User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Rituximab for Acquired Hemophilia A in the Setting of Bullous Pemphigoid

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease characterized by the formation of antihemidesmosomal antibodies, resulting in tense bullae concentrated on the extremities and trunk that often are preceded by a pruritic urticarial phase.1 A rare complication of BP is the subsequent development of acquired hemophilia A. We report a case of BP with associated factor VIII–neutralizing antibodies in a patient who improved with prednisone and rituximab therapy.

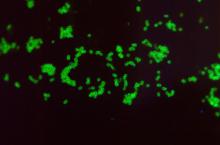

A 78-year-old woman presented with red-orange pruritic plaques on the right heel that spread to involve the arms and legs, abdomen, and trunk with new-onset bullae over the course of 2 weeks (Figure 1). Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of BP was confirmed via biopsy and direct immunofluorescence.

Despite treatment with prednisone 40 mg/d and clobetasol ointment 0.05%, she continued to develop extensive cutaneous bullae and new hemorrhagic bullae on the buccal mucosae (Figure 2), necessitating hospital admission. She clinically improved after prednisone was increased to 60 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily was added; however, she returned 8 days after discharge from the hospital with altered mental status, new-onset hematomas of the abdomen and right leg, and a hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). Activated prothrombin time was prolonged without correction on mixing studies, raising concern for coagulation factor inhibition. Factor VIII activity was diminished to 9% and then 1% three days later. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was acutely stabilized with blood transfusions, intravenous immunoglobulin, tranexamic acid, and aminocaproic acid. Rituximab was initiated at 1000 mg and then administered again 2 weeks later. At 7-week follow-up, coagulation studies normalized, and there was no evidence of blistering dermatosis on examination.

Bullous pemphigoid generally is seen in patients older than 60 years, and the incidence increases with age. The disease course follows formation of IgG antibodies against BP180 or BP230, leading to localized activation of the complement cascade at the basement membrane zone.1 Medications, vaccinations, UV radiation, and burns have been implicated in disease induction.2

Identification of antihemidesmosomal antibodies on lesional biopsy via direct immunofluorescence is the gold standard for diagnosis, though indirect antibodies measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay may provide information regarding disease severity.1 Patients with milder disease may be treated with topical corticosteroids, doxycycline, and nicotinamide; however, severe disease requires treatment with systemic glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing agents.3 Rituximab initially was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris, and mounting evidence for the use of rituximab in BP is promising. Although data are limited to retrospective studies, rituximab has shown notable remission rates and steroid-sparing effects in those with moderate to severe BP.4

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is caused by the production of IgG autoantibodies, which block physiologic interactions between factor VIII and factor IX, phospholipids, and von Willebrand factor.5 Acquired hemophilia A often is diagnosed by prolonged activated prothrombin time and decreased factor VIII activity after a previously unaffected patient develops severe bleeding. Treatment involves re-establishing hemostasis and the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents to diminish autoantibody production.4

Bullous pemphigoid–associated AHA likely is due to antigenic similarity between BP180 and factor VIII, leading to concomitant neutralization of factor VIII with the production of BP-associated autoantibodies.5 Bullous pemphigoid–associated AHA has been reported with manifestations of bleeding concurrent with or after the development of dermatologic disease. Rituximab use has been reported with clinical efficacy in several cases, including our patient.6 Continued hematologic monitoring is recommended, as recurrences are common within the first 2 years.5

- Bağcı IS, Horváth ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Schiavo AL, Ruocco E, Brancaccio G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013;31:391-399.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet. 2013;381:320-332.

- Cho Y, Chu C, Wang L. First-line combination therapy with rituximab and corticosteroids provides a high complete remission rate in moderate-to-severe bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:302-304.

- Zdziarska J, Musial J. Acquired hemophilia A: an underdiagnosed severe bleeding disorder. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:200-206.

- Binet Q, Lambert C, Sacré L, et al. Successful management of acquired hemophilia associated with bullous pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature [published online March 28, 2017]. Case Rep Hematol. 2017;2017:2057019.

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease characterized by the formation of antihemidesmosomal antibodies, resulting in tense bullae concentrated on the extremities and trunk that often are preceded by a pruritic urticarial phase.1 A rare complication of BP is the subsequent development of acquired hemophilia A. We report a case of BP with associated factor VIII–neutralizing antibodies in a patient who improved with prednisone and rituximab therapy.

A 78-year-old woman presented with red-orange pruritic plaques on the right heel that spread to involve the arms and legs, abdomen, and trunk with new-onset bullae over the course of 2 weeks (Figure 1). Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of BP was confirmed via biopsy and direct immunofluorescence.

Despite treatment with prednisone 40 mg/d and clobetasol ointment 0.05%, she continued to develop extensive cutaneous bullae and new hemorrhagic bullae on the buccal mucosae (Figure 2), necessitating hospital admission. She clinically improved after prednisone was increased to 60 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily was added; however, she returned 8 days after discharge from the hospital with altered mental status, new-onset hematomas of the abdomen and right leg, and a hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). Activated prothrombin time was prolonged without correction on mixing studies, raising concern for coagulation factor inhibition. Factor VIII activity was diminished to 9% and then 1% three days later. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was acutely stabilized with blood transfusions, intravenous immunoglobulin, tranexamic acid, and aminocaproic acid. Rituximab was initiated at 1000 mg and then administered again 2 weeks later. At 7-week follow-up, coagulation studies normalized, and there was no evidence of blistering dermatosis on examination.

Bullous pemphigoid generally is seen in patients older than 60 years, and the incidence increases with age. The disease course follows formation of IgG antibodies against BP180 or BP230, leading to localized activation of the complement cascade at the basement membrane zone.1 Medications, vaccinations, UV radiation, and burns have been implicated in disease induction.2

Identification of antihemidesmosomal antibodies on lesional biopsy via direct immunofluorescence is the gold standard for diagnosis, though indirect antibodies measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay may provide information regarding disease severity.1 Patients with milder disease may be treated with topical corticosteroids, doxycycline, and nicotinamide; however, severe disease requires treatment with systemic glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing agents.3 Rituximab initially was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris, and mounting evidence for the use of rituximab in BP is promising. Although data are limited to retrospective studies, rituximab has shown notable remission rates and steroid-sparing effects in those with moderate to severe BP.4

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is caused by the production of IgG autoantibodies, which block physiologic interactions between factor VIII and factor IX, phospholipids, and von Willebrand factor.5 Acquired hemophilia A often is diagnosed by prolonged activated prothrombin time and decreased factor VIII activity after a previously unaffected patient develops severe bleeding. Treatment involves re-establishing hemostasis and the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents to diminish autoantibody production.4

Bullous pemphigoid–associated AHA likely is due to antigenic similarity between BP180 and factor VIII, leading to concomitant neutralization of factor VIII with the production of BP-associated autoantibodies.5 Bullous pemphigoid–associated AHA has been reported with manifestations of bleeding concurrent with or after the development of dermatologic disease. Rituximab use has been reported with clinical efficacy in several cases, including our patient.6 Continued hematologic monitoring is recommended, as recurrences are common within the first 2 years.5

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease characterized by the formation of antihemidesmosomal antibodies, resulting in tense bullae concentrated on the extremities and trunk that often are preceded by a pruritic urticarial phase.1 A rare complication of BP is the subsequent development of acquired hemophilia A. We report a case of BP with associated factor VIII–neutralizing antibodies in a patient who improved with prednisone and rituximab therapy.

A 78-year-old woman presented with red-orange pruritic plaques on the right heel that spread to involve the arms and legs, abdomen, and trunk with new-onset bullae over the course of 2 weeks (Figure 1). Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of BP was confirmed via biopsy and direct immunofluorescence.

Despite treatment with prednisone 40 mg/d and clobetasol ointment 0.05%, she continued to develop extensive cutaneous bullae and new hemorrhagic bullae on the buccal mucosae (Figure 2), necessitating hospital admission. She clinically improved after prednisone was increased to 60 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily was added; however, she returned 8 days after discharge from the hospital with altered mental status, new-onset hematomas of the abdomen and right leg, and a hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). Activated prothrombin time was prolonged without correction on mixing studies, raising concern for coagulation factor inhibition. Factor VIII activity was diminished to 9% and then 1% three days later. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was acutely stabilized with blood transfusions, intravenous immunoglobulin, tranexamic acid, and aminocaproic acid. Rituximab was initiated at 1000 mg and then administered again 2 weeks later. At 7-week follow-up, coagulation studies normalized, and there was no evidence of blistering dermatosis on examination.

Bullous pemphigoid generally is seen in patients older than 60 years, and the incidence increases with age. The disease course follows formation of IgG antibodies against BP180 or BP230, leading to localized activation of the complement cascade at the basement membrane zone.1 Medications, vaccinations, UV radiation, and burns have been implicated in disease induction.2

Identification of antihemidesmosomal antibodies on lesional biopsy via direct immunofluorescence is the gold standard for diagnosis, though indirect antibodies measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay may provide information regarding disease severity.1 Patients with milder disease may be treated with topical corticosteroids, doxycycline, and nicotinamide; however, severe disease requires treatment with systemic glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing agents.3 Rituximab initially was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris, and mounting evidence for the use of rituximab in BP is promising. Although data are limited to retrospective studies, rituximab has shown notable remission rates and steroid-sparing effects in those with moderate to severe BP.4

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is caused by the production of IgG autoantibodies, which block physiologic interactions between factor VIII and factor IX, phospholipids, and von Willebrand factor.5 Acquired hemophilia A often is diagnosed by prolonged activated prothrombin time and decreased factor VIII activity after a previously unaffected patient develops severe bleeding. Treatment involves re-establishing hemostasis and the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents to diminish autoantibody production.4

Bullous pemphigoid–associated AHA likely is due to antigenic similarity between BP180 and factor VIII, leading to concomitant neutralization of factor VIII with the production of BP-associated autoantibodies.5 Bullous pemphigoid–associated AHA has been reported with manifestations of bleeding concurrent with or after the development of dermatologic disease. Rituximab use has been reported with clinical efficacy in several cases, including our patient.6 Continued hematologic monitoring is recommended, as recurrences are common within the first 2 years.5

- Bağcı IS, Horváth ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Schiavo AL, Ruocco E, Brancaccio G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013;31:391-399.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet. 2013;381:320-332.

- Cho Y, Chu C, Wang L. First-line combination therapy with rituximab and corticosteroids provides a high complete remission rate in moderate-to-severe bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:302-304.

- Zdziarska J, Musial J. Acquired hemophilia A: an underdiagnosed severe bleeding disorder. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:200-206.

- Binet Q, Lambert C, Sacré L, et al. Successful management of acquired hemophilia associated with bullous pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature [published online March 28, 2017]. Case Rep Hematol. 2017;2017:2057019.

- Bağcı IS, Horváth ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Schiavo AL, Ruocco E, Brancaccio G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013;31:391-399.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet. 2013;381:320-332.

- Cho Y, Chu C, Wang L. First-line combination therapy with rituximab and corticosteroids provides a high complete remission rate in moderate-to-severe bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:302-304.

- Zdziarska J, Musial J. Acquired hemophilia A: an underdiagnosed severe bleeding disorder. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:200-206.

- Binet Q, Lambert C, Sacré L, et al. Successful management of acquired hemophilia associated with bullous pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature [published online March 28, 2017]. Case Rep Hematol. 2017;2017:2057019.

Practice Points

- Physicians must be aware of the potential for acquired hemophilia A in patients with bullous pemphigoid (BP).

- Rituximab is an effective therapy for BP and should be considered for patients in this cohort.

Peristomal Pyoderma Gangrenosum at an Ileostomy Site

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

Practice Points

- A pyoderma gangrenosum subtype occurs in close proximity to an abdominal stoma.

- Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically responds best to tumor necrosis factor α blockers and corticosteroid therapy (intralesional and systemic).

Coming to a pill near you: The exercise molecule

Exercise in a pill? Sign us up

You just got home from a long shift and you know you should go to the gym, but the bed is calling and you just answered. We know sometimes we have to make sacrifices in the name of fitness, but there just aren’t enough hours in the day. Unless our prayers have been answered. There could be a pill that has the benefits of working out without having to work out.

In a study published in Nature, investigators reported that they have identified a molecule made during exercise and used it on mice, which took in less food after being given the pill, which may open doors to understanding how exercise affects hunger.

In the first part of the study, the researchers found the molecule, known as Lac-Phe – which is synthesized from lactate and phenylalanine – in the blood plasma of mice after they had run on a treadmill.

The investigators then gave a Lac-Phe supplement to mice on high-fat diets and found that their food intake was about 50% of what other mice were eating. The supplement also improved their glucose tolerance.

Because the research also found Lac-Phe in humans who exercised, they hope that this pill will be in our future. “Our next steps include finding more details about how Lac-Phe mediates its effects in the body, including the brain,” Yong Xu, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in a written statement. “Our goal is to learn to modulate this exercise pathway for therapeutic interventions.”

As always, we are rooting for you, science!

Gonorrhea and grandparents: A match made in prehistoric heaven

*Editorial note: LOTME takes no responsibility for any unfortunate imagery the reader may have experienced from the above headline.

Old people are the greatest. Back pains, cognitive decline, aches in all the diodes down your left side, there’s nothing quite like your golden years. Notably, however, humans are one of the few animals who experience true old age, as most creatures are adapted to maximize reproductive potential. As such, living past menopause is rare in the animal kingdom.

This is where the “grandmother hypothesis” comes in: Back in Ye Olde Stone Age, women who lived into old age could provide child care for younger women, because human babies require a lot more time and attention than other animal offspring. But how did humans end up living so long? Enter a group of Californian researchers, who believe they have an answer. It was gonorrhea.

When compared with the chimpanzee genome (as well as with Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest ancestors), humans have a unique mutated version of the CD33 gene that lacks a sugar-binding site; the standard version uses the sugar-binding site to protect against autoimmune response in the body, but that same site actually suppresses the brain’s ability to clear away damaged brain cells and amyloid, which eventually leads to diseases like dementia. The mutated version allows microglia (brain immune cells) to attack and clear out this unwanted material. People with higher levels of this mutated CD33 variant actually have higher protection against Alzheimer’s.

Interestingly, gonorrhea bacteria are coated in the same sugar that standard CD33 receptors bind to, thus allowing them to bypass the body’s immune system. According to the researchers, the mutated CD33 version likely emerged as a protection against gonorrhea, depriving the bacteria of their “molecular mimicry” abilities. In one of life’s happy accidents, it turned out this mutation also protects against age-related diseases, thus allowing humans with the mutation to live longer. Obviously, this was a good thing, and we ran with it until the modern day. Now we have senior citizens climbing Everest, and all our politicians keep on politicking into their 70s and 80s ... well, everything has its drawbacks.

Parents raise a glass to children’s food addiction

There can be something pretty addicting about processed foods. Have you ever eaten just one french fry? Or taken just one cookie? If so, your willpower is incredible. For many of us, it can be a struggle to stop.

A recent study from the University of Michigan, which considered the existence of an eating phenotype, suggests our parents’ habits could be to blame.

By administering a series of questionnaires that inquired about food addiction, alcohol use disorders, cannabis use disorder, nicotine/e-cigarette dependence, and their family tree, investigators found that participants with a “paternal history of problematic alcohol use” had higher risk of food addiction but not obesity.

Apparently about one in five people display a clinically significant addiction to highly processed foods. It was noted that foods like ice cream, pizza, and french fries have high amounts of refined carbs and fats, which could trigger an addictive response.

Lindzey Hoover, a graduate student at the university who was the study’s lead author, noted that living in an environment where these foods are cheap and accessible can be really challenging for those with a family history of addiction. The investigators suggested that public health approaches, like restriction of other substances and marketing to kids, should be put in place for highly processed foods.

Maybe french fries should come with a warning label.

A prescription for America’s traffic problems

Nostalgia is a funny thing. Do you ever feel nostalgic about things that really weren’t very pleasant in the first place? Take, for instance, the morning commute. Here in the Washington area, more than 2 years into the COVID era, the traffic is still not what it used to be … and we kind of miss it.

Nah, not really. That was just a way to get everyone thinking about driving, because AAA has something of an explanation for the situation out there on the highways and byways of America. It’s drugs. No, not those kinds of drugs. This time it’s prescription drugs that are the problem. Well, part of the problem, anyway.

AAA did a survey last summer and found that nearly 50% of drivers “used one or more potentially impairing medications in the past 30 days. … The proportion of those choosing to drive is higher among those taking multiple medications.” How much higher? More than 63% of those with two or more prescriptions were driving within 2 hours of taking at least one of those meds, as were 71% of those taking three or more.

The 2,657 respondents also were asked about the types of potentially impairing drugs they were taking: 61% of those using antidepressants had been on the road within 2 hours of use at least once in the past 30 days, as had 73% of those taking an amphetamine, AAA said.

So there you have it. That guy in the BMW who’s been tailgating you for the last 3 miles? He may be a jerk, but there’s a good chance he’s a jerk with a prescription … or two … or three.

Exercise in a pill? Sign us up

You just got home from a long shift and you know you should go to the gym, but the bed is calling and you just answered. We know sometimes we have to make sacrifices in the name of fitness, but there just aren’t enough hours in the day. Unless our prayers have been answered. There could be a pill that has the benefits of working out without having to work out.

In a study published in Nature, investigators reported that they have identified a molecule made during exercise and used it on mice, which took in less food after being given the pill, which may open doors to understanding how exercise affects hunger.

In the first part of the study, the researchers found the molecule, known as Lac-Phe – which is synthesized from lactate and phenylalanine – in the blood plasma of mice after they had run on a treadmill.

The investigators then gave a Lac-Phe supplement to mice on high-fat diets and found that their food intake was about 50% of what other mice were eating. The supplement also improved their glucose tolerance.

Because the research also found Lac-Phe in humans who exercised, they hope that this pill will be in our future. “Our next steps include finding more details about how Lac-Phe mediates its effects in the body, including the brain,” Yong Xu, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in a written statement. “Our goal is to learn to modulate this exercise pathway for therapeutic interventions.”

As always, we are rooting for you, science!

Gonorrhea and grandparents: A match made in prehistoric heaven

*Editorial note: LOTME takes no responsibility for any unfortunate imagery the reader may have experienced from the above headline.

Old people are the greatest. Back pains, cognitive decline, aches in all the diodes down your left side, there’s nothing quite like your golden years. Notably, however, humans are one of the few animals who experience true old age, as most creatures are adapted to maximize reproductive potential. As such, living past menopause is rare in the animal kingdom.

This is where the “grandmother hypothesis” comes in: Back in Ye Olde Stone Age, women who lived into old age could provide child care for younger women, because human babies require a lot more time and attention than other animal offspring. But how did humans end up living so long? Enter a group of Californian researchers, who believe they have an answer. It was gonorrhea.

When compared with the chimpanzee genome (as well as with Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest ancestors), humans have a unique mutated version of the CD33 gene that lacks a sugar-binding site; the standard version uses the sugar-binding site to protect against autoimmune response in the body, but that same site actually suppresses the brain’s ability to clear away damaged brain cells and amyloid, which eventually leads to diseases like dementia. The mutated version allows microglia (brain immune cells) to attack and clear out this unwanted material. People with higher levels of this mutated CD33 variant actually have higher protection against Alzheimer’s.

Interestingly, gonorrhea bacteria are coated in the same sugar that standard CD33 receptors bind to, thus allowing them to bypass the body’s immune system. According to the researchers, the mutated CD33 version likely emerged as a protection against gonorrhea, depriving the bacteria of their “molecular mimicry” abilities. In one of life’s happy accidents, it turned out this mutation also protects against age-related diseases, thus allowing humans with the mutation to live longer. Obviously, this was a good thing, and we ran with it until the modern day. Now we have senior citizens climbing Everest, and all our politicians keep on politicking into their 70s and 80s ... well, everything has its drawbacks.

Parents raise a glass to children’s food addiction

There can be something pretty addicting about processed foods. Have you ever eaten just one french fry? Or taken just one cookie? If so, your willpower is incredible. For many of us, it can be a struggle to stop.

A recent study from the University of Michigan, which considered the existence of an eating phenotype, suggests our parents’ habits could be to blame.

By administering a series of questionnaires that inquired about food addiction, alcohol use disorders, cannabis use disorder, nicotine/e-cigarette dependence, and their family tree, investigators found that participants with a “paternal history of problematic alcohol use” had higher risk of food addiction but not obesity.

Apparently about one in five people display a clinically significant addiction to highly processed foods. It was noted that foods like ice cream, pizza, and french fries have high amounts of refined carbs and fats, which could trigger an addictive response.

Lindzey Hoover, a graduate student at the university who was the study’s lead author, noted that living in an environment where these foods are cheap and accessible can be really challenging for those with a family history of addiction. The investigators suggested that public health approaches, like restriction of other substances and marketing to kids, should be put in place for highly processed foods.

Maybe french fries should come with a warning label.

A prescription for America’s traffic problems

Nostalgia is a funny thing. Do you ever feel nostalgic about things that really weren’t very pleasant in the first place? Take, for instance, the morning commute. Here in the Washington area, more than 2 years into the COVID era, the traffic is still not what it used to be … and we kind of miss it.

Nah, not really. That was just a way to get everyone thinking about driving, because AAA has something of an explanation for the situation out there on the highways and byways of America. It’s drugs. No, not those kinds of drugs. This time it’s prescription drugs that are the problem. Well, part of the problem, anyway.

AAA did a survey last summer and found that nearly 50% of drivers “used one or more potentially impairing medications in the past 30 days. … The proportion of those choosing to drive is higher among those taking multiple medications.” How much higher? More than 63% of those with two or more prescriptions were driving within 2 hours of taking at least one of those meds, as were 71% of those taking three or more.

The 2,657 respondents also were asked about the types of potentially impairing drugs they were taking: 61% of those using antidepressants had been on the road within 2 hours of use at least once in the past 30 days, as had 73% of those taking an amphetamine, AAA said.

So there you have it. That guy in the BMW who’s been tailgating you for the last 3 miles? He may be a jerk, but there’s a good chance he’s a jerk with a prescription … or two … or three.

Exercise in a pill? Sign us up

You just got home from a long shift and you know you should go to the gym, but the bed is calling and you just answered. We know sometimes we have to make sacrifices in the name of fitness, but there just aren’t enough hours in the day. Unless our prayers have been answered. There could be a pill that has the benefits of working out without having to work out.

In a study published in Nature, investigators reported that they have identified a molecule made during exercise and used it on mice, which took in less food after being given the pill, which may open doors to understanding how exercise affects hunger.

In the first part of the study, the researchers found the molecule, known as Lac-Phe – which is synthesized from lactate and phenylalanine – in the blood plasma of mice after they had run on a treadmill.

The investigators then gave a Lac-Phe supplement to mice on high-fat diets and found that their food intake was about 50% of what other mice were eating. The supplement also improved their glucose tolerance.

Because the research also found Lac-Phe in humans who exercised, they hope that this pill will be in our future. “Our next steps include finding more details about how Lac-Phe mediates its effects in the body, including the brain,” Yong Xu, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in a written statement. “Our goal is to learn to modulate this exercise pathway for therapeutic interventions.”

As always, we are rooting for you, science!

Gonorrhea and grandparents: A match made in prehistoric heaven

*Editorial note: LOTME takes no responsibility for any unfortunate imagery the reader may have experienced from the above headline.

Old people are the greatest. Back pains, cognitive decline, aches in all the diodes down your left side, there’s nothing quite like your golden years. Notably, however, humans are one of the few animals who experience true old age, as most creatures are adapted to maximize reproductive potential. As such, living past menopause is rare in the animal kingdom.

This is where the “grandmother hypothesis” comes in: Back in Ye Olde Stone Age, women who lived into old age could provide child care for younger women, because human babies require a lot more time and attention than other animal offspring. But how did humans end up living so long? Enter a group of Californian researchers, who believe they have an answer. It was gonorrhea.

When compared with the chimpanzee genome (as well as with Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest ancestors), humans have a unique mutated version of the CD33 gene that lacks a sugar-binding site; the standard version uses the sugar-binding site to protect against autoimmune response in the body, but that same site actually suppresses the brain’s ability to clear away damaged brain cells and amyloid, which eventually leads to diseases like dementia. The mutated version allows microglia (brain immune cells) to attack and clear out this unwanted material. People with higher levels of this mutated CD33 variant actually have higher protection against Alzheimer’s.

Interestingly, gonorrhea bacteria are coated in the same sugar that standard CD33 receptors bind to, thus allowing them to bypass the body’s immune system. According to the researchers, the mutated CD33 version likely emerged as a protection against gonorrhea, depriving the bacteria of their “molecular mimicry” abilities. In one of life’s happy accidents, it turned out this mutation also protects against age-related diseases, thus allowing humans with the mutation to live longer. Obviously, this was a good thing, and we ran with it until the modern day. Now we have senior citizens climbing Everest, and all our politicians keep on politicking into their 70s and 80s ... well, everything has its drawbacks.

Parents raise a glass to children’s food addiction

There can be something pretty addicting about processed foods. Have you ever eaten just one french fry? Or taken just one cookie? If so, your willpower is incredible. For many of us, it can be a struggle to stop.

A recent study from the University of Michigan, which considered the existence of an eating phenotype, suggests our parents’ habits could be to blame.

By administering a series of questionnaires that inquired about food addiction, alcohol use disorders, cannabis use disorder, nicotine/e-cigarette dependence, and their family tree, investigators found that participants with a “paternal history of problematic alcohol use” had higher risk of food addiction but not obesity.

Apparently about one in five people display a clinically significant addiction to highly processed foods. It was noted that foods like ice cream, pizza, and french fries have high amounts of refined carbs and fats, which could trigger an addictive response.

Lindzey Hoover, a graduate student at the university who was the study’s lead author, noted that living in an environment where these foods are cheap and accessible can be really challenging for those with a family history of addiction. The investigators suggested that public health approaches, like restriction of other substances and marketing to kids, should be put in place for highly processed foods.

Maybe french fries should come with a warning label.

A prescription for America’s traffic problems

Nostalgia is a funny thing. Do you ever feel nostalgic about things that really weren’t very pleasant in the first place? Take, for instance, the morning commute. Here in the Washington area, more than 2 years into the COVID era, the traffic is still not what it used to be … and we kind of miss it.

Nah, not really. That was just a way to get everyone thinking about driving, because AAA has something of an explanation for the situation out there on the highways and byways of America. It’s drugs. No, not those kinds of drugs. This time it’s prescription drugs that are the problem. Well, part of the problem, anyway.

AAA did a survey last summer and found that nearly 50% of drivers “used one or more potentially impairing medications in the past 30 days. … The proportion of those choosing to drive is higher among those taking multiple medications.” How much higher? More than 63% of those with two or more prescriptions were driving within 2 hours of taking at least one of those meds, as were 71% of those taking three or more.

The 2,657 respondents also were asked about the types of potentially impairing drugs they were taking: 61% of those using antidepressants had been on the road within 2 hours of use at least once in the past 30 days, as had 73% of those taking an amphetamine, AAA said.

So there you have it. That guy in the BMW who’s been tailgating you for the last 3 miles? He may be a jerk, but there’s a good chance he’s a jerk with a prescription … or two … or three.

How does radiofrequency microneedling work?

Technology in the field of aesthetic dermatology continues to advance over time. Microneedling, largely used to improve textural changes of the skin associated with photoaging and acne scarring, has evolved over time from the use of dermarollers and microneedling skin pens to energy-based devices that deliver radiofrequency (RF) energy though microneedles that are used today.

.

Unlike prior radiofrequency energy-based devices that deliver radiofrequency energy on the skin surface to allow bulk thermal energy (or heat) to stimulate collagen remodeling and tissue tightening, RF microneedling devices deliver the same RF or thermal energy via needles. RF, measured in Hertz (Hz) is part of the electromagnetic spectrum, with most devices delivering thermal energy at around 1-2 MHz, which is less than most typical RF only devices (at around 4-6 MHz), but with potentially more precise depth and delivery. For comparison, the RF of household electrical currents are around 60 Hz; traditional electrosurgical units, 50Hz -300 kHz; AM radio, 500 KHz; and microwaves, 2500 MHz.

When delivered to the skin, RF energy produces a change in the electrical charge of the skin, resulting in movement of electrons. The impedance (or resistance) of the tissue to the electron movement is what generates heat. Different factors, including tissue thickness, pressure applied to the tissue, hydration, bipolar versus monopolar delivery, and the number of needles are several factors than can affect the impedance.