User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Atopic dermatitis: Upadacitinib-induced acne does not pose a significant safety risk

Key clinical point: Acne caused by upadacitinib in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is typically mild or moderate in severity and may not be considered a significant safety risk.

Major finding: Acne of mostly mild or moderate severity was reported by a higher proportion of patients receiving 15 mg upadacitinib (9.8%) and 30 mg upadacitinib (15.2%) vs placebo (2.2%), with no intervention required in 40.5% and 46.6% of patients receiving 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib, respectively. The improvement in quality-of-life scores was proportional to the decrease in AD severity and was similar in patients with or without acne.

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc integrated analysis of 3 phase 3 trials including 2583 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib (15 or 30 mg) or placebo as monotherapy or with concomitant topical corticosteroids.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie, Inc. Five authors declared being employees or stockholders of AbbVie. The other authors reported ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Mendes-Bastos P et al. Characterization of acne associated with upadacitinib treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A post hoc integrated analysis of 3 phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.012

Key clinical point: Acne caused by upadacitinib in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is typically mild or moderate in severity and may not be considered a significant safety risk.

Major finding: Acne of mostly mild or moderate severity was reported by a higher proportion of patients receiving 15 mg upadacitinib (9.8%) and 30 mg upadacitinib (15.2%) vs placebo (2.2%), with no intervention required in 40.5% and 46.6% of patients receiving 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib, respectively. The improvement in quality-of-life scores was proportional to the decrease in AD severity and was similar in patients with or without acne.

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc integrated analysis of 3 phase 3 trials including 2583 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib (15 or 30 mg) or placebo as monotherapy or with concomitant topical corticosteroids.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie, Inc. Five authors declared being employees or stockholders of AbbVie. The other authors reported ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Mendes-Bastos P et al. Characterization of acne associated with upadacitinib treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A post hoc integrated analysis of 3 phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.012

Key clinical point: Acne caused by upadacitinib in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is typically mild or moderate in severity and may not be considered a significant safety risk.

Major finding: Acne of mostly mild or moderate severity was reported by a higher proportion of patients receiving 15 mg upadacitinib (9.8%) and 30 mg upadacitinib (15.2%) vs placebo (2.2%), with no intervention required in 40.5% and 46.6% of patients receiving 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib, respectively. The improvement in quality-of-life scores was proportional to the decrease in AD severity and was similar in patients with or without acne.

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc integrated analysis of 3 phase 3 trials including 2583 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib (15 or 30 mg) or placebo as monotherapy or with concomitant topical corticosteroids.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie, Inc. Five authors declared being employees or stockholders of AbbVie. The other authors reported ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Mendes-Bastos P et al. Characterization of acne associated with upadacitinib treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A post hoc integrated analysis of 3 phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.012

Atopic dermatitis: Improvement in disease severity and skin barrier function with dupilumab

Key clinical point: Dupilumab was more effective than topical corticosteroids (TCS) and cyclosporine in reducing the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and transepidermal water loss (TEWL), both in eczematous lesions and nonlesioned skin.

Major finding: At week 16, a higher proportion of patients receiving dupilumab vs cyclosporine or TCS achieved 50% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-50; 81.8% vs 28.6% or 40.0% respectively; P = .004). TEWL reduced with both dupilumab (P < .001) and TCS (P = .047) in eczematous lesions and with dupilumab in nonlesioned skin (P = .006) with dupilumab treatment being associated with achievement of EASI-50 (odds ratio 10.67; P = .026) and 50% improvement in TEWL (P = .004).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective, observational study including 46 patients with AD who received TCS (n = 10), cyclosporine (n = 14), or dupilumab (n = 22).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Montero-Vilchez T et al. Dupilumab improves skin barrier function in adults with atopic dermatitis: A prospective observational study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12):3341 (Jun 10). Doi: 10.3390/jcm11123341

Key clinical point: Dupilumab was more effective than topical corticosteroids (TCS) and cyclosporine in reducing the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and transepidermal water loss (TEWL), both in eczematous lesions and nonlesioned skin.

Major finding: At week 16, a higher proportion of patients receiving dupilumab vs cyclosporine or TCS achieved 50% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-50; 81.8% vs 28.6% or 40.0% respectively; P = .004). TEWL reduced with both dupilumab (P < .001) and TCS (P = .047) in eczematous lesions and with dupilumab in nonlesioned skin (P = .006) with dupilumab treatment being associated with achievement of EASI-50 (odds ratio 10.67; P = .026) and 50% improvement in TEWL (P = .004).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective, observational study including 46 patients with AD who received TCS (n = 10), cyclosporine (n = 14), or dupilumab (n = 22).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Montero-Vilchez T et al. Dupilumab improves skin barrier function in adults with atopic dermatitis: A prospective observational study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12):3341 (Jun 10). Doi: 10.3390/jcm11123341

Key clinical point: Dupilumab was more effective than topical corticosteroids (TCS) and cyclosporine in reducing the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and transepidermal water loss (TEWL), both in eczematous lesions and nonlesioned skin.

Major finding: At week 16, a higher proportion of patients receiving dupilumab vs cyclosporine or TCS achieved 50% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-50; 81.8% vs 28.6% or 40.0% respectively; P = .004). TEWL reduced with both dupilumab (P < .001) and TCS (P = .047) in eczematous lesions and with dupilumab in nonlesioned skin (P = .006) with dupilumab treatment being associated with achievement of EASI-50 (odds ratio 10.67; P = .026) and 50% improvement in TEWL (P = .004).

Study details: Findings are from a prospective, observational study including 46 patients with AD who received TCS (n = 10), cyclosporine (n = 14), or dupilumab (n = 22).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Montero-Vilchez T et al. Dupilumab improves skin barrier function in adults with atopic dermatitis: A prospective observational study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12):3341 (Jun 10). Doi: 10.3390/jcm11123341

Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Abrocitinib improves clinical scores in IGA nonresponders

Key clinical point: Patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) who did not achieve Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) 0/1 response with abrocitinib at week 12, still achieved clinically meaningful improvements in AD severity, itch, and quality of life.

Major finding: At week 12, a higher proportion of IGA nonresponders receiving 200 and 100 mg abrocitinib vs placebo achieved ≥ 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (41.0% and 27.0% vs 9.4%, respectively), ≥4-point improvement in itch (42.8% and 35.2% vs 18.2%, respectively), and ≥4-point improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (67.6% and 75.0% vs 49.5%, respectively) scores.

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc analysis of 1 phase 2b and 2 phase 3 (JADE Mono-1 and JADE Mono-2) trials including 548 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive abrocitinib (200 or 100 mg) or placebo and did not achieve IGA 0/1 response.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer Inc. Five authors declared being current or former employees and shareholders of Pfizer. The other authors reported ties with various sources, including Pfizer.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. Abrocitinib monotherapy in Investigator’s Global Assessment nonresponders: Improvement in signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis and quality of life. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 (Jul 6). Doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2059053

Key clinical point: Patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) who did not achieve Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) 0/1 response with abrocitinib at week 12, still achieved clinically meaningful improvements in AD severity, itch, and quality of life.

Major finding: At week 12, a higher proportion of IGA nonresponders receiving 200 and 100 mg abrocitinib vs placebo achieved ≥ 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (41.0% and 27.0% vs 9.4%, respectively), ≥4-point improvement in itch (42.8% and 35.2% vs 18.2%, respectively), and ≥4-point improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (67.6% and 75.0% vs 49.5%, respectively) scores.

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc analysis of 1 phase 2b and 2 phase 3 (JADE Mono-1 and JADE Mono-2) trials including 548 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive abrocitinib (200 or 100 mg) or placebo and did not achieve IGA 0/1 response.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer Inc. Five authors declared being current or former employees and shareholders of Pfizer. The other authors reported ties with various sources, including Pfizer.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. Abrocitinib monotherapy in Investigator’s Global Assessment nonresponders: Improvement in signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis and quality of life. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 (Jul 6). Doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2059053

Key clinical point: Patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) who did not achieve Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) 0/1 response with abrocitinib at week 12, still achieved clinically meaningful improvements in AD severity, itch, and quality of life.

Major finding: At week 12, a higher proportion of IGA nonresponders receiving 200 and 100 mg abrocitinib vs placebo achieved ≥ 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (41.0% and 27.0% vs 9.4%, respectively), ≥4-point improvement in itch (42.8% and 35.2% vs 18.2%, respectively), and ≥4-point improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (67.6% and 75.0% vs 49.5%, respectively) scores.

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc analysis of 1 phase 2b and 2 phase 3 (JADE Mono-1 and JADE Mono-2) trials including 548 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive abrocitinib (200 or 100 mg) or placebo and did not achieve IGA 0/1 response.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer Inc. Five authors declared being current or former employees and shareholders of Pfizer. The other authors reported ties with various sources, including Pfizer.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. Abrocitinib monotherapy in Investigator’s Global Assessment nonresponders: Improvement in signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis and quality of life. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 (Jul 6). Doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2059053

Adolescents and children with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis benefit from dupilumab

Key clinical point: Dupilumab led to clinically meaningful improvements in the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and was well tolerated in adolescents and children with moderate-to-severe AD.

Major finding: The mean improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was 59.6% at week 12-24 and 77.0% at week 36-48 (both P < .001), with all patients achieving ≥75% improvement in EASI score after a year or more of receiving dupilumab. Adverse events like conjunctivitis (5.6%) and joint pain (2.2%) were reported by 13.5% of patients.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational study including 89 children and adolescents aged < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD who initiated dupilumab treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Some authors declared serving as consultants or receiving research funds from several sources.

Source: Pagan AD et al. Dupilumab improves clinical scores in children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A real-world, single-center study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.014

Key clinical point: Dupilumab led to clinically meaningful improvements in the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and was well tolerated in adolescents and children with moderate-to-severe AD.

Major finding: The mean improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was 59.6% at week 12-24 and 77.0% at week 36-48 (both P < .001), with all patients achieving ≥75% improvement in EASI score after a year or more of receiving dupilumab. Adverse events like conjunctivitis (5.6%) and joint pain (2.2%) were reported by 13.5% of patients.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational study including 89 children and adolescents aged < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD who initiated dupilumab treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Some authors declared serving as consultants or receiving research funds from several sources.

Source: Pagan AD et al. Dupilumab improves clinical scores in children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A real-world, single-center study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.014

Key clinical point: Dupilumab led to clinically meaningful improvements in the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and was well tolerated in adolescents and children with moderate-to-severe AD.

