User login

Aquatic Antagonists: Lionfish (Pterois volitans)

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

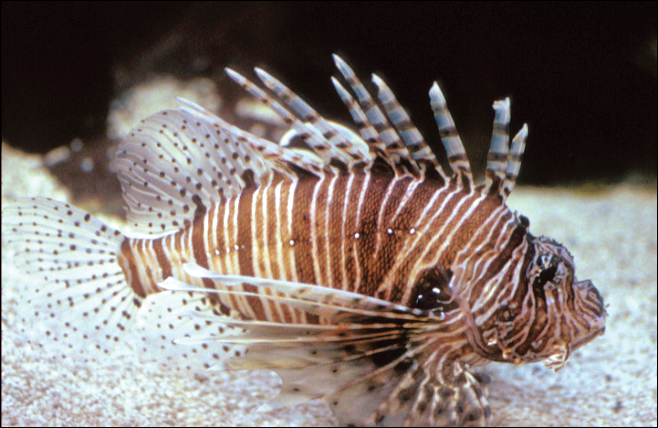

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management

Individuals with lionfish stings should immerse the affected area in hot but not scalding water. Those with more serious injuries should seek medical attention. Home remedies that are generally contraindicated include application of topical papain or meat tenderizer.10 Data on ice packs are mixed, but because the toxin is heat labile, the most effective initial step in treatment is immersion of the affected area in water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes.6 The hot water inactivates the heat-labile toxin, leading to near-complete symptomatic relief in 80% of cases and moderate relief in an additional 14%. Immersion time more than 90 minutes considerably increases the risk for burns. Children should always be monitored to prevent burns. If a patient has received a nerve block for analgesia, the wound should not be immersed in hot water to avoid burns to the skin. The wound should be meticulously cleaned with saline irrigation, and radiography or ultrasonography should be performed as deemed necessary to look for any retained foreign bodies.8 Patients may require parenteral or oral analgesia as well as careful follow-up to ensure proper healing.9 Systemic symptoms require supportive care. Venomous fish wounds typically are small and superficial. Empiric antibiotic therapy is not advised for superficial wounds but may be required for clinically infected wounds.8 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given as appropriate to all affected patients. It has been noted that blister fluid contains high concentrations of lionfish venom, and when present, it increases the likelihood of converting the injury from a grade II to grade III wound with tissue necrosis; therefore, blisters should be drained or excised to decrease the chances of subsequent tissue necrosis.11,12 If secondary infection such as cellulitis develops, antibiotics should be chosen to cover likely pathogens including common skin flora such as staphylococci and marine organisms such as Vibrio species. Wounds showing signs of infection should be cultured, with antibiotics adjusted according to sensitivities.5 Deeper wounds should be left open (unsutured) with a proper dressing to heal. Any wounds that involve vascular or joint structures require specialty management. Wounds involving joints may on occasion require surgical exploration and debridement.

Public Health Concerns

In an attempt to slow the growth of their population, human consumption of the fish has been encouraged. The lionfish toxin is inactivated by cooking, and the fish is considered a delicacy; however, a study in the Virgin Islands found that in areas with endemic ciguatera poisoning, 12% of lionfish carried amounts of the toxin above the level considered safe for consumption. This toxin is not inactivated by cooking or freezing and can lead to ciguatera fish poisoning for which there is no antidote and can be associated with prolonged neurotoxicity.13

Conclusion

As lionfish numbers continue to increase, physicians across multiple specialties and regions may see an increase in envenomation injuries. It is important that physicians are aware of how to recognize and treat lionfish stings, as prompt and comprehensive treatment provides benefit to the patient.

- Pterois volitans. Integrated Taxonomic Information System website. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=166883#null. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Morris JA Jr, Whitfield PE. Biology, Ecology, Control and Management of the Invasive Indopacific Lionfish: An Updated Integrated Assessment. Beaufort, NC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2009. http://aquaticcommons.org/2847/1/NCCOS_TM_99.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Pterois volitans/miles. US Geological Survey website. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=963. Revised April 18, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Diaz JH. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) pose public health threats [published online August 15, 2015]. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167:166-171.

- Diaz JH. Marine Scorpaenidae envenomation in travelers: epidemiology, management, and prevention. J Travel Med. 2015;22:251-258.

- Hobday D, Chadha P, Din AH, et al. Denaturing the lionfish. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic20.

- Sáenz A, Ortiz N, Lomonte B, et al. Comparison of biochemical and cytotoxic activities of extracts obtained from dorsal spines and caudal fin of adult and juvenile non-native Caribbean lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles). Toxicon. 2017;137:158-167.

- Schult RF, Acquisto NM, Stair CK, et al. A case of lionfish envenomation presenting to an inland emergency department [published online August 13, 2017]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:5893563.

- Resiere D, Cerland L, De Haro L, et al. Envenomation by the invasive Pterois volitans species (lionfish) in the French West Indies—a two-year prospective study in Martinique. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:313-318.

- Auerbach PS. Envenomation by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerback PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Auerbach PS, McKinney HE, Rees RE, et al. Analysis of vesicle fluid following the sting of the lionfish, Pterois volitans. Toxicon. 1987;25:1350-1353.

- Patel MR, Wells S. Lionfish envenomation of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:523-525.

- Robertson A, Garcia AC, Quintana HA, et al. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans): a potential human health threat for Ciguatera fish poisoning in tropical waters. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:88-97.

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management

Individuals with lionfish stings should immerse the affected area in hot but not scalding water. Those with more serious injuries should seek medical attention. Home remedies that are generally contraindicated include application of topical papain or meat tenderizer.10 Data on ice packs are mixed, but because the toxin is heat labile, the most effective initial step in treatment is immersion of the affected area in water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes.6 The hot water inactivates the heat-labile toxin, leading to near-complete symptomatic relief in 80% of cases and moderate relief in an additional 14%. Immersion time more than 90 minutes considerably increases the risk for burns. Children should always be monitored to prevent burns. If a patient has received a nerve block for analgesia, the wound should not be immersed in hot water to avoid burns to the skin. The wound should be meticulously cleaned with saline irrigation, and radiography or ultrasonography should be performed as deemed necessary to look for any retained foreign bodies.8 Patients may require parenteral or oral analgesia as well as careful follow-up to ensure proper healing.9 Systemic symptoms require supportive care. Venomous fish wounds typically are small and superficial. Empiric antibiotic therapy is not advised for superficial wounds but may be required for clinically infected wounds.8 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given as appropriate to all affected patients. It has been noted that blister fluid contains high concentrations of lionfish venom, and when present, it increases the likelihood of converting the injury from a grade II to grade III wound with tissue necrosis; therefore, blisters should be drained or excised to decrease the chances of subsequent tissue necrosis.11,12 If secondary infection such as cellulitis develops, antibiotics should be chosen to cover likely pathogens including common skin flora such as staphylococci and marine organisms such as Vibrio species. Wounds showing signs of infection should be cultured, with antibiotics adjusted according to sensitivities.5 Deeper wounds should be left open (unsutured) with a proper dressing to heal. Any wounds that involve vascular or joint structures require specialty management. Wounds involving joints may on occasion require surgical exploration and debridement.

Public Health Concerns

In an attempt to slow the growth of their population, human consumption of the fish has been encouraged. The lionfish toxin is inactivated by cooking, and the fish is considered a delicacy; however, a study in the Virgin Islands found that in areas with endemic ciguatera poisoning, 12% of lionfish carried amounts of the toxin above the level considered safe for consumption. This toxin is not inactivated by cooking or freezing and can lead to ciguatera fish poisoning for which there is no antidote and can be associated with prolonged neurotoxicity.13

Conclusion

As lionfish numbers continue to increase, physicians across multiple specialties and regions may see an increase in envenomation injuries. It is important that physicians are aware of how to recognize and treat lionfish stings, as prompt and comprehensive treatment provides benefit to the patient.

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management

Individuals with lionfish stings should immerse the affected area in hot but not scalding water. Those with more serious injuries should seek medical attention. Home remedies that are generally contraindicated include application of topical papain or meat tenderizer.10 Data on ice packs are mixed, but because the toxin is heat labile, the most effective initial step in treatment is immersion of the affected area in water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes.6 The hot water inactivates the heat-labile toxin, leading to near-complete symptomatic relief in 80% of cases and moderate relief in an additional 14%. Immersion time more than 90 minutes considerably increases the risk for burns. Children should always be monitored to prevent burns. If a patient has received a nerve block for analgesia, the wound should not be immersed in hot water to avoid burns to the skin. The wound should be meticulously cleaned with saline irrigation, and radiography or ultrasonography should be performed as deemed necessary to look for any retained foreign bodies.8 Patients may require parenteral or oral analgesia as well as careful follow-up to ensure proper healing.9 Systemic symptoms require supportive care. Venomous fish wounds typically are small and superficial. Empiric antibiotic therapy is not advised for superficial wounds but may be required for clinically infected wounds.8 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given as appropriate to all affected patients. It has been noted that blister fluid contains high concentrations of lionfish venom, and when present, it increases the likelihood of converting the injury from a grade II to grade III wound with tissue necrosis; therefore, blisters should be drained or excised to decrease the chances of subsequent tissue necrosis.11,12 If secondary infection such as cellulitis develops, antibiotics should be chosen to cover likely pathogens including common skin flora such as staphylococci and marine organisms such as Vibrio species. Wounds showing signs of infection should be cultured, with antibiotics adjusted according to sensitivities.5 Deeper wounds should be left open (unsutured) with a proper dressing to heal. Any wounds that involve vascular or joint structures require specialty management. Wounds involving joints may on occasion require surgical exploration and debridement.

