User login

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

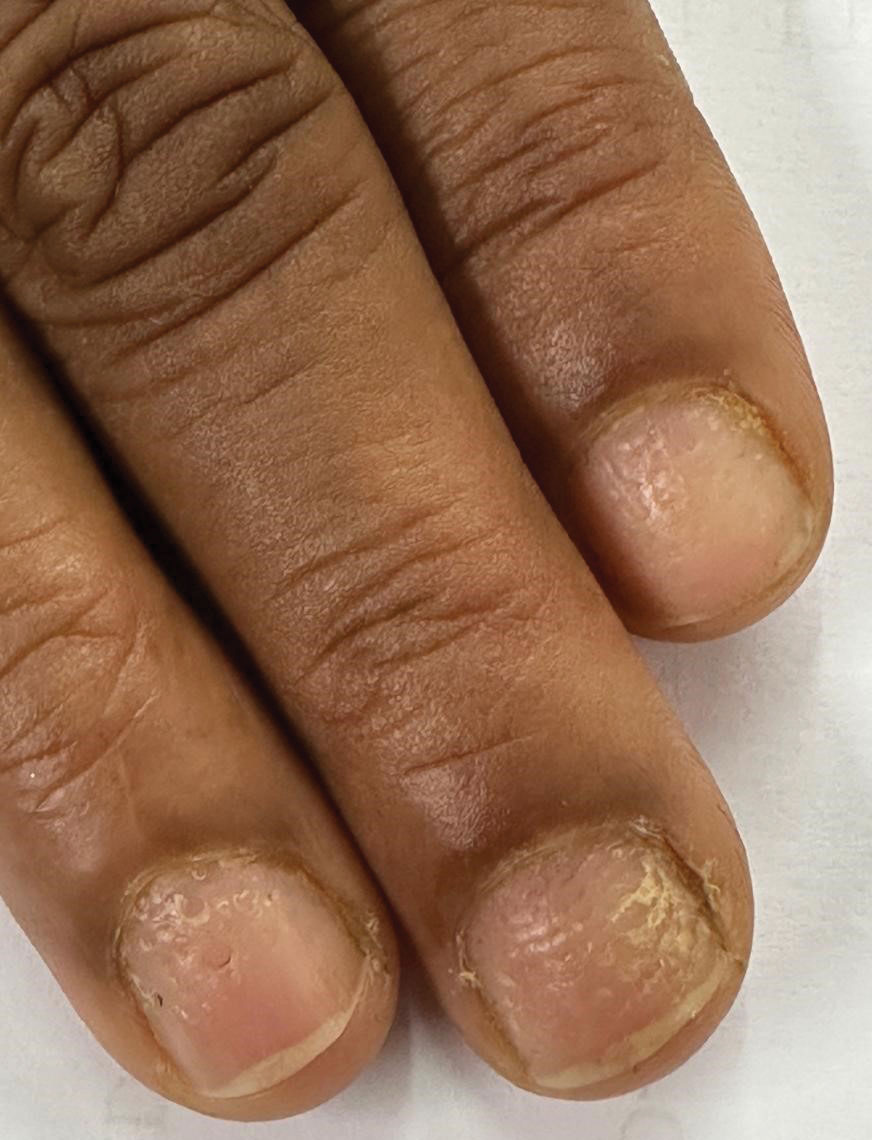

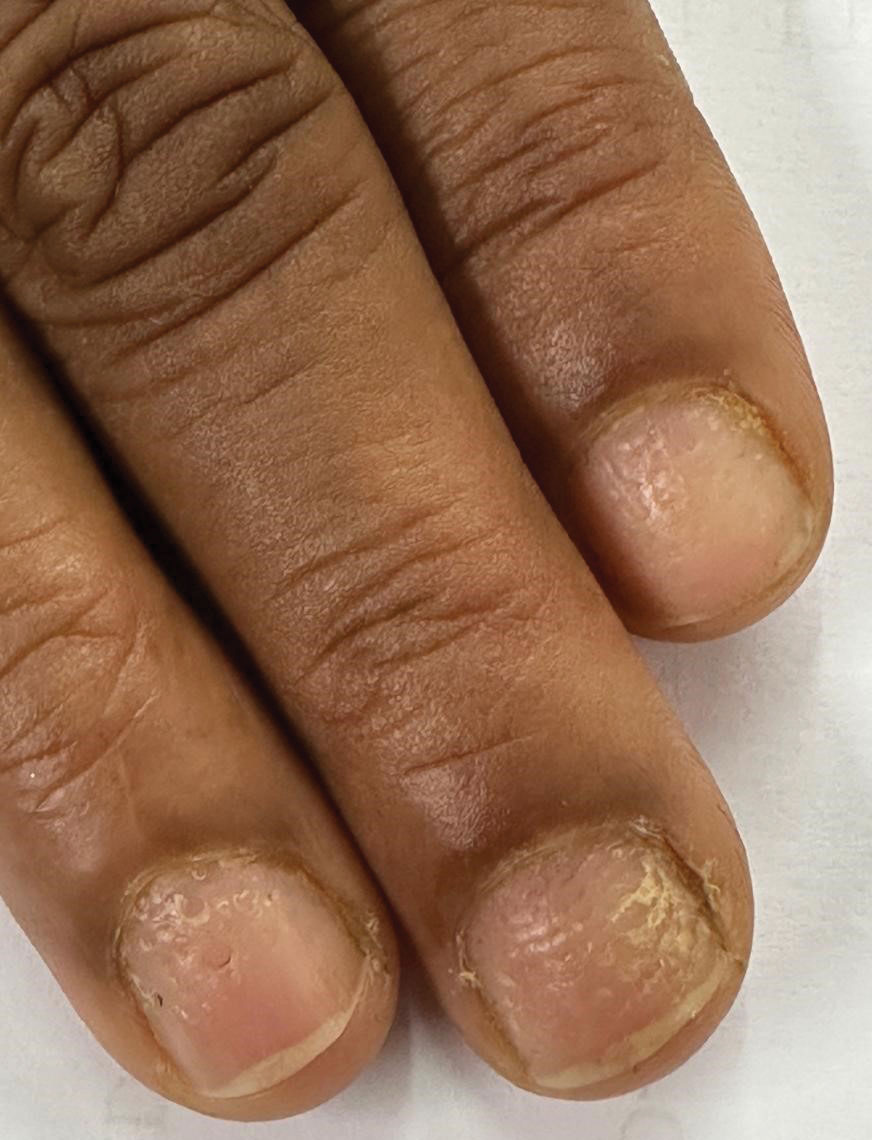

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Dermatology on Duty: Pathways to a Career in Military Medicine

Dermatology on Duty: Pathways to a Career in Military Medicine

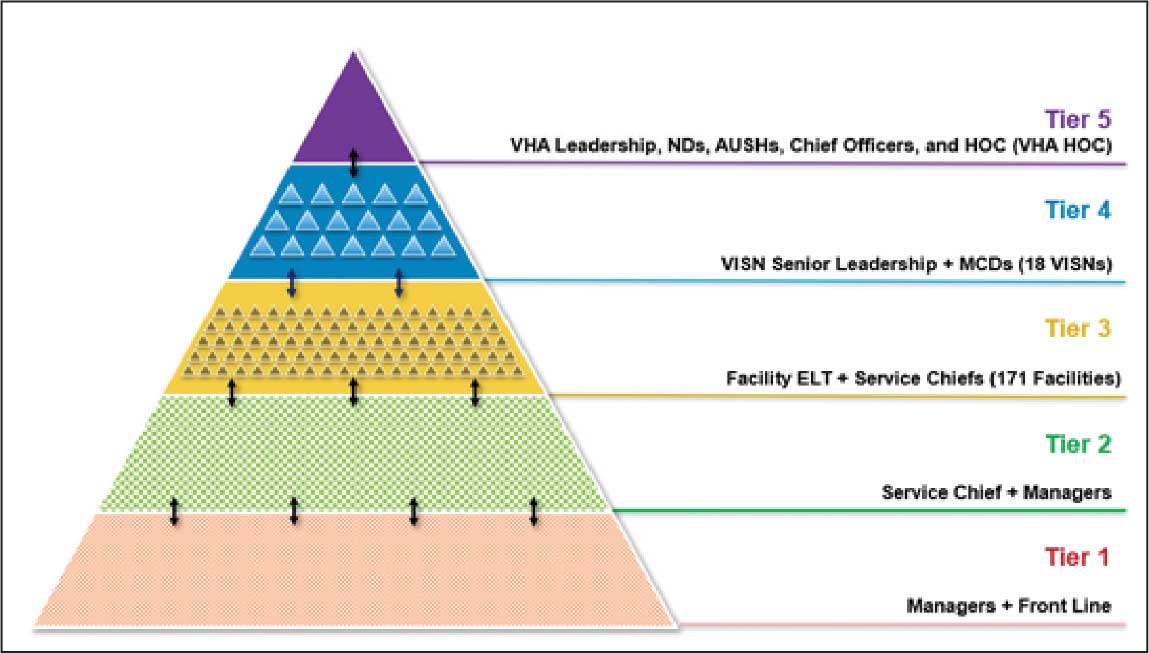

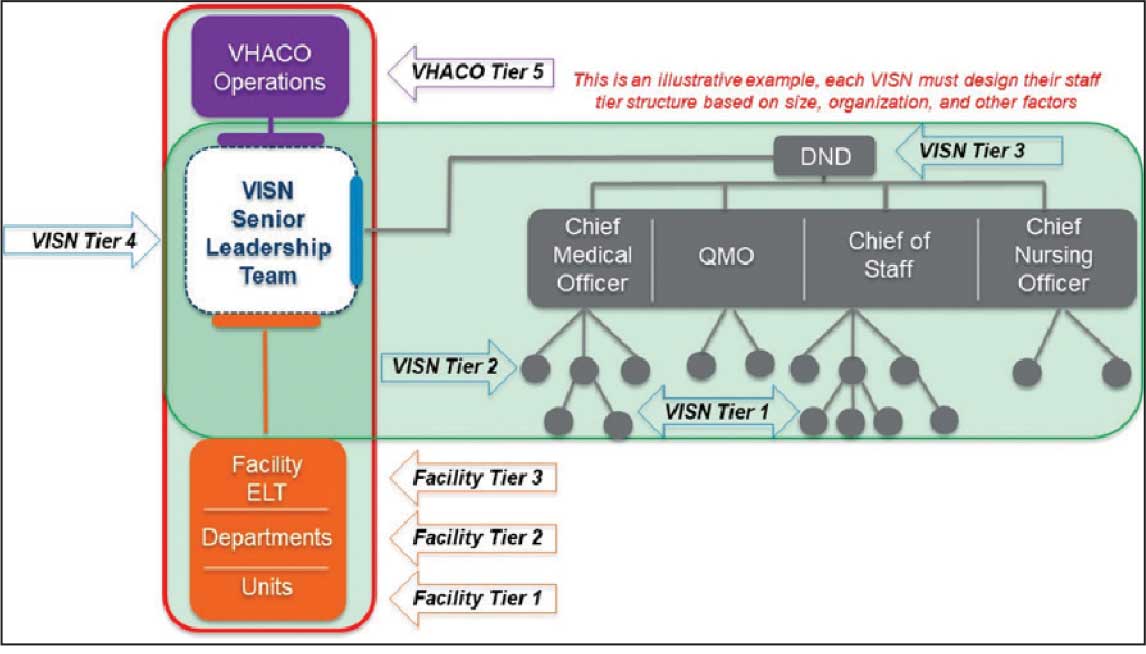

Serving those who serve has been one of the most meaningful parts of my career. A career in military medicine offers dermatologists not only a chance to practice within a unique and diverse patient population but also an opportunity to contribute to something larger than themselves. Whether working with active-duty service members and their families within the Military Health System (MHS) or caring for veterans through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the experience can be both enriching and rewarding. This article will explore the various pathways available to dermatologists to serve military communities, whether they are at the start of their careers or are looking for a change of pace within their established practice.

Care Pathways for Military and Veterans

To care for uniformed service members, their families, and retired personnel, dermatologists typically serve within the MHS—a global, integrated network of military hospitals and clinics dedicated to delivering health care to this population.1 TRICARE is the health insurance program that covers those eligible for care within the system, including active-duty and retired service members.2 In this context, it is important to clarify what the term retired actually means, as it differs from the term veteran when it comes to accessing health care options, and these terms frequently are conflated. A retired service member is an individual who completed at least 20 years of active-duty service or who has been medically retired because of a condition or injury incurred while on active duty.3 In contrast, a veteran may not have completed 20 years of service but has separated honorably after serving at least 24 continuous months.4 Veterans typically receive care through the VA system.5

Serving on Active Duty

In general, there are 2 main pathways to serve as a dermatologist within the MHS. The first is to commission in the military and serve on active duty. Most often, this pathway begins with a premedical student applying to medical school. Those considering military service typically explore scholarship programs such as the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP)(https://www.medicineandthemilitary.com/applying-and-what-to-expect/medical-school-programs/hpsp) or the Health Services Collegiate Program (HSCP), or they apply to the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU)(https://www.usuhs.edu/about). The HPSP and HSCP programs financially support medical students training at civilian medical schools, though in different ways—the HPSP covers tuition and fees, while the HSCP provides a salary during training but does not cover tuition.6 In contrast, students of USU attend the nation’s only military medical school, serving in uniform for 4 years while earning the pay and benefits of a junior officer in their respective service branch. Any premedical student considering the HPSP, HSCP or USU routes for service must meet the commissioning standards of their chosen branch—Army, Navy, or Air Force—and enter service as an officer before beginning medical school.

While direct commission prior to medical school is the most common route to active-duty service, board-certified dermatologists also can join a military branch later through what is called Direct Accession or Direct Commission; for example, the Navy offers a Residency to Direct Accession program, which commissions residents in their final year of training to join the Navy upon graduation. In some cases, commissioning at this stage includes a bonus of up to $600,000 in exchange for a 4-year active-duty commitment.7 The Army and Air Force offer similar direct commission programs, though specific incentives vary.8 Interested residents or practitioners can contact a local recruiting office within their branch of interest to learn more. Direct accession is open at many points in a dermatologist’s career—after residency, after fellowship, or even as an established civilian practitioner—and the initial commissioning rank and bonus generally reflect one’s level of experience.

Serving as a Civilian

Outside of uniformed service, dermatologists can find opportunities to provide care for active-duty service members, veterans, and military families through employment as General Schedule (GS) employees. The GS is a role classification and pay system that covers most federal employees in professional, administrative, and technical positions (eg, physicians). The GS system classifies most of these employees based on the complexity, responsibility, and qualifications required for their role.9 Such positions often are at the highest level of the GS pay scale, reflecting the expertise and years of education required to become a dermatologist, though pay varies by location and experience. In contrast, physicians employed through the VA system are classified as Title 38 federal employees, governed by a different pay structure and regulatory framework under the US Code of Federal Regulations.10 These regulations govern the hiring, retention, and firing guidelines for VA physicians, which differ from those of GS physicians. A full explanation is outside of the scope of this article, however.

Final Thoughts

In summary, uniformed or federal service as a dermatologist offers a meaningful and impactful way to give back to those who have served our country. Opportunities exist throughout the United States for dermatologists interested in serving within the MHS or VA. The most transparent and up-to-date resource for identifying open positions in both large metropolitan areas and smaller communities is USAJOBS.gov. While financial compensation may not always match that of private practice, the intangible benefits are considerable—stable employment, comprehensive benefits, malpractice coverage, and secure retirement, among others. There is something deeply fulfilling about using one’s medical skills in service of a larger mission. The relationships built with service members, the sense of shared purpose, and the opportunity to contribute to the readiness and well-being of those who serve all make this career path profoundly rewarding. For dermatologists seeking a practice that combines professional growth with purpose and patriotism, military medicine offers a truly special calling.

- Military Health System. Elements of the military health system. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/MHS-Elements

- TRICARE. Plans and eligibility. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://tricare.mil/Plans/Eligibility

- Military Benefit. TRICARE for retirees. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.militarybenefit.org/get-educated/tricareforretirees/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Eligibility for VA health care. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA priority groups. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/priority-groups/

- Navy Medicine. Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP) and Financial Assistance Program (FAP). Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.med.navy.mil/Accessions/Health-Professions-Scholarship-Program-HPSP-and-Financial-Assistance-Program-FAP/

- US Navy. Navy Medicine R2DA program. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.navy.com/navy-medicine

- US Army Medical Department. Student programs. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://goamedd.com/student-programs

- US Office of Personnel Management. General Schedule. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/pay-systems/general-schedule/

- Pines Federal Employment Attorneys. Title 38 employees: medical professionals. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.pinesfederal.com/va-federal-employees/title-38-employees-medical-professionals/

Serving those who serve has been one of the most meaningful parts of my career. A career in military medicine offers dermatologists not only a chance to practice within a unique and diverse patient population but also an opportunity to contribute to something larger than themselves. Whether working with active-duty service members and their families within the Military Health System (MHS) or caring for veterans through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the experience can be both enriching and rewarding. This article will explore the various pathways available to dermatologists to serve military communities, whether they are at the start of their careers or are looking for a change of pace within their established practice.

Care Pathways for Military and Veterans

To care for uniformed service members, their families, and retired personnel, dermatologists typically serve within the MHS—a global, integrated network of military hospitals and clinics dedicated to delivering health care to this population.1 TRICARE is the health insurance program that covers those eligible for care within the system, including active-duty and retired service members.2 In this context, it is important to clarify what the term retired actually means, as it differs from the term veteran when it comes to accessing health care options, and these terms frequently are conflated. A retired service member is an individual who completed at least 20 years of active-duty service or who has been medically retired because of a condition or injury incurred while on active duty.3 In contrast, a veteran may not have completed 20 years of service but has separated honorably after serving at least 24 continuous months.4 Veterans typically receive care through the VA system.5

Serving on Active Duty

In general, there are 2 main pathways to serve as a dermatologist within the MHS. The first is to commission in the military and serve on active duty. Most often, this pathway begins with a premedical student applying to medical school. Those considering military service typically explore scholarship programs such as the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP)(https://www.medicineandthemilitary.com/applying-and-what-to-expect/medical-school-programs/hpsp) or the Health Services Collegiate Program (HSCP), or they apply to the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU)(https://www.usuhs.edu/about). The HPSP and HSCP programs financially support medical students training at civilian medical schools, though in different ways—the HPSP covers tuition and fees, while the HSCP provides a salary during training but does not cover tuition.6 In contrast, students of USU attend the nation’s only military medical school, serving in uniform for 4 years while earning the pay and benefits of a junior officer in their respective service branch. Any premedical student considering the HPSP, HSCP or USU routes for service must meet the commissioning standards of their chosen branch—Army, Navy, or Air Force—and enter service as an officer before beginning medical school.

While direct commission prior to medical school is the most common route to active-duty service, board-certified dermatologists also can join a military branch later through what is called Direct Accession or Direct Commission; for example, the Navy offers a Residency to Direct Accession program, which commissions residents in their final year of training to join the Navy upon graduation. In some cases, commissioning at this stage includes a bonus of up to $600,000 in exchange for a 4-year active-duty commitment.7 The Army and Air Force offer similar direct commission programs, though specific incentives vary.8 Interested residents or practitioners can contact a local recruiting office within their branch of interest to learn more. Direct accession is open at many points in a dermatologist’s career—after residency, after fellowship, or even as an established civilian practitioner—and the initial commissioning rank and bonus generally reflect one’s level of experience.

Serving as a Civilian

Outside of uniformed service, dermatologists can find opportunities to provide care for active-duty service members, veterans, and military families through employment as General Schedule (GS) employees. The GS is a role classification and pay system that covers most federal employees in professional, administrative, and technical positions (eg, physicians). The GS system classifies most of these employees based on the complexity, responsibility, and qualifications required for their role.9 Such positions often are at the highest level of the GS pay scale, reflecting the expertise and years of education required to become a dermatologist, though pay varies by location and experience. In contrast, physicians employed through the VA system are classified as Title 38 federal employees, governed by a different pay structure and regulatory framework under the US Code of Federal Regulations.10 These regulations govern the hiring, retention, and firing guidelines for VA physicians, which differ from those of GS physicians. A full explanation is outside of the scope of this article, however.

Final Thoughts

In summary, uniformed or federal service as a dermatologist offers a meaningful and impactful way to give back to those who have served our country. Opportunities exist throughout the United States for dermatologists interested in serving within the MHS or VA. The most transparent and up-to-date resource for identifying open positions in both large metropolitan areas and smaller communities is USAJOBS.gov. While financial compensation may not always match that of private practice, the intangible benefits are considerable—stable employment, comprehensive benefits, malpractice coverage, and secure retirement, among others. There is something deeply fulfilling about using one’s medical skills in service of a larger mission. The relationships built with service members, the sense of shared purpose, and the opportunity to contribute to the readiness and well-being of those who serve all make this career path profoundly rewarding. For dermatologists seeking a practice that combines professional growth with purpose and patriotism, military medicine offers a truly special calling.

Serving those who serve has been one of the most meaningful parts of my career. A career in military medicine offers dermatologists not only a chance to practice within a unique and diverse patient population but also an opportunity to contribute to something larger than themselves. Whether working with active-duty service members and their families within the Military Health System (MHS) or caring for veterans through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the experience can be both enriching and rewarding. This article will explore the various pathways available to dermatologists to serve military communities, whether they are at the start of their careers or are looking for a change of pace within their established practice.

Care Pathways for Military and Veterans

To care for uniformed service members, their families, and retired personnel, dermatologists typically serve within the MHS—a global, integrated network of military hospitals and clinics dedicated to delivering health care to this population.1 TRICARE is the health insurance program that covers those eligible for care within the system, including active-duty and retired service members.2 In this context, it is important to clarify what the term retired actually means, as it differs from the term veteran when it comes to accessing health care options, and these terms frequently are conflated. A retired service member is an individual who completed at least 20 years of active-duty service or who has been medically retired because of a condition or injury incurred while on active duty.3 In contrast, a veteran may not have completed 20 years of service but has separated honorably after serving at least 24 continuous months.4 Veterans typically receive care through the VA system.5

Serving on Active Duty

In general, there are 2 main pathways to serve as a dermatologist within the MHS. The first is to commission in the military and serve on active duty. Most often, this pathway begins with a premedical student applying to medical school. Those considering military service typically explore scholarship programs such as the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP)(https://www.medicineandthemilitary.com/applying-and-what-to-expect/medical-school-programs/hpsp) or the Health Services Collegiate Program (HSCP), or they apply to the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU)(https://www.usuhs.edu/about). The HPSP and HSCP programs financially support medical students training at civilian medical schools, though in different ways—the HPSP covers tuition and fees, while the HSCP provides a salary during training but does not cover tuition.6 In contrast, students of USU attend the nation’s only military medical school, serving in uniform for 4 years while earning the pay and benefits of a junior officer in their respective service branch. Any premedical student considering the HPSP, HSCP or USU routes for service must meet the commissioning standards of their chosen branch—Army, Navy, or Air Force—and enter service as an officer before beginning medical school.

While direct commission prior to medical school is the most common route to active-duty service, board-certified dermatologists also can join a military branch later through what is called Direct Accession or Direct Commission; for example, the Navy offers a Residency to Direct Accession program, which commissions residents in their final year of training to join the Navy upon graduation. In some cases, commissioning at this stage includes a bonus of up to $600,000 in exchange for a 4-year active-duty commitment.7 The Army and Air Force offer similar direct commission programs, though specific incentives vary.8 Interested residents or practitioners can contact a local recruiting office within their branch of interest to learn more. Direct accession is open at many points in a dermatologist’s career—after residency, after fellowship, or even as an established civilian practitioner—and the initial commissioning rank and bonus generally reflect one’s level of experience.

Serving as a Civilian

Outside of uniformed service, dermatologists can find opportunities to provide care for active-duty service members, veterans, and military families through employment as General Schedule (GS) employees. The GS is a role classification and pay system that covers most federal employees in professional, administrative, and technical positions (eg, physicians). The GS system classifies most of these employees based on the complexity, responsibility, and qualifications required for their role.9 Such positions often are at the highest level of the GS pay scale, reflecting the expertise and years of education required to become a dermatologist, though pay varies by location and experience. In contrast, physicians employed through the VA system are classified as Title 38 federal employees, governed by a different pay structure and regulatory framework under the US Code of Federal Regulations.10 These regulations govern the hiring, retention, and firing guidelines for VA physicians, which differ from those of GS physicians. A full explanation is outside of the scope of this article, however.

Final Thoughts

In summary, uniformed or federal service as a dermatologist offers a meaningful and impactful way to give back to those who have served our country. Opportunities exist throughout the United States for dermatologists interested in serving within the MHS or VA. The most transparent and up-to-date resource for identifying open positions in both large metropolitan areas and smaller communities is USAJOBS.gov. While financial compensation may not always match that of private practice, the intangible benefits are considerable—stable employment, comprehensive benefits, malpractice coverage, and secure retirement, among others. There is something deeply fulfilling about using one’s medical skills in service of a larger mission. The relationships built with service members, the sense of shared purpose, and the opportunity to contribute to the readiness and well-being of those who serve all make this career path profoundly rewarding. For dermatologists seeking a practice that combines professional growth with purpose and patriotism, military medicine offers a truly special calling.

- Military Health System. Elements of the military health system. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/MHS-Elements

- TRICARE. Plans and eligibility. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://tricare.mil/Plans/Eligibility

- Military Benefit. TRICARE for retirees. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.militarybenefit.org/get-educated/tricareforretirees/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Eligibility for VA health care. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA priority groups. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/priority-groups/

- Navy Medicine. Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP) and Financial Assistance Program (FAP). Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.med.navy.mil/Accessions/Health-Professions-Scholarship-Program-HPSP-and-Financial-Assistance-Program-FAP/

- US Navy. Navy Medicine R2DA program. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.navy.com/navy-medicine

- US Army Medical Department. Student programs. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://goamedd.com/student-programs

- US Office of Personnel Management. General Schedule. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/pay-systems/general-schedule/

- Pines Federal Employment Attorneys. Title 38 employees: medical professionals. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.pinesfederal.com/va-federal-employees/title-38-employees-medical-professionals/

- Military Health System. Elements of the military health system. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/MHS-Elements

- TRICARE. Plans and eligibility. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://tricare.mil/Plans/Eligibility

- Military Benefit. TRICARE for retirees. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.militarybenefit.org/get-educated/tricareforretirees/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Eligibility for VA health care. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA priority groups. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/priority-groups/

- Navy Medicine. Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP) and Financial Assistance Program (FAP). Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.med.navy.mil/Accessions/Health-Professions-Scholarship-Program-HPSP-and-Financial-Assistance-Program-FAP/

- US Navy. Navy Medicine R2DA program. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.navy.com/navy-medicine

- US Army Medical Department. Student programs. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://goamedd.com/student-programs

- US Office of Personnel Management. General Schedule. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/pay-systems/general-schedule/

- Pines Federal Employment Attorneys. Title 38 employees: medical professionals. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://www.pinesfederal.com/va-federal-employees/title-38-employees-medical-professionals/

Dermatology on Duty: Pathways to a Career in Military Medicine

Dermatology on Duty: Pathways to a Career in Military Medicine

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists have diverse pathways to serve the military and veteran communities, either in uniform or as civilians.

- For those considering a military career, options include medical school scholarships or direct commission after residency.

- Those who prefer to remain civilians can find employment opportunities with the Military Heath System or the Department of Veterans Affairs that provide a way to care for this population without a service commitment.

The Habit of Curiosity: How Writing Shapes Clinical Thinking in Medical Training

The Habit of Curiosity: How Writing Shapes Clinical Thinking in Medical Training

I was accepted into my fellowship almost 1 year ago: major milestones on my curriculum vitae are now met, fellowship application materials are complete, and the stress of the match is long gone. At the start of my fellowship, I had 2 priorities: (1) to learn as much as I could about dermatologic surgery and (2) to be the best dad possible to my newborn son, Jay. However, most nights I still find myself up late editing a manuscript draft or chasing down references, long after the “need” to publish has passed. Recently, my wife asked me why—what’s left to prove?

I’ll be the first to admit it: early on, publishing felt almost purely transactional. Each project was little more than a line on an application or a way to stand out or meet a new mentor. I have reflected before on how easily that mindset can slip into a kind of research arms race, in which productivity overshadows purpose.1 This time, I wanted to explore the other side of that equation: the “why” behind it all.

I have learned that writing forces me to slow down and actually think about what I am seeing every day. It turns routine work into something I must understand well enough to explain. Even a small write-up can make me notice details I would otherwise skim past in clinic or surgery. These days, most of my projects start small: a case that taught me something, an observation that made me pause and think. Those seemingly small questions are what eventually grow into bigger ones. The clinical trial I am designing now did not begin as a grand plan—it started because I could not stop thinking about how we manage pain and analgesia after Mohs surgery. That curiosity, shaped by the experience of writing those earlier “smaller” papers, evolved into a study that might actually help improve patient care one day. Still, most of what I write will not revolutionize the field. It is not cutting-edge science or paradigm-shifting data; it is mostly modest analyses with a few interesting conclusions or surgical pearls that might cut down on a patient’s procedural time or save a dermatologist somewhere a few sutures. But it still feels worth doing.

While rotating with Dr. Anna Bar at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, I noticed a poster hanging on the wall titled, “Top 10 Reasons Why Our Faculty Are Dedicated to Academics and Teaching,” based on the wisdom of Dr. Jane M. Grant-Kels.2 My favorite line on the poster reads, “Residents make us better by asking questions.” I think this philosophy is the main reason why I still write. Even though I am not a resident anymore, I am still asking questions. But if I had to sum up my “why” into a neat list, here is what it might look like:

Because asking questions keeps your brain wired for curiosity. Even small projects train us to remain curious, and this curiosity can mean the difference between just doing your job and continuing to evolve within it. As Dr. Rodolfo Neirotti reminds us, “Questions are useful tools—they open communication, improve understanding, and drive scientific research. In medicine, doing things without knowing why is risky.”3

Because the small stuff builds the culture. Dermatology is a small world. Even short case series, pearls, or “how we do it” pieces can shape how we practice. They may not change paradigms, but they can refine them. Over time, those small practical contributions become part of the field’s collective muscle memory.

Because it preserves perspective. Residency, fellowship, and early practice can blur together. A tiny project can become a timestamp of what you were learning or caring about at that specific moment. Years later, you may remember the case through the paper.

Because the act of writing is the point. Writing forces clarity. You cannot hide behind saying, “That’s just how I do things,” when you have to explain it to others. The discipline of organizing your thoughts sharpens your clinical reasoning and keeps you honest about what you actually know.

Because sometimes it is simply about participating. Publishing, even small pieces, is a way of staying in touch with your field. It says, “I’m still here. I’m still paying attention.”

I think about how Dr. Frederic Mohs developed the technique that now bears his name while he was still a medical student.4 He could have said, “I already made it into medical school. That’s enough.” But he did not. I guess my point is not that we are all on the verge of inventing something revolutionary; it is that innovation happens only when curiosity keeps moving us forward. So no, I do not write to check boxes anymore. I write because it keeps me curious, and I have realized that curiosity is a habit I never want to outgrow.

Or maybe it’s because Jay keeps me up at night, and I have nothing better to do.

- Jeha GM. A roadmap to research opportunities for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2024;114:E53-E56.

- Grant-Kels J. The gift that keeps on giving. UConn Health Dermatology. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://health.uconn.edu/dermatology/education/

- Neirotti RA. The importance of asking questions and doing things for a reason. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;36:I-II.

- Trost LB, Bailin PL. History of Mohs surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:135-139, vii.

I was accepted into my fellowship almost 1 year ago: major milestones on my curriculum vitae are now met, fellowship application materials are complete, and the stress of the match is long gone. At the start of my fellowship, I had 2 priorities: (1) to learn as much as I could about dermatologic surgery and (2) to be the best dad possible to my newborn son, Jay. However, most nights I still find myself up late editing a manuscript draft or chasing down references, long after the “need” to publish has passed. Recently, my wife asked me why—what’s left to prove?

I’ll be the first to admit it: early on, publishing felt almost purely transactional. Each project was little more than a line on an application or a way to stand out or meet a new mentor. I have reflected before on how easily that mindset can slip into a kind of research arms race, in which productivity overshadows purpose.1 This time, I wanted to explore the other side of that equation: the “why” behind it all.

I have learned that writing forces me to slow down and actually think about what I am seeing every day. It turns routine work into something I must understand well enough to explain. Even a small write-up can make me notice details I would otherwise skim past in clinic or surgery. These days, most of my projects start small: a case that taught me something, an observation that made me pause and think. Those seemingly small questions are what eventually grow into bigger ones. The clinical trial I am designing now did not begin as a grand plan—it started because I could not stop thinking about how we manage pain and analgesia after Mohs surgery. That curiosity, shaped by the experience of writing those earlier “smaller” papers, evolved into a study that might actually help improve patient care one day. Still, most of what I write will not revolutionize the field. It is not cutting-edge science or paradigm-shifting data; it is mostly modest analyses with a few interesting conclusions or surgical pearls that might cut down on a patient’s procedural time or save a dermatologist somewhere a few sutures. But it still feels worth doing.

While rotating with Dr. Anna Bar at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, I noticed a poster hanging on the wall titled, “Top 10 Reasons Why Our Faculty Are Dedicated to Academics and Teaching,” based on the wisdom of Dr. Jane M. Grant-Kels.2 My favorite line on the poster reads, “Residents make us better by asking questions.” I think this philosophy is the main reason why I still write. Even though I am not a resident anymore, I am still asking questions. But if I had to sum up my “why” into a neat list, here is what it might look like:

Because asking questions keeps your brain wired for curiosity. Even small projects train us to remain curious, and this curiosity can mean the difference between just doing your job and continuing to evolve within it. As Dr. Rodolfo Neirotti reminds us, “Questions are useful tools—they open communication, improve understanding, and drive scientific research. In medicine, doing things without knowing why is risky.”3

Because the small stuff builds the culture. Dermatology is a small world. Even short case series, pearls, or “how we do it” pieces can shape how we practice. They may not change paradigms, but they can refine them. Over time, those small practical contributions become part of the field’s collective muscle memory.

Because it preserves perspective. Residency, fellowship, and early practice can blur together. A tiny project can become a timestamp of what you were learning or caring about at that specific moment. Years later, you may remember the case through the paper.

Because the act of writing is the point. Writing forces clarity. You cannot hide behind saying, “That’s just how I do things,” when you have to explain it to others. The discipline of organizing your thoughts sharpens your clinical reasoning and keeps you honest about what you actually know.

Because sometimes it is simply about participating. Publishing, even small pieces, is a way of staying in touch with your field. It says, “I’m still here. I’m still paying attention.”

I think about how Dr. Frederic Mohs developed the technique that now bears his name while he was still a medical student.4 He could have said, “I already made it into medical school. That’s enough.” But he did not. I guess my point is not that we are all on the verge of inventing something revolutionary; it is that innovation happens only when curiosity keeps moving us forward. So no, I do not write to check boxes anymore. I write because it keeps me curious, and I have realized that curiosity is a habit I never want to outgrow.

Or maybe it’s because Jay keeps me up at night, and I have nothing better to do.

I was accepted into my fellowship almost 1 year ago: major milestones on my curriculum vitae are now met, fellowship application materials are complete, and the stress of the match is long gone. At the start of my fellowship, I had 2 priorities: (1) to learn as much as I could about dermatologic surgery and (2) to be the best dad possible to my newborn son, Jay. However, most nights I still find myself up late editing a manuscript draft or chasing down references, long after the “need” to publish has passed. Recently, my wife asked me why—what’s left to prove?

I’ll be the first to admit it: early on, publishing felt almost purely transactional. Each project was little more than a line on an application or a way to stand out or meet a new mentor. I have reflected before on how easily that mindset can slip into a kind of research arms race, in which productivity overshadows purpose.1 This time, I wanted to explore the other side of that equation: the “why” behind it all.

I have learned that writing forces me to slow down and actually think about what I am seeing every day. It turns routine work into something I must understand well enough to explain. Even a small write-up can make me notice details I would otherwise skim past in clinic or surgery. These days, most of my projects start small: a case that taught me something, an observation that made me pause and think. Those seemingly small questions are what eventually grow into bigger ones. The clinical trial I am designing now did not begin as a grand plan—it started because I could not stop thinking about how we manage pain and analgesia after Mohs surgery. That curiosity, shaped by the experience of writing those earlier “smaller” papers, evolved into a study that might actually help improve patient care one day. Still, most of what I write will not revolutionize the field. It is not cutting-edge science or paradigm-shifting data; it is mostly modest analyses with a few interesting conclusions or surgical pearls that might cut down on a patient’s procedural time or save a dermatologist somewhere a few sutures. But it still feels worth doing.

While rotating with Dr. Anna Bar at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, I noticed a poster hanging on the wall titled, “Top 10 Reasons Why Our Faculty Are Dedicated to Academics and Teaching,” based on the wisdom of Dr. Jane M. Grant-Kels.2 My favorite line on the poster reads, “Residents make us better by asking questions.” I think this philosophy is the main reason why I still write. Even though I am not a resident anymore, I am still asking questions. But if I had to sum up my “why” into a neat list, here is what it might look like:

Because asking questions keeps your brain wired for curiosity. Even small projects train us to remain curious, and this curiosity can mean the difference between just doing your job and continuing to evolve within it. As Dr. Rodolfo Neirotti reminds us, “Questions are useful tools—they open communication, improve understanding, and drive scientific research. In medicine, doing things without knowing why is risky.”3

Because the small stuff builds the culture. Dermatology is a small world. Even short case series, pearls, or “how we do it” pieces can shape how we practice. They may not change paradigms, but they can refine them. Over time, those small practical contributions become part of the field’s collective muscle memory.

Because it preserves perspective. Residency, fellowship, and early practice can blur together. A tiny project can become a timestamp of what you were learning or caring about at that specific moment. Years later, you may remember the case through the paper.

Because the act of writing is the point. Writing forces clarity. You cannot hide behind saying, “That’s just how I do things,” when you have to explain it to others. The discipline of organizing your thoughts sharpens your clinical reasoning and keeps you honest about what you actually know.

Because sometimes it is simply about participating. Publishing, even small pieces, is a way of staying in touch with your field. It says, “I’m still here. I’m still paying attention.”

I think about how Dr. Frederic Mohs developed the technique that now bears his name while he was still a medical student.4 He could have said, “I already made it into medical school. That’s enough.” But he did not. I guess my point is not that we are all on the verge of inventing something revolutionary; it is that innovation happens only when curiosity keeps moving us forward. So no, I do not write to check boxes anymore. I write because it keeps me curious, and I have realized that curiosity is a habit I never want to outgrow.

Or maybe it’s because Jay keeps me up at night, and I have nothing better to do.

- Jeha GM. A roadmap to research opportunities for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2024;114:E53-E56.