User login

Worried parents scramble to vaccinate kids despite FDA guidance

One week after reporting promising results from the trial of their COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 5-11, Pfizer and BioNTech announced they’d submitted the data to the Food and Drug Administration. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from discreetly getting their children under age 12 vaccinated.

“The FDA, you never want to get ahead of their judgment,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC on Sept. 28. “But I would imagine in the next few weeks, they will examine that data and hopefully they’ll give the okay so that we can start vaccinating children, hopefully before the end of October.”

Lying to vaccinate now

More than half of all parents with children under 12 say they plan to get their kids vaccinated, according to a Gallup poll.

And although the FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have warned against it, some parents whose children can pass for 12 have lied to get them vaccinated already.

Dawn G. is a mom of two in southwest Missouri, where less than 45% of the population has been fully vaccinated. Her son turns 12 in early October, but in-person school started in mid-August.

“It was scary, thinking of him going to school for even 2 months,” she said. “Some parents thought their kid had a low chance of getting COVID, and their kid died. Nobody expects it to be them.”

In July, she and her husband took their son to a walk-in clinic and lied about his age.

“So many things can happen, from bullying to school shootings, and now this added pandemic risk,” she said. “I’ll do anything I can to protect my child, and a birthdate seems so arbitrary. He’ll be 12 in a matter of weeks. It seems ridiculous that that date would stop me from protecting him.”

In northern California, Carrie S. had a similar thought. When the vaccine was authorized for children ages 12-15 in May, the older of her two children got the shot right away. But her youngest doesn’t turn 12 until November.

“We were tempted to get the younger one vaccinated in May, but it didn’t seem like a rush. We were willing to wait to get the dosage right,” she ssaid. “But as Delta came through, there were no options for online school, the CDC was dropping mask expectations –it seemed like the world was ready to forget the pandemic was happening. It seemed like the least-bad option to get her vaccinated so she could go back to school, and we could find some balance of risk in our lives.”

Adult vs. pediatric doses

For now, experts advise against getting younger children vaccinated, even those who are the size of an adult, because of the way the human immune system develops.

“It’s not really about size,” said Anne Liu, MD, an immunologist and pediatrics professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The immune system behaves differently at different ages. Younger kids tend to have a more exuberant innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that senses danger, even before it has developed a memory response.”

The adult Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine contains 30 mcg of mRNA, while the pediatric dose is just 10 mcg. That smaller dose produces an immune response similar to what’s seen in adults who receive 30 mcg, according to Pfizer.

“We were one of the sites that was involved in the phase 1 trial, a lot of times that’s called a dose-finding trial,” said Michael Smith, MD, a coinvestigator for the COVID vaccine trials done at Duke University. “And basically, if younger kids got a higher dose, they had more of a reaction, so it hurt more. They had fever, they had more redness and swelling at the site of the injection, and they just felt lousy, more than at the lower doses.”

At this point, with Pfizer’s data showing that younger children need a smaller dose, it doesn’t make sense to lie about your child’s age, said Dr. Smith.

“If my two options were having my child get the infection versus getting the vaccine, I’d get the vaccine. But we’re a few weeks away from getting the lower dose approved in kids,” he said. “It’s certainly safer. I don’t expect major, lifelong side effects from the higher dose, but it’s going to hurt, your kid’s going to have a fever, they’re going to feel lousy for a couple days, and they just don’t need that much antigen.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

One week after reporting promising results from the trial of their COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 5-11, Pfizer and BioNTech announced they’d submitted the data to the Food and Drug Administration. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from discreetly getting their children under age 12 vaccinated.

“The FDA, you never want to get ahead of their judgment,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC on Sept. 28. “But I would imagine in the next few weeks, they will examine that data and hopefully they’ll give the okay so that we can start vaccinating children, hopefully before the end of October.”

Lying to vaccinate now

More than half of all parents with children under 12 say they plan to get their kids vaccinated, according to a Gallup poll.

And although the FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have warned against it, some parents whose children can pass for 12 have lied to get them vaccinated already.

Dawn G. is a mom of two in southwest Missouri, where less than 45% of the population has been fully vaccinated. Her son turns 12 in early October, but in-person school started in mid-August.

“It was scary, thinking of him going to school for even 2 months,” she said. “Some parents thought their kid had a low chance of getting COVID, and their kid died. Nobody expects it to be them.”

In July, she and her husband took their son to a walk-in clinic and lied about his age.

“So many things can happen, from bullying to school shootings, and now this added pandemic risk,” she said. “I’ll do anything I can to protect my child, and a birthdate seems so arbitrary. He’ll be 12 in a matter of weeks. It seems ridiculous that that date would stop me from protecting him.”

In northern California, Carrie S. had a similar thought. When the vaccine was authorized for children ages 12-15 in May, the older of her two children got the shot right away. But her youngest doesn’t turn 12 until November.

“We were tempted to get the younger one vaccinated in May, but it didn’t seem like a rush. We were willing to wait to get the dosage right,” she ssaid. “But as Delta came through, there were no options for online school, the CDC was dropping mask expectations –it seemed like the world was ready to forget the pandemic was happening. It seemed like the least-bad option to get her vaccinated so she could go back to school, and we could find some balance of risk in our lives.”

Adult vs. pediatric doses

For now, experts advise against getting younger children vaccinated, even those who are the size of an adult, because of the way the human immune system develops.

“It’s not really about size,” said Anne Liu, MD, an immunologist and pediatrics professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The immune system behaves differently at different ages. Younger kids tend to have a more exuberant innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that senses danger, even before it has developed a memory response.”

The adult Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine contains 30 mcg of mRNA, while the pediatric dose is just 10 mcg. That smaller dose produces an immune response similar to what’s seen in adults who receive 30 mcg, according to Pfizer.

“We were one of the sites that was involved in the phase 1 trial, a lot of times that’s called a dose-finding trial,” said Michael Smith, MD, a coinvestigator for the COVID vaccine trials done at Duke University. “And basically, if younger kids got a higher dose, they had more of a reaction, so it hurt more. They had fever, they had more redness and swelling at the site of the injection, and they just felt lousy, more than at the lower doses.”

At this point, with Pfizer’s data showing that younger children need a smaller dose, it doesn’t make sense to lie about your child’s age, said Dr. Smith.

“If my two options were having my child get the infection versus getting the vaccine, I’d get the vaccine. But we’re a few weeks away from getting the lower dose approved in kids,” he said. “It’s certainly safer. I don’t expect major, lifelong side effects from the higher dose, but it’s going to hurt, your kid’s going to have a fever, they’re going to feel lousy for a couple days, and they just don’t need that much antigen.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

One week after reporting promising results from the trial of their COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 5-11, Pfizer and BioNTech announced they’d submitted the data to the Food and Drug Administration. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from discreetly getting their children under age 12 vaccinated.

“The FDA, you never want to get ahead of their judgment,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC on Sept. 28. “But I would imagine in the next few weeks, they will examine that data and hopefully they’ll give the okay so that we can start vaccinating children, hopefully before the end of October.”

Lying to vaccinate now

More than half of all parents with children under 12 say they plan to get their kids vaccinated, according to a Gallup poll.

And although the FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have warned against it, some parents whose children can pass for 12 have lied to get them vaccinated already.

Dawn G. is a mom of two in southwest Missouri, where less than 45% of the population has been fully vaccinated. Her son turns 12 in early October, but in-person school started in mid-August.

“It was scary, thinking of him going to school for even 2 months,” she said. “Some parents thought their kid had a low chance of getting COVID, and their kid died. Nobody expects it to be them.”

In July, she and her husband took their son to a walk-in clinic and lied about his age.

“So many things can happen, from bullying to school shootings, and now this added pandemic risk,” she said. “I’ll do anything I can to protect my child, and a birthdate seems so arbitrary. He’ll be 12 in a matter of weeks. It seems ridiculous that that date would stop me from protecting him.”

In northern California, Carrie S. had a similar thought. When the vaccine was authorized for children ages 12-15 in May, the older of her two children got the shot right away. But her youngest doesn’t turn 12 until November.

“We were tempted to get the younger one vaccinated in May, but it didn’t seem like a rush. We were willing to wait to get the dosage right,” she ssaid. “But as Delta came through, there were no options for online school, the CDC was dropping mask expectations –it seemed like the world was ready to forget the pandemic was happening. It seemed like the least-bad option to get her vaccinated so she could go back to school, and we could find some balance of risk in our lives.”

Adult vs. pediatric doses

For now, experts advise against getting younger children vaccinated, even those who are the size of an adult, because of the way the human immune system develops.

“It’s not really about size,” said Anne Liu, MD, an immunologist and pediatrics professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The immune system behaves differently at different ages. Younger kids tend to have a more exuberant innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that senses danger, even before it has developed a memory response.”

The adult Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine contains 30 mcg of mRNA, while the pediatric dose is just 10 mcg. That smaller dose produces an immune response similar to what’s seen in adults who receive 30 mcg, according to Pfizer.

“We were one of the sites that was involved in the phase 1 trial, a lot of times that’s called a dose-finding trial,” said Michael Smith, MD, a coinvestigator for the COVID vaccine trials done at Duke University. “And basically, if younger kids got a higher dose, they had more of a reaction, so it hurt more. They had fever, they had more redness and swelling at the site of the injection, and they just felt lousy, more than at the lower doses.”

At this point, with Pfizer’s data showing that younger children need a smaller dose, it doesn’t make sense to lie about your child’s age, said Dr. Smith.

“If my two options were having my child get the infection versus getting the vaccine, I’d get the vaccine. But we’re a few weeks away from getting the lower dose approved in kids,” he said. “It’s certainly safer. I don’t expect major, lifelong side effects from the higher dose, but it’s going to hurt, your kid’s going to have a fever, they’re going to feel lousy for a couple days, and they just don’t need that much antigen.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Mobile Integrated Health: Reducing Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Hospitalizations Through Novel Outpatient Care Initiatives

From the Mobile Integrated Health and Emergency Medicine Department, South Shore Health, Weymouth, MA.

Objective: To develop a process through which Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) can treat patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at high risk for readmission in an outpatient setting. In turn, South Shore Hospital (SSH) looks to leverage MIH to improve hospital flow, decrease costs, and improve patient quality of life.

