User login

An Unusual Presentation of Calciphylaxis

To the Editor:

Calciphylaxis (also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy and calcifying panniculitis) is a rare vasculopathy affecting the small vessels.1 It is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification. It is most commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hyperparathyroidism.1-3 Histopathologic features that are consistent with the diagnosis of calciphylaxis include calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat as well as smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis.4,5 Although it commonly presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish lesions that evolve into necrotic eschars, calciphylaxis rarely can present with hemorrhagic or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.1,5,6 We report this uncommon presentation to highlight the variety in clinical appearance of calciphylaxis and the importance of early diagnosis.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of chest and abdominal pain that began 1 day prior to presentation. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and ESRD secondary to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and was currently on peritoneal dialysis. The patient was admitted for peritonitis and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. At the time of admission, the patient also was noted to have several painful bullae on the legs. Her medical history also was remarkable for cerebral infarction, fibromyalgia, cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction, sciatica, hyperlipidemia, deep vein thrombosis, and seizures. She had no history of herpes simplex virus. Surgical history was remarkable for tubal ligation, nephrectomy and kidney transplant, parathyroidectomy, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s medications included sevelamer carbonate, prednisone, epogen, calcium carbonate, esomeprazole, ondansetron, topical gentamicin, and atorvastatin.

Skin examination was performed by the inpatient dermatology service and revealed several tense, 1- to 5-cm, nonhemorrhagic bullae on the thighs and lower legs, some that had ruptured. The lesions were notably tender to palpation. No surrounding erythema, ecchymosis, or warmth was appreciated. The Nikolsky sign was negative. The patient also was noted to have at least grade 2 to 3+ pitting edema of the bilateral legs. The oral and conjunctival mucosae were unremarkable.

Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibody levels were negative. A punch biopsy of the left lateral thigh revealed intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis with dermal edema suggestive of edema bullae and direct immunofluorescence was negative for immune complex and complement deposition.

Conservative therapy with wound care was recommended. The patient continued to report persistent severe skin pain and developed a subcutaneous nodule on the right inner thigh 1 week later, prompting a second biopsy. Results of the excisional biopsy were nondiagnostic but were suggestive of calciphylaxis, revealing subepidermal bullae with epidermal necrosis, a scant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasated erythrocytes. No evidence of calcification was seen within the vessels. The patient was then started on sodium thiosulfate with hemodialysis for treatment of presumed calciphylaxis.

