User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Cannabis in Cancer: What Oncologists and Patients Should Know

first, and oncologists may be hesitant to broach the topic with their patients.

Updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) on the use of cannabis and cannabinoids in adults with cancer stress that it’s an important conversation to have.

According to the ASCO expert panel, access to and use of cannabis alongside cancer care have outpaced the science on evidence-based indications, and overall high-quality data on the effects of cannabis during cancer care are lacking. While several observational studies support cannabis use to help ease chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, the literature remains more divided on other potential benefits, such as alleviating cancer pain and sleep problems, and some evidence points to potential downsides of cannabis use.

Oncologists should “absolutely talk to patients” about cannabis, Brooke Worster, MD, medical director for the Master of Science in Medical Cannabis Science & Business program at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, told Medscape Medical News.

“Patients are interested, and they are going to find access to information. As a medical professional, it’s our job to help guide them through these spaces in a safe, nonjudgmental way.”

But, Worster noted, oncologists don’t have to be experts on cannabis to begin the conversation with patients.

So, “let yourself off the hook,” Worster urged.

Plus, avoiding the conversation won’t stop patients from using cannabis. In a recent study, Worster and her colleagues found that nearly one third of patients at 12 National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers had used cannabis since their diagnosis — most often for sleep disturbance, pain, stress, and anxiety. Most (60%) felt somewhat or extremely comfortable talking to their healthcare provider about it, but only 21.5% said they had done so. Even fewer — about 10% — had talked to their treating oncologist.

Because patients may not discuss cannabis use, it’s especially important for oncologists to open up a line of communication, said Worster, also the enterprise director of supportive oncology at the Thomas Jefferson University.

Evidence on Cannabis During Cancer Care

A substantial proportion of people with cancer believe cannabis can help manage cancer-related symptoms.

In Worster’s recent survey study, regardless of whether patients had used cannabis, almost 90% of those surveyed reported a perceived benefit. Although 65% also reported perceived risks for cannabis use, including difficulty concentrating, lung damage, and impaired memory, the perceived benefits outweighed the risks.

Despite generally positive perceptions, the overall literature on the benefits of cannabis in patients with cancer paints a less clear picture.

The ASCO guidelines, which were based on 13 systematic reviews and five additional primary studies, reported that cannabis can improve refractory, chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting when added to guideline-concordant antiemetic regimens, but that there is no clear evidence of benefit or harm for other supportive care outcomes.

The “certainty of evidence for most outcomes was low or very low,” the ASCO authors wrote.

The ASCO experts explained that, outside the context of a clinical trial, the evidence is not sufficient to recommend cannabis or cannabinoids for managing cancer pain, sleep issues, appetite loss, or anxiety and depression. For these outcomes, some studies indicate a benefit, while others don’t.

Real-world data from a large registry study, for instance, have indicated that medical cannabis is “a safe and effective complementary treatment for pain relief in patients with cancer.” However, a 2020 meta-analysis found that, in studies with a low risk for bias, adding cannabinoids to opioids did not reduce cancer pain in adults with advanced cancer.

There can be downsides to cannabis use, too. In one recent study, some patients reported feeling worse physically and psychologically compared with those who didn’t use cannabis. Another study found that oral cannabis was associated with “bothersome” side effects, including sedation, dizziness, and transient anxiety.

The ASCO guidelines also made it clear that cannabis or cannabinoids should not be used as cancer-directed treatment, outside of a clinical trial.

Talking to Patients About Cannabis

Given the level of evidence and patient interest in cannabis, it is important for oncologists to raise the topic of cannabis use with their patients.

To help inform decision-making and approaches to care, the ASCO guidelines suggest that oncologists can guide care themselves or direct patients to appropriate “unbiased, evidence-based” resources. For those who use cannabis or cannabinoids outside of evidence-based indications or clinician recommendations, it’s important to explore patients’ goals, educate them, and try to minimize harm.

One strategy for broaching the topic, Worster suggested, is to simply ask patients if they have tried or considered trying cannabis to control symptoms like nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, or cancer pain.

The conversation with patients should then include an overview of the potential benefits and potential risks for cannabis use as well as risk reduction strategies, Worster noted.

But “approach it in an open and nonjudgmental frame of mind,” she said. “Just have a conversation.”

Discussing the formulation and concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) in products matters as well.

Will the product be inhaled, ingested, or topical? Inhaled cannabis is not ideal but is sometimes what patients have access to, Worster explained. Inhaled formulations tend to have faster onset, which might be preferable for treating chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, whereas edible formulations may take a while to start working.

It’s also important to warn patients about taking too much, she said, explaining that inhaling THC at higher doses can increase the risk for cardiovascular effects, anxiety, paranoia, panic, and psychosis.

CBD, on the other hand, is anti-inflammatory, but early data suggest it may blunt immune responses in high doses and should be used cautiously by patients receiving immunotherapy.

Worster noted that as laws change and the science advances, new cannabis products and formulations will emerge, as will artificial intelligence tools for helping to guide patients and clinicians in optimal use of cannabis for cancer care. State websites are a particularly helpful tool for providing state-specific medical education related to cannabis laws and use, as well, she said.

The bottom line, she said, is that talking to patients about the ins and outs of cannabis use “really matters.”

Worster disclosed that she is a medical consultant for EO Care.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

first, and oncologists may be hesitant to broach the topic with their patients.

Updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) on the use of cannabis and cannabinoids in adults with cancer stress that it’s an important conversation to have.

According to the ASCO expert panel, access to and use of cannabis alongside cancer care have outpaced the science on evidence-based indications, and overall high-quality data on the effects of cannabis during cancer care are lacking. While several observational studies support cannabis use to help ease chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, the literature remains more divided on other potential benefits, such as alleviating cancer pain and sleep problems, and some evidence points to potential downsides of cannabis use.

Oncologists should “absolutely talk to patients” about cannabis, Brooke Worster, MD, medical director for the Master of Science in Medical Cannabis Science & Business program at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, told Medscape Medical News.

“Patients are interested, and they are going to find access to information. As a medical professional, it’s our job to help guide them through these spaces in a safe, nonjudgmental way.”

But, Worster noted, oncologists don’t have to be experts on cannabis to begin the conversation with patients.

So, “let yourself off the hook,” Worster urged.

Plus, avoiding the conversation won’t stop patients from using cannabis. In a recent study, Worster and her colleagues found that nearly one third of patients at 12 National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers had used cannabis since their diagnosis — most often for sleep disturbance, pain, stress, and anxiety. Most (60%) felt somewhat or extremely comfortable talking to their healthcare provider about it, but only 21.5% said they had done so. Even fewer — about 10% — had talked to their treating oncologist.

Because patients may not discuss cannabis use, it’s especially important for oncologists to open up a line of communication, said Worster, also the enterprise director of supportive oncology at the Thomas Jefferson University.

Evidence on Cannabis During Cancer Care

A substantial proportion of people with cancer believe cannabis can help manage cancer-related symptoms.

In Worster’s recent survey study, regardless of whether patients had used cannabis, almost 90% of those surveyed reported a perceived benefit. Although 65% also reported perceived risks for cannabis use, including difficulty concentrating, lung damage, and impaired memory, the perceived benefits outweighed the risks.

Despite generally positive perceptions, the overall literature on the benefits of cannabis in patients with cancer paints a less clear picture.

The ASCO guidelines, which were based on 13 systematic reviews and five additional primary studies, reported that cannabis can improve refractory, chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting when added to guideline-concordant antiemetic regimens, but that there is no clear evidence of benefit or harm for other supportive care outcomes.

The “certainty of evidence for most outcomes was low or very low,” the ASCO authors wrote.

The ASCO experts explained that, outside the context of a clinical trial, the evidence is not sufficient to recommend cannabis or cannabinoids for managing cancer pain, sleep issues, appetite loss, or anxiety and depression. For these outcomes, some studies indicate a benefit, while others don’t.

Real-world data from a large registry study, for instance, have indicated that medical cannabis is “a safe and effective complementary treatment for pain relief in patients with cancer.” However, a 2020 meta-analysis found that, in studies with a low risk for bias, adding cannabinoids to opioids did not reduce cancer pain in adults with advanced cancer.

There can be downsides to cannabis use, too. In one recent study, some patients reported feeling worse physically and psychologically compared with those who didn’t use cannabis. Another study found that oral cannabis was associated with “bothersome” side effects, including sedation, dizziness, and transient anxiety.

