User login

Fat-free mass index tied to outcomes in underweight COPD patients

Higher fat-free mass was tied to exercise outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were underweight but not in those who were obese or nearly obese, based on data from more than 2,000 individuals.

Change in body composition, including a lower fat-free mass index (FFMI), often occurs in patients with COPD irrespective of body weight, write Felipe V.C. Machado, MSc, of Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

However, the impact of changes in FFMI on outcomes including exercise capacity, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and systemic inflammation in patients with COPD stratified by BMI has not been well studied, they said.

In a study published in the journal CHEST, the researchers reviewed data from the COPD and Systemic Consequences – Comorbidities Network (COSYCONET) cohort. The study population included 2,137 adults with COPD (mean age 65 years; 61% men). Patients were divided into four groups based on weight: underweight (UW), normal weight (NW), pre-obese (PO), and obese (OB). These groups accounted for 12.3%, 31.3%, 39.6%, and 16.8%, respectively, of the study population.

Exercise capacity was assessed using the 6-minute walk distance test (6MWD), health-related quality of life was assessed using the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD, and systemic inflammation was assessed using blood markers including white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein (CRP). Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA).

Overall, the frequency of low FFMI decreased from lower to higher BMI groups, occurring in 81% of UW patients, 53% of NW patients, 42% of PO patients, and 39% of OB patients.

Notably, after adjusting for multiple variables, after controlling for lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second – FEV1), the researchers wrote.

However, compared with the other BMI groups, NW patients with high FFMI showed the greatest exercise capacity and health-related quality of life on average, with the lowest degree of airflow limitation (FEV1, 59.5), lowest proportion of patients with mMRC greater than 2 (27%), highest levels of physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire score), best exercise capacity (6MWD, 77) and highest HRQL (SGRQ total score 37).

Body composition was associated differently with exercise capacity, HRQL, and systemic inflammation according to BMI group, the researchers write in their discussion. “We found that stratification using BMI allowed discrimination of groups of patients with COPD who showed slight but significant differences in lung function, exercise capacity, HRQL and systemic inflammation,” they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of BIA for body composition, which may be subject to hydration and fed conditions, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of reference values from a general population sample younger than much of the study population and the cross-sectional design that does not prove causality, the researchers noted.

However, the results support those of previous studies and suggest that normal weight and high FFMI is the most favorable combination to promote positive outcomes in COPD, they conclude. “Clinicians and researchers should consider screening patients with COPD for body composition abnormalities through a combination of BMI and FFMI classifications rather than each of the two indexes alone,” they say.

The COSYCONET study is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Competence Network Asthma and COPD (ASCONET) in collaboration with the German Center for Lung Research (DZL). The study also was funded by AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Mr. Machado disclosed financial support from ZonMW.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher fat-free mass was tied to exercise outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were underweight but not in those who were obese or nearly obese, based on data from more than 2,000 individuals.

Change in body composition, including a lower fat-free mass index (FFMI), often occurs in patients with COPD irrespective of body weight, write Felipe V.C. Machado, MSc, of Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

However, the impact of changes in FFMI on outcomes including exercise capacity, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and systemic inflammation in patients with COPD stratified by BMI has not been well studied, they said.

In a study published in the journal CHEST, the researchers reviewed data from the COPD and Systemic Consequences – Comorbidities Network (COSYCONET) cohort. The study population included 2,137 adults with COPD (mean age 65 years; 61% men). Patients were divided into four groups based on weight: underweight (UW), normal weight (NW), pre-obese (PO), and obese (OB). These groups accounted for 12.3%, 31.3%, 39.6%, and 16.8%, respectively, of the study population.

Exercise capacity was assessed using the 6-minute walk distance test (6MWD), health-related quality of life was assessed using the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD, and systemic inflammation was assessed using blood markers including white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein (CRP). Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA).

Overall, the frequency of low FFMI decreased from lower to higher BMI groups, occurring in 81% of UW patients, 53% of NW patients, 42% of PO patients, and 39% of OB patients.

Notably, after adjusting for multiple variables, after controlling for lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second – FEV1), the researchers wrote.

However, compared with the other BMI groups, NW patients with high FFMI showed the greatest exercise capacity and health-related quality of life on average, with the lowest degree of airflow limitation (FEV1, 59.5), lowest proportion of patients with mMRC greater than 2 (27%), highest levels of physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire score), best exercise capacity (6MWD, 77) and highest HRQL (SGRQ total score 37).

Body composition was associated differently with exercise capacity, HRQL, and systemic inflammation according to BMI group, the researchers write in their discussion. “We found that stratification using BMI allowed discrimination of groups of patients with COPD who showed slight but significant differences in lung function, exercise capacity, HRQL and systemic inflammation,” they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of BIA for body composition, which may be subject to hydration and fed conditions, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of reference values from a general population sample younger than much of the study population and the cross-sectional design that does not prove causality, the researchers noted.

However, the results support those of previous studies and suggest that normal weight and high FFMI is the most favorable combination to promote positive outcomes in COPD, they conclude. “Clinicians and researchers should consider screening patients with COPD for body composition abnormalities through a combination of BMI and FFMI classifications rather than each of the two indexes alone,” they say.

