User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Moderate alcohol intake may curb subsequent diabetes after gestational diabetes

Among women with a history of gestational diabetes, alcohol intake of half a drink to one drink daily was associated with a 55% lower risk for subsequent type 2 diabetes, based on data from approximately 4,700 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort.

However, the findings must be considered in the context of other risks and benefits of alcohol consumption before making statements or clinical recommendations, wrote Stefanie N. Hinkle, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues.

Women with a history of gestational diabetes remain at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes, so modifiable diet and lifestyle factors deserve further study, the researchers noted. Previous research has shown an association between light to moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes among women in the general population, but data on a similar risk reduction for women with a history of gestational diabetes are lacking, they added.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 4,740 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II who reported a history of gestational diabetes. These women were followed from Jan. 1, 1991, to Dec. 31, 2017, as part of the Diabetes & Women’s Health Study; dietary intake, including alcohol intake, was assessed every 4 years via validated food frequency questionnaires.

The average age at baseline was 38 years, and the median follow-up time was 24 years, yielding a total of 78,328 person-years of follow-up. Alcohol consumption was divided into four categories: none; 0.1 g/day to 4.9 g/day; 5.0 to 14.9 g/day, and 15.0 g/day or higher.

A total of 897 incident cases of type 2 diabetes were reported during the study period. After adjustment for multiple dietary and lifestyle variables, including diet and physical activity, only alcohol consumption of 5.0-14.9 g/day (approximately half a drink to one drink) was associated with a significantly decreased risk for incident type 2 diabetes (hazard ratio, 0.45) compared with women who reported no alcohol consumption.

On further adjustment for body mass index, women who reported alcohol consumption in the 5.0-14.9 g/day range had a 41% lower risk for developing incident type 2 diabetes (HR, 0.59); alcohol consumption in the other ranges remained unassociated with type 2 diabetes risk, although the researchers noted that these estimates were attenuated.

The median daily intake for women who consumed alcohol was 2.3 g/day, approximately one drink per week. Beer was the most frequently consumed type of alcohol.

When the researchers analyzed the data by alcohol type, notably, “only beer consumption of 1 or more servings a week was associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes,” although previous studies have suggested a stronger association in diabetes risk reduction with wine consumption vs. beer, the researchers noted.

The study findings were the potential for confounding factors not included in the adjustment, potential underreporting of alcohol intake, and potential screening bias toward women who were more health conscious, the researchers noted. Other limitations were lack of generalizability given that most of the study participants were white women, and a lack of data on binge drinking and whether alcohol was consumed with meals, they added. The study strengths included the prospective design, large size, long-term follow-up, and use of validated questionnaires, they said.

The researchers cautioned that the results should not be interpreted without considering other health outcomes. “Consistent with the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which recommend that adults who do not consume alcohol do not initiate drinking, it may not be prudent for those with a history of gestational diabetes who do not consume alcohol to initiate drinking alcohol solely to reduce their risk for type 2 diabetes,” they emphasized.

Risk/benefit ratio for alcohol includes many factors

“There is a relative paucity of data regarding women’s long-term health as it may relate to pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes,” Angela Bianco, MD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Bianco said she was surprised by some of the study findings.

“Generally speaking, I consider alcohol to be of little to no nutritional value, and to have a high sugar content/glycemic index,” she said. “However, a reduced incidence of adult-onset diabetes has been observed among moderate drinkers in other large prospective studies as well,” she noted. “In contrast, some studies have shown an increased risk of diabetes among a proportion of subjects in the top alcohol consumption category, while other studies have found no association. Possible inconsistencies may be due to differences in drinking patterns and the types of beverages consumed,” Dr. Bianco explained.

A key point for clinicians to keep in mind is that “the study may be flawed based on the different criteria used to make a diagnosis of history of gestational diabetes, the fact that they excluded patients that did not return the questionnaires, and the fact that respondents may not have answered correctly due to recall bias” or other reasons, Dr. Bianco said. “Additionally, those who responded obviously had access to health care, which in and of itself is a confounder,” she noted.

Another key point is that “the effect of alcohol being consumed with or without a meal was not examined,” said Dr. Bianco. “Alcohol concentration is reduced if consumed with meals. Alcohol can lead to hypoglycemia (from reduced gluconeogenesis) during fasting states, but after meals (postprandial states) it can result in lower glucose disposal and higher blood glucose levels,” she said. “The available literature suggests that alcohol may improve insulin sensitivity and reduce resistance, but there is likely a U-shaped association between alcohol consumption and the risk of diabetes,” Dr. Bianco noted. “There is likely a delicate balance between benefits and risks of alcohol intake. The inherent benefit/risk ratio must take into account with other potential comorbidities including BMI, activity level, stress, and preexisting conditions,” she said.

“Additional long-term studies engaging patients with diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds with detailed information regarding the role of nutrition, alcohol intake, tobacco and drug use, environmental exposures, and medical comorbidities need to be performed,” Dr. Bianco concluded.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the Nurses’ Health Study II was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Lead author Dr. Hinkle and coauthor Cuilin Zhang, MD, are employees of the U.S. federal government. The researchers and Dr. Bianco had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Among women with a history of gestational diabetes, alcohol intake of half a drink to one drink daily was associated with a 55% lower risk for subsequent type 2 diabetes, based on data from approximately 4,700 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort.

However, the findings must be considered in the context of other risks and benefits of alcohol consumption before making statements or clinical recommendations, wrote Stefanie N. Hinkle, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues.

Women with a history of gestational diabetes remain at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes, so modifiable diet and lifestyle factors deserve further study, the researchers noted. Previous research has shown an association between light to moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes among women in the general population, but data on a similar risk reduction for women with a history of gestational diabetes are lacking, they added.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 4,740 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II who reported a history of gestational diabetes. These women were followed from Jan. 1, 1991, to Dec. 31, 2017, as part of the Diabetes & Women’s Health Study; dietary intake, including alcohol intake, was assessed every 4 years via validated food frequency questionnaires.

The average age at baseline was 38 years, and the median follow-up time was 24 years, yielding a total of 78,328 person-years of follow-up. Alcohol consumption was divided into four categories: none; 0.1 g/day to 4.9 g/day; 5.0 to 14.9 g/day, and 15.0 g/day or higher.

A total of 897 incident cases of type 2 diabetes were reported during the study period. After adjustment for multiple dietary and lifestyle variables, including diet and physical activity, only alcohol consumption of 5.0-14.9 g/day (approximately half a drink to one drink) was associated with a significantly decreased risk for incident type 2 diabetes (hazard ratio, 0.45) compared with women who reported no alcohol consumption.

On further adjustment for body mass index, women who reported alcohol consumption in the 5.0-14.9 g/day range had a 41% lower risk for developing incident type 2 diabetes (HR, 0.59); alcohol consumption in the other ranges remained unassociated with type 2 diabetes risk, although the researchers noted that these estimates were attenuated.

The median daily intake for women who consumed alcohol was 2.3 g/day, approximately one drink per week. Beer was the most frequently consumed type of alcohol.

When the researchers analyzed the data by alcohol type, notably, “only beer consumption of 1 or more servings a week was associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes,” although previous studies have suggested a stronger association in diabetes risk reduction with wine consumption vs. beer, the researchers noted.

The study findings were the potential for confounding factors not included in the adjustment, potential underreporting of alcohol intake, and potential screening bias toward women who were more health conscious, the researchers noted. Other limitations were lack of generalizability given that most of the study participants were white women, and a lack of data on binge drinking and whether alcohol was consumed with meals, they added. The study strengths included the prospective design, large size, long-term follow-up, and use of validated questionnaires, they said.

The researchers cautioned that the results should not be interpreted without considering other health outcomes. “Consistent with the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which recommend that adults who do not consume alcohol do not initiate drinking, it may not be prudent for those with a history of gestational diabetes who do not consume alcohol to initiate drinking alcohol solely to reduce their risk for type 2 diabetes,” they emphasized.

Risk/benefit ratio for alcohol includes many factors

“There is a relative paucity of data regarding women’s long-term health as it may relate to pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes,” Angela Bianco, MD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Bianco said she was surprised by some of the study findings.

“Generally speaking, I consider alcohol to be of little to no nutritional value, and to have a high sugar content/glycemic index,” she said. “However, a reduced incidence of adult-onset diabetes has been observed among moderate drinkers in other large prospective studies as well,” she noted. “In contrast, some studies have shown an increased risk of diabetes among a proportion of subjects in the top alcohol consumption category, while other studies have found no association. Possible inconsistencies may be due to differences in drinking patterns and the types of beverages consumed,” Dr. Bianco explained.

A key point for clinicians to keep in mind is that “the study may be flawed based on the different criteria used to make a diagnosis of history of gestational diabetes, the fact that they excluded patients that did not return the questionnaires, and the fact that respondents may not have answered correctly due to recall bias” or other reasons, Dr. Bianco said. “Additionally, those who responded obviously had access to health care, which in and of itself is a confounder,” she noted.

Another key point is that “the effect of alcohol being consumed with or without a meal was not examined,” said Dr. Bianco. “Alcohol concentration is reduced if consumed with meals. Alcohol can lead to hypoglycemia (from reduced gluconeogenesis) during fasting states, but after meals (postprandial states) it can result in lower glucose disposal and higher blood glucose levels,” she said. “The available literature suggests that alcohol may improve insulin sensitivity and reduce resistance, but there is likely a U-shaped association between alcohol consumption and the risk of diabetes,” Dr. Bianco noted. “There is likely a delicate balance between benefits and risks of alcohol intake. The inherent benefit/risk ratio must take into account with other potential comorbidities including BMI, activity level, stress, and preexisting conditions,” she said.

“Additional long-term studies engaging patients with diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds with detailed information regarding the role of nutrition, alcohol intake, tobacco and drug use, environmental exposures, and medical comorbidities need to be performed,” Dr. Bianco concluded.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the Nurses’ Health Study II was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Lead author Dr. Hinkle and coauthor Cuilin Zhang, MD, are employees of the U.S. federal government. The researchers and Dr. Bianco had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Among women with a history of gestational diabetes, alcohol intake of half a drink to one drink daily was associated with a 55% lower risk for subsequent type 2 diabetes, based on data from approximately 4,700 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort.

However, the findings must be considered in the context of other risks and benefits of alcohol consumption before making statements or clinical recommendations, wrote Stefanie N. Hinkle, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues.

Women with a history of gestational diabetes remain at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes, so modifiable diet and lifestyle factors deserve further study, the researchers noted. Previous research has shown an association between light to moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes among women in the general population, but data on a similar risk reduction for women with a history of gestational diabetes are lacking, they added.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 4,740 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II who reported a history of gestational diabetes. These women were followed from Jan. 1, 1991, to Dec. 31, 2017, as part of the Diabetes & Women’s Health Study; dietary intake, including alcohol intake, was assessed every 4 years via validated food frequency questionnaires.

The average age at baseline was 38 years, and the median follow-up time was 24 years, yielding a total of 78,328 person-years of follow-up. Alcohol consumption was divided into four categories: none; 0.1 g/day to 4.9 g/day; 5.0 to 14.9 g/day, and 15.0 g/day or higher.

A total of 897 incident cases of type 2 diabetes were reported during the study period. After adjustment for multiple dietary and lifestyle variables, including diet and physical activity, only alcohol consumption of 5.0-14.9 g/day (approximately half a drink to one drink) was associated with a significantly decreased risk for incident type 2 diabetes (hazard ratio, 0.45) compared with women who reported no alcohol consumption.

On further adjustment for body mass index, women who reported alcohol consumption in the 5.0-14.9 g/day range had a 41% lower risk for developing incident type 2 diabetes (HR, 0.59); alcohol consumption in the other ranges remained unassociated with type 2 diabetes risk, although the researchers noted that these estimates were attenuated.

The median daily intake for women who consumed alcohol was 2.3 g/day, approximately one drink per week. Beer was the most frequently consumed type of alcohol.

When the researchers analyzed the data by alcohol type, notably, “only beer consumption of 1 or more servings a week was associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes,” although previous studies have suggested a stronger association in diabetes risk reduction with wine consumption vs. beer, the researchers noted.

The study findings were the potential for confounding factors not included in the adjustment, potential underreporting of alcohol intake, and potential screening bias toward women who were more health conscious, the researchers noted. Other limitations were lack of generalizability given that most of the study participants were white women, and a lack of data on binge drinking and whether alcohol was consumed with meals, they added. The study strengths included the prospective design, large size, long-term follow-up, and use of validated questionnaires, they said.

The researchers cautioned that the results should not be interpreted without considering other health outcomes. “Consistent with the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which recommend that adults who do not consume alcohol do not initiate drinking, it may not be prudent for those with a history of gestational diabetes who do not consume alcohol to initiate drinking alcohol solely to reduce their risk for type 2 diabetes,” they emphasized.

Risk/benefit ratio for alcohol includes many factors

“There is a relative paucity of data regarding women’s long-term health as it may relate to pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes,” Angela Bianco, MD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Bianco said she was surprised by some of the study findings.

“Generally speaking, I consider alcohol to be of little to no nutritional value, and to have a high sugar content/glycemic index,” she said. “However, a reduced incidence of adult-onset diabetes has been observed among moderate drinkers in other large prospective studies as well,” she noted. “In contrast, some studies have shown an increased risk of diabetes among a proportion of subjects in the top alcohol consumption category, while other studies have found no association. Possible inconsistencies may be due to differences in drinking patterns and the types of beverages consumed,” Dr. Bianco explained.

A key point for clinicians to keep in mind is that “the study may be flawed based on the different criteria used to make a diagnosis of history of gestational diabetes, the fact that they excluded patients that did not return the questionnaires, and the fact that respondents may not have answered correctly due to recall bias” or other reasons, Dr. Bianco said. “Additionally, those who responded obviously had access to health care, which in and of itself is a confounder,” she noted.

Another key point is that “the effect of alcohol being consumed with or without a meal was not examined,” said Dr. Bianco. “Alcohol concentration is reduced if consumed with meals. Alcohol can lead to hypoglycemia (from reduced gluconeogenesis) during fasting states, but after meals (postprandial states) it can result in lower glucose disposal and higher blood glucose levels,” she said. “The available literature suggests that alcohol may improve insulin sensitivity and reduce resistance, but there is likely a U-shaped association between alcohol consumption and the risk of diabetes,” Dr. Bianco noted. “There is likely a delicate balance between benefits and risks of alcohol intake. The inherent benefit/risk ratio must take into account with other potential comorbidities including BMI, activity level, stress, and preexisting conditions,” she said.

“Additional long-term studies engaging patients with diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds with detailed information regarding the role of nutrition, alcohol intake, tobacco and drug use, environmental exposures, and medical comorbidities need to be performed,” Dr. Bianco concluded.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the Nurses’ Health Study II was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Lead author Dr. Hinkle and coauthor Cuilin Zhang, MD, are employees of the U.S. federal government. The researchers and Dr. Bianco had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

COVID-19 claims more than 675,000 U.S. lives, surpassing the 1918 flu

, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University.

Although the raw numbers match, epidemiologists point out that 675,000 deaths in 1918 was a much greater proportion of the population. In 1918, the U.S. population was 105 million, less than one third of what it is today.

The AIDS pandemic of the 1980s remains the deadliest of the 20th Century, claiming the lives of 700,000 Americans. But at our current pace of 2,000 COVID deaths a day, we could quickly eclipse that death toll, too.

Even though the 1918 epidemic is often called the “Spanish Flu,” there is no universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Still, the almost incomprehensible loss harkens back to a time when medicine and technology were far less advanced than they are today.

In 1918, the United States didn’t have access to a vaccine, or near real-time tools to trace the spread and communicate the threat.

In some ways, the United States has failed to learn from the mistakes of the past.

There are many similarities between the two pandemics. In the spring of 1918, when the first wave of influenza hit, the United States and its allies were nearing victory in Europe in World War I. Just this summer the United States has ended its longest war, the conflict in Afghanistan, as COVID cases surge.

In both pandemics, hospitals and funeral homes were overrun and makeshift clinics were opened where space was available. Mask mandates were installed; schools, churches, and theaters closed; and social distancing was encouraged.

As is the case today, different jurisdictions took different steps to fight the pandemic and some were more successful than others.

According to History.com, in 1918, Philadelphia’s mayor said a popular annual parade could be held, and an estimated 200,000 people attended. In less than 2 weeks, more than 1,000 local residents were dead. But in St. Louis, public gatherings were banned, schools and theaters closed, and the death toll there was one eighth of Philadelphia’s.

Just as in 1918, America has at times continued to fan the flames of the epidemic by relaxing restrictions too quickly and relying on unproven treatments. Poor communication allowed younger people to feel that they wouldn’t necessarily face the worst consequences of the virus, contributing to a false sense of security in the age group that was fueling the spread.

“A lot of the mistakes that we definitely fell into in 1918, we hoped we wouldn’t fall into in 2020,” epidemiologist Stephen Kissler, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told CNN. “We did.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University.

Although the raw numbers match, epidemiologists point out that 675,000 deaths in 1918 was a much greater proportion of the population. In 1918, the U.S. population was 105 million, less than one third of what it is today.

The AIDS pandemic of the 1980s remains the deadliest of the 20th Century, claiming the lives of 700,000 Americans. But at our current pace of 2,000 COVID deaths a day, we could quickly eclipse that death toll, too.

Even though the 1918 epidemic is often called the “Spanish Flu,” there is no universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Still, the almost incomprehensible loss harkens back to a time when medicine and technology were far less advanced than they are today.

In 1918, the United States didn’t have access to a vaccine, or near real-time tools to trace the spread and communicate the threat.

In some ways, the United States has failed to learn from the mistakes of the past.

There are many similarities between the two pandemics. In the spring of 1918, when the first wave of influenza hit, the United States and its allies were nearing victory in Europe in World War I. Just this summer the United States has ended its longest war, the conflict in Afghanistan, as COVID cases surge.

In both pandemics, hospitals and funeral homes were overrun and makeshift clinics were opened where space was available. Mask mandates were installed; schools, churches, and theaters closed; and social distancing was encouraged.

As is the case today, different jurisdictions took different steps to fight the pandemic and some were more successful than others.

According to History.com, in 1918, Philadelphia’s mayor said a popular annual parade could be held, and an estimated 200,000 people attended. In less than 2 weeks, more than 1,000 local residents were dead. But in St. Louis, public gatherings were banned, schools and theaters closed, and the death toll there was one eighth of Philadelphia’s.

Just as in 1918, America has at times continued to fan the flames of the epidemic by relaxing restrictions too quickly and relying on unproven treatments. Poor communication allowed younger people to feel that they wouldn’t necessarily face the worst consequences of the virus, contributing to a false sense of security in the age group that was fueling the spread.

“A lot of the mistakes that we definitely fell into in 1918, we hoped we wouldn’t fall into in 2020,” epidemiologist Stephen Kissler, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told CNN. “We did.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University.

Although the raw numbers match, epidemiologists point out that 675,000 deaths in 1918 was a much greater proportion of the population. In 1918, the U.S. population was 105 million, less than one third of what it is today.

The AIDS pandemic of the 1980s remains the deadliest of the 20th Century, claiming the lives of 700,000 Americans. But at our current pace of 2,000 COVID deaths a day, we could quickly eclipse that death toll, too.

Even though the 1918 epidemic is often called the “Spanish Flu,” there is no universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Still, the almost incomprehensible loss harkens back to a time when medicine and technology were far less advanced than they are today.

In 1918, the United States didn’t have access to a vaccine, or near real-time tools to trace the spread and communicate the threat.

In some ways, the United States has failed to learn from the mistakes of the past.

There are many similarities between the two pandemics. In the spring of 1918, when the first wave of influenza hit, the United States and its allies were nearing victory in Europe in World War I. Just this summer the United States has ended its longest war, the conflict in Afghanistan, as COVID cases surge.

In both pandemics, hospitals and funeral homes were overrun and makeshift clinics were opened where space was available. Mask mandates were installed; schools, churches, and theaters closed; and social distancing was encouraged.

As is the case today, different jurisdictions took different steps to fight the pandemic and some were more successful than others.

According to History.com, in 1918, Philadelphia’s mayor said a popular annual parade could be held, and an estimated 200,000 people attended. In less than 2 weeks, more than 1,000 local residents were dead. But in St. Louis, public gatherings were banned, schools and theaters closed, and the death toll there was one eighth of Philadelphia’s.

Just as in 1918, America has at times continued to fan the flames of the epidemic by relaxing restrictions too quickly and relying on unproven treatments. Poor communication allowed younger people to feel that they wouldn’t necessarily face the worst consequences of the virus, contributing to a false sense of security in the age group that was fueling the spread.

“A lot of the mistakes that we definitely fell into in 1918, we hoped we wouldn’t fall into in 2020,” epidemiologist Stephen Kissler, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told CNN. “We did.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescent immunizations and protecting our children from COVID-19

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

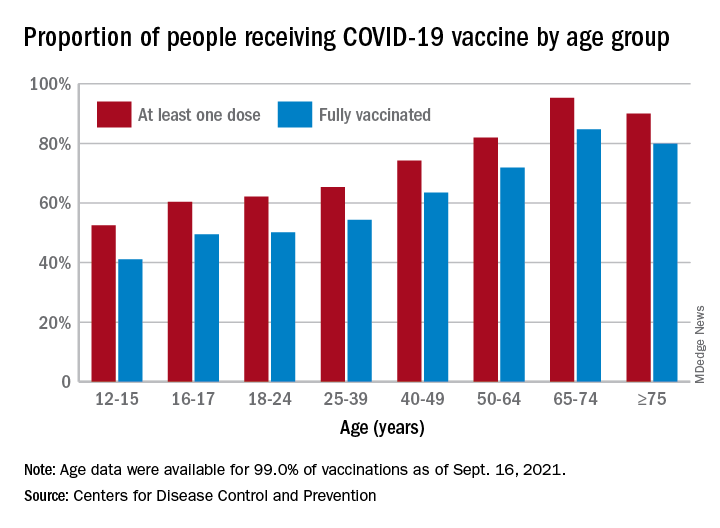

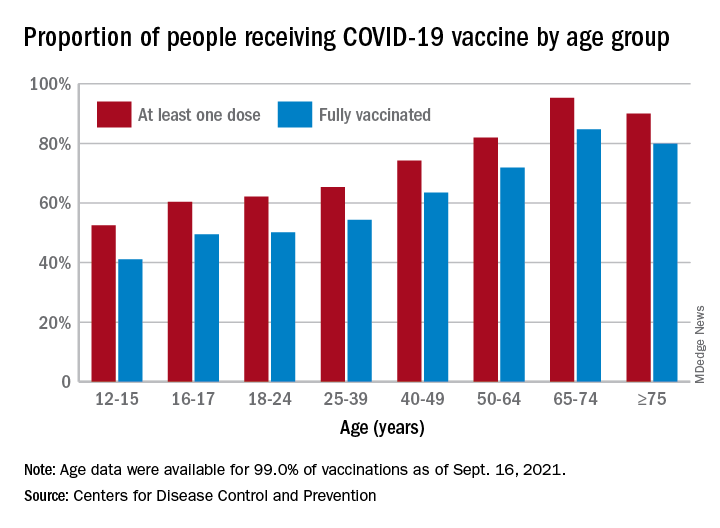

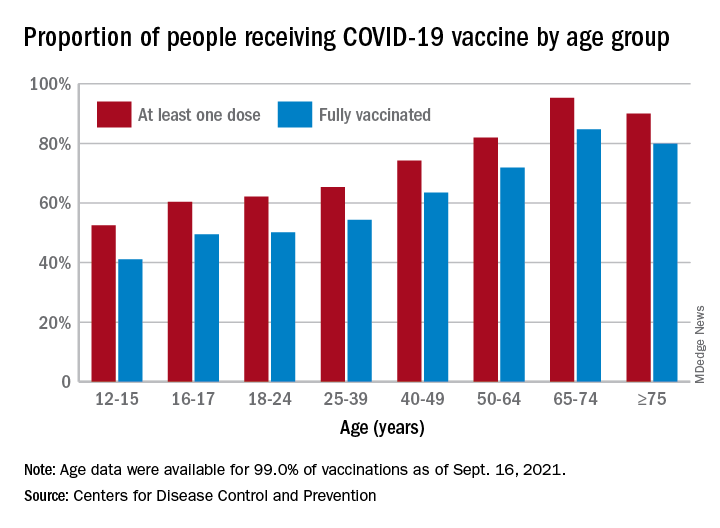

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

EMPEROR-Preserved: Empagliflozin’s HFpEF efficacy catalyzes a heart failure redefinition

Groundbreaking results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial did more than establish for the first time that a drug, empagliflozin, has clearly proven efficacy for treating patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The results also helped catalyze a paradigm shift in how heart failure thought leaders think about the role of ejection fraction for making important distinctions among patients with heart failure.

EMPEROR-Preserved may also be the final nail in the coffin for defining patients with heart failure as having HFpEF or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

This new consensus essentially throws out left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) as the key metric for matching patients to heart failure treatments. Experts have instead begun suggesting a more unified treatment approach for all heart failure patients regardless of their EF.

‘Forget about ejection fraction’

“We encourage you to forget about ejection fraction,” declared Milton Packer, MD, during discussion at a session of the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America. “We certainly encourage you to forget about an ejection fraction of less than 40%” as having special significance,” added Dr. Packer, a lead investigator for both the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials (which researchers combined in a unified analysis with a total of 9,718 patients with heart failure called EMPEROR-Pooled), and a heart failure researcher at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

“The 40% ejection fraction divide is artificial. It was created in 2003 as part of a trial design, but it has no physiological significance,” Dr. Packer explained. A much better way to distinguish systolic and diastolic heart failure is by strain assessment rather than by ejection fraction. “Strain is a measure of myocardial shortening, a measure of what the heart does. Ejection fraction is a measure of volume,” said Dr. Packer. “Sign me up to get rid of ejection fraction,” he added.

“Ejection fraction is not as valuable as we thought for distinguishing the therapeutic benefit” of heart failure drugs, agreed Marvin A. Konstam, MD, professor of medicine at Tufts University and chief physician executive of the CardioVascular Center of Tufts Medical Center, both in Boston, who spoke during a different session at the meeting.

“It would easier if we didn’t spend time parsing this number,” ejection fraction, commented Clyde W. Yancy, MD, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Wouldn’t it be easier if we said that every patient with heart failure needs to receive one agent from each of the four [pillar] drug classes, and put them in a polypill” at reduced dosages, he proposed, envisioning one potential consequence of jettisoning ejection fraction.

The four pillar drug classes, recently identified as essential for patients with HFrEF but until now not endorsed for patients with HFpEF, are the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, such as empagliflozin (Jardiance); an angiotensin receptor blocker neprilysin inhibitor compound such as sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto); beta-blockers; and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone and eplerenone.

An opportunity for ‘simpler and easier’ treatments

“This is an opportunity to disrupt the way we’ve been doing things and think about something that is simpler and easier,” said Dr. Yancy, who chaired some of the panels serially formed by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology to write guidelines for treating heart failure. “An approach that would be easier to implement without worrying about staggering the start of each drug class and an incessant focus on titrating individual elements and taking 6 months to get to a certain place.”

Results from EMPEROR-Preserved and the combined EMPEROR-Pooled analysis triggered these paradigm-shifting sentiments by showing clear evidence that treatment with empagliflozin exerts consistent benefit – and is consistently safe – for patients with heart failure across a spectrum of EFs, from less than 25% to 64%, though its performance in patients with HFpEF and EFs of 65% or greater in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial remains unclear.

The consequence is that clinicians should feel comfortable prescribing empagliflozin to most patients with heart failure without regard to EF, even patients with EF values in the mid-60% range.

The EMPEROR-Preserved results showed a clear signal of attenuated benefit among patients with an EF of 65% or greater “on a population basis,” stressed Dr. Packer. “But on an individual basis, ejection fraction is not that reproducible, so measuring ejection fraction will not help you determine whom to treat or not treat. “

“There is significant variability” measuring EF using the most common modality, echocardiography, noted Javed Butler, MD, an EMPEROR coinvestigator who also spoke at the meeting session. A person with a measured EF of 65% could actually have a value that may be as low as 58% or as high as about 72%, noted Dr. Butler, who is professor and chair of medicine at the University of Mississippi, Jackson. The upshot is that any patient diagnosed with heart failure should receive an SGLT2 inhibitor “irrespective of their ejection fraction,” Dr. Butler advised.

“Ejection fraction is very crude, and probably not sufficient to identify a phenotype,” for treatment, said Dr. Yancy. “The real takeaway may be that we need to revisit what we call HFrEF, and then let that be the new standard for treatment.”

“Is [an EF of] 60% the new 40%?” asked Dr. Packer, implying that the answer was yes.

Results from several trials suggest redefining HFrEF

The idea that patients without traditionally defined HFrEF – an EF of 40% or less – could also benefit from other classes of heart failure drugs has been gestating for a while, and then rose to a new level with the August 2021 report of results from EMPEROR-Preserved. Two years ago, in September 2019, Dr. Butler, Dr. Packer, and a third colleague advanced the notion of redefining HFrEF by raising the ejection fraction ceiling in a published commentary.

They cited the experience with the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan in a post hoc analysis of data collected in the CHARM-Preserved trial, which showed a strong signal of benefit in the subgroup of patients with EFs of 41%-49%, but not in those with an EF of 50% or higher. This finding prompted Dr. Konstam to express doubts about relying on EF to define heart failure subgroups in trials and guide management in a commentary published more than 3 years ago.

Another crack in the traditional EF framework came from analysis of results from the TOPCAT trial that tested spironolactone as a treatment for patients with HFpEF, according to the 2019 opinion published by Dr. Butler and Dr. Packer. Once again a post hoc analysis, this time using data from TOPCAT, suggested a benefit from the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone in patients with heart failure and an EF of 45%-49% (45% was the minimum EF for enrollment into the study).

Recently, data from a third trial that tested sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFpEF, PARAGON-HF, showed benefit among patients with EFs below the study median of 57%. This finding led the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021 to amend its initial approval for sacubitril/valsartan by removing a specific EF ceiling from the drug’s indication and instead saying that patient’s receiving the drug should have a “below normal” EF.

Writing in a recent commentary, Dr. Yancy called the FDA’s action on sacubitril/valsartan “reasonable,” and that the subgroup assessment of data from the PARAGON-HF trial creates a “new, reasonably evidence-based therapy for HFpEF.” He also predicted that guideline-writing panels will “likely align with a permissive statement of indication” for sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFpEF, especially those with EFs of less than 57%.

The idea of using an SGLT2 inhibitor like empagliflozin on all heart failure patients, and also adding agents like sacubitril/valsartan and spironolactone in patients with HFpEF and EFs in the mid-50% range or lower may take some time to catch on, but it already has one influential advocate.

“If a patient has HFpEF with an EF of less than 55%, use quadruple-class therapy,” summed up Dr. Butler during the HFSA session, while also suggesting prescribing an SGLT2 inhibitor to essentially all patients with heart failure regardless of their EF.

The EMPEROR-Preserved and EMPEROR-Reduced trials and the EMPEROR-Pooled analysis were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Packer has had financial relationships with BI and Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Konstam has served on data monitoring committees for trials funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Amgen, Luitpold, and Pfizer, and has been a consultant to Arena, LivaNova, Merck, SC Pharma, and Takeda. Dr. Yancy had no disclosures. Dr. Butler has had financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and numerous other companies.

Groundbreaking results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial did more than establish for the first time that a drug, empagliflozin, has clearly proven efficacy for treating patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The results also helped catalyze a paradigm shift in how heart failure thought leaders think about the role of ejection fraction for making important distinctions among patients with heart failure.

EMPEROR-Preserved may also be the final nail in the coffin for defining patients with heart failure as having HFpEF or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

This new consensus essentially throws out left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) as the key metric for matching patients to heart failure treatments. Experts have instead begun suggesting a more unified treatment approach for all heart failure patients regardless of their EF.

‘Forget about ejection fraction’

“We encourage you to forget about ejection fraction,” declared Milton Packer, MD, during discussion at a session of the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America. “We certainly encourage you to forget about an ejection fraction of less than 40%” as having special significance,” added Dr. Packer, a lead investigator for both the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials (which researchers combined in a unified analysis with a total of 9,718 patients with heart failure called EMPEROR-Pooled), and a heart failure researcher at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

“The 40% ejection fraction divide is artificial. It was created in 2003 as part of a trial design, but it has no physiological significance,” Dr. Packer explained. A much better way to distinguish systolic and diastolic heart failure is by strain assessment rather than by ejection fraction. “Strain is a measure of myocardial shortening, a measure of what the heart does. Ejection fraction is a measure of volume,” said Dr. Packer. “Sign me up to get rid of ejection fraction,” he added.

“Ejection fraction is not as valuable as we thought for distinguishing the therapeutic benefit” of heart failure drugs, agreed Marvin A. Konstam, MD, professor of medicine at Tufts University and chief physician executive of the CardioVascular Center of Tufts Medical Center, both in Boston, who spoke during a different session at the meeting.

“It would easier if we didn’t spend time parsing this number,” ejection fraction, commented Clyde W. Yancy, MD, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Wouldn’t it be easier if we said that every patient with heart failure needs to receive one agent from each of the four [pillar] drug classes, and put them in a polypill” at reduced dosages, he proposed, envisioning one potential consequence of jettisoning ejection fraction.

The four pillar drug classes, recently identified as essential for patients with HFrEF but until now not endorsed for patients with HFpEF, are the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, such as empagliflozin (Jardiance); an angiotensin receptor blocker neprilysin inhibitor compound such as sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto); beta-blockers; and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone and eplerenone.

An opportunity for ‘simpler and easier’ treatments

“This is an opportunity to disrupt the way we’ve been doing things and think about something that is simpler and easier,” said Dr. Yancy, who chaired some of the panels serially formed by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology to write guidelines for treating heart failure. “An approach that would be easier to implement without worrying about staggering the start of each drug class and an incessant focus on titrating individual elements and taking 6 months to get to a certain place.”

Results from EMPEROR-Preserved and the combined EMPEROR-Pooled analysis triggered these paradigm-shifting sentiments by showing clear evidence that treatment with empagliflozin exerts consistent benefit – and is consistently safe – for patients with heart failure across a spectrum of EFs, from less than 25% to 64%, though its performance in patients with HFpEF and EFs of 65% or greater in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial remains unclear.

The consequence is that clinicians should feel comfortable prescribing empagliflozin to most patients with heart failure without regard to EF, even patients with EF values in the mid-60% range.

The EMPEROR-Preserved results showed a clear signal of attenuated benefit among patients with an EF of 65% or greater “on a population basis,” stressed Dr. Packer. “But on an individual basis, ejection fraction is not that reproducible, so measuring ejection fraction will not help you determine whom to treat or not treat. “

“There is significant variability” measuring EF using the most common modality, echocardiography, noted Javed Butler, MD, an EMPEROR coinvestigator who also spoke at the meeting session. A person with a measured EF of 65% could actually have a value that may be as low as 58% or as high as about 72%, noted Dr. Butler, who is professor and chair of medicine at the University of Mississippi, Jackson. The upshot is that any patient diagnosed with heart failure should receive an SGLT2 inhibitor “irrespective of their ejection fraction,” Dr. Butler advised.

“Ejection fraction is very crude, and probably not sufficient to identify a phenotype,” for treatment, said Dr. Yancy. “The real takeaway may be that we need to revisit what we call HFrEF, and then let that be the new standard for treatment.”

“Is [an EF of] 60% the new 40%?” asked Dr. Packer, implying that the answer was yes.

Results from several trials suggest redefining HFrEF

The idea that patients without traditionally defined HFrEF – an EF of 40% or less – could also benefit from other classes of heart failure drugs has been gestating for a while, and then rose to a new level with the August 2021 report of results from EMPEROR-Preserved. Two years ago, in September 2019, Dr. Butler, Dr. Packer, and a third colleague advanced the notion of redefining HFrEF by raising the ejection fraction ceiling in a published commentary.

They cited the experience with the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan in a post hoc analysis of data collected in the CHARM-Preserved trial, which showed a strong signal of benefit in the subgroup of patients with EFs of 41%-49%, but not in those with an EF of 50% or higher. This finding prompted Dr. Konstam to express doubts about relying on EF to define heart failure subgroups in trials and guide management in a commentary published more than 3 years ago.

Another crack in the traditional EF framework came from analysis of results from the TOPCAT trial that tested spironolactone as a treatment for patients with HFpEF, according to the 2019 opinion published by Dr. Butler and Dr. Packer. Once again a post hoc analysis, this time using data from TOPCAT, suggested a benefit from the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone in patients with heart failure and an EF of 45%-49% (45% was the minimum EF for enrollment into the study).

Recently, data from a third trial that tested sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFpEF, PARAGON-HF, showed benefit among patients with EFs below the study median of 57%. This finding led the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021 to amend its initial approval for sacubitril/valsartan by removing a specific EF ceiling from the drug’s indication and instead saying that patient’s receiving the drug should have a “below normal” EF.

Writing in a recent commentary, Dr. Yancy called the FDA’s action on sacubitril/valsartan “reasonable,” and that the subgroup assessment of data from the PARAGON-HF trial creates a “new, reasonably evidence-based therapy for HFpEF.” He also predicted that guideline-writing panels will “likely align with a permissive statement of indication” for sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFpEF, especially those with EFs of less than 57%.

The idea of using an SGLT2 inhibitor like empagliflozin on all heart failure patients, and also adding agents like sacubitril/valsartan and spironolactone in patients with HFpEF and EFs in the mid-50% range or lower may take some time to catch on, but it already has one influential advocate.

“If a patient has HFpEF with an EF of less than 55%, use quadruple-class therapy,” summed up Dr. Butler during the HFSA session, while also suggesting prescribing an SGLT2 inhibitor to essentially all patients with heart failure regardless of their EF.

The EMPEROR-Preserved and EMPEROR-Reduced trials and the EMPEROR-Pooled analysis were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Packer has had financial relationships with BI and Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Konstam has served on data monitoring committees for trials funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Amgen, Luitpold, and Pfizer, and has been a consultant to Arena, LivaNova, Merck, SC Pharma, and Takeda. Dr. Yancy had no disclosures. Dr. Butler has had financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and numerous other companies.

Groundbreaking results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial did more than establish for the first time that a drug, empagliflozin, has clearly proven efficacy for treating patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The results also helped catalyze a paradigm shift in how heart failure thought leaders think about the role of ejection fraction for making important distinctions among patients with heart failure.

EMPEROR-Preserved may also be the final nail in the coffin for defining patients with heart failure as having HFpEF or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

This new consensus essentially throws out left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) as the key metric for matching patients to heart failure treatments. Experts have instead begun suggesting a more unified treatment approach for all heart failure patients regardless of their EF.

‘Forget about ejection fraction’

“We encourage you to forget about ejection fraction,” declared Milton Packer, MD, during discussion at a session of the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America. “We certainly encourage you to forget about an ejection fraction of less than 40%” as having special significance,” added Dr. Packer, a lead investigator for both the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials (which researchers combined in a unified analysis with a total of 9,718 patients with heart failure called EMPEROR-Pooled), and a heart failure researcher at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

“The 40% ejection fraction divide is artificial. It was created in 2003 as part of a trial design, but it has no physiological significance,” Dr. Packer explained. A much better way to distinguish systolic and diastolic heart failure is by strain assessment rather than by ejection fraction. “Strain is a measure of myocardial shortening, a measure of what the heart does. Ejection fraction is a measure of volume,” said Dr. Packer. “Sign me up to get rid of ejection fraction,” he added.

“Ejection fraction is not as valuable as we thought for distinguishing the therapeutic benefit” of heart failure drugs, agreed Marvin A. Konstam, MD, professor of medicine at Tufts University and chief physician executive of the CardioVascular Center of Tufts Medical Center, both in Boston, who spoke during a different session at the meeting.

“It would easier if we didn’t spend time parsing this number,” ejection fraction, commented Clyde W. Yancy, MD, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Wouldn’t it be easier if we said that every patient with heart failure needs to receive one agent from each of the four [pillar] drug classes, and put them in a polypill” at reduced dosages, he proposed, envisioning one potential consequence of jettisoning ejection fraction.

The four pillar drug classes, recently identified as essential for patients with HFrEF but until now not endorsed for patients with HFpEF, are the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, such as empagliflozin (Jardiance); an angiotensin receptor blocker neprilysin inhibitor compound such as sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto); beta-blockers; and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone and eplerenone.

An opportunity for ‘simpler and easier’ treatments

“This is an opportunity to disrupt the way we’ve been doing things and think about something that is simpler and easier,” said Dr. Yancy, who chaired some of the panels serially formed by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology to write guidelines for treating heart failure. “An approach that would be easier to implement without worrying about staggering the start of each drug class and an incessant focus on titrating individual elements and taking 6 months to get to a certain place.”

Results from EMPEROR-Preserved and the combined EMPEROR-Pooled analysis triggered these paradigm-shifting sentiments by showing clear evidence that treatment with empagliflozin exerts consistent benefit – and is consistently safe – for patients with heart failure across a spectrum of EFs, from less than 25% to 64%, though its performance in patients with HFpEF and EFs of 65% or greater in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial remains unclear.

The consequence is that clinicians should feel comfortable prescribing empagliflozin to most patients with heart failure without regard to EF, even patients with EF values in the mid-60% range.

The EMPEROR-Preserved results showed a clear signal of attenuated benefit among patients with an EF of 65% or greater “on a population basis,” stressed Dr. Packer. “But on an individual basis, ejection fraction is not that reproducible, so measuring ejection fraction will not help you determine whom to treat or not treat. “

“There is significant variability” measuring EF using the most common modality, echocardiography, noted Javed Butler, MD, an EMPEROR coinvestigator who also spoke at the meeting session. A person with a measured EF of 65% could actually have a value that may be as low as 58% or as high as about 72%, noted Dr. Butler, who is professor and chair of medicine at the University of Mississippi, Jackson. The upshot is that any patient diagnosed with heart failure should receive an SGLT2 inhibitor “irrespective of their ejection fraction,” Dr. Butler advised.

“Ejection fraction is very crude, and probably not sufficient to identify a phenotype,” for treatment, said Dr. Yancy. “The real takeaway may be that we need to revisit what we call HFrEF, and then let that be the new standard for treatment.”

“Is [an EF of] 60% the new 40%?” asked Dr. Packer, implying that the answer was yes.

Results from several trials suggest redefining HFrEF

The idea that patients without traditionally defined HFrEF – an EF of 40% or less – could also benefit from other classes of heart failure drugs has been gestating for a while, and then rose to a new level with the August 2021 report of results from EMPEROR-Preserved. Two years ago, in September 2019, Dr. Butler, Dr. Packer, and a third colleague advanced the notion of redefining HFrEF by raising the ejection fraction ceiling in a published commentary.

They cited the experience with the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan in a post hoc analysis of data collected in the CHARM-Preserved trial, which showed a strong signal of benefit in the subgroup of patients with EFs of 41%-49%, but not in those with an EF of 50% or higher. This finding prompted Dr. Konstam to express doubts about relying on EF to define heart failure subgroups in trials and guide management in a commentary published more than 3 years ago.

Another crack in the traditional EF framework came from analysis of results from the TOPCAT trial that tested spironolactone as a treatment for patients with HFpEF, according to the 2019 opinion published by Dr. Butler and Dr. Packer. Once again a post hoc analysis, this time using data from TOPCAT, suggested a benefit from the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone in patients with heart failure and an EF of 45%-49% (45% was the minimum EF for enrollment into the study).

Recently, data from a third trial that tested sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFpEF, PARAGON-HF, showed benefit among patients with EFs below the study median of 57%. This finding led the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021 to amend its initial approval for sacubitril/valsartan by removing a specific EF ceiling from the drug’s indication and instead saying that patient’s receiving the drug should have a “below normal” EF.

Writing in a recent commentary, Dr. Yancy called the FDA’s action on sacubitril/valsartan “reasonable,” and that the subgroup assessment of data from the PARAGON-HF trial creates a “new, reasonably evidence-based therapy for HFpEF.” He also predicted that guideline-writing panels will “likely align with a permissive statement of indication” for sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFpEF, especially those with EFs of less than 57%.

The idea of using an SGLT2 inhibitor like empagliflozin on all heart failure patients, and also adding agents like sacubitril/valsartan and spironolactone in patients with HFpEF and EFs in the mid-50% range or lower may take some time to catch on, but it already has one influential advocate.

“If a patient has HFpEF with an EF of less than 55%, use quadruple-class therapy,” summed up Dr. Butler during the HFSA session, while also suggesting prescribing an SGLT2 inhibitor to essentially all patients with heart failure regardless of their EF.

The EMPEROR-Preserved and EMPEROR-Reduced trials and the EMPEROR-Pooled analysis were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Packer has had financial relationships with BI and Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Konstam has served on data monitoring committees for trials funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Amgen, Luitpold, and Pfizer, and has been a consultant to Arena, LivaNova, Merck, SC Pharma, and Takeda. Dr. Yancy had no disclosures. Dr. Butler has had financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and numerous other companies.

FROM HFSA 2021

A new weight loss threshold for T2d remission after bariatric surgery?

Patients with type 2 diabetes who underwent bariatric surgery commonly experienced remission, but there was little increase in rates of remission above a threshold of 20% total weight loss (TWL), according to a retrospective analysis of 5,928 patients with diabetes in an integrated health care system in Southern California.

The findings should reassure physicians and patients that surgery will be beneficial, according to lead author Karen Coleman, PhD, professor of health systems science at Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Dr. Coleman has heard from many physicians saying they recommend against bariatric surgery because of concerns that patients gain weight back and therefore won’t get a long-term benefit, but this is not supported by the literature. “Hundreds of articles at this point show that this simply is not true. In addition, providers seem to think about bariatric surgery as an ‘all or none’ treatment. Gaining any weight back means that patients ‘fail.’ Weight regain is a normal part of massive weight loss; however, maintaining a certain amount of weight loss still provides benefits for patients, especially those with cardiovascular conditions like diabetes,” said Dr. Coleman.