User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

What’s ahead for laser-assisted drug delivery?

SAN DIEGO – Twelve years ago, Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, and colleagues published data from a swine study, which showed for the first time that the ablative fractional laser can be used to boost the uptake of drugs into the skin.

That discovery paved the way for what are now well-established clinical applications of laser-assisted drug delivery for treating actinic keratoses and scars. According to Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, evolving clinical indications for laser-assisted drug delivery include rejuvenation, local anesthesia, melasma, onychomycosis, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and vitiligo, while emerging indications include treatment of skin cancer with PD-1 inhibitors and combination chemotherapy regimens, and vaccinations.

During a presentation at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, she said that researchers have much to learn about laser-assisted drug delivery, including biodistribution of the drug being delivered. Pointing out that so far, “what we have been dealing with is primarily looking at the skin as a black box,” she asked, “what happens when we drill the holes and drugs are applied on top of the skin and swim through the tiny channels?”

By using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and HPLC mass spectrometry to measure drug concentration in the skin, she and her colleagues have observed enhanced uptake of drugs – 4-fold to 40-fold greater – primarily in ex vivo pig skin. “We do know from ex vivo models that it’s much easier to boost the uptake in the skin” when compared with in vivo human use, where much lower drug concentrations are detected, said Dr. Haedersdal, who, along with Emily Wenande, MD, PhD, and R. Rox Anderson, MD, at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, authored a clinical review, published in 2020, on the basics of laser-assisted drug delivery.

“What we are working on now is visualizing what’s taking place when we apply the holes and the drugs in the skin. This is the key to tailoring laser-assisted uptake to specific dermatologic diseases being treated,” she said. To date, she and her colleagues have examined the interaction with tissue using different devices, including ex vivo confocal microscopy, to view the thermal response to ablative fractional laser and radiofrequency. “We want to take that to the next level and look at the drug biodistribution.”

Efforts are underway to compare the pattern of drug distribution with different modes of delivery, such as comparing ablative fractional laser to intradermal needle injection. “We are also working on pneumatic jet injection, which creates a focal drug distribution,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center. “In the future, we may take advantage of device-tailored biodistribution, depending on which clinical indication we are treating.”

Another important aspect to consider is drug retention in the skin. In a study presented as an abstract at the meeting, led by Dr. Wenande, she, Dr. Haedersdal, and colleagues used a pig model to evaluate the effect of three vasoregulative interventions on ablative fractional laser-assisted 5-fluororacil concentrations in in vivo skin. The three interventions were brimonidine 0.33% solution, epinephrine 10 mcg/mL gel, and a 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) in designated treatment areas.

“What we learned from that was in the short term – 1-4 hours – the ablative fractional laser enhanced the uptake of 5-FU, but it was very transient,” with a twofold increased concentration of 5-FU, Dr. Haedersdal said. Over 48-72 hours, after PDL, there was “sustained enhancement of drug in the skin by three to four times,” she noted.

The synergy of systemic drugs with ablative fractional laser therapy is also being evaluated. In a mouse study led by Dr. Haedersdal’s colleague, senior researcher Uffe H. Olesen, PhD, the treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma tumors with a combination of ablative fractional laser and systemic treatment with PD-1 inhibitors resulted in the clearance of more tumors than with either treatment as monotherapy. “What we want to explore is the laser-induced tumor immune response in keratinocyte cancers,” she added.

“When you shine the laser on the skin, there is a robust increase of neutrophilic granulocytes.” Combining this topical immune-boosting response with systemic delivery of PD-1 inhibitors in a mouse model with basal cell carcinoma, she said, “we learned that, when we compare systemic PD-1 inhibitors alone to the laser alone and then with combination therapy, there was an increased tumor clearance of basal cell carcinomas and also enhanced survival of the mice” with the combination, she said. There were also “enhanced neutrophilic counts and both CD4- and CD8-positive cells were increased,” she added.

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received grants or research funding from Lutronic, Venus Concept, Leo Pharma, and Mirai Medical.

SAN DIEGO – Twelve years ago, Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, and colleagues published data from a swine study, which showed for the first time that the ablative fractional laser can be used to boost the uptake of drugs into the skin.

That discovery paved the way for what are now well-established clinical applications of laser-assisted drug delivery for treating actinic keratoses and scars. According to Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, evolving clinical indications for laser-assisted drug delivery include rejuvenation, local anesthesia, melasma, onychomycosis, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and vitiligo, while emerging indications include treatment of skin cancer with PD-1 inhibitors and combination chemotherapy regimens, and vaccinations.

During a presentation at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, she said that researchers have much to learn about laser-assisted drug delivery, including biodistribution of the drug being delivered. Pointing out that so far, “what we have been dealing with is primarily looking at the skin as a black box,” she asked, “what happens when we drill the holes and drugs are applied on top of the skin and swim through the tiny channels?”

By using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and HPLC mass spectrometry to measure drug concentration in the skin, she and her colleagues have observed enhanced uptake of drugs – 4-fold to 40-fold greater – primarily in ex vivo pig skin. “We do know from ex vivo models that it’s much easier to boost the uptake in the skin” when compared with in vivo human use, where much lower drug concentrations are detected, said Dr. Haedersdal, who, along with Emily Wenande, MD, PhD, and R. Rox Anderson, MD, at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, authored a clinical review, published in 2020, on the basics of laser-assisted drug delivery.

“What we are working on now is visualizing what’s taking place when we apply the holes and the drugs in the skin. This is the key to tailoring laser-assisted uptake to specific dermatologic diseases being treated,” she said. To date, she and her colleagues have examined the interaction with tissue using different devices, including ex vivo confocal microscopy, to view the thermal response to ablative fractional laser and radiofrequency. “We want to take that to the next level and look at the drug biodistribution.”

Efforts are underway to compare the pattern of drug distribution with different modes of delivery, such as comparing ablative fractional laser to intradermal needle injection. “We are also working on pneumatic jet injection, which creates a focal drug distribution,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center. “In the future, we may take advantage of device-tailored biodistribution, depending on which clinical indication we are treating.”

Another important aspect to consider is drug retention in the skin. In a study presented as an abstract at the meeting, led by Dr. Wenande, she, Dr. Haedersdal, and colleagues used a pig model to evaluate the effect of three vasoregulative interventions on ablative fractional laser-assisted 5-fluororacil concentrations in in vivo skin. The three interventions were brimonidine 0.33% solution, epinephrine 10 mcg/mL gel, and a 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) in designated treatment areas.

“What we learned from that was in the short term – 1-4 hours – the ablative fractional laser enhanced the uptake of 5-FU, but it was very transient,” with a twofold increased concentration of 5-FU, Dr. Haedersdal said. Over 48-72 hours, after PDL, there was “sustained enhancement of drug in the skin by three to four times,” she noted.

The synergy of systemic drugs with ablative fractional laser therapy is also being evaluated. In a mouse study led by Dr. Haedersdal’s colleague, senior researcher Uffe H. Olesen, PhD, the treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma tumors with a combination of ablative fractional laser and systemic treatment with PD-1 inhibitors resulted in the clearance of more tumors than with either treatment as monotherapy. “What we want to explore is the laser-induced tumor immune response in keratinocyte cancers,” she added.

“When you shine the laser on the skin, there is a robust increase of neutrophilic granulocytes.” Combining this topical immune-boosting response with systemic delivery of PD-1 inhibitors in a mouse model with basal cell carcinoma, she said, “we learned that, when we compare systemic PD-1 inhibitors alone to the laser alone and then with combination therapy, there was an increased tumor clearance of basal cell carcinomas and also enhanced survival of the mice” with the combination, she said. There were also “enhanced neutrophilic counts and both CD4- and CD8-positive cells were increased,” she added.

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received grants or research funding from Lutronic, Venus Concept, Leo Pharma, and Mirai Medical.

SAN DIEGO – Twelve years ago, Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, and colleagues published data from a swine study, which showed for the first time that the ablative fractional laser can be used to boost the uptake of drugs into the skin.

That discovery paved the way for what are now well-established clinical applications of laser-assisted drug delivery for treating actinic keratoses and scars. According to Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, evolving clinical indications for laser-assisted drug delivery include rejuvenation, local anesthesia, melasma, onychomycosis, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and vitiligo, while emerging indications include treatment of skin cancer with PD-1 inhibitors and combination chemotherapy regimens, and vaccinations.

During a presentation at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, she said that researchers have much to learn about laser-assisted drug delivery, including biodistribution of the drug being delivered. Pointing out that so far, “what we have been dealing with is primarily looking at the skin as a black box,” she asked, “what happens when we drill the holes and drugs are applied on top of the skin and swim through the tiny channels?”

By using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and HPLC mass spectrometry to measure drug concentration in the skin, she and her colleagues have observed enhanced uptake of drugs – 4-fold to 40-fold greater – primarily in ex vivo pig skin. “We do know from ex vivo models that it’s much easier to boost the uptake in the skin” when compared with in vivo human use, where much lower drug concentrations are detected, said Dr. Haedersdal, who, along with Emily Wenande, MD, PhD, and R. Rox Anderson, MD, at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, authored a clinical review, published in 2020, on the basics of laser-assisted drug delivery.

“What we are working on now is visualizing what’s taking place when we apply the holes and the drugs in the skin. This is the key to tailoring laser-assisted uptake to specific dermatologic diseases being treated,” she said. To date, she and her colleagues have examined the interaction with tissue using different devices, including ex vivo confocal microscopy, to view the thermal response to ablative fractional laser and radiofrequency. “We want to take that to the next level and look at the drug biodistribution.”

Efforts are underway to compare the pattern of drug distribution with different modes of delivery, such as comparing ablative fractional laser to intradermal needle injection. “We are also working on pneumatic jet injection, which creates a focal drug distribution,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center. “In the future, we may take advantage of device-tailored biodistribution, depending on which clinical indication we are treating.”

Another important aspect to consider is drug retention in the skin. In a study presented as an abstract at the meeting, led by Dr. Wenande, she, Dr. Haedersdal, and colleagues used a pig model to evaluate the effect of three vasoregulative interventions on ablative fractional laser-assisted 5-fluororacil concentrations in in vivo skin. The three interventions were brimonidine 0.33% solution, epinephrine 10 mcg/mL gel, and a 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) in designated treatment areas.