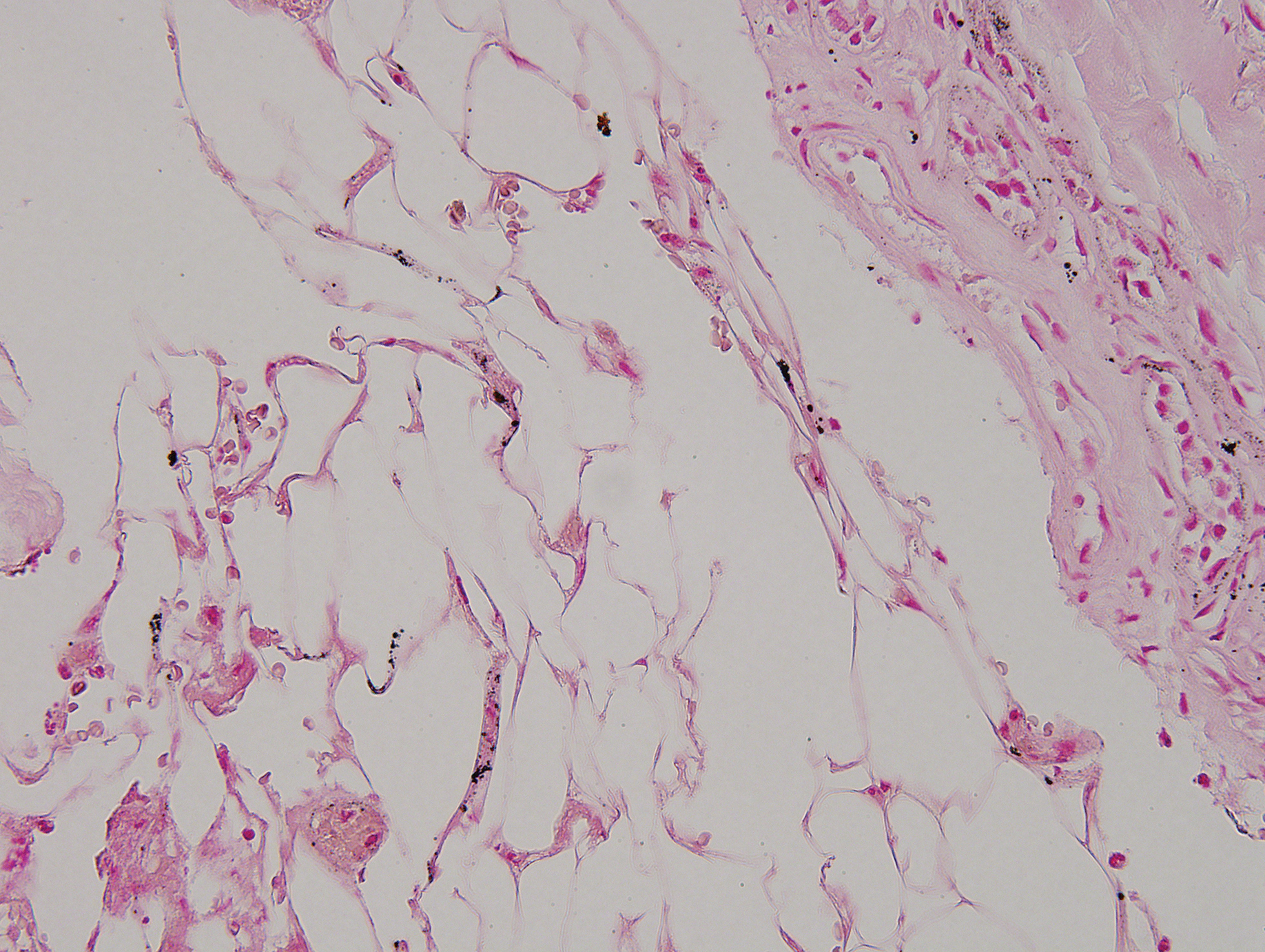

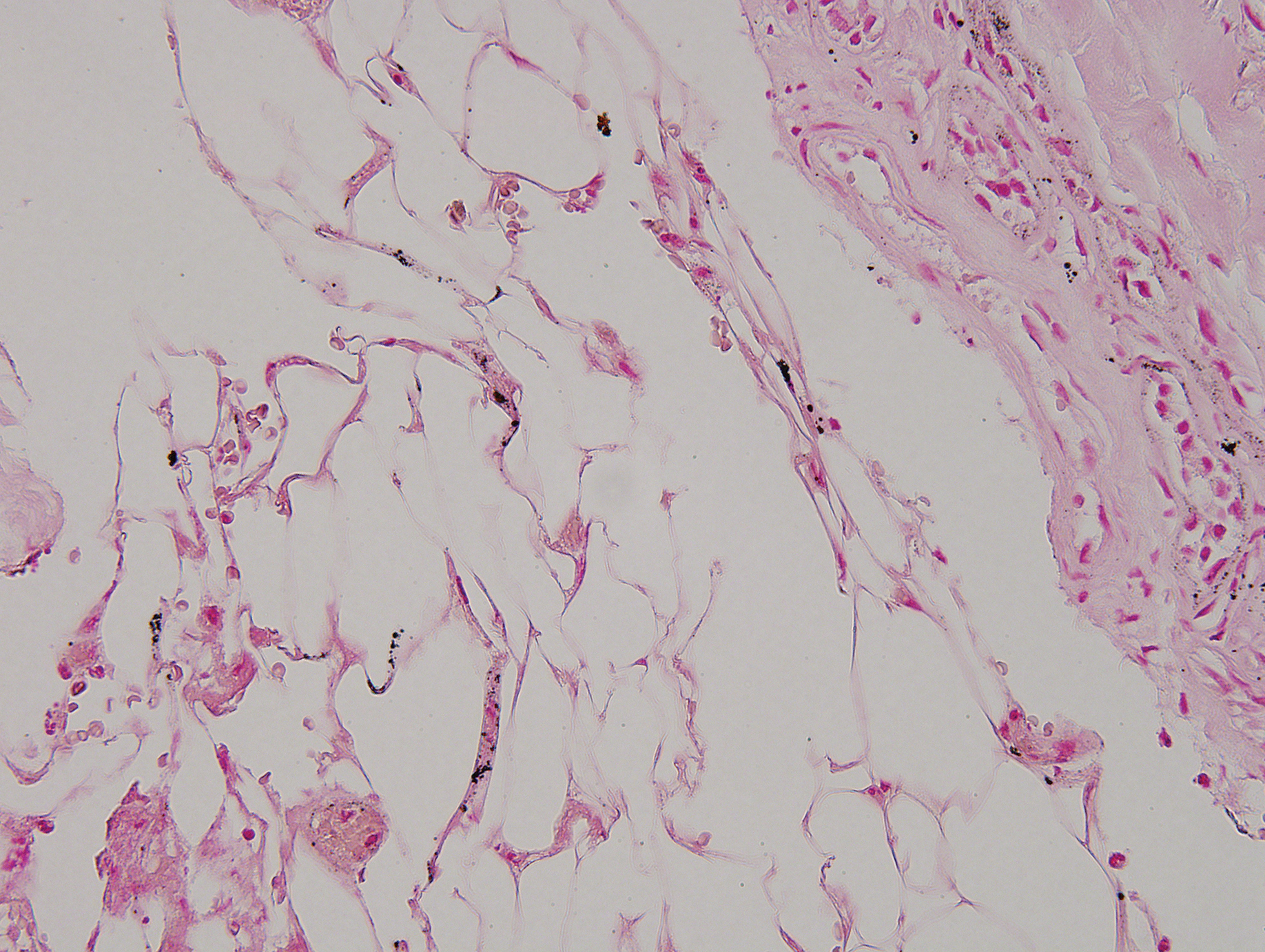

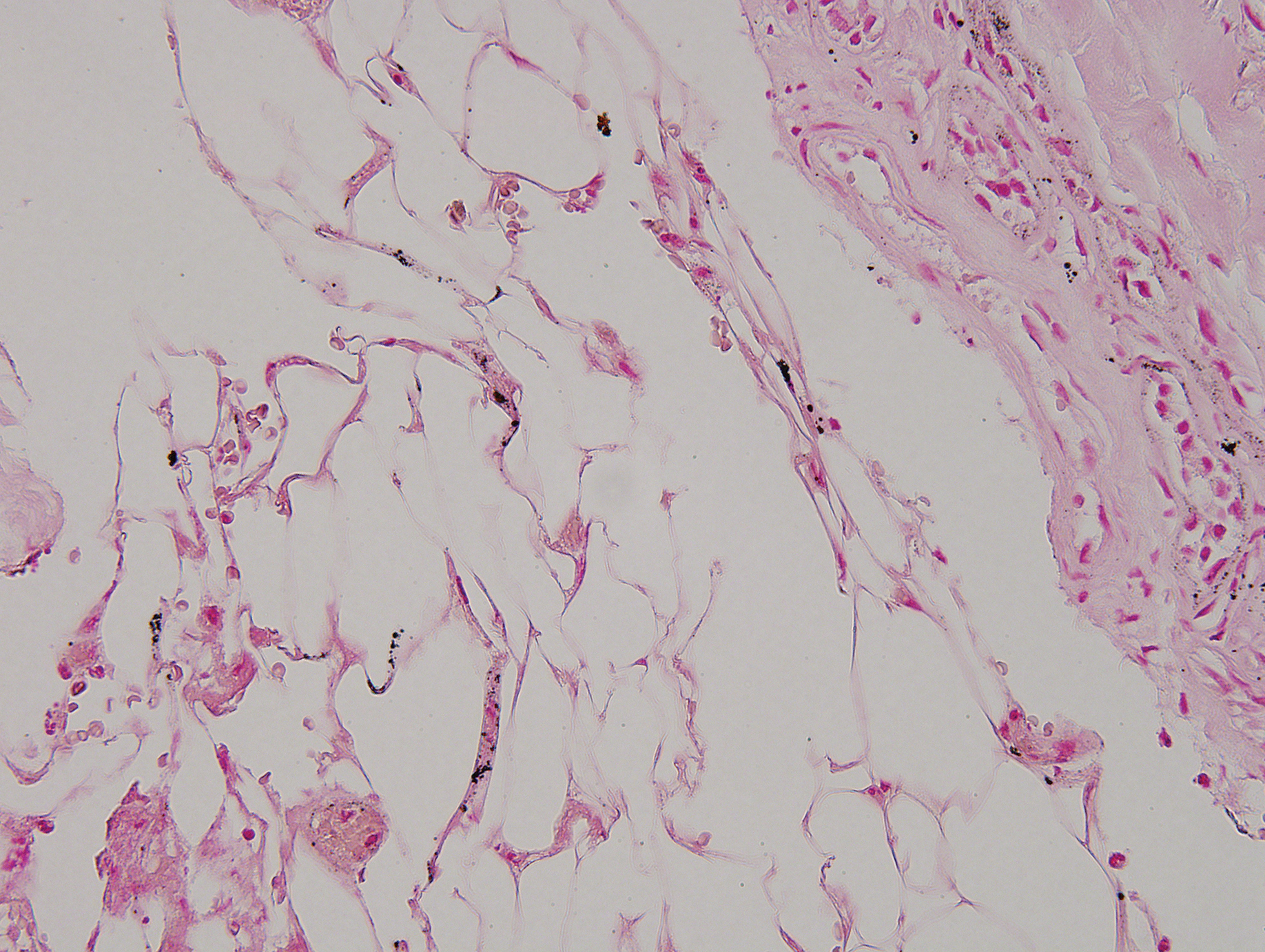

Despite meticulous wound care and treatment with sodium thiosulfate, the patient developed ulcerations with necrotic eschars on the bilateral buttocks, hips, and thighs 1 month later (Figure 1). She subsequently worsened over the next few weeks. She developed sepsis and was transferred to the intensive care unit. A third biopsy was performed, finally confirming the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Histopathology revealed small blood vessels with basophilic granular deposits in the walls consistent with calcium in the subcutaneous tissue (highlighted with the von Kossa stain), as well as thrombi in the lumens of some vessels; early fat necrosis; focal epidermal necrosis with underlying congested blood vessels with deposits in their walls; a perivascular infiltrate predominately of lymphocytes and neutrophils with scattered nuclear dust; and thick, hyalinized, closely crowded collagen bundles in the reticular dermis and in a widened subcutaneous septum (Figures 2 and 3).

Supportive care and pain control were continued, but the overall prognosis was determined to be very poor, and the patient eventually was discharged to hospice and died.

Although calciphylaxis is commonly seen in patients with ESRD and hyperparathyroidism, patients without renal disease also may develop the condition.2,3 Prior epidemiologic studies have shown a prevalence of 1% in patients with chronic kidney disease and up to 4% in those receiving dialysis.2-5 The average age at presentation is 48 years.6,7 Although calciphylaxis has been noted to affect males and females equally, some studies have suggested a female predominance.5-8

The etiology of calciphylaxis is unknown, but ESRD requiring dialysis, primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, obesity, diabetes mellitus, skin trauma, and/or a hypercoagulable state may put patients at increased risk for developing this disease.2,3 Other risk factors include systemic corticosteroids, liver disease, increased serum aluminum, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although high calcium-phosphate product has been noted as a risk factor in prior studies, one retrospective study found that it does not reliably confirm or exclude a diagnosis of calciphylaxis.8

The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not well understood; however, some researchers suggest that an imbalance in calcium-phosphate homeostasis may lead to calciphylaxis; that is, elevated calcium and phosphate levels exceed their solubility and deposit in the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries, which consequently leads to ischemic necrosis and gangrene of the surrounding tissue.9

Clinically, calciphylaxis has an indolent onset and usually presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish, mottled lesions that evolve into necrotic gray-black eschars and gangrene in adjacent tissues.1,5,6 The ischemic process may even extend to the muscle layer.5 Other common presentations include mild erythematous patches; livedo reticularis; painful nodules; necrotic ulcerating lesions; and more rarely flaccid, hemorrhagic, or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.6,9,10 Lesions usually begin at sites of trauma and seem to be distributed symmetrically.5,6 The most commonly affected locations are the legs, specifically the medial thighs, as well as the abdomen and buttocks, but lesions also can be found at more distal sites such as the breasts, tongue, vulva, penis, fingers, and toes.5,6,10 The head and neck region rarely is affected. Although uncommon, calciphylaxis may affect other organs, including the lungs, stomach, kidneys, and adrenal glands.5 The accompanying systemic symptoms and findings may include muscle weakness, tenderness, or myositis with rhabdomyolysis; calcific cerebral embolism; dementia and infarction of the central nervous system; acute respiratory failure; heart disease; atrioventricular block; and calcification of the cardiac conduction system.6 Unlike other forms of peripheral vascular disease, distal pulses are present in calciphylaxis, as blood flow usually is preserved distal and deep to the areas of necrosis.5,6

A careful history and thorough physical examination are important first steps in the diagnosis of this condition.2,10 Although there are no definitive laboratory tests, elevated serum calcium, phosphorous, and calcium-phosphate product levels, as well as parathyroid hormone level, may be suggestive of calciphylaxis.2,5 Leukocytosis may occur if an infection is present.5

