User login

FDA approves Adacel for repeat Tdap vaccinations

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the expanded use of Adacel (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine Adsorbed) to include repeat vaccinations 8 years or more after the first vaccination in people aged 10-64 years.

The expanded indication was based on results of a randomized, controlled trial, published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, in which more than 1,300 adults aged 18-64 years received either Adacel or a Td (tetanus-diphtheria) vaccine 8-12 years after receiving a previous dose of Adacel.

Over the course of the study, no significant difference in adverse event incidence was observed between groups. Injection-site reaction was the most common adverse event during the study, occurring in 87.7% of those who received Adacel and 88.0% of those who received the Td vaccine. Other common adverse events associated with Adacel include headache, body ache or muscle weakness, tiredness, muscle aches, and general discomfort.

“While strong vaccination programs are in place for young adolescents, a single Tdap immunization does not offer lifetime protection against pertussis due to waning immunity. The licensure of Adacel as the first Tdap vaccine in the U.S. for repeat vaccination is an important step for eligible patients and offers flexibility for health care providers to help manage their immunization schedules,” said David P. Greenberg, MD, regional medical head North America at Sanofi Pasteur, in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Sanofi website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the expanded use of Adacel (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine Adsorbed) to include repeat vaccinations 8 years or more after the first vaccination in people aged 10-64 years.

The expanded indication was based on results of a randomized, controlled trial, published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, in which more than 1,300 adults aged 18-64 years received either Adacel or a Td (tetanus-diphtheria) vaccine 8-12 years after receiving a previous dose of Adacel.

Over the course of the study, no significant difference in adverse event incidence was observed between groups. Injection-site reaction was the most common adverse event during the study, occurring in 87.7% of those who received Adacel and 88.0% of those who received the Td vaccine. Other common adverse events associated with Adacel include headache, body ache or muscle weakness, tiredness, muscle aches, and general discomfort.

“While strong vaccination programs are in place for young adolescents, a single Tdap immunization does not offer lifetime protection against pertussis due to waning immunity. The licensure of Adacel as the first Tdap vaccine in the U.S. for repeat vaccination is an important step for eligible patients and offers flexibility for health care providers to help manage their immunization schedules,” said David P. Greenberg, MD, regional medical head North America at Sanofi Pasteur, in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Sanofi website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the expanded use of Adacel (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine Adsorbed) to include repeat vaccinations 8 years or more after the first vaccination in people aged 10-64 years.

The expanded indication was based on results of a randomized, controlled trial, published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, in which more than 1,300 adults aged 18-64 years received either Adacel or a Td (tetanus-diphtheria) vaccine 8-12 years after receiving a previous dose of Adacel.

Over the course of the study, no significant difference in adverse event incidence was observed between groups. Injection-site reaction was the most common adverse event during the study, occurring in 87.7% of those who received Adacel and 88.0% of those who received the Td vaccine. Other common adverse events associated with Adacel include headache, body ache or muscle weakness, tiredness, muscle aches, and general discomfort.

“While strong vaccination programs are in place for young adolescents, a single Tdap immunization does not offer lifetime protection against pertussis due to waning immunity. The licensure of Adacel as the first Tdap vaccine in the U.S. for repeat vaccination is an important step for eligible patients and offers flexibility for health care providers to help manage their immunization schedules,” said David P. Greenberg, MD, regional medical head North America at Sanofi Pasteur, in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Sanofi website.

Incidence of late-onset GBS cases are higher than early-onset disease

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Between 2006 and 2015, early-onset disease cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) declined, while the incidence of late-onset cases did not change.

Major finding: The rate of early-onset GBS declined from 0.37 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births and the rate of late-onset GBS cases remained at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births.

Study details: A population-based study of infants with early-onset disease and late-onset disease GBS from 10 different states in the Active Bacterial Core surveillance program between 2006 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

LAIV4 was less effective for children than IIV against influenza A/H1N1pdm09

The live attenuated influenza vaccine was less effective against the influenza A/H1N1pdm09 virus in children and adolescents across multiple influenza seasons between 2013 and 2016, compared with the inactivated influenza vaccine, according to research published in the journal Pediatrics.

Jessie R. Chung, MPH, from the influenza division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and her colleagues performed an analysis of five different studies where vaccine effectiveness (VE) was examined for quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine (LAIV4) and inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in children and adolescents aged 2-17 years from 42 states.