Methods: With the recent approval of hospital-based MIH programs in Massachusetts, SSH used MIH to target specific patient demographics in an at-home setting. Here, we describe the planning and implementation of this program for patients with COPD. Key components to success include collaboration among providers, early follow-up visits, patient education, and in-depth medical reconciliations. Analysis includes a retrospective examination of a structured COPD outpatient pathway.

Results: A total of 214 patients with COPD were treated with MIH from March 2, 2020, to August 1, 2021. Eighty-seven emergent visits were conducted, and more than 650 total visits were made. A more intensive outpatient pathway was implemented for patients deemed to be at the highest risk for readmission by pulmonary specialists.

Conclusion: This process can serve as a template for future institutions to treat patients with COPD using MIH or similar hospital-at-home services.

Keywords: Mobile Integrated Health; MIH; COPD; population health.

It is estimated that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects more than 16 million Americans1 and accounts for more than 700 000 hospitalizations each year in the US.2 Thirty-day COPD readmission rates hover around 22.6%,3 and readmission within 90 days of initial discharge can jump to between 31% and 35%.4 This is the highest of any patient demographic, and more than half of these readmissions are due to COPD. To counter this, government and state entities have made nationwide efforts to encourage health systems to focus on preventing readmissions. In October 2014, the US added COPD to the active list of diseases in Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), later adding COPD to various risk-based bundle programs that hospitals may choose to opt into. These programs are designed to reduce all-cause readmissions after an acute exacerbation of COPD, as the HRRP penalizes hospitals for all-cause 30-day readmissions.3 However, what is most troubling is that, despite these efforts, readmission rates have not dropped in the past decade.5 COPD remains the third leading cause of death in America and still poses a significant burden both clinically and economically to hospitals across the country.3

A solution that is gaining traction is to encourage outpatient care initiatives and discharge pathways. Early follow-up is proven to decrease chances of readmission, and studies have shown that more than half of readmitted patients did not follow up with a primary care physician (PCP) within 30 days of their initial discharge.6 Additionally, large meta-analyses show hospital-at-home–type programs can lead to reductions in mortality, decrease costs, decrease readmissions, and increase patient satisfaction.7-9 Therefore, for more challenging patient populations with regard to readmissions and mortality, Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) may be the solution that we are looking for.

This article presents a viable process to treat patients with COPD in an outpatient setting with MIH Services. It includes an examination of what makes MIH successful as well as a closer look at a structured COPD outpatient pathway.

Methods

South Shore Hospital (SSH) is an independent, not-for-profit hospital located in Weymouth, Massachusetts. It is host to 400 beds, 100 000 annual visits to the emergency department (ED), and its own emergency medical services program. In March 2020, SSH became the first Massachusetts hospital-based program to acquire an MIH license. MIH paramedics receive 300 hours of specialized training, including time in clinical clerkships shadowing pulmonary specialists, cardiology/congestive heart failure (CHF) providers, addiction medicine specialists, home care and care progression colleagues, and wound center providers. Specialist providers become more comfortable with paramedic capabilities as a result of these clerkships, improving interactions and relationships going forward. At the time of writing, SSH MIH is staffed by 12 paramedics, 4 of whom are full time; 2 medical directors; 2 internal coordinators; and 1 registered nurse (RN). A minimum of 2 paramedics are on call each day, each with twice-daily intravenous (IV) capabilities. The first shift slot is 16 hours, from 7:00 AM to 11:00

The goal of developing MIH is to improve upon the current standard of care. For hospitals without MIH capabilities, there are limited options to treat acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) patients postdischarge. It is common for the only outpatient referral to be a lone PCP visit, and many patients who need more extensive treatment options don’t have access to a timely PCP follow-up or resources for alternative care. This is part of why there has been little improvement in the 21st century with regard to reducing COPD hospitalizations. As it stands, approximately 10% to 55% of all AECOPD readmissions are preventable, and more than one-fifth of patients with COPD are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge.3 In response, MIH has been designed to provide robust care options postdischarge in the patient home, with the eventual goal of reducing preventable hospitalizations and readmissions for all patients with COPD.

Patient selection

Patients with COPD are admitted to the MIH program in 1 of 3 ways: (1) directly from the ED; (2) at discharge from inpatient care; or (3) from a SSH affiliate referral.

With option 1, the ED physician assesses patient need for MIH services and places a referral to MIH in the electronic medical record (EMR). The ED provider also specifies whether follow-up is “urgent” and sets an alternative level of priority if not. With option 2, the inpatient provider and case manager follow a similar process, first determining whether a patient is stable enough to go home with outpatient services and then if MIH would be beneficial to the patient. If the patient is discharged home, a follow-up visit by an MIH paramedic is scheduled within 48 hours. With option 3, the patient is referred to MIH by an affiliate of SSH. This can be through the patient’s PCP, their visiting nurse association (VNA) service provider, or through any SSH urgent care center. In all 3 referral processes, the patient has the option to consent into the program or refuse services. Once referred, MIH coordinators review patients on a case-by-case basis. Patients with a history of prior admissions are given preference, with the goal being to keep the frailer, older, and comorbid patients at home. Other considerations include recent admission(s), length of stay, and overall stability. Social factors considered by the team include whether the patient lives alone and has alternative home services and the patient’s total distance from the hospital. Patients with a history of violence, mental health concerns, or substance abuse go through a more extensive screening process to ensure paramedic safety.

Given their patient profile and high hospital usage rates, MIH is sometimes requested for patients with end-stage COPD. Many of these patients benefit from MIH goals-of-care conversations to ensure they understand all their options and choose an approach that fits their preferences. In these cases, MIH has been instrumental in assisting patients and families with completing Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment and health care proxy forms and transitioning patients to palliative care, hospice, advanced-illness care management programs, or other long-term care options to prevent the need for rehospitalization. The MIH team focuses heavily on providing quality end-of-life care for patients and aligning care models with patient and family goals, often finding that having these sensitive conversations in the comfort of home enables transparency and comfort not otherwise experienced by hospitalized patients.

