User login

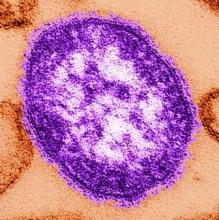

Measles infection linked to impaired ‘immune memory’

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science.

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 the children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

The study did find increases in measles virus–specific antigens in children both after measles infection and MMR vaccination. However the authors did not detect any changes in total IgG, IgA, or IgM levels.

Dr. Mina and associates wrote.

They also noted that controls who received the MMR vaccine showed a marked increase in overall antibody repertoire.

In a separate investigation reported in Science Immunology, Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles to determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgVH-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B-cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IgVH-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IgVH-J genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IgVH genes, Dr. Petrova and associates reported.

The study by Mina et al. was supported by grants from various U.S., European, and Finnish foundations and national organizations. Some of the coauthors had relationships with biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, and three reported a patent holding related to technology used in the study. The study by Petrova et al. was funded by grants to the investigators from various Indonesian and German organizations and the Wellcome Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Mina M et al. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366:599-606; Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125.

As a result of reduced vaccination, after decades of decline, the number of worldwide cases of measles has increased by nearly 300% since 2018. Epidemiologic evidence has associated measles infections with increases in morbidity and mortality for as long as 5 years after the infection and suggests that, in the prevaccine era, measles virus may have been associated with up to 50% of all childhood deaths, mostly because of nonmeasles infections. Measles replication in immune cells has been hypothesized to impair immune memory, potentially causing what some scientists call “immunological amnesia.”A measles virus receptor, called CD150/ SLAMF1, is highly expressed on memory T, B, and plasma cells. Measles virus gains entry to these immune memory cells using that receptor and kills the cells.

The scientists stated that it could take months or years to return the immune repertoire back to baseline. During the rebuilding process, children would be at increased risk for infectious diseases they had previously experienced.

In a second outstanding paper, Petrova et al. in Science Immunology studied B cells before and after measles infection, and identified two immunologic consequences: The naive B-cell pool was depleted, leading to a return to immunologic immaturity, and the memory B-cell pool was depleted, resulting in compromised immune memory to previously encountered pathogens.

Thus, the link between measles infections and increased susceptibility to other infections and increased deaths from nonmeasles infectious diseases in the aftermath of measles has been revealed. This information adds new data to share with parents who consider refusing measles vaccination. The risks are far greater than getting measles.

Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He was asked to comment on the articles. Dr. Pichichero has no conflicts to declare.

As a result of reduced vaccination, after decades of decline, the number of worldwide cases of measles has increased by nearly 300% since 2018. Epidemiologic evidence has associated measles infections with increases in morbidity and mortality for as long as 5 years after the infection and suggests that, in the prevaccine era, measles virus may have been associated with up to 50% of all childhood deaths, mostly because of nonmeasles infections. Measles replication in immune cells has been hypothesized to impair immune memory, potentially causing what some scientists call “immunological amnesia.”A measles virus receptor, called CD150/ SLAMF1, is highly expressed on memory T, B, and plasma cells. Measles virus gains entry to these immune memory cells using that receptor and kills the cells.

The scientists stated that it could take months or years to return the immune repertoire back to baseline. During the rebuilding process, children would be at increased risk for infectious diseases they had previously experienced.

In a second outstanding paper, Petrova et al. in Science Immunology studied B cells before and after measles infection, and identified two immunologic consequences: The naive B-cell pool was depleted, leading to a return to immunologic immaturity, and the memory B-cell pool was depleted, resulting in compromised immune memory to previously encountered pathogens.

Thus, the link between measles infections and increased susceptibility to other infections and increased deaths from nonmeasles infectious diseases in the aftermath of measles has been revealed. This information adds new data to share with parents who consider refusing measles vaccination. The risks are far greater than getting measles.

Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He was asked to comment on the articles. Dr. Pichichero has no conflicts to declare.

As a result of reduced vaccination, after decades of decline, the number of worldwide cases of measles has increased by nearly 300% since 2018. Epidemiologic evidence has associated measles infections with increases in morbidity and mortality for as long as 5 years after the infection and suggests that, in the prevaccine era, measles virus may have been associated with up to 50% of all childhood deaths, mostly because of nonmeasles infections. Measles replication in immune cells has been hypothesized to impair immune memory, potentially causing what some scientists call “immunological amnesia.”A measles virus receptor, called CD150/ SLAMF1, is highly expressed on memory T, B, and plasma cells. Measles virus gains entry to these immune memory cells using that receptor and kills the cells.

The scientists stated that it could take months or years to return the immune repertoire back to baseline. During the rebuilding process, children would be at increased risk for infectious diseases they had previously experienced.

In a second outstanding paper, Petrova et al. in Science Immunology studied B cells before and after measles infection, and identified two immunologic consequences: The naive B-cell pool was depleted, leading to a return to immunologic immaturity, and the memory B-cell pool was depleted, resulting in compromised immune memory to previously encountered pathogens.

Thus, the link between measles infections and increased susceptibility to other infections and increased deaths from nonmeasles infectious diseases in the aftermath of measles has been revealed. This information adds new data to share with parents who consider refusing measles vaccination. The risks are far greater than getting measles.

Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He was asked to comment on the articles. Dr. Pichichero has no conflicts to declare.

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science.

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 the children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

The study did find increases in measles virus–specific antigens in children both after measles infection and MMR vaccination. However the authors did not detect any changes in total IgG, IgA, or IgM levels.

Dr. Mina and associates wrote.

They also noted that controls who received the MMR vaccine showed a marked increase in overall antibody repertoire.

In a separate investigation reported in Science Immunology, Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles to determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgVH-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B-cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IgVH-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IgVH-J genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IgVH genes, Dr. Petrova and associates reported.

The study by Mina et al. was supported by grants from various U.S., European, and Finnish foundations and national organizations. Some of the coauthors had relationships with biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, and three reported a patent holding related to technology used in the study. The study by Petrova et al. was funded by grants to the investigators from various Indonesian and German organizations and the Wellcome Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Mina M et al. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366:599-606; Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125.

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science.

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 the children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

The study did find increases in measles virus–specific antigens in children both after measles infection and MMR vaccination. However the authors did not detect any changes in total IgG, IgA, or IgM levels.

Dr. Mina and associates wrote.

They also noted that controls who received the MMR vaccine showed a marked increase in overall antibody repertoire.

In a separate investigation reported in Science Immunology, Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles to determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgVH-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B-cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IgVH-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IgVH-J genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IgVH genes, Dr. Petrova and associates reported.

The study by Mina et al. was supported by grants from various U.S., European, and Finnish foundations and national organizations. Some of the coauthors had relationships with biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, and three reported a patent holding related to technology used in the study. The study by Petrova et al. was funded by grants to the investigators from various Indonesian and German organizations and the Wellcome Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Mina M et al. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366:599-606; Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125.

FROM SCIENCE

Measles causes B-cell changes, leading to ‘immune amnesia’

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

FROM SCIENCE IMMUNOTHERAPY

Religious vaccination exemptions may be personal belief exemptions in disguise

and they appear to go up when personal belief exemptions go away, which might be caused by a replacement effect, researchers hypothesized in Pediatrics.

“Put differently, state-level religious exemption rates appear to be a function of personal belief exemption availability, decreasing significantly when states offer a personal belief exemption alternative,” the researchers explained.

Led by Joshua T.B. Williams, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the Denver Health Medical Center, the researchers sought to update state-level analyses of vaccination exemption rates by performing a cross-sectional, retrospective investigation of publicly available aggregated yearly vaccine reports for kindergartners from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They were specifically interested in the school years of 2011-2012 through 2017-2018 “to extend and provide meaningful comparisons to a previous study of exemption data” that had ended its study period in 2015-2016 (Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 Nov 15. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx244). The researchers adjusted for heterogeneous exemption processes by coding for “difficulty” of obtaining such exemptions in accordance with that previous study’s methods because studies have suggested that nonmedical exemption rates are lower in states with more difficult exemption policies. They also looked at how rates of religious exemptions changed in Vermont after the state eliminated personal, or philosophical, exemptions in 2016. The final analysis included 295 state-years from among the 45 states and the District of Columbia that all allow religious exemptions and the 15 states that permit personal belief exemptions.

The unadjusted analysis showed that the mean proportion of kindergartners with religious exemptions was lower where personal belief exemptions were available (0.41%; 95% confidence interval, 0.28%-0.53%) than they were where only religious exemptions were an option (1.63%; 95% CI, 1.30%-1.97%). In the adjusted analysis, states with both religious and personal belief exemptions were only a quarter as likely to have kindergartners with religious exemptions than those without personal belief exemptions (adjusted risk ratio, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.16-0.38). Furthermore, the proportion of kindergartners in Vermont with religious exemptions went from 0.5% in the years 2011-2012 through 2015-2016 when personal belief exemptions were still an option, to 3.7% in 2016-2017 through 2017-2018, after they went away.

One of the study’s limitations is that not all states used the same methods of data collection; however, the authors felt that, given about three-quarters of states included performed censuses with at least 80% of children counted, the effects on the study’s results should be minimal.

After discussing the role of religious exemptions and some of their history, as well as citing the seemingly paradoxical reported decline in religiosity and rise in religious exemptions, the researchers wrote in their conclusion that these “may be an increasingly problematic or outdated exemption category, and researchers and policy makers must work together to determine how best to balance a respect for religious liberty and the need to protect public health.”

SOURCE: Williams JTB et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2710.

and they appear to go up when personal belief exemptions go away, which might be caused by a replacement effect, researchers hypothesized in Pediatrics.

“Put differently, state-level religious exemption rates appear to be a function of personal belief exemption availability, decreasing significantly when states offer a personal belief exemption alternative,” the researchers explained.

Led by Joshua T.B. Williams, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the Denver Health Medical Center, the researchers sought to update state-level analyses of vaccination exemption rates by performing a cross-sectional, retrospective investigation of publicly available aggregated yearly vaccine reports for kindergartners from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They were specifically interested in the school years of 2011-2012 through 2017-2018 “to extend and provide meaningful comparisons to a previous study of exemption data” that had ended its study period in 2015-2016 (Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 Nov 15. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx244). The researchers adjusted for heterogeneous exemption processes by coding for “difficulty” of obtaining such exemptions in accordance with that previous study’s methods because studies have suggested that nonmedical exemption rates are lower in states with more difficult exemption policies. They also looked at how rates of religious exemptions changed in Vermont after the state eliminated personal, or philosophical, exemptions in 2016. The final analysis included 295 state-years from among the 45 states and the District of Columbia that all allow religious exemptions and the 15 states that permit personal belief exemptions.

The unadjusted analysis showed that the mean proportion of kindergartners with religious exemptions was lower where personal belief exemptions were available (0.41%; 95% confidence interval, 0.28%-0.53%) than they were where only religious exemptions were an option (1.63%; 95% CI, 1.30%-1.97%). In the adjusted analysis, states with both religious and personal belief exemptions were only a quarter as likely to have kindergartners with religious exemptions than those without personal belief exemptions (adjusted risk ratio, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.16-0.38). Furthermore, the proportion of kindergartners in Vermont with religious exemptions went from 0.5% in the years 2011-2012 through 2015-2016 when personal belief exemptions were still an option, to 3.7% in 2016-2017 through 2017-2018, after they went away.

One of the study’s limitations is that not all states used the same methods of data collection; however, the authors felt that, given about three-quarters of states included performed censuses with at least 80% of children counted, the effects on the study’s results should be minimal.

After discussing the role of religious exemptions and some of their history, as well as citing the seemingly paradoxical reported decline in religiosity and rise in religious exemptions, the researchers wrote in their conclusion that these “may be an increasingly problematic or outdated exemption category, and researchers and policy makers must work together to determine how best to balance a respect for religious liberty and the need to protect public health.”

SOURCE: Williams JTB et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2710.

and they appear to go up when personal belief exemptions go away, which might be caused by a replacement effect, researchers hypothesized in Pediatrics.

“Put differently, state-level religious exemption rates appear to be a function of personal belief exemption availability, decreasing significantly when states offer a personal belief exemption alternative,” the researchers explained.

Led by Joshua T.B. Williams, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the Denver Health Medical Center, the researchers sought to update state-level analyses of vaccination exemption rates by performing a cross-sectional, retrospective investigation of publicly available aggregated yearly vaccine reports for kindergartners from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They were specifically interested in the school years of 2011-2012 through 2017-2018 “to extend and provide meaningful comparisons to a previous study of exemption data” that had ended its study period in 2015-2016 (Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 Nov 15. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx244). The researchers adjusted for heterogeneous exemption processes by coding for “difficulty” of obtaining such exemptions in accordance with that previous study’s methods because studies have suggested that nonmedical exemption rates are lower in states with more difficult exemption policies. They also looked at how rates of religious exemptions changed in Vermont after the state eliminated personal, or philosophical, exemptions in 2016. The final analysis included 295 state-years from among the 45 states and the District of Columbia that all allow religious exemptions and the 15 states that permit personal belief exemptions.

The unadjusted analysis showed that the mean proportion of kindergartners with religious exemptions was lower where personal belief exemptions were available (0.41%; 95% confidence interval, 0.28%-0.53%) than they were where only religious exemptions were an option (1.63%; 95% CI, 1.30%-1.97%). In the adjusted analysis, states with both religious and personal belief exemptions were only a quarter as likely to have kindergartners with religious exemptions than those without personal belief exemptions (adjusted risk ratio, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.16-0.38). Furthermore, the proportion of kindergartners in Vermont with religious exemptions went from 0.5% in the years 2011-2012 through 2015-2016 when personal belief exemptions were still an option, to 3.7% in 2016-2017 through 2017-2018, after they went away.

One of the study’s limitations is that not all states used the same methods of data collection; however, the authors felt that, given about three-quarters of states included performed censuses with at least 80% of children counted, the effects on the study’s results should be minimal.

After discussing the role of religious exemptions and some of their history, as well as citing the seemingly paradoxical reported decline in religiosity and rise in religious exemptions, the researchers wrote in their conclusion that these “may be an increasingly problematic or outdated exemption category, and researchers and policy makers must work together to determine how best to balance a respect for religious liberty and the need to protect public health.”

SOURCE: Williams JTB et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2710.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Click for Credit: Long-term antibiotics & stroke, CHD; Postvaccination seizures; more

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Poor response to statins hikes risk of cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2MVHlDR

Expires April 17, 2020

2. Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VUJzaE

Expires April 19, 2020

3. Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2oT00Z9

Expires April 22, 2020

4. Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OUUVu5

Expires April 28, 2020

5. Knowledge gaps about long-term osteoporosis drug therapy benefits, risks remain large

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Msgqkb

Expires May 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Poor response to statins hikes risk of cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2MVHlDR

Expires April 17, 2020

2. Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VUJzaE

Expires April 19, 2020

3. Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2oT00Z9

Expires April 22, 2020

4. Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OUUVu5

Expires April 28, 2020

5. Knowledge gaps about long-term osteoporosis drug therapy benefits, risks remain large

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Msgqkb

Expires May 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Poor response to statins hikes risk of cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2MVHlDR

Expires April 17, 2020

2. Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VUJzaE

Expires April 19, 2020

3. Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2oT00Z9

Expires April 22, 2020

4. Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OUUVu5

Expires April 28, 2020

5. Knowledge gaps about long-term osteoporosis drug therapy benefits, risks remain large

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Msgqkb

Expires May 1, 2020

Flu vaccine cuts infection severity in kids and adults

WASHINGTON –

During recent U.S. flu seasons, children and adults who contracted influenza despite vaccination had significantly fewer severe infections and infection complications, compared with unimmunized people, according to two separate reports from CDC researchers presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

One of the reports tracked the impact of flu vaccine in children using data that the CDC collected at seven medical centers that participated in the agency’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network, which provided information on children aged 6 months to 17 years who were hospitalized for an acute respiratory illness, including more than 1,700 children during the 2016-2017 flu season and more than 1,900 during the 2017-2018 season. Roughly 10% of these children tested positive for influenza, and the subsequent analysis focused on these cases and compared incidence rates among children who had been vaccinated during the index season and those who had remained unvaccinated.

Combined data from both seasons showed that vaccinated children were 50% less likely to have been hospitalized for an acute influenza infection, compared with unvaccinated kids, a pattern consistently seen both in children aged 6 months to 8 years and in those aged 9-17 years. The pattern of vaccine effectiveness also held regardless of which flu strain caused the infections, reported Angela P. Campbell, MD, a CDC medical officer.

“We saw a nice benefit from vaccination, both in previously healthy children and in those with an underlying medical condition,” a finding that adds to existing evidence of vaccine effectiveness, Dr. Campbell said in a video interview. The results confirmed that flu vaccination does not just prevent infections but also cuts the rate of more severe infections that lead to hospitalization, she explained.

Another CDC study looked at data collected by the agency’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network from adults at least 18 years old who were hospitalized for a laboratory-confirmed influenza infection during five flu seasons, 2013-2014 through 2017-18. The data, which came from more than 250 acute-care hospitals in 13 states, included more than 43,000 people hospitalized for an identified influenza strain and with a known vaccination history who were not institutionalized and had not received any antiviral treatment.

After propensity-weighted adjustment to create better parity between the vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, the results showed that people 18-64 years old with vaccination had statistically significant decreases in mortality of a relative 36%, need for mechanical ventilation of 34%, pneumonia of 20%, and need for ICU admission of a relative 19%, as well as an 18% drop in average ICU length of stay, Shikha Garg, MD, said at the meeting. The propensity-weighted analysis of data from people at least 65 years old showed statistically significant relative reductions linked with vaccination: 46% reduction in the need for mechanical ventilation, 28% reduction in ICU admissions, and 9% reduction in hospitalized length of stay.

Further analysis of these outcomes by the strains that caused these influenza infections showed that the statistically significant benefits from vaccination were seen only in patients infected with an H1N1 strain. Statistically significant effects on these severe outcomes were not apparent among people infected with the H3N2 or B strains, said Dr. Garg, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC.

“All adults should receive an annual flu vaccination as it can improve outcomes among those who develop influenza despite vaccination,” she concluded.

Results from a third CDC study reported at the meeting examined the importance of two vaccine doses (administered at least 4 weeks apart) given to children aged 6 months to 8 years for the first season they receive flu vaccination, which is the immunization approach for flu recommended by the CDC. The findings from a total of more than 7,500 children immunized during the 2014-2018 seasons showed a clear increment in vaccine protection among kids who received two doses during their first season vaccinated, especially in children who were 2 years old or younger. In that age group, administration of two doses produced vaccine effectiveness of 53% versus a 23% vaccine effectiveness after a single vaccine dose, reported Jessie Chung, a CDC epidemiologist.

WASHINGTON –

During recent U.S. flu seasons, children and adults who contracted influenza despite vaccination had significantly fewer severe infections and infection complications, compared with unimmunized people, according to two separate reports from CDC researchers presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

One of the reports tracked the impact of flu vaccine in children using data that the CDC collected at seven medical centers that participated in the agency’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network, which provided information on children aged 6 months to 17 years who were hospitalized for an acute respiratory illness, including more than 1,700 children during the 2016-2017 flu season and more than 1,900 during the 2017-2018 season. Roughly 10% of these children tested positive for influenza, and the subsequent analysis focused on these cases and compared incidence rates among children who had been vaccinated during the index season and those who had remained unvaccinated.

Combined data from both seasons showed that vaccinated children were 50% less likely to have been hospitalized for an acute influenza infection, compared with unvaccinated kids, a pattern consistently seen both in children aged 6 months to 8 years and in those aged 9-17 years. The pattern of vaccine effectiveness also held regardless of which flu strain caused the infections, reported Angela P. Campbell, MD, a CDC medical officer.

“We saw a nice benefit from vaccination, both in previously healthy children and in those with an underlying medical condition,” a finding that adds to existing evidence of vaccine effectiveness, Dr. Campbell said in a video interview. The results confirmed that flu vaccination does not just prevent infections but also cuts the rate of more severe infections that lead to hospitalization, she explained.

Another CDC study looked at data collected by the agency’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network from adults at least 18 years old who were hospitalized for a laboratory-confirmed influenza infection during five flu seasons, 2013-2014 through 2017-18. The data, which came from more than 250 acute-care hospitals in 13 states, included more than 43,000 people hospitalized for an identified influenza strain and with a known vaccination history who were not institutionalized and had not received any antiviral treatment.

After propensity-weighted adjustment to create better parity between the vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, the results showed that people 18-64 years old with vaccination had statistically significant decreases in mortality of a relative 36%, need for mechanical ventilation of 34%, pneumonia of 20%, and need for ICU admission of a relative 19%, as well as an 18% drop in average ICU length of stay, Shikha Garg, MD, said at the meeting. The propensity-weighted analysis of data from people at least 65 years old showed statistically significant relative reductions linked with vaccination: 46% reduction in the need for mechanical ventilation, 28% reduction in ICU admissions, and 9% reduction in hospitalized length of stay.

Further analysis of these outcomes by the strains that caused these influenza infections showed that the statistically significant benefits from vaccination were seen only in patients infected with an H1N1 strain. Statistically significant effects on these severe outcomes were not apparent among people infected with the H3N2 or B strains, said Dr. Garg, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC.

“All adults should receive an annual flu vaccination as it can improve outcomes among those who develop influenza despite vaccination,” she concluded.

Results from a third CDC study reported at the meeting examined the importance of two vaccine doses (administered at least 4 weeks apart) given to children aged 6 months to 8 years for the first season they receive flu vaccination, which is the immunization approach for flu recommended by the CDC. The findings from a total of more than 7,500 children immunized during the 2014-2018 seasons showed a clear increment in vaccine protection among kids who received two doses during their first season vaccinated, especially in children who were 2 years old or younger. In that age group, administration of two doses produced vaccine effectiveness of 53% versus a 23% vaccine effectiveness after a single vaccine dose, reported Jessie Chung, a CDC epidemiologist.

WASHINGTON –

During recent U.S. flu seasons, children and adults who contracted influenza despite vaccination had significantly fewer severe infections and infection complications, compared with unimmunized people, according to two separate reports from CDC researchers presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

One of the reports tracked the impact of flu vaccine in children using data that the CDC collected at seven medical centers that participated in the agency’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network, which provided information on children aged 6 months to 17 years who were hospitalized for an acute respiratory illness, including more than 1,700 children during the 2016-2017 flu season and more than 1,900 during the 2017-2018 season. Roughly 10% of these children tested positive for influenza, and the subsequent analysis focused on these cases and compared incidence rates among children who had been vaccinated during the index season and those who had remained unvaccinated.

Combined data from both seasons showed that vaccinated children were 50% less likely to have been hospitalized for an acute influenza infection, compared with unvaccinated kids, a pattern consistently seen both in children aged 6 months to 8 years and in those aged 9-17 years. The pattern of vaccine effectiveness also held regardless of which flu strain caused the infections, reported Angela P. Campbell, MD, a CDC medical officer.

“We saw a nice benefit from vaccination, both in previously healthy children and in those with an underlying medical condition,” a finding that adds to existing evidence of vaccine effectiveness, Dr. Campbell said in a video interview. The results confirmed that flu vaccination does not just prevent infections but also cuts the rate of more severe infections that lead to hospitalization, she explained.

Another CDC study looked at data collected by the agency’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network from adults at least 18 years old who were hospitalized for a laboratory-confirmed influenza infection during five flu seasons, 2013-2014 through 2017-18. The data, which came from more than 250 acute-care hospitals in 13 states, included more than 43,000 people hospitalized for an identified influenza strain and with a known vaccination history who were not institutionalized and had not received any antiviral treatment.

After propensity-weighted adjustment to create better parity between the vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, the results showed that people 18-64 years old with vaccination had statistically significant decreases in mortality of a relative 36%, need for mechanical ventilation of 34%, pneumonia of 20%, and need for ICU admission of a relative 19%, as well as an 18% drop in average ICU length of stay, Shikha Garg, MD, said at the meeting. The propensity-weighted analysis of data from people at least 65 years old showed statistically significant relative reductions linked with vaccination: 46% reduction in the need for mechanical ventilation, 28% reduction in ICU admissions, and 9% reduction in hospitalized length of stay.