The analysis included data from the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (6,793 patients), a study from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (3,822 patients), the Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children (3,521 patients), Department of Defense Global, Laboratory-based, Influenza Surveillance Program (1,935 patients), and the Influenza Incidence Surveillance Project (1,102 patients) between the periods of 2013-2014 and 2015-2016. The researchers sourced current and previous season vaccination history from electronic medical records and immunization registries.

Of patients who were vaccinated across all seasons, there was 67% effectiveness against influenza A/H1N1pdm09 (95% confidence interval, 62%-72%) for those who received the IIV and 20% (95% CI, −6%-39%) for LAIV4. Among patients who received the LAIV4 vaccination, there was a significantly higher likelihood of developing influenza A/H1N1pdm09 (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.06-3.44) compared with patients who received the IIV vaccination.

With regard to other strains, there was similar effectiveness against influenza A/H3N2 and influenza B with LAIV4 and IIV vaccinations.

“In contrast to findings of reduced LAIV4 effectiveness against influenza A/H1N1pdm09 viruses, our results suggest a possible but nonsignificant benefit of LAIV4 over IIV against influenza B viruses, which has been described previously,” the investigators wrote.

Limitations of the study included having data only one season prior to enrollment and little available demographic information beyond age, gender, and geographic location.

The Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children was funded by MedImmune, a member of the AstraZeneca Group. Two of the researchers are employees of AstraZeneca. The other authors reported having no conflicts of interest. The U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network was supported by the CDC through cooperative agreements with the University of Michigan, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, and Baylor Scott & White Health. At the University of Pittsburgh, the project also was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Chung JR et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2094.

There are many explanations for the decline in effectiveness of the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4), but the data are complicated by conflicting information from studies outside the United States indicating “reasonable protection” against influenza A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, and influenza B, compared with the inactivated influenza virus (IIV), Pedro A. Piedra, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In 2016, the World Health Organization met to discuss LAIV effectiveness and highlighted factors such as methodological study differences, inadequate vaccine handling at distribution centers, intrinsic virological differences of the A/H1N1pdm09 virus, and increased preexisting population immunity in the United States since 2010 as potential explanations. During the transition from LAIV3 to LAIV4 for the 2013-2014 influenza season, viral interference may have also occurred when the influenza B strain was introduced into the vaccine, he added.

According to the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), viral growth properties of A/H1N1pdm09 has improved in LAIV4, and viral shedding also has improved for children between 2 years and 4 years of age. Although effectiveness numbers were not available for the ACIP recommendation, an interim analysis from Public Health England for the 2017-2018 influenza season found a vaccine effectiveness of 90.3% (95% confidence interval, 16.4%-98.9%).

“This early result is encouraging and supports the reintroduction of LAIV4 in the United States as an option for the control of seasonal influenza,” he said. “It also highlights the need for annual influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates and the importance of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network in providing updated information for ACIP recommendations.”

Dr. Piedra is from the departments of molecular virology and microbiology and pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He reports being a consultant for AstraZeneca, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck Sharp and Dohme, and he has received travel support to present at an influenza seminar supported by Seqirus. His comments are from an editorial accompanying the article by Chung and colleagues ( Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018- 3290 ).

There are many explanations for the decline in effectiveness of the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4), but the data are complicated by conflicting information from studies outside the United States indicating “reasonable protection” against influenza A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, and influenza B, compared with the inactivated influenza virus (IIV), Pedro A. Piedra, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In 2016, the World Health Organization met to discuss LAIV effectiveness and highlighted factors such as methodological study differences, inadequate vaccine handling at distribution centers, intrinsic virological differences of the A/H1N1pdm09 virus, and increased preexisting population immunity in the United States since 2010 as potential explanations. During the transition from LAIV3 to LAIV4 for the 2013-2014 influenza season, viral interference may have also occurred when the influenza B strain was introduced into the vaccine, he added.

According to the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), viral growth properties of A/H1N1pdm09 has improved in LAIV4, and viral shedding also has improved for children between 2 years and 4 years of age. Although effectiveness numbers were not available for the ACIP recommendation, an interim analysis from Public Health England for the 2017-2018 influenza season found a vaccine effectiveness of 90.3% (95% confidence interval, 16.4%-98.9%).

“This early result is encouraging and supports the reintroduction of LAIV4 in the United States as an option for the control of seasonal influenza,” he said. “It also highlights the need for annual influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates and the importance of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network in providing updated information for ACIP recommendations.”

