User login

Healthcare AI: Balancing Safety and Innovation

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications are expanding rapidly in healthcare. AI powered tools are increasingly used in everyday medical practice, assisting clinicians with tasks such as diagnosis, treatment planning, data analysis, and patient monitoring, effectively integrating AI into routine clinical decision making. Despite its potential to fundamentally transform the practice of medicine and healthcare delivery, AI in healthcare remains largely unregulated, with a lack of common standards to guide responsible design, development, and adoption of AI-based tools to guide clinical care.

But this is changing. In mid-January, the US Department of Health & Human Services released its Strategic Plan for the Use of AI in Health, Human Services, and Public Health (available at www.healthit.gov), presenting an approach to catalyze innovation, promote trustworthy AI development, democratize technologies and resources, and cultivate AI-empowered workforces and organizational cultures. While there is no immediate regulatory impact, the plan does provide important insights into how the federal government thinks about AI, which will be a part of driving regulations in the future. As crucial stakeholders in the health AI universe and advocates for its responsible use in clinical practice, it is critical that we as clinicians keep abreast of developments in this rapidly evolving space.

In this month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News, we summarize a recent systematic review and meta-analysis highlighting worsening health disparities for Hispanic adults with MASLD. We also report the results of an industry-sponsored study comparing the real-world clinical effectiveness of GI Genius (an AI-driven tool) with that of standard colonoscopy.

In February’s Member Spotlight, we introduce you to international AGA member Dr. Tossapol Kerdsirichairat (clinical associate professor of gastroenterology at Bumrungrad International Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand), who shares his insights regarding the challenges and rewards of practicing gastroenterology at one of the largest private hospitals in Southeast Asia. ‘Tos’ is one of roughly 25% of AGA members who live and work outside the United States.

Finally, this month’s In Focus column from The New Gastroenterologist focuses on management of chronic constipation, a highly prevalent condition that significantly impacts the quality of life of many of our patients. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our February issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications are expanding rapidly in healthcare. AI powered tools are increasingly used in everyday medical practice, assisting clinicians with tasks such as diagnosis, treatment planning, data analysis, and patient monitoring, effectively integrating AI into routine clinical decision making. Despite its potential to fundamentally transform the practice of medicine and healthcare delivery, AI in healthcare remains largely unregulated, with a lack of common standards to guide responsible design, development, and adoption of AI-based tools to guide clinical care.

But this is changing. In mid-January, the US Department of Health & Human Services released its Strategic Plan for the Use of AI in Health, Human Services, and Public Health (available at www.healthit.gov), presenting an approach to catalyze innovation, promote trustworthy AI development, democratize technologies and resources, and cultivate AI-empowered workforces and organizational cultures. While there is no immediate regulatory impact, the plan does provide important insights into how the federal government thinks about AI, which will be a part of driving regulations in the future. As crucial stakeholders in the health AI universe and advocates for its responsible use in clinical practice, it is critical that we as clinicians keep abreast of developments in this rapidly evolving space.

In this month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News, we summarize a recent systematic review and meta-analysis highlighting worsening health disparities for Hispanic adults with MASLD. We also report the results of an industry-sponsored study comparing the real-world clinical effectiveness of GI Genius (an AI-driven tool) with that of standard colonoscopy.

In February’s Member Spotlight, we introduce you to international AGA member Dr. Tossapol Kerdsirichairat (clinical associate professor of gastroenterology at Bumrungrad International Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand), who shares his insights regarding the challenges and rewards of practicing gastroenterology at one of the largest private hospitals in Southeast Asia. ‘Tos’ is one of roughly 25% of AGA members who live and work outside the United States.

Finally, this month’s In Focus column from The New Gastroenterologist focuses on management of chronic constipation, a highly prevalent condition that significantly impacts the quality of life of many of our patients. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our February issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications are expanding rapidly in healthcare. AI powered tools are increasingly used in everyday medical practice, assisting clinicians with tasks such as diagnosis, treatment planning, data analysis, and patient monitoring, effectively integrating AI into routine clinical decision making. Despite its potential to fundamentally transform the practice of medicine and healthcare delivery, AI in healthcare remains largely unregulated, with a lack of common standards to guide responsible design, development, and adoption of AI-based tools to guide clinical care.

But this is changing. In mid-January, the US Department of Health & Human Services released its Strategic Plan for the Use of AI in Health, Human Services, and Public Health (available at www.healthit.gov), presenting an approach to catalyze innovation, promote trustworthy AI development, democratize technologies and resources, and cultivate AI-empowered workforces and organizational cultures. While there is no immediate regulatory impact, the plan does provide important insights into how the federal government thinks about AI, which will be a part of driving regulations in the future. As crucial stakeholders in the health AI universe and advocates for its responsible use in clinical practice, it is critical that we as clinicians keep abreast of developments in this rapidly evolving space.

In this month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News, we summarize a recent systematic review and meta-analysis highlighting worsening health disparities for Hispanic adults with MASLD. We also report the results of an industry-sponsored study comparing the real-world clinical effectiveness of GI Genius (an AI-driven tool) with that of standard colonoscopy.

In February’s Member Spotlight, we introduce you to international AGA member Dr. Tossapol Kerdsirichairat (clinical associate professor of gastroenterology at Bumrungrad International Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand), who shares his insights regarding the challenges and rewards of practicing gastroenterology at one of the largest private hospitals in Southeast Asia. ‘Tos’ is one of roughly 25% of AGA members who live and work outside the United States.

Finally, this month’s In Focus column from The New Gastroenterologist focuses on management of chronic constipation, a highly prevalent condition that significantly impacts the quality of life of many of our patients. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our February issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Atopic Dermatitis and Sleep Disturbances

Recently one of my keep-up-to-date apps alerted me to a study in Pediatric Dermatology on sleep and atopic dermatitis. When I chased down the abstract it was a shoulder-shrugging-so-what encounter. The authors reported that having a child with atopic dermatitis decreased the odds of a parent getting 7 hours of sleep a night and increased the odds that the parent was also taking sleep-aiding medications. The authors felt their data was meaningful enough to publish based on the size and the cross-sectional nature of their sample. However, anyone who has worked with families with atopic dermatitis shouldn’t be surprised at their findings.

Curious about what other investigators had discovered about the anecdotally obvious relationship between sleep and atopic dermatitis, I dug until I found a rather thorough discussion of the literature published in The Journal of Clinical Immunology Practice. These authors from the University of Rochester Medical School in New York begin by pointing out that, although 47%-80% of children with atopic dermatitis and 33%-90% of adults with atopic dermatitis have disturbed sleep, “literature on this topic remains sparse with most studies evaluating sleep as a secondary outcome using subjective measures.” They further note that sleep is one of the three most problematic symptoms for children with atopic dermatitis and their families.

Characterizing the Sleep Loss

Difficulty falling asleep, frequent and long waking, and excessive daytime sleepiness are the most common symptoms reported. In the few sleep laboratory studies that have been done there has been no significant decrease in sleep duration, which is a bit of a surprise. However, as expected, sleep-onset latency, more wake time after sleep onset, sleep fragmentation, and decreased sleep efficiency have been observed in the atopic dermatitis patients. In other studies of younger children, female gender and lower socioeconomic status seem to be associated with poor sleep quality.

Most studies found that in general the prevalence and severity of sleep disturbances increases with the severity of the disease. As the disease flares, increased bedtime resistance, nocturnal wakings and daytime sleepiness become more likely. These parentally reported associations have also been confirmed by sleep laboratory observations.

The sleep disturbances quickly become a family affair with 60% of siblings and parents reporting disturbed sleep. When the child with atopic dermatitis is having a flareup, nearly 90% of their parents report losing up to 2.5 hours of sleep. Not surprisingly sleep disturbances have been associated with behavioral and emotional problems including decreased happiness, poor cognitive performance, hyperactivity, and inattention. Mothers seem to bear the brunt of the problem and interpersonal conflicts and exhaustion are unfortunately not uncommon.

Probing the Causes

So why are atopic dermatitis patients and their families so prone to the ill effects of disturbed sleep? Although you might think it should be obvious, this review of the “sparse” literature doesn’t provide a satisfying answer. However, the authors provide three possible explanations.

The one with the least supporting evidence is circadian variations in the products of inflammation such as cytokines and their effect on melatonin production. The explanation which I think most of us have already considered is that pruritus disrupts sleep. This is the often-quoted itch-scratch feedback cycle which can release inflammatory mediators (“pruritogens”). However, the investigators have found that many studies report “conflicting results or only weak correlations.”

The third alternative posed by the authors is by far the most appealing and hinges on the assumption that, as with many other chronic conditions, atopic dermatitis renders the patient vulnerable to insomnia. “Nocturnal scratching disrupts sleep and sets the stage for cognitive and behavioral factors that reinforce insomnia as a conditioned response.” In other words, even after the “co-concurring condition” resolves insomnia related sleep behaviors continue. The investigators point to a study supporting this explanation which found that, even after a child’s skin cleared, his/her sleep arousals failed to return to normal suggesting that learned behavior patterns might be playing a role.

It may be a stretch to suggest that poor sleep hygiene might in and of itself cause atopic dermatitis, but it can’t be ruled out. At a minimum the current research suggests that there is a bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbances and atopic dermatitis.

Next Steps

The authors of this study urge that we be more creative in using already-existing portable and relatively low-cost sleep monitoring technology to better define this relationship. While that is a worthwhile avenue for research, I think we who see children (both primary care providers and dermatologists) now have enough evidence to move managing the sleep hygiene of our atopic dermatitis patients to the front burner, along with moisturizers and topical medications, without needing to do costly and time-consuming studies.

This means taking a thorough sleep history. If, in the rare cases where the child’s sleep habits are normal, the parents should be warned that falling off the sleep wagon is likely to exacerbate the child’s skin. If the history reveals an inefficient and dysfunctional bedtime routine or other symptoms of insomnia, advise the parents on how it can be improved. Then follow up at each visit if there has been no improvement. Sleep management can be time-consuming as well but it should be part of every primary care pediatrician’s toolbox. For the dermatologist who doesn’t feel comfortable managing sleep problems, a consultation with a pediatrician or a sleep specialist is in order.

The adult with atopic dermatitis is a somewhat different animal and a formal sleep study may be indicated. Cognitive-behavioral therapy might be helpful for adult population but the investigators could find no trials of its use in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Convincing the parents of an atopic dermatitis patient that their family’s disturbed sleep may not only be the result of his/her itchy skin but may be a preexisting compounding problem may not be an easy sell. I hope if you can be open to the strong possibility that disordered sleep is not just the effect but in some ways may be a likely contributor to your patients’ atopic dermatitis, you may become more effective in managing the disease.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Recently one of my keep-up-to-date apps alerted me to a study in Pediatric Dermatology on sleep and atopic dermatitis. When I chased down the abstract it was a shoulder-shrugging-so-what encounter. The authors reported that having a child with atopic dermatitis decreased the odds of a parent getting 7 hours of sleep a night and increased the odds that the parent was also taking sleep-aiding medications. The authors felt their data was meaningful enough to publish based on the size and the cross-sectional nature of their sample. However, anyone who has worked with families with atopic dermatitis shouldn’t be surprised at their findings.

Curious about what other investigators had discovered about the anecdotally obvious relationship between sleep and atopic dermatitis, I dug until I found a rather thorough discussion of the literature published in The Journal of Clinical Immunology Practice. These authors from the University of Rochester Medical School in New York begin by pointing out that, although 47%-80% of children with atopic dermatitis and 33%-90% of adults with atopic dermatitis have disturbed sleep, “literature on this topic remains sparse with most studies evaluating sleep as a secondary outcome using subjective measures.” They further note that sleep is one of the three most problematic symptoms for children with atopic dermatitis and their families.

Characterizing the Sleep Loss

Difficulty falling asleep, frequent and long waking, and excessive daytime sleepiness are the most common symptoms reported. In the few sleep laboratory studies that have been done there has been no significant decrease in sleep duration, which is a bit of a surprise. However, as expected, sleep-onset latency, more wake time after sleep onset, sleep fragmentation, and decreased sleep efficiency have been observed in the atopic dermatitis patients. In other studies of younger children, female gender and lower socioeconomic status seem to be associated with poor sleep quality.

Most studies found that in general the prevalence and severity of sleep disturbances increases with the severity of the disease. As the disease flares, increased bedtime resistance, nocturnal wakings and daytime sleepiness become more likely. These parentally reported associations have also been confirmed by sleep laboratory observations.

The sleep disturbances quickly become a family affair with 60% of siblings and parents reporting disturbed sleep. When the child with atopic dermatitis is having a flareup, nearly 90% of their parents report losing up to 2.5 hours of sleep. Not surprisingly sleep disturbances have been associated with behavioral and emotional problems including decreased happiness, poor cognitive performance, hyperactivity, and inattention. Mothers seem to bear the brunt of the problem and interpersonal conflicts and exhaustion are unfortunately not uncommon.

Probing the Causes

So why are atopic dermatitis patients and their families so prone to the ill effects of disturbed sleep? Although you might think it should be obvious, this review of the “sparse” literature doesn’t provide a satisfying answer. However, the authors provide three possible explanations.

The one with the least supporting evidence is circadian variations in the products of inflammation such as cytokines and their effect on melatonin production. The explanation which I think most of us have already considered is that pruritus disrupts sleep. This is the often-quoted itch-scratch feedback cycle which can release inflammatory mediators (“pruritogens”). However, the investigators have found that many studies report “conflicting results or only weak correlations.”

The third alternative posed by the authors is by far the most appealing and hinges on the assumption that, as with many other chronic conditions, atopic dermatitis renders the patient vulnerable to insomnia. “Nocturnal scratching disrupts sleep and sets the stage for cognitive and behavioral factors that reinforce insomnia as a conditioned response.” In other words, even after the “co-concurring condition” resolves insomnia related sleep behaviors continue. The investigators point to a study supporting this explanation which found that, even after a child’s skin cleared, his/her sleep arousals failed to return to normal suggesting that learned behavior patterns might be playing a role.

It may be a stretch to suggest that poor sleep hygiene might in and of itself cause atopic dermatitis, but it can’t be ruled out. At a minimum the current research suggests that there is a bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbances and atopic dermatitis.

Next Steps

The authors of this study urge that we be more creative in using already-existing portable and relatively low-cost sleep monitoring technology to better define this relationship. While that is a worthwhile avenue for research, I think we who see children (both primary care providers and dermatologists) now have enough evidence to move managing the sleep hygiene of our atopic dermatitis patients to the front burner, along with moisturizers and topical medications, without needing to do costly and time-consuming studies.

This means taking a thorough sleep history. If, in the rare cases where the child’s sleep habits are normal, the parents should be warned that falling off the sleep wagon is likely to exacerbate the child’s skin. If the history reveals an inefficient and dysfunctional bedtime routine or other symptoms of insomnia, advise the parents on how it can be improved. Then follow up at each visit if there has been no improvement. Sleep management can be time-consuming as well but it should be part of every primary care pediatrician’s toolbox. For the dermatologist who doesn’t feel comfortable managing sleep problems, a consultation with a pediatrician or a sleep specialist is in order.

The adult with atopic dermatitis is a somewhat different animal and a formal sleep study may be indicated. Cognitive-behavioral therapy might be helpful for adult population but the investigators could find no trials of its use in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Convincing the parents of an atopic dermatitis patient that their family’s disturbed sleep may not only be the result of his/her itchy skin but may be a preexisting compounding problem may not be an easy sell. I hope if you can be open to the strong possibility that disordered sleep is not just the effect but in some ways may be a likely contributor to your patients’ atopic dermatitis, you may become more effective in managing the disease.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Recently one of my keep-up-to-date apps alerted me to a study in Pediatric Dermatology on sleep and atopic dermatitis. When I chased down the abstract it was a shoulder-shrugging-so-what encounter. The authors reported that having a child with atopic dermatitis decreased the odds of a parent getting 7 hours of sleep a night and increased the odds that the parent was also taking sleep-aiding medications. The authors felt their data was meaningful enough to publish based on the size and the cross-sectional nature of their sample. However, anyone who has worked with families with atopic dermatitis shouldn’t be surprised at their findings.

Curious about what other investigators had discovered about the anecdotally obvious relationship between sleep and atopic dermatitis, I dug until I found a rather thorough discussion of the literature published in The Journal of Clinical Immunology Practice. These authors from the University of Rochester Medical School in New York begin by pointing out that, although 47%-80% of children with atopic dermatitis and 33%-90% of adults with atopic dermatitis have disturbed sleep, “literature on this topic remains sparse with most studies evaluating sleep as a secondary outcome using subjective measures.” They further note that sleep is one of the three most problematic symptoms for children with atopic dermatitis and their families.

Characterizing the Sleep Loss

Difficulty falling asleep, frequent and long waking, and excessive daytime sleepiness are the most common symptoms reported. In the few sleep laboratory studies that have been done there has been no significant decrease in sleep duration, which is a bit of a surprise. However, as expected, sleep-onset latency, more wake time after sleep onset, sleep fragmentation, and decreased sleep efficiency have been observed in the atopic dermatitis patients. In other studies of younger children, female gender and lower socioeconomic status seem to be associated with poor sleep quality.

Most studies found that in general the prevalence and severity of sleep disturbances increases with the severity of the disease. As the disease flares, increased bedtime resistance, nocturnal wakings and daytime sleepiness become more likely. These parentally reported associations have also been confirmed by sleep laboratory observations.

The sleep disturbances quickly become a family affair with 60% of siblings and parents reporting disturbed sleep. When the child with atopic dermatitis is having a flareup, nearly 90% of their parents report losing up to 2.5 hours of sleep. Not surprisingly sleep disturbances have been associated with behavioral and emotional problems including decreased happiness, poor cognitive performance, hyperactivity, and inattention. Mothers seem to bear the brunt of the problem and interpersonal conflicts and exhaustion are unfortunately not uncommon.

Probing the Causes

So why are atopic dermatitis patients and their families so prone to the ill effects of disturbed sleep? Although you might think it should be obvious, this review of the “sparse” literature doesn’t provide a satisfying answer. However, the authors provide three possible explanations.

The one with the least supporting evidence is circadian variations in the products of inflammation such as cytokines and their effect on melatonin production. The explanation which I think most of us have already considered is that pruritus disrupts sleep. This is the often-quoted itch-scratch feedback cycle which can release inflammatory mediators (“pruritogens”). However, the investigators have found that many studies report “conflicting results or only weak correlations.”

The third alternative posed by the authors is by far the most appealing and hinges on the assumption that, as with many other chronic conditions, atopic dermatitis renders the patient vulnerable to insomnia. “Nocturnal scratching disrupts sleep and sets the stage for cognitive and behavioral factors that reinforce insomnia as a conditioned response.” In other words, even after the “co-concurring condition” resolves insomnia related sleep behaviors continue. The investigators point to a study supporting this explanation which found that, even after a child’s skin cleared, his/her sleep arousals failed to return to normal suggesting that learned behavior patterns might be playing a role.

It may be a stretch to suggest that poor sleep hygiene might in and of itself cause atopic dermatitis, but it can’t be ruled out. At a minimum the current research suggests that there is a bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbances and atopic dermatitis.

Next Steps

The authors of this study urge that we be more creative in using already-existing portable and relatively low-cost sleep monitoring technology to better define this relationship. While that is a worthwhile avenue for research, I think we who see children (both primary care providers and dermatologists) now have enough evidence to move managing the sleep hygiene of our atopic dermatitis patients to the front burner, along with moisturizers and topical medications, without needing to do costly and time-consuming studies.

This means taking a thorough sleep history. If, in the rare cases where the child’s sleep habits are normal, the parents should be warned that falling off the sleep wagon is likely to exacerbate the child’s skin. If the history reveals an inefficient and dysfunctional bedtime routine or other symptoms of insomnia, advise the parents on how it can be improved. Then follow up at each visit if there has been no improvement. Sleep management can be time-consuming as well but it should be part of every primary care pediatrician’s toolbox. For the dermatologist who doesn’t feel comfortable managing sleep problems, a consultation with a pediatrician or a sleep specialist is in order.

The adult with atopic dermatitis is a somewhat different animal and a formal sleep study may be indicated. Cognitive-behavioral therapy might be helpful for adult population but the investigators could find no trials of its use in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Convincing the parents of an atopic dermatitis patient that their family’s disturbed sleep may not only be the result of his/her itchy skin but may be a preexisting compounding problem may not be an easy sell. I hope if you can be open to the strong possibility that disordered sleep is not just the effect but in some ways may be a likely contributor to your patients’ atopic dermatitis, you may become more effective in managing the disease.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Daycare Providers’ Little Helper

It is no secret that we have a daycare problem in this country. Twenty percent of families spend more than $36,000 for child care annually. Three quarters of a single parent’s income is spent on infant care. The result is that more than $122 billion is syphoned out of our economy in lost productivity and income.

How we got into this situation is less clear. Women who once were stay-at-home moms have moved into the workplace. Families are more mobile and grandparents who had been a source of childcare may live hours away. And, when they are nearby grandparents may themselves been forced to remain employed for economic reasons.

Despite the increase demand the market has failed to respond with more daycare providers because with a median hourly wage of less than $15.00 it is difficult to attract applicants from a pool of potential employees that is already in great demand.

And, let’s be honest, long hours cooped up inside with infants and toddlers isn’t the right job for everyone. For the most successful, although maybe not financially, providing daycare is truly a labor of love. There are high school and community college courses taught on child development and day care management. Experienced providers can be a source of tips-of-the trade to those just starting out. But, when there are three infants crying, two diapers to be changed, and a toddler heading toward a tantrum, two experienced providers may not be enough to calm the turbulent waters.

A recent article in my local newspaper provided stark evidence of how serious our daycare situation has become. Although the daycare owner denies the allegation, the Department of Health and Human Service told the parents that the investigation currently supports their complaints that the children had been given melatonin gummies without their permission. Final action is pending but it is likely the daycare will lose its license. Not surprisingly the parents have already removed their children.

Curious about whether this situation was an isolated event, it didn’t take Google too long to find evidence of other daycares in which children had been given sleep-related medications without their parents’ permission. In May 2024 a daycare provider and three of her employees in Manchester, New Hampshire, were arrested and charged with endangering the welfare of a child after allegedly spiking their charges food with melatonin. Lest you think drugging infants in daycare is just a New England thing, my research found a news story dating back to 2003 that reported on several cases in which daycare providers had been administering diphenhydramine without parents permission. In one instance there was a fatal outcome. While melatonin does not pose a health risk on a par with diphenhydramine, the issue is the fact that the parents were not consulted.

I suspect that these two incidents in Maine and New Hampshire are not isolated events and melatonin has replaced diphenhydramine as the daycare provider’s “little helper” nationwide. It’s not clear how we as pediatricians can help police this practice, other than suggesting to parents that they initiate dialogues about napping strategies with their daycare providers. Not with an accusatory tone but more of a sharing about what tricks each party uses to make napping happen. It may be that the daycare provider has some valuable and sound advice that the parents can adapt to their home situation. However, if the daycare provider’s explanation for why the child naps well doesn’t sound right or the child is unusually drowsy after daycare visits they should share their concerns with us a pediatric health care advisors.

Dr Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

It is no secret that we have a daycare problem in this country. Twenty percent of families spend more than $36,000 for child care annually. Three quarters of a single parent’s income is spent on infant care. The result is that more than $122 billion is syphoned out of our economy in lost productivity and income.

How we got into this situation is less clear. Women who once were stay-at-home moms have moved into the workplace. Families are more mobile and grandparents who had been a source of childcare may live hours away. And, when they are nearby grandparents may themselves been forced to remain employed for economic reasons.

Despite the increase demand the market has failed to respond with more daycare providers because with a median hourly wage of less than $15.00 it is difficult to attract applicants from a pool of potential employees that is already in great demand.

And, let’s be honest, long hours cooped up inside with infants and toddlers isn’t the right job for everyone. For the most successful, although maybe not financially, providing daycare is truly a labor of love. There are high school and community college courses taught on child development and day care management. Experienced providers can be a source of tips-of-the trade to those just starting out. But, when there are three infants crying, two diapers to be changed, and a toddler heading toward a tantrum, two experienced providers may not be enough to calm the turbulent waters.

A recent article in my local newspaper provided stark evidence of how serious our daycare situation has become. Although the daycare owner denies the allegation, the Department of Health and Human Service told the parents that the investigation currently supports their complaints that the children had been given melatonin gummies without their permission. Final action is pending but it is likely the daycare will lose its license. Not surprisingly the parents have already removed their children.

Curious about whether this situation was an isolated event, it didn’t take Google too long to find evidence of other daycares in which children had been given sleep-related medications without their parents’ permission. In May 2024 a daycare provider and three of her employees in Manchester, New Hampshire, were arrested and charged with endangering the welfare of a child after allegedly spiking their charges food with melatonin. Lest you think drugging infants in daycare is just a New England thing, my research found a news story dating back to 2003 that reported on several cases in which daycare providers had been administering diphenhydramine without parents permission. In one instance there was a fatal outcome. While melatonin does not pose a health risk on a par with diphenhydramine, the issue is the fact that the parents were not consulted.

I suspect that these two incidents in Maine and New Hampshire are not isolated events and melatonin has replaced diphenhydramine as the daycare provider’s “little helper” nationwide. It’s not clear how we as pediatricians can help police this practice, other than suggesting to parents that they initiate dialogues about napping strategies with their daycare providers. Not with an accusatory tone but more of a sharing about what tricks each party uses to make napping happen. It may be that the daycare provider has some valuable and sound advice that the parents can adapt to their home situation. However, if the daycare provider’s explanation for why the child naps well doesn’t sound right or the child is unusually drowsy after daycare visits they should share their concerns with us a pediatric health care advisors.

Dr Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

It is no secret that we have a daycare problem in this country. Twenty percent of families spend more than $36,000 for child care annually. Three quarters of a single parent’s income is spent on infant care. The result is that more than $122 billion is syphoned out of our economy in lost productivity and income.

How we got into this situation is less clear. Women who once were stay-at-home moms have moved into the workplace. Families are more mobile and grandparents who had been a source of childcare may live hours away. And, when they are nearby grandparents may themselves been forced to remain employed for economic reasons.

Despite the increase demand the market has failed to respond with more daycare providers because with a median hourly wage of less than $15.00 it is difficult to attract applicants from a pool of potential employees that is already in great demand.

And, let’s be honest, long hours cooped up inside with infants and toddlers isn’t the right job for everyone. For the most successful, although maybe not financially, providing daycare is truly a labor of love. There are high school and community college courses taught on child development and day care management. Experienced providers can be a source of tips-of-the trade to those just starting out. But, when there are three infants crying, two diapers to be changed, and a toddler heading toward a tantrum, two experienced providers may not be enough to calm the turbulent waters.

A recent article in my local newspaper provided stark evidence of how serious our daycare situation has become. Although the daycare owner denies the allegation, the Department of Health and Human Service told the parents that the investigation currently supports their complaints that the children had been given melatonin gummies without their permission. Final action is pending but it is likely the daycare will lose its license. Not surprisingly the parents have already removed their children.

Curious about whether this situation was an isolated event, it didn’t take Google too long to find evidence of other daycares in which children had been given sleep-related medications without their parents’ permission. In May 2024 a daycare provider and three of her employees in Manchester, New Hampshire, were arrested and charged with endangering the welfare of a child after allegedly spiking their charges food with melatonin. Lest you think drugging infants in daycare is just a New England thing, my research found a news story dating back to 2003 that reported on several cases in which daycare providers had been administering diphenhydramine without parents permission. In one instance there was a fatal outcome. While melatonin does not pose a health risk on a par with diphenhydramine, the issue is the fact that the parents were not consulted.

I suspect that these two incidents in Maine and New Hampshire are not isolated events and melatonin has replaced diphenhydramine as the daycare provider’s “little helper” nationwide. It’s not clear how we as pediatricians can help police this practice, other than suggesting to parents that they initiate dialogues about napping strategies with their daycare providers. Not with an accusatory tone but more of a sharing about what tricks each party uses to make napping happen. It may be that the daycare provider has some valuable and sound advice that the parents can adapt to their home situation. However, if the daycare provider’s explanation for why the child naps well doesn’t sound right or the child is unusually drowsy after daycare visits they should share their concerns with us a pediatric health care advisors.

Dr Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Implementation Research: Simple Text Reminders Help Increase Vaccine Uptake

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss a very interesting paper that appeared in Nature:“Megastudy Shows That Reminders Boost Vaccination but Adding Free Rides Does Not.”

Obviously, the paper has a provocative title. This is really an excellent example of what one might call implementation research, or quite frankly, what might work and what might not work in terms of having a very pragmatic goal. In this case, it was how do we get people to receive vaccinations.

This specific study looked at individuals who were scheduled to receive or were candidates to receive COVID-19 booster vaccinations. The question came up: If you gave them free rides to the location — this is obviously a high-risk population — would that increase the vaccination rate vs the other item that they were looking at here, which was potentially texting them to remind them?

The study very importantly and relevantly demonstrated, quite nicely, that offering free rides did not make a difference, but sending texts to remind them increased the 30-day vaccination rate in this population by 21%.

Again, it was a very pragmatic question that the trial addressed, and one might use this information in the future to increase the vaccination rate of a population where it is critical to do so. This type of research, which involves looking at very pragmatic questions and answering what is the optimal and most cost-effective way of doing it, should be encouraged.

I encourage you to look at this paper if you’re interested in this topic.

Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, has disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss a very interesting paper that appeared in Nature:“Megastudy Shows That Reminders Boost Vaccination but Adding Free Rides Does Not.”

Obviously, the paper has a provocative title. This is really an excellent example of what one might call implementation research, or quite frankly, what might work and what might not work in terms of having a very pragmatic goal. In this case, it was how do we get people to receive vaccinations.

This specific study looked at individuals who were scheduled to receive or were candidates to receive COVID-19 booster vaccinations. The question came up: If you gave them free rides to the location — this is obviously a high-risk population — would that increase the vaccination rate vs the other item that they were looking at here, which was potentially texting them to remind them?

The study very importantly and relevantly demonstrated, quite nicely, that offering free rides did not make a difference, but sending texts to remind them increased the 30-day vaccination rate in this population by 21%.

Again, it was a very pragmatic question that the trial addressed, and one might use this information in the future to increase the vaccination rate of a population where it is critical to do so. This type of research, which involves looking at very pragmatic questions and answering what is the optimal and most cost-effective way of doing it, should be encouraged.

I encourage you to look at this paper if you’re interested in this topic.

Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, has disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss a very interesting paper that appeared in Nature:“Megastudy Shows That Reminders Boost Vaccination but Adding Free Rides Does Not.”

Obviously, the paper has a provocative title. This is really an excellent example of what one might call implementation research, or quite frankly, what might work and what might not work in terms of having a very pragmatic goal. In this case, it was how do we get people to receive vaccinations.

This specific study looked at individuals who were scheduled to receive or were candidates to receive COVID-19 booster vaccinations. The question came up: If you gave them free rides to the location — this is obviously a high-risk population — would that increase the vaccination rate vs the other item that they were looking at here, which was potentially texting them to remind them?

The study very importantly and relevantly demonstrated, quite nicely, that offering free rides did not make a difference, but sending texts to remind them increased the 30-day vaccination rate in this population by 21%.

Again, it was a very pragmatic question that the trial addressed, and one might use this information in the future to increase the vaccination rate of a population where it is critical to do so. This type of research, which involves looking at very pragmatic questions and answering what is the optimal and most cost-effective way of doing it, should be encouraged.

I encourage you to look at this paper if you’re interested in this topic.

Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, has disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

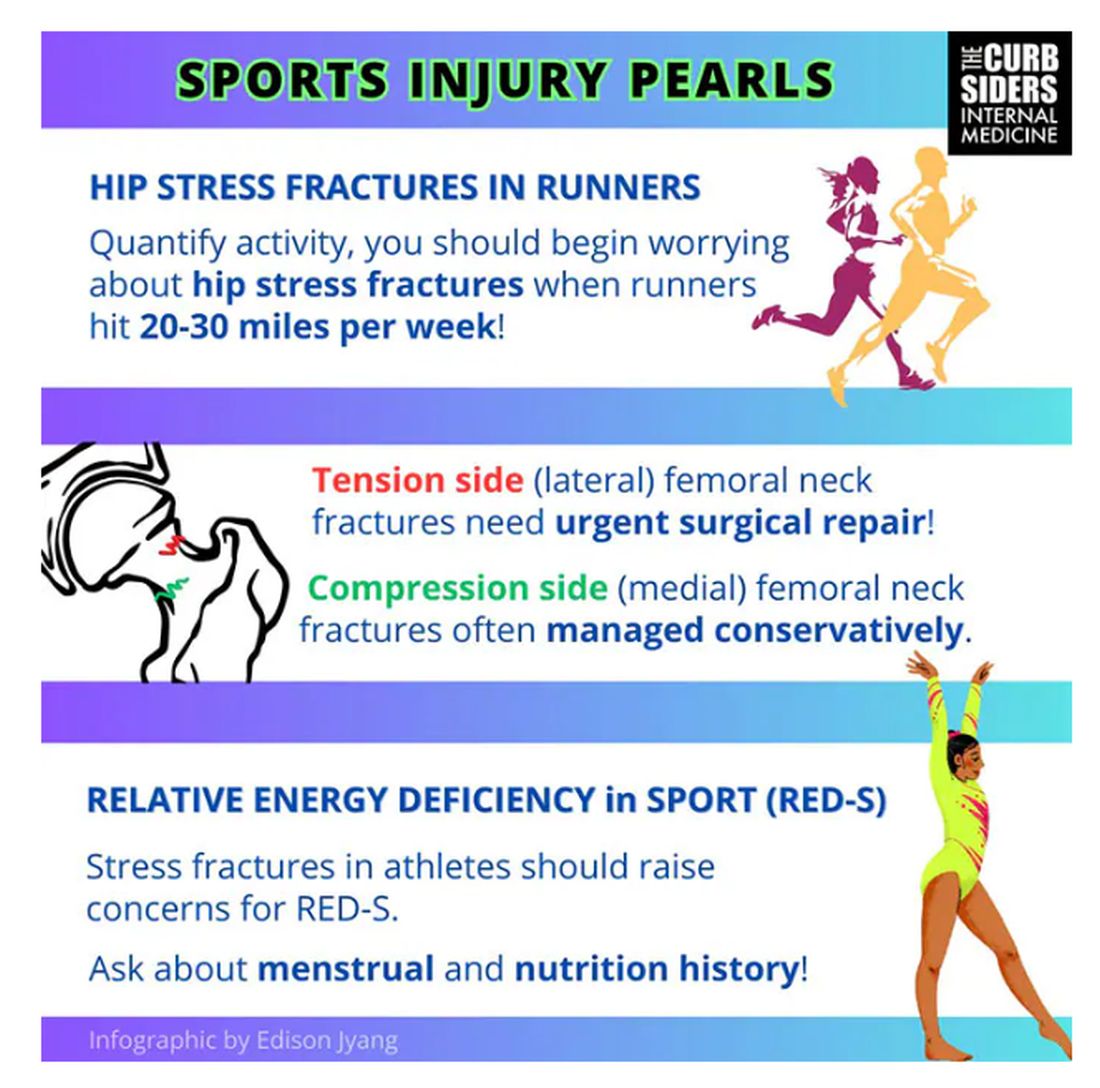

Sports Injuries of the Hip in Primary Care

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.

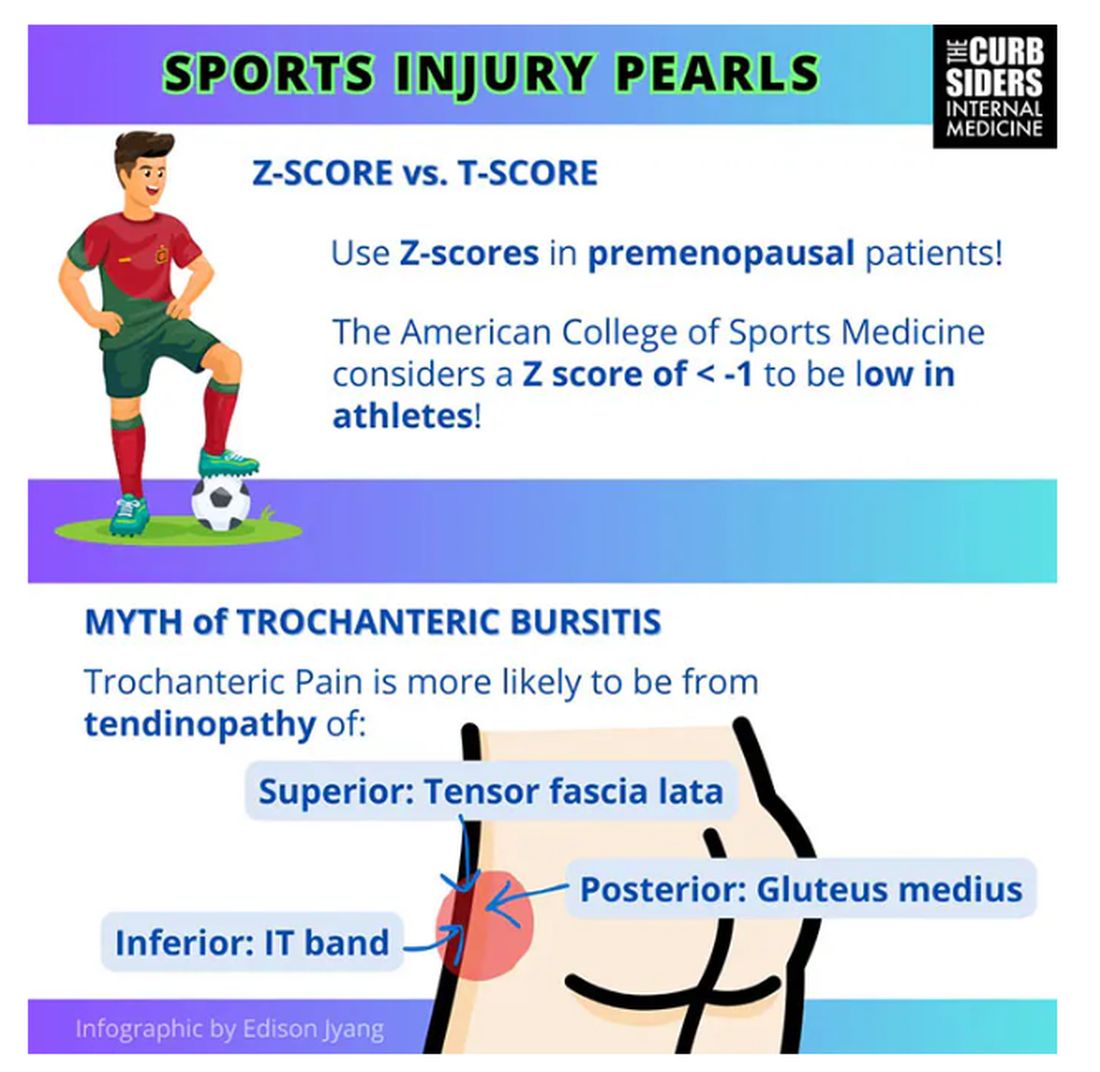

Watto: Whenever a patient presented with hip pain, I used to pray it was trochanteric bursitis, which now I know is not really the right thing to think about. Intra-articular hip pain presents as anterior hip pain, usually in the crease of the hip. Depending on the patient’s age and history, the differential for that type of pain includes iliopsoas tendonitis, FAI syndrome, a labral tear, a bone stress injury of the femoral neck, or osteoarthritis.

So, what exactly is FAI and how might we diagnose it?

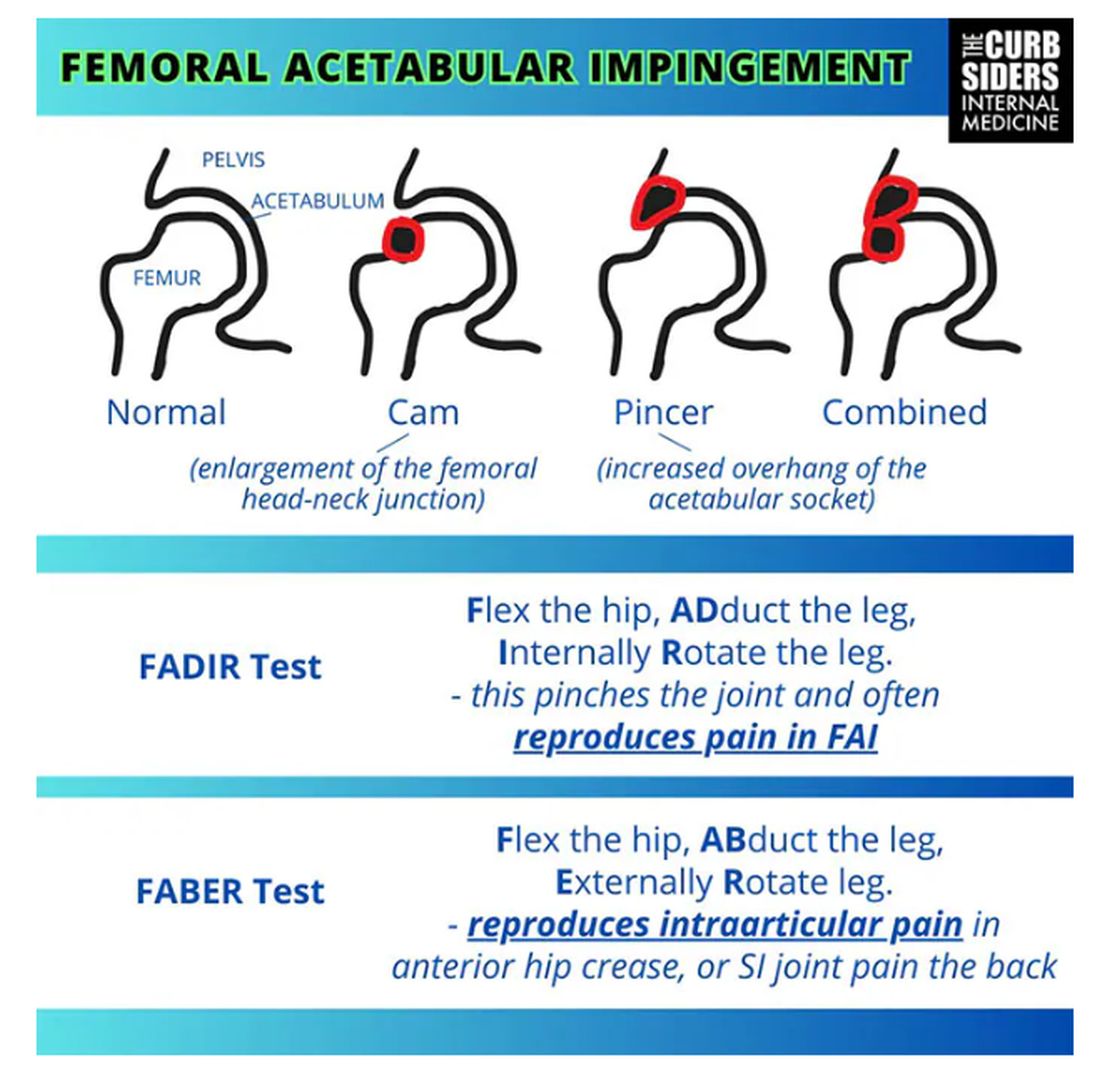

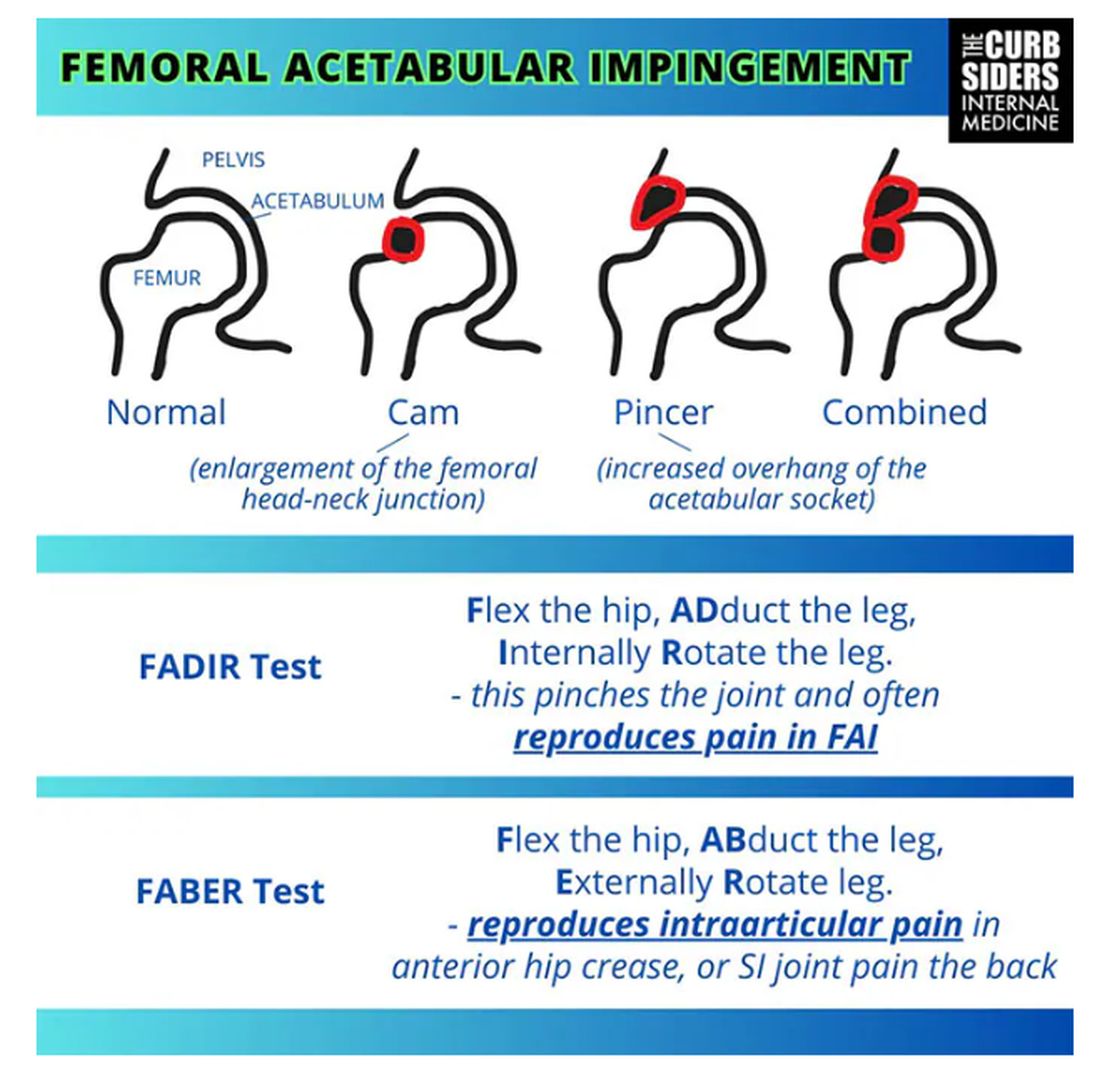

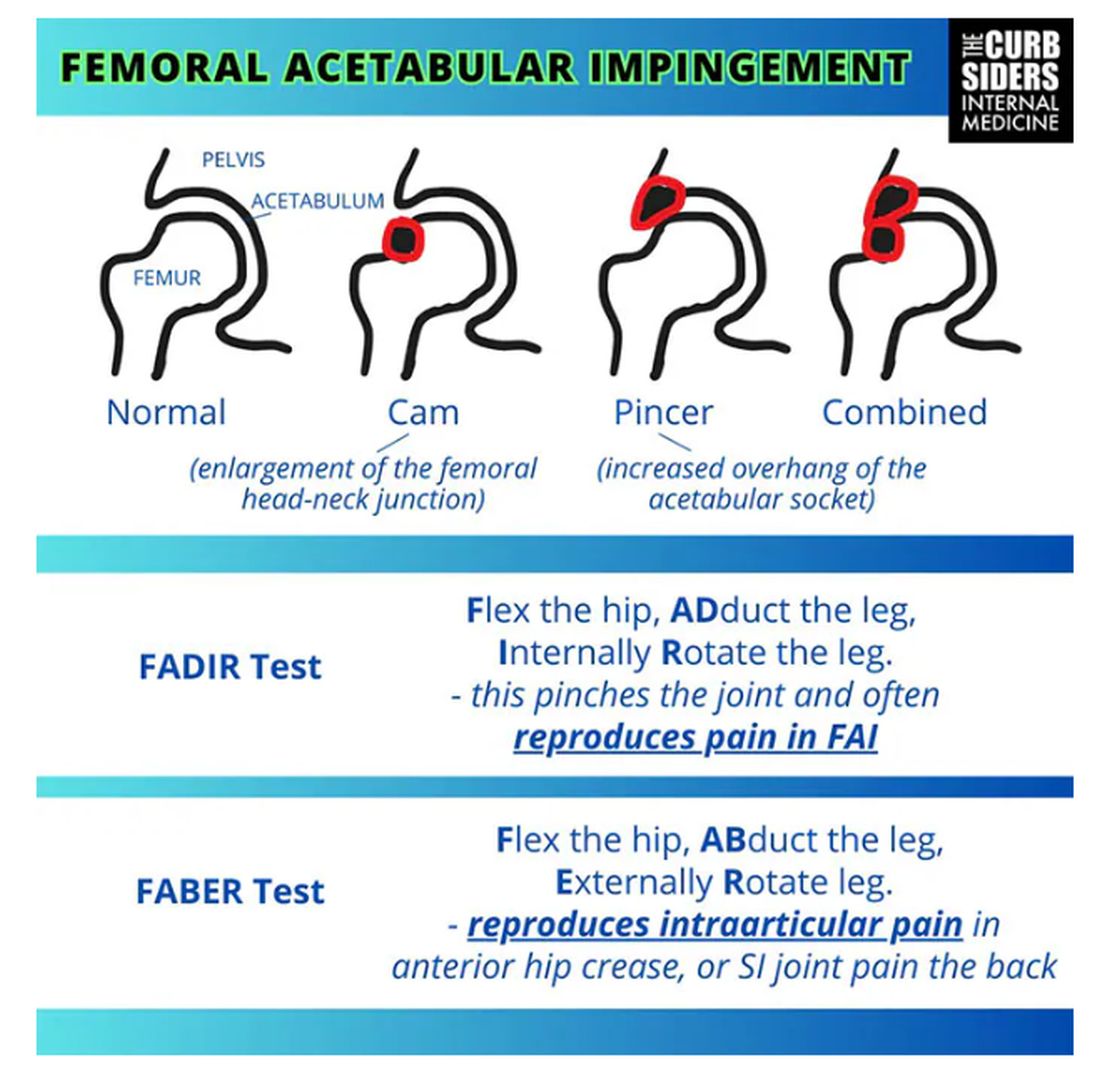

Williams: FAI is what the cool kids call femoral acetabular impingement, and it’s exactly what it sounds like.

Something is pinching or impinging upon the joint itself and preventing full range of motion. This is a ball-and-socket joint, so it should have tremendous range of motion, able to move in all planes. If it’s impinged, then pain will occur with certain movements. There’s a cam type, which is characterized by enlargement of the femoral head neck junction, or a pincer type, which has more to do with overhang of the acetabulum, and it can also be mixed. In any case, impingement upon the patient’s full range of motion results in pain.

You evaluate this with a couple of tests — the FABER and the FADIR.

The FABER is flexion, abduction, and external rotation, and the FADIR is flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. If you elicit anterior pain with either of those tests, it’s probably one of the intra-articular pathologies, although it is hard to know for sure which one it is because these tests are fairly sensitive but not very specific.

Watto: You can get x-rays to help with the diagnosis. You would order two views of the hip: an AP of the pelvis, which is just a straight-on shot to look for arthritis or fracture. Is there a healthy joint line there? The second is the Dunn view, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted about 20 degrees. You are looking for fracture or impingement. You can diagnose FAI based on that view, and you might be able to diagnose a hip stress injury or osteoarthritis.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to see a labral tear, but Dr Senter said that both FAI and labral tears are treated the same way, with physical therapy. Patients with FAI who aren’t getting better might end up going for surgery, so at some point I would refer them to orthopedic surgery. But I feel much more comfortable now diagnosing these conditions with these tests.

Let’s talk a little bit about trochanteric pain syndrome. I used to think it was all bursitis. Why is that not correct?

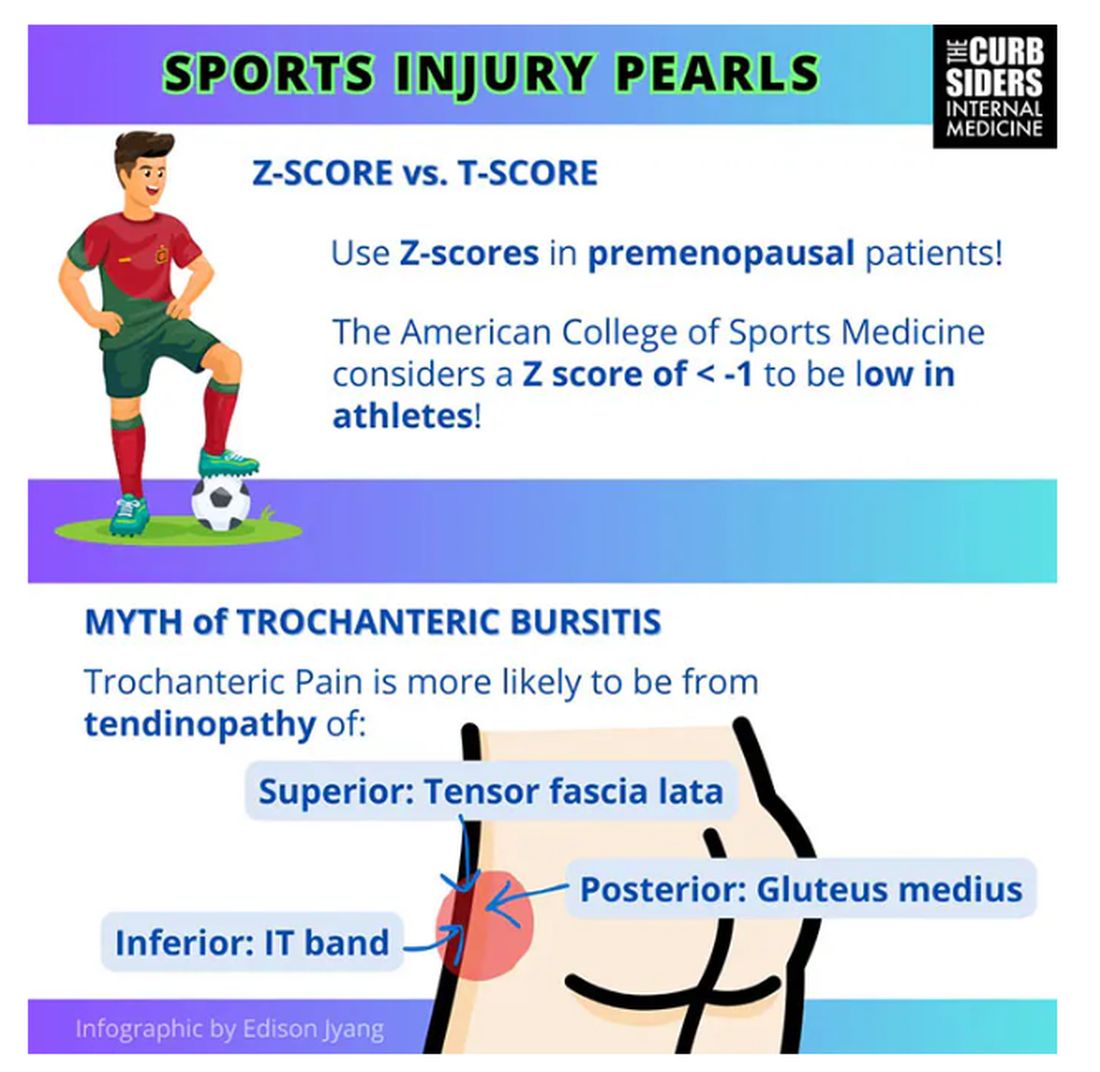

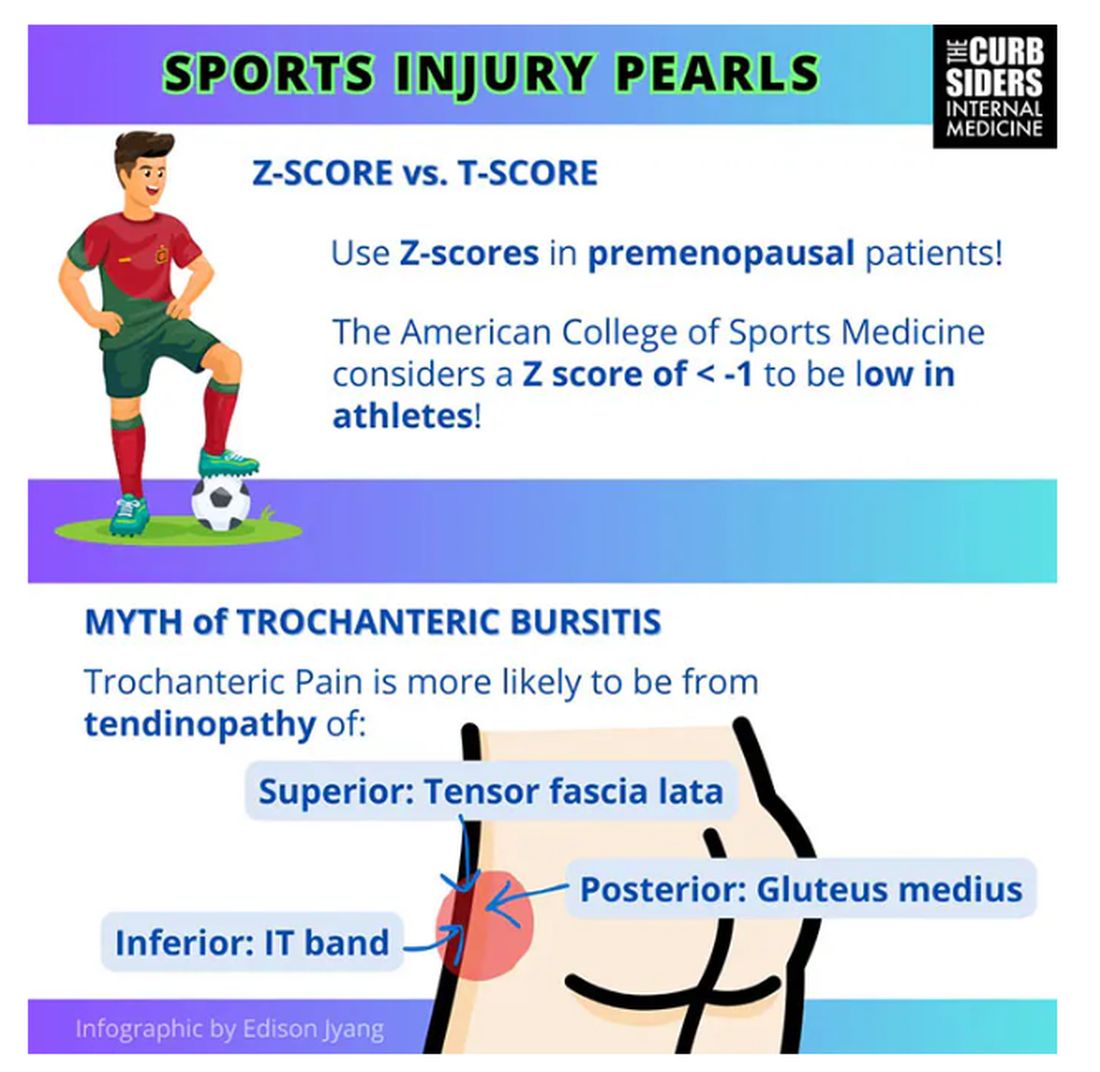

Williams: It’s nice of you to feign ignorance for the purpose of education. It used to be thought of as bursitis, but these days we know it is probably more likely a tendinopathy.

Trochanteric pain syndrome was formerly known as trochanteric bursitis, but the bursa is not typically involved. Trochanteric pain syndrome is a tendinopathy of the surrounding structures: the gluteus medius, the iliotibial band, and the tensor fascia latae. The way these structures relate looks a bit like the face of a clock, as you can see on the infographic. In general, you manage this condition the same way you do with bursitis — physical therapy. You can also give corticosteroid injections. Physical therapy is probably more durable in terms of pain relief and functionality, but in the short term, corticosteroids might provide some degree of analgesia as well.

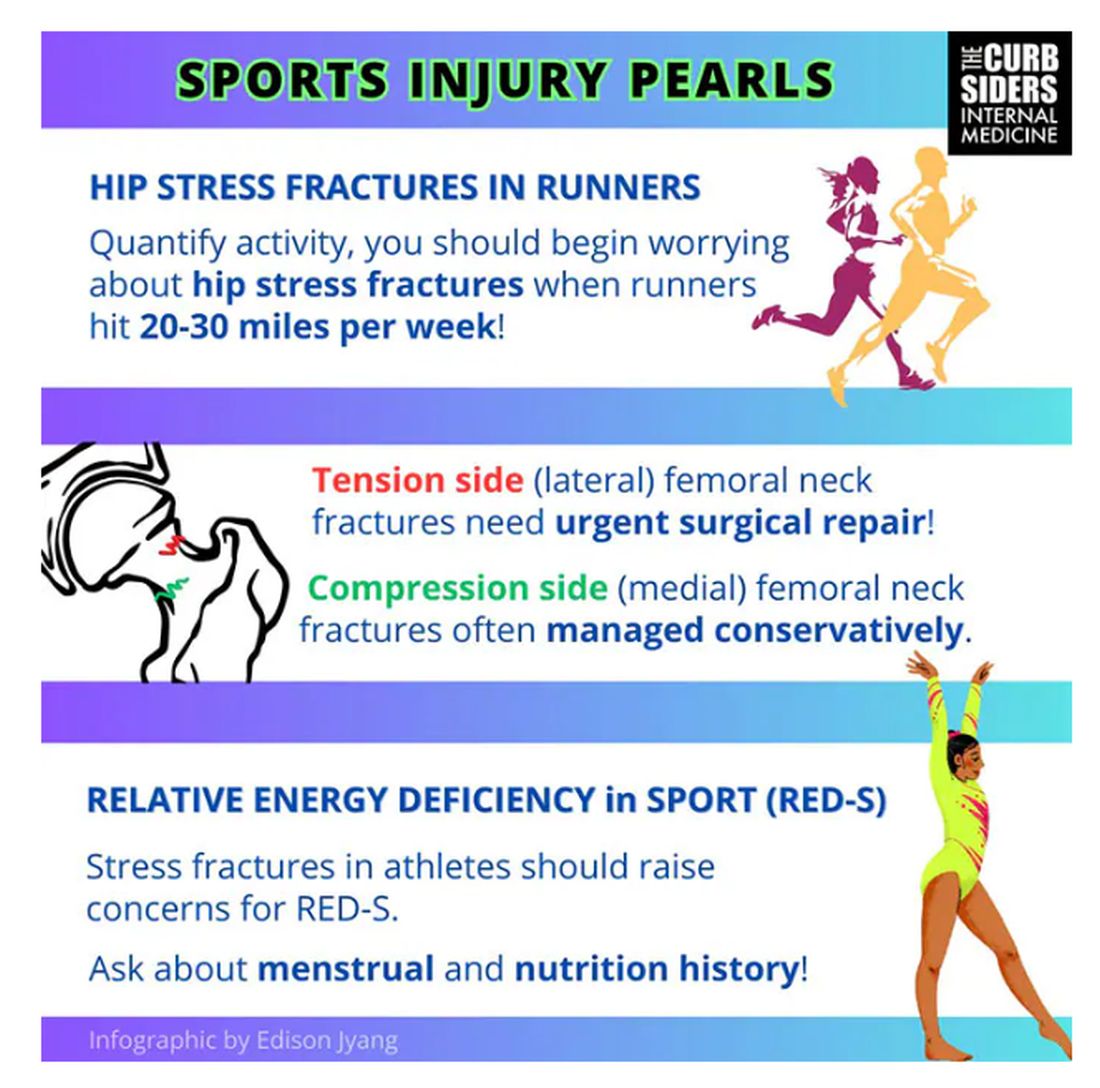

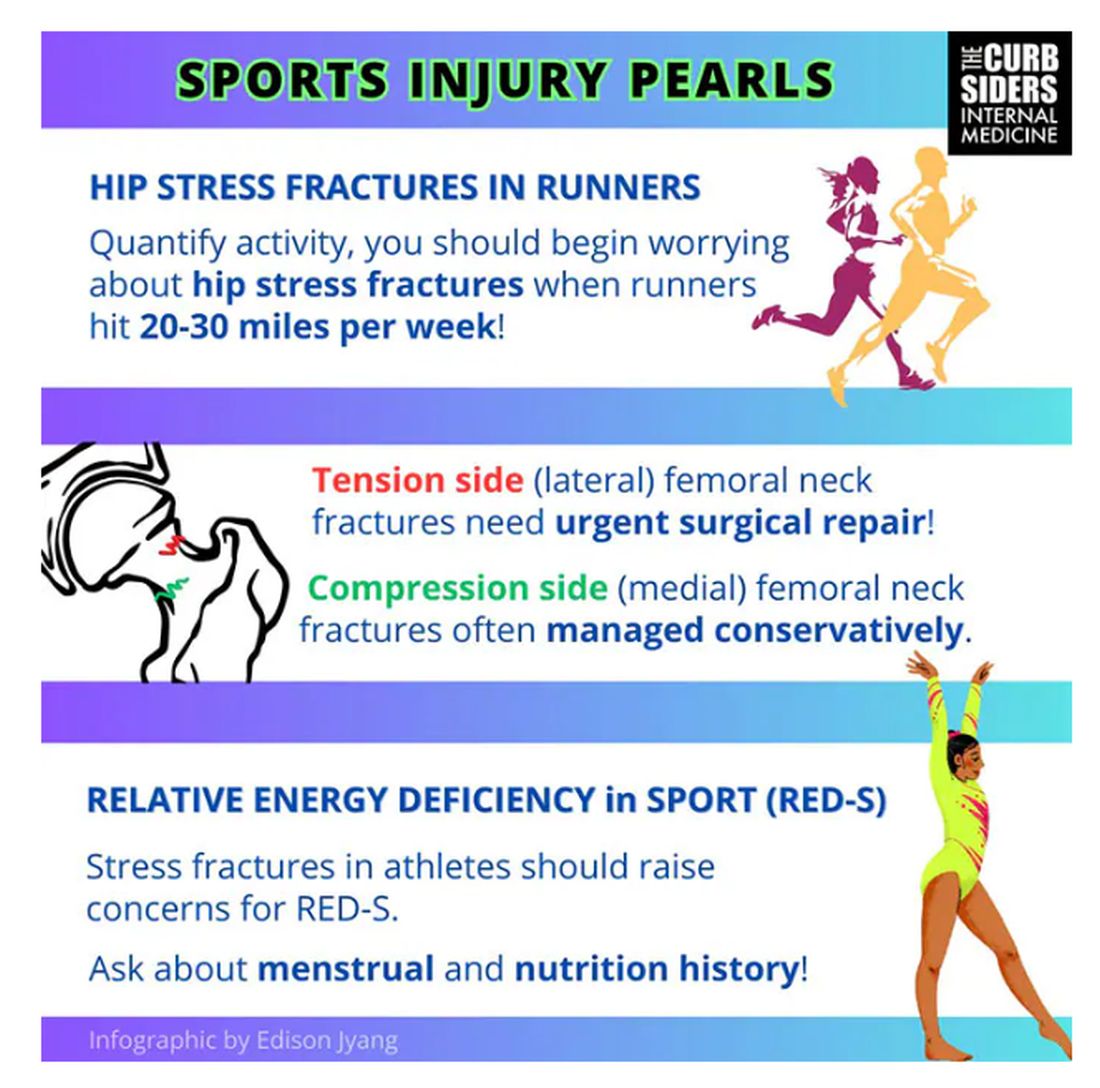

Watto: The last thing we wanted to mention is bone stress injury, which can occur in high-mileage runners (20 miles or more per week). Patients with bone stress injury need to rest, usually non‒weight bearing, for a period of time.

Treatment of a bone stress fracture depends on which side it’s on (top or bottom). If it’s on the top of the femoral neck (the tension side), it has to be fixed. If it’s on the compression side (the bottom side of the femoral neck), it might be able to be managed conservatively, but many patients are going to need surgery. This is a big deal. But it’s a spectrum; in some cases the bone is merely irritated and unhappy, without a break in the cortex. Those patients might not need surgery.

In patients with a fracture of the femoral neck — especially younger, healthier patients — you should think about getting a bone density test and screening for relative energy deficiency in sport. This used to be called the female athlete triad, which includes disrupted menstrual cycles, being underweight, and fracture. We should be screening patients, asking them in a nonjudgmental way about their relationship with food, to make sure they are getting an appropriate number of calories.

They are actually in an energy deficit. They’re not eating enough to maintain a healthy body with so much activity.

Williams: If you’re interested in this topic, you should refer to the full podcast with Dr Senter which is chock-full of helpful information.

Dr Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with The Curbsiders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.

Watto: Whenever a patient presented with hip pain, I used to pray it was trochanteric bursitis, which now I know is not really the right thing to think about. Intra-articular hip pain presents as anterior hip pain, usually in the crease of the hip. Depending on the patient’s age and history, the differential for that type of pain includes iliopsoas tendonitis, FAI syndrome, a labral tear, a bone stress injury of the femoral neck, or osteoarthritis.

So, what exactly is FAI and how might we diagnose it?

Williams: FAI is what the cool kids call femoral acetabular impingement, and it’s exactly what it sounds like.

Something is pinching or impinging upon the joint itself and preventing full range of motion. This is a ball-and-socket joint, so it should have tremendous range of motion, able to move in all planes. If it’s impinged, then pain will occur with certain movements. There’s a cam type, which is characterized by enlargement of the femoral head neck junction, or a pincer type, which has more to do with overhang of the acetabulum, and it can also be mixed. In any case, impingement upon the patient’s full range of motion results in pain.

You evaluate this with a couple of tests — the FABER and the FADIR.

The FABER is flexion, abduction, and external rotation, and the FADIR is flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. If you elicit anterior pain with either of those tests, it’s probably one of the intra-articular pathologies, although it is hard to know for sure which one it is because these tests are fairly sensitive but not very specific.

Watto: You can get x-rays to help with the diagnosis. You would order two views of the hip: an AP of the pelvis, which is just a straight-on shot to look for arthritis or fracture. Is there a healthy joint line there? The second is the Dunn view, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted about 20 degrees. You are looking for fracture or impingement. You can diagnose FAI based on that view, and you might be able to diagnose a hip stress injury or osteoarthritis.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to see a labral tear, but Dr Senter said that both FAI and labral tears are treated the same way, with physical therapy. Patients with FAI who aren’t getting better might end up going for surgery, so at some point I would refer them to orthopedic surgery. But I feel much more comfortable now diagnosing these conditions with these tests.

Let’s talk a little bit about trochanteric pain syndrome. I used to think it was all bursitis. Why is that not correct?

Williams: It’s nice of you to feign ignorance for the purpose of education. It used to be thought of as bursitis, but these days we know it is probably more likely a tendinopathy.

Trochanteric pain syndrome was formerly known as trochanteric bursitis, but the bursa is not typically involved. Trochanteric pain syndrome is a tendinopathy of the surrounding structures: the gluteus medius, the iliotibial band, and the tensor fascia latae. The way these structures relate looks a bit like the face of a clock, as you can see on the infographic. In general, you manage this condition the same way you do with bursitis — physical therapy. You can also give corticosteroid injections. Physical therapy is probably more durable in terms of pain relief and functionality, but in the short term, corticosteroids might provide some degree of analgesia as well.

Watto: The last thing we wanted to mention is bone stress injury, which can occur in high-mileage runners (20 miles or more per week). Patients with bone stress injury need to rest, usually non‒weight bearing, for a period of time.

Treatment of a bone stress fracture depends on which side it’s on (top or bottom). If it’s on the top of the femoral neck (the tension side), it has to be fixed. If it’s on the compression side (the bottom side of the femoral neck), it might be able to be managed conservatively, but many patients are going to need surgery. This is a big deal. But it’s a spectrum; in some cases the bone is merely irritated and unhappy, without a break in the cortex. Those patients might not need surgery.

In patients with a fracture of the femoral neck — especially younger, healthier patients — you should think about getting a bone density test and screening for relative energy deficiency in sport. This used to be called the female athlete triad, which includes disrupted menstrual cycles, being underweight, and fracture. We should be screening patients, asking them in a nonjudgmental way about their relationship with food, to make sure they are getting an appropriate number of calories.

They are actually in an energy deficit. They’re not eating enough to maintain a healthy body with so much activity.

Williams: If you’re interested in this topic, you should refer to the full podcast with Dr Senter which is chock-full of helpful information.

Dr Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with The Curbsiders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.

Watto: Whenever a patient presented with hip pain, I used to pray it was trochanteric bursitis, which now I know is not really the right thing to think about. Intra-articular hip pain presents as anterior hip pain, usually in the crease of the hip. Depending on the patient’s age and history, the differential for that type of pain includes iliopsoas tendonitis, FAI syndrome, a labral tear, a bone stress injury of the femoral neck, or osteoarthritis.

So, what exactly is FAI and how might we diagnose it?

Williams: FAI is what the cool kids call femoral acetabular impingement, and it’s exactly what it sounds like.

Something is pinching or impinging upon the joint itself and preventing full range of motion. This is a ball-and-socket joint, so it should have tremendous range of motion, able to move in all planes. If it’s impinged, then pain will occur with certain movements. There’s a cam type, which is characterized by enlargement of the femoral head neck junction, or a pincer type, which has more to do with overhang of the acetabulum, and it can also be mixed. In any case, impingement upon the patient’s full range of motion results in pain.

You evaluate this with a couple of tests — the FABER and the FADIR.

The FABER is flexion, abduction, and external rotation, and the FADIR is flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. If you elicit anterior pain with either of those tests, it’s probably one of the intra-articular pathologies, although it is hard to know for sure which one it is because these tests are fairly sensitive but not very specific.

Watto: You can get x-rays to help with the diagnosis. You would order two views of the hip: an AP of the pelvis, which is just a straight-on shot to look for arthritis or fracture. Is there a healthy joint line there? The second is the Dunn view, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted about 20 degrees. You are looking for fracture or impingement. You can diagnose FAI based on that view, and you might be able to diagnose a hip stress injury or osteoarthritis.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to see a labral tear, but Dr Senter said that both FAI and labral tears are treated the same way, with physical therapy. Patients with FAI who aren’t getting better might end up going for surgery, so at some point I would refer them to orthopedic surgery. But I feel much more comfortable now diagnosing these conditions with these tests.

Let’s talk a little bit about trochanteric pain syndrome. I used to think it was all bursitis. Why is that not correct?

Williams: It’s nice of you to feign ignorance for the purpose of education. It used to be thought of as bursitis, but these days we know it is probably more likely a tendinopathy.

Trochanteric pain syndrome was formerly known as trochanteric bursitis, but the bursa is not typically involved. Trochanteric pain syndrome is a tendinopathy of the surrounding structures: the gluteus medius, the iliotibial band, and the tensor fascia latae. The way these structures relate looks a bit like the face of a clock, as you can see on the infographic. In general, you manage this condition the same way you do with bursitis — physical therapy. You can also give corticosteroid injections. Physical therapy is probably more durable in terms of pain relief and functionality, but in the short term, corticosteroids might provide some degree of analgesia as well.

Watto: The last thing we wanted to mention is bone stress injury, which can occur in high-mileage runners (20 miles or more per week). Patients with bone stress injury need to rest, usually non‒weight bearing, for a period of time.

Treatment of a bone stress fracture depends on which side it’s on (top or bottom). If it’s on the top of the femoral neck (the tension side), it has to be fixed. If it’s on the compression side (the bottom side of the femoral neck), it might be able to be managed conservatively, but many patients are going to need surgery. This is a big deal. But it’s a spectrum; in some cases the bone is merely irritated and unhappy, without a break in the cortex. Those patients might not need surgery.

In patients with a fracture of the femoral neck — especially younger, healthier patients — you should think about getting a bone density test and screening for relative energy deficiency in sport. This used to be called the female athlete triad, which includes disrupted menstrual cycles, being underweight, and fracture. We should be screening patients, asking them in a nonjudgmental way about their relationship with food, to make sure they are getting an appropriate number of calories.

They are actually in an energy deficit. They’re not eating enough to maintain a healthy body with so much activity.

Williams: If you’re interested in this topic, you should refer to the full podcast with Dr Senter which is chock-full of helpful information.

Dr Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with The Curbsiders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ADHD Myths

In the second half of the school year, you may find that there is a surge of families coming to appointments with concerns about school performance, wondering if their child has ADHD. We expect you are very familiar with this condition, both diagnosing and treating it. So this month we will offer “mythbusters” for ADHD: Responding to common misperceptions about ADHD with a summary of what the research has demonstrated as emerging facts, what is clearly fiction and what falls into the gray space between.

Demographics

A CDC survey of parents from 2022 indicates that 11.4% of children aged 3-17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD in the United States. This is more than double the ADHD global prevalence of 5%, suggesting that there is overdiagnosis of this condition in this country. Boys are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed (14.5%) as girls (8%), and White children were more likely to be diagnosed than were Black and Hispanic children. The prevalence of ADHD diagnosis decreases as family income increases, and the condition is more frequently diagnosed in 12- to 17-year-olds than in children 11 and younger. The great majority of youth with an ADHD diagnosis (78%) have at least one co-occurring psychiatric condition. Of the children diagnosed with ADHD, slightly over half receive medication treatment (53.6%) whereas nearly a third (30.1%) receive no ADHD-specific treatment.

The Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), a large (600 children, aged 7-9 years), multicenter, longitudinal study of treatment outcomes for medication as well as behavioral and combination therapies demonstrated in every site that medication alone and combination therapy were significantly superior to intensive behavioral treatment alone and to routine community care in the reduction of ADHD symptoms. Of note, problems commonly associated with ADHD (parent-child conflict, anxiety symptoms, poor academic performance, and limited social skills) improved only with the combination treatment. This suggests that while core ADHD symptoms require medication, associated problems will also require behavioral treatment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has a useful resource guide (healthychildren.org) highlighting the possible symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that should be investigated when considering this diagnosis. It is a clinical diagnosis, but screening instruments (such as the Vanderbilt) can be very helpful to identifying symptoms that should be present in more than one setting (home and school). While a child with ADHD can appear calm and focused when receiving direct one-to-one attention (as during a pediatrician’s appointment), symptoms may flourish in less structured or supervised settings. Sometimes parents are keen reporters of a child’s behaviors, but some loving (and exhausted) parents may overreact to a normal degree of inattention or disobedience. This can be especially true when a parent has a more detail-oriented temperament than the child, or with younger children and first-time parents. It is important to consider ADHD when you hear about social difficulties as well as academic ones, where there is a family history of ADHD or when a child is more impulsive, hyperactive, or inattentive than you would expect given their age and developmental stage. Confirm your clinical exam with teacher and parent reports. If the reports don’t line up or there are persistent learning problems in school, consider neuropsychological testing to root out a learning disability.

Myth 1: “ADHD never starts in adolescence; you can’t diagnose it after elementary school.”

Diagnostic criteria used to require that symptoms were present before the age of 7 (DSM 3). But current criteria allow for diagnosis before 12 years of age or after. While the consensus is that ADHD is present in childhood, its symptoms are often not apparent. This is because normal development in much younger children is marked by higher levels of activity, distractibility, and impulsivity. Also, children with inattentive-type ADHD may not be apparent to adults if they are performing adequately in school. These youth often do not present for assessment until the challenges of a busy course load make their inattention and consequent inefficiency apparent, in high school or even college. Certainly, when a teenager presents complaining of trouble performing at school, it is critical to rule out an overburdened schedule, anxiety or mood disorder, poor sleep habits or sleep disorder, and substance use disorders, all of which are more common in adolescence. But inattentive-type ADHD that was previously missed is also a possibility worth investigating.

Myth 2: “Most children outgrow ADHD; it’s best to find natural solutions and wait it out.”

Early epidemiological studies suggested that as many as 30% of ADHD cases remitted by adulthood, but more recent data has adjusted that number down substantially, closer to 9%. Interestingly, it appears that 10% of patients will experience sustained symptoms, 9% will experience recovery (sustained remission without treatment), and a large majority will have a remitting and relapsing course into adulthood.1

This emerging evidence suggests that ADHD is almost always a lifelong condition. Untreated, it can threaten healthy development (including social skills and self-esteem) and day-to-day function (academic, social and athletic performance and even vulnerability to accidents) in ways that can be profound. The MTA Study has powerfully demonstrated the efficacy of pharmacological treatment and of specific behavioral treatments for ADHD and associated problems.

Myth 3: “You should exhaust natural cures first before trying medications.”

There has been a large amount of research into a variety of “natural” treatments for ADHD: special diets, supplements, increased exercise, and interventions like neurofeedback. While high-dose omega 3 fatty acid supplementation has demonstrated mild improvement in ADHD symptoms, no “natural” treatment has come close to the efficacy of stimulant medications. Interventions such as neurofeedback are expensive and time-consuming without any demonstrated efficacy. That said, improving a child’s routines around sleep, nutrition, and regular exercise are broadly useful strategies to improve any child’s (or adult’s) energy, impulse control, attention, motivation, and capacity to manage adversity and stress. Start any treatment by addressing sleep and exercise, including moderating time spent on screens, to support healthy function. But only medication will achieve symptom remission if your patient has underlying ADHD.

Myth 4: “All medications are equally effective in ADHD.”

It is well-established that stimulants are more effective than non-stimulants in the treatment of ADHD symptoms, with an effect size that is almost double that of non-stimulants.2

Amphetamine-based medications are slightly more effective than methylphenidate-based medications, but they are also generally less well-tolerated. Individual patients commonly have a better response to one class than the other, but you will need a trial to determine which one. It is reasonable to start a patient with an extended formulation of one class, based on your assessment of their vulnerability to side effects or a family history of medication response. Non-stimulants are of use when stimulants are not tolerated (ie, use of atomoxetine with patients who have comorbid anxiety), or to target specific symptoms, such as guanfacine or clonidine for hyperactivity.

Myth 5: “You can’t treat ADHD in substance abusing teens, stimulant medications are addictive.”

ADHD itself (not medications) increases the risk for addiction; those with ADHD are almost twice as likely to develop a substance use disorder, with highest risk for marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine abuse.3

This may be a function of limited impulse control or increased sensitivity in the ADHD brain to a drug’s addictive potential. Importantly, there is growing evidence that youth whose ADHD is treated pharmacologically are at lower risk for addiction than their peers with untreated ADHD.4

Those youth who have both ADHD and addiction are more likely to stay engaged in treatment for addiction when their ADHD is effectively treated, and there are medication formulations (lisdexamfetamine) that are safe in addiction (cannot be absorbed nasally or intravenously). It is important for you to talk about the heightened vulnerability to addiction with your ADHD patients and their parents, and the value of effective treatment in preventing this complication.

Myth 6: “ADHD is usually behavioral. Help parents to set rules, expectations, and limits instead of medicating the problem.”

Bad parenting does not cause ADHD. ADHD is marked by difficulties with impulse control, hyperactivity, and sustaining attention with matters that are not intrinsically engaging. “Behavioral issues” are patterns of behavior children learn to seek rewards or avoid negative consequences. Youth with ADHD can develop behavioral problems, but these are usually driven by negative feedback about their activity level, forgetfulness, or impulse control, which they are not able to change. This can lead to frustration and irritability, poor self-esteem, and even hopelessness — in parents and children both!

While parents are not the source of ADHD symptoms, there is a great deal of parent education and support that can be powerfully effective for these families. Parents benefit from learning strategies that can help their children to shift their attention, plan ahead, and manage frustration, especially for times when their children are unmedicated (vacations and bedtime). It is worth noting that ADHD is among the most heritable of youth psychiatric illnesses, so it is not uncommon for a parent of a child with ADHD to have similar symptoms. If the parents’ ADHD is untreated, they may be more impulsive themselves. They may also be extra sensitive to the qualities they dislike in themselves, inadvertently adding to their children’s sense of shame. ADHD is very treatable, and those with it can learn executive function skills and organizational strategies that can equip them to manage residual symptoms. Parents will benefit from strategies to understand their children and to help them learn adaptive skills in a realistic way. Your discussions with parents could help the families in your practice make adjustments that can translate into big differences in their child’s healthiest development.

Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Sibley MH et al. MTA Cooperative Group. Variable Patterns of Remission From ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;179(2):142-151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032.

2. Cortese S et al. Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of Medications for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5(9):727-738. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4.

3. Lee SS et al. Prospective Association of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Substance Use and Abuse/Dependence: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011 Apr;31(3):328-41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

4. Chorniy A, Kitashima L. Sex, Drugs, and ADHD: The Effects of ADHD Pharmacological Treatment on Teens’ Risky Behaviors. Labour Economics. 2016;43:87-105. doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.06.014.

In the second half of the school year, you may find that there is a surge of families coming to appointments with concerns about school performance, wondering if their child has ADHD. We expect you are very familiar with this condition, both diagnosing and treating it. So this month we will offer “mythbusters” for ADHD: Responding to common misperceptions about ADHD with a summary of what the research has demonstrated as emerging facts, what is clearly fiction and what falls into the gray space between.

Demographics

A CDC survey of parents from 2022 indicates that 11.4% of children aged 3-17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD in the United States. This is more than double the ADHD global prevalence of 5%, suggesting that there is overdiagnosis of this condition in this country. Boys are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed (14.5%) as girls (8%), and White children were more likely to be diagnosed than were Black and Hispanic children. The prevalence of ADHD diagnosis decreases as family income increases, and the condition is more frequently diagnosed in 12- to 17-year-olds than in children 11 and younger. The great majority of youth with an ADHD diagnosis (78%) have at least one co-occurring psychiatric condition. Of the children diagnosed with ADHD, slightly over half receive medication treatment (53.6%) whereas nearly a third (30.1%) receive no ADHD-specific treatment.

The Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), a large (600 children, aged 7-9 years), multicenter, longitudinal study of treatment outcomes for medication as well as behavioral and combination therapies demonstrated in every site that medication alone and combination therapy were significantly superior to intensive behavioral treatment alone and to routine community care in the reduction of ADHD symptoms. Of note, problems commonly associated with ADHD (parent-child conflict, anxiety symptoms, poor academic performance, and limited social skills) improved only with the combination treatment. This suggests that while core ADHD symptoms require medication, associated problems will also require behavioral treatment.