Initial patient follow-up

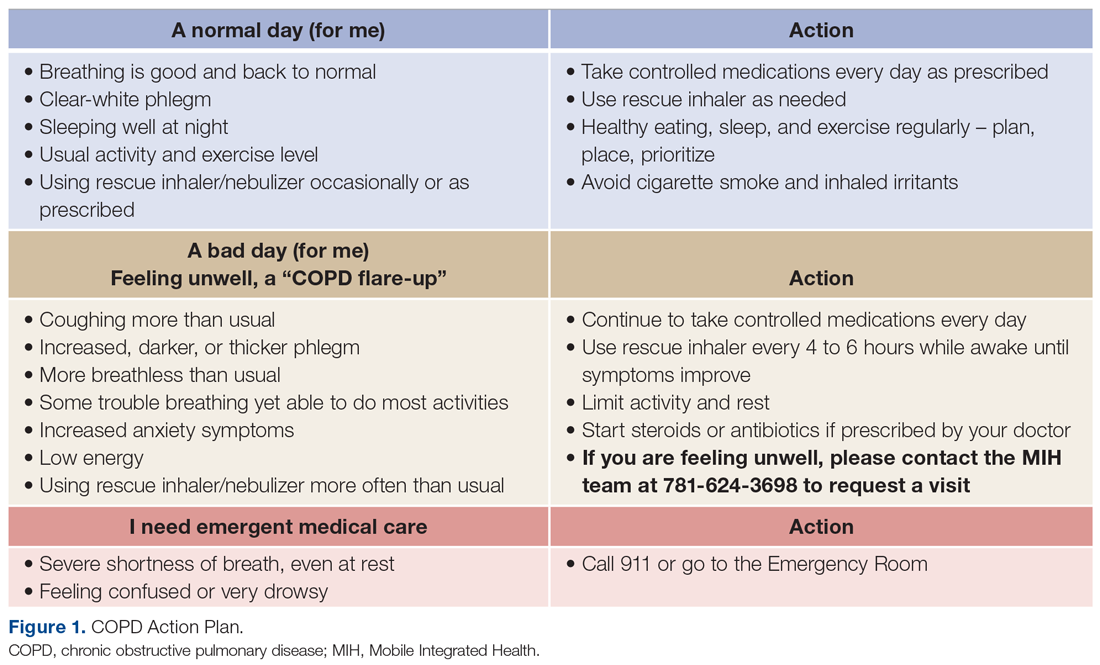

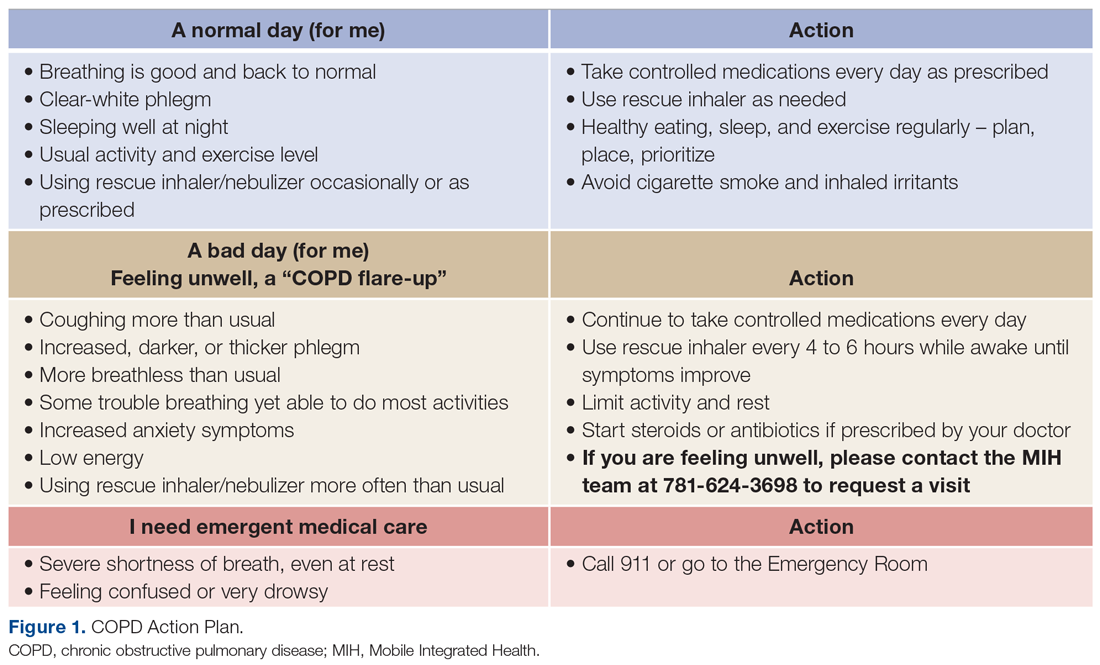

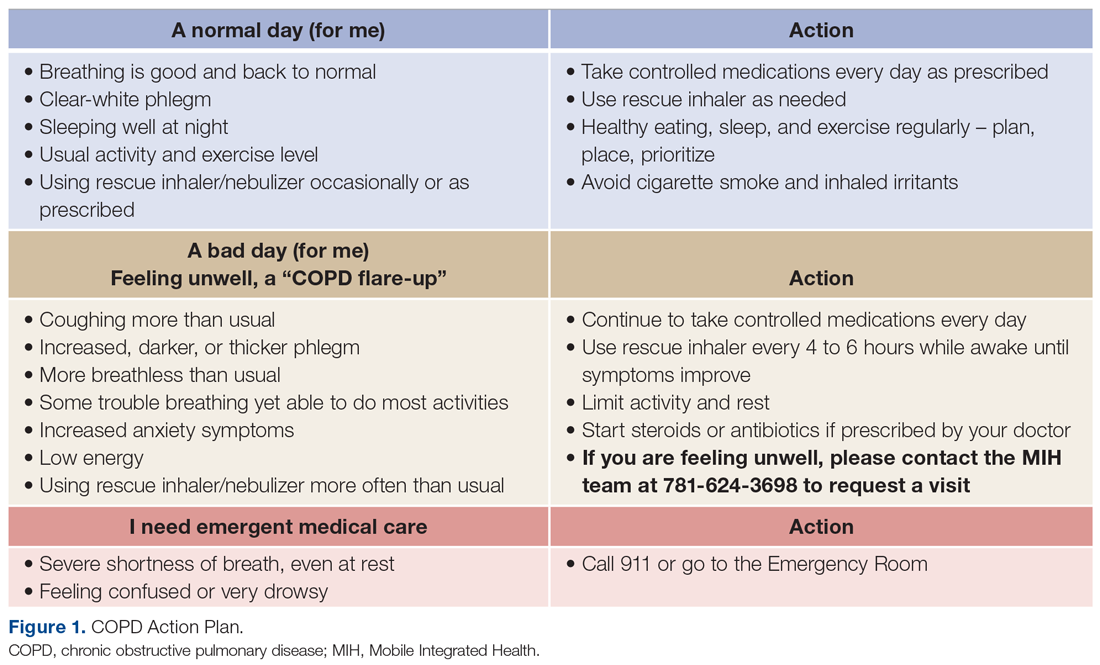

For patients with COPD enrolled in the MIH program, their first patient visit is scheduled within 48 hours of discharge from the ED or inpatient hospital. In many cases, this visit can be conducted within 24 hours of returning home. Once at the patient’s home, the paramedic begins with general introductions, vital signs, and a basic physical examination. The remainder of the visit focuses on patient education and symptom recognition. The paramedic reviews the COPD action plan (Figure 1), including how to recognize the onset of a “COPD flare-up” and the appropriate response. Patients are provided with a paper copy of the action plan for future reference.

The next point of educational emphasis is the patient’s individual medication regimen. This involves differentiating between control (daily) and rescue medications, how to use oxygen tanks, and how to safely wean off of oxygen. Specific attention is given to how to use a metered-dose inhaler, as studies have found that more than half of all patients use their inhaler devices incorrectly.10

Paramedics also complete a home safety evaluation of the patient’s residence, which involves checking for tripping hazards, lighting, handrails, slippery surfaces, and general access to patient medication. If an issue cannot be resolved by the paramedic on site and is considered a safety hazard, it is reported back to the hospital team for assistance.

Finally, patients are educated on the capabilities of MIH as a program and what to expect when they reach out over the phone. Patients are given a phone number to call for both “urgent” and “nonemergent” situations. In both cases, they will be greeted by one of the MIH coordinators or nurses who assist with triaging patient symptoms, scheduling a visit, or providing other guidance. It is a point of emphasis that the patient can use MIH for more than just COPD and should call in the event of any illness or discomfort (eg, dehydration, fever) in an effort to prevent unnecessary ED visits.

Medication reconciliation

Patients with COPD often have complex medication regimens. To help alleviate any confusion, medication reconciliations are done in conjunction with every COPD patient’s initial visit. During this process, the paramedic first takes an inventory of all medications in the patient home. Common reasons for nonadherence include confusing packaging, inability to reach the pharmacy, or medication not being covered by insurance. The paramedic reconciles the updated medication regimen against the medications that are physically in the home. Once the initial review is complete, the paramedic teleconferences with a registered hospitalist pharmacist (RHP) for a more in-depth review. Over video chat, the RHP reviews each medication individually to make sure the patient understands how many times per day they take each medication, whether it is a control or rescue medication, and what times of the day to take them. The RHP will then clarify any other medication questions the patient has, assure all recent medications have been picked up from the pharmacy, and determine any barriers, such as cost or transportation.

Follow-ups and PCP involvement

At each in-person visit, paramedics coordinate with an advanced practice clinician (APC) through telehealth communication. On these video calls with a provider, the paramedic relays relevant information pertaining to patient history, vital signs, and current status. Any concerning findings, symptoms of COPD flare-ups, or recent changes in status will be discussed. The APC then speaks directly to the patient to gather additional details about their condition and any recent hospitalizations, with their primary role being to make clinical decisions on further treatment. For the COPD population, this often includes orders for the MIH paramedic to administer IV medication (ie, IV methylprednisolone or other corticosteroids), antibiotics, home nebulizers, and at-home oxygen.

Second and third follow-up paramedic visits are often less intensive. Although these visits often still involve telehealth calls to the APC, the overall focus shifts toward medication adherence, ED avoidance, and readmission avoidance. On these visits, the paramedic also checks vitals, conducts a physical examination, and completes follow-up testing or orders per the APC.

PCP involvement is critical to streamlining and transitioning patient care. Patients who are admitted to MIH without insurance or a PCP are assisted in the process of finding one. PCPs automatically receive a patient enrollment letter when their patient is seen by an MIH paramedic. Following each individual visit, paramedic and APC notes are sent to the PCP through the EMR or via fax, at which time the PCP may be consulted on patient history and/or future care decisions. After the transition back to care by their PCP, patients are still encouraged to utilize MIH if acute changes arise. If a patient is readmitted back to the hospital, MIH is automatically notified, and coordinators will assess whether there is continued need for outpatient services or areas for potential improvement.

Emergent MIH visits

While MIH visits with patients with COPD are often scheduled, MIH can also be leveraged in urgent situations to prevent the need for a patient to come to the ED or hospital. Patients with COPD are told to call MIH if they have worsening symptoms or have exhausted all methods of self-treatment without an improvement in status. In this case, a paramedic is notified and sent to the patient’s home at the earliest time possible. The paramedic then completes an assessment of the patient’s status and relays information to the MIH APC or medical director. From there, treatment decisions, such as starting the patient on an IV, using nebulizers, or doing an electrocardiogram for diagnostic purposes, are guided by the provider team with the ultimate goal of caring for the patient in the home. For our population, providing urgent care in the home has proven to be an effective way to avoid unnecessary readmissions while still ensuring high-quality patient care.

Outpatient pathway

In May 2021, select patients with COPD were given the option to participate in a more intensive MIH outpatient pathway. Pilot patients were chosen by 2 pulmonary specialists, with a focus on enrolling patients with COPD at the highest risk for readmission. Patients who opted in were followed by MIH for a total of 30 days.