The most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis is a deep incisional biopsy from an erythematous, slightly purpuric area adjacent to the necrotic lesion.2,10,11 The histopathologic features used to make the diagnosis include calcification of medium-sized vessels, particularly the intimal or medial layers, in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat in addition to lobular capillaries of the subcutaneous fat.5,10 These vessels, including the smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis, also may be thrombosed due to calcification, leading to vascular occlusion and subsequently ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis.10 Other findings may include pseudoxanthoma elasticum changes, panniculitis, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.4,10

The differential diagnosis for calciphylaxis includes peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, juvenile dermatomyositis, proteins C and S deficiencies, cryofibrinogenemia, calcinosis cutis, and tumoral calcinosis.2 Polyarteritis nodosa, Sjögren syndrome, atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, systemic lupus erythematosus, necrotizing fasciitis, septic embolism, and necrosis secondary to warfarin and heparin may mimic calciphylaxis.5

Treatment of calciphylaxis is multidimensional but primarily is supportive.6,11 Controlling calcium and phosphate levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism through diet and phosphate binders (eg, sevelamer hydrochloride) has been shown to be effective.6 Pamidronate, a bisphosphonate, inhibits arterial calcification in animal models and has been reported to treat calciphylaxis, resulting in marked pain reduction and ulcer healing.4,6 Cinacalcet, which functions as a calcimimetic, has been implicated in the treatment of calciphylaxis. It has been used to treat primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and to normalize serum calcium levels; it also may be used as an alternative to parathyroidectomy.4,6 Intravenous administration of sodium thiosulfate, a potent antioxidant and chelator of calcium, has been helpful in reversing signs and symptoms of calciphylaxis.6,12 It also has been shown to effectively remove extra calcium during peritoneal dialysis.6 Parathyroidectomy has been useful in patients with markedly elevated parathyroid hormone levels, as it suppresses or eliminates the sensitizing agent causing hypercalcemia, elevated calcium-phosphate product, and hyperparathyroidism.1,2,6,13

Wound care and prevention of sepsis are essential in the treatment of calciphylaxis. Management options include surgical debridement, hydrocolloid and biologic dressings, skin grafts, systemic antibiotics, oral pentoxifylline combined with maggot therapy, nutritional support, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and revascularization and amputation when other interventions have failed. Pain control with analgesics and correction of thrombosis in the skin and blood vessels via anticoagulation therapy also are important complementary treatments.6

The clinical outcome of calciphylaxis is dependent on early diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and wound management,9 but overall, the prognosis usually is poor and has a high mortality rate. The most common causes of death are infection and sepsis.1,9 A study of 7 cases reported 100% mortality,14 but other studies have suggested a mortality rate of 60% to 80%.4,10 Female sex and obesity are poor prognostic indicators.2 A better prognosis has been appreciated in cases in which lesions occur at distal sites (eg, lower legs, hands) compared to more proximal sites (eg, abdomen), where 25% and 75% mortalities have been noted, respectively.10,14,15 In one study, the overall mortality rate was 45% in patients with calciphylaxis at 1 year.6 The rate was 41% in patients with plaques only and 67% in those who presented with ulceration. Patients who survive often experience a high degree of morbidity and prolonged hospitalization; these patients often are severely debilitated, especially in the case of limb amputation.6

Our report of calciphylaxis demonstrates the diversity in clinical presentation and emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis in reducing morbidity and mortality. In our case, the patient presented with skin pain and tense nonhemorrhagic bullae without underlying ecchymotic or erythematous lesions as the earliest sign of calciphylaxis. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion in the setting of dialysis-dependent ESRD patients with bullae, extreme pain, and continuous decline. We hope that this case will help increase awareness of the varying presentations of this condition.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;57:1021-1025.

- Somorin AO, Harbi AA, Subaity Y, et al. Calciphylaxis: case report and literature review. Afr J Med Sci. 2002;31:175-178.

- Barreiros HM, Goulão J, Cunha H, et al. Calciphylaxis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;2:69-70.

- Vedvyas C, Winterfield LS, Vleugels RA. Calciphylaxis: a systematic review of existing and emerging therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E253-E260.

- Beitz JM. Calciphylaxis: a case study with differential diagnosis. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2003;49:28-38.

- Daudén E, Oñate M. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:557-568.

- Oh DH, Eulau D, Tokugawa DA, et al. Five cases of calciphylaxis and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:979-987.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MDP, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-578.

- Hanvesakul R, Silva MA, Hejmadi R, et al. Calciphylaxis following kidney transplantation: a case report. J Med Cases. 2009;3:9297.

- Kouba DJ, Owens NM, Barrett TL, et al. An unusual case of calciphylaxis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:19-22.

- Arch-Ferrer JE, Beenken SW, Rue LW, et al. Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis. Surgery. 2003;134:941-945.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Mirza I, Chaubay D, Gunderia H, et al. An unusual presentation of calciphylaxis due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1351-1353.

- Alain J, Poulin YP, Cloutier RA, et al. Calciphylaxis: seven new cases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:213-218.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

To the Editor:

Calciphylaxis (also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy and calcifying panniculitis) is a rare vasculopathy affecting the small vessels.1 It is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification. It is most commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hyperparathyroidism.1-3 Histopathologic features that are consistent with the diagnosis of calciphylaxis include calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat as well as smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis.4,5 Although it commonly presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish lesions that evolve into necrotic eschars, calciphylaxis rarely can present with hemorrhagic or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.1,5,6 We report this uncommon presentation to highlight the variety in clinical appearance of calciphylaxis and the importance of early diagnosis.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of chest and abdominal pain that began 1 day prior to presentation. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and ESRD secondary to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and was currently on peritoneal dialysis. The patient was admitted for peritonitis and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. At the time of admission, the patient also was noted to have several painful bullae on the legs. Her medical history also was remarkable for cerebral infarction, fibromyalgia, cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction, sciatica, hyperlipidemia, deep vein thrombosis, and seizures. She had no history of herpes simplex virus. Surgical history was remarkable for tubal ligation, nephrectomy and kidney transplant, parathyroidectomy, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s medications included sevelamer carbonate, prednisone, epogen, calcium carbonate, esomeprazole, ondansetron, topical gentamicin, and atorvastatin.

Skin examination was performed by the inpatient dermatology service and revealed several tense, 1- to 5-cm, nonhemorrhagic bullae on the thighs and lower legs, some that had ruptured. The lesions were notably tender to palpation. No surrounding erythema, ecchymosis, or warmth was appreciated. The Nikolsky sign was negative. The patient also was noted to have at least grade 2 to 3+ pitting edema of the bilateral legs. The oral and conjunctival mucosae were unremarkable.

Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibody levels were negative. A punch biopsy of the left lateral thigh revealed intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis with dermal edema suggestive of edema bullae and direct immunofluorescence was negative for immune complex and complement deposition.

Conservative therapy with wound care was recommended. The patient continued to report persistent severe skin pain and developed a subcutaneous nodule on the right inner thigh 1 week later, prompting a second biopsy. Results of the excisional biopsy were nondiagnostic but were suggestive of calciphylaxis, revealing subepidermal bullae with epidermal necrosis, a scant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasated erythrocytes. No evidence of calcification was seen within the vessels. The patient was then started on sodium thiosulfate with hemodialysis for treatment of presumed calciphylaxis.

Despite meticulous wound care and treatment with sodium thiosulfate, the patient developed ulcerations with necrotic eschars on the bilateral buttocks, hips, and thighs 1 month later (Figure 1). She subsequently worsened over the next few weeks. She developed sepsis and was transferred to the intensive care unit. A third biopsy was performed, finally confirming the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Histopathology revealed small blood vessels with basophilic granular deposits in the walls consistent with calcium in the subcutaneous tissue (highlighted with the von Kossa stain), as well as thrombi in the lumens of some vessels; early fat necrosis; focal epidermal necrosis with underlying congested blood vessels with deposits in their walls; a perivascular infiltrate predominately of lymphocytes and neutrophils with scattered nuclear dust; and thick, hyalinized, closely crowded collagen bundles in the reticular dermis and in a widened subcutaneous septum (Figures 2 and 3).

Supportive care and pain control were continued, but the overall prognosis was determined to be very poor, and the patient eventually was discharged to hospice and died.

