User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Why 9 is not too young for the HPV vaccine

For Sonja O’Leary, MD, higher rates of vaccination against human papillomavirus came with the flip of a switch.

Dr. O’Leary, the interim director of service for outpatient pediatric services at Denver Health and Hospital Authority, and her colleagues saw rates of HPV and other childhood immunizations drop during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to act. Their health system, which includes 28 federally qualified health centers, offers vaccines at any inpatient or outpatient visit based on alerts from their electronic health record.

“It was actually really simple; it was really just changing our best-practice alert,” Dr. O’Leary said. Beginning in May 2021, and after notifying clinic staff of the impending change, DHHA dropped the alert for first dose of HPV from age 11 to 9.

The approach worked. Compared with the first 5 months of 2021, the percentage of children aged 9-13 years with an in-person visit who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine between June 2021 and August 2022 rose from 30.3% to 42.8% – a 41% increase. The share who received two doses by age 13 years more than doubled, from 19.3% to 42.7%, Dr. O’Leary said.

Frustrated efforts

Although those figures might seem to make an iron-clad case for earlier vaccinations against HPV – which is responsible for nearly 35,000 cases of cancer annually – factors beyond statistics have frustrated efforts to increase acceptance of the shots.

Data published in 2022 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 89.6% of teens aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 89% got one or more doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccine. However, only 76.9% had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. The rate of receiving both doses needed for full protection was much lower (61.7%).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society now endorse the strategy of offering HPV vaccine as early as age 9, which avoids the need for multiple shots at a single visit and results in more kids getting both doses. In a recent study that surveyed primary care professionals who see pediatric patients, 21% were already offering HPV vaccine at age 9, and another 48% were willing to try the approach.

What was the most common objection to the earlier age? Nearly three-quarters of clinicians said they felt that parents weren’t ready to talk about HPV vaccination yet.

Noel Brewer, PhD, one of the authors of the survey study, wondered why clinicians feel the need to bring up sex at all. “Providers should never be talking about sex when they are talking about vaccine, because that’s not the point,” said Dr. Brewer, the distinguished professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He pointed out that providers don’t talk about the route of transmission for any other vaccine.

Dr. Brewer led a randomized controlled trial that trained pediatric clinicians in the “announcement” strategy, in which the clinician announces the vaccines that are due at that visit. If the parent hesitates, the clinician then probes further to identify and address their concerns and provides more information. If the parent is still not convinced, the clinician notes the discussion in the chart and tries again at the next visit.

The strategy was effective: Intervention clinics had a 5.4% higher rate of HPV vaccination coverage than control clinics after six months. Dr. Brewer and his colleagues have trained over 1,700 providers in the technique since 2020.

A cancer – not STI – vaccine

Although DHHA hasn’t participated in Dr. Brewer’s training, Dr. O’Leary and her colleagues take a similar approach of simply stating which vaccines the child should receive that day. And they talk about HPV as a cancer vaccine instead of one to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.

In her experience, this emphasis changes the conversation. Dr. O’Leary described a typical comment from parents as, “Oh, of course I would give my child a vaccine that could prevent cancer.”

Ana Rodriguez, MD, MPH, an obstetrician, became interested in raising rates of vaccination against HPV after watching too many women battle a preventable cancer. She worked for several years in the Rio Grande Valley along the U.S. border with Mexico, an impoverished rural area with poor access to health care and high rates of HPV infection.

“I would treat women very young – not even 30 years of age – already fighting advanced precancerous lesions secondary to HPV,” said Dr. Rodriguez, an associate professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

In 2016, when Texas ranked 47th in the nation for rates of up-to-date HPV vaccination, Dr. Rodriguez helped launch a community-based educational campaign in four rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley using social media, radio, and in-person meetings with school PTA members and members of school boards to educate staff and parents about the need for vaccination against the infection.

In 2019, the team began offering the vaccine to children ages 9-12 years at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and other school events, pivoting to outdoor events using a mobile vaccine van after COVID-19 struck. They recently published a study showing that 73.6% of students who received their first dose of vaccine at age 11 or younger completed the series, compared with only 45.1% of children who got their first dose at age 12 or older.

Dr. Rodriguez encountered parents who felt 9 or 10 years old was too young because their children were not going to be sexually active anytime soon. Her response was to describe HPV as a tool to prevent cancer, telling parents, “If you vaccinate your kids young enough, they will be protected for life.”

Lifetime protection is another point in favor of giving HPV vaccine prior to Tdap and MenACWY. The response to the two-dose series of HPV in preadolescents is robust and long-lasting, with no downside to giving it a few years earlier. In contrast, immunity to MenACWY wanes after a few years, so the immunization must be given before children enter high school, when their risk for meningitis increases.

The annual toll of deaths in the United States from meningococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis typically totals less than 100, whereas cancer deaths attributable to HPV infection number in the thousands each year. And that may be the best reason for attempting new strategies to help HPV vaccination rates catch up to the rest of the preteen vaccines.

Dr. Brewer’s work was supported by the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, and from training grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brewer has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and served as a paid advisor for Merck. Dr. O’Leary reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rodriguez received a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For Sonja O’Leary, MD, higher rates of vaccination against human papillomavirus came with the flip of a switch.

Dr. O’Leary, the interim director of service for outpatient pediatric services at Denver Health and Hospital Authority, and her colleagues saw rates of HPV and other childhood immunizations drop during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to act. Their health system, which includes 28 federally qualified health centers, offers vaccines at any inpatient or outpatient visit based on alerts from their electronic health record.

“It was actually really simple; it was really just changing our best-practice alert,” Dr. O’Leary said. Beginning in May 2021, and after notifying clinic staff of the impending change, DHHA dropped the alert for first dose of HPV from age 11 to 9.

The approach worked. Compared with the first 5 months of 2021, the percentage of children aged 9-13 years with an in-person visit who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine between June 2021 and August 2022 rose from 30.3% to 42.8% – a 41% increase. The share who received two doses by age 13 years more than doubled, from 19.3% to 42.7%, Dr. O’Leary said.

Frustrated efforts

Although those figures might seem to make an iron-clad case for earlier vaccinations against HPV – which is responsible for nearly 35,000 cases of cancer annually – factors beyond statistics have frustrated efforts to increase acceptance of the shots.

Data published in 2022 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 89.6% of teens aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 89% got one or more doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccine. However, only 76.9% had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. The rate of receiving both doses needed for full protection was much lower (61.7%).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society now endorse the strategy of offering HPV vaccine as early as age 9, which avoids the need for multiple shots at a single visit and results in more kids getting both doses. In a recent study that surveyed primary care professionals who see pediatric patients, 21% were already offering HPV vaccine at age 9, and another 48% were willing to try the approach.

What was the most common objection to the earlier age? Nearly three-quarters of clinicians said they felt that parents weren’t ready to talk about HPV vaccination yet.

Noel Brewer, PhD, one of the authors of the survey study, wondered why clinicians feel the need to bring up sex at all. “Providers should never be talking about sex when they are talking about vaccine, because that’s not the point,” said Dr. Brewer, the distinguished professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He pointed out that providers don’t talk about the route of transmission for any other vaccine.

Dr. Brewer led a randomized controlled trial that trained pediatric clinicians in the “announcement” strategy, in which the clinician announces the vaccines that are due at that visit. If the parent hesitates, the clinician then probes further to identify and address their concerns and provides more information. If the parent is still not convinced, the clinician notes the discussion in the chart and tries again at the next visit.

The strategy was effective: Intervention clinics had a 5.4% higher rate of HPV vaccination coverage than control clinics after six months. Dr. Brewer and his colleagues have trained over 1,700 providers in the technique since 2020.

A cancer – not STI – vaccine

Although DHHA hasn’t participated in Dr. Brewer’s training, Dr. O’Leary and her colleagues take a similar approach of simply stating which vaccines the child should receive that day. And they talk about HPV as a cancer vaccine instead of one to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.