“What we learned from that was in the short term – 1-4 hours – the ablative fractional laser enhanced the uptake of 5-FU, but it was very transient,” with a twofold increased concentration of 5-FU, Dr. Haedersdal said. Over 48-72 hours, after PDL, there was “sustained enhancement of drug in the skin by three to four times,” she noted.

The synergy of systemic drugs with ablative fractional laser therapy is also being evaluated. In a mouse study led by Dr. Haedersdal’s colleague, senior researcher Uffe H. Olesen, PhD, the treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma tumors with a combination of ablative fractional laser and systemic treatment with PD-1 inhibitors resulted in the clearance of more tumors than with either treatment as monotherapy. “What we want to explore is the laser-induced tumor immune response in keratinocyte cancers,” she added.

“When you shine the laser on the skin, there is a robust increase of neutrophilic granulocytes.” Combining this topical immune-boosting response with systemic delivery of PD-1 inhibitors in a mouse model with basal cell carcinoma, she said, “we learned that, when we compare systemic PD-1 inhibitors alone to the laser alone and then with combination therapy, there was an increased tumor clearance of basal cell carcinomas and also enhanced survival of the mice” with the combination, she said. There were also “enhanced neutrophilic counts and both CD4- and CD8-positive cells were increased,” she added.

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received grants or research funding from Lutronic, Venus Concept, Leo Pharma, and Mirai Medical.

AT ASLMS 2022

High rates of med student burnout during COVID

NEW ORLEANS –

Researchers surveyed 613 medical students representing all years of a medical program during the last week of the Spring semester of 2021.

Based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), more than half (54%) of the students had symptoms of burnout.

Eighty percent of students scored high on emotional exhaustion, 57% scored high on cynicism, and 36% scored low on academic effectiveness.

Compared with male medical students, female medical students were more apt to exhibit signs of burnout (60% vs. 44%), emotional exhaustion (80% vs. 73%), and cynicism (62% vs. 49%).

After adjusting for associated factors, female medical students were significantly more likely to suffer from burnout than male students (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-2.70; P < .001).

Smoking was also linked to higher likelihood of burnout among medical students (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.18-3.81; P < .05). The death of a family member from COVID-19 also put medical students at heightened risk for burnout (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.08-2.36; P < .05).

The survey results were presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting.

The findings point to the need to study burnout prevalence in universities and develop strategies to promote the mental health of future physicians, presenter Sofia Jezzini-Martínez, fourth-year medical student, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, wrote in her conference abstract.

In related research presented at the APA meeting, researchers surveyed second-, third-, and fourth-year medical students from California during the pandemic.

Roughly 80% exhibited symptoms of anxiety and 68% exhibited depressive symptoms, of whom about 18% also reported having thoughts of suicide.

Yet only about half of the medical students exhibiting anxiety or depressive symptoms sought help from a mental health professional, and 20% reported using substances to cope with stress.

“Given that the pandemic is ongoing, we hope to draw attention to mental health needs of medical students and influence medical schools to direct appropriate and timely resources to this group,” presenter Sarthak Angal, MD, psychiatry resident, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, California, wrote in his conference abstract.

Managing expectations

Weighing in on medical student burnout, Ihuoma Njoku, MD, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, noted that, “particularly for women in multiple fields, including medicine, there’s a lot of burden placed on them.”

“Women are pulled in a lot of different directions and have increased demands, which may help explain their higher rate of burnout,” Dr. Njoku commented.

She noted that these surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “a period when students’ education experience was a lot different than what they expected and maybe what they wanted.”

Dr. Njoku noted that the challenges of the pandemic are particularly hard on fourth-year medical students.

“A big part of fourth year is applying to residency, and many were doing virtual interviews for residency. That makes it hard to really get an appreciation of the place you will spend the next three to eight years of your life,” she told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS –

Researchers surveyed 613 medical students representing all years of a medical program during the last week of the Spring semester of 2021.

Based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), more than half (54%) of the students had symptoms of burnout.

Eighty percent of students scored high on emotional exhaustion, 57% scored high on cynicism, and 36% scored low on academic effectiveness.

Compared with male medical students, female medical students were more apt to exhibit signs of burnout (60% vs. 44%), emotional exhaustion (80% vs. 73%), and cynicism (62% vs. 49%).

After adjusting for associated factors, female medical students were significantly more likely to suffer from burnout than male students (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-2.70; P < .001).

Smoking was also linked to higher likelihood of burnout among medical students (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.18-3.81; P < .05). The death of a family member from COVID-19 also put medical students at heightened risk for burnout (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.08-2.36; P < .05).

The survey results were presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting.

The findings point to the need to study burnout prevalence in universities and develop strategies to promote the mental health of future physicians, presenter Sofia Jezzini-Martínez, fourth-year medical student, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, wrote in her conference abstract.

In related research presented at the APA meeting, researchers surveyed second-, third-, and fourth-year medical students from California during the pandemic.

Roughly 80% exhibited symptoms of anxiety and 68% exhibited depressive symptoms, of whom about 18% also reported having thoughts of suicide.

Yet only about half of the medical students exhibiting anxiety or depressive symptoms sought help from a mental health professional, and 20% reported using substances to cope with stress.

“Given that the pandemic is ongoing, we hope to draw attention to mental health needs of medical students and influence medical schools to direct appropriate and timely resources to this group,” presenter Sarthak Angal, MD, psychiatry resident, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, California, wrote in his conference abstract.

Managing expectations

Weighing in on medical student burnout, Ihuoma Njoku, MD, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, noted that, “particularly for women in multiple fields, including medicine, there’s a lot of burden placed on them.”

“Women are pulled in a lot of different directions and have increased demands, which may help explain their higher rate of burnout,” Dr. Njoku commented.

She noted that these surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “a period when students’ education experience was a lot different than what they expected and maybe what they wanted.”

Dr. Njoku noted that the challenges of the pandemic are particularly hard on fourth-year medical students.

“A big part of fourth year is applying to residency, and many were doing virtual interviews for residency. That makes it hard to really get an appreciation of the place you will spend the next three to eight years of your life,” she told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS –

Researchers surveyed 613 medical students representing all years of a medical program during the last week of the Spring semester of 2021.

Based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), more than half (54%) of the students had symptoms of burnout.

Eighty percent of students scored high on emotional exhaustion, 57% scored high on cynicism, and 36% scored low on academic effectiveness.

Compared with male medical students, female medical students were more apt to exhibit signs of burnout (60% vs. 44%), emotional exhaustion (80% vs. 73%), and cynicism (62% vs. 49%).

After adjusting for associated factors, female medical students were significantly more likely to suffer from burnout than male students (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-2.70; P < .001).

Smoking was also linked to higher likelihood of burnout among medical students (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.18-3.81; P < .05). The death of a family member from COVID-19 also put medical students at heightened risk for burnout (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.08-2.36; P < .05).

The survey results were presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting.

The findings point to the need to study burnout prevalence in universities and develop strategies to promote the mental health of future physicians, presenter Sofia Jezzini-Martínez, fourth-year medical student, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, wrote in her conference abstract.

In related research presented at the APA meeting, researchers surveyed second-, third-, and fourth-year medical students from California during the pandemic.

Roughly 80% exhibited symptoms of anxiety and 68% exhibited depressive symptoms, of whom about 18% also reported having thoughts of suicide.

Yet only about half of the medical students exhibiting anxiety or depressive symptoms sought help from a mental health professional, and 20% reported using substances to cope with stress.

“Given that the pandemic is ongoing, we hope to draw attention to mental health needs of medical students and influence medical schools to direct appropriate and timely resources to this group,” presenter Sarthak Angal, MD, psychiatry resident, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, California, wrote in his conference abstract.

Managing expectations

Weighing in on medical student burnout, Ihuoma Njoku, MD, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, noted that, “particularly for women in multiple fields, including medicine, there’s a lot of burden placed on them.”

“Women are pulled in a lot of different directions and have increased demands, which may help explain their higher rate of burnout,” Dr. Njoku commented.

She noted that these surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “a period when students’ education experience was a lot different than what they expected and maybe what they wanted.”

Dr. Njoku noted that the challenges of the pandemic are particularly hard on fourth-year medical students.

“A big part of fourth year is applying to residency, and many were doing virtual interviews for residency. That makes it hard to really get an appreciation of the place you will spend the next three to eight years of your life,” she told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM APA 2022

Can lasers be used to measure nerve sensitivity in the skin?

SAN DIEGO – In a 2006 report of complications from laser dermatologic surgery, one of the authors, Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, who had subjected his forearm to treatment with a fractional laser skin resurfacing prototype device, was included as 1 of the 19 featured cases.

Dr. Manstein, of the Cutaneous Biology Research Center in the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was exposed to three test spots in the evaluation of the effects of different microscopic thermal zone densities for the prototype device, emitting at 1,450 nm and an energy per MTZ of 3 mJ.

Two years later, hypopigmentation persisted at the test site treated with the highest MTZ density, while two other sites treated with the lower MTZ densities did not show any dyspigmentation. But he noticed something else during the experiment: He felt minimal to no pain as each test site was being treated.

“It took 7 minutes without any cooling or anesthesia,” Dr. Manstein recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It was not completely painless, but each time the laser was applied, sometimes I felt a little prick, sometimes I felt nothing.” Essentially, he added, “we created cell injury with a focused laser beam without anesthesia,” but this could also indicate that if skin is treated with a fractional laser very slowly, anesthesia is not needed. “Current devices are meant to treat very quickly, but if we [treat] slowly, maybe you could remove lesions painlessly without anesthesia.”

The observation from that experiment also led Dr. Manstein and colleagues to wonder: Could a focused laser beam pattern be used to assess cutaneous innervation? If so, they postulated, perhaps it could be used to not only assess nerve sensitivity of candidates for dermatologic surgery, but as a tool to help diagnose small fiber neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathies in patients with HIV and sarcoidosis.

The current gold standard for making these diagnoses involves a skin biopsy, immunohistochemical analysis, and nerve fiber quantification, which is not widely available. It also requires strict histologic processing and nerve counting rules. Confocal microscopy of nerve fibers in the cornea is another approach, but is very difficult to perform, “so it would be nice if there was a simple way” to determine nerve fiber density in the skin using a focused laser beam, Dr. Manstein said.

With help from Payal Patel, MD, a dermatology research fellow at MGH, records each subject’s perception of a stimulus, and maps the areas of stimulus response. Current diameters being studied range from 0.076-1.15 mm and depths less than 0.71 mm. “We can focus the laser beam, preset the beam diameter, and very slowly, in a controlled manner, make a rectangular pattern, and after each time, inquire if the subject felt the pulse or not,” Dr. Manstein explained.