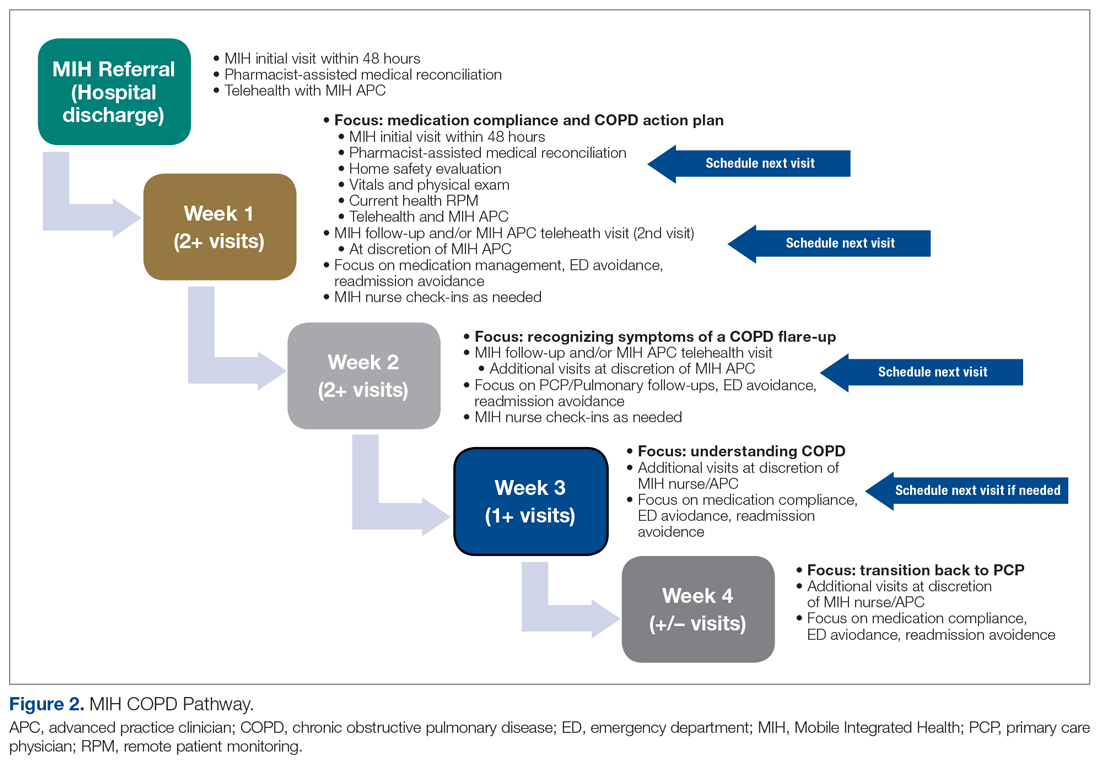

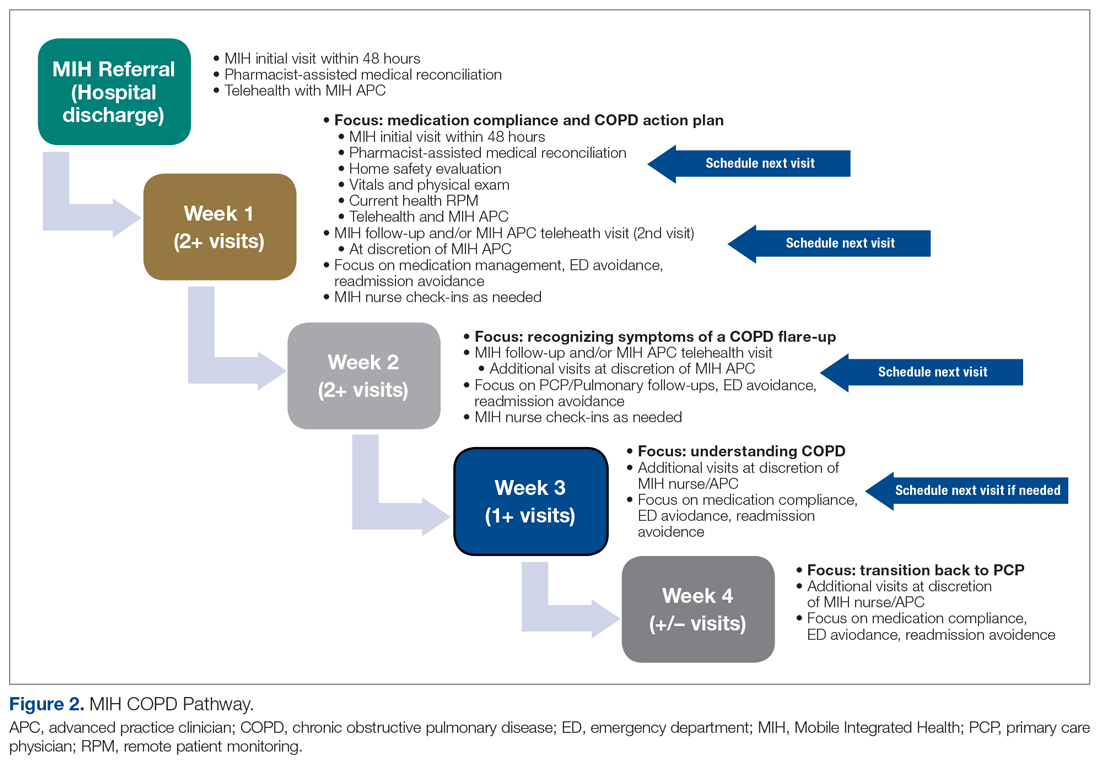

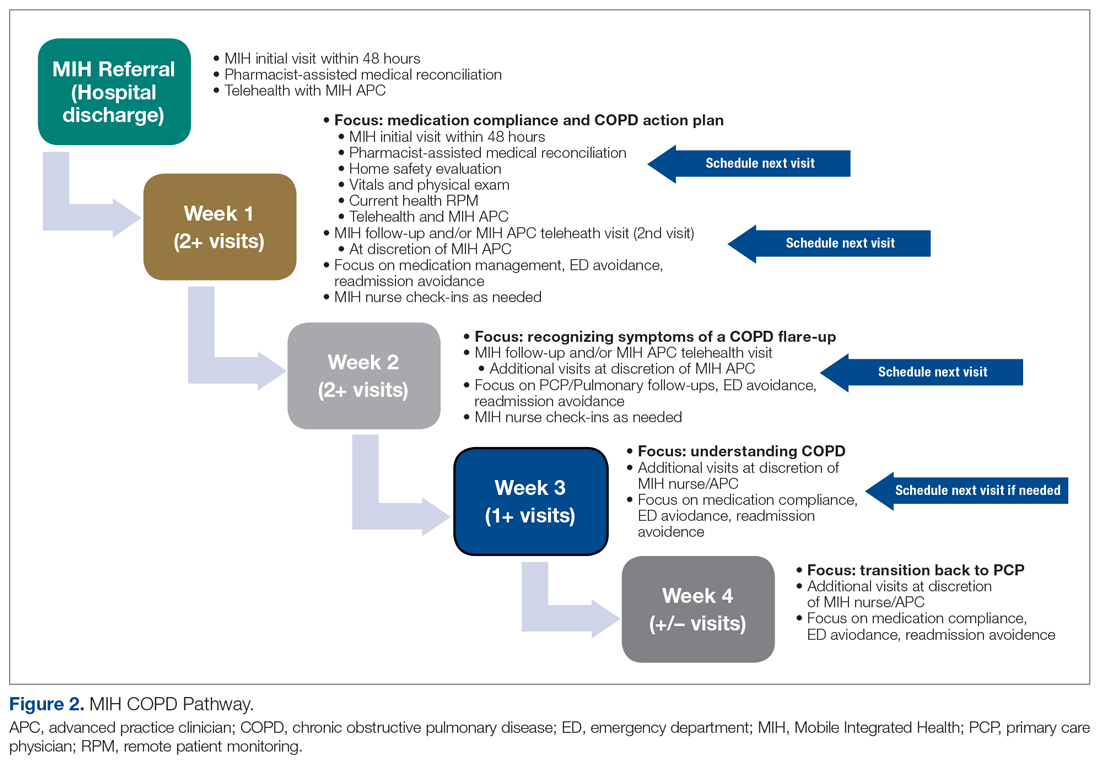

The first visit was made as usual within 48 hours of discharge. Patients received education, medication reconciliation, vitals examination, home safety evaluation, and a facilitated telehealth evaluation with the APC. What differentiates the pathway from standard MIH services is that after the first visit, the follow-ups are prescheduled and more numerous. This is outlined best in Figure 2, which serves as a guideline for coordinators and paramedics in the cadence and focus of visits for each patient on the pathway. The initial 2 weeks are designed to check in on the patient in person and ensure active recovery. The latter 2 weeks are designed to ensure that the patient follows up with their care team and understands their medications and action plan going forward. Pathway patients were also monitored using a remote patient monitoring (RPM) kit. On the initial visit, paramedics set up the RPM equipment and provided a demonstration on how to use each device. Patients were issued a Bluetooth-enabled scale, blood pressure cuff, video-enabled tablet, and wearable device. The wearable device continuously recorded respiration rate, heart rate, and oxygen saturation and had fall-detection enabled. Over the course of a month, an experienced MIH nurse monitored the vitals transmitted by the wearable device and checked patient weight and blood pressure 1 to 2 times per day, utilizing these data to proactively outreach to patients if abnormalities occurred. Prior to the start of the program, the MIH nurse contacted each patient to introduce herself and notify them that they would receive a call if any vitals were unusual.

Results

MIH treated 214 patients with COPD from March 2, 2020, to August 2, 2021. In total, paramedics made more than 650 visits. Eighty-seven of these were documented as urgent visits with AECOPD, shortness of breath, cough, or wheezing as the primary concern.

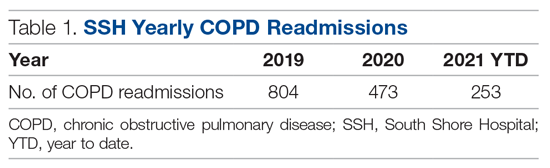

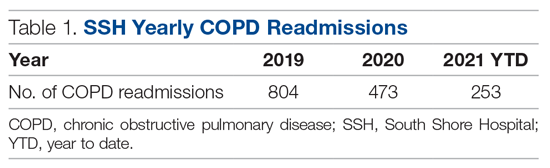

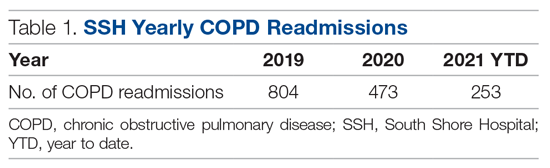

In the calendar year of 2019, our institution admitted 804 patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD. In 2020, the first year with MIH, total COPD admissions decreased to 473; however, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be discounted. At of the time of writing—219 days into 2021—253 patients with COPD have been admitted thus far (Table 1).

Pathway results

Sixteen patients were referred to the MIH COPD Discharge Pathway Pilot during May 2021. Ten patients went on to complete the entire 30-day pathway. Six did not finish the program. Three of these 6 patients were referred by a pulmonary specialist for enrollment but not ultimately referred to the pilot program by case management and therefore not enrolled. The other 3 of the 6 patients who did not complete the pilot program were enrolled but discontinued owing to noncompliance.