The COSYCONET study is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Competence Network Asthma and COPD (ASCONET) in collaboration with the German Center for Lung Research (DZL). The study also was funded by AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Mr. Machado disclosed financial support from ZonMW.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher fat-free mass was tied to exercise outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were underweight but not in those who were obese or nearly obese, based on data from more than 2,000 individuals.

Change in body composition, including a lower fat-free mass index (FFMI), often occurs in patients with COPD irrespective of body weight, write Felipe V.C. Machado, MSc, of Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

However, the impact of changes in FFMI on outcomes including exercise capacity, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and systemic inflammation in patients with COPD stratified by BMI has not been well studied, they said.

In a study published in the journal CHEST, the researchers reviewed data from the COPD and Systemic Consequences – Comorbidities Network (COSYCONET) cohort. The study population included 2,137 adults with COPD (mean age 65 years; 61% men). Patients were divided into four groups based on weight: underweight (UW), normal weight (NW), pre-obese (PO), and obese (OB). These groups accounted for 12.3%, 31.3%, 39.6%, and 16.8%, respectively, of the study population.

Exercise capacity was assessed using the 6-minute walk distance test (6MWD), health-related quality of life was assessed using the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD, and systemic inflammation was assessed using blood markers including white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein (CRP). Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA).

Overall, the frequency of low FFMI decreased from lower to higher BMI groups, occurring in 81% of UW patients, 53% of NW patients, 42% of PO patients, and 39% of OB patients.

Notably, after adjusting for multiple variables, after controlling for lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second – FEV1), the researchers wrote.

However, compared with the other BMI groups, NW patients with high FFMI showed the greatest exercise capacity and health-related quality of life on average, with the lowest degree of airflow limitation (FEV1, 59.5), lowest proportion of patients with mMRC greater than 2 (27%), highest levels of physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire score), best exercise capacity (6MWD, 77) and highest HRQL (SGRQ total score 37).

Body composition was associated differently with exercise capacity, HRQL, and systemic inflammation according to BMI group, the researchers write in their discussion. “We found that stratification using BMI allowed discrimination of groups of patients with COPD who showed slight but significant differences in lung function, exercise capacity, HRQL and systemic inflammation,” they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of BIA for body composition, which may be subject to hydration and fed conditions, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of reference values from a general population sample younger than much of the study population and the cross-sectional design that does not prove causality, the researchers noted.

However, the results support those of previous studies and suggest that normal weight and high FFMI is the most favorable combination to promote positive outcomes in COPD, they conclude. “Clinicians and researchers should consider screening patients with COPD for body composition abnormalities through a combination of BMI and FFMI classifications rather than each of the two indexes alone,” they say.

The COSYCONET study is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Competence Network Asthma and COPD (ASCONET) in collaboration with the German Center for Lung Research (DZL). The study also was funded by AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Mr. Machado disclosed financial support from ZonMW.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From the Journal CHEST

A doctor saves a drowning family in a dangerous river

Is There a Doctor in the House? is a new series telling these stories.

I live on the Maumee River in Ohio, about 50 yards from the water. I had an early quit time and came home to meet my wife for lunch. Afterward, I went up to my barn across the main road to tinker around. It was a nice day out, so my wife had opened some windows. Suddenly, she heard screaming from the river. It did not sound like fun.

She ran down to the river’s edge and saw a dad and three boys struggling in the water. She phoned me screaming: “They’re drowning! They’re drowning!” I jumped in my truck and drove up our driveway through the yard right down to the river.

My wife was on the phone with 911 at that point, and I could see them about 75-100 yards out. The dad had two of the boys clinging around his neck. They were going under the water and coming up and going under again. The other boy was just floating nearby, face down, motionless.

I threw my shoes and scrubs off and started to walk towards the water. My wife screamed at me, “You’re not going in there!” I said, “I’m not going to stand here and watch this. It’s not going to happen.”

I’m not a kid anymore, but I was a high school swimmer, and to this day I work out all the time. I felt like I had to try something. So, I went in the water despite my wife yelling and I swam towards them.

What happens when you get in that deep water is that you panic. You can’t hear anyone because of the rapids, and your instinct is to swim back towards where you went in, which is against the current. Unless you’re a very strong swimmer, you’re just wasting your time, swimming in place.

But these guys weren’t trying to go anywhere. Dad was just trying to stay up and keep the boys alive. He was in about 10 feet of water. What they didn’t see or just didn’t know: About 20 yards upstream from that deep water is a little island.

When I got to them, I yelled at the dad to move towards the island, “Go backwards! Go back!” I flipped the boy over who wasn’t moving. He was the oldest of the three, around 10 or 11 years old. When I turned him over, he was blue and wasn’t breathing. I put my fingers on his neck and didn’t feel a pulse.

So, I’m treading water, holding him. I put an arm behind his back and started doing chest compressions on him. I probably did a dozen to 15 compressions – nothing. I thought, I’ve got to get some air in this kid. So, I gave him two deep breaths and then started doing compressions again. I know ACLS and CPR training would say we don’t do that anymore. But I couldn’t just sit there and give up. Shortly after that, he coughed out a large amount of water and started breathing.

The dad and the other two boys had made it to the island. So, I started moving towards it with the boy. It was a few minutes before he regained consciousness. Of course, he was unaware of what had happened. He started to scream, because here’s this strange man holding him. But he was breathing. That’s all I cared about.