Further analysis of these outcomes by the strains that caused these influenza infections showed that the statistically significant benefits from vaccination were seen only in patients infected with an H1N1 strain. Statistically significant effects on these severe outcomes were not apparent among people infected with the H3N2 or B strains, said Dr. Garg, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC.

“All adults should receive an annual flu vaccination as it can improve outcomes among those who develop influenza despite vaccination,” she concluded.

Results from a third CDC study reported at the meeting examined the importance of two vaccine doses (administered at least 4 weeks apart) given to children aged 6 months to 8 years for the first season they receive flu vaccination, which is the immunization approach for flu recommended by the CDC. The findings from a total of more than 7,500 children immunized during the 2014-2018 seasons showed a clear increment in vaccine protection among kids who received two doses during their first season vaccinated, especially in children who were 2 years old or younger. In that age group, administration of two doses produced vaccine effectiveness of 53% versus a 23% vaccine effectiveness after a single vaccine dose, reported Jessie Chung, a CDC epidemiologist.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2019

Supporting elimination of nonmedical vaccine exemptions

Let’s suppose your first patient of the morning is a 2-month-old you have never seen before. The family arrives 10 minutes late because they are still getting the dressing-undressing-diaper change-car seat–adjusting thing worked out. Father is a computer programmer. Mother lists her occupation as nutrition counselor. The child is gaining. Breastfeeding seems to come naturally to the dyad.

As the visit draws to a close, you take the matter-of-fact approach and say, “The nurse will be in shortly with the vaccines do you have any questions.” Well ... it turns out the parents don’t feel comfortable with vaccines. They claim to understand the science and feel that vaccines make sense for some families. But they feel that for themselves, with a healthy lifestyle and God’s benevolence their son will be protected without having to introduce a host of foreign substances into his body.

What word best describes your reaction? Anger? Frustration? Disappointment (in our education system)? Maybe you’re angry at yourself for failing to make it clear in your office pamphlet and social media feeds that to protect your other patients, you no longer accept families who refuse immunizations for the common childhood diseases.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says it feels your pain, and its Annual Leadership Forum made eliminating nonmedical vaccine exemption laws its top priority in 2019. As part of its effort to help, the AAP Board of Directors was asked to advocate for the creation of a toolkit of strategies for Academy chapters facing the challenge of nonmedical exemptions. As an initial step to this process, three physicians in the department of pediatrics at the Denver Health Medical Center have begun interviewing religious leaders in hopes of developing “clergy-specific vaccine educational materials and deriv[ing] best practices for engaging them as vaccination advocates.” The investigators describe their plan and initial findings in Pediatrics (2019 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0933). Although they acknowledged that their efforts may not provide a quick solution to the nonmedical exemption problem, they hope that including more stakeholders and engendering trust will help future discussions.

Fourteen pages deeper into that issue of Pediatrics is the runner-up submission of this year’s Section on Pediatric Trainees essay competition titled “What I Learned From the Antivaccine Movement” (2019 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2384). Alana C. Ju, MD, describes the 2-hour ordeal she endured to testify at the California State Capitol in support of a state Senate bill aimed at tightening the regulations for vaccine medical exemptions. Totally unprepared for the “level of vitriol” aimed at her and other supporters of the bill, she was “accused of violating her duty as” a pediatrician because she was failing to protect children. The supporters were called “greedy, ignorant, and negligent.”

To her credit, Dr. Ju was able to step back from this assault and began looking at the faces of her accusers and learned that, “they too, felt strongly about children’s health.” She realized that “focusing on perceived ignorance is counterproductive.” She now hopes that by focusing on the shared goal of what is best for children, “we can all be better advocates.”

Both of these articles have a warm sort of kumbaya feel about them. It never is a bad idea to learn more about those with whom we disagree. But before huddling up too close to the campfire, we must realize that there is good evidence that sharing the scientific data with vaccine-hesitant parents doesn’t convert them into vaccine acceptors. In fact, it may strengthen their resolve to resist (Nyhan et al. “Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial,” Pediatrics. 2014 Apr;133[4] e835-42).

We are unlikely to convert many anti-vaxxers by sitting down together. Our target audience needs to be legislators and the majority of people who do vaccinate their children. These are the voters who will support legislation to eliminate nonmedical vaccine exemptions. To characterize anti-vaxxers as despicable ignorants is untrue and serves no purpose. We all do care about the health of children. However,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

*This article has been updated 1/22/2020.

Let’s suppose your first patient of the morning is a 2-month-old you have never seen before. The family arrives 10 minutes late because they are still getting the dressing-undressing-diaper change-car seat–adjusting thing worked out. Father is a computer programmer. Mother lists her occupation as nutrition counselor. The child is gaining. Breastfeeding seems to come naturally to the dyad.

As the visit draws to a close, you take the matter-of-fact approach and say, “The nurse will be in shortly with the vaccines do you have any questions.” Well ... it turns out the parents don’t feel comfortable with vaccines. They claim to understand the science and feel that vaccines make sense for some families. But they feel that for themselves, with a healthy lifestyle and God’s benevolence their son will be protected without having to introduce a host of foreign substances into his body.

