User login

Antiphospholipid Syndrome in a Patient With Rheumatoid Arthritis

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman with a 20-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presented to a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital with painful ulcerations on the bilateral dorsal feet that started as bullae 16 weeks prior to presentation. Initial skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 8 weeks prior to presentation showed vasculitis and culture was positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. She was started on a prednisone taper and cephalexin, which did not improve the lower extremity ulcerations and the pain became progressively worse. At the time of presentation to our dermatology department, the patient was taking prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, hydrocodone-acetaminophen, and gabapentin. Prior therapy with sulfasalazine failed; etanercept and methotrexate were discontinued years prior due to side effects. The patient had no history of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or miscarriage.

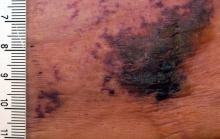

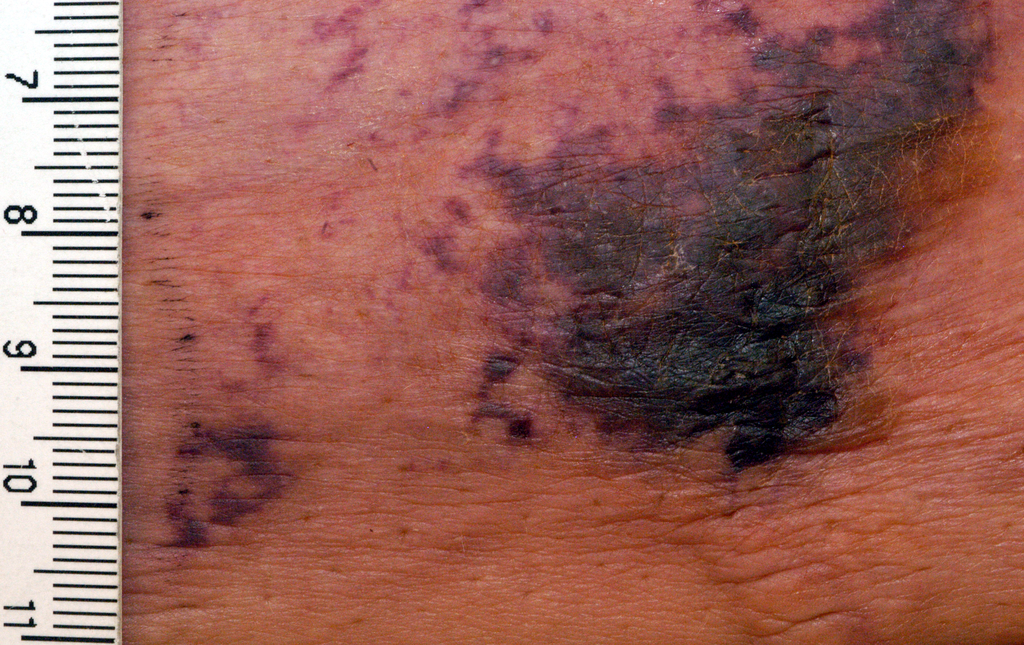

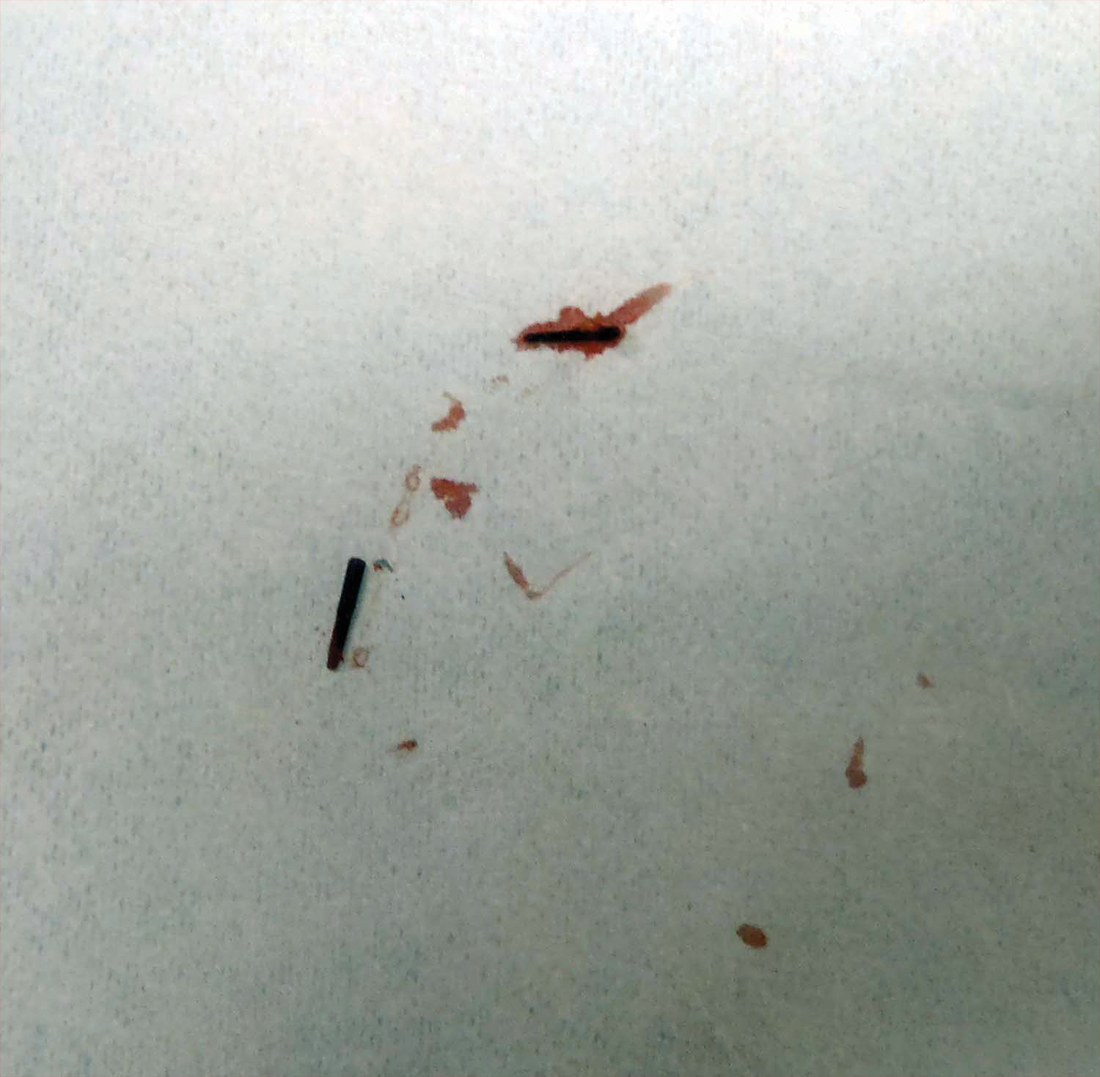

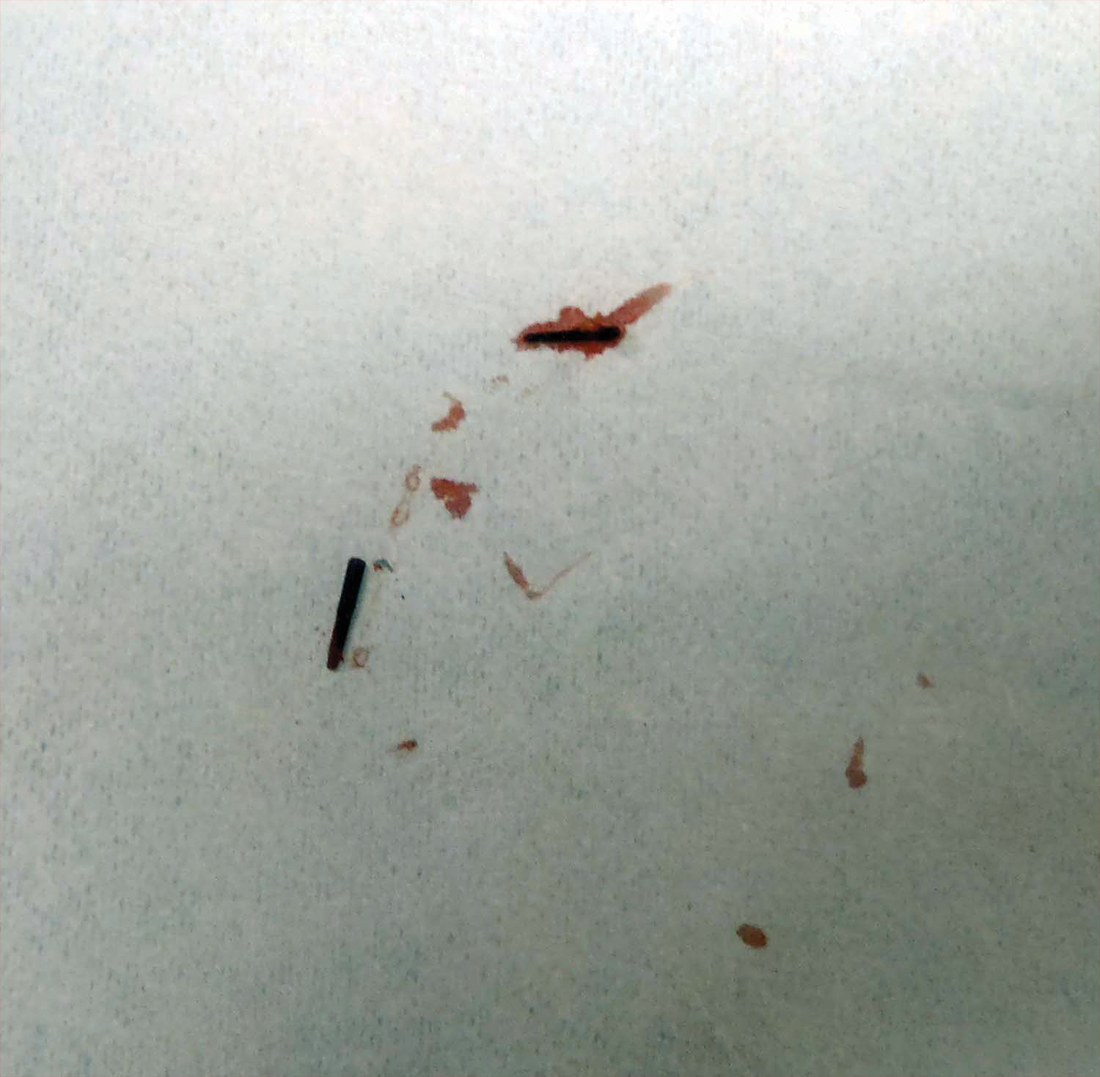

At presentation, the patient was afebrile and her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed multiple ulcers and erosions on the bilateral dorsal feet with a few scattered retiform red-purple patches (Figure). One bulla was present on the right dorsal foot. All lesions were tender to the touch and edema was present on the bilateral feet. No oral ulcerations were present and no focal neuropathies or palpable cords were appreciated in the lower extremities. There were no other cutaneous abnormalities.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 9.54×103/µL (reference range, 4.16-9.95×103/µL), hemoglobin count of 12.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL), and a platelet count of 175×103/µL (reference range, 143-398×103/µL). A basic metabolic panel was normal except for an elevated glucose level of 185 mg/dL (reference range, 65-100 mg/dL). Urinalysis was normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were not elevated. Antinuclear antibodies and double-stranded DNA antibodies were normal. Prothrombin time was 10.4 seconds (reference range, 9.2-11.5 seconds) and dilute viper's venom time was negative. Rheumatoid factor level was elevated at 76 IU/mL (reference range, <25 IU/mL) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibody was moderately elevated at 42 U/mL (negative, <20 U/mL; weak positive, 20-39 U/mL; moderate positive, 40-59 U/mL; strong positive, >59 U/mL). The cardiolipin antibodies IgG, IgM, and IgA were within reference range. Results of β2-glycoprotein I IgG and IgM antibody tests were normal, but IgA was elevated at 34 µg/mL (reference range, <20 µg/mL). Wound cultures grew moderate Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

Slides from 2 prior punch biopsies obtained by an outside hospital approximately 8 weeks prior from the right and left dorsal foot lesions were reviewed. Both biopsies were histologically similar. Postcapillary venules showed extensive vasculitis with numerous fibrin thrombi in the lumens in both biopsy specimens. The biopsy from the right foot showed prominent ulceration of the epidermis, with a few of the affected vessels showing minimal accompanying nuclear dust; however, the predominant pattern was not that of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Biopsy from the left foot showed prominent epidermal necrosis with focal reepithelialization and scattered eosinophils. The pathologist felt that a vasculitis secondary to coagulopathy was most likely but that a drug reaction and rheumatoid vasculitis would be other entities to consider in the differential. A review of the laboratory findings from the outside hospital from approximately 12 weeks prior to presentation showed IgM was normal but IgG was elevated at 28 U/mL (reference range, 0-15 U/mL) and IgA was elevated at 8 U/mL (reference range, 0-7 U/mL); β2-glycoprotein I IgG antibodies were elevated at 37 mg/dL (reference range, 0-25.0 mg/dL) and β2-glycoprotein I IgA antibodies were elevated at 5 mg/dL (reference range, 0-4.0 mg/dL).

The clinical suspicion of a thrombotic event on the dorsal feet, which was confirmed histologically, and the persistently positive antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody titers helped to establish the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) in the setting of RA. The dose of prednisone was increased from 10 mg daily on admission to 40 mg daily. The patient was started on enoxaparin 60 mg subcutaneously twice daily at initial presentation and was bridged to oral warfarin 2 mg daily after the diagnosis of APS was established. Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started for wound infection. The ulcerations gradually improved over the course of her 7-day hospitalization. She was continued on prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and warfarin as an outpatient and has had no recurrence of lesions after 3 years of follow-up on this regimen.

Comment

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune condition defined by a venous and/or arterial thrombotic event and/or pregnancy morbidity in the presence of persistently elevated aPL antibody titers. The most frequently detected subgroups of aPL are anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, and lupus anticoagulants.1 Primary APS occurs as an isolated entity, whereas secondary APS occurs in the setting of a preexisting autoimmune disease, infection, malignancy, or medication.2 The diagnostic criteria for APS requires positive aPL titers at least 12 weeks apart and a clinically confirmed thrombotic event or pregnancy morbidity.3

About one-third to half of patients with APS exhibit cutaneous manifestations.4,5 Livedo reticularis is most commonly observed and represents the first clinical sign of APS in 17.5% of cases.6 Cutaneous findings of APS also include anetoderma, cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, purpura, ecchymoses, painful skin nodules, and subungual hemorrhages.7 The various cutaneous manifestations of APS are associated with a range of histopathologic findings, but noninflammatory thrombosis in small arteries and/or veins in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue is the most common histologic feature.4 Our patient exhibited cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, and biopsy clearly showed the presence of vasculitis and fibrin thrombi within postcapillary venules. These findings along with the persistently elevated β2-glycoprotein I IgA solidified the diagnosis of APS.

The most common cutaneous manifestations of RA are nodules (32%), Raynaud phenomenon (10%), and vasculitis (3%).8 The mean prevalence of aPL antibodies in patients with RA is 28%, though reports range from 5% to 75%.1 The presence of aPL or aCL does not predict the development of thrombosis and/or thrombocytopenia in RA patients9,10; however, aCL antibodies in RA patients are associated with a higher risk for developing rheumatoid nodules. It is hypothesized that the majority of aCL antibodies identified in RA patients have different specificities than those identified in other diseases that are associated with thrombotic events.1

Anticoagulation has been proven to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombotic events in patients with APS.11 Patients should discontinue the use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives; avoid smoking cigarettes; and treat hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, if present. The type and duration of anticoagulation therapy, especially for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of APS, is less well defined. Antiplatelet therapies such as low-dose aspirin or dipyridamole often are used for less severe cutaneous manifestations such as livedoid vasculopathy. Warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 is most commonly used following major thrombotic events, including cutaneous necrosis and digital gangrene. The role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is unclear; one study showed that these therapies did not prevent further thrombotic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.4

Conclusion

Although aPL antibodies are most prevalent in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, an estimated 28% of patients with RA have elevated aPL titers. The aPL antibodies recognized in RA patients are thought to have a different specificity than those recognized in other APS-associated diseases because elevated aPL antibody titers are not associated with an increased incidence of thrombotic events in RA patients; however, larger studies are needed to clarify this phenomenon. It remains to be determined if this case of APS and RA represents a coincidence or a true disease association, but the recognition of the cutaneous and histological features of APS is crucial for establishing a diagnosis and initiating anticoagulation therapy to prevent further morbidity and mortality.

- Olech E, Merrill JT. The prevalence and clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:100-108.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Asherson A, Francès C, Iaccarino FL, et al. Theantiphospholipid antibody syndrome: diagnosis, skin manifestations and current therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(1 suppl 40):S46-S51.

- Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, et al; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019-1027.

- Francès C, Niang S, Laffitte E, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1785-1793.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):970-982.

- Young A. Extra-articular manifestations and complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:907-927.

- Palomo I, Pinochet C, Alarcón M, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in Chilean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;20:190-194.

- Wolf P, Gretler J, Aglas F, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: their relation to rheumatoid nodules and cutaneous vascular manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:48-51.

- Lim W, Crowther MA, Eikelboom JW. Management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;295:1050-1057.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman with a 20-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presented to a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital with painful ulcerations on the bilateral dorsal feet that started as bullae 16 weeks prior to presentation. Initial skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 8 weeks prior to presentation showed vasculitis and culture was positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. She was started on a prednisone taper and cephalexin, which did not improve the lower extremity ulcerations and the pain became progressively worse. At the time of presentation to our dermatology department, the patient was taking prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, hydrocodone-acetaminophen, and gabapentin. Prior therapy with sulfasalazine failed; etanercept and methotrexate were discontinued years prior due to side effects. The patient had no history of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or miscarriage.

At presentation, the patient was afebrile and her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed multiple ulcers and erosions on the bilateral dorsal feet with a few scattered retiform red-purple patches (Figure). One bulla was present on the right dorsal foot. All lesions were tender to the touch and edema was present on the bilateral feet. No oral ulcerations were present and no focal neuropathies or palpable cords were appreciated in the lower extremities. There were no other cutaneous abnormalities.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 9.54×103/µL (reference range, 4.16-9.95×103/µL), hemoglobin count of 12.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL), and a platelet count of 175×103/µL (reference range, 143-398×103/µL). A basic metabolic panel was normal except for an elevated glucose level of 185 mg/dL (reference range, 65-100 mg/dL). Urinalysis was normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were not elevated. Antinuclear antibodies and double-stranded DNA antibodies were normal. Prothrombin time was 10.4 seconds (reference range, 9.2-11.5 seconds) and dilute viper's venom time was negative. Rheumatoid factor level was elevated at 76 IU/mL (reference range, <25 IU/mL) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibody was moderately elevated at 42 U/mL (negative, <20 U/mL; weak positive, 20-39 U/mL; moderate positive, 40-59 U/mL; strong positive, >59 U/mL). The cardiolipin antibodies IgG, IgM, and IgA were within reference range. Results of β2-glycoprotein I IgG and IgM antibody tests were normal, but IgA was elevated at 34 µg/mL (reference range, <20 µg/mL). Wound cultures grew moderate Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

Slides from 2 prior punch biopsies obtained by an outside hospital approximately 8 weeks prior from the right and left dorsal foot lesions were reviewed. Both biopsies were histologically similar. Postcapillary venules showed extensive vasculitis with numerous fibrin thrombi in the lumens in both biopsy specimens. The biopsy from the right foot showed prominent ulceration of the epidermis, with a few of the affected vessels showing minimal accompanying nuclear dust; however, the predominant pattern was not that of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Biopsy from the left foot showed prominent epidermal necrosis with focal reepithelialization and scattered eosinophils. The pathologist felt that a vasculitis secondary to coagulopathy was most likely but that a drug reaction and rheumatoid vasculitis would be other entities to consider in the differential. A review of the laboratory findings from the outside hospital from approximately 12 weeks prior to presentation showed IgM was normal but IgG was elevated at 28 U/mL (reference range, 0-15 U/mL) and IgA was elevated at 8 U/mL (reference range, 0-7 U/mL); β2-glycoprotein I IgG antibodies were elevated at 37 mg/dL (reference range, 0-25.0 mg/dL) and β2-glycoprotein I IgA antibodies were elevated at 5 mg/dL (reference range, 0-4.0 mg/dL).

The clinical suspicion of a thrombotic event on the dorsal feet, which was confirmed histologically, and the persistently positive antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody titers helped to establish the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) in the setting of RA. The dose of prednisone was increased from 10 mg daily on admission to 40 mg daily. The patient was started on enoxaparin 60 mg subcutaneously twice daily at initial presentation and was bridged to oral warfarin 2 mg daily after the diagnosis of APS was established. Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started for wound infection. The ulcerations gradually improved over the course of her 7-day hospitalization. She was continued on prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and warfarin as an outpatient and has had no recurrence of lesions after 3 years of follow-up on this regimen.

Comment

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune condition defined by a venous and/or arterial thrombotic event and/or pregnancy morbidity in the presence of persistently elevated aPL antibody titers. The most frequently detected subgroups of aPL are anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, and lupus anticoagulants.1 Primary APS occurs as an isolated entity, whereas secondary APS occurs in the setting of a preexisting autoimmune disease, infection, malignancy, or medication.2 The diagnostic criteria for APS requires positive aPL titers at least 12 weeks apart and a clinically confirmed thrombotic event or pregnancy morbidity.3

About one-third to half of patients with APS exhibit cutaneous manifestations.4,5 Livedo reticularis is most commonly observed and represents the first clinical sign of APS in 17.5% of cases.6 Cutaneous findings of APS also include anetoderma, cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, purpura, ecchymoses, painful skin nodules, and subungual hemorrhages.7 The various cutaneous manifestations of APS are associated with a range of histopathologic findings, but noninflammatory thrombosis in small arteries and/or veins in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue is the most common histologic feature.4 Our patient exhibited cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, and biopsy clearly showed the presence of vasculitis and fibrin thrombi within postcapillary venules. These findings along with the persistently elevated β2-glycoprotein I IgA solidified the diagnosis of APS.

The most common cutaneous manifestations of RA are nodules (32%), Raynaud phenomenon (10%), and vasculitis (3%).8 The mean prevalence of aPL antibodies in patients with RA is 28%, though reports range from 5% to 75%.1 The presence of aPL or aCL does not predict the development of thrombosis and/or thrombocytopenia in RA patients9,10; however, aCL antibodies in RA patients are associated with a higher risk for developing rheumatoid nodules. It is hypothesized that the majority of aCL antibodies identified in RA patients have different specificities than those identified in other diseases that are associated with thrombotic events.1

Anticoagulation has been proven to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombotic events in patients with APS.11 Patients should discontinue the use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives; avoid smoking cigarettes; and treat hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, if present. The type and duration of anticoagulation therapy, especially for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of APS, is less well defined. Antiplatelet therapies such as low-dose aspirin or dipyridamole often are used for less severe cutaneous manifestations such as livedoid vasculopathy. Warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 is most commonly used following major thrombotic events, including cutaneous necrosis and digital gangrene. The role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is unclear; one study showed that these therapies did not prevent further thrombotic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.4

Conclusion

Although aPL antibodies are most prevalent in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, an estimated 28% of patients with RA have elevated aPL titers. The aPL antibodies recognized in RA patients are thought to have a different specificity than those recognized in other APS-associated diseases because elevated aPL antibody titers are not associated with an increased incidence of thrombotic events in RA patients; however, larger studies are needed to clarify this phenomenon. It remains to be determined if this case of APS and RA represents a coincidence or a true disease association, but the recognition of the cutaneous and histological features of APS is crucial for establishing a diagnosis and initiating anticoagulation therapy to prevent further morbidity and mortality.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman with a 20-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presented to a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital with painful ulcerations on the bilateral dorsal feet that started as bullae 16 weeks prior to presentation. Initial skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 8 weeks prior to presentation showed vasculitis and culture was positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. She was started on a prednisone taper and cephalexin, which did not improve the lower extremity ulcerations and the pain became progressively worse. At the time of presentation to our dermatology department, the patient was taking prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, hydrocodone-acetaminophen, and gabapentin. Prior therapy with sulfasalazine failed; etanercept and methotrexate were discontinued years prior due to side effects. The patient had no history of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or miscarriage.

At presentation, the patient was afebrile and her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed multiple ulcers and erosions on the bilateral dorsal feet with a few scattered retiform red-purple patches (Figure). One bulla was present on the right dorsal foot. All lesions were tender to the touch and edema was present on the bilateral feet. No oral ulcerations were present and no focal neuropathies or palpable cords were appreciated in the lower extremities. There were no other cutaneous abnormalities.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 9.54×103/µL (reference range, 4.16-9.95×103/µL), hemoglobin count of 12.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL), and a platelet count of 175×103/µL (reference range, 143-398×103/µL). A basic metabolic panel was normal except for an elevated glucose level of 185 mg/dL (reference range, 65-100 mg/dL). Urinalysis was normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were not elevated. Antinuclear antibodies and double-stranded DNA antibodies were normal. Prothrombin time was 10.4 seconds (reference range, 9.2-11.5 seconds) and dilute viper's venom time was negative. Rheumatoid factor level was elevated at 76 IU/mL (reference range, <25 IU/mL) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibody was moderately elevated at 42 U/mL (negative, <20 U/mL; weak positive, 20-39 U/mL; moderate positive, 40-59 U/mL; strong positive, >59 U/mL). The cardiolipin antibodies IgG, IgM, and IgA were within reference range. Results of β2-glycoprotein I IgG and IgM antibody tests were normal, but IgA was elevated at 34 µg/mL (reference range, <20 µg/mL). Wound cultures grew moderate Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

Slides from 2 prior punch biopsies obtained by an outside hospital approximately 8 weeks prior from the right and left dorsal foot lesions were reviewed. Both biopsies were histologically similar. Postcapillary venules showed extensive vasculitis with numerous fibrin thrombi in the lumens in both biopsy specimens. The biopsy from the right foot showed prominent ulceration of the epidermis, with a few of the affected vessels showing minimal accompanying nuclear dust; however, the predominant pattern was not that of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Biopsy from the left foot showed prominent epidermal necrosis with focal reepithelialization and scattered eosinophils. The pathologist felt that a vasculitis secondary to coagulopathy was most likely but that a drug reaction and rheumatoid vasculitis would be other entities to consider in the differential. A review of the laboratory findings from the outside hospital from approximately 12 weeks prior to presentation showed IgM was normal but IgG was elevated at 28 U/mL (reference range, 0-15 U/mL) and IgA was elevated at 8 U/mL (reference range, 0-7 U/mL); β2-glycoprotein I IgG antibodies were elevated at 37 mg/dL (reference range, 0-25.0 mg/dL) and β2-glycoprotein I IgA antibodies were elevated at 5 mg/dL (reference range, 0-4.0 mg/dL).

The clinical suspicion of a thrombotic event on the dorsal feet, which was confirmed histologically, and the persistently positive antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody titers helped to establish the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) in the setting of RA. The dose of prednisone was increased from 10 mg daily on admission to 40 mg daily. The patient was started on enoxaparin 60 mg subcutaneously twice daily at initial presentation and was bridged to oral warfarin 2 mg daily after the diagnosis of APS was established. Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started for wound infection. The ulcerations gradually improved over the course of her 7-day hospitalization. She was continued on prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and warfarin as an outpatient and has had no recurrence of lesions after 3 years of follow-up on this regimen.