In her experience, this emphasis changes the conversation. Dr. O’Leary described a typical comment from parents as, “Oh, of course I would give my child a vaccine that could prevent cancer.”

Ana Rodriguez, MD, MPH, an obstetrician, became interested in raising rates of vaccination against HPV after watching too many women battle a preventable cancer. She worked for several years in the Rio Grande Valley along the U.S. border with Mexico, an impoverished rural area with poor access to health care and high rates of HPV infection.

“I would treat women very young – not even 30 years of age – already fighting advanced precancerous lesions secondary to HPV,” said Dr. Rodriguez, an associate professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

In 2016, when Texas ranked 47th in the nation for rates of up-to-date HPV vaccination, Dr. Rodriguez helped launch a community-based educational campaign in four rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley using social media, radio, and in-person meetings with school PTA members and members of school boards to educate staff and parents about the need for vaccination against the infection.

In 2019, the team began offering the vaccine to children ages 9-12 years at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and other school events, pivoting to outdoor events using a mobile vaccine van after COVID-19 struck. They recently published a study showing that 73.6% of students who received their first dose of vaccine at age 11 or younger completed the series, compared with only 45.1% of children who got their first dose at age 12 or older.

Dr. Rodriguez encountered parents who felt 9 or 10 years old was too young because their children were not going to be sexually active anytime soon. Her response was to describe HPV as a tool to prevent cancer, telling parents, “If you vaccinate your kids young enough, they will be protected for life.”

Lifetime protection is another point in favor of giving HPV vaccine prior to Tdap and MenACWY. The response to the two-dose series of HPV in preadolescents is robust and long-lasting, with no downside to giving it a few years earlier. In contrast, immunity to MenACWY wanes after a few years, so the immunization must be given before children enter high school, when their risk for meningitis increases.

The annual toll of deaths in the United States from meningococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis typically totals less than 100, whereas cancer deaths attributable to HPV infection number in the thousands each year. And that may be the best reason for attempting new strategies to help HPV vaccination rates catch up to the rest of the preteen vaccines.

Dr. Brewer’s work was supported by the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, and from training grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brewer has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and served as a paid advisor for Merck. Dr. O’Leary reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rodriguez received a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For Sonja O’Leary, MD, higher rates of vaccination against human papillomavirus came with the flip of a switch.

Dr. O’Leary, the interim director of service for outpatient pediatric services at Denver Health and Hospital Authority, and her colleagues saw rates of HPV and other childhood immunizations drop during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to act. Their health system, which includes 28 federally qualified health centers, offers vaccines at any inpatient or outpatient visit based on alerts from their electronic health record.

“It was actually really simple; it was really just changing our best-practice alert,” Dr. O’Leary said. Beginning in May 2021, and after notifying clinic staff of the impending change, DHHA dropped the alert for first dose of HPV from age 11 to 9.

The approach worked. Compared with the first 5 months of 2021, the percentage of children aged 9-13 years with an in-person visit who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine between June 2021 and August 2022 rose from 30.3% to 42.8% – a 41% increase. The share who received two doses by age 13 years more than doubled, from 19.3% to 42.7%, Dr. O’Leary said.

Frustrated efforts

Although those figures might seem to make an iron-clad case for earlier vaccinations against HPV – which is responsible for nearly 35,000 cases of cancer annually – factors beyond statistics have frustrated efforts to increase acceptance of the shots.

Data published in 2022 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 89.6% of teens aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 89% got one or more doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccine. However, only 76.9% had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. The rate of receiving both doses needed for full protection was much lower (61.7%).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society now endorse the strategy of offering HPV vaccine as early as age 9, which avoids the need for multiple shots at a single visit and results in more kids getting both doses. In a recent study that surveyed primary care professionals who see pediatric patients, 21% were already offering HPV vaccine at age 9, and another 48% were willing to try the approach.

What was the most common objection to the earlier age? Nearly three-quarters of clinicians said they felt that parents weren’t ready to talk about HPV vaccination yet.

Noel Brewer, PhD, one of the authors of the survey study, wondered why clinicians feel the need to bring up sex at all. “Providers should never be talking about sex when they are talking about vaccine, because that’s not the point,” said Dr. Brewer, the distinguished professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He pointed out that providers don’t talk about the route of transmission for any other vaccine.

Dr. Brewer led a randomized controlled trial that trained pediatric clinicians in the “announcement” strategy, in which the clinician announces the vaccines that are due at that visit. If the parent hesitates, the clinician then probes further to identify and address their concerns and provides more information. If the parent is still not convinced, the clinician notes the discussion in the chart and tries again at the next visit.

The strategy was effective: Intervention clinics had a 5.4% higher rate of HPV vaccination coverage than control clinics after six months. Dr. Brewer and his colleagues have trained over 1,700 providers in the technique since 2020.

A cancer – not STI – vaccine

Although DHHA hasn’t participated in Dr. Brewer’s training, Dr. O’Leary and her colleagues take a similar approach of simply stating which vaccines the child should receive that day. And they talk about HPV as a cancer vaccine instead of one to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.

In her experience, this emphasis changes the conversation. Dr. O’Leary described a typical comment from parents as, “Oh, of course I would give my child a vaccine that could prevent cancer.”

Ana Rodriguez, MD, MPH, an obstetrician, became interested in raising rates of vaccination against HPV after watching too many women battle a preventable cancer. She worked for several years in the Rio Grande Valley along the U.S. border with Mexico, an impoverished rural area with poor access to health care and high rates of HPV infection.

“I would treat women very young – not even 30 years of age – already fighting advanced precancerous lesions secondary to HPV,” said Dr. Rodriguez, an associate professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

In 2016, when Texas ranked 47th in the nation for rates of up-to-date HPV vaccination, Dr. Rodriguez helped launch a community-based educational campaign in four rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley using social media, radio, and in-person meetings with school PTA members and members of school boards to educate staff and parents about the need for vaccination against the infection.

In 2019, the team began offering the vaccine to children ages 9-12 years at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and other school events, pivoting to outdoor events using a mobile vaccine van after COVID-19 struck. They recently published a study showing that 73.6% of students who received their first dose of vaccine at age 11 or younger completed the series, compared with only 45.1% of children who got their first dose at age 12 or older.

Dr. Rodriguez encountered parents who felt 9 or 10 years old was too young because their children were not going to be sexually active anytime soon. Her response was to describe HPV as a tool to prevent cancer, telling parents, “If you vaccinate your kids young enough, they will be protected for life.”

Lifetime protection is another point in favor of giving HPV vaccine prior to Tdap and MenACWY. The response to the two-dose series of HPV in preadolescents is robust and long-lasting, with no downside to giving it a few years earlier. In contrast, immunity to MenACWY wanes after a few years, so the immunization must be given before children enter high school, when their risk for meningitis increases.

The annual toll of deaths in the United States from meningococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis typically totals less than 100, whereas cancer deaths attributable to HPV infection number in the thousands each year. And that may be the best reason for attempting new strategies to help HPV vaccination rates catch up to the rest of the preteen vaccines.

Dr. Brewer’s work was supported by the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, and from training grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brewer has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and served as a paid advisor for Merck. Dr. O’Leary reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rodriguez received a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antimicrobial resistance requires a manifold response

BUENOS AIRES – Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a global concern. And while one issue to be addressed is the deficit in research and development for new antibiotics, efforts to tackle this public health threat also should be directed toward promoting more rational prescription practices and strengthening the ability to identify the microorganisms responsible for infections, according to the World Health Organization. This was the conclusion reached at the fourth meeting of the WHO AMR Surveillance and Quality Assessment Collaborating Centres Network, which was held in Buenos Aires.