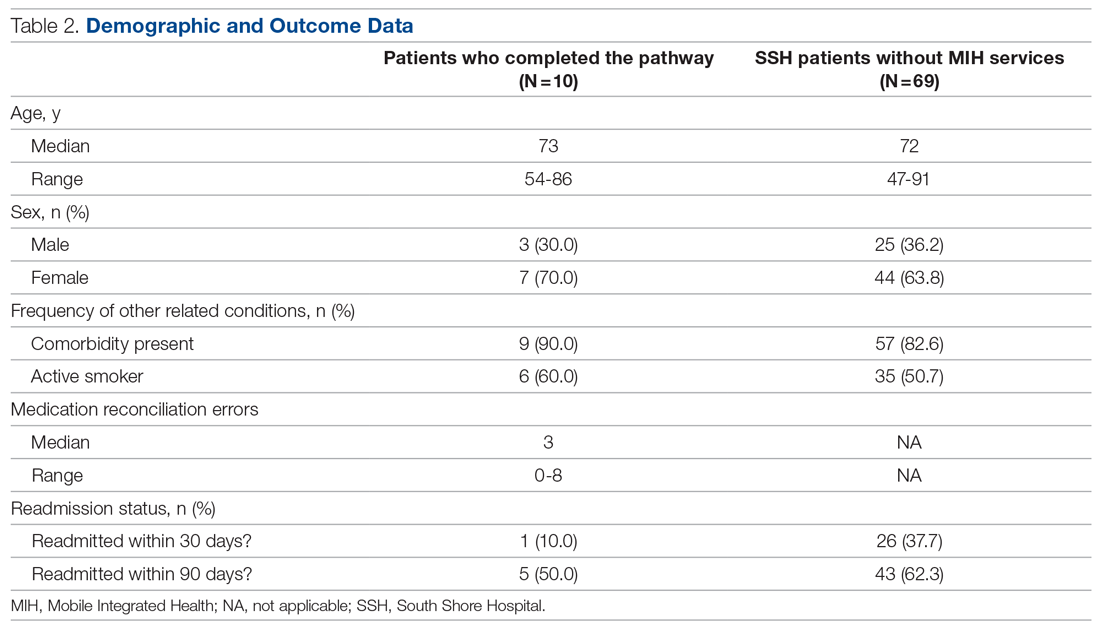

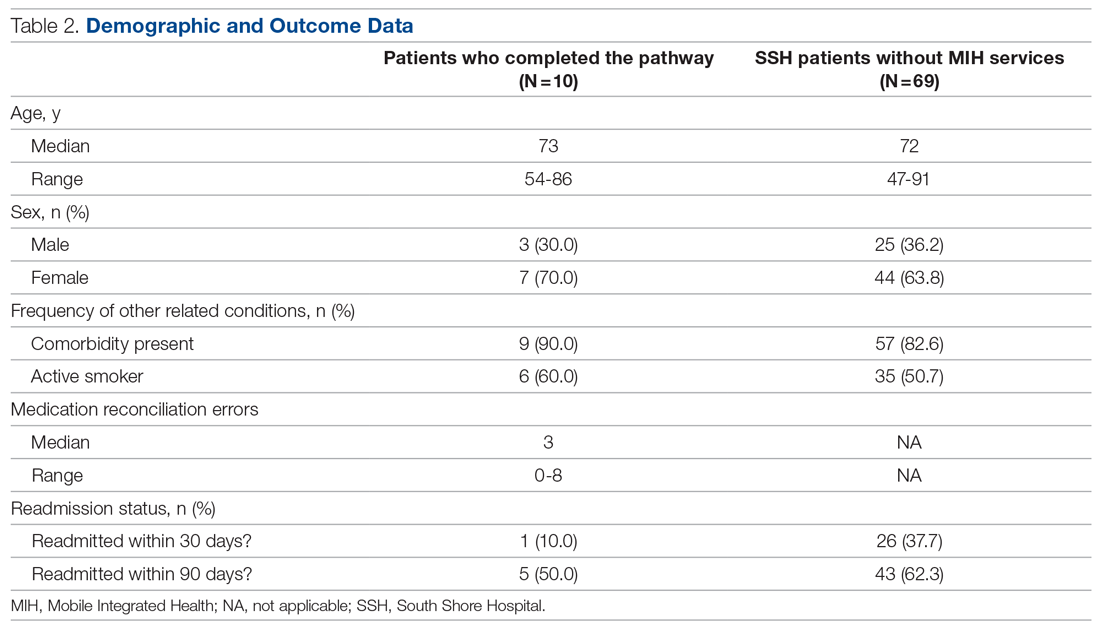

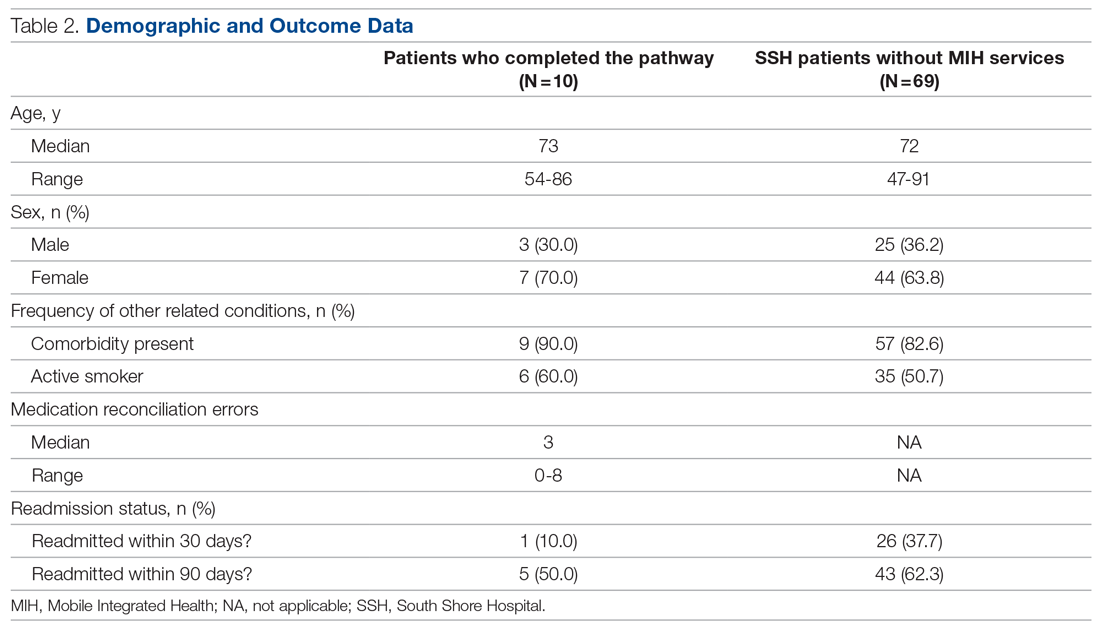

Of the 10 patients who completed the pathway, 3 patients were male, and 7 were female. Ages ranged from 55 to 84 years. On average, the RHP found 3.6 medication reconciliation errors per patient. One patient was readmitted within 30 days (only 3 days after the initial discharge), and 5 were readmitted within 90 days.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients with COPD who were not provided with MIH services and were admitted to our hospital between September 1, 2020, and March 1, 2021, for comparison. Age, sex, and other related conditions are shown in Table 2. Medication reconciliation error data were not tracked for this demographic, as they did not have an in-home medication reconciliation completed.

Discussion

MIH has treated 214 patients with COPD from March 2, 2020, to August 2, 2021, a 17-month period. In that same timeframe, the hospital experienced a 42% decrease in COPD admissions. Although this effect is not the sole product of MIH (specifically, COVID-19 caused a drop in all-cause hospital admissions), we believe MIH did play a small role in this reduction. Eighty-seven emergent visits were conducted for patients with a primary complaint of AECOPD, shortness of breath, cough, or wheezing. On these visits, MIH provided urgent treatment to prevent the patient returning to the ED and potentially leading to readmission.

The program’s impact extends beyond the numbers. With more than 200 patients with COPD treated at home, we improved hospital flow, shortened patients’ overall length of stay, and increased capacity in the ED and inpatient units. In addition, MIH has been able to fill in care gaps present in the current health care system by providing acute care in the home to patients who otherwise have access-to-care and transportation issues.

What made the program successful

With the COPD population prone to having complex medication regimens, medication reconciliations were critical to improving patient outcomes. During the documented medication reconciliations for pathway patients, 8 of 10 patients had medication errors identified. Some of the more common errors included incorrect inhaler usage, patient medication not arriving to the pharmacy for a week or more after discharge, prescribed medication dosages that were too high or too low, and a lack of transportation to pick up the patient’s prescription. Even more problematic is that 7 of these 8 patients required multiple interventions to correct their regimen. What was cited as most beneficial by both the paramedic and the RHP was taking time to walk through each medication individually and ensuring that the patient could recite back how often and when they should be using it. What also proved to be helpful was spending extra time on the inhalers and nebulizers. Multiple patients did not know how to use them properly and/or cited a history of struggling with them.

The MIH COPD pathway patients showed encouraging preliminary results. In the initial 30-day window, only 1 of 10 (10%) patients was readmitted, which is lower than the 37.7% rate for comparable patients who did not have MIH services. This could imply that patients with COPD respond positively to active and consistent management with predetermined points of contact. Ninety-day readmission rates jumped to 5 of 10, with 4 of these patients being readmitted multiple times. Approximately half of these readmissions were COPD related. It is important to remember that the patients being targeted by the pathway are deemed to be at very high risk of readmission. As such, one could expect that even with a successful reduction in rates, pathway patient readmission rates may be slightly elevated compared with national COPD averages.

Given the more personalized and at-home care, patients also expressed higher levels of care satisfaction. Most patients want to avoid the hospital at all costs, and MIH provides a safe and effective alternative. Patients with COPD have also relayed that the education they receive on their medication, disease, and how to use MIH has been useful. This is reflected in the volume of urgent calls that MIH receives. A patient calling MIH in place of 911 shows not only that the patient has a level of trust in the MIH team, but also that they have learned how to recognize symptoms earlier to prevent major flare-ups.

This study had several limitations. On the pilot pathway, 3 patients were removed from MIH services because of repeated noncompliance. These instances primarily involved aggression toward the paramedics, both verbal and physical, as well as refusal to allow the MIH paramedics into the home. Going forward, it will be valuable to have a screening process for pathway patients to determine likelihood of compliance. This could include speaking to the patient’s PCP or other in-hospital providers before accepting them into the program.

Remote patient monitoring also presented its challenges. Despite extensive equipment demonstrations, some patients struggled to grasp the technology. Some of the biggest problems cited were confusion operating the tablet, inability to charge the devices, and issues with connectivity. In the future, it may be useful to simplify the devices even more. Further work should also be done to evaluate the efficacy of remote patient technology in this specific setting, as studies have shown varied results with regard to RPM success. In 1 meta-analysis of 91 different published studies that took place between 2015 and 2020, approximately half of the RPM studies resulted in no change in hospital readmissions, length of stay, or ED presentations, while the other half saw improvement in these categories.11 We suspect that the greatest benefits of our work came from the patient education, trust built over time, in-home urgent evaluations, and 1-on-1 time with the paramedic.

With many people forgoing care during the pandemic, COVID-19 has also caused a downward trend in overall and non-COVID-19 admissions. In a review of more than 500 000 ED visits in Massachusetts between March 11, 2020, and September 8, 2021, there was a 32% decrease in admissions when compared with those same weeks in 2019.10 There was an even greater drop-off when it came to COPD and other respiratory-related admissions. In evaluating the impact SSH MIH has made, it is important to recognize that the pandemic contributed to reducing total COPD admissions. Adding merit to the success of MIH in contributing to the reduction in admissions is the continued downward trend in total COPD admissions year-to-date in 2021. Despite total hospital usage rates increasing at our institution over the course of this year, the overall COPD usage rates have remained lower than before.

