizer, and we had to zealously guard them. My hands are raw from washing.

Throughout this time, I have been grateful for a centralized drive with clear protocols. I am grateful for clear messages at the beginning and end of the day from our CEO. I hope that other clinics model this and have daily in-person meetings, because too much cannot be conveyed in an email when the situation changes hourly.

But our health system nationally was already stretched thin before, and providers have sacrificed a lot, especially in the most critical settings, to provide decent patient care. Now we are asked to risk our health and safety, and our family’s, and I worry about the erosion of trust and work conditions for those on the front lines. I also worry our patients won’t believe us when we have allowed the costs of care to continue to rise and ruin their lives. I worry about the millions of people without doctors to call because they have no insurance, and because so many primary care physicians have left unsustainable jobs.

I am grateful that few of my colleagues have been sick and that those that were called out. I am grateful for the new nurse practitioners in our clinic who took the lion’s share of possibly affected patients and triaged hundreds of phone calls, creating note and message templates that we all use. I am grateful that my clinic manager insisted on doing a drill with all the staff members.

I am grateful that we were reminded that we are a team and that if the call center and cleaning crews and front desk are excluded, then our protocols are useless. I am grateful that our registered nurses quickly shifted to triage. I am grateful that I have testing available.

This week, for the first time since I started working, multiple patients asked how I am doing and expressed their thanks. I am most grateful for them.

I can’t tell you what to do or what is going to happen, but I can tell you that you need to prepare now. You need to run drills and catch the holes in your plans before the pandemic reaches you. You need to be creative and honest about the flaws in your organization that this pandemic will inevitably expose. You need to meet with your team every day and remember that we are all going to be stretched even thinner than before.

Most of us will get through this, but many of us won’t. And for those who do, we need to be honest about our successes and failures. We need to build a system that can do better next time. Because this is not the last pandemic we will face.

Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is a general internist at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent. She completed her residency at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and specializes in addiction medicine. She also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

KENT, WASHINGTON – The first thing I learned in this outbreak is that my sense of alarm has been deadened by years of medical practice. As a primary care doctor working south of Seattle, in the University of Washington’s Kent neighborhood clinic, I have dealt with long hours, the sometimes-insurmountable problems of the patients I care for, and the constant, gnawing fear of missing something and doing harm. To get through my day, I’ve done my best to rationalize that fear, to explain it away.

I can’t explain how, when I heard the news of the coronavirus epidemic in China, I didn’t think it would affect me. I can’t explain how news of the first patient presenting to an urgent care north of Seattle didn’t cause me, or all health care providers, to think about how we would respond. I can’t explain why so many doctors were dismissive of the very real threat that was about to explode. I can’t explain why it took 6 weeks for the COVID-19 outbreak to seem real to me.

If you work in a doctor’s office, emergency department, hospital, or urgent care center and have not seen a coronavirus case yet, you may have time to think through what is likely to happen in your community. We did not activate a chain of command or decide how information was going to be communicated to the front line and back to leadership. Few of us ran worst-case scenarios.