Dr. Piedra is from the departments of molecular virology and microbiology and pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He reports being a consultant for AstraZeneca, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck Sharp and Dohme, and he has received travel support to present at an influenza seminar supported by Seqirus. His comments are from an editorial accompanying the article by Chung and colleagues ( Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018- 3290 ).

There are many explanations for the decline in effectiveness of the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4), but the data are complicated by conflicting information from studies outside the United States indicating “reasonable protection” against influenza A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, and influenza B, compared with the inactivated influenza virus (IIV), Pedro A. Piedra, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In 2016, the World Health Organization met to discuss LAIV effectiveness and highlighted factors such as methodological study differences, inadequate vaccine handling at distribution centers, intrinsic virological differences of the A/H1N1pdm09 virus, and increased preexisting population immunity in the United States since 2010 as potential explanations. During the transition from LAIV3 to LAIV4 for the 2013-2014 influenza season, viral interference may have also occurred when the influenza B strain was introduced into the vaccine, he added.

According to the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), viral growth properties of A/H1N1pdm09 has improved in LAIV4, and viral shedding also has improved for children between 2 years and 4 years of age. Although effectiveness numbers were not available for the ACIP recommendation, an interim analysis from Public Health England for the 2017-2018 influenza season found a vaccine effectiveness of 90.3% (95% confidence interval, 16.4%-98.9%).

“This early result is encouraging and supports the reintroduction of LAIV4 in the United States as an option for the control of seasonal influenza,” he said. “It also highlights the need for annual influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates and the importance of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network in providing updated information for ACIP recommendations.”

Dr. Piedra is from the departments of molecular virology and microbiology and pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He reports being a consultant for AstraZeneca, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck Sharp and Dohme, and he has received travel support to present at an influenza seminar supported by Seqirus. His comments are from an editorial accompanying the article by Chung and colleagues ( Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018- 3290 ).

The live attenuated influenza vaccine was less effective against the influenza A/H1N1pdm09 virus in children and adolescents across multiple influenza seasons between 2013 and 2016, compared with the inactivated influenza vaccine, according to research published in the journal Pediatrics.

Jessie R. Chung, MPH, from the influenza division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and her colleagues performed an analysis of five different studies where vaccine effectiveness (VE) was examined for quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine (LAIV4) and inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in children and adolescents aged 2-17 years from 42 states.

The analysis included data from the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (6,793 patients), a study from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (3,822 patients), the Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children (3,521 patients), Department of Defense Global, Laboratory-based, Influenza Surveillance Program (1,935 patients), and the Influenza Incidence Surveillance Project (1,102 patients) between the periods of 2013-2014 and 2015-2016. The researchers sourced current and previous season vaccination history from electronic medical records and immunization registries.

Of patients who were vaccinated across all seasons, there was 67% effectiveness against influenza A/H1N1pdm09 (95% confidence interval, 62%-72%) for those who received the IIV and 20% (95% CI, −6%-39%) for LAIV4. Among patients who received the LAIV4 vaccination, there was a significantly higher likelihood of developing influenza A/H1N1pdm09 (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.06-3.44) compared with patients who received the IIV vaccination.

With regard to other strains, there was similar effectiveness against influenza A/H3N2 and influenza B with LAIV4 and IIV vaccinations.

“In contrast to findings of reduced LAIV4 effectiveness against influenza A/H1N1pdm09 viruses, our results suggest a possible but nonsignificant benefit of LAIV4 over IIV against influenza B viruses, which has been described previously,” the investigators wrote.

Limitations of the study included having data only one season prior to enrollment and little available demographic information beyond age, gender, and geographic location.

The Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children was funded by MedImmune, a member of the AstraZeneca Group. Two of the researchers are employees of AstraZeneca. The other authors reported having no conflicts of interest. The U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network was supported by the CDC through cooperative agreements with the University of Michigan, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, and Baylor Scott & White Health. At the University of Pittsburgh, the project also was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Chung JR et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2094.

The live attenuated influenza vaccine was less effective against the influenza A/H1N1pdm09 virus in children and adolescents across multiple influenza seasons between 2013 and 2016, compared with the inactivated influenza vaccine, according to research published in the journal Pediatrics.

Jessie R. Chung, MPH, from the influenza division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and her colleagues performed an analysis of five different studies where vaccine effectiveness (VE) was examined for quadrivalent live attenuated vaccine (LAIV4) and inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in children and adolescents aged 2-17 years from 42 states.