Another limitation is that in the selection of patients, both for general MIH care and for the COPD pathway, there was room for bias. The pilot pathway was offered specifically to patients at the highest risk for readmission; however, patients were referred at the discretion of our pulmonologist care team and not selected by any standardized rubric. Additionally, MIH only operates on a 16-hour schedule. This means that patients admitted to the ED or inpatient at night may sometimes be missed and not referred to MIH for care.

The biggest caveat to the pathway results is, of course, the small sample size. With only 10 patients completing the pilot, it is impossible to come to any concrete conclusions. Such an intensive pathway requires dedicating large amounts of time and resources, which is why the pilot was small. However, considering the preliminary results, the outline given could provide a starting point for future work to evaluate a similar COPD pathway on a larger scale.

Future considerations

Risk stratification of patients is critical to achieving even further reductions in readmissions and mortality. Hospitals can get the most value from MIH by focusing on patients with COPD at the highest risk for return, and it would be valuable to explicitly define who fits into this criterion. Utilizing a tool similar to the LACE index for readmission but tailoring it to patients with COPD when admitting patients into the program would be a logical next step.

Reducing the points of patient contact could also prove valuable. Over the course of a patient’s time with MIH, they interact with an RHP, APC, paramedic, RN, and discharging hospitalist. Additionally, we found many patients had VNA services, home health aides, care managers, and/or social workers involved in their care. Some patients found this to be stressful and overwhelming, especially regarding the number of outreach calls soon after discharge.

It would also be useful to look at the impact of MIH on total COPD admissions independent of the artificial variation created by COVID-19. This may require waiting until there are higher levels of vaccination and/or finding ways to control for the potential variation. In doing so, one could look at the direct effect MIH has on COPD readmissions when compared with a control group without MIH services, which could then serve as a comparison point to the results of this study. As it stands, given the relative novelty of MIH, there are primarily only broad reviews of MIH’s effectiveness and/or impact on patient populations that have been published. Of these, only a few directly mentioned MIH in relation to COPD, and none have comparable designs that look at overall COPD hospitalization reductions post-MIH implementation. There is also little to no literature looking at the utilization of MIH in a more intensive COPD outpatient pathway.

Finally, MIH has proven to be a useful tool for our institution in many areas outside of COPD management. Specifically, MIH has been utilized as a mobile influenza and COVID-19 vaccination unit and in-home testing service and now operates both a hospital-at-home and skilled nursing facility-at-home program. Analysis of the overall needs of the system and where this valuable MIH resource would have the biggest impact will be key in future growth opportunities.

Conclusion

MIH has been an invaluable tool for our hospital, especially in light of the recent shift toward more in-home and virtual care. MIH cared for 214 patients with COPD with more than 650 visits between March 2020 and August 2021. Eighty-seven emergent COPD visits were conducted, and COPD admissions were reduced dramatically from 2019 to 2020. MIH services have improved hospital flow, allowed for earlier discharge from the ED and inpatient care, and helped improve all-cause COPD readmission rates. The importance of postdischarge care and follow-up visits for patients with COPD, especially those at higher risk for readmission, cannot be understated. We hope our experience working to improve COPD patient outcomes serves as valuable a reference point for future MIH programs.

Corresponding author: Kelly Lannutti, DO, Mobile Integrated Health and Emergency Medicine Department, South Shore Health, 55 Fogg Rd, South Weymouth, MA 02190; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Accessed September 10, 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/index.html

2. Wier LM, Elixhauser A, Pfuntner A, AuDH. Overview of Hospitalizations among Patients with COPD, 2008. Statistical Brief #106. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

3. Shah T, Press,VG, Huisingh-Scheetz M, White SR. COPD Readmissions: Addressing COPD in the Era of Value-Based Health Care. Chest. 2016;150(4):916-926. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.002

4. Harries TH, Thornton H, Crichton S, et al. Hospital readmissions for COPD: a retrospective longitudinal study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):31. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0028-8

5. Ford ES. Hospital discharges, readmissions, and ED visits for COPD or bronchiectasis among US adults: findings from the nationwide inpatient sample 2001-2012 and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample 2006-2011. Chest. 2015;147(4):989-998. doi:10.1378/chest.14-2146

6. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0803563

7. Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):175-182. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081491

8. Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, et al. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home.” Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):512-519. doi:10.5694/mja12.10480

9. Portillo EC, Wilcox A, Seckel E, et al. Reducing COPD readmission rates: using a COPD care service during care transitions. Fed Pract. 2018;35(11):30-36.

10. Nourazari S, Davis SR, Granovsky R, et al. Decreased hospital admissions through emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;42:203-210. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.029

11. Taylor ML, Thomas EE, Snoswell CL, et al. Does remote patient monitoring reduce acute care use? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e040232. doi:10.1136/bmj/open-2020-040232

From the Mobile Integrated Health and Emergency Medicine Department, South Shore Health, Weymouth, MA.

Objective: To develop a process through which Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) can treat patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at high risk for readmission in an outpatient setting. In turn, South Shore Hospital (SSH) looks to leverage MIH to improve hospital flow, decrease costs, and improve patient quality of life.

Methods: With the recent approval of hospital-based MIH programs in Massachusetts, SSH used MIH to target specific patient demographics in an at-home setting. Here, we describe the planning and implementation of this program for patients with COPD. Key components to success include collaboration among providers, early follow-up visits, patient education, and in-depth medical reconciliations. Analysis includes a retrospective examination of a structured COPD outpatient pathway.

Results: A total of 214 patients with COPD were treated with MIH from March 2, 2020, to August 1, 2021. Eighty-seven emergent visits were conducted, and more than 650 total visits were made. A more intensive outpatient pathway was implemented for patients deemed to be at the highest risk for readmission by pulmonary specialists.

Conclusion: This process can serve as a template for future institutions to treat patients with COPD using MIH or similar hospital-at-home services.

Keywords: Mobile Integrated Health; MIH; COPD; population health.

It is estimated that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects more than 16 million Americans1 and accounts for more than 700 000 hospitalizations each year in the US.2 Thirty-day COPD readmission rates hover around 22.6%,3 and readmission within 90 days of initial discharge can jump to between 31% and 35%.4 This is the highest of any patient demographic, and more than half of these readmissions are due to COPD. To counter this, government and state entities have made nationwide efforts to encourage health systems to focus on preventing readmissions. In October 2014, the US added COPD to the active list of diseases in Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), later adding COPD to various risk-based bundle programs that hospitals may choose to opt into. These programs are designed to reduce all-cause readmissions after an acute exacerbation of COPD, as the HRRP penalizes hospitals for all-cause 30-day readmissions.3 However, what is most troubling is that, despite these efforts, readmission rates have not dropped in the past decade.5 COPD remains the third leading cause of death in America and still poses a significant burden both clinically and economically to hospitals across the country.3

A solution that is gaining traction is to encourage outpatient care initiatives and discharge pathways. Early follow-up is proven to decrease chances of readmission, and studies have shown that more than half of readmitted patients did not follow up with a primary care physician (PCP) within 30 days of their initial discharge.6 Additionally, large meta-analyses show hospital-at-home–type programs can lead to reductions in mortality, decrease costs, decrease readmissions, and increase patient satisfaction.7-9 Therefore, for more challenging patient populations with regard to readmissions and mortality, Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) may be the solution that we are looking for.

This article presents a viable process to treat patients with COPD in an outpatient setting with MIH Services. It includes an examination of what makes MIH successful as well as a closer look at a structured COPD outpatient pathway.

Methods

South Shore Hospital (SSH) is an independent, not-for-profit hospital located in Weymouth, Massachusetts. It is host to 400 beds, 100 000 annual visits to the emergency department (ED), and its own emergency medical services program. In March 2020, SSH became the first Massachusetts hospital-based program to acquire an MIH license. MIH paramedics receive 300 hours of specialized training, including time in clinical clerkships shadowing pulmonary specialists, cardiology/congestive heart failure (CHF) providers, addiction medicine specialists, home care and care progression colleagues, and wound center providers. Specialist providers become more comfortable with paramedic capabilities as a result of these clerkships, improving interactions and relationships going forward. At the time of writing, SSH MIH is staffed by 12 paramedics, 4 of whom are full time; 2 medical directors; 2 internal coordinators; and 1 registered nurse (RN). A minimum of 2 paramedics are on call each day, each with twice-daily intravenous (IV) capabilities. The first shift slot is 16 hours, from 7:00 AM to 11:00

The goal of developing MIH is to improve upon the current standard of care. For hospitals without MIH capabilities, there are limited options to treat acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) patients postdischarge. It is common for the only outpatient referral to be a lone PCP visit, and many patients who need more extensive treatment options don’t have access to a timely PCP follow-up or resources for alternative care. This is part of why there has been little improvement in the 21st century with regard to reducing COPD hospitalizations. As it stands, approximately 10% to 55% of all AECOPD readmissions are preventable, and more than one-fifth of patients with COPD are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge.3 In response, MIH has been designed to provide robust care options postdischarge in the patient home, with the eventual goal of reducing preventable hospitalizations and readmissions for all patients with COPD.

Patient selection

Patients with COPD are admitted to the MIH program in 1 of 3 ways: (1) directly from the ED; (2) at discharge from inpatient care; or (3) from a SSH affiliate referral.

With option 1, the ED physician assesses patient need for MIH services and places a referral to MIH in the electronic medical record (EMR). The ED provider also specifies whether follow-up is “urgent” and sets an alternative level of priority if not. With option 2, the inpatient provider and case manager follow a similar process, first determining whether a patient is stable enough to go home with outpatient services and then if MIH would be beneficial to the patient. If the patient is discharged home, a follow-up visit by an MIH paramedic is scheduled within 48 hours. With option 3, the patient is referred to MIH by an affiliate of SSH. This can be through the patient’s PCP, their visiting nurse association (VNA) service provider, or through any SSH urgent care center. In all 3 referral processes, the patient has the option to consent into the program or refuse services. Once referred, MIH coordinators review patients on a case-by-case basis. Patients with a history of prior admissions are given preference, with the goal being to keep the frailer, older, and comorbid patients at home. Other considerations include recent admission(s), length of stay, and overall stability. Social factors considered by the team include whether the patient lives alone and has alternative home services and the patient’s total distance from the hospital. Patients with a history of violence, mental health concerns, or substance abuse go through a more extensive screening process to ensure paramedic safety.