“We have to provide assistance to countries to ensure that the drugs are being used responsibly. We can come up with new antibiotics, but the issue at hand is not simply one of innovation: If nothing is done to correct inappropriate prescription practices and to overcome the lack of diagnostic laboratories at the country level, we’re going to miss out on those drugs as soon as they become available,” Kitty van Weezenbeek, MD, PhD, MPH, director of the AMR Surveillance, Prevention, and Control (AMR/SPC) Department at the WHO’s headquarters in Geneva, told this news organization.

Dr. van Weezenbeek pointed out that although there are currently no shortages of antimicrobials, the development and launch of new drugs that fight multidrug-resistant infections – infections for which there are few therapeutic options – has proceeded slowly. “It takes 10 to 15 years to develop a new antibiotic,” she said, adding that “the majority of pharmaceutical companies that had been engaged in the development of antimicrobials have filed for bankruptcy.”

In 2019, more people died – 1.2 million – from AMR than from malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV combined. Why are there so few market incentives when there is such a great need for those drugs? “One reason is that the pharmaceutical industry makes more money with long-term treatments, such as those for cancer and respiratory diseases. The other problem is that people everywhere are told not to use antibiotics,” said Dr. van Weezenbeek.

“A course of antibiotics lasts a few days, especially because we’re promoting rational use. Therefore, the trend is for the total amount of antimicrobials being used to be lower. So, it’s not as profitable,” added Carmem Lucia Pessoa-Silva, MD, PhD, head of the Surveillance, Evidence, and Laboratory Strengthening Unit of the WHO’s AMR/SPC Department.

On that note, Dr. van Weezenbeek mentioned that member countries are working with pharmaceutical companies and universities to address this problem. The WHO, for its part, has responded by implementing a global mechanism with a public health approach to create a “healthy” and equitable market for these medicines.

AMR is one of the top 10 global threats to human health. But it also has an impact on animal production, agricultural production, and the environment. Strategies to tackle AMR based on the One Health approach should involve all actors, social sectors, and citizens, according to Eva Jané Llopis, PhD, the representative of the Pan American Health Organization/WHO in Argentina.

At the root of the AMR problem is the widespread use of these drugs as growth promoters in animal production – for which several countries have enacted regulations – as well as “misunderstandings” between patients and physicians when there is not sufficient, timely access to laboratory diagnostics, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

“People think that if they’re given broad-spectrum antibiotics, they’re being prescribed the best antibiotics; and doctors, because there are no laboratory services, prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics because they want to help patients. But that ends up causing more resistance to drugs, and thus, those antibiotics aren’t good for the patients,” said Dr. van Weezenbeek.

The WHO Global AMR and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) was launched in 2015. Its 2022 report, which marked the end of the system’s early implementation period, noted that the reported AMR rates are often lower in countries, territories, and areas with better testing coverage for most pathogen-drug-infection site combinations. However, as Dr. Pessoa-Silva acknowledged, monitoring “has not yet generated representative data,” because in many cases, countries either do not have surveillance systems or have only recently started implementing them.

Even so, the indicators that are available paint an increasingly worrisome picture. “For example, in many countries, resistance rates to first-line antibiotics were around 10%-20% with respect to Escherichia coli urinary tract infections and bloodstream bacteriologically confirmed infections. So, the risk of treatment failure is very high,” explained Dr. Pessoa-Silva.

The latest estimates indicate that every 2 or 3 minutes, somewhere in the world, a child dies from AMR. And the situation is particularly “dramatic” in neonatal intensive care units, where outbreaks of multidrug-resistant infections have a mortality rate of 50%, said Pilar Ramón-Pardo, MD, PhD, lead of the Special Program on AMR at the Pan American Health Organization, the WHO Regional Office for the Americas.

AMR rates also got worse during the pandemic because of the inappropriate prescription of massive amounts of antibiotics to hospitalized patients – something that was not in compliance with guidelines or protocols. Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, is an infectious disease specialist and the head of the Control and Response Strategies Unit in the WHO’s AMR Division. She spoke about the global clinical platform data pertaining to more than 1,500,000 patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19. Since 2020, 85% received antimicrobial treatment, despite the fact that only 5% had a concomitant infection at admission. “It’s easier to give antibiotics than to make a proper diagnosis,” said Dr. Bertagnolio.

This article was translated from Medscape’s Spanish edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

BUENOS AIRES – Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a global concern. And while one issue to be addressed is the deficit in research and development for new antibiotics, efforts to tackle this public health threat also should be directed toward promoting more rational prescription practices and strengthening the ability to identify the microorganisms responsible for infections, according to the World Health Organization. This was the conclusion reached at the fourth meeting of the WHO AMR Surveillance and Quality Assessment Collaborating Centres Network, which was held in Buenos Aires.

“We have to provide assistance to countries to ensure that the drugs are being used responsibly. We can come up with new antibiotics, but the issue at hand is not simply one of innovation: If nothing is done to correct inappropriate prescription practices and to overcome the lack of diagnostic laboratories at the country level, we’re going to miss out on those drugs as soon as they become available,” Kitty van Weezenbeek, MD, PhD, MPH, director of the AMR Surveillance, Prevention, and Control (AMR/SPC) Department at the WHO’s headquarters in Geneva, told this news organization.

Dr. van Weezenbeek pointed out that although there are currently no shortages of antimicrobials, the development and launch of new drugs that fight multidrug-resistant infections – infections for which there are few therapeutic options – has proceeded slowly. “It takes 10 to 15 years to develop a new antibiotic,” she said, adding that “the majority of pharmaceutical companies that had been engaged in the development of antimicrobials have filed for bankruptcy.”

In 2019, more people died – 1.2 million – from AMR than from malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV combined. Why are there so few market incentives when there is such a great need for those drugs? “One reason is that the pharmaceutical industry makes more money with long-term treatments, such as those for cancer and respiratory diseases. The other problem is that people everywhere are told not to use antibiotics,” said Dr. van Weezenbeek.

“A course of antibiotics lasts a few days, especially because we’re promoting rational use. Therefore, the trend is for the total amount of antimicrobials being used to be lower. So, it’s not as profitable,” added Carmem Lucia Pessoa-Silva, MD, PhD, head of the Surveillance, Evidence, and Laboratory Strengthening Unit of the WHO’s AMR/SPC Department.

On that note, Dr. van Weezenbeek mentioned that member countries are working with pharmaceutical companies and universities to address this problem. The WHO, for its part, has responded by implementing a global mechanism with a public health approach to create a “healthy” and equitable market for these medicines.

AMR is one of the top 10 global threats to human health. But it also has an impact on animal production, agricultural production, and the environment. Strategies to tackle AMR based on the One Health approach should involve all actors, social sectors, and citizens, according to Eva Jané Llopis, PhD, the representative of the Pan American Health Organization/WHO in Argentina.

At the root of the AMR problem is the widespread use of these drugs as growth promoters in animal production – for which several countries have enacted regulations – as well as “misunderstandings” between patients and physicians when there is not sufficient, timely access to laboratory diagnostics, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

“People think that if they’re given broad-spectrum antibiotics, they’re being prescribed the best antibiotics; and doctors, because there are no laboratory services, prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics because they want to help patients. But that ends up causing more resistance to drugs, and thus, those antibiotics aren’t good for the patients,” said Dr. van Weezenbeek.

The WHO Global AMR and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) was launched in 2015. Its 2022 report, which marked the end of the system’s early implementation period, noted that the reported AMR rates are often lower in countries, territories, and areas with better testing coverage for most pathogen-drug-infection site combinations. However, as Dr. Pessoa-Silva acknowledged, monitoring “has not yet generated representative data,” because in many cases, countries either do not have surveillance systems or have only recently started implementing them.

Even so, the indicators that are available paint an increasingly worrisome picture. “For example, in many countries, resistance rates to first-line antibiotics were around 10%-20% with respect to Escherichia coli urinary tract infections and bloodstream bacteriologically confirmed infections. So, the risk of treatment failure is very high,” explained Dr. Pessoa-Silva.