When we got to the island, I saw that my neighbor downstream had launched his canoe. He’s a retired gentleman who lives next to me, a very physically fit man. He started rolling as hard as he could towards us, against the stream. I kind of gave him a thumbs up, like, “we’re safe now. We’re standing.” We loaded the kids and the dad in the canoe and made it back against the stream to the parking lot where they went in.

All this took probably 10 or 15 minutes, and by then the paramedics were there. Life Flight had been dispatched up by my barn where there’s room to land. So, they drove up there in the ambulance. The boy I revived was flown to the hospital. The others went in the ambulance.

I know all the ED docs, so I talked to somebody later who, with permission from the family, said they were all doing fine. They were getting x-rays on the boy’s lungs. And then I heard the dad and two boys were released that night. The other boy I worked on was observed overnight and discharged the following morning.

Four or 5 days later, I heard from their pediatrician, who also had permission to share. He sent me a very nice note through Epic that he had seen the boys. Besides some mental trauma, they were all healthy and doing fine.

The family lives in the area and the kids go to school 5 miles from my house. So, the following weekend they came over. It was Father’s Day, which was kind of cool. They brought me some flowers and candy and a card the boys had drawn to thank me.

I learned that the dad had brought the boys to the fishing site. They were horsing around in knee deep water. One of the boys walked off a little way and didn’t realize there was a drop off. He went in, and of course the dad went after him, and the other two followed.

I said to the parents: “Look, things like this happen for a reason. People like your son are saved and go on in this world because they’ve got special things to do. I can’t wait to see what kind of man he becomes.”

Two or 3 months later, it was football season, and I got at a message from the dad saying their son was playing football on Saturday at the school. He wondered if I could drop by. So, I kind of snuck over and watched, but I didn’t go say hi. There’s trauma there, and I didn’t want them to have to relive that.

I’m very fortunate that I exercise every day and I know how to do CPR and swim. And thank God the boy was floating when I got to him, or I never would’ve found him. The Maumee River is known as the “muddy Maumee.” You can’t see anything under the water.

Depending on the time of year, the river can be almost dry or overflowing into the parking lot with the current rushing hard. If it had been like that, I wouldn’t have considered going in. And they wouldn’t they have been there in the first place. They’d have been a mile downstream.

I took a risk. I could have gone out there and had the dad and two other kids jump on top of me. Then we all would have been in trouble. But like I told my wife, I couldn’t stand there and watch it. I’m just not that person.

I think it was also about being a dad myself and having grandkids now. Doctor or no doctor, I felt like I was in reasonably good shape and I had to go in there to help. This dad was trying his butt off, but three little kids is too many. You can’t do that by yourself. They were not going to make it.

I go to the hospital and I save lives as part of my job, and I don’t even come home and talk about it. But this is a whole different thing. Being able to save someone’s life when put in this situation is very gratifying. It’s a tremendous feeling. There’s a reason that young man is here today, and I’ll be watching for great things from him.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Daniel Cassavar, MD, is a cardiologist with ProMedica in Perrysburg, Ohio.

Is There a Doctor in the House? is a new series telling these stories.

I live on the Maumee River in Ohio, about 50 yards from the water. I had an early quit time and came home to meet my wife for lunch. Afterward, I went up to my barn across the main road to tinker around. It was a nice day out, so my wife had opened some windows. Suddenly, she heard screaming from the river. It did not sound like fun.

She ran down to the river’s edge and saw a dad and three boys struggling in the water. She phoned me screaming: “They’re drowning! They’re drowning!” I jumped in my truck and drove up our driveway through the yard right down to the river.

My wife was on the phone with 911 at that point, and I could see them about 75-100 yards out. The dad had two of the boys clinging around his neck. They were going under the water and coming up and going under again. The other boy was just floating nearby, face down, motionless.

I threw my shoes and scrubs off and started to walk towards the water. My wife screamed at me, “You’re not going in there!” I said, “I’m not going to stand here and watch this. It’s not going to happen.”

I’m not a kid anymore, but I was a high school swimmer, and to this day I work out all the time. I felt like I had to try something. So, I went in the water despite my wife yelling and I swam towards them.

What happens when you get in that deep water is that you panic. You can’t hear anyone because of the rapids, and your instinct is to swim back towards where you went in, which is against the current. Unless you’re a very strong swimmer, you’re just wasting your time, swimming in place.

But these guys weren’t trying to go anywhere. Dad was just trying to stay up and keep the boys alive. He was in about 10 feet of water. What they didn’t see or just didn’t know: About 20 yards upstream from that deep water is a little island.

When I got to them, I yelled at the dad to move towards the island, “Go backwards! Go back!” I flipped the boy over who wasn’t moving. He was the oldest of the three, around 10 or 11 years old. When I turned him over, he was blue and wasn’t breathing. I put my fingers on his neck and didn’t feel a pulse.

So, I’m treading water, holding him. I put an arm behind his back and started doing chest compressions on him. I probably did a dozen to 15 compressions – nothing. I thought, I’ve got to get some air in this kid. So, I gave him two deep breaths and then started doing compressions again. I know ACLS and CPR training would say we don’t do that anymore. But I couldn’t just sit there and give up. Shortly after that, he coughed out a large amount of water and started breathing.