Given their patient profile and high hospital usage rates, MIH is sometimes requested for patients with end-stage COPD. Many of these patients benefit from MIH goals-of-care conversations to ensure they understand all their options and choose an approach that fits their preferences. In these cases, MIH has been instrumental in assisting patients and families with completing Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment and health care proxy forms and transitioning patients to palliative care, hospice, advanced-illness care management programs, or other long-term care options to prevent the need for rehospitalization. The MIH team focuses heavily on providing quality end-of-life care for patients and aligning care models with patient and family goals, often finding that having these sensitive conversations in the comfort of home enables transparency and comfort not otherwise experienced by hospitalized patients.

Initial patient follow-up

For patients with COPD enrolled in the MIH program, their first patient visit is scheduled within 48 hours of discharge from the ED or inpatient hospital. In many cases, this visit can be conducted within 24 hours of returning home. Once at the patient’s home, the paramedic begins with general introductions, vital signs, and a basic physical examination. The remainder of the visit focuses on patient education and symptom recognition. The paramedic reviews the COPD action plan (Figure 1), including how to recognize the onset of a “COPD flare-up” and the appropriate response. Patients are provided with a paper copy of the action plan for future reference.

The next point of educational emphasis is the patient’s individual medication regimen. This involves differentiating between control (daily) and rescue medications, how to use oxygen tanks, and how to safely wean off of oxygen. Specific attention is given to how to use a metered-dose inhaler, as studies have found that more than half of all patients use their inhaler devices incorrectly.10

Paramedics also complete a home safety evaluation of the patient’s residence, which involves checking for tripping hazards, lighting, handrails, slippery surfaces, and general access to patient medication. If an issue cannot be resolved by the paramedic on site and is considered a safety hazard, it is reported back to the hospital team for assistance.

Finally, patients are educated on the capabilities of MIH as a program and what to expect when they reach out over the phone. Patients are given a phone number to call for both “urgent” and “nonemergent” situations. In both cases, they will be greeted by one of the MIH coordinators or nurses who assist with triaging patient symptoms, scheduling a visit, or providing other guidance. It is a point of emphasis that the patient can use MIH for more than just COPD and should call in the event of any illness or discomfort (eg, dehydration, fever) in an effort to prevent unnecessary ED visits.

Medication reconciliation

Patients with COPD often have complex medication regimens. To help alleviate any confusion, medication reconciliations are done in conjunction with every COPD patient’s initial visit. During this process, the paramedic first takes an inventory of all medications in the patient home. Common reasons for nonadherence include confusing packaging, inability to reach the pharmacy, or medication not being covered by insurance. The paramedic reconciles the updated medication regimen against the medications that are physically in the home. Once the initial review is complete, the paramedic teleconferences with a registered hospitalist pharmacist (RHP) for a more in-depth review. Over video chat, the RHP reviews each medication individually to make sure the patient understands how many times per day they take each medication, whether it is a control or rescue medication, and what times of the day to take them. The RHP will then clarify any other medication questions the patient has, assure all recent medications have been picked up from the pharmacy, and determine any barriers, such as cost or transportation.

Follow-ups and PCP involvement

At each in-person visit, paramedics coordinate with an advanced practice clinician (APC) through telehealth communication. On these video calls with a provider, the paramedic relays relevant information pertaining to patient history, vital signs, and current status. Any concerning findings, symptoms of COPD flare-ups, or recent changes in status will be discussed. The APC then speaks directly to the patient to gather additional details about their condition and any recent hospitalizations, with their primary role being to make clinical decisions on further treatment. For the COPD population, this often includes orders for the MIH paramedic to administer IV medication (ie, IV methylprednisolone or other corticosteroids), antibiotics, home nebulizers, and at-home oxygen.

Second and third follow-up paramedic visits are often less intensive. Although these visits often still involve telehealth calls to the APC, the overall focus shifts toward medication adherence, ED avoidance, and readmission avoidance. On these visits, the paramedic also checks vitals, conducts a physical examination, and completes follow-up testing or orders per the APC.

PCP involvement is critical to streamlining and transitioning patient care. Patients who are admitted to MIH without insurance or a PCP are assisted in the process of finding one. PCPs automatically receive a patient enrollment letter when their patient is seen by an MIH paramedic. Following each individual visit, paramedic and APC notes are sent to the PCP through the EMR or via fax, at which time the PCP may be consulted on patient history and/or future care decisions. After the transition back to care by their PCP, patients are still encouraged to utilize MIH if acute changes arise. If a patient is readmitted back to the hospital, MIH is automatically notified, and coordinators will assess whether there is continued need for outpatient services or areas for potential improvement.

Emergent MIH visits

While MIH visits with patients with COPD are often scheduled, MIH can also be leveraged in urgent situations to prevent the need for a patient to come to the ED or hospital. Patients with COPD are told to call MIH if they have worsening symptoms or have exhausted all methods of self-treatment without an improvement in status. In this case, a paramedic is notified and sent to the patient’s home at the earliest time possible. The paramedic then completes an assessment of the patient’s status and relays information to the MIH APC or medical director. From there, treatment decisions, such as starting the patient on an IV, using nebulizers, or doing an electrocardiogram for diagnostic purposes, are guided by the provider team with the ultimate goal of caring for the patient in the home. For our population, providing urgent care in the home has proven to be an effective way to avoid unnecessary readmissions while still ensuring high-quality patient care.

Outpatient pathway

In May 2021, select patients with COPD were given the option to participate in a more intensive MIH outpatient pathway. Pilot patients were chosen by 2 pulmonary specialists, with a focus on enrolling patients with COPD at the highest risk for readmission. Patients who opted in were followed by MIH for a total of 30 days.

The first visit was made as usual within 48 hours of discharge. Patients received education, medication reconciliation, vitals examination, home safety evaluation, and a facilitated telehealth evaluation with the APC. What differentiates the pathway from standard MIH services is that after the first visit, the follow-ups are prescheduled and more numerous. This is outlined best in Figure 2, which serves as a guideline for coordinators and paramedics in the cadence and focus of visits for each patient on the pathway. The initial 2 weeks are designed to check in on the patient in person and ensure active recovery. The latter 2 weeks are designed to ensure that the patient follows up with their care team and understands their medications and action plan going forward. Pathway patients were also monitored using a remote patient monitoring (RPM) kit. On the initial visit, paramedics set up the RPM equipment and provided a demonstration on how to use each device. Patients were issued a Bluetooth-enabled scale, blood pressure cuff, video-enabled tablet, and wearable device. The wearable device continuously recorded respiration rate, heart rate, and oxygen saturation and had fall-detection enabled. Over the course of a month, an experienced MIH nurse monitored the vitals transmitted by the wearable device and checked patient weight and blood pressure 1 to 2 times per day, utilizing these data to proactively outreach to patients if abnormalities occurred. Prior to the start of the program, the MIH nurse contacted each patient to introduce herself and notify them that they would receive a call if any vitals were unusual.

Results

MIH treated 214 patients with COPD from March 2, 2020, to August 2, 2021. In total, paramedics made more than 650 visits. Eighty-seven of these were documented as urgent visits with AECOPD, shortness of breath, cough, or wheezing as the primary concern.

In the calendar year of 2019, our institution admitted 804 patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD. In 2020, the first year with MIH, total COPD admissions decreased to 473; however, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be discounted. At of the time of writing—219 days into 2021—253 patients with COPD have been admitted thus far (Table 1).

Pathway results

Sixteen patients were referred to the MIH COPD Discharge Pathway Pilot during May 2021. Ten patients went on to complete the entire 30-day pathway. Six did not finish the program. Three of these 6 patients were referred by a pulmonary specialist for enrollment but not ultimately referred to the pilot program by case management and therefore not enrolled. The other 3 of the 6 patients who did not complete the pilot program were enrolled but discontinued owing to noncompliance.

Of the 10 patients who completed the pathway, 3 patients were male, and 7 were female. Ages ranged from 55 to 84 years. On average, the RHP found 3.6 medication reconciliation errors per patient. One patient was readmitted within 30 days (only 3 days after the initial discharge), and 5 were readmitted within 90 days.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients with COPD who were not provided with MIH services and were admitted to our hospital between September 1, 2020, and March 1, 2021, for comparison. Age, sex, and other related conditions are shown in Table 2. Medication reconciliation error data were not tracked for this demographic, as they did not have an in-home medication reconciliation completed.

Discussion

MIH has treated 214 patients with COPD from March 2, 2020, to August 2, 2021, a 17-month period. In that same timeframe, the hospital experienced a 42% decrease in COPD admissions. Although this effect is not the sole product of MIH (specifically, COVID-19 caused a drop in all-cause hospital admissions), we believe MIH did play a small role in this reduction. Eighty-seven emergent visits were conducted for patients with a primary complaint of AECOPD, shortness of breath, cough, or wheezing. On these visits, MIH provided urgent treatment to prevent the patient returning to the ED and potentially leading to readmission.

The program’s impact extends beyond the numbers. With more than 200 patients with COPD treated at home, we improved hospital flow, shortened patients’ overall length of stay, and increased capacity in the ED and inpatient units. In addition, MIH has been able to fill in care gaps present in the current health care system by providing acute care in the home to patients who otherwise have access-to-care and transportation issues.

What made the program successful

With the COPD population prone to having complex medication regimens, medication reconciliations were critical to improving patient outcomes. During the documented medication reconciliations for pathway patients, 8 of 10 patients had medication errors identified. Some of the more common errors included incorrect inhaler usage, patient medication not arriving to the pharmacy for a week or more after discharge, prescribed medication dosages that were too high or too low, and a lack of transportation to pick up the patient’s prescription. Even more problematic is that 7 of these 8 patients required multiple interventions to correct their regimen. What was cited as most beneficial by both the paramedic and the RHP was taking time to walk through each medication individually and ensuring that the patient could recite back how often and when they should be using it. What also proved to be helpful was spending extra time on the inhalers and nebulizers. Multiple patients did not know how to use them properly and/or cited a history of struggling with them.

The MIH COPD pathway patients showed encouraging preliminary results. In the initial 30-day window, only 1 of 10 (10%) patients was readmitted, which is lower than the 37.7% rate for comparable patients who did not have MIH services. This could imply that patients with COPD respond positively to active and consistent management with predetermined points of contact. Ninety-day readmission rates jumped to 5 of 10, with 4 of these patients being readmitted multiple times. Approximately half of these readmissions were COPD related. It is important to remember that the patients being targeted by the pathway are deemed to be at very high risk of readmission. As such, one could expect that even with a successful reduction in rates, pathway patient readmission rates may be slightly elevated compared with national COPD averages.

