User login

Impact of Pregnancy on Rosacea Unpredictable, Study Suggests

TOPLINE:

Among women diagnosed with rosacea, the impact of pregnancy on the disease is unpredictable.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a telephone survey of 39 women with a diagnosis of rosacea in the electronic medical records prior to the onset of pregnancy who had been admitted to Oregon Health & Science University for labor and delivery from June 27, 2015, to June 27, 2020.

- Patient global assessment of clear (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) rosacea was rated across five timepoints: 1-3 months preconception; first, second, and third trimesters; and 6 weeks postpartum.

TAKEAWAY:

- The mean age of the survey participants was 35.5 years, the mean gestational age at delivery was 39.4 weeks, and most had singleton pregnancies.

- All but one study participant (97.4%) reported symptoms of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, while 26 (67%) reported symptoms of papulopustular rosacea.

- Nearly half of the participants (19, 48.7%) said their rosacea worsened during pregnancy, 13 (33.3%) reported no change in rosacea severity during pregnancy, and 7 (17.9%) reported that their rosacea improved during pregnancy.

- Before conceiving, the mean rosacea severity score among participants was mild (1.10; 95% CI, 0.92-1.29) and did not change significantly over time, a reflection of individual variations. In addition, 83.3% of participants did not use prescription rosacea treatments prior to pregnancy, and 89.6% did not use them during pregnancy.

IN PRACTICE:

“Rosacea, like acne, lacks a predictable group effect, and instead, each individual may have a different response to the physiologic changes of pregnancy,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

Genevieve Benedetti, MD, MPP, of the Department of Dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, led the research, published as a research letter in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size, single-center design, and overall prevalence of mild disease limit the ability to detect change.

DISCLOSURES:

The researchers reported having no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among women diagnosed with rosacea, the impact of pregnancy on the disease is unpredictable.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a telephone survey of 39 women with a diagnosis of rosacea in the electronic medical records prior to the onset of pregnancy who had been admitted to Oregon Health & Science University for labor and delivery from June 27, 2015, to June 27, 2020.

- Patient global assessment of clear (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) rosacea was rated across five timepoints: 1-3 months preconception; first, second, and third trimesters; and 6 weeks postpartum.

TAKEAWAY:

- The mean age of the survey participants was 35.5 years, the mean gestational age at delivery was 39.4 weeks, and most had singleton pregnancies.

- All but one study participant (97.4%) reported symptoms of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, while 26 (67%) reported symptoms of papulopustular rosacea.

- Nearly half of the participants (19, 48.7%) said their rosacea worsened during pregnancy, 13 (33.3%) reported no change in rosacea severity during pregnancy, and 7 (17.9%) reported that their rosacea improved during pregnancy.

- Before conceiving, the mean rosacea severity score among participants was mild (1.10; 95% CI, 0.92-1.29) and did not change significantly over time, a reflection of individual variations. In addition, 83.3% of participants did not use prescription rosacea treatments prior to pregnancy, and 89.6% did not use them during pregnancy.

IN PRACTICE:

“Rosacea, like acne, lacks a predictable group effect, and instead, each individual may have a different response to the physiologic changes of pregnancy,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

Genevieve Benedetti, MD, MPP, of the Department of Dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, led the research, published as a research letter in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size, single-center design, and overall prevalence of mild disease limit the ability to detect change.

DISCLOSURES:

The researchers reported having no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among women diagnosed with rosacea, the impact of pregnancy on the disease is unpredictable.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a telephone survey of 39 women with a diagnosis of rosacea in the electronic medical records prior to the onset of pregnancy who had been admitted to Oregon Health & Science University for labor and delivery from June 27, 2015, to June 27, 2020.

- Patient global assessment of clear (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) rosacea was rated across five timepoints: 1-3 months preconception; first, second, and third trimesters; and 6 weeks postpartum.

TAKEAWAY:

- The mean age of the survey participants was 35.5 years, the mean gestational age at delivery was 39.4 weeks, and most had singleton pregnancies.

- All but one study participant (97.4%) reported symptoms of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, while 26 (67%) reported symptoms of papulopustular rosacea.

- Nearly half of the participants (19, 48.7%) said their rosacea worsened during pregnancy, 13 (33.3%) reported no change in rosacea severity during pregnancy, and 7 (17.9%) reported that their rosacea improved during pregnancy.

- Before conceiving, the mean rosacea severity score among participants was mild (1.10; 95% CI, 0.92-1.29) and did not change significantly over time, a reflection of individual variations. In addition, 83.3% of participants did not use prescription rosacea treatments prior to pregnancy, and 89.6% did not use them during pregnancy.

IN PRACTICE:

“Rosacea, like acne, lacks a predictable group effect, and instead, each individual may have a different response to the physiologic changes of pregnancy,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

Genevieve Benedetti, MD, MPP, of the Department of Dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, led the research, published as a research letter in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size, single-center design, and overall prevalence of mild disease limit the ability to detect change.

DISCLOSURES:

The researchers reported having no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

US Dermatologic Drug Approvals Rose Between 2012 and 2022

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Only five new drugs for diseases treated mostly by dermatologists were approved by the FDA between 1999 and 2009.

- In a cross-sectional analysis to characterize the frequency and degree of innovation of dermatologic drugs approved more recently, researchers identified new and supplemental dermatologic drugs approved between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022, from FDA lists, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CenterWatch, and peer-reviewed articles.

- They used five proxy measures to estimate each drug’s degree of innovation: FDA designation (first in class, advance in class, or addition to class), independent clinical usefulness ratings, and benefit ratings by health technology assessment organizations.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study authors identified 52 new drug applications and 26 supplemental new indications approved by the FDA for dermatologic indications between 2012 and 2022.

- Of the 52 new drugs, the researchers categorized 11 (21%) as first in class and 13 (25%) as first in indication.

- An analysis of benefit ratings available for 38 of the drugs showed that 15 (39%) were rated as being clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

- Of the 10 supplemental new indications with ratings by any organization, 3 (30%) were rated as clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

While innovative drug development in dermatology may have increased, “these findings also highlight opportunities to develop more truly innovative dermatologic agents, particularly for diseases with unmet therapeutic need,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

First author Samir Kamat, MD, of the Medical Education Department at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and corresponding author Ravi Gupta, MD, MSHP, of the Internal Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, led the research. The study was published online as a research letter on December 20, 2023, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

They include the use of individual indications to assess clinical usefulness and benefit ratings. Many drugs, particularly supplemental indications, lacked such ratings. Reformulations of already marketed drugs or indications were not included.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kamat and Dr. Gupta had no relevant disclosures. Three coauthors reported having received financial support outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Only five new drugs for diseases treated mostly by dermatologists were approved by the FDA between 1999 and 2009.

- In a cross-sectional analysis to characterize the frequency and degree of innovation of dermatologic drugs approved more recently, researchers identified new and supplemental dermatologic drugs approved between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022, from FDA lists, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CenterWatch, and peer-reviewed articles.

- They used five proxy measures to estimate each drug’s degree of innovation: FDA designation (first in class, advance in class, or addition to class), independent clinical usefulness ratings, and benefit ratings by health technology assessment organizations.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study authors identified 52 new drug applications and 26 supplemental new indications approved by the FDA for dermatologic indications between 2012 and 2022.

- Of the 52 new drugs, the researchers categorized 11 (21%) as first in class and 13 (25%) as first in indication.

- An analysis of benefit ratings available for 38 of the drugs showed that 15 (39%) were rated as being clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

- Of the 10 supplemental new indications with ratings by any organization, 3 (30%) were rated as clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

While innovative drug development in dermatology may have increased, “these findings also highlight opportunities to develop more truly innovative dermatologic agents, particularly for diseases with unmet therapeutic need,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

First author Samir Kamat, MD, of the Medical Education Department at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and corresponding author Ravi Gupta, MD, MSHP, of the Internal Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, led the research. The study was published online as a research letter on December 20, 2023, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

They include the use of individual indications to assess clinical usefulness and benefit ratings. Many drugs, particularly supplemental indications, lacked such ratings. Reformulations of already marketed drugs or indications were not included.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kamat and Dr. Gupta had no relevant disclosures. Three coauthors reported having received financial support outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Only five new drugs for diseases treated mostly by dermatologists were approved by the FDA between 1999 and 2009.

- In a cross-sectional analysis to characterize the frequency and degree of innovation of dermatologic drugs approved more recently, researchers identified new and supplemental dermatologic drugs approved between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022, from FDA lists, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CenterWatch, and peer-reviewed articles.

- They used five proxy measures to estimate each drug’s degree of innovation: FDA designation (first in class, advance in class, or addition to class), independent clinical usefulness ratings, and benefit ratings by health technology assessment organizations.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study authors identified 52 new drug applications and 26 supplemental new indications approved by the FDA for dermatologic indications between 2012 and 2022.

- Of the 52 new drugs, the researchers categorized 11 (21%) as first in class and 13 (25%) as first in indication.

- An analysis of benefit ratings available for 38 of the drugs showed that 15 (39%) were rated as being clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

- Of the 10 supplemental new indications with ratings by any organization, 3 (30%) were rated as clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

While innovative drug development in dermatology may have increased, “these findings also highlight opportunities to develop more truly innovative dermatologic agents, particularly for diseases with unmet therapeutic need,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

First author Samir Kamat, MD, of the Medical Education Department at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and corresponding author Ravi Gupta, MD, MSHP, of the Internal Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, led the research. The study was published online as a research letter on December 20, 2023, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

They include the use of individual indications to assess clinical usefulness and benefit ratings. Many drugs, particularly supplemental indications, lacked such ratings. Reformulations of already marketed drugs or indications were not included.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kamat and Dr. Gupta had no relevant disclosures. Three coauthors reported having received financial support outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Topical ivermectin study sheds light on dysbiosis in rosacea

, according to a report presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2023 Congress.

“This is the first hint that the host’s cutaneous microbiome plays a secondary role in the immunopathogenesis of rosacea,” said Bernard Homey, MD, director of the department of dermatology at University Hospital Düsseldorf in Germany.

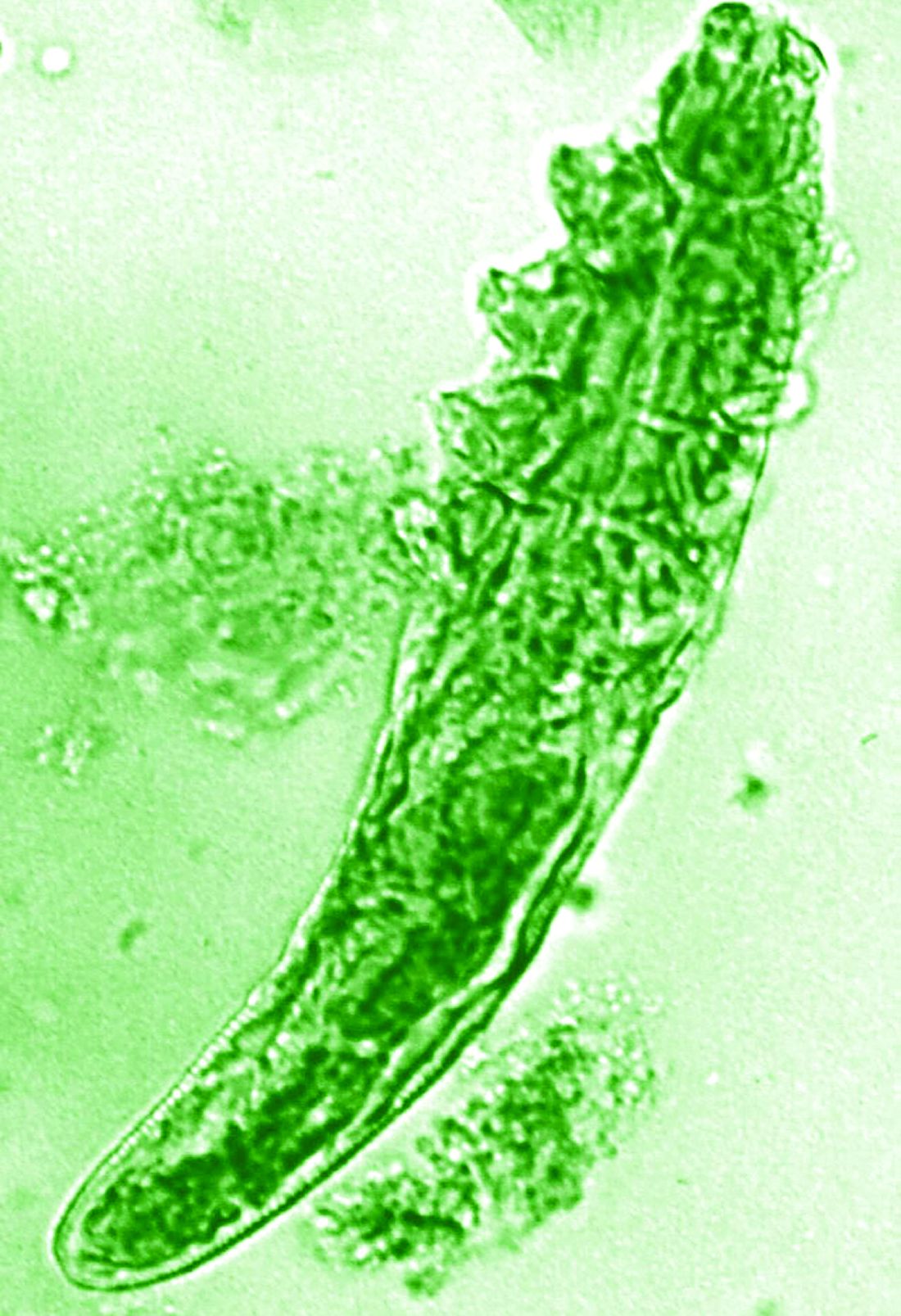

“In rosacea, we are well aware of trigger factors such as stress, UV light, heat, cold, food, and alcohol,” he said. “We are also well aware that there is an increase in Demodex mites in the pilosebaceous unit.”

Research over the past decade has also started to look at the potential role of the skin microbiome in the disease process, but answers have remained “largely elusive,” Dr. Homey said.

Ivermectin helps, but how?

Ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2014 for the treatment of the inflammatory lesions that are characteristic of rosacea, but its mechanism of action is not clear.

Dr. Homey presented the results of a study of 61 patients designed to look at how ivermectin might be working in the treatment of people with rosacea and investigate if there was any relation to the skin microbiome and transcriptome of patients.

The trial included 41 individuals with papulopustular rosacea and 20 individuals who did not have rosacea. For all patients, surface skin biopsies were performed twice 30 days apart using cyanoacrylate glue; patients with rosacea were treated with topical ivermectin 1% between biopsies. Skin samples obtained at day 0 and day 30 were examined under the microscope, and Demodex counts (mites/cm2) of skin and RNA sequencing of the cutaneous microbiome were undertaken.

The mean age of the patients with rosacea was 54.9 years, and the mean Demodex counts before and after treatment were a respective 7.2 cm2 and 0.9 cm2.

Using the Investigator’s General Assessment to assess the severity of rosacea, Homey reported that 43.9% of patients with rosacea had a decrease in scores at day 30, indicating improvement.

In addition, topical ivermectin resulted in a marked or total decrease in Demodex mite density for 87.5% of patients (n = 24) who were identified as having the mites.

Skin microbiome changes seen

As a form of quality control, skin microbiome changes among the patients were compared with control patients using 16S rRNA sequencing.

“The taxa we find within the cutaneous niche of inflammatory lesions of rosacea patients are significantly different from healthy volunteers,” Dr. Homey said.

Cutibacterium species are predominant in healthy control persons but are not present when there is inflammation in patients with rosacea. Instead, staphylococcus species “take over the niche, similar to atopic dermatitis,” he noted.

Looking at how treatment with ivermectin influences the organisms, the decrease in C. acnes seen in patients with rosacea persisted despite treatment, and the abundance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, and S. capitis increased further. This suggests a possible protective or homeostatic role of C. acnes but a pathogenic role for staphylococci, explained Dr. Homey.

“Surprisingly, although inflammatory lesions decrease, patients get better, the cutaneous microbiome does not revert to homeostatic conditions during topical ivermectin treatment,” he observed.

There is, of course, variability among individuals.

Dr. Homey also reported that Snodgrassella alvi – a microorganism believed to reside in the gut of Demodex folliculorum mites – was found in the skin microbiome of patients with rosacea before but not after ivermectin treatment. This may mean that this microorganism could be partially triggering inflammation in rosacea patients.

Looking at the transcriptome of patients, Dr. Homey said that there was downregulation of distinct genes that might make for more favorable conditions for Demodex mites.

Moreover, insufficient upregulation of interleukin-17 pathways might be working together with barrier defects in the skin and metabolic changes to “pave the way” for colonization by S. epidermidis.

Pulling it together

Dr. Homey and associates conclude in their abstract that the findings “support that rosacea lesions are associated with dysbiosis.”

Although treatment with ivermectin did not normalize the skin’s microbiome, it was associated with a decrease in Demodex mite density and the reduction of microbes associated with Demodex.

Margarida Gonçalo, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, who cochaired the late-breaking news session where the data were presented, asked whether healthy and affected skin in patients with rosacea had been compared, rather than comparing the skin of rosacea lesions with healthy control samples.

“No, we did not this, as this is methodologically a little bit more difficult,” Dr. Homey responded.

Also cochairing the session was Michel Gilliet, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the University Hospital CHUV in Lausanne, Switzerland. He commented that these “data suggest that there’s an intimate link between Demodex and the skin microbiota and dysbiosis in in rosacea.”

Dr. Gilliet added: “You have a whole dysbiosis going on in rosacea, which is probably only dependent on these bacteria.”

It would be “very interesting,” as a “proof-of-concept” study, to look at whether depleting Demodex would also delete S. alvi, he suggested.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Homey has acted as a consultant, speaker or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies including Galderma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a report presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2023 Congress.

“This is the first hint that the host’s cutaneous microbiome plays a secondary role in the immunopathogenesis of rosacea,” said Bernard Homey, MD, director of the department of dermatology at University Hospital Düsseldorf in Germany.

“In rosacea, we are well aware of trigger factors such as stress, UV light, heat, cold, food, and alcohol,” he said. “We are also well aware that there is an increase in Demodex mites in the pilosebaceous unit.”

Research over the past decade has also started to look at the potential role of the skin microbiome in the disease process, but answers have remained “largely elusive,” Dr. Homey said.

Ivermectin helps, but how?

Ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2014 for the treatment of the inflammatory lesions that are characteristic of rosacea, but its mechanism of action is not clear.

Dr. Homey presented the results of a study of 61 patients designed to look at how ivermectin might be working in the treatment of people with rosacea and investigate if there was any relation to the skin microbiome and transcriptome of patients.

The trial included 41 individuals with papulopustular rosacea and 20 individuals who did not have rosacea. For all patients, surface skin biopsies were performed twice 30 days apart using cyanoacrylate glue; patients with rosacea were treated with topical ivermectin 1% between biopsies. Skin samples obtained at day 0 and day 30 were examined under the microscope, and Demodex counts (mites/cm2) of skin and RNA sequencing of the cutaneous microbiome were undertaken.

The mean age of the patients with rosacea was 54.9 years, and the mean Demodex counts before and after treatment were a respective 7.2 cm2 and 0.9 cm2.

Using the Investigator’s General Assessment to assess the severity of rosacea, Homey reported that 43.9% of patients with rosacea had a decrease in scores at day 30, indicating improvement.

In addition, topical ivermectin resulted in a marked or total decrease in Demodex mite density for 87.5% of patients (n = 24) who were identified as having the mites.

Skin microbiome changes seen

As a form of quality control, skin microbiome changes among the patients were compared with control patients using 16S rRNA sequencing.

“The taxa we find within the cutaneous niche of inflammatory lesions of rosacea patients are significantly different from healthy volunteers,” Dr. Homey said.

Cutibacterium species are predominant in healthy control persons but are not present when there is inflammation in patients with rosacea. Instead, staphylococcus species “take over the niche, similar to atopic dermatitis,” he noted.

Looking at how treatment with ivermectin influences the organisms, the decrease in C. acnes seen in patients with rosacea persisted despite treatment, and the abundance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, and S. capitis increased further. This suggests a possible protective or homeostatic role of C. acnes but a pathogenic role for staphylococci, explained Dr. Homey.

“Surprisingly, although inflammatory lesions decrease, patients get better, the cutaneous microbiome does not revert to homeostatic conditions during topical ivermectin treatment,” he observed.

There is, of course, variability among individuals.

Dr. Homey also reported that Snodgrassella alvi – a microorganism believed to reside in the gut of Demodex folliculorum mites – was found in the skin microbiome of patients with rosacea before but not after ivermectin treatment. This may mean that this microorganism could be partially triggering inflammation in rosacea patients.

Looking at the transcriptome of patients, Dr. Homey said that there was downregulation of distinct genes that might make for more favorable conditions for Demodex mites.

Moreover, insufficient upregulation of interleukin-17 pathways might be working together with barrier defects in the skin and metabolic changes to “pave the way” for colonization by S. epidermidis.

Pulling it together

Dr. Homey and associates conclude in their abstract that the findings “support that rosacea lesions are associated with dysbiosis.”

Although treatment with ivermectin did not normalize the skin’s microbiome, it was associated with a decrease in Demodex mite density and the reduction of microbes associated with Demodex.

Margarida Gonçalo, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, who cochaired the late-breaking news session where the data were presented, asked whether healthy and affected skin in patients with rosacea had been compared, rather than comparing the skin of rosacea lesions with healthy control samples.

“No, we did not this, as this is methodologically a little bit more difficult,” Dr. Homey responded.

Also cochairing the session was Michel Gilliet, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the University Hospital CHUV in Lausanne, Switzerland. He commented that these “data suggest that there’s an intimate link between Demodex and the skin microbiota and dysbiosis in in rosacea.”

Dr. Gilliet added: “You have a whole dysbiosis going on in rosacea, which is probably only dependent on these bacteria.”

It would be “very interesting,” as a “proof-of-concept” study, to look at whether depleting Demodex would also delete S. alvi, he suggested.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Homey has acted as a consultant, speaker or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies including Galderma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a report presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2023 Congress.

“This is the first hint that the host’s cutaneous microbiome plays a secondary role in the immunopathogenesis of rosacea,” said Bernard Homey, MD, director of the department of dermatology at University Hospital Düsseldorf in Germany.

“In rosacea, we are well aware of trigger factors such as stress, UV light, heat, cold, food, and alcohol,” he said. “We are also well aware that there is an increase in Demodex mites in the pilosebaceous unit.”

Research over the past decade has also started to look at the potential role of the skin microbiome in the disease process, but answers have remained “largely elusive,” Dr. Homey said.

Ivermectin helps, but how?

Ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2014 for the treatment of the inflammatory lesions that are characteristic of rosacea, but its mechanism of action is not clear.

Dr. Homey presented the results of a study of 61 patients designed to look at how ivermectin might be working in the treatment of people with rosacea and investigate if there was any relation to the skin microbiome and transcriptome of patients.

The trial included 41 individuals with papulopustular rosacea and 20 individuals who did not have rosacea. For all patients, surface skin biopsies were performed twice 30 days apart using cyanoacrylate glue; patients with rosacea were treated with topical ivermectin 1% between biopsies. Skin samples obtained at day 0 and day 30 were examined under the microscope, and Demodex counts (mites/cm2) of skin and RNA sequencing of the cutaneous microbiome were undertaken.

The mean age of the patients with rosacea was 54.9 years, and the mean Demodex counts before and after treatment were a respective 7.2 cm2 and 0.9 cm2.

Using the Investigator’s General Assessment to assess the severity of rosacea, Homey reported that 43.9% of patients with rosacea had a decrease in scores at day 30, indicating improvement.

In addition, topical ivermectin resulted in a marked or total decrease in Demodex mite density for 87.5% of patients (n = 24) who were identified as having the mites.

Skin microbiome changes seen

As a form of quality control, skin microbiome changes among the patients were compared with control patients using 16S rRNA sequencing.

“The taxa we find within the cutaneous niche of inflammatory lesions of rosacea patients are significantly different from healthy volunteers,” Dr. Homey said.

Cutibacterium species are predominant in healthy control persons but are not present when there is inflammation in patients with rosacea. Instead, staphylococcus species “take over the niche, similar to atopic dermatitis,” he noted.

Looking at how treatment with ivermectin influences the organisms, the decrease in C. acnes seen in patients with rosacea persisted despite treatment, and the abundance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, and S. capitis increased further. This suggests a possible protective or homeostatic role of C. acnes but a pathogenic role for staphylococci, explained Dr. Homey.

“Surprisingly, although inflammatory lesions decrease, patients get better, the cutaneous microbiome does not revert to homeostatic conditions during topical ivermectin treatment,” he observed.

There is, of course, variability among individuals.

Dr. Homey also reported that Snodgrassella alvi – a microorganism believed to reside in the gut of Demodex folliculorum mites – was found in the skin microbiome of patients with rosacea before but not after ivermectin treatment. This may mean that this microorganism could be partially triggering inflammation in rosacea patients.

Looking at the transcriptome of patients, Dr. Homey said that there was downregulation of distinct genes that might make for more favorable conditions for Demodex mites.

Moreover, insufficient upregulation of interleukin-17 pathways might be working together with barrier defects in the skin and metabolic changes to “pave the way” for colonization by S. epidermidis.

Pulling it together

Dr. Homey and associates conclude in their abstract that the findings “support that rosacea lesions are associated with dysbiosis.”

Although treatment with ivermectin did not normalize the skin’s microbiome, it was associated with a decrease in Demodex mite density and the reduction of microbes associated with Demodex.

Margarida Gonçalo, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, who cochaired the late-breaking news session where the data were presented, asked whether healthy and affected skin in patients with rosacea had been compared, rather than comparing the skin of rosacea lesions with healthy control samples.

“No, we did not this, as this is methodologically a little bit more difficult,” Dr. Homey responded.

Also cochairing the session was Michel Gilliet, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the University Hospital CHUV in Lausanne, Switzerland. He commented that these “data suggest that there’s an intimate link between Demodex and the skin microbiota and dysbiosis in in rosacea.”

Dr. Gilliet added: “You have a whole dysbiosis going on in rosacea, which is probably only dependent on these bacteria.”

It would be “very interesting,” as a “proof-of-concept” study, to look at whether depleting Demodex would also delete S. alvi, he suggested.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Homey has acted as a consultant, speaker or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies including Galderma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EADV 2023

The Growing Pains of Changing Times for Acne and Rosacea Pathophysiology: Where Will It All End Up?

It is interesting to observe the changes in dermatology that have occurred over the last 1 to 2 decades, especially as major advances in basic science research techniques have rapidly expanded our current understanding of the pathophysiology of many disease states—psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen planus.1 Although acne vulgaris (AV) and rosacea do not make front-page news quite as often as some of these other aforementioned disease states in the pathophysiology arena, advances still have been made in understanding the pathophysiology, albeit slower and often less popularized in dermatology publications and other forms of media.2-4

If one looks at our fundamental understanding of AV, most of the discussion over multiple decades has been driven by new treatments and in some cases new formulations and packaging differences with topical agents. Although we understood that adrenarche, a subsequent increase in androgen synthesis, and the ensuing sebocyte development with formation of sebum were prerequisites for the development of AV, the absence of therapeutic options to address these vital components of AV—especially US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies—resulted in limited discussion about this specific area.5 Rather, the discussion was dominated by the notable role of Propionibacterium acnes (now called Cutibacterium acnes) in AV pathophysiology, as we had therapies such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics that improved AV in direct correlation with reductions in P acnes.6 This was soon coupled with an advanced understanding of how to reduce follicular hyperkeratinization with the development of topical tretinoin, followed by 3 other topical retinoids over time—adapalene, tazarotene, and trifarotene. Over subsequent years, slowly emerging basic science developments and collective data reviews added to our understanding of AV and how different therapies appear to work, including the role of toll-like receptors, anti-inflammatory properties of tetracyclines, and inflammasomes.7-9 Without a doubt, the availability of oral isotretinoin revolutionized AV therapy, especially in patients with severe refractory disease, with advanced formulations allowing for optimization of sustained remission without the need for high dietary fat intake.10-12

Progress in the pathophysiology of rosacea has been slower to develop, with the first true discussion of specific clinical presentations published after the new millennium.13 This was followed by more advanced basic science and clinical research, which led to an improved ability to understand modes of action of various therapies and to correlate treatment selection with specific visible manifestations of rosacea, including incorporation of physical devices.14-16 A newer perspective on evaluation and management of rosacea moved away from the “buckets” of rosacea subtypes to phenotypes observed at the time of clinical presentation.17,18

I could elaborate on research advancements with both diseases, but the bottom line is that information, developments, and current perspectives change over time. Keeping up is a challenge for all who study and practice dermatology. It is human nature to revert to what we already believe and do, which sometimes remains valid and other times is quite outdated and truly replaced by more optimal approaches. With AV and rosacea, progress is much slower in availability of newer agents. With AV, new agents have included topical dapsone, oral sarecycline, and topical clascoterone, with the latter being the first FDA-approved topical agent to mitigate the effects of androgens and sebum in both males and females. For rosacea, the 2 most recent FDA-approved therapies are minocycline foam and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide. All of these therapies are proven to be effective for the modes of action and skin manifestations they specifically manage. Over the upcoming year, we are hoping to see the first triple-combination topical product come to market for AV, which will prompt our minds to consider if and how 3 established agents can work together to further augment treatment efficacy with favorable tolerability and safety.

Where will all of this end up? It is hard to say. We still have several other areas to tackle with both disease states, including establishing a well-substantiated understanding of the pathophysiologic role of the microbiome, sorting out the role of antibiotic use due to concerns about bacterial resistance, integration of FDA-approved physical devices in AV, and data on both diet and optimized skin care, to name a few.19-21

There is a lot on the plate to accomplish and digest. I have remained very involved in this subject matter for almost 3 decades and am still feeling the growing pains. Fortunately, the satisfaction of being part of a process so important to the lives of millions of patients makes this worth every moment. Stay tuned—more valuable information is to come.

- Wu J, Fang Z, Liu T, et al. Maximizing the utility of transcriptomics data in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761890.

- Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, et al. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1579.

- Mias C, Mengeaud V, Bessou-Touya S, et al. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;(37 suppl 2):3-11.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16537.1

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1953. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15659.1

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211:193-198.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, et al. Nonantibiotic properties of tetracyclines in rosacea and their clinical implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-21.

- Zhu W, Wang HL, Bu XL, et al. A narrative review of research progress on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in acne vulgaris. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:645.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2 suppl):S3-S21.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:762-767.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Seagal J, et al. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:13-18.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Tanghetti E, Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 4: a status report on physical modalities and devices. Cutis. 2014;93:71-76.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Tanghetti E, et al. An evaluation of potential correlations between pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management of rosacea. Cutis. 2013;91(3 suppl):1-8.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1269-1276.

- Xu H, Li H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:335-344.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Kayiran MA, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

It is interesting to observe the changes in dermatology that have occurred over the last 1 to 2 decades, especially as major advances in basic science research techniques have rapidly expanded our current understanding of the pathophysiology of many disease states—psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen planus.1 Although acne vulgaris (AV) and rosacea do not make front-page news quite as often as some of these other aforementioned disease states in the pathophysiology arena, advances still have been made in understanding the pathophysiology, albeit slower and often less popularized in dermatology publications and other forms of media.2-4

If one looks at our fundamental understanding of AV, most of the discussion over multiple decades has been driven by new treatments and in some cases new formulations and packaging differences with topical agents. Although we understood that adrenarche, a subsequent increase in androgen synthesis, and the ensuing sebocyte development with formation of sebum were prerequisites for the development of AV, the absence of therapeutic options to address these vital components of AV—especially US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies—resulted in limited discussion about this specific area.5 Rather, the discussion was dominated by the notable role of Propionibacterium acnes (now called Cutibacterium acnes) in AV pathophysiology, as we had therapies such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics that improved AV in direct correlation with reductions in P acnes.6 This was soon coupled with an advanced understanding of how to reduce follicular hyperkeratinization with the development of topical tretinoin, followed by 3 other topical retinoids over time—adapalene, tazarotene, and trifarotene. Over subsequent years, slowly emerging basic science developments and collective data reviews added to our understanding of AV and how different therapies appear to work, including the role of toll-like receptors, anti-inflammatory properties of tetracyclines, and inflammasomes.7-9 Without a doubt, the availability of oral isotretinoin revolutionized AV therapy, especially in patients with severe refractory disease, with advanced formulations allowing for optimization of sustained remission without the need for high dietary fat intake.10-12

Progress in the pathophysiology of rosacea has been slower to develop, with the first true discussion of specific clinical presentations published after the new millennium.13 This was followed by more advanced basic science and clinical research, which led to an improved ability to understand modes of action of various therapies and to correlate treatment selection with specific visible manifestations of rosacea, including incorporation of physical devices.14-16 A newer perspective on evaluation and management of rosacea moved away from the “buckets” of rosacea subtypes to phenotypes observed at the time of clinical presentation.17,18

I could elaborate on research advancements with both diseases, but the bottom line is that information, developments, and current perspectives change over time. Keeping up is a challenge for all who study and practice dermatology. It is human nature to revert to what we already believe and do, which sometimes remains valid and other times is quite outdated and truly replaced by more optimal approaches. With AV and rosacea, progress is much slower in availability of newer agents. With AV, new agents have included topical dapsone, oral sarecycline, and topical clascoterone, with the latter being the first FDA-approved topical agent to mitigate the effects of androgens and sebum in both males and females. For rosacea, the 2 most recent FDA-approved therapies are minocycline foam and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide. All of these therapies are proven to be effective for the modes of action and skin manifestations they specifically manage. Over the upcoming year, we are hoping to see the first triple-combination topical product come to market for AV, which will prompt our minds to consider if and how 3 established agents can work together to further augment treatment efficacy with favorable tolerability and safety.

Where will all of this end up? It is hard to say. We still have several other areas to tackle with both disease states, including establishing a well-substantiated understanding of the pathophysiologic role of the microbiome, sorting out the role of antibiotic use due to concerns about bacterial resistance, integration of FDA-approved physical devices in AV, and data on both diet and optimized skin care, to name a few.19-21

There is a lot on the plate to accomplish and digest. I have remained very involved in this subject matter for almost 3 decades and am still feeling the growing pains. Fortunately, the satisfaction of being part of a process so important to the lives of millions of patients makes this worth every moment. Stay tuned—more valuable information is to come.

It is interesting to observe the changes in dermatology that have occurred over the last 1 to 2 decades, especially as major advances in basic science research techniques have rapidly expanded our current understanding of the pathophysiology of many disease states—psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen planus.1 Although acne vulgaris (AV) and rosacea do not make front-page news quite as often as some of these other aforementioned disease states in the pathophysiology arena, advances still have been made in understanding the pathophysiology, albeit slower and often less popularized in dermatology publications and other forms of media.2-4

If one looks at our fundamental understanding of AV, most of the discussion over multiple decades has been driven by new treatments and in some cases new formulations and packaging differences with topical agents. Although we understood that adrenarche, a subsequent increase in androgen synthesis, and the ensuing sebocyte development with formation of sebum were prerequisites for the development of AV, the absence of therapeutic options to address these vital components of AV—especially US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies—resulted in limited discussion about this specific area.5 Rather, the discussion was dominated by the notable role of Propionibacterium acnes (now called Cutibacterium acnes) in AV pathophysiology, as we had therapies such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics that improved AV in direct correlation with reductions in P acnes.6 This was soon coupled with an advanced understanding of how to reduce follicular hyperkeratinization with the development of topical tretinoin, followed by 3 other topical retinoids over time—adapalene, tazarotene, and trifarotene. Over subsequent years, slowly emerging basic science developments and collective data reviews added to our understanding of AV and how different therapies appear to work, including the role of toll-like receptors, anti-inflammatory properties of tetracyclines, and inflammasomes.7-9 Without a doubt, the availability of oral isotretinoin revolutionized AV therapy, especially in patients with severe refractory disease, with advanced formulations allowing for optimization of sustained remission without the need for high dietary fat intake.10-12

Progress in the pathophysiology of rosacea has been slower to develop, with the first true discussion of specific clinical presentations published after the new millennium.13 This was followed by more advanced basic science and clinical research, which led to an improved ability to understand modes of action of various therapies and to correlate treatment selection with specific visible manifestations of rosacea, including incorporation of physical devices.14-16 A newer perspective on evaluation and management of rosacea moved away from the “buckets” of rosacea subtypes to phenotypes observed at the time of clinical presentation.17,18

I could elaborate on research advancements with both diseases, but the bottom line is that information, developments, and current perspectives change over time. Keeping up is a challenge for all who study and practice dermatology. It is human nature to revert to what we already believe and do, which sometimes remains valid and other times is quite outdated and truly replaced by more optimal approaches. With AV and rosacea, progress is much slower in availability of newer agents. With AV, new agents have included topical dapsone, oral sarecycline, and topical clascoterone, with the latter being the first FDA-approved topical agent to mitigate the effects of androgens and sebum in both males and females. For rosacea, the 2 most recent FDA-approved therapies are minocycline foam and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide. All of these therapies are proven to be effective for the modes of action and skin manifestations they specifically manage. Over the upcoming year, we are hoping to see the first triple-combination topical product come to market for AV, which will prompt our minds to consider if and how 3 established agents can work together to further augment treatment efficacy with favorable tolerability and safety.

Where will all of this end up? It is hard to say. We still have several other areas to tackle with both disease states, including establishing a well-substantiated understanding of the pathophysiologic role of the microbiome, sorting out the role of antibiotic use due to concerns about bacterial resistance, integration of FDA-approved physical devices in AV, and data on both diet and optimized skin care, to name a few.19-21

There is a lot on the plate to accomplish and digest. I have remained very involved in this subject matter for almost 3 decades and am still feeling the growing pains. Fortunately, the satisfaction of being part of a process so important to the lives of millions of patients makes this worth every moment. Stay tuned—more valuable information is to come.

- Wu J, Fang Z, Liu T, et al. Maximizing the utility of transcriptomics data in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761890.

- Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, et al. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1579.

- Mias C, Mengeaud V, Bessou-Touya S, et al. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;(37 suppl 2):3-11.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16537.1

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1953. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15659.1

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211:193-198.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, et al. Nonantibiotic properties of tetracyclines in rosacea and their clinical implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-21.

- Zhu W, Wang HL, Bu XL, et al. A narrative review of research progress on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in acne vulgaris. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:645.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2 suppl):S3-S21.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:762-767.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Seagal J, et al. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:13-18.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Tanghetti E, Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 4: a status report on physical modalities and devices. Cutis. 2014;93:71-76.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Tanghetti E, et al. An evaluation of potential correlations between pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management of rosacea. Cutis. 2013;91(3 suppl):1-8.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1269-1276.

- Xu H, Li H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:335-344.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Kayiran MA, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

- Wu J, Fang Z, Liu T, et al. Maximizing the utility of transcriptomics data in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761890.

- Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, et al. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1579.

- Mias C, Mengeaud V, Bessou-Touya S, et al. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;(37 suppl 2):3-11.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16537.1

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1953. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15659.1

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211:193-198.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, et al. Nonantibiotic properties of tetracyclines in rosacea and their clinical implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-21.

- Zhu W, Wang HL, Bu XL, et al. A narrative review of research progress on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in acne vulgaris. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:645.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2 suppl):S3-S21.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:762-767.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Seagal J, et al. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:13-18.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Tanghetti E, Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 4: a status report on physical modalities and devices. Cutis. 2014;93:71-76.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Tanghetti E, et al. An evaluation of potential correlations between pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management of rosacea. Cutis. 2013;91(3 suppl):1-8.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1269-1276.

- Xu H, Li H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:335-344.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Kayiran MA, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

Treating rosacea: Combination therapy, benzoyl peroxide, and the ‘STOP’ mnemonic

HONOLULU – More often than not, patients with rosacea require a combination of treatments to optimize the management of the disease, according to Julie C. Harper, MD.

“We’ve been more comfortable with the idea of combination therapy for acne than we have been for rosacea,” Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If patients are doing great on one treatment, then don’t change it. But if there’s room for improvement, think about combinations.”

Treatment options for papules and pustules include ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, modified release doxycycline, minocycline foam, and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide, 5%. Options for persistent background erythema include brimonidine and oxymetazoline, as well as device-based treatments, which include the pulsed dye laser, the KTP laser, intense pulsed light, and electrosurgery.

Dr. Harper said that she has been especially surprised by the effectiveness of one of these options, microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, 5% (Epsolay), which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea in adults. In two identical, phase 3 randomized clinical trials of patients with inflammatory rosacea lesions, those treated with microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide achieved a 68.8% reduction in inflammatory lesions at 12 weeks (including 42.5% at week 2), compared with 38%-46% of those on the vehicle, according to the April 2022 announcement of the approval from the manufacturers, Sol-Gel Technologies and Galderma.

“A common drug is playing a key role,” Dr. Harper said. “What’s the mechanism of action? I have no idea. I wonder if there may be a bacterial pathogen after all,” possibly Staphylococcus epidermidis, she added. However, she noted, “it does appear that benzoyl peroxide has an impact on Demodex, so maybe that’s the primary way it’s working.”

In her opinion, a key standout from the clinical trial data is the drug’s rapid onset of action, with a 42.5% reduction of lesions at week 2. “What makes this different is that the 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream is wrapped up in a silica shell,” said Dr. Harper, a past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society. “The silica shell kind of acts like a speed bump that slows the release of drug onto the skin. We think that’s what may be giving us this better tolerability.”

In an interview at the meeting, Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of clinical research and division head of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, said that prior to the approval of Epsolay, benzoyl peroxide was never considered a first-line treatment for rosacea. “The problem is, the conventional formulation is irritating to the skin,” said Dr. Stein Gold, who was involved in clinical trials of Epsolay.

“The benzoyl peroxide encapsulated in the silica shell allows for a slow and steady delivery of medication to the skin in a very controlled manner. It is exceptionally good at getting rosacea under control. In the clinical trials, when we looked at the baseline irritation of the skin and followed those patients when they used the benzoyl 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, the irritation improved.”

‘STOP’ mnemonic

When treating her patients with rosacea, Dr. Harper incorporates the mnemonic “STOP” to these patient visits:

S: Identify signs and symptoms of rosacea.

T: Discuss triggers. “We cannot make this disease triggerless, so when you’re talking to your patients, you need to find out what’s triggering their rosacea,” she said.

O: Agree on a treatment outcome. “What is it that’s important to the patient?” she said. “They may tell you, ‘I want to be able to not be so red,’ or ‘I want to get rid of the bumps,’ or ‘I want my eyes to not feel so dry.’ ”

P: Develop a plan that helps achieve that desired outcome with patients.

Dr. Harper disclosed ties with Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, Galderma, EPI, L’Oréal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Vyne.

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed ties with Almirall, Cutera, Dermata, Galderma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

HONOLULU – More often than not, patients with rosacea require a combination of treatments to optimize the management of the disease, according to Julie C. Harper, MD.

“We’ve been more comfortable with the idea of combination therapy for acne than we have been for rosacea,” Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If patients are doing great on one treatment, then don’t change it. But if there’s room for improvement, think about combinations.”

Treatment options for papules and pustules include ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, modified release doxycycline, minocycline foam, and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide, 5%. Options for persistent background erythema include brimonidine and oxymetazoline, as well as device-based treatments, which include the pulsed dye laser, the KTP laser, intense pulsed light, and electrosurgery.

Dr. Harper said that she has been especially surprised by the effectiveness of one of these options, microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, 5% (Epsolay), which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea in adults. In two identical, phase 3 randomized clinical trials of patients with inflammatory rosacea lesions, those treated with microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide achieved a 68.8% reduction in inflammatory lesions at 12 weeks (including 42.5% at week 2), compared with 38%-46% of those on the vehicle, according to the April 2022 announcement of the approval from the manufacturers, Sol-Gel Technologies and Galderma.

“A common drug is playing a key role,” Dr. Harper said. “What’s the mechanism of action? I have no idea. I wonder if there may be a bacterial pathogen after all,” possibly Staphylococcus epidermidis, she added. However, she noted, “it does appear that benzoyl peroxide has an impact on Demodex, so maybe that’s the primary way it’s working.”

In her opinion, a key standout from the clinical trial data is the drug’s rapid onset of action, with a 42.5% reduction of lesions at week 2. “What makes this different is that the 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream is wrapped up in a silica shell,” said Dr. Harper, a past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society. “The silica shell kind of acts like a speed bump that slows the release of drug onto the skin. We think that’s what may be giving us this better tolerability.”

In an interview at the meeting, Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of clinical research and division head of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, said that prior to the approval of Epsolay, benzoyl peroxide was never considered a first-line treatment for rosacea. “The problem is, the conventional formulation is irritating to the skin,” said Dr. Stein Gold, who was involved in clinical trials of Epsolay.

“The benzoyl peroxide encapsulated in the silica shell allows for a slow and steady delivery of medication to the skin in a very controlled manner. It is exceptionally good at getting rosacea under control. In the clinical trials, when we looked at the baseline irritation of the skin and followed those patients when they used the benzoyl 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, the irritation improved.”

‘STOP’ mnemonic

When treating her patients with rosacea, Dr. Harper incorporates the mnemonic “STOP” to these patient visits:

S: Identify signs and symptoms of rosacea.

T: Discuss triggers. “We cannot make this disease triggerless, so when you’re talking to your patients, you need to find out what’s triggering their rosacea,” she said.

O: Agree on a treatment outcome. “What is it that’s important to the patient?” she said. “They may tell you, ‘I want to be able to not be so red,’ or ‘I want to get rid of the bumps,’ or ‘I want my eyes to not feel so dry.’ ”

P: Develop a plan that helps achieve that desired outcome with patients.

Dr. Harper disclosed ties with Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, Galderma, EPI, L’Oréal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Vyne.

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed ties with Almirall, Cutera, Dermata, Galderma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

HONOLULU – More often than not, patients with rosacea require a combination of treatments to optimize the management of the disease, according to Julie C. Harper, MD.

“We’ve been more comfortable with the idea of combination therapy for acne than we have been for rosacea,” Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If patients are doing great on one treatment, then don’t change it. But if there’s room for improvement, think about combinations.”

Treatment options for papules and pustules include ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, modified release doxycycline, minocycline foam, and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide, 5%. Options for persistent background erythema include brimonidine and oxymetazoline, as well as device-based treatments, which include the pulsed dye laser, the KTP laser, intense pulsed light, and electrosurgery.

Dr. Harper said that she has been especially surprised by the effectiveness of one of these options, microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, 5% (Epsolay), which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea in adults. In two identical, phase 3 randomized clinical trials of patients with inflammatory rosacea lesions, those treated with microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide achieved a 68.8% reduction in inflammatory lesions at 12 weeks (including 42.5% at week 2), compared with 38%-46% of those on the vehicle, according to the April 2022 announcement of the approval from the manufacturers, Sol-Gel Technologies and Galderma.

“A common drug is playing a key role,” Dr. Harper said. “What’s the mechanism of action? I have no idea. I wonder if there may be a bacterial pathogen after all,” possibly Staphylococcus epidermidis, she added. However, she noted, “it does appear that benzoyl peroxide has an impact on Demodex, so maybe that’s the primary way it’s working.”

In her opinion, a key standout from the clinical trial data is the drug’s rapid onset of action, with a 42.5% reduction of lesions at week 2. “What makes this different is that the 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream is wrapped up in a silica shell,” said Dr. Harper, a past president of the American Acne and Rosacea Society. “The silica shell kind of acts like a speed bump that slows the release of drug onto the skin. We think that’s what may be giving us this better tolerability.”

In an interview at the meeting, Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of clinical research and division head of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, said that prior to the approval of Epsolay, benzoyl peroxide was never considered a first-line treatment for rosacea. “The problem is, the conventional formulation is irritating to the skin,” said Dr. Stein Gold, who was involved in clinical trials of Epsolay.

“The benzoyl peroxide encapsulated in the silica shell allows for a slow and steady delivery of medication to the skin in a very controlled manner. It is exceptionally good at getting rosacea under control. In the clinical trials, when we looked at the baseline irritation of the skin and followed those patients when they used the benzoyl 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, the irritation improved.”

‘STOP’ mnemonic

When treating her patients with rosacea, Dr. Harper incorporates the mnemonic “STOP” to these patient visits:

S: Identify signs and symptoms of rosacea.

T: Discuss triggers. “We cannot make this disease triggerless, so when you’re talking to your patients, you need to find out what’s triggering their rosacea,” she said.

O: Agree on a treatment outcome. “What is it that’s important to the patient?” she said. “They may tell you, ‘I want to be able to not be so red,’ or ‘I want to get rid of the bumps,’ or ‘I want my eyes to not feel so dry.’ ”

P: Develop a plan that helps achieve that desired outcome with patients.

Dr. Harper disclosed ties with Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, Galderma, EPI, L’Oréal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Vyne.

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed ties with Almirall, Cutera, Dermata, Galderma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

AT THE MEDSCAPE LIVE! HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

NRS grants target rosacea’s underlying mechanisms

Two new , according to an announcement by the NRS.

As part of the NRS research grants program, the organization recently awarded $10,000 to Emanual Maverakis, MD, professor of dermatology, University of California, Davis, and research fellow Samantha Herbert, MSPH. Their project will characterize rosacea pathophysiology using single-cell RNA sequencing. This novel analytical technique provides specific information on the signals expressed by different cell types and will help researchers better understand the role each subtype may play in rosacea, along with how these cells interact with each other, according to the NRS press release. New knowledge in the foregoing areas may fuel development of better therapies, the release added.

The NRS awarded its second new-research grant to Arisa Ortiz, MD, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology and associate professor of dermatology, University of California, San Diego. She was awarded $5,000 to examine whether laser therapy affects the skin microbiome, the complex ecosystem of bacteria and other microorganisms that reside on the skin. Studies have detected significant differences – such as higher levels of Demodex folliculorum and Staphylococcus epidermidis and lower levels of Cutibacterium acnes – in the microbiome of skin with rosacea compared with healthy skin. Dr. Ortiz’s research also will probe how blood vessels, which laser therapy often target, contribute to the rosacea disease process.

The NRS also renewed its support of an ongoing study led by Sezen Karakus, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore. She is studying the role of the ocular-surface microbiome in rosacea pathogenesis. Because ocular rosacea can lead to vision-threatening corneal complications, Dr. Karakus said in the press release, identifying microorganisms present on the ocular surface may spur development of targeted treatment strategies.

A second ongoing study for which the NRS renewed funding is investigating whether certain intracellular signals recently found to be elevated in rosacea lesions may drive skin inflammation, which may be a root cause of rosacea. Emmanuel Contassot, PhD, project leader in the dermatology department at the University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland, is leading the study.

To date, the NRS research grants program has awarded more than $1.6 million to research designed to further elucidate potential causes and other key aspects of rosacea with the goal of advancing treatment, prevention, or potential cure of rosacea.

For interested researchers, the deadline to submit proposals for next year’s grants is June 16, 2023. Forms and instructions are available through the research grants section of the NRS website or by contacting the NRS at 4619 N. Ravenswood Ave., Suite 103, Chicago, IL 60640; 888-662-5874; or [email protected].

Two new , according to an announcement by the NRS.

As part of the NRS research grants program, the organization recently awarded $10,000 to Emanual Maverakis, MD, professor of dermatology, University of California, Davis, and research fellow Samantha Herbert, MSPH. Their project will characterize rosacea pathophysiology using single-cell RNA sequencing. This novel analytical technique provides specific information on the signals expressed by different cell types and will help researchers better understand the role each subtype may play in rosacea, along with how these cells interact with each other, according to the NRS press release. New knowledge in the foregoing areas may fuel development of better therapies, the release added.

The NRS awarded its second new-research grant to Arisa Ortiz, MD, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology and associate professor of dermatology, University of California, San Diego. She was awarded $5,000 to examine whether laser therapy affects the skin microbiome, the complex ecosystem of bacteria and other microorganisms that reside on the skin. Studies have detected significant differences – such as higher levels of Demodex folliculorum and Staphylococcus epidermidis and lower levels of Cutibacterium acnes – in the microbiome of skin with rosacea compared with healthy skin. Dr. Ortiz’s research also will probe how blood vessels, which laser therapy often target, contribute to the rosacea disease process.

The NRS also renewed its support of an ongoing study led by Sezen Karakus, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore. She is studying the role of the ocular-surface microbiome in rosacea pathogenesis. Because ocular rosacea can lead to vision-threatening corneal complications, Dr. Karakus said in the press release, identifying microorganisms present on the ocular surface may spur development of targeted treatment strategies.

A second ongoing study for which the NRS renewed funding is investigating whether certain intracellular signals recently found to be elevated in rosacea lesions may drive skin inflammation, which may be a root cause of rosacea. Emmanuel Contassot, PhD, project leader in the dermatology department at the University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland, is leading the study.

To date, the NRS research grants program has awarded more than $1.6 million to research designed to further elucidate potential causes and other key aspects of rosacea with the goal of advancing treatment, prevention, or potential cure of rosacea.

For interested researchers, the deadline to submit proposals for next year’s grants is June 16, 2023. Forms and instructions are available through the research grants section of the NRS website or by contacting the NRS at 4619 N. Ravenswood Ave., Suite 103, Chicago, IL 60640; 888-662-5874; or [email protected].

Two new , according to an announcement by the NRS.

As part of the NRS research grants program, the organization recently awarded $10,000 to Emanual Maverakis, MD, professor of dermatology, University of California, Davis, and research fellow Samantha Herbert, MSPH. Their project will characterize rosacea pathophysiology using single-cell RNA sequencing. This novel analytical technique provides specific information on the signals expressed by different cell types and will help researchers better understand the role each subtype may play in rosacea, along with how these cells interact with each other, according to the NRS press release. New knowledge in the foregoing areas may fuel development of better therapies, the release added.

The NRS awarded its second new-research grant to Arisa Ortiz, MD, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology and associate professor of dermatology, University of California, San Diego. She was awarded $5,000 to examine whether laser therapy affects the skin microbiome, the complex ecosystem of bacteria and other microorganisms that reside on the skin. Studies have detected significant differences – such as higher levels of Demodex folliculorum and Staphylococcus epidermidis and lower levels of Cutibacterium acnes – in the microbiome of skin with rosacea compared with healthy skin. Dr. Ortiz’s research also will probe how blood vessels, which laser therapy often target, contribute to the rosacea disease process.

The NRS also renewed its support of an ongoing study led by Sezen Karakus, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore. She is studying the role of the ocular-surface microbiome in rosacea pathogenesis. Because ocular rosacea can lead to vision-threatening corneal complications, Dr. Karakus said in the press release, identifying microorganisms present on the ocular surface may spur development of targeted treatment strategies.