The dad and the other two boys had made it to the island. So, I started moving towards it with the boy. It was a few minutes before he regained consciousness. Of course, he was unaware of what had happened. He started to scream, because here’s this strange man holding him. But he was breathing. That’s all I cared about.

When we got to the island, I saw that my neighbor downstream had launched his canoe. He’s a retired gentleman who lives next to me, a very physically fit man. He started rolling as hard as he could towards us, against the stream. I kind of gave him a thumbs up, like, “we’re safe now. We’re standing.” We loaded the kids and the dad in the canoe and made it back against the stream to the parking lot where they went in.

All this took probably 10 or 15 minutes, and by then the paramedics were there. Life Flight had been dispatched up by my barn where there’s room to land. So, they drove up there in the ambulance. The boy I revived was flown to the hospital. The others went in the ambulance.

I know all the ED docs, so I talked to somebody later who, with permission from the family, said they were all doing fine. They were getting x-rays on the boy’s lungs. And then I heard the dad and two boys were released that night. The other boy I worked on was observed overnight and discharged the following morning.

Four or 5 days later, I heard from their pediatrician, who also had permission to share. He sent me a very nice note through Epic that he had seen the boys. Besides some mental trauma, they were all healthy and doing fine.

The family lives in the area and the kids go to school 5 miles from my house. So, the following weekend they came over. It was Father’s Day, which was kind of cool. They brought me some flowers and candy and a card the boys had drawn to thank me.

I learned that the dad had brought the boys to the fishing site. They were horsing around in knee deep water. One of the boys walked off a little way and didn’t realize there was a drop off. He went in, and of course the dad went after him, and the other two followed.

I said to the parents: “Look, things like this happen for a reason. People like your son are saved and go on in this world because they’ve got special things to do. I can’t wait to see what kind of man he becomes.”

Two or 3 months later, it was football season, and I got at a message from the dad saying their son was playing football on Saturday at the school. He wondered if I could drop by. So, I kind of snuck over and watched, but I didn’t go say hi. There’s trauma there, and I didn’t want them to have to relive that.

I’m very fortunate that I exercise every day and I know how to do CPR and swim. And thank God the boy was floating when I got to him, or I never would’ve found him. The Maumee River is known as the “muddy Maumee.” You can’t see anything under the water.

Depending on the time of year, the river can be almost dry or overflowing into the parking lot with the current rushing hard. If it had been like that, I wouldn’t have considered going in. And they wouldn’t they have been there in the first place. They’d have been a mile downstream.

I took a risk. I could have gone out there and had the dad and two other kids jump on top of me. Then we all would have been in trouble. But like I told my wife, I couldn’t stand there and watch it. I’m just not that person.

I think it was also about being a dad myself and having grandkids now. Doctor or no doctor, I felt like I was in reasonably good shape and I had to go in there to help. This dad was trying his butt off, but three little kids is too many. You can’t do that by yourself. They were not going to make it.

I go to the hospital and I save lives as part of my job, and I don’t even come home and talk about it. But this is a whole different thing. Being able to save someone’s life when put in this situation is very gratifying. It’s a tremendous feeling. There’s a reason that young man is here today, and I’ll be watching for great things from him.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Daniel Cassavar, MD, is a cardiologist with ProMedica in Perrysburg, Ohio.

Is There a Doctor in the House? is a new series telling these stories.

I live on the Maumee River in Ohio, about 50 yards from the water. I had an early quit time and came home to meet my wife for lunch. Afterward, I went up to my barn across the main road to tinker around. It was a nice day out, so my wife had opened some windows. Suddenly, she heard screaming from the river. It did not sound like fun.

She ran down to the river’s edge and saw a dad and three boys struggling in the water. She phoned me screaming: “They’re drowning! They’re drowning!” I jumped in my truck and drove up our driveway through the yard right down to the river.

My wife was on the phone with 911 at that point, and I could see them about 75-100 yards out. The dad had two of the boys clinging around his neck. They were going under the water and coming up and going under again. The other boy was just floating nearby, face down, motionless.

I threw my shoes and scrubs off and started to walk towards the water. My wife screamed at me, “You’re not going in there!” I said, “I’m not going to stand here and watch this. It’s not going to happen.”

I’m not a kid anymore, but I was a high school swimmer, and to this day I work out all the time. I felt like I had to try something. So, I went in the water despite my wife yelling and I swam towards them.

What happens when you get in that deep water is that you panic. You can’t hear anyone because of the rapids, and your instinct is to swim back towards where you went in, which is against the current. Unless you’re a very strong swimmer, you’re just wasting your time, swimming in place.

But these guys weren’t trying to go anywhere. Dad was just trying to stay up and keep the boys alive. He was in about 10 feet of water. What they didn’t see or just didn’t know: About 20 yards upstream from that deep water is a little island.

When I got to them, I yelled at the dad to move towards the island, “Go backwards! Go back!” I flipped the boy over who wasn’t moving. He was the oldest of the three, around 10 or 11 years old. When I turned him over, he was blue and wasn’t breathing. I put my fingers on his neck and didn’t feel a pulse.

