User login

The Road Less Traveled: Why Rural Dermatology Could Be Your Path After Residency

The Road Less Traveled: Why Rural Dermatology Could Be Your Path After Residency

The myths persist: You will lack colleagues. Your practice will be thin. You must sacrifice academic engagement. In reality, rural practice offers variety, leadership opportunities, and the chance to influence the health of entire communities in profound ways. In this article, we aim to unpack what rural dermatology actually looks like as a potential career path for residents, with a focus on private-academic hybrid and hospital-based practice models.

Definitions of the term rural vary. For the US Census Bureau, it is synonymous with nonurban, and for the Office of Management and Budget, the term nonmetropolitan is preferred. The US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes recognize a continuum of classifications from micropolitan to remote. In practice, the term rural covers a wide spectrum: the rolling farmlands of the Midwest, the mountains of Montana, the bayous of the South, the Native American reservations in New Mexico, and everything in between. It is not one uniform reality—rural America is diverse, resilient, and deeply connected.

Daily clinic flow may look familiar: a full schedule, a mix of new and established patients, and frequent simple procedures such as biopsies and corticosteroid injections. But the scope of practice is wider. You become the dermatologist for hundreds of miles in every direction, managing most conditions locally while referring select cases to subspecialty centers.

Case variety is striking. Neglected tumors, unusual inflammatory presentations, pediatric conditions, and occupational dermatoses/injuries appear alongside the routine. Each day requires flexibility, judgment, confidence, and the ability to think outside the box. You must consider how a patient’s seasonal work, such as ranching or farming, and/or their total commute time impacts the risk-benefit discussion around treatment recommendations.

Matthew P. Shaffer, MD (Salina, Kansas), who has practiced rural dermatology for more than 20 years, explained that the breadth of dermatologic cases in which he served as the expert was both exciting and intimidating, but it became clear that this was the right professional path for him (email communication, September 5, 2025). In small communities, your role extends beyond the clinic walls. You will see patients at the grocery store, the library, and school events. That continuity fosters loyalty and accountability in ways that are hard to quantify.

Many practice structures exist: independent clinics, multispecialty groups, hospital employment, and increasingly, hybrid partnerships with academic centers.

Academic institutions have recognized the importance of rural exposure, and many now collaborate with rural dermatologists. For example, Heartland Dermatology in Salina, Kansas, where 2 of the authors (B.R.L. and T.G.) practice, partners with St. Louis University in Missouri to provide a residency track and rotations in rural clinics.

Rural-based hospital systems can create similar structures. Monument Health Dermatology in Spearfish, South Dakota, is integrated into the fabric of the community’s larger rural health care model. The physician (M.E.L.) collaborates daily with primary care providers, surgeons, and oncologists through a shared electronic health record (sometimes even through telephone speed-dial given the close collegiality of small-town providers). Patients come from across 4 states, some driving 6 hours each way. Patients who once doubted whether dermatology was worth the trip will consistently return for follow-up care once trust is earned. The stability of hospital employment supports volunteer faculty positions and a free satellite clinic in partnership with a local Lakota Tribal health center. There is never a dull day: the providers see urgent add-ons daily, which keeps them on their toes but in exchange brings immense reward. This includes a recent case from rural Wyoming: a complex mixed infantile hemangioma on the mid face just entering the rapid proliferation phase. Propranolol was started immediately, as opposed to months later when it was too late—a common complication for the majority of rural patients by the time to get to a dermatologist.

Complex cases can overwhelm rural practices, and this is when the hub-and-spoke model is invaluable. Dermatologists embed in local communities as spokes, while subspecialty services such as pediatric dermatology, dermatopathology, or Mohs micrographic surgery remain centralized at hubs. The hubs can be but do not have to be academic institutions; for Heartland Dermatology in Kansas, private practices fulfill both hub and spoke roles. With that said, 10 states do not have academic dermatology programs.1 Mohs surgeons and pediatric dermatologists still can establish robust and successful independent rural subspecialty practices outside academic hubs. Christopher Gasbarre, DO (Spearfish, South Dakota), a board-certified, fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon in rural practice, advises residents to be confident in their abilities and to trust their training, noting that they often will be asked to manage complicated cases because of patient travel and cost constraints; however, clinicians should recognize their own limitations and those of nearby specialists and develop a referral network for cases that require multidisciplinary care (text communication, September 14, 2025).

The hub-and-spoke models—whether they entail an academic center as the hub with private practices as the spokes, or a network of private practices that include rural subspecialists—allows rural dermatologists to remain trusted local experts while ensuring that patients can access advanced care via a more streamlined referral process/network. The challenge is triage: what can be managed locally and what must patients travel for? As Dr. Shaffer explained, decisions about whether care is managed locally or referred to a hub often depend on the experience and comfort level of both the physician and the patient (email communication, September 5, 2025). Ultimately, continuity and trust are central. Patients rely on their local dermatologist to guide these decisions, and that guidance makes the model effective.

The idea that rural practice means being stuck in a small solo clinic is outdated. Multiple pathways exist, each with strengths and challenges. Independent private practice offers maximum autonomy and deep community integration, though financial and staffing risks are yours to manage. Hospital employment with outreach clinics provides stability, benefits, and collegiality, but bureaucracy can limit innovation and efficiency. Private equity platforms supply resources and rapid growth, but alignment with mission and autonomy must be weighed carefully. Hybrid joint ventures with hospitals combine private control and institutional support, but contracts can be complex. Locum tenens–to-permanent arrangements let you try rural life with minimal commitment, but continuity with patients may be sacrificed. A self-screener can clarify your path: How much autonomy do I want? Do I prefer predictability or variety? How important are procedures, teaching, or community roles? Answer these questions honestly and pair that insight with mentor guidance.

Launching a rural dermatology clinic is equal parts vision and structure. A focused 90-day plan can make the difference between a smooth opening and early frustration. Think in 4 domains: site selection, employment and licensing, credentialing and contracting, and operations. Even in a compressed timeline, dozens of small but crucial tasks may surface. There are resources—such as the Medical Group Management Association’s practice start-up checklist—that can provide a roadmap, ensuring no detail is overlooked as you transform a vision into a functioning clinic.2

Site Selection—First, determine whether you are opening a new standalone clinic, extending an existing practice, or creating a part-time satellite. Referral mapping with local primary care providers is essential, as is a scan of payer mix and dermatologist density in the region to ensure sustainability.

Employment and Licensing—Confirm state licensure and Drug Enforcement Administration registration and initiate hospital privileges early. These processes can stretch across the entire 90-day window, so starting immediately is critical.

Credentialing and Contracting—Applications with commercial and federal payers, along with Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare updates, often consume weeks if not months. If you plan to perform office microscopy or establish a dermatopathology laboratory, begin the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certification process in parallel.

Operations—Once the regulatory wheels are in motion, shift to building your practice infrastructure. Secure space, weigh lease vs purchase, and consider partnerships with local hospitals for shared clinic facilities. Recruit staff with dermatology-specific skills such as clinical photography and biopsy assistance. Implement an electronic health record, set up payroll and malpractice insurance, and establish supply chains for everything from liquid nitrogen to surgical trays. Decide whether revenue cycle management will be in-house or outsourced and finalize dermatopathology workflows including courier and transport agreements.

Compensation in rural dermatology mirrors that of other clinical settings: base salary with productivity bonuses, revenue pooling, or relative value unit structures. Financial planning is crucial. Develop a pro forma that models patient volume, expenses, and realistic growth. Risks exist, including payer mix, staffing, and competition, but the demand for care in underserved areas often offsets these, and communities may support practices with reduced overhead and strong loyalty. Hospital systems may add stipends for supervising advanced practitioners or outreach travel. Loan repayment programs, tax credits, and grants can further enhance packages. Consider checking with the state’s Office of Rural Health.

Career sustainability ultimately depends on more than finances. Geography, amenities, schedule flexibility, autonomy in medical decision-making, work-life balance, the value of being part of and serving a community, and other personal values will shape your “best-fit” practice model. Ask whether you can envision yourself thriving in the community you would be serving.

No one builds a rural dermatology practice alone. That is why one of the authors (M.E.L.) created the Rural Access to Dermatology Society (https://www.radsociety.org/), a nonprofit organization connecting dermatologists, residents, and medical students with a shared mission. The organization supports residents through scholarships, mentorship, and telementoring. Faculty can contribute through advocacy, residency track development, and outreach to uniquely underserved rural populations such as Native American reservations where access to dermatology care remains severely limited. Joining can be as simple as attending a webinar, finding a mentor, or volunteering at a free clinic. You do not need to launch your own clinic to get involved; you can begin by connecting with a network already laying the foundation.

Teledermatology and academic initiatives enhance rural care but do not replace in-person practice. Store-and-forward consultations extend reach but cannot match the continuity and trust of long-term patient relationships. Academic rural tracks prepare residents for unique challenges, but someone must staff the clinics. Private and hybrid models remain the backbone of rural access, where dermatologists take on the responsibility and the joy of being the local expert.

So here’s the invitation: bring one question to your mentor about rural practice and identify one rural site you could visit. The road less traveled in dermatology is closer than you think—and it might just be your path.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. ERAS Directory: Dermatology. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://systems.aamc.org/eras/erasstats/par/display.cfm?NAV_ROW=PAR&SPEC_CD=080

- Medical Group Management Association. Large group or organization practice startup checklist. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.mgma.com/member-tools/large-group-or-organization -practice-startup-checklist

The myths persist: You will lack colleagues. Your practice will be thin. You must sacrifice academic engagement. In reality, rural practice offers variety, leadership opportunities, and the chance to influence the health of entire communities in profound ways. In this article, we aim to unpack what rural dermatology actually looks like as a potential career path for residents, with a focus on private-academic hybrid and hospital-based practice models.

Definitions of the term rural vary. For the US Census Bureau, it is synonymous with nonurban, and for the Office of Management and Budget, the term nonmetropolitan is preferred. The US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes recognize a continuum of classifications from micropolitan to remote. In practice, the term rural covers a wide spectrum: the rolling farmlands of the Midwest, the mountains of Montana, the bayous of the South, the Native American reservations in New Mexico, and everything in between. It is not one uniform reality—rural America is diverse, resilient, and deeply connected.

Daily clinic flow may look familiar: a full schedule, a mix of new and established patients, and frequent simple procedures such as biopsies and corticosteroid injections. But the scope of practice is wider. You become the dermatologist for hundreds of miles in every direction, managing most conditions locally while referring select cases to subspecialty centers.

Case variety is striking. Neglected tumors, unusual inflammatory presentations, pediatric conditions, and occupational dermatoses/injuries appear alongside the routine. Each day requires flexibility, judgment, confidence, and the ability to think outside the box. You must consider how a patient’s seasonal work, such as ranching or farming, and/or their total commute time impacts the risk-benefit discussion around treatment recommendations.

Matthew P. Shaffer, MD (Salina, Kansas), who has practiced rural dermatology for more than 20 years, explained that the breadth of dermatologic cases in which he served as the expert was both exciting and intimidating, but it became clear that this was the right professional path for him (email communication, September 5, 2025). In small communities, your role extends beyond the clinic walls. You will see patients at the grocery store, the library, and school events. That continuity fosters loyalty and accountability in ways that are hard to quantify.

Many practice structures exist: independent clinics, multispecialty groups, hospital employment, and increasingly, hybrid partnerships with academic centers.

Academic institutions have recognized the importance of rural exposure, and many now collaborate with rural dermatologists. For example, Heartland Dermatology in Salina, Kansas, where 2 of the authors (B.R.L. and T.G.) practice, partners with St. Louis University in Missouri to provide a residency track and rotations in rural clinics.

Rural-based hospital systems can create similar structures. Monument Health Dermatology in Spearfish, South Dakota, is integrated into the fabric of the community’s larger rural health care model. The physician (M.E.L.) collaborates daily with primary care providers, surgeons, and oncologists through a shared electronic health record (sometimes even through telephone speed-dial given the close collegiality of small-town providers). Patients come from across 4 states, some driving 6 hours each way. Patients who once doubted whether dermatology was worth the trip will consistently return for follow-up care once trust is earned. The stability of hospital employment supports volunteer faculty positions and a free satellite clinic in partnership with a local Lakota Tribal health center. There is never a dull day: the providers see urgent add-ons daily, which keeps them on their toes but in exchange brings immense reward. This includes a recent case from rural Wyoming: a complex mixed infantile hemangioma on the mid face just entering the rapid proliferation phase. Propranolol was started immediately, as opposed to months later when it was too late—a common complication for the majority of rural patients by the time to get to a dermatologist.

Complex cases can overwhelm rural practices, and this is when the hub-and-spoke model is invaluable. Dermatologists embed in local communities as spokes, while subspecialty services such as pediatric dermatology, dermatopathology, or Mohs micrographic surgery remain centralized at hubs. The hubs can be but do not have to be academic institutions; for Heartland Dermatology in Kansas, private practices fulfill both hub and spoke roles. With that said, 10 states do not have academic dermatology programs.1 Mohs surgeons and pediatric dermatologists still can establish robust and successful independent rural subspecialty practices outside academic hubs. Christopher Gasbarre, DO (Spearfish, South Dakota), a board-certified, fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon in rural practice, advises residents to be confident in their abilities and to trust their training, noting that they often will be asked to manage complicated cases because of patient travel and cost constraints; however, clinicians should recognize their own limitations and those of nearby specialists and develop a referral network for cases that require multidisciplinary care (text communication, September 14, 2025).

The hub-and-spoke models—whether they entail an academic center as the hub with private practices as the spokes, or a network of private practices that include rural subspecialists—allows rural dermatologists to remain trusted local experts while ensuring that patients can access advanced care via a more streamlined referral process/network. The challenge is triage: what can be managed locally and what must patients travel for? As Dr. Shaffer explained, decisions about whether care is managed locally or referred to a hub often depend on the experience and comfort level of both the physician and the patient (email communication, September 5, 2025). Ultimately, continuity and trust are central. Patients rely on their local dermatologist to guide these decisions, and that guidance makes the model effective.

The idea that rural practice means being stuck in a small solo clinic is outdated. Multiple pathways exist, each with strengths and challenges. Independent private practice offers maximum autonomy and deep community integration, though financial and staffing risks are yours to manage. Hospital employment with outreach clinics provides stability, benefits, and collegiality, but bureaucracy can limit innovation and efficiency. Private equity platforms supply resources and rapid growth, but alignment with mission and autonomy must be weighed carefully. Hybrid joint ventures with hospitals combine private control and institutional support, but contracts can be complex. Locum tenens–to-permanent arrangements let you try rural life with minimal commitment, but continuity with patients may be sacrificed. A self-screener can clarify your path: How much autonomy do I want? Do I prefer predictability or variety? How important are procedures, teaching, or community roles? Answer these questions honestly and pair that insight with mentor guidance.

Launching a rural dermatology clinic is equal parts vision and structure. A focused 90-day plan can make the difference between a smooth opening and early frustration. Think in 4 domains: site selection, employment and licensing, credentialing and contracting, and operations. Even in a compressed timeline, dozens of small but crucial tasks may surface. There are resources—such as the Medical Group Management Association’s practice start-up checklist—that can provide a roadmap, ensuring no detail is overlooked as you transform a vision into a functioning clinic.2

Site Selection—First, determine whether you are opening a new standalone clinic, extending an existing practice, or creating a part-time satellite. Referral mapping with local primary care providers is essential, as is a scan of payer mix and dermatologist density in the region to ensure sustainability.

Employment and Licensing—Confirm state licensure and Drug Enforcement Administration registration and initiate hospital privileges early. These processes can stretch across the entire 90-day window, so starting immediately is critical.

Credentialing and Contracting—Applications with commercial and federal payers, along with Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare updates, often consume weeks if not months. If you plan to perform office microscopy or establish a dermatopathology laboratory, begin the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certification process in parallel.

Operations—Once the regulatory wheels are in motion, shift to building your practice infrastructure. Secure space, weigh lease vs purchase, and consider partnerships with local hospitals for shared clinic facilities. Recruit staff with dermatology-specific skills such as clinical photography and biopsy assistance. Implement an electronic health record, set up payroll and malpractice insurance, and establish supply chains for everything from liquid nitrogen to surgical trays. Decide whether revenue cycle management will be in-house or outsourced and finalize dermatopathology workflows including courier and transport agreements.

Compensation in rural dermatology mirrors that of other clinical settings: base salary with productivity bonuses, revenue pooling, or relative value unit structures. Financial planning is crucial. Develop a pro forma that models patient volume, expenses, and realistic growth. Risks exist, including payer mix, staffing, and competition, but the demand for care in underserved areas often offsets these, and communities may support practices with reduced overhead and strong loyalty. Hospital systems may add stipends for supervising advanced practitioners or outreach travel. Loan repayment programs, tax credits, and grants can further enhance packages. Consider checking with the state’s Office of Rural Health.

Career sustainability ultimately depends on more than finances. Geography, amenities, schedule flexibility, autonomy in medical decision-making, work-life balance, the value of being part of and serving a community, and other personal values will shape your “best-fit” practice model. Ask whether you can envision yourself thriving in the community you would be serving.

No one builds a rural dermatology practice alone. That is why one of the authors (M.E.L.) created the Rural Access to Dermatology Society (https://www.radsociety.org/), a nonprofit organization connecting dermatologists, residents, and medical students with a shared mission. The organization supports residents through scholarships, mentorship, and telementoring. Faculty can contribute through advocacy, residency track development, and outreach to uniquely underserved rural populations such as Native American reservations where access to dermatology care remains severely limited. Joining can be as simple as attending a webinar, finding a mentor, or volunteering at a free clinic. You do not need to launch your own clinic to get involved; you can begin by connecting with a network already laying the foundation.

Teledermatology and academic initiatives enhance rural care but do not replace in-person practice. Store-and-forward consultations extend reach but cannot match the continuity and trust of long-term patient relationships. Academic rural tracks prepare residents for unique challenges, but someone must staff the clinics. Private and hybrid models remain the backbone of rural access, where dermatologists take on the responsibility and the joy of being the local expert.

So here’s the invitation: bring one question to your mentor about rural practice and identify one rural site you could visit. The road less traveled in dermatology is closer than you think—and it might just be your path.

The myths persist: You will lack colleagues. Your practice will be thin. You must sacrifice academic engagement. In reality, rural practice offers variety, leadership opportunities, and the chance to influence the health of entire communities in profound ways. In this article, we aim to unpack what rural dermatology actually looks like as a potential career path for residents, with a focus on private-academic hybrid and hospital-based practice models.

Definitions of the term rural vary. For the US Census Bureau, it is synonymous with nonurban, and for the Office of Management and Budget, the term nonmetropolitan is preferred. The US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes recognize a continuum of classifications from micropolitan to remote. In practice, the term rural covers a wide spectrum: the rolling farmlands of the Midwest, the mountains of Montana, the bayous of the South, the Native American reservations in New Mexico, and everything in between. It is not one uniform reality—rural America is diverse, resilient, and deeply connected.

Daily clinic flow may look familiar: a full schedule, a mix of new and established patients, and frequent simple procedures such as biopsies and corticosteroid injections. But the scope of practice is wider. You become the dermatologist for hundreds of miles in every direction, managing most conditions locally while referring select cases to subspecialty centers.

Case variety is striking. Neglected tumors, unusual inflammatory presentations, pediatric conditions, and occupational dermatoses/injuries appear alongside the routine. Each day requires flexibility, judgment, confidence, and the ability to think outside the box. You must consider how a patient’s seasonal work, such as ranching or farming, and/or their total commute time impacts the risk-benefit discussion around treatment recommendations.

Matthew P. Shaffer, MD (Salina, Kansas), who has practiced rural dermatology for more than 20 years, explained that the breadth of dermatologic cases in which he served as the expert was both exciting and intimidating, but it became clear that this was the right professional path for him (email communication, September 5, 2025). In small communities, your role extends beyond the clinic walls. You will see patients at the grocery store, the library, and school events. That continuity fosters loyalty and accountability in ways that are hard to quantify.

Many practice structures exist: independent clinics, multispecialty groups, hospital employment, and increasingly, hybrid partnerships with academic centers.

Academic institutions have recognized the importance of rural exposure, and many now collaborate with rural dermatologists. For example, Heartland Dermatology in Salina, Kansas, where 2 of the authors (B.R.L. and T.G.) practice, partners with St. Louis University in Missouri to provide a residency track and rotations in rural clinics.

Rural-based hospital systems can create similar structures. Monument Health Dermatology in Spearfish, South Dakota, is integrated into the fabric of the community’s larger rural health care model. The physician (M.E.L.) collaborates daily with primary care providers, surgeons, and oncologists through a shared electronic health record (sometimes even through telephone speed-dial given the close collegiality of small-town providers). Patients come from across 4 states, some driving 6 hours each way. Patients who once doubted whether dermatology was worth the trip will consistently return for follow-up care once trust is earned. The stability of hospital employment supports volunteer faculty positions and a free satellite clinic in partnership with a local Lakota Tribal health center. There is never a dull day: the providers see urgent add-ons daily, which keeps them on their toes but in exchange brings immense reward. This includes a recent case from rural Wyoming: a complex mixed infantile hemangioma on the mid face just entering the rapid proliferation phase. Propranolol was started immediately, as opposed to months later when it was too late—a common complication for the majority of rural patients by the time to get to a dermatologist.

Complex cases can overwhelm rural practices, and this is when the hub-and-spoke model is invaluable. Dermatologists embed in local communities as spokes, while subspecialty services such as pediatric dermatology, dermatopathology, or Mohs micrographic surgery remain centralized at hubs. The hubs can be but do not have to be academic institutions; for Heartland Dermatology in Kansas, private practices fulfill both hub and spoke roles. With that said, 10 states do not have academic dermatology programs.1 Mohs surgeons and pediatric dermatologists still can establish robust and successful independent rural subspecialty practices outside academic hubs. Christopher Gasbarre, DO (Spearfish, South Dakota), a board-certified, fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon in rural practice, advises residents to be confident in their abilities and to trust their training, noting that they often will be asked to manage complicated cases because of patient travel and cost constraints; however, clinicians should recognize their own limitations and those of nearby specialists and develop a referral network for cases that require multidisciplinary care (text communication, September 14, 2025).

The hub-and-spoke models—whether they entail an academic center as the hub with private practices as the spokes, or a network of private practices that include rural subspecialists—allows rural dermatologists to remain trusted local experts while ensuring that patients can access advanced care via a more streamlined referral process/network. The challenge is triage: what can be managed locally and what must patients travel for? As Dr. Shaffer explained, decisions about whether care is managed locally or referred to a hub often depend on the experience and comfort level of both the physician and the patient (email communication, September 5, 2025). Ultimately, continuity and trust are central. Patients rely on their local dermatologist to guide these decisions, and that guidance makes the model effective.

The idea that rural practice means being stuck in a small solo clinic is outdated. Multiple pathways exist, each with strengths and challenges. Independent private practice offers maximum autonomy and deep community integration, though financial and staffing risks are yours to manage. Hospital employment with outreach clinics provides stability, benefits, and collegiality, but bureaucracy can limit innovation and efficiency. Private equity platforms supply resources and rapid growth, but alignment with mission and autonomy must be weighed carefully. Hybrid joint ventures with hospitals combine private control and institutional support, but contracts can be complex. Locum tenens–to-permanent arrangements let you try rural life with minimal commitment, but continuity with patients may be sacrificed. A self-screener can clarify your path: How much autonomy do I want? Do I prefer predictability or variety? How important are procedures, teaching, or community roles? Answer these questions honestly and pair that insight with mentor guidance.

Launching a rural dermatology clinic is equal parts vision and structure. A focused 90-day plan can make the difference between a smooth opening and early frustration. Think in 4 domains: site selection, employment and licensing, credentialing and contracting, and operations. Even in a compressed timeline, dozens of small but crucial tasks may surface. There are resources—such as the Medical Group Management Association’s practice start-up checklist—that can provide a roadmap, ensuring no detail is overlooked as you transform a vision into a functioning clinic.2

Site Selection—First, determine whether you are opening a new standalone clinic, extending an existing practice, or creating a part-time satellite. Referral mapping with local primary care providers is essential, as is a scan of payer mix and dermatologist density in the region to ensure sustainability.

Employment and Licensing—Confirm state licensure and Drug Enforcement Administration registration and initiate hospital privileges early. These processes can stretch across the entire 90-day window, so starting immediately is critical.

Credentialing and Contracting—Applications with commercial and federal payers, along with Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare updates, often consume weeks if not months. If you plan to perform office microscopy or establish a dermatopathology laboratory, begin the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certification process in parallel.

Operations—Once the regulatory wheels are in motion, shift to building your practice infrastructure. Secure space, weigh lease vs purchase, and consider partnerships with local hospitals for shared clinic facilities. Recruit staff with dermatology-specific skills such as clinical photography and biopsy assistance. Implement an electronic health record, set up payroll and malpractice insurance, and establish supply chains for everything from liquid nitrogen to surgical trays. Decide whether revenue cycle management will be in-house or outsourced and finalize dermatopathology workflows including courier and transport agreements.

Compensation in rural dermatology mirrors that of other clinical settings: base salary with productivity bonuses, revenue pooling, or relative value unit structures. Financial planning is crucial. Develop a pro forma that models patient volume, expenses, and realistic growth. Risks exist, including payer mix, staffing, and competition, but the demand for care in underserved areas often offsets these, and communities may support practices with reduced overhead and strong loyalty. Hospital systems may add stipends for supervising advanced practitioners or outreach travel. Loan repayment programs, tax credits, and grants can further enhance packages. Consider checking with the state’s Office of Rural Health.

Career sustainability ultimately depends on more than finances. Geography, amenities, schedule flexibility, autonomy in medical decision-making, work-life balance, the value of being part of and serving a community, and other personal values will shape your “best-fit” practice model. Ask whether you can envision yourself thriving in the community you would be serving.

No one builds a rural dermatology practice alone. That is why one of the authors (M.E.L.) created the Rural Access to Dermatology Society (https://www.radsociety.org/), a nonprofit organization connecting dermatologists, residents, and medical students with a shared mission. The organization supports residents through scholarships, mentorship, and telementoring. Faculty can contribute through advocacy, residency track development, and outreach to uniquely underserved rural populations such as Native American reservations where access to dermatology care remains severely limited. Joining can be as simple as attending a webinar, finding a mentor, or volunteering at a free clinic. You do not need to launch your own clinic to get involved; you can begin by connecting with a network already laying the foundation.

Teledermatology and academic initiatives enhance rural care but do not replace in-person practice. Store-and-forward consultations extend reach but cannot match the continuity and trust of long-term patient relationships. Academic rural tracks prepare residents for unique challenges, but someone must staff the clinics. Private and hybrid models remain the backbone of rural access, where dermatologists take on the responsibility and the joy of being the local expert.

So here’s the invitation: bring one question to your mentor about rural practice and identify one rural site you could visit. The road less traveled in dermatology is closer than you think—and it might just be your path.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. ERAS Directory: Dermatology. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://systems.aamc.org/eras/erasstats/par/display.cfm?NAV_ROW=PAR&SPEC_CD=080

- Medical Group Management Association. Large group or organization practice startup checklist. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.mgma.com/member-tools/large-group-or-organization -practice-startup-checklist

- Association of American Medical Colleges. ERAS Directory: Dermatology. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://systems.aamc.org/eras/erasstats/par/display.cfm?NAV_ROW=PAR&SPEC_CD=080

- Medical Group Management Association. Large group or organization practice startup checklist. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.mgma.com/member-tools/large-group-or-organization -practice-startup-checklist

The Road Less Traveled: Why Rural Dermatology Could Be Your Path After Residency

The Road Less Traveled: Why Rural Dermatology Could Be Your Path After Residency

Cobblestonelike Papules on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Fibroelastolytic Papulosis

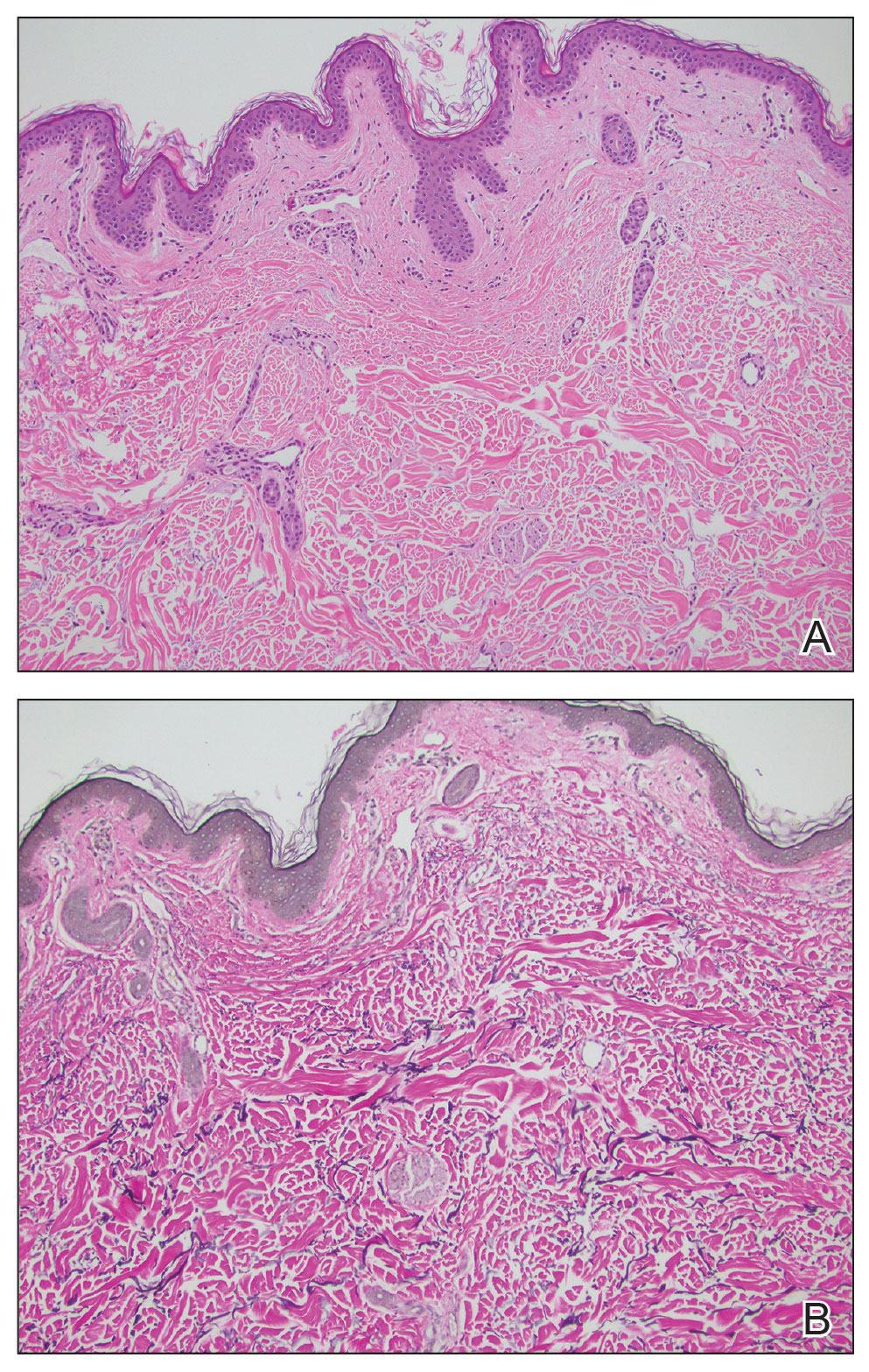

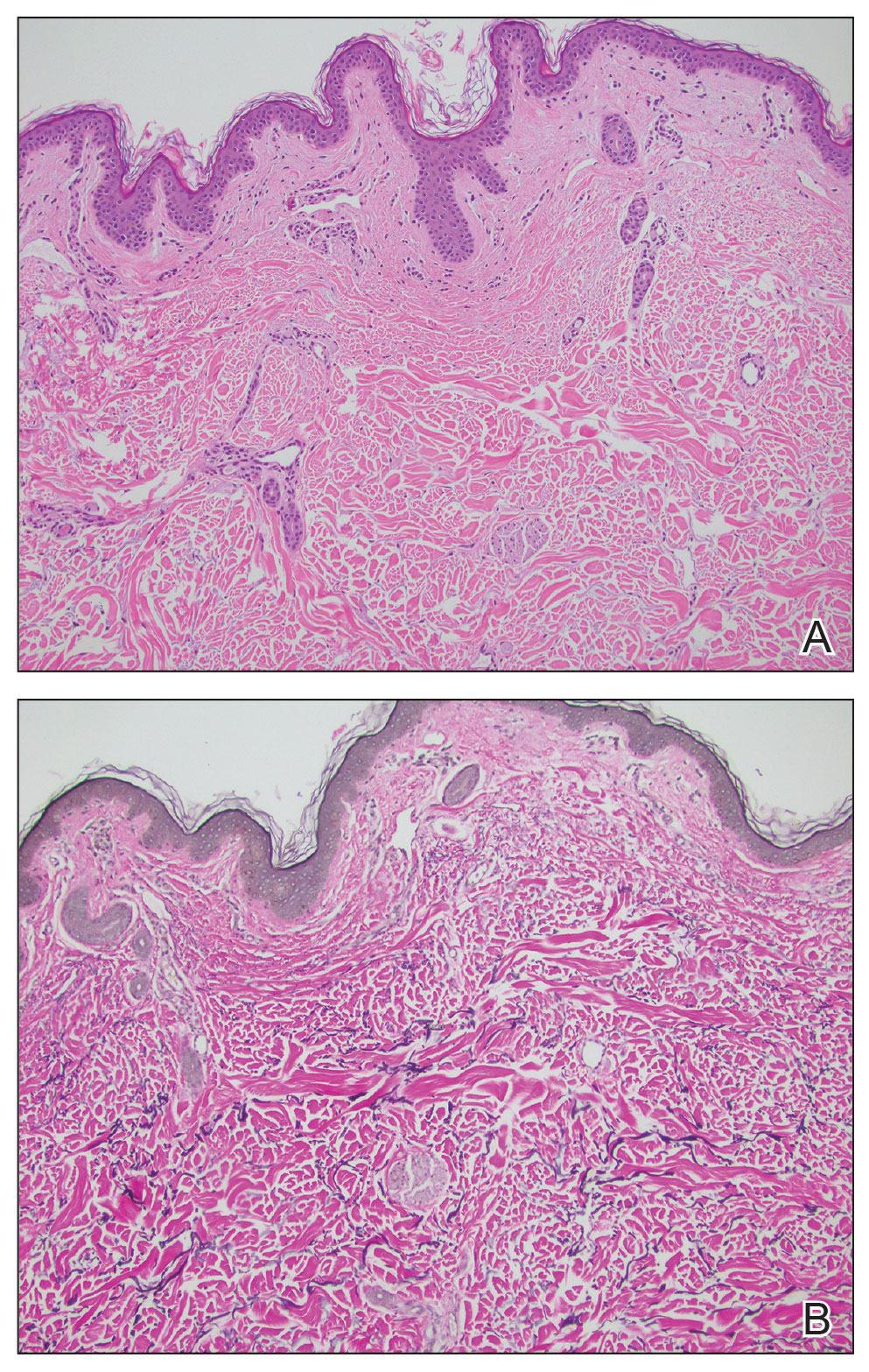

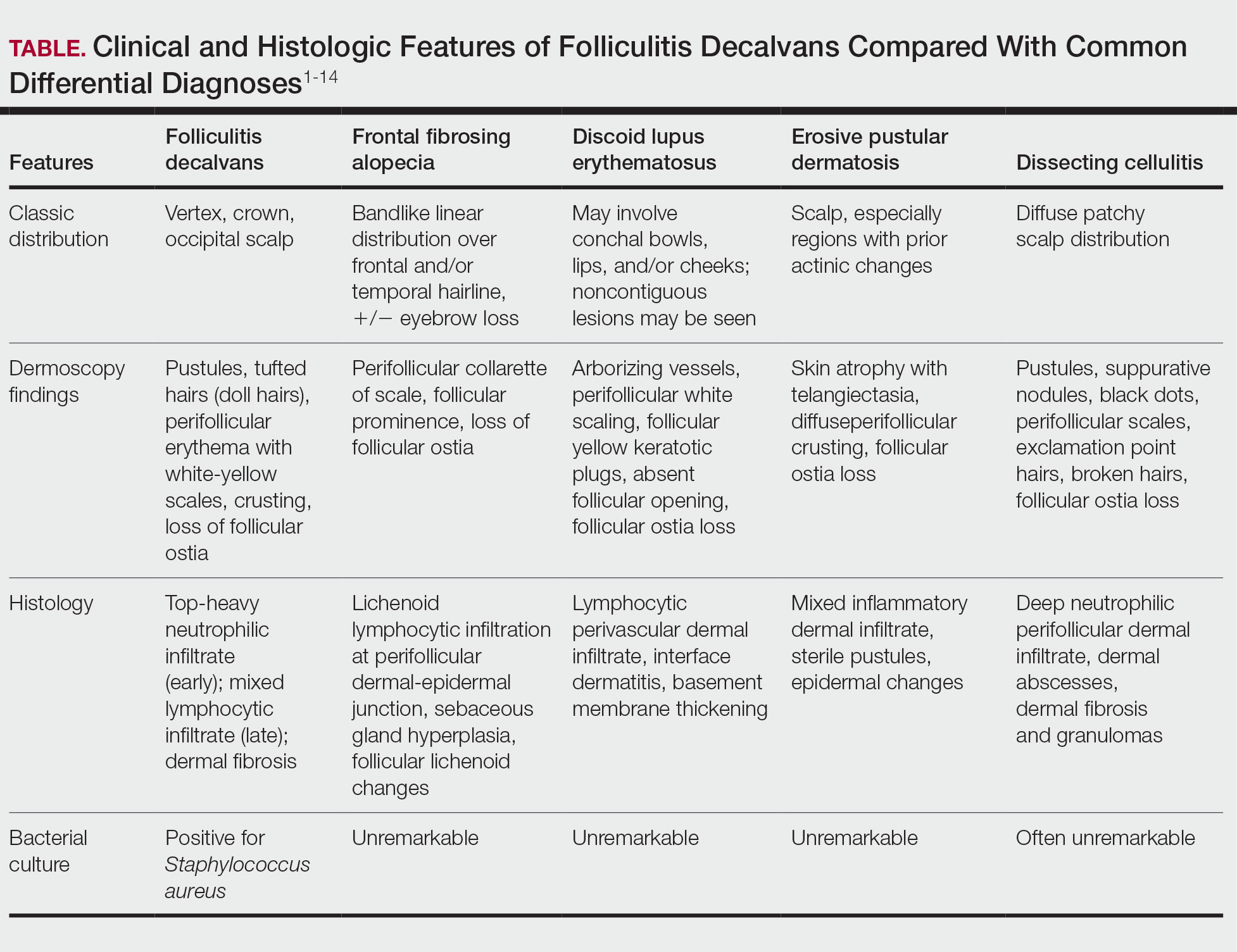

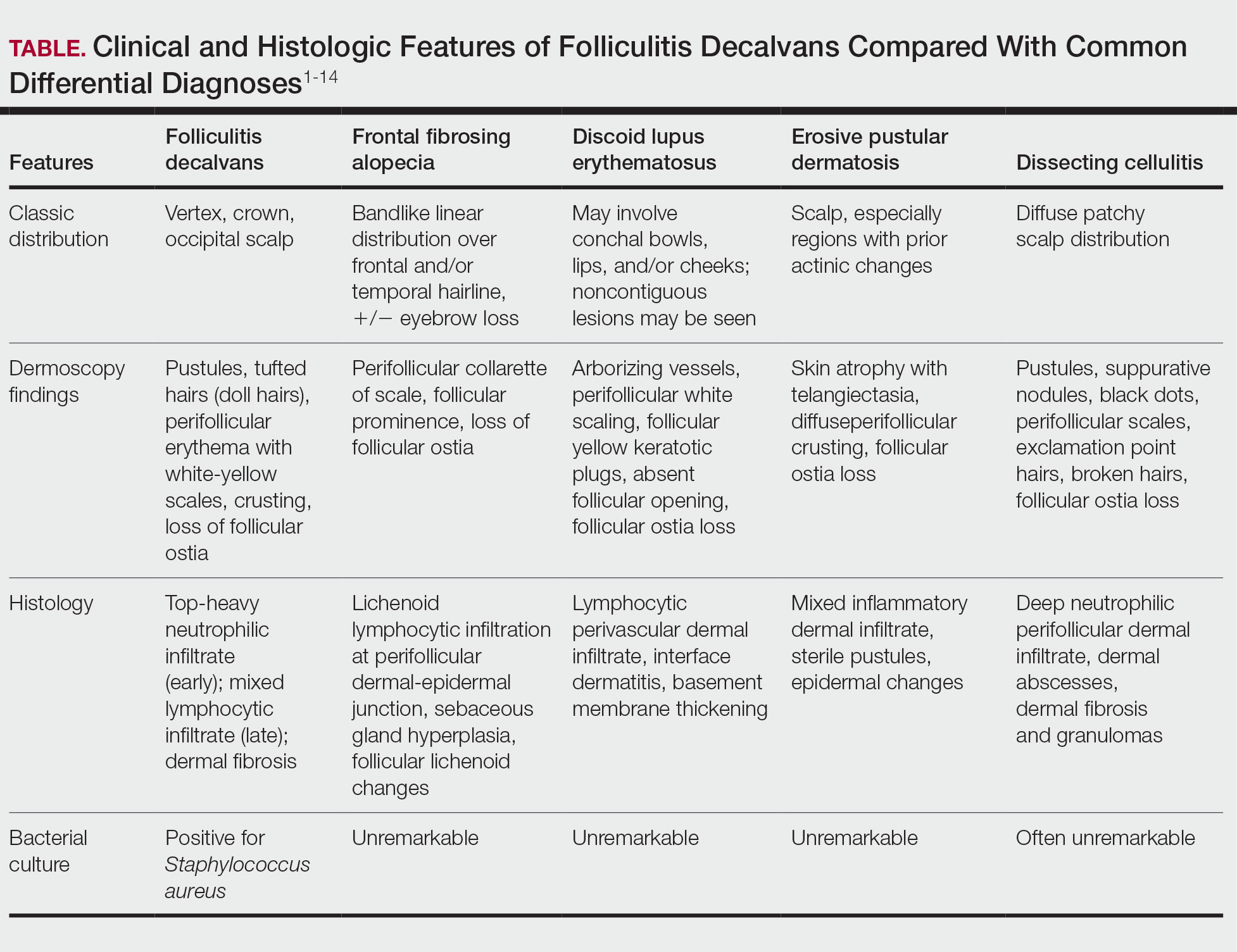

Histopathology demonstrated decreased density and fragmentation of elastic fibers in the superficial reticular and papillary dermis consistent with an elastolytic disease process (Figure). Of note, elastolysis typically is visualized with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain but cannot be visualized well with standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Additional staining with Congo red was negative for amyloid, and colloidal iron did not show any increase in dermal mucin, ruling out amyloidosis and scleromyxedema, respectively. Based on the histopathologic findings and the clinical history, a diagnosis of fibroelastolytic papulosis (FP) was made. Given the benign nature of the condition, the patient was prescribed a topical steroid (clobetasol 0.05%) for symptomatic relief.

Cutaneous conditions can arise from abnormalities in the elastin composition of connective tissue due to abnormal elastin formation or degradation (elastolysis).1 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is a distinct elastolytic disorder diagnosed histologically by a notable loss of elastic fibers localized to the papillary dermis.2 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is an acquired condition linked to exposure to UV radiation, abnormal elastogenesis, and hormonal factors that commonly involves the neck, supraclavicular area, and upper back.1-3 Predominantly affecting elderly women, FP is characterized by soft white papules that often coalesce into a cobblestonelike plaque.2 Because the condition rarely is seen in men, there is speculation that it may involve genetic, hereditary, and hormonal factors that have yet to be identified.1

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be classified as either pseudoxanthoma elasticum–like papillary dermal elastolysis or white fibrous papulosis.2,3 White fibrous papulosis manifests with haphazardly arranged collagen fibers in the reticular and deep dermis with papillary dermal elastolysis and most commonly develops on the neck.3 Although our patient’s lesion was on the neck, the absence of thickened collagen bands on histology supported classification as the pseudoxanthoma elasticum– like papillary dermal elastolysis subtype.

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be distinguished from other elastic abnormalities by its characteristic clinical appearance, demographic distribution, and associated histopathologic findings. The differential diagnosis of FP includes pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), anetoderma, scleromyxedema, and lichen amyloidosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a hereditary or acquired multisystem disease characterized by fragmentation and calcification of elastic fibers in the mid dermis.1,4 Its clinical presentation resembles that of FP, appearing as small, asymptomatic, yellowish or flesh-colored papules in a reticular pattern that progressively coalesce into larger plaques with a cobblestonelike appearance.1 Like FP, PXE commonly affects the flexural creases in women but in contrast may manifest earlier (ie, second or third decades of life). Additionally, the pathogenesis of PXE is not related to UV radiation exposure. The hereditary form develops due to a gene variation, whereas the acquired form may be due to conditions associated with physiologic and/or mechanical stress.1

Anetoderma, also known as macular atrophy, is another condition that demonstrates elastic tissue loss in the dermis on histopathology.1 Anetoderma commonly is seen in younger patients and can be differentiated from FP by the antecedent presence of an inflammatory process. Anetoderma is classified as primary or secondary. Primary anetoderma is associated with prothrombotic abnormalities, while secondary anetoderma is associated with systemic disease including but not limited to sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous, and Graves disease.1

Neither lichen myxedematosus (LM) nor lichen amyloidosis (LA) are true elastolytic conditions. Lichen myxedematosus is considered in the differential diagnosis of FP due to the associated loss of elastin observed with disease progression. An idiopathic cutaneous mucinosis, LM is a localized form of scleromyxedema, which is characterized by small, firm, waxy papules; mucin deposition in the skin; fibroblast proliferation; and fibrosis. On histologic analysis, typical findings of LM include irregularly arranged fibroblasts, diffuse mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, increased collagen deposition, and a decrease in elastin fibers.5

Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare condition characterized by the extracellular deposition of amyloid proteins in the skin and a lack of systemic involvement. Although it is not an elastolytic condition, LA is clinically similar to FP, often manifesting as multiple localized, pruritic, hyperpigmented papules that can coalesce into larger plaques; it tends to develop on the shins, calves, ankles, and thighs.6,7 The condition commonly manifests in the fifth and sixth decades of life; however, in contrast to FP, LA is more prevalent in men and individuals from Central and South American as well as Middle Eastern and non-Chinese Asian populations.8 Lichen amyloidosis is a keratin-derived amyloidosis with cytokeratin-based amyloid precursors that only deposit in the dermis.6 Histopathology reveals colloid bodies due to the presence of apoptotic basal keratinocytes. The etiology of LA is unknown, but on rare occasions it has been associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A rearranged during transfection mutations.6

In summary, FP is an uncommonly diagnosed elastolytic condition that often is asymptomatic or associated with mild pruritus. Biopsy is warranted to help differentiate it from mimicker conditions that may be associated with systemic disease. Currently, there is no established therapy that provides successful treatment. Research suggests unsatisfactory results with the use of topical tretinoin or topical antioxidants.3 More recently, nonablative fractional resurfacing lasers have been evaluated as a possible therapeutic strategy of promise for elastic disorders.9

- Andrés-Ramos I, Alegría-Landa V, Gimeno I, et al. Cutaneous elastic tissue anomalies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:85-117. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001275

- Valbuena V, Assaad D, Yeung J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis: a single case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:345-347. doi:10.1177/1203475417699407

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635. doi:10.7759/cureus.7635

- Recio-Monescillo M, Torre-Castro J, Manzanas C, et al. Papillary dermal elastolysis histopathology mimicking folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:430-433. doi:10.1111/cup.14402

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.011

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0278-9

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. Lichen amyloidosis. CMAJ. 2014;186:532. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130698

- Chen JF, Chen YF. Answer: can you identify this condition? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:1234-1235.

- Foering K, Torbeck RL, Frank MP, et al. Treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis with nonablative fractional resurfacing laser resulting in clinical and histologic improvement in elastin and collagen. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:382-384. doi:10.1080/14764172.2017.1358457

The Diagnosis: Fibroelastolytic Papulosis

Histopathology demonstrated decreased density and fragmentation of elastic fibers in the superficial reticular and papillary dermis consistent with an elastolytic disease process (Figure). Of note, elastolysis typically is visualized with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain but cannot be visualized well with standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Additional staining with Congo red was negative for amyloid, and colloidal iron did not show any increase in dermal mucin, ruling out amyloidosis and scleromyxedema, respectively. Based on the histopathologic findings and the clinical history, a diagnosis of fibroelastolytic papulosis (FP) was made. Given the benign nature of the condition, the patient was prescribed a topical steroid (clobetasol 0.05%) for symptomatic relief.

Cutaneous conditions can arise from abnormalities in the elastin composition of connective tissue due to abnormal elastin formation or degradation (elastolysis).1 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is a distinct elastolytic disorder diagnosed histologically by a notable loss of elastic fibers localized to the papillary dermis.2 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is an acquired condition linked to exposure to UV radiation, abnormal elastogenesis, and hormonal factors that commonly involves the neck, supraclavicular area, and upper back.1-3 Predominantly affecting elderly women, FP is characterized by soft white papules that often coalesce into a cobblestonelike plaque.2 Because the condition rarely is seen in men, there is speculation that it may involve genetic, hereditary, and hormonal factors that have yet to be identified.1

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be classified as either pseudoxanthoma elasticum–like papillary dermal elastolysis or white fibrous papulosis.2,3 White fibrous papulosis manifests with haphazardly arranged collagen fibers in the reticular and deep dermis with papillary dermal elastolysis and most commonly develops on the neck.3 Although our patient’s lesion was on the neck, the absence of thickened collagen bands on histology supported classification as the pseudoxanthoma elasticum– like papillary dermal elastolysis subtype.

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be distinguished from other elastic abnormalities by its characteristic clinical appearance, demographic distribution, and associated histopathologic findings. The differential diagnosis of FP includes pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), anetoderma, scleromyxedema, and lichen amyloidosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a hereditary or acquired multisystem disease characterized by fragmentation and calcification of elastic fibers in the mid dermis.1,4 Its clinical presentation resembles that of FP, appearing as small, asymptomatic, yellowish or flesh-colored papules in a reticular pattern that progressively coalesce into larger plaques with a cobblestonelike appearance.1 Like FP, PXE commonly affects the flexural creases in women but in contrast may manifest earlier (ie, second or third decades of life). Additionally, the pathogenesis of PXE is not related to UV radiation exposure. The hereditary form develops due to a gene variation, whereas the acquired form may be due to conditions associated with physiologic and/or mechanical stress.1

Anetoderma, also known as macular atrophy, is another condition that demonstrates elastic tissue loss in the dermis on histopathology.1 Anetoderma commonly is seen in younger patients and can be differentiated from FP by the antecedent presence of an inflammatory process. Anetoderma is classified as primary or secondary. Primary anetoderma is associated with prothrombotic abnormalities, while secondary anetoderma is associated with systemic disease including but not limited to sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous, and Graves disease.1

Neither lichen myxedematosus (LM) nor lichen amyloidosis (LA) are true elastolytic conditions. Lichen myxedematosus is considered in the differential diagnosis of FP due to the associated loss of elastin observed with disease progression. An idiopathic cutaneous mucinosis, LM is a localized form of scleromyxedema, which is characterized by small, firm, waxy papules; mucin deposition in the skin; fibroblast proliferation; and fibrosis. On histologic analysis, typical findings of LM include irregularly arranged fibroblasts, diffuse mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, increased collagen deposition, and a decrease in elastin fibers.5

Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare condition characterized by the extracellular deposition of amyloid proteins in the skin and a lack of systemic involvement. Although it is not an elastolytic condition, LA is clinically similar to FP, often manifesting as multiple localized, pruritic, hyperpigmented papules that can coalesce into larger plaques; it tends to develop on the shins, calves, ankles, and thighs.6,7 The condition commonly manifests in the fifth and sixth decades of life; however, in contrast to FP, LA is more prevalent in men and individuals from Central and South American as well as Middle Eastern and non-Chinese Asian populations.8 Lichen amyloidosis is a keratin-derived amyloidosis with cytokeratin-based amyloid precursors that only deposit in the dermis.6 Histopathology reveals colloid bodies due to the presence of apoptotic basal keratinocytes. The etiology of LA is unknown, but on rare occasions it has been associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A rearranged during transfection mutations.6

In summary, FP is an uncommonly diagnosed elastolytic condition that often is asymptomatic or associated with mild pruritus. Biopsy is warranted to help differentiate it from mimicker conditions that may be associated with systemic disease. Currently, there is no established therapy that provides successful treatment. Research suggests unsatisfactory results with the use of topical tretinoin or topical antioxidants.3 More recently, nonablative fractional resurfacing lasers have been evaluated as a possible therapeutic strategy of promise for elastic disorders.9

The Diagnosis: Fibroelastolytic Papulosis

Histopathology demonstrated decreased density and fragmentation of elastic fibers in the superficial reticular and papillary dermis consistent with an elastolytic disease process (Figure). Of note, elastolysis typically is visualized with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain but cannot be visualized well with standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Additional staining with Congo red was negative for amyloid, and colloidal iron did not show any increase in dermal mucin, ruling out amyloidosis and scleromyxedema, respectively. Based on the histopathologic findings and the clinical history, a diagnosis of fibroelastolytic papulosis (FP) was made. Given the benign nature of the condition, the patient was prescribed a topical steroid (clobetasol 0.05%) for symptomatic relief.

Cutaneous conditions can arise from abnormalities in the elastin composition of connective tissue due to abnormal elastin formation or degradation (elastolysis).1 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is a distinct elastolytic disorder diagnosed histologically by a notable loss of elastic fibers localized to the papillary dermis.2 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is an acquired condition linked to exposure to UV radiation, abnormal elastogenesis, and hormonal factors that commonly involves the neck, supraclavicular area, and upper back.1-3 Predominantly affecting elderly women, FP is characterized by soft white papules that often coalesce into a cobblestonelike plaque.2 Because the condition rarely is seen in men, there is speculation that it may involve genetic, hereditary, and hormonal factors that have yet to be identified.1

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be classified as either pseudoxanthoma elasticum–like papillary dermal elastolysis or white fibrous papulosis.2,3 White fibrous papulosis manifests with haphazardly arranged collagen fibers in the reticular and deep dermis with papillary dermal elastolysis and most commonly develops on the neck.3 Although our patient’s lesion was on the neck, the absence of thickened collagen bands on histology supported classification as the pseudoxanthoma elasticum– like papillary dermal elastolysis subtype.

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be distinguished from other elastic abnormalities by its characteristic clinical appearance, demographic distribution, and associated histopathologic findings. The differential diagnosis of FP includes pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), anetoderma, scleromyxedema, and lichen amyloidosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a hereditary or acquired multisystem disease characterized by fragmentation and calcification of elastic fibers in the mid dermis.1,4 Its clinical presentation resembles that of FP, appearing as small, asymptomatic, yellowish or flesh-colored papules in a reticular pattern that progressively coalesce into larger plaques with a cobblestonelike appearance.1 Like FP, PXE commonly affects the flexural creases in women but in contrast may manifest earlier (ie, second or third decades of life). Additionally, the pathogenesis of PXE is not related to UV radiation exposure. The hereditary form develops due to a gene variation, whereas the acquired form may be due to conditions associated with physiologic and/or mechanical stress.1

Anetoderma, also known as macular atrophy, is another condition that demonstrates elastic tissue loss in the dermis on histopathology.1 Anetoderma commonly is seen in younger patients and can be differentiated from FP by the antecedent presence of an inflammatory process. Anetoderma is classified as primary or secondary. Primary anetoderma is associated with prothrombotic abnormalities, while secondary anetoderma is associated with systemic disease including but not limited to sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous, and Graves disease.1

Neither lichen myxedematosus (LM) nor lichen amyloidosis (LA) are true elastolytic conditions. Lichen myxedematosus is considered in the differential diagnosis of FP due to the associated loss of elastin observed with disease progression. An idiopathic cutaneous mucinosis, LM is a localized form of scleromyxedema, which is characterized by small, firm, waxy papules; mucin deposition in the skin; fibroblast proliferation; and fibrosis. On histologic analysis, typical findings of LM include irregularly arranged fibroblasts, diffuse mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, increased collagen deposition, and a decrease in elastin fibers.5

Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare condition characterized by the extracellular deposition of amyloid proteins in the skin and a lack of systemic involvement. Although it is not an elastolytic condition, LA is clinically similar to FP, often manifesting as multiple localized, pruritic, hyperpigmented papules that can coalesce into larger plaques; it tends to develop on the shins, calves, ankles, and thighs.6,7 The condition commonly manifests in the fifth and sixth decades of life; however, in contrast to FP, LA is more prevalent in men and individuals from Central and South American as well as Middle Eastern and non-Chinese Asian populations.8 Lichen amyloidosis is a keratin-derived amyloidosis with cytokeratin-based amyloid precursors that only deposit in the dermis.6 Histopathology reveals colloid bodies due to the presence of apoptotic basal keratinocytes. The etiology of LA is unknown, but on rare occasions it has been associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A rearranged during transfection mutations.6

In summary, FP is an uncommonly diagnosed elastolytic condition that often is asymptomatic or associated with mild pruritus. Biopsy is warranted to help differentiate it from mimicker conditions that may be associated with systemic disease. Currently, there is no established therapy that provides successful treatment. Research suggests unsatisfactory results with the use of topical tretinoin or topical antioxidants.3 More recently, nonablative fractional resurfacing lasers have been evaluated as a possible therapeutic strategy of promise for elastic disorders.9

- Andrés-Ramos I, Alegría-Landa V, Gimeno I, et al. Cutaneous elastic tissue anomalies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:85-117. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001275

- Valbuena V, Assaad D, Yeung J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis: a single case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:345-347. doi:10.1177/1203475417699407

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635. doi:10.7759/cureus.7635

- Recio-Monescillo M, Torre-Castro J, Manzanas C, et al. Papillary dermal elastolysis histopathology mimicking folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:430-433. doi:10.1111/cup.14402

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.011

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0278-9

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. Lichen amyloidosis. CMAJ. 2014;186:532. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130698

- Chen JF, Chen YF. Answer: can you identify this condition? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:1234-1235.

- Foering K, Torbeck RL, Frank MP, et al. Treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis with nonablative fractional resurfacing laser resulting in clinical and histologic improvement in elastin and collagen. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:382-384. doi:10.1080/14764172.2017.1358457

- Andrés-Ramos I, Alegría-Landa V, Gimeno I, et al. Cutaneous elastic tissue anomalies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:85-117. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001275

- Valbuena V, Assaad D, Yeung J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis: a single case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:345-347. doi:10.1177/1203475417699407

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635. doi:10.7759/cureus.7635

- Recio-Monescillo M, Torre-Castro J, Manzanas C, et al. Papillary dermal elastolysis histopathology mimicking folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:430-433. doi:10.1111/cup.14402

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.011

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0278-9

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. Lichen amyloidosis. CMAJ. 2014;186:532. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130698

- Chen JF, Chen YF. Answer: can you identify this condition? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:1234-1235.

- Foering K, Torbeck RL, Frank MP, et al. Treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis with nonablative fractional resurfacing laser resulting in clinical and histologic improvement in elastin and collagen. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:382-384. doi:10.1080/14764172.2017.1358457

A 76-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a pruritic rash on the posterior lateral neck of several years’ duration. The rash had been slowly worsening and was intermittently symptomatic. Physical examination revealed monomorphous flesh-colored papules coalescing on the neck, yielding a cobblestonelike texture. The patient had been treated previously by dermatology with topical steroids, but symptoms persisted. A punch biopsy of the left lateral neck was performed.

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Discussion

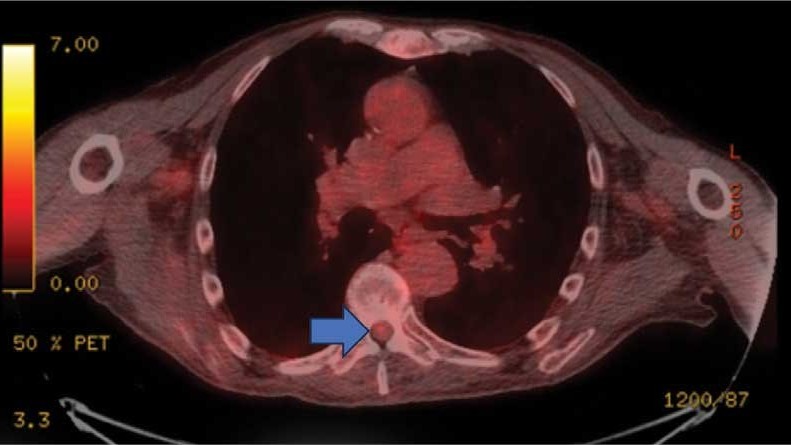

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

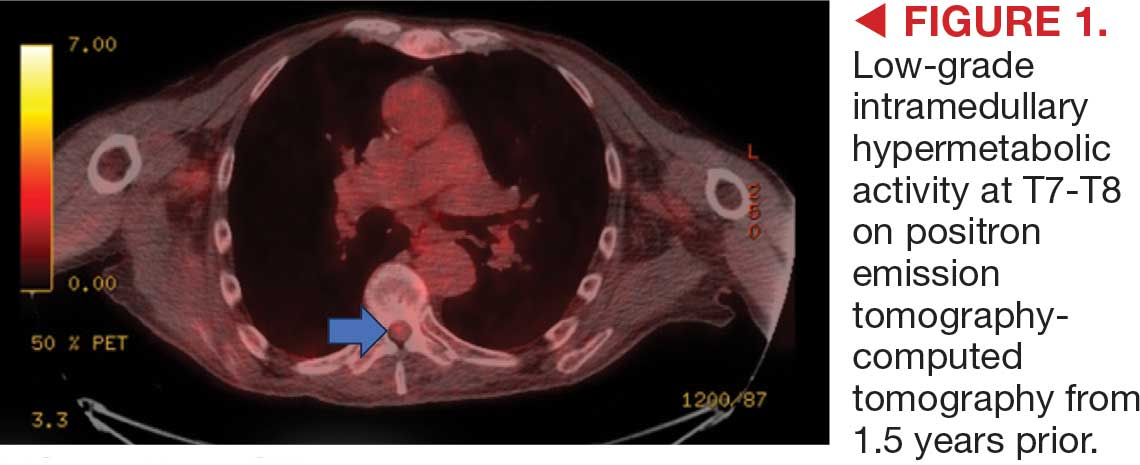

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

Discussion