The latest estimates indicate that every 2 or 3 minutes, somewhere in the world, a child dies from AMR. And the situation is particularly “dramatic” in neonatal intensive care units, where outbreaks of multidrug-resistant infections have a mortality rate of 50%, said Pilar Ramón-Pardo, MD, PhD, lead of the Special Program on AMR at the Pan American Health Organization, the WHO Regional Office for the Americas.

AMR rates also got worse during the pandemic because of the inappropriate prescription of massive amounts of antibiotics to hospitalized patients – something that was not in compliance with guidelines or protocols. Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, is an infectious disease specialist and the head of the Control and Response Strategies Unit in the WHO’s AMR Division. She spoke about the global clinical platform data pertaining to more than 1,500,000 patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19. Since 2020, 85% received antimicrobial treatment, despite the fact that only 5% had a concomitant infection at admission. “It’s easier to give antibiotics than to make a proper diagnosis,” said Dr. Bertagnolio.

This article was translated from Medscape’s Spanish edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

BUENOS AIRES – Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a global concern. And while one issue to be addressed is the deficit in research and development for new antibiotics, efforts to tackle this public health threat also should be directed toward promoting more rational prescription practices and strengthening the ability to identify the microorganisms responsible for infections, according to the World Health Organization. This was the conclusion reached at the fourth meeting of the WHO AMR Surveillance and Quality Assessment Collaborating Centres Network, which was held in Buenos Aires.

“We have to provide assistance to countries to ensure that the drugs are being used responsibly. We can come up with new antibiotics, but the issue at hand is not simply one of innovation: If nothing is done to correct inappropriate prescription practices and to overcome the lack of diagnostic laboratories at the country level, we’re going to miss out on those drugs as soon as they become available,” Kitty van Weezenbeek, MD, PhD, MPH, director of the AMR Surveillance, Prevention, and Control (AMR/SPC) Department at the WHO’s headquarters in Geneva, told this news organization.

Dr. van Weezenbeek pointed out that although there are currently no shortages of antimicrobials, the development and launch of new drugs that fight multidrug-resistant infections – infections for which there are few therapeutic options – has proceeded slowly. “It takes 10 to 15 years to develop a new antibiotic,” she said, adding that “the majority of pharmaceutical companies that had been engaged in the development of antimicrobials have filed for bankruptcy.”

In 2019, more people died – 1.2 million – from AMR than from malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV combined. Why are there so few market incentives when there is such a great need for those drugs? “One reason is that the pharmaceutical industry makes more money with long-term treatments, such as those for cancer and respiratory diseases. The other problem is that people everywhere are told not to use antibiotics,” said Dr. van Weezenbeek.

“A course of antibiotics lasts a few days, especially because we’re promoting rational use. Therefore, the trend is for the total amount of antimicrobials being used to be lower. So, it’s not as profitable,” added Carmem Lucia Pessoa-Silva, MD, PhD, head of the Surveillance, Evidence, and Laboratory Strengthening Unit of the WHO’s AMR/SPC Department.

On that note, Dr. van Weezenbeek mentioned that member countries are working with pharmaceutical companies and universities to address this problem. The WHO, for its part, has responded by implementing a global mechanism with a public health approach to create a “healthy” and equitable market for these medicines.

AMR is one of the top 10 global threats to human health. But it also has an impact on animal production, agricultural production, and the environment. Strategies to tackle AMR based on the One Health approach should involve all actors, social sectors, and citizens, according to Eva Jané Llopis, PhD, the representative of the Pan American Health Organization/WHO in Argentina.

At the root of the AMR problem is the widespread use of these drugs as growth promoters in animal production – for which several countries have enacted regulations – as well as “misunderstandings” between patients and physicians when there is not sufficient, timely access to laboratory diagnostics, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

“People think that if they’re given broad-spectrum antibiotics, they’re being prescribed the best antibiotics; and doctors, because there are no laboratory services, prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics because they want to help patients. But that ends up causing more resistance to drugs, and thus, those antibiotics aren’t good for the patients,” said Dr. van Weezenbeek.

The WHO Global AMR and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) was launched in 2015. Its 2022 report, which marked the end of the system’s early implementation period, noted that the reported AMR rates are often lower in countries, territories, and areas with better testing coverage for most pathogen-drug-infection site combinations. However, as Dr. Pessoa-Silva acknowledged, monitoring “has not yet generated representative data,” because in many cases, countries either do not have surveillance systems or have only recently started implementing them.

Even so, the indicators that are available paint an increasingly worrisome picture. “For example, in many countries, resistance rates to first-line antibiotics were around 10%-20% with respect to Escherichia coli urinary tract infections and bloodstream bacteriologically confirmed infections. So, the risk of treatment failure is very high,” explained Dr. Pessoa-Silva.

The latest estimates indicate that every 2 or 3 minutes, somewhere in the world, a child dies from AMR. And the situation is particularly “dramatic” in neonatal intensive care units, where outbreaks of multidrug-resistant infections have a mortality rate of 50%, said Pilar Ramón-Pardo, MD, PhD, lead of the Special Program on AMR at the Pan American Health Organization, the WHO Regional Office for the Americas.

AMR rates also got worse during the pandemic because of the inappropriate prescription of massive amounts of antibiotics to hospitalized patients – something that was not in compliance with guidelines or protocols. Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, is an infectious disease specialist and the head of the Control and Response Strategies Unit in the WHO’s AMR Division. She spoke about the global clinical platform data pertaining to more than 1,500,000 patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19. Since 2020, 85% received antimicrobial treatment, despite the fact that only 5% had a concomitant infection at admission. “It’s easier to give antibiotics than to make a proper diagnosis,” said Dr. Bertagnolio.

This article was translated from Medscape’s Spanish edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

New Medicare rule streamlines prior authorization in Medicare Advantage plans

A new federal rule seeks to reduce Medicare Advantage insurance plans’ prior authorization burdens on physicians while also ensuring that enrollees have the same access to necessary care that they would receive under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The prior authorization changes, announced this week, are part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 2024 update of policy changes for Medicare Advantage and Part D pharmacy plans

Medicare Advantage plans’ business practices have raised significant concerns in recent years. More than 28 million Americans were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2022, which is nearly half of all Medicare enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare pays a fixed amount per enrollee per year to these privately run managed care plans, in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have been criticized for aggressive marketing, for overbilling the federal government for care, and for using prior authorization to inappropriately deny needed care to patients.

About 13% of prior authorization requests that are denied by Medicare Advantage plans actually met Medicare coverage rules and should have been approved, the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported in 2022.

The newly finalized rule now requires Medicare Advantage plans to do the following.

- Ensure that a prior authorization approval, once granted, remains valid for as long as medically necessary to avoid disruptions in care.

- Conduct an annual review of utilization management policies.

- Ensure that coverage denials based on medical necessity be reviewed by health care professionals with relevant expertise before a denial can be issued.

Physician groups welcomed the changes. In a statement, the American Medical Association said that an initial reading of the rule suggested CMS had “taken important steps toward right-sizing the prior authorization process.”

The Medical Group Management Association praised CMS in a statement for having limited “dangerous disruptions and delays to necessary patient care” resulting from the cumbersome processes of prior approval. With the new rules, CMS will provide greater consistency across Advantage plans as well as traditional Medicare, said Anders Gilberg, MGMA’s senior vice president of government affairs, in a statement.

Peer consideration

The final rule did disappoint physician groups in one key way. CMS rebuffed requests to have CMS require Advantage plans to use reviewers of the same specialty as treating physicians in handling disputes about prior authorization. CMS said it expects plans to exercise judgment in finding reviewers with “sufficient expertise to make an informed and supportable decision.”

“In some instances, we expect that plans will use a physician or other health care professional of the same specialty or subspecialty as the treating physician,” CMS said. “In other instances, we expect that plans will utilize a reviewer with specialized training, certification, or clinical experience in the applicable field of medicine.”