So, I’m treading water, holding him. I put an arm behind his back and started doing chest compressions on him. I probably did a dozen to 15 compressions – nothing. I thought, I’ve got to get some air in this kid. So, I gave him two deep breaths and then started doing compressions again. I know ACLS and CPR training would say we don’t do that anymore. But I couldn’t just sit there and give up. Shortly after that, he coughed out a large amount of water and started breathing.

The dad and the other two boys had made it to the island. So, I started moving towards it with the boy. It was a few minutes before he regained consciousness. Of course, he was unaware of what had happened. He started to scream, because here’s this strange man holding him. But he was breathing. That’s all I cared about.

When we got to the island, I saw that my neighbor downstream had launched his canoe. He’s a retired gentleman who lives next to me, a very physically fit man. He started rolling as hard as he could towards us, against the stream. I kind of gave him a thumbs up, like, “we’re safe now. We’re standing.” We loaded the kids and the dad in the canoe and made it back against the stream to the parking lot where they went in.

All this took probably 10 or 15 minutes, and by then the paramedics were there. Life Flight had been dispatched up by my barn where there’s room to land. So, they drove up there in the ambulance. The boy I revived was flown to the hospital. The others went in the ambulance.

I know all the ED docs, so I talked to somebody later who, with permission from the family, said they were all doing fine. They were getting x-rays on the boy’s lungs. And then I heard the dad and two boys were released that night. The other boy I worked on was observed overnight and discharged the following morning.

Four or 5 days later, I heard from their pediatrician, who also had permission to share. He sent me a very nice note through Epic that he had seen the boys. Besides some mental trauma, they were all healthy and doing fine.

The family lives in the area and the kids go to school 5 miles from my house. So, the following weekend they came over. It was Father’s Day, which was kind of cool. They brought me some flowers and candy and a card the boys had drawn to thank me.

I learned that the dad had brought the boys to the fishing site. They were horsing around in knee deep water. One of the boys walked off a little way and didn’t realize there was a drop off. He went in, and of course the dad went after him, and the other two followed.

I said to the parents: “Look, things like this happen for a reason. People like your son are saved and go on in this world because they’ve got special things to do. I can’t wait to see what kind of man he becomes.”

Two or 3 months later, it was football season, and I got at a message from the dad saying their son was playing football on Saturday at the school. He wondered if I could drop by. So, I kind of snuck over and watched, but I didn’t go say hi. There’s trauma there, and I didn’t want them to have to relive that.

I’m very fortunate that I exercise every day and I know how to do CPR and swim. And thank God the boy was floating when I got to him, or I never would’ve found him. The Maumee River is known as the “muddy Maumee.” You can’t see anything under the water.

Depending on the time of year, the river can be almost dry or overflowing into the parking lot with the current rushing hard. If it had been like that, I wouldn’t have considered going in. And they wouldn’t they have been there in the first place. They’d have been a mile downstream.

I took a risk. I could have gone out there and had the dad and two other kids jump on top of me. Then we all would have been in trouble. But like I told my wife, I couldn’t stand there and watch it. I’m just not that person.

I think it was also about being a dad myself and having grandkids now. Doctor or no doctor, I felt like I was in reasonably good shape and I had to go in there to help. This dad was trying his butt off, but three little kids is too many. You can’t do that by yourself. They were not going to make it.

I go to the hospital and I save lives as part of my job, and I don’t even come home and talk about it. But this is a whole different thing. Being able to save someone’s life when put in this situation is very gratifying. It’s a tremendous feeling. There’s a reason that young man is here today, and I’ll be watching for great things from him.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Daniel Cassavar, MD, is a cardiologist with ProMedica in Perrysburg, Ohio.

How to have a safer and more joyful holiday season

This holiday season, I am looking forward to spending some time with family, as I have in the past. As I have chatted with others, many friends are looking forward to events that are potentially larger and potentially returning to prepandemic type gatherings.

Gathering is important and can bring joy, sense of community, and love to the lives of many. Unfortunately, the risks associated with gathering are not over. as our country faces many cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, and influenza at the same time.

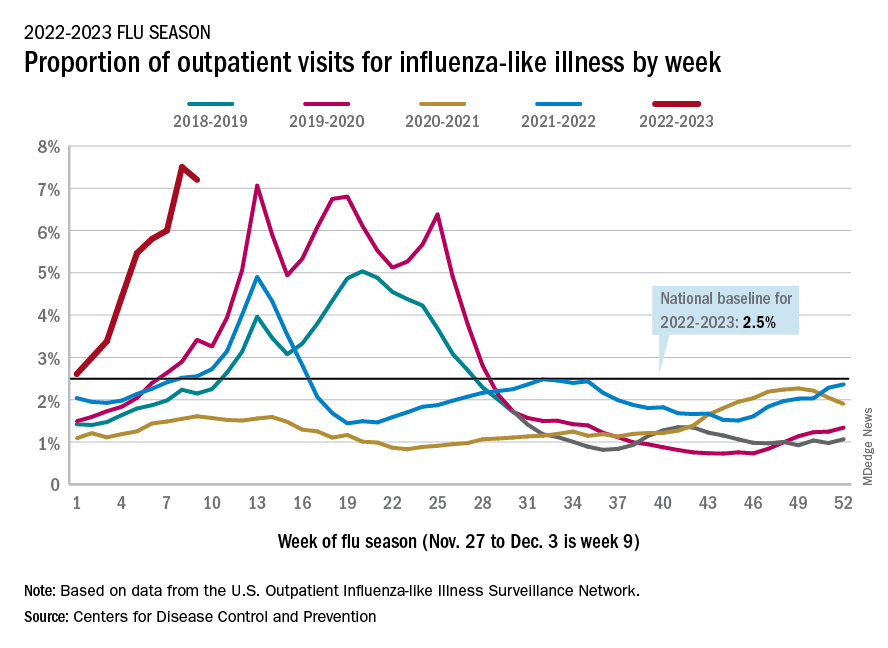

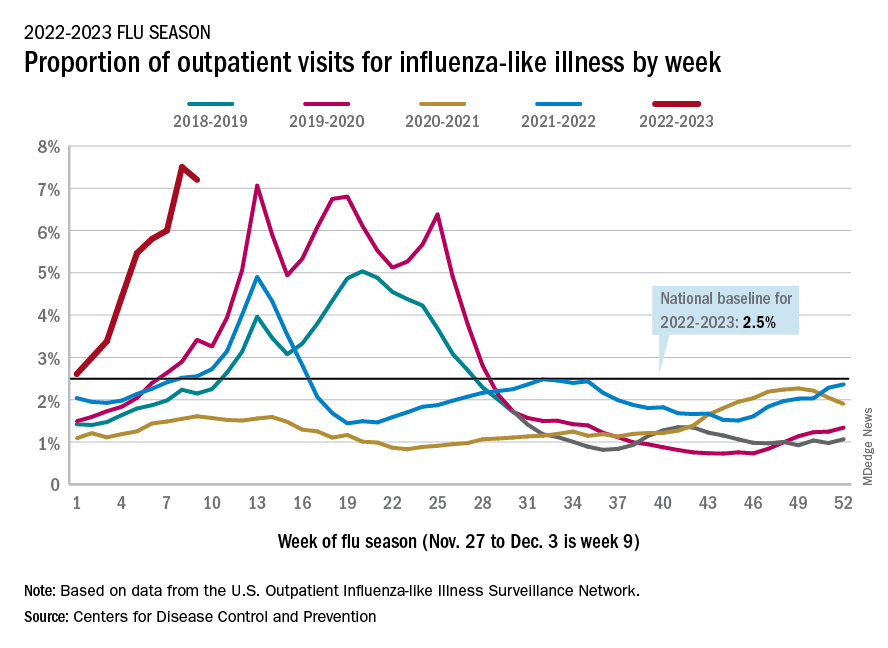

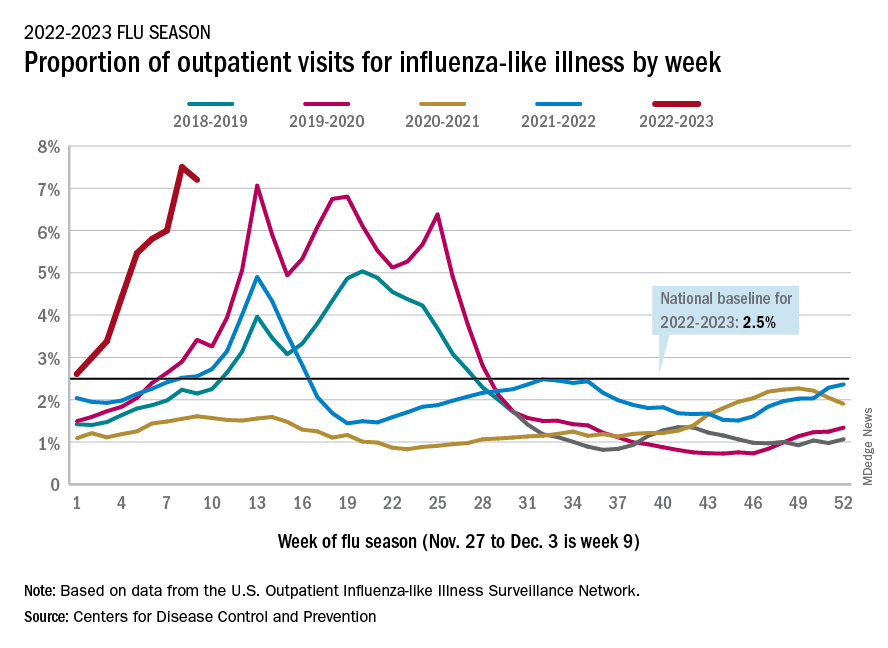

During the first week of December, cases of influenza were rising across the country1 and were rising faster than in previous years. Although getting the vaccine is an important method of influenza prevention and is recommended for everyone over the age of 6 months with rare exception, many have not gotten their vaccine this year.

Influenza

Thus far, “nearly 50% of reported flu-associated hospitalizations in women of childbearing age have been in women who are pregnant.” We are seeing this at a time with lower-than-average uptake of influenza vaccine leaving both the pregnant persons and their babies unprotected. In addition to utilizing vaccines as prevention, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and practicing good hand hygiene can all decrease transmission.

