User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

A Systematic Review of Dermatologic Findings in Adults With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

A Systematic Review of Dermatologic Findings in Adults With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening immunologic phenomenon characterized by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome—like clinical picture with additional features, including hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, and increased natural killer cell activity. Clinical manifestations of HLH often are nonspecific, making HLH diagnosis challenging. High persistent fever is a key feature of HLH; patients also may report gastrointestinal distress, lethargy, and/or widespread rash.1

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is believed to stem from inherited defects in several genes, such as perforin (PRF1), as well as immune dysregulation due to infections, rheumatologic diseases, hematologic malignancies, or drug reactions.2 The primary mechanism of HLH is hypothesized to be driven by aberrant immune activation, interferon gamma released from CD8+ T cells, and uncontrolled phagocytosis by activated macrophages. The cytokine cascade results in tissue injury and multiorgan dysfunction.3,4

Although HLH historically has been categorized as primary (familial) or secondary (acquired), the most recent guidelines suggest the etiology is not always binary.3,5 That said, the concept of secondary causes is useful in understanding risk factors for developing HLH. Both forms of the disease are thought to be elicited by a trigger (eg, infection), even when inherited genetic mutations exist.6 The primary form commonly affects the pediatric population,4,6-8 whereas the secondary form is more common in adults.7

Several sets of diagnostic criteria for HLH have been developed, the most well-known being the HLH-2004 criteria.1,3 The HLH-2009 modified criteria were developed after further evidence provided a refined sense of how the HLH-2004 criteria should be stratified.9 Finally, Fardet et al10 presented the HScore as an estimation of likelihood of diagnosis of HLH. These sets of HLH criteria include clinical and laboratory features that demonstrate inflammation, natrual killer cell activity, hemophagocytosis, end-organ damage, and cell lineage effects. The HScore differs from the other sets of HLH criteria in that it is designed to estimate an individual patient’s risk of having reactive hemophagocytic syndrome, which likely is equivalent to secondary HLH, although the authors do not use this exact terminology.10

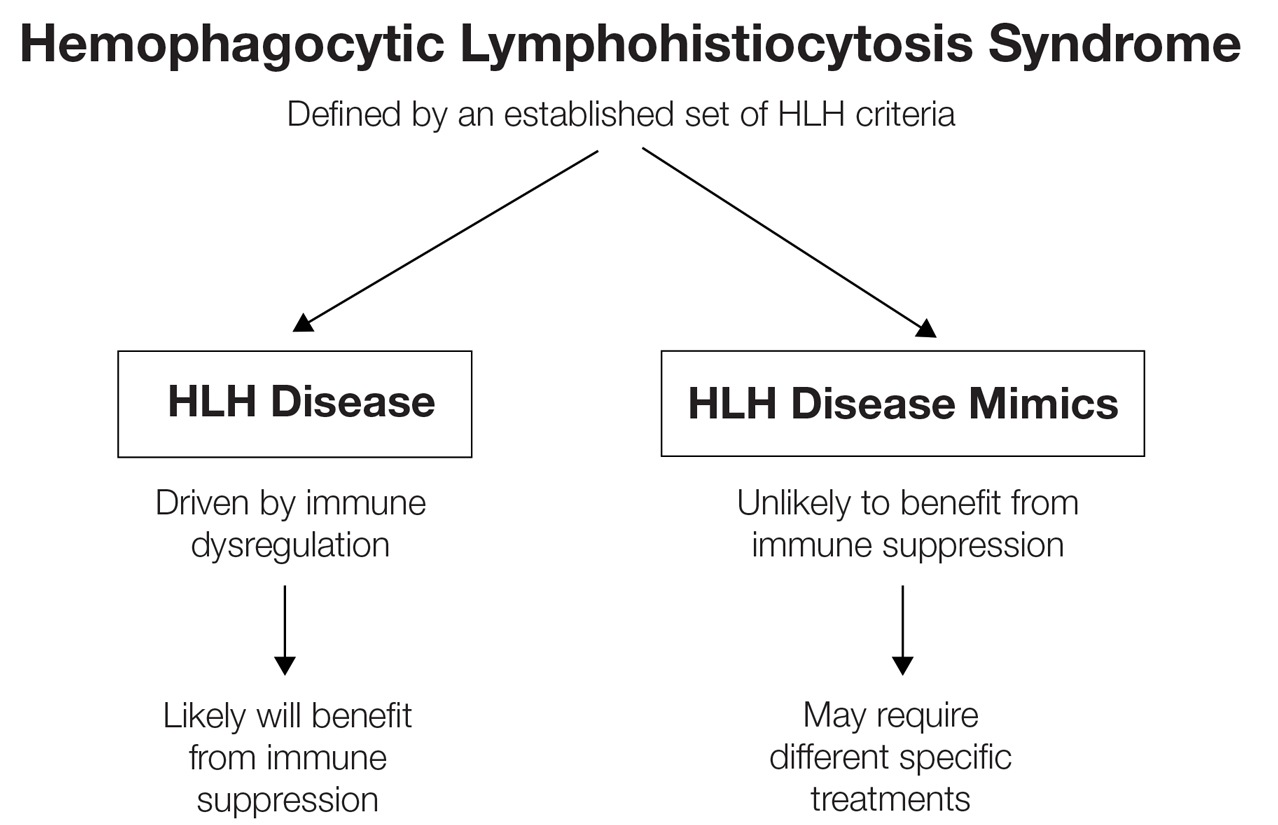

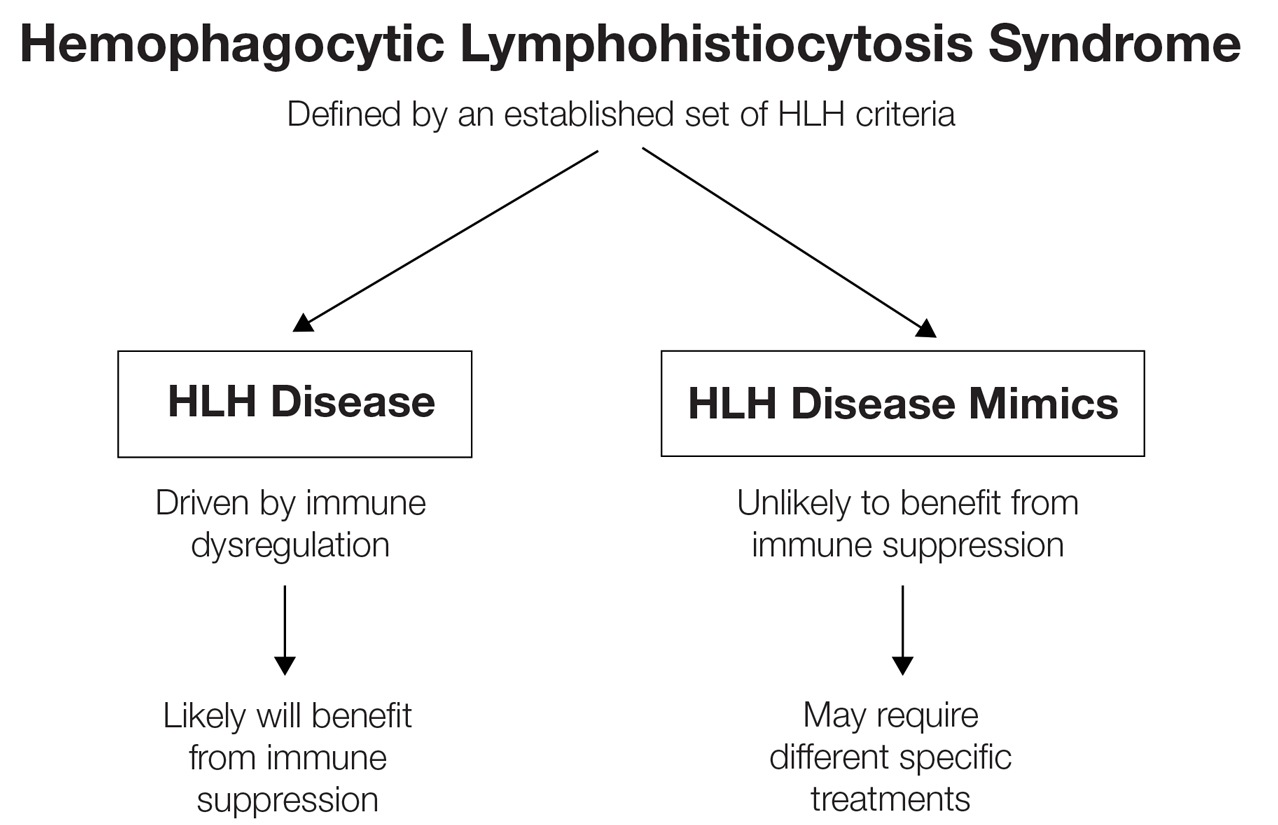

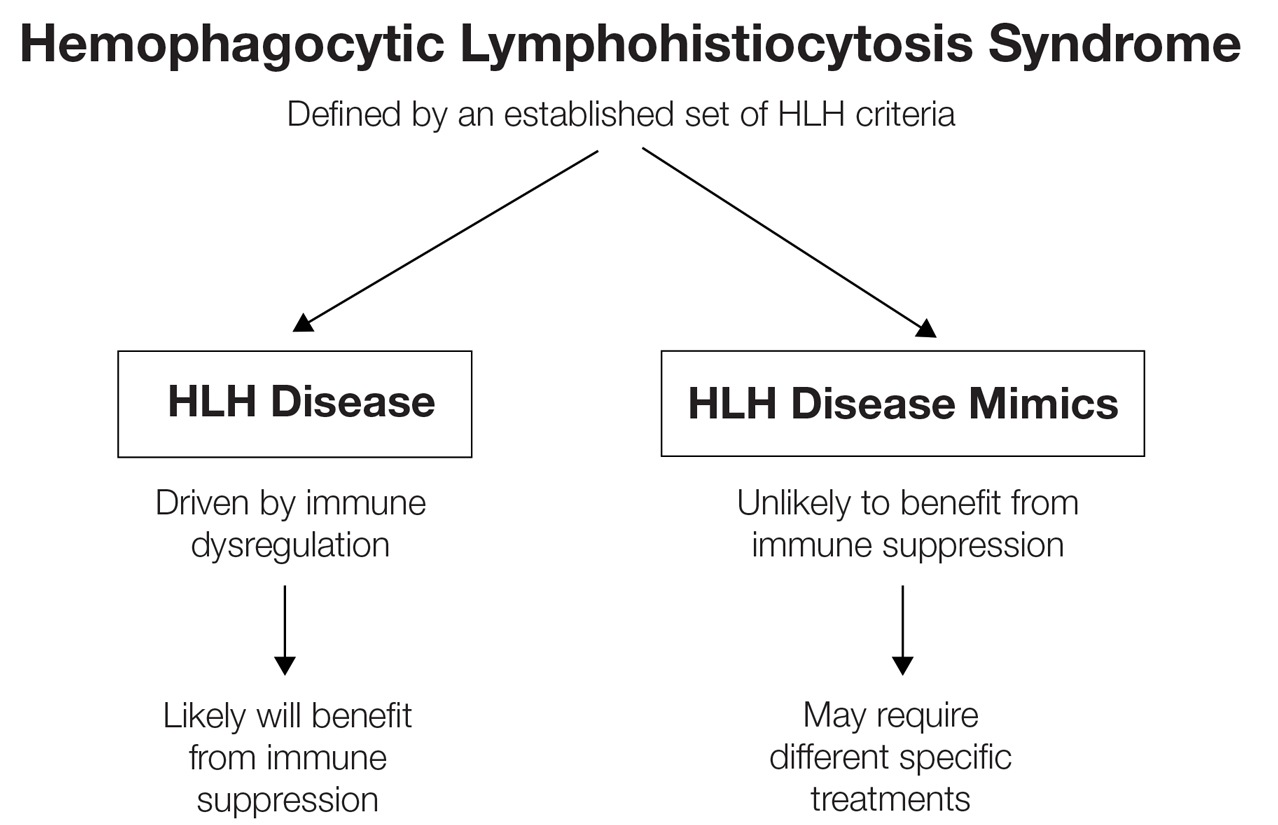

While these criteria provide a framework for diagnosing HLH, they may fail to distinguish between HLH disease and HLH disease mimics, a concept described by the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis that may impact the success of immunosuppressive treatment.3 Individuals with HLH syndrome meet the aforementioned diagnostic criteria; HLH syndrome is further divided into HLH disease and HLH disease mimics (Figure 1). The “disease” label describes the traditional concept of HLH, driven by aberrant immune overactivation, in which patients benefit from immunosuppression. In contrast, HLH mimics include a subset of patients who meet the HLH criteria but are unlikely to benefit from immunosuppression because the primary mechanism driving their condition is not owed to immune overactivation, as is the case with HLH disease. Examples of HLH mimics include certain infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), that may demonstrate clinical findings consistent with HLH but would not benefit from immunosuppression. Ironically, infections (including EBV) also are known triggers of HLH disease, making this concept difficult to understand and adopt. In this study, we refer to HLH disease simply as HLH.

Although cutaneous manifestations of HLH are not included in the diagnostic criteria, skin findings are common and may coincide with the severity and progression of the disease.11 Despite the fact that HLH can manifest with rash,1 comprehensive reviews of reported cutaneous findings in adult HLH are lacking. Thus, the goal of this study was to provide an organized characterization of reported cutaneous findings in adults with HLH and context for how the dermatologic examination may support the diagnosis or uncover the underlying etiology of this condition.

Methods

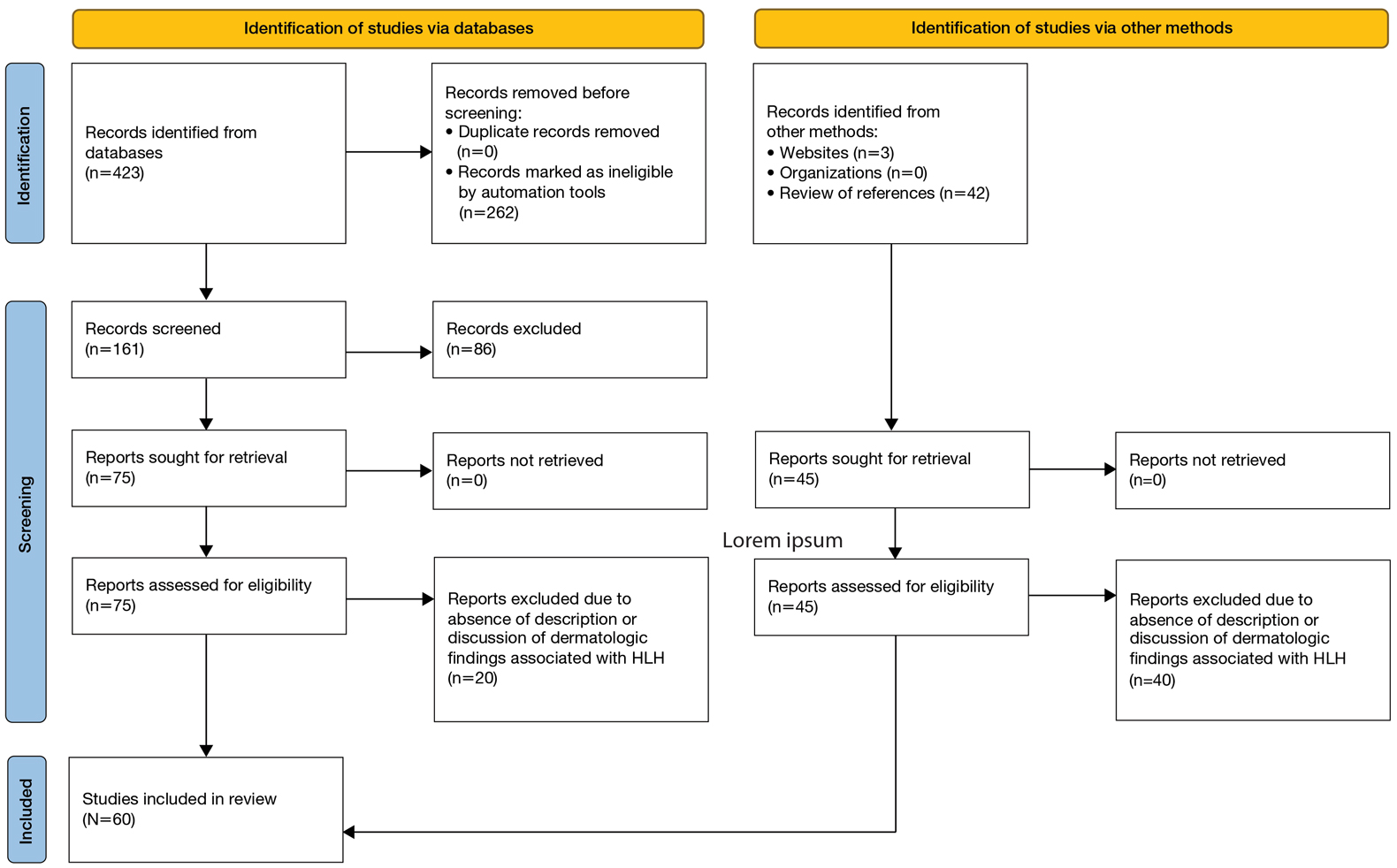

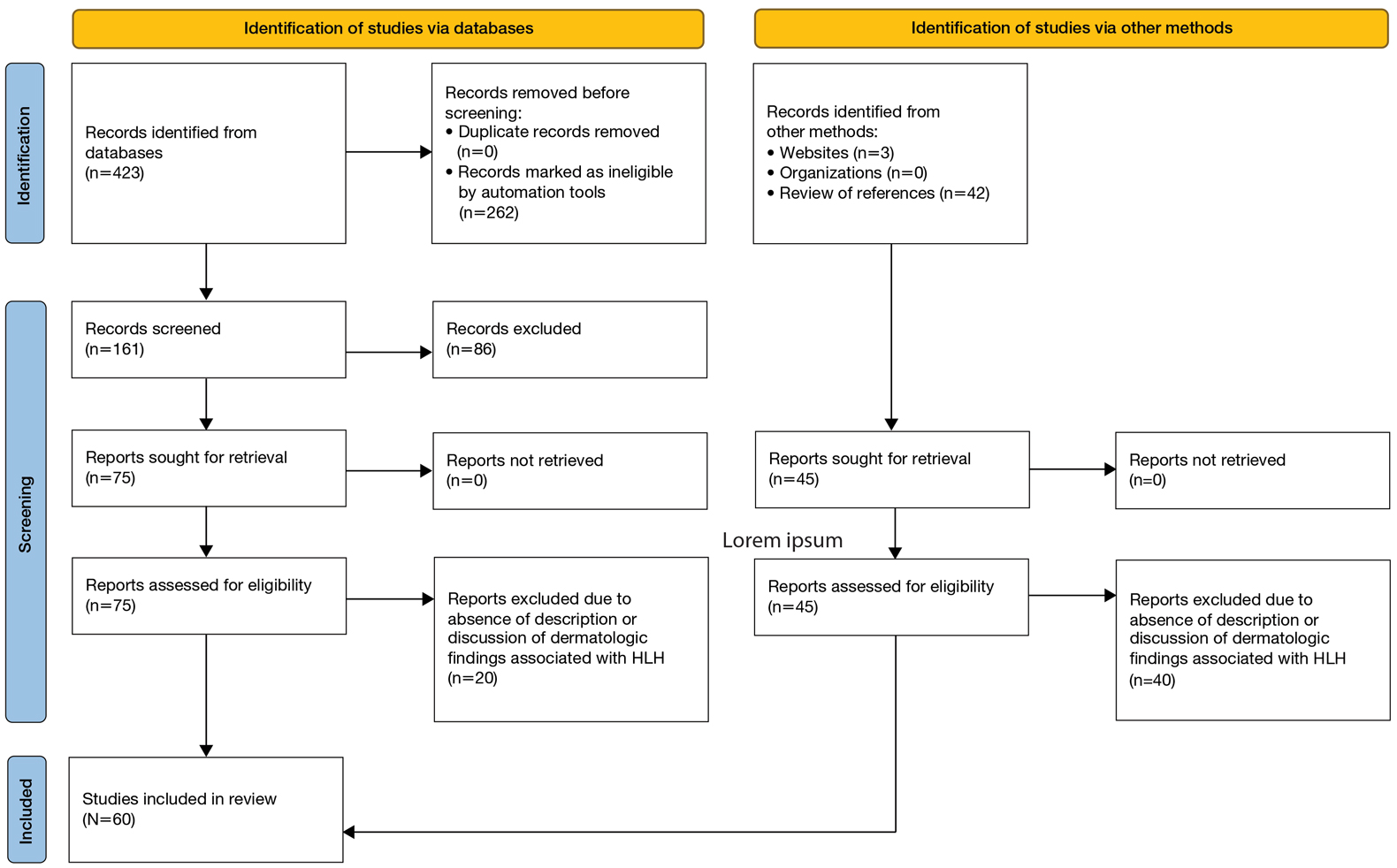

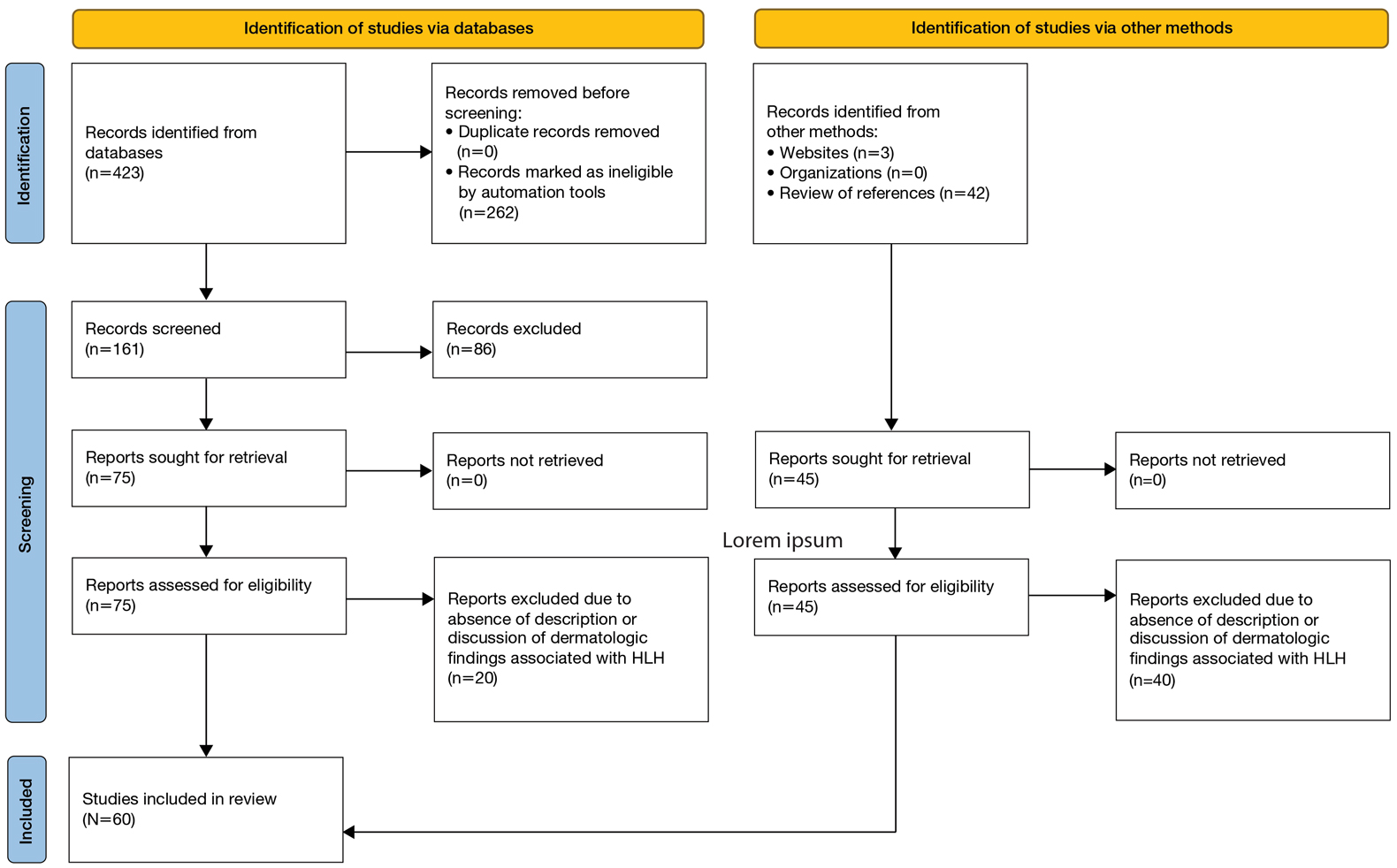

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the phrase (cutaneous OR dermatologic OR skin) findings) AND hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis performed on September 20, 2023, yielded 423 results (Figure 2). Filters to exclude non–English language publications and pediatric populations were applied, resulting in 161 articles. Other exclusion criteria included the absence of a description of dermatologic findings. Seventy-five articles remained after screening titles and abstracts, and full-text review yielded 55 articles that were deemed appropriate for inclusion in the study. Subsequent reference searches and use of the online resource Litmaps revealed 45 additional publications that underwent full-text screening; of these articles, 5 were included in the final review.

Results

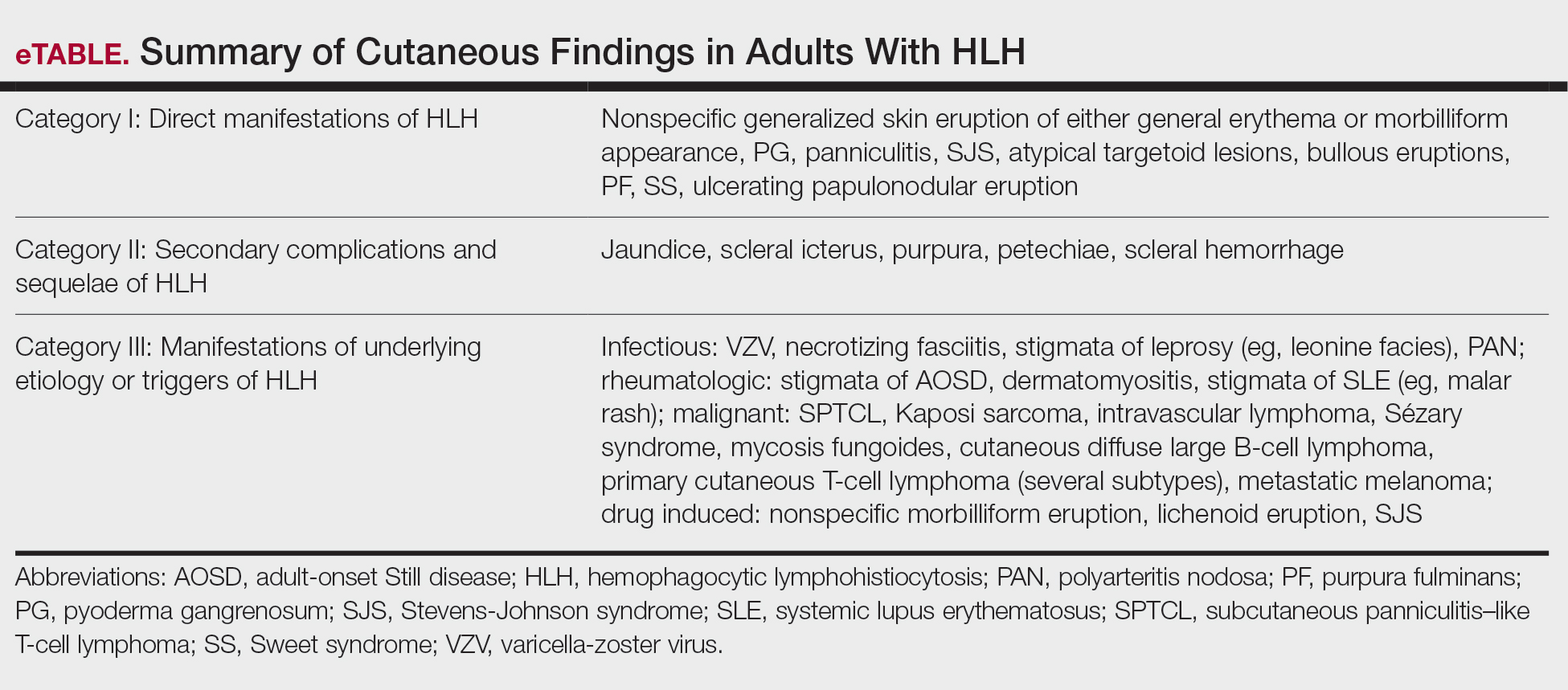

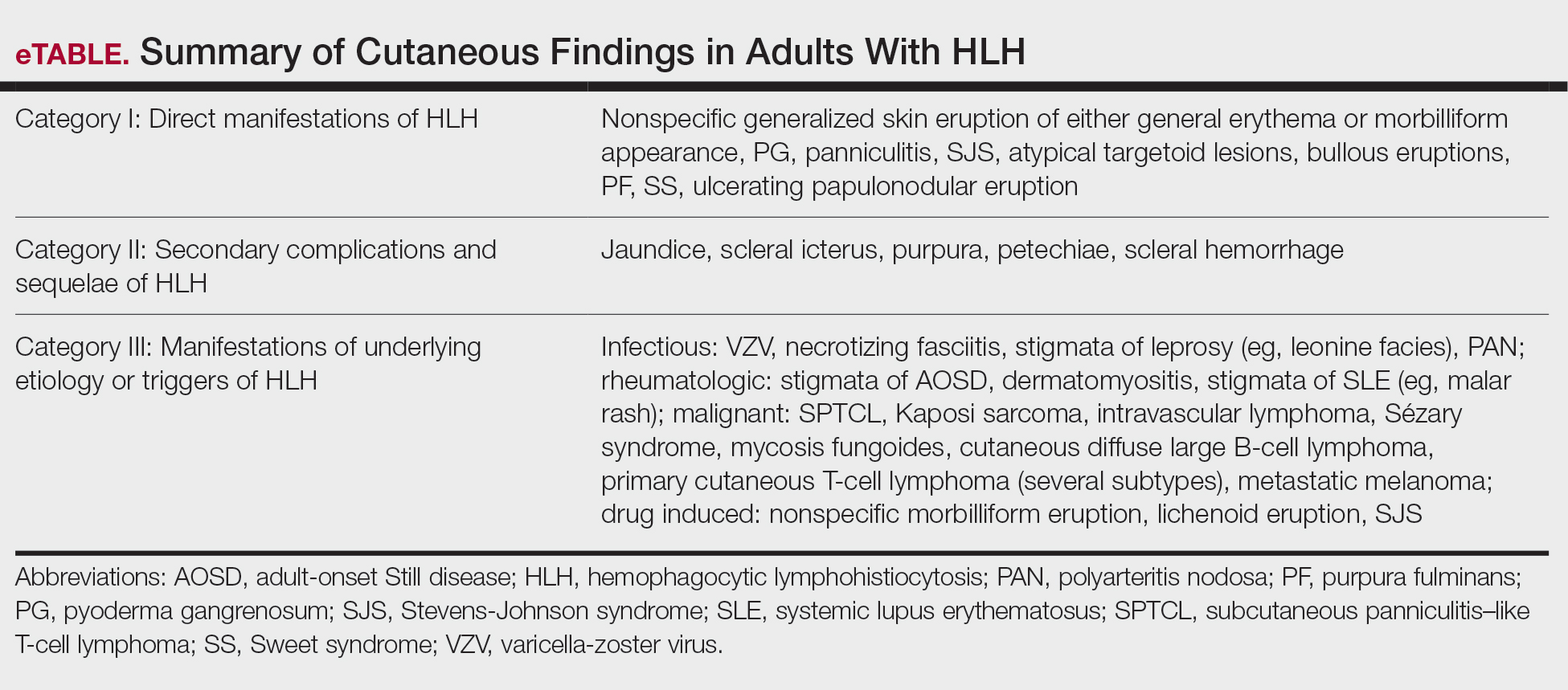

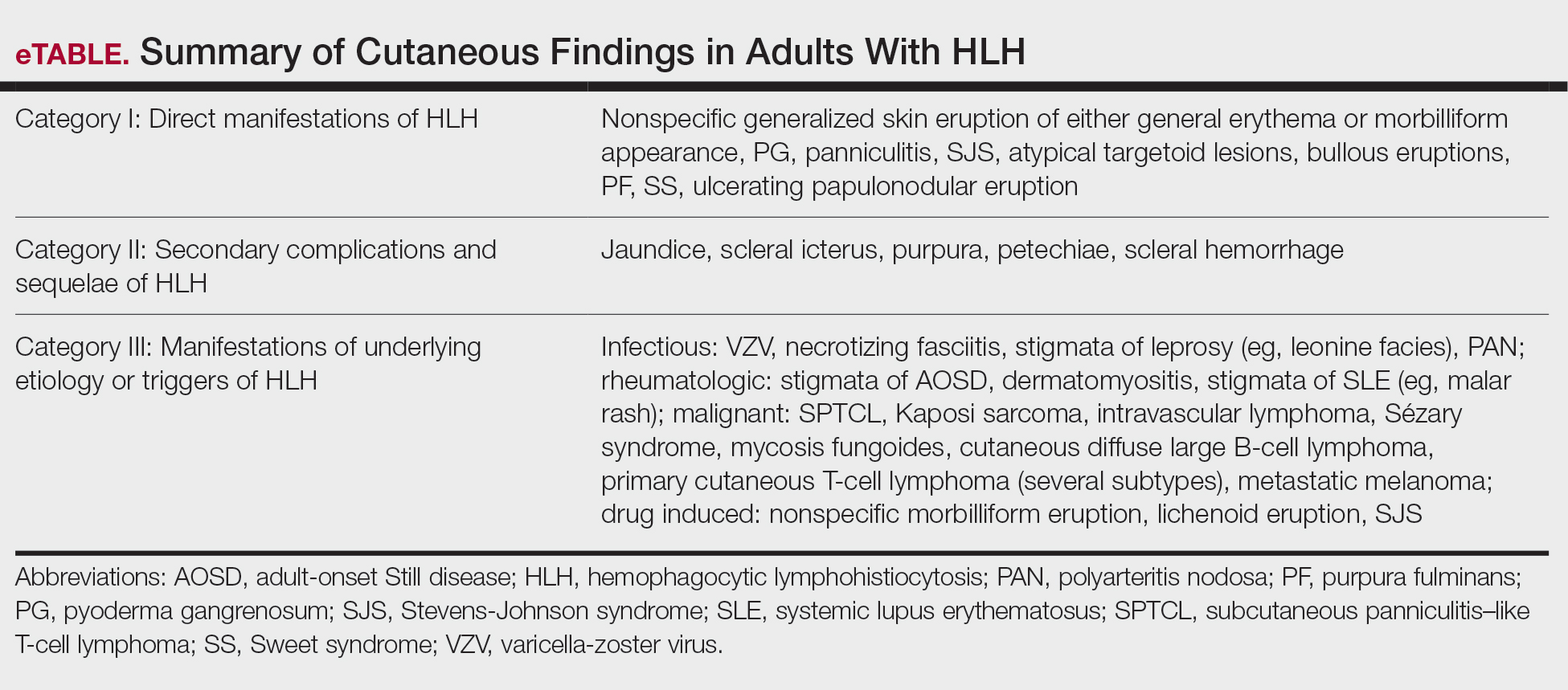

Sixty studies were included in this systematic review.5,7,11-68 The reported prevalence of skin findings among patients with HLH from the included retrospective studies ranged from 15% to 85%.12-15 Several literature reviews reported similarly varied prevalence among adult patients with HLH.7,16 Fardet et al14 categorized cutaneous manifestations of HLH into 3 types: direct manifestations of HLH not explained by systemic features (eg, generalized maculopapular eruption), indirect manifestations of HLH that are explained by systemic features of the disease (eg, purpura due to HLH-induced coagulopathy), and findings specific to the underlying etiology of HLH (eg, malar rash seen in systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]–associated HLH). This categorization served as the outline for the results below, providing an organized review of cutaneous findings and context for how they may support the diagnosis or uncover the underlying etiology of HLH.

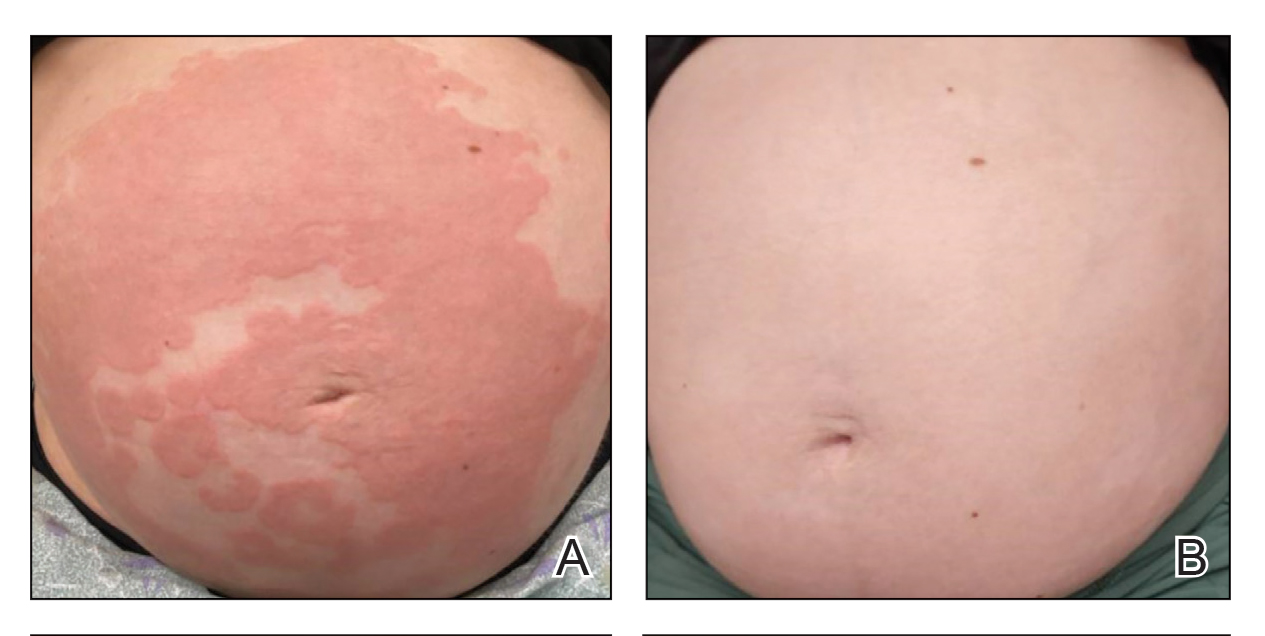

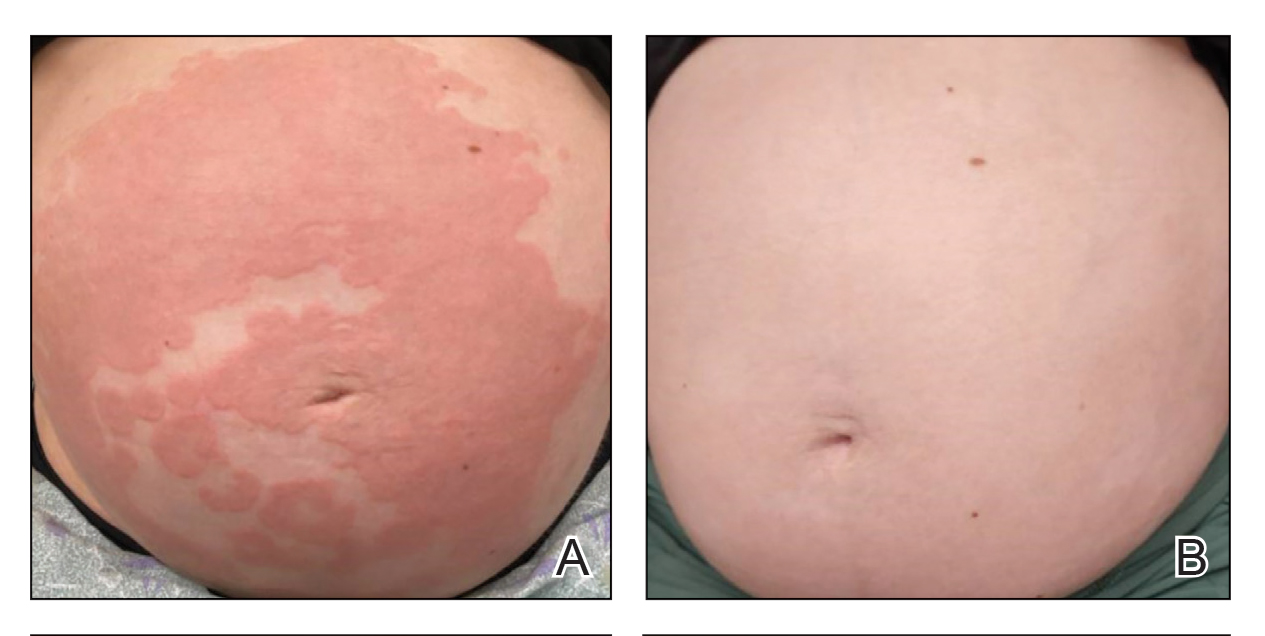

Category I: Direct Manifestations of HLH

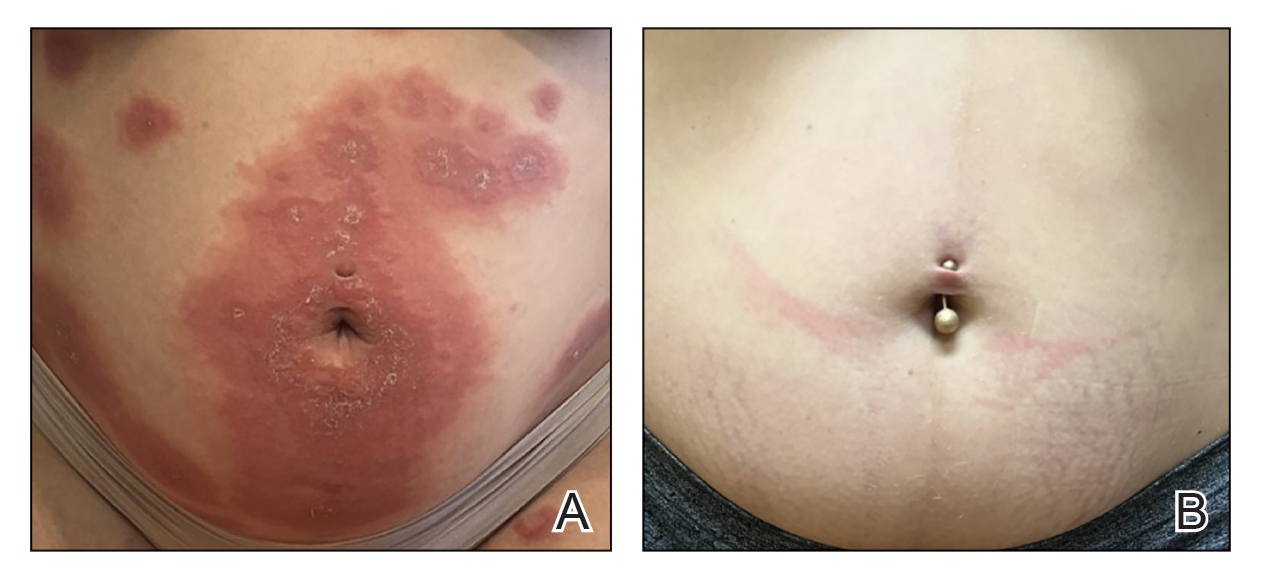

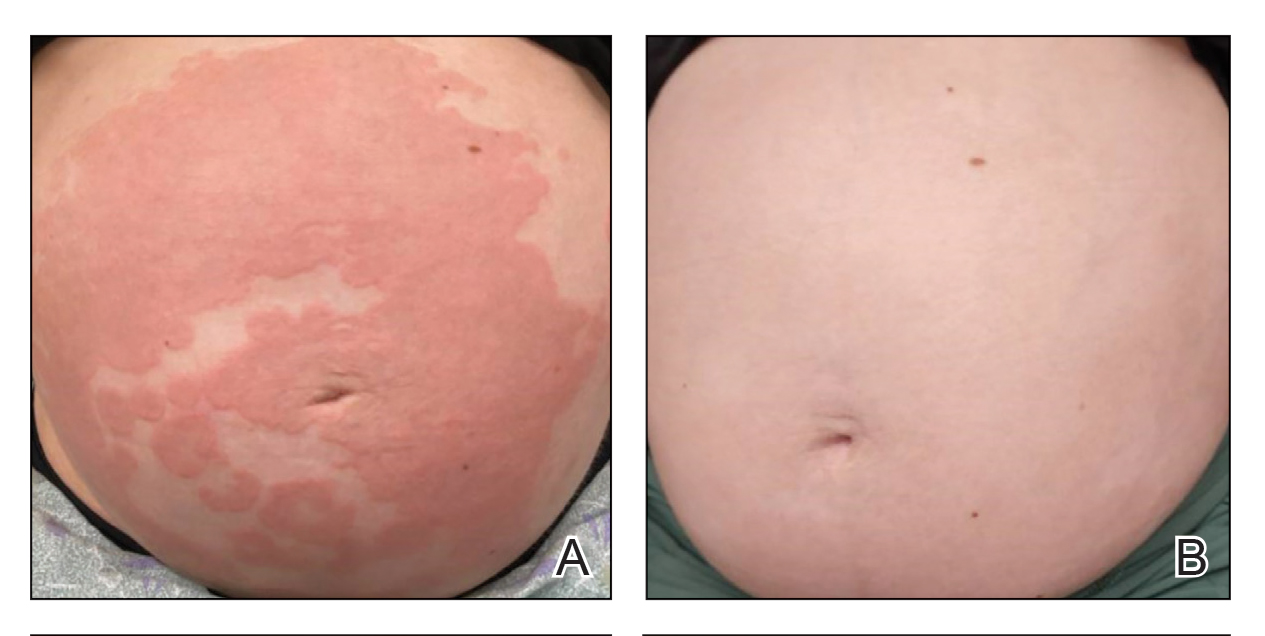

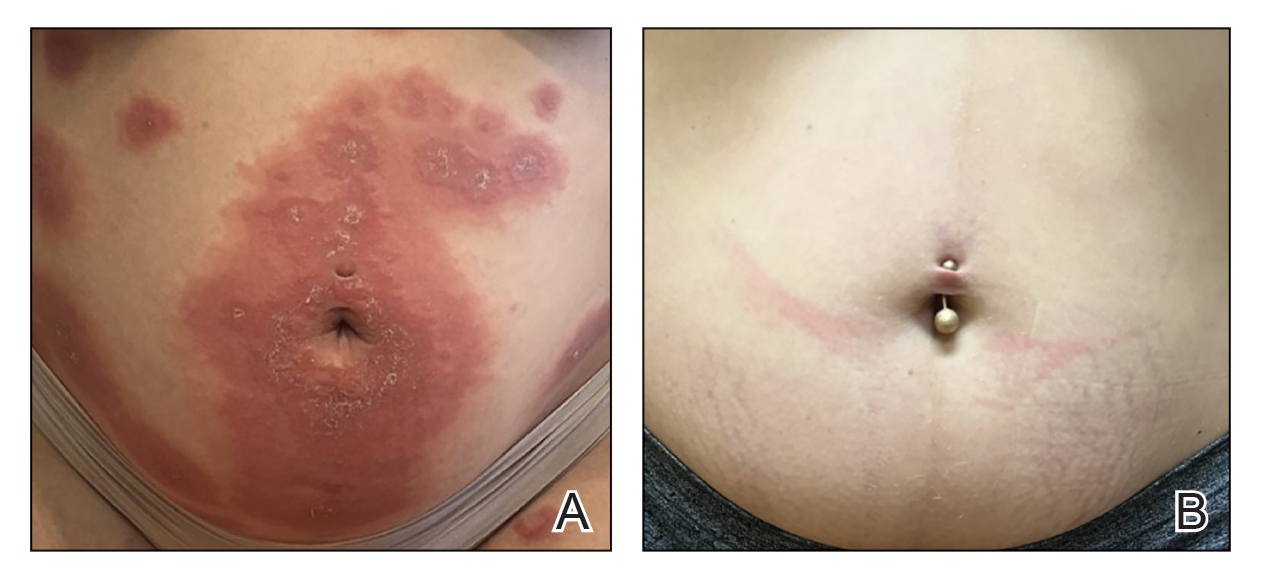

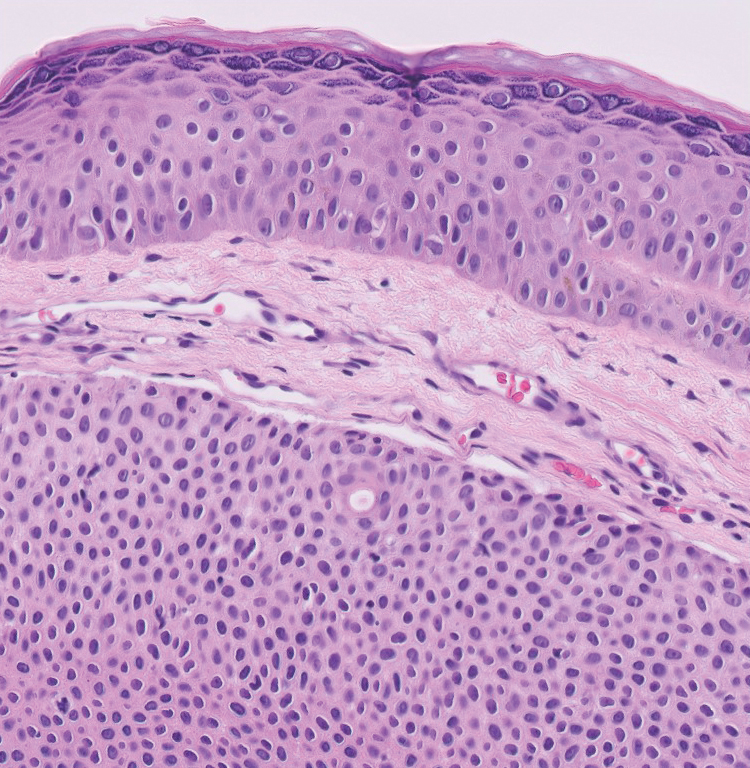

Several articles reported cutaneous findings that seemed to be the direct result of HLH and not attributed to an underlying trigger or sequalae of HLH.11,14,16-31 The most common descriptions were a generalized, morbilliform, or nonspecific eruption that encompasses large areas of the skin, commonly the trunk and extremities, sometimes extending to the face and scalp.14,16-23,25,31,32 There were variations in secondary features such as pruritus and tenderness; some studies also described violaceous discoloration in addition to erythema.16,23

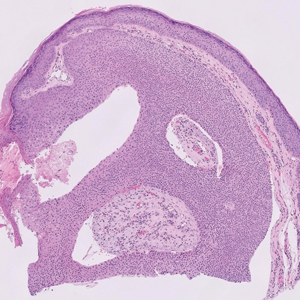

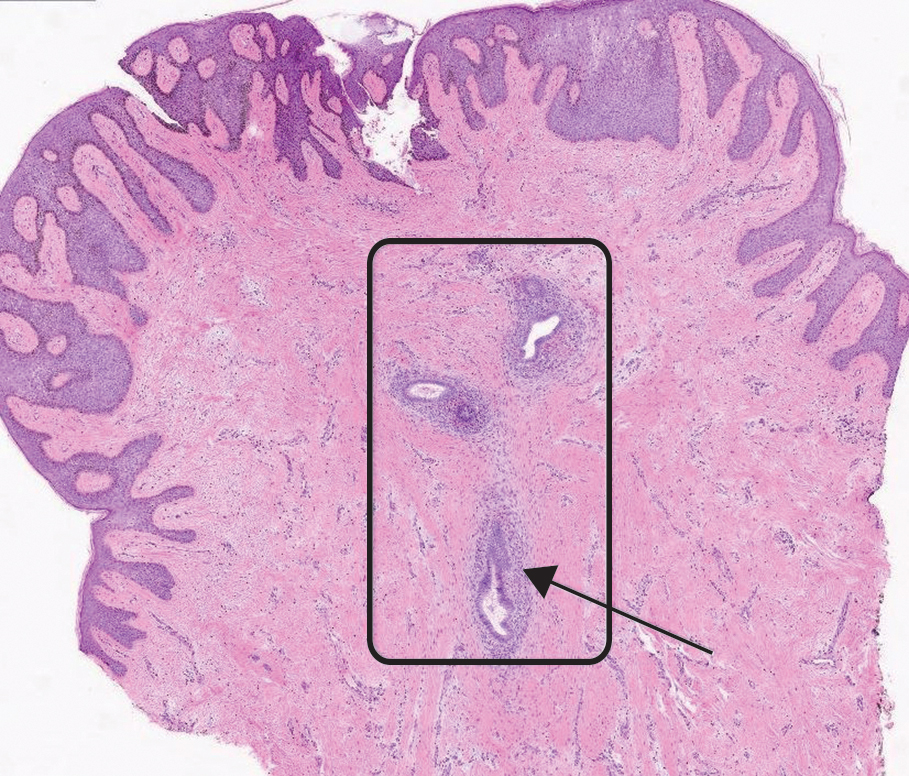

Other skin findings thought to be a direct result of HLH were described in detail by Zerah and DeWitt11 in their retrospective study, including pyoderma gangrenosum, panniculitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, atypical targetoid lesions, and bullous eruptions. The authors also analyzed dermatopathologic data that ultimately revealed that pathologic analysis was largely inconsistent and nondescript.11 There was a single case report of purpura fulminans arising alongside signs and symptoms of HLH,26 and several case reports described Sweet syndrome developing around the same time as HLH.27-29 Lastly, Collins et al30 described a case of HLH manifesting with violaceous ulcerating papules and nodules scattered across the legs, abdomen, and arms. Biopsy of this patient’s lesions showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of histiocytes and hemophagocytosis.

Category II: Secondary Complications and Sequelae of HLH

This was the smallest group among the 3 categories, comprising a few case reports and retrospective cohort studies primarily reporting jaundice/icterus and hemorrhagic lesions such as purpura, petechiae, and scleral hemorrhage.11,21,23,33-35 Several literature reviews described these conditions as nonspecific findings in HLH.16,20 The cause of jaundice in HLH likely can be attributed to its characteristic hepatic dysfunction, whereas hemorrhagic lesions likely are the result of both hepatic and bone marrow dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy.

Category III: Manifestations of Underlying Etiology or Triggers of HLH

Infectious—Infection is known to be one of the most common triggers of HLH, with several retrospective studies reporting infectious triggers in approximately 20% of cases.13,15 Although many pathogens have been implicated, only a few of these infection-induced HLH reports described cutaneous findings, which included a case of varicella zoster virus, Escherichia coli necrotizing fasciitis, leprosy, EBV reactivation, parvovirus B19, and both focal and disseminated herpes simplex virus 2.36-42 Most of these patients presented with classic findings of each disease. The case of varicella zoster virus exhibited pruritic erythematous papules on the face, trunk, and limbs.36 The necrotizing fasciitis case presented with tender erythematous swelling of the lower extremity.37 The patient with leprosy exhibited leonine facies and numerous erythematous nodules, plaques, and superficial ulcerating plaques over the trunk and limbs with palmoplantar involvement,39 and both cases of herpes simplex virus 2 reported small bullae either diffusely over the face, trunk, and extremities or over the genitalia.38,40 Interestingly, the cases of parvovirus B19 and EBV reactivation both exhibited polyarteritis nodosa and occurred in patients with underlying autoimmune conditions, raising the question of whether these cases of HLH had a single trigger or were the result of the overall immunologic dysregulation induced by both infection and autoimmunity.41,42

Rheumatologic—Several articles reported dermatologic findings associated with macrophage activation syndrome, a term that often is used to describe HLH associated with autoimmune conditions. Cases of HLH in adult-onset Still disease, dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, and SLE described skin findings characteristic of the underlying rheumatologic disease, sometimes with acutely worse dermatologic findings at the time of HLH presentation.35,41-48 With regard to SLE, the acute manifestation of classic findings of the disease with HLH has sometimes been described as acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS).48 Lambotte at al48 described common findings of acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome in their retrospective study as malar rash, weight loss, polyarthralgia, and nephritis in addition to classic HLH findings including fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Many other rheumatologic conditions have been associated with HLH, including rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren disease. All these conditions can have dermatologic manifestations; however, no descriptions of dermatologic findings in cases of HLH associated with these diseases were found.13

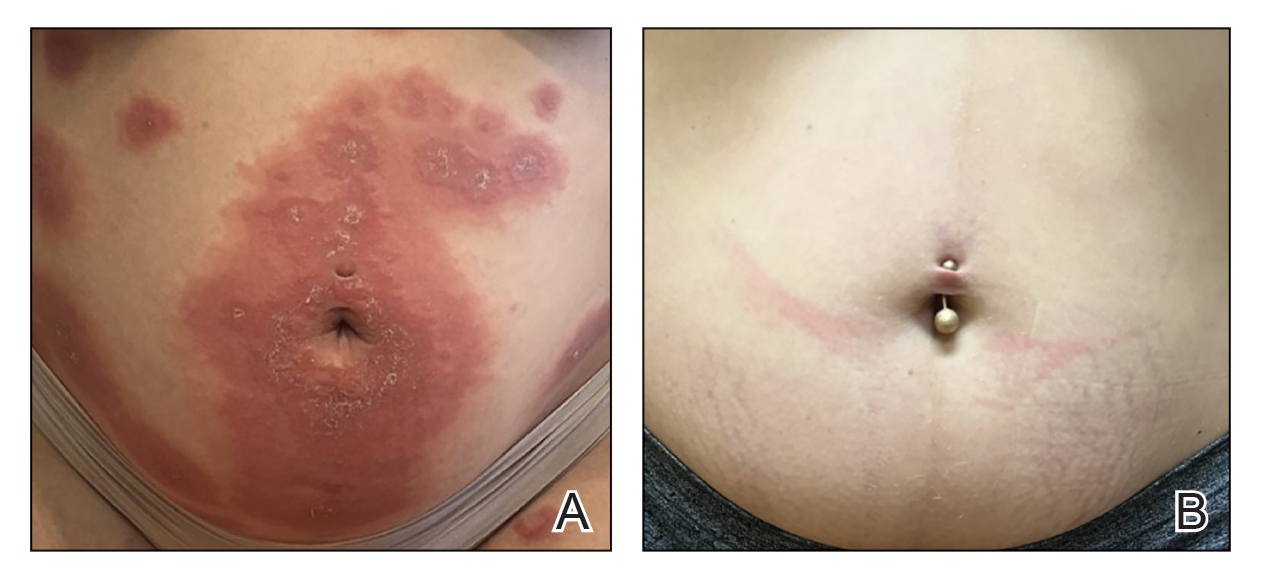

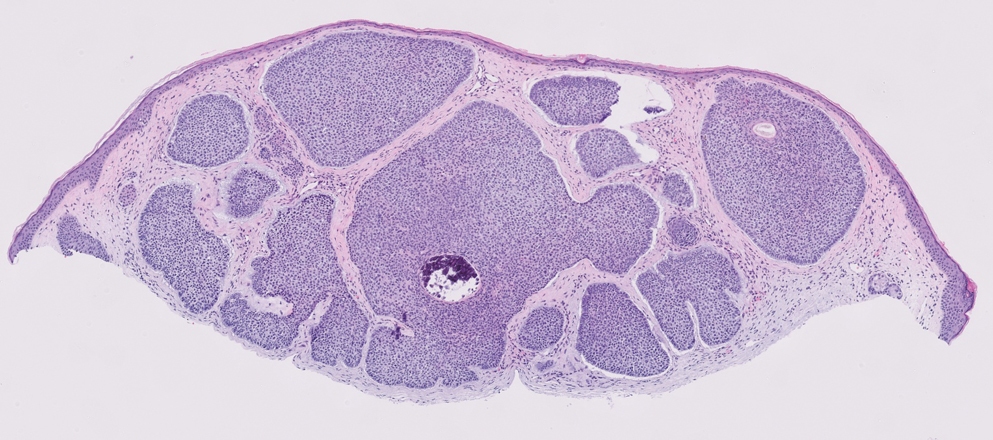

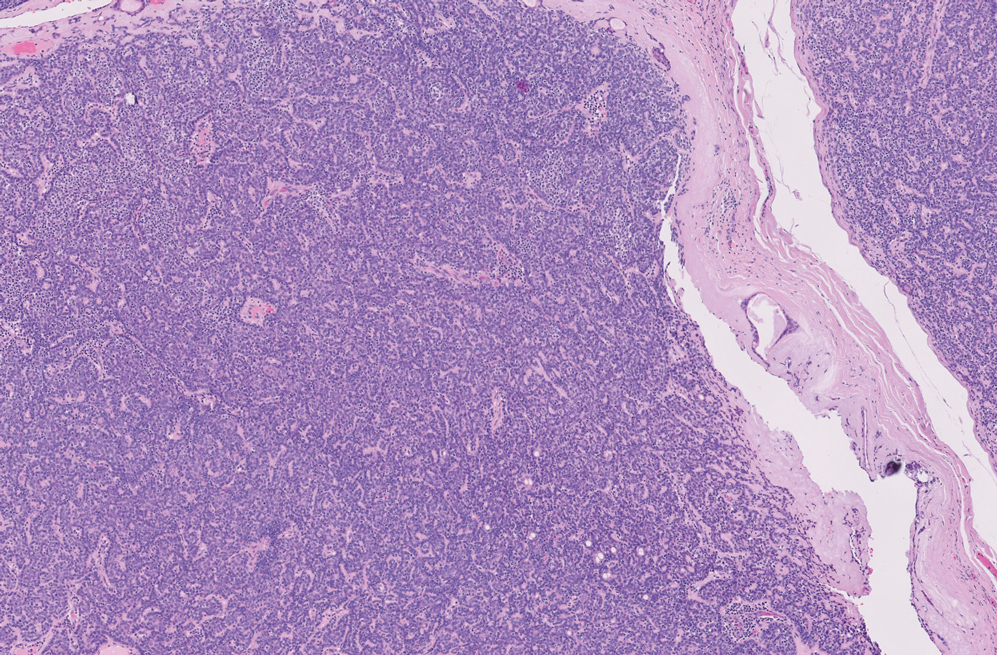

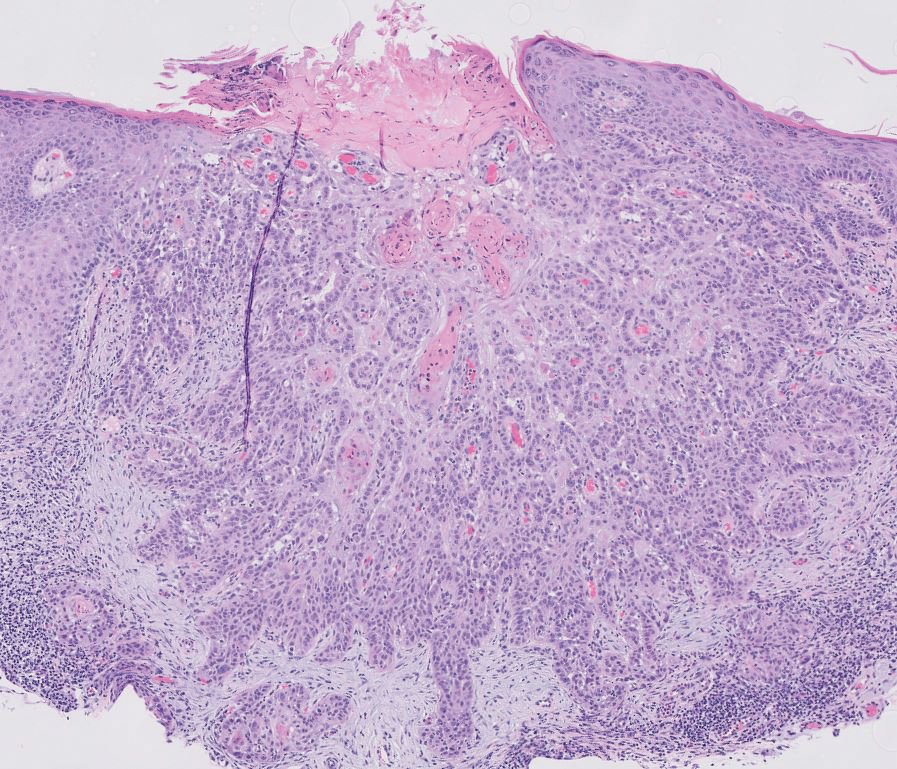

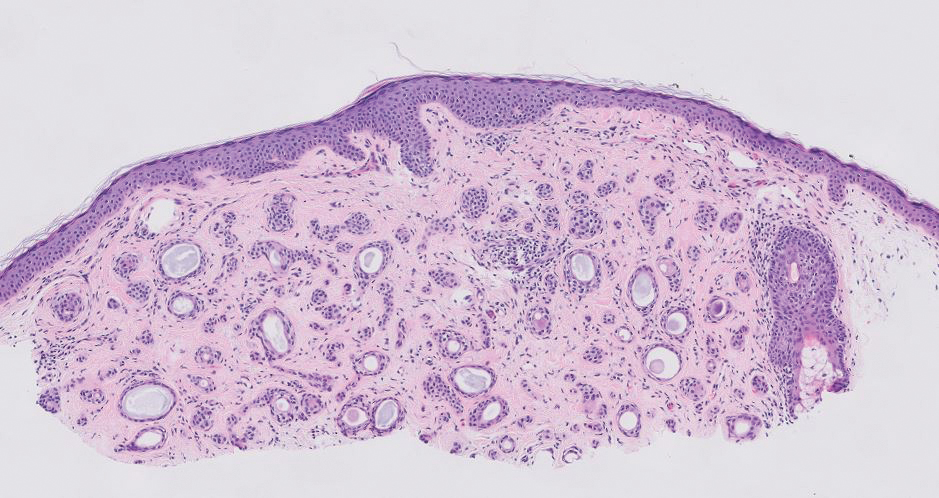

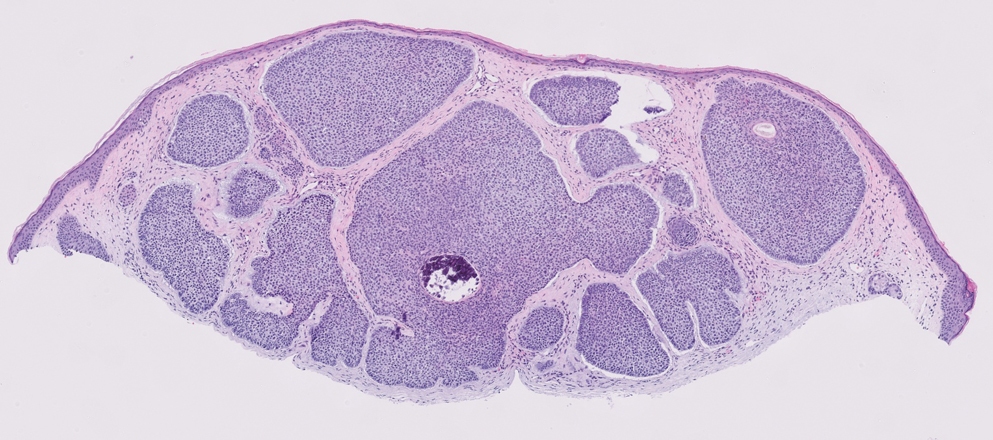

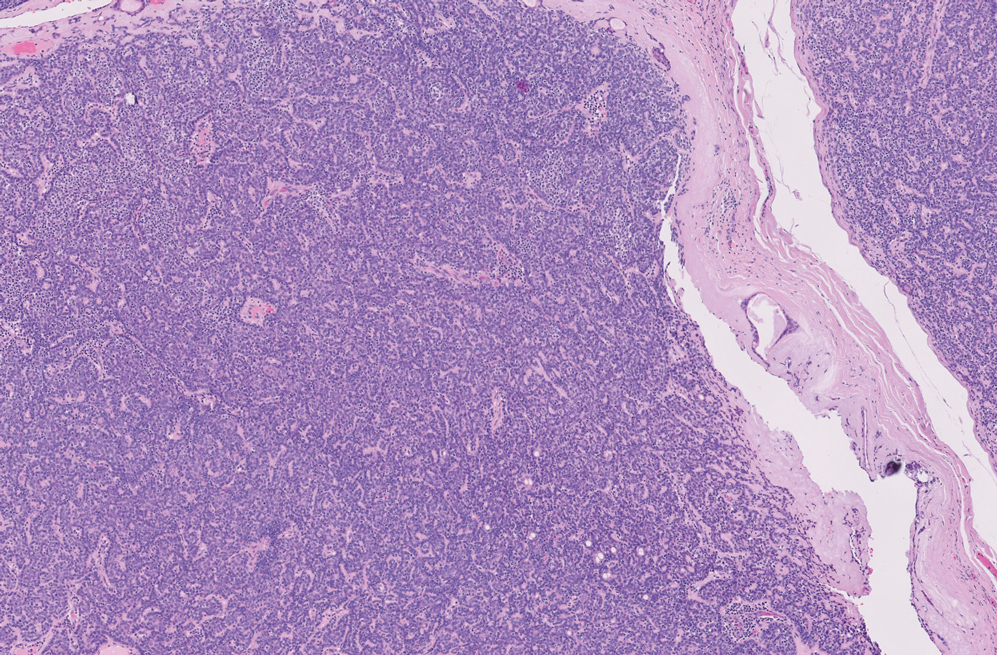

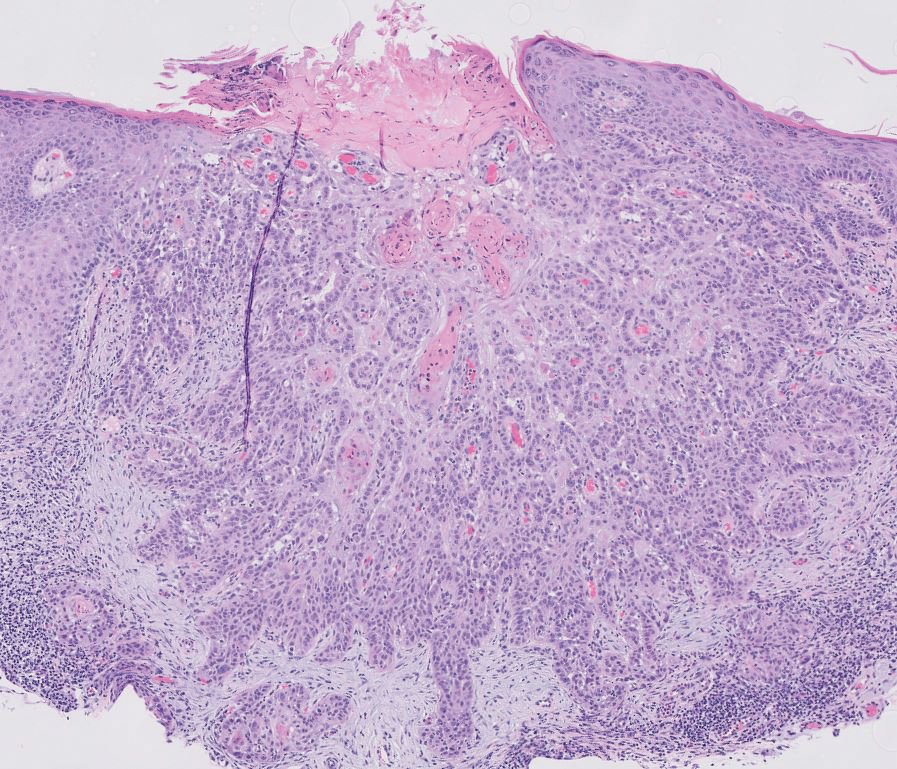

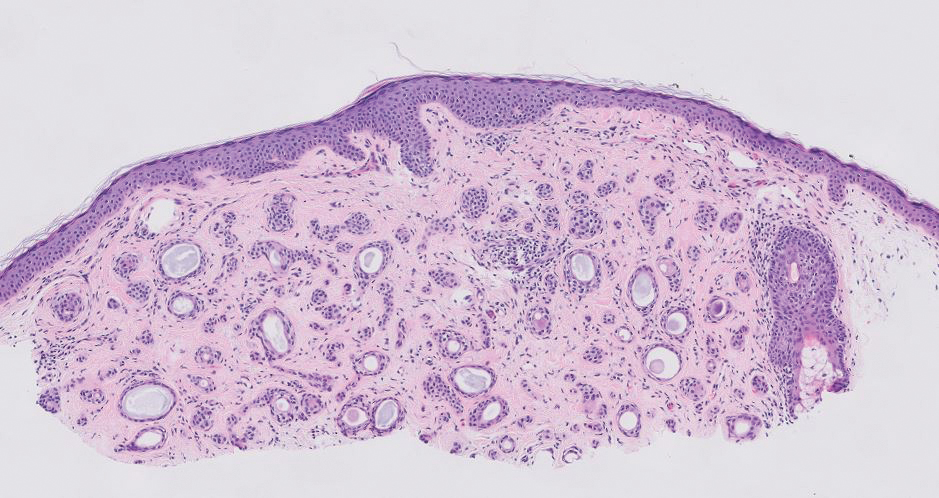

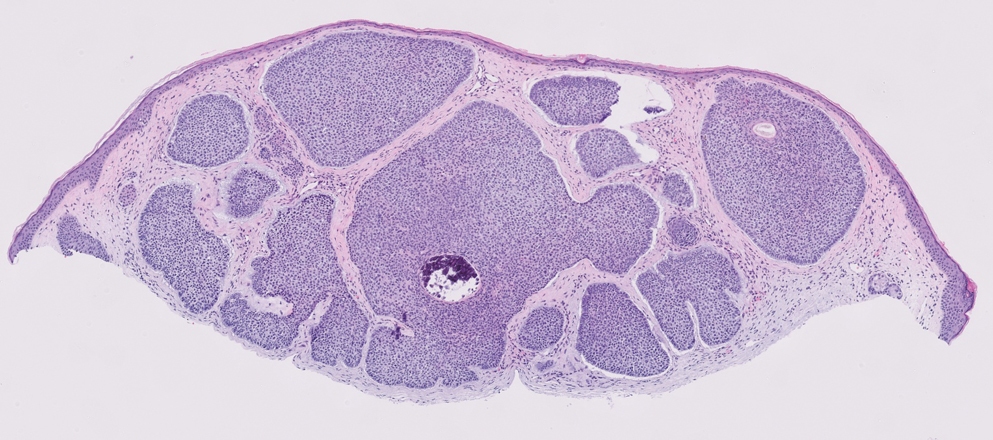

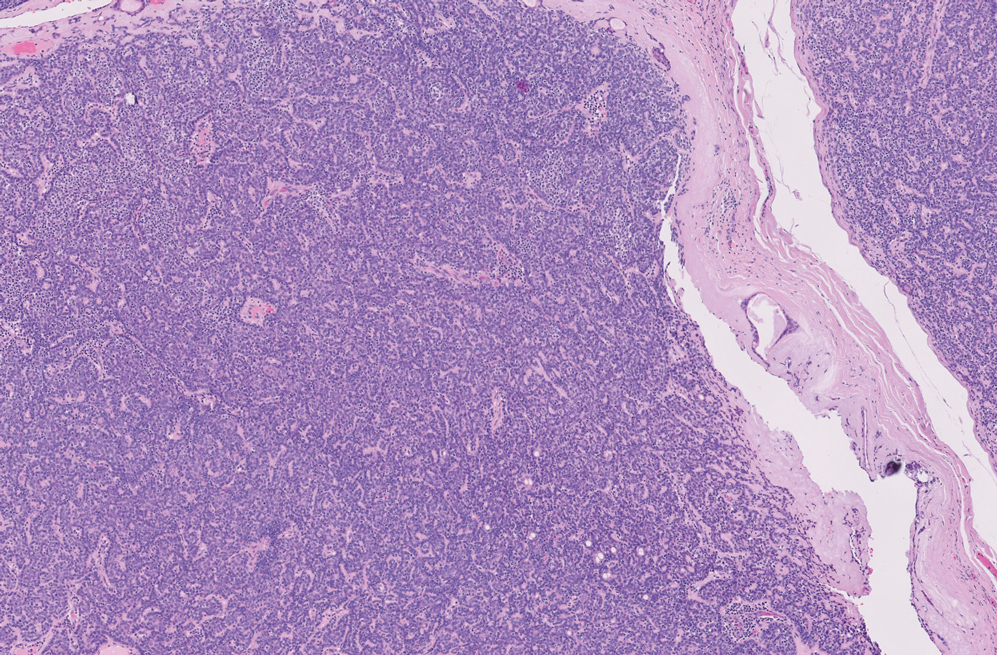

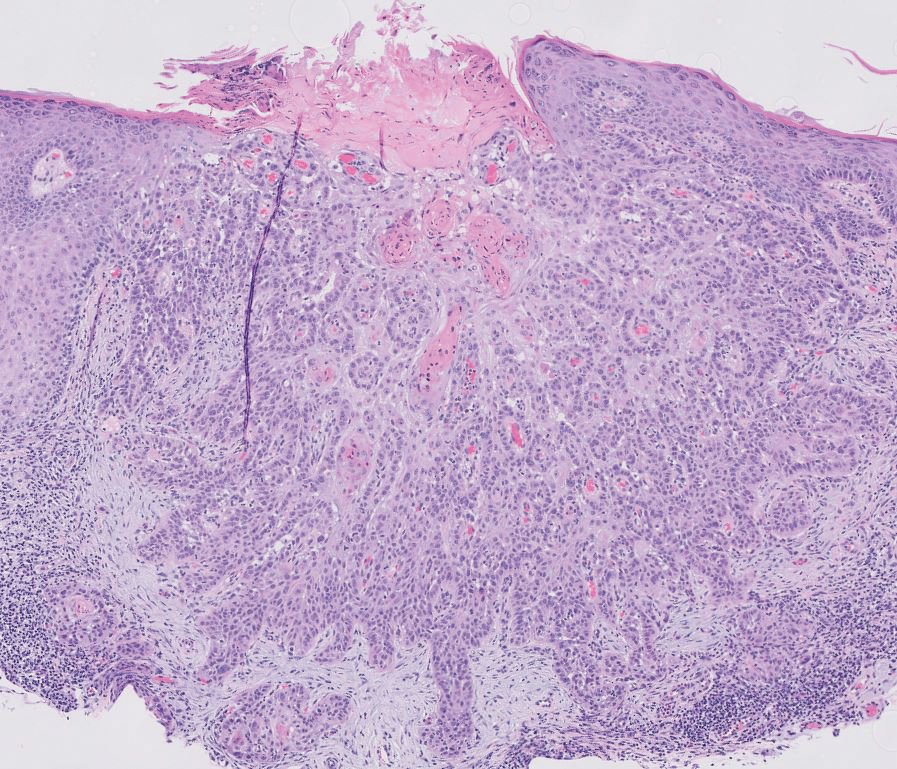

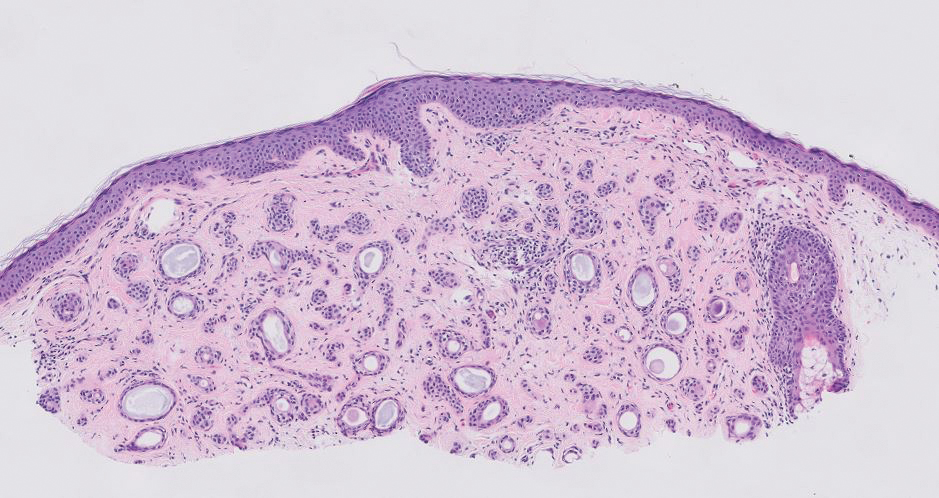

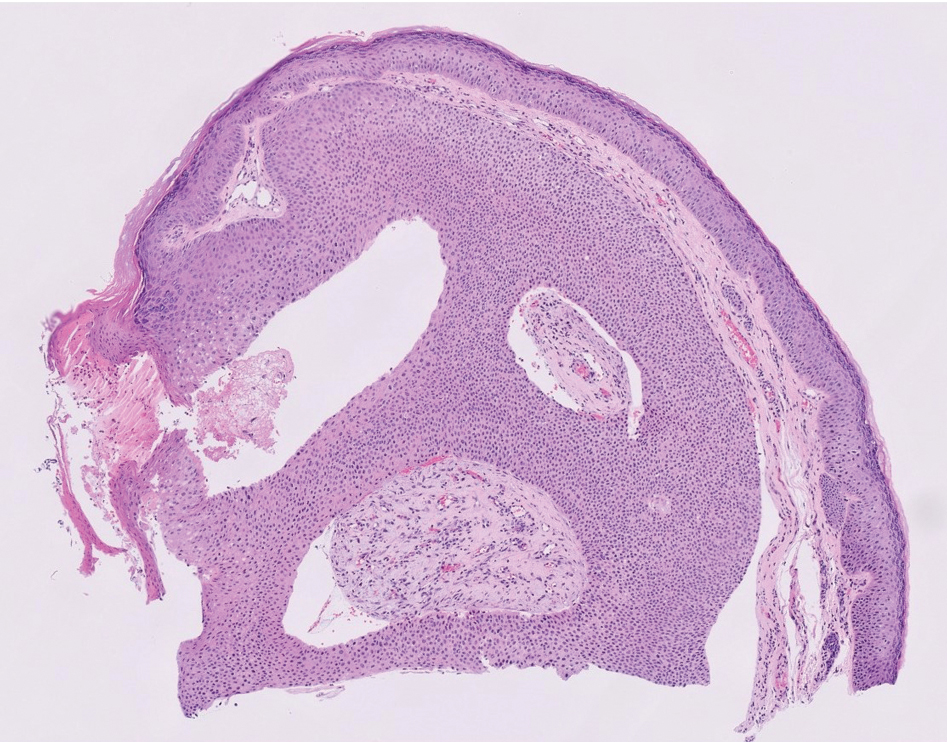

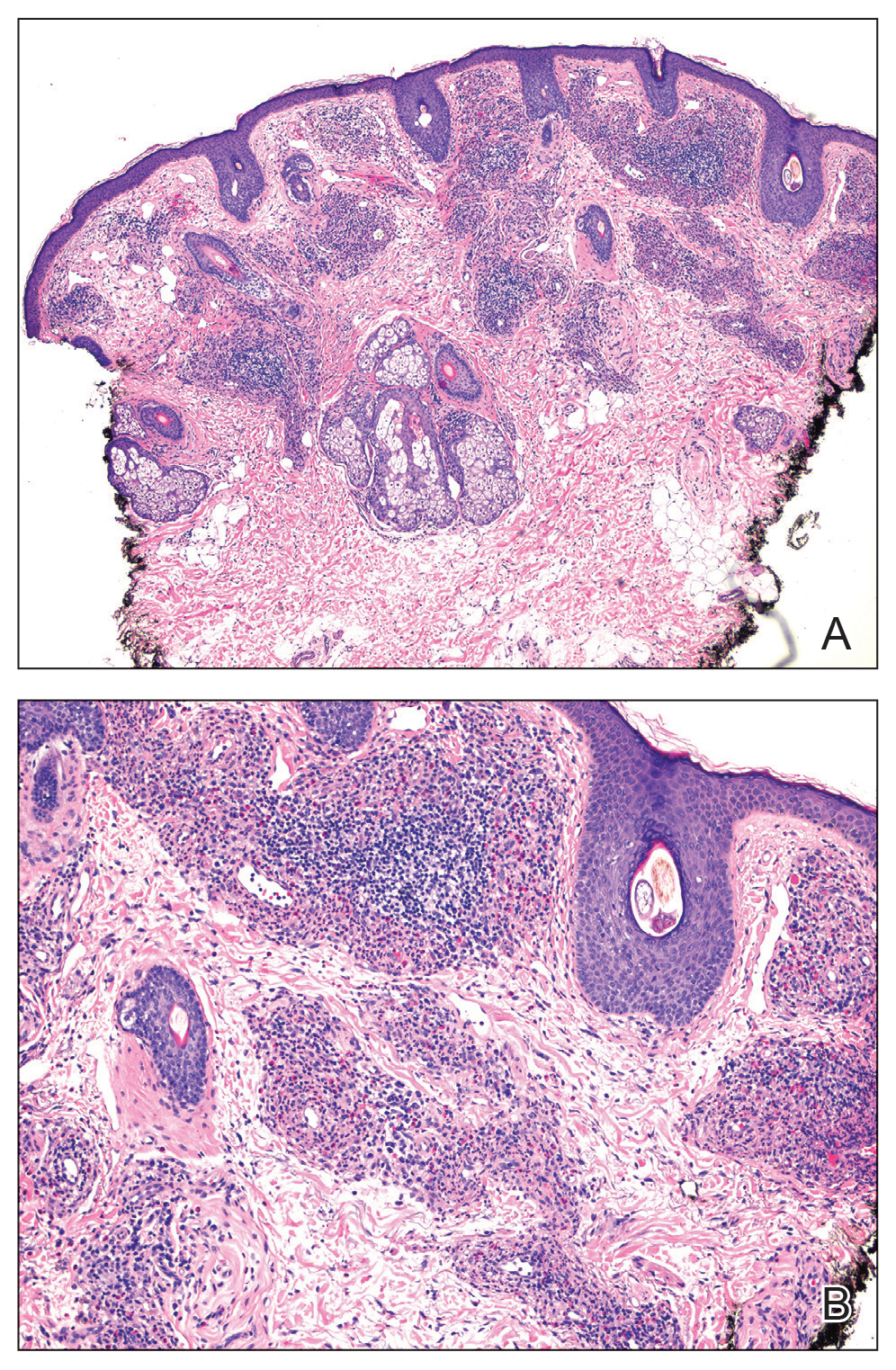

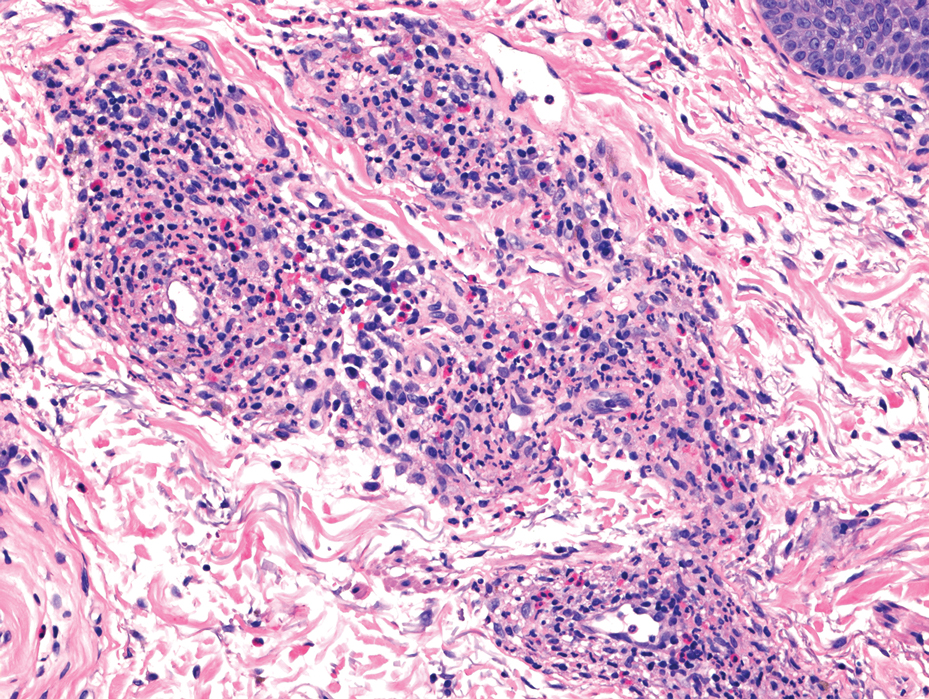

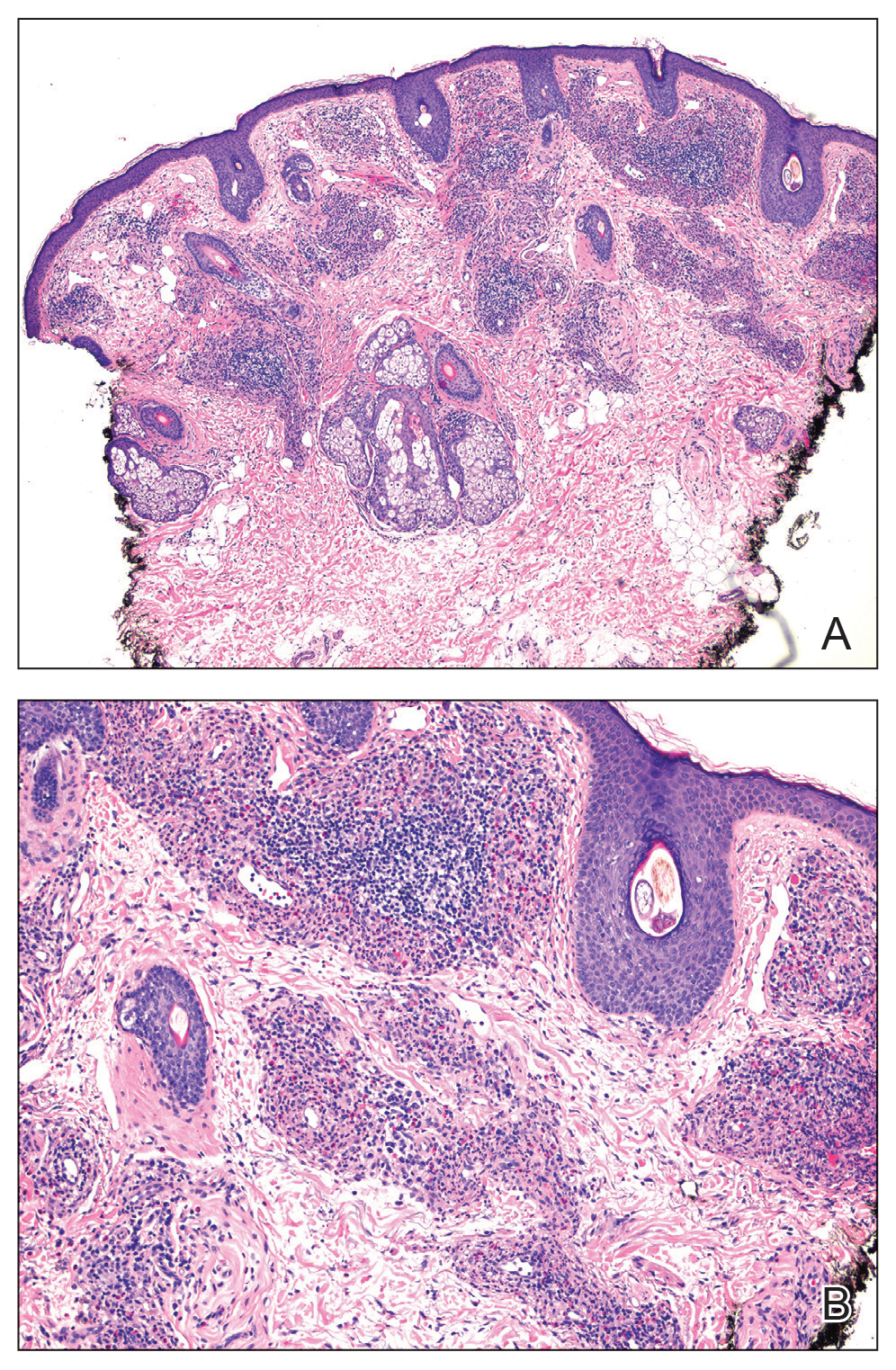

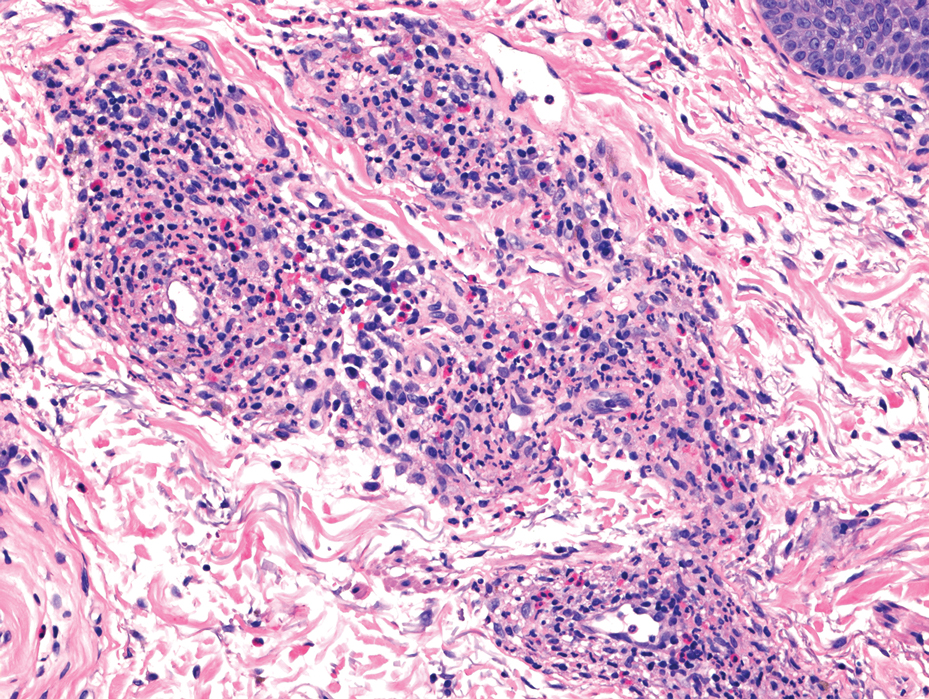

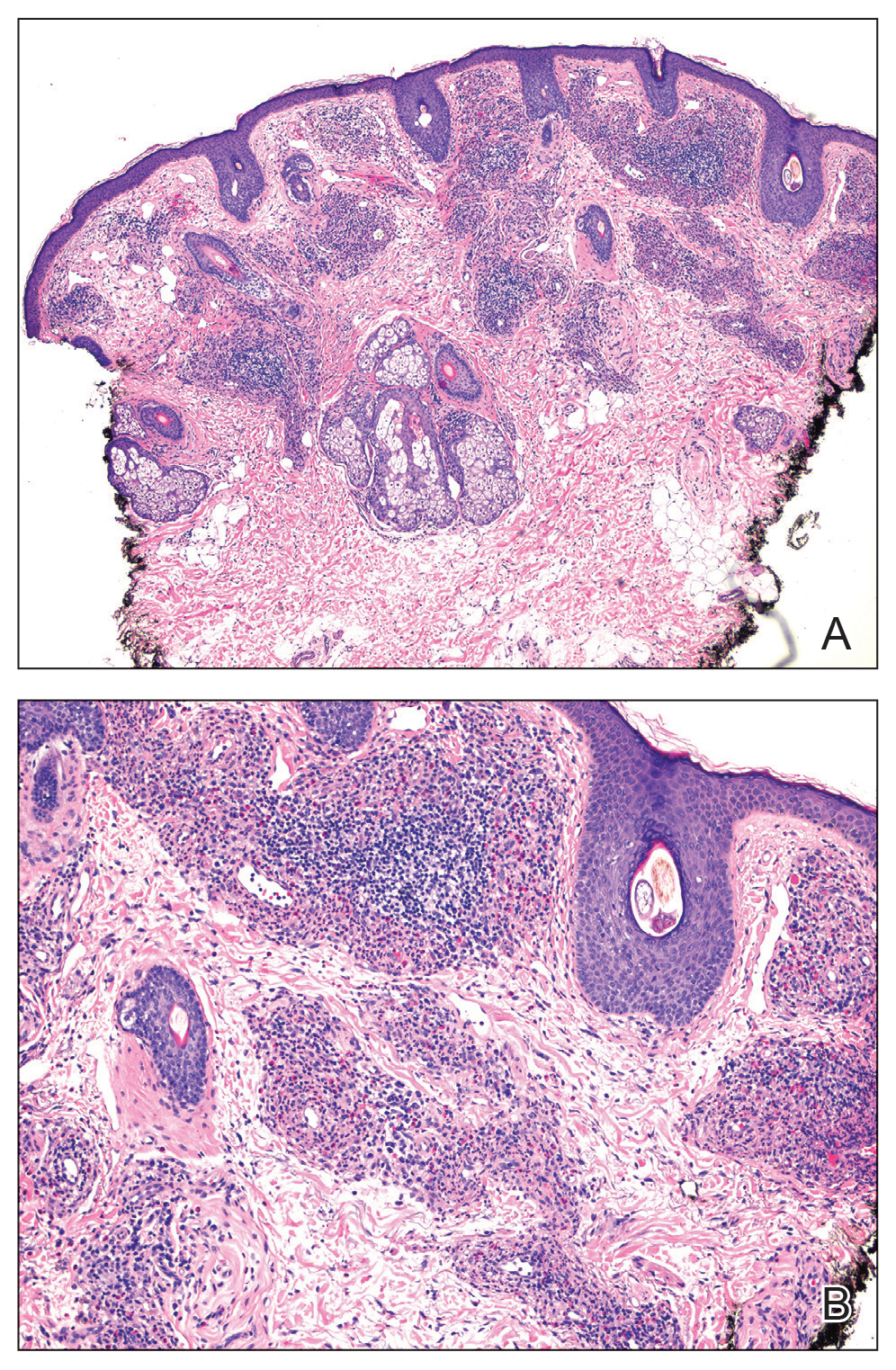

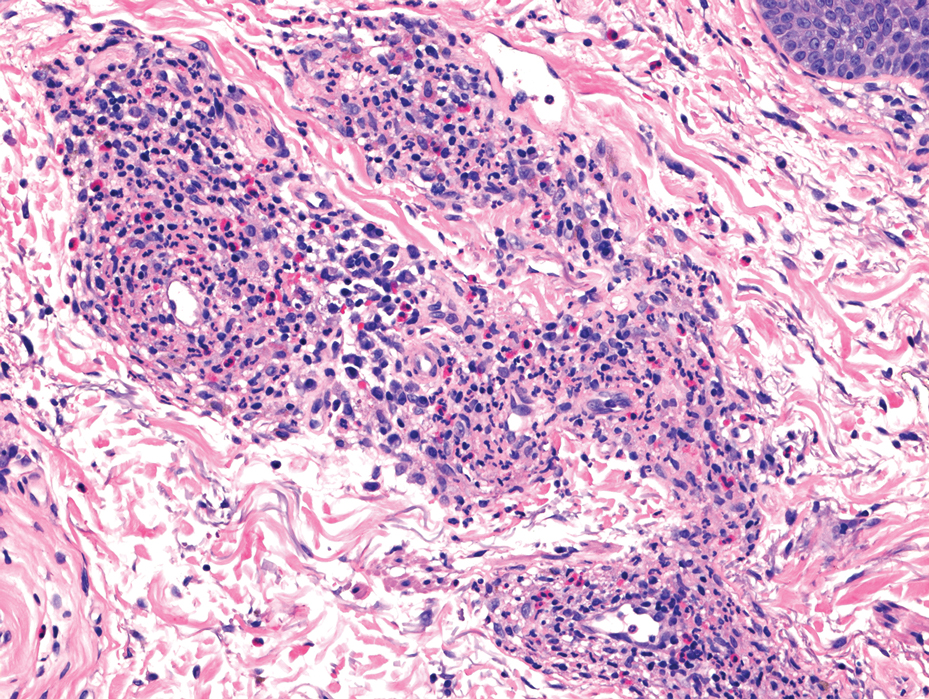

Malignancy—Several cases of malignancy-induced HLH described cutaneous findings, the majority being cutaneous lymphomas, namely subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). Other less commonly reported malignancies in this group included Kaposi sarcoma, intravascular lymphoma, Sézary syndrome, mycosis fungoides, cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and several subtypes of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2,32,49-60 The most common description of SPTCL included multiple scattered plaques and subcutaneous nodules, some associated with tenderness, induration, drainage, or hemorrhagic features.32,50,52,55,57,60 Cases of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome presented with variations in size and distribution of erythroderma with associated lymphadenopathy.2 A unique case of HLH developing in a patient with intravascular lymphoma described an eruption of multiple telangiectasias and petechial hemorrhages on the trunk,58 while one case associated with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma presented with a rapidly enlarging tumor with central ulceration and eschar.59

Drug Induced—Interestingly, most of the drug-induced cases of HLH identified in our search were secondary to biologic therapies used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma, specifically the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have been reported to have an association with HLH in prior literature reviews.61-65 Choi et al66 described an interesting case of ICI-induced HLH presenting with a concurrent severe lichenoid drug eruption that progressed from a pruritic truncal rash to mucocutaneous bullae, erosions, and desquamation resembling a Stevens-Johnson syndrome–type picture. This patient had treatment-refractory, HIV-negative Kaposi sarcoma, where the underlying immunologic dysregulation may explain the more severe cutaneous presentation not observed in other reported cases of ICI-induced HLH.

Yang et al’s67 review of 23 cases with concurrent diagnoses of HLH and DIHS found that 61% (14/23) of cases were diagnosed initially as DIHS before failing treatment and receiving a diagnosis of HLH several weeks later. Additionally, the authors found that several cases met criteria for one diagnosis while clinically presenting strongly for the other.67 This overlap in clinical presentation also was demonstrated in Zerah and DeWitt’s11 retrospective study regarding cutaneous findings in HLH, in which several of the morbilliform eruptions thought to be contributed to HLH ultimately were decided to be drug reactions.

Comment

Regarding direct (or primary) cutaneous findings in HLH (category I), there seem to be 2 groups of features associated with the onset of HLH that are not related to its characteristic hepatic dysfunction (category II) nor its underlying triggers (category III): a nonspecific, generalized, erythematous eruption; and dermatologic conditions separate from HLH itself (eg, Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum). Whether the latter group truly is a direct manifestation of HLH is difficult to discern with the evidence available. Nevertheless, we can conclude that there is some type of association between these dermatologic diseases and HLH, and this association can serve as both a diagnostic tool for clinicians and a point of interest for further clinical research.

The relatively low number of articles identified through our systematic review that specifically reported secondary findings, such as jaundice or coagulopathy-associated hemorrhagic lesions, may lead one to believe that these are not common findings in HLH; however, it is possible that these are not regularly reported in the literature simply because these findings are nonspecific and can be considered expected results of the characteristic organ dysfunction in HLH.

As suspected, the skin findings in category III were the most broad given the variety of underlying etiologies that have been associated with HLH. Like the other 2 categories, these skin findings generally are nonspecific to HLH; however, the ones in category III are specific to underlying etiology of HLH and may aid in identifying and treating the underlying cause of a patient’s HLH when indicated.

Most of the rheumatologic diseases seem to have been known at the time of HLH development and diagnosis, which may highlight the importance of considering a diagnosis of HLH early on in patients with known autoimmune disease and systemic signs of illness or acutely worsening signs and symptoms of their underlying autoimmune disease.

Interestingly, several cases of malignancy-associated HLH reported signs and symptoms of HLH at initial presentation of the malignant disease.32,50,59 This situation seems to be somewhat common, as Go and Wester’s68 systematic analysis of 156 patients with SPTCL found HLH was the presenting feature in 37% of patients included in their study. This may call attention to the importance of considering cutaneous lymphomas as the cause of skin lesions in patients with signs and symptoms of HLH, where it may be easy to assume that skin findings are a result of their systemic disease.

In highlighting cases of HLH related to medication use, we found it pertinent to include and discuss the complex relationship between drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS [formerly known as drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS] syndrome) and HLH. The results of this study suggest that DIHS may have considerable clinical overlap with HLH11 and may even lead to development of HLH,67 creating difficulty in distinguishing between these conditions where there may be similar findings, such as cutaneous eruptions, fever, and hepatic or other internal organ involvement. We agree with Yang et al67 that there can be large overlap in symptomology between these two conditions and that more investigation is necessary to explore the relationship between them.

Conclusion

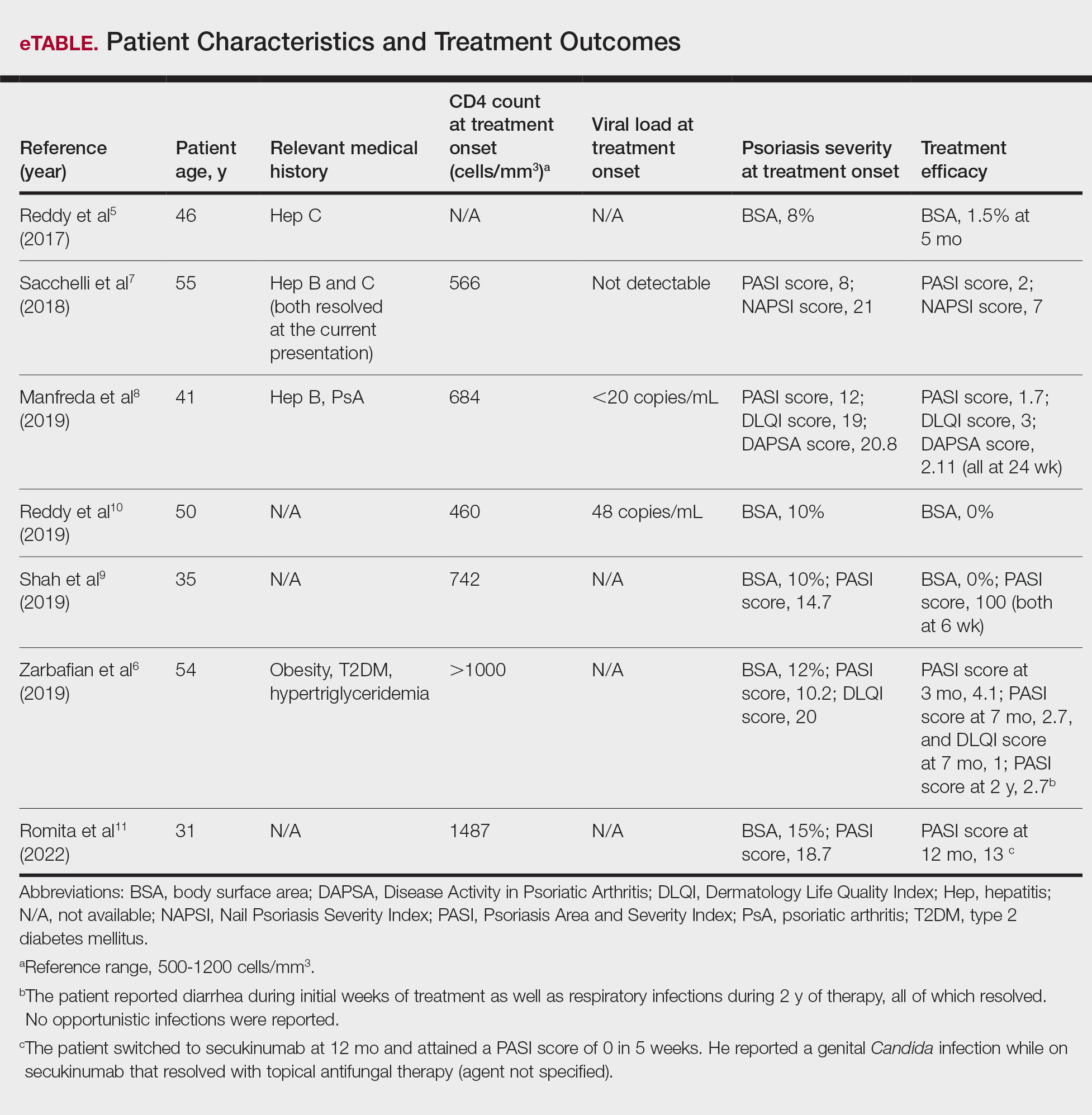

Diagnosis of HLH in adults continues to be challenging, with several diagnostic tools but no true gold standard. In addition to the nonspecific symptomology, there is a myriad of cutaneous findings that can be present in adults with HLH (eTable), all of which are also nonspecific. Even so, awareness of which dermatologic findings have been associated with HLH may provide a cue to consider HLH in the systemically ill patient with a notable dermatologic examination. Furthermore, there are several avenues for further investigation that can be drawn, including further dermatologic analysis among nonspecific eruptions attributed to HLH, clinical and pathologic differentiation between DIHS/DRESS and HLH, and correlation between severity of skin manifestations and severity of HLH disease.

Limitations of this study included a lack of clarity in diagnosis of HLH in patients described in the included articles, as some reports use variable terminology (HLH vs hemophagocytic syndrome vs macrophage activation syndrome, etc), and it is impossible to know if all authors used the same diagnostic criteria—or any validated diagnostic criteria—unless specifically stated. Additionally, including case reports in our study limited the amount and quality of information described in each report. Despite its limitations, this systematic review outlines the cutaneous manifestations associated with HLH. These data will promote clinical awareness of this complex condition and allow for consideration of HLH in patients meeting criteria for HLH syndrome. More studies ultimately are needed to differentiate HLH from its mimics.

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

- Blom A, Beylot-Barry M, D’Incan M, et al. Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (LAHS) in advanced-stage mycosis fungoides/ Sézary syndrome cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:404-410. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.029

- Jordan MB, Allen CE, Greenberg J, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27929. doi:10.1002/pbc.27929

- Griffin G, Shenoi S, Hughes GC. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;34:101515. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101515

- Tomasini D, Berti E. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:395-411.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61048-x

- Sieni E, Cetica V, Piccin A, et al. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis may present during adulthood: clinical and genetic features of a small series. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44649. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044649

- Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology. 2009:127-131. doi:10.1182 /asheducation-2009.1.127

- Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2613-2620. doi:10.1002/art.38690

- Zerah ML, DeWitt CA. Cutaneous findings in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Dermatology. 2015;230:234-243. doi:10.1159/000368552

- Fardet L, Galicier L, Vignon-Pennamen MD, et al. Frequency, clinical features and prognosis of cutaneous manifestations in adult patients with reactive haemophagocytic syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:547-553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09549.x

- Dhote R, Simon J, Papo T, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult systemic disease: report of twenty-six cases and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:633-639. doi:10.1002/art.11368

- Li J, Wang Q, Zheng W, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical analysis of 103 adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:100-105. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000000022

- Tudesq JJ, Valade S, Galicier L, et al. Diagnostic strategy for trigger identification in severe reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a diagnostic accuracy study. Hematol Oncol. 2021;39:114-122. doi:10.1002 /hon.2819

- Sakai H, Otsubo S, Miura T, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome presenting with a facial erythema in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 Suppl):S111-S114. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2006.11.024

- Chung SM, Song JY, Kim W, et al. Dengue-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in an adult: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6159. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000006159

- Esmaili H, Rahmani O, Fouladi RF. Hemophagocytic syndrome in patients with unexplained cytopenia: report of 15 cases. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2013;29:15-18. doi:10.5146/tjpath.2013.01142

- Jiwnani S, Karimundackal G, Kulkarni A, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome complicating lung resection. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2012;20:341-343. doi:10.1177/0218492311435686

- Lee WJ, Lee DW, Kim CH, et al. Dermatopathic lymphadenitis with generalized erythroderma in a patient with Epstein-Barr virusassociated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:357-361. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b2a50f

- Lovisari F, Terzi V, Lippi MG, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicated by multiorgan failure: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9198. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000009198

- Miechowiecki J, Stainer W, Wallner G, et al. Severe complication during remission of Crohn’s disease: hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to acute cytomegalovirus infection. Z Gastroenterol. 2018;56:259-263. doi:10.1055/s-0043-123999

- Ochoa S, Cheng K, Fleury CM, et al. A 28-year-old woman with fever, rash, and pancytopenia. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38:322-327. doi:10.2500/aap.2017.38.4042

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Miura K, et al. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection with cutaneous lymphoproliferation: haemophagocytosis in the skin and haemophagocytic syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e116-e117. doi:10.1111/jdv.14640

- Tzeng HE, Teng CL, Yang Y, et al. Occult subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma with initial presentations of cellulitis-like skin lesion and fulminant hemophagocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106 (2 Suppl):S55-S59. doi:10.1016/s0929-6646(09)60354-5

- Honjo O, Kubo T, Sugaya F, et al. Severe cytokine release syndrome resulting in purpura fulminans despite successful response to nivolumab therapy in a patient with pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung: a case report. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:97. doi:10.1186/s40425- 019-0582-4

- Kao RL, Jacobsen AA, Billington CJ Jr, et al. A case of VEXAS syndrome associated with EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2022;93:102636. doi:10.1016/j .bcmd.2021.102636

- Koga T, Takano K, Horai Y, et al. Sweet’s syndrome complicated by Kikuchi’s disease and hemophagocytic syndrome which presented with retinoic acid-inducible gene-I in both the skin epidermal basal layer and the cervical lymph nodes. Intern Med. 2013;52:1839-1843. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.52.9542

- Lin WL, Lin WC, Chiu CS, et al. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2008;3:305-307.

- Collins MK, Ho J, Akilov OE. Case 52. A unique presentation of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with ulcerating papulonodules. In: Akilov OE, ed. Cutaneous Lymphomas: Unusual Cases 3. Springer International Publishing; 2021:126-127.

- Chakrapani A, Avery A, Warnke R. Primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma with brain involvement and hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:270-272. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3182624e98

- Sullivan C, Loghmani A, Thomas K, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as the initial presentation of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: a rare case responding to cyclosporine A and steroids. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620981531. doi:10.1177/2324709620981531

- Darmawan G, Salido EO, Concepcion ML, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: “a dreadful mimic.” Int J Rheum Dis. 2015; 18:810-812. doi:10.1111/1756-185x.12506

- Maus MV, Leick MB, Cornejo KM, et al. Case 35-2019: a 66-year-old man with pancytopenia and rash. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1951-1960. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1909627

- Chamseddin B, Marks E, Dominguez A, et al. Refractory macrophage activation syndrome in the setting of adult-onset Still disease with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis detected on skin biopsy treated with canakinumab and tacrolimus. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:528-531. doi:10.1111/cup.13466

- Bérar A, Ardois S, Walter-Moraux P, et al. Primary varicella-zoster virus infection of the immunocompromised associated with acute pancreatitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25351. doi:10.1097 /md.0000000000025351

- Chang CC, Hsiao PJ, Chiu CC, et al. Catastrophic hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a young man with nephrotic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;439:168-171. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.025

- Kurosawa S, Sekiya N, Fukushima K, et al. Unusual manifestation of disseminated herpes simplex virus type 2 infection associated with pharyngotonsilitis, esophagitis, and hemophagocytic lymphohisitocytosis without genital involvement. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:65. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3721-0

- Saidi W, Gammoudi R, Korbi M, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an unusual complication of leprosy. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54: 1054-1059. doi:10.1111/ijd.12792

- Yamaguchi K, Yamamoto A, Hisano M, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a pregnant patient. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 2):1241-1244. doi:10.1097 /01.AOG.0000157757.54948.9b

- Hayakawa I, Shirasaki F, Ikeda H, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa associated with Epstein- Barr virus reactivation. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:573-576. doi:10.1007 /s00296-005-0024-0

- Jeong JY, Park JY, Ham JY, et al. Molecular evidence of parvovirus B19 in the cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa tissue from a patient with parvovirus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e22079. doi:10.1097 /md.0000000000022079

- Fujita Y, Fukui S, Suzuki T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome that was successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy and plasmapheresis. Intern Med. 2018;57:3473-3478. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.1121-18

- Honda M, Moriyama M, Kondo M, et al. Three cases of autoimmune- associated haemophagocytic syndrome in dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 autoantibody. Scand J Rheumatol. 2020;49:244-246. doi:10 .1080/03009742.2019.1653493

- Jung SY. Hemophagocytic syndrome diagnosed by liver biopsy in a female patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:449-451. doi:10.1097/rhu.0000000000000040

- Kerl K, Wolf IH, Cerroni L, et al. Hemophagocytosis in cutaneous autoimmune disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:539-543. doi:10.1097 /dad.0000000000000166

- Komiya Y, Saito T, Mizoguchi F, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome complicated with dermatomyositis controlled successfully with infliximab and conventional therapies. Intern Med. 2017;56:3237-3241. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.7966-16

- Lambotte O, Khellaf M, Harmouche H, et al. Characteristics and long-term outcome of 15 episodes of systemic lupus erythematosusassociated hemophagocytic syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85: 169-182. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000224708.62510.d1

- Guitart J, Mangold AR, Martinez-Escala ME, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics and outcomes among patients with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma and related adipotropic lymphoproliferative disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1167-1174. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3347

- Hung GD, Chen YH, Chen DY, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma presenting with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and skin lesions with characteristic high-resolution ultrasonographic findings. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:775-778. doi:10.1007/s10067 -005-0193-y

- Jamil A, Nadzri N, Harun N, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma leg type presenting with hemophagocytic syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:e222-3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.021

- LeBlanc RE, Lansigan F. Unraveling subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: an association between subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, and familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:572-577. doi:10.1111/cup.13863

- Lee DE, Martinez-Escala ME, Serrano LM, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:828-831. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1264

- Maejima H, Tanei R, Morioka T, et al. Haemophagocytosis-related intravascular large B-cell lymphoma associated with skin eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:339-340. doi:10.2340/00015555-0981

- Mody A, Cherry D, Georgescu G, et al. A rare case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis mimicking cellulitis. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E927142. doi:10.12659/ajcr.927142

- Park YJ, Bae HJ, Chang JY, et al. Development of Kaposi sarcoma and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with human herpesvirus 8 in a renal transplant recipient. Korean J Intern Med. 2017;4:750-752.

- Phatak S, Gupta L, Aggarwal A. A young woman with panniculitis and cytopenia who later developed coagulopathy. J Assoc Physicians India. 2016;64:65-67.

- Pongpairoj K, Rerknimitr P, Wititsuwannakul J, et al. Eruptive telangiectasia in a patient with fever and haemophagocytic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:696-698. doi:10.1111/ced.12859

- Shimizu Y, Tanae K, Takahashi N, et al. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma presenting with hemophagocytic syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2010;34:263-266. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2009.07.001

- Sirka CS, Pradhan S, Patra S, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a rare, potentially fatal complication in subcutaneous panniculitis like T cell lymphoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;5:481-485.

- Chin CK, Hall S, Green C, et al. Secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2019;115: 84-87. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.026

- Dudda M, Mann C, Heinz J, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis of a melanoma patient under BRAF/MEK-inhibitor therapy following anti-PD1 inhibitor treatment: a case report and review to the literature. Melanoma Res. 2021;31:81-84. doi:10.1097 /cmr.0000000000000703

- Mizuta H, Nakano E, Takahashi A, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with advanced malignant melanoma accompanied by ipilimumab and nivolumab: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13321. doi:10.1111/dth.13321

- Satzger I, Ivanyi P, Länger F, et al. Treatment-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to checkpoint inhibition with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. Eur J Cancer. 2018;93:150-153. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2018.01.063

- Michot JM, Lazarovici J, Tieu A, et al. Haematological immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors, how to manage? Eur J Cancer. 2019;122:72-90. doi:10.1016/J.EJCA.2019.07.014

- Choi S, Zhou M, Bahrani E, et al. Rare and fatal complication of immune checkpoint inhibition: a case report of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with severe lichenoid dermatitis. Br J Haematol. 2021;193:e44-e47. doi:10.1111/BJH.17442

- Yang JJ, Lei DK, Ravi V, et al. Overlap between hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and drug reaction and eosinophilia with systemic symptoms: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:925-932. doi:10.1111 /ijd.15196

- Go RS, Wester SM. Immunophenotypic and molecular features, clinical outcomes, treatments, and prognostic factors associated with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: a systematic analysis of 156 patients reported in the literature. Cancer. 2004;101:1404-1413. doi:10.1002/cncr.20502

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening immunologic phenomenon characterized by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome—like clinical picture with additional features, including hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, and increased natural killer cell activity. Clinical manifestations of HLH often are nonspecific, making HLH diagnosis challenging. High persistent fever is a key feature of HLH; patients also may report gastrointestinal distress, lethargy, and/or widespread rash.1

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is believed to stem from inherited defects in several genes, such as perforin (PRF1), as well as immune dysregulation due to infections, rheumatologic diseases, hematologic malignancies, or drug reactions.2 The primary mechanism of HLH is hypothesized to be driven by aberrant immune activation, interferon gamma released from CD8+ T cells, and uncontrolled phagocytosis by activated macrophages. The cytokine cascade results in tissue injury and multiorgan dysfunction.3,4

Although HLH historically has been categorized as primary (familial) or secondary (acquired), the most recent guidelines suggest the etiology is not always binary.3,5 That said, the concept of secondary causes is useful in understanding risk factors for developing HLH. Both forms of the disease are thought to be elicited by a trigger (eg, infection), even when inherited genetic mutations exist.6 The primary form commonly affects the pediatric population,4,6-8 whereas the secondary form is more common in adults.7

Several sets of diagnostic criteria for HLH have been developed, the most well-known being the HLH-2004 criteria.1,3 The HLH-2009 modified criteria were developed after further evidence provided a refined sense of how the HLH-2004 criteria should be stratified.9 Finally, Fardet et al10 presented the HScore as an estimation of likelihood of diagnosis of HLH. These sets of HLH criteria include clinical and laboratory features that demonstrate inflammation, natrual killer cell activity, hemophagocytosis, end-organ damage, and cell lineage effects. The HScore differs from the other sets of HLH criteria in that it is designed to estimate an individual patient’s risk of having reactive hemophagocytic syndrome, which likely is equivalent to secondary HLH, although the authors do not use this exact terminology.10

While these criteria provide a framework for diagnosing HLH, they may fail to distinguish between HLH disease and HLH disease mimics, a concept described by the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis that may impact the success of immunosuppressive treatment.3 Individuals with HLH syndrome meet the aforementioned diagnostic criteria; HLH syndrome is further divided into HLH disease and HLH disease mimics (Figure 1). The “disease” label describes the traditional concept of HLH, driven by aberrant immune overactivation, in which patients benefit from immunosuppression. In contrast, HLH mimics include a subset of patients who meet the HLH criteria but are unlikely to benefit from immunosuppression because the primary mechanism driving their condition is not owed to immune overactivation, as is the case with HLH disease. Examples of HLH mimics include certain infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), that may demonstrate clinical findings consistent with HLH but would not benefit from immunosuppression. Ironically, infections (including EBV) also are known triggers of HLH disease, making this concept difficult to understand and adopt. In this study, we refer to HLH disease simply as HLH.

Although cutaneous manifestations of HLH are not included in the diagnostic criteria, skin findings are common and may coincide with the severity and progression of the disease.11 Despite the fact that HLH can manifest with rash,1 comprehensive reviews of reported cutaneous findings in adult HLH are lacking. Thus, the goal of this study was to provide an organized characterization of reported cutaneous findings in adults with HLH and context for how the dermatologic examination may support the diagnosis or uncover the underlying etiology of this condition.

Methods

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the phrase (cutaneous OR dermatologic OR skin) findings) AND hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis performed on September 20, 2023, yielded 423 results (Figure 2). Filters to exclude non–English language publications and pediatric populations were applied, resulting in 161 articles. Other exclusion criteria included the absence of a description of dermatologic findings. Seventy-five articles remained after screening titles and abstracts, and full-text review yielded 55 articles that were deemed appropriate for inclusion in the study. Subsequent reference searches and use of the online resource Litmaps revealed 45 additional publications that underwent full-text screening; of these articles, 5 were included in the final review.

Results

Sixty studies were included in this systematic review.5,7,11-68 The reported prevalence of skin findings among patients with HLH from the included retrospective studies ranged from 15% to 85%.12-15 Several literature reviews reported similarly varied prevalence among adult patients with HLH.7,16 Fardet et al14 categorized cutaneous manifestations of HLH into 3 types: direct manifestations of HLH not explained by systemic features (eg, generalized maculopapular eruption), indirect manifestations of HLH that are explained by systemic features of the disease (eg, purpura due to HLH-induced coagulopathy), and findings specific to the underlying etiology of HLH (eg, malar rash seen in systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]–associated HLH). This categorization served as the outline for the results below, providing an organized review of cutaneous findings and context for how they may support the diagnosis or uncover the underlying etiology of HLH.

Category I: Direct Manifestations of HLH

Several articles reported cutaneous findings that seemed to be the direct result of HLH and not attributed to an underlying trigger or sequalae of HLH.11,14,16-31 The most common descriptions were a generalized, morbilliform, or nonspecific eruption that encompasses large areas of the skin, commonly the trunk and extremities, sometimes extending to the face and scalp.14,16-23,25,31,32 There were variations in secondary features such as pruritus and tenderness; some studies also described violaceous discoloration in addition to erythema.16,23

Other skin findings thought to be a direct result of HLH were described in detail by Zerah and DeWitt11 in their retrospective study, including pyoderma gangrenosum, panniculitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, atypical targetoid lesions, and bullous eruptions. The authors also analyzed dermatopathologic data that ultimately revealed that pathologic analysis was largely inconsistent and nondescript.11 There was a single case report of purpura fulminans arising alongside signs and symptoms of HLH,26 and several case reports described Sweet syndrome developing around the same time as HLH.27-29 Lastly, Collins et al30 described a case of HLH manifesting with violaceous ulcerating papules and nodules scattered across the legs, abdomen, and arms. Biopsy of this patient’s lesions showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of histiocytes and hemophagocytosis.

Category II: Secondary Complications and Sequelae of HLH

This was the smallest group among the 3 categories, comprising a few case reports and retrospective cohort studies primarily reporting jaundice/icterus and hemorrhagic lesions such as purpura, petechiae, and scleral hemorrhage.11,21,23,33-35 Several literature reviews described these conditions as nonspecific findings in HLH.16,20 The cause of jaundice in HLH likely can be attributed to its characteristic hepatic dysfunction, whereas hemorrhagic lesions likely are the result of both hepatic and bone marrow dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy.

Category III: Manifestations of Underlying Etiology or Triggers of HLH

Infectious—Infection is known to be one of the most common triggers of HLH, with several retrospective studies reporting infectious triggers in approximately 20% of cases.13,15 Although many pathogens have been implicated, only a few of these infection-induced HLH reports described cutaneous findings, which included a case of varicella zoster virus, Escherichia coli necrotizing fasciitis, leprosy, EBV reactivation, parvovirus B19, and both focal and disseminated herpes simplex virus 2.36-42 Most of these patients presented with classic findings of each disease. The case of varicella zoster virus exhibited pruritic erythematous papules on the face, trunk, and limbs.36 The necrotizing fasciitis case presented with tender erythematous swelling of the lower extremity.37 The patient with leprosy exhibited leonine facies and numerous erythematous nodules, plaques, and superficial ulcerating plaques over the trunk and limbs with palmoplantar involvement,39 and both cases of herpes simplex virus 2 reported small bullae either diffusely over the face, trunk, and extremities or over the genitalia.38,40 Interestingly, the cases of parvovirus B19 and EBV reactivation both exhibited polyarteritis nodosa and occurred in patients with underlying autoimmune conditions, raising the question of whether these cases of HLH had a single trigger or were the result of the overall immunologic dysregulation induced by both infection and autoimmunity.41,42

Rheumatologic—Several articles reported dermatologic findings associated with macrophage activation syndrome, a term that often is used to describe HLH associated with autoimmune conditions. Cases of HLH in adult-onset Still disease, dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, and SLE described skin findings characteristic of the underlying rheumatologic disease, sometimes with acutely worse dermatologic findings at the time of HLH presentation.35,41-48 With regard to SLE, the acute manifestation of classic findings of the disease with HLH has sometimes been described as acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS).48 Lambotte at al48 described common findings of acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome in their retrospective study as malar rash, weight loss, polyarthralgia, and nephritis in addition to classic HLH findings including fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Many other rheumatologic conditions have been associated with HLH, including rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren disease. All these conditions can have dermatologic manifestations; however, no descriptions of dermatologic findings in cases of HLH associated with these diseases were found.13

Malignancy—Several cases of malignancy-induced HLH described cutaneous findings, the majority being cutaneous lymphomas, namely subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). Other less commonly reported malignancies in this group included Kaposi sarcoma, intravascular lymphoma, Sézary syndrome, mycosis fungoides, cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and several subtypes of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2,32,49-60 The most common description of SPTCL included multiple scattered plaques and subcutaneous nodules, some associated with tenderness, induration, drainage, or hemorrhagic features.32,50,52,55,57,60 Cases of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome presented with variations in size and distribution of erythroderma with associated lymphadenopathy.2 A unique case of HLH developing in a patient with intravascular lymphoma described an eruption of multiple telangiectasias and petechial hemorrhages on the trunk,58 while one case associated with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma presented with a rapidly enlarging tumor with central ulceration and eschar.59

Drug Induced—Interestingly, most of the drug-induced cases of HLH identified in our search were secondary to biologic therapies used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma, specifically the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have been reported to have an association with HLH in prior literature reviews.61-65 Choi et al66 described an interesting case of ICI-induced HLH presenting with a concurrent severe lichenoid drug eruption that progressed from a pruritic truncal rash to mucocutaneous bullae, erosions, and desquamation resembling a Stevens-Johnson syndrome–type picture. This patient had treatment-refractory, HIV-negative Kaposi sarcoma, where the underlying immunologic dysregulation may explain the more severe cutaneous presentation not observed in other reported cases of ICI-induced HLH.

Yang et al’s67 review of 23 cases with concurrent diagnoses of HLH and DIHS found that 61% (14/23) of cases were diagnosed initially as DIHS before failing treatment and receiving a diagnosis of HLH several weeks later. Additionally, the authors found that several cases met criteria for one diagnosis while clinically presenting strongly for the other.67 This overlap in clinical presentation also was demonstrated in Zerah and DeWitt’s11 retrospective study regarding cutaneous findings in HLH, in which several of the morbilliform eruptions thought to be contributed to HLH ultimately were decided to be drug reactions.

Comment

Regarding direct (or primary) cutaneous findings in HLH (category I), there seem to be 2 groups of features associated with the onset of HLH that are not related to its characteristic hepatic dysfunction (category II) nor its underlying triggers (category III): a nonspecific, generalized, erythematous eruption; and dermatologic conditions separate from HLH itself (eg, Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum). Whether the latter group truly is a direct manifestation of HLH is difficult to discern with the evidence available. Nevertheless, we can conclude that there is some type of association between these dermatologic diseases and HLH, and this association can serve as both a diagnostic tool for clinicians and a point of interest for further clinical research.

The relatively low number of articles identified through our systematic review that specifically reported secondary findings, such as jaundice or coagulopathy-associated hemorrhagic lesions, may lead one to believe that these are not common findings in HLH; however, it is possible that these are not regularly reported in the literature simply because these findings are nonspecific and can be considered expected results of the characteristic organ dysfunction in HLH.

As suspected, the skin findings in category III were the most broad given the variety of underlying etiologies that have been associated with HLH. Like the other 2 categories, these skin findings generally are nonspecific to HLH; however, the ones in category III are specific to underlying etiology of HLH and may aid in identifying and treating the underlying cause of a patient’s HLH when indicated.

Most of the rheumatologic diseases seem to have been known at the time of HLH development and diagnosis, which may highlight the importance of considering a diagnosis of HLH early on in patients with known autoimmune disease and systemic signs of illness or acutely worsening signs and symptoms of their underlying autoimmune disease.

Interestingly, several cases of malignancy-associated HLH reported signs and symptoms of HLH at initial presentation of the malignant disease.32,50,59 This situation seems to be somewhat common, as Go and Wester’s68 systematic analysis of 156 patients with SPTCL found HLH was the presenting feature in 37% of patients included in their study. This may call attention to the importance of considering cutaneous lymphomas as the cause of skin lesions in patients with signs and symptoms of HLH, where it may be easy to assume that skin findings are a result of their systemic disease.

In highlighting cases of HLH related to medication use, we found it pertinent to include and discuss the complex relationship between drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS [formerly known as drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS] syndrome) and HLH. The results of this study suggest that DIHS may have considerable clinical overlap with HLH11 and may even lead to development of HLH,67 creating difficulty in distinguishing between these conditions where there may be similar findings, such as cutaneous eruptions, fever, and hepatic or other internal organ involvement. We agree with Yang et al67 that there can be large overlap in symptomology between these two conditions and that more investigation is necessary to explore the relationship between them.

Conclusion

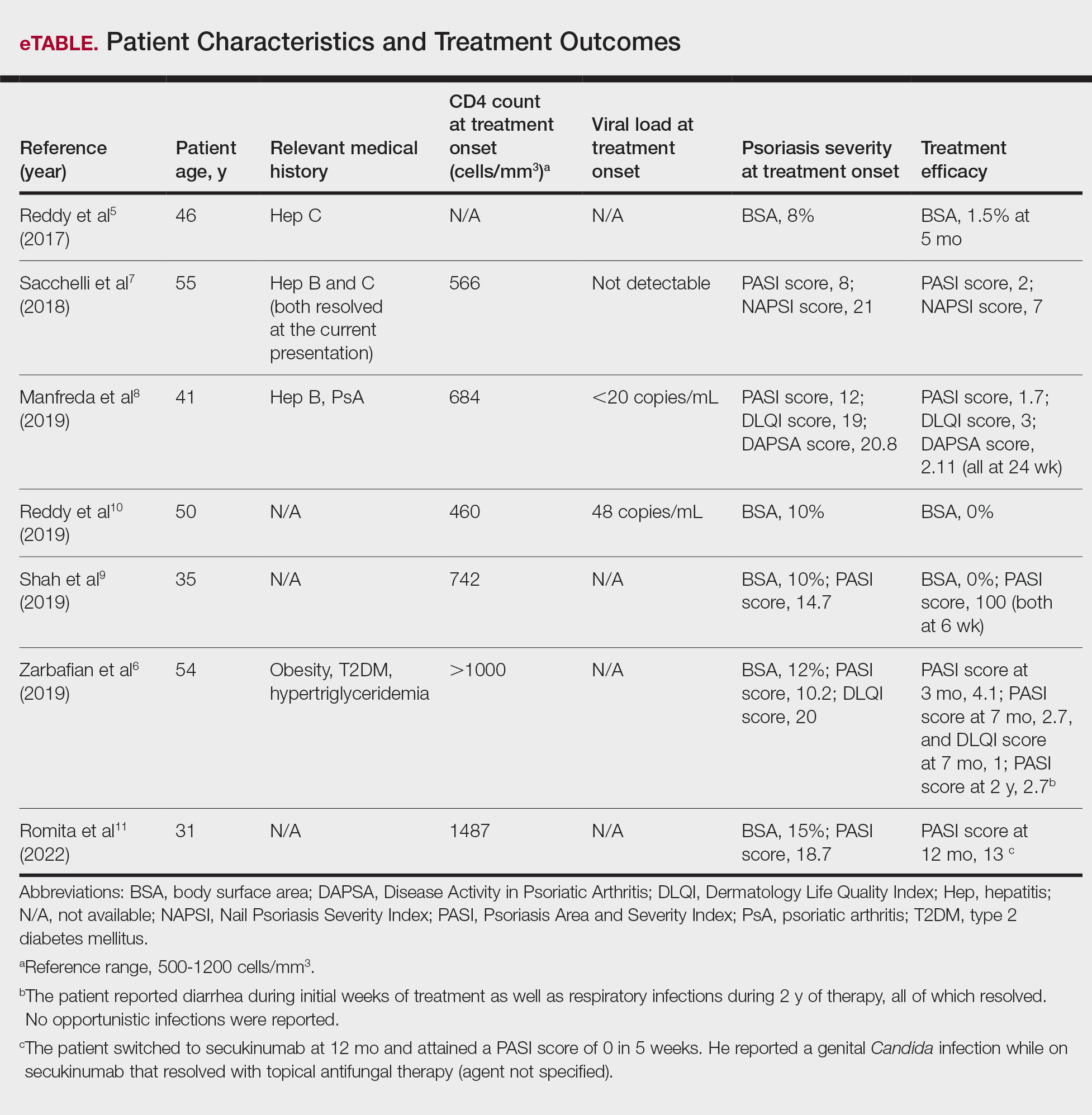

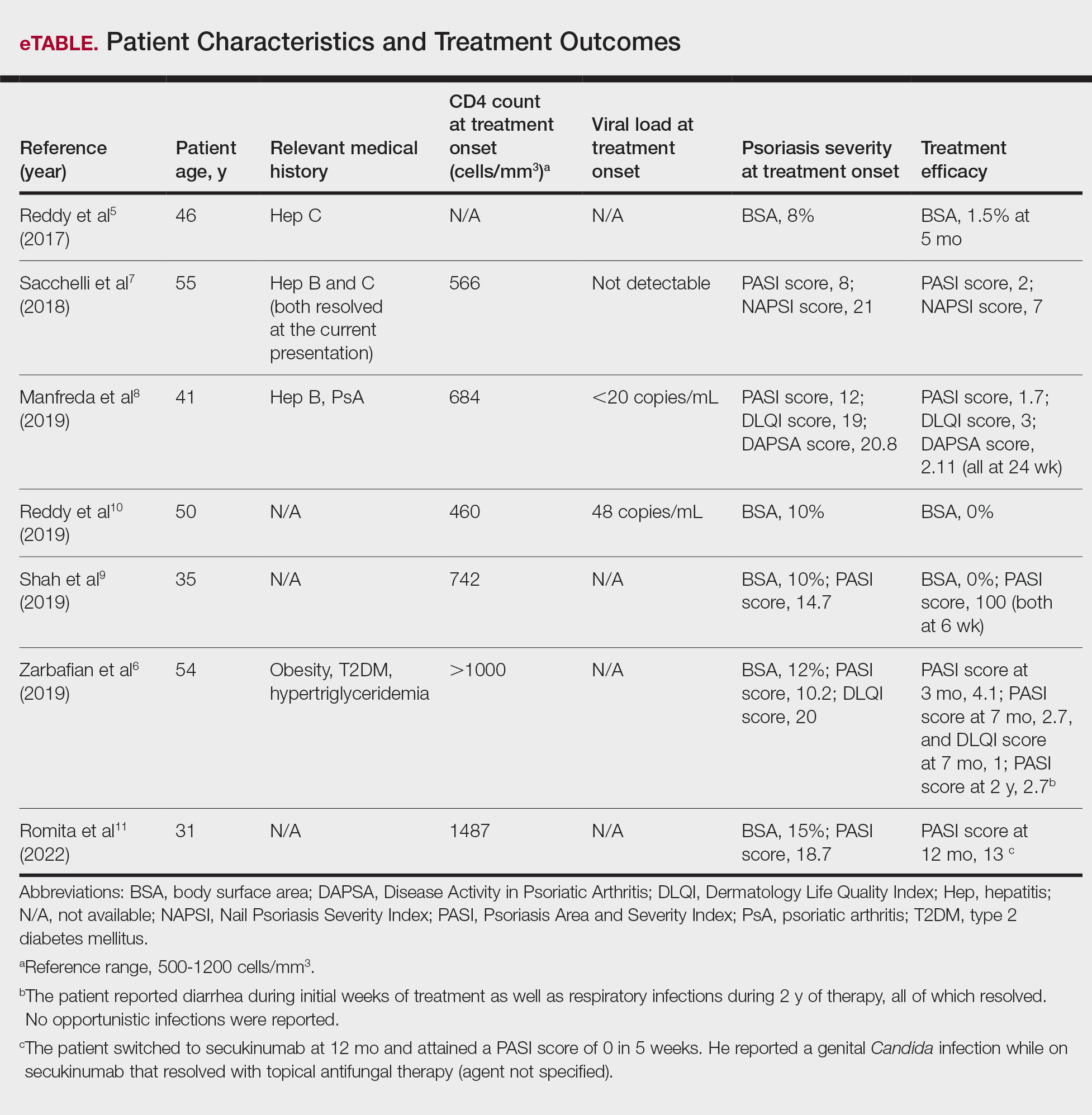

Diagnosis of HLH in adults continues to be challenging, with several diagnostic tools but no true gold standard. In addition to the nonspecific symptomology, there is a myriad of cutaneous findings that can be present in adults with HLH (eTable), all of which are also nonspecific. Even so, awareness of which dermatologic findings have been associated with HLH may provide a cue to consider HLH in the systemically ill patient with a notable dermatologic examination. Furthermore, there are several avenues for further investigation that can be drawn, including further dermatologic analysis among nonspecific eruptions attributed to HLH, clinical and pathologic differentiation between DIHS/DRESS and HLH, and correlation between severity of skin manifestations and severity of HLH disease.

Limitations of this study included a lack of clarity in diagnosis of HLH in patients described in the included articles, as some reports use variable terminology (HLH vs hemophagocytic syndrome vs macrophage activation syndrome, etc), and it is impossible to know if all authors used the same diagnostic criteria—or any validated diagnostic criteria—unless specifically stated. Additionally, including case reports in our study limited the amount and quality of information described in each report. Despite its limitations, this systematic review outlines the cutaneous manifestations associated with HLH. These data will promote clinical awareness of this complex condition and allow for consideration of HLH in patients meeting criteria for HLH syndrome. More studies ultimately are needed to differentiate HLH from its mimics.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening immunologic phenomenon characterized by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome—like clinical picture with additional features, including hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, and increased natural killer cell activity. Clinical manifestations of HLH often are nonspecific, making HLH diagnosis challenging. High persistent fever is a key feature of HLH; patients also may report gastrointestinal distress, lethargy, and/or widespread rash.1

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is believed to stem from inherited defects in several genes, such as perforin (PRF1), as well as immune dysregulation due to infections, rheumatologic diseases, hematologic malignancies, or drug reactions.2 The primary mechanism of HLH is hypothesized to be driven by aberrant immune activation, interferon gamma released from CD8+ T cells, and uncontrolled phagocytosis by activated macrophages. The cytokine cascade results in tissue injury and multiorgan dysfunction.3,4

Although HLH historically has been categorized as primary (familial) or secondary (acquired), the most recent guidelines suggest the etiology is not always binary.3,5 That said, the concept of secondary causes is useful in understanding risk factors for developing HLH. Both forms of the disease are thought to be elicited by a trigger (eg, infection), even when inherited genetic mutations exist.6 The primary form commonly affects the pediatric population,4,6-8 whereas the secondary form is more common in adults.7

Several sets of diagnostic criteria for HLH have been developed, the most well-known being the HLH-2004 criteria.1,3 The HLH-2009 modified criteria were developed after further evidence provided a refined sense of how the HLH-2004 criteria should be stratified.9 Finally, Fardet et al10 presented the HScore as an estimation of likelihood of diagnosis of HLH. These sets of HLH criteria include clinical and laboratory features that demonstrate inflammation, natrual killer cell activity, hemophagocytosis, end-organ damage, and cell lineage effects. The HScore differs from the other sets of HLH criteria in that it is designed to estimate an individual patient’s risk of having reactive hemophagocytic syndrome, which likely is equivalent to secondary HLH, although the authors do not use this exact terminology.10

While these criteria provide a framework for diagnosing HLH, they may fail to distinguish between HLH disease and HLH disease mimics, a concept described by the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis that may impact the success of immunosuppressive treatment.3 Individuals with HLH syndrome meet the aforementioned diagnostic criteria; HLH syndrome is further divided into HLH disease and HLH disease mimics (Figure 1). The “disease” label describes the traditional concept of HLH, driven by aberrant immune overactivation, in which patients benefit from immunosuppression. In contrast, HLH mimics include a subset of patients who meet the HLH criteria but are unlikely to benefit from immunosuppression because the primary mechanism driving their condition is not owed to immune overactivation, as is the case with HLH disease. Examples of HLH mimics include certain infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), that may demonstrate clinical findings consistent with HLH but would not benefit from immunosuppression. Ironically, infections (including EBV) also are known triggers of HLH disease, making this concept difficult to understand and adopt. In this study, we refer to HLH disease simply as HLH.

Although cutaneous manifestations of HLH are not included in the diagnostic criteria, skin findings are common and may coincide with the severity and progression of the disease.11 Despite the fact that HLH can manifest with rash,1 comprehensive reviews of reported cutaneous findings in adult HLH are lacking. Thus, the goal of this study was to provide an organized characterization of reported cutaneous findings in adults with HLH and context for how the dermatologic examination may support the diagnosis or uncover the underlying etiology of this condition.

Methods

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the phrase (cutaneous OR dermatologic OR skin) findings) AND hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis performed on September 20, 2023, yielded 423 results (Figure 2). Filters to exclude non–English language publications and pediatric populations were applied, resulting in 161 articles. Other exclusion criteria included the absence of a description of dermatologic findings. Seventy-five articles remained after screening titles and abstracts, and full-text review yielded 55 articles that were deemed appropriate for inclusion in the study. Subsequent reference searches and use of the online resource Litmaps revealed 45 additional publications that underwent full-text screening; of these articles, 5 were included in the final review.

Results

Sixty studies were included in this systematic review.5,7,11-68 The reported prevalence of skin findings among patients with HLH from the included retrospective studies ranged from 15% to 85%.12-15 Several literature reviews reported similarly varied prevalence among adult patients with HLH.7,16 Fardet et al14 categorized cutaneous manifestations of HLH into 3 types: direct manifestations of HLH not explained by systemic features (eg, generalized maculopapular eruption), indirect manifestations of HLH that are explained by systemic features of the disease (eg, purpura due to HLH-induced coagulopathy), and findings specific to the underlying etiology of HLH (eg, malar rash seen in systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]–associated HLH). This categorization served as the outline for the results below, providing an organized review of cutaneous findings and context for how they may support the diagnosis or uncover the underlying etiology of HLH.

Category I: Direct Manifestations of HLH

Several articles reported cutaneous findings that seemed to be the direct result of HLH and not attributed to an underlying trigger or sequalae of HLH.11,14,16-31 The most common descriptions were a generalized, morbilliform, or nonspecific eruption that encompasses large areas of the skin, commonly the trunk and extremities, sometimes extending to the face and scalp.14,16-23,25,31,32 There were variations in secondary features such as pruritus and tenderness; some studies also described violaceous discoloration in addition to erythema.16,23

Other skin findings thought to be a direct result of HLH were described in detail by Zerah and DeWitt11 in their retrospective study, including pyoderma gangrenosum, panniculitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, atypical targetoid lesions, and bullous eruptions. The authors also analyzed dermatopathologic data that ultimately revealed that pathologic analysis was largely inconsistent and nondescript.11 There was a single case report of purpura fulminans arising alongside signs and symptoms of HLH,26 and several case reports described Sweet syndrome developing around the same time as HLH.27-29 Lastly, Collins et al30 described a case of HLH manifesting with violaceous ulcerating papules and nodules scattered across the legs, abdomen, and arms. Biopsy of this patient’s lesions showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of histiocytes and hemophagocytosis.

Category II: Secondary Complications and Sequelae of HLH

This was the smallest group among the 3 categories, comprising a few case reports and retrospective cohort studies primarily reporting jaundice/icterus and hemorrhagic lesions such as purpura, petechiae, and scleral hemorrhage.11,21,23,33-35 Several literature reviews described these conditions as nonspecific findings in HLH.16,20 The cause of jaundice in HLH likely can be attributed to its characteristic hepatic dysfunction, whereas hemorrhagic lesions likely are the result of both hepatic and bone marrow dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy.

Category III: Manifestations of Underlying Etiology or Triggers of HLH

Infectious—Infection is known to be one of the most common triggers of HLH, with several retrospective studies reporting infectious triggers in approximately 20% of cases.13,15 Although many pathogens have been implicated, only a few of these infection-induced HLH reports described cutaneous findings, which included a case of varicella zoster virus, Escherichia coli necrotizing fasciitis, leprosy, EBV reactivation, parvovirus B19, and both focal and disseminated herpes simplex virus 2.36-42 Most of these patients presented with classic findings of each disease. The case of varicella zoster virus exhibited pruritic erythematous papules on the face, trunk, and limbs.36 The necrotizing fasciitis case presented with tender erythematous swelling of the lower extremity.37 The patient with leprosy exhibited leonine facies and numerous erythematous nodules, plaques, and superficial ulcerating plaques over the trunk and limbs with palmoplantar involvement,39 and both cases of herpes simplex virus 2 reported small bullae either diffusely over the face, trunk, and extremities or over the genitalia.38,40 Interestingly, the cases of parvovirus B19 and EBV reactivation both exhibited polyarteritis nodosa and occurred in patients with underlying autoimmune conditions, raising the question of whether these cases of HLH had a single trigger or were the result of the overall immunologic dysregulation induced by both infection and autoimmunity.41,42

Rheumatologic—Several articles reported dermatologic findings associated with macrophage activation syndrome, a term that often is used to describe HLH associated with autoimmune conditions. Cases of HLH in adult-onset Still disease, dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, and SLE described skin findings characteristic of the underlying rheumatologic disease, sometimes with acutely worse dermatologic findings at the time of HLH presentation.35,41-48 With regard to SLE, the acute manifestation of classic findings of the disease with HLH has sometimes been described as acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS).48 Lambotte at al48 described common findings of acute lupus hemophagocytic syndrome in their retrospective study as malar rash, weight loss, polyarthralgia, and nephritis in addition to classic HLH findings including fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Many other rheumatologic conditions have been associated with HLH, including rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren disease. All these conditions can have dermatologic manifestations; however, no descriptions of dermatologic findings in cases of HLH associated with these diseases were found.13

Malignancy—Several cases of malignancy-induced HLH described cutaneous findings, the majority being cutaneous lymphomas, namely subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). Other less commonly reported malignancies in this group included Kaposi sarcoma, intravascular lymphoma, Sézary syndrome, mycosis fungoides, cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and several subtypes of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2,32,49-60 The most common description of SPTCL included multiple scattered plaques and subcutaneous nodules, some associated with tenderness, induration, drainage, or hemorrhagic features.32,50,52,55,57,60 Cases of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome presented with variations in size and distribution of erythroderma with associated lymphadenopathy.2 A unique case of HLH developing in a patient with intravascular lymphoma described an eruption of multiple telangiectasias and petechial hemorrhages on the trunk,58 while one case associated with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma presented with a rapidly enlarging tumor with central ulceration and eschar.59

Drug Induced—Interestingly, most of the drug-induced cases of HLH identified in our search were secondary to biologic therapies used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma, specifically the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have been reported to have an association with HLH in prior literature reviews.61-65 Choi et al66 described an interesting case of ICI-induced HLH presenting with a concurrent severe lichenoid drug eruption that progressed from a pruritic truncal rash to mucocutaneous bullae, erosions, and desquamation resembling a Stevens-Johnson syndrome–type picture. This patient had treatment-refractory, HIV-negative Kaposi sarcoma, where the underlying immunologic dysregulation may explain the more severe cutaneous presentation not observed in other reported cases of ICI-induced HLH.

Yang et al’s67 review of 23 cases with concurrent diagnoses of HLH and DIHS found that 61% (14/23) of cases were diagnosed initially as DIHS before failing treatment and receiving a diagnosis of HLH several weeks later. Additionally, the authors found that several cases met criteria for one diagnosis while clinically presenting strongly for the other.67 This overlap in clinical presentation also was demonstrated in Zerah and DeWitt’s11 retrospective study regarding cutaneous findings in HLH, in which several of the morbilliform eruptions thought to be contributed to HLH ultimately were decided to be drug reactions.

Comment

Regarding direct (or primary) cutaneous findings in HLH (category I), there seem to be 2 groups of features associated with the onset of HLH that are not related to its characteristic hepatic dysfunction (category II) nor its underlying triggers (category III): a nonspecific, generalized, erythematous eruption; and dermatologic conditions separate from HLH itself (eg, Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum). Whether the latter group truly is a direct manifestation of HLH is difficult to discern with the evidence available. Nevertheless, we can conclude that there is some type of association between these dermatologic diseases and HLH, and this association can serve as both a diagnostic tool for clinicians and a point of interest for further clinical research.

The relatively low number of articles identified through our systematic review that specifically reported secondary findings, such as jaundice or coagulopathy-associated hemorrhagic lesions, may lead one to believe that these are not common findings in HLH; however, it is possible that these are not regularly reported in the literature simply because these findings are nonspecific and can be considered expected results of the characteristic organ dysfunction in HLH.

As suspected, the skin findings in category III were the most broad given the variety of underlying etiologies that have been associated with HLH. Like the other 2 categories, these skin findings generally are nonspecific to HLH; however, the ones in category III are specific to underlying etiology of HLH and may aid in identifying and treating the underlying cause of a patient’s HLH when indicated.

Most of the rheumatologic diseases seem to have been known at the time of HLH development and diagnosis, which may highlight the importance of considering a diagnosis of HLH early on in patients with known autoimmune disease and systemic signs of illness or acutely worsening signs and symptoms of their underlying autoimmune disease.

Interestingly, several cases of malignancy-associated HLH reported signs and symptoms of HLH at initial presentation of the malignant disease.32,50,59 This situation seems to be somewhat common, as Go and Wester’s68 systematic analysis of 156 patients with SPTCL found HLH was the presenting feature in 37% of patients included in their study. This may call attention to the importance of considering cutaneous lymphomas as the cause of skin lesions in patients with signs and symptoms of HLH, where it may be easy to assume that skin findings are a result of their systemic disease.

In highlighting cases of HLH related to medication use, we found it pertinent to include and discuss the complex relationship between drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS [formerly known as drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS] syndrome) and HLH. The results of this study suggest that DIHS may have considerable clinical overlap with HLH11 and may even lead to development of HLH,67 creating difficulty in distinguishing between these conditions where there may be similar findings, such as cutaneous eruptions, fever, and hepatic or other internal organ involvement. We agree with Yang et al67 that there can be large overlap in symptomology between these two conditions and that more investigation is necessary to explore the relationship between them.

Conclusion

Diagnosis of HLH in adults continues to be challenging, with several diagnostic tools but no true gold standard. In addition to the nonspecific symptomology, there is a myriad of cutaneous findings that can be present in adults with HLH (eTable), all of which are also nonspecific. Even so, awareness of which dermatologic findings have been associated with HLH may provide a cue to consider HLH in the systemically ill patient with a notable dermatologic examination. Furthermore, there are several avenues for further investigation that can be drawn, including further dermatologic analysis among nonspecific eruptions attributed to HLH, clinical and pathologic differentiation between DIHS/DRESS and HLH, and correlation between severity of skin manifestations and severity of HLH disease.

Limitations of this study included a lack of clarity in diagnosis of HLH in patients described in the included articles, as some reports use variable terminology (HLH vs hemophagocytic syndrome vs macrophage activation syndrome, etc), and it is impossible to know if all authors used the same diagnostic criteria—or any validated diagnostic criteria—unless specifically stated. Additionally, including case reports in our study limited the amount and quality of information described in each report. Despite its limitations, this systematic review outlines the cutaneous manifestations associated with HLH. These data will promote clinical awareness of this complex condition and allow for consideration of HLH in patients meeting criteria for HLH syndrome. More studies ultimately are needed to differentiate HLH from its mimics.

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

- Blom A, Beylot-Barry M, D’Incan M, et al. Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (LAHS) in advanced-stage mycosis fungoides/ Sézary syndrome cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:404-410. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.029

- Jordan MB, Allen CE, Greenberg J, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27929. doi:10.1002/pbc.27929

- Griffin G, Shenoi S, Hughes GC. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;34:101515. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101515

- Tomasini D, Berti E. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:395-411.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61048-x

- Sieni E, Cetica V, Piccin A, et al. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis may present during adulthood: clinical and genetic features of a small series. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44649. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044649

- Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology. 2009:127-131. doi:10.1182 /asheducation-2009.1.127

- Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2613-2620. doi:10.1002/art.38690

- Zerah ML, DeWitt CA. Cutaneous findings in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Dermatology. 2015;230:234-243. doi:10.1159/000368552

- Fardet L, Galicier L, Vignon-Pennamen MD, et al. Frequency, clinical features and prognosis of cutaneous manifestations in adult patients with reactive haemophagocytic syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:547-553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09549.x

- Dhote R, Simon J, Papo T, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult systemic disease: report of twenty-six cases and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:633-639. doi:10.1002/art.11368

- Li J, Wang Q, Zheng W, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical analysis of 103 adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:100-105. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000000022

- Tudesq JJ, Valade S, Galicier L, et al. Diagnostic strategy for trigger identification in severe reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a diagnostic accuracy study. Hematol Oncol. 2021;39:114-122. doi:10.1002 /hon.2819

- Sakai H, Otsubo S, Miura T, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome presenting with a facial erythema in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 Suppl):S111-S114. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2006.11.024

- Chung SM, Song JY, Kim W, et al. Dengue-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in an adult: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6159. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000006159

- Esmaili H, Rahmani O, Fouladi RF. Hemophagocytic syndrome in patients with unexplained cytopenia: report of 15 cases. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2013;29:15-18. doi:10.5146/tjpath.2013.01142

- Jiwnani S, Karimundackal G, Kulkarni A, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome complicating lung resection. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2012;20:341-343. doi:10.1177/0218492311435686

- Lee WJ, Lee DW, Kim CH, et al. Dermatopathic lymphadenitis with generalized erythroderma in a patient with Epstein-Barr virusassociated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:357-361. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b2a50f

- Lovisari F, Terzi V, Lippi MG, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicated by multiorgan failure: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9198. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000009198

- Miechowiecki J, Stainer W, Wallner G, et al. Severe complication during remission of Crohn’s disease: hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to acute cytomegalovirus infection. Z Gastroenterol. 2018;56:259-263. doi:10.1055/s-0043-123999

- Ochoa S, Cheng K, Fleury CM, et al. A 28-year-old woman with fever, rash, and pancytopenia. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38:322-327. doi:10.2500/aap.2017.38.4042

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Miura K, et al. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection with cutaneous lymphoproliferation: haemophagocytosis in the skin and haemophagocytic syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e116-e117. doi:10.1111/jdv.14640

- Tzeng HE, Teng CL, Yang Y, et al. Occult subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma with initial presentations of cellulitis-like skin lesion and fulminant hemophagocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106 (2 Suppl):S55-S59. doi:10.1016/s0929-6646(09)60354-5

- Honjo O, Kubo T, Sugaya F, et al. Severe cytokine release syndrome resulting in purpura fulminans despite successful response to nivolumab therapy in a patient with pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung: a case report. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:97. doi:10.1186/s40425- 019-0582-4

- Kao RL, Jacobsen AA, Billington CJ Jr, et al. A case of VEXAS syndrome associated with EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2022;93:102636. doi:10.1016/j .bcmd.2021.102636

- Koga T, Takano K, Horai Y, et al. Sweet’s syndrome complicated by Kikuchi’s disease and hemophagocytic syndrome which presented with retinoic acid-inducible gene-I in both the skin epidermal basal layer and the cervical lymph nodes. Intern Med. 2013;52:1839-1843. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.52.9542

- Lin WL, Lin WC, Chiu CS, et al. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2008;3:305-307.

- Collins MK, Ho J, Akilov OE. Case 52. A unique presentation of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with ulcerating papulonodules. In: Akilov OE, ed. Cutaneous Lymphomas: Unusual Cases 3. Springer International Publishing; 2021:126-127.

- Chakrapani A, Avery A, Warnke R. Primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma with brain involvement and hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:270-272. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3182624e98

- Sullivan C, Loghmani A, Thomas K, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as the initial presentation of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: a rare case responding to cyclosporine A and steroids. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620981531. doi:10.1177/2324709620981531

- Darmawan G, Salido EO, Concepcion ML, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: “a dreadful mimic.” Int J Rheum Dis. 2015; 18:810-812. doi:10.1111/1756-185x.12506

- Maus MV, Leick MB, Cornejo KM, et al. Case 35-2019: a 66-year-old man with pancytopenia and rash. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1951-1960. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1909627

- Chamseddin B, Marks E, Dominguez A, et al. Refractory macrophage activation syndrome in the setting of adult-onset Still disease with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis detected on skin biopsy treated with canakinumab and tacrolimus. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:528-531. doi:10.1111/cup.13466

- Bérar A, Ardois S, Walter-Moraux P, et al. Primary varicella-zoster virus infection of the immunocompromised associated with acute pancreatitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25351. doi:10.1097 /md.0000000000025351

- Chang CC, Hsiao PJ, Chiu CC, et al. Catastrophic hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a young man with nephrotic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;439:168-171. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.025

- Kurosawa S, Sekiya N, Fukushima K, et al. Unusual manifestation of disseminated herpes simplex virus type 2 infection associated with pharyngotonsilitis, esophagitis, and hemophagocytic lymphohisitocytosis without genital involvement. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:65. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3721-0

- Saidi W, Gammoudi R, Korbi M, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an unusual complication of leprosy. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54: 1054-1059. doi:10.1111/ijd.12792

- Yamaguchi K, Yamamoto A, Hisano M, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a pregnant patient. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 2):1241-1244. doi:10.1097 /01.AOG.0000157757.54948.9b