The ASCO guidelines also made it clear that cannabis or cannabinoids should not be used as cancer-directed treatment, outside of a clinical trial.

Talking to Patients About Cannabis

Given the level of evidence and patient interest in cannabis, it is important for oncologists to raise the topic of cannabis use with their patients.

To help inform decision-making and approaches to care, the ASCO guidelines suggest that oncologists can guide care themselves or direct patients to appropriate “unbiased, evidence-based” resources. For those who use cannabis or cannabinoids outside of evidence-based indications or clinician recommendations, it’s important to explore patients’ goals, educate them, and try to minimize harm.

One strategy for broaching the topic, Worster suggested, is to simply ask patients if they have tried or considered trying cannabis to control symptoms like nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, or cancer pain.

The conversation with patients should then include an overview of the potential benefits and potential risks for cannabis use as well as risk reduction strategies, Worster noted.

But “approach it in an open and nonjudgmental frame of mind,” she said. “Just have a conversation.”

Discussing the formulation and concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) in products matters as well.

Will the product be inhaled, ingested, or topical? Inhaled cannabis is not ideal but is sometimes what patients have access to, Worster explained. Inhaled formulations tend to have faster onset, which might be preferable for treating chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, whereas edible formulations may take a while to start working.

It’s also important to warn patients about taking too much, she said, explaining that inhaling THC at higher doses can increase the risk for cardiovascular effects, anxiety, paranoia, panic, and psychosis.

CBD, on the other hand, is anti-inflammatory, but early data suggest it may blunt immune responses in high doses and should be used cautiously by patients receiving immunotherapy.

Worster noted that as laws change and the science advances, new cannabis products and formulations will emerge, as will artificial intelligence tools for helping to guide patients and clinicians in optimal use of cannabis for cancer care. State websites are a particularly helpful tool for providing state-specific medical education related to cannabis laws and use, as well, she said.

The bottom line, she said, is that talking to patients about the ins and outs of cannabis use “really matters.”

Worster disclosed that she is a medical consultant for EO Care.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

first, and oncologists may be hesitant to broach the topic with their patients.

Updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) on the use of cannabis and cannabinoids in adults with cancer stress that it’s an important conversation to have.

According to the ASCO expert panel, access to and use of cannabis alongside cancer care have outpaced the science on evidence-based indications, and overall high-quality data on the effects of cannabis during cancer care are lacking. While several observational studies support cannabis use to help ease chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, the literature remains more divided on other potential benefits, such as alleviating cancer pain and sleep problems, and some evidence points to potential downsides of cannabis use.

Oncologists should “absolutely talk to patients” about cannabis, Brooke Worster, MD, medical director for the Master of Science in Medical Cannabis Science & Business program at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, told Medscape Medical News.

“Patients are interested, and they are going to find access to information. As a medical professional, it’s our job to help guide them through these spaces in a safe, nonjudgmental way.”

But, Worster noted, oncologists don’t have to be experts on cannabis to begin the conversation with patients.

So, “let yourself off the hook,” Worster urged.

Plus, avoiding the conversation won’t stop patients from using cannabis. In a recent study, Worster and her colleagues found that nearly one third of patients at 12 National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers had used cannabis since their diagnosis — most often for sleep disturbance, pain, stress, and anxiety. Most (60%) felt somewhat or extremely comfortable talking to their healthcare provider about it, but only 21.5% said they had done so. Even fewer — about 10% — had talked to their treating oncologist.

Because patients may not discuss cannabis use, it’s especially important for oncologists to open up a line of communication, said Worster, also the enterprise director of supportive oncology at the Thomas Jefferson University.

Evidence on Cannabis During Cancer Care

A substantial proportion of people with cancer believe cannabis can help manage cancer-related symptoms.

In Worster’s recent survey study, regardless of whether patients had used cannabis, almost 90% of those surveyed reported a perceived benefit. Although 65% also reported perceived risks for cannabis use, including difficulty concentrating, lung damage, and impaired memory, the perceived benefits outweighed the risks.

Despite generally positive perceptions, the overall literature on the benefits of cannabis in patients with cancer paints a less clear picture.

The ASCO guidelines, which were based on 13 systematic reviews and five additional primary studies, reported that cannabis can improve refractory, chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting when added to guideline-concordant antiemetic regimens, but that there is no clear evidence of benefit or harm for other supportive care outcomes.

The “certainty of evidence for most outcomes was low or very low,” the ASCO authors wrote.

The ASCO experts explained that, outside the context of a clinical trial, the evidence is not sufficient to recommend cannabis or cannabinoids for managing cancer pain, sleep issues, appetite loss, or anxiety and depression. For these outcomes, some studies indicate a benefit, while others don’t.

Real-world data from a large registry study, for instance, have indicated that medical cannabis is “a safe and effective complementary treatment for pain relief in patients with cancer.” However, a 2020 meta-analysis found that, in studies with a low risk for bias, adding cannabinoids to opioids did not reduce cancer pain in adults with advanced cancer.

There can be downsides to cannabis use, too. In one recent study, some patients reported feeling worse physically and psychologically compared with those who didn’t use cannabis. Another study found that oral cannabis was associated with “bothersome” side effects, including sedation, dizziness, and transient anxiety.

The ASCO guidelines also made it clear that cannabis or cannabinoids should not be used as cancer-directed treatment, outside of a clinical trial.

Talking to Patients About Cannabis

Given the level of evidence and patient interest in cannabis, it is important for oncologists to raise the topic of cannabis use with their patients.

To help inform decision-making and approaches to care, the ASCO guidelines suggest that oncologists can guide care themselves or direct patients to appropriate “unbiased, evidence-based” resources. For those who use cannabis or cannabinoids outside of evidence-based indications or clinician recommendations, it’s important to explore patients’ goals, educate them, and try to minimize harm.

One strategy for broaching the topic, Worster suggested, is to simply ask patients if they have tried or considered trying cannabis to control symptoms like nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, or cancer pain.

The conversation with patients should then include an overview of the potential benefits and potential risks for cannabis use as well as risk reduction strategies, Worster noted.

But “approach it in an open and nonjudgmental frame of mind,” she said. “Just have a conversation.”

Discussing the formulation and concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) in products matters as well.

Will the product be inhaled, ingested, or topical? Inhaled cannabis is not ideal but is sometimes what patients have access to, Worster explained. Inhaled formulations tend to have faster onset, which might be preferable for treating chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, whereas edible formulations may take a while to start working.

It’s also important to warn patients about taking too much, she said, explaining that inhaling THC at higher doses can increase the risk for cardiovascular effects, anxiety, paranoia, panic, and psychosis.

CBD, on the other hand, is anti-inflammatory, but early data suggest it may blunt immune responses in high doses and should be used cautiously by patients receiving immunotherapy.

Worster noted that as laws change and the science advances, new cannabis products and formulations will emerge, as will artificial intelligence tools for helping to guide patients and clinicians in optimal use of cannabis for cancer care. State websites are a particularly helpful tool for providing state-specific medical education related to cannabis laws and use, as well, she said.

The bottom line, she said, is that talking to patients about the ins and outs of cannabis use “really matters.”

Worster disclosed that she is a medical consultant for EO Care.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Small Bowel Dysmotility Brings Challenges to Patients With Systemic Sclerosis

TOPLINE:

Patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) who exhibit abnormal small bowel transit are more likely to be men, experience more severe cardiac involvement, have a higher mortality risk, and show fewer sicca symptoms.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers enrolled 130 patients with SSc having gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (mean age at symptom onset, 56.8 years; 90% women; 81% White) seen at the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center, Baltimore, from October 2014 to May 2022.

- Clinical data and serum samples were longitudinally collected from all actively followed patients at the time of enrollment and every 6 months thereafter (median disease duration, 8.4 years).

- Participants underwent whole gut transit scintigraphy for the assessment of small bowel motility.

- A cross-sectional analysis compared the clinical features of patients with (n = 22; mean age at symptom onset, 61.4 years) and without (n = 108; mean age at symptom onset, 55.8 years) abnormal small bowel transit.

TAKEAWAY:

- Men with SSc (odds ratio [OR], 3.70; P = .038) and those with severe cardiac involvement (OR, 3.98; P = .035) were more likely to have abnormal small bowel transit.

- Sicca symptoms were negatively associated with abnormal small bowel transit in patients with SSc (adjusted OR, 0.28; P = .043).

- Patients with abnormal small bowel transit reported significantly worse (P = .028) and social functioning (P = .015) than those having a normal transit.

- A multivariate analysis showed that patients with abnormal small bowel transit had higher mortality than those with a normal transit (adjusted hazard ratio, 5.03; P = .005).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings improve our understanding of risk factors associated with abnormal small bowel transit in SSc patients and shed light on the lived experience of patients with this GI [gastrointestinal] complication,” the authors wrote. “Overall, these findings are important for patient risk stratification and monitoring and will help to identify a more homogeneous group of patients for future clinical and translational studies,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jenice X. Cheah, MD, University of California, Los Angeles. It was published online on October 7, 2024, in Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study may be subject to referral bias as it was conducted at a tertiary referral center, potentially including patients with a more severe disease status. Furthermore, this study was retrospective in nature, and whole gut transit studies were not conducted in all the patients seen at the referral center. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limited the ability to establish causality between the clinical features and abnormal small bowel transit.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) who exhibit abnormal small bowel transit are more likely to be men, experience more severe cardiac involvement, have a higher mortality risk, and show fewer sicca symptoms.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers enrolled 130 patients with SSc having gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (mean age at symptom onset, 56.8 years; 90% women; 81% White) seen at the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center, Baltimore, from October 2014 to May 2022.

- Clinical data and serum samples were longitudinally collected from all actively followed patients at the time of enrollment and every 6 months thereafter (median disease duration, 8.4 years).

- Participants underwent whole gut transit scintigraphy for the assessment of small bowel motility.

- A cross-sectional analysis compared the clinical features of patients with (n = 22; mean age at symptom onset, 61.4 years) and without (n = 108; mean age at symptom onset, 55.8 years) abnormal small bowel transit.

TAKEAWAY:

- Men with SSc (odds ratio [OR], 3.70; P = .038) and those with severe cardiac involvement (OR, 3.98; P = .035) were more likely to have abnormal small bowel transit.

- Sicca symptoms were negatively associated with abnormal small bowel transit in patients with SSc (adjusted OR, 0.28; P = .043).

- Patients with abnormal small bowel transit reported significantly worse (P = .028) and social functioning (P = .015) than those having a normal transit.

- A multivariate analysis showed that patients with abnormal small bowel transit had higher mortality than those with a normal transit (adjusted hazard ratio, 5.03; P = .005).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings improve our understanding of risk factors associated with abnormal small bowel transit in SSc patients and shed light on the lived experience of patients with this GI [gastrointestinal] complication,” the authors wrote. “Overall, these findings are important for patient risk stratification and monitoring and will help to identify a more homogeneous group of patients for future clinical and translational studies,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jenice X. Cheah, MD, University of California, Los Angeles. It was published online on October 7, 2024, in Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study may be subject to referral bias as it was conducted at a tertiary referral center, potentially including patients with a more severe disease status. Furthermore, this study was retrospective in nature, and whole gut transit studies were not conducted in all the patients seen at the referral center. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limited the ability to establish causality between the clinical features and abnormal small bowel transit.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) who exhibit abnormal small bowel transit are more likely to be men, experience more severe cardiac involvement, have a higher mortality risk, and show fewer sicca symptoms.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers enrolled 130 patients with SSc having gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (mean age at symptom onset, 56.8 years; 90% women; 81% White) seen at the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center, Baltimore, from October 2014 to May 2022.

- Clinical data and serum samples were longitudinally collected from all actively followed patients at the time of enrollment and every 6 months thereafter (median disease duration, 8.4 years).

- Participants underwent whole gut transit scintigraphy for the assessment of small bowel motility.

- A cross-sectional analysis compared the clinical features of patients with (n = 22; mean age at symptom onset, 61.4 years) and without (n = 108; mean age at symptom onset, 55.8 years) abnormal small bowel transit.

TAKEAWAY:

- Men with SSc (odds ratio [OR], 3.70; P = .038) and those with severe cardiac involvement (OR, 3.98; P = .035) were more likely to have abnormal small bowel transit.

- Sicca symptoms were negatively associated with abnormal small bowel transit in patients with SSc (adjusted OR, 0.28; P = .043).

- Patients with abnormal small bowel transit reported significantly worse (P = .028) and social functioning (P = .015) than those having a normal transit.

- A multivariate analysis showed that patients with abnormal small bowel transit had higher mortality than those with a normal transit (adjusted hazard ratio, 5.03; P = .005).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings improve our understanding of risk factors associated with abnormal small bowel transit in SSc patients and shed light on the lived experience of patients with this GI [gastrointestinal] complication,” the authors wrote. “Overall, these findings are important for patient risk stratification and monitoring and will help to identify a more homogeneous group of patients for future clinical and translational studies,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jenice X. Cheah, MD, University of California, Los Angeles. It was published online on October 7, 2024, in Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study may be subject to referral bias as it was conducted at a tertiary referral center, potentially including patients with a more severe disease status. Furthermore, this study was retrospective in nature, and whole gut transit studies were not conducted in all the patients seen at the referral center. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limited the ability to establish causality between the clinical features and abnormal small bowel transit.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Beware the Manchineel: A Case of Irritant Contact Dermatitis

What is the world’s most dangerous tree? According to Guinness World Records1 (and one unlucky contestant on the wilderness survival reality show Naked and Afraid,2 who got its sap in his eyes and needed to be evacuated for treatment), the manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) has earned this designation.1-3 Manchineel trees are part of the strand vegetation of islands in the West Indies and along the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, where their copious root systems help reduce coastal erosion. In the United States, this poisonous tree grows along the southern edge of Florida’s Everglades National Park; the Florida Keys; and the US Virgin Islands, especially Virgin Islands National Park. Although the manchineel tree appears on several endangered species lists,4-6 there are places within its distribution where it is locally abundant and thus poses a risk to residents and visitors.

The first European description of manchineel toxicity was by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, a court historian and geographer of Christopher Columbus’s patroness, Isabella I, Queen of Castile and Léon. In the early 1500s, Peter Martyr wrote that on Columbus’s second New World voyage in 1493, the crew encountered a mysterious tree that burned the skin and eyes of anyone who had contact with it.7 Columbus called the tree’s fruit manzanilla de la muerte (“little apple of death”) after several sailors became severely ill from eating the fruit.8,9 Manchineel lore is rife with tales of agonizing death after eating the applelike fruit, and several contemporaneous accounts describe indigenous Caribbean islanders using manchineel’s toxic sap as an arrow poison.10

Eating manchineel fruit is known to cause abdominal pain, burning sensations in the oropharynx, and esophageal spasms.11 Several case reports mention that consuming the fruit can create an exaggerated

Case Report

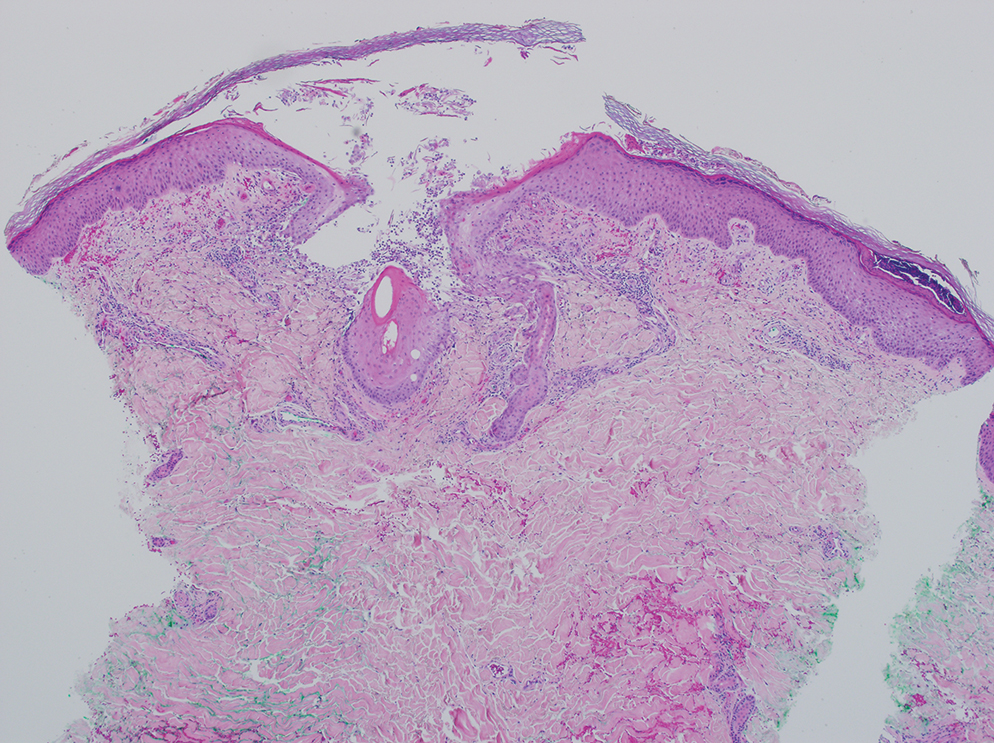

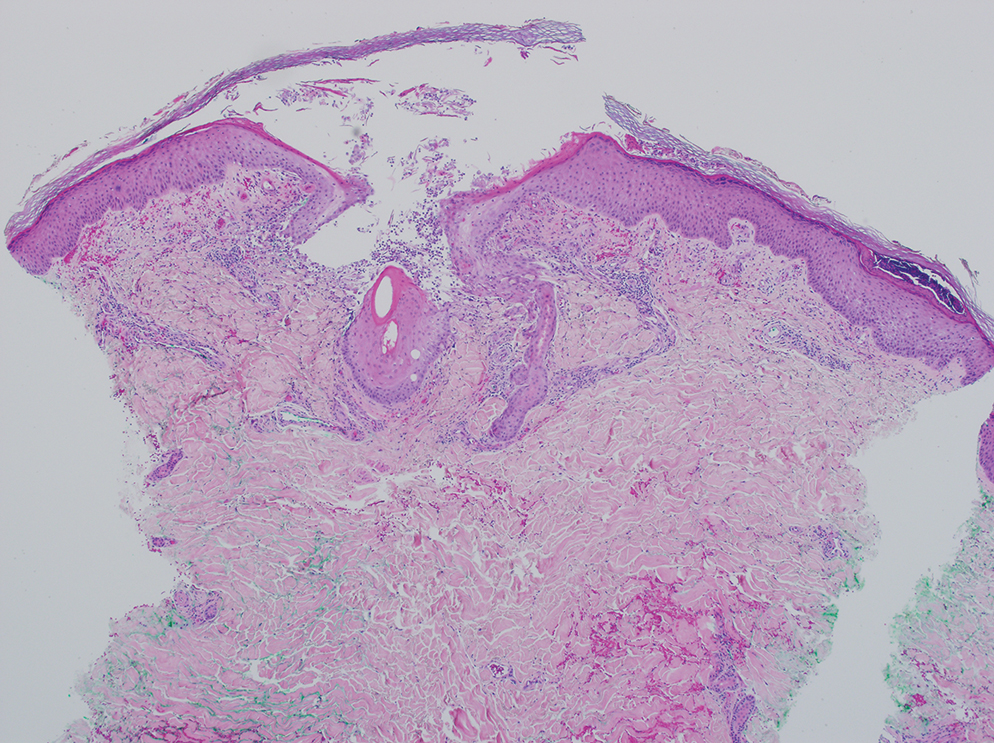

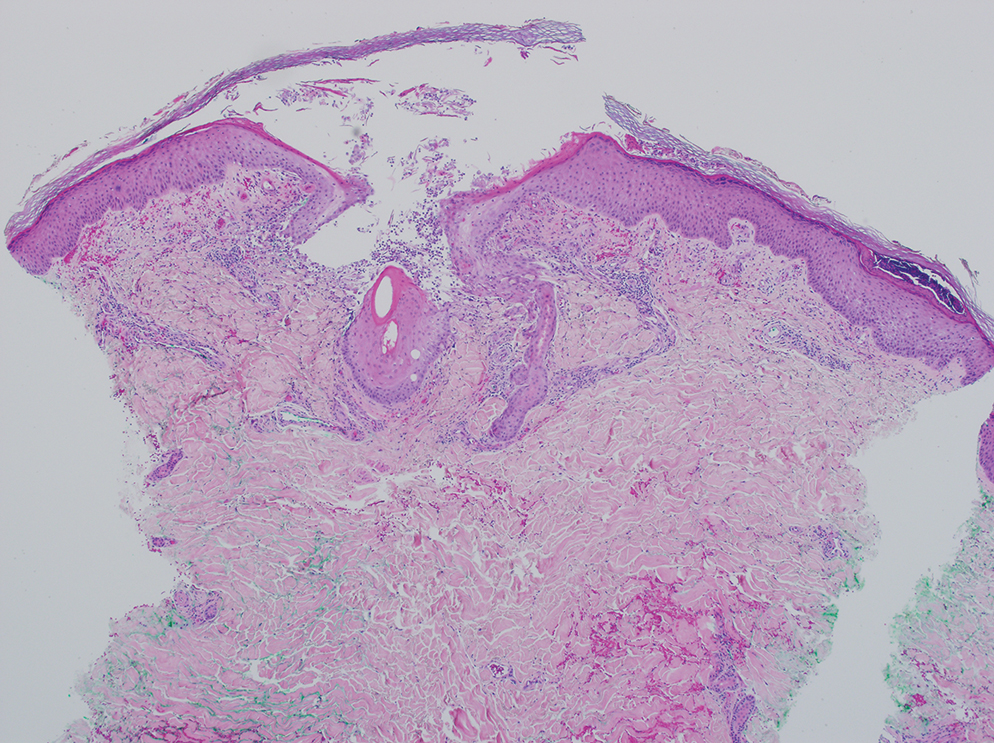

A 64-year-old physician (S.A.N.) came across a stand of manchineel trees while camping in the Virgin Islands National Park on St. John in the US Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The patient—who was knowledgeable about tropical ecology and was familiar with the tree—was curious about its purported cutaneous toxicity and applied the viscous white sap of a broken branchlet (Figure 2) to a patch of skin measuring 4 cm in diameter on the medial left calf. He took serial photographs of the site on days 2, 4 (Figure 3), 6, and 10 (Figure 4), showing the onset of erythema and the subsequent development of follicular pustules. On day 6, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen was taken of the most prominent pustule. Histopathology showed a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which was consistent with irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 5). On day 8, the region became indurated and tender to pressure; however, there was no warmth, edema, purulent drainage, lymphangitic streaks, or other signs of infection. The region was never itchy; it was uncomfortable only with firm direct pressure. The patient applied hot compresses to the site for 10 minutes 1 to 2 times daily for roughly 2 weeks, and the affected area healed fully (without any additional intervention) in approximately 6 weeks.

Comment

Manchineel is a member of the Euphorbiaceae (also known as the euphorb or spurge) family, a mainly tropical or subtropical plant family that includes many useful as well as many toxic species. Examples of useful plants include cassava (Manihot esculenta) and the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Many euphorbs have well-described toxicities, and many (eg, castor bean, Ricinus communis) are useful in some circumstances and toxic in others.6,12-14 Many euphorbs are known to cause skin reactions, usually due to toxins in the milky sap that directly irritate the skin or to latex compounds that can induce IgE-mediated contact dermatitis.9,14

Manchineel contains a complex mix of toxins, though no specific one has been identified as the main cause of the associated irritant contact dermatitis. Manchineel sap (and sap of many other euphorbs) contains phorbol esters that may cause direct pH-induced cytotoxicity leading to keratinocyte necrosis. Diterpenes may augment this cytotoxic effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines.12 Pitts et al5 pointed to a mixture of oxygenated diterpene esters as the primary cause of toxicity and suggested that their water solubility explained occurrences of keratoconjunctivitis after contact with rainwater or dew from the manchineel tree.

All parts of the manchineel tree—fruit, leaves, wood, and sap—are poisonous. In a retrospective series of 97 cases of manchineel fruit ingestion, the most common symptoms were oropharyngeal pain (68% [66/97]), abdominal pain (42% [41/97]), and diarrhea (37% [36/97]). The same series identified 1 (1%) case of bradycardia and hypotension.3 Contact with the wood, exposure to sawdust, and inhalation of smoke from burning the wood can irritate the skin, conjunctivae, or nasopharynx. Rainwater or dew dripping from the leaves onto the skin can cause dermatitis and ophthalmitis, even without direct contact with the tree.4,5

Management—There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Because it is an irritant reaction and not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, topical corticosteroids have minimal benefit. A regimen consisting of a thorough cleansing, wet compresses, and observation, as most symptoms resolve spontaneously within a few days, has been recommended.4 Our patient used hot compresses, which he believes helped heal the site, although his symptoms lasted for several weeks.