RSV

In addition to rises of influenza, there are currently high rates of RSV in various parts of the country. Prior to 2020, RSV typically started in the fall and peaked in the winter months. However, since the pandemic, the typical seasonal pattern has not returned, and it is unclear when it will. Although RSV hits the very young, the old, and the immunocompromised the most, RSV can infect anyone. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a vaccine for everyone against this virus. Prevention of transmission includes, as with flu, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and washing hands.2

COVID-19

Of course, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also still here as well. During the first week of December, the CDC reported rising cases of COVID across the country. Within the past few months, there have been several developments, though, for protection. There are now bivalent vaccines available as either third doses or booster doses approved for all persons over 6 months of age. As of the first week of December, only 13.5% of those aged 5 and over had received an updated booster.

There is currently wider access to rapid testing, including at-home testing, which can allow individuals to identify if COVID positive. Additionally, there is access to medication to decrease the likelihood of severe disease – though this does not take the place of vaccinations.

If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines including wearing a well-fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.3

With rising cases of all three of these viruses, some may be asking how we can safely gather. There are several things to consider and do to enjoy our events. The first thing everyone can do is to receive updated vaccinations for both influenza and COVID-19 if eligible. Although it may take some time to be effective, vaccination is still one of our most effective methods of disease prevention and is important this winter season. Vaccinations can also help decrease the risk of severe disease.

Although many have stopped masking, as cases rise, it is time to consider masking particularly when community levels of any of these viruses are high. Masks help with preventing and spreading more than just COVID-19. Using them can be especially important for those going places such as stores and to large public gatherings and when riding on buses, planes, or trains.

In summary

Preventing exposure by masking can help keep individuals healthy prior to celebrating the holidays with others. With access to rapid testing, it makes sense to consider testing prior to gathering with friends and family. Most importantly, although we all are looking forward to spending time with our loved ones, it is important to stay home if not feeling well. Following these recommendations will allow us to have a safer and more joyful holiday season.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (flu). [Online] Dec. 1, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm.

2. Respiratory syncytial virus. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). [Online] Oct. 28, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html.

3. COVID-19. [Online] Dec. 7, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

This holiday season, I am looking forward to spending some time with family, as I have in the past. As I have chatted with others, many friends are looking forward to events that are potentially larger and potentially returning to prepandemic type gatherings.

Gathering is important and can bring joy, sense of community, and love to the lives of many. Unfortunately, the risks associated with gathering are not over. as our country faces many cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, and influenza at the same time.

During the first week of December, cases of influenza were rising across the country1 and were rising faster than in previous years. Although getting the vaccine is an important method of influenza prevention and is recommended for everyone over the age of 6 months with rare exception, many have not gotten their vaccine this year.

Influenza

Thus far, “nearly 50% of reported flu-associated hospitalizations in women of childbearing age have been in women who are pregnant.” We are seeing this at a time with lower-than-average uptake of influenza vaccine leaving both the pregnant persons and their babies unprotected. In addition to utilizing vaccines as prevention, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and practicing good hand hygiene can all decrease transmission.

RSV

In addition to rises of influenza, there are currently high rates of RSV in various parts of the country. Prior to 2020, RSV typically started in the fall and peaked in the winter months. However, since the pandemic, the typical seasonal pattern has not returned, and it is unclear when it will. Although RSV hits the very young, the old, and the immunocompromised the most, RSV can infect anyone. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a vaccine for everyone against this virus. Prevention of transmission includes, as with flu, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and washing hands.2

COVID-19

Of course, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also still here as well. During the first week of December, the CDC reported rising cases of COVID across the country. Within the past few months, there have been several developments, though, for protection. There are now bivalent vaccines available as either third doses or booster doses approved for all persons over 6 months of age. As of the first week of December, only 13.5% of those aged 5 and over had received an updated booster.

There is currently wider access to rapid testing, including at-home testing, which can allow individuals to identify if COVID positive. Additionally, there is access to medication to decrease the likelihood of severe disease – though this does not take the place of vaccinations.

If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines including wearing a well-fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.3

With rising cases of all three of these viruses, some may be asking how we can safely gather. There are several things to consider and do to enjoy our events. The first thing everyone can do is to receive updated vaccinations for both influenza and COVID-19 if eligible. Although it may take some time to be effective, vaccination is still one of our most effective methods of disease prevention and is important this winter season. Vaccinations can also help decrease the risk of severe disease.

Although many have stopped masking, as cases rise, it is time to consider masking particularly when community levels of any of these viruses are high. Masks help with preventing and spreading more than just COVID-19. Using them can be especially important for those going places such as stores and to large public gatherings and when riding on buses, planes, or trains.

In summary

Preventing exposure by masking can help keep individuals healthy prior to celebrating the holidays with others. With access to rapid testing, it makes sense to consider testing prior to gathering with friends and family. Most importantly, although we all are looking forward to spending time with our loved ones, it is important to stay home if not feeling well. Following these recommendations will allow us to have a safer and more joyful holiday season.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (flu). [Online] Dec. 1, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm.

2. Respiratory syncytial virus. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). [Online] Oct. 28, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html.

3. COVID-19. [Online] Dec. 7, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

This holiday season, I am looking forward to spending some time with family, as I have in the past. As I have chatted with others, many friends are looking forward to events that are potentially larger and potentially returning to prepandemic type gatherings.

Gathering is important and can bring joy, sense of community, and love to the lives of many. Unfortunately, the risks associated with gathering are not over. as our country faces many cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, and influenza at the same time.