Although calciphylaxis is commonly seen in patients with ESRD and hyperparathyroidism, patients without renal disease also may develop the condition.2,3 Prior epidemiologic studies have shown a prevalence of 1% in patients with chronic kidney disease and up to 4% in those receiving dialysis.2-5 The average age at presentation is 48 years.6,7 Although calciphylaxis has been noted to affect males and females equally, some studies have suggested a female predominance.5-8

The etiology of calciphylaxis is unknown, but ESRD requiring dialysis, primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, obesity, diabetes mellitus, skin trauma, and/or a hypercoagulable state may put patients at increased risk for developing this disease.2,3 Other risk factors include systemic corticosteroids, liver disease, increased serum aluminum, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although high calcium-phosphate product has been noted as a risk factor in prior studies, one retrospective study found that it does not reliably confirm or exclude a diagnosis of calciphylaxis.8

The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not well understood; however, some researchers suggest that an imbalance in calcium-phosphate homeostasis may lead to calciphylaxis; that is, elevated calcium and phosphate levels exceed their solubility and deposit in the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries, which consequently leads to ischemic necrosis and gangrene of the surrounding tissue.9

Clinically, calciphylaxis has an indolent onset and usually presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish, mottled lesions that evolve into necrotic gray-black eschars and gangrene in adjacent tissues.1,5,6 The ischemic process may even extend to the muscle layer.5 Other common presentations include mild erythematous patches; livedo reticularis; painful nodules; necrotic ulcerating lesions; and more rarely flaccid, hemorrhagic, or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.6,9,10 Lesions usually begin at sites of trauma and seem to be distributed symmetrically.5,6 The most commonly affected locations are the legs, specifically the medial thighs, as well as the abdomen and buttocks, but lesions also can be found at more distal sites such as the breasts, tongue, vulva, penis, fingers, and toes.5,6,10 The head and neck region rarely is affected. Although uncommon, calciphylaxis may affect other organs, including the lungs, stomach, kidneys, and adrenal glands.5 The accompanying systemic symptoms and findings may include muscle weakness, tenderness, or myositis with rhabdomyolysis; calcific cerebral embolism; dementia and infarction of the central nervous system; acute respiratory failure; heart disease; atrioventricular block; and calcification of the cardiac conduction system.6 Unlike other forms of peripheral vascular disease, distal pulses are present in calciphylaxis, as blood flow usually is preserved distal and deep to the areas of necrosis.5,6

A careful history and thorough physical examination are important first steps in the diagnosis of this condition.2,10 Although there are no definitive laboratory tests, elevated serum calcium, phosphorous, and calcium-phosphate product levels, as well as parathyroid hormone level, may be suggestive of calciphylaxis.2,5 Leukocytosis may occur if an infection is present.5

The most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis is a deep incisional biopsy from an erythematous, slightly purpuric area adjacent to the necrotic lesion.2,10,11 The histopathologic features used to make the diagnosis include calcification of medium-sized vessels, particularly the intimal or medial layers, in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat in addition to lobular capillaries of the subcutaneous fat.5,10 These vessels, including the smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis, also may be thrombosed due to calcification, leading to vascular occlusion and subsequently ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis.10 Other findings may include pseudoxanthoma elasticum changes, panniculitis, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.4,10

The differential diagnosis for calciphylaxis includes peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, juvenile dermatomyositis, proteins C and S deficiencies, cryofibrinogenemia, calcinosis cutis, and tumoral calcinosis.2 Polyarteritis nodosa, Sjögren syndrome, atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, systemic lupus erythematosus, necrotizing fasciitis, septic embolism, and necrosis secondary to warfarin and heparin may mimic calciphylaxis.5

Treatment of calciphylaxis is multidimensional but primarily is supportive.6,11 Controlling calcium and phosphate levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism through diet and phosphate binders (eg, sevelamer hydrochloride) has been shown to be effective.6 Pamidronate, a bisphosphonate, inhibits arterial calcification in animal models and has been reported to treat calciphylaxis, resulting in marked pain reduction and ulcer healing.4,6 Cinacalcet, which functions as a calcimimetic, has been implicated in the treatment of calciphylaxis. It has been used to treat primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and to normalize serum calcium levels; it also may be used as an alternative to parathyroidectomy.4,6 Intravenous administration of sodium thiosulfate, a potent antioxidant and chelator of calcium, has been helpful in reversing signs and symptoms of calciphylaxis.6,12 It also has been shown to effectively remove extra calcium during peritoneal dialysis.6 Parathyroidectomy has been useful in patients with markedly elevated parathyroid hormone levels, as it suppresses or eliminates the sensitizing agent causing hypercalcemia, elevated calcium-phosphate product, and hyperparathyroidism.1,2,6,13

Wound care and prevention of sepsis are essential in the treatment of calciphylaxis. Management options include surgical debridement, hydrocolloid and biologic dressings, skin grafts, systemic antibiotics, oral pentoxifylline combined with maggot therapy, nutritional support, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and revascularization and amputation when other interventions have failed. Pain control with analgesics and correction of thrombosis in the skin and blood vessels via anticoagulation therapy also are important complementary treatments.6

The clinical outcome of calciphylaxis is dependent on early diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and wound management,9 but overall, the prognosis usually is poor and has a high mortality rate. The most common causes of death are infection and sepsis.1,9 A study of 7 cases reported 100% mortality,14 but other studies have suggested a mortality rate of 60% to 80%.4,10 Female sex and obesity are poor prognostic indicators.2 A better prognosis has been appreciated in cases in which lesions occur at distal sites (eg, lower legs, hands) compared to more proximal sites (eg, abdomen), where 25% and 75% mortalities have been noted, respectively.10,14,15 In one study, the overall mortality rate was 45% in patients with calciphylaxis at 1 year.6 The rate was 41% in patients with plaques only and 67% in those who presented with ulceration. Patients who survive often experience a high degree of morbidity and prolonged hospitalization; these patients often are severely debilitated, especially in the case of limb amputation.6

Our report of calciphylaxis demonstrates the diversity in clinical presentation and emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis in reducing morbidity and mortality. In our case, the patient presented with skin pain and tense nonhemorrhagic bullae without underlying ecchymotic or erythematous lesions as the earliest sign of calciphylaxis. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion in the setting of dialysis-dependent ESRD patients with bullae, extreme pain, and continuous decline. We hope that this case will help increase awareness of the varying presentations of this condition.

To the Editor:

Calciphylaxis (also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy and calcifying panniculitis) is a rare vasculopathy affecting the small vessels.1 It is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification. It is most commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hyperparathyroidism.1-3 Histopathologic features that are consistent with the diagnosis of calciphylaxis include calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat as well as smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis.4,5 Although it commonly presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish lesions that evolve into necrotic eschars, calciphylaxis rarely can present with hemorrhagic or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.1,5,6 We report this uncommon presentation to highlight the variety in clinical appearance of calciphylaxis and the importance of early diagnosis.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of chest and abdominal pain that began 1 day prior to presentation. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and ESRD secondary to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and was currently on peritoneal dialysis. The patient was admitted for peritonitis and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. At the time of admission, the patient also was noted to have several painful bullae on the legs. Her medical history also was remarkable for cerebral infarction, fibromyalgia, cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction, sciatica, hyperlipidemia, deep vein thrombosis, and seizures. She had no history of herpes simplex virus. Surgical history was remarkable for tubal ligation, nephrectomy and kidney transplant, parathyroidectomy, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s medications included sevelamer carbonate, prednisone, epogen, calcium carbonate, esomeprazole, ondansetron, topical gentamicin, and atorvastatin.

Skin examination was performed by the inpatient dermatology service and revealed several tense, 1- to 5-cm, nonhemorrhagic bullae on the thighs and lower legs, some that had ruptured. The lesions were notably tender to palpation. No surrounding erythema, ecchymosis, or warmth was appreciated. The Nikolsky sign was negative. The patient also was noted to have at least grade 2 to 3+ pitting edema of the bilateral legs. The oral and conjunctival mucosae were unremarkable.

Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibody levels were negative. A punch biopsy of the left lateral thigh revealed intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis with dermal edema suggestive of edema bullae and direct immunofluorescence was negative for immune complex and complement deposition.

Conservative therapy with wound care was recommended. The patient continued to report persistent severe skin pain and developed a subcutaneous nodule on the right inner thigh 1 week later, prompting a second biopsy. Results of the excisional biopsy were nondiagnostic but were suggestive of calciphylaxis, revealing subepidermal bullae with epidermal necrosis, a scant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasated erythrocytes. No evidence of calcification was seen within the vessels. The patient was then started on sodium thiosulfate with hemodialysis for treatment of presumed calciphylaxis.

Despite meticulous wound care and treatment with sodium thiosulfate, the patient developed ulcerations with necrotic eschars on the bilateral buttocks, hips, and thighs 1 month later (Figure 1). She subsequently worsened over the next few weeks. She developed sepsis and was transferred to the intensive care unit. A third biopsy was performed, finally confirming the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Histopathology revealed small blood vessels with basophilic granular deposits in the walls consistent with calcium in the subcutaneous tissue (highlighted with the von Kossa stain), as well as thrombi in the lumens of some vessels; early fat necrosis; focal epidermal necrosis with underlying congested blood vessels with deposits in their walls; a perivascular infiltrate predominately of lymphocytes and neutrophils with scattered nuclear dust; and thick, hyalinized, closely crowded collagen bundles in the reticular dermis and in a widened subcutaneous septum (Figures 2 and 3).

Supportive care and pain control were continued, but the overall prognosis was determined to be very poor, and the patient eventually was discharged to hospice and died.