Major finding: The mean improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was 59.6% at week 12-24 and 77.0% at week 36-48 (both P < .001), with all patients achieving ≥75% improvement in EASI score after a year or more of receiving dupilumab. Adverse events like conjunctivitis (5.6%) and joint pain (2.2%) were reported by 13.5% of patients.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective observational study including 89 children and adolescents aged < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD who initiated dupilumab treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Some authors declared serving as consultants or receiving research funds from several sources.

Source: Pagan AD et al. Dupilumab improves clinical scores in children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A real-world, single-center study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.014

Multi-dimensional and heterogeneous nature of disease burden in atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Disease burden of atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with multiple factors, with the strongest association being with disease severity, time spent managing AD symptoms, and comorbid depression.

Major finding: Disease burden was strongly associated with AD severity (moderate: odds ratio [OR] 4.13; 95% CI 2.94-5.79 or severe: OR 13.63; 95% CI 8.65-21.5 vs mild AD), time spent managing AD symptoms (11-20 hours/week: OR 2.67; 95% CI 1.77-4.03 or ≥21 hours/week: OR 5.34; 95% CI 3.22-8.85 vs 0-4 hours/week), and comorbid depression (OR 1.44; 95% CI 1.04-2.00).

Study details: Findings are from a survey study that analyzed the responses of 1065 adults with mostly moderate or severe AD.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by National Eczema Association. The authors declared serving as fiscal agents or receiving grants, sponsorships, honoraria, or other compensation from several sources, including the National Eczema Association.

Source: Elsawi R et al. The multidimensional burden of atopic dermatitis among adults: Results from a large national survey. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Jun 29). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1906

Key clinical point: Disease burden of atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with multiple factors, with the strongest association being with disease severity, time spent managing AD symptoms, and comorbid depression.

Major finding: Disease burden was strongly associated with AD severity (moderate: odds ratio [OR] 4.13; 95% CI 2.94-5.79 or severe: OR 13.63; 95% CI 8.65-21.5 vs mild AD), time spent managing AD symptoms (11-20 hours/week: OR 2.67; 95% CI 1.77-4.03 or ≥21 hours/week: OR 5.34; 95% CI 3.22-8.85 vs 0-4 hours/week), and comorbid depression (OR 1.44; 95% CI 1.04-2.00).

Study details: Findings are from a survey study that analyzed the responses of 1065 adults with mostly moderate or severe AD.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by National Eczema Association. The authors declared serving as fiscal agents or receiving grants, sponsorships, honoraria, or other compensation from several sources, including the National Eczema Association.

Source: Elsawi R et al. The multidimensional burden of atopic dermatitis among adults: Results from a large national survey. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Jun 29). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1906

Key clinical point: Disease burden of atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with multiple factors, with the strongest association being with disease severity, time spent managing AD symptoms, and comorbid depression.

Major finding: Disease burden was strongly associated with AD severity (moderate: odds ratio [OR] 4.13; 95% CI 2.94-5.79 or severe: OR 13.63; 95% CI 8.65-21.5 vs mild AD), time spent managing AD symptoms (11-20 hours/week: OR 2.67; 95% CI 1.77-4.03 or ≥21 hours/week: OR 5.34; 95% CI 3.22-8.85 vs 0-4 hours/week), and comorbid depression (OR 1.44; 95% CI 1.04-2.00).

Study details: Findings are from a survey study that analyzed the responses of 1065 adults with mostly moderate or severe AD.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by National Eczema Association. The authors declared serving as fiscal agents or receiving grants, sponsorships, honoraria, or other compensation from several sources, including the National Eczema Association.

Source: Elsawi R et al. The multidimensional burden of atopic dermatitis among adults: Results from a large national survey. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Jun 29). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1906

What are your treatment options when isotretinoin fails?

INDIANAPOLIS – – which is known to increase the drug’s bioavailability, advises James R. Treat, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We see lots of teenagers who are on a restrictive diet,” which is “certainly one reason they could be failing isotretinoin,” Dr. Treat said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Often, patients say that they have been referred to him because they had no response to 20 mg or 30 mg per day of isotretinoin. But after a dose escalation to 60 mg per day, their acne worsened.

If the patient’s acne is worsening with a cystic flare, “tripling the dose of isotretinoin is not something that you should do,” Dr. Treat said. “You should lower the dose and consider adding steroids.” For evidence-based recommendations on managing acne fulminans, he recommended an article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017.

Skin picking is another common reason for failure of isotretinoin, as well as with other acne therapies. These patients may have associated anxiety, which “might be a contraindication or at least something to consider before you put them on isotretinoin,” he noted.

In his experience, off-label use of N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant and cysteine prodrug, has been “extremely effective” for patients with excoriation disorder. In a randomized trial of adults 18-60 years of age, 47% patients who took 1,200-3,000 mg per day doses of N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks reported that their skin picking was much or very much improved, compared to 19% of those who took placebo (P = .03). The authors wrote that N-acetylcysteine “increases extracellular levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens,” and that these results support the hypothesis that “pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.”

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha blocker adalimumab is a reasonable option for patients with severe cystic inflammatory acne who fail isotretinoin, Dr. Treat said. In one published case, clinicians administered adalimumab 40 mg every other week for a 16-year-old male patient who received isotretinoin for moderate acne vulgaris, which caused sudden development of acne fulminans and incapacitating acute sacroiliitis with bilateral hip arthritis. Inflammatory lesions started to clear in 1 month and comedones improved by 3 months of treatment. Adalimumab was discontinued after 1 year and the patient remained clear.

“There are now multiple reports as well as some case series showing TNF-alpha agents causing clearance of acne,” said Dr. Treat, who directs the hospital’s pediatric dermatology fellowship program. A literature review of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for treatment-resistant acne found that all agents had similar efficacy after 3-6 months of therapy. “We see this in our GI population, where TNF-alpha agents are helping their acne also,” he said. “We just have to augment it with some topical medications.”

Certain medications can drive the development of acne, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, lithium, MEK inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, systemic steroids, and unopposed progesterone contraceptives. Some genetic conditions also predispose patients to acne, including mutations in the NCSTN gene and trisomy 13.

Dr. Treat discussed one of his patients with severe acne who had trisomy 13. The patient failed 12 months of doxycycline and amoxicillin in combination with a topical retinoid. He also failed low- and high-dose isotretinoin in combination with prednisone, as well as oral dapsone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 3 months. He was started on adalimumab, but that was stopped after he flared. The patient is now maintained on ustekinumab monthly at a dose of 45 mg.

“I’ve only had a few patients where isotretinoin truly has failed,” Dr. Treat said. He described one patient with severe acne who had a hidradenitis-like appearance in his axilla and groin. “I treated with isotretinoin very gingerly in the beginning, [but] he flared significantly. I had given him concomitant steroids from the very beginning and transitioned to multiple different therapies – all of which failed.”

Next, Dr. Treat tried a course of systemic dapsone, and the patient responded nicely. “As an anti-inflammatory agent, dapsone is very reasonable” to consider, he said. “It’s something to add to your armamentarium.”

Dr. Treat disclosed that he is a consultant for Palvella and Regeneron. He has ownership interests in Matinas Biopharma Holdings, Axsome, Sorrento, and Amarin.

INDIANAPOLIS – – which is known to increase the drug’s bioavailability, advises James R. Treat, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We see lots of teenagers who are on a restrictive diet,” which is “certainly one reason they could be failing isotretinoin,” Dr. Treat said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Often, patients say that they have been referred to him because they had no response to 20 mg or 30 mg per day of isotretinoin. But after a dose escalation to 60 mg per day, their acne worsened.

If the patient’s acne is worsening with a cystic flare, “tripling the dose of isotretinoin is not something that you should do,” Dr. Treat said. “You should lower the dose and consider adding steroids.” For evidence-based recommendations on managing acne fulminans, he recommended an article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017.

Skin picking is another common reason for failure of isotretinoin, as well as with other acne therapies. These patients may have associated anxiety, which “might be a contraindication or at least something to consider before you put them on isotretinoin,” he noted.

In his experience, off-label use of N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant and cysteine prodrug, has been “extremely effective” for patients with excoriation disorder. In a randomized trial of adults 18-60 years of age, 47% patients who took 1,200-3,000 mg per day doses of N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks reported that their skin picking was much or very much improved, compared to 19% of those who took placebo (P = .03). The authors wrote that N-acetylcysteine “increases extracellular levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens,” and that these results support the hypothesis that “pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.”

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha blocker adalimumab is a reasonable option for patients with severe cystic inflammatory acne who fail isotretinoin, Dr. Treat said. In one published case, clinicians administered adalimumab 40 mg every other week for a 16-year-old male patient who received isotretinoin for moderate acne vulgaris, which caused sudden development of acne fulminans and incapacitating acute sacroiliitis with bilateral hip arthritis. Inflammatory lesions started to clear in 1 month and comedones improved by 3 months of treatment. Adalimumab was discontinued after 1 year and the patient remained clear.

“There are now multiple reports as well as some case series showing TNF-alpha agents causing clearance of acne,” said Dr. Treat, who directs the hospital’s pediatric dermatology fellowship program. A literature review of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for treatment-resistant acne found that all agents had similar efficacy after 3-6 months of therapy. “We see this in our GI population, where TNF-alpha agents are helping their acne also,” he said. “We just have to augment it with some topical medications.”

Certain medications can drive the development of acne, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, lithium, MEK inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, systemic steroids, and unopposed progesterone contraceptives. Some genetic conditions also predispose patients to acne, including mutations in the NCSTN gene and trisomy 13.

Dr. Treat discussed one of his patients with severe acne who had trisomy 13. The patient failed 12 months of doxycycline and amoxicillin in combination with a topical retinoid. He also failed low- and high-dose isotretinoin in combination with prednisone, as well as oral dapsone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 3 months. He was started on adalimumab, but that was stopped after he flared. The patient is now maintained on ustekinumab monthly at a dose of 45 mg.

“I’ve only had a few patients where isotretinoin truly has failed,” Dr. Treat said. He described one patient with severe acne who had a hidradenitis-like appearance in his axilla and groin. “I treated with isotretinoin very gingerly in the beginning, [but] he flared significantly. I had given him concomitant steroids from the very beginning and transitioned to multiple different therapies – all of which failed.”

Next, Dr. Treat tried a course of systemic dapsone, and the patient responded nicely. “As an anti-inflammatory agent, dapsone is very reasonable” to consider, he said. “It’s something to add to your armamentarium.”