Comment

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune condition defined by a venous and/or arterial thrombotic event and/or pregnancy morbidity in the presence of persistently elevated aPL antibody titers. The most frequently detected subgroups of aPL are anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, and lupus anticoagulants.1 Primary APS occurs as an isolated entity, whereas secondary APS occurs in the setting of a preexisting autoimmune disease, infection, malignancy, or medication.2 The diagnostic criteria for APS requires positive aPL titers at least 12 weeks apart and a clinically confirmed thrombotic event or pregnancy morbidity.3

About one-third to half of patients with APS exhibit cutaneous manifestations.4,5 Livedo reticularis is most commonly observed and represents the first clinical sign of APS in 17.5% of cases.6 Cutaneous findings of APS also include anetoderma, cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, purpura, ecchymoses, painful skin nodules, and subungual hemorrhages.7 The various cutaneous manifestations of APS are associated with a range of histopathologic findings, but noninflammatory thrombosis in small arteries and/or veins in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue is the most common histologic feature.4 Our patient exhibited cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, and biopsy clearly showed the presence of vasculitis and fibrin thrombi within postcapillary venules. These findings along with the persistently elevated β2-glycoprotein I IgA solidified the diagnosis of APS.

The most common cutaneous manifestations of RA are nodules (32%), Raynaud phenomenon (10%), and vasculitis (3%).8 The mean prevalence of aPL antibodies in patients with RA is 28%, though reports range from 5% to 75%.1 The presence of aPL or aCL does not predict the development of thrombosis and/or thrombocytopenia in RA patients9,10; however, aCL antibodies in RA patients are associated with a higher risk for developing rheumatoid nodules. It is hypothesized that the majority of aCL antibodies identified in RA patients have different specificities than those identified in other diseases that are associated with thrombotic events.1

Anticoagulation has been proven to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombotic events in patients with APS.11 Patients should discontinue the use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives; avoid smoking cigarettes; and treat hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, if present. The type and duration of anticoagulation therapy, especially for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of APS, is less well defined. Antiplatelet therapies such as low-dose aspirin or dipyridamole often are used for less severe cutaneous manifestations such as livedoid vasculopathy. Warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 is most commonly used following major thrombotic events, including cutaneous necrosis and digital gangrene. The role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is unclear; one study showed that these therapies did not prevent further thrombotic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.4

Conclusion

Although aPL antibodies are most prevalent in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, an estimated 28% of patients with RA have elevated aPL titers. The aPL antibodies recognized in RA patients are thought to have a different specificity than those recognized in other APS-associated diseases because elevated aPL antibody titers are not associated with an increased incidence of thrombotic events in RA patients; however, larger studies are needed to clarify this phenomenon. It remains to be determined if this case of APS and RA represents a coincidence or a true disease association, but the recognition of the cutaneous and histological features of APS is crucial for establishing a diagnosis and initiating anticoagulation therapy to prevent further morbidity and mortality.

- Olech E, Merrill JT. The prevalence and clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:100-108.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Asherson A, Francès C, Iaccarino FL, et al. Theantiphospholipid antibody syndrome: diagnosis, skin manifestations and current therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(1 suppl 40):S46-S51.

- Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, et al; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019-1027.

- Francès C, Niang S, Laffitte E, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1785-1793.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):970-982.

- Young A. Extra-articular manifestations and complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:907-927.

- Palomo I, Pinochet C, Alarcón M, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in Chilean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;20:190-194.

- Wolf P, Gretler J, Aglas F, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: their relation to rheumatoid nodules and cutaneous vascular manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:48-51.

- Lim W, Crowther MA, Eikelboom JW. Management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;295:1050-1057.

- Olech E, Merrill JT. The prevalence and clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:100-108.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Asherson A, Francès C, Iaccarino FL, et al. Theantiphospholipid antibody syndrome: diagnosis, skin manifestations and current therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(1 suppl 40):S46-S51.

- Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, et al; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019-1027.

- Francès C, Niang S, Laffitte E, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1785-1793.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):970-982.

- Young A. Extra-articular manifestations and complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:907-927.

- Palomo I, Pinochet C, Alarcón M, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in Chilean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;20:190-194.

- Wolf P, Gretler J, Aglas F, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: their relation to rheumatoid nodules and cutaneous vascular manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:48-51.

- Lim W, Crowther MA, Eikelboom JW. Management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;295:1050-1057.

Practice Points

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune condition defined by a venous and/or arterial thrombotic event and/or pregnancy morbidity in the presence of persistently elevated antiphospholipid antibody titers.

- Cutaneous findings of APS include livedo reticularis most commonly but also anetoderma, cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, purpura, ecchymoses, painful skin nodules, and subungual hemorrhages.

- The various cutaneous manifestations of APS are associated with a range of histopathologic findings, but noninflammatory thrombosis in small arteries and/or veins in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue is the most common histologic feature.

New auto-grafting techniques could advance wound healing

MIAMI – Pinch grafting can accelerate the healing of chronic, treatment-resistant wounds such as leg ulcers, while at the same time reducing morbidity to the donor skin site. A new epidermal harvesting device also is showing promise, as is a new tool that minces autologous skin grafts prior to application to promote wound healing.

These and other advances in wound healing were presented at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. The pinch grafts and minced grafts each rely on the newly added skin to stimulate cytokines. Interestingly, there is evidence that grafts taken from hair-bearing donor sites could be superior for stimulating cytokines and accelerating wound healing, said Robert Kirsner, MD, PhD, of the University of Miami Health System.

Islands of regrowth

Physicians perform pinch grafting by taking small punches of skin from a donor site on the thigh, abdomen, or elsewhere, and then transferring the grafts to serve as islands of regrowth in a wound. Pinch grafting can be faster and less expensive than techniques typically performed in an operating room, such as meshed auto-grafting. In contrast, pinch grafting can be accomplished in an office setting “and patients can do quite well.” Dr. Kirsner said. In terms of outcomes, “our data is typical,” he added. “About 50% of refractory ulcers heal, 25% improve, and a percentage recur.”

Spreadable skin grafts

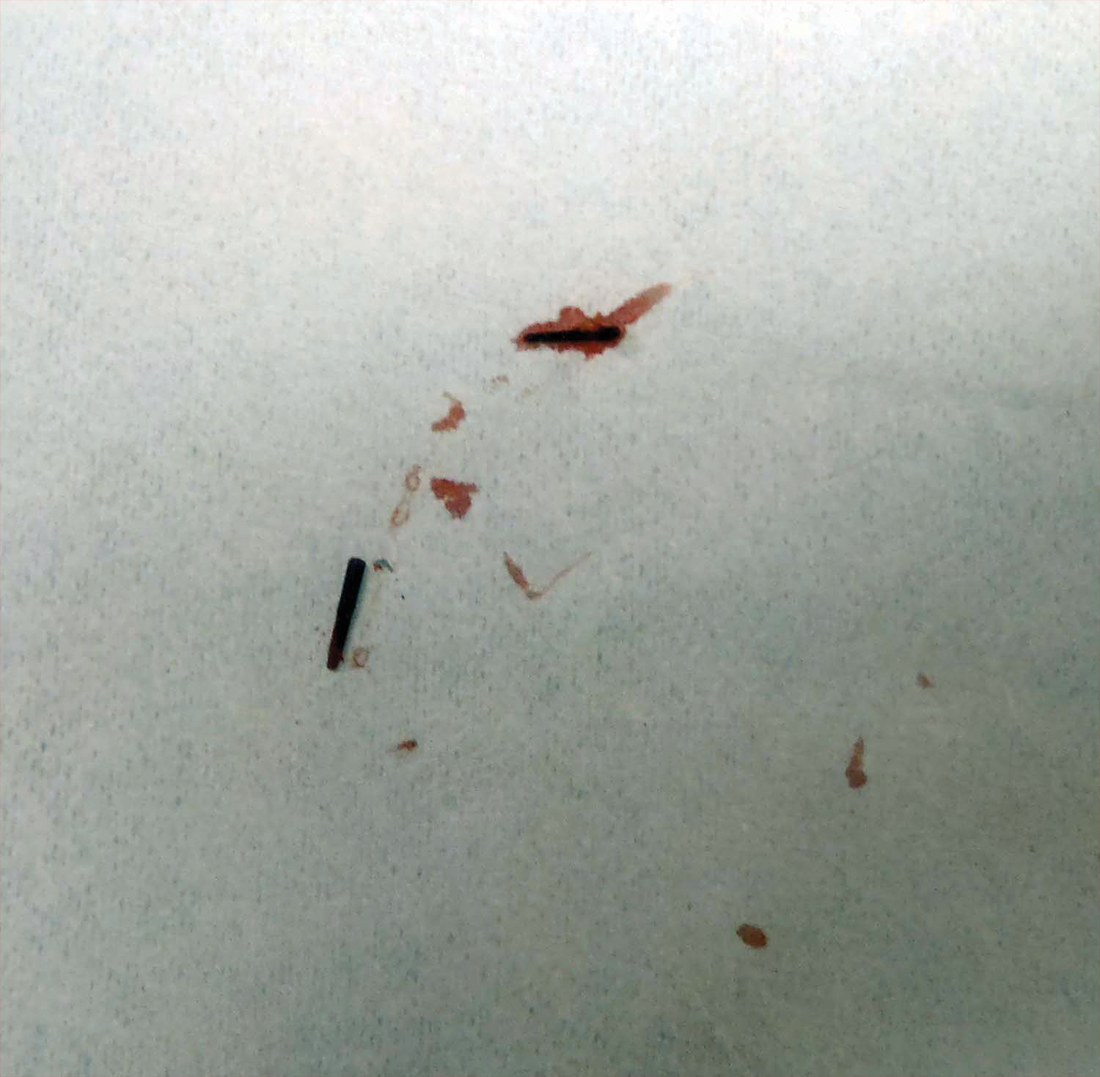

Another autologous grafting technique that can be performed at the bedside uses the Xpansion Micro-Autografting Kit, which minces autologous, split thickness skin grafts. “Then you apply them like peanut butter to bread,” Dr. Kirsner said.

The micro-autografts can help heal both acute and chronic wounds, including full thickness wounds from trauma, some burn wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, and venous ulcers, according to the manufacturer’s website.

Epidermal harvesting (without anesthesia)

Epidermal grafting can make sense because the epidermis regenerates. “You can lift off just the epidermis with heat or suction, “ Dr. Kirsner said. For the first time, he added, a new tool allows epidermal grafting without the need for anesthesia (Cellutome Epidermal Harvesting System). The device raises little microdomes of epidermis down to the basal layer, including basal keratinocytes and melanocytes, and a dermatologist can use a sterile dressing to transfer them to the wound. Confocal microscopy shows the dermoepidermal junction healing as early as within 2 days.

The epidermal harvesting was initially developed for pigment problems, such as piebaldism. (Dermatol Surg. 2017 Jan;43[1]:159-60). “We quickly realized it might have applicability for nonhealing wounds,” Dr. Kirsner said.

Deeper wound healing

A novel strategy for triggering deeper wound healing evolved from fractional laser technology, which remove columns of skin to generate healing. Instead, Rox Anderson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, “envisioned pulling up microcolumns of full thickness epidermis, all the way to the fat, placing them into a wound, and the wound would heal with very little donor site morbidity,” Dr. Kirsner said.

This tool is coming out in spring of this year, he noted. It will resemble a fractional laser, “but now you have the skin available to place in another wound.” Prior animal studies revealed a healing benefit with very little scarring, he added.

Is hairier better?

Does the donor site matter? Dr. Kirsner asked. Although dermatologists typically graft skin from an abdomen or thigh, a hair-bearing site may be a better option because of the presence of pluripotent stem cells, according to a case report (Wounds. 2016 Apr;28[4]:109-11). J.D. Fox of the University of Miami, Dr. Kirsner, and their colleagues treated a large, chronic venous leg ulcer, almost 60 cm2, with punch grafts from a variety of donor sites.

“The side that got scalp punch grafts healed better, suggesting with skin taken from richly hairy area, you’ll get better results,” Dr. Kirsner said.

Another study supports this strategy (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75[5]:1007-14). These researchers reported greater wound size reduction using grafts containing hair follicles versus nonhairy areas, again suggesting follicular stem cells play a role in better wound healing, Dr. Kirsner said. “This may be a better source of donor skin in the future.”

Dr. Kirsner is a consultant for Cardinal Health, Mölnlycke, Amniox, Organogenesis, Kerecis, Keretec, and KCI, an Acelity company.

MIAMI – Pinch grafting can accelerate the healing of chronic, treatment-resistant wounds such as leg ulcers, while at the same time reducing morbidity to the donor skin site. A new epidermal harvesting device also is showing promise, as is a new tool that minces autologous skin grafts prior to application to promote wound healing.

These and other advances in wound healing were presented at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. The pinch grafts and minced grafts each rely on the newly added skin to stimulate cytokines. Interestingly, there is evidence that grafts taken from hair-bearing donor sites could be superior for stimulating cytokines and accelerating wound healing, said Robert Kirsner, MD, PhD, of the University of Miami Health System.

Islands of regrowth

Physicians perform pinch grafting by taking small punches of skin from a donor site on the thigh, abdomen, or elsewhere, and then transferring the grafts to serve as islands of regrowth in a wound. Pinch grafting can be faster and less expensive than techniques typically performed in an operating room, such as meshed auto-grafting. In contrast, pinch grafting can be accomplished in an office setting “and patients can do quite well.” Dr. Kirsner said. In terms of outcomes, “our data is typical,” he added. “About 50% of refractory ulcers heal, 25% improve, and a percentage recur.”

Spreadable skin grafts

Another autologous grafting technique that can be performed at the bedside uses the Xpansion Micro-Autografting Kit, which minces autologous, split thickness skin grafts. “Then you apply them like peanut butter to bread,” Dr. Kirsner said.

The micro-autografts can help heal both acute and chronic wounds, including full thickness wounds from trauma, some burn wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, and venous ulcers, according to the manufacturer’s website.

Epidermal harvesting (without anesthesia)

Epidermal grafting can make sense because the epidermis regenerates. “You can lift off just the epidermis with heat or suction, “ Dr. Kirsner said. For the first time, he added, a new tool allows epidermal grafting without the need for anesthesia (Cellutome Epidermal Harvesting System). The device raises little microdomes of epidermis down to the basal layer, including basal keratinocytes and melanocytes, and a dermatologist can use a sterile dressing to transfer them to the wound. Confocal microscopy shows the dermoepidermal junction healing as early as within 2 days.

The epidermal harvesting was initially developed for pigment problems, such as piebaldism. (Dermatol Surg. 2017 Jan;43[1]:159-60). “We quickly realized it might have applicability for nonhealing wounds,” Dr. Kirsner said.

Deeper wound healing

A novel strategy for triggering deeper wound healing evolved from fractional laser technology, which remove columns of skin to generate healing. Instead, Rox Anderson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, “envisioned pulling up microcolumns of full thickness epidermis, all the way to the fat, placing them into a wound, and the wound would heal with very little donor site morbidity,” Dr. Kirsner said.

This tool is coming out in spring of this year, he noted. It will resemble a fractional laser, “but now you have the skin available to place in another wound.” Prior animal studies revealed a healing benefit with very little scarring, he added.

Is hairier better?

Does the donor site matter? Dr. Kirsner asked. Although dermatologists typically graft skin from an abdomen or thigh, a hair-bearing site may be a better option because of the presence of pluripotent stem cells, according to a case report (Wounds. 2016 Apr;28[4]:109-11). J.D. Fox of the University of Miami, Dr. Kirsner, and their colleagues treated a large, chronic venous leg ulcer, almost 60 cm2, with punch grafts from a variety of donor sites.

“The side that got scalp punch grafts healed better, suggesting with skin taken from richly hairy area, you’ll get better results,” Dr. Kirsner said.

Another study supports this strategy (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75[5]:1007-14). These researchers reported greater wound size reduction using grafts containing hair follicles versus nonhairy areas, again suggesting follicular stem cells play a role in better wound healing, Dr. Kirsner said. “This may be a better source of donor skin in the future.”

Dr. Kirsner is a consultant for Cardinal Health, Mölnlycke, Amniox, Organogenesis, Kerecis, Keretec, and KCI, an Acelity company.

MIAMI – Pinch grafting can accelerate the healing of chronic, treatment-resistant wounds such as leg ulcers, while at the same time reducing morbidity to the donor skin site. A new epidermal harvesting device also is showing promise, as is a new tool that minces autologous skin grafts prior to application to promote wound healing.

These and other advances in wound healing were presented at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. The pinch grafts and minced grafts each rely on the newly added skin to stimulate cytokines. Interestingly, there is evidence that grafts taken from hair-bearing donor sites could be superior for stimulating cytokines and accelerating wound healing, said Robert Kirsner, MD, PhD, of the University of Miami Health System.

Islands of regrowth

Physicians perform pinch grafting by taking small punches of skin from a donor site on the thigh, abdomen, or elsewhere, and then transferring the grafts to serve as islands of regrowth in a wound. Pinch grafting can be faster and less expensive than techniques typically performed in an operating room, such as meshed auto-grafting. In contrast, pinch grafting can be accomplished in an office setting “and patients can do quite well.” Dr. Kirsner said. In terms of outcomes, “our data is typical,” he added. “About 50% of refractory ulcers heal, 25% improve, and a percentage recur.”

Spreadable skin grafts

Another autologous grafting technique that can be performed at the bedside uses the Xpansion Micro-Autografting Kit, which minces autologous, split thickness skin grafts. “Then you apply them like peanut butter to bread,” Dr. Kirsner said.

The micro-autografts can help heal both acute and chronic wounds, including full thickness wounds from trauma, some burn wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, and venous ulcers, according to the manufacturer’s website.

Epidermal harvesting (without anesthesia)

Epidermal grafting can make sense because the epidermis regenerates. “You can lift off just the epidermis with heat or suction, “ Dr. Kirsner said. For the first time, he added, a new tool allows epidermal grafting without the need for anesthesia (Cellutome Epidermal Harvesting System). The device raises little microdomes of epidermis down to the basal layer, including basal keratinocytes and melanocytes, and a dermatologist can use a sterile dressing to transfer them to the wound. Confocal microscopy shows the dermoepidermal junction healing as early as within 2 days.

The epidermal harvesting was initially developed for pigment problems, such as piebaldism. (Dermatol Surg. 2017 Jan;43[1]:159-60). “We quickly realized it might have applicability for nonhealing wounds,” Dr. Kirsner said.

Deeper wound healing

A novel strategy for triggering deeper wound healing evolved from fractional laser technology, which remove columns of skin to generate healing. Instead, Rox Anderson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, “envisioned pulling up microcolumns of full thickness epidermis, all the way to the fat, placing them into a wound, and the wound would heal with very little donor site morbidity,” Dr. Kirsner said.

This tool is coming out in spring of this year, he noted. It will resemble a fractional laser, “but now you have the skin available to place in another wound.” Prior animal studies revealed a healing benefit with very little scarring, he added.

Is hairier better?

Does the donor site matter? Dr. Kirsner asked. Although dermatologists typically graft skin from an abdomen or thigh, a hair-bearing site may be a better option because of the presence of pluripotent stem cells, according to a case report (Wounds. 2016 Apr;28[4]:109-11). J.D. Fox of the University of Miami, Dr. Kirsner, and their colleagues treated a large, chronic venous leg ulcer, almost 60 cm2, with punch grafts from a variety of donor sites.

“The side that got scalp punch grafts healed better, suggesting with skin taken from richly hairy area, you’ll get better results,” Dr. Kirsner said.

Another study supports this strategy (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75[5]:1007-14). These researchers reported greater wound size reduction using grafts containing hair follicles versus nonhairy areas, again suggesting follicular stem cells play a role in better wound healing, Dr. Kirsner said. “This may be a better source of donor skin in the future.”

Dr. Kirsner is a consultant for Cardinal Health, Mölnlycke, Amniox, Organogenesis, Kerecis, Keretec, and KCI, an Acelity company.

Healing of Leg Ulcers Associated With Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Wegener Granulomatosis) After Rituximab Therapy

To the Editor:

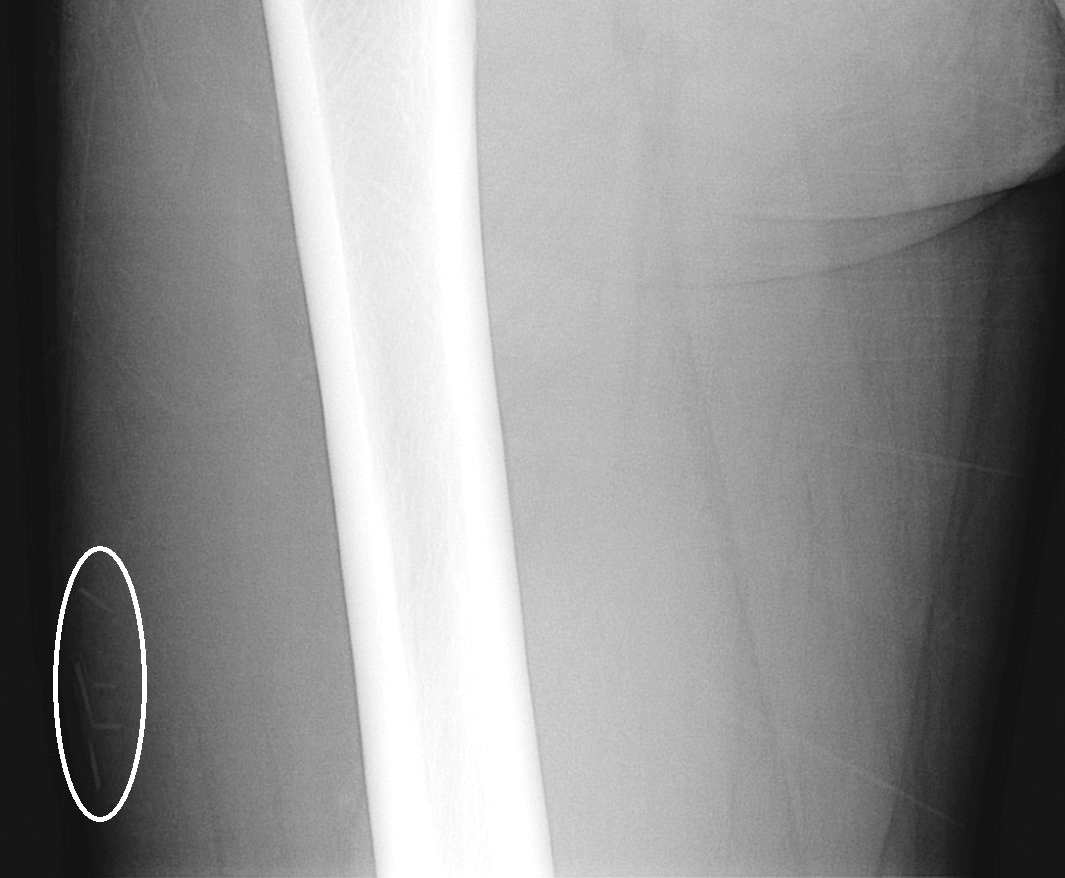

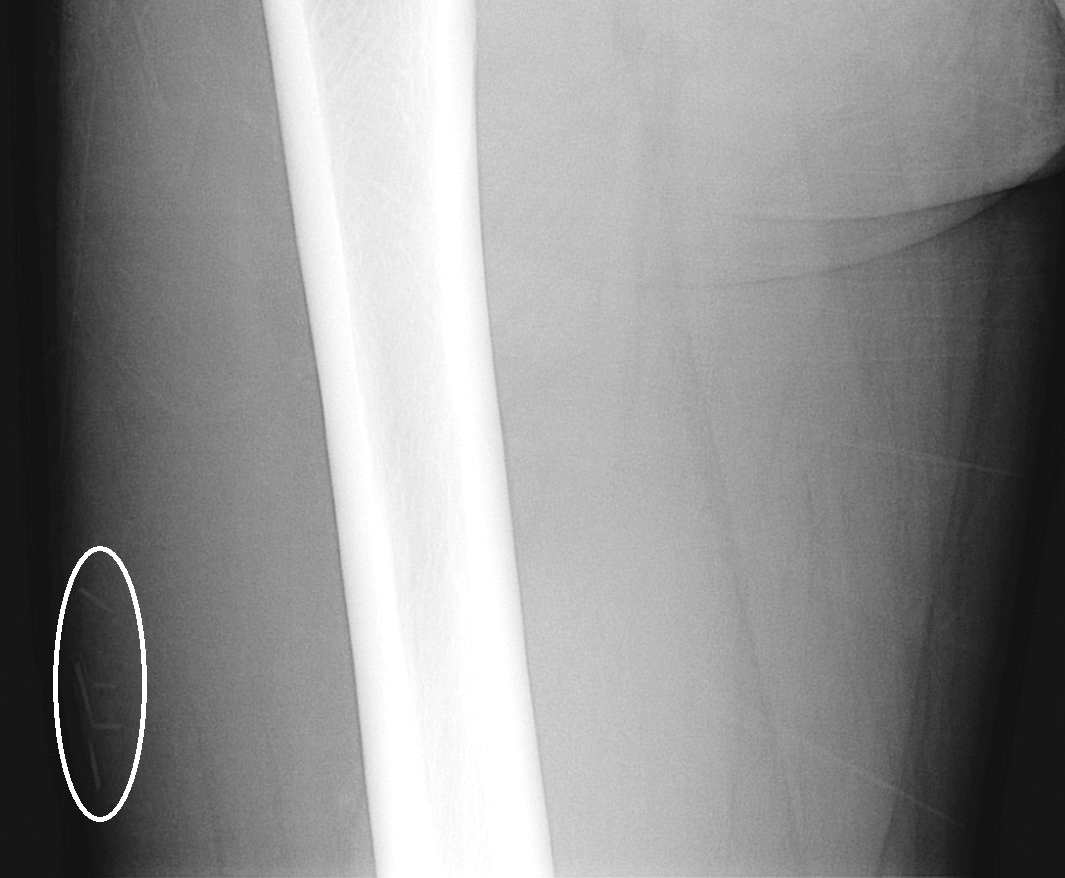

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

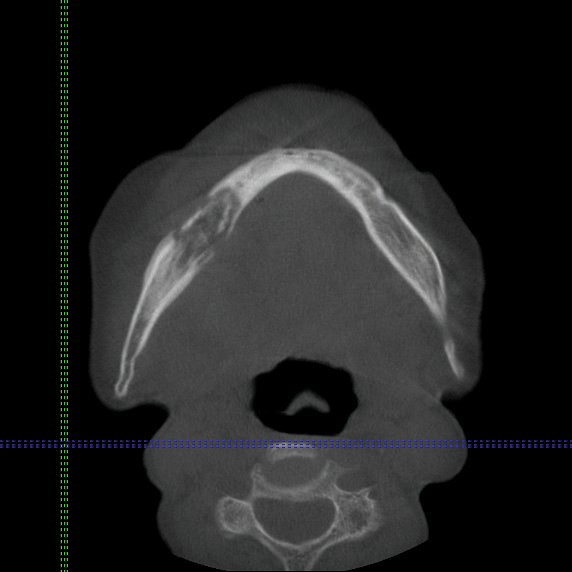

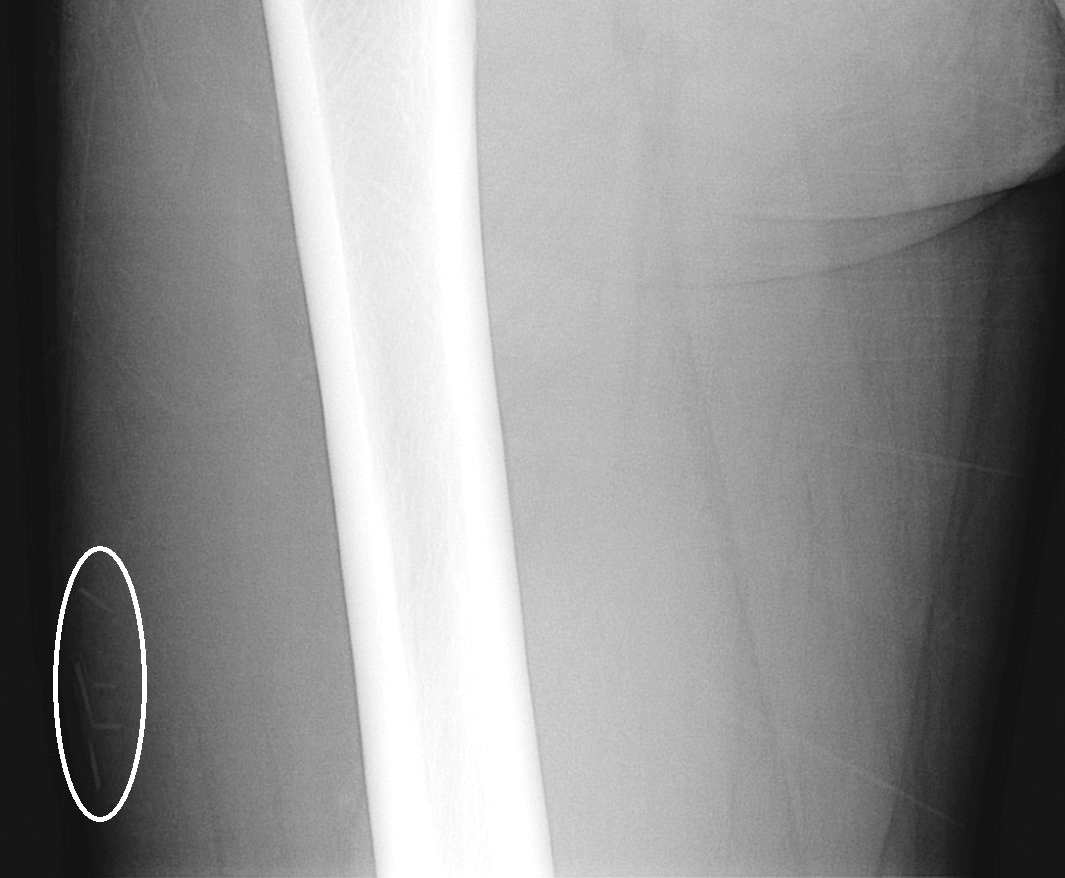

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4

The success of RTX in treating GPA has been documented in case reports as well as several trials with extended follow-up. A single-center observational study of 53 patients showed that RTX was safe and effective for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with refractory GPA. This study also uncovered the potential for predicting relapse based on following B cell and ANCA levels and preventing relapse by initializing further treatment.5 Other small studies and case reports have shown similar success using RTX for refractory GPA.6-10 These studies included various combinations of concurrent therapies and various follow-up intervals. The Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial compared RTX versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-positive vasculitis.11 This multicenter, randomized, double-blind study found that RTX was as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in severe GPA.The data also suggested that RTX may be superior for relapsing disease.11 Another multicenter, open-label, randomized trial (RITUXVAS) compared RTX to cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. This trial also found the 2 treatments to be similar in both efficacy in inducing remission and adverse events.12

Some conflicting reports have appeared on the effectiveness of using RTX for the granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations of GPA. Aires et al13 showed failure of improvement in most patients with granulomatous manifestations of GPA in a study of 8 patients. A retrospective study including 59 patients who were treated with RTX also showed that complete remission was more common in patients with primarily vasculitic manifestations, not granulomatous manifestations.14 However, some case series that included patients with refractory ophthalmic GPA, a primarily granulomatous manifestation, have found success using RTX.15,16 More studies are needed to determine if there truly is a difference and whether this difference has an effect on when to use RTX. The skin lesions our patient demonstrated were due to the vasculitic component of the disease, and consequently, the rapid and complete response we observed would be consistent with the premise that the therapy works best for vasculitis.

Most of the trials assessing the efficacy of RTX utilize a tool such as the Wegener granulomatosis-specific Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.17 This measure of treatment response does include a skin item, but it is part of the composite response score. Consequently, a specific statement regarding skin improvement cannot be made. Additionally, little is reported pertaining to the treatment of skin-related findings in GPA. One report did specifically address the treatment of dermatologic manifestations of GPA utilizing systemic tacrolimus with oral prednisone successfully in 1 patient with GPA and a history of recurrent lower extremity nodules and ulcers.18 The efficacy of RTX in limited GPA was good in a small study of 8 patients. However, the study had only 1 patient with purpura and 1 patient with a subcutaneous nodule.19 Several other case series and studies have included patients with various cutaneous findings associated with GPA.5-7,9,11 However, they did not comment specifically on skin response to treatment, and the focus appeared to be on other organ system involvement. One case series did report improvement of lower extremity gangrene with RTX therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.8 Our report demonstrates a case of severe skin disease that responded well to RTX. It is common to have various skin findings in GPA, and our patient presented with notable skin disease. Although skin findings may not be the more life-threatening manifestations of the disease, they can be quite debilitating, as shown in our case report.

Our patient with notable leg ulcerations required hospitalization due to GPA and received RTX in addition to corticosteroids for treatment. We observed a rapid and dramatic improvement in the skin findings, which seemed to exceed expectations from steroids alone. The other manifestations of the disease including lung nodules also improved. Although cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids have been quite successful in induction of remission, cyclophosphamide is not without serious adverse effects. There also are some patients who have contraindications to cyclophosphamide or do not see successful results. In our brief review of the literature, RTX, a B cell–depleting antibody, has shown to have success in treating refractory and severe GPA. There is little reported specifically about treating the skin manifestations of GPA. A few studies and case reports mention skin findings but do not comment on the success of RTX in treating them. Although the severity of other organ involvement in GPA may take precedence, the skin findings can be quite debilitating, as in our patient. Patients with GPA and notable skin findings may benefit from RTX, and it would be beneficial to include these results in future studies using RTX to treat GPA.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Plosker GL, Figgitt DP. Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003;63:803-843.

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806.

- FDA approves Rituxan to treat two rare disorders [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 19, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm251946.htm. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Golbin JM, Keogh KA, et al. Rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): ten-year experience at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3770-3778.

- Keogh KA, Ytterberg SR, Fervenza FC, et al. Rituximab for refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:180-187.

- Dalkilic E, Alkis N, Kamali S. Rituximab as a new therapeutic option in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a report of two cases. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:463-466.

- Eriksson P. Nine patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis successfully treated with rituximab. J Intern Med. 2005;257:540-548.

- Oristrell J, Bejarano G, Jordana R, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab in severe Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Open Respir Med J. 2009;3:94-99.

- Martinez Del Pero M, Chaudhry A, Jones RB, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab for refractory head and neck Wegener’s granulomatosis: a cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:328-335.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221-232.

- Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:211-220.

- Aries PM, Hellmich B, Voswinkel J, et al. Lack of efficacy of rituximab in Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:853-858.

- Holle JU, Dubrau C, Herlyn K, et al. Rituximab for refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis): comparison of efficacy in granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:327-333.

- Taylor SR, Salama AD, Joshi L, et al. Rituximab is effective in the treatment of refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1540-1547.

- Joshi L, Lightman SL, Salama AD, et al. Rituximab in refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis: PR3 titers may predict relapse, but repeat treatment can be effective. Ophthalmol. 2011;118:2498-2503.

- Stone JH, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, et al. A disease-specific activity index for Wegener’s granulomatosis: modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:912-920.

- Wenzel J, Montag S, Wilsmann-Theis D, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant Wegener’s granulomatosis of the skin with tacrolimus (Prograf). Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:927-928.

- Seo P, Specks U, Keogh KA. Efficacy of rituximab in limited Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2017-2023.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

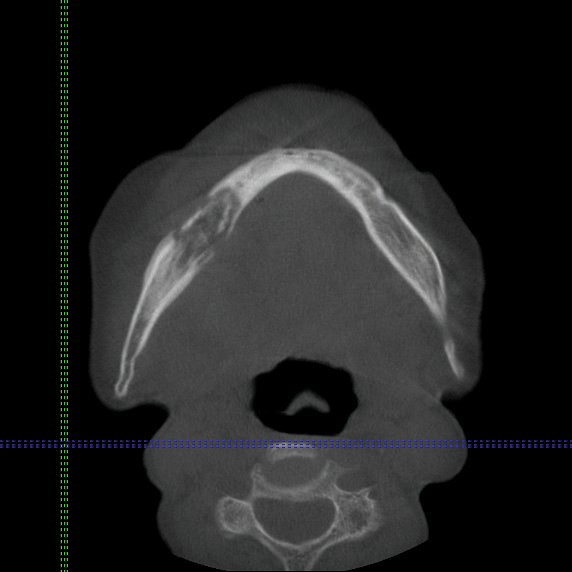

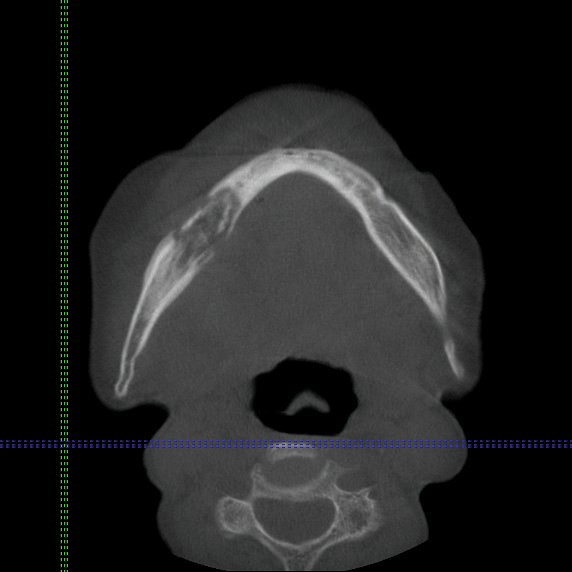

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4

The success of RTX in treating GPA has been documented in case reports as well as several trials with extended follow-up. A single-center observational study of 53 patients showed that RTX was safe and effective for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with refractory GPA. This study also uncovered the potential for predicting relapse based on following B cell and ANCA levels and preventing relapse by initializing further treatment.5 Other small studies and case reports have shown similar success using RTX for refractory GPA.6-10 These studies included various combinations of concurrent therapies and various follow-up intervals. The Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial compared RTX versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-positive vasculitis.11 This multicenter, randomized, double-blind study found that RTX was as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in severe GPA.The data also suggested that RTX may be superior for relapsing disease.11 Another multicenter, open-label, randomized trial (RITUXVAS) compared RTX to cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. This trial also found the 2 treatments to be similar in both efficacy in inducing remission and adverse events.12

Some conflicting reports have appeared on the effectiveness of using RTX for the granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations of GPA. Aires et al13 showed failure of improvement in most patients with granulomatous manifestations of GPA in a study of 8 patients. A retrospective study including 59 patients who were treated with RTX also showed that complete remission was more common in patients with primarily vasculitic manifestations, not granulomatous manifestations.14 However, some case series that included patients with refractory ophthalmic GPA, a primarily granulomatous manifestation, have found success using RTX.15,16 More studies are needed to determine if there truly is a difference and whether this difference has an effect on when to use RTX. The skin lesions our patient demonstrated were due to the vasculitic component of the disease, and consequently, the rapid and complete response we observed would be consistent with the premise that the therapy works best for vasculitis.

Most of the trials assessing the efficacy of RTX utilize a tool such as the Wegener granulomatosis-specific Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.17 This measure of treatment response does include a skin item, but it is part of the composite response score. Consequently, a specific statement regarding skin improvement cannot be made. Additionally, little is reported pertaining to the treatment of skin-related findings in GPA. One report did specifically address the treatment of dermatologic manifestations of GPA utilizing systemic tacrolimus with oral prednisone successfully in 1 patient with GPA and a history of recurrent lower extremity nodules and ulcers.18 The efficacy of RTX in limited GPA was good in a small study of 8 patients. However, the study had only 1 patient with purpura and 1 patient with a subcutaneous nodule.19 Several other case series and studies have included patients with various cutaneous findings associated with GPA.5-7,9,11 However, they did not comment specifically on skin response to treatment, and the focus appeared to be on other organ system involvement. One case series did report improvement of lower extremity gangrene with RTX therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.8 Our report demonstrates a case of severe skin disease that responded well to RTX. It is common to have various skin findings in GPA, and our patient presented with notable skin disease. Although skin findings may not be the more life-threatening manifestations of the disease, they can be quite debilitating, as shown in our case report.

Our patient with notable leg ulcerations required hospitalization due to GPA and received RTX in addition to corticosteroids for treatment. We observed a rapid and dramatic improvement in the skin findings, which seemed to exceed expectations from steroids alone. The other manifestations of the disease including lung nodules also improved. Although cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids have been quite successful in induction of remission, cyclophosphamide is not without serious adverse effects. There also are some patients who have contraindications to cyclophosphamide or do not see successful results. In our brief review of the literature, RTX, a B cell–depleting antibody, has shown to have success in treating refractory and severe GPA. There is little reported specifically about treating the skin manifestations of GPA. A few studies and case reports mention skin findings but do not comment on the success of RTX in treating them. Although the severity of other organ involvement in GPA may take precedence, the skin findings can be quite debilitating, as in our patient. Patients with GPA and notable skin findings may benefit from RTX, and it would be beneficial to include these results in future studies using RTX to treat GPA.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4

The success of RTX in treating GPA has been documented in case reports as well as several trials with extended follow-up. A single-center observational study of 53 patients showed that RTX was safe and effective for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with refractory GPA. This study also uncovered the potential for predicting relapse based on following B cell and ANCA levels and preventing relapse by initializing further treatment.5 Other small studies and case reports have shown similar success using RTX for refractory GPA.6-10 These studies included various combinations of concurrent therapies and various follow-up intervals. The Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial compared RTX versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-positive vasculitis.11 This multicenter, randomized, double-blind study found that RTX was as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in severe GPA.The data also suggested that RTX may be superior for relapsing disease.11 Another multicenter, open-label, randomized trial (RITUXVAS) compared RTX to cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. This trial also found the 2 treatments to be similar in both efficacy in inducing remission and adverse events.12

Some conflicting reports have appeared on the effectiveness of using RTX for the granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations of GPA. Aires et al13 showed failure of improvement in most patients with granulomatous manifestations of GPA in a study of 8 patients. A retrospective study including 59 patients who were treated with RTX also showed that complete remission was more common in patients with primarily vasculitic manifestations, not granulomatous manifestations.14 However, some case series that included patients with refractory ophthalmic GPA, a primarily granulomatous manifestation, have found success using RTX.15,16 More studies are needed to determine if there truly is a difference and whether this difference has an effect on when to use RTX. The skin lesions our patient demonstrated were due to the vasculitic component of the disease, and consequently, the rapid and complete response we observed would be consistent with the premise that the therapy works best for vasculitis.

Most of the trials assessing the efficacy of RTX utilize a tool such as the Wegener granulomatosis-specific Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.17 This measure of treatment response does include a skin item, but it is part of the composite response score. Consequently, a specific statement regarding skin improvement cannot be made. Additionally, little is reported pertaining to the treatment of skin-related findings in GPA. One report did specifically address the treatment of dermatologic manifestations of GPA utilizing systemic tacrolimus with oral prednisone successfully in 1 patient with GPA and a history of recurrent lower extremity nodules and ulcers.18 The efficacy of RTX in limited GPA was good in a small study of 8 patients. However, the study had only 1 patient with purpura and 1 patient with a subcutaneous nodule.19 Several other case series and studies have included patients with various cutaneous findings associated with GPA.5-7,9,11 However, they did not comment specifically on skin response to treatment, and the focus appeared to be on other organ system involvement. One case series did report improvement of lower extremity gangrene with RTX therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.8 Our report demonstrates a case of severe skin disease that responded well to RTX. It is common to have various skin findings in GPA, and our patient presented with notable skin disease. Although skin findings may not be the more life-threatening manifestations of the disease, they can be quite debilitating, as shown in our case report.

Our patient with notable leg ulcerations required hospitalization due to GPA and received RTX in addition to corticosteroids for treatment. We observed a rapid and dramatic improvement in the skin findings, which seemed to exceed expectations from steroids alone. The other manifestations of the disease including lung nodules also improved. Although cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids have been quite successful in induction of remission, cyclophosphamide is not without serious adverse effects. There also are some patients who have contraindications to cyclophosphamide or do not see successful results. In our brief review of the literature, RTX, a B cell–depleting antibody, has shown to have success in treating refractory and severe GPA. There is little reported specifically about treating the skin manifestations of GPA. A few studies and case reports mention skin findings but do not comment on the success of RTX in treating them. Although the severity of other organ involvement in GPA may take precedence, the skin findings can be quite debilitating, as in our patient. Patients with GPA and notable skin findings may benefit from RTX, and it would be beneficial to include these results in future studies using RTX to treat GPA.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Plosker GL, Figgitt DP. Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003;63:803-843.

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806.

- FDA approves Rituxan to treat two rare disorders [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 19, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm251946.htm. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Golbin JM, Keogh KA, et al. Rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): ten-year experience at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3770-3778.

- Keogh KA, Ytterberg SR, Fervenza FC, et al. Rituximab for refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:180-187.

- Dalkilic E, Alkis N, Kamali S. Rituximab as a new therapeutic option in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a report of two cases. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:463-466.

- Eriksson P. Nine patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis successfully treated with rituximab. J Intern Med. 2005;257:540-548.