During the first week of December, cases of influenza were rising across the country1 and were rising faster than in previous years. Although getting the vaccine is an important method of influenza prevention and is recommended for everyone over the age of 6 months with rare exception, many have not gotten their vaccine this year.

Influenza

Thus far, “nearly 50% of reported flu-associated hospitalizations in women of childbearing age have been in women who are pregnant.” We are seeing this at a time with lower-than-average uptake of influenza vaccine leaving both the pregnant persons and their babies unprotected. In addition to utilizing vaccines as prevention, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and practicing good hand hygiene can all decrease transmission.

RSV

In addition to rises of influenza, there are currently high rates of RSV in various parts of the country. Prior to 2020, RSV typically started in the fall and peaked in the winter months. However, since the pandemic, the typical seasonal pattern has not returned, and it is unclear when it will. Although RSV hits the very young, the old, and the immunocompromised the most, RSV can infect anyone. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a vaccine for everyone against this virus. Prevention of transmission includes, as with flu, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and washing hands.2

COVID-19

Of course, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also still here as well. During the first week of December, the CDC reported rising cases of COVID across the country. Within the past few months, there have been several developments, though, for protection. There are now bivalent vaccines available as either third doses or booster doses approved for all persons over 6 months of age. As of the first week of December, only 13.5% of those aged 5 and over had received an updated booster.

There is currently wider access to rapid testing, including at-home testing, which can allow individuals to identify if COVID positive. Additionally, there is access to medication to decrease the likelihood of severe disease – though this does not take the place of vaccinations.

If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines including wearing a well-fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.3

With rising cases of all three of these viruses, some may be asking how we can safely gather. There are several things to consider and do to enjoy our events. The first thing everyone can do is to receive updated vaccinations for both influenza and COVID-19 if eligible. Although it may take some time to be effective, vaccination is still one of our most effective methods of disease prevention and is important this winter season. Vaccinations can also help decrease the risk of severe disease.

Although many have stopped masking, as cases rise, it is time to consider masking particularly when community levels of any of these viruses are high. Masks help with preventing and spreading more than just COVID-19. Using them can be especially important for those going places such as stores and to large public gatherings and when riding on buses, planes, or trains.

In summary

Preventing exposure by masking can help keep individuals healthy prior to celebrating the holidays with others. With access to rapid testing, it makes sense to consider testing prior to gathering with friends and family. Most importantly, although we all are looking forward to spending time with our loved ones, it is important to stay home if not feeling well. Following these recommendations will allow us to have a safer and more joyful holiday season.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (flu). [Online] Dec. 1, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm.

2. Respiratory syncytial virus. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). [Online] Oct. 28, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html.

3. COVID-19. [Online] Dec. 7, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

Cardiac injury caused by COVID-19 less common than thought

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

Scientists use mRNA technology for universal flu vaccine

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

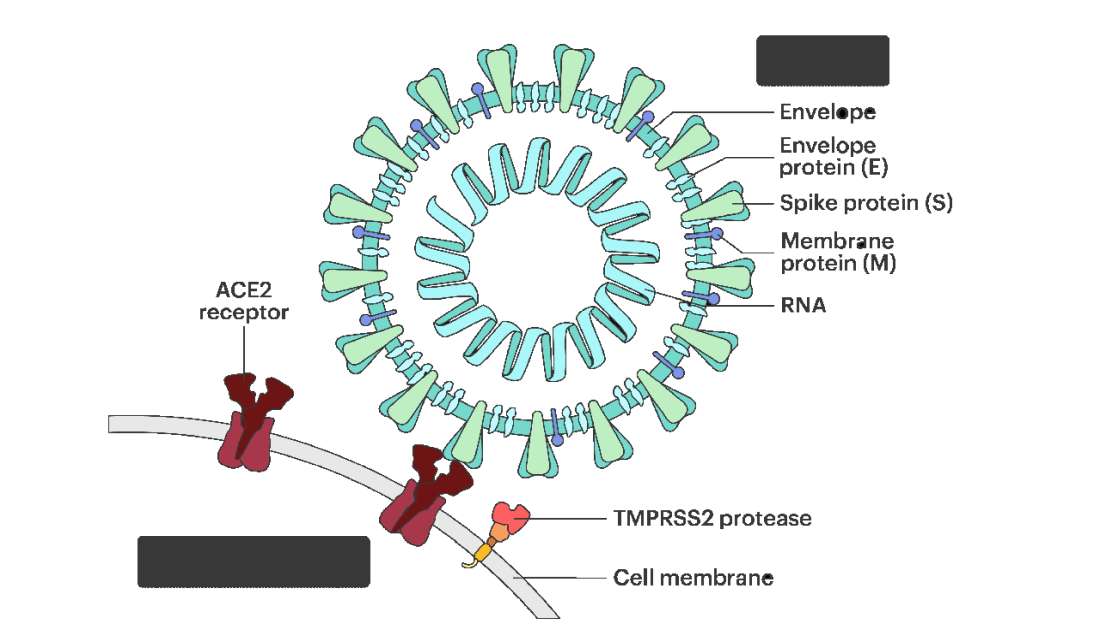

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

COVID booster shot poll: People ‘don’t think they need one’

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.