The analysis included data from the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (6,793 patients), a study from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (3,822 patients), the Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children (3,521 patients), Department of Defense Global, Laboratory-based, Influenza Surveillance Program (1,935 patients), and the Influenza Incidence Surveillance Project (1,102 patients) between the periods of 2013-2014 and 2015-2016. The researchers sourced current and previous season vaccination history from electronic medical records and immunization registries.

Of patients who were vaccinated across all seasons, there was 67% effectiveness against influenza A/H1N1pdm09 (95% confidence interval, 62%-72%) for those who received the IIV and 20% (95% CI, −6%-39%) for LAIV4. Among patients who received the LAIV4 vaccination, there was a significantly higher likelihood of developing influenza A/H1N1pdm09 (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.06-3.44) compared with patients who received the IIV vaccination.

With regard to other strains, there was similar effectiveness against influenza A/H3N2 and influenza B with LAIV4 and IIV vaccinations.

“In contrast to findings of reduced LAIV4 effectiveness against influenza A/H1N1pdm09 viruses, our results suggest a possible but nonsignificant benefit of LAIV4 over IIV against influenza B viruses, which has been described previously,” the investigators wrote.

Limitations of the study included having data only one season prior to enrollment and little available demographic information beyond age, gender, and geographic location.

The Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children was funded by MedImmune, a member of the AstraZeneca Group. Two of the researchers are employees of AstraZeneca. The other authors reported having no conflicts of interest. The U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network was supported by the CDC through cooperative agreements with the University of Michigan, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, and Baylor Scott & White Health. At the University of Pittsburgh, the project also was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Chung JR et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2094.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4) was significantly less effective than was the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) for children against the influenza A/H1N1pdm09 virus across multiple flu seasons.

Major finding:

Study details: A combined analysis of five studies in the United States between the periods of 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 from the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

Disclosures: The Influenza Clinical Investigation for Children was funded by MedImmune, a member of the AstraZeneca Group. Two of the researchers are employees of AstraZeneca. The other authors reported having no conflicts of interest. The U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network was supported by the CDC through cooperative agreements with the University of Michigan, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, and Baylor Scott & White Health. At the University of Pittsburgh, the project also was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Chung JR et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2094.

Cerebral small vessel and cognitive impairment

Also today, antidepressants are tied to greater hip fracture incidence, a hospital readmission reduction program may be doing more harm than good, and the flu season rages on with 19 states showing high activity in the final week of 2018.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, antidepressants are tied to greater hip fracture incidence, a hospital readmission reduction program may be doing more harm than good, and the flu season rages on with 19 states showing high activity in the final week of 2018.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, antidepressants are tied to greater hip fracture incidence, a hospital readmission reduction program may be doing more harm than good, and the flu season rages on with 19 states showing high activity in the final week of 2018.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Aspirin and Omega-3 fatty acids fail

Also today, New data reveal that college students are at greater risk of meningococcal B infection, children who survive Hodgkin lymphoma face a massive increased risk for second cancers down the road, and the 2018/19 flu season shows high activity in nine states.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, New data reveal that college students are at greater risk of meningococcal B infection, children who survive Hodgkin lymphoma face a massive increased risk for second cancers down the road, and the 2018/19 flu season shows high activity in nine states.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, New data reveal that college students are at greater risk of meningococcal B infection, children who survive Hodgkin lymphoma face a massive increased risk for second cancers down the road, and the 2018/19 flu season shows high activity in nine states.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