“This laser could become a new method for diagnosing nerve fiber neuropathies. If this works well, I think we can miniaturize the device,” he added.

Dr. Manstein disclosed that he is a consultant for Blossom Innovations, R2 Dermatology, and AVAVA. He is also a member of the advisory board for Blossom Innovations.

SAN DIEGO – In a 2006 report of complications from laser dermatologic surgery, one of the authors, Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, who had subjected his forearm to treatment with a fractional laser skin resurfacing prototype device, was included as 1 of the 19 featured cases.

Dr. Manstein, of the Cutaneous Biology Research Center in the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was exposed to three test spots in the evaluation of the effects of different microscopic thermal zone densities for the prototype device, emitting at 1,450 nm and an energy per MTZ of 3 mJ.

Two years later, hypopigmentation persisted at the test site treated with the highest MTZ density, while two other sites treated with the lower MTZ densities did not show any dyspigmentation. But he noticed something else during the experiment: He felt minimal to no pain as each test site was being treated.

“It took 7 minutes without any cooling or anesthesia,” Dr. Manstein recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It was not completely painless, but each time the laser was applied, sometimes I felt a little prick, sometimes I felt nothing.” Essentially, he added, “we created cell injury with a focused laser beam without anesthesia,” but this could also indicate that if skin is treated with a fractional laser very slowly, anesthesia is not needed. “Current devices are meant to treat very quickly, but if we [treat] slowly, maybe you could remove lesions painlessly without anesthesia.”

The observation from that experiment also led Dr. Manstein and colleagues to wonder: Could a focused laser beam pattern be used to assess cutaneous innervation? If so, they postulated, perhaps it could be used to not only assess nerve sensitivity of candidates for dermatologic surgery, but as a tool to help diagnose small fiber neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathies in patients with HIV and sarcoidosis.

The current gold standard for making these diagnoses involves a skin biopsy, immunohistochemical analysis, and nerve fiber quantification, which is not widely available. It also requires strict histologic processing and nerve counting rules. Confocal microscopy of nerve fibers in the cornea is another approach, but is very difficult to perform, “so it would be nice if there was a simple way” to determine nerve fiber density in the skin using a focused laser beam, Dr. Manstein said.

With help from Payal Patel, MD, a dermatology research fellow at MGH, records each subject’s perception of a stimulus, and maps the areas of stimulus response. Current diameters being studied range from 0.076-1.15 mm and depths less than 0.71 mm. “We can focus the laser beam, preset the beam diameter, and very slowly, in a controlled manner, make a rectangular pattern, and after each time, inquire if the subject felt the pulse or not,” Dr. Manstein explained.

“This laser could become a new method for diagnosing nerve fiber neuropathies. If this works well, I think we can miniaturize the device,” he added.

Dr. Manstein disclosed that he is a consultant for Blossom Innovations, R2 Dermatology, and AVAVA. He is also a member of the advisory board for Blossom Innovations.

SAN DIEGO – In a 2006 report of complications from laser dermatologic surgery, one of the authors, Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, who had subjected his forearm to treatment with a fractional laser skin resurfacing prototype device, was included as 1 of the 19 featured cases.

Dr. Manstein, of the Cutaneous Biology Research Center in the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was exposed to three test spots in the evaluation of the effects of different microscopic thermal zone densities for the prototype device, emitting at 1,450 nm and an energy per MTZ of 3 mJ.

Two years later, hypopigmentation persisted at the test site treated with the highest MTZ density, while two other sites treated with the lower MTZ densities did not show any dyspigmentation. But he noticed something else during the experiment: He felt minimal to no pain as each test site was being treated.

“It took 7 minutes without any cooling or anesthesia,” Dr. Manstein recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It was not completely painless, but each time the laser was applied, sometimes I felt a little prick, sometimes I felt nothing.” Essentially, he added, “we created cell injury with a focused laser beam without anesthesia,” but this could also indicate that if skin is treated with a fractional laser very slowly, anesthesia is not needed. “Current devices are meant to treat very quickly, but if we [treat] slowly, maybe you could remove lesions painlessly without anesthesia.”

The observation from that experiment also led Dr. Manstein and colleagues to wonder: Could a focused laser beam pattern be used to assess cutaneous innervation? If so, they postulated, perhaps it could be used to not only assess nerve sensitivity of candidates for dermatologic surgery, but as a tool to help diagnose small fiber neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathies in patients with HIV and sarcoidosis.

The current gold standard for making these diagnoses involves a skin biopsy, immunohistochemical analysis, and nerve fiber quantification, which is not widely available. It also requires strict histologic processing and nerve counting rules. Confocal microscopy of nerve fibers in the cornea is another approach, but is very difficult to perform, “so it would be nice if there was a simple way” to determine nerve fiber density in the skin using a focused laser beam, Dr. Manstein said.

With help from Payal Patel, MD, a dermatology research fellow at MGH, records each subject’s perception of a stimulus, and maps the areas of stimulus response. Current diameters being studied range from 0.076-1.15 mm and depths less than 0.71 mm. “We can focus the laser beam, preset the beam diameter, and very slowly, in a controlled manner, make a rectangular pattern, and after each time, inquire if the subject felt the pulse or not,” Dr. Manstein explained.

“This laser could become a new method for diagnosing nerve fiber neuropathies. If this works well, I think we can miniaturize the device,” he added.

Dr. Manstein disclosed that he is a consultant for Blossom Innovations, R2 Dermatology, and AVAVA. He is also a member of the advisory board for Blossom Innovations.

AT ASLMS 2022

CDC says about 20% get long COVID. New models try to define it

As the number of people reporting persistent, and sometimes debilitating, symptoms from COVID-19 increases, researchers have struggled to pinpoint exactly how common so-called “long COVID” is, as well as how to clearly define exactly who has it or who is likely to get it.

Now, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention researchers have concluded that one in five adults aged 18 and older have at least one health condition that might be related to their previous COVID-19 illness; that number goes up to one in four among those 65 and older. Their data was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The conditions associated with what’s been officially termed postacute sequelae of COVID-19, or PASC, include kidney failure, blood clots, other vascular issues, respiratory issues, heart problems, mental health or neurologic problems, and musculoskeletal conditions. But none of those conditions is unique to long COVID.

Another new study, published in The Lancet Digital Health, is trying to help better characterize what long COVID is, and what it isn’t.

that could help identify those likely to develop it.

CDC data

The CDC team came to its conclusions by evaluating the EHRs of more than 353,000 adults who were diagnosed with COVID-19 or got a positive test result, then comparing those records with 1.6 million patients who had a medical visit in the same month without a positive test result or a COVID-19 diagnosis.

They looked at data from March 2020 to November 2021, tagging 26 conditions often linked to post-COVID issues.

Overall, more than 38% of the COVID patients and 16% of those without COVID had at least one of these 26 conditions. They assessed the absolute risk difference between the patients and the non-COVID patients who developed one of the conditions, finding a 20.8–percentage point difference for those 18-64, yielding the one in five figure, and a 26.9–percentage point difference for those 65 and above, translating to about one in four.

“These findings suggest the need for increased awareness for post-COVID conditions so that improved post-COVID care and management of patients who survived COVID-19 can be developed and implemented,” said study author Lara Bull-Otterson, PhD, MPH, colead of data analytics at the Healthcare Data Advisory Unit of the CDC.

Pinpointing long COVID characteristics

Long COVID is difficult to identify, because many of its symptoms are similar to those of other conditions, so researchers are looking for better ways to characterize it to help improve both diagnosis and treatment.

Researchers on the Lancet study evaluated data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, N3C, a national NIH database that includes information from more than 8 million people. The team looked at the health records of 98,000 adult COVID patients and used that information, along with data from about nearly 600 long-COVID patients treated at three long-COVID clinics, to create three machine learning models for identifying long-COVID patients.

The models aimed to identify long-COVID patients in three groups: all patients, those hospitalized with COVID, and those with COVID but not hospitalized. The models were judged by the researchers to be accurate because those identified at risk for long COVID from the database were similar to those actually treated for long COVID at the clinics.

“Our algorithm is not intended to diagnose long COVID,” said lead author Emily Pfaff, PhD, research assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Rather, it is intended to identify patients in EHR data who ‘look like’ patients seen by physicians for long COVID.’’

Next, the researchers say, they will incorporate the new patterns they found with a diagnosis code for COVID and include it in the models to further test their accuracy. The models could also be used to help recruit patients for clinical trials, the researchers say.

Perspective and caveats

The figures of one in five and one in four found by the CDC researchers don’t surprise David Putrino, PT, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation for Mount Sinai Health System in New York and director of its Abilities Research Center, which cares for long-COVID patients.

“Those numbers are high and it’s alarming,” he said. “But we’ve been sounding the alarm for quite some time, and we’ve been assuming that about one in five end up with long COVID.”

He does see a limitation to the CDC research – that some symptoms could have emerged later, and some in the control group could have had an undiagnosed COVID infection and gone on to develop long COVID.

As for machine learning, “this is something we need to approach with caution,” Dr. Putrino said. “There are a lot of variables we don’t understand about long COVID,’’ and that could result in spurious conclusions.

“Although I am supportive of this work going on, I am saying, ‘Scrutinize the tools with a grain of salt.’ Electronic records, Dr. Putrino points out, include information that the doctors enter, not what the patient says.

Dr. Pfaff responds: “It is entirely appropriate to approach both machine learning and EHR data with relevant caveats in mind. There are many clinical factors that are not recorded in the EHR, and the EHR is not representative of all persons with long COVID.” Those data can only reflect those who seek care for a condition, a natural limitation.

When it comes to algorithms, they are limited by data they have access to, such as the electronic health records in this research. However, the immense size and diversity in the data used “does allow us to make some assertations with much more confidence than if we were using data from a single or small number of health care systems,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the number of people reporting persistent, and sometimes debilitating, symptoms from COVID-19 increases, researchers have struggled to pinpoint exactly how common so-called “long COVID” is, as well as how to clearly define exactly who has it or who is likely to get it.

Now, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention researchers have concluded that one in five adults aged 18 and older have at least one health condition that might be related to their previous COVID-19 illness; that number goes up to one in four among those 65 and older. Their data was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The conditions associated with what’s been officially termed postacute sequelae of COVID-19, or PASC, include kidney failure, blood clots, other vascular issues, respiratory issues, heart problems, mental health or neurologic problems, and musculoskeletal conditions. But none of those conditions is unique to long COVID.