Although calciphylaxis is commonly seen in patients with ESRD and hyperparathyroidism, patients without renal disease also may develop the condition.2,3 Prior epidemiologic studies have shown a prevalence of 1% in patients with chronic kidney disease and up to 4% in those receiving dialysis.2-5 The average age at presentation is 48 years.6,7 Although calciphylaxis has been noted to affect males and females equally, some studies have suggested a female predominance.5-8

The etiology of calciphylaxis is unknown, but ESRD requiring dialysis, primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, obesity, diabetes mellitus, skin trauma, and/or a hypercoagulable state may put patients at increased risk for developing this disease.2,3 Other risk factors include systemic corticosteroids, liver disease, increased serum aluminum, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although high calcium-phosphate product has been noted as a risk factor in prior studies, one retrospective study found that it does not reliably confirm or exclude a diagnosis of calciphylaxis.8

The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not well understood; however, some researchers suggest that an imbalance in calcium-phosphate homeostasis may lead to calciphylaxis; that is, elevated calcium and phosphate levels exceed their solubility and deposit in the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries, which consequently leads to ischemic necrosis and gangrene of the surrounding tissue.9

Clinically, calciphylaxis has an indolent onset and usually presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish, mottled lesions that evolve into necrotic gray-black eschars and gangrene in adjacent tissues.1,5,6 The ischemic process may even extend to the muscle layer.5 Other common presentations include mild erythematous patches; livedo reticularis; painful nodules; necrotic ulcerating lesions; and more rarely flaccid, hemorrhagic, or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.6,9,10 Lesions usually begin at sites of trauma and seem to be distributed symmetrically.5,6 The most commonly affected locations are the legs, specifically the medial thighs, as well as the abdomen and buttocks, but lesions also can be found at more distal sites such as the breasts, tongue, vulva, penis, fingers, and toes.5,6,10 The head and neck region rarely is affected. Although uncommon, calciphylaxis may affect other organs, including the lungs, stomach, kidneys, and adrenal glands.5 The accompanying systemic symptoms and findings may include muscle weakness, tenderness, or myositis with rhabdomyolysis; calcific cerebral embolism; dementia and infarction of the central nervous system; acute respiratory failure; heart disease; atrioventricular block; and calcification of the cardiac conduction system.6 Unlike other forms of peripheral vascular disease, distal pulses are present in calciphylaxis, as blood flow usually is preserved distal and deep to the areas of necrosis.5,6

A careful history and thorough physical examination are important first steps in the diagnosis of this condition.2,10 Although there are no definitive laboratory tests, elevated serum calcium, phosphorous, and calcium-phosphate product levels, as well as parathyroid hormone level, may be suggestive of calciphylaxis.2,5 Leukocytosis may occur if an infection is present.5

The most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis is a deep incisional biopsy from an erythematous, slightly purpuric area adjacent to the necrotic lesion.2,10,11 The histopathologic features used to make the diagnosis include calcification of medium-sized vessels, particularly the intimal or medial layers, in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat in addition to lobular capillaries of the subcutaneous fat.5,10 These vessels, including the smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis, also may be thrombosed due to calcification, leading to vascular occlusion and subsequently ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis.10 Other findings may include pseudoxanthoma elasticum changes, panniculitis, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.4,10

The differential diagnosis for calciphylaxis includes peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, juvenile dermatomyositis, proteins C and S deficiencies, cryofibrinogenemia, calcinosis cutis, and tumoral calcinosis.2 Polyarteritis nodosa, Sjögren syndrome, atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, systemic lupus erythematosus, necrotizing fasciitis, septic embolism, and necrosis secondary to warfarin and heparin may mimic calciphylaxis.5

Treatment of calciphylaxis is multidimensional but primarily is supportive.6,11 Controlling calcium and phosphate levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism through diet and phosphate binders (eg, sevelamer hydrochloride) has been shown to be effective.6 Pamidronate, a bisphosphonate, inhibits arterial calcification in animal models and has been reported to treat calciphylaxis, resulting in marked pain reduction and ulcer healing.4,6 Cinacalcet, which functions as a calcimimetic, has been implicated in the treatment of calciphylaxis. It has been used to treat primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and to normalize serum calcium levels; it also may be used as an alternative to parathyroidectomy.4,6 Intravenous administration of sodium thiosulfate, a potent antioxidant and chelator of calcium, has been helpful in reversing signs and symptoms of calciphylaxis.6,12 It also has been shown to effectively remove extra calcium during peritoneal dialysis.6 Parathyroidectomy has been useful in patients with markedly elevated parathyroid hormone levels, as it suppresses or eliminates the sensitizing agent causing hypercalcemia, elevated calcium-phosphate product, and hyperparathyroidism.1,2,6,13

Wound care and prevention of sepsis are essential in the treatment of calciphylaxis. Management options include surgical debridement, hydrocolloid and biologic dressings, skin grafts, systemic antibiotics, oral pentoxifylline combined with maggot therapy, nutritional support, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and revascularization and amputation when other interventions have failed. Pain control with analgesics and correction of thrombosis in the skin and blood vessels via anticoagulation therapy also are important complementary treatments.6

The clinical outcome of calciphylaxis is dependent on early diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and wound management,9 but overall, the prognosis usually is poor and has a high mortality rate. The most common causes of death are infection and sepsis.1,9 A study of 7 cases reported 100% mortality,14 but other studies have suggested a mortality rate of 60% to 80%.4,10 Female sex and obesity are poor prognostic indicators.2 A better prognosis has been appreciated in cases in which lesions occur at distal sites (eg, lower legs, hands) compared to more proximal sites (eg, abdomen), where 25% and 75% mortalities have been noted, respectively.10,14,15 In one study, the overall mortality rate was 45% in patients with calciphylaxis at 1 year.6 The rate was 41% in patients with plaques only and 67% in those who presented with ulceration. Patients who survive often experience a high degree of morbidity and prolonged hospitalization; these patients often are severely debilitated, especially in the case of limb amputation.6

Our report of calciphylaxis demonstrates the diversity in clinical presentation and emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis in reducing morbidity and mortality. In our case, the patient presented with skin pain and tense nonhemorrhagic bullae without underlying ecchymotic or erythematous lesions as the earliest sign of calciphylaxis. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion in the setting of dialysis-dependent ESRD patients with bullae, extreme pain, and continuous decline. We hope that this case will help increase awareness of the varying presentations of this condition.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;57:1021-1025.

- Somorin AO, Harbi AA, Subaity Y, et al. Calciphylaxis: case report and literature review. Afr J Med Sci. 2002;31:175-178.

- Barreiros HM, Goulão J, Cunha H, et al. Calciphylaxis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;2:69-70.

- Vedvyas C, Winterfield LS, Vleugels RA. Calciphylaxis: a systematic review of existing and emerging therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E253-E260.

- Beitz JM. Calciphylaxis: a case study with differential diagnosis. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2003;49:28-38.

- Daudén E, Oñate M. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:557-568.

- Oh DH, Eulau D, Tokugawa DA, et al. Five cases of calciphylaxis and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:979-987.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MDP, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-578.

- Hanvesakul R, Silva MA, Hejmadi R, et al. Calciphylaxis following kidney transplantation: a case report. J Med Cases. 2009;3:9297.

- Kouba DJ, Owens NM, Barrett TL, et al. An unusual case of calciphylaxis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:19-22.

- Arch-Ferrer JE, Beenken SW, Rue LW, et al. Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis. Surgery. 2003;134:941-945.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Mirza I, Chaubay D, Gunderia H, et al. An unusual presentation of calciphylaxis due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1351-1353.

- Alain J, Poulin YP, Cloutier RA, et al. Calciphylaxis: seven new cases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:213-218.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;57:1021-1025.

- Somorin AO, Harbi AA, Subaity Y, et al. Calciphylaxis: case report and literature review. Afr J Med Sci. 2002;31:175-178.

- Barreiros HM, Goulão J, Cunha H, et al. Calciphylaxis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;2:69-70.

- Vedvyas C, Winterfield LS, Vleugels RA. Calciphylaxis: a systematic review of existing and emerging therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E253-E260.

- Beitz JM. Calciphylaxis: a case study with differential diagnosis. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2003;49:28-38.

- Daudén E, Oñate M. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:557-568.

- Oh DH, Eulau D, Tokugawa DA, et al. Five cases of calciphylaxis and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:979-987.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MDP, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-578.

- Hanvesakul R, Silva MA, Hejmadi R, et al. Calciphylaxis following kidney transplantation: a case report. J Med Cases. 2009;3:9297.

- Kouba DJ, Owens NM, Barrett TL, et al. An unusual case of calciphylaxis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:19-22.

- Arch-Ferrer JE, Beenken SW, Rue LW, et al. Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis. Surgery. 2003;134:941-945.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Mirza I, Chaubay D, Gunderia H, et al. An unusual presentation of calciphylaxis due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1351-1353.

- Alain J, Poulin YP, Cloutier RA, et al. Calciphylaxis: seven new cases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:213-218.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

Practice Points

- Calciphylaxis is a rare microvascular occlusion syndrome characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification.

- Clinically, lesions present with severely painful, violaceous, retiform patches and plaques, and less commonly bullae that progress to necrotic ulcers on the buttocks, legs, or abdomen, which is most often associated with end-stage renal disease and hyperparathyroidism.

- The diagnosis is made through deep wedge or excisional biopsy and shows calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat. Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach, but morbidity and mortality remain high.

Are CRMO and SAPHO syndrome one and the same?

MAUI, HAWAII – Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) in children and SAPHO syndrome in adults may well be a single clinical syndrome.

That contention, recently put forth by Austrian investigators, resonates with Anne M. Stevens, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at the University of Washington, Seattle, and senior director for the adaptive immunity research program at Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

“Is CRMO just for kids? No,” she asserted at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

First off, she noted that the nomenclature is shifting: The more familiar acronym CRMO is giving way to CNO (chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis) in light of evidence that roughly 30% of patients with CRMO start out with a single characteristic bone lesion, with the disease turning multifocal in the subsequent 4 years in the great majority of cases.

SAPHO syndrome – an acronym for synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis – a formerly obscure disease entity first described in 1987 in France, has suddenly become a trendy research topic, with three small studies presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

CNO is a pediatric autoinflammatory bone disease characterized by sterile bone lesions, most often on the clavicle, spine, mandible, and lower extremities. It is marked by prominent focal bone and/or joint pain, worse at night, with or without swelling. With no agreed-upon diagnostic criteria or biomarkers, CNO is a diagnosis of exclusion. Two-thirds of the time the condition is initially misdiagnosed as bacterial osteomyelitis or a malignant tumor.

Austrian investigators at the University of Graz recently conducted a retrospective comparison of 24 pediatric patients diagnosed with CNO and 10 adults with SAPHO syndrome. The median age at diagnosis of CNO was 12.3 years versus 32.5 years for SAPHO syndrome. The two groups shared compelling similarities in mean number of bone lesions, prevalence of skin involvement, and other aspects of initial clinical presentation, as well as laboratory and histopathologic findings on bone biopsy.

There were, however, several notable clinical differences in this small dataset: CNO bone lesions affected mainly the lower extremities, clavicle, spine, and mandible, while SAPHO syndrome more commonly involved the sternum (50% vs. 8%) and vertebrae (50% vs. 21%). Also, the most frequent cutaneous manifestation was palmoplantar pustulosis in adults with SAPHO syndrome, while severe acne predominated in children with CNO. In both children and adults, the skin lesions most often arose after the bone symptoms, making early diagnosis a challenge.

Another similarity: Although there have been no randomized treatment trials in either CNO or SAPHO syndrome, case series suggest the same treatments are effective for both, with NSAIDs as first line, followed by nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, or bisphosphonates.

CNO diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up

Various investigators have pegged the sensitivity of physical examination for diagnosis of CNO at 31%, radiographs at a lowly 13%, and bone scintigraphy at 74%, all in comparison with MRI.

“Our go-to now is MRI with STIR [short tau inversion recovery],” according to Dr. Stevens. “There’s no contrast – so no IV – no radiation, and it’s fast, 20 minutes for a whole body MRI in a little kid, 45 minutes in a big one.”

Insurers are reluctant to pay for serial whole-body MRIs for patient follow-up, so it’s often necessary to order a series of images covering different body parts.

Her University of Washington colleague Dan Zhao, MD, PhD, is developing infrared thermal imaging as an inexpensive, convenient alternative to MRI which could theoretically be done at home. In a pilot study in 30 children with CNO and 31 controls, inflamed leg segments showed significantly higher temperatures. Larger studies are planned.

Dr. Stevens advised leaning towards a diagnosis of CNO with avoidance of bone biopsy in a patient with multifocal osteomyelitis at the typical sites, a normal CBC, the typical extraosseous manifestations, and normal or only mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in an otherwise well-appearing child. In contrast, strongly consider a bone biopsy to rule out malignancy or infection if the child has unexplained highly elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cytopenia, high fever, excessive pain, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or suspicious imaging findings.

German rheumatologists have developed a clinical score for diagnosis of CNO. A normal blood cell count gets 13 points; symmetric bone lesions 10; lesions with marginal sclerosis 10; a normal body temperature 9; two or more radiologically proven lesions 7; a C-reactive protein of 1 mg/dL or greater 6; and vertebral, clavicular, or sternal lesions 8. A score of 39 points or more out of a possible 63 had a 97% positive predictive value for CNO in a retrospective study of 224 children with CNO, proven bacterial osteomyelitis, or malignant bone tumors. A score of 28 points or less had a 97% negative predictive value for CNO. An indeterminate score of 29-38 warrants close monitoring.

The scoring system hasn’t been validated, but most pediatric rheumatologists agree that it’s useful, according to Dr. Stevens.

The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) is in the process of developing standardized diagnostic and classification criteria and treatment plans for CNO. Dr. Zhao was first author of a CARRA consensus treatment plan for CNO refractory to NSAID monotherapy. The plan for the first 12 months includes three options: methotrexate or sulfasalazine, TNF inhibitors with or without methotrexate, and bisphosphonates.

“The main point of this is you try a medicine and then wait 3 months. If they’re not responding then, switch medicines or add another drug. Monitor every 3 months based upon pain,” she said.

Dr. Stevens reported research collaborations with Kineta and Seattle Genetics in addition to her employment at Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

MAUI, HAWAII – Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) in children and SAPHO syndrome in adults may well be a single clinical syndrome.

That contention, recently put forth by Austrian investigators, resonates with Anne M. Stevens, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at the University of Washington, Seattle, and senior director for the adaptive immunity research program at Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

“Is CRMO just for kids? No,” she asserted at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

First off, she noted that the nomenclature is shifting: The more familiar acronym CRMO is giving way to CNO (chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis) in light of evidence that roughly 30% of patients with CRMO start out with a single characteristic bone lesion, with the disease turning multifocal in the subsequent 4 years in the great majority of cases.

SAPHO syndrome – an acronym for synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis – a formerly obscure disease entity first described in 1987 in France, has suddenly become a trendy research topic, with three small studies presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

CNO is a pediatric autoinflammatory bone disease characterized by sterile bone lesions, most often on the clavicle, spine, mandible, and lower extremities. It is marked by prominent focal bone and/or joint pain, worse at night, with or without swelling. With no agreed-upon diagnostic criteria or biomarkers, CNO is a diagnosis of exclusion. Two-thirds of the time the condition is initially misdiagnosed as bacterial osteomyelitis or a malignant tumor.

Austrian investigators at the University of Graz recently conducted a retrospective comparison of 24 pediatric patients diagnosed with CNO and 10 adults with SAPHO syndrome. The median age at diagnosis of CNO was 12.3 years versus 32.5 years for SAPHO syndrome. The two groups shared compelling similarities in mean number of bone lesions, prevalence of skin involvement, and other aspects of initial clinical presentation, as well as laboratory and histopathologic findings on bone biopsy.

There were, however, several notable clinical differences in this small dataset: CNO bone lesions affected mainly the lower extremities, clavicle, spine, and mandible, while SAPHO syndrome more commonly involved the sternum (50% vs. 8%) and vertebrae (50% vs. 21%). Also, the most frequent cutaneous manifestation was palmoplantar pustulosis in adults with SAPHO syndrome, while severe acne predominated in children with CNO. In both children and adults, the skin lesions most often arose after the bone symptoms, making early diagnosis a challenge.

Another similarity: Although there have been no randomized treatment trials in either CNO or SAPHO syndrome, case series suggest the same treatments are effective for both, with NSAIDs as first line, followed by nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, or bisphosphonates.

CNO diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up

Various investigators have pegged the sensitivity of physical examination for diagnosis of CNO at 31%, radiographs at a lowly 13%, and bone scintigraphy at 74%, all in comparison with MRI.

“Our go-to now is MRI with STIR [short tau inversion recovery],” according to Dr. Stevens. “There’s no contrast – so no IV – no radiation, and it’s fast, 20 minutes for a whole body MRI in a little kid, 45 minutes in a big one.”

Insurers are reluctant to pay for serial whole-body MRIs for patient follow-up, so it’s often necessary to order a series of images covering different body parts.

Her University of Washington colleague Dan Zhao, MD, PhD, is developing infrared thermal imaging as an inexpensive, convenient alternative to MRI which could theoretically be done at home. In a pilot study in 30 children with CNO and 31 controls, inflamed leg segments showed significantly higher temperatures. Larger studies are planned.

Dr. Stevens advised leaning towards a diagnosis of CNO with avoidance of bone biopsy in a patient with multifocal osteomyelitis at the typical sites, a normal CBC, the typical extraosseous manifestations, and normal or only mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in an otherwise well-appearing child. In contrast, strongly consider a bone biopsy to rule out malignancy or infection if the child has unexplained highly elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cytopenia, high fever, excessive pain, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or suspicious imaging findings.

German rheumatologists have developed a clinical score for diagnosis of CNO. A normal blood cell count gets 13 points; symmetric bone lesions 10; lesions with marginal sclerosis 10; a normal body temperature 9; two or more radiologically proven lesions 7; a C-reactive protein of 1 mg/dL or greater 6; and vertebral, clavicular, or sternal lesions 8. A score of 39 points or more out of a possible 63 had a 97% positive predictive value for CNO in a retrospective study of 224 children with CNO, proven bacterial osteomyelitis, or malignant bone tumors. A score of 28 points or less had a 97% negative predictive value for CNO. An indeterminate score of 29-38 warrants close monitoring.

The scoring system hasn’t been validated, but most pediatric rheumatologists agree that it’s useful, according to Dr. Stevens.

The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) is in the process of developing standardized diagnostic and classification criteria and treatment plans for CNO. Dr. Zhao was first author of a CARRA consensus treatment plan for CNO refractory to NSAID monotherapy. The plan for the first 12 months includes three options: methotrexate or sulfasalazine, TNF inhibitors with or without methotrexate, and bisphosphonates.

“The main point of this is you try a medicine and then wait 3 months. If they’re not responding then, switch medicines or add another drug. Monitor every 3 months based upon pain,” she said.

Dr. Stevens reported research collaborations with Kineta and Seattle Genetics in addition to her employment at Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

MAUI, HAWAII – Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) in children and SAPHO syndrome in adults may well be a single clinical syndrome.

That contention, recently put forth by Austrian investigators, resonates with Anne M. Stevens, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at the University of Washington, Seattle, and senior director for the adaptive immunity research program at Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

“Is CRMO just for kids? No,” she asserted at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

First off, she noted that the nomenclature is shifting: The more familiar acronym CRMO is giving way to CNO (chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis) in light of evidence that roughly 30% of patients with CRMO start out with a single characteristic bone lesion, with the disease turning multifocal in the subsequent 4 years in the great majority of cases.

SAPHO syndrome – an acronym for synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis – a formerly obscure disease entity first described in 1987 in France, has suddenly become a trendy research topic, with three small studies presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

CNO is a pediatric autoinflammatory bone disease characterized by sterile bone lesions, most often on the clavicle, spine, mandible, and lower extremities. It is marked by prominent focal bone and/or joint pain, worse at night, with or without swelling. With no agreed-upon diagnostic criteria or biomarkers, CNO is a diagnosis of exclusion. Two-thirds of the time the condition is initially misdiagnosed as bacterial osteomyelitis or a malignant tumor.

Austrian investigators at the University of Graz recently conducted a retrospective comparison of 24 pediatric patients diagnosed with CNO and 10 adults with SAPHO syndrome. The median age at diagnosis of CNO was 12.3 years versus 32.5 years for SAPHO syndrome. The two groups shared compelling similarities in mean number of bone lesions, prevalence of skin involvement, and other aspects of initial clinical presentation, as well as laboratory and histopathologic findings on bone biopsy.

There were, however, several notable clinical differences in this small dataset: CNO bone lesions affected mainly the lower extremities, clavicle, spine, and mandible, while SAPHO syndrome more commonly involved the sternum (50% vs. 8%) and vertebrae (50% vs. 21%). Also, the most frequent cutaneous manifestation was palmoplantar pustulosis in adults with SAPHO syndrome, while severe acne predominated in children with CNO. In both children and adults, the skin lesions most often arose after the bone symptoms, making early diagnosis a challenge.

Another similarity: Although there have been no randomized treatment trials in either CNO or SAPHO syndrome, case series suggest the same treatments are effective for both, with NSAIDs as first line, followed by nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, or bisphosphonates.

CNO diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up

Various investigators have pegged the sensitivity of physical examination for diagnosis of CNO at 31%, radiographs at a lowly 13%, and bone scintigraphy at 74%, all in comparison with MRI.

“Our go-to now is MRI with STIR [short tau inversion recovery],” according to Dr. Stevens. “There’s no contrast – so no IV – no radiation, and it’s fast, 20 minutes for a whole body MRI in a little kid, 45 minutes in a big one.”

Insurers are reluctant to pay for serial whole-body MRIs for patient follow-up, so it’s often necessary to order a series of images covering different body parts.

Her University of Washington colleague Dan Zhao, MD, PhD, is developing infrared thermal imaging as an inexpensive, convenient alternative to MRI which could theoretically be done at home. In a pilot study in 30 children with CNO and 31 controls, inflamed leg segments showed significantly higher temperatures. Larger studies are planned.

Dr. Stevens advised leaning towards a diagnosis of CNO with avoidance of bone biopsy in a patient with multifocal osteomyelitis at the typical sites, a normal CBC, the typical extraosseous manifestations, and normal or only mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in an otherwise well-appearing child. In contrast, strongly consider a bone biopsy to rule out malignancy or infection if the child has unexplained highly elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cytopenia, high fever, excessive pain, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or suspicious imaging findings.

German rheumatologists have developed a clinical score for diagnosis of CNO. A normal blood cell count gets 13 points; symmetric bone lesions 10; lesions with marginal sclerosis 10; a normal body temperature 9; two or more radiologically proven lesions 7; a C-reactive protein of 1 mg/dL or greater 6; and vertebral, clavicular, or sternal lesions 8. A score of 39 points or more out of a possible 63 had a 97% positive predictive value for CNO in a retrospective study of 224 children with CNO, proven bacterial osteomyelitis, or malignant bone tumors. A score of 28 points or less had a 97% negative predictive value for CNO. An indeterminate score of 29-38 warrants close monitoring.

The scoring system hasn’t been validated, but most pediatric rheumatologists agree that it’s useful, according to Dr. Stevens.

The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) is in the process of developing standardized diagnostic and classification criteria and treatment plans for CNO. Dr. Zhao was first author of a CARRA consensus treatment plan for CNO refractory to NSAID monotherapy. The plan for the first 12 months includes three options: methotrexate or sulfasalazine, TNF inhibitors with or without methotrexate, and bisphosphonates.

“The main point of this is you try a medicine and then wait 3 months. If they’re not responding then, switch medicines or add another drug. Monitor every 3 months based upon pain,” she said.

Dr. Stevens reported research collaborations with Kineta and Seattle Genetics in addition to her employment at Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2020

Spotlight on SMA, Part 2: The Spinal Muscular Atrophy Treatment Landscape

With newly available disease-modifying therapies, the phenotype of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is rapidly changing, and affected individuals are living longer, healthier lives.1-4 This supplement discusses therapeutic strategies, FDA-approved treatment options, and the SMA drug pipeline.

To access Part 1 of the SMA Spotlight series, The Urgent Need for Early Diagnosis in Spinal Muscular Atrophy, visit www.mdedge.com/DiagnosisInSMA.

References

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723-1732.

- Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):625-635.

- Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, et al. Single-dose genereplacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1713-1722.

- De Vivo DC, Bertini E, Swoboda KJ, et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: Interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(11):842-856.

With newly available disease-modifying therapies, the phenotype of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is rapidly changing, and affected individuals are living longer, healthier lives.1-4 This supplement discusses therapeutic strategies, FDA-approved treatment options, and the SMA drug pipeline.

To access Part 1 of the SMA Spotlight series, The Urgent Need for Early Diagnosis in Spinal Muscular Atrophy, visit www.mdedge.com/DiagnosisInSMA.

References

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723-1732.

- Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):625-635.

- Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, et al. Single-dose genereplacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1713-1722.

- De Vivo DC, Bertini E, Swoboda KJ, et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: Interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(11):842-856.

With newly available disease-modifying therapies, the phenotype of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is rapidly changing, and affected individuals are living longer, healthier lives.1-4 This supplement discusses therapeutic strategies, FDA-approved treatment options, and the SMA drug pipeline.

To access Part 1 of the SMA Spotlight series, The Urgent Need for Early Diagnosis in Spinal Muscular Atrophy, visit www.mdedge.com/DiagnosisInSMA.

References

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723-1732.

- Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):625-635.

- Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, et al. Single-dose genereplacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1713-1722.

- De Vivo DC, Bertini E, Swoboda KJ, et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: Interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(11):842-856.

Dermatology therapies evolve as disease knowledge and investment grow

For much of the past 50 years, many of the drugs used in dermatology have been adopted – and often adapted – from other specialties and used for dermatologic conditions.

“Almost every drug was more or less a hand-me-down” developed first for cancer or other diseases and found later, often serendipitously, to be useful for the skin, said William Eaglstein, MD, thinking back to the 1970s and recalling steroids, tetracyclines, methotrexate, and 5-flourouracil. “The perception always was that skin diseases weren’t serious, that the market was small.”

Much has changed. by dermatologist investigators, and “more and more companies are recognizing the importance of our diseases and the ability to get a return on investment,” said Dr. Eaglstein, past professor and chair of the departments of dermatology at the University of Miami and the University of Pittsburgh, who worked in industry after his academic career.

Psoriasis was a game changer, he and other dermatologists said in interviews. The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha blockers were first used for other indications, but their marked follow-on success in psoriasis “offered proof of concept clinically – showing that by targeting immune pathways in the skin we could achieve a clinical effect – and proof of concept commercially” that dermatology drugs are worth pursuing by pharmaceutical companies, said William Ju, MD, a cofounder and president of Advancing Innovation in Dermatology, a nonprofit organization that brings together stakeholders to develop novel dermatologic drugs and products.

This resulted in the approval of subsequent biologics, such as ustekinumab (Stelara) which inhibits the signaling of interleukin (IL)–12/IL-23, for psoriasis as their initial indication. Then, biologics targeting IL-17 followed this dermatology-first approach. “Researchers have continued further dissecting out the immunopathological pathways, and antibody drugs targeting IL-23p19 have been approved for psoriasis as the lead indication,” said Dr. Ju, a dermatologist who has worked in industry.

Seth Orlow, MD, PhD, who chairs the department of dermatology at NYU Langone Health, remembers the 1970s through the 1990s as the “era of topicals” developed for dermatologic conditions – topical antifungals, topical corticosteroids, and topical retinoids. The next decade was characterized by formulation tweaks and few novel treatments for dermatology, said Dr. Orlow, who is also professor of pediatric dermatology and director of the program in cutaneous biology at New York University.

Now, given the succession of psoriasis discoveries in the last decade, “large companies are interested in dermatology,” he said in an interview. “There’s an explosion of interest in atopic dermatitis. … and companies are dipping their toes in the water for alopecia areata and vitiligo. That’s amazing.”

Rare diseases like epidermolysis bullosa, ichthyosis, and basal cell nevus syndrome are getting attention as well, boosted by the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, in addition to increased research on disease pathways and growing appreciation of skin diseases. “There’s a lot under development, from small molecules to biologics to gene-based therapies,” Dr. Orlow commented.

The new frontier of atopic dermatitis

The approval in 2017 of dupilumab (Dupixent), a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the signaling of both IL-4 and IL-13) for moderate-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults illustrates the new standing of dermatologic diseases in the field of drug development and commercialization. “Atopic dermatitis had always been the forgotten chronic disease in dermatology. … We’ve had no good treatments,” said Eric Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “Dupilumab coming to the forefront [as a dermatology-first indication] has changed the entire perspective of the field. … Everyone is now trying to find the next best drug.”

As with psoriasis, a targeted therapy for AD was made possible by the development in the 1990s of monoclonal antibody technology and the ensuing ability to create biologics that target specific molecules in the body – as well as bedside-to-bench research that homed in on the involvement of particular cytokines.

But there also is a “new understanding of the burden of the disease,” Dr. Simpson observed. In the last 5 years, he said, research funded by the National Eczema Association documented that AD “not only causes inflammation of the skin … but that it affects people at school and in the workplace, that people have multiple mental health comorbidities and skin infections, and that the disease profoundly affects the entire patient in ways that weren’t really recognized or appreciated.”

Having evolved in the footsteps of psoriasis, AD is at a higher starting point in terms of the safety and efficacy of its first biologic, sources said. On the other hand, AD is a much more complex and heterogeneous disease, and researchers are trying to determine which immune pathways and cytokines are most important – and in which populations.

“We’re at the beginning. We’re trying to figure out how to get 80% of patients clear or almost clear [as we can now with psoriasis biologics] rather than almost 40% [as in the dupilumab pivotal trials],” said Dr. Simpson, former cochair of the National Eczema Association’s scientific committee. Public data from ongoing phase 2 and 3 trials of other Th2 cytokine inhibitors suggest that 25%-45% of enrolled patients achieve high levels of clearance, he noted.

Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, Sol and Clara Kest Professor and vice-chair for research in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said that AD’s heterogeneity involves “many factors, like ethnicity, age … and whether they have an atopic background such as asthma.”

Her research is showing, for instance, that AD in Asian and black patients is different than AD in European-American patients, and that the presence of comorbidities may well have treatment implications. She has also shown that children may have a different phenotype than adults, with greater activation of the Th17 axis that typifies psoriasis.

“For certain patients, we may need to target more than one pathway, or target a different pathway than the Th2 pathway. And treatment may be different in the setting of comorbidities,” said Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who is also director of the laboratory of inflammatory skin diseases at Mount Sinai. “We may think of one treatment – dupilumab, for example – for someone who has asthma and AD. But for patients who don’t have asthma and are Asian, for instance, or for children, we may need additional agents.”

Her research over the years on AD has taught her the importance of human studies over mouse model studies; it was in humans, she noted, that she and other investigators demonstrated “without doubt” that AD is an immune disease and not simply a barrier disease. The Th2 cytokine pathway appears to play the predominant role in AD, though “there still is a strong Th1 component,” she said.

“We’re in a better position to figure this out today [than in the past 20 or even 10 years],” said Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who recalls being told years ago that AD was a “dead end,” that it “would kill [her] career.” Given the evolution of science and the recognition of comorbidities and seriousness of dermatologic diseases, “the stars are aligned to get more [therapies] to these patients.”

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are among these therapies. Three JAK inhibitors are in or have recently completed phase 3 studies for AD; two are currently approved for rheumatoid arthritis, and the other has been designed specifically for AD, Dr. Simpson pointed out. The drugs are oral small molecule drugs that block the JAK signaling pathways for certain proinflammatory cytokines.

“The JAK inhibitors are a real exciting story for dermatology,” he said. “Theoretically, by blocking more cytokines than biologics do, there could be some safety issues – that’s why we’re awaiting big phase 3 study results so we can figure out the risk-benefit balance and guide our patients as to which drug is best.”

Andrew Blauvelt, MD, MBA, president of Oregon Medical Research Center in Portland – a stand-alone dermatology clinical trial center founded in 1998 – likes to envision the evolution of drugs for dermatologic conditions as a funnel, with the most broad-acting drugs at the wide top of the funnel and the most targeted drugs at the bottom tip.

JAK inhibitors, he said, sit near the middle – more targeted and safer than cyclosporine and methotrexate, for instance, but not as targeted as the biologics now available for psoriasis and being developed for AD. “The oral medications that have been developed for psoriasis and those coming for AD are not quite as targeted to the disease,” he noted. “JAK inhibitors have great efficacy – it’s more a question of safety and being able to treat without causing collateral damage.”

Dr. Blauvelt expects the armamentarium of new drugs approved for AD to go from one (dupilumab) to seven within the next 2 years. This will include three new biologics and three new oral JAK inhibitors, he predicts. As the specialty sorts through and integrates these new drugs into practice, dermatologists will increasingly personalize treatment and will face the “nonscientific” challenge of the cost of new therapies and patient access to them, he noted.

In the meantime, said Dr. Simpson, recent drug discoveries have driven more non–pharmaceutical-funded translational research aimed at understanding the underlying biology of AD. The National Institutes of Health, for instance, “is interested in dupilumab and its impact on the skin barrier and skin defense mechanisms,” he said. “We’ll learn a lot more [in coming years].”

Spillover to other diseases

JAK inhibitors – some in oral and some in topical form – are showing efficacy in ongoing research for alopecia areata (AA) and vitiligo as well, Dr. Blauvelt said.

“We’re understanding more about the pathophysiology of these diseases, which historically have been tough diseases for dermatologists to treat,” he said. “The successes in alopecia areata and vitiligo are incredibly exciting actually – it’s very exciting to see hair and pigment coming back. And as we learn more, we should be able to develop [additional] drugs that are more disease targeted than the JAK inhibitors.”

Already, some of the biologics used to treat psoriasis have been studied in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease in which painful lumps and sometimes tunnels form under the skin, with some success; adalimumab (Humira), a TNF-inhibitor, is now FDA approved for the treatment of moderate-severe HS, and studies are ongoing of IL-17 and IL-23 blockers for the disease.

“The pathophysiology [of HS] is very complex; it’s not nearly as straightforward as psoriasis, and there haven’t been any major breakthroughs yet,” Dr. Blauvelt said. “But the drugs seem to be working better than historical alternatives.”

Regarding AA, Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who is participating in a study of dupilumab for AA, recently found in a retrospective cross-sectional study that patients with the condition are more likely to have atopic comorbidities – asthma, allergic rhinitis, and AD, for instance. “The more comorbid conditions, the greater the risk of developing alopecia areata,” she said. “That could point to a potential pathogenic role of the Th2 axis in the disorder [challenging the traditional view of AA as a singularly Th1-centered disease.] The future will tell.”

Action on rare skin diseases

Both large and small companies have moved into the orphan drug space, investing in research and pursuing orphan drug indications for dermatologic conditions, because “it’s clear now in the marketplace that companies can develop effective drugs for rare disorders and be quite successful,” Dr. Orlow said.

According to a recent analysis, as a result of incentives for rare disease drug development contained in the Orphan Drug Act, 72 indications have been approved for rare skin disease, skin-related cancers, and hereditary disorders with prominent dermatologic manifestations since the law was passed in 1983 (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019;81[3]:867-77).

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a good example, he and other sources said, of commercial interests merging with growing knowledge of disease pathogenesis as well as the tools needed to develop new treatments.