2018-2019 flu season starts in earnest

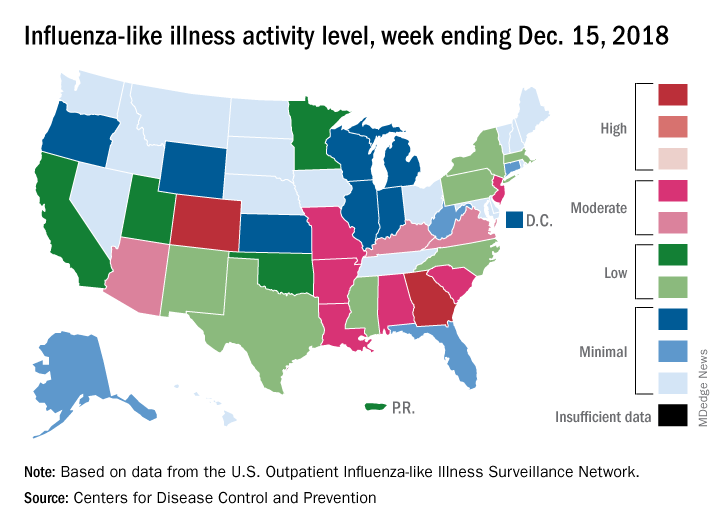

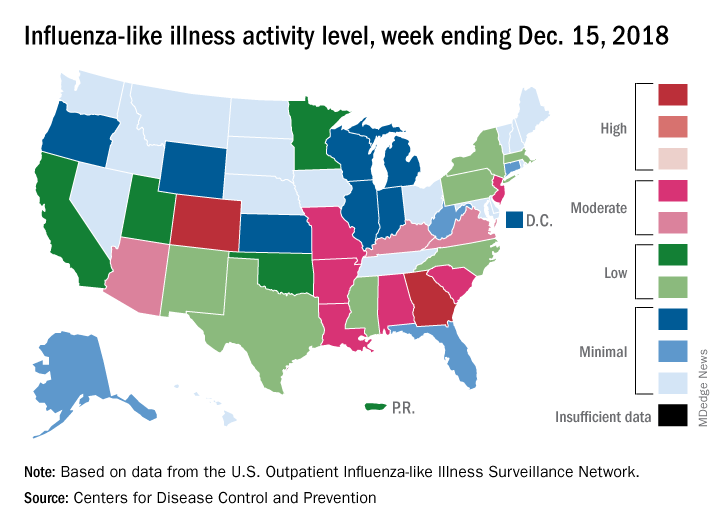

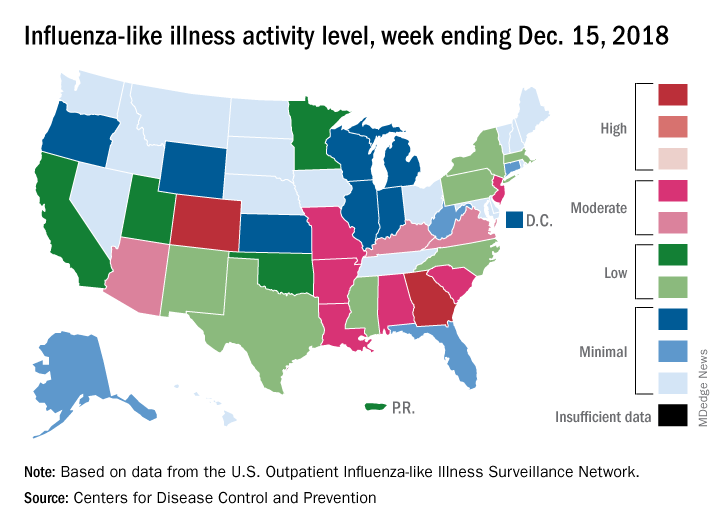

National flu activity moved solidly into above-average territory during the week ending Dec. 15, as Colorado and Georgia took the lead with the highest activity levels in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.7% for the week, which was up from 2.3% the previous week and above the national baseline of 2.2%, the CDC reported. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Colorado and Georgia both reported ILI activity of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, making them the only states in the “high” range (8-10). Nine states and New York City had activity levels in the “moderate” range (6-7), Puerto Rico and 11 states were in the “low” range (4-5), and 28 states and the District of Columbia were in the “minimal” range (1-3), the CDC said.

During the comparable period of last year’s high-severity flu season, which ultimately resulted in 900,000 flu-related hospitalizations and 80,000 deaths (185 pediatric), nine states were already at level 10. For the 2018-2019 season so far, there have been seven ILI-related pediatric deaths, CDC data show.

National flu activity moved solidly into above-average territory during the week ending Dec. 15, as Colorado and Georgia took the lead with the highest activity levels in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.7% for the week, which was up from 2.3% the previous week and above the national baseline of 2.2%, the CDC reported. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Colorado and Georgia both reported ILI activity of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, making them the only states in the “high” range (8-10). Nine states and New York City had activity levels in the “moderate” range (6-7), Puerto Rico and 11 states were in the “low” range (4-5), and 28 states and the District of Columbia were in the “minimal” range (1-3), the CDC said.