Another new study, published in The Lancet Digital Health, is trying to help better characterize what long COVID is, and what it isn’t.

that could help identify those likely to develop it.

CDC data

The CDC team came to its conclusions by evaluating the EHRs of more than 353,000 adults who were diagnosed with COVID-19 or got a positive test result, then comparing those records with 1.6 million patients who had a medical visit in the same month without a positive test result or a COVID-19 diagnosis.

They looked at data from March 2020 to November 2021, tagging 26 conditions often linked to post-COVID issues.

Overall, more than 38% of the COVID patients and 16% of those without COVID had at least one of these 26 conditions. They assessed the absolute risk difference between the patients and the non-COVID patients who developed one of the conditions, finding a 20.8–percentage point difference for those 18-64, yielding the one in five figure, and a 26.9–percentage point difference for those 65 and above, translating to about one in four.

“These findings suggest the need for increased awareness for post-COVID conditions so that improved post-COVID care and management of patients who survived COVID-19 can be developed and implemented,” said study author Lara Bull-Otterson, PhD, MPH, colead of data analytics at the Healthcare Data Advisory Unit of the CDC.

Pinpointing long COVID characteristics

Long COVID is difficult to identify, because many of its symptoms are similar to those of other conditions, so researchers are looking for better ways to characterize it to help improve both diagnosis and treatment.

Researchers on the Lancet study evaluated data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, N3C, a national NIH database that includes information from more than 8 million people. The team looked at the health records of 98,000 adult COVID patients and used that information, along with data from about nearly 600 long-COVID patients treated at three long-COVID clinics, to create three machine learning models for identifying long-COVID patients.

The models aimed to identify long-COVID patients in three groups: all patients, those hospitalized with COVID, and those with COVID but not hospitalized. The models were judged by the researchers to be accurate because those identified at risk for long COVID from the database were similar to those actually treated for long COVID at the clinics.

“Our algorithm is not intended to diagnose long COVID,” said lead author Emily Pfaff, PhD, research assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Rather, it is intended to identify patients in EHR data who ‘look like’ patients seen by physicians for long COVID.’’

Next, the researchers say, they will incorporate the new patterns they found with a diagnosis code for COVID and include it in the models to further test their accuracy. The models could also be used to help recruit patients for clinical trials, the researchers say.

Perspective and caveats

The figures of one in five and one in four found by the CDC researchers don’t surprise David Putrino, PT, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation for Mount Sinai Health System in New York and director of its Abilities Research Center, which cares for long-COVID patients.

“Those numbers are high and it’s alarming,” he said. “But we’ve been sounding the alarm for quite some time, and we’ve been assuming that about one in five end up with long COVID.”

He does see a limitation to the CDC research – that some symptoms could have emerged later, and some in the control group could have had an undiagnosed COVID infection and gone on to develop long COVID.

As for machine learning, “this is something we need to approach with caution,” Dr. Putrino said. “There are a lot of variables we don’t understand about long COVID,’’ and that could result in spurious conclusions.

“Although I am supportive of this work going on, I am saying, ‘Scrutinize the tools with a grain of salt.’ Electronic records, Dr. Putrino points out, include information that the doctors enter, not what the patient says.

Dr. Pfaff responds: “It is entirely appropriate to approach both machine learning and EHR data with relevant caveats in mind. There are many clinical factors that are not recorded in the EHR, and the EHR is not representative of all persons with long COVID.” Those data can only reflect those who seek care for a condition, a natural limitation.

When it comes to algorithms, they are limited by data they have access to, such as the electronic health records in this research. However, the immense size and diversity in the data used “does allow us to make some assertations with much more confidence than if we were using data from a single or small number of health care systems,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the number of people reporting persistent, and sometimes debilitating, symptoms from COVID-19 increases, researchers have struggled to pinpoint exactly how common so-called “long COVID” is, as well as how to clearly define exactly who has it or who is likely to get it.

Now, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention researchers have concluded that one in five adults aged 18 and older have at least one health condition that might be related to their previous COVID-19 illness; that number goes up to one in four among those 65 and older. Their data was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The conditions associated with what’s been officially termed postacute sequelae of COVID-19, or PASC, include kidney failure, blood clots, other vascular issues, respiratory issues, heart problems, mental health or neurologic problems, and musculoskeletal conditions. But none of those conditions is unique to long COVID.

Another new study, published in The Lancet Digital Health, is trying to help better characterize what long COVID is, and what it isn’t.

that could help identify those likely to develop it.

CDC data

The CDC team came to its conclusions by evaluating the EHRs of more than 353,000 adults who were diagnosed with COVID-19 or got a positive test result, then comparing those records with 1.6 million patients who had a medical visit in the same month without a positive test result or a COVID-19 diagnosis.

They looked at data from March 2020 to November 2021, tagging 26 conditions often linked to post-COVID issues.

Overall, more than 38% of the COVID patients and 16% of those without COVID had at least one of these 26 conditions. They assessed the absolute risk difference between the patients and the non-COVID patients who developed one of the conditions, finding a 20.8–percentage point difference for those 18-64, yielding the one in five figure, and a 26.9–percentage point difference for those 65 and above, translating to about one in four.

“These findings suggest the need for increased awareness for post-COVID conditions so that improved post-COVID care and management of patients who survived COVID-19 can be developed and implemented,” said study author Lara Bull-Otterson, PhD, MPH, colead of data analytics at the Healthcare Data Advisory Unit of the CDC.

Pinpointing long COVID characteristics

Long COVID is difficult to identify, because many of its symptoms are similar to those of other conditions, so researchers are looking for better ways to characterize it to help improve both diagnosis and treatment.

Researchers on the Lancet study evaluated data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, N3C, a national NIH database that includes information from more than 8 million people. The team looked at the health records of 98,000 adult COVID patients and used that information, along with data from about nearly 600 long-COVID patients treated at three long-COVID clinics, to create three machine learning models for identifying long-COVID patients.

The models aimed to identify long-COVID patients in three groups: all patients, those hospitalized with COVID, and those with COVID but not hospitalized. The models were judged by the researchers to be accurate because those identified at risk for long COVID from the database were similar to those actually treated for long COVID at the clinics.

“Our algorithm is not intended to diagnose long COVID,” said lead author Emily Pfaff, PhD, research assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Rather, it is intended to identify patients in EHR data who ‘look like’ patients seen by physicians for long COVID.’’

Next, the researchers say, they will incorporate the new patterns they found with a diagnosis code for COVID and include it in the models to further test their accuracy. The models could also be used to help recruit patients for clinical trials, the researchers say.

Perspective and caveats

The figures of one in five and one in four found by the CDC researchers don’t surprise David Putrino, PT, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation for Mount Sinai Health System in New York and director of its Abilities Research Center, which cares for long-COVID patients.

“Those numbers are high and it’s alarming,” he said. “But we’ve been sounding the alarm for quite some time, and we’ve been assuming that about one in five end up with long COVID.”

He does see a limitation to the CDC research – that some symptoms could have emerged later, and some in the control group could have had an undiagnosed COVID infection and gone on to develop long COVID.

As for machine learning, “this is something we need to approach with caution,” Dr. Putrino said. “There are a lot of variables we don’t understand about long COVID,’’ and that could result in spurious conclusions.

“Although I am supportive of this work going on, I am saying, ‘Scrutinize the tools with a grain of salt.’ Electronic records, Dr. Putrino points out, include information that the doctors enter, not what the patient says.

Dr. Pfaff responds: “It is entirely appropriate to approach both machine learning and EHR data with relevant caveats in mind. There are many clinical factors that are not recorded in the EHR, and the EHR is not representative of all persons with long COVID.” Those data can only reflect those who seek care for a condition, a natural limitation.

When it comes to algorithms, they are limited by data they have access to, such as the electronic health records in this research. However, the immense size and diversity in the data used “does allow us to make some assertations with much more confidence than if we were using data from a single or small number of health care systems,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Acute Alopecia Associated With Albendazole Toxicosis

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

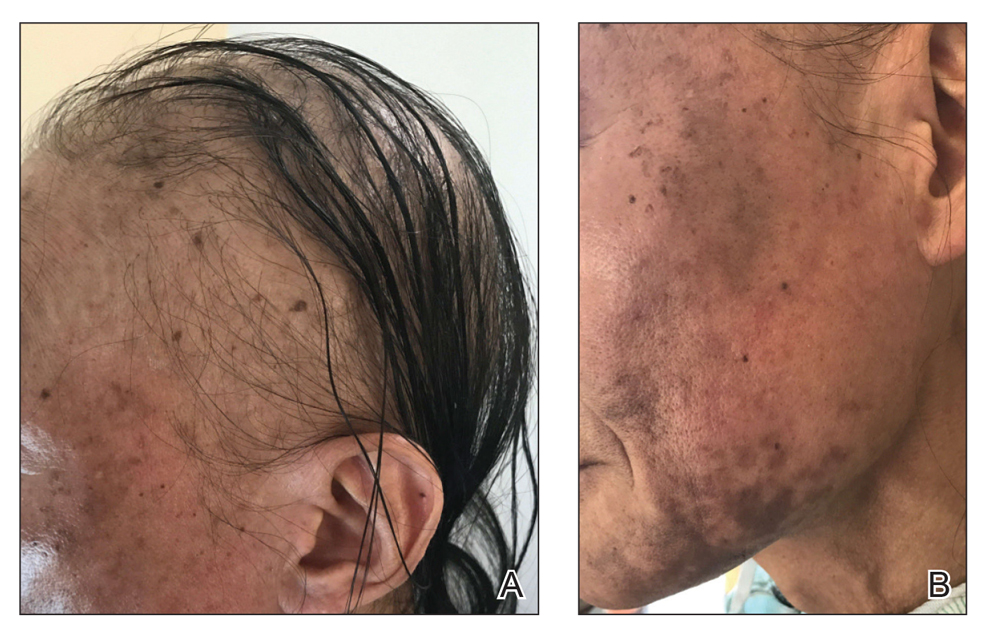

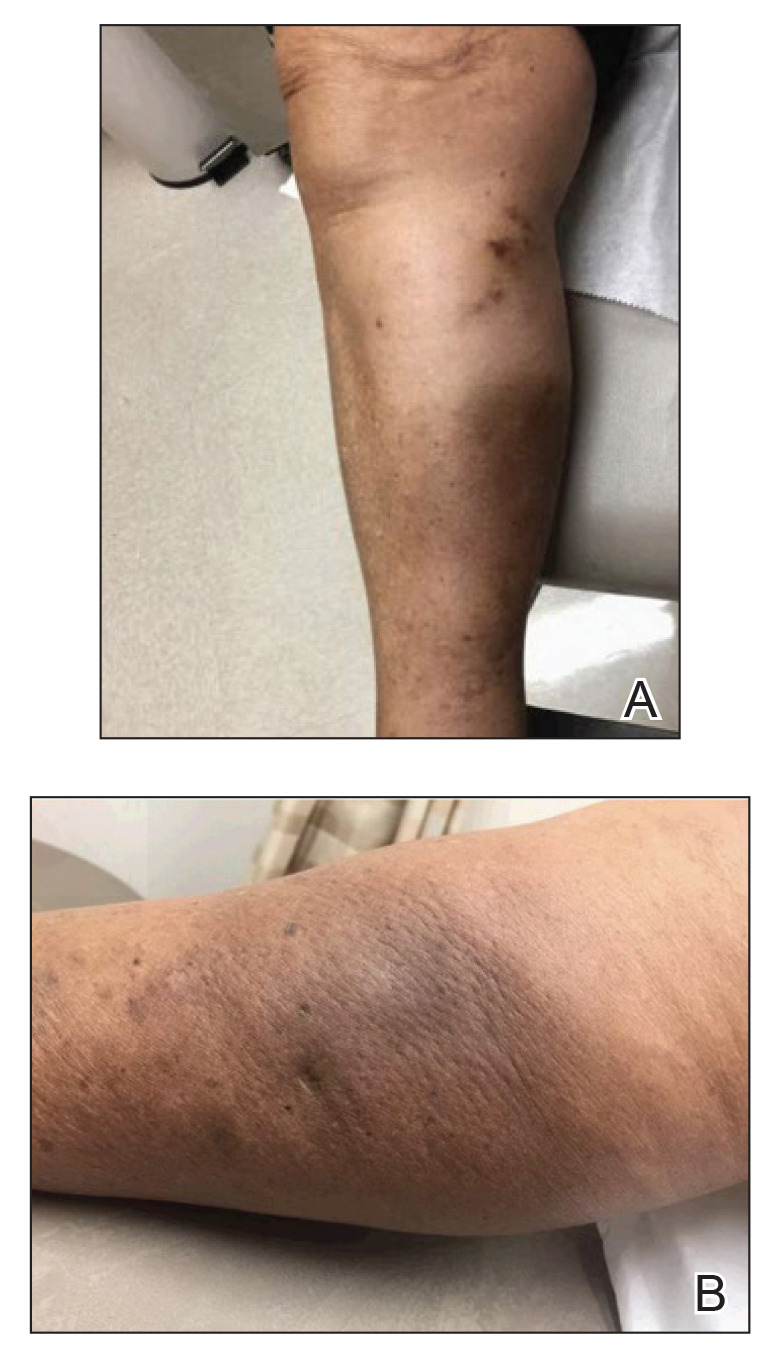

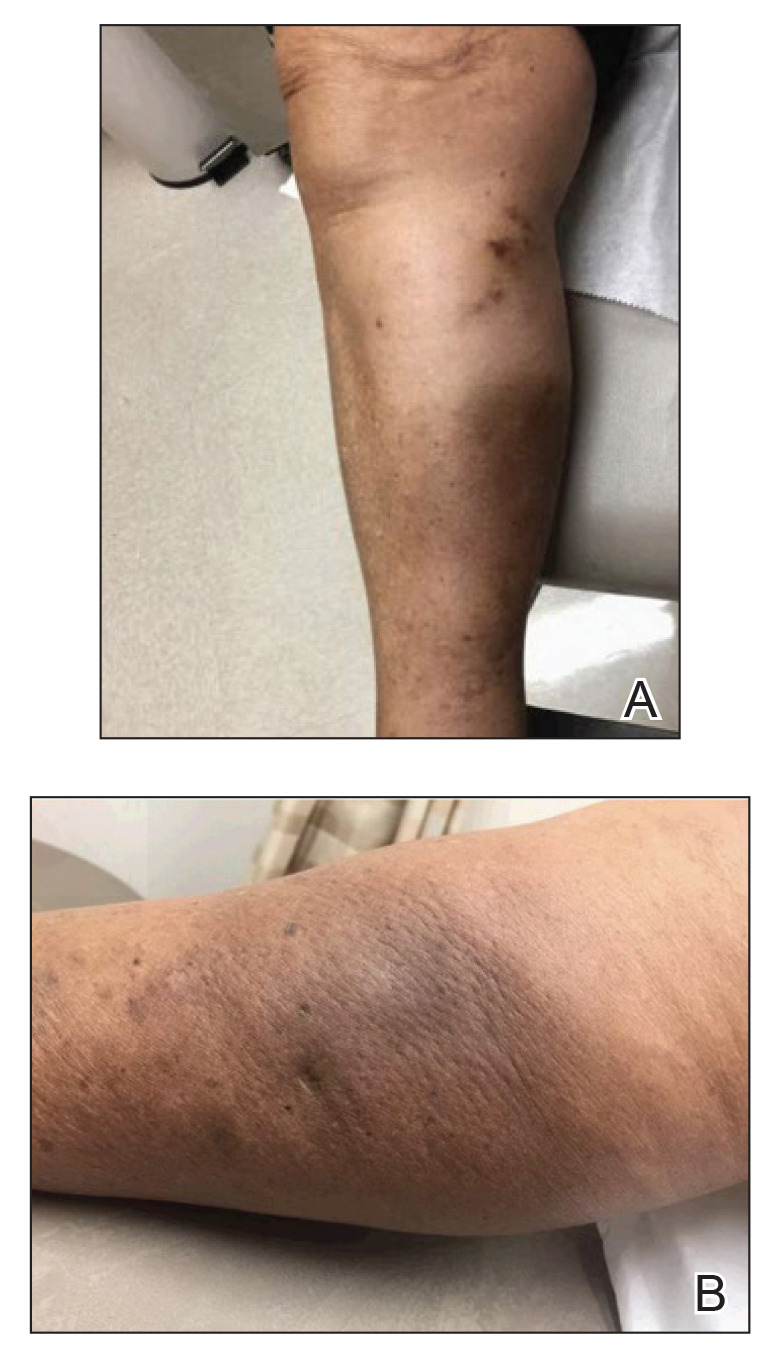

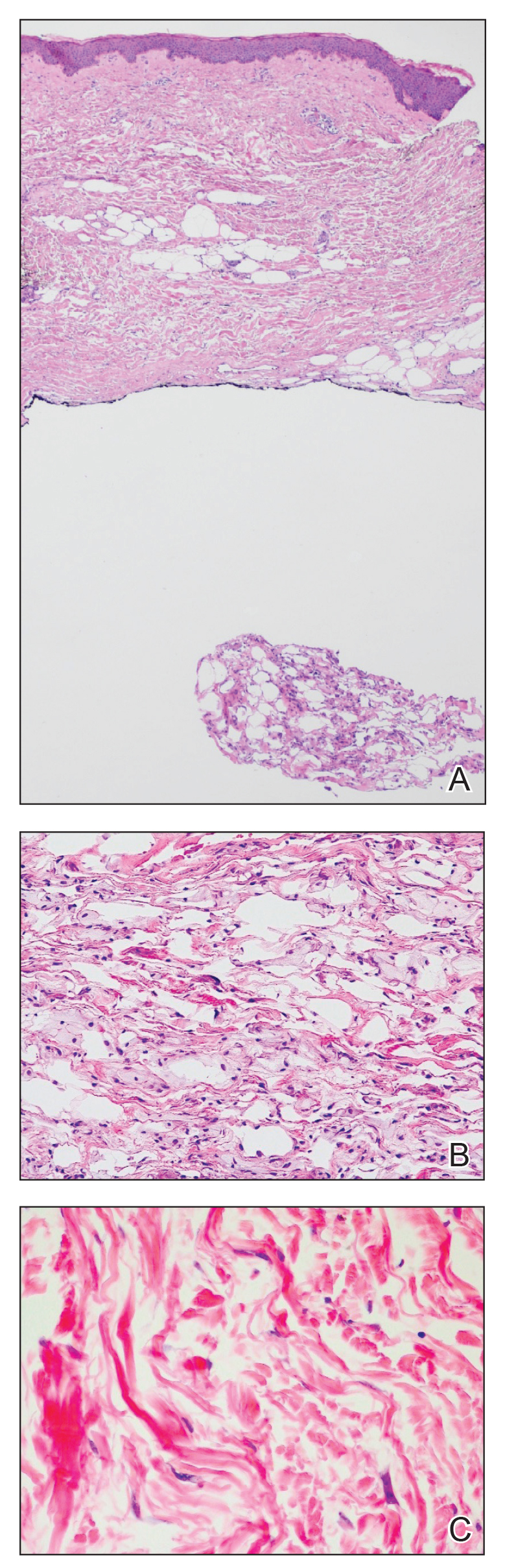

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

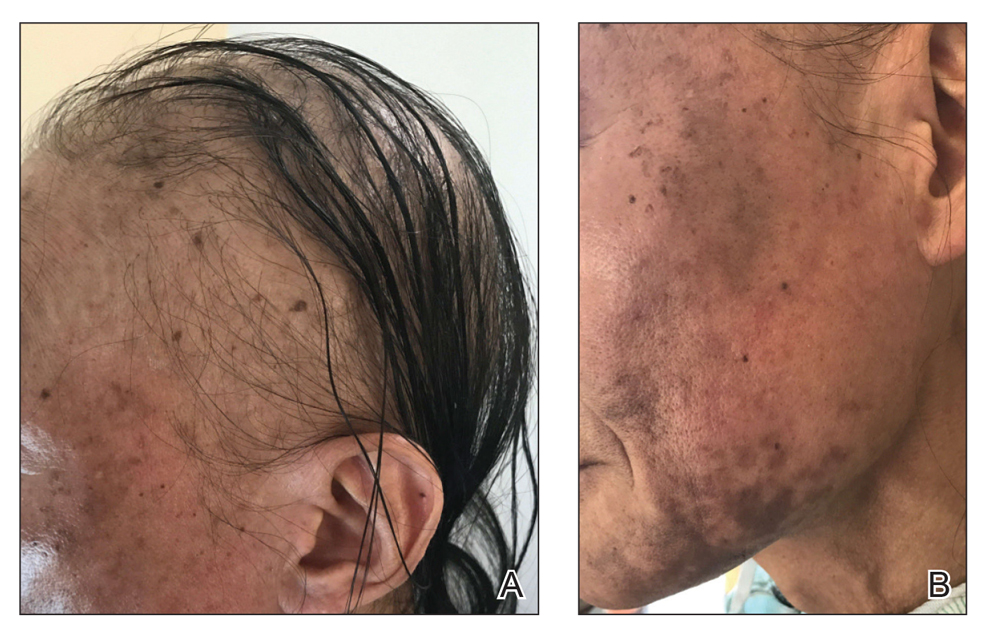

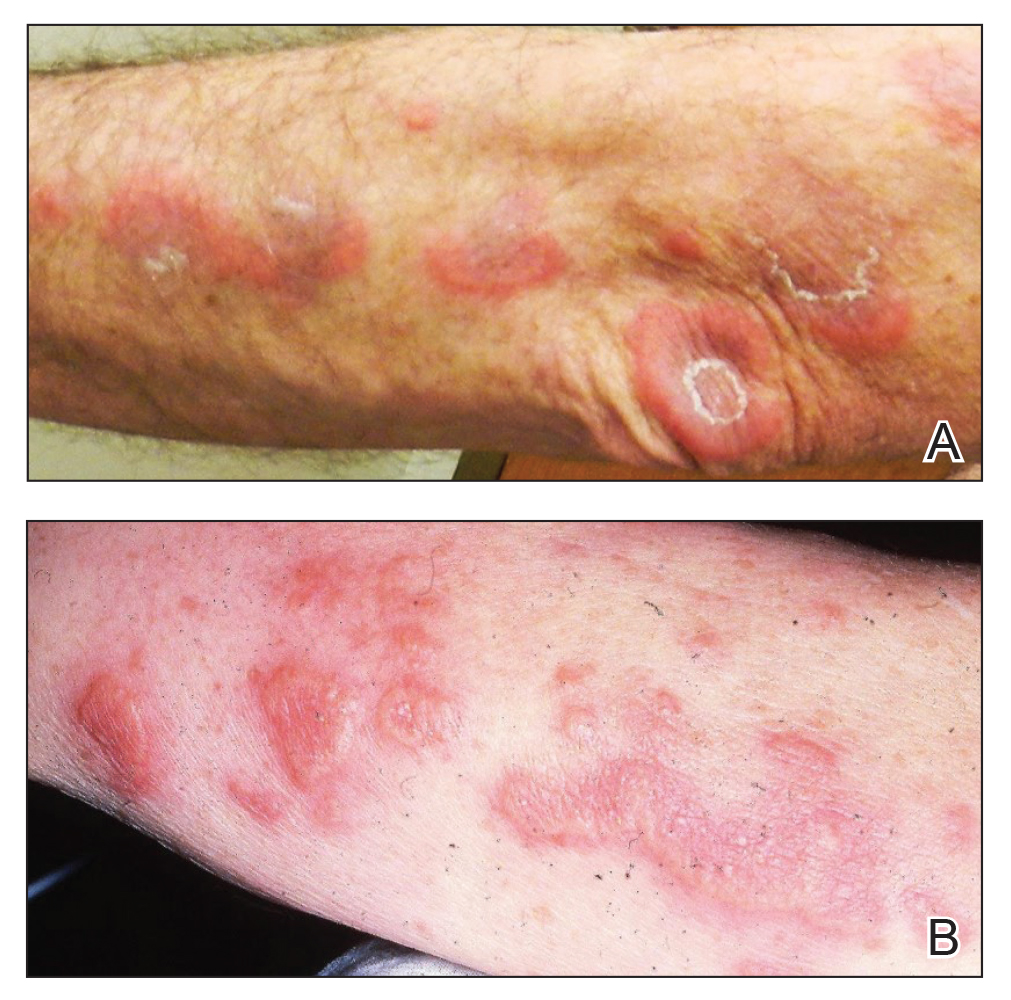

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937-1948. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1937

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-1532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4

- Lanusse CE, Prichard RK. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of benzimidazole anthelmintics in ruminants. Drug Metab Rev. 1993;25:235-279. doi:10.3109/03602539308993977

- Page SW. Antiparasitic drugs. In: Maddison JE, Church DB, Page SW, eds. Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; 2008:198-260.

- Yun SJ, Kim S-J. Hair loss pattern due to chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium: a cross-sectional observation. Dermatology. 2007;215:36-40. doi:10.1159/000102031

- de Weger VA, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Cellular and clinical pharmacology of the taxanes docetaxel and paclitaxel—a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:488-494. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000093

- Paus R, Haslam IS, Sharov AA, et al. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:E50-E59. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70553-3

- Imamkuliev KD, Alekseev VG, Dovgalev AS, et al. A case of alopecia in a patient with hydatid disease treated with Nemozole (albendazole)[in Russian]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2013:48-50.

- Tas A, Köklü S, Celik H. Loss of body hair as a side effect of albendazole. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:220. doi:10.1007/s00508-011-0112-y

- Pilar García-Muret M, Sitjas D, Tuneu L, et al. Telogen effluvium associated with albendazole therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:669-670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02597.x

- Ghias M, Amin B, Kutner A. Albendazole-induced anagen effluvium. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:54-56.

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937-1948. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1937

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-1532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4

- Lanusse CE, Prichard RK. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of benzimidazole anthelmintics in ruminants. Drug Metab Rev. 1993;25:235-279. doi:10.3109/03602539308993977

- Page SW. Antiparasitic drugs. In: Maddison JE, Church DB, Page SW, eds. Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; 2008:198-260.

- Yun SJ, Kim S-J. Hair loss pattern due to chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium: a cross-sectional observation. Dermatology. 2007;215:36-40. doi:10.1159/000102031

- de Weger VA, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Cellular and clinical pharmacology of the taxanes docetaxel and paclitaxel—a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:488-494. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000093

- Paus R, Haslam IS, Sharov AA, et al. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:E50-E59. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70553-3

- Imamkuliev KD, Alekseev VG, Dovgalev AS, et al. A case of alopecia in a patient with hydatid disease treated with Nemozole (albendazole)[in Russian]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2013:48-50.

- Tas A, Köklü S, Celik H. Loss of body hair as a side effect of albendazole. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:220. doi:10.1007/s00508-011-0112-y

- Pilar García-Muret M, Sitjas D, Tuneu L, et al. Telogen effluvium associated with albendazole therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:669-670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02597.x

- Ghias M, Amin B, Kutner A. Albendazole-induced anagen effluvium. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:54-56.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937-1948. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1937

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-1532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4

- Lanusse CE, Prichard RK. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of benzimidazole anthelmintics in ruminants. Drug Metab Rev. 1993;25:235-279. doi:10.3109/03602539308993977

- Page SW. Antiparasitic drugs. In: Maddison JE, Church DB, Page SW, eds. Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; 2008:198-260.

- Yun SJ, Kim S-J. Hair loss pattern due to chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium: a cross-sectional observation. Dermatology. 2007;215:36-40. doi:10.1159/000102031

- de Weger VA, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Cellular and clinical pharmacology of the taxanes docetaxel and paclitaxel—a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:488-494. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000093

- Paus R, Haslam IS, Sharov AA, et al. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:E50-E59. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70553-3

- Imamkuliev KD, Alekseev VG, Dovgalev AS, et al. A case of alopecia in a patient with hydatid disease treated with Nemozole (albendazole)[in Russian]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2013:48-50.

- Tas A, Köklü S, Celik H. Loss of body hair as a side effect of albendazole. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:220. doi:10.1007/s00508-011-0112-y

- Pilar García-Muret M, Sitjas D, Tuneu L, et al. Telogen effluvium associated with albendazole therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:669-670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02597.x

- Ghias M, Amin B, Kutner A. Albendazole-induced anagen effluvium. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:54-56.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Albendazole functions by inhibiting microtubule dynamics and has a remarkably greater binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin than for its mammalian counterpart.

- An uncommon adverse effect of albendazole at therapeutic dosing is a dose-dependent telogen effluvium in susceptible persons, likely caused by the inherent susceptibility of follicular matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents.

- Massive albendazole overdose can cause anagen effluvium and myelosuppression similar to the effects of conventional chemotherapy.

Sweet Syndrome With Pulmonary Involvement Preceding the Development of Myelodysplastic Syndrome

To the Editor:

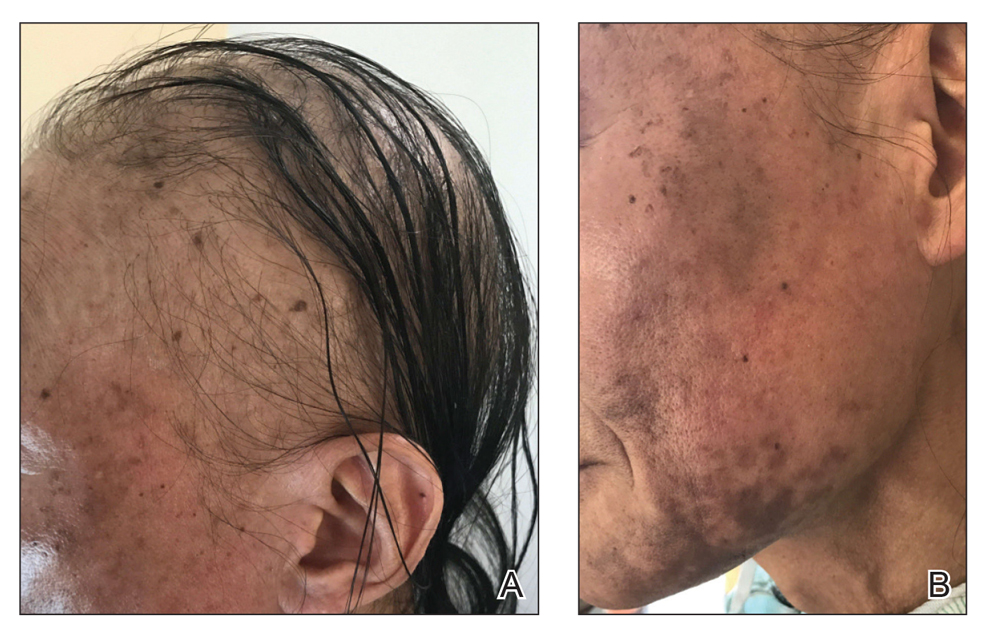

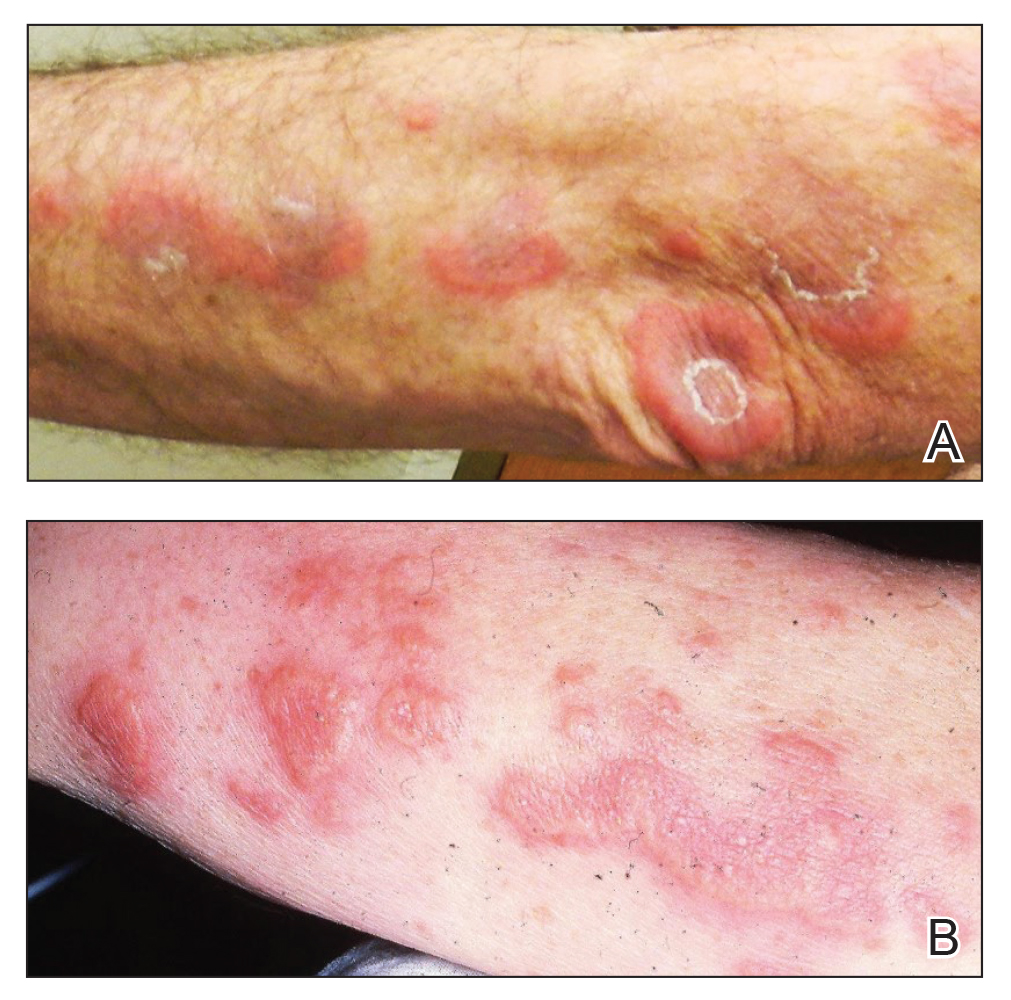

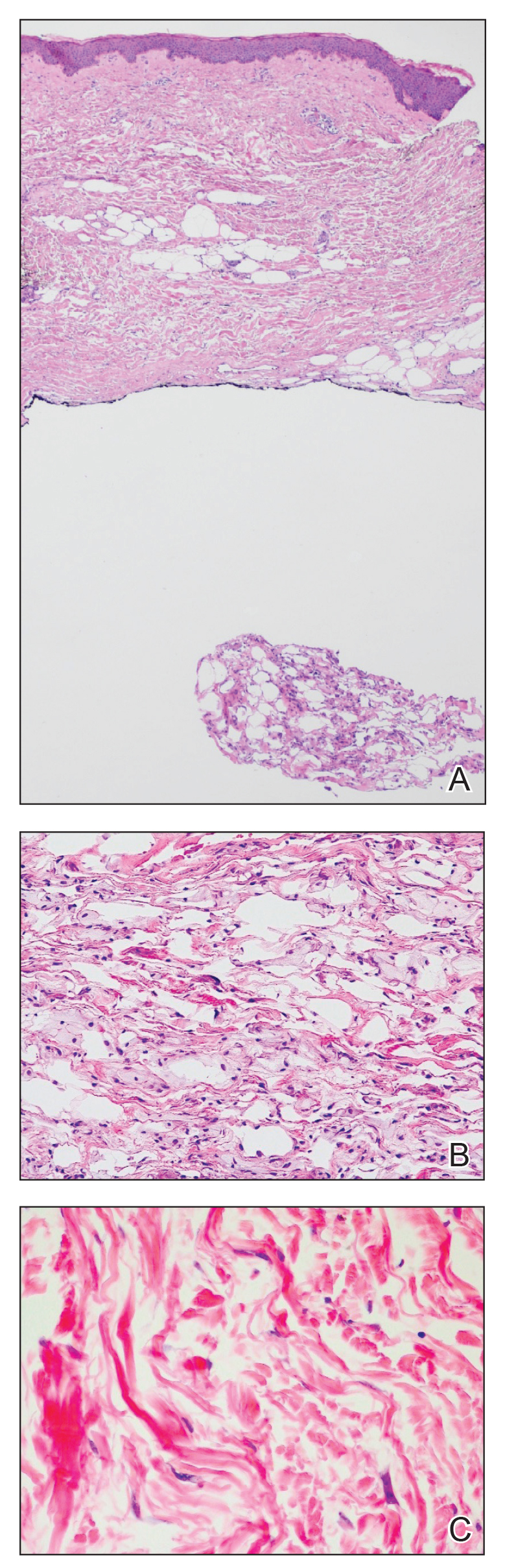

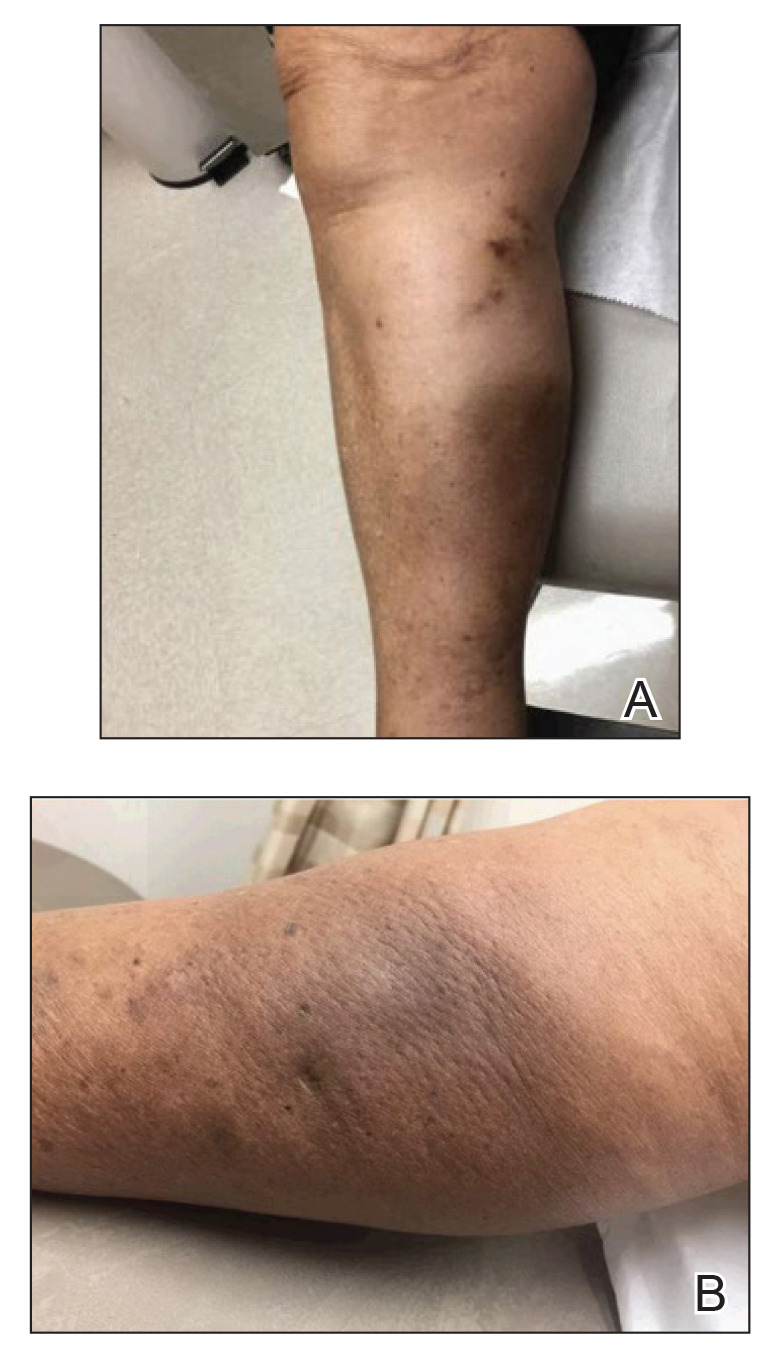

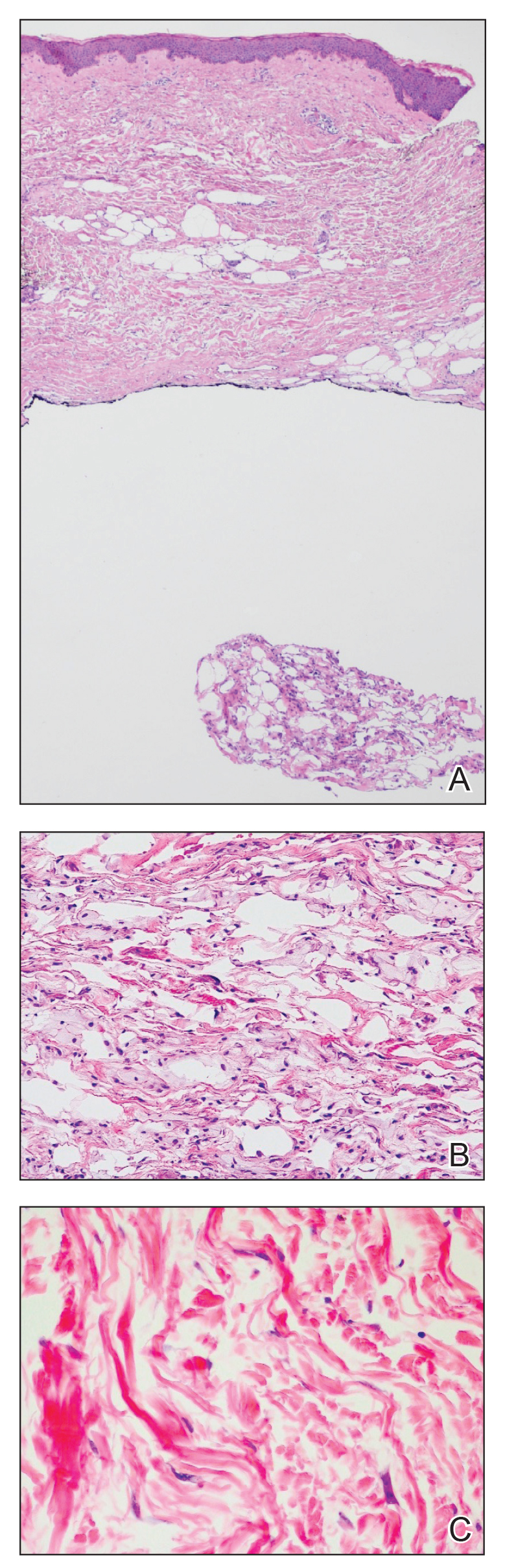

A 59-year-old man was referred to our clinic for a rash, fever, and night sweats following treatment for metastatic seminoma with cisplatin and etoposide. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk and upper and lower extremities, some with annular or arcuate configuration with trailing scale (Figure, A). A skin biopsy demonstrated mild papillary dermal edema with a mixed infiltrate of mononuclear cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, and karyorrhectic debris without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The histopathologic differential diagnosis included a histiocytoid variant of Sweet syndrome (SS), and our patient’s rapid clinical response to corticosteroids supported this diagnosis.

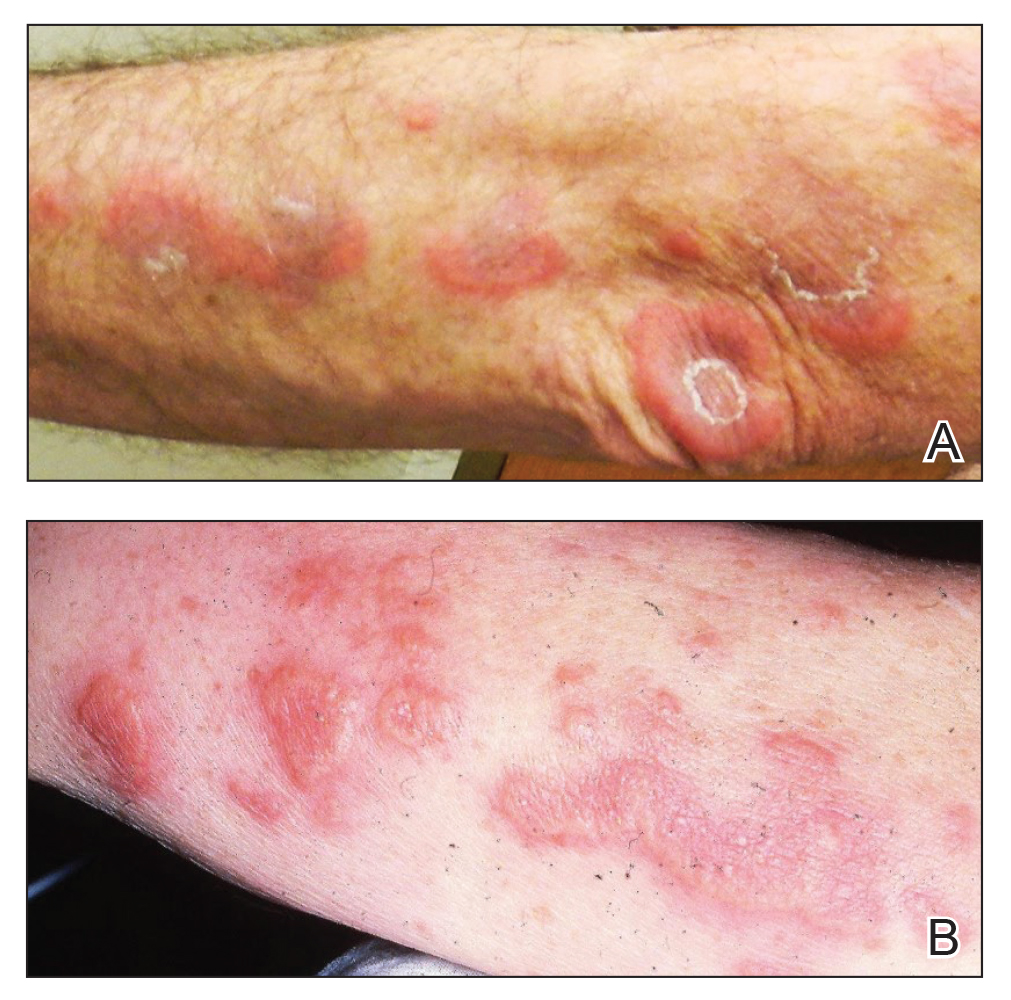

With a relapsing and remitting course over 3 years, the rash eventually evolved into more edematous papules and plaques (Figure, B), and a repeat biopsy 3 years later was consistent with classic SS. Although the patient's condition improved with prednisone, attempts to taper prednisone invariably resulted in relapse. Multiple steroid-sparing agents were trialed over the course of 3 years including dapsone and mycophenolate mofetil, both of which resulted in hypersensitivity drug eruptions. Colchicine and methotrexate were ineffective. Thalidomide strongly was considered but ultimately was avoided due to substantial existing neuropathy associated with his prior chemotherapy for metastatic seminoma.

Four years after the initial diagnosis of SS, our patient presented with dyspnea and weight loss. Computed tomography revealed a nearly confluent miliary pattern of nodularity in the lungs. A wedge biopsy demonstrated pneumonitis with intra-alveolar fibrin and neutrophils with a notable absence of granulomatous inflammation. Fungal and acid-fast bacilli staining as well as tissue cultures were negative. He had a history of Mycobacterium kansasii pulmonary infection treated 18 months prior; however, in this instance, the histopathology, negative microbial cultures, and rapid steroid responsiveness were consistent with pulmonary involvement of SS. Over the ensuing 2 years, the patient developed worsening of his chronic anemia. He was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) by bone marrow biopsy, despite having a normal bone marrow biopsy more than 3 years prior to evaluate his anemia. At this time, thalidomide was initiated at 50 mg daily leading to notable improvement in his SS symptoms; however, he developed worsening neuropathy resulting in the discontinuation of this treatment 2 months later. An investigational combination of vosaroxin and azacytidine was used to treat his MDS, resulting in normalization of blood counts and remission from SS.

Sweet syndrome may occur in the setting of undiagnosed cancer or may signal the return of a previously treated malignancy. The first description of SS associated with solid tumors was in a patient with testicular cancer,1 which prompted continuous surveillance for recurrent seminoma in our patient, though none was found. Hematologic malignancies, as well as MDS, often are associated with SS.2 In our patient, multiple atypical features linked the development of SS to the ultimate presentation of MDS. The initial finding of a histiocytoid variant has been described in a case series of 9 patients with chronic relapsing SS who eventually developed MDS with latency of up to 7 years. The histopathology in these cases evolved over time to that of classic neutrophilic SS.3 Pulmonary involvement of SS is another interesting aspect of our case. In one analysis, 18 of 34 (53%) cases with pulmonary involvement featured hematologic pathology, including myelodysplasia and acute leukemia.4

In our patient, SS preceded the clinical manifestation of MDS by 6 years. A similar phenomenon has been described in a patient with SS that preceded myelodysplasia by 30 months and was recalcitrant to numerous steroid-sparing therapies except thalidomide, despite the persistence of myelodysplasia. Tapering thalidomide, however, resulted in recurrence of SS lesions in that patient.5 In another case, resolution of myelodysplasia from azacytidine treatment was associated with remission from SS.6

Our case represents a confluence of atypical features that seem to define myelodysplasia-associated SS, including the initial presentation with a clinically atypical histiocytoid variant, chronic relapsing and remitting course, and extracutaneous involvement of the lungs. These findings should prompt surveillance for hematologic malignancy or myelodysplasia. Serial bone marrow biopsies were required to evaluate persistent anemia before the histopathologic findings of MDS became apparent in our patient. Thalidomide was an effective treatment for the cutaneous manifestations in our patient and should be considered as a steroid-sparing agent in the treatment of recalcitrant SS. Despite the discontinuation of thalidomide therapy, effective control of our patient’s myelodysplasia with chemotherapy has kept him in remission from SS for more than 7 years of follow-up, suggesting a causal relationship between these disorders.

- Shapiro L, Baraf CS, Richheimer LL. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis): report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:81-84.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Vignon-Pennamen MD, Juillard C, Rybojad M, et al. Chronic recurrent lymphocytic Sweet syndrome as a predictive marker of myelodysplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1170-1176.

- Fernandez-Bussy S, Labarca G, Cabello F, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with pulmonary involvement: case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2012;6:16-19.

- Browning CE, Dixon DE, Malone JC, et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of recalcitrant Sweet’s syndrome associated with myelodysplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 1):S135-S138.

- Martinelli S, Rigolin GM, Leo G, et al. Complete remission Sweet’s syndrome after azacytidine treatment for concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:663-667.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man was referred to our clinic for a rash, fever, and night sweats following treatment for metastatic seminoma with cisplatin and etoposide. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk and upper and lower extremities, some with annular or arcuate configuration with trailing scale (Figure, A). A skin biopsy demonstrated mild papillary dermal edema with a mixed infiltrate of mononuclear cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, and karyorrhectic debris without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The histopathologic differential diagnosis included a histiocytoid variant of Sweet syndrome (SS), and our patient’s rapid clinical response to corticosteroids supported this diagnosis.