Given the more personalized and at-home care, patients also expressed higher levels of care satisfaction. Most patients want to avoid the hospital at all costs, and MIH provides a safe and effective alternative. Patients with COPD have also relayed that the education they receive on their medication, disease, and how to use MIH has been useful. This is reflected in the volume of urgent calls that MIH receives. A patient calling MIH in place of 911 shows not only that the patient has a level of trust in the MIH team, but also that they have learned how to recognize symptoms earlier to prevent major flare-ups.

This study had several limitations. On the pilot pathway, 3 patients were removed from MIH services because of repeated noncompliance. These instances primarily involved aggression toward the paramedics, both verbal and physical, as well as refusal to allow the MIH paramedics into the home. Going forward, it will be valuable to have a screening process for pathway patients to determine likelihood of compliance. This could include speaking to the patient’s PCP or other in-hospital providers before accepting them into the program.

Remote patient monitoring also presented its challenges. Despite extensive equipment demonstrations, some patients struggled to grasp the technology. Some of the biggest problems cited were confusion operating the tablet, inability to charge the devices, and issues with connectivity. In the future, it may be useful to simplify the devices even more. Further work should also be done to evaluate the efficacy of remote patient technology in this specific setting, as studies have shown varied results with regard to RPM success. In 1 meta-analysis of 91 different published studies that took place between 2015 and 2020, approximately half of the RPM studies resulted in no change in hospital readmissions, length of stay, or ED presentations, while the other half saw improvement in these categories.11 We suspect that the greatest benefits of our work came from the patient education, trust built over time, in-home urgent evaluations, and 1-on-1 time with the paramedic.

With many people forgoing care during the pandemic, COVID-19 has also caused a downward trend in overall and non-COVID-19 admissions. In a review of more than 500 000 ED visits in Massachusetts between March 11, 2020, and September 8, 2021, there was a 32% decrease in admissions when compared with those same weeks in 2019.10 There was an even greater drop-off when it came to COPD and other respiratory-related admissions. In evaluating the impact SSH MIH has made, it is important to recognize that the pandemic contributed to reducing total COPD admissions. Adding merit to the success of MIH in contributing to the reduction in admissions is the continued downward trend in total COPD admissions year-to-date in 2021. Despite total hospital usage rates increasing at our institution over the course of this year, the overall COPD usage rates have remained lower than before.

Another limitation is that in the selection of patients, both for general MIH care and for the COPD pathway, there was room for bias. The pilot pathway was offered specifically to patients at the highest risk for readmission; however, patients were referred at the discretion of our pulmonologist care team and not selected by any standardized rubric. Additionally, MIH only operates on a 16-hour schedule. This means that patients admitted to the ED or inpatient at night may sometimes be missed and not referred to MIH for care.

The biggest caveat to the pathway results is, of course, the small sample size. With only 10 patients completing the pilot, it is impossible to come to any concrete conclusions. Such an intensive pathway requires dedicating large amounts of time and resources, which is why the pilot was small. However, considering the preliminary results, the outline given could provide a starting point for future work to evaluate a similar COPD pathway on a larger scale.

Future considerations

Risk stratification of patients is critical to achieving even further reductions in readmissions and mortality. Hospitals can get the most value from MIH by focusing on patients with COPD at the highest risk for return, and it would be valuable to explicitly define who fits into this criterion. Utilizing a tool similar to the LACE index for readmission but tailoring it to patients with COPD when admitting patients into the program would be a logical next step.

Reducing the points of patient contact could also prove valuable. Over the course of a patient’s time with MIH, they interact with an RHP, APC, paramedic, RN, and discharging hospitalist. Additionally, we found many patients had VNA services, home health aides, care managers, and/or social workers involved in their care. Some patients found this to be stressful and overwhelming, especially regarding the number of outreach calls soon after discharge.

It would also be useful to look at the impact of MIH on total COPD admissions independent of the artificial variation created by COVID-19. This may require waiting until there are higher levels of vaccination and/or finding ways to control for the potential variation. In doing so, one could look at the direct effect MIH has on COPD readmissions when compared with a control group without MIH services, which could then serve as a comparison point to the results of this study. As it stands, given the relative novelty of MIH, there are primarily only broad reviews of MIH’s effectiveness and/or impact on patient populations that have been published. Of these, only a few directly mentioned MIH in relation to COPD, and none have comparable designs that look at overall COPD hospitalization reductions post-MIH implementation. There is also little to no literature looking at the utilization of MIH in a more intensive COPD outpatient pathway.

Finally, MIH has proven to be a useful tool for our institution in many areas outside of COPD management. Specifically, MIH has been utilized as a mobile influenza and COVID-19 vaccination unit and in-home testing service and now operates both a hospital-at-home and skilled nursing facility-at-home program. Analysis of the overall needs of the system and where this valuable MIH resource would have the biggest impact will be key in future growth opportunities.

Conclusion

MIH has been an invaluable tool for our hospital, especially in light of the recent shift toward more in-home and virtual care. MIH cared for 214 patients with COPD with more than 650 visits between March 2020 and August 2021. Eighty-seven emergent COPD visits were conducted, and COPD admissions were reduced dramatically from 2019 to 2020. MIH services have improved hospital flow, allowed for earlier discharge from the ED and inpatient care, and helped improve all-cause COPD readmission rates. The importance of postdischarge care and follow-up visits for patients with COPD, especially those at higher risk for readmission, cannot be understated. We hope our experience working to improve COPD patient outcomes serves as valuable a reference point for future MIH programs.

Corresponding author: Kelly Lannutti, DO, Mobile Integrated Health and Emergency Medicine Department, South Shore Health, 55 Fogg Rd, South Weymouth, MA 02190; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Mobile Integrated Health and Emergency Medicine Department, South Shore Health, Weymouth, MA.

Objective: To develop a process through which Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) can treat patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at high risk for readmission in an outpatient setting. In turn, South Shore Hospital (SSH) looks to leverage MIH to improve hospital flow, decrease costs, and improve patient quality of life.

Methods: With the recent approval of hospital-based MIH programs in Massachusetts, SSH used MIH to target specific patient demographics in an at-home setting. Here, we describe the planning and implementation of this program for patients with COPD. Key components to success include collaboration among providers, early follow-up visits, patient education, and in-depth medical reconciliations. Analysis includes a retrospective examination of a structured COPD outpatient pathway.

Results: A total of 214 patients with COPD were treated with MIH from March 2, 2020, to August 1, 2021. Eighty-seven emergent visits were conducted, and more than 650 total visits were made. A more intensive outpatient pathway was implemented for patients deemed to be at the highest risk for readmission by pulmonary specialists.

Conclusion: This process can serve as a template for future institutions to treat patients with COPD using MIH or similar hospital-at-home services.

Keywords: Mobile Integrated Health; MIH; COPD; population health.

It is estimated that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects more than 16 million Americans1 and accounts for more than 700 000 hospitalizations each year in the US.2 Thirty-day COPD readmission rates hover around 22.6%,3 and readmission within 90 days of initial discharge can jump to between 31% and 35%.4 This is the highest of any patient demographic, and more than half of these readmissions are due to COPD. To counter this, government and state entities have made nationwide efforts to encourage health systems to focus on preventing readmissions. In October 2014, the US added COPD to the active list of diseases in Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), later adding COPD to various risk-based bundle programs that hospitals may choose to opt into. These programs are designed to reduce all-cause readmissions after an acute exacerbation of COPD, as the HRRP penalizes hospitals for all-cause 30-day readmissions.3 However, what is most troubling is that, despite these efforts, readmission rates have not dropped in the past decade.5 COPD remains the third leading cause of death in America and still poses a significant burden both clinically and economically to hospitals across the country.3

A solution that is gaining traction is to encourage outpatient care initiatives and discharge pathways. Early follow-up is proven to decrease chances of readmission, and studies have shown that more than half of readmitted patients did not follow up with a primary care physician (PCP) within 30 days of their initial discharge.6 Additionally, large meta-analyses show hospital-at-home–type programs can lead to reductions in mortality, decrease costs, decrease readmissions, and increase patient satisfaction.7-9 Therefore, for more challenging patient populations with regard to readmissions and mortality, Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) may be the solution that we are looking for.

This article presents a viable process to treat patients with COPD in an outpatient setting with MIH Services. It includes an examination of what makes MIH successful as well as a closer look at a structured COPD outpatient pathway.

Methods

South Shore Hospital (SSH) is an independent, not-for-profit hospital located in Weymouth, Massachusetts. It is host to 400 beds, 100 000 annual visits to the emergency department (ED), and its own emergency medical services program. In March 2020, SSH became the first Massachusetts hospital-based program to acquire an MIH license. MIH paramedics receive 300 hours of specialized training, including time in clinical clerkships shadowing pulmonary specialists, cardiology/congestive heart failure (CHF) providers, addiction medicine specialists, home care and care progression colleagues, and wound center providers. Specialist providers become more comfortable with paramedic capabilities as a result of these clerkships, improving interactions and relationships going forward. At the time of writing, SSH MIH is staffed by 12 paramedics, 4 of whom are full time; 2 medical directors; 2 internal coordinators; and 1 registered nurse (RN). A minimum of 2 paramedics are on call each day, each with twice-daily intravenous (IV) capabilities. The first shift slot is 16 hours, from 7:00 AM to 11:00

The goal of developing MIH is to improve upon the current standard of care. For hospitals without MIH capabilities, there are limited options to treat acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) patients postdischarge. It is common for the only outpatient referral to be a lone PCP visit, and many patients who need more extensive treatment options don’t have access to a timely PCP follow-up or resources for alternative care. This is part of why there has been little improvement in the 21st century with regard to reducing COPD hospitalizations. As it stands, approximately 10% to 55% of all AECOPD readmissions are preventable, and more than one-fifth of patients with COPD are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge.3 In response, MIH has been designed to provide robust care options postdischarge in the patient home, with the eventual goal of reducing preventable hospitalizations and readmissions for all patients with COPD.

Patient selection

Patients with COPD are admitted to the MIH program in 1 of 3 ways: (1) directly from the ED; (2) at discharge from inpatient care; or (3) from a SSH affiliate referral.