User login

3D vs 2D mammography for detecting cancer in dense breasts

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

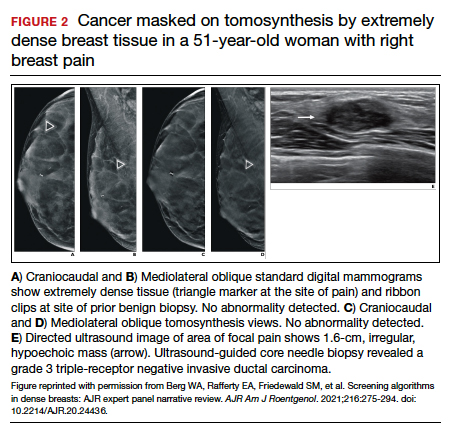

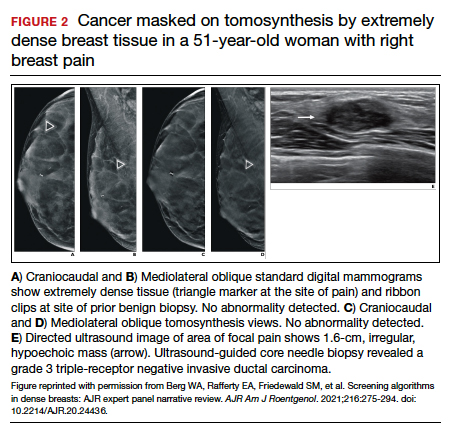

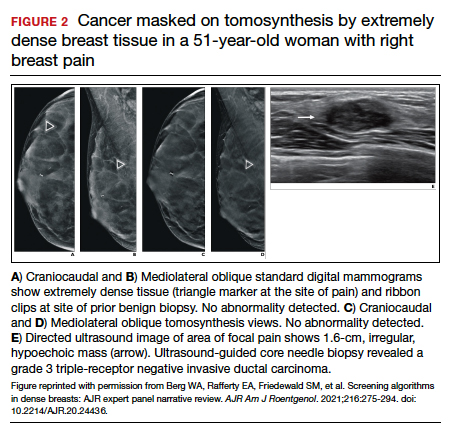

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

In and out surgeries become the norm during pandemic

Urologist Ronney Abaza, MD, a robotic surgery specialist in Dublin, Ohio, and colleagues, reviewed robotic surgeries at their hospital during COVID-19 restrictions on surgery in Ohio between March 17 and June 5, 2020, and compared them with robotic procedures before COVID-19 and after restrictions were lifted. They published their results in Urology.

Since 2016, the hospital has offered the option of same-day discharge (SDD) to all robotic urologic surgery patients, regardless of procedure or patient-specific factors.

Among patients who had surgery during COVID-19 restrictions, 98% (87/89 patients) opted for SDD versus 52% in the group having surgery before the restrictions (P < .00001). After the COVID-19 surgery restrictions were lifted, the higher rate of SDD remained at 98%.

“There were no differences in 30-day complications or readmissions between SDD and overnight patients,” the authors write.

The right patient, the right motivation for successful surgery

Brian Lane, MD, PhD, a urologic oncologist with Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, told this news organization that, for nephrectomies, uptake of same-day discharge will continue to be slow.

“You have to have the right patient, the right patient motivation, and the surgery has to go smoothly,” he said. “If you start sending everyone home the same day, you will certainly see readmissions,” he said.

Dr. Lane is part of the Michigan Urologic Surgery Improvement Collaborative and he said the group recently looked at same-day discharge outcomes after robotic prostatectomies with SDD as compared with 1-2 nights in the hospital.

The work has not yet been published but, “There was a slight signal that there were increased readmissions with same-day discharge vs. 0-1 day,” he said.

A paper on outcomes of same-day discharge in total knee arthroplasty in the Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery found a higher risk of perioperative complications “including component failure, surgical site infection, knee stiffness, and deep vein thrombosis.” Researchers compared outcomes between 4,391 patients who underwent outpatient TKA and 128,951 patients who underwent inpatient TKA.

But for other many surgeries, same-day discharge numbers are increasing without worsening outcomes.

A paper in the Journal of Robotic Surgery found that same-day discharge following robotic-assisted endometrial cancer staging is “safe and feasible.”

Stephen Bradley, MD, MPH, with the Minneapolis Heart Institute in Minneapolis, and colleagues write in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Interventions that they found a large increase in the use of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was not associated with worse 30-day mortality rates or readmission.

In that study, 114,461 patients were discharged the same day they underwent PCI. The proportion of patients who had a same-day discharge increased from 4.5% in 2009 to 28.6% in the fourth quarter of 2017.

Risk-adjusted 30-day mortality did not change in that time, while risk-adjusted rehospitalization decreased over time and more quickly when patients had same-day discharge.

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, and Jonathan G. Sung, MBCHB, both of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying article that, “Advances in the devices and techniques of PCI have improved the safety and efficacy of the procedure. In selected patients, same-day discharge has become possible, and overnight in-hospital observation can be avoided. By reducing unnecessary hospital stays, both patients and hospitals could benefit.”

Evan Garden, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, presented findings at the American Urological Association 2021 annual meeting that show patients selected for same-day discharge after partial or radical nephrectomy did not have increased rates of postoperative complications or readmissions in the immediate postoperative period, compared with standard discharge of 1-3 days.

Case studies in nephrectomy

While several case studies have looked at the feasibility and safety of performing partial and radical nephrectomy with same-day discharge in select cases, “this topic has not been addressed on a national level,” Mr. Garden said.

Few patients who have partial or radical nephrectomies have same-day discharges. The researchers found that fewer than 1% of patients who have either procedure in the sample studied were discharged the same day.

Researchers used the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, a nationally representative deidentified database that prospectively tracks patient characteristics and 30-day perioperative outcomes for major inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures at more than 700 hospitals.

They extracted all minimally invasive partial and radical nephrectomies from 2012 to 2019 and refined the cohort to 28,140 patients who were theoretically eligible for same-day discharge: Of those, 237 (0.8%) had SSD, and 27,903 (99.2%) had a standard-length discharge (SLD).

The team found that there were no differences in 30-day complications or readmissions between same-day discharge (Clavien-Dindo [CD] I/II, 4.22%; CD III, 0%; CD IV, 1.27%; readmission, 4.64%); and SLD (CD I/II, 4.11%; CD III, 0.95%; CD IV, 0.79%; readmission, 3.90%; all P > .05).