Dr. Treat disclosed that he is a consultant for Palvella and Regeneron. He has ownership interests in Matinas Biopharma Holdings, Axsome, Sorrento, and Amarin.

INDIANAPOLIS – – which is known to increase the drug’s bioavailability, advises James R. Treat, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We see lots of teenagers who are on a restrictive diet,” which is “certainly one reason they could be failing isotretinoin,” Dr. Treat said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Often, patients say that they have been referred to him because they had no response to 20 mg or 30 mg per day of isotretinoin. But after a dose escalation to 60 mg per day, their acne worsened.

If the patient’s acne is worsening with a cystic flare, “tripling the dose of isotretinoin is not something that you should do,” Dr. Treat said. “You should lower the dose and consider adding steroids.” For evidence-based recommendations on managing acne fulminans, he recommended an article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017.

Skin picking is another common reason for failure of isotretinoin, as well as with other acne therapies. These patients may have associated anxiety, which “might be a contraindication or at least something to consider before you put them on isotretinoin,” he noted.

In his experience, off-label use of N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant and cysteine prodrug, has been “extremely effective” for patients with excoriation disorder. In a randomized trial of adults 18-60 years of age, 47% patients who took 1,200-3,000 mg per day doses of N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks reported that their skin picking was much or very much improved, compared to 19% of those who took placebo (P = .03). The authors wrote that N-acetylcysteine “increases extracellular levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens,” and that these results support the hypothesis that “pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.”

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha blocker adalimumab is a reasonable option for patients with severe cystic inflammatory acne who fail isotretinoin, Dr. Treat said. In one published case, clinicians administered adalimumab 40 mg every other week for a 16-year-old male patient who received isotretinoin for moderate acne vulgaris, which caused sudden development of acne fulminans and incapacitating acute sacroiliitis with bilateral hip arthritis. Inflammatory lesions started to clear in 1 month and comedones improved by 3 months of treatment. Adalimumab was discontinued after 1 year and the patient remained clear.

“There are now multiple reports as well as some case series showing TNF-alpha agents causing clearance of acne,” said Dr. Treat, who directs the hospital’s pediatric dermatology fellowship program. A literature review of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for treatment-resistant acne found that all agents had similar efficacy after 3-6 months of therapy. “We see this in our GI population, where TNF-alpha agents are helping their acne also,” he said. “We just have to augment it with some topical medications.”

Certain medications can drive the development of acne, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, lithium, MEK inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, systemic steroids, and unopposed progesterone contraceptives. Some genetic conditions also predispose patients to acne, including mutations in the NCSTN gene and trisomy 13.

Dr. Treat discussed one of his patients with severe acne who had trisomy 13. The patient failed 12 months of doxycycline and amoxicillin in combination with a topical retinoid. He also failed low- and high-dose isotretinoin in combination with prednisone, as well as oral dapsone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 3 months. He was started on adalimumab, but that was stopped after he flared. The patient is now maintained on ustekinumab monthly at a dose of 45 mg.

“I’ve only had a few patients where isotretinoin truly has failed,” Dr. Treat said. He described one patient with severe acne who had a hidradenitis-like appearance in his axilla and groin. “I treated with isotretinoin very gingerly in the beginning, [but] he flared significantly. I had given him concomitant steroids from the very beginning and transitioned to multiple different therapies – all of which failed.”

Next, Dr. Treat tried a course of systemic dapsone, and the patient responded nicely. “As an anti-inflammatory agent, dapsone is very reasonable” to consider, he said. “It’s something to add to your armamentarium.”

Dr. Treat disclosed that he is a consultant for Palvella and Regeneron. He has ownership interests in Matinas Biopharma Holdings, Axsome, Sorrento, and Amarin.

AT SPD 2022

Scientists aim to combat COVID with a shot in the nose

Scientists seeking to stay ahead of an evolving SARS-Cov-2 virus are looking at new strategies, including developing intranasal vaccines, according to speakers at a conference on July 26.

inviting researchers to provide a public update on efforts to try to keep ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists and federal officials are looking to build on the successes seen in developing the original crop of COVID vaccines, which were authorized for use in the United States less than a year after the pandemic took hold.

But emerging variants are eroding these gains. For months now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have been keeping an eye on how the level of effectiveness of COVID vaccines has waned during the rise of the Omicron strain. And there’s continual concern about how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over time.

“Our vaccines are terrific,” Ashish K. Jha, MD, the White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, said at the summit. “[But] we have to do better.”

Among the approaches being considered are vaccines that would be applied intranasally, with the idea that this might be able to boost the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

At the summit, Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the intranasal approach might be helpful in preventing transmission as well as reducing the burden of illness for those who are infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re stopping the virus from spreading right at the border,” Dr. Iwasaki said at the summit. “This is akin to putting a guard outside of the house in order to patrol for invaders compared to putting the guards in the hallway of the building in the hope that they capture the invader.”

Dr. Iwasaki is one of the founders of Xanadu Bio, a private company created last year to focus on ways to kill SARS-CoV-2 in the nasosinus before it spreads deeper into the respiratory tract. In an editorial in Science Immunology, Dr. Iwasaki and Eric J. Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, urged greater federal investment in this approach to fighting SARS-CoV-2. (Dr. Topol is editor-in-chief of Medscape.)

Titled “Operation Nasal Vaccine – Lightning speed to counter COVID-19,” their editorial noted the “unprecedented success” seen in the rapid development of the first two mRNA shots. Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol noted that these victories had been “fueled by the $10 billion governmental investment in Operation Warp Speed.

“During the first year of the pandemic, meaningful evolution of the virus was slow-paced, without any functional consequences, but since that time we have seen a succession of important variants of concern, with increasing transmissibility and immune evasion, culminating in the Omicron lineages,” wrote Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol.

Recent developments have “spotlighted the possibility of nasal vaccines, with their allure for achieving mucosal immunity, complementing, and likely bolstering the circulating immunity achieved via intramuscular shots,” they added.

An early setback

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have for some time been looking to vet an array of next-generation vaccine concepts, including ones that trigger mucosal immunity, the Washington Post reported in April.

At the summit on July 26, several participants, including Dr. Jha, stressed the role that public-private partnerships were key to the rapid development of the initial COVID vaccines. They said continued U.S. government support will be needed to make advances in this field.

One of the presenters, Biao He, PhD, founder and president of CyanVac and Blue Lake Biotechnology, spoke of the federal support that his efforts have received over the years to develop intranasal vaccines. His Georgia-based firm already has an experimental intranasal vaccine candidate, CVXGA1-001, in phase 1 testing (NCT04954287).

The CVXGA-001 builds on technology already used in a veterinary product, an intranasal vaccine long used to prevent kennel cough in dogs, he said at the summit.

The emerging field of experimental intranasal COVID vaccines already has had at least one setback.

The biotech firm Altimmune in June 2021 announced that it would discontinue development of its experimental intranasal AdCOVID vaccine following disappointing phase 1 results. The vaccine appeared to be well tolerated in the test, but the immunogenicity data demonstrated lower than expected results in healthy volunteers, especially in light of the responses seen to already cleared vaccines, Altimmune said in a release.

In the statement, Scot Roberts, PhD, chief scientific officer at Altimmune, noted that the study participants lacked immunity from prior infection or vaccination. “We believe that prior immunity in humans may be important for a robust immune response to intranasal dosing with AdCOVID,” he said.

At the summit, Marty Moore, PhD, cofounder and chief scientific officer for Redwood City, Calif.–based Meissa Vaccines, noted the challenges that remain ahead for intranasal COVID vaccines, while also highlighting what he sees as the potential of this approach.

Meissa also has advanced an experimental intranasal COVID vaccine as far as phase 1 testing (NCT04798001).

“No one here today can tell you that mucosal COVID vaccines work. We’re not there yet. We need clinical efficacy data to answer that question,” Dr. Moore said.

But there’s a potential for a “knockout blow to COVID, a transmission-blocking vaccine” from the intranasal approach, he said.

“The virus is mutating faster than our ability to manage vaccines and not enough people are getting boosters. These injectable vaccines do a great job of preventing severe disease, but they do little to prevent infection” from spreading, Dr. Moore said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists seeking to stay ahead of an evolving SARS-Cov-2 virus are looking at new strategies, including developing intranasal vaccines, according to speakers at a conference on July 26.

inviting researchers to provide a public update on efforts to try to keep ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists and federal officials are looking to build on the successes seen in developing the original crop of COVID vaccines, which were authorized for use in the United States less than a year after the pandemic took hold.

But emerging variants are eroding these gains. For months now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have been keeping an eye on how the level of effectiveness of COVID vaccines has waned during the rise of the Omicron strain. And there’s continual concern about how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over time.

“Our vaccines are terrific,” Ashish K. Jha, MD, the White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, said at the summit. “[But] we have to do better.”

Among the approaches being considered are vaccines that would be applied intranasally, with the idea that this might be able to boost the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

At the summit, Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the intranasal approach might be helpful in preventing transmission as well as reducing the burden of illness for those who are infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re stopping the virus from spreading right at the border,” Dr. Iwasaki said at the summit. “This is akin to putting a guard outside of the house in order to patrol for invaders compared to putting the guards in the hallway of the building in the hope that they capture the invader.”

Dr. Iwasaki is one of the founders of Xanadu Bio, a private company created last year to focus on ways to kill SARS-CoV-2 in the nasosinus before it spreads deeper into the respiratory tract. In an editorial in Science Immunology, Dr. Iwasaki and Eric J. Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, urged greater federal investment in this approach to fighting SARS-CoV-2. (Dr. Topol is editor-in-chief of Medscape.)

Titled “Operation Nasal Vaccine – Lightning speed to counter COVID-19,” their editorial noted the “unprecedented success” seen in the rapid development of the first two mRNA shots. Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol noted that these victories had been “fueled by the $10 billion governmental investment in Operation Warp Speed.

“During the first year of the pandemic, meaningful evolution of the virus was slow-paced, without any functional consequences, but since that time we have seen a succession of important variants of concern, with increasing transmissibility and immune evasion, culminating in the Omicron lineages,” wrote Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol.

Recent developments have “spotlighted the possibility of nasal vaccines, with their allure for achieving mucosal immunity, complementing, and likely bolstering the circulating immunity achieved via intramuscular shots,” they added.

An early setback

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have for some time been looking to vet an array of next-generation vaccine concepts, including ones that trigger mucosal immunity, the Washington Post reported in April.

