User login

An Unusual Metastasis of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Background

Anal squamous cell carcinoma is a rare cancer which usually has locoregional spread. We report a case of distant metastasis of primary anal squamous cell carcinoma to the posterior mediastinal lymph node without lung involvement.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old female presented with a painful anal mass, bleeding, and fluid leakage for around six months. The patient was found to have a near-circumferential fungating anal mass with bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. MR imaging revealed an 8.7 x 5.9 cm anal mass extending beyond the mesorectal fascia, with lymphadenopathy involving inguinal, pelvic sidewall, and iliac regions. A biopsy of the mass confirmed anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC). Initial treatment included diverting colostomy followed by definitive chemoradiotherapy with Mitomycin and 5-Fluorouracil. Colonoscopy post-treatment revealed tubular adenomas and a hyperplastic polyp, with no malignancy detected. The patient demonstrated a strong therapeutic response, with resolution of the anal mass and improved symptoms. However, one year later, new FDG-avid mediastinal lymph node were detected on the CT/PET scan with no pulmonary involvement. Metastatic ASCC of the Mediastinal lymph node was confirmed by biopsy. Salvage chemotherapy with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel every three weeks for six cycles achieved complete resolution of metastases.

Conclusions

This case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing advanced ASCC and highlights the efficacy of salvage chemotherapy in addressing metastases. Close monitoring of disease progression following surgery and chemotherapy is crucial due to the risk of recurrence.

Background

Anal squamous cell carcinoma is a rare cancer which usually has locoregional spread. We report a case of distant metastasis of primary anal squamous cell carcinoma to the posterior mediastinal lymph node without lung involvement.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old female presented with a painful anal mass, bleeding, and fluid leakage for around six months. The patient was found to have a near-circumferential fungating anal mass with bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. MR imaging revealed an 8.7 x 5.9 cm anal mass extending beyond the mesorectal fascia, with lymphadenopathy involving inguinal, pelvic sidewall, and iliac regions. A biopsy of the mass confirmed anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC). Initial treatment included diverting colostomy followed by definitive chemoradiotherapy with Mitomycin and 5-Fluorouracil. Colonoscopy post-treatment revealed tubular adenomas and a hyperplastic polyp, with no malignancy detected. The patient demonstrated a strong therapeutic response, with resolution of the anal mass and improved symptoms. However, one year later, new FDG-avid mediastinal lymph node were detected on the CT/PET scan with no pulmonary involvement. Metastatic ASCC of the Mediastinal lymph node was confirmed by biopsy. Salvage chemotherapy with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel every three weeks for six cycles achieved complete resolution of metastases.

Conclusions

This case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing advanced ASCC and highlights the efficacy of salvage chemotherapy in addressing metastases. Close monitoring of disease progression following surgery and chemotherapy is crucial due to the risk of recurrence.

Background

Anal squamous cell carcinoma is a rare cancer which usually has locoregional spread. We report a case of distant metastasis of primary anal squamous cell carcinoma to the posterior mediastinal lymph node without lung involvement.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old female presented with a painful anal mass, bleeding, and fluid leakage for around six months. The patient was found to have a near-circumferential fungating anal mass with bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. MR imaging revealed an 8.7 x 5.9 cm anal mass extending beyond the mesorectal fascia, with lymphadenopathy involving inguinal, pelvic sidewall, and iliac regions. A biopsy of the mass confirmed anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC). Initial treatment included diverting colostomy followed by definitive chemoradiotherapy with Mitomycin and 5-Fluorouracil. Colonoscopy post-treatment revealed tubular adenomas and a hyperplastic polyp, with no malignancy detected. The patient demonstrated a strong therapeutic response, with resolution of the anal mass and improved symptoms. However, one year later, new FDG-avid mediastinal lymph node were detected on the CT/PET scan with no pulmonary involvement. Metastatic ASCC of the Mediastinal lymph node was confirmed by biopsy. Salvage chemotherapy with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel every three weeks for six cycles achieved complete resolution of metastases.

Conclusions

This case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing advanced ASCC and highlights the efficacy of salvage chemotherapy in addressing metastases. Close monitoring of disease progression following surgery and chemotherapy is crucial due to the risk of recurrence.

Walking the Line: Balancing Autonomy and Safety at End-of-Life

Background

The goal of hospice and palliative care is to provide comfort and dignity for individuals by honoring autonomy and patient preferences at endof- life. These standards can be difficult to balance when concerns around decision-making capacity and safety arise. The Veteran’s Health Administration has numerous resources to support interdisciplinary teams. We present a case study highlighting conflict between these ethical principles

Case Presentation

Veteran is a 66-year-old male with metastatic neuroendocrine cancer to brain and co-occurring polysubstance use disorder. Veteran agreed to VA inpatient hospice due to functional decline and limited social support at home. Day passes were initially allowed but later restricted due to multiple safety concerns surrounding mental status, smoking on campus and unauthorized passes. Behaviors escalated and veteran removed secure care monitor, left the unit without notifying staff, and erratically drove off campus prompting local police involvement.

Discussion

Patient demonstrated a preference to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in person, to use his vehicle and to live at home. Given the complexity of this case, we turned to the National Center for Ethics in Health Care for input. This included guidance about legal and ethical limitations and recommendations for ongoing assessment and documentation of decisionmaking capacity and use of a surrogate.

Results

As veteran’s mental status declined, veteran no longer demonstrated the capacity to understand the safety risks of driving or living at home. His sister served as his health care agent and was opposed to home discharge due to safety concerns. The interdisciplinary team attempted to focus on respecting veteran’s dignity and autonomy as veteran approached end-oflife. Conflicts arose between the ethical pillars of autonomy, non-maleficence, community safety, and legal risks to institution. Lessons learned included the importance of daily safety huddles, ensuring secure care system functions properly, performing ongoing capacity assessments, and improving pre-admission screening.

Conclusions

Balancing autonomy and patient prefpreferences in VA hospice care demands continuous evaluation and adjustment of care plans. Legal and institutional ethics can be consulted to assist providers in formulating optimal plans and to guide use of ethical pillars within the VA framework.

Background

The goal of hospice and palliative care is to provide comfort and dignity for individuals by honoring autonomy and patient preferences at endof- life. These standards can be difficult to balance when concerns around decision-making capacity and safety arise. The Veteran’s Health Administration has numerous resources to support interdisciplinary teams. We present a case study highlighting conflict between these ethical principles

Case Presentation

Veteran is a 66-year-old male with metastatic neuroendocrine cancer to brain and co-occurring polysubstance use disorder. Veteran agreed to VA inpatient hospice due to functional decline and limited social support at home. Day passes were initially allowed but later restricted due to multiple safety concerns surrounding mental status, smoking on campus and unauthorized passes. Behaviors escalated and veteran removed secure care monitor, left the unit without notifying staff, and erratically drove off campus prompting local police involvement.

Discussion

Patient demonstrated a preference to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in person, to use his vehicle and to live at home. Given the complexity of this case, we turned to the National Center for Ethics in Health Care for input. This included guidance about legal and ethical limitations and recommendations for ongoing assessment and documentation of decisionmaking capacity and use of a surrogate.

Results

As veteran’s mental status declined, veteran no longer demonstrated the capacity to understand the safety risks of driving or living at home. His sister served as his health care agent and was opposed to home discharge due to safety concerns. The interdisciplinary team attempted to focus on respecting veteran’s dignity and autonomy as veteran approached end-oflife. Conflicts arose between the ethical pillars of autonomy, non-maleficence, community safety, and legal risks to institution. Lessons learned included the importance of daily safety huddles, ensuring secure care system functions properly, performing ongoing capacity assessments, and improving pre-admission screening.

Conclusions

Balancing autonomy and patient prefpreferences in VA hospice care demands continuous evaluation and adjustment of care plans. Legal and institutional ethics can be consulted to assist providers in formulating optimal plans and to guide use of ethical pillars within the VA framework.

Background

The goal of hospice and palliative care is to provide comfort and dignity for individuals by honoring autonomy and patient preferences at endof- life. These standards can be difficult to balance when concerns around decision-making capacity and safety arise. The Veteran’s Health Administration has numerous resources to support interdisciplinary teams. We present a case study highlighting conflict between these ethical principles

Case Presentation

Veteran is a 66-year-old male with metastatic neuroendocrine cancer to brain and co-occurring polysubstance use disorder. Veteran agreed to VA inpatient hospice due to functional decline and limited social support at home. Day passes were initially allowed but later restricted due to multiple safety concerns surrounding mental status, smoking on campus and unauthorized passes. Behaviors escalated and veteran removed secure care monitor, left the unit without notifying staff, and erratically drove off campus prompting local police involvement.

Discussion

Patient demonstrated a preference to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in person, to use his vehicle and to live at home. Given the complexity of this case, we turned to the National Center for Ethics in Health Care for input. This included guidance about legal and ethical limitations and recommendations for ongoing assessment and documentation of decisionmaking capacity and use of a surrogate.

Results

As veteran’s mental status declined, veteran no longer demonstrated the capacity to understand the safety risks of driving or living at home. His sister served as his health care agent and was opposed to home discharge due to safety concerns. The interdisciplinary team attempted to focus on respecting veteran’s dignity and autonomy as veteran approached end-oflife. Conflicts arose between the ethical pillars of autonomy, non-maleficence, community safety, and legal risks to institution. Lessons learned included the importance of daily safety huddles, ensuring secure care system functions properly, performing ongoing capacity assessments, and improving pre-admission screening.

Conclusions

Balancing autonomy and patient prefpreferences in VA hospice care demands continuous evaluation and adjustment of care plans. Legal and institutional ethics can be consulted to assist providers in formulating optimal plans and to guide use of ethical pillars within the VA framework.

Successful Targeted Therapy with Alectinib in ALK-Positive Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

Background

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates due to its typical late-stage diagnosis and subsequent limited surgical options. However, recent advances in molecular profiling offer hope for targeted therapies. We present a case of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma which progressed despite surgery and chemotherapy yet showed a positive respond to Alectinib.

Case Description

A 79-year-old male with medical history of tobacco use and ulcerative colitis presented to the clinic with 15lb unintentional weight loss over the past few months in 04/2021. Computed tomography (CT) showed dilated common bile duct due to 2.2 x 1.9 x 1.7 cm mass with no metastatic disease. Biopsy was consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient completed 6 cycles of dose-reduced neoadjuvant gemcitabine and paclitaxel in late 2021 due to his severe neuropathy and ECOG. Subsequent CT and PET-CT showed stable disease prior to undergoing pylorus-sparing pancreatoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy with portal vein resection in 05/2022 with surgical pathology grading yPT4N2cM0. The follow- up PET scan in 09/2022 revealed new pulmonary and liver metastases, along with increased uptake in the pancreatic region, suggesting recurrent disease. Next generation sequencing (NGS) identified an ELM4-ALK chromosomal rearrangement on the surgical pathology. Given the patient’s cancer progression and concerns about chemotherapy tolerance, Alectinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor more commonly used in lung cancer, was considered as a treatment option. Patient began Alectinib 10/2022 with no significant side effects and PET scan on 03/2023 and 06/2023 showing resolution of his lung nodules and liver lesions. Patient remained on Alectinib until he transitioned to hospice after an ischemic stroke in 03/2024.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer urgently requires novel therapies as about 25% of patients harbor actionable molecular alterations that have led to the success of targeted therapies. ALK fusion genes are identified in multiple cancers, but the prevalence is only 0.16% in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Alectinib provided an extended progression free survival compared with standard chemotherapy in our patient. ALK inhibitors may demonstrate a remarkable response in metastatic pancreatic cancer even in poor candidates for standard chemotherapy highlighting the emphasis of NGS and targeted therapy options for pancreatic cancer to improve survival.

Background

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates due to its typical late-stage diagnosis and subsequent limited surgical options. However, recent advances in molecular profiling offer hope for targeted therapies. We present a case of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma which progressed despite surgery and chemotherapy yet showed a positive respond to Alectinib.

Case Description

A 79-year-old male with medical history of tobacco use and ulcerative colitis presented to the clinic with 15lb unintentional weight loss over the past few months in 04/2021. Computed tomography (CT) showed dilated common bile duct due to 2.2 x 1.9 x 1.7 cm mass with no metastatic disease. Biopsy was consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient completed 6 cycles of dose-reduced neoadjuvant gemcitabine and paclitaxel in late 2021 due to his severe neuropathy and ECOG. Subsequent CT and PET-CT showed stable disease prior to undergoing pylorus-sparing pancreatoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy with portal vein resection in 05/2022 with surgical pathology grading yPT4N2cM0. The follow- up PET scan in 09/2022 revealed new pulmonary and liver metastases, along with increased uptake in the pancreatic region, suggesting recurrent disease. Next generation sequencing (NGS) identified an ELM4-ALK chromosomal rearrangement on the surgical pathology. Given the patient’s cancer progression and concerns about chemotherapy tolerance, Alectinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor more commonly used in lung cancer, was considered as a treatment option. Patient began Alectinib 10/2022 with no significant side effects and PET scan on 03/2023 and 06/2023 showing resolution of his lung nodules and liver lesions. Patient remained on Alectinib until he transitioned to hospice after an ischemic stroke in 03/2024.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer urgently requires novel therapies as about 25% of patients harbor actionable molecular alterations that have led to the success of targeted therapies. ALK fusion genes are identified in multiple cancers, but the prevalence is only 0.16% in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Alectinib provided an extended progression free survival compared with standard chemotherapy in our patient. ALK inhibitors may demonstrate a remarkable response in metastatic pancreatic cancer even in poor candidates for standard chemotherapy highlighting the emphasis of NGS and targeted therapy options for pancreatic cancer to improve survival.

Background

Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates due to its typical late-stage diagnosis and subsequent limited surgical options. However, recent advances in molecular profiling offer hope for targeted therapies. We present a case of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma which progressed despite surgery and chemotherapy yet showed a positive respond to Alectinib.

Case Description

A 79-year-old male with medical history of tobacco use and ulcerative colitis presented to the clinic with 15lb unintentional weight loss over the past few months in 04/2021. Computed tomography (CT) showed dilated common bile duct due to 2.2 x 1.9 x 1.7 cm mass with no metastatic disease. Biopsy was consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient completed 6 cycles of dose-reduced neoadjuvant gemcitabine and paclitaxel in late 2021 due to his severe neuropathy and ECOG. Subsequent CT and PET-CT showed stable disease prior to undergoing pylorus-sparing pancreatoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy with portal vein resection in 05/2022 with surgical pathology grading yPT4N2cM0. The follow- up PET scan in 09/2022 revealed new pulmonary and liver metastases, along with increased uptake in the pancreatic region, suggesting recurrent disease. Next generation sequencing (NGS) identified an ELM4-ALK chromosomal rearrangement on the surgical pathology. Given the patient’s cancer progression and concerns about chemotherapy tolerance, Alectinib, a second-generation ALK inhibitor more commonly used in lung cancer, was considered as a treatment option. Patient began Alectinib 10/2022 with no significant side effects and PET scan on 03/2023 and 06/2023 showing resolution of his lung nodules and liver lesions. Patient remained on Alectinib until he transitioned to hospice after an ischemic stroke in 03/2024.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer urgently requires novel therapies as about 25% of patients harbor actionable molecular alterations that have led to the success of targeted therapies. ALK fusion genes are identified in multiple cancers, but the prevalence is only 0.16% in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Alectinib provided an extended progression free survival compared with standard chemotherapy in our patient. ALK inhibitors may demonstrate a remarkable response in metastatic pancreatic cancer even in poor candidates for standard chemotherapy highlighting the emphasis of NGS and targeted therapy options for pancreatic cancer to improve survival.

Lung Cancer Exposome in U.S. Military Veterans: Study of Environment and Epigenetic Factors on Risk and Survival

Background

The Exposome—the comprehensive accumulation of environmental exposures from birth to death—provides a framework for linking external risk factors to cancer biology. In U.S. veterans, the exposome includes both military-specific exposures (e.g., asbestos, Agent Orange, burn pits) and postservice socioeconomic and environmental factors. These cumulative exposures may drive tumor development and progression via epigenetic mechanisms, though their impact on lung cancer outcomes remain poorly characterized.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of 71 lung cancer subjects (NSCLC and SCLC) from the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center (IRB# 1586320). We assessed the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), Environmental Burden Index (EBI), and occupational exposure in relation to DNA methylation of CDO1, TAC1, SOX17, and HOXA7. Geospatial data were mapped to US census tracts, and standard statistical analysis were conducted.

Results

NSCLC patients exhibited significantly higher methylation levels across all genes. High EBI exposure was associated with lower SOX17 methylation (p = 0.064) and worse overall survival (p = 0.046). In NSCLC patients, occupational exposure predicted a 7.7-fold increased hazard of death (p = 0.027). SOX17 and TAC1 methylation were independently associated with reduced survival (p = 0.037 and 0.0058, respectively). While ADI did not independently predict survival, it correlated with late-stage presentation and reduced HOXA7 methylation.

Conclusions

Exposome factors such as environmental burden and occupational exposure are biologically embedded in lung cancer cell through gene-specific methylation and significantly impact survival. We posit that integrating exposomic and molecular data could enhance lung precision oncology approaches for high-risk veteran populations.

Background

The Exposome—the comprehensive accumulation of environmental exposures from birth to death—provides a framework for linking external risk factors to cancer biology. In U.S. veterans, the exposome includes both military-specific exposures (e.g., asbestos, Agent Orange, burn pits) and postservice socioeconomic and environmental factors. These cumulative exposures may drive tumor development and progression via epigenetic mechanisms, though their impact on lung cancer outcomes remain poorly characterized.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of 71 lung cancer subjects (NSCLC and SCLC) from the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center (IRB# 1586320). We assessed the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), Environmental Burden Index (EBI), and occupational exposure in relation to DNA methylation of CDO1, TAC1, SOX17, and HOXA7. Geospatial data were mapped to US census tracts, and standard statistical analysis were conducted.

Results

NSCLC patients exhibited significantly higher methylation levels across all genes. High EBI exposure was associated with lower SOX17 methylation (p = 0.064) and worse overall survival (p = 0.046). In NSCLC patients, occupational exposure predicted a 7.7-fold increased hazard of death (p = 0.027). SOX17 and TAC1 methylation were independently associated with reduced survival (p = 0.037 and 0.0058, respectively). While ADI did not independently predict survival, it correlated with late-stage presentation and reduced HOXA7 methylation.

Conclusions

Exposome factors such as environmental burden and occupational exposure are biologically embedded in lung cancer cell through gene-specific methylation and significantly impact survival. We posit that integrating exposomic and molecular data could enhance lung precision oncology approaches for high-risk veteran populations.

Background

The Exposome—the comprehensive accumulation of environmental exposures from birth to death—provides a framework for linking external risk factors to cancer biology. In U.S. veterans, the exposome includes both military-specific exposures (e.g., asbestos, Agent Orange, burn pits) and postservice socioeconomic and environmental factors. These cumulative exposures may drive tumor development and progression via epigenetic mechanisms, though their impact on lung cancer outcomes remain poorly characterized.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of 71 lung cancer subjects (NSCLC and SCLC) from the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center (IRB# 1586320). We assessed the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), Environmental Burden Index (EBI), and occupational exposure in relation to DNA methylation of CDO1, TAC1, SOX17, and HOXA7. Geospatial data were mapped to US census tracts, and standard statistical analysis were conducted.

Results

NSCLC patients exhibited significantly higher methylation levels across all genes. High EBI exposure was associated with lower SOX17 methylation (p = 0.064) and worse overall survival (p = 0.046). In NSCLC patients, occupational exposure predicted a 7.7-fold increased hazard of death (p = 0.027). SOX17 and TAC1 methylation were independently associated with reduced survival (p = 0.037 and 0.0058, respectively). While ADI did not independently predict survival, it correlated with late-stage presentation and reduced HOXA7 methylation.

Conclusions

Exposome factors such as environmental burden and occupational exposure are biologically embedded in lung cancer cell through gene-specific methylation and significantly impact survival. We posit that integrating exposomic and molecular data could enhance lung precision oncology approaches for high-risk veteran populations.

Access to Germline Genetic Testing through Clinical Pathways in Veterans With Prostate Cancer

Background

Germline genetic testing (GGT) is essential in prostate cancer care, informing clinical decisions. The Veterans Affairs National Oncology Program (VA NOP) recommends GGT for patients with specific risk factors in non-metastatic prostate cancer and all patients with metastatic disease. Understanding GGT access helps evaluate care quality and guide improvements. Since 2021, VA NOP has implemented pathway health factor (HF) templates to standardize cancer care documentation, including GGT status, enabling data extraction from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) rather than requiring manual review of clinical notes. This work aims to evaluate Veterans’ access to GGT in prostate cancer care by leveraging pathway HF templates, and to assess the feasibility of using structured electronic health record (EHR) data to monitor adherence to GGT recommendations.

Methods

Process delivery diagrams (PDDs) were used to map data flow from prostate cancer clinical pathways to the VA CDW. We identified and categorized HFs related to prostate cancer GGT through the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize access, ordering, and consent rates.

Results

We identified 5,744 Veterans with at least one prostate cancer GGT-relevant HF entered between 02/01/2021 and 12/31/2024. Of these, 5,125 (89.2%) had access to GGT, with 4,569 (89.2%) consenting to or having GGT ordered, while 556 (10.8%) declined testing. Among the 619 (10.8%) Veterans without GGT access, providers reported plans to discuss GGT in the future for 528 (85.3%) patients, while 91 (14.7%) were off pathway.

Conclusions

NOP-developed HF templates enabled extraction of GGT information from structured EHR data, eliminating manual extraction from clinical notes. We observed high GGT utilization among Veterans with pathway-entered HFs. However, low overall HF utilization may introduce selection bias. Future work includes developing a Natural Language Processing pipeline using large language models to automatically extract GGT information from clinical notes, with HF data serving as ground truth.

Background

Germline genetic testing (GGT) is essential in prostate cancer care, informing clinical decisions. The Veterans Affairs National Oncology Program (VA NOP) recommends GGT for patients with specific risk factors in non-metastatic prostate cancer and all patients with metastatic disease. Understanding GGT access helps evaluate care quality and guide improvements. Since 2021, VA NOP has implemented pathway health factor (HF) templates to standardize cancer care documentation, including GGT status, enabling data extraction from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) rather than requiring manual review of clinical notes. This work aims to evaluate Veterans’ access to GGT in prostate cancer care by leveraging pathway HF templates, and to assess the feasibility of using structured electronic health record (EHR) data to monitor adherence to GGT recommendations.

Methods

Process delivery diagrams (PDDs) were used to map data flow from prostate cancer clinical pathways to the VA CDW. We identified and categorized HFs related to prostate cancer GGT through the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize access, ordering, and consent rates.

Results

We identified 5,744 Veterans with at least one prostate cancer GGT-relevant HF entered between 02/01/2021 and 12/31/2024. Of these, 5,125 (89.2%) had access to GGT, with 4,569 (89.2%) consenting to or having GGT ordered, while 556 (10.8%) declined testing. Among the 619 (10.8%) Veterans without GGT access, providers reported plans to discuss GGT in the future for 528 (85.3%) patients, while 91 (14.7%) were off pathway.

Conclusions

NOP-developed HF templates enabled extraction of GGT information from structured EHR data, eliminating manual extraction from clinical notes. We observed high GGT utilization among Veterans with pathway-entered HFs. However, low overall HF utilization may introduce selection bias. Future work includes developing a Natural Language Processing pipeline using large language models to automatically extract GGT information from clinical notes, with HF data serving as ground truth.

Background

Germline genetic testing (GGT) is essential in prostate cancer care, informing clinical decisions. The Veterans Affairs National Oncology Program (VA NOP) recommends GGT for patients with specific risk factors in non-metastatic prostate cancer and all patients with metastatic disease. Understanding GGT access helps evaluate care quality and guide improvements. Since 2021, VA NOP has implemented pathway health factor (HF) templates to standardize cancer care documentation, including GGT status, enabling data extraction from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) rather than requiring manual review of clinical notes. This work aims to evaluate Veterans’ access to GGT in prostate cancer care by leveraging pathway HF templates, and to assess the feasibility of using structured electronic health record (EHR) data to monitor adherence to GGT recommendations.

Methods

Process delivery diagrams (PDDs) were used to map data flow from prostate cancer clinical pathways to the VA CDW. We identified and categorized HFs related to prostate cancer GGT through the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize access, ordering, and consent rates.

Results

We identified 5,744 Veterans with at least one prostate cancer GGT-relevant HF entered between 02/01/2021 and 12/31/2024. Of these, 5,125 (89.2%) had access to GGT, with 4,569 (89.2%) consenting to or having GGT ordered, while 556 (10.8%) declined testing. Among the 619 (10.8%) Veterans without GGT access, providers reported plans to discuss GGT in the future for 528 (85.3%) patients, while 91 (14.7%) were off pathway.

Conclusions

NOP-developed HF templates enabled extraction of GGT information from structured EHR data, eliminating manual extraction from clinical notes. We observed high GGT utilization among Veterans with pathway-entered HFs. However, low overall HF utilization may introduce selection bias. Future work includes developing a Natural Language Processing pipeline using large language models to automatically extract GGT information from clinical notes, with HF data serving as ground truth.

VA Ann Arbor Immunotherapy Stewardship Program

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

From Screening to Support: Enhancing Cancer Care Through eScreener Technology

Background

Addressing cancer-related distress is a critical component of comprehensive oncology care. In alignment with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which advocate for routine distress screening as a standard of care, our institution aimed to enhance a previously underutilized paper-based screening process by implementing a more efficient and accessible solution.

Objective

To improve screening rates and streamline the identification of psychosocial needs of Veterans who have cancer.

Population

This initiative was conducted in an outpatient Hematology/Oncology clinic at a Midwest Federal Healthcare Center.

Methods

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement model was used to guide the implementation of the electronic screener. The eScreener was integrated into routine clinical workflow and staff received training to facilitate implementation. Veterans self-identified their needs through the screener, which included a range of practical, family/social, physical, religious or emotional concerns. Clinical staff then review the responses, assessed the identified needs, and entered appropriate referrals into the electronic health record. A dedicated certified nursing assistant (CNA) was incorporated into the workflow to support implementation efforts. As part of their role, the CNA was tasked with ensuring that all Veterans completed the distress screener either electronically or on paper during their visit

Results

Between January 2025 and March 2025, a total of 180 distress screens were completed using the newly implement method. During the same period in the previous year, only 60 screens were completed, representing a 200% increase. The new process enabled timely referrals based on identified needs, resulting in 39 referrals to physicians, 32 to psychologists, 10 to social work, 7 to dieticians, 6 to nurses, and 1 to pastoral care. These outcomes reflect a significant improvement in both accessibility and patient engagement.

Conclusions

The implementation of an electronic cancer distress screener, along with a dedicated staff member resulted in a substantial increase in screening completion rates and multidisciplinary referrals. These preliminary finds suggest that digital tools can significantly enhance psychosocial assessment, improve coordination, and support the delivery of timely, patient-centered oncology care.

Background

Addressing cancer-related distress is a critical component of comprehensive oncology care. In alignment with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which advocate for routine distress screening as a standard of care, our institution aimed to enhance a previously underutilized paper-based screening process by implementing a more efficient and accessible solution.

Objective

To improve screening rates and streamline the identification of psychosocial needs of Veterans who have cancer.

Population

This initiative was conducted in an outpatient Hematology/Oncology clinic at a Midwest Federal Healthcare Center.

Methods

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement model was used to guide the implementation of the electronic screener. The eScreener was integrated into routine clinical workflow and staff received training to facilitate implementation. Veterans self-identified their needs through the screener, which included a range of practical, family/social, physical, religious or emotional concerns. Clinical staff then review the responses, assessed the identified needs, and entered appropriate referrals into the electronic health record. A dedicated certified nursing assistant (CNA) was incorporated into the workflow to support implementation efforts. As part of their role, the CNA was tasked with ensuring that all Veterans completed the distress screener either electronically or on paper during their visit

Results

Between January 2025 and March 2025, a total of 180 distress screens were completed using the newly implement method. During the same period in the previous year, only 60 screens were completed, representing a 200% increase. The new process enabled timely referrals based on identified needs, resulting in 39 referrals to physicians, 32 to psychologists, 10 to social work, 7 to dieticians, 6 to nurses, and 1 to pastoral care. These outcomes reflect a significant improvement in both accessibility and patient engagement.

Conclusions

The implementation of an electronic cancer distress screener, along with a dedicated staff member resulted in a substantial increase in screening completion rates and multidisciplinary referrals. These preliminary finds suggest that digital tools can significantly enhance psychosocial assessment, improve coordination, and support the delivery of timely, patient-centered oncology care.

Background

Addressing cancer-related distress is a critical component of comprehensive oncology care. In alignment with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which advocate for routine distress screening as a standard of care, our institution aimed to enhance a previously underutilized paper-based screening process by implementing a more efficient and accessible solution.

Objective

To improve screening rates and streamline the identification of psychosocial needs of Veterans who have cancer.

Population

This initiative was conducted in an outpatient Hematology/Oncology clinic at a Midwest Federal Healthcare Center.

Methods

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement model was used to guide the implementation of the electronic screener. The eScreener was integrated into routine clinical workflow and staff received training to facilitate implementation. Veterans self-identified their needs through the screener, which included a range of practical, family/social, physical, religious or emotional concerns. Clinical staff then review the responses, assessed the identified needs, and entered appropriate referrals into the electronic health record. A dedicated certified nursing assistant (CNA) was incorporated into the workflow to support implementation efforts. As part of their role, the CNA was tasked with ensuring that all Veterans completed the distress screener either electronically or on paper during their visit

Results

Between January 2025 and March 2025, a total of 180 distress screens were completed using the newly implement method. During the same period in the previous year, only 60 screens were completed, representing a 200% increase. The new process enabled timely referrals based on identified needs, resulting in 39 referrals to physicians, 32 to psychologists, 10 to social work, 7 to dieticians, 6 to nurses, and 1 to pastoral care. These outcomes reflect a significant improvement in both accessibility and patient engagement.

Conclusions

The implementation of an electronic cancer distress screener, along with a dedicated staff member resulted in a substantial increase in screening completion rates and multidisciplinary referrals. These preliminary finds suggest that digital tools can significantly enhance psychosocial assessment, improve coordination, and support the delivery of timely, patient-centered oncology care.

Case Presentation: First Ever VA "Bloodless" Autologous Stem Cell Transplant Was a Success

Background

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is an important part of the treatment paradigm for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients. Blood product transfusion support in the form of platelets and packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is part of the standard of practice as supportive measures during the severely pancytopenic period. Some MM patients, such as those of Jehovah’s Witness (JW) faith, may have religious beliefs or preferences that preclude acceptance of such blood products. Some transplant centers have developed protocols to allow safe “bloodless” ASCT that allows these patients to receive this important treatment while adhering to their beliefs or preferences.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old veteran of JW faith with newly diagnosed IgG Kappa Multiple Myeloma was referred to the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS) Stem Cell Transplant program for consideration of “bloodless” ASCT. With the assistance and expertise of the academic affiliate, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s established bloodless ASCT protocol, this same protocol was established at TVHS to optimize the patient’s care pretransplant (use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents, intravenous iron, B12 supplementation) as well as post-transplant (use of antifibrinolytics, close inpatient monitoring). Both Ethics and Legal consultation was obtained, and guidance was provided to create a life sustaining treatment (LST) note in the veteran’s electronic health record that captured the veteran’s blood product preference. Once all protocols and guidance were in place, the TVHS SCT/CT program proceeded to treat the veteran with a myeloablative melphalan ASCT. The patient tolerated the procedure exceptionally well with minimal complications. He achieved full engraftment on day +14 after ASCT as expected and was discharged from the inpatient setting. He was monitored in the outpatient setting until day +30 without further complications.

Conclusions

The TVHS SCT/CT performed the first ever bloodless autologous stem cell transplant within the VA. This pioneering effort to establish such protocols to provide care to all veterans whatever their personal or religious preferences is a testament to commitment of VA to provide care for all veterans and the willingness to innovate to do so.

Background

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is an important part of the treatment paradigm for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients. Blood product transfusion support in the form of platelets and packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is part of the standard of practice as supportive measures during the severely pancytopenic period. Some MM patients, such as those of Jehovah’s Witness (JW) faith, may have religious beliefs or preferences that preclude acceptance of such blood products. Some transplant centers have developed protocols to allow safe “bloodless” ASCT that allows these patients to receive this important treatment while adhering to their beliefs or preferences.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old veteran of JW faith with newly diagnosed IgG Kappa Multiple Myeloma was referred to the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS) Stem Cell Transplant program for consideration of “bloodless” ASCT. With the assistance and expertise of the academic affiliate, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s established bloodless ASCT protocol, this same protocol was established at TVHS to optimize the patient’s care pretransplant (use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents, intravenous iron, B12 supplementation) as well as post-transplant (use of antifibrinolytics, close inpatient monitoring). Both Ethics and Legal consultation was obtained, and guidance was provided to create a life sustaining treatment (LST) note in the veteran’s electronic health record that captured the veteran’s blood product preference. Once all protocols and guidance were in place, the TVHS SCT/CT program proceeded to treat the veteran with a myeloablative melphalan ASCT. The patient tolerated the procedure exceptionally well with minimal complications. He achieved full engraftment on day +14 after ASCT as expected and was discharged from the inpatient setting. He was monitored in the outpatient setting until day +30 without further complications.

Conclusions

The TVHS SCT/CT performed the first ever bloodless autologous stem cell transplant within the VA. This pioneering effort to establish such protocols to provide care to all veterans whatever their personal or religious preferences is a testament to commitment of VA to provide care for all veterans and the willingness to innovate to do so.

Background

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is an important part of the treatment paradigm for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and remains the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients. Blood product transfusion support in the form of platelets and packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is part of the standard of practice as supportive measures during the severely pancytopenic period. Some MM patients, such as those of Jehovah’s Witness (JW) faith, may have religious beliefs or preferences that preclude acceptance of such blood products. Some transplant centers have developed protocols to allow safe “bloodless” ASCT that allows these patients to receive this important treatment while adhering to their beliefs or preferences.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old veteran of JW faith with newly diagnosed IgG Kappa Multiple Myeloma was referred to the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS) Stem Cell Transplant program for consideration of “bloodless” ASCT. With the assistance and expertise of the academic affiliate, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s established bloodless ASCT protocol, this same protocol was established at TVHS to optimize the patient’s care pretransplant (use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents, intravenous iron, B12 supplementation) as well as post-transplant (use of antifibrinolytics, close inpatient monitoring). Both Ethics and Legal consultation was obtained, and guidance was provided to create a life sustaining treatment (LST) note in the veteran’s electronic health record that captured the veteran’s blood product preference. Once all protocols and guidance were in place, the TVHS SCT/CT program proceeded to treat the veteran with a myeloablative melphalan ASCT. The patient tolerated the procedure exceptionally well with minimal complications. He achieved full engraftment on day +14 after ASCT as expected and was discharged from the inpatient setting. He was monitored in the outpatient setting until day +30 without further complications.

Conclusions

The TVHS SCT/CT performed the first ever bloodless autologous stem cell transplant within the VA. This pioneering effort to establish such protocols to provide care to all veterans whatever their personal or religious preferences is a testament to commitment of VA to provide care for all veterans and the willingness to innovate to do so.

Generalized Erythematous Plaques and Pustules in a Pregnant Patient

Generalized Erythematous Plaques and Pustules in a Pregnant Patient

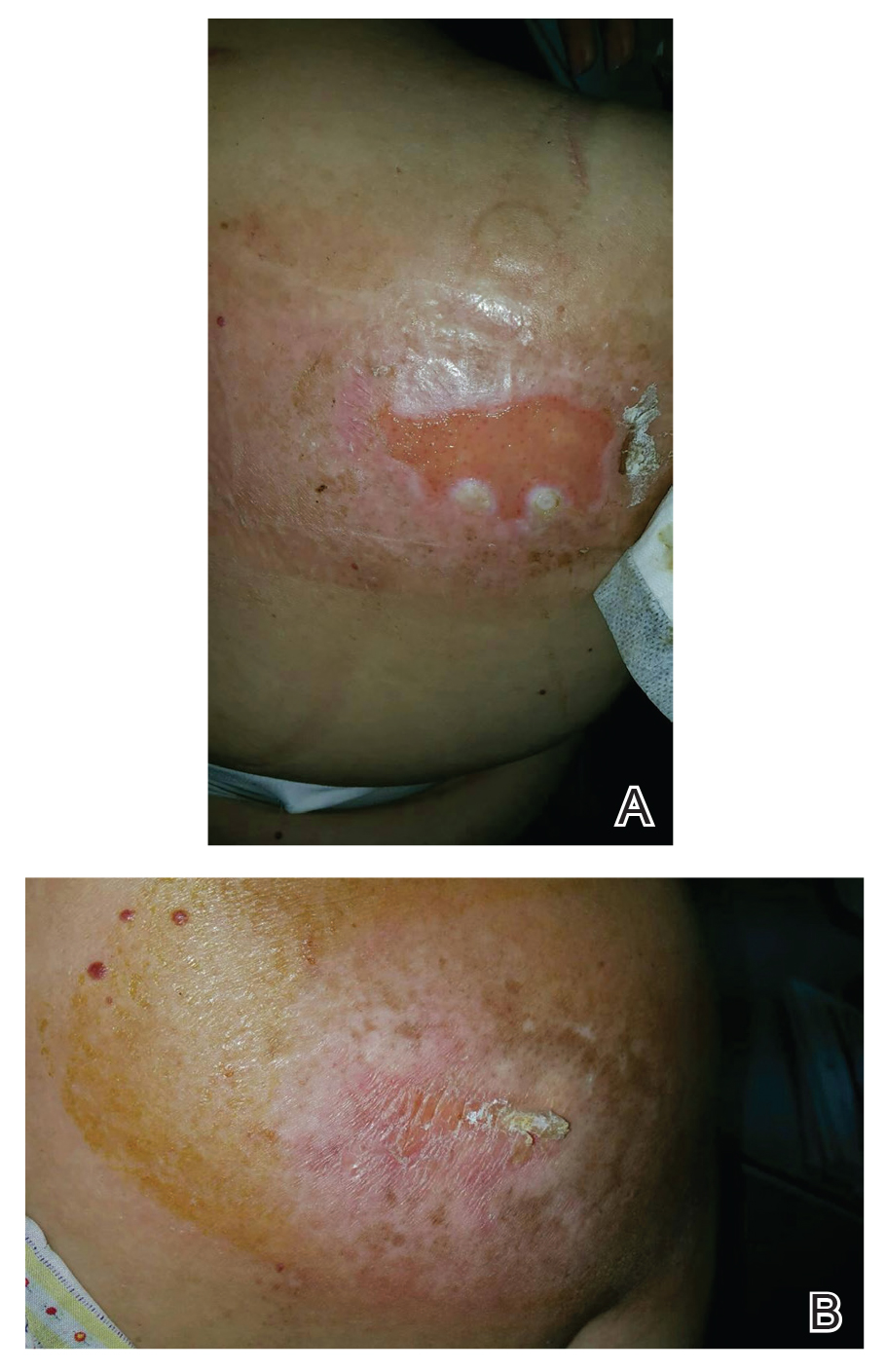

THE DIAGNOSIS: Impetigo Herpetiformis

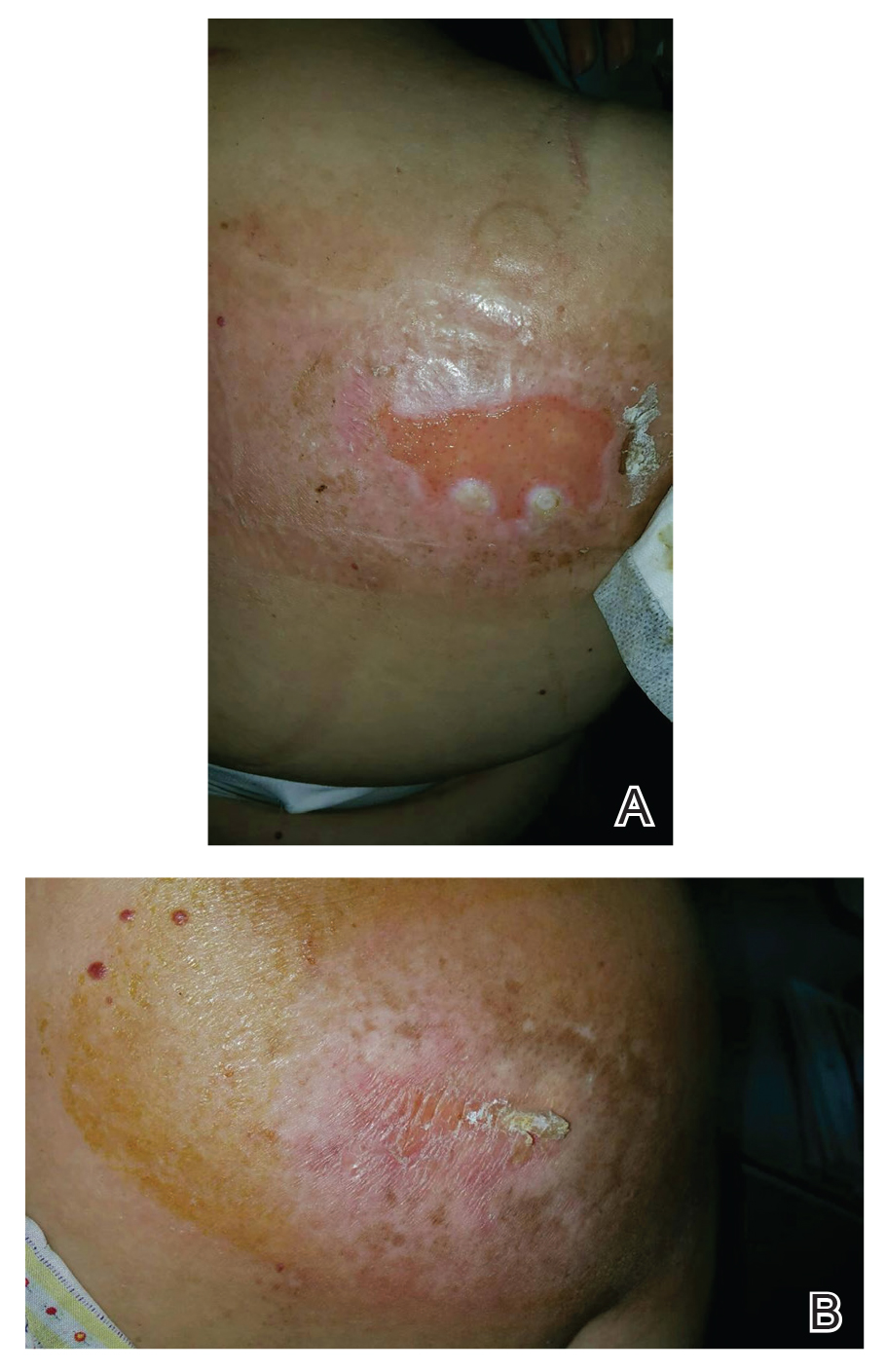

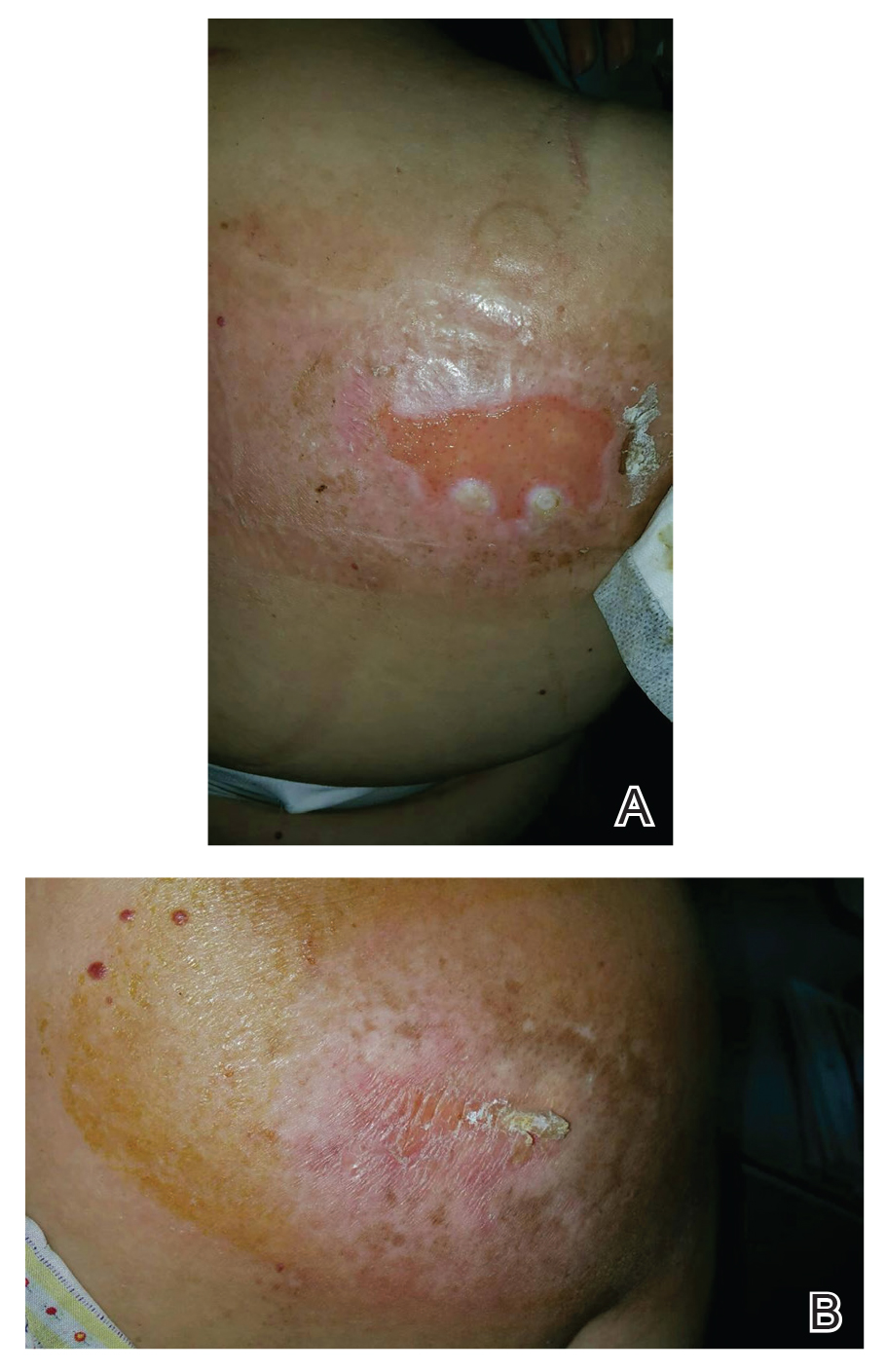

Histopathology revealed epidermal acanthosis and spongiosis with overlying parakeratosis associated with subcorneal and intracorneal neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and dermal mixed inflammation with neutrophils and eosinophils. Both direct immunofluorescence and periodic acid–Schiff studies were negative. Blood and pustule cultures were sterile and the skin flora were normal. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of impetigo herpetiformis (IH) was made. The condition improved with systemic and topical steroids, supportive care, and an intravenous infusion of infliximab 5 mg/kg. At 3 weeks’ follow-up, the patient demonstrated near-complete resolution and later delivered successfully at 40 weeks’ gestation without complications.

Impetigo herpetiformis, also known as pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, is an exceedingly rare gestational dermatosis that typically manifests in the third trimester and can be life-threatening for both the mother and fetus. The term was first used in 1872 to describe 5 pregnant women with extensive acute pustular eruptions, all in unstable condition; 4 (80%)of the cases resulted in maternal death, and all resulted in fetal death.1 Impetigo herpetiformis is characterized by pruritic and painful erythematous patches studded at the periphery with subcorneal pustules. Eruptions usually occur in the flexural areas and spread centrifugally, with extension of the lesions peripherally as the center erodes and crusts. Sparing of the face, palms, and soles is expected, and mucosal involvement is rare. Generalized involvement and exfoliation may occur in extreme cases.2 While IH typically manifests during the third trimester, it may occur any time throughout pregnancy or immediately postpartum.3 A few cases have been reported in the puerperium.2 Common symptoms include fever, chills, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and arthralgias. Less common complications include hypoalbuminemia and severe hypocalcemia leading to tetany, seizures, and delirium.2,3 While maternal mortality is uncommon, fetal mortality often is a more pressing risk and is attributed to placental insufficiency.3,4 For this reason, early delivery commonly is considered in severe cases.

Whether IH is a separate entity or a variant of pustular psoriasis remains heavily debated. Although the histopathology of IH is identical to pustular psoriasis, the lack of a personal and family history of psoriasis, symptom resolution with delivery, and possible recurrence during successive pregnancies help differentiate IH from generalized pustular psoriasis.2,5 Earlier onset, diffuse involvement, faster progression, and recurrence in subsequent pregnancies all have been linked to a worse prognosis.4

The differential diagnosis for IH includes acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, pemphigoid gestationis, dermatitis herpetiformis, and subcorneal pustular dermatosis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon severe cutaneous drug reaction characterized by the sudden onset of numerous sterile pustules on erythematous skin within 48 hours of exposure. The most common offending medications include pristinamycin and beta-lactam antibiotics. A high fever, neutrophilic leukocytosis, and hypocalcemia often accompany acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.6 Prompt diagnosis and withdrawal of the offending drug as well as supportive care and symptomatic treatment are crucial for disease management, as systemic symptoms and even organ involvement may occur.6

Pemphigoid gestationis, also known as gestational pemphigoid or herpes gestationis, is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder that primarily affects pregnant women. It typically manifests in the second or third trimester or shortly after delivery. Clinically, it manifests as an intensely pruritic polymorphic eruption of urticarial papules and plaques accompanied by vesicles and bullae and often is distributed on the abdomen and extends to other body regions. Although the exact etiology is unknown, pemphigoid gestationis is caused by autoantibodies targeting the BP180 and BP230 hemidesmosomal proteins.7 Treatment usually involves systemic corticosteroids and may require additional immunosuppressive therapy. In most cases, patients see resolution within 6 months of delivery.7

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic autoimmune blistering skin disorder characterized by intensely pruritic, grouped vesicles and papules, often distributed symmetrically on extensor surfaces such as the elbows, knees, buttocks, and back. It is closely associated with celiac disease and is triggered by gluten ingestion in genetically predisposed individuals with human leukocyte antigen DQ2 and DQ8 haplotypes. Dermatitis herpetiformis is caused by deposition of IgA antibodies that target tissue transglutaminase 3 at the dermal papillae, leading to inflammation and blister formation. 8 Treatment typically involves a gluten-free diet and medications such as dapsone to alleviate symptoms and prevent recurrence.

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis, also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, is a rare chronic relapsing pustular dermatosis characterized by sterile superficial pustules arranged in annular or circinate patterns on erythematous plaques. It predominantly affects middleaged women and often is associated with underlying conditions such as IgA gammopathy or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but immune dysregulation is thought to play a role. Some authors still question whether subcorneal pustular dermatosis is a distinct entity from pustular psoriasis.4,5,12 Dapsone is the preferred first-line treatment, with adjunct therapies including topical or systemic corticosteroids, other immunosuppressive agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and UV light therapy.9

Definitive management of IH is achieved through early delivery; however, systemic corticosteroids often are used in varying doses to control the disease and to extend the pregnancy period closer to term or until delivery is considered viable. Additional therapies that can be considered include infliximab, cyclosporine, and topical corticosteroids, in conjunction with fluid and electrolyte maintenance.2,4,10 If symptoms persist despite supportive care and pharmacologic intervention, induction of labor or termination of pregnancy may be indicated. In nonbreastfeeding postpartum mothers with persistent disease, therapies commonly used in generalized pustular psoriasis may be given.11

- Hebra F. Ueber einzelne wahrend Schwangerschaft, des wacherbette unde bei uterinal. Krankheiten der Frauen zu beobachtende Hautkrankheiten. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1872;48:1197-1202.

- Fouda UM, Fouda RM, Ammar HM, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis during the puerperium triggered by secondary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9338. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9338

- Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:1-22. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114595

- Liu J, Ali K, Lou H, et al. First-trimester impetigo herpetiformis leads to stillbirth: a case report. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1271-1279. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00735-9

- Lotem M, Katzenelson V, Rotem A, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis: a variant of pustular psoriasis or a separate entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:338-41. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70042-6

- Stadler PC, Oschmann A, Kerl-French K, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, pathogenesis, and management. Dermatology. 2023;239:328-333. doi:10.1159/000529218

- Abdelhafez MMA, Ahmed KAM, Daud MNBM, et al. Pemphigoid gestationis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a literature review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51:102370. doi:10.1016 /j.jogoh.2022.102370

- Reunala T, Hervonen K, Salmi T. Dermatitis herpetiformis: an update on diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:329-338. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00584-2

- Watts PJ, Khachemoune A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a review of 30 years of progress. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:653-671. doi:10.1007 /s40257-016-0202-8

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.032

- Bukhari IA. Impetigo herpetiformis in a primigravida: successful treatment with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:449-451.

- Chang SE, Kim HH, Choi JH, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis followed by generalized pustular psoriasis: more evidence of same disease entity. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(9):754-755.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Impetigo Herpetiformis

Histopathology revealed epidermal acanthosis and spongiosis with overlying parakeratosis associated with subcorneal and intracorneal neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and dermal mixed inflammation with neutrophils and eosinophils. Both direct immunofluorescence and periodic acid–Schiff studies were negative. Blood and pustule cultures were sterile and the skin flora were normal. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of impetigo herpetiformis (IH) was made. The condition improved with systemic and topical steroids, supportive care, and an intravenous infusion of infliximab 5 mg/kg. At 3 weeks’ follow-up, the patient demonstrated near-complete resolution and later delivered successfully at 40 weeks’ gestation without complications.

Impetigo herpetiformis, also known as pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, is an exceedingly rare gestational dermatosis that typically manifests in the third trimester and can be life-threatening for both the mother and fetus. The term was first used in 1872 to describe 5 pregnant women with extensive acute pustular eruptions, all in unstable condition; 4 (80%)of the cases resulted in maternal death, and all resulted in fetal death.1 Impetigo herpetiformis is characterized by pruritic and painful erythematous patches studded at the periphery with subcorneal pustules. Eruptions usually occur in the flexural areas and spread centrifugally, with extension of the lesions peripherally as the center erodes and crusts. Sparing of the face, palms, and soles is expected, and mucosal involvement is rare. Generalized involvement and exfoliation may occur in extreme cases.2 While IH typically manifests during the third trimester, it may occur any time throughout pregnancy or immediately postpartum.3 A few cases have been reported in the puerperium.2 Common symptoms include fever, chills, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and arthralgias. Less common complications include hypoalbuminemia and severe hypocalcemia leading to tetany, seizures, and delirium.2,3 While maternal mortality is uncommon, fetal mortality often is a more pressing risk and is attributed to placental insufficiency.3,4 For this reason, early delivery commonly is considered in severe cases.

Whether IH is a separate entity or a variant of pustular psoriasis remains heavily debated. Although the histopathology of IH is identical to pustular psoriasis, the lack of a personal and family history of psoriasis, symptom resolution with delivery, and possible recurrence during successive pregnancies help differentiate IH from generalized pustular psoriasis.2,5 Earlier onset, diffuse involvement, faster progression, and recurrence in subsequent pregnancies all have been linked to a worse prognosis.4

The differential diagnosis for IH includes acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, pemphigoid gestationis, dermatitis herpetiformis, and subcorneal pustular dermatosis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon severe cutaneous drug reaction characterized by the sudden onset of numerous sterile pustules on erythematous skin within 48 hours of exposure. The most common offending medications include pristinamycin and beta-lactam antibiotics. A high fever, neutrophilic leukocytosis, and hypocalcemia often accompany acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.6 Prompt diagnosis and withdrawal of the offending drug as well as supportive care and symptomatic treatment are crucial for disease management, as systemic symptoms and even organ involvement may occur.6

Pemphigoid gestationis, also known as gestational pemphigoid or herpes gestationis, is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder that primarily affects pregnant women. It typically manifests in the second or third trimester or shortly after delivery. Clinically, it manifests as an intensely pruritic polymorphic eruption of urticarial papules and plaques accompanied by vesicles and bullae and often is distributed on the abdomen and extends to other body regions. Although the exact etiology is unknown, pemphigoid gestationis is caused by autoantibodies targeting the BP180 and BP230 hemidesmosomal proteins.7 Treatment usually involves systemic corticosteroids and may require additional immunosuppressive therapy. In most cases, patients see resolution within 6 months of delivery.7

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic autoimmune blistering skin disorder characterized by intensely pruritic, grouped vesicles and papules, often distributed symmetrically on extensor surfaces such as the elbows, knees, buttocks, and back. It is closely associated with celiac disease and is triggered by gluten ingestion in genetically predisposed individuals with human leukocyte antigen DQ2 and DQ8 haplotypes. Dermatitis herpetiformis is caused by deposition of IgA antibodies that target tissue transglutaminase 3 at the dermal papillae, leading to inflammation and blister formation. 8 Treatment typically involves a gluten-free diet and medications such as dapsone to alleviate symptoms and prevent recurrence.

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis, also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, is a rare chronic relapsing pustular dermatosis characterized by sterile superficial pustules arranged in annular or circinate patterns on erythematous plaques. It predominantly affects middleaged women and often is associated with underlying conditions such as IgA gammopathy or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but immune dysregulation is thought to play a role. Some authors still question whether subcorneal pustular dermatosis is a distinct entity from pustular psoriasis.4,5,12 Dapsone is the preferred first-line treatment, with adjunct therapies including topical or systemic corticosteroids, other immunosuppressive agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and UV light therapy.9

Definitive management of IH is achieved through early delivery; however, systemic corticosteroids often are used in varying doses to control the disease and to extend the pregnancy period closer to term or until delivery is considered viable. Additional therapies that can be considered include infliximab, cyclosporine, and topical corticosteroids, in conjunction with fluid and electrolyte maintenance.2,4,10 If symptoms persist despite supportive care and pharmacologic intervention, induction of labor or termination of pregnancy may be indicated. In nonbreastfeeding postpartum mothers with persistent disease, therapies commonly used in generalized pustular psoriasis may be given.11

THE DIAGNOSIS: Impetigo Herpetiformis

Histopathology revealed epidermal acanthosis and spongiosis with overlying parakeratosis associated with subcorneal and intracorneal neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and dermal mixed inflammation with neutrophils and eosinophils. Both direct immunofluorescence and periodic acid–Schiff studies were negative. Blood and pustule cultures were sterile and the skin flora were normal. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of impetigo herpetiformis (IH) was made. The condition improved with systemic and topical steroids, supportive care, and an intravenous infusion of infliximab 5 mg/kg. At 3 weeks’ follow-up, the patient demonstrated near-complete resolution and later delivered successfully at 40 weeks’ gestation without complications.

Impetigo herpetiformis, also known as pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, is an exceedingly rare gestational dermatosis that typically manifests in the third trimester and can be life-threatening for both the mother and fetus. The term was first used in 1872 to describe 5 pregnant women with extensive acute pustular eruptions, all in unstable condition; 4 (80%)of the cases resulted in maternal death, and all resulted in fetal death.1 Impetigo herpetiformis is characterized by pruritic and painful erythematous patches studded at the periphery with subcorneal pustules. Eruptions usually occur in the flexural areas and spread centrifugally, with extension of the lesions peripherally as the center erodes and crusts. Sparing of the face, palms, and soles is expected, and mucosal involvement is rare. Generalized involvement and exfoliation may occur in extreme cases.2 While IH typically manifests during the third trimester, it may occur any time throughout pregnancy or immediately postpartum.3 A few cases have been reported in the puerperium.2 Common symptoms include fever, chills, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and arthralgias. Less common complications include hypoalbuminemia and severe hypocalcemia leading to tetany, seizures, and delirium.2,3 While maternal mortality is uncommon, fetal mortality often is a more pressing risk and is attributed to placental insufficiency.3,4 For this reason, early delivery commonly is considered in severe cases.

Whether IH is a separate entity or a variant of pustular psoriasis remains heavily debated. Although the histopathology of IH is identical to pustular psoriasis, the lack of a personal and family history of psoriasis, symptom resolution with delivery, and possible recurrence during successive pregnancies help differentiate IH from generalized pustular psoriasis.2,5 Earlier onset, diffuse involvement, faster progression, and recurrence in subsequent pregnancies all have been linked to a worse prognosis.4

The differential diagnosis for IH includes acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, pemphigoid gestationis, dermatitis herpetiformis, and subcorneal pustular dermatosis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon severe cutaneous drug reaction characterized by the sudden onset of numerous sterile pustules on erythematous skin within 48 hours of exposure. The most common offending medications include pristinamycin and beta-lactam antibiotics. A high fever, neutrophilic leukocytosis, and hypocalcemia often accompany acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.6 Prompt diagnosis and withdrawal of the offending drug as well as supportive care and symptomatic treatment are crucial for disease management, as systemic symptoms and even organ involvement may occur.6

Pemphigoid gestationis, also known as gestational pemphigoid or herpes gestationis, is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder that primarily affects pregnant women. It typically manifests in the second or third trimester or shortly after delivery. Clinically, it manifests as an intensely pruritic polymorphic eruption of urticarial papules and plaques accompanied by vesicles and bullae and often is distributed on the abdomen and extends to other body regions. Although the exact etiology is unknown, pemphigoid gestationis is caused by autoantibodies targeting the BP180 and BP230 hemidesmosomal proteins.7 Treatment usually involves systemic corticosteroids and may require additional immunosuppressive therapy. In most cases, patients see resolution within 6 months of delivery.7

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic autoimmune blistering skin disorder characterized by intensely pruritic, grouped vesicles and papules, often distributed symmetrically on extensor surfaces such as the elbows, knees, buttocks, and back. It is closely associated with celiac disease and is triggered by gluten ingestion in genetically predisposed individuals with human leukocyte antigen DQ2 and DQ8 haplotypes. Dermatitis herpetiformis is caused by deposition of IgA antibodies that target tissue transglutaminase 3 at the dermal papillae, leading to inflammation and blister formation. 8 Treatment typically involves a gluten-free diet and medications such as dapsone to alleviate symptoms and prevent recurrence.

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis, also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, is a rare chronic relapsing pustular dermatosis characterized by sterile superficial pustules arranged in annular or circinate patterns on erythematous plaques. It predominantly affects middleaged women and often is associated with underlying conditions such as IgA gammopathy or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but immune dysregulation is thought to play a role. Some authors still question whether subcorneal pustular dermatosis is a distinct entity from pustular psoriasis.4,5,12 Dapsone is the preferred first-line treatment, with adjunct therapies including topical or systemic corticosteroids, other immunosuppressive agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and UV light therapy.9

Definitive management of IH is achieved through early delivery; however, systemic corticosteroids often are used in varying doses to control the disease and to extend the pregnancy period closer to term or until delivery is considered viable. Additional therapies that can be considered include infliximab, cyclosporine, and topical corticosteroids, in conjunction with fluid and electrolyte maintenance.2,4,10 If symptoms persist despite supportive care and pharmacologic intervention, induction of labor or termination of pregnancy may be indicated. In nonbreastfeeding postpartum mothers with persistent disease, therapies commonly used in generalized pustular psoriasis may be given.11

- Hebra F. Ueber einzelne wahrend Schwangerschaft, des wacherbette unde bei uterinal. Krankheiten der Frauen zu beobachtende Hautkrankheiten. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1872;48:1197-1202.

- Fouda UM, Fouda RM, Ammar HM, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis during the puerperium triggered by secondary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9338. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9338

- Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:1-22. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114595

- Liu J, Ali K, Lou H, et al. First-trimester impetigo herpetiformis leads to stillbirth: a case report. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1271-1279. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00735-9

- Lotem M, Katzenelson V, Rotem A, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis: a variant of pustular psoriasis or a separate entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:338-41. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70042-6

- Stadler PC, Oschmann A, Kerl-French K, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, pathogenesis, and management. Dermatology. 2023;239:328-333. doi:10.1159/000529218

- Abdelhafez MMA, Ahmed KAM, Daud MNBM, et al. Pemphigoid gestationis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a literature review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51:102370. doi:10.1016 /j.jogoh.2022.102370

- Reunala T, Hervonen K, Salmi T. Dermatitis herpetiformis: an update on diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:329-338. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00584-2

- Watts PJ, Khachemoune A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a review of 30 years of progress. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:653-671. doi:10.1007 /s40257-016-0202-8

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.032

- Bukhari IA. Impetigo herpetiformis in a primigravida: successful treatment with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:449-451.

- Chang SE, Kim HH, Choi JH, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis followed by generalized pustular psoriasis: more evidence of same disease entity. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(9):754-755.

- Hebra F. Ueber einzelne wahrend Schwangerschaft, des wacherbette unde bei uterinal. Krankheiten der Frauen zu beobachtende Hautkrankheiten. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1872;48:1197-1202.

- Fouda UM, Fouda RM, Ammar HM, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis during the puerperium triggered by secondary hypoparathyroidism: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9338. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9338

- Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:1-22. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114595

- Liu J, Ali K, Lou H, et al. First-trimester impetigo herpetiformis leads to stillbirth: a case report. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1271-1279. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00735-9

- Lotem M, Katzenelson V, Rotem A, et al. Impetigo herpetiformis: a variant of pustular psoriasis or a separate entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:338-41. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70042-6

- Stadler PC, Oschmann A, Kerl-French K, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, pathogenesis, and management. Dermatology. 2023;239:328-333. doi:10.1159/000529218

- Abdelhafez MMA, Ahmed KAM, Daud MNBM, et al. Pemphigoid gestationis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a literature review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51:102370. doi:10.1016 /j.jogoh.2022.102370

- Reunala T, Hervonen K, Salmi T. Dermatitis herpetiformis: an update on diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:329-338. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00584-2

- Watts PJ, Khachemoune A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a review of 30 years of progress. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:653-671. doi:10.1007 /s40257-016-0202-8