Controlling for demographic and clinical variables, SDD was not associated with greater risk of 30-day complications or readmissions (CD I/II: odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-2.048; P = .813; CD IV: OR 1.699; 95% CI, 0.537-5.375; P = .367; readmission: OR, 1.254; 95% CI, 0.681-2.31; P = .467).

Mr. Garden and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Lane reports no relevant financial relationships.

Urologist Ronney Abaza, MD, a robotic surgery specialist in Dublin, Ohio, and colleagues, reviewed robotic surgeries at their hospital during COVID-19 restrictions on surgery in Ohio between March 17 and June 5, 2020, and compared them with robotic procedures before COVID-19 and after restrictions were lifted. They published their results in Urology.

Since 2016, the hospital has offered the option of same-day discharge (SDD) to all robotic urologic surgery patients, regardless of procedure or patient-specific factors.

Among patients who had surgery during COVID-19 restrictions, 98% (87/89 patients) opted for SDD versus 52% in the group having surgery before the restrictions (P < .00001). After the COVID-19 surgery restrictions were lifted, the higher rate of SDD remained at 98%.

“There were no differences in 30-day complications or readmissions between SDD and overnight patients,” the authors write.

The right patient, the right motivation for successful surgery

Brian Lane, MD, PhD, a urologic oncologist with Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, told this news organization that, for nephrectomies, uptake of same-day discharge will continue to be slow.

“You have to have the right patient, the right patient motivation, and the surgery has to go smoothly,” he said. “If you start sending everyone home the same day, you will certainly see readmissions,” he said.

Dr. Lane is part of the Michigan Urologic Surgery Improvement Collaborative and he said the group recently looked at same-day discharge outcomes after robotic prostatectomies with SDD as compared with 1-2 nights in the hospital.

The work has not yet been published but, “There was a slight signal that there were increased readmissions with same-day discharge vs. 0-1 day,” he said.

A paper on outcomes of same-day discharge in total knee arthroplasty in the Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery found a higher risk of perioperative complications “including component failure, surgical site infection, knee stiffness, and deep vein thrombosis.” Researchers compared outcomes between 4,391 patients who underwent outpatient TKA and 128,951 patients who underwent inpatient TKA.

But for other many surgeries, same-day discharge numbers are increasing without worsening outcomes.

A paper in the Journal of Robotic Surgery found that same-day discharge following robotic-assisted endometrial cancer staging is “safe and feasible.”

Stephen Bradley, MD, MPH, with the Minneapolis Heart Institute in Minneapolis, and colleagues write in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Interventions that they found a large increase in the use of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was not associated with worse 30-day mortality rates or readmission.

In that study, 114,461 patients were discharged the same day they underwent PCI. The proportion of patients who had a same-day discharge increased from 4.5% in 2009 to 28.6% in the fourth quarter of 2017.

Risk-adjusted 30-day mortality did not change in that time, while risk-adjusted rehospitalization decreased over time and more quickly when patients had same-day discharge.

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, and Jonathan G. Sung, MBCHB, both of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying article that, “Advances in the devices and techniques of PCI have improved the safety and efficacy of the procedure. In selected patients, same-day discharge has become possible, and overnight in-hospital observation can be avoided. By reducing unnecessary hospital stays, both patients and hospitals could benefit.”

Evan Garden, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, presented findings at the American Urological Association 2021 annual meeting that show patients selected for same-day discharge after partial or radical nephrectomy did not have increased rates of postoperative complications or readmissions in the immediate postoperative period, compared with standard discharge of 1-3 days.

Case studies in nephrectomy

While several case studies have looked at the feasibility and safety of performing partial and radical nephrectomy with same-day discharge in select cases, “this topic has not been addressed on a national level,” Mr. Garden said.

Few patients who have partial or radical nephrectomies have same-day discharges. The researchers found that fewer than 1% of patients who have either procedure in the sample studied were discharged the same day.

Researchers used the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, a nationally representative deidentified database that prospectively tracks patient characteristics and 30-day perioperative outcomes for major inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures at more than 700 hospitals.

They extracted all minimally invasive partial and radical nephrectomies from 2012 to 2019 and refined the cohort to 28,140 patients who were theoretically eligible for same-day discharge: Of those, 237 (0.8%) had SSD, and 27,903 (99.2%) had a standard-length discharge (SLD).

The team found that there were no differences in 30-day complications or readmissions between same-day discharge (Clavien-Dindo [CD] I/II, 4.22%; CD III, 0%; CD IV, 1.27%; readmission, 4.64%); and SLD (CD I/II, 4.11%; CD III, 0.95%; CD IV, 0.79%; readmission, 3.90%; all P > .05).

Controlling for demographic and clinical variables, SDD was not associated with greater risk of 30-day complications or readmissions (CD I/II: odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-2.048; P = .813; CD IV: OR 1.699; 95% CI, 0.537-5.375; P = .367; readmission: OR, 1.254; 95% CI, 0.681-2.31; P = .467).

Mr. Garden and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Lane reports no relevant financial relationships.

Urologist Ronney Abaza, MD, a robotic surgery specialist in Dublin, Ohio, and colleagues, reviewed robotic surgeries at their hospital during COVID-19 restrictions on surgery in Ohio between March 17 and June 5, 2020, and compared them with robotic procedures before COVID-19 and after restrictions were lifted. They published their results in Urology.

Since 2016, the hospital has offered the option of same-day discharge (SDD) to all robotic urologic surgery patients, regardless of procedure or patient-specific factors.

Among patients who had surgery during COVID-19 restrictions, 98% (87/89 patients) opted for SDD versus 52% in the group having surgery before the restrictions (P < .00001). After the COVID-19 surgery restrictions were lifted, the higher rate of SDD remained at 98%.

“There were no differences in 30-day complications or readmissions between SDD and overnight patients,” the authors write.

The right patient, the right motivation for successful surgery

Brian Lane, MD, PhD, a urologic oncologist with Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, told this news organization that, for nephrectomies, uptake of same-day discharge will continue to be slow.

“You have to have the right patient, the right patient motivation, and the surgery has to go smoothly,” he said. “If you start sending everyone home the same day, you will certainly see readmissions,” he said.

Dr. Lane is part of the Michigan Urologic Surgery Improvement Collaborative and he said the group recently looked at same-day discharge outcomes after robotic prostatectomies with SDD as compared with 1-2 nights in the hospital.