During the comparable period of last year’s high-severity flu season, which ultimately resulted in 900,000 flu-related hospitalizations and 80,000 deaths (185 pediatric), nine states were already at level 10. For the 2018-2019 season so far, there have been seven ILI-related pediatric deaths, CDC data show.

National flu activity moved solidly into above-average territory during the week ending Dec. 15, as Colorado and Georgia took the lead with the highest activity levels in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.7% for the week, which was up from 2.3% the previous week and above the national baseline of 2.2%, the CDC reported. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Colorado and Georgia both reported ILI activity of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, making them the only states in the “high” range (8-10). Nine states and New York City had activity levels in the “moderate” range (6-7), Puerto Rico and 11 states were in the “low” range (4-5), and 28 states and the District of Columbia were in the “minimal” range (1-3), the CDC said.

During the comparable period of last year’s high-severity flu season, which ultimately resulted in 900,000 flu-related hospitalizations and 80,000 deaths (185 pediatric), nine states were already at level 10. For the 2018-2019 season so far, there have been seven ILI-related pediatric deaths, CDC data show.

Pregnant women commonly refuse the influenza vaccine

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Although almost all ob.gyns. recommend the influenza and Tdap vaccines for pregnant women, both commonly are refused.

Major finding: A total of 62% of ob.gyns. reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine; 32% reported this for Tdap vaccine.

Study details: An email and mail survey sent to a national network of ob.gyns. between March and June 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Responding to pseudoscience

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

ERRATUM

The September 2018 Practice Alert, “CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season” contained an error (J Fam Pract. 2018. 67:550-553). On page 552, under “Available vaccine products,” the article listed “one standard dose IIV4 intradermal option.” This was incorrect. Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer of standard dose Intradermal IIV4, discontinued the production and supply of Fluzone Intradermal Quadrivalent vaccine at the conclusion of the 2017-2018 influenza season.

The September 2018 Practice Alert, “CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season” contained an error (J Fam Pract. 2018. 67:550-553). On page 552, under “Available vaccine products,” the article listed “one standard dose IIV4 intradermal option.” This was incorrect. Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer of standard dose Intradermal IIV4, discontinued the production and supply of Fluzone Intradermal Quadrivalent vaccine at the conclusion of the 2017-2018 influenza season.

The September 2018 Practice Alert, “CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season” contained an error (J Fam Pract. 2018. 67:550-553). On page 552, under “Available vaccine products,” the article listed “one standard dose IIV4 intradermal option.” This was incorrect. Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer of standard dose Intradermal IIV4, discontinued the production and supply of Fluzone Intradermal Quadrivalent vaccine at the conclusion of the 2017-2018 influenza season.

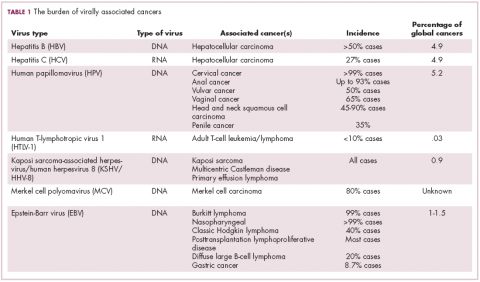

Immunotherapy may hold the key to defeating virally associated cancers

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

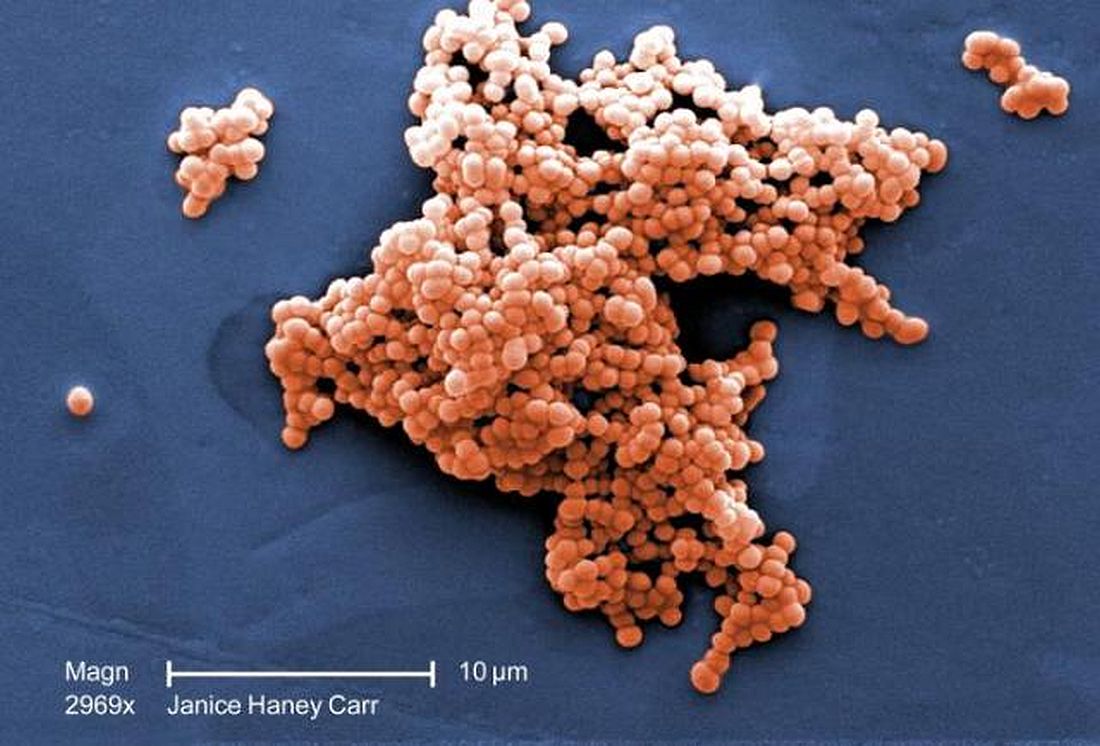

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

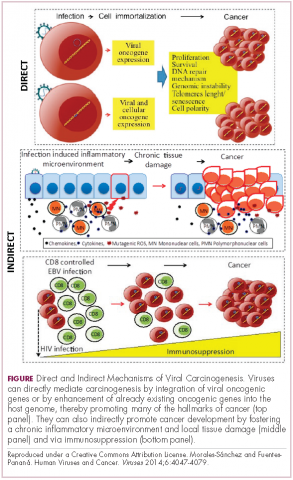

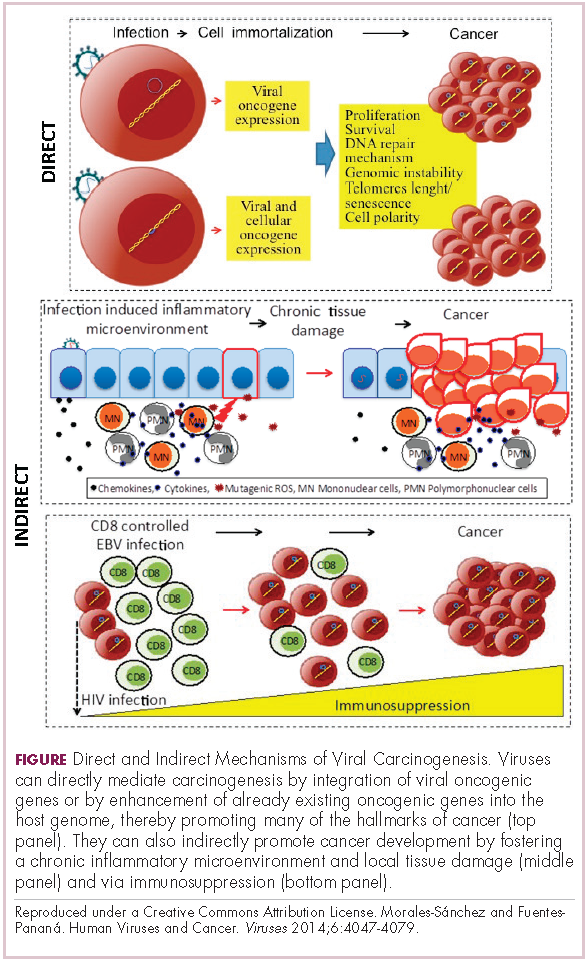

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

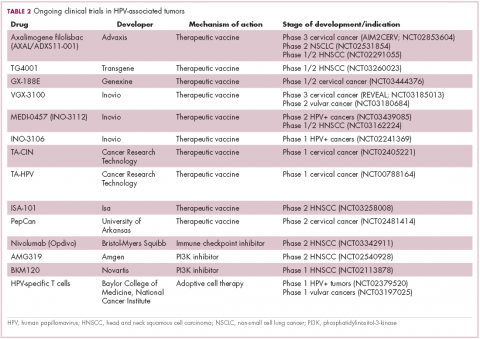

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers