User login

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Two Perspectives

Dear colleagues,

: What is the role and optimal timing of colonoscopy? How can we best utilize radiologic studies like CTA or tagged RBC scans? How should we manage patients with recurrent or intermittent bleeding that defies localization?

In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. David Wan, Dr. Fredella Lee, and Dr. Zeyad Metwalli offer their expert insights on these difficult questions. Dr. Wan, drawing on over 15 years of experience as a GI hospitalist, shares – along with his coauthor Dr. Lee – a pragmatic approach to LGIB based on clinical patterns, evolving data, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Dr. Metwalli provides the interventional radiologist’s perspective, highlighting how angiographic techniques can complement GI management and introducing novel IR strategies for patients with recurrent or elusive bleeding.

We hope their perspectives will offer valuable guidance for your practice. Join the conversation on X at @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, and chief of endoscopy at West Haven VA Medical Center, both in Connecticut. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Management of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeds: GI Perspective

BY FREDELLA LEE, MD; DAVID WAN, MD

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) presents unique challenges. Much of this stems from the natural history of diverticular bleeding, the most common etiology of LGIB.

First, while bleeding can be severe, most will spontaneously stop. Second, despite our best efforts with imaging or colonoscopy, finding an intervenable lesion is rare. Third, LGIB has significant rates of rebleeding that are unpredictable.

While serving as a GI hospitalist for 15 years and after managing over 300 cases of LGIB, I often find myself frustrated and colonoscopy feels futile. So how can we rationally approach these patients? We will focus on three clinical questions to develop a framework for LGIB management.

- What is the role and timing for a colonoscopy?

- How do we best utilize radiologic tests?

- How can we prevent recurrent LGIB?

The Role of Colonoscopy

Traditionally, colonoscopy within 24 hours of presentation was recommended. This was based on retrospective cohort data showing higher endoscopic intervention rates and better clinical outcomes. However, this protocol requires patients to drink a significant volume of bowel preparation over a few hours (often requiring an NGT) to achieve clear rectal effluent. Moreover, one needs to mobilize a team (i.e., nurse, technician, anesthesiologist, and gastroenterologist), and find an appropriate location to scope (i.e., ED, ICU, or OR), Understandably, this is challenging, especially overnight. When the therapeutic yield is relatively low, this approach quickly loses enthusiasm.

Importantly, meta-analyses of the randomized controlled trials, have shown that urgent colonoscopies (<24 hours upon presentation), compared to elective colonoscopies (>24 hours upon presentation), do not improve clinical outcomes such as re-bleeding rates, transfusion requirements, mortality, or length of stay. In these studies, the endoscopic intervention rates were 17-34%, however, observational data shows rates of only 8%. In our practice, we will use a clear cap attachment device and water jet irrigation to increase the odds of detecting an active source of bleeding. Colonoscopy has a diagnostic yield of 95% – despite its low therapeutic yield; and while diverticular bleeds constitute up to 64% of cases, one does not want to miss colorectal cancer or other diagnoses. Regardless, there is generally no urgency to perform a colonoscopy. To quote a colleague, Dr. Elizabeth Ross, “there is no such thing as door-to-butt time.”

The Role of Radiology

Given the limits of colonoscopy, can radiographic tests such as computed tomography angiography (CTA) or tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan be helpful? Multiple studies have suggested using CTA as the initial diagnostic test. The advantages of CTAs are:

- Fast, readily available, and does not require a bowel preparation

- If negative, CTAs portend a good prognosis and make it highly unlikely to detect active extravasation on visceral angiography

- If positive, can localize the source of bleed and increase the success of intervention

Whether a positive CTA should be followed with a colonoscopy or visceral angiography remains unclear. Studies show that positive CTAs increase the detection rate of stigmata of recent hemorrhage on colonoscopy. Positive CTAs can also identify a target for embolization by interventional radiology (IR). Though an important caveat is that the success rate of embolization is highest when performed within 90 minutes of a positive CTA. This highlights that if you have IR availability, it is critical to have clear communication, a well-defined protocol, and collaboration among disciplines (i.e., ED, medical team, GI, and IR).

At our institution, we have implemented a CTA-guided protocol for severe LGIB. Those with positive CTAs are referred immediately to IR for embolization. If the embolization is unsuccessful or CTA is negative, the patient will be planned for a non-urgent inpatient colonoscopy. However, our unpublished data and other studies have shown that the overall CTA positivity rates are only between 16-22%. Moreover, one randomized controlled trial comparing CTA versus colonoscopy as an initial test did not show any meaningful difference in clinical outcomes. Thus, the benefit of CTA and the best approach to positive CTAs remains in question.

Lastly, people often ask about the utility of RBC nuclear scans. While they can detect bleeds at a slower rate (as low as 0.1 mL/min) compared to CTA (at least 0.4 mL/min), there are many limitations. RBC scans take time, are not available 24-7, and cannot precisely localize the site of bleeding. Therefore, we rarely recommend them for LGIB.

Approach to Recurrent Diverticular Bleeding

Unfortunately, diverticular bleeding recurs in the hospital 14% of the time and up to 25% at 5 years. When this occurs, is it worthwhile to repeat another colonoscopy or CTA?

Given the lack of clear data, we have adopted a shared decision-making framework with patients. Oftentimes, these patients are older and have significant co-morbidities, and undergoing bowel preparation, anesthesia, and colonoscopy is not trivial. If the patient is stable and prior work-up has excluded pertinent alternative diagnoses other than diverticular bleeding, then we tell patients the chance of finding an intervenable lesion is low and opt for conservative management. Meanwhile, if the patient has persistent, hemodynamically significant bleeding, we recommend a CTA based on the rationale discussed previously.

The most important clinical decision may not be about scoping or obtaining a CTA – it is medication management. If they are taking NSAIDs, they should be discontinued. If antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents were held, they should be restarted promptly in individuals with significant thrombotic risk given studies showing that while rebleeding rates may increase, overall mortality decreases.

In summary, managing LGIB and altering its natural history with either endoscopic or radiographic means is challenging. More studies are needed to guide the optimal approach. Reassuringly, most bleeding self-resolves and patients have good clinical outcomes.

Dr. Lee is a resident physician at New York Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY. Dr. Wan is associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, N.Y. They declare no conflicts of interest.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: An Interventional Radiologist’s Perspective

BY ZEYAD METWALLI, MD, FSIR

When colonoscopy fails to localize and/or stop lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), catheter angiography has been commonly employed as a tool for both diagnosis and treatment of bleeding with embolization. Nuclear medicine or CT imaging studies can serve as useful adjuncts for confirming active bleeding and localizing the site of bleeding prior to angiography, particularly if this information is not provided by colonoscopy. Provocative mesenteric angiography has also become increasingly popular as a troubleshooting technique in patients with initially negative angiography.

Localization of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Radionuclide technetium-99m-lableled red blood cell scintigraphy (RBCS), also known as tagged RBC scintigraphy, has been in use since the early 1980s for investigation of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. RBCS has a high sensitivity for detection of active bleeding with a theoretical ability to detect bleeding at rates as low as 0.04-0.2 mL/minute.

Imaging protocols vary but should include dynamic images, which may aid in localization of bleeding. The relatively long half-life of the tracer used for imaging allows for delayed imaging 12 to 24 hours after injection. This can be useful to confirm active bleeding, particularly when bleeding is intermittent and is not visible on initial images.

With the advent of computed tomography angiography (CTA), which continues to increase in speed, imaging quality and availability, the use of RBCS for evaluation of LGIB has declined. CTA is quicker to perform than RBCS and allows for detection of bleeding as well as accurate anatomic localization, which can guide interventions.

CTA provides a more comprehensive anatomic evaluation, which can aid in the diagnosis of a wide variety of intra-abdominal issues. Conversely, CTA may be less sensitive than RBCS for detection of slower acute bleeding, detecting bleeding at rates of 0.1-1 mL/min. In addition, intermittent bleeding which has temporarily stopped at the time of CTA may evade detection.

Lastly, CTA may not be appropriate in patients with impaired renal function due to risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, particularly in patients with acute kidney injury, which commonly afflicts hospitalized patients with LGIB. Prophylaxis with normal saline hydration should be employed aggressively in patients with impaired renal function, particularly when eGFR is less than 30 mL/minute. Iodinated contrast should be used judiciously in these patients.

In clinical practice, CTA and RBCS have a similar ability to confirm the presence or absence of clinically significant active gastrointestinal bleeding. Given the greater ability to rapidly localize the bleeding site with CTA, this is generally preferred over RBCS unless there is a contraindication to performing CTA, such as severe contrast allergy or high risk for development of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Role of Catheter Angiography and Embolization

Mesenteric angiography is a well-established technique for both detection and treatment of LGIB. Hemodynamic instability and need for packed RBC transfusion increases the likelihood of positive angiography. Limitations include reduced sensitivity for detection of bleeding slower than 0.5-1 mL/minute as well as the intermittent nature of LGIB, which will often resolve spontaneously. Angiography is variably successful in the literature with a diagnostic yield between 40-80%, which encompasses the rate of success in my own practice.

Once bleeding is identified, microcatheter placement within the feeding vessel as close as possible to the site of bleeding is important to ensure treatment efficacy and to limit risk of complications such as non-target embolization and bowel ischemia. Once the feeding vessel is selected with a microcatheter, embolization can be accomplished with a wide variety of tools including metallic coils, liquid embolic agents, and particles. In the treatment of LGIB, liquid embolic agents (e.g., n-butyl cyanoacrylate or NBCA, ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer, etc.) and particles should be used judiciously as distal penetration increases the risk of bowel ischemia and procedure-related morbidity. For this reason, metallic coils are often preferred in the treatment of LGIB.

Although the source of bleeding is variable and may include diverticulosis, recent polypectomy, ulcer, tumor or angiodysplasia, the techniques employed are similar. Accurate and distal microcatheter selection is a key driver for successful embolization and minimizing the risk of bowel ischemia. Small intestinal bleeds can be challenging to treat due to the redundant supply of the arterial arcades supplying small bowel and may require occlusion of several branches to achieve hemostasis. This approach must be balanced with the risk of developing ischemia after embolization. Angiodysplasia, a less frequently encountered culprit of LGIB, may also be managed with selective embolization with many reports of successful treatment with liquid embolic agents such as NBCA mixed with ethiodized oil.

Provocative Mesenteric Angiography for Occult Bleeding

When initial angiography in a patient with suspected active LGIB is negative, provocative angiography can be considered to uncover an intermittent bleed. This may be particularly helpful in a patient where active bleeding is confirmed on a prior diagnostic test.

The approach to provocative mesenteric angiography varies by center, and a variety of agents have been used to provoke bleeding including heparin, vasodilators (i.e., nitroglycerin, verapamil, etc.) and thrombolytics (i.e., tPA), often in combination. Thrombolytics can be administered directly into the territory of interest (i.e., superior mesenteric or inferior mesenteric artery) while heparin may be administered systemically or directly into the catheterized artery. Reported success rates for provoking angiographically visible bleeding vary, but most larger series report a 40-50% success rate. The newly detected bleeding can then be treated with either embolization or surgery. A surgeon should be involved and available when provocative angiography is planned should bleeding fail to be controlled by embolization.

In summary, when colonoscopy fails to identify or control lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), imaging techniques such as RBCS and CTA play a crucial role in localizing active bleeding. While RBCS is highly sensitive, especially for intermittent or slow bleeding, CTA offers faster, more detailed anatomical information and is typically preferred unless contraindicated by renal issues or contrast allergies. Catheter-based mesenteric angiography is a well-established method for both diagnosing and treating LGIB, often using metallic coils to minimize complications like bowel ischemia. In cases where initial angiography is negative, provocative angiography – using agents like heparin or thrombolytics – may help unmask intermittent bleeding, allowing for targeted embolization or surgical intervention.

Dr. Metwalli is associate professor in the Department of Interventional Radiology, Division of Diagnostic Imaging, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas. He declares no conflicts of interest.

Dear colleagues,

: What is the role and optimal timing of colonoscopy? How can we best utilize radiologic studies like CTA or tagged RBC scans? How should we manage patients with recurrent or intermittent bleeding that defies localization?

In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. David Wan, Dr. Fredella Lee, and Dr. Zeyad Metwalli offer their expert insights on these difficult questions. Dr. Wan, drawing on over 15 years of experience as a GI hospitalist, shares – along with his coauthor Dr. Lee – a pragmatic approach to LGIB based on clinical patterns, evolving data, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Dr. Metwalli provides the interventional radiologist’s perspective, highlighting how angiographic techniques can complement GI management and introducing novel IR strategies for patients with recurrent or elusive bleeding.

We hope their perspectives will offer valuable guidance for your practice. Join the conversation on X at @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, and chief of endoscopy at West Haven VA Medical Center, both in Connecticut. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Management of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeds: GI Perspective

BY FREDELLA LEE, MD; DAVID WAN, MD

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) presents unique challenges. Much of this stems from the natural history of diverticular bleeding, the most common etiology of LGIB.

First, while bleeding can be severe, most will spontaneously stop. Second, despite our best efforts with imaging or colonoscopy, finding an intervenable lesion is rare. Third, LGIB has significant rates of rebleeding that are unpredictable.

While serving as a GI hospitalist for 15 years and after managing over 300 cases of LGIB, I often find myself frustrated and colonoscopy feels futile. So how can we rationally approach these patients? We will focus on three clinical questions to develop a framework for LGIB management.

- What is the role and timing for a colonoscopy?

- How do we best utilize radiologic tests?

- How can we prevent recurrent LGIB?

The Role of Colonoscopy

Traditionally, colonoscopy within 24 hours of presentation was recommended. This was based on retrospective cohort data showing higher endoscopic intervention rates and better clinical outcomes. However, this protocol requires patients to drink a significant volume of bowel preparation over a few hours (often requiring an NGT) to achieve clear rectal effluent. Moreover, one needs to mobilize a team (i.e., nurse, technician, anesthesiologist, and gastroenterologist), and find an appropriate location to scope (i.e., ED, ICU, or OR), Understandably, this is challenging, especially overnight. When the therapeutic yield is relatively low, this approach quickly loses enthusiasm.

Importantly, meta-analyses of the randomized controlled trials, have shown that urgent colonoscopies (<24 hours upon presentation), compared to elective colonoscopies (>24 hours upon presentation), do not improve clinical outcomes such as re-bleeding rates, transfusion requirements, mortality, or length of stay. In these studies, the endoscopic intervention rates were 17-34%, however, observational data shows rates of only 8%. In our practice, we will use a clear cap attachment device and water jet irrigation to increase the odds of detecting an active source of bleeding. Colonoscopy has a diagnostic yield of 95% – despite its low therapeutic yield; and while diverticular bleeds constitute up to 64% of cases, one does not want to miss colorectal cancer or other diagnoses. Regardless, there is generally no urgency to perform a colonoscopy. To quote a colleague, Dr. Elizabeth Ross, “there is no such thing as door-to-butt time.”

The Role of Radiology

Given the limits of colonoscopy, can radiographic tests such as computed tomography angiography (CTA) or tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan be helpful? Multiple studies have suggested using CTA as the initial diagnostic test. The advantages of CTAs are:

- Fast, readily available, and does not require a bowel preparation

- If negative, CTAs portend a good prognosis and make it highly unlikely to detect active extravasation on visceral angiography

- If positive, can localize the source of bleed and increase the success of intervention

Whether a positive CTA should be followed with a colonoscopy or visceral angiography remains unclear. Studies show that positive CTAs increase the detection rate of stigmata of recent hemorrhage on colonoscopy. Positive CTAs can also identify a target for embolization by interventional radiology (IR). Though an important caveat is that the success rate of embolization is highest when performed within 90 minutes of a positive CTA. This highlights that if you have IR availability, it is critical to have clear communication, a well-defined protocol, and collaboration among disciplines (i.e., ED, medical team, GI, and IR).

At our institution, we have implemented a CTA-guided protocol for severe LGIB. Those with positive CTAs are referred immediately to IR for embolization. If the embolization is unsuccessful or CTA is negative, the patient will be planned for a non-urgent inpatient colonoscopy. However, our unpublished data and other studies have shown that the overall CTA positivity rates are only between 16-22%. Moreover, one randomized controlled trial comparing CTA versus colonoscopy as an initial test did not show any meaningful difference in clinical outcomes. Thus, the benefit of CTA and the best approach to positive CTAs remains in question.

Lastly, people often ask about the utility of RBC nuclear scans. While they can detect bleeds at a slower rate (as low as 0.1 mL/min) compared to CTA (at least 0.4 mL/min), there are many limitations. RBC scans take time, are not available 24-7, and cannot precisely localize the site of bleeding. Therefore, we rarely recommend them for LGIB.

Approach to Recurrent Diverticular Bleeding

Unfortunately, diverticular bleeding recurs in the hospital 14% of the time and up to 25% at 5 years. When this occurs, is it worthwhile to repeat another colonoscopy or CTA?

Given the lack of clear data, we have adopted a shared decision-making framework with patients. Oftentimes, these patients are older and have significant co-morbidities, and undergoing bowel preparation, anesthesia, and colonoscopy is not trivial. If the patient is stable and prior work-up has excluded pertinent alternative diagnoses other than diverticular bleeding, then we tell patients the chance of finding an intervenable lesion is low and opt for conservative management. Meanwhile, if the patient has persistent, hemodynamically significant bleeding, we recommend a CTA based on the rationale discussed previously.

The most important clinical decision may not be about scoping or obtaining a CTA – it is medication management. If they are taking NSAIDs, they should be discontinued. If antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents were held, they should be restarted promptly in individuals with significant thrombotic risk given studies showing that while rebleeding rates may increase, overall mortality decreases.

In summary, managing LGIB and altering its natural history with either endoscopic or radiographic means is challenging. More studies are needed to guide the optimal approach. Reassuringly, most bleeding self-resolves and patients have good clinical outcomes.

Dr. Lee is a resident physician at New York Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY. Dr. Wan is associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, N.Y. They declare no conflicts of interest.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: An Interventional Radiologist’s Perspective

BY ZEYAD METWALLI, MD, FSIR

When colonoscopy fails to localize and/or stop lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), catheter angiography has been commonly employed as a tool for both diagnosis and treatment of bleeding with embolization. Nuclear medicine or CT imaging studies can serve as useful adjuncts for confirming active bleeding and localizing the site of bleeding prior to angiography, particularly if this information is not provided by colonoscopy. Provocative mesenteric angiography has also become increasingly popular as a troubleshooting technique in patients with initially negative angiography.

Localization of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Radionuclide technetium-99m-lableled red blood cell scintigraphy (RBCS), also known as tagged RBC scintigraphy, has been in use since the early 1980s for investigation of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. RBCS has a high sensitivity for detection of active bleeding with a theoretical ability to detect bleeding at rates as low as 0.04-0.2 mL/minute.

Imaging protocols vary but should include dynamic images, which may aid in localization of bleeding. The relatively long half-life of the tracer used for imaging allows for delayed imaging 12 to 24 hours after injection. This can be useful to confirm active bleeding, particularly when bleeding is intermittent and is not visible on initial images.

With the advent of computed tomography angiography (CTA), which continues to increase in speed, imaging quality and availability, the use of RBCS for evaluation of LGIB has declined. CTA is quicker to perform than RBCS and allows for detection of bleeding as well as accurate anatomic localization, which can guide interventions.

CTA provides a more comprehensive anatomic evaluation, which can aid in the diagnosis of a wide variety of intra-abdominal issues. Conversely, CTA may be less sensitive than RBCS for detection of slower acute bleeding, detecting bleeding at rates of 0.1-1 mL/min. In addition, intermittent bleeding which has temporarily stopped at the time of CTA may evade detection.

Lastly, CTA may not be appropriate in patients with impaired renal function due to risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, particularly in patients with acute kidney injury, which commonly afflicts hospitalized patients with LGIB. Prophylaxis with normal saline hydration should be employed aggressively in patients with impaired renal function, particularly when eGFR is less than 30 mL/minute. Iodinated contrast should be used judiciously in these patients.

In clinical practice, CTA and RBCS have a similar ability to confirm the presence or absence of clinically significant active gastrointestinal bleeding. Given the greater ability to rapidly localize the bleeding site with CTA, this is generally preferred over RBCS unless there is a contraindication to performing CTA, such as severe contrast allergy or high risk for development of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Role of Catheter Angiography and Embolization

Mesenteric angiography is a well-established technique for both detection and treatment of LGIB. Hemodynamic instability and need for packed RBC transfusion increases the likelihood of positive angiography. Limitations include reduced sensitivity for detection of bleeding slower than 0.5-1 mL/minute as well as the intermittent nature of LGIB, which will often resolve spontaneously. Angiography is variably successful in the literature with a diagnostic yield between 40-80%, which encompasses the rate of success in my own practice.

Once bleeding is identified, microcatheter placement within the feeding vessel as close as possible to the site of bleeding is important to ensure treatment efficacy and to limit risk of complications such as non-target embolization and bowel ischemia. Once the feeding vessel is selected with a microcatheter, embolization can be accomplished with a wide variety of tools including metallic coils, liquid embolic agents, and particles. In the treatment of LGIB, liquid embolic agents (e.g., n-butyl cyanoacrylate or NBCA, ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer, etc.) and particles should be used judiciously as distal penetration increases the risk of bowel ischemia and procedure-related morbidity. For this reason, metallic coils are often preferred in the treatment of LGIB.

Although the source of bleeding is variable and may include diverticulosis, recent polypectomy, ulcer, tumor or angiodysplasia, the techniques employed are similar. Accurate and distal microcatheter selection is a key driver for successful embolization and minimizing the risk of bowel ischemia. Small intestinal bleeds can be challenging to treat due to the redundant supply of the arterial arcades supplying small bowel and may require occlusion of several branches to achieve hemostasis. This approach must be balanced with the risk of developing ischemia after embolization. Angiodysplasia, a less frequently encountered culprit of LGIB, may also be managed with selective embolization with many reports of successful treatment with liquid embolic agents such as NBCA mixed with ethiodized oil.

Provocative Mesenteric Angiography for Occult Bleeding

When initial angiography in a patient with suspected active LGIB is negative, provocative angiography can be considered to uncover an intermittent bleed. This may be particularly helpful in a patient where active bleeding is confirmed on a prior diagnostic test.

The approach to provocative mesenteric angiography varies by center, and a variety of agents have been used to provoke bleeding including heparin, vasodilators (i.e., nitroglycerin, verapamil, etc.) and thrombolytics (i.e., tPA), often in combination. Thrombolytics can be administered directly into the territory of interest (i.e., superior mesenteric or inferior mesenteric artery) while heparin may be administered systemically or directly into the catheterized artery. Reported success rates for provoking angiographically visible bleeding vary, but most larger series report a 40-50% success rate. The newly detected bleeding can then be treated with either embolization or surgery. A surgeon should be involved and available when provocative angiography is planned should bleeding fail to be controlled by embolization.

In summary, when colonoscopy fails to identify or control lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), imaging techniques such as RBCS and CTA play a crucial role in localizing active bleeding. While RBCS is highly sensitive, especially for intermittent or slow bleeding, CTA offers faster, more detailed anatomical information and is typically preferred unless contraindicated by renal issues or contrast allergies. Catheter-based mesenteric angiography is a well-established method for both diagnosing and treating LGIB, often using metallic coils to minimize complications like bowel ischemia. In cases where initial angiography is negative, provocative angiography – using agents like heparin or thrombolytics – may help unmask intermittent bleeding, allowing for targeted embolization or surgical intervention.

Dr. Metwalli is associate professor in the Department of Interventional Radiology, Division of Diagnostic Imaging, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas. He declares no conflicts of interest.

Dear colleagues,

: What is the role and optimal timing of colonoscopy? How can we best utilize radiologic studies like CTA or tagged RBC scans? How should we manage patients with recurrent or intermittent bleeding that defies localization?

In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. David Wan, Dr. Fredella Lee, and Dr. Zeyad Metwalli offer their expert insights on these difficult questions. Dr. Wan, drawing on over 15 years of experience as a GI hospitalist, shares – along with his coauthor Dr. Lee – a pragmatic approach to LGIB based on clinical patterns, evolving data, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Dr. Metwalli provides the interventional radiologist’s perspective, highlighting how angiographic techniques can complement GI management and introducing novel IR strategies for patients with recurrent or elusive bleeding.

We hope their perspectives will offer valuable guidance for your practice. Join the conversation on X at @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, and chief of endoscopy at West Haven VA Medical Center, both in Connecticut. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Management of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeds: GI Perspective

BY FREDELLA LEE, MD; DAVID WAN, MD

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) presents unique challenges. Much of this stems from the natural history of diverticular bleeding, the most common etiology of LGIB.

First, while bleeding can be severe, most will spontaneously stop. Second, despite our best efforts with imaging or colonoscopy, finding an intervenable lesion is rare. Third, LGIB has significant rates of rebleeding that are unpredictable.

While serving as a GI hospitalist for 15 years and after managing over 300 cases of LGIB, I often find myself frustrated and colonoscopy feels futile. So how can we rationally approach these patients? We will focus on three clinical questions to develop a framework for LGIB management.

- What is the role and timing for a colonoscopy?

- How do we best utilize radiologic tests?

- How can we prevent recurrent LGIB?

The Role of Colonoscopy

Traditionally, colonoscopy within 24 hours of presentation was recommended. This was based on retrospective cohort data showing higher endoscopic intervention rates and better clinical outcomes. However, this protocol requires patients to drink a significant volume of bowel preparation over a few hours (often requiring an NGT) to achieve clear rectal effluent. Moreover, one needs to mobilize a team (i.e., nurse, technician, anesthesiologist, and gastroenterologist), and find an appropriate location to scope (i.e., ED, ICU, or OR), Understandably, this is challenging, especially overnight. When the therapeutic yield is relatively low, this approach quickly loses enthusiasm.

Importantly, meta-analyses of the randomized controlled trials, have shown that urgent colonoscopies (<24 hours upon presentation), compared to elective colonoscopies (>24 hours upon presentation), do not improve clinical outcomes such as re-bleeding rates, transfusion requirements, mortality, or length of stay. In these studies, the endoscopic intervention rates were 17-34%, however, observational data shows rates of only 8%. In our practice, we will use a clear cap attachment device and water jet irrigation to increase the odds of detecting an active source of bleeding. Colonoscopy has a diagnostic yield of 95% – despite its low therapeutic yield; and while diverticular bleeds constitute up to 64% of cases, one does not want to miss colorectal cancer or other diagnoses. Regardless, there is generally no urgency to perform a colonoscopy. To quote a colleague, Dr. Elizabeth Ross, “there is no such thing as door-to-butt time.”

The Role of Radiology

Given the limits of colonoscopy, can radiographic tests such as computed tomography angiography (CTA) or tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan be helpful? Multiple studies have suggested using CTA as the initial diagnostic test. The advantages of CTAs are:

- Fast, readily available, and does not require a bowel preparation

- If negative, CTAs portend a good prognosis and make it highly unlikely to detect active extravasation on visceral angiography

- If positive, can localize the source of bleed and increase the success of intervention

Whether a positive CTA should be followed with a colonoscopy or visceral angiography remains unclear. Studies show that positive CTAs increase the detection rate of stigmata of recent hemorrhage on colonoscopy. Positive CTAs can also identify a target for embolization by interventional radiology (IR). Though an important caveat is that the success rate of embolization is highest when performed within 90 minutes of a positive CTA. This highlights that if you have IR availability, it is critical to have clear communication, a well-defined protocol, and collaboration among disciplines (i.e., ED, medical team, GI, and IR).

At our institution, we have implemented a CTA-guided protocol for severe LGIB. Those with positive CTAs are referred immediately to IR for embolization. If the embolization is unsuccessful or CTA is negative, the patient will be planned for a non-urgent inpatient colonoscopy. However, our unpublished data and other studies have shown that the overall CTA positivity rates are only between 16-22%. Moreover, one randomized controlled trial comparing CTA versus colonoscopy as an initial test did not show any meaningful difference in clinical outcomes. Thus, the benefit of CTA and the best approach to positive CTAs remains in question.

Lastly, people often ask about the utility of RBC nuclear scans. While they can detect bleeds at a slower rate (as low as 0.1 mL/min) compared to CTA (at least 0.4 mL/min), there are many limitations. RBC scans take time, are not available 24-7, and cannot precisely localize the site of bleeding. Therefore, we rarely recommend them for LGIB.

Approach to Recurrent Diverticular Bleeding

Unfortunately, diverticular bleeding recurs in the hospital 14% of the time and up to 25% at 5 years. When this occurs, is it worthwhile to repeat another colonoscopy or CTA?

Given the lack of clear data, we have adopted a shared decision-making framework with patients. Oftentimes, these patients are older and have significant co-morbidities, and undergoing bowel preparation, anesthesia, and colonoscopy is not trivial. If the patient is stable and prior work-up has excluded pertinent alternative diagnoses other than diverticular bleeding, then we tell patients the chance of finding an intervenable lesion is low and opt for conservative management. Meanwhile, if the patient has persistent, hemodynamically significant bleeding, we recommend a CTA based on the rationale discussed previously.

The most important clinical decision may not be about scoping or obtaining a CTA – it is medication management. If they are taking NSAIDs, they should be discontinued. If antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents were held, they should be restarted promptly in individuals with significant thrombotic risk given studies showing that while rebleeding rates may increase, overall mortality decreases.

In summary, managing LGIB and altering its natural history with either endoscopic or radiographic means is challenging. More studies are needed to guide the optimal approach. Reassuringly, most bleeding self-resolves and patients have good clinical outcomes.

Dr. Lee is a resident physician at New York Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY. Dr. Wan is associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, N.Y. They declare no conflicts of interest.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: An Interventional Radiologist’s Perspective

BY ZEYAD METWALLI, MD, FSIR

When colonoscopy fails to localize and/or stop lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), catheter angiography has been commonly employed as a tool for both diagnosis and treatment of bleeding with embolization. Nuclear medicine or CT imaging studies can serve as useful adjuncts for confirming active bleeding and localizing the site of bleeding prior to angiography, particularly if this information is not provided by colonoscopy. Provocative mesenteric angiography has also become increasingly popular as a troubleshooting technique in patients with initially negative angiography.

Localization of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Radionuclide technetium-99m-lableled red blood cell scintigraphy (RBCS), also known as tagged RBC scintigraphy, has been in use since the early 1980s for investigation of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. RBCS has a high sensitivity for detection of active bleeding with a theoretical ability to detect bleeding at rates as low as 0.04-0.2 mL/minute.

Imaging protocols vary but should include dynamic images, which may aid in localization of bleeding. The relatively long half-life of the tracer used for imaging allows for delayed imaging 12 to 24 hours after injection. This can be useful to confirm active bleeding, particularly when bleeding is intermittent and is not visible on initial images.

With the advent of computed tomography angiography (CTA), which continues to increase in speed, imaging quality and availability, the use of RBCS for evaluation of LGIB has declined. CTA is quicker to perform than RBCS and allows for detection of bleeding as well as accurate anatomic localization, which can guide interventions.

CTA provides a more comprehensive anatomic evaluation, which can aid in the diagnosis of a wide variety of intra-abdominal issues. Conversely, CTA may be less sensitive than RBCS for detection of slower acute bleeding, detecting bleeding at rates of 0.1-1 mL/min. In addition, intermittent bleeding which has temporarily stopped at the time of CTA may evade detection.

Lastly, CTA may not be appropriate in patients with impaired renal function due to risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, particularly in patients with acute kidney injury, which commonly afflicts hospitalized patients with LGIB. Prophylaxis with normal saline hydration should be employed aggressively in patients with impaired renal function, particularly when eGFR is less than 30 mL/minute. Iodinated contrast should be used judiciously in these patients.

In clinical practice, CTA and RBCS have a similar ability to confirm the presence or absence of clinically significant active gastrointestinal bleeding. Given the greater ability to rapidly localize the bleeding site with CTA, this is generally preferred over RBCS unless there is a contraindication to performing CTA, such as severe contrast allergy or high risk for development of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Role of Catheter Angiography and Embolization

Mesenteric angiography is a well-established technique for both detection and treatment of LGIB. Hemodynamic instability and need for packed RBC transfusion increases the likelihood of positive angiography. Limitations include reduced sensitivity for detection of bleeding slower than 0.5-1 mL/minute as well as the intermittent nature of LGIB, which will often resolve spontaneously. Angiography is variably successful in the literature with a diagnostic yield between 40-80%, which encompasses the rate of success in my own practice.

Once bleeding is identified, microcatheter placement within the feeding vessel as close as possible to the site of bleeding is important to ensure treatment efficacy and to limit risk of complications such as non-target embolization and bowel ischemia. Once the feeding vessel is selected with a microcatheter, embolization can be accomplished with a wide variety of tools including metallic coils, liquid embolic agents, and particles. In the treatment of LGIB, liquid embolic agents (e.g., n-butyl cyanoacrylate or NBCA, ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer, etc.) and particles should be used judiciously as distal penetration increases the risk of bowel ischemia and procedure-related morbidity. For this reason, metallic coils are often preferred in the treatment of LGIB.

Although the source of bleeding is variable and may include diverticulosis, recent polypectomy, ulcer, tumor or angiodysplasia, the techniques employed are similar. Accurate and distal microcatheter selection is a key driver for successful embolization and minimizing the risk of bowel ischemia. Small intestinal bleeds can be challenging to treat due to the redundant supply of the arterial arcades supplying small bowel and may require occlusion of several branches to achieve hemostasis. This approach must be balanced with the risk of developing ischemia after embolization. Angiodysplasia, a less frequently encountered culprit of LGIB, may also be managed with selective embolization with many reports of successful treatment with liquid embolic agents such as NBCA mixed with ethiodized oil.

Provocative Mesenteric Angiography for Occult Bleeding

When initial angiography in a patient with suspected active LGIB is negative, provocative angiography can be considered to uncover an intermittent bleed. This may be particularly helpful in a patient where active bleeding is confirmed on a prior diagnostic test.

The approach to provocative mesenteric angiography varies by center, and a variety of agents have been used to provoke bleeding including heparin, vasodilators (i.e., nitroglycerin, verapamil, etc.) and thrombolytics (i.e., tPA), often in combination. Thrombolytics can be administered directly into the territory of interest (i.e., superior mesenteric or inferior mesenteric artery) while heparin may be administered systemically or directly into the catheterized artery. Reported success rates for provoking angiographically visible bleeding vary, but most larger series report a 40-50% success rate. The newly detected bleeding can then be treated with either embolization or surgery. A surgeon should be involved and available when provocative angiography is planned should bleeding fail to be controlled by embolization.

In summary, when colonoscopy fails to identify or control lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), imaging techniques such as RBCS and CTA play a crucial role in localizing active bleeding. While RBCS is highly sensitive, especially for intermittent or slow bleeding, CTA offers faster, more detailed anatomical information and is typically preferred unless contraindicated by renal issues or contrast allergies. Catheter-based mesenteric angiography is a well-established method for both diagnosing and treating LGIB, often using metallic coils to minimize complications like bowel ischemia. In cases where initial angiography is negative, provocative angiography – using agents like heparin or thrombolytics – may help unmask intermittent bleeding, allowing for targeted embolization or surgical intervention.

Dr. Metwalli is associate professor in the Department of Interventional Radiology, Division of Diagnostic Imaging, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas. He declares no conflicts of interest.

Improving Care for Patients from Historically Minoritized and Marginalized Communities with Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

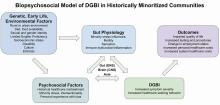

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

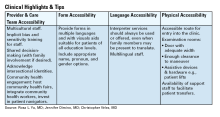

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.