What word best describes your reaction? Anger? Frustration? Disappointment (in our education system)? Maybe you’re angry at yourself for failing to make it clear in your office pamphlet and social media feeds that to protect your other patients, you no longer accept families who refuse immunizations for the common childhood diseases.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says it feels your pain, and its Annual Leadership Forum made eliminating nonmedical vaccine exemption laws its top priority in 2019. As part of its effort to help, the AAP Board of Directors was asked to advocate for the creation of a toolkit of strategies for Academy chapters facing the challenge of nonmedical exemptions. As an initial step to this process, three physicians in the department of pediatrics at the Denver Health Medical Center have begun interviewing religious leaders in hopes of developing “clergy-specific vaccine educational materials and deriv[ing] best practices for engaging them as vaccination advocates.” The investigators describe their plan and initial findings in Pediatrics (2019 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0933). Although they acknowledged that their efforts may not provide a quick solution to the nonmedical exemption problem, they hope that including more stakeholders and engendering trust will help future discussions.

Fourteen pages deeper into that issue of Pediatrics is the runner-up submission of this year’s Section on Pediatric Trainees essay competition titled “What I Learned From the Antivaccine Movement” (2019 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2384). Alana C. Ju, MD, describes the 2-hour ordeal she endured to testify at the California State Capitol in support of a state Senate bill aimed at tightening the regulations for vaccine medical exemptions. Totally unprepared for the “level of vitriol” aimed at her and other supporters of the bill, she was “accused of violating her duty as” a pediatrician because she was failing to protect children. The supporters were called “greedy, ignorant, and negligent.”

To her credit, Dr. Ju was able to step back from this assault and began looking at the faces of her accusers and learned that, “they too, felt strongly about children’s health.” She realized that “focusing on perceived ignorance is counterproductive.” She now hopes that by focusing on the shared goal of what is best for children, “we can all be better advocates.”

Both of these articles have a warm sort of kumbaya feel about them. It never is a bad idea to learn more about those with whom we disagree. But before huddling up too close to the campfire, we must realize that there is good evidence that sharing the scientific data with vaccine-hesitant parents doesn’t convert them into vaccine acceptors. In fact, it may strengthen their resolve to resist (Nyhan et al. “Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial,” Pediatrics. 2014 Apr;133[4] e835-42).

We are unlikely to convert many anti-vaxxers by sitting down together. Our target audience needs to be legislators and the majority of people who do vaccinate their children. These are the voters who will support legislation to eliminate nonmedical vaccine exemptions. To characterize anti-vaxxers as despicable ignorants is untrue and serves no purpose. We all do care about the health of children. However,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

*This article has been updated 1/22/2020.

Let’s suppose your first patient of the morning is a 2-month-old you have never seen before. The family arrives 10 minutes late because they are still getting the dressing-undressing-diaper change-car seat–adjusting thing worked out. Father is a computer programmer. Mother lists her occupation as nutrition counselor. The child is gaining. Breastfeeding seems to come naturally to the dyad.

As the visit draws to a close, you take the matter-of-fact approach and say, “The nurse will be in shortly with the vaccines do you have any questions.” Well ... it turns out the parents don’t feel comfortable with vaccines. They claim to understand the science and feel that vaccines make sense for some families. But they feel that for themselves, with a healthy lifestyle and God’s benevolence their son will be protected without having to introduce a host of foreign substances into his body.

What word best describes your reaction? Anger? Frustration? Disappointment (in our education system)? Maybe you’re angry at yourself for failing to make it clear in your office pamphlet and social media feeds that to protect your other patients, you no longer accept families who refuse immunizations for the common childhood diseases.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says it feels your pain, and its Annual Leadership Forum made eliminating nonmedical vaccine exemption laws its top priority in 2019. As part of its effort to help, the AAP Board of Directors was asked to advocate for the creation of a toolkit of strategies for Academy chapters facing the challenge of nonmedical exemptions. As an initial step to this process, three physicians in the department of pediatrics at the Denver Health Medical Center have begun interviewing religious leaders in hopes of developing “clergy-specific vaccine educational materials and deriv[ing] best practices for engaging them as vaccination advocates.” The investigators describe their plan and initial findings in Pediatrics (2019 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0933). Although they acknowledged that their efforts may not provide a quick solution to the nonmedical exemption problem, they hope that including more stakeholders and engendering trust will help future discussions.

Fourteen pages deeper into that issue of Pediatrics is the runner-up submission of this year’s Section on Pediatric Trainees essay competition titled “What I Learned From the Antivaccine Movement” (2019 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2384). Alana C. Ju, MD, describes the 2-hour ordeal she endured to testify at the California State Capitol in support of a state Senate bill aimed at tightening the regulations for vaccine medical exemptions. Totally unprepared for the “level of vitriol” aimed at her and other supporters of the bill, she was “accused of violating her duty as” a pediatrician because she was failing to protect children. The supporters were called “greedy, ignorant, and negligent.”

To her credit, Dr. Ju was able to step back from this assault and began looking at the faces of her accusers and learned that, “they too, felt strongly about children’s health.” She realized that “focusing on perceived ignorance is counterproductive.” She now hopes that by focusing on the shared goal of what is best for children, “we can all be better advocates.”

Both of these articles have a warm sort of kumbaya feel about them. It never is a bad idea to learn more about those with whom we disagree. But before huddling up too close to the campfire, we must realize that there is good evidence that sharing the scientific data with vaccine-hesitant parents doesn’t convert them into vaccine acceptors. In fact, it may strengthen their resolve to resist (Nyhan et al. “Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial,” Pediatrics. 2014 Apr;133[4] e835-42).

We are unlikely to convert many anti-vaxxers by sitting down together. Our target audience needs to be legislators and the majority of people who do vaccinate their children. These are the voters who will support legislation to eliminate nonmedical vaccine exemptions. To characterize anti-vaxxers as despicable ignorants is untrue and serves no purpose. We all do care about the health of children. However,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

*This article has been updated 1/22/2020.

ACIP approves child and adolescent vaccination schedule for 2020

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously to approve the child and adolescent immunization schedule for 2020.

by busy providers,” Candice Robinson, MD, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said at the CDC’s October meeting of ACIP. Updates reflect changes in language in the adult vaccination schedule, notably the change in the definition of “contraindication.” The updated wording in the Notes substitutes “not recommended or contraindicated” instead of the word “contraindicated” only.

Another notable change was the addition of information on adolescent vaccination of children who received the meningococcal ACWY vaccine before 10 years of age. For “children in whom boosters are not recommended due to an ongoing or increased risk of meningococcal disease” (such as a healthy child traveling to an endemic area), they should receive MenACWY according to the recommended adolescent schedule. But those children for whom boosters are recommended because of increased disease risk from conditions including complement deficiency, HIV, or asplenia should “follow the booster schedule for persons at increased risk.”

Other changes include restructuring of the notes for the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) in special situations. The schedule now uses a bulleted list to show that LAIV should not be used in the following circumstances:

- Having history of severe allergic reaction to a previous vaccine or vaccine component.

- Using aspirin or a salicylate-containing medication.

- Being aged 2-4 years with a history of asthma or wheezing.

- Having immunocompromised conditions.

- Having anatomic or functional asplenia.

- Having cochlear implants.

- Experiencing cerebrospinal fluid–oropharyngeal communication.

- Having immunocompromised close contacts or caregivers.

- Being pregnant.

- Having received flu antivirals within the previous 48 hours.

In addition, language on shared clinical decision-making was added to the notes on the meningococcal B vaccine for adolescents and young adults aged 18-23 years not at increased risk. Based on shared clinical decision making, the recommendation is a “two-dose series of Bexsero at least 1 month apart” or “two-dose series of Trumenba at least 6 months apart; if dose two is administered earlier than 6 months, administer a third dose at least 4 months after dose two.”

Several vaccines’ Notes sections, including hepatitis B and meningococcal disease, added links to detailed recommendations in the corresponding issues of the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, to allow clinicians easy access to additional information.

View the current Child & Adolescent Vaccination Schedule here.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously to approve the child and adolescent immunization schedule for 2020.

by busy providers,” Candice Robinson, MD, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said at the CDC’s October meeting of ACIP. Updates reflect changes in language in the adult vaccination schedule, notably the change in the definition of “contraindication.” The updated wording in the Notes substitutes “not recommended or contraindicated” instead of the word “contraindicated” only.

Another notable change was the addition of information on adolescent vaccination of children who received the meningococcal ACWY vaccine before 10 years of age. For “children in whom boosters are not recommended due to an ongoing or increased risk of meningococcal disease” (such as a healthy child traveling to an endemic area), they should receive MenACWY according to the recommended adolescent schedule. But those children for whom boosters are recommended because of increased disease risk from conditions including complement deficiency, HIV, or asplenia should “follow the booster schedule for persons at increased risk.”

Other changes include restructuring of the notes for the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) in special situations. The schedule now uses a bulleted list to show that LAIV should not be used in the following circumstances:

- Having history of severe allergic reaction to a previous vaccine or vaccine component.

- Using aspirin or a salicylate-containing medication.

- Being aged 2-4 years with a history of asthma or wheezing.

- Having immunocompromised conditions.

- Having anatomic or functional asplenia.

- Having cochlear implants.

- Experiencing cerebrospinal fluid–oropharyngeal communication.

- Having immunocompromised close contacts or caregivers.

- Being pregnant.

- Having received flu antivirals within the previous 48 hours.

In addition, language on shared clinical decision-making was added to the notes on the meningococcal B vaccine for adolescents and young adults aged 18-23 years not at increased risk. Based on shared clinical decision making, the recommendation is a “two-dose series of Bexsero at least 1 month apart” or “two-dose series of Trumenba at least 6 months apart; if dose two is administered earlier than 6 months, administer a third dose at least 4 months after dose two.”