At the summit on July 26, several participants, including Dr. Jha, stressed the role that public-private partnerships were key to the rapid development of the initial COVID vaccines. They said continued U.S. government support will be needed to make advances in this field.

One of the presenters, Biao He, PhD, founder and president of CyanVac and Blue Lake Biotechnology, spoke of the federal support that his efforts have received over the years to develop intranasal vaccines. His Georgia-based firm already has an experimental intranasal vaccine candidate, CVXGA1-001, in phase 1 testing (NCT04954287).

The CVXGA-001 builds on technology already used in a veterinary product, an intranasal vaccine long used to prevent kennel cough in dogs, he said at the summit.

The emerging field of experimental intranasal COVID vaccines already has had at least one setback.

The biotech firm Altimmune in June 2021 announced that it would discontinue development of its experimental intranasal AdCOVID vaccine following disappointing phase 1 results. The vaccine appeared to be well tolerated in the test, but the immunogenicity data demonstrated lower than expected results in healthy volunteers, especially in light of the responses seen to already cleared vaccines, Altimmune said in a release.

In the statement, Scot Roberts, PhD, chief scientific officer at Altimmune, noted that the study participants lacked immunity from prior infection or vaccination. “We believe that prior immunity in humans may be important for a robust immune response to intranasal dosing with AdCOVID,” he said.

At the summit, Marty Moore, PhD, cofounder and chief scientific officer for Redwood City, Calif.–based Meissa Vaccines, noted the challenges that remain ahead for intranasal COVID vaccines, while also highlighting what he sees as the potential of this approach.

Meissa also has advanced an experimental intranasal COVID vaccine as far as phase 1 testing (NCT04798001).

“No one here today can tell you that mucosal COVID vaccines work. We’re not there yet. We need clinical efficacy data to answer that question,” Dr. Moore said.

But there’s a potential for a “knockout blow to COVID, a transmission-blocking vaccine” from the intranasal approach, he said.

“The virus is mutating faster than our ability to manage vaccines and not enough people are getting boosters. These injectable vaccines do a great job of preventing severe disease, but they do little to prevent infection” from spreading, Dr. Moore said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists seeking to stay ahead of an evolving SARS-Cov-2 virus are looking at new strategies, including developing intranasal vaccines, according to speakers at a conference on July 26.

inviting researchers to provide a public update on efforts to try to keep ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists and federal officials are looking to build on the successes seen in developing the original crop of COVID vaccines, which were authorized for use in the United States less than a year after the pandemic took hold.

But emerging variants are eroding these gains. For months now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have been keeping an eye on how the level of effectiveness of COVID vaccines has waned during the rise of the Omicron strain. And there’s continual concern about how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over time.

“Our vaccines are terrific,” Ashish K. Jha, MD, the White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, said at the summit. “[But] we have to do better.”

Among the approaches being considered are vaccines that would be applied intranasally, with the idea that this might be able to boost the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

At the summit, Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the intranasal approach might be helpful in preventing transmission as well as reducing the burden of illness for those who are infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re stopping the virus from spreading right at the border,” Dr. Iwasaki said at the summit. “This is akin to putting a guard outside of the house in order to patrol for invaders compared to putting the guards in the hallway of the building in the hope that they capture the invader.”

Dr. Iwasaki is one of the founders of Xanadu Bio, a private company created last year to focus on ways to kill SARS-CoV-2 in the nasosinus before it spreads deeper into the respiratory tract. In an editorial in Science Immunology, Dr. Iwasaki and Eric J. Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, urged greater federal investment in this approach to fighting SARS-CoV-2. (Dr. Topol is editor-in-chief of Medscape.)

Titled “Operation Nasal Vaccine – Lightning speed to counter COVID-19,” their editorial noted the “unprecedented success” seen in the rapid development of the first two mRNA shots. Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol noted that these victories had been “fueled by the $10 billion governmental investment in Operation Warp Speed.

“During the first year of the pandemic, meaningful evolution of the virus was slow-paced, without any functional consequences, but since that time we have seen a succession of important variants of concern, with increasing transmissibility and immune evasion, culminating in the Omicron lineages,” wrote Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol.

Recent developments have “spotlighted the possibility of nasal vaccines, with their allure for achieving mucosal immunity, complementing, and likely bolstering the circulating immunity achieved via intramuscular shots,” they added.

An early setback

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have for some time been looking to vet an array of next-generation vaccine concepts, including ones that trigger mucosal immunity, the Washington Post reported in April.

At the summit on July 26, several participants, including Dr. Jha, stressed the role that public-private partnerships were key to the rapid development of the initial COVID vaccines. They said continued U.S. government support will be needed to make advances in this field.

One of the presenters, Biao He, PhD, founder and president of CyanVac and Blue Lake Biotechnology, spoke of the federal support that his efforts have received over the years to develop intranasal vaccines. His Georgia-based firm already has an experimental intranasal vaccine candidate, CVXGA1-001, in phase 1 testing (NCT04954287).

The CVXGA-001 builds on technology already used in a veterinary product, an intranasal vaccine long used to prevent kennel cough in dogs, he said at the summit.

The emerging field of experimental intranasal COVID vaccines already has had at least one setback.

The biotech firm Altimmune in June 2021 announced that it would discontinue development of its experimental intranasal AdCOVID vaccine following disappointing phase 1 results. The vaccine appeared to be well tolerated in the test, but the immunogenicity data demonstrated lower than expected results in healthy volunteers, especially in light of the responses seen to already cleared vaccines, Altimmune said in a release.

In the statement, Scot Roberts, PhD, chief scientific officer at Altimmune, noted that the study participants lacked immunity from prior infection or vaccination. “We believe that prior immunity in humans may be important for a robust immune response to intranasal dosing with AdCOVID,” he said.

At the summit, Marty Moore, PhD, cofounder and chief scientific officer for Redwood City, Calif.–based Meissa Vaccines, noted the challenges that remain ahead for intranasal COVID vaccines, while also highlighting what he sees as the potential of this approach.

Meissa also has advanced an experimental intranasal COVID vaccine as far as phase 1 testing (NCT04798001).

“No one here today can tell you that mucosal COVID vaccines work. We’re not there yet. We need clinical efficacy data to answer that question,” Dr. Moore said.

But there’s a potential for a “knockout blow to COVID, a transmission-blocking vaccine” from the intranasal approach, he said.

“The virus is mutating faster than our ability to manage vaccines and not enough people are getting boosters. These injectable vaccines do a great job of preventing severe disease, but they do little to prevent infection” from spreading, Dr. Moore said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonphysician Clinicians in Dermatology Residencies: Cross-sectional Survey on Residency Education