The work has not yet been published but, “There was a slight signal that there were increased readmissions with same-day discharge vs. 0-1 day,” he said.

A paper on outcomes of same-day discharge in total knee arthroplasty in the Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery found a higher risk of perioperative complications “including component failure, surgical site infection, knee stiffness, and deep vein thrombosis.” Researchers compared outcomes between 4,391 patients who underwent outpatient TKA and 128,951 patients who underwent inpatient TKA.

But for other many surgeries, same-day discharge numbers are increasing without worsening outcomes.

A paper in the Journal of Robotic Surgery found that same-day discharge following robotic-assisted endometrial cancer staging is “safe and feasible.”

Stephen Bradley, MD, MPH, with the Minneapolis Heart Institute in Minneapolis, and colleagues write in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Interventions that they found a large increase in the use of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was not associated with worse 30-day mortality rates or readmission.

In that study, 114,461 patients were discharged the same day they underwent PCI. The proportion of patients who had a same-day discharge increased from 4.5% in 2009 to 28.6% in the fourth quarter of 2017.

Risk-adjusted 30-day mortality did not change in that time, while risk-adjusted rehospitalization decreased over time and more quickly when patients had same-day discharge.

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, and Jonathan G. Sung, MBCHB, both of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying article that, “Advances in the devices and techniques of PCI have improved the safety and efficacy of the procedure. In selected patients, same-day discharge has become possible, and overnight in-hospital observation can be avoided. By reducing unnecessary hospital stays, both patients and hospitals could benefit.”

Evan Garden, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, presented findings at the American Urological Association 2021 annual meeting that show patients selected for same-day discharge after partial or radical nephrectomy did not have increased rates of postoperative complications or readmissions in the immediate postoperative period, compared with standard discharge of 1-3 days.

Case studies in nephrectomy

While several case studies have looked at the feasibility and safety of performing partial and radical nephrectomy with same-day discharge in select cases, “this topic has not been addressed on a national level,” Mr. Garden said.

Few patients who have partial or radical nephrectomies have same-day discharges. The researchers found that fewer than 1% of patients who have either procedure in the sample studied were discharged the same day.

Researchers used the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, a nationally representative deidentified database that prospectively tracks patient characteristics and 30-day perioperative outcomes for major inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures at more than 700 hospitals.

They extracted all minimally invasive partial and radical nephrectomies from 2012 to 2019 and refined the cohort to 28,140 patients who were theoretically eligible for same-day discharge: Of those, 237 (0.8%) had SSD, and 27,903 (99.2%) had a standard-length discharge (SLD).

The team found that there were no differences in 30-day complications or readmissions between same-day discharge (Clavien-Dindo [CD] I/II, 4.22%; CD III, 0%; CD IV, 1.27%; readmission, 4.64%); and SLD (CD I/II, 4.11%; CD III, 0.95%; CD IV, 0.79%; readmission, 3.90%; all P > .05).

Controlling for demographic and clinical variables, SDD was not associated with greater risk of 30-day complications or readmissions (CD I/II: odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-2.048; P = .813; CD IV: OR 1.699; 95% CI, 0.537-5.375; P = .367; readmission: OR, 1.254; 95% CI, 0.681-2.31; P = .467).

Mr. Garden and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Lane reports no relevant financial relationships.

FDA issues stronger safety requirements for breast implants

The Food and Drug Administration on Oct. 27 announced stronger safety requirements for breast implants, restricting sales of implants only to providers and health facilities that review potential risks of the devices with patients before surgery, via a “Patient Decision Checklist.” The agency also placed a boxed warning – the strongest warning that the FDA requires – on all legally marketed breast implants.

“Protecting patients’ health when they are treated with a medical device is our most important priority,” Binita Ashar, MD, director of the Office of Surgical and Infection Control Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press release. “In recent years, the FDA has sought more ways to increase patients’ access to clear and understandable information about the benefits and risks of breast implants. By strengthening the safety requirements for manufacturers, the FDA is working to close information gaps for anyone who may be considering breast implant surgery.”

This announcement comes 10 years after the FDA issued a comprehensive safety update on silicone gel–filled implants, which reported a possible association between these devices and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). The studies reviewed in the 2011 document also noted that a “significant percentage of women who receive silicone gel–filled breast implants experience complications and adverse outcomes,” the most common being repeat operation, implant removal, rupture, or capsular contracture (scar tissue tightening around the implant).

Breast augmentation has been one of the top five cosmetic procedures in the United States since 2006, according to the American Society for Plastic Surgery, with more than 400,000 people getting breast implants in 2019. Nearly 300,000 were for cosmetic reasons, and more than 100,000 were for breast reconstruction after mastectomies.

In 2019, the FDA proposed adding a boxed warning for breast implants, stating that the devices do not last an entire lifetime; that over time the risk for complications increases; and that breast implants have been associated with ALCL, and also may be associated with systemic symptoms such as fatigue, joint pain, and brain fog. The Oct. 27 FDA action now requires that manufacturers update breast implant packaging to include that information in a boxed warning, as well as the following:

- A patient-decision checklist

- Updated silicone gel–filled breast implant rupture screening recommendations

- A device description including materials used in the device

- Patient device ID cards

The updated label changes must be present on manufacturers’ websites in 30 days, the FDA said.

The new requirements have received largely positive reactions from both physicians and patient organizations. In an emailed statement to this news organization, Lynn Jeffers, MD, MBA, the immediate past president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said that “ASPS has always supported patients being fully informed about their choices and the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the options available. “We look forward to our continued collaboration with the FDA on the safety of implants and other devices.”

Maria Gmitro, president and cofounder of the Breast Implant Safety Alliance, an all-volunteer nonprofit based in Charleston, S.C., said that some of the language in the patient checklist could be stronger, especially when referring to breast implant–associated ALCL.

To inform patients of risks more clearly, “it’s the words like ‘associated with’ that we feel need to be stronger” she said in an interview. She also noted that women who already have breast implants may not be aware of these potential complications, which these new FDA requirements do not address.

But overall, the nonprofit was “thrilled” with the announcement, Ms. Gmitro said. “Placing restrictions on breast implants is a really big step, and we applaud the FDA’s efforts. This is information that every patient considering breast implants should know, and we’ve been advocating for better informed consent.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration on Oct. 27 announced stronger safety requirements for breast implants, restricting sales of implants only to providers and health facilities that review potential risks of the devices with patients before surgery, via a “Patient Decision Checklist.” The agency also placed a boxed warning – the strongest warning that the FDA requires – on all legally marketed breast implants.

“Protecting patients’ health when they are treated with a medical device is our most important priority,” Binita Ashar, MD, director of the Office of Surgical and Infection Control Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press release. “In recent years, the FDA has sought more ways to increase patients’ access to clear and understandable information about the benefits and risks of breast implants. By strengthening the safety requirements for manufacturers, the FDA is working to close information gaps for anyone who may be considering breast implant surgery.”

This announcement comes 10 years after the FDA issued a comprehensive safety update on silicone gel–filled implants, which reported a possible association between these devices and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). The studies reviewed in the 2011 document also noted that a “significant percentage of women who receive silicone gel–filled breast implants experience complications and adverse outcomes,” the most common being repeat operation, implant removal, rupture, or capsular contracture (scar tissue tightening around the implant).

Breast augmentation has been one of the top five cosmetic procedures in the United States since 2006, according to the American Society for Plastic Surgery, with more than 400,000 people getting breast implants in 2019. Nearly 300,000 were for cosmetic reasons, and more than 100,000 were for breast reconstruction after mastectomies.

In 2019, the FDA proposed adding a boxed warning for breast implants, stating that the devices do not last an entire lifetime; that over time the risk for complications increases; and that breast implants have been associated with ALCL, and also may be associated with systemic symptoms such as fatigue, joint pain, and brain fog. The Oct. 27 FDA action now requires that manufacturers update breast implant packaging to include that information in a boxed warning, as well as the following:

- A patient-decision checklist

- Updated silicone gel–filled breast implant rupture screening recommendations

- A device description including materials used in the device

- Patient device ID cards

The updated label changes must be present on manufacturers’ websites in 30 days, the FDA said.

The new requirements have received largely positive reactions from both physicians and patient organizations. In an emailed statement to this news organization, Lynn Jeffers, MD, MBA, the immediate past president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said that “ASPS has always supported patients being fully informed about their choices and the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the options available. “We look forward to our continued collaboration with the FDA on the safety of implants and other devices.”

Maria Gmitro, president and cofounder of the Breast Implant Safety Alliance, an all-volunteer nonprofit based in Charleston, S.C., said that some of the language in the patient checklist could be stronger, especially when referring to breast implant–associated ALCL.

To inform patients of risks more clearly, “it’s the words like ‘associated with’ that we feel need to be stronger” she said in an interview. She also noted that women who already have breast implants may not be aware of these potential complications, which these new FDA requirements do not address.

But overall, the nonprofit was “thrilled” with the announcement, Ms. Gmitro said. “Placing restrictions on breast implants is a really big step, and we applaud the FDA’s efforts. This is information that every patient considering breast implants should know, and we’ve been advocating for better informed consent.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration on Oct. 27 announced stronger safety requirements for breast implants, restricting sales of implants only to providers and health facilities that review potential risks of the devices with patients before surgery, via a “Patient Decision Checklist.” The agency also placed a boxed warning – the strongest warning that the FDA requires – on all legally marketed breast implants.

“Protecting patients’ health when they are treated with a medical device is our most important priority,” Binita Ashar, MD, director of the Office of Surgical and Infection Control Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press release. “In recent years, the FDA has sought more ways to increase patients’ access to clear and understandable information about the benefits and risks of breast implants. By strengthening the safety requirements for manufacturers, the FDA is working to close information gaps for anyone who may be considering breast implant surgery.”

This announcement comes 10 years after the FDA issued a comprehensive safety update on silicone gel–filled implants, which reported a possible association between these devices and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). The studies reviewed in the 2011 document also noted that a “significant percentage of women who receive silicone gel–filled breast implants experience complications and adverse outcomes,” the most common being repeat operation, implant removal, rupture, or capsular contracture (scar tissue tightening around the implant).

Breast augmentation has been one of the top five cosmetic procedures in the United States since 2006, according to the American Society for Plastic Surgery, with more than 400,000 people getting breast implants in 2019. Nearly 300,000 were for cosmetic reasons, and more than 100,000 were for breast reconstruction after mastectomies.

In 2019, the FDA proposed adding a boxed warning for breast implants, stating that the devices do not last an entire lifetime; that over time the risk for complications increases; and that breast implants have been associated with ALCL, and also may be associated with systemic symptoms such as fatigue, joint pain, and brain fog. The Oct. 27 FDA action now requires that manufacturers update breast implant packaging to include that information in a boxed warning, as well as the following:

- A patient-decision checklist

- Updated silicone gel–filled breast implant rupture screening recommendations

- A device description including materials used in the device

- Patient device ID cards

The updated label changes must be present on manufacturers’ websites in 30 days, the FDA said.

The new requirements have received largely positive reactions from both physicians and patient organizations. In an emailed statement to this news organization, Lynn Jeffers, MD, MBA, the immediate past president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said that “ASPS has always supported patients being fully informed about their choices and the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the options available. “We look forward to our continued collaboration with the FDA on the safety of implants and other devices.”

Maria Gmitro, president and cofounder of the Breast Implant Safety Alliance, an all-volunteer nonprofit based in Charleston, S.C., said that some of the language in the patient checklist could be stronger, especially when referring to breast implant–associated ALCL.

To inform patients of risks more clearly, “it’s the words like ‘associated with’ that we feel need to be stronger” she said in an interview. She also noted that women who already have breast implants may not be aware of these potential complications, which these new FDA requirements do not address.

But overall, the nonprofit was “thrilled” with the announcement, Ms. Gmitro said. “Placing restrictions on breast implants is a really big step, and we applaud the FDA’s efforts. This is information that every patient considering breast implants should know, and we’ve been advocating for better informed consent.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Racial disparities found in treatment of tubal pregnancies

Black and Latina women are more likely to have an open surgery compared with a minimally invasive procedure to treat ectopic pregnancy, according to research presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2021 meeting.

The researchers found that Black and Latina women had 50% lesser odds of undergoing laparoscopic surgery, a minimally invasive procedure, compared to their White peers.

“We see these disparities in minority populations, [especially in] women with regard to so many other aspects of [gynecologic] surgery,” study author Alexandra Huttler, MD, said in an interview. “The fact that these disparities exist [in the treatment of tubal pregnancies] was unfortunately not surprising to us.”

Dr. Huttler and her team analyzed data from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, which followed more than 9,000 patients who had undergone surgical management of a tubal ectopic pregnancy between 2010 and 2019. Of the group, 85% underwent laparoscopic surgery while 14% had open surgery, which requires a longer recovery time.

The proportion of cases performed laparoscopically increased from 81% in 2010 to 91% in 2019. However, a disproportionate number of Black and Latina women underwent open surgery to treat ectopic pregnancies during this time. Because they are more invasive, open surgeries are associated with longer operative times, hospital stays, and increased complications, Dr. Huttler said. They are typically associated with more pain and patients are more likely to be admitted to the hospital for postoperative care.

On the other hand, minimally invasive surgeries are associated with decreased operative time, “less recovery and less pain,” Dr. Huttler explained.

The researchers also looked at trends of the related surgical procedure salpingectomy, which is surgical removal of one or both fallopian tubes versus salpingostomy, a surgical unblocking of the tube. Of the group, 91% underwent salpingectomy and 9% underwent salpingostomy.

Researchers found that Black and Latina women had 78% and 54% greater odds, respectively, of receiving a salpingectomy. However, the clinical significance of these findings are unclear because there are “many factors” that are patient and case specific, Dr. Huttler said.

The study is important and adds to a litany of studies that have shown that women of color do not receive optimal care, said Ruben Alvero, MD, who was not involved in the study.

“Women of color in general have seen compromises in their care at many levels in the system,” Dr. Alvero, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “We really have to do a massive overhaul of how we treat women of color so they get the same level of treatment that all other populations receive.”

While the factors contributing to these health disparities can be complicated, Dr. Alvero said that one reason for this multivariate discrepancy could be that Black and Latina women tend to seek care at, or only have access to, underresourced hospitals.

Dr. Huttler said she hopes her findings prompt further discussion of these disparities.

“There really are disparities at all levels of care here and figuring out what the root of this is certainly requires further research,” Dr. Huttler said.

The experts interviewed disclosed no conflicts on interests.

Black and Latina women are more likely to have an open surgery compared with a minimally invasive procedure to treat ectopic pregnancy, according to research presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2021 meeting.

The researchers found that Black and Latina women had 50% lesser odds of undergoing laparoscopic surgery, a minimally invasive procedure, compared to their White peers.

“We see these disparities in minority populations, [especially in] women with regard to so many other aspects of [gynecologic] surgery,” study author Alexandra Huttler, MD, said in an interview. “The fact that these disparities exist [in the treatment of tubal pregnancies] was unfortunately not surprising to us.”

Dr. Huttler and her team analyzed data from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, which followed more than 9,000 patients who had undergone surgical management of a tubal ectopic pregnancy between 2010 and 2019. Of the group, 85% underwent laparoscopic surgery while 14% had open surgery, which requires a longer recovery time.

The proportion of cases performed laparoscopically increased from 81% in 2010 to 91% in 2019. However, a disproportionate number of Black and Latina women underwent open surgery to treat ectopic pregnancies during this time. Because they are more invasive, open surgeries are associated with longer operative times, hospital stays, and increased complications, Dr. Huttler said. They are typically associated with more pain and patients are more likely to be admitted to the hospital for postoperative care.

On the other hand, minimally invasive surgeries are associated with decreased operative time, “less recovery and less pain,” Dr. Huttler explained.

The researchers also looked at trends of the related surgical procedure salpingectomy, which is surgical removal of one or both fallopian tubes versus salpingostomy, a surgical unblocking of the tube. Of the group, 91% underwent salpingectomy and 9% underwent salpingostomy.

Researchers found that Black and Latina women had 78% and 54% greater odds, respectively, of receiving a salpingectomy. However, the clinical significance of these findings are unclear because there are “many factors” that are patient and case specific, Dr. Huttler said.

The study is important and adds to a litany of studies that have shown that women of color do not receive optimal care, said Ruben Alvero, MD, who was not involved in the study.

“Women of color in general have seen compromises in their care at many levels in the system,” Dr. Alvero, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “We really have to do a massive overhaul of how we treat women of color so they get the same level of treatment that all other populations receive.”

While the factors contributing to these health disparities can be complicated, Dr. Alvero said that one reason for this multivariate discrepancy could be that Black and Latina women tend to seek care at, or only have access to, underresourced hospitals.

Dr. Huttler said she hopes her findings prompt further discussion of these disparities.

“There really are disparities at all levels of care here and figuring out what the root of this is certainly requires further research,” Dr. Huttler said.

The experts interviewed disclosed no conflicts on interests.

Black and Latina women are more likely to have an open surgery compared with a minimally invasive procedure to treat ectopic pregnancy, according to research presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2021 meeting.

The researchers found that Black and Latina women had 50% lesser odds of undergoing laparoscopic surgery, a minimally invasive procedure, compared to their White peers.

“We see these disparities in minority populations, [especially in] women with regard to so many other aspects of [gynecologic] surgery,” study author Alexandra Huttler, MD, said in an interview. “The fact that these disparities exist [in the treatment of tubal pregnancies] was unfortunately not surprising to us.”

Dr. Huttler and her team analyzed data from the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, which followed more than 9,000 patients who had undergone surgical management of a tubal ectopic pregnancy between 2010 and 2019. Of the group, 85% underwent laparoscopic surgery while 14% had open surgery, which requires a longer recovery time.

The proportion of cases performed laparoscopically increased from 81% in 2010 to 91% in 2019. However, a disproportionate number of Black and Latina women underwent open surgery to treat ectopic pregnancies during this time. Because they are more invasive, open surgeries are associated with longer operative times, hospital stays, and increased complications, Dr. Huttler said. They are typically associated with more pain and patients are more likely to be admitted to the hospital for postoperative care.

On the other hand, minimally invasive surgeries are associated with decreased operative time, “less recovery and less pain,” Dr. Huttler explained.

The researchers also looked at trends of the related surgical procedure salpingectomy, which is surgical removal of one or both fallopian tubes versus salpingostomy, a surgical unblocking of the tube. Of the group, 91% underwent salpingectomy and 9% underwent salpingostomy.

Researchers found that Black and Latina women had 78% and 54% greater odds, respectively, of receiving a salpingectomy. However, the clinical significance of these findings are unclear because there are “many factors” that are patient and case specific, Dr. Huttler said.

The study is important and adds to a litany of studies that have shown that women of color do not receive optimal care, said Ruben Alvero, MD, who was not involved in the study.

“Women of color in general have seen compromises in their care at many levels in the system,” Dr. Alvero, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “We really have to do a massive overhaul of how we treat women of color so they get the same level of treatment that all other populations receive.”

While the factors contributing to these health disparities can be complicated, Dr. Alvero said that one reason for this multivariate discrepancy could be that Black and Latina women tend to seek care at, or only have access to, underresourced hospitals.

Dr. Huttler said she hopes her findings prompt further discussion of these disparities.

“There really are disparities at all levels of care here and figuring out what the root of this is certainly requires further research,” Dr. Huttler said.

The experts interviewed disclosed no conflicts on interests.

FROM ASRM 2021

Medical comanagement did not improve hip fracture outcomes

Background: Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is common. Prior evidence comes from mostly single-center studies, with most improvements being in process indicators such as length of stay and staff satisfaction.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.

Synopsis: With the NSQIP database targeted user file for hip fracture of 19,896 patients from 2016 to 2017, unadjusted analysis showed patients in the medical comanagement cohort were older with higher burden of comorbidities, higher morbidity (19.5% vs. 9.6%, odds ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.98-2.63; P < .0001), and higher mortality rate (6.9% vs. 4.0%; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.44-2.22; P < .0001). Both cohorts had similar proportion of patients participating in a standardized hip fracture program. After propensity score matching, patients in the comanagement cohort continued to show inferior morbidity (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.52-2.20; P < .0001) and mortality (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = .033).

This study failed to show superior outcomes in comanagement patients. The retrospective nature and propensity matching will lead to the question of unmeasured confounding in this large multinational database.

Bottom line: Medical comanagement of hip fractures was not associated with improved outcomes in the NSQIP database.

Citation: Maxwell BG, Mirza A. Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is not associated with superior perioperative outcomes: A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:468-74.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is common. Prior evidence comes from mostly single-center studies, with most improvements being in process indicators such as length of stay and staff satisfaction.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.

Synopsis: With the NSQIP database targeted user file for hip fracture of 19,896 patients from 2016 to 2017, unadjusted analysis showed patients in the medical comanagement cohort were older with higher burden of comorbidities, higher morbidity (19.5% vs. 9.6%, odds ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.98-2.63; P < .0001), and higher mortality rate (6.9% vs. 4.0%; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.44-2.22; P < .0001). Both cohorts had similar proportion of patients participating in a standardized hip fracture program. After propensity score matching, patients in the comanagement cohort continued to show inferior morbidity (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.52-2.20; P < .0001) and mortality (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = .033).

This study failed to show superior outcomes in comanagement patients. The retrospective nature and propensity matching will lead to the question of unmeasured confounding in this large multinational database.

Bottom line: Medical comanagement of hip fractures was not associated with improved outcomes in the NSQIP database.

Citation: Maxwell BG, Mirza A. Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is not associated with superior perioperative outcomes: A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:468-74.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is common. Prior evidence comes from mostly single-center studies, with most improvements being in process indicators such as length of stay and staff satisfaction.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.

Synopsis: With the NSQIP database targeted user file for hip fracture of 19,896 patients from 2016 to 2017, unadjusted analysis showed patients in the medical comanagement cohort were older with higher burden of comorbidities, higher morbidity (19.5% vs. 9.6%, odds ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.98-2.63; P < .0001), and higher mortality rate (6.9% vs. 4.0%; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.44-2.22; P < .0001). Both cohorts had similar proportion of patients participating in a standardized hip fracture program. After propensity score matching, patients in the comanagement cohort continued to show inferior morbidity (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.52-2.20; P < .0001) and mortality (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = .033).

This study failed to show superior outcomes in comanagement patients. The retrospective nature and propensity matching will lead to the question of unmeasured confounding in this large multinational database.

Bottom line: Medical comanagement of hip fractures was not associated with improved outcomes in the NSQIP database.

Citation: Maxwell BG, Mirza A. Medical comanagement of hip fracture patients is not associated with superior perioperative outcomes: A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:468-74.

Dr. Lockwood is a hospitalist and chief of quality, performance, and patient safety at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

True or false: Breast density increases breast cancer risk

Which of the following statements about breast density is TRUE?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

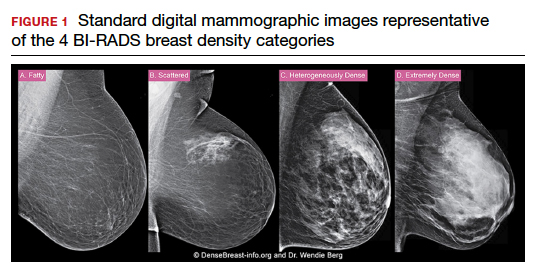

D. The risks associated with dense breast tissue are 2-fold: Dense tissue can mask cancer on a mammogram, and having dense breasts also increases the risk of developing breast cancer. As breast density increases, the sensitivity of mammography decreases, and the risk of developing breast cancer increases.

A woman’s breast density is usually determined by a radiologist’s visual evaluation of the mammogram. Breast density also can be measured quantitatively by computer software or estimated on computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Breast density cannot be determined by the way a breast looks or feels.

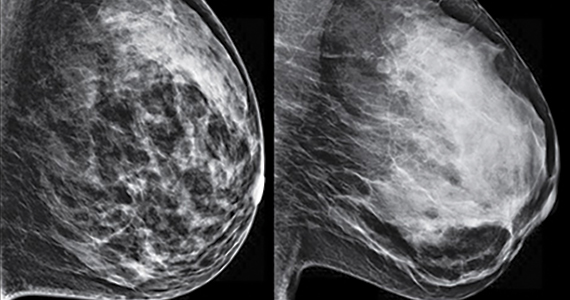

Breast density and mammographic sensitivity

Cancers can be hidden or “masked” by dense tissue. On a mammogram, cancer is white. Normal dense tissue also appears white. If a cancer develops in an area of normal dense tissue, it can be harder or sometimes impossible to see it on the mammogram, like trying to see a snowman in a blizzard. As breast density increases, the ability to see cancer on mammography decreases (FIGURE 1).

Standard 2D mammography has been shown to miss about 40% of cancers present in women with extremely dense breasts and 25% of cancers present in women with heterogeneously dense breasts.1-6 A cancer still can be masked on tomosynthesis (3D mammography) if it occurs in an area of dense tissue (where breast cancers more commonly occur), and tomosynthesis does not improve cancer detection appreciably in women with extremely dense breasts. To find cancer in a woman with dense breasts, additional screening beyond mammography should be considered.

Breast density and breast cancer risk

Dense breast tissue not only reduces mammography effectiveness, it also is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer: the denser the breast, the higher the risk.7 A meta-analysis across many studies concluded that magnitude of risk increases with each increase in density category, and women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have a 4-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than do women with fatty breasts (category A), with upper limit of nearly 6-fold greater risk (FIGURE 2).8

Most women do not have fatty breasts, however. More women have breasts with scattered fibroglandular density.9 Women with heterogeneously dense breasts (category C) have about a 1.5-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than those with scattered fibroglandular density (category B), while women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have about a 2-fold greater risk.

There are probably several reasons that dense tissue increases breast cancer risk. One is that cancers arise microscopically in the glandular tissue. The more glandular tissue, the more susceptible tissue where cancer can develop. Glandular cells divide with hormonal stimulation throughout a woman’s lifetime, and each time a cell divides, “mistakes” can be made. An accumulation of mistakes can result in cancer. The more glandular the tissue, the greater the breast cancer risk. Women who have had breast reduction experience a reduced risk for breast cancer: thus, even a reduced absolute amount of glandular tissue reduces the risk for breast cancer. The second is that the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this is observed with fibrous breast tissue more than fatty breast tissue. ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307:1394-1404. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2012.388.

- Destounis S, Johnston L, Highnam R, et al. Using volumetric breast density to quantify the potential masking risk of mammographic density. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:222-227. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16489.

- Kerlikowske K, Scott CG, Mahmoudzadeh AP, et al. Automated and clinical breast imaging reporting and data system density measures predict risk for screen-detected and interval cancers: a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:757-765. doi: 10.7326/M17-3008.

- Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165-175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667.

- Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL, et al. Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1081-1087. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1081.

- Wanders JOP, Holland K, Karssemeijer N, et al. The effect of volumetric breast density on the risk of screen-detected and interval breast cancers: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19:67. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0859-9.

- Society AC. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. American Cancer Society, Inc. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer -facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts -and-figures-2019-2020.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 23, 2021.

- McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1159-1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034.

- Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3830-3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4770.

Which of the following statements about breast density is TRUE?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

D. The risks associated with dense breast tissue are 2-fold: Dense tissue can mask cancer on a mammogram, and having dense breasts also increases the risk of developing breast cancer. As breast density increases, the sensitivity of mammography decreases, and the risk of developing breast cancer increases.

A woman’s breast density is usually determined by a radiologist’s visual evaluation of the mammogram. Breast density also can be measured quantitatively by computer software or estimated on computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Breast density cannot be determined by the way a breast looks or feels.

Breast density and mammographic sensitivity

Cancers can be hidden or “masked” by dense tissue. On a mammogram, cancer is white. Normal dense tissue also appears white. If a cancer develops in an area of normal dense tissue, it can be harder or sometimes impossible to see it on the mammogram, like trying to see a snowman in a blizzard. As breast density increases, the ability to see cancer on mammography decreases (FIGURE 1).

Standard 2D mammography has been shown to miss about 40% of cancers present in women with extremely dense breasts and 25% of cancers present in women with heterogeneously dense breasts.1-6 A cancer still can be masked on tomosynthesis (3D mammography) if it occurs in an area of dense tissue (where breast cancers more commonly occur), and tomosynthesis does not improve cancer detection appreciably in women with extremely dense breasts. To find cancer in a woman with dense breasts, additional screening beyond mammography should be considered.

Breast density and breast cancer risk

Dense breast tissue not only reduces mammography effectiveness, it also is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer: the denser the breast, the higher the risk.7 A meta-analysis across many studies concluded that magnitude of risk increases with each increase in density category, and women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have a 4-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than do women with fatty breasts (category A), with upper limit of nearly 6-fold greater risk (FIGURE 2).8

Most women do not have fatty breasts, however. More women have breasts with scattered fibroglandular density.9 Women with heterogeneously dense breasts (category C) have about a 1.5-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than those with scattered fibroglandular density (category B), while women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have about a 2-fold greater risk.

There are probably several reasons that dense tissue increases breast cancer risk. One is that cancers arise microscopically in the glandular tissue. The more glandular tissue, the more susceptible tissue where cancer can develop. Glandular cells divide with hormonal stimulation throughout a woman’s lifetime, and each time a cell divides, “mistakes” can be made. An accumulation of mistakes can result in cancer. The more glandular the tissue, the greater the breast cancer risk. Women who have had breast reduction experience a reduced risk for breast cancer: thus, even a reduced absolute amount of glandular tissue reduces the risk for breast cancer. The second is that the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this is observed with fibrous breast tissue more than fatty breast tissue. ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Which of the following statements about breast density is TRUE?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

D. The risks associated with dense breast tissue are 2-fold: Dense tissue can mask cancer on a mammogram, and having dense breasts also increases the risk of developing breast cancer. As breast density increases, the sensitivity of mammography decreases, and the risk of developing breast cancer increases.

A woman’s breast density is usually determined by a radiologist’s visual evaluation of the mammogram. Breast density also can be measured quantitatively by computer software or estimated on computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Breast density cannot be determined by the way a breast looks or feels.

Breast density and mammographic sensitivity

Cancers can be hidden or “masked” by dense tissue. On a mammogram, cancer is white. Normal dense tissue also appears white. If a cancer develops in an area of normal dense tissue, it can be harder or sometimes impossible to see it on the mammogram, like trying to see a snowman in a blizzard. As breast density increases, the ability to see cancer on mammography decreases (FIGURE 1).

Standard 2D mammography has been shown to miss about 40% of cancers present in women with extremely dense breasts and 25% of cancers present in women with heterogeneously dense breasts.1-6 A cancer still can be masked on tomosynthesis (3D mammography) if it occurs in an area of dense tissue (where breast cancers more commonly occur), and tomosynthesis does not improve cancer detection appreciably in women with extremely dense breasts. To find cancer in a woman with dense breasts, additional screening beyond mammography should be considered.