Medicare Advantage marketing ‘sowing confusion’

With this final rule, CMS also sought to protect consumers from “potentially misleading marketing practices” used in promoting Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription drug plans.

The agency said it had received complaints about people who have received official-looking promotional materials for Medicare that directed them not to government sources of information but to Medicare Advantage and Part D plans or their agents and brokers.

Ads now must mention a specific plan name, and they cannot use the Medicare name, CMS logo, Medicare card, or other government information in a misleading way, CMS said.

“CMS can see no value or purpose in a non-governmental entity’s use of the Medicare logo or HHS logo except for the express purpose of sowing confusion and misrepresenting itself as the government,” the agency said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new federal rule seeks to reduce Medicare Advantage insurance plans’ prior authorization burdens on physicians while also ensuring that enrollees have the same access to necessary care that they would receive under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The prior authorization changes, announced this week, are part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 2024 update of policy changes for Medicare Advantage and Part D pharmacy plans

Medicare Advantage plans’ business practices have raised significant concerns in recent years. More than 28 million Americans were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2022, which is nearly half of all Medicare enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare pays a fixed amount per enrollee per year to these privately run managed care plans, in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have been criticized for aggressive marketing, for overbilling the federal government for care, and for using prior authorization to inappropriately deny needed care to patients.

About 13% of prior authorization requests that are denied by Medicare Advantage plans actually met Medicare coverage rules and should have been approved, the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported in 2022.

The newly finalized rule now requires Medicare Advantage plans to do the following.

- Ensure that a prior authorization approval, once granted, remains valid for as long as medically necessary to avoid disruptions in care.

- Conduct an annual review of utilization management policies.

- Ensure that coverage denials based on medical necessity be reviewed by health care professionals with relevant expertise before a denial can be issued.

Physician groups welcomed the changes. In a statement, the American Medical Association said that an initial reading of the rule suggested CMS had “taken important steps toward right-sizing the prior authorization process.”

The Medical Group Management Association praised CMS in a statement for having limited “dangerous disruptions and delays to necessary patient care” resulting from the cumbersome processes of prior approval. With the new rules, CMS will provide greater consistency across Advantage plans as well as traditional Medicare, said Anders Gilberg, MGMA’s senior vice president of government affairs, in a statement.

Peer consideration

The final rule did disappoint physician groups in one key way. CMS rebuffed requests to have CMS require Advantage plans to use reviewers of the same specialty as treating physicians in handling disputes about prior authorization. CMS said it expects plans to exercise judgment in finding reviewers with “sufficient expertise to make an informed and supportable decision.”

“In some instances, we expect that plans will use a physician or other health care professional of the same specialty or subspecialty as the treating physician,” CMS said. “In other instances, we expect that plans will utilize a reviewer with specialized training, certification, or clinical experience in the applicable field of medicine.”

Medicare Advantage marketing ‘sowing confusion’

With this final rule, CMS also sought to protect consumers from “potentially misleading marketing practices” used in promoting Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription drug plans.

The agency said it had received complaints about people who have received official-looking promotional materials for Medicare that directed them not to government sources of information but to Medicare Advantage and Part D plans or their agents and brokers.

Ads now must mention a specific plan name, and they cannot use the Medicare name, CMS logo, Medicare card, or other government information in a misleading way, CMS said.

“CMS can see no value or purpose in a non-governmental entity’s use of the Medicare logo or HHS logo except for the express purpose of sowing confusion and misrepresenting itself as the government,” the agency said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new federal rule seeks to reduce Medicare Advantage insurance plans’ prior authorization burdens on physicians while also ensuring that enrollees have the same access to necessary care that they would receive under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The prior authorization changes, announced this week, are part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 2024 update of policy changes for Medicare Advantage and Part D pharmacy plans

Medicare Advantage plans’ business practices have raised significant concerns in recent years. More than 28 million Americans were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2022, which is nearly half of all Medicare enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare pays a fixed amount per enrollee per year to these privately run managed care plans, in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have been criticized for aggressive marketing, for overbilling the federal government for care, and for using prior authorization to inappropriately deny needed care to patients.

About 13% of prior authorization requests that are denied by Medicare Advantage plans actually met Medicare coverage rules and should have been approved, the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported in 2022.

The newly finalized rule now requires Medicare Advantage plans to do the following.

- Ensure that a prior authorization approval, once granted, remains valid for as long as medically necessary to avoid disruptions in care.

- Conduct an annual review of utilization management policies.

- Ensure that coverage denials based on medical necessity be reviewed by health care professionals with relevant expertise before a denial can be issued.

Physician groups welcomed the changes. In a statement, the American Medical Association said that an initial reading of the rule suggested CMS had “taken important steps toward right-sizing the prior authorization process.”

The Medical Group Management Association praised CMS in a statement for having limited “dangerous disruptions and delays to necessary patient care” resulting from the cumbersome processes of prior approval. With the new rules, CMS will provide greater consistency across Advantage plans as well as traditional Medicare, said Anders Gilberg, MGMA’s senior vice president of government affairs, in a statement.

Peer consideration

The final rule did disappoint physician groups in one key way. CMS rebuffed requests to have CMS require Advantage plans to use reviewers of the same specialty as treating physicians in handling disputes about prior authorization. CMS said it expects plans to exercise judgment in finding reviewers with “sufficient expertise to make an informed and supportable decision.”

“In some instances, we expect that plans will use a physician or other health care professional of the same specialty or subspecialty as the treating physician,” CMS said. “In other instances, we expect that plans will utilize a reviewer with specialized training, certification, or clinical experience in the applicable field of medicine.”

Medicare Advantage marketing ‘sowing confusion’

With this final rule, CMS also sought to protect consumers from “potentially misleading marketing practices” used in promoting Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription drug plans.

The agency said it had received complaints about people who have received official-looking promotional materials for Medicare that directed them not to government sources of information but to Medicare Advantage and Part D plans or their agents and brokers.

Ads now must mention a specific plan name, and they cannot use the Medicare name, CMS logo, Medicare card, or other government information in a misleading way, CMS said.

“CMS can see no value or purpose in a non-governmental entity’s use of the Medicare logo or HHS logo except for the express purpose of sowing confusion and misrepresenting itself as the government,” the agency said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study highlights potential skin cancer risk of UV nail polish dryers

Results of a study recently published in Nature Communications suggests that According to two experts, these findings raise concerns regarding the safety of frequent use of these nail dryers.

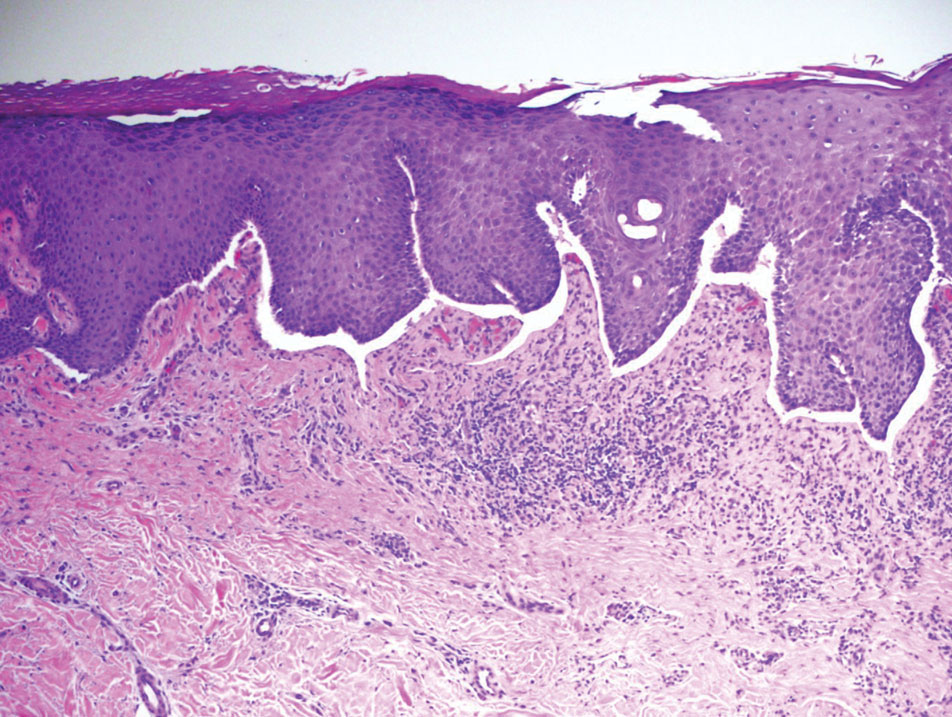

In the study, human and mouse cells were exposed to radiation from UV nail dryers. Exposing human and mice skin cells to UVA light for 20 minutes resulted in the death of 20%-30% of cells; three consecutive 20-minute sessions resulted in the death of 65%-70% of cells. Additionally, surviving cells suffered oxidative damage to their DNA and mitochondria, with mutational patterns similar to those seen in skin cancer, study investigator Maria Zhivagui, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates reported.

“This study showed that irradiation of human and mouse cell lines using UV nail polish dryers resulted in DNA damage and genome mutations,” Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, director of the nail division at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said in an interview. The study “ties together exposure to UV light from nail polish dryers and genetic mutations that are associated with skin cancers,” added Dr. Lipner, who was not involved with the study.

UV nail lamps are commonly used to dry and harden gel nail polish formulas. Often referred to as “mini tanning beds,” these devices emit UVA radiation, classified as a Group 1 Carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

“Both UVA and UVB are main drivers of both melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas (basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma),” said Anthony Rossi, MD, a dermatologic surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who was also not a study investigator. UV irradiance “produces DNA mutations that are specific to forming types of skin cancer,” he said in an interview.

UVA wavelengths commonly used in nail dryers can penetrate all layers of the epidermis, the top layer of the skin, potentially affecting stem cells in the skin, according to the study.

Dr. Lipner noted that “there have been several case reports of patients with histories of gel manicures using UV nail polish dryers who later developed squamous cell carcinomas on the dorsal hands, fingers, and nails, and articles describing high UV emissions from nail polish dryers, but the direct connection between UV dryers and skin cancer development was tenuous.” The first of its kind, the new study investigated the impact of UV nail drying devices at a cellular level.

The results of this study, in combination with previous case reports suggesting the development of skin cancers following UVA dryer use, raise concern regarding the safety of these commonly used devices. The study, the authors wrote, “does not provide direct evidence for an increased cancer risk in human beings,” but their findings and “prior evidence strongly suggest that radiation emitted by UV nail polish dryers may cause cancers of the hand and that UV nail polish dryers, similar to tanning beds, may increase the risk of early onset skin cancer.”

Dr. Rossi said that, “while this study shows that the UV exposure does affect human cells and causes mutations, the study was not done in vivo in human beings, so further studies are needed to know at what dose and frequency gel manicures would be needed to cause detrimental effects.” However, for people who regularly receive gel manicures involving UV nail dryers, both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Rossi recommend applying a broad-spectrum sunscreen to protect the dorsal hands, fingertips, and skin surrounding the nails, or wearing UV-protective gloves.

The study was supported by an Alfred B. Sloan Research Fellowship to one of the authors and grants from the National Institutes of Health to two authors. One author reported being a compensated consultant and having an equity interest in io9. Dr. Lipner and Dr. Rossi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a study recently published in Nature Communications suggests that According to two experts, these findings raise concerns regarding the safety of frequent use of these nail dryers.

In the study, human and mouse cells were exposed to radiation from UV nail dryers. Exposing human and mice skin cells to UVA light for 20 minutes resulted in the death of 20%-30% of cells; three consecutive 20-minute sessions resulted in the death of 65%-70% of cells. Additionally, surviving cells suffered oxidative damage to their DNA and mitochondria, with mutational patterns similar to those seen in skin cancer, study investigator Maria Zhivagui, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates reported.

“This study showed that irradiation of human and mouse cell lines using UV nail polish dryers resulted in DNA damage and genome mutations,” Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, director of the nail division at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said in an interview. The study “ties together exposure to UV light from nail polish dryers and genetic mutations that are associated with skin cancers,” added Dr. Lipner, who was not involved with the study.

UV nail lamps are commonly used to dry and harden gel nail polish formulas. Often referred to as “mini tanning beds,” these devices emit UVA radiation, classified as a Group 1 Carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

“Both UVA and UVB are main drivers of both melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas (basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma),” said Anthony Rossi, MD, a dermatologic surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who was also not a study investigator. UV irradiance “produces DNA mutations that are specific to forming types of skin cancer,” he said in an interview.

UVA wavelengths commonly used in nail dryers can penetrate all layers of the epidermis, the top layer of the skin, potentially affecting stem cells in the skin, according to the study.

Dr. Lipner noted that “there have been several case reports of patients with histories of gel manicures using UV nail polish dryers who later developed squamous cell carcinomas on the dorsal hands, fingers, and nails, and articles describing high UV emissions from nail polish dryers, but the direct connection between UV dryers and skin cancer development was tenuous.” The first of its kind, the new study investigated the impact of UV nail drying devices at a cellular level.

The results of this study, in combination with previous case reports suggesting the development of skin cancers following UVA dryer use, raise concern regarding the safety of these commonly used devices. The study, the authors wrote, “does not provide direct evidence for an increased cancer risk in human beings,” but their findings and “prior evidence strongly suggest that radiation emitted by UV nail polish dryers may cause cancers of the hand and that UV nail polish dryers, similar to tanning beds, may increase the risk of early onset skin cancer.”

Dr. Rossi said that, “while this study shows that the UV exposure does affect human cells and causes mutations, the study was not done in vivo in human beings, so further studies are needed to know at what dose and frequency gel manicures would be needed to cause detrimental effects.” However, for people who regularly receive gel manicures involving UV nail dryers, both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Rossi recommend applying a broad-spectrum sunscreen to protect the dorsal hands, fingertips, and skin surrounding the nails, or wearing UV-protective gloves.

The study was supported by an Alfred B. Sloan Research Fellowship to one of the authors and grants from the National Institutes of Health to two authors. One author reported being a compensated consultant and having an equity interest in io9. Dr. Lipner and Dr. Rossi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a study recently published in Nature Communications suggests that According to two experts, these findings raise concerns regarding the safety of frequent use of these nail dryers.

In the study, human and mouse cells were exposed to radiation from UV nail dryers. Exposing human and mice skin cells to UVA light for 20 minutes resulted in the death of 20%-30% of cells; three consecutive 20-minute sessions resulted in the death of 65%-70% of cells. Additionally, surviving cells suffered oxidative damage to their DNA and mitochondria, with mutational patterns similar to those seen in skin cancer, study investigator Maria Zhivagui, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates reported.

“This study showed that irradiation of human and mouse cell lines using UV nail polish dryers resulted in DNA damage and genome mutations,” Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, director of the nail division at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said in an interview. The study “ties together exposure to UV light from nail polish dryers and genetic mutations that are associated with skin cancers,” added Dr. Lipner, who was not involved with the study.

UV nail lamps are commonly used to dry and harden gel nail polish formulas. Often referred to as “mini tanning beds,” these devices emit UVA radiation, classified as a Group 1 Carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

“Both UVA and UVB are main drivers of both melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas (basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma),” said Anthony Rossi, MD, a dermatologic surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who was also not a study investigator. UV irradiance “produces DNA mutations that are specific to forming types of skin cancer,” he said in an interview.

UVA wavelengths commonly used in nail dryers can penetrate all layers of the epidermis, the top layer of the skin, potentially affecting stem cells in the skin, according to the study.

Dr. Lipner noted that “there have been several case reports of patients with histories of gel manicures using UV nail polish dryers who later developed squamous cell carcinomas on the dorsal hands, fingers, and nails, and articles describing high UV emissions from nail polish dryers, but the direct connection between UV dryers and skin cancer development was tenuous.” The first of its kind, the new study investigated the impact of UV nail drying devices at a cellular level.

The results of this study, in combination with previous case reports suggesting the development of skin cancers following UVA dryer use, raise concern regarding the safety of these commonly used devices. The study, the authors wrote, “does not provide direct evidence for an increased cancer risk in human beings,” but their findings and “prior evidence strongly suggest that radiation emitted by UV nail polish dryers may cause cancers of the hand and that UV nail polish dryers, similar to tanning beds, may increase the risk of early onset skin cancer.”

Dr. Rossi said that, “while this study shows that the UV exposure does affect human cells and causes mutations, the study was not done in vivo in human beings, so further studies are needed to know at what dose and frequency gel manicures would be needed to cause detrimental effects.” However, for people who regularly receive gel manicures involving UV nail dryers, both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Rossi recommend applying a broad-spectrum sunscreen to protect the dorsal hands, fingertips, and skin surrounding the nails, or wearing UV-protective gloves.

The study was supported by an Alfred B. Sloan Research Fellowship to one of the authors and grants from the National Institutes of Health to two authors. One author reported being a compensated consultant and having an equity interest in io9. Dr. Lipner and Dr. Rossi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

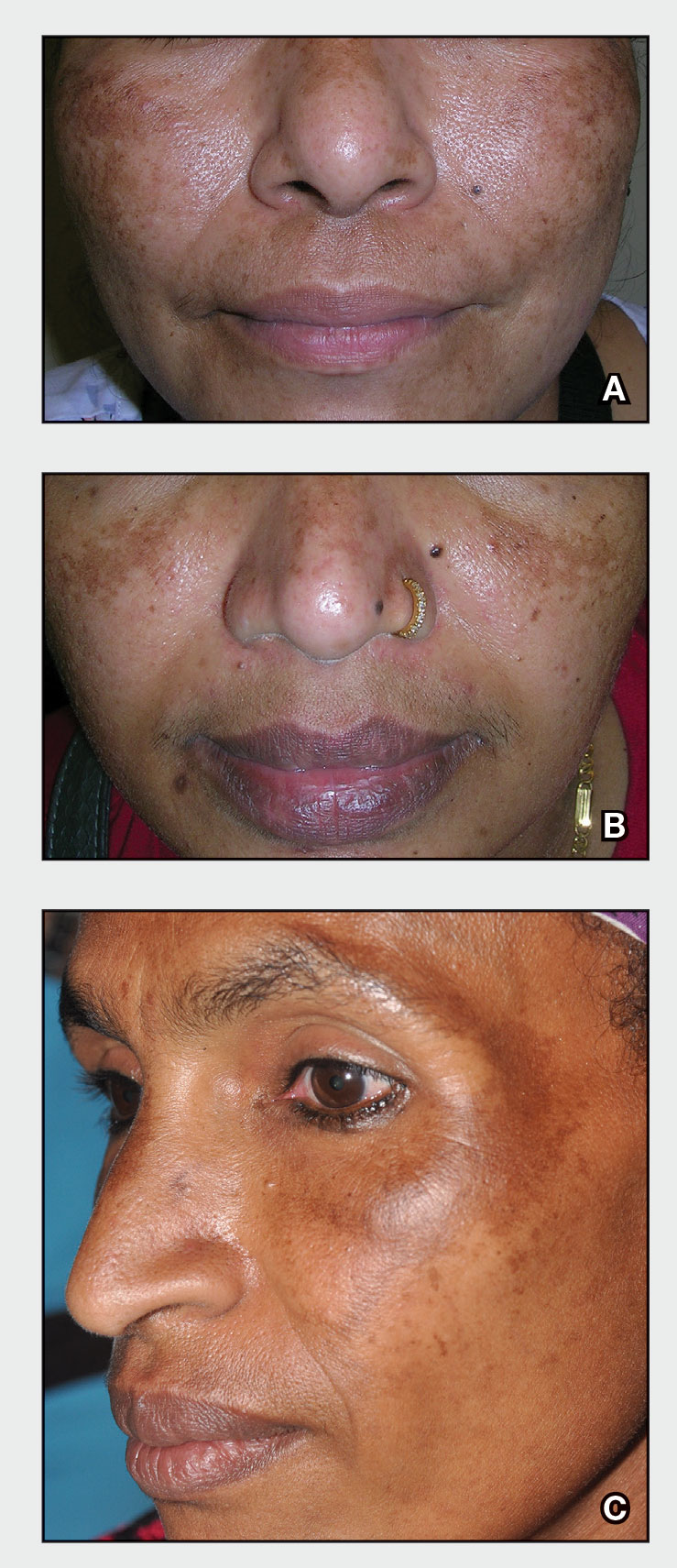

What are the clinical implications of recent skin dysbiosis discoveries?

NEW ORLEANS – .

“There’s still a lot for us to learn,” Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Multiple factors contribute to the variability in the skin microbiota, including age, sex, environment, immune system, host genotype, lifestyle, and pathobiology. The question becomes, when do these factors or impacts on the microbiota become clinically significant?”

According to Dr. Friedman, there are 10 times more bacteria cells than human cells in the human body, “but it’s not a fight to the finish; it’s not us versus them,” he said. “Together, we are a super organism.” There are also more than 500 species of bacteria on human skin excluding viruses and fungi, and each person carries up to 5 pounds of bacteria, which is akin to finding a new organ in the body.

“What’s so unique is that we each have our own bacterial fingerprint,” he said. “Whoever is sitting next to you? Their microbiota makeup is different than yours.”

Beyond genetics and environment, activities that can contribute to alterations in skin flora or skin dysbiosis include topical application of steroids, antibiotics, retinoids, harsh soaps, chemical and physical exfoliants, and resurfacing techniques. “With anything we apply or do to the skin, we are literally changing the home of many microorganisms, for good or bad,” he said.

In the realm of atopic dermatitis (AD), Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as an offender in the pathophysiology of the disease. “It’s not about one single species of Staphylococcus, though,” said Dr. Friedman, who also is director of translational research at George Washington University. “We’re finding out that, depending on the severity of disease, Staph. epidermis may be part of the problem as opposed to it just being about Staph. aureus. Furthermore, and more importantly, these changes in the microbiota, specifically a decrease in microbial diversity, has been shown to precede a disease flare, highlighting the central role of maintaining microbial diversity and by definition, supporting the living barrier in our management of AD.”

With this in mind, researchers in one study used high-throughput sequencing to evaluate the microbial communities associated with affected and unaffected skin of 49 patients with AD before and after emollient treatment. Following 84 days of emollient application, clinical symptoms of AD improved in 72% of the study population and Stenotrophomonas species were significantly more abundant among responders.

Prebiotics, probiotics

“Our treatments certainly can positively impact the microbiota, as we have seen even recently with some of our new targeted therapies, but we can also directly provide support,” he continued. Prebiotics, which he defined as supplements or foods that contain a nondigestible ingredient that selectively stimulates the growth and/or activity of indigenous bacteria, can be found in many over-the-counter moisturizers.

For example, colloidal oatmeal has been found to support the growth of S. epidermidis and enhance the production of lactic acid. “We really don’t know much about what these induced changes mean from a clinical perspective; that has yet to be elucidated,” Dr. Friedman said.

In light of the recent attention to the early application of moisturizers in infants at high risk of developing AD in an effort to prevent or limit AD, “maybe part of this has to do with applying something that’s nurturing an evolving microbiota,” Dr. Friedman noted. “It’s something to think about.”

Yet another area of study involves the use of probiotics, which Dr. Friedman defined as supplements or foods that contain viable microorganisms that alter the microflora of the host. In a first-of-its-kind trial, researchers evaluated the safety and efficacy of self-administered topical Roseomonas mucosa in 10 adults and 5 children with AD. No adverse events or treatment complications were observed, and the topical R. mucosa was associated with significant decreases in measures of disease severity, topical steroid requirement, and S. aureus burden

In a more recent randomized trial of 11 patients with AD, Richard L. Gallo, MD, PhD, chair of dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and colleagues found that application of a personalized topical cream formulated from coagulase-negative Staphylococcus with antimicrobial activity against S. aureus reduced colonization of S. aureus and improved disease severity.

And in another randomized, controlled trial, Italian researchers enrolled 80 adults with mild to severe AD to receive a placebo or a supplement that was a mixture of lactobacilli for 56 days. They found that adults in the treatment arm showed an improvement in skin smoothness, skin moisturization, self-perception, and a decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index as well as in levels of inflammatory markers associated with AD.

Dr. Friedman also discussed postbiotics, nonviable bacterial products or metabolic byproducts from probiotic microorganisms that have biologic activity in the host. In one trial, French researchers enrolled 75 people with AD who ranged in age from 6 to 70 years to receive a cream containing a 5% lysate of the nonpathogenic bacteria Vitreoscilla filiformis, or a vehicle cream for 30 days. They found that compared with the vehicle, V. filiformis lysate significantly decreased SCORAD levels and pruritus; active cream was shown to significantly decrease loss of sleep from day 0 to day 29.

Dr. Friedman characterized these novel approaches to AD as “an exciting area, one we need to pay attention to. But what I really want to know is, aside from these purposefully made and marketed products that have pre- and postprobiotics, is there a difference with some of the products we use already? My assumption is that there is, but we need to see that data.”

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant and/or advisory board member for Medscape/SanovaWorks, Oakstone Institute, L’Oréal, La Roche Posay, Galderma, Aveeno, Ortho Dermatologic, Microcures, Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly, Hoth Therapeutics, Zylo Therapeutics, BMS, Vial, Janssen, Novocure, Dermavant, Regeneron/Sanofi, and Incyte. He has also received grants from Pfizer, the Dermatology Foundation, Lilly, Janssen, Incyte, and Galderma.

NEW ORLEANS – .

“There’s still a lot for us to learn,” Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Multiple factors contribute to the variability in the skin microbiota, including age, sex, environment, immune system, host genotype, lifestyle, and pathobiology. The question becomes, when do these factors or impacts on the microbiota become clinically significant?”

According to Dr. Friedman, there are 10 times more bacteria cells than human cells in the human body, “but it’s not a fight to the finish; it’s not us versus them,” he said. “Together, we are a super organism.” There are also more than 500 species of bacteria on human skin excluding viruses and fungi, and each person carries up to 5 pounds of bacteria, which is akin to finding a new organ in the body.

“What’s so unique is that we each have our own bacterial fingerprint,” he said. “Whoever is sitting next to you? Their microbiota makeup is different than yours.”

Beyond genetics and environment, activities that can contribute to alterations in skin flora or skin dysbiosis include topical application of steroids, antibiotics, retinoids, harsh soaps, chemical and physical exfoliants, and resurfacing techniques. “With anything we apply or do to the skin, we are literally changing the home of many microorganisms, for good or bad,” he said.

In the realm of atopic dermatitis (AD), Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as an offender in the pathophysiology of the disease. “It’s not about one single species of Staphylococcus, though,” said Dr. Friedman, who also is director of translational research at George Washington University. “We’re finding out that, depending on the severity of disease, Staph. epidermis may be part of the problem as opposed to it just being about Staph. aureus. Furthermore, and more importantly, these changes in the microbiota, specifically a decrease in microbial diversity, has been shown to precede a disease flare, highlighting the central role of maintaining microbial diversity and by definition, supporting the living barrier in our management of AD.”

With this in mind, researchers in one study used high-throughput sequencing to evaluate the microbial communities associated with affected and unaffected skin of 49 patients with AD before and after emollient treatment. Following 84 days of emollient application, clinical symptoms of AD improved in 72% of the study population and Stenotrophomonas species were significantly more abundant among responders.

Prebiotics, probiotics

“Our treatments certainly can positively impact the microbiota, as we have seen even recently with some of our new targeted therapies, but we can also directly provide support,” he continued. Prebiotics, which he defined as supplements or foods that contain a nondigestible ingredient that selectively stimulates the growth and/or activity of indigenous bacteria, can be found in many over-the-counter moisturizers.

For example, colloidal oatmeal has been found to support the growth of S. epidermidis and enhance the production of lactic acid. “We really don’t know much about what these induced changes mean from a clinical perspective; that has yet to be elucidated,” Dr. Friedman said.

In light of the recent attention to the early application of moisturizers in infants at high risk of developing AD in an effort to prevent or limit AD, “maybe part of this has to do with applying something that’s nurturing an evolving microbiota,” Dr. Friedman noted. “It’s something to think about.”

Yet another area of study involves the use of probiotics, which Dr. Friedman defined as supplements or foods that contain viable microorganisms that alter the microflora of the host. In a first-of-its-kind trial, researchers evaluated the safety and efficacy of self-administered topical Roseomonas mucosa in 10 adults and 5 children with AD. No adverse events or treatment complications were observed, and the topical R. mucosa was associated with significant decreases in measures of disease severity, topical steroid requirement, and S. aureus burden

In a more recent randomized trial of 11 patients with AD, Richard L. Gallo, MD, PhD, chair of dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and colleagues found that application of a personalized topical cream formulated from coagulase-negative Staphylococcus with antimicrobial activity against S. aureus reduced colonization of S. aureus and improved disease severity.

And in another randomized, controlled trial, Italian researchers enrolled 80 adults with mild to severe AD to receive a placebo or a supplement that was a mixture of lactobacilli for 56 days. They found that adults in the treatment arm showed an improvement in skin smoothness, skin moisturization, self-perception, and a decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index as well as in levels of inflammatory markers associated with AD.

Dr. Friedman also discussed postbiotics, nonviable bacterial products or metabolic byproducts from probiotic microorganisms that have biologic activity in the host. In one trial, French researchers enrolled 75 people with AD who ranged in age from 6 to 70 years to receive a cream containing a 5% lysate of the nonpathogenic bacteria Vitreoscilla filiformis, or a vehicle cream for 30 days. They found that compared with the vehicle, V. filiformis lysate significantly decreased SCORAD levels and pruritus; active cream was shown to significantly decrease loss of sleep from day 0 to day 29.

Dr. Friedman characterized these novel approaches to AD as “an exciting area, one we need to pay attention to. But what I really want to know is, aside from these purposefully made and marketed products that have pre- and postprobiotics, is there a difference with some of the products we use already? My assumption is that there is, but we need to see that data.”

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant and/or advisory board member for Medscape/SanovaWorks, Oakstone Institute, L’Oréal, La Roche Posay, Galderma, Aveeno, Ortho Dermatologic, Microcures, Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly, Hoth Therapeutics, Zylo Therapeutics, BMS, Vial, Janssen, Novocure, Dermavant, Regeneron/Sanofi, and Incyte. He has also received grants from Pfizer, the Dermatology Foundation, Lilly, Janssen, Incyte, and Galderma.

NEW ORLEANS – .

“There’s still a lot for us to learn,” Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Multiple factors contribute to the variability in the skin microbiota, including age, sex, environment, immune system, host genotype, lifestyle, and pathobiology. The question becomes, when do these factors or impacts on the microbiota become clinically significant?”

According to Dr. Friedman, there are 10 times more bacteria cells than human cells in the human body, “but it’s not a fight to the finish; it’s not us versus them,” he said. “Together, we are a super organism.” There are also more than 500 species of bacteria on human skin excluding viruses and fungi, and each person carries up to 5 pounds of bacteria, which is akin to finding a new organ in the body.

“What’s so unique is that we each have our own bacterial fingerprint,” he said. “Whoever is sitting next to you? Their microbiota makeup is different than yours.”