Given that there is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis, the wisest approach is strict avoidance. On many Caribbean islands, visitors are warned about the manchineel tree, advised to avoid direct contact, and reminded to avoid standing beneath it during a rainstorm (Figure 6).

Conclusion

This article begins with a question: “What is the world’s most dangerous tree?” Many sources from the indexed medical literature as well as the popular press and social media state that it is the manchineel. Although all parts of the manchineel tree are highly toxic, human exposures are uncommon, and deaths are more apocryphal than actual.

- Most dangerous tree. Guinness World Records. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-dangerous-tree

- Naked and Afraid: Garden of Evil (S4E9). Discovery Channel. June 21, 2015. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://go.discovery.com/video/naked-and-afraid-discovery/garden-of-evil

- Boucaud-Maitre D, Cachet X, Bouzidi C, et al. Severity of manchineel fruit (Hippomane mancinella) poisoning: a retrospective case series of 97 patients from French Poison Control Centers. Toxicon. 2019;161:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.014

- Blue LM, Sailing C, Denapoles C, et al. Manchineel dermatitis in North American students in the Caribbean. J Travel Medicine. 2011;18:422-424. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00568.x

- Pitts JF, Barker NH, Gibbons DC, et al. Manchineel keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:284-288. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.5.284

- Lauter WM, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella, L. I. historical review. J Pharm Sci. 1952;41:199-201. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3030410412

- Martyr P. De Orbe Novo: the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. Vol 1. FA MacNutt (translator). GP Putnam’s Sons; 1912. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12425/pg12425.txt

- Fernandez de Ybarra AM. A forgotten medical worthy, Dr. Diego Alvarex Chanca, of Seville, Spain, and his letter describing the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. Med Library Hist J. 1906;4:246-263.

- Muscat MK. Manchineel apple of death. EJIFCC. 2019;30:346-348.

- Handler JS. Aspects of Amerindian ethnography in 17th century Barbados. Caribbean Studies. 1970;9:50-72.

- Howard RA. Three experiences with the manchineel (Hippomane spp., Euphorbiaceae). Biotropica. 1981;13:224-227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388129

- Rao KV. Toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella. Planta Med. 1974;25:166-171. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097927

- Lauter WM, Foote PA. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. II. Preliminary isolation of a toxic principle of the fruit. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1955;44:361-363. doi:10.1002/jps.3030440616

- Carroll MN Jr, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. III. Toxic actions of extracts of Hippomane mancinella L. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:93-97. doi:10.1002/jps.3030460206

What is the world’s most dangerous tree? According to Guinness World Records1 (and one unlucky contestant on the wilderness survival reality show Naked and Afraid,2 who got its sap in his eyes and needed to be evacuated for treatment), the manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) has earned this designation.1-3 Manchineel trees are part of the strand vegetation of islands in the West Indies and along the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, where their copious root systems help reduce coastal erosion. In the United States, this poisonous tree grows along the southern edge of Florida’s Everglades National Park; the Florida Keys; and the US Virgin Islands, especially Virgin Islands National Park. Although the manchineel tree appears on several endangered species lists,4-6 there are places within its distribution where it is locally abundant and thus poses a risk to residents and visitors.

The first European description of manchineel toxicity was by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, a court historian and geographer of Christopher Columbus’s patroness, Isabella I, Queen of Castile and Léon. In the early 1500s, Peter Martyr wrote that on Columbus’s second New World voyage in 1493, the crew encountered a mysterious tree that burned the skin and eyes of anyone who had contact with it.7 Columbus called the tree’s fruit manzanilla de la muerte (“little apple of death”) after several sailors became severely ill from eating the fruit.8,9 Manchineel lore is rife with tales of agonizing death after eating the applelike fruit, and several contemporaneous accounts describe indigenous Caribbean islanders using manchineel’s toxic sap as an arrow poison.10

Eating manchineel fruit is known to cause abdominal pain, burning sensations in the oropharynx, and esophageal spasms.11 Several case reports mention that consuming the fruit can create an exaggerated

Case Report

A 64-year-old physician (S.A.N.) came across a stand of manchineel trees while camping in the Virgin Islands National Park on St. John in the US Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The patient—who was knowledgeable about tropical ecology and was familiar with the tree—was curious about its purported cutaneous toxicity and applied the viscous white sap of a broken branchlet (Figure 2) to a patch of skin measuring 4 cm in diameter on the medial left calf. He took serial photographs of the site on days 2, 4 (Figure 3), 6, and 10 (Figure 4), showing the onset of erythema and the subsequent development of follicular pustules. On day 6, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen was taken of the most prominent pustule. Histopathology showed a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which was consistent with irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 5). On day 8, the region became indurated and tender to pressure; however, there was no warmth, edema, purulent drainage, lymphangitic streaks, or other signs of infection. The region was never itchy; it was uncomfortable only with firm direct pressure. The patient applied hot compresses to the site for 10 minutes 1 to 2 times daily for roughly 2 weeks, and the affected area healed fully (without any additional intervention) in approximately 6 weeks.

Comment

Manchineel is a member of the Euphorbiaceae (also known as the euphorb or spurge) family, a mainly tropical or subtropical plant family that includes many useful as well as many toxic species. Examples of useful plants include cassava (Manihot esculenta) and the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Many euphorbs have well-described toxicities, and many (eg, castor bean, Ricinus communis) are useful in some circumstances and toxic in others.6,12-14 Many euphorbs are known to cause skin reactions, usually due to toxins in the milky sap that directly irritate the skin or to latex compounds that can induce IgE-mediated contact dermatitis.9,14

Manchineel contains a complex mix of toxins, though no specific one has been identified as the main cause of the associated irritant contact dermatitis. Manchineel sap (and sap of many other euphorbs) contains phorbol esters that may cause direct pH-induced cytotoxicity leading to keratinocyte necrosis. Diterpenes may augment this cytotoxic effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines.12 Pitts et al5 pointed to a mixture of oxygenated diterpene esters as the primary cause of toxicity and suggested that their water solubility explained occurrences of keratoconjunctivitis after contact with rainwater or dew from the manchineel tree.

All parts of the manchineel tree—fruit, leaves, wood, and sap—are poisonous. In a retrospective series of 97 cases of manchineel fruit ingestion, the most common symptoms were oropharyngeal pain (68% [66/97]), abdominal pain (42% [41/97]), and diarrhea (37% [36/97]). The same series identified 1 (1%) case of bradycardia and hypotension.3 Contact with the wood, exposure to sawdust, and inhalation of smoke from burning the wood can irritate the skin, conjunctivae, or nasopharynx. Rainwater or dew dripping from the leaves onto the skin can cause dermatitis and ophthalmitis, even without direct contact with the tree.4,5

Management—There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Because it is an irritant reaction and not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, topical corticosteroids have minimal benefit. A regimen consisting of a thorough cleansing, wet compresses, and observation, as most symptoms resolve spontaneously within a few days, has been recommended.4 Our patient used hot compresses, which he believes helped heal the site, although his symptoms lasted for several weeks.

Given that there is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis, the wisest approach is strict avoidance. On many Caribbean islands, visitors are warned about the manchineel tree, advised to avoid direct contact, and reminded to avoid standing beneath it during a rainstorm (Figure 6).

Conclusion

This article begins with a question: “What is the world’s most dangerous tree?” Many sources from the indexed medical literature as well as the popular press and social media state that it is the manchineel. Although all parts of the manchineel tree are highly toxic, human exposures are uncommon, and deaths are more apocryphal than actual.

What is the world’s most dangerous tree? According to Guinness World Records1 (and one unlucky contestant on the wilderness survival reality show Naked and Afraid,2 who got its sap in his eyes and needed to be evacuated for treatment), the manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) has earned this designation.1-3 Manchineel trees are part of the strand vegetation of islands in the West Indies and along the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, where their copious root systems help reduce coastal erosion. In the United States, this poisonous tree grows along the southern edge of Florida’s Everglades National Park; the Florida Keys; and the US Virgin Islands, especially Virgin Islands National Park. Although the manchineel tree appears on several endangered species lists,4-6 there are places within its distribution where it is locally abundant and thus poses a risk to residents and visitors.

The first European description of manchineel toxicity was by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, a court historian and geographer of Christopher Columbus’s patroness, Isabella I, Queen of Castile and Léon. In the early 1500s, Peter Martyr wrote that on Columbus’s second New World voyage in 1493, the crew encountered a mysterious tree that burned the skin and eyes of anyone who had contact with it.7 Columbus called the tree’s fruit manzanilla de la muerte (“little apple of death”) after several sailors became severely ill from eating the fruit.8,9 Manchineel lore is rife with tales of agonizing death after eating the applelike fruit, and several contemporaneous accounts describe indigenous Caribbean islanders using manchineel’s toxic sap as an arrow poison.10

Eating manchineel fruit is known to cause abdominal pain, burning sensations in the oropharynx, and esophageal spasms.11 Several case reports mention that consuming the fruit can create an exaggerated

Case Report

A 64-year-old physician (S.A.N.) came across a stand of manchineel trees while camping in the Virgin Islands National Park on St. John in the US Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The patient—who was knowledgeable about tropical ecology and was familiar with the tree—was curious about its purported cutaneous toxicity and applied the viscous white sap of a broken branchlet (Figure 2) to a patch of skin measuring 4 cm in diameter on the medial left calf. He took serial photographs of the site on days 2, 4 (Figure 3), 6, and 10 (Figure 4), showing the onset of erythema and the subsequent development of follicular pustules. On day 6, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen was taken of the most prominent pustule. Histopathology showed a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which was consistent with irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 5). On day 8, the region became indurated and tender to pressure; however, there was no warmth, edema, purulent drainage, lymphangitic streaks, or other signs of infection. The region was never itchy; it was uncomfortable only with firm direct pressure. The patient applied hot compresses to the site for 10 minutes 1 to 2 times daily for roughly 2 weeks, and the affected area healed fully (without any additional intervention) in approximately 6 weeks.

Comment

Manchineel is a member of the Euphorbiaceae (also known as the euphorb or spurge) family, a mainly tropical or subtropical plant family that includes many useful as well as many toxic species. Examples of useful plants include cassava (Manihot esculenta) and the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Many euphorbs have well-described toxicities, and many (eg, castor bean, Ricinus communis) are useful in some circumstances and toxic in others.6,12-14 Many euphorbs are known to cause skin reactions, usually due to toxins in the milky sap that directly irritate the skin or to latex compounds that can induce IgE-mediated contact dermatitis.9,14

Manchineel contains a complex mix of toxins, though no specific one has been identified as the main cause of the associated irritant contact dermatitis. Manchineel sap (and sap of many other euphorbs) contains phorbol esters that may cause direct pH-induced cytotoxicity leading to keratinocyte necrosis. Diterpenes may augment this cytotoxic effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines.12 Pitts et al5 pointed to a mixture of oxygenated diterpene esters as the primary cause of toxicity and suggested that their water solubility explained occurrences of keratoconjunctivitis after contact with rainwater or dew from the manchineel tree.

All parts of the manchineel tree—fruit, leaves, wood, and sap—are poisonous. In a retrospective series of 97 cases of manchineel fruit ingestion, the most common symptoms were oropharyngeal pain (68% [66/97]), abdominal pain (42% [41/97]), and diarrhea (37% [36/97]). The same series identified 1 (1%) case of bradycardia and hypotension.3 Contact with the wood, exposure to sawdust, and inhalation of smoke from burning the wood can irritate the skin, conjunctivae, or nasopharynx. Rainwater or dew dripping from the leaves onto the skin can cause dermatitis and ophthalmitis, even without direct contact with the tree.4,5

Management—There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Because it is an irritant reaction and not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, topical corticosteroids have minimal benefit. A regimen consisting of a thorough cleansing, wet compresses, and observation, as most symptoms resolve spontaneously within a few days, has been recommended.4 Our patient used hot compresses, which he believes helped heal the site, although his symptoms lasted for several weeks.

Given that there is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis, the wisest approach is strict avoidance. On many Caribbean islands, visitors are warned about the manchineel tree, advised to avoid direct contact, and reminded to avoid standing beneath it during a rainstorm (Figure 6).

Conclusion

This article begins with a question: “What is the world’s most dangerous tree?” Many sources from the indexed medical literature as well as the popular press and social media state that it is the manchineel. Although all parts of the manchineel tree are highly toxic, human exposures are uncommon, and deaths are more apocryphal than actual.

- Most dangerous tree. Guinness World Records. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-dangerous-tree

- Naked and Afraid: Garden of Evil (S4E9). Discovery Channel. June 21, 2015. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://go.discovery.com/video/naked-and-afraid-discovery/garden-of-evil

- Boucaud-Maitre D, Cachet X, Bouzidi C, et al. Severity of manchineel fruit (Hippomane mancinella) poisoning: a retrospective case series of 97 patients from French Poison Control Centers. Toxicon. 2019;161:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.014

- Blue LM, Sailing C, Denapoles C, et al. Manchineel dermatitis in North American students in the Caribbean. J Travel Medicine. 2011;18:422-424. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00568.x

- Pitts JF, Barker NH, Gibbons DC, et al. Manchineel keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:284-288. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.5.284

- Lauter WM, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella, L. I. historical review. J Pharm Sci. 1952;41:199-201. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3030410412

- Martyr P. De Orbe Novo: the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. Vol 1. FA MacNutt (translator). GP Putnam’s Sons; 1912. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12425/pg12425.txt

- Fernandez de Ybarra AM. A forgotten medical worthy, Dr. Diego Alvarex Chanca, of Seville, Spain, and his letter describing the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. Med Library Hist J. 1906;4:246-263.

- Muscat MK. Manchineel apple of death. EJIFCC. 2019;30:346-348.

- Handler JS. Aspects of Amerindian ethnography in 17th century Barbados. Caribbean Studies. 1970;9:50-72.

- Howard RA. Three experiences with the manchineel (Hippomane spp., Euphorbiaceae). Biotropica. 1981;13:224-227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388129

- Rao KV. Toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella. Planta Med. 1974;25:166-171. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097927

- Lauter WM, Foote PA. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. II. Preliminary isolation of a toxic principle of the fruit. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1955;44:361-363. doi:10.1002/jps.3030440616

- Carroll MN Jr, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. III. Toxic actions of extracts of Hippomane mancinella L. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:93-97. doi:10.1002/jps.3030460206

- Most dangerous tree. Guinness World Records. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-dangerous-tree

- Naked and Afraid: Garden of Evil (S4E9). Discovery Channel. June 21, 2015. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://go.discovery.com/video/naked-and-afraid-discovery/garden-of-evil

- Boucaud-Maitre D, Cachet X, Bouzidi C, et al. Severity of manchineel fruit (Hippomane mancinella) poisoning: a retrospective case series of 97 patients from French Poison Control Centers. Toxicon. 2019;161:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.014

- Blue LM, Sailing C, Denapoles C, et al. Manchineel dermatitis in North American students in the Caribbean. J Travel Medicine. 2011;18:422-424. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00568.x

- Pitts JF, Barker NH, Gibbons DC, et al. Manchineel keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:284-288. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.5.284

- Lauter WM, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella, L. I. historical review. J Pharm Sci. 1952;41:199-201. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3030410412

- Martyr P. De Orbe Novo: the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. Vol 1. FA MacNutt (translator). GP Putnam’s Sons; 1912. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12425/pg12425.txt

- Fernandez de Ybarra AM. A forgotten medical worthy, Dr. Diego Alvarex Chanca, of Seville, Spain, and his letter describing the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. Med Library Hist J. 1906;4:246-263.

- Muscat MK. Manchineel apple of death. EJIFCC. 2019;30:346-348.

- Handler JS. Aspects of Amerindian ethnography in 17th century Barbados. Caribbean Studies. 1970;9:50-72.

- Howard RA. Three experiences with the manchineel (Hippomane spp., Euphorbiaceae). Biotropica. 1981;13:224-227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388129

- Rao KV. Toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella. Planta Med. 1974;25:166-171. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097927

- Lauter WM, Foote PA. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. II. Preliminary isolation of a toxic principle of the fruit. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1955;44:361-363. doi:10.1002/jps.3030440616

- Carroll MN Jr, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. III. Toxic actions of extracts of Hippomane mancinella L. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:93-97. doi:10.1002/jps.3030460206

PRACTICE POINTS

- Sap from the manchineel tree—found on the coasts of Caribbean islands, the Atlantic coastline of Central and northern South America, and parts of southernmost Florida—can cause severe dermatologic and ophthalmologic injuries. Eating its fruit can lead to oropharyngeal pain and diarrhea.

- Histopathology of manchineel dermatitis reveals a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which is consistent with irritant contact dermatitis.

- There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Case reports advocate a thorough cleansing, application of wet compresses, and observation.

Wrinkles, Dyspigmentation Improve with PDT, in Small Study

.

“Our study helps capture and quantify a phenomenon that clinicians who use PDT in their practice have already noticed: Patients experience a visible improvement across several cosmetically important metrics including but not limited to fine lines, wrinkles, and skin tightness following PDT,” one of the study authors, Luke Horton, MD, a fourth-year dermatology resident at the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session.

For the study, 11 patients underwent a 120-minute incubation period with 17% 5-aminolevulinic acid over the face, followed by visible blue light PDT exposure for 16 minutes, to reduce rhytides. The researchers used a Vectra imaging system to capture three-dimensional images of the patients before the procedure and during the follow-up. Three dermatologists analyzed the pre-procedure and post-procedure images and used a validated five-point Merz wrinkle severity scale to grade various regions of the face including the forehead, glabella, lateral canthal rhytides, melolabial folds, nasolabial folds, and perioral rhytides.

They also used a five-point solar lentigines scale to evaluate the change in degree of pigmentation and quantity of age spots as well as the change in rhytid severity before and after PDT and the change in the seven-point Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) to gauge overall improvement of fine lines and wrinkles.

After a mean follow-up of 4.25 months, rhytid severity among the 11 patients was reduced by an average of 0.65 points on the Merz scale, with an SD of 0.20. Broken down by region, rhytid severity scores decreased by 0.2 points (SD, 0.42) for the forehead, 0.7 points (SD, 0.48) for the glabella and lateral canthal rhytides, 0.88 points (SD, 0.35) for the melolabial folds and perioral rhytides, and 0.8 points (SD, 0.42) for the nasolabial folds. (The researchers excluded ratings for the melolabial folds and perioral rhytides in two patients with beards.)

In other findings, solar lentigines grading showed an average reduction of 1 point (SD, 0.45), while the GAIS score improved by 1 or more for every patient, with an average of score of 1.45 (SD, 0.52), showing that some degree of improvement in facial rhytides was noted for all patients following PDT.

“The degree of improvement as measured by our independent physician graders was impressive and not far off from those reported with CO2 ablative laser,” Horton said. “Further, the effect was not isolated to actinic keratoses but extended to improved appearance of fine lines, some deep lines, and lentigines. Although we are not implying that PDT is superior to and should replace lasers or other energy-based devices, it does provide a real, measurable cosmetic benefit.”

Clinicians, he added, can use these findings “to counsel their patients when discussing field cancerization treatment options, especially for patients who may be hesitant to undergo PDT as it can be a painful therapy with a considerable downtime for some.”

Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, who was asked to comment on the study results, said that the findings “shine more light on the long-standing off-label use of PDT for lessening signs of photoaging. Like studies done before it, I think this adds an additional benefit to discuss for those who are considering PDT treatment for their actinic keratoses.”

Horton acknowledged certain limitations of the study including its small sample size and the fact that physician graders were not blinded to which images were pre- and post-treatment, “which could introduce an element of bias in the data,” he said. “But this being an unfunded project born out of clinical observation, we hope to later expand its size. Furthermore, we invite other physicians to join us to better study these effects and to design protocols that minimize adverse effects and maximize clinical outcomes.”

His co-authors were Milan Hirpara; Sarah Choe; Joel Cohen, MD; and Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD.

No relevant disclosures were reported. Green had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

“Our study helps capture and quantify a phenomenon that clinicians who use PDT in their practice have already noticed: Patients experience a visible improvement across several cosmetically important metrics including but not limited to fine lines, wrinkles, and skin tightness following PDT,” one of the study authors, Luke Horton, MD, a fourth-year dermatology resident at the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session.

For the study, 11 patients underwent a 120-minute incubation period with 17% 5-aminolevulinic acid over the face, followed by visible blue light PDT exposure for 16 minutes, to reduce rhytides. The researchers used a Vectra imaging system to capture three-dimensional images of the patients before the procedure and during the follow-up. Three dermatologists analyzed the pre-procedure and post-procedure images and used a validated five-point Merz wrinkle severity scale to grade various regions of the face including the forehead, glabella, lateral canthal rhytides, melolabial folds, nasolabial folds, and perioral rhytides.

They also used a five-point solar lentigines scale to evaluate the change in degree of pigmentation and quantity of age spots as well as the change in rhytid severity before and after PDT and the change in the seven-point Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) to gauge overall improvement of fine lines and wrinkles.

After a mean follow-up of 4.25 months, rhytid severity among the 11 patients was reduced by an average of 0.65 points on the Merz scale, with an SD of 0.20. Broken down by region, rhytid severity scores decreased by 0.2 points (SD, 0.42) for the forehead, 0.7 points (SD, 0.48) for the glabella and lateral canthal rhytides, 0.88 points (SD, 0.35) for the melolabial folds and perioral rhytides, and 0.8 points (SD, 0.42) for the nasolabial folds. (The researchers excluded ratings for the melolabial folds and perioral rhytides in two patients with beards.)

In other findings, solar lentigines grading showed an average reduction of 1 point (SD, 0.45), while the GAIS score improved by 1 or more for every patient, with an average of score of 1.45 (SD, 0.52), showing that some degree of improvement in facial rhytides was noted for all patients following PDT.

“The degree of improvement as measured by our independent physician graders was impressive and not far off from those reported with CO2 ablative laser,” Horton said. “Further, the effect was not isolated to actinic keratoses but extended to improved appearance of fine lines, some deep lines, and lentigines. Although we are not implying that PDT is superior to and should replace lasers or other energy-based devices, it does provide a real, measurable cosmetic benefit.”

Clinicians, he added, can use these findings “to counsel their patients when discussing field cancerization treatment options, especially for patients who may be hesitant to undergo PDT as it can be a painful therapy with a considerable downtime for some.”

Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, who was asked to comment on the study results, said that the findings “shine more light on the long-standing off-label use of PDT for lessening signs of photoaging. Like studies done before it, I think this adds an additional benefit to discuss for those who are considering PDT treatment for their actinic keratoses.”

Horton acknowledged certain limitations of the study including its small sample size and the fact that physician graders were not blinded to which images were pre- and post-treatment, “which could introduce an element of bias in the data,” he said. “But this being an unfunded project born out of clinical observation, we hope to later expand its size. Furthermore, we invite other physicians to join us to better study these effects and to design protocols that minimize adverse effects and maximize clinical outcomes.”

His co-authors were Milan Hirpara; Sarah Choe; Joel Cohen, MD; and Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD.

No relevant disclosures were reported. Green had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

“Our study helps capture and quantify a phenomenon that clinicians who use PDT in their practice have already noticed: Patients experience a visible improvement across several cosmetically important metrics including but not limited to fine lines, wrinkles, and skin tightness following PDT,” one of the study authors, Luke Horton, MD, a fourth-year dermatology resident at the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session.

For the study, 11 patients underwent a 120-minute incubation period with 17% 5-aminolevulinic acid over the face, followed by visible blue light PDT exposure for 16 minutes, to reduce rhytides. The researchers used a Vectra imaging system to capture three-dimensional images of the patients before the procedure and during the follow-up. Three dermatologists analyzed the pre-procedure and post-procedure images and used a validated five-point Merz wrinkle severity scale to grade various regions of the face including the forehead, glabella, lateral canthal rhytides, melolabial folds, nasolabial folds, and perioral rhytides.

They also used a five-point solar lentigines scale to evaluate the change in degree of pigmentation and quantity of age spots as well as the change in rhytid severity before and after PDT and the change in the seven-point Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) to gauge overall improvement of fine lines and wrinkles.

After a mean follow-up of 4.25 months, rhytid severity among the 11 patients was reduced by an average of 0.65 points on the Merz scale, with an SD of 0.20. Broken down by region, rhytid severity scores decreased by 0.2 points (SD, 0.42) for the forehead, 0.7 points (SD, 0.48) for the glabella and lateral canthal rhytides, 0.88 points (SD, 0.35) for the melolabial folds and perioral rhytides, and 0.8 points (SD, 0.42) for the nasolabial folds. (The researchers excluded ratings for the melolabial folds and perioral rhytides in two patients with beards.)

In other findings, solar lentigines grading showed an average reduction of 1 point (SD, 0.45), while the GAIS score improved by 1 or more for every patient, with an average of score of 1.45 (SD, 0.52), showing that some degree of improvement in facial rhytides was noted for all patients following PDT.

“The degree of improvement as measured by our independent physician graders was impressive and not far off from those reported with CO2 ablative laser,” Horton said. “Further, the effect was not isolated to actinic keratoses but extended to improved appearance of fine lines, some deep lines, and lentigines. Although we are not implying that PDT is superior to and should replace lasers or other energy-based devices, it does provide a real, measurable cosmetic benefit.”

Clinicians, he added, can use these findings “to counsel their patients when discussing field cancerization treatment options, especially for patients who may be hesitant to undergo PDT as it can be a painful therapy with a considerable downtime for some.”

Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, who was asked to comment on the study results, said that the findings “shine more light on the long-standing off-label use of PDT for lessening signs of photoaging. Like studies done before it, I think this adds an additional benefit to discuss for those who are considering PDT treatment for their actinic keratoses.”

Horton acknowledged certain limitations of the study including its small sample size and the fact that physician graders were not blinded to which images were pre- and post-treatment, “which could introduce an element of bias in the data,” he said. “But this being an unfunded project born out of clinical observation, we hope to later expand its size. Furthermore, we invite other physicians to join us to better study these effects and to design protocols that minimize adverse effects and maximize clinical outcomes.”

His co-authors were Milan Hirpara; Sarah Choe; Joel Cohen, MD; and Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD.

No relevant disclosures were reported. Green had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Responses Sustained with Ritlecitinib in Patients with Alopecia Through 48 Weeks

TOPLINE:

, and up to one third of nonresponders at week 24 also achieved responses by week 48.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 trial (ALLEGRO) and included 718 adults and adolescents aged 12 or older with severe AA (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score ≥ 50).

- Patients received various doses of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor ritlecitinib, with or without a 4-week loading dose, including 200/50 mg, 200/30 mg, 50 mg, or 30 mg, with or without a 4-week loading dose for up to 24 weeks and continued to receive their assigned maintenance dose.

- Researchers assessed sustained clinical responses at week 48 for those who had achieved SALT scores ≤ 20 and ≤ 10 at 24 weeks, and nonresponders at week 24 were assessed for responses through week 48.

- Adverse events were also evaluated.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among patients on ritlecitinib who had responded at week 24, SALT responses ≤ 20 were sustained in 85.2%-100% of patients through week 48. Similar results were seen among patients who achieved a SALT score ≤ 10 (68.8%-91.7%) and improvements in eyebrow (70.4%-96.9%) or eyelash (52.4%-94.1%) assessment scores.

- Among those who were nonresponders at week 24, 22.2%-33.7% achieved a SALT score ≤ 20 and 19.8%-25.5% achieved a SALT score ≤ 10 by week 48. Similarly, among those with no eyebrow or eyelash responses at week 24, 19.7%-32.8% and 16.7%-30.2% had improved eyebrow or eyelash assessment scores, respectively, at week 48.

- Between weeks 24 and 48, adverse events were reported in 74%-93% of patients who achieved a SALT score ≤ 20, most were mild or moderate; two serious events were reported but deemed unrelated to treatment. The safety profile was similar across all subgroups.

- No deaths, malignancies, major cardiovascular events, opportunistic infections, or herpes zoster infections were observed.

IN PRACTICE:

“The majority of ritlecitinib-treated patients with AA who met target clinical response based on scalp, eyebrow, or eyelash regrowth at week 24 sustained their response through week 48 with continued treatment,” the authors wrote. “Some patients, including those with more extensive hair loss, may require ritlecitinib treatment beyond 6 months to achieve target clinical response,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melissa Piliang, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Cleveland Clinic, and was published online on October 17 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited by its post hoc nature, small sample size in each treatment group, and a follow-up period of only 48 weeks.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Pfizer. Piliang disclosed being a consultant or investigator for Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Procter & Gamble. Six authors were employees or shareholders of or received salary from Pfizer. Other authors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies outside this work, including Pfizer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, and up to one third of nonresponders at week 24 also achieved responses by week 48.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 trial (ALLEGRO) and included 718 adults and adolescents aged 12 or older with severe AA (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score ≥ 50).

- Patients received various doses of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor ritlecitinib, with or without a 4-week loading dose, including 200/50 mg, 200/30 mg, 50 mg, or 30 mg, with or without a 4-week loading dose for up to 24 weeks and continued to receive their assigned maintenance dose.

- Researchers assessed sustained clinical responses at week 48 for those who had achieved SALT scores ≤ 20 and ≤ 10 at 24 weeks, and nonresponders at week 24 were assessed for responses through week 48.

- Adverse events were also evaluated.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among patients on ritlecitinib who had responded at week 24, SALT responses ≤ 20 were sustained in 85.2%-100% of patients through week 48. Similar results were seen among patients who achieved a SALT score ≤ 10 (68.8%-91.7%) and improvements in eyebrow (70.4%-96.9%) or eyelash (52.4%-94.1%) assessment scores.

- Among those who were nonresponders at week 24, 22.2%-33.7% achieved a SALT score ≤ 20 and 19.8%-25.5% achieved a SALT score ≤ 10 by week 48. Similarly, among those with no eyebrow or eyelash responses at week 24, 19.7%-32.8% and 16.7%-30.2% had improved eyebrow or eyelash assessment scores, respectively, at week 48.

- Between weeks 24 and 48, adverse events were reported in 74%-93% of patients who achieved a SALT score ≤ 20, most were mild or moderate; two serious events were reported but deemed unrelated to treatment. The safety profile was similar across all subgroups.

- No deaths, malignancies, major cardiovascular events, opportunistic infections, or herpes zoster infections were observed.

IN PRACTICE:

“The majority of ritlecitinib-treated patients with AA who met target clinical response based on scalp, eyebrow, or eyelash regrowth at week 24 sustained their response through week 48 with continued treatment,” the authors wrote. “Some patients, including those with more extensive hair loss, may require ritlecitinib treatment beyond 6 months to achieve target clinical response,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Melissa Piliang, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Cleveland Clinic, and was published online on October 17 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited by its post hoc nature, small sample size in each treatment group, and a follow-up period of only 48 weeks.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Pfizer. Piliang disclosed being a consultant or investigator for Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Procter & Gamble. Six authors were employees or shareholders of or received salary from Pfizer. Other authors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies outside this work, including Pfizer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, and up to one third of nonresponders at week 24 also achieved responses by week 48.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 trial (ALLEGRO) and included 718 adults and adolescents aged 12 or older with severe AA (Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score ≥ 50).

- Patients received various doses of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor ritlecitinib, with or without a 4-week loading dose, including 200/50 mg, 200/30 mg, 50 mg, or 30 mg, with or without a 4-week loading dose for up to 24 weeks and continued to receive their assigned maintenance dose.

- Researchers assessed sustained clinical responses at week 48 for those who had achieved SALT scores ≤ 20 and ≤ 10 at 24 weeks, and nonresponders at week 24 were assessed for responses through week 48.

- Adverse events were also evaluated.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among patients on ritlecitinib who had responded at week 24, SALT responses ≤ 20 were sustained in 85.2%-100% of patients through week 48. Similar results were seen among patients who achieved a SALT score ≤ 10 (68.8%-91.7%) and improvements in eyebrow (70.4%-96.9%) or eyelash (52.4%-94.1%) assessment scores.

- Among those who were nonresponders at week 24, 22.2%-33.7% achieved a SALT score ≤ 20 and 19.8%-25.5% achieved a SALT score ≤ 10 by week 48. Similarly, among those with no eyebrow or eyelash responses at week 24, 19.7%-32.8% and 16.7%-30.2% had improved eyebrow or eyelash assessment scores, respectively, at week 48.