Breast density and breast cancer risk

Dense breast tissue not only reduces mammography effectiveness, it also is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer: the denser the breast, the higher the risk.7 A meta-analysis across many studies concluded that magnitude of risk increases with each increase in density category, and women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have a 4-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than do women with fatty breasts (category A), with upper limit of nearly 6-fold greater risk (FIGURE 2).8

Most women do not have fatty breasts, however. More women have breasts with scattered fibroglandular density.9 Women with heterogeneously dense breasts (category C) have about a 1.5-fold greater risk of developing breast cancer than those with scattered fibroglandular density (category B), while women with extremely dense breasts (category D) have about a 2-fold greater risk.

There are probably several reasons that dense tissue increases breast cancer risk. One is that cancers arise microscopically in the glandular tissue. The more glandular tissue, the more susceptible tissue where cancer can develop. Glandular cells divide with hormonal stimulation throughout a woman’s lifetime, and each time a cell divides, “mistakes” can be made. An accumulation of mistakes can result in cancer. The more glandular the tissue, the greater the breast cancer risk. Women who have had breast reduction experience a reduced risk for breast cancer: thus, even a reduced absolute amount of glandular tissue reduces the risk for breast cancer. The second is that the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this is observed with fibrous breast tissue more than fatty breast tissue. ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307:1394-1404. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2012.388.

- Destounis S, Johnston L, Highnam R, et al. Using volumetric breast density to quantify the potential masking risk of mammographic density. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:222-227. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16489.

- Kerlikowske K, Scott CG, Mahmoudzadeh AP, et al. Automated and clinical breast imaging reporting and data system density measures predict risk for screen-detected and interval cancers: a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:757-765. doi: 10.7326/M17-3008.

- Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165-175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667.

- Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL, et al. Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1081-1087. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1081.

- Wanders JOP, Holland K, Karssemeijer N, et al. The effect of volumetric breast density on the risk of screen-detected and interval breast cancers: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19:67. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0859-9.

- Society AC. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. American Cancer Society, Inc. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer -facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts -and-figures-2019-2020.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 23, 2021.

- McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1159-1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034.

- Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3830-3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4770.

- Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307:1394-1404. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2012.388.

- Destounis S, Johnston L, Highnam R, et al. Using volumetric breast density to quantify the potential masking risk of mammographic density. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:222-227. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16489.

- Kerlikowske K, Scott CG, Mahmoudzadeh AP, et al. Automated and clinical breast imaging reporting and data system density measures predict risk for screen-detected and interval cancers: a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:757-765. doi: 10.7326/M17-3008.

- Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165-175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667.

- Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL, et al. Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1081-1087. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1081.

- Wanders JOP, Holland K, Karssemeijer N, et al. The effect of volumetric breast density on the risk of screen-detected and interval breast cancers: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19:67. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0859-9.

- Society AC. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. American Cancer Society, Inc. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer -facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts -and-figures-2019-2020.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 23, 2021.

- McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1159-1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034.

- Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3830-3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4770.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

MDs doing wrong-site surgery: Why is it still happening?

In July 2021, University Hospitals, in Cleveland, announced that its staff had transplanted a kidney into the wrong patient. Although the patient who received the kidney was recovering well, the patient who was supposed to have received the kidney was skipped over. As a result of the error, two employees were placed on administrative leave and the incident was being investigated, the hospital announced.

In April 2020, an interventional radiologist at Boca Raton Regional Hospital, in Boca Raton, Fla., was sued for allegedly placing a stent into the wrong kidney of an 80-year-old patient. Using fluoroscopic guidance, the doctor removed an old stent from the right side but incorrectly replaced it with a new stent on the left side, according to an interview conducted by this news organization with the patient’s lawyers at Searcy Law, in West Palm Beach.

“The problem is that it is so rare that doctors don’t focus on it,” says Mary R. Kwaan, MD, a colorectal surgeon at UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

A 2006 study in which Kwaan was the lead author concluded that there was one wrong-site surgery for every 112,994 surgeries. Those mistakes can add up. A 2006 study estimated that 25 to 52 wrong-site surgeries were performed each week in the United States.

“Many surgeons don’t think it can happen to them, so they don’t take extra precautions,” says David Mayer, MD, executive director of the MedStar Institute for Quality and Safety, in Washington, DC. “When they make a wrong-site error, usually the first thing they say is, ‘I never thought this would happen to me,’ ” he says.

Wrong-site surgeries are considered sentinel events -- the worst kinds of medical errors. The Sullivan Group, a patient safety consultancy based in Colorado, reports that in 2013, 2.7% of patients who were involved in wrong-site surgeries died and 41% experienced some type of permanent injury. The mean malpractice payment was $127,000.

Some malpractice payments are much higher. In 2013, a Maryland ob.gyn paid a $1.42 million malpractice award for removing the wrong ovary from a woman in 2009. In 2017, a Pennsylvania urologist paid $870,000 for removing the wrong testicle from a man in 2013.

Wrong-site surgery often involves experienced surgeons

One might think that wrong-site surgeries usually involve younger or less-experienced surgeons, but that’s not the case; two thirds of the surgeons who perform wrong-site surgeries are in their 40s and 50s, compared with fewer than 25% younger than 40.

In a rather chilling statistic, in a 2013 survey, 12.4% of doctors who were involved in sentinel events in general had claims for more than one event.

These errors are more common in certain specialties. In a study reported in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Spine, 25% of orthopedic surgeons reported performing at least one wrong-site surgery during their career.

Within orthopedics, spine surgery is ground zero for wrong-site surgery. “Finding the site in spine surgery can be more difficult than in common left-right orthopedic procedures,” says Joseph A. Bosco III, a New York City orthopedist.

A 2007 study found that 25% of neurosurgeons had performed wrong-site surgeries. In Missouri in 2013, for example, a 53-year-old patient who was scheduled to undergo a left-sided craniotomy bypass allegedly underwent a right-sided craniotomy and was unable to speak after surgery.

Wrong-site surgeries are also performed by general surgeons, urologists, cardiologists, otolaryngologists, and ophthalmologists. A 2021 lawsuit accused a Tampa urologist of removing the patient’s wrong testicle. And a 2019 lawsuit accused a Chicago ophthalmologist of operating on the wrong eye to remove a cyst.

It’s not just the surgeon’s mistake

Mistakes are not only made by the surgeon in the operating room (OR). They can be made by staff when scheduling a surgery, radiologists and pathologists when writing their reports for surgery, and by team members in the OR.