Public Health Concerns

In an attempt to slow the growth of their population, human consumption of the fish has been encouraged. The lionfish toxin is inactivated by cooking, and the fish is considered a delicacy; however, a study in the Virgin Islands found that in areas with endemic ciguatera poisoning, 12% of lionfish carried amounts of the toxin above the level considered safe for consumption. This toxin is not inactivated by cooking or freezing and can lead to ciguatera fish poisoning for which there is no antidote and can be associated with prolonged neurotoxicity.13

Conclusion

As lionfish numbers continue to increase, physicians across multiple specialties and regions may see an increase in envenomation injuries. It is important that physicians are aware of how to recognize and treat lionfish stings, as prompt and comprehensive treatment provides benefit to the patient.

- Pterois volitans. Integrated Taxonomic Information System website. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=166883#null. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Morris JA Jr, Whitfield PE. Biology, Ecology, Control and Management of the Invasive Indopacific Lionfish: An Updated Integrated Assessment. Beaufort, NC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2009. http://aquaticcommons.org/2847/1/NCCOS_TM_99.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Pterois volitans/miles. US Geological Survey website. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=963. Revised April 18, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Diaz JH. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) pose public health threats [published online August 15, 2015]. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167:166-171.

- Diaz JH. Marine Scorpaenidae envenomation in travelers: epidemiology, management, and prevention. J Travel Med. 2015;22:251-258.

- Hobday D, Chadha P, Din AH, et al. Denaturing the lionfish. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic20.

- Sáenz A, Ortiz N, Lomonte B, et al. Comparison of biochemical and cytotoxic activities of extracts obtained from dorsal spines and caudal fin of adult and juvenile non-native Caribbean lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles). Toxicon. 2017;137:158-167.

- Schult RF, Acquisto NM, Stair CK, et al. A case of lionfish envenomation presenting to an inland emergency department [published online August 13, 2017]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:5893563.

- Resiere D, Cerland L, De Haro L, et al. Envenomation by the invasive Pterois volitans species (lionfish) in the French West Indies—a two-year prospective study in Martinique. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:313-318.

- Auerbach PS. Envenomation by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerback PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Auerbach PS, McKinney HE, Rees RE, et al. Analysis of vesicle fluid following the sting of the lionfish, Pterois volitans. Toxicon. 1987;25:1350-1353.

- Patel MR, Wells S. Lionfish envenomation of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:523-525.

- Robertson A, Garcia AC, Quintana HA, et al. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans): a potential human health threat for Ciguatera fish poisoning in tropical waters. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:88-97.

- Pterois volitans. Integrated Taxonomic Information System website. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=166883#null. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Morris JA Jr, Whitfield PE. Biology, Ecology, Control and Management of the Invasive Indopacific Lionfish: An Updated Integrated Assessment. Beaufort, NC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2009. http://aquaticcommons.org/2847/1/NCCOS_TM_99.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Pterois volitans/miles. US Geological Survey website. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=963. Revised April 18, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Diaz JH. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) pose public health threats [published online August 15, 2015]. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167:166-171.

- Diaz JH. Marine Scorpaenidae envenomation in travelers: epidemiology, management, and prevention. J Travel Med. 2015;22:251-258.

- Hobday D, Chadha P, Din AH, et al. Denaturing the lionfish. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic20.

- Sáenz A, Ortiz N, Lomonte B, et al. Comparison of biochemical and cytotoxic activities of extracts obtained from dorsal spines and caudal fin of adult and juvenile non-native Caribbean lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles). Toxicon. 2017;137:158-167.

- Schult RF, Acquisto NM, Stair CK, et al. A case of lionfish envenomation presenting to an inland emergency department [published online August 13, 2017]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:5893563.

- Resiere D, Cerland L, De Haro L, et al. Envenomation by the invasive Pterois volitans species (lionfish) in the French West Indies—a two-year prospective study in Martinique. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:313-318.

- Auerbach PS. Envenomation by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerback PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Auerbach PS, McKinney HE, Rees RE, et al. Analysis of vesicle fluid following the sting of the lionfish, Pterois volitans. Toxicon. 1987;25:1350-1353.

- Patel MR, Wells S. Lionfish envenomation of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:523-525.

- Robertson A, Garcia AC, Quintana HA, et al. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans): a potential human health threat for Ciguatera fish poisoning in tropical waters. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:88-97.

Practice Points

- Lionfish are now found all along the southeastern coast of the United States. Physicians may see an increase in envenomation injuries.

- Treat lionfish envenomation with immediate immersion in warm water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes to deactivate heat-labile toxin.

- Infected wounds should be treated with antibiotics for common skin flora and marine organisms such as Vibrio species.

Bone biopsy in suspected osteomyelitis: Culture and histology matter

Diabetic foot ulcers and infections can lead to osteomyelitis, a potentially devastating infection in the bone.

How much of a difference can osteomyelitis make to a patient’s prognosis? A 2014 commentary by Benjamin A. Lipsky, MD, a prominent expert in problems associated with diabetic patients’ feet who’s with the University of Washington, Seattle, hints at the potential toll: “Overall, about 20% of patients with a diabetic foot infection (and over 60% of those with severe infections) have underlying osteomyelitis, which dramatically increases the risk of lower-extremity amputation” (Diabetes Care. 2014 Mar;37[3]:593-5).

Diagnosis of osteomyelitis, which relies on a bone biopsy, is clearly important. But there’s a big gap in diagnostic findings depending on whether doctors request culture or histology results, according to a new study released at the 2018 scientific meeting of the American Diabetes Association (Diabetes. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.2337/db18-110-OR).

In an interview, lead author and podiatrist Peter A. Crisologo, DPM, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, explained the study findings and offered guidance for requesting bone biopsies in possible cases of osteomyelitis.

Q: What makes diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis unique?

A: In the foot, there’s not a lot of soft tissue between the outside world and your bone. If the wounds on the feet go deep enough, they can spread a bacterial infection to the bone. This changes how foot infections are treated.

If you have a skin infection, it requires 11-12 days of antibiotics. Things start ramping up once you start getting into the bone. You’re talking potential surgery and 6 weeks of antibiotics through IV treatments. This is why it’s really important that you get your diagnosis right.

A lot of people say “I’m going to do the safe thing” and treat a bone infection with an extended course of antibiotics.

That’s not necessarily safe. If you’re overdiagnosing – for example, you identify bacteria that’s just a contaminant – you could put a patient through 6 weeks of IV treatment along with the risks of a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter ) line infection, complications from IV placement, and complications from the antibiotic.

Also, acute kidney injury develops in at least a third of the patients who undergo 6 weeks of antibiotics. That’s not to mention the cost of the visits and the labs you have to draw. But we don’t want to underdiagnose either. If osteomyelitis is underdiagnosed and then not treated, the infection can smolder and continue to progress and worsen.

Q: Your study looks at the bone biopsy. How does it fit into care of osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot?

A: A bone biopsy is the standard for diagnosis under the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America/International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54[12]:e132-73 ).

But beyond that, nobody says anything. Everyone has an operational definition of how a bone biopsy is interpreted, and there’s a need for a consensus on how a bone biopsy can be used to diagnose osteomyelitis.

You’ll get different percentages of your patients diagnosed with osteomyelitis. For example, someone may say the biopsy is only positive if the histology is positive, while another says the histology doesn’t matter if the culture is positive.

Q: Your study looks at histology and culture analyses. What do these reveal?

A: A traditional culture helps you identify the bacteria, as well as guide your treatment when it’s tested against antibiotics.

A traditional histology allows the pathologist to look under a microscope for signs of osteomyelitis: Do they see the right inflammatory cells, white cells, lymphocytes, combinations of cells? Does this look like an acute or chronic osteomyelitis?

Q: Why might it be wise to combine culture and histology analyses?

A: If you have bacteria that’s difficult to culture via traditional methods, it may be a bacteria that doesn’t grow well or easily. If you combine culture with histology, pathologists can look and say, “Your culture was negative but we see these other signs, so we feel this is osteomyelitis.”

Q: Your study examined 35 consecutive patients aged at least 21 years who had moderate or severe infections bone infections in the foot linked with type 1 diabetes (n = 4) or type 2 diabetes (n = 31).

The samples were analyzed via culture, histology, and culture/histology examinations. You also performed genetic sequencing (quantitative polymerase chain reaction targeting 16S rRNA). How does this test fit in to bone biopsies in the clinic?

A: That’s a newer method and not a standard of care treatment for the diabetic foot. This analysis looks at DNA that’s present, bypassing the analysis of difficult-to-grow bacteria.

Q: What did you discover?

A: In this study, histology had the lowest incidence of positively detecting osteomyelitis. (45.7%). The level increases when a culture is taken (68.6% vs. histology; P = .02).

Then it goes up when DNA is used because it’s catching everything (82.9%, P = .001 vs. histology and P = .31 vs. culture).

[The study also found that adding histology to culture or to genetic sequencing did not change positive findings.]

Q: Does the study suggest one approach is better than the others?

A: This paper doesn’t provide enough evidence to use one method over another. The main purpose was to raise the concern that diagnosis can change dramatically depending on how the gold standard of bone biopsy is interpreted.

Q: What were the pros and cons of the genetic sequencing approach?

A: When we use this approach, our positive diagnostic rate significantly increases. But there are also downsides. We don’t know whether the bacteria we see is alive or dead. We just know it was there. So are the patients truly positive? That’s a question we can’t answer.

Genetic sequencing also doesn’t tell us about susceptibilities to antibiotics.

Q: What is the take-home message here for physicians who may order bone biopsies?

A: The thing to do is request both traditional culture and traditional histology.

As far as DNA sequencing, that not something I’d recommend as a standard of care.

Q: Can you comment on cost and insurance coverage for these approaches?

A: As far as I know, genetic sequencing is not covered as it is not standard of care in the diabetic foot and is used mainly for research at this time.

Pathology and culture are standard of care when evaluating for osteomyelitis and should be a covered service. However, a patient should call their insurance company first prior to having the procedure done to see whether it is covered.

Q: What’s next for research in this area?

A: From here, the next step is bigger numbers: Increase the study size and look at this again. Also, we may be able to identify susceptibilities by identifying resistance within the DNA.

Dr. Crisologo and two other study authors report no relevant disclosures. One study author reported various disclosures including research support, consulting, and service on speakers' bureaus.

Diabetic foot ulcers and infections can lead to osteomyelitis, a potentially devastating infection in the bone.

How much of a difference can osteomyelitis make to a patient’s prognosis? A 2014 commentary by Benjamin A. Lipsky, MD, a prominent expert in problems associated with diabetic patients’ feet who’s with the University of Washington, Seattle, hints at the potential toll: “Overall, about 20% of patients with a diabetic foot infection (and over 60% of those with severe infections) have underlying osteomyelitis, which dramatically increases the risk of lower-extremity amputation” (Diabetes Care. 2014 Mar;37[3]:593-5).

Diagnosis of osteomyelitis, which relies on a bone biopsy, is clearly important. But there’s a big gap in diagnostic findings depending on whether doctors request culture or histology results, according to a new study released at the 2018 scientific meeting of the American Diabetes Association (Diabetes. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.2337/db18-110-OR).

In an interview, lead author and podiatrist Peter A. Crisologo, DPM, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, explained the study findings and offered guidance for requesting bone biopsies in possible cases of osteomyelitis.

Q: What makes diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis unique?

A: In the foot, there’s not a lot of soft tissue between the outside world and your bone. If the wounds on the feet go deep enough, they can spread a bacterial infection to the bone. This changes how foot infections are treated.

If you have a skin infection, it requires 11-12 days of antibiotics. Things start ramping up once you start getting into the bone. You’re talking potential surgery and 6 weeks of antibiotics through IV treatments. This is why it’s really important that you get your diagnosis right.

A lot of people say “I’m going to do the safe thing” and treat a bone infection with an extended course of antibiotics.

That’s not necessarily safe. If you’re overdiagnosing – for example, you identify bacteria that’s just a contaminant – you could put a patient through 6 weeks of IV treatment along with the risks of a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter ) line infection, complications from IV placement, and complications from the antibiotic.

Also, acute kidney injury develops in at least a third of the patients who undergo 6 weeks of antibiotics. That’s not to mention the cost of the visits and the labs you have to draw. But we don’t want to underdiagnose either. If osteomyelitis is underdiagnosed and then not treated, the infection can smolder and continue to progress and worsen.

Q: Your study looks at the bone biopsy. How does it fit into care of osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot?

A: A bone biopsy is the standard for diagnosis under the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America/International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54[12]:e132-73 ).

But beyond that, nobody says anything. Everyone has an operational definition of how a bone biopsy is interpreted, and there’s a need for a consensus on how a bone biopsy can be used to diagnose osteomyelitis.

You’ll get different percentages of your patients diagnosed with osteomyelitis. For example, someone may say the biopsy is only positive if the histology is positive, while another says the histology doesn’t matter if the culture is positive.

Q: Your study looks at histology and culture analyses. What do these reveal?

A: A traditional culture helps you identify the bacteria, as well as guide your treatment when it’s tested against antibiotics.

A traditional histology allows the pathologist to look under a microscope for signs of osteomyelitis: Do they see the right inflammatory cells, white cells, lymphocytes, combinations of cells? Does this look like an acute or chronic osteomyelitis?

Q: Why might it be wise to combine culture and histology analyses?

A: If you have bacteria that’s difficult to culture via traditional methods, it may be a bacteria that doesn’t grow well or easily. If you combine culture with histology, pathologists can look and say, “Your culture was negative but we see these other signs, so we feel this is osteomyelitis.”

Q: Your study examined 35 consecutive patients aged at least 21 years who had moderate or severe infections bone infections in the foot linked with type 1 diabetes (n = 4) or type 2 diabetes (n = 31).

The samples were analyzed via culture, histology, and culture/histology examinations. You also performed genetic sequencing (quantitative polymerase chain reaction targeting 16S rRNA). How does this test fit in to bone biopsies in the clinic?

A: That’s a newer method and not a standard of care treatment for the diabetic foot. This analysis looks at DNA that’s present, bypassing the analysis of difficult-to-grow bacteria.

Q: What did you discover?

A: In this study, histology had the lowest incidence of positively detecting osteomyelitis. (45.7%). The level increases when a culture is taken (68.6% vs. histology; P = .02).

Then it goes up when DNA is used because it’s catching everything (82.9%, P = .001 vs. histology and P = .31 vs. culture).

[The study also found that adding histology to culture or to genetic sequencing did not change positive findings.]

Q: Does the study suggest one approach is better than the others?

A: This paper doesn’t provide enough evidence to use one method over another. The main purpose was to raise the concern that diagnosis can change dramatically depending on how the gold standard of bone biopsy is interpreted.

Q: What were the pros and cons of the genetic sequencing approach?

A: When we use this approach, our positive diagnostic rate significantly increases. But there are also downsides. We don’t know whether the bacteria we see is alive or dead. We just know it was there. So are the patients truly positive? That’s a question we can’t answer.

Genetic sequencing also doesn’t tell us about susceptibilities to antibiotics.

Q: What is the take-home message here for physicians who may order bone biopsies?

A: The thing to do is request both traditional culture and traditional histology.

As far as DNA sequencing, that not something I’d recommend as a standard of care.

Q: Can you comment on cost and insurance coverage for these approaches?

A: As far as I know, genetic sequencing is not covered as it is not standard of care in the diabetic foot and is used mainly for research at this time.

Pathology and culture are standard of care when evaluating for osteomyelitis and should be a covered service. However, a patient should call their insurance company first prior to having the procedure done to see whether it is covered.

Q: What’s next for research in this area?

A: From here, the next step is bigger numbers: Increase the study size and look at this again. Also, we may be able to identify susceptibilities by identifying resistance within the DNA.

Dr. Crisologo and two other study authors report no relevant disclosures. One study author reported various disclosures including research support, consulting, and service on speakers' bureaus.

Diabetic foot ulcers and infections can lead to osteomyelitis, a potentially devastating infection in the bone.

How much of a difference can osteomyelitis make to a patient’s prognosis? A 2014 commentary by Benjamin A. Lipsky, MD, a prominent expert in problems associated with diabetic patients’ feet who’s with the University of Washington, Seattle, hints at the potential toll: “Overall, about 20% of patients with a diabetic foot infection (and over 60% of those with severe infections) have underlying osteomyelitis, which dramatically increases the risk of lower-extremity amputation” (Diabetes Care. 2014 Mar;37[3]:593-5).

Diagnosis of osteomyelitis, which relies on a bone biopsy, is clearly important. But there’s a big gap in diagnostic findings depending on whether doctors request culture or histology results, according to a new study released at the 2018 scientific meeting of the American Diabetes Association (Diabetes. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.2337/db18-110-OR).

In an interview, lead author and podiatrist Peter A. Crisologo, DPM, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, explained the study findings and offered guidance for requesting bone biopsies in possible cases of osteomyelitis.

Q: What makes diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis unique?

A: In the foot, there’s not a lot of soft tissue between the outside world and your bone. If the wounds on the feet go deep enough, they can spread a bacterial infection to the bone. This changes how foot infections are treated.

If you have a skin infection, it requires 11-12 days of antibiotics. Things start ramping up once you start getting into the bone. You’re talking potential surgery and 6 weeks of antibiotics through IV treatments. This is why it’s really important that you get your diagnosis right.

A lot of people say “I’m going to do the safe thing” and treat a bone infection with an extended course of antibiotics.

That’s not necessarily safe. If you’re overdiagnosing – for example, you identify bacteria that’s just a contaminant – you could put a patient through 6 weeks of IV treatment along with the risks of a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter ) line infection, complications from IV placement, and complications from the antibiotic.

Also, acute kidney injury develops in at least a third of the patients who undergo 6 weeks of antibiotics. That’s not to mention the cost of the visits and the labs you have to draw. But we don’t want to underdiagnose either. If osteomyelitis is underdiagnosed and then not treated, the infection can smolder and continue to progress and worsen.

Q: Your study looks at the bone biopsy. How does it fit into care of osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot?

A: A bone biopsy is the standard for diagnosis under the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America/International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54[12]:e132-73 ).

But beyond that, nobody says anything. Everyone has an operational definition of how a bone biopsy is interpreted, and there’s a need for a consensus on how a bone biopsy can be used to diagnose osteomyelitis.

You’ll get different percentages of your patients diagnosed with osteomyelitis. For example, someone may say the biopsy is only positive if the histology is positive, while another says the histology doesn’t matter if the culture is positive.

Q: Your study looks at histology and culture analyses. What do these reveal?

A: A traditional culture helps you identify the bacteria, as well as guide your treatment when it’s tested against antibiotics.

A traditional histology allows the pathologist to look under a microscope for signs of osteomyelitis: Do they see the right inflammatory cells, white cells, lymphocytes, combinations of cells? Does this look like an acute or chronic osteomyelitis?

Q: Why might it be wise to combine culture and histology analyses?

A: If you have bacteria that’s difficult to culture via traditional methods, it may be a bacteria that doesn’t grow well or easily. If you combine culture with histology, pathologists can look and say, “Your culture was negative but we see these other signs, so we feel this is osteomyelitis.”

Q: Your study examined 35 consecutive patients aged at least 21 years who had moderate or severe infections bone infections in the foot linked with type 1 diabetes (n = 4) or type 2 diabetes (n = 31).

The samples were analyzed via culture, histology, and culture/histology examinations. You also performed genetic sequencing (quantitative polymerase chain reaction targeting 16S rRNA). How does this test fit in to bone biopsies in the clinic?

A: That’s a newer method and not a standard of care treatment for the diabetic foot. This analysis looks at DNA that’s present, bypassing the analysis of difficult-to-grow bacteria.

Q: What did you discover?

A: In this study, histology had the lowest incidence of positively detecting osteomyelitis. (45.7%). The level increases when a culture is taken (68.6% vs. histology; P = .02).

Then it goes up when DNA is used because it’s catching everything (82.9%, P = .001 vs. histology and P = .31 vs. culture).

[The study also found that adding histology to culture or to genetic sequencing did not change positive findings.]

Q: Does the study suggest one approach is better than the others?

A: This paper doesn’t provide enough evidence to use one method over another. The main purpose was to raise the concern that diagnosis can change dramatically depending on how the gold standard of bone biopsy is interpreted.

Q: What were the pros and cons of the genetic sequencing approach?

A: When we use this approach, our positive diagnostic rate significantly increases. But there are also downsides. We don’t know whether the bacteria we see is alive or dead. We just know it was there. So are the patients truly positive? That’s a question we can’t answer.

Genetic sequencing also doesn’t tell us about susceptibilities to antibiotics.

Q: What is the take-home message here for physicians who may order bone biopsies?

A: The thing to do is request both traditional culture and traditional histology.

As far as DNA sequencing, that not something I’d recommend as a standard of care.

Q: Can you comment on cost and insurance coverage for these approaches?

A: As far as I know, genetic sequencing is not covered as it is not standard of care in the diabetic foot and is used mainly for research at this time.

Pathology and culture are standard of care when evaluating for osteomyelitis and should be a covered service. However, a patient should call their insurance company first prior to having the procedure done to see whether it is covered.

Q: What’s next for research in this area?

A: From here, the next step is bigger numbers: Increase the study size and look at this again. Also, we may be able to identify susceptibilities by identifying resistance within the DNA.

Dr. Crisologo and two other study authors report no relevant disclosures. One study author reported various disclosures including research support, consulting, and service on speakers' bureaus.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ADA 2018

Study offers snapshot of esophageal strictures in EB patients

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – and direct visualization of these strictures is the preferred method of diagnosis. Those are key findings from a multicenter study that lead author Elena Pope, MD, discussed at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

According to Dr. Pope, who heads the section of dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, an estimated 10%-17% of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) patients experience strictures, with an overrepresentation in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype in up to 80% of cases. The risk increases with age. “What remains unknown is the best short- and long-term intervention to manage the strictures and predictors/associations for stricture-free episodes,” Dr. Pope said. “The objectives of the current study were to determine the prevalence and predisposing factors for strictures in EB, management options, patient outcomes, and predictors for recurrences and stricture-free intervals.”

She and her associates at seven centers worldwide collected data on 125 EB patients who experienced at least one episode of esophageal stricture. Data was analyzed descriptively and with ANOVA regression analysis for associations/predictors for recurrences/episode-free intervals.

The researchers evaluated 497 stricture events in the 125 patients. A slight female predominance was noted (53%), and the mean age of the first episode was 12.7 years, “which is a little bit older” than the age found in previously published data, Dr. Pope said. As expected, dystrophic EB patients made up most of the sample (98.4%); of these 123 patients, recessive dystrophic EB severe generalized subtype – approaching 50% – was the most common, followed by the recessive dystrophic EB severe intermediate subtype (almost 21%), the dominant dystrophic EB generalized subtype (7%), and other types of dystrophic EB (almost 26%).

The median body mass index percentile for age was 6.3, “so these were patients who were severely malnourished, probably as a result of their strictures as well as their underlying disease,” Dr. Pope said.

As expected, dysphagia was a presenting symptom in most patients (85.5%), while 29.8% presented with inability to swallow solids. The preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%), and less commonly with barium swallow (22.3%) or with clinical symptoms alone (0.1%). The mean number of strictures was 1.69; 76.7% were located in the cervical area, 56.7% were located in the thoracic area, and 9.7% were located in the abdominal area. Most patients (76%) had lesions that were 1 cm or longer in size.

Fluoroscopy guidance was the most common method of dilatation (in 45.2% of cases), followed by retrograde endoscopy was (33%), antegrade endoscopy (19.1%), and bougienage (0.1%). General anesthesia was used in most cases (87.6%), and corticosteroids were used around the dilatation in 90.4% of patients. The mean duration of medication use was about 5 days.

As for outcomes after dilatation, 92.2% of strictures completely resolved, 3.8% were partially resolved, 3.9% were not resolved, and 2.7% had complications. The median interval between dilatations was 7 months. Fluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation was associated with the longest esophageal stricture-free duration (mean of 13.83 months vs. 8.75 months; P less than .001), followed by retrograde endoscopy (mean of 13.10 months vs. 7.85 months; P less than .001), and antegrade endoscopy (mean of 7.63 months vs. 11.46 months; P = .024). “I think this is interesting,” said Dr. Pope, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “I think the difference occurs because if you use the endoscopy, which a rigid tube, you can potentially cause more damage, and more long-term scarring.”

Another predictor of esophageal stricture-free episodes was systemic corticosteroid use (a mean of 25.28 months vs. 10.24 months; P less than .001) around the time of the dilatation procedure. “By using systemic steroids, you’re actually decreasing some of the inflammation associated with the trauma of the procedure decreasing the chances of strictures formation,” she said.

Dr. Pope recommended that future studies evaluate the benefit of periprocedural medical interventions on increasing the intervals between esophageal stricture occurrences.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – and direct visualization of these strictures is the preferred method of diagnosis. Those are key findings from a multicenter study that lead author Elena Pope, MD, discussed at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

According to Dr. Pope, who heads the section of dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, an estimated 10%-17% of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) patients experience strictures, with an overrepresentation in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype in up to 80% of cases. The risk increases with age. “What remains unknown is the best short- and long-term intervention to manage the strictures and predictors/associations for stricture-free episodes,” Dr. Pope said. “The objectives of the current study were to determine the prevalence and predisposing factors for strictures in EB, management options, patient outcomes, and predictors for recurrences and stricture-free intervals.”

She and her associates at seven centers worldwide collected data on 125 EB patients who experienced at least one episode of esophageal stricture. Data was analyzed descriptively and with ANOVA regression analysis for associations/predictors for recurrences/episode-free intervals.

The researchers evaluated 497 stricture events in the 125 patients. A slight female predominance was noted (53%), and the mean age of the first episode was 12.7 years, “which is a little bit older” than the age found in previously published data, Dr. Pope said. As expected, dystrophic EB patients made up most of the sample (98.4%); of these 123 patients, recessive dystrophic EB severe generalized subtype – approaching 50% – was the most common, followed by the recessive dystrophic EB severe intermediate subtype (almost 21%), the dominant dystrophic EB generalized subtype (7%), and other types of dystrophic EB (almost 26%).

The median body mass index percentile for age was 6.3, “so these were patients who were severely malnourished, probably as a result of their strictures as well as their underlying disease,” Dr. Pope said.

As expected, dysphagia was a presenting symptom in most patients (85.5%), while 29.8% presented with inability to swallow solids. The preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%), and less commonly with barium swallow (22.3%) or with clinical symptoms alone (0.1%). The mean number of strictures was 1.69; 76.7% were located in the cervical area, 56.7% were located in the thoracic area, and 9.7% were located in the abdominal area. Most patients (76%) had lesions that were 1 cm or longer in size.

Fluoroscopy guidance was the most common method of dilatation (in 45.2% of cases), followed by retrograde endoscopy was (33%), antegrade endoscopy (19.1%), and bougienage (0.1%). General anesthesia was used in most cases (87.6%), and corticosteroids were used around the dilatation in 90.4% of patients. The mean duration of medication use was about 5 days.

As for outcomes after dilatation, 92.2% of strictures completely resolved, 3.8% were partially resolved, 3.9% were not resolved, and 2.7% had complications. The median interval between dilatations was 7 months. Fluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation was associated with the longest esophageal stricture-free duration (mean of 13.83 months vs. 8.75 months; P less than .001), followed by retrograde endoscopy (mean of 13.10 months vs. 7.85 months; P less than .001), and antegrade endoscopy (mean of 7.63 months vs. 11.46 months; P = .024). “I think this is interesting,” said Dr. Pope, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “I think the difference occurs because if you use the endoscopy, which a rigid tube, you can potentially cause more damage, and more long-term scarring.”

Another predictor of esophageal stricture-free episodes was systemic corticosteroid use (a mean of 25.28 months vs. 10.24 months; P less than .001) around the time of the dilatation procedure. “By using systemic steroids, you’re actually decreasing some of the inflammation associated with the trauma of the procedure decreasing the chances of strictures formation,” she said.

Dr. Pope recommended that future studies evaluate the benefit of periprocedural medical interventions on increasing the intervals between esophageal stricture occurrences.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – and direct visualization of these strictures is the preferred method of diagnosis. Those are key findings from a multicenter study that lead author Elena Pope, MD, discussed at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

According to Dr. Pope, who heads the section of dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, an estimated 10%-17% of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) patients experience strictures, with an overrepresentation in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype in up to 80% of cases. The risk increases with age. “What remains unknown is the best short- and long-term intervention to manage the strictures and predictors/associations for stricture-free episodes,” Dr. Pope said. “The objectives of the current study were to determine the prevalence and predisposing factors for strictures in EB, management options, patient outcomes, and predictors for recurrences and stricture-free intervals.”

She and her associates at seven centers worldwide collected data on 125 EB patients who experienced at least one episode of esophageal stricture. Data was analyzed descriptively and with ANOVA regression analysis for associations/predictors for recurrences/episode-free intervals.

The researchers evaluated 497 stricture events in the 125 patients. A slight female predominance was noted (53%), and the mean age of the first episode was 12.7 years, “which is a little bit older” than the age found in previously published data, Dr. Pope said. As expected, dystrophic EB patients made up most of the sample (98.4%); of these 123 patients, recessive dystrophic EB severe generalized subtype – approaching 50% – was the most common, followed by the recessive dystrophic EB severe intermediate subtype (almost 21%), the dominant dystrophic EB generalized subtype (7%), and other types of dystrophic EB (almost 26%).

The median body mass index percentile for age was 6.3, “so these were patients who were severely malnourished, probably as a result of their strictures as well as their underlying disease,” Dr. Pope said.

As expected, dysphagia was a presenting symptom in most patients (85.5%), while 29.8% presented with inability to swallow solids. The preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%), and less commonly with barium swallow (22.3%) or with clinical symptoms alone (0.1%). The mean number of strictures was 1.69; 76.7% were located in the cervical area, 56.7% were located in the thoracic area, and 9.7% were located in the abdominal area. Most patients (76%) had lesions that were 1 cm or longer in size.

Fluoroscopy guidance was the most common method of dilatation (in 45.2% of cases), followed by retrograde endoscopy was (33%), antegrade endoscopy (19.1%), and bougienage (0.1%). General anesthesia was used in most cases (87.6%), and corticosteroids were used around the dilatation in 90.4% of patients. The mean duration of medication use was about 5 days.

As for outcomes after dilatation, 92.2% of strictures completely resolved, 3.8% were partially resolved, 3.9% were not resolved, and 2.7% had complications. The median interval between dilatations was 7 months. Fluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation was associated with the longest esophageal stricture-free duration (mean of 13.83 months vs. 8.75 months; P less than .001), followed by retrograde endoscopy (mean of 13.10 months vs. 7.85 months; P less than .001), and antegrade endoscopy (mean of 7.63 months vs. 11.46 months; P = .024). “I think this is interesting,” said Dr. Pope, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “I think the difference occurs because if you use the endoscopy, which a rigid tube, you can potentially cause more damage, and more long-term scarring.”

Another predictor of esophageal stricture-free episodes was systemic corticosteroid use (a mean of 25.28 months vs. 10.24 months; P less than .001) around the time of the dilatation procedure. “By using systemic steroids, you’re actually decreasing some of the inflammation associated with the trauma of the procedure decreasing the chances of strictures formation,” she said.

Dr. Pope recommended that future studies evaluate the benefit of periprocedural medical interventions on increasing the intervals between esophageal stricture occurrences.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. She reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Esophageal strictures are common complications of patients with severe types of epidermolysis bullosa.

Major finding: Most epidermolysis bullosa patients (85.5%) presented with dysphagia, while the preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%).

Study details: A multicenter study of 497 stricture events in 125 patients with epidermolysis bullosa.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. Dr. Pope reported having no financial disclosures.

Plantar Ulcerative Lichen Planus: Rapid Improvement With a Novel Triple-Therapy Approach

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

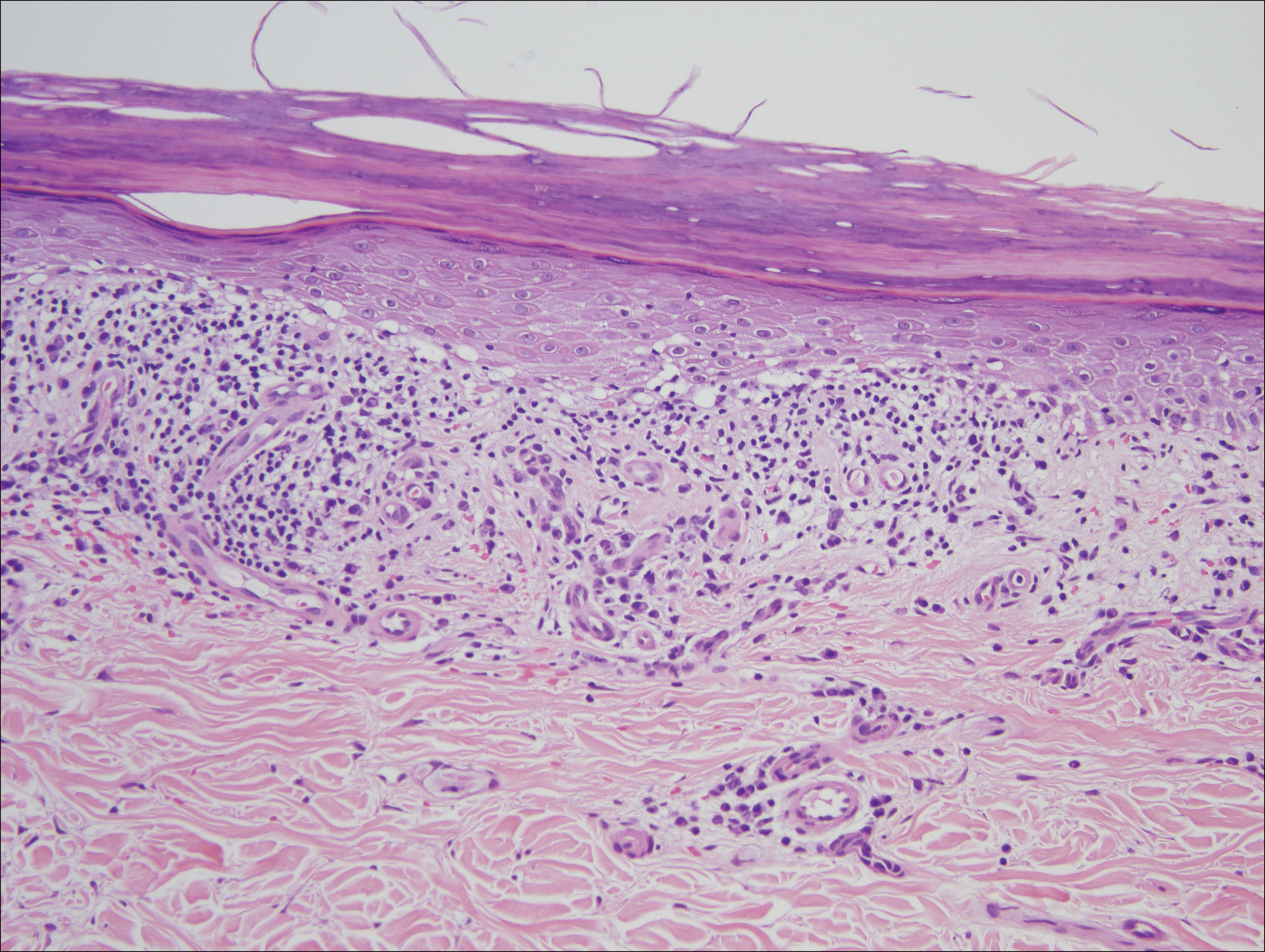

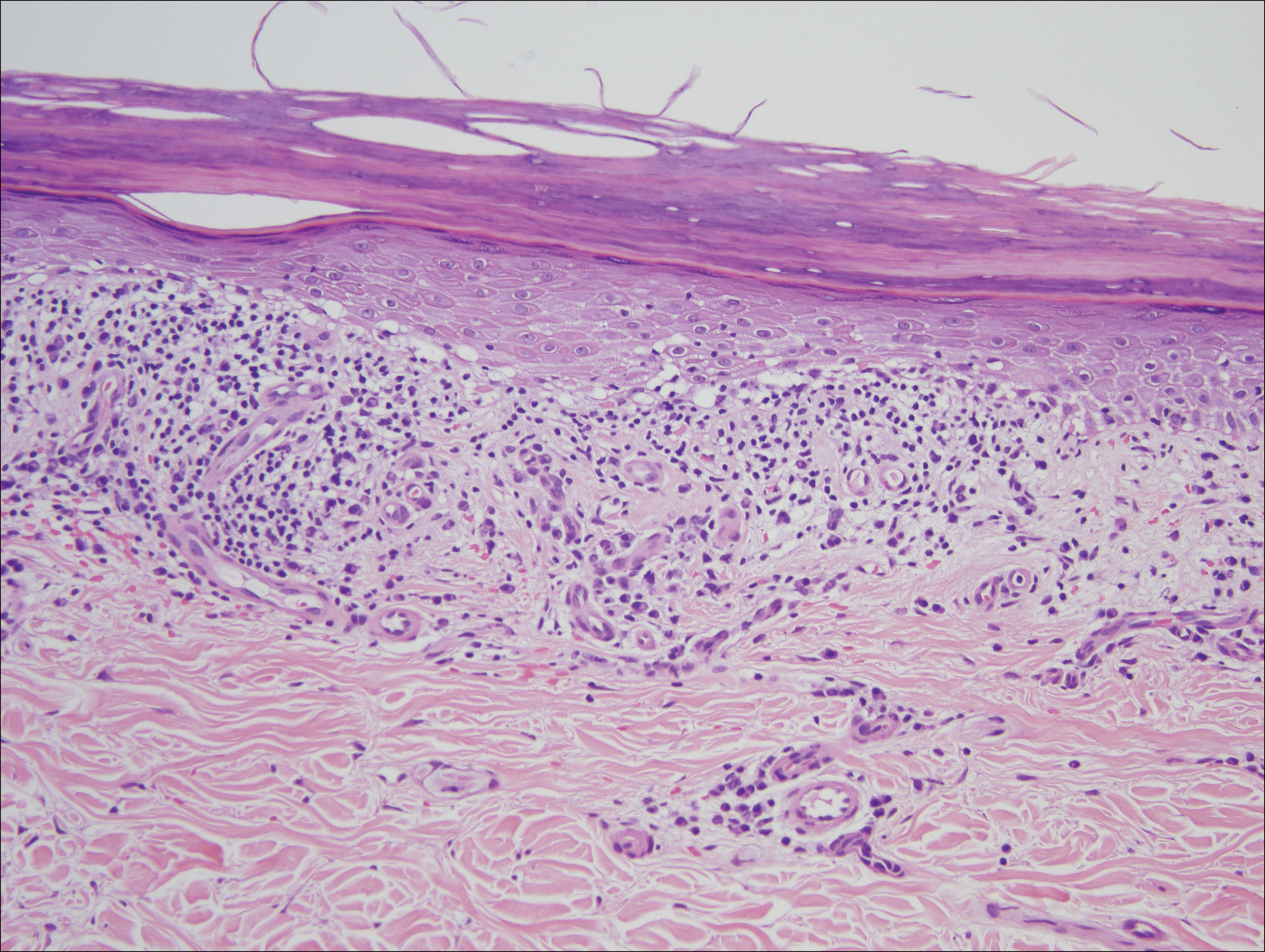

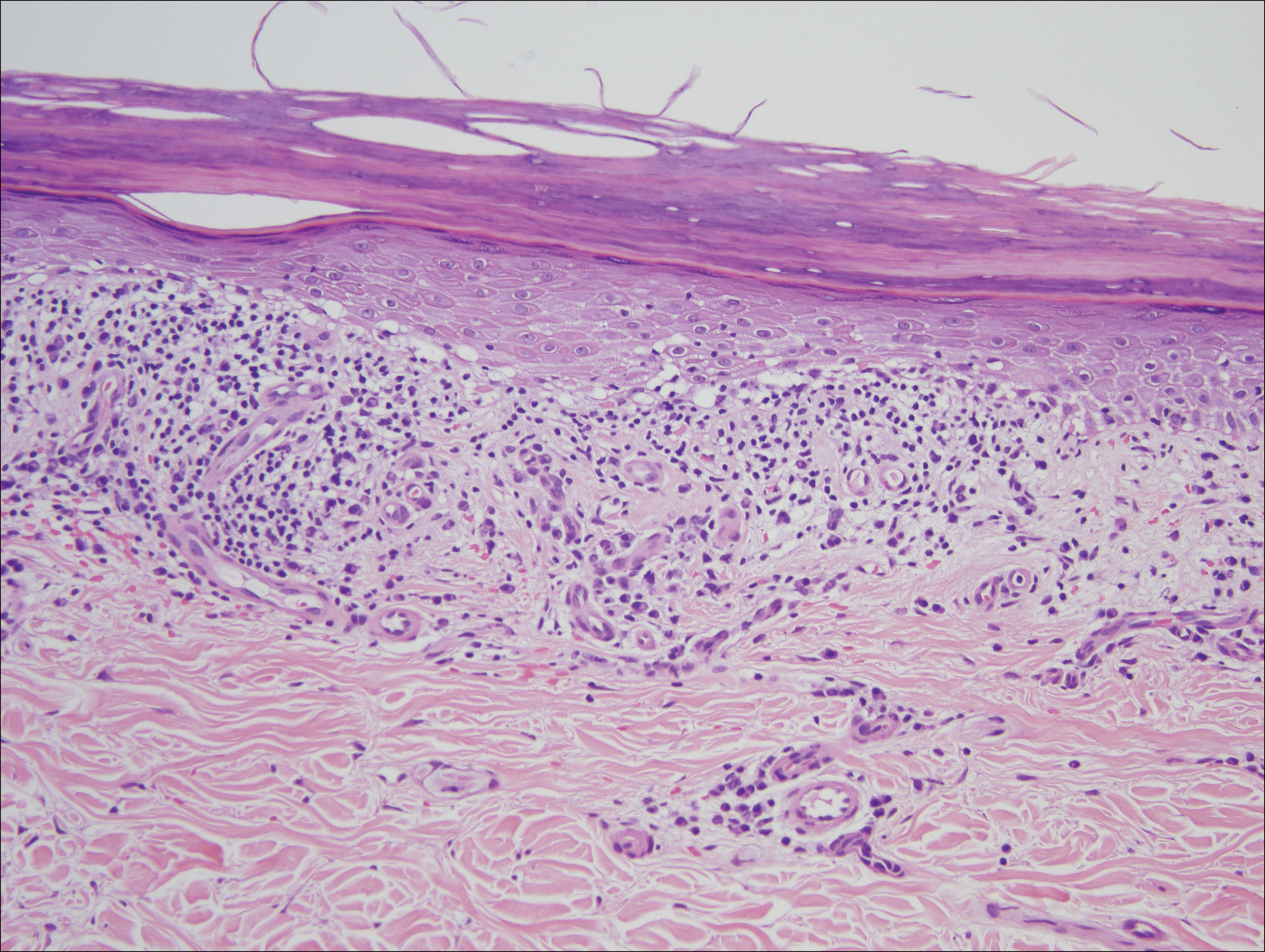

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

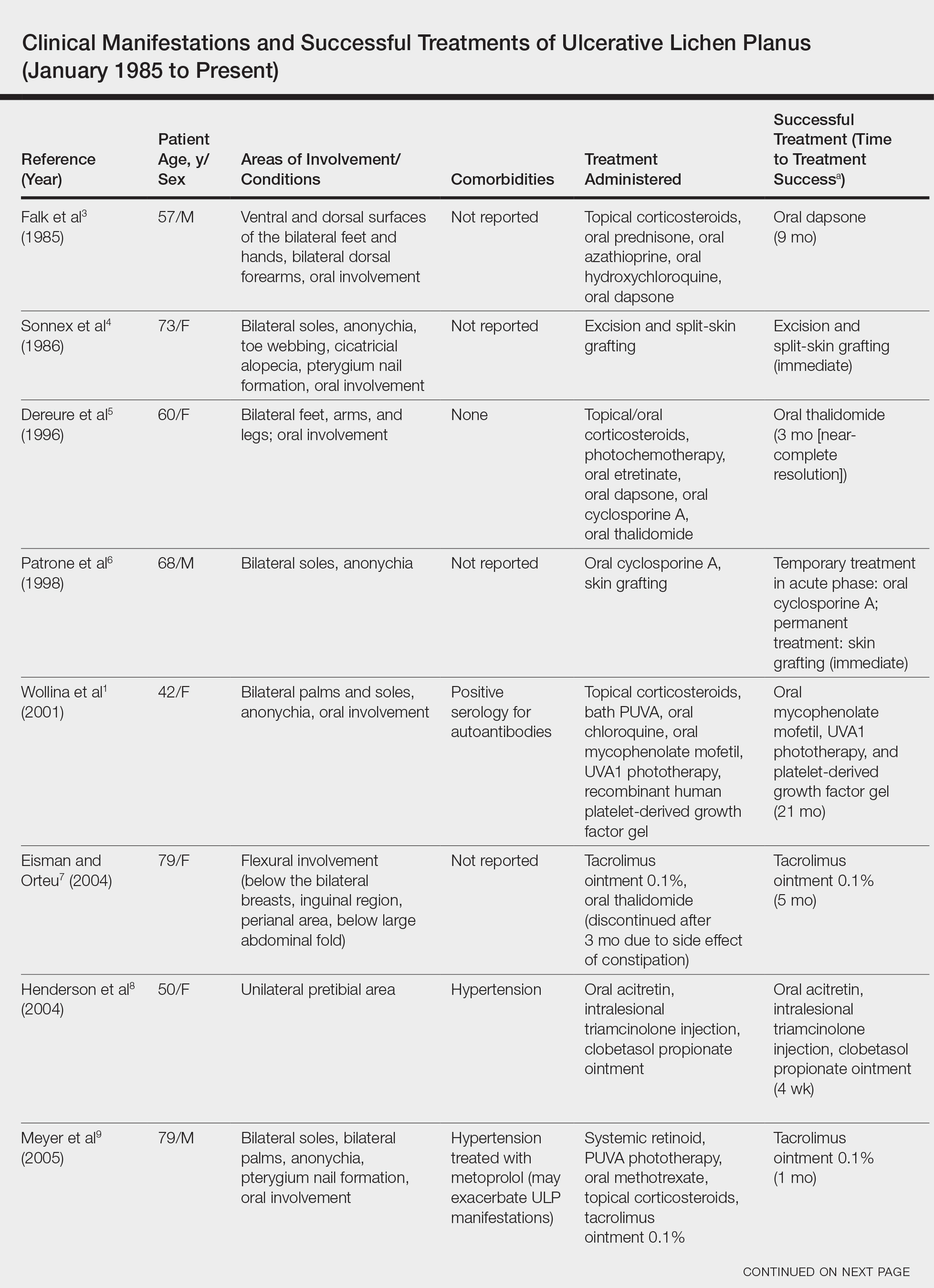

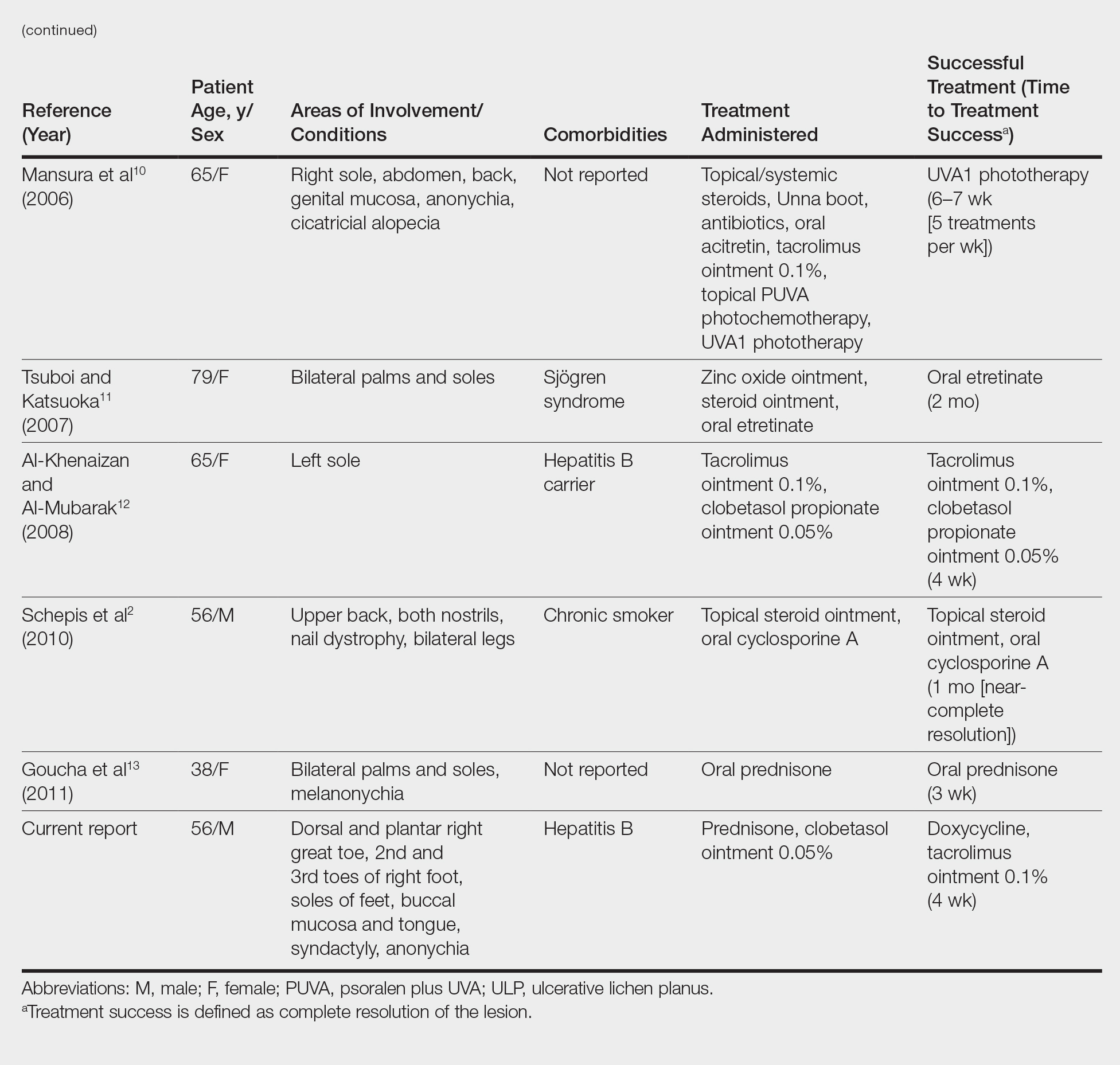

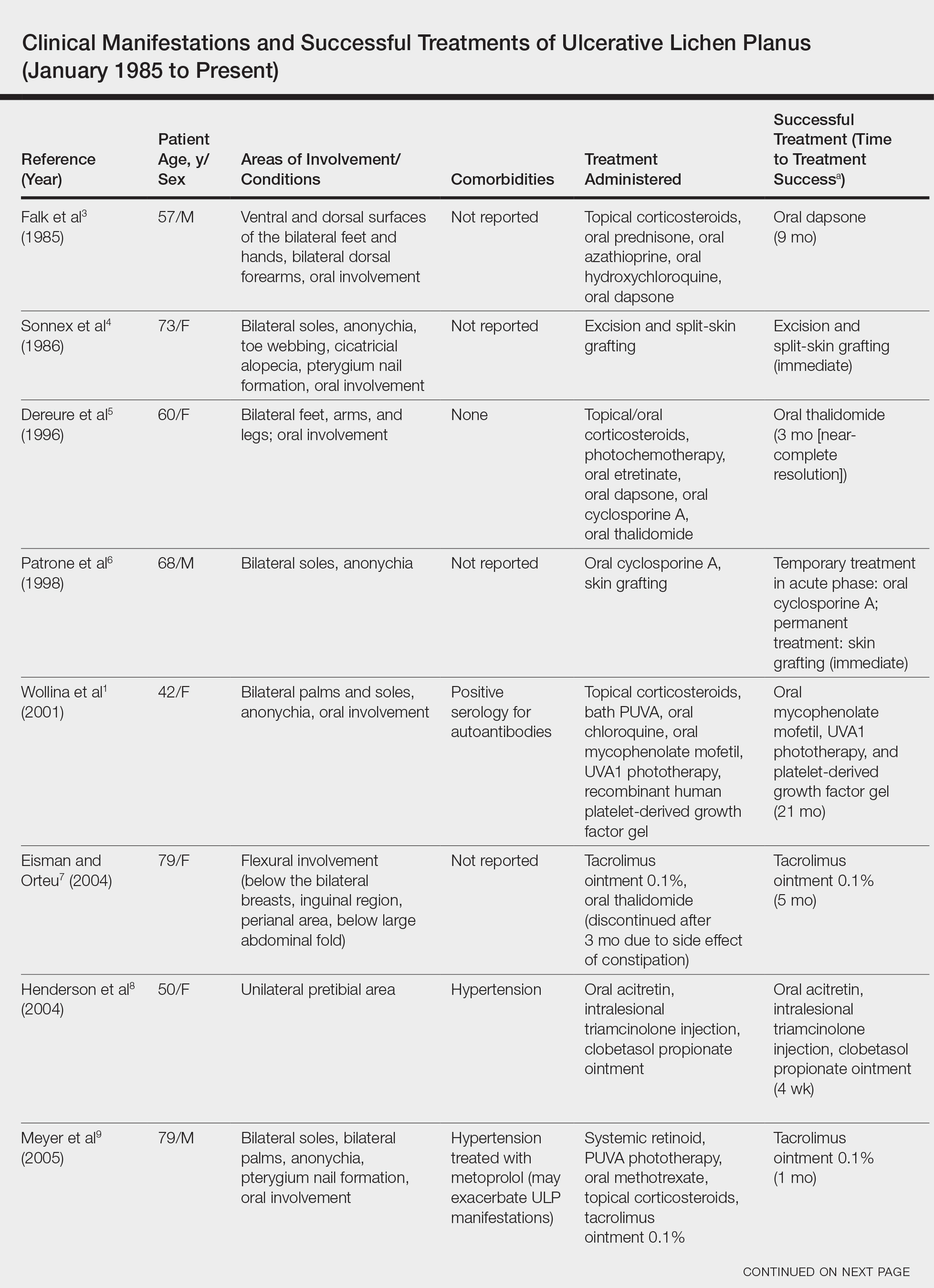

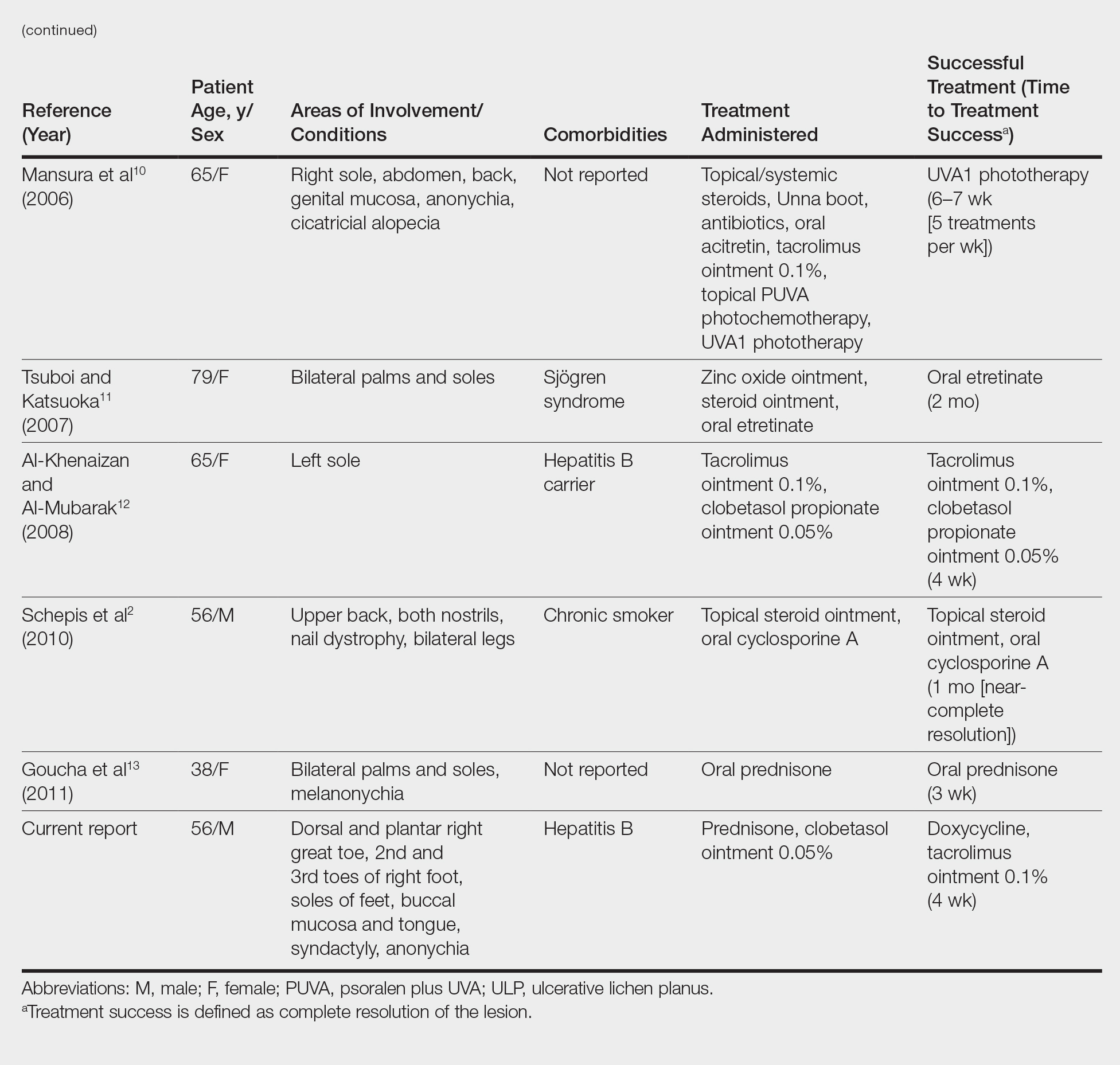

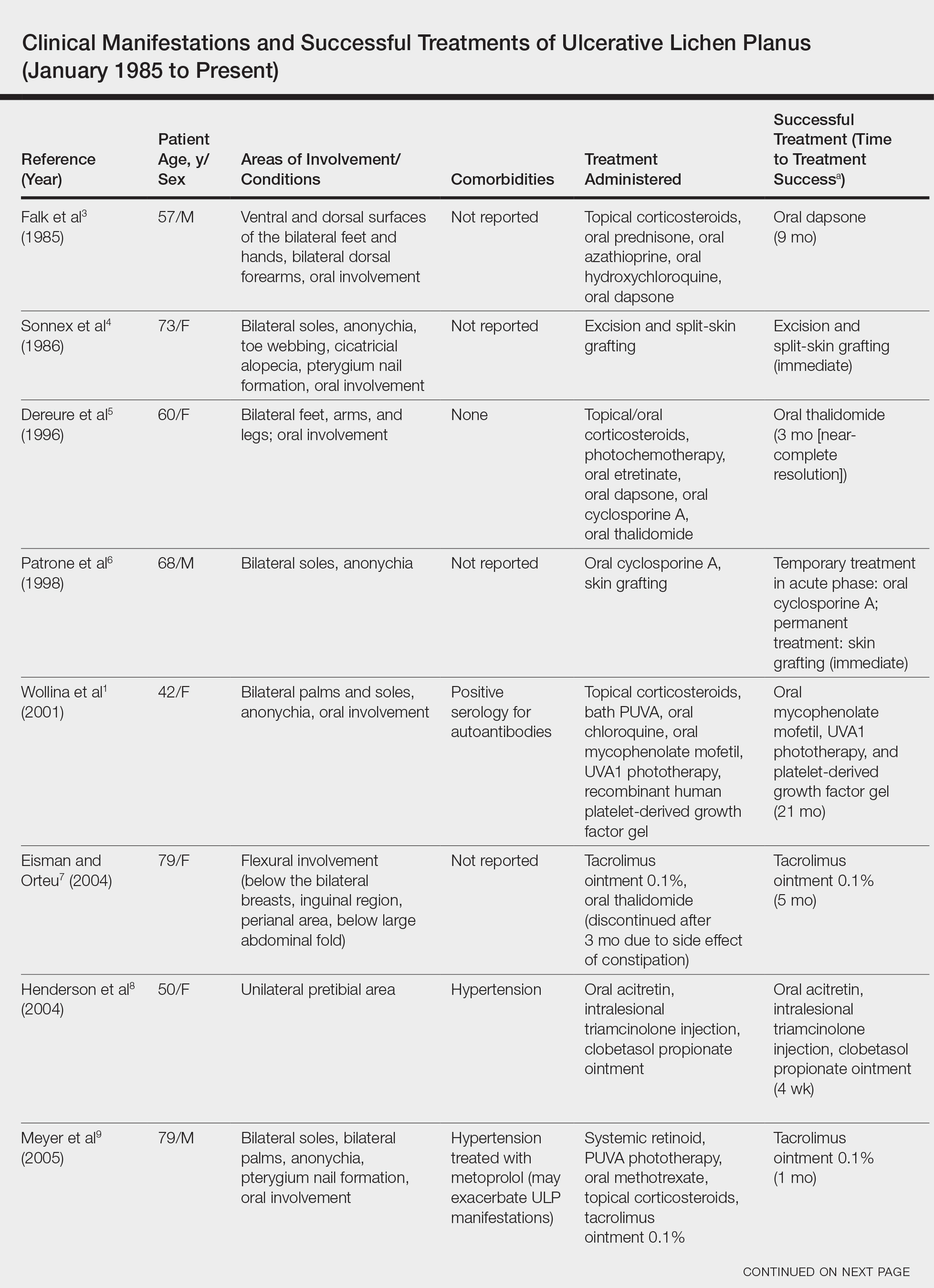

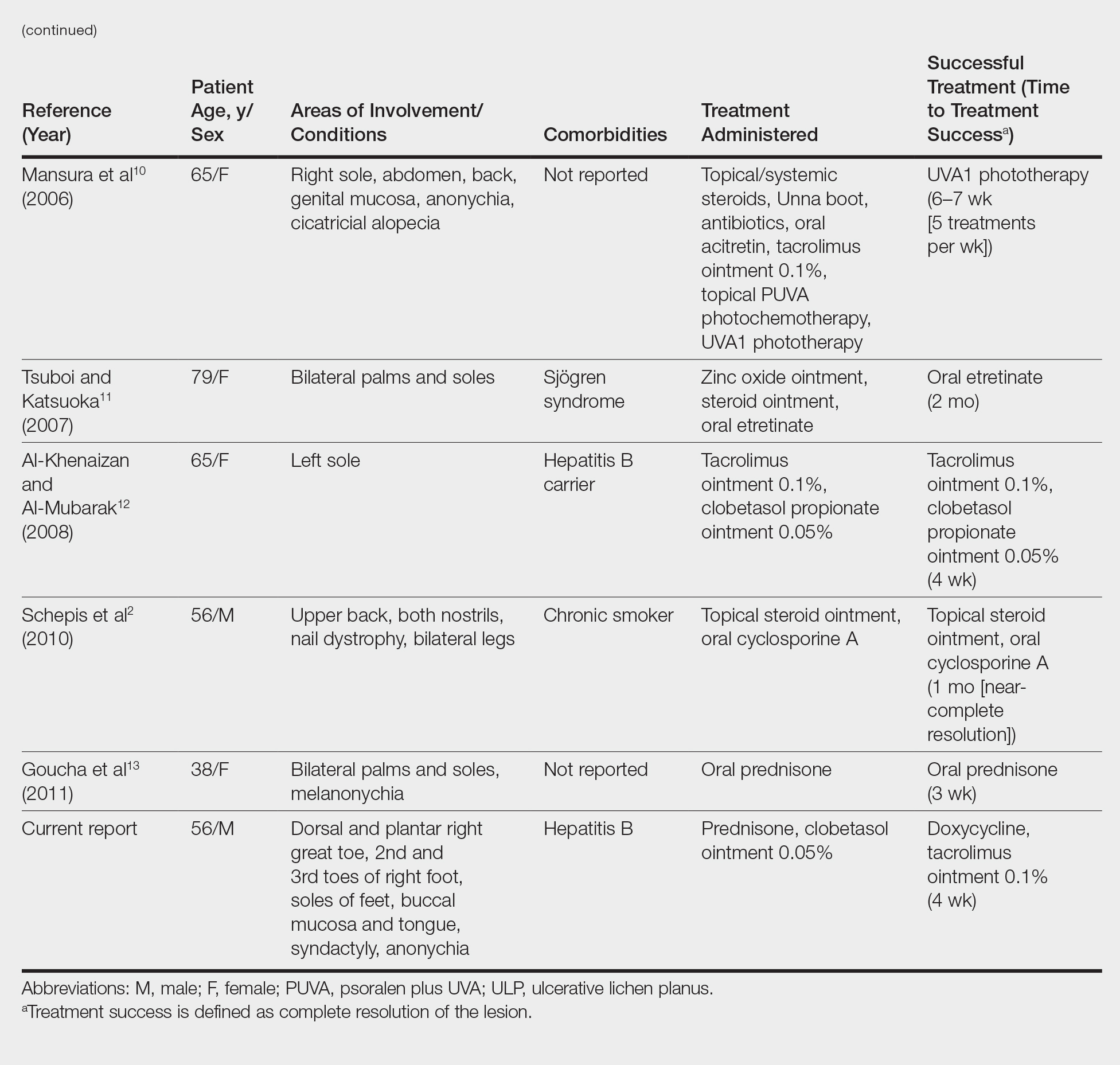

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2