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

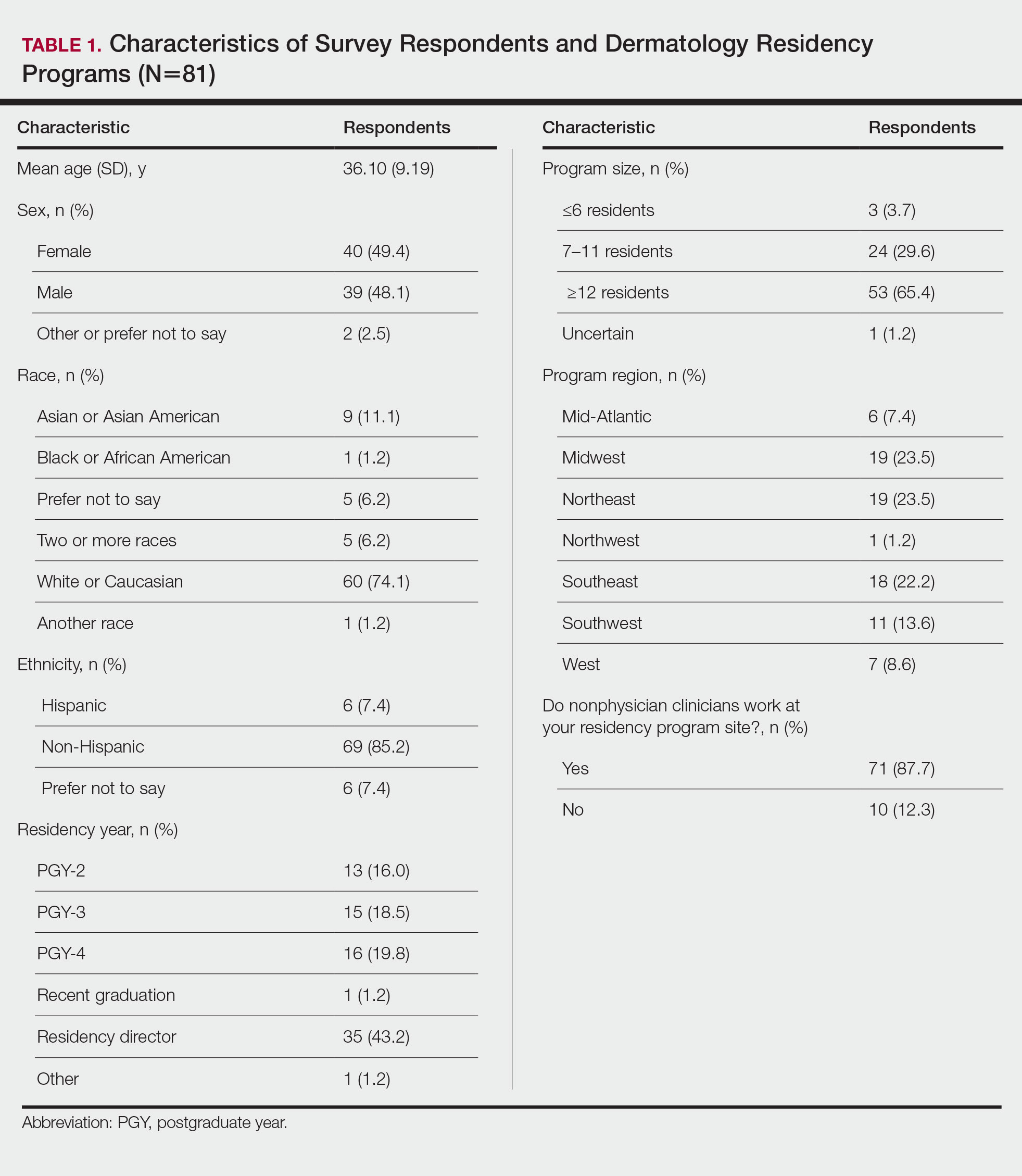

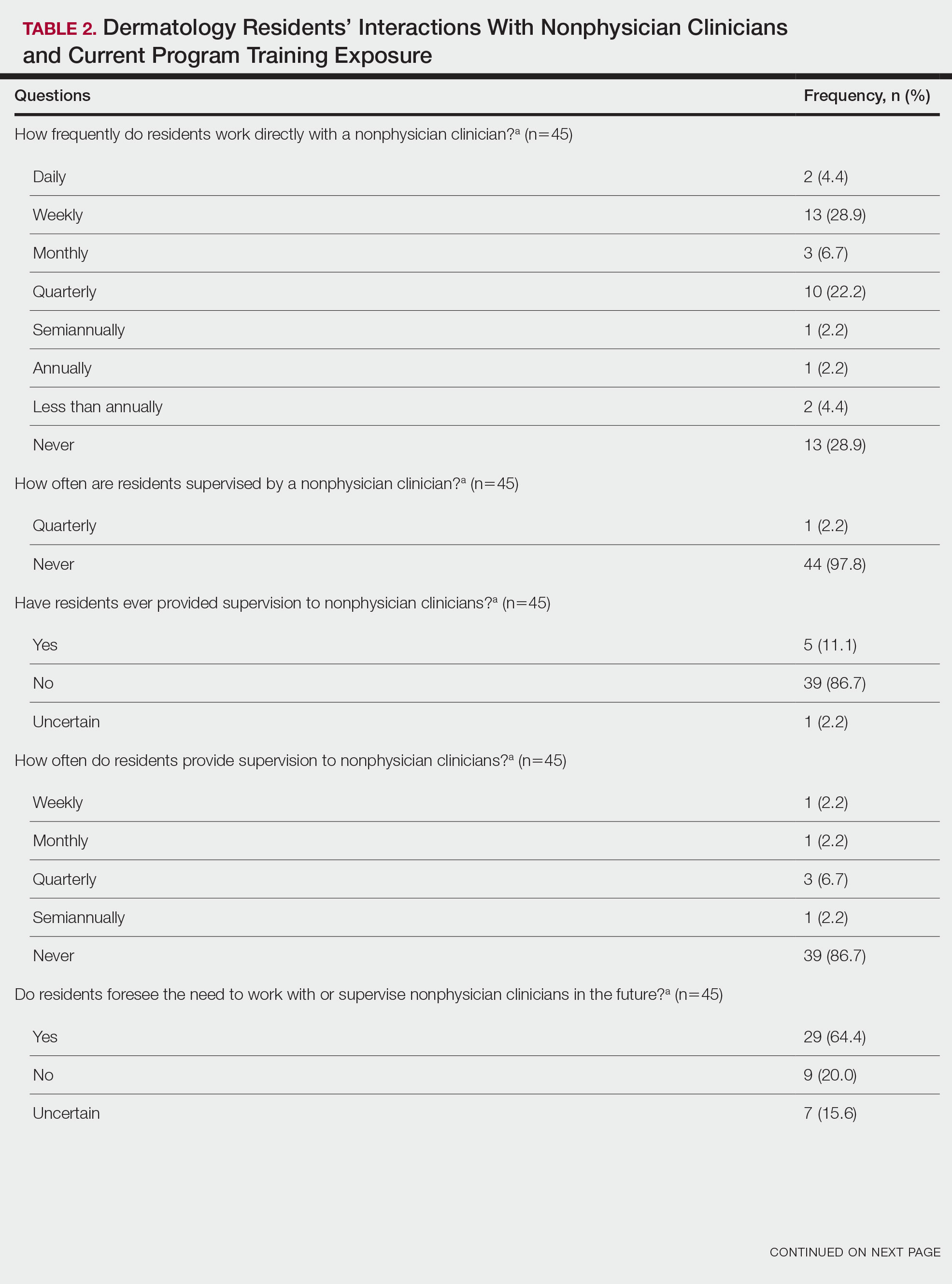

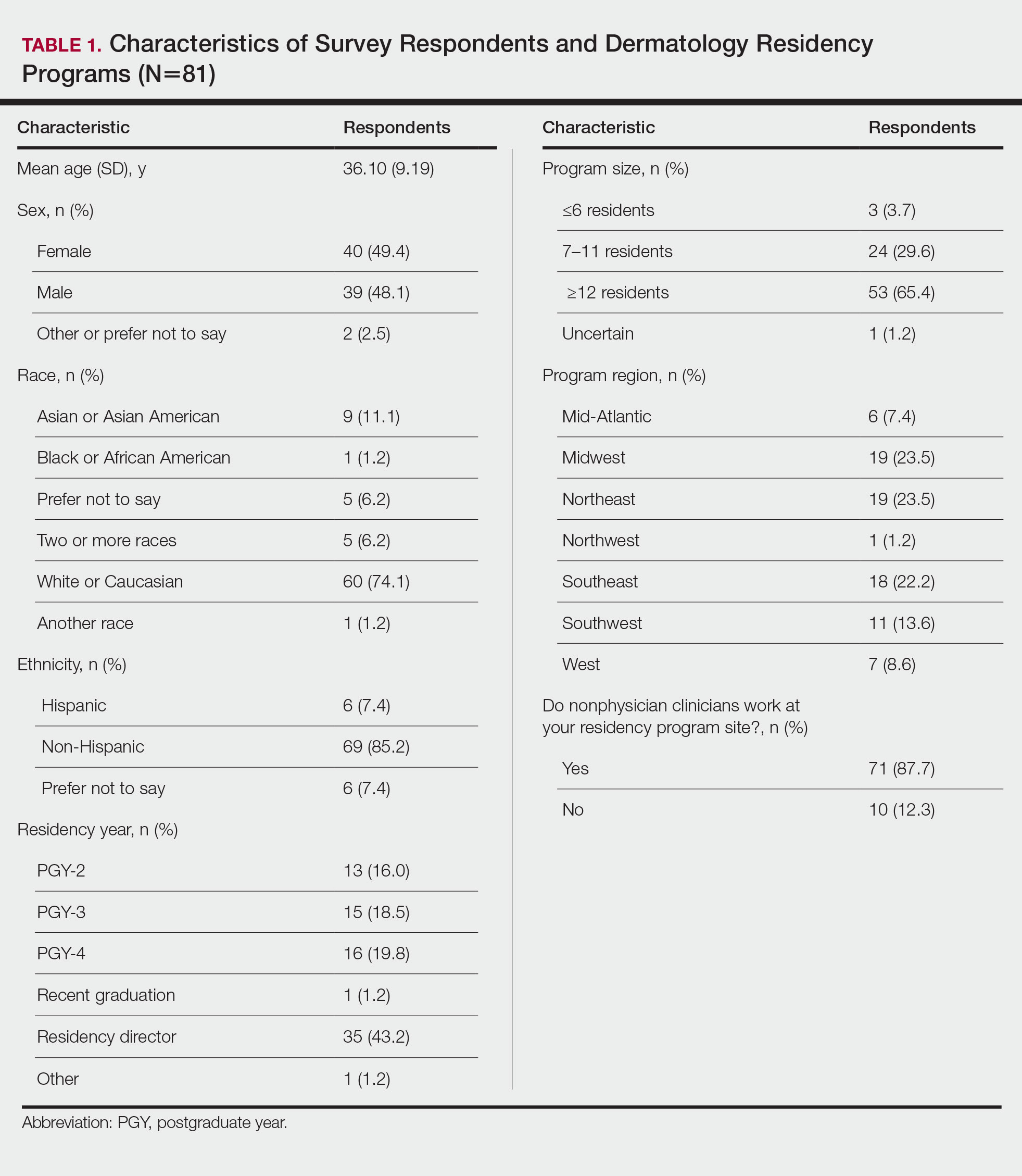

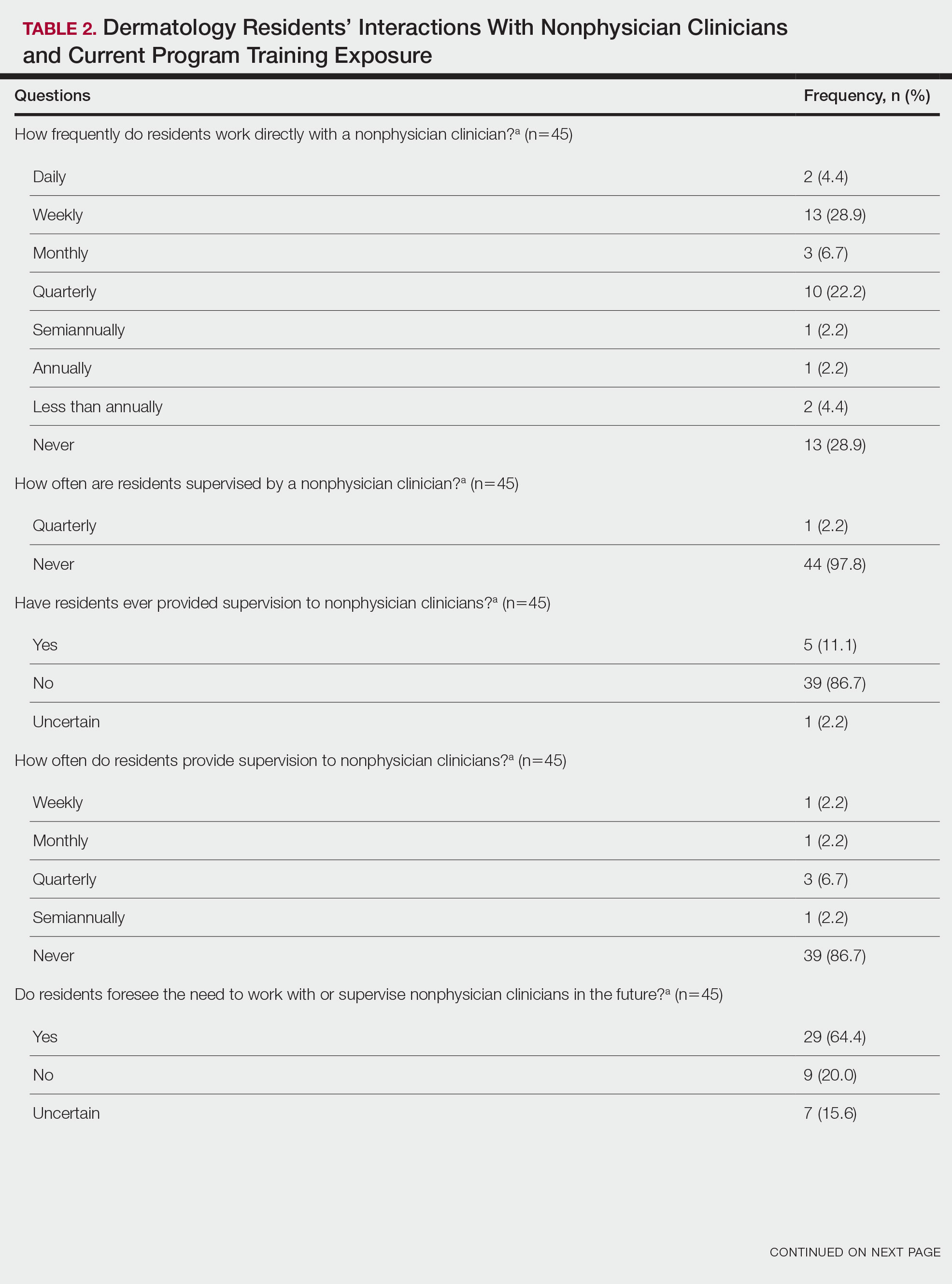

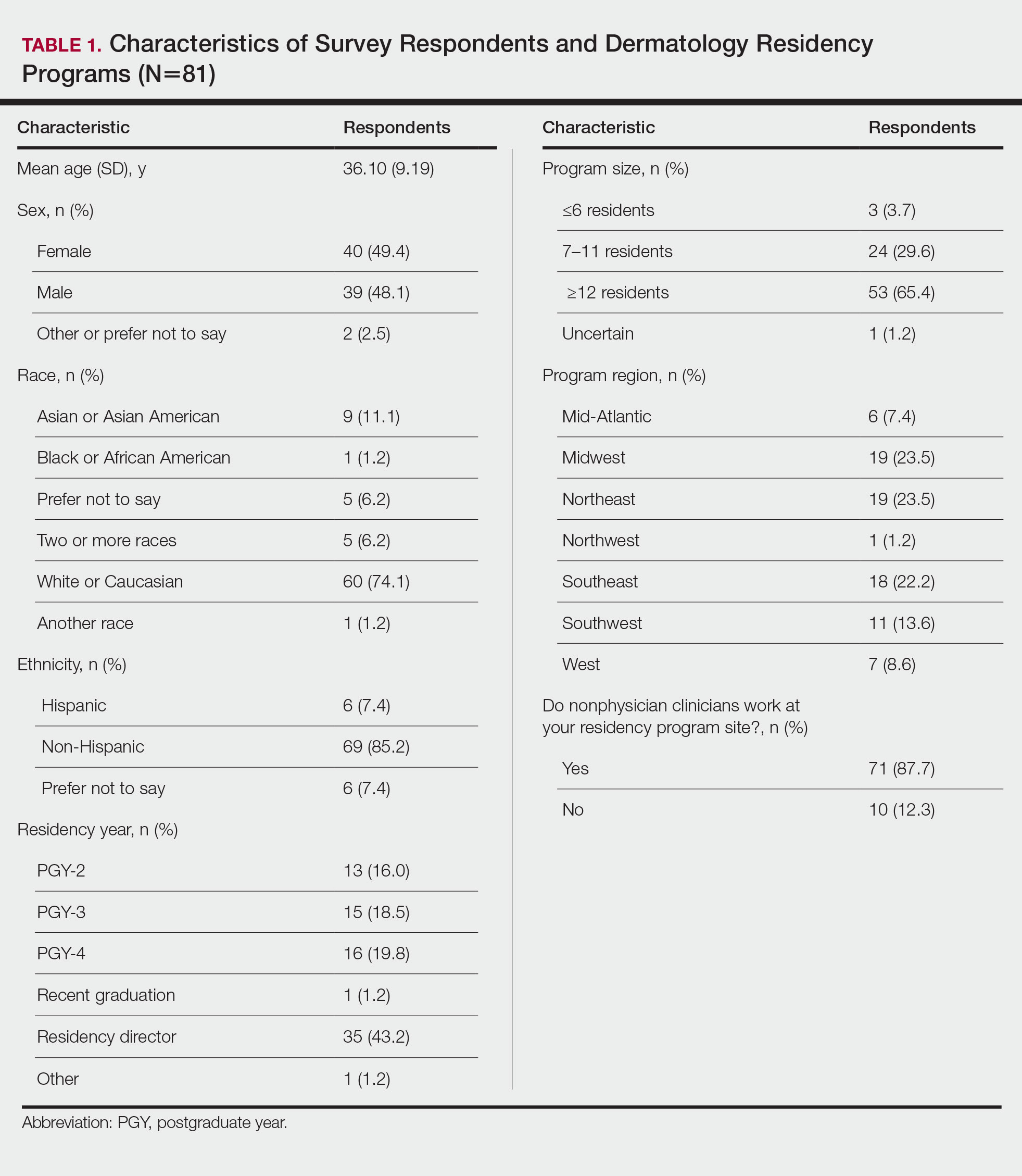

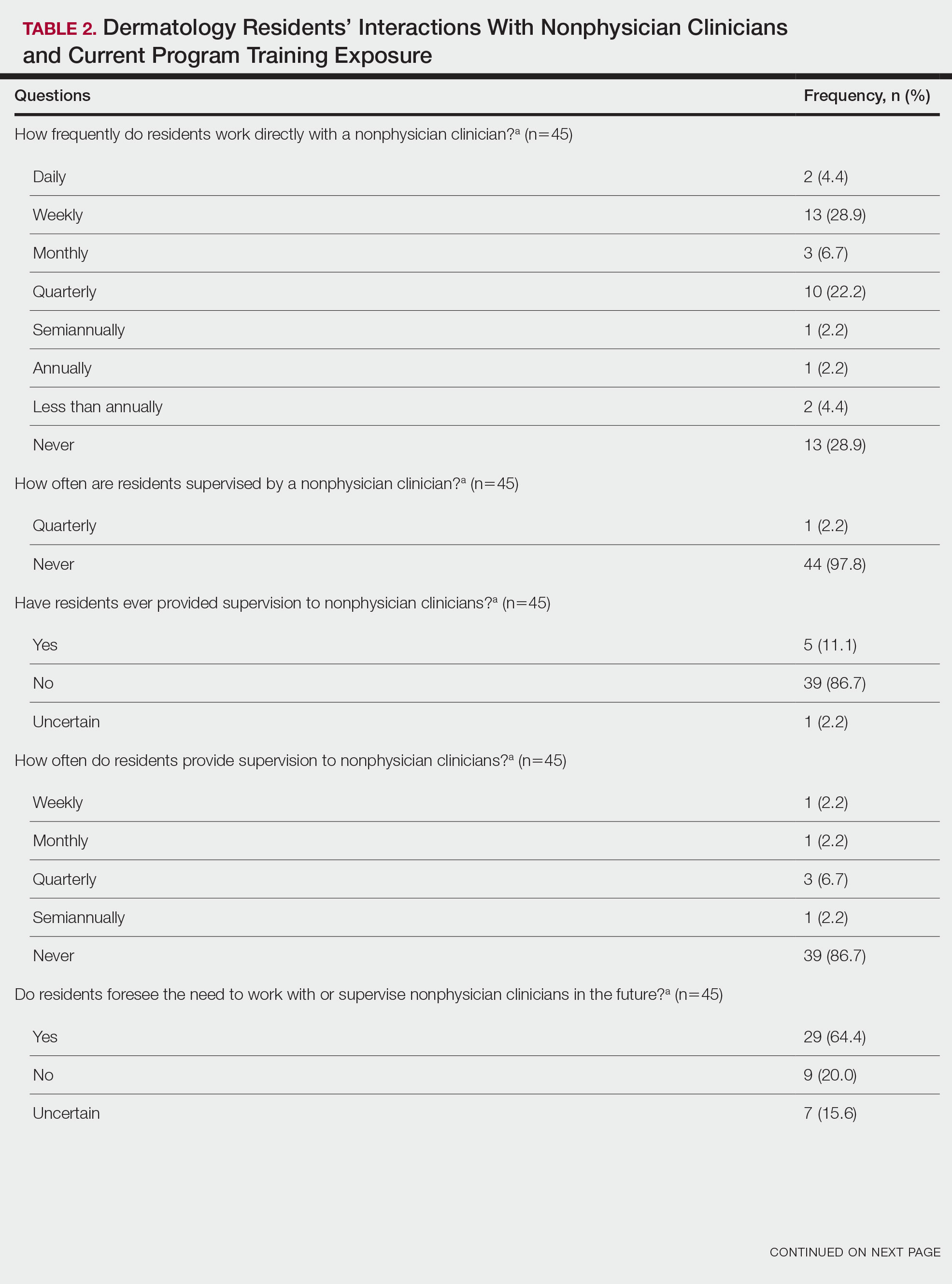

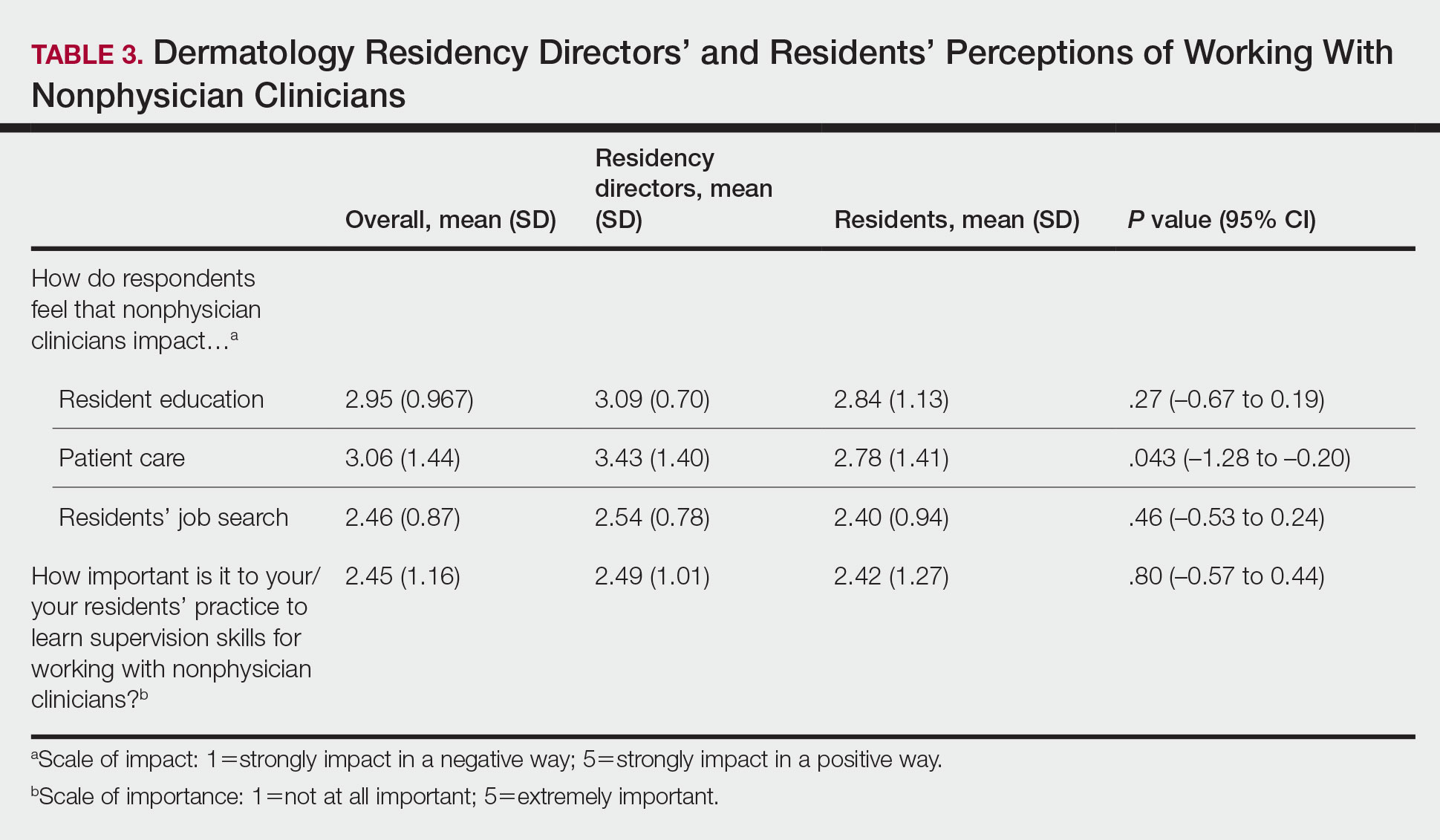

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

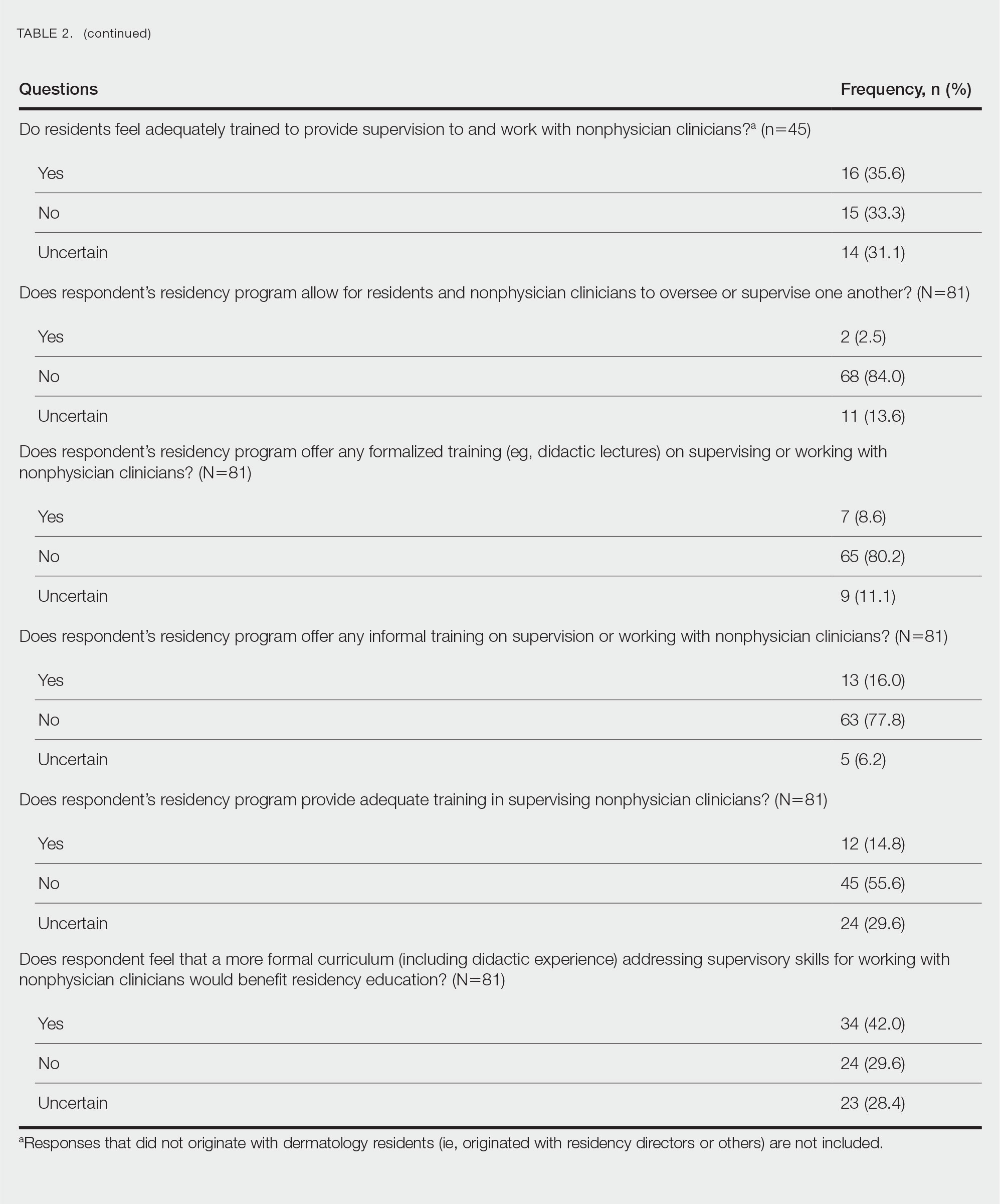

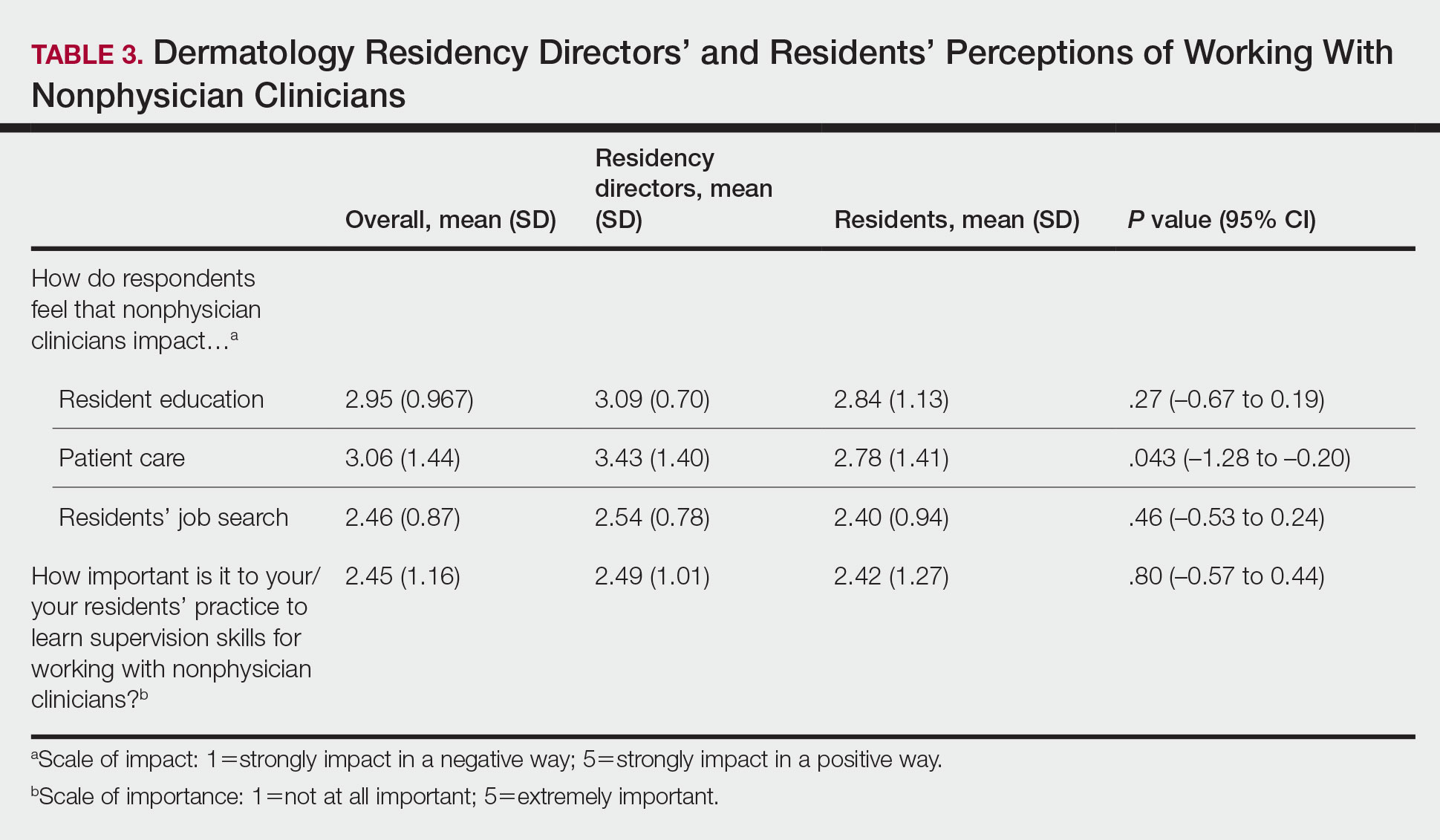

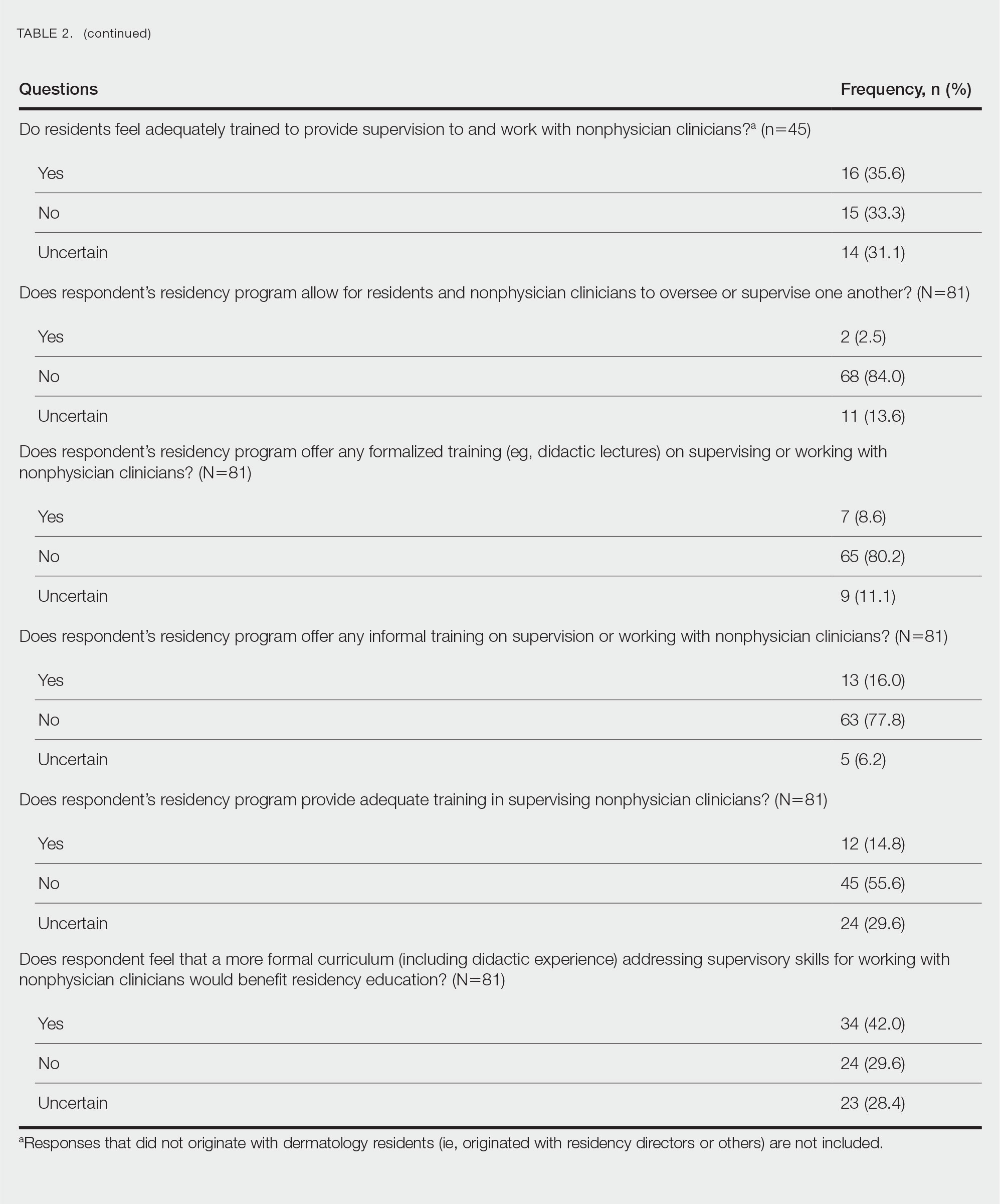

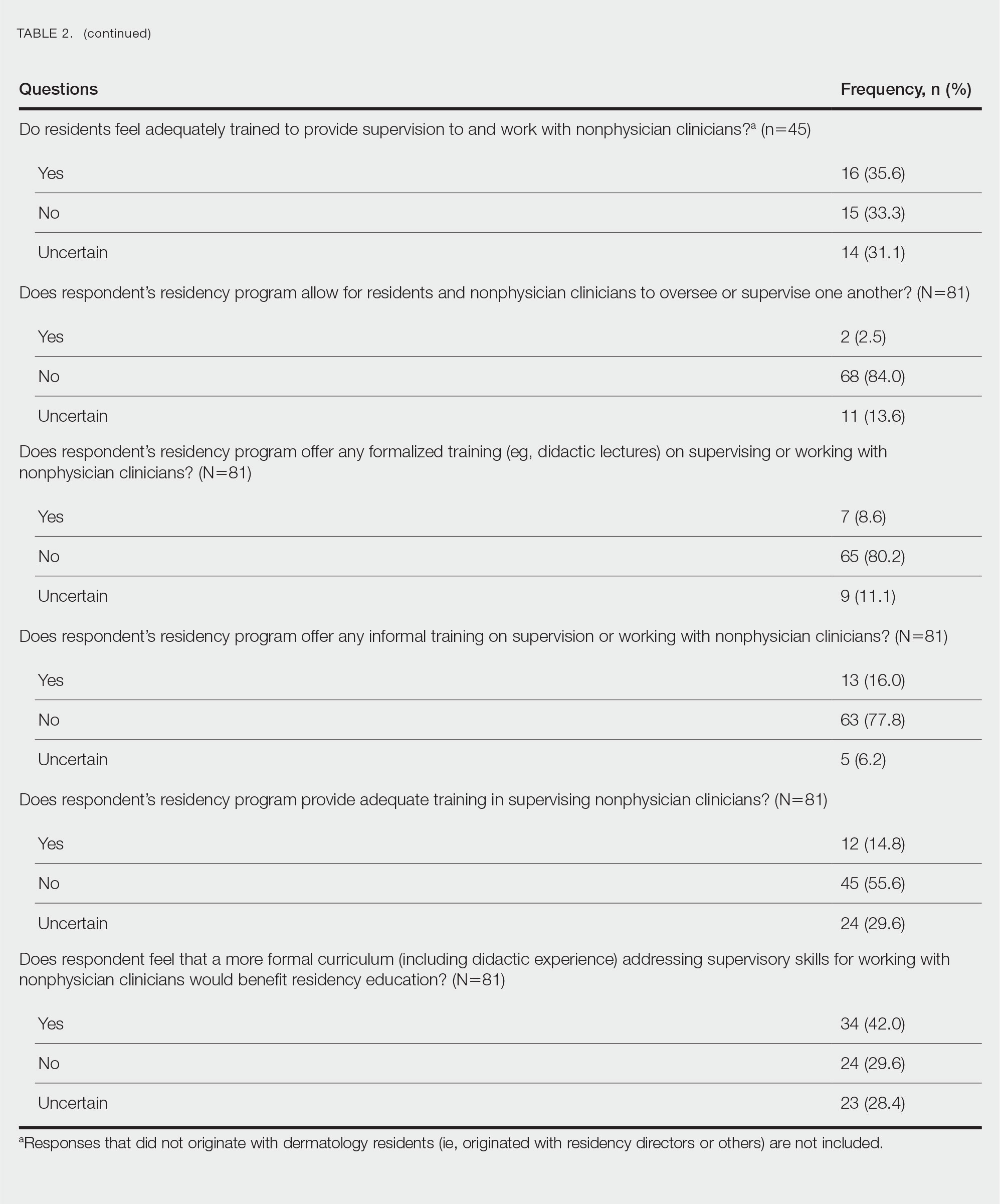

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

Practice Points

- Most dermatology residency programs do not offer training on working with and supervising nonphysician clinicians.

- Dermatology residents think that formal training in supervising nonphysician clinicians would be a beneficial addition to the residency curriculum.

U.S. News issues top hospitals list, now with expanded health equity measures

For the seventh consecutive year, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., took the top spot in the annual honor roll of best hospitals, published July 26 by U.S. News & World Report.

The 2022 rankings, which marks the 33rd edition, showcase several methodology changes, including new ratings for ovarian, prostate, and uterine cancer surgeries that “provide patients ... with previously unavailable information to assist them in making a critical health care decision,” a news release from the publication explains.

said the release. Finally, a new metric called “home time” determines how successfully each hospital helps patients return home.

Mayo Clinic remains No. 1

For the 2022-2023 rankings and ratings, U.S. News compared more than 4,500 medical centers across the country in 15 specialties and 20 procedures and conditions. Of these, 493 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals as a result of their overall strong performance.

The list was then narrowed to the top 20 hospitals, outlined in the honor roll below, that deliver “exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.”

Following Mayo Clinic in the annual ranking’s top spot, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles rises from No. 6 to No. 2, and New York University Langone Hospitals finish third, up from eighth in 2021.

Cleveland Clinic in Ohio holds the No. 4 spot, down two from 2021, while Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles tie for fifth place. Rounding out the top 10, in order, are: New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago; Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital.

The following hospitals complete the top 20 in the United States:

- 11. Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- 12. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- 13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

- 14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- 15. Houston Methodist Hospital

- 16. Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- 17. University of Michigan Health–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor

- 18. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix

- 19. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

- 20. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

For the specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, remains No. 1 in cancer care, the Cleveland Clinic is No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery, and the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York is No. 1 in orthopedics.

Top five for cancer

- 1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

- 2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

- 3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 4. Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

- 5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

- 1. Cleveland Clinic

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

- 5. New York University Langone Hospitals

Top five for orthopedics

- 1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York University Langone Hospitals

- 5. (tie) Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- 5. (tie) UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

According to the news release, the procedures and conditions ratings are based entirely on objective patient care measures like survival rates, patient experience, home time, and level of nursing care. The Best Hospitals rankings consider a variety of data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, American Hospital Association, professional organizations, and medical specialists.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For the seventh consecutive year, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., took the top spot in the annual honor roll of best hospitals, published July 26 by U.S. News & World Report.

The 2022 rankings, which marks the 33rd edition, showcase several methodology changes, including new ratings for ovarian, prostate, and uterine cancer surgeries that “provide patients ... with previously unavailable information to assist them in making a critical health care decision,” a news release from the publication explains.

said the release. Finally, a new metric called “home time” determines how successfully each hospital helps patients return home.

Mayo Clinic remains No. 1

For the 2022-2023 rankings and ratings, U.S. News compared more than 4,500 medical centers across the country in 15 specialties and 20 procedures and conditions. Of these, 493 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals as a result of their overall strong performance.

The list was then narrowed to the top 20 hospitals, outlined in the honor roll below, that deliver “exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.”

Following Mayo Clinic in the annual ranking’s top spot, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles rises from No. 6 to No. 2, and New York University Langone Hospitals finish third, up from eighth in 2021.

Cleveland Clinic in Ohio holds the No. 4 spot, down two from 2021, while Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles tie for fifth place. Rounding out the top 10, in order, are: New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago; Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital.

The following hospitals complete the top 20 in the United States: