User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Atopic Dermatitis Topical Therapies: Study of YouTube Videos as a Source of Patient Information

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (eczema) affects approximately 20% of children worldwide.1 In atopic dermatitis management, patient education is crucial for optimal outcomes.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted patient-physician interactions. To ensure safety of patients and physicians, visits may have been canceled, postponed, or conducted virtually, leaving less time for discussion and questions.3 As a consequence, patients may seek information about atopic dermatitis from alternative sources, including YouTube videos. We performed a cross-sectional study to analyze YouTube videos about topical treatments for atopic dermatitis.

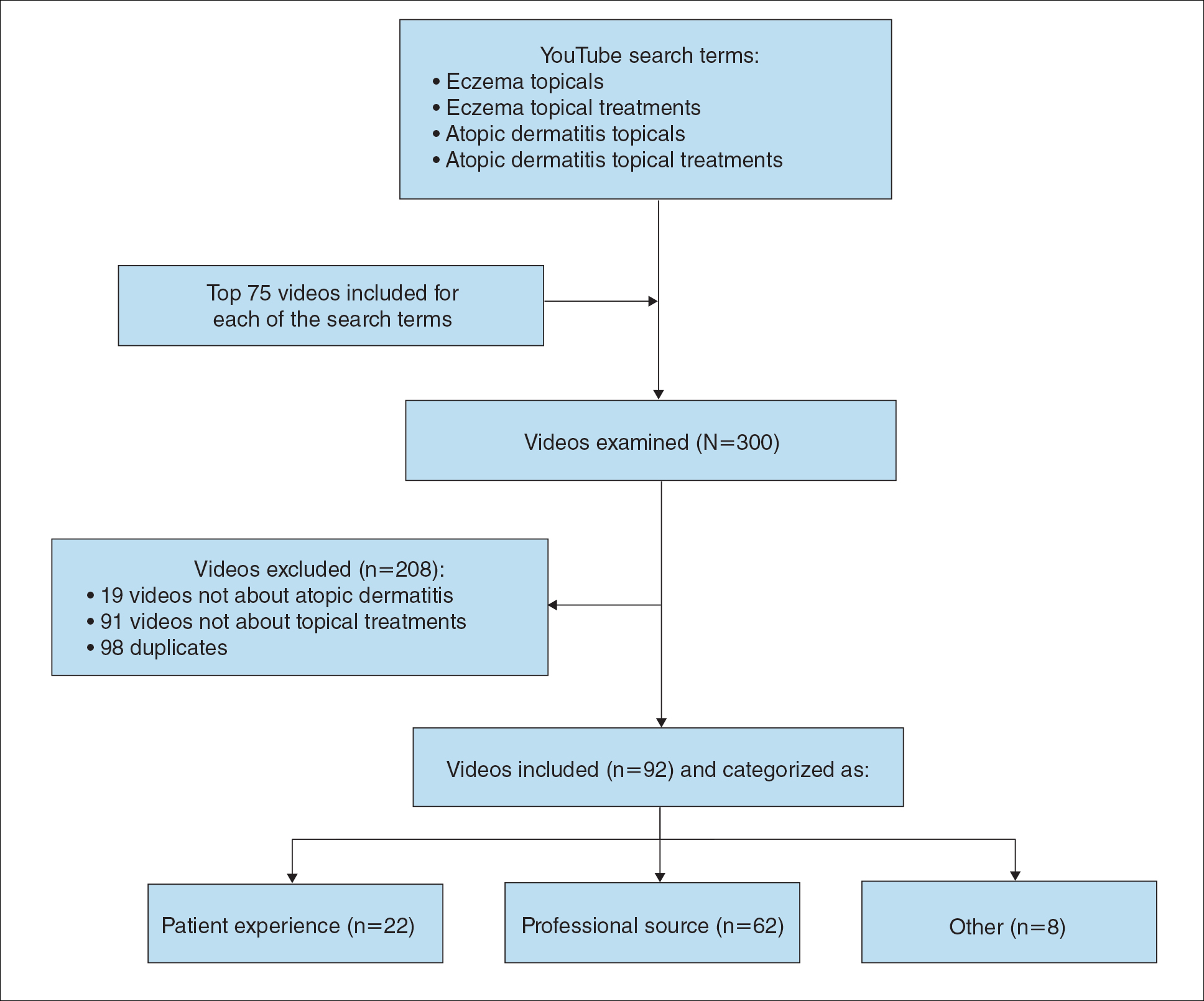

During the week of July 16, 2020, we performed 4 private browser YouTube searches with default filters using the following terms: eczema topicals, eczema topical treatments, atopic dermatitis topicals, and atopic dermatitis topical treatments. For video selection, we defined topical treatments as topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, crisaborole, emollients, wet wraps, and any prospective treatment topically administered. For each of the 4 searches, 2 researchers (A.M. and A.T.) independently examined the top 75 videos, yielding a total of 300 videos. Of them, 98 videos were duplicates, 19 videos were not about atopic dermatitis, and 91 videos were not about topical treatments, leaving a total of 92 videos for analysis (Figure 1).

For the 92 included videos, the length; upload year; number of views, likes, dislikes, and comments; interaction ratio (IR)(the sum of likes, dislikes, and comments divided by the number of views); and video content were determined. The videos were placed into mutually exclusive categories as follows: (1) patient experience, defined as a video about patient perspective; (2) professional source, defined as a video featuring a physician, physician extender, pharmacist, or scientist, or produced by a formal organization; or (3) other. The DISCERN Instrument was used for grading the reliability and quality of the 92 included videos. This instrument consists of 16 questions with the responses rated on a scale of 1 to 5.4 For analysis of DISCERN scores, patient experience and other videos were grouped together as nonprofessional source videos. A 2-sample t-test was used to compare DISCERN scores between professional source and nonprofessional source videos.

Most videos were uploaded in 2017 (n=19), 2018 (n=23), and 2019 (n=25), but 20 were uploaded in 2012-2016 and 5 were uploaded in 2020. The 92 videos had a mean length of 8 minutes and 35 seconds (range, 30 seconds to 62 minutes and 23 seconds).

Patient experience videos accounted for 23.9% (n=22) of videos. These videos discussed topical steroid withdrawal (TSW)(n=16), instructions for making emollients (n=2), and treatment successes (n=4). Professional source videos represented 67.4% (n=62) of videos. Of them, 40.3% (n=25) were physician oriented, defined as having extensive medical terminology or qualifying for continuing medical education credit. Three (4.8%) of the professional source videos were sponsored by a drug company. Other constituted the remaining 8.7% (n=8) of videos. Patient experience videos had more views (median views [interquartile range], 6865 [10,307]) and higher engagement (median IR [interquartile range], 0.038 [0.022]) than professional source videos (views: median views [interquartile range], 1052.5 [10,610.5]; engagement: median IR [interquartile range], 0.006 [0.008]).

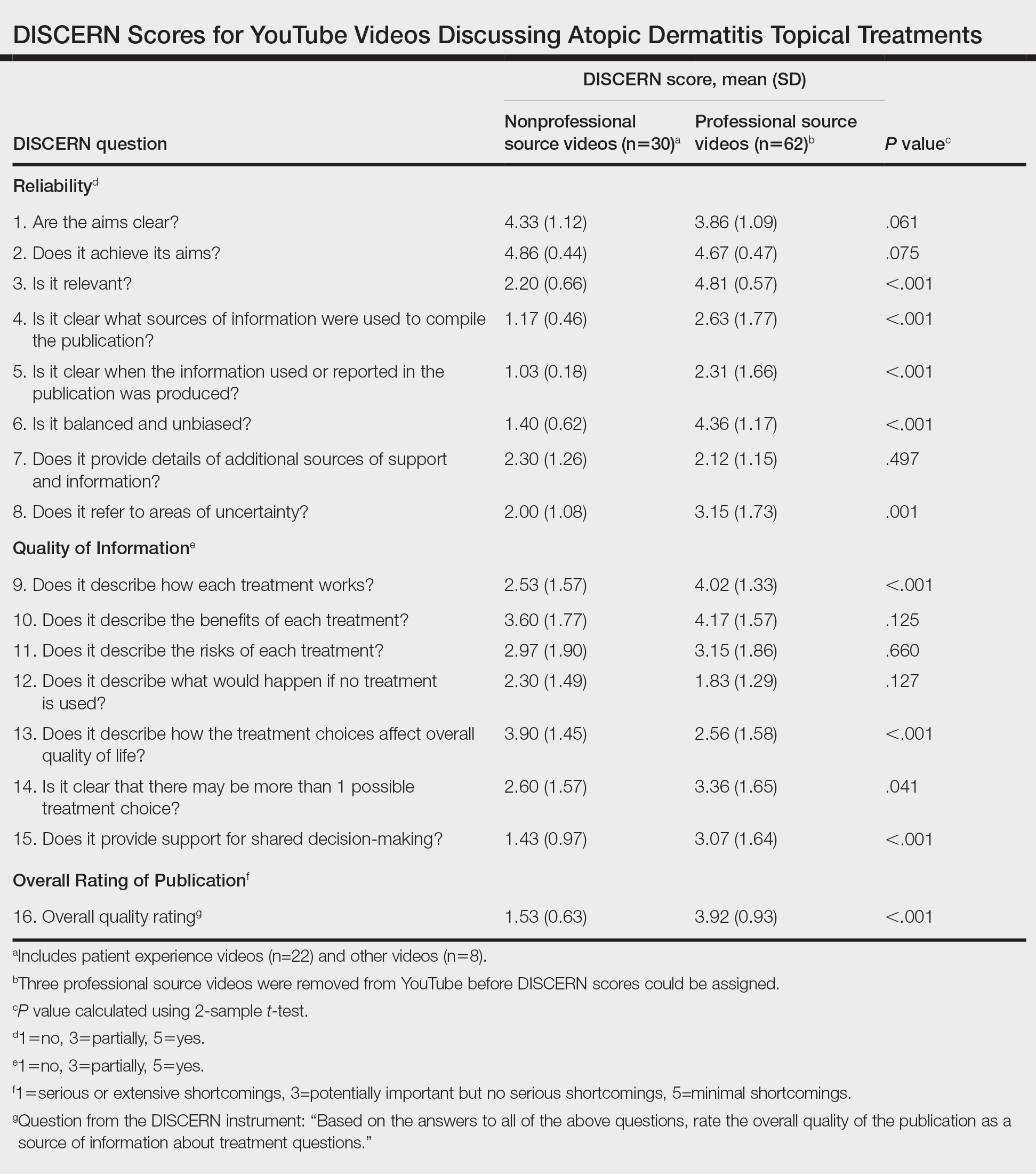

Although less popular, professional source videos had a significantly higher DISCERN overall quality rating score (question 16) compared to those categorized as nonprofessional source (3.92 vs 1.53; P<.001). In contrast, nonprofessional source videos scored significantly higher on the quality-of-life question (question 13) compared to professional source videos (3.90 vs 2.56; P<.001)(eTable). (Three professional source videos were removed from YouTube before DISCERN scores could be assigned.)

Notably, 20.7% (n=19) of the 92 videos discussed TSW, and most of them were patient experiences (n=16). Other categories included topical steroids excluding TSW (n=11), steroid phobia (n=2), topical calcineurin inhibitors (n=2), crisaborole (n=6), news broadcast (n=7), wet wraps (n=5), product advertisement (n=7), and research (n=11)(Figure 2). Interestingly, there were no videos focusing on the calcineurin inhibitor black box warning.

Similar to prior studies, our results indicate preference for patient-generated videos over videos produced by or including a professional source.5 Additionally, only 3 of 19 videos about TSW were from a professional source, increasing the potential for patient misconceptions about topical corticosteroids. Future studies should examine the educational impact of patient-generated videos as well as features that make the patient experience videos more desirable for viewing.

- Mueller SM, Hongler VNS, Jungo P, et al. Fiction, falsehoods, and few facts: cross-sectional study on the content-related quality of atopic eczema-related videos on YouTube. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e15599. doi:10.2196/15599

- Torres T, Ferreira EO, Gonçalo M, et al. Update on atopic dermatitis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:606-613. doi:10.20344/amp.11963

- Vogler SA, Lightner AL. Rethinking how we care for our patients in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107:937-939. doi:10.1002/bjs.11636

- The DISCERN Instrument. discern online. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.discern.org.uk/discern_instrument.php

- Pithadia DJ, Reynolds KA, Lee EB, et al. Dupilumab for atopic dermatitis: what are patients learning on YouTube? [published online April 16, 2020]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1755418

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (eczema) affects approximately 20% of children worldwide.1 In atopic dermatitis management, patient education is crucial for optimal outcomes.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted patient-physician interactions. To ensure safety of patients and physicians, visits may have been canceled, postponed, or conducted virtually, leaving less time for discussion and questions.3 As a consequence, patients may seek information about atopic dermatitis from alternative sources, including YouTube videos. We performed a cross-sectional study to analyze YouTube videos about topical treatments for atopic dermatitis.

During the week of July 16, 2020, we performed 4 private browser YouTube searches with default filters using the following terms: eczema topicals, eczema topical treatments, atopic dermatitis topicals, and atopic dermatitis topical treatments. For video selection, we defined topical treatments as topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, crisaborole, emollients, wet wraps, and any prospective treatment topically administered. For each of the 4 searches, 2 researchers (A.M. and A.T.) independently examined the top 75 videos, yielding a total of 300 videos. Of them, 98 videos were duplicates, 19 videos were not about atopic dermatitis, and 91 videos were not about topical treatments, leaving a total of 92 videos for analysis (Figure 1).

For the 92 included videos, the length; upload year; number of views, likes, dislikes, and comments; interaction ratio (IR)(the sum of likes, dislikes, and comments divided by the number of views); and video content were determined. The videos were placed into mutually exclusive categories as follows: (1) patient experience, defined as a video about patient perspective; (2) professional source, defined as a video featuring a physician, physician extender, pharmacist, or scientist, or produced by a formal organization; or (3) other. The DISCERN Instrument was used for grading the reliability and quality of the 92 included videos. This instrument consists of 16 questions with the responses rated on a scale of 1 to 5.4 For analysis of DISCERN scores, patient experience and other videos were grouped together as nonprofessional source videos. A 2-sample t-test was used to compare DISCERN scores between professional source and nonprofessional source videos.

Most videos were uploaded in 2017 (n=19), 2018 (n=23), and 2019 (n=25), but 20 were uploaded in 2012-2016 and 5 were uploaded in 2020. The 92 videos had a mean length of 8 minutes and 35 seconds (range, 30 seconds to 62 minutes and 23 seconds).

Patient experience videos accounted for 23.9% (n=22) of videos. These videos discussed topical steroid withdrawal (TSW)(n=16), instructions for making emollients (n=2), and treatment successes (n=4). Professional source videos represented 67.4% (n=62) of videos. Of them, 40.3% (n=25) were physician oriented, defined as having extensive medical terminology or qualifying for continuing medical education credit. Three (4.8%) of the professional source videos were sponsored by a drug company. Other constituted the remaining 8.7% (n=8) of videos. Patient experience videos had more views (median views [interquartile range], 6865 [10,307]) and higher engagement (median IR [interquartile range], 0.038 [0.022]) than professional source videos (views: median views [interquartile range], 1052.5 [10,610.5]; engagement: median IR [interquartile range], 0.006 [0.008]).

Although less popular, professional source videos had a significantly higher DISCERN overall quality rating score (question 16) compared to those categorized as nonprofessional source (3.92 vs 1.53; P<.001). In contrast, nonprofessional source videos scored significantly higher on the quality-of-life question (question 13) compared to professional source videos (3.90 vs 2.56; P<.001)(eTable). (Three professional source videos were removed from YouTube before DISCERN scores could be assigned.)

Notably, 20.7% (n=19) of the 92 videos discussed TSW, and most of them were patient experiences (n=16). Other categories included topical steroids excluding TSW (n=11), steroid phobia (n=2), topical calcineurin inhibitors (n=2), crisaborole (n=6), news broadcast (n=7), wet wraps (n=5), product advertisement (n=7), and research (n=11)(Figure 2). Interestingly, there were no videos focusing on the calcineurin inhibitor black box warning.

Similar to prior studies, our results indicate preference for patient-generated videos over videos produced by or including a professional source.5 Additionally, only 3 of 19 videos about TSW were from a professional source, increasing the potential for patient misconceptions about topical corticosteroids. Future studies should examine the educational impact of patient-generated videos as well as features that make the patient experience videos more desirable for viewing.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (eczema) affects approximately 20% of children worldwide.1 In atopic dermatitis management, patient education is crucial for optimal outcomes.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted patient-physician interactions. To ensure safety of patients and physicians, visits may have been canceled, postponed, or conducted virtually, leaving less time for discussion and questions.3 As a consequence, patients may seek information about atopic dermatitis from alternative sources, including YouTube videos. We performed a cross-sectional study to analyze YouTube videos about topical treatments for atopic dermatitis.

During the week of July 16, 2020, we performed 4 private browser YouTube searches with default filters using the following terms: eczema topicals, eczema topical treatments, atopic dermatitis topicals, and atopic dermatitis topical treatments. For video selection, we defined topical treatments as topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, crisaborole, emollients, wet wraps, and any prospective treatment topically administered. For each of the 4 searches, 2 researchers (A.M. and A.T.) independently examined the top 75 videos, yielding a total of 300 videos. Of them, 98 videos were duplicates, 19 videos were not about atopic dermatitis, and 91 videos were not about topical treatments, leaving a total of 92 videos for analysis (Figure 1).

For the 92 included videos, the length; upload year; number of views, likes, dislikes, and comments; interaction ratio (IR)(the sum of likes, dislikes, and comments divided by the number of views); and video content were determined. The videos were placed into mutually exclusive categories as follows: (1) patient experience, defined as a video about patient perspective; (2) professional source, defined as a video featuring a physician, physician extender, pharmacist, or scientist, or produced by a formal organization; or (3) other. The DISCERN Instrument was used for grading the reliability and quality of the 92 included videos. This instrument consists of 16 questions with the responses rated on a scale of 1 to 5.4 For analysis of DISCERN scores, patient experience and other videos were grouped together as nonprofessional source videos. A 2-sample t-test was used to compare DISCERN scores between professional source and nonprofessional source videos.

Most videos were uploaded in 2017 (n=19), 2018 (n=23), and 2019 (n=25), but 20 were uploaded in 2012-2016 and 5 were uploaded in 2020. The 92 videos had a mean length of 8 minutes and 35 seconds (range, 30 seconds to 62 minutes and 23 seconds).

Patient experience videos accounted for 23.9% (n=22) of videos. These videos discussed topical steroid withdrawal (TSW)(n=16), instructions for making emollients (n=2), and treatment successes (n=4). Professional source videos represented 67.4% (n=62) of videos. Of them, 40.3% (n=25) were physician oriented, defined as having extensive medical terminology or qualifying for continuing medical education credit. Three (4.8%) of the professional source videos were sponsored by a drug company. Other constituted the remaining 8.7% (n=8) of videos. Patient experience videos had more views (median views [interquartile range], 6865 [10,307]) and higher engagement (median IR [interquartile range], 0.038 [0.022]) than professional source videos (views: median views [interquartile range], 1052.5 [10,610.5]; engagement: median IR [interquartile range], 0.006 [0.008]).

Although less popular, professional source videos had a significantly higher DISCERN overall quality rating score (question 16) compared to those categorized as nonprofessional source (3.92 vs 1.53; P<.001). In contrast, nonprofessional source videos scored significantly higher on the quality-of-life question (question 13) compared to professional source videos (3.90 vs 2.56; P<.001)(eTable). (Three professional source videos were removed from YouTube before DISCERN scores could be assigned.)

Notably, 20.7% (n=19) of the 92 videos discussed TSW, and most of them were patient experiences (n=16). Other categories included topical steroids excluding TSW (n=11), steroid phobia (n=2), topical calcineurin inhibitors (n=2), crisaborole (n=6), news broadcast (n=7), wet wraps (n=5), product advertisement (n=7), and research (n=11)(Figure 2). Interestingly, there were no videos focusing on the calcineurin inhibitor black box warning.

Similar to prior studies, our results indicate preference for patient-generated videos over videos produced by or including a professional source.5 Additionally, only 3 of 19 videos about TSW were from a professional source, increasing the potential for patient misconceptions about topical corticosteroids. Future studies should examine the educational impact of patient-generated videos as well as features that make the patient experience videos more desirable for viewing.

- Mueller SM, Hongler VNS, Jungo P, et al. Fiction, falsehoods, and few facts: cross-sectional study on the content-related quality of atopic eczema-related videos on YouTube. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e15599. doi:10.2196/15599

- Torres T, Ferreira EO, Gonçalo M, et al. Update on atopic dermatitis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:606-613. doi:10.20344/amp.11963

- Vogler SA, Lightner AL. Rethinking how we care for our patients in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107:937-939. doi:10.1002/bjs.11636

- The DISCERN Instrument. discern online. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.discern.org.uk/discern_instrument.php

- Pithadia DJ, Reynolds KA, Lee EB, et al. Dupilumab for atopic dermatitis: what are patients learning on YouTube? [published online April 16, 2020]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1755418

- Mueller SM, Hongler VNS, Jungo P, et al. Fiction, falsehoods, and few facts: cross-sectional study on the content-related quality of atopic eczema-related videos on YouTube. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e15599. doi:10.2196/15599

- Torres T, Ferreira EO, Gonçalo M, et al. Update on atopic dermatitis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:606-613. doi:10.20344/amp.11963

- Vogler SA, Lightner AL. Rethinking how we care for our patients in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107:937-939. doi:10.1002/bjs.11636

- The DISCERN Instrument. discern online. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.discern.org.uk/discern_instrument.php

- Pithadia DJ, Reynolds KA, Lee EB, et al. Dupilumab for atopic dermatitis: what are patients learning on YouTube? [published online April 16, 2020]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1755418

Practice Points

- YouTube is a readily accessible resource for educating patients about topical treatments for atopic dermatitis.

- Although professional source videos comprised a larger percentage of the videos included within our study, patient experience videos had a higher number of views and engagement.

- Twenty-one percent (19/92) of the videos examined in our study discussed topical steroid withdrawal, and the majority of them were patient experience videos.

Plant Dermatitis: More Than Just Poison Ivy

Plants can contribute to a variety of dermatoses. The Toxicodendron genus, which includes poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, is a well-known and common cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), but many other plants can cause direct or airborne contact dermatitis, especially in gardeners, florists, and farmers. This article provides an overview of different plant-related dermatoses and culprit plants as well as how these dermatoses should be diagnosed and treated.

Epidemiology

Plant dermatoses affect more than 50 million individuals each year.1,2 In the United States, the Toxicodendron genus causes ACD in more than 70% of exposed individuals, leading to medical visits.3 An urgent care visit for a plant-related dermatitis is estimated to cost $168, while an emergency department visit can cost 3 times as much.4 Although less common, Compositae plants are another important culprit of plant dermatitis, particularly in gardeners, florists, and farmers. Data from the 2017-2018 North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series (N=4947) showed sesquiterpene lactones and Compositae to be positive in 0.5% of patch-tested patients.5

Plant Dermatitis Classifications

Plant dermatitis can be classified into 5 main categories: ACD, mechanical irritant contact dermatitis, chemical irritant contact dermatitis, light-mediated dermatitis, and pseudophytodermatitis.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immune-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The common molecular allergens in plants include phenols, α-methylene-γ-butyrolactones, quinones, terpenes, disulfides, isothiocyanates, and polyacetylenic derivatives.6

Plant contact dermatitis due to mechanical and chemical irritants is precipitated by multiple mechanisms, including disruption of the epidermal barrier and subsequent cytokine release from keratinocytes.7 Nonimmunologic contact urticaria from plants is thought to be a type of irritant reaction precipitated by mechanical or chemical trauma.8

Light-mediated dermatitis includes phytophotodermatitis and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Phytophotodermatitis is a phototoxic reaction triggered by exposure to both plant-derived furanocoumarin and UVA light.9 By contrast, photoallergic contact dermatitis is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction from prior sensitization to a light-activated antigen.10

Pseudophytodermatitis, as its name implies, is not truly mediated by an allergen or irritant intrinsic to the plant but rather by dyes, waxes, insecticides, or arthropods that inhabit the plant or are secondarily applied.6

Common Plant Allergens

Anacardiaceae Family

Most of the allergenic plants within the Anacardiaceae family belong to the Toxicodendron genus, which encompasses poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens,Toxicodendron quercifolium, Toxicodendron diversiloum), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). Poison ivy is the celebrity of the Anacardiaceae family and contributes to most cases of plant-related ACD. It is found in every state in the continental United States. Poison oak is another common culprit found in the western and southeastern United States.11 Plants within the Anacardiaceae family contain an oleoresin called urushiol, which is the primary sensitizing substance. Although poison ivy and poison oak grow well in full sun to partial shade, poison sumac typically is found in damp swampy areas east of the Rocky Mountains. Most cases of ACD related to Anacardiaceae species are due to direct contact with urushiol from a Toxicodendron plant, but burning of brush containing Toxicodendron can cause airborne exposure when urushiol oil is carried by smoke particles.12 Sensitization to Toxicodendron can cause ACD to other Anacardiaceae species such as the Japanese lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), mango tree (Mangifera indica), cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale), and Indian marking nut tree (Semecarpus anacardium).6 Cross-reactions to components of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba) also are possible.

Toxicodendron plants can be more easily identified and avoided with knowledge of their characteristic leaf patterns. The most dependable way to identify poison ivy and poison oak species is to look for plants with 3 leaves, giving rise to the common saying, “Leaves of three, leave them be.” Poison sumac plants have groups of 7 to 13 leaves arranged as pairs along a central rib. Another helpful finding is a black deposit that Toxicodendron species leave behind following trauma to the leaves. Urushiol oxidizes when exposed to air and turns into a black deposit that can be seen on damaged leaves themselves or can be demonstrated in a black spot test to verify if a plant is a Toxicodendron species. The test is performed by gathering (carefully, without direct contact) a few leaves in a paper towel and crushing them to release sap. Within minutes, the sap will turn black if the plant is indeed a Toxicodendron species.13Pruritic, edematous, erythematous papules, plaques, and eventual vesicles in a linear distribution are suspicious for Toxicodendron exposure. Although your pet will not develop Toxicodendron ACD, oleoresin-contaminated pets can transfer the oils to their owners after coming into contact with these plants. Toxicodendron dermatitis also can be acquired from oleoresin-contaminated fomites such as clothing and shoes worn in the garden or when hiking. Toxicodendron dermatitis can appear at different sites on the body at different times depending on the amount of oleoresin exposure as well as epidermal thickness. For example, the oleoresin can be transferred from the hands to body areas with a thinner stratum corneum (eg, genitalia) and cause subsequent dermatitis.1

Compositae Family

The Compositae family (also known as Asteraceae) is a large plant family with more than 20,000 species, including numerous weeds, wildflowers, and vegetables. The flowers, leaves, stems, and pollens of the Compositae family are coated by cyclic esters called sesquiterpene lactones. Mitchell and Dupuis14 showed that sesquiterpene lactones are the allergens responsible for ACD to various Compositae plants, including ragweed (Ambrosia), sneezeweed (Helenium), and chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum). Common Compositae vegetables such as lettuce (Lactuca sativa) have been reported to cause ACD in chefs, grocery store produce handlers, gardeners, and even owners of lettuce-eating pet guinea pigs and turtles.15 Similarly, artichokes (Cynara scolymus) can cause ACD in gardeners.16 Exposure to Compositae species also has been implicated in photoallergic reactions, and studies have demonstrated that some patients with chronic actinic dermatitis also have positive patch test reactions to Compositae species and/or sesquiterpene lactones.17,18

In addition to direct contact with Compositae plants, airborne exposure to sesquiterpene lactones can cause ACD.14 The pattern of airborne contact dermatitis typically involves exposed areas such as the eyelids, central face, and/or neck. The beak sign also can be a clue to airborne contact dermatitis, which involves dermatitis of the face that spares the nasal tip and/or nasal ridge. It is thought that the beak sign may result from increased sebaceous gland concentration on the nose, which prevents penetration of allergens and irritants.19 Unlike photoallergic contact dermatitis, which also can involve the face, airborne ACD frequently involves photoprotected areas such as the submandibular chin and the upper lip. Davies and Kersey20 reported the case of a groundsman who was cutting grass with dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) and was found to have associated airborne ACD of the face, neck, and forearms due to Compositae allergy. In a different setting, the aromas of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) have been reported to cause airborne ACD in a tea drinker.21 Paulsen22 found that ingestion of chamomile tea can induce systemic ACD in sensitized individuals.

Alstroemeriaceae, Liliaceae, and Primulaceae

Florists are exposed to many plant species and have a high prevalence of ACD. Thiboutot et al23 found that 15 of 57 (26%) floral workers experienced hand dermatitis that cleared with time away from work. The Peruvian lily (Alstroemeria, Alstroemeriaceae family), which contains tuliposide A, was found to be the leading cause of sensitization.23 Tulips (Tulipa, Liliaceae family), as the flower name suggests, also contain tuliposide A, which along with mechanical irritation from the course tecta fibers on the bulbs lead to a dermatitis known as tulip fingers.24,25 Poison primrose (Primula obconica, Primulaceae family), cultivated for its highly colorful flowers, contains the contact allergen primin.6 A common clinical presentation of ACD for any of these culprit flowers is localized dermatitis of the thumb and index finger in a florist or gardener.

Plants That Cause Irritant Reactions

Cactuses

Although the long spines of the Cactaceae family of cactuses is a warning for passersby, it is the small and nearly invisible barbed hairs (glochids) that inflict a more dramatic cutaneous reaction. The prickly pear cactus (Opuntia species) is a good example of such a plant, as its glochids cause mechanical irritation but also can become embedded in the skin and result in subcutaneous granulomas known as sabra dermatitis.26

Stinging Nettle

The dermatologic term urticaria owes its namesake to the stinging nettle plant, which comes from the family Urticaceae. The stinging nettle has small hairs on its leaves, referred to as stinging trichomes, which have needlelike tips that pierce the skin and inject a mix of histamine, formic acid, and acetylcholine, causing a pruritic dermatitis that may last up to 12 hours.27 The plant is found worldwide and is a common weed in North America.

Phytophotodermatitis

Lemons and limes (Rutaceae family) are common culprits of phytophotodermatitis, often causing what is known as a margarita burn after outdoor consumption or preparation of this tasty citrus beverage.28 An accidental spray of lime juice on the skin while adding it to a beer, guacamole, salsa, or any other food or beverage also can cause phytophotodermatitis.29-31 Although the juice of lemons and limes contains psoralens, the rind can contain a 6- to 186-fold increased concentration.32 Psoralen is the photoactive agent in Rutaceae plants that intercalates in double-stranded DNA and promotes intrastrand cross-links when exposed to UVA light, which ultimately leads to dermatitis.9 Phytophotodermatitis commonly causes erythema, edema, and painful bullae on sun-exposed areas and classically heals with hyperpigmentation.

Pseudophytodermatitis can occur in grain farmers and harvesters who handle wheat and/or barley and incidentally come in contact with insects and chemicals on the plant material. Pseudophytodermatitis from mites in the wheat and/or barley plant can occur at harvest time when contact with the plant material is high. Insects such as the North American itch mite (Pediculoides ventricosus) can cause petechiae, wheals, and pustules. In addition, insecticides such as malathion and arsenical sprays that are applied to plant leaves can cause pseudophytodermatitis, which may be initially diagnosed as dermatitis to the plant itself.6

Patch Testing to Plants

When a patient presents with recurrent or persistent dermatitis and a plant contact allergen is suspected, patch testing is indicated. Most comprehensive patch test series contain various plant allergens, such as sesquiterpene lactones, Compositae mix, and limonene hydroperoxides, and patch testing to a specialized plant series may be necessary. Poison ivy/oak/sumac allergens typically are not included in patch test series because of the high prevalence of allergic reactions to these chemicals and the likelihood of sensitization when patch testing with urushiol. Compositae contact sensitization can be difficult to diagnose because neither sesquiterpene lactone mix 0.1% nor parthenolide 0.1% are sensitive enough to pick up all Compositae allergies.33,34 Paulsen and Andersen34 proposed that if Compositae sensitization is suspected, testing should include sesquiterpene lactone, parthenolide, and Compositae mix II 2.5%, as well as other potential Compositae allergens based on the patient’s history.34

Because plants can have geographic variability and contain potentially unknown allergens,35 testing to plant components may increase the diagnostic yield of patch testing. Dividing the plant into component parts (ie, stem, bulb, leaf, flower) is helpful, as different components have different allergen concentrations. It is important to consult expert resources before proceeding with plant component patch testing because irritant reactions are frequent and may confound the testing.36

Prevention and Treatment

For all plant dermatoses, the mainstay of prevention is to avoid contact with the offending plant material. Gloves can be an important protective tool for plant dermatitis prevention; the correct material depends on the plant species being handled. Rubber gloves should not be worn to protect against Toxicodendron plants since the catechols in urushiol are soluble in rubber; vinyl gloves should be worn instead.6 Marks37 found that tuliposide A, the allergen in the Peruvian lily (Alstroemeria), penetrates both vinyl and latex gloves; it does not penetrate nitrile gloves. If exposed, the risk of dermatitis can be decreased if the allergen is washed away with soap and water as soon as possible. Some allergens such as Toxicodendron are absorbed quickly and need to be washed off within 10 minutes of exposure.6 Importantly, exposed gardening gloves may continue to perpetuate ACD if the allergen is not also washed off the gloves themselves.

For light-mediated dermatoses, sun avoidance or use of an effective sunscreen can reduce symptoms in an individual who has already been exposed.10 UVA light activates psoralen-mediated dermatitis but not until 30 to 120 minutes after absorption into the skin.38

Barrier creams are thought to be protective against plant ACD through a variety of mechanisms. The cream itself is meant to reduce skin contact to an allergen or irritant. Additionally, barrier creams contain active ingredients such as silicone, hydrocarbons, and aluminum chlorohydrate, which are thought to trap or transform offending agents before contacting the skin. When contact with a Toxicodendron species is anticipated, Marks et al39 found that dermatitis was absent or significantly reduced when 144 patients were pretreated with quaternium-18 bentonite lotion 5% (P<.0001).

Although allergen avoidance and use of gloves and barrier creams are the mainstays of preventing plant dermatoses, treatment often is required to control postexposure symptoms. For all plant dermatoses, topical corticosteroids can be used to reduce inflammation and pruritus. In some cases, systemic steroids may be necessary. To prevent rebound of dermatitis, patients often require a 3-week or longer course of oral steroids to quell the reaction, particularly if the dermatitis is vigorous or an id reaction is present.40 Antihistamines and cold compresses also can provide symptomatic relief.

Final Interpretation

Plants can cause a variety of dermatoses. Although Toxicodendron plants are the most frequent cause of ACD, it is important to keep in mind that florists, gardeners, and farmers are exposed to a large variety of allergens, irritants, and phototoxic agents that cause dermatoses as well. Confirmation of plant-induced ACD involves patch testing against suspected species. Prevention involves use of appropriate barriers and avoidance of implicated plants. Treatment includes topical steroids, antihistamines, and prednisone.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128.

- Pariser D, Ceilley R, Lefkovits A, et al. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm Insights. 2003;4:26-28.

- Wolff K, Johnson R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Education; 2009.

- Zomorodi N, Butt M, Maczuga S, et al. Cost and diagnostic characteristics of Toxicodendron dermatitis in the USA: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:772-773.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123.

- Fowler JF, Zirwas MJ. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 7th ed. Contact Dermatitis Institute; 2019.

- Smith HR, Basketter DA, McFadden JP. Irritant dermatitis, irritancy and its role in allergic contact dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:138-146.

- Wakelin SH. Contact urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:132-136.

- Ellis CR, Elston DM. Psoralen-induced phytophotodermatitis. Dermatitis. 2021;32:140-143.

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Poisonous plants. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 1, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/plants/geographic.html

- Schloemer JA, Zirwas MJ, Burkhart CG. Airborne contact dermatitis: common causes in the USA. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:271-274.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Mitchell J, Dupuis G. Allergic contact dermatitis from sesquiterpenoids of the Compositae family of plants. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:139-150.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Lettuce contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:67-75.

- Samaran Q, Clark E, Dereure O, et al. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis caused by artichoke. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:395-397.

- Du H, Ross JS, Norris PG, et al. Contact and photocontact sensitization in chronic actinic dermatitis: sesquiterpene lactone mix is an important allergen. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:543-547.

- Wrangsjo K, Marie Ros A, Walhberg JE. Contact allergy to Compositae plants in patients with summer-exacerbated dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:148-154.

- Staser K, Ezra N, Sheehan MP, et al. The beak sign: a clinical clue to airborne contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2014;25:97-98.

- Davies M, Kersey J. Contact allergy to yarrow and dandelion. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:256-257.

- Anzai A, Vázquez Herrera NE, Tosti A. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis caused by chamomile tea. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72:254-255.

- Paulsen E. Systemic allergic dermatitis caused by sesquiterpene lactones. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:1-10.

- Thiboutot DM, Hamory BH, Marks JG. Dermatoses among floral shop workers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:54-58.

- Hjorth N, Wilkinson DS. Contact dermatitis IV. tulip fingers, hyacinth itch and lily rash. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:696-698.

- Guin JD, Franks H. Fingertip dermatitis in a retail florist. Cutis. 2001;67:328-330.

- Magro C, Lipner S. Sabra dermatitis: combined features of delayed hypersensitivity and foreign body reaction to implanted glochidia. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt2157f9g0.

- Cummings AJ, Olsen M. Mechanism of action of stinging nettles. Wilderness Environ Med. 2011;22:136-139.

- Maniam G, Light KML, Wilson J. Margarita burn: recognition and treatment of phytophotodermatitis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:398-401.

- Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

- Kung AC, Stephens MB, Darling T. Phytophotodermatitis: bulla formation and hyperpigmentation during spring break. Mil Med. 2009;174:657-661.

- Smith LG. Phytophotodermatitis. Images Emerg Med. 2017;1:146-147.

- Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

- Green C, Ferguson J. Sesquiterpene lactone mix is not an adequate screen for Compositae allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:151-153.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Screening for Compositae contact sensitization with sesquiterpene lactones and Compositae mix 2.5% pet. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:368-373.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Patch testing with constituents of Compositae mixes. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:241-246.

- Frosch PJ, Geier J, Uter W, et al. Patch testing with the patients’ own products. Contact Dermatitis. 2011:929-941.

- Marks JG. Allergic contact dermatitis to Alstroemeria. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:914-916.

- Moreau JF, English JC, Gehris RP. Phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27:93-94.

- Marks JG, Fowler JF, Sherertz EF, et al. Prevention of poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis by quaternium-18 bentonite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:212-216.

- Craig K, Meadows SE. What is the best duration of steroid therapy for contact dermatitis (rhus)? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:166-167.

Plants can contribute to a variety of dermatoses. The Toxicodendron genus, which includes poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, is a well-known and common cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), but many other plants can cause direct or airborne contact dermatitis, especially in gardeners, florists, and farmers. This article provides an overview of different plant-related dermatoses and culprit plants as well as how these dermatoses should be diagnosed and treated.

Epidemiology

Plant dermatoses affect more than 50 million individuals each year.1,2 In the United States, the Toxicodendron genus causes ACD in more than 70% of exposed individuals, leading to medical visits.3 An urgent care visit for a plant-related dermatitis is estimated to cost $168, while an emergency department visit can cost 3 times as much.4 Although less common, Compositae plants are another important culprit of plant dermatitis, particularly in gardeners, florists, and farmers. Data from the 2017-2018 North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series (N=4947) showed sesquiterpene lactones and Compositae to be positive in 0.5% of patch-tested patients.5

Plant Dermatitis Classifications

Plant dermatitis can be classified into 5 main categories: ACD, mechanical irritant contact dermatitis, chemical irritant contact dermatitis, light-mediated dermatitis, and pseudophytodermatitis.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immune-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The common molecular allergens in plants include phenols, α-methylene-γ-butyrolactones, quinones, terpenes, disulfides, isothiocyanates, and polyacetylenic derivatives.6

Plant contact dermatitis due to mechanical and chemical irritants is precipitated by multiple mechanisms, including disruption of the epidermal barrier and subsequent cytokine release from keratinocytes.7 Nonimmunologic contact urticaria from plants is thought to be a type of irritant reaction precipitated by mechanical or chemical trauma.8

Light-mediated dermatitis includes phytophotodermatitis and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Phytophotodermatitis is a phototoxic reaction triggered by exposure to both plant-derived furanocoumarin and UVA light.9 By contrast, photoallergic contact dermatitis is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction from prior sensitization to a light-activated antigen.10

Pseudophytodermatitis, as its name implies, is not truly mediated by an allergen or irritant intrinsic to the plant but rather by dyes, waxes, insecticides, or arthropods that inhabit the plant or are secondarily applied.6

Common Plant Allergens

Anacardiaceae Family

Most of the allergenic plants within the Anacardiaceae family belong to the Toxicodendron genus, which encompasses poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens,Toxicodendron quercifolium, Toxicodendron diversiloum), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). Poison ivy is the celebrity of the Anacardiaceae family and contributes to most cases of plant-related ACD. It is found in every state in the continental United States. Poison oak is another common culprit found in the western and southeastern United States.11 Plants within the Anacardiaceae family contain an oleoresin called urushiol, which is the primary sensitizing substance. Although poison ivy and poison oak grow well in full sun to partial shade, poison sumac typically is found in damp swampy areas east of the Rocky Mountains. Most cases of ACD related to Anacardiaceae species are due to direct contact with urushiol from a Toxicodendron plant, but burning of brush containing Toxicodendron can cause airborne exposure when urushiol oil is carried by smoke particles.12 Sensitization to Toxicodendron can cause ACD to other Anacardiaceae species such as the Japanese lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), mango tree (Mangifera indica), cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale), and Indian marking nut tree (Semecarpus anacardium).6 Cross-reactions to components of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba) also are possible.

Toxicodendron plants can be more easily identified and avoided with knowledge of their characteristic leaf patterns. The most dependable way to identify poison ivy and poison oak species is to look for plants with 3 leaves, giving rise to the common saying, “Leaves of three, leave them be.” Poison sumac plants have groups of 7 to 13 leaves arranged as pairs along a central rib. Another helpful finding is a black deposit that Toxicodendron species leave behind following trauma to the leaves. Urushiol oxidizes when exposed to air and turns into a black deposit that can be seen on damaged leaves themselves or can be demonstrated in a black spot test to verify if a plant is a Toxicodendron species. The test is performed by gathering (carefully, without direct contact) a few leaves in a paper towel and crushing them to release sap. Within minutes, the sap will turn black if the plant is indeed a Toxicodendron species.13Pruritic, edematous, erythematous papules, plaques, and eventual vesicles in a linear distribution are suspicious for Toxicodendron exposure. Although your pet will not develop Toxicodendron ACD, oleoresin-contaminated pets can transfer the oils to their owners after coming into contact with these plants. Toxicodendron dermatitis also can be acquired from oleoresin-contaminated fomites such as clothing and shoes worn in the garden or when hiking. Toxicodendron dermatitis can appear at different sites on the body at different times depending on the amount of oleoresin exposure as well as epidermal thickness. For example, the oleoresin can be transferred from the hands to body areas with a thinner stratum corneum (eg, genitalia) and cause subsequent dermatitis.1

Compositae Family

The Compositae family (also known as Asteraceae) is a large plant family with more than 20,000 species, including numerous weeds, wildflowers, and vegetables. The flowers, leaves, stems, and pollens of the Compositae family are coated by cyclic esters called sesquiterpene lactones. Mitchell and Dupuis14 showed that sesquiterpene lactones are the allergens responsible for ACD to various Compositae plants, including ragweed (Ambrosia), sneezeweed (Helenium), and chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum). Common Compositae vegetables such as lettuce (Lactuca sativa) have been reported to cause ACD in chefs, grocery store produce handlers, gardeners, and even owners of lettuce-eating pet guinea pigs and turtles.15 Similarly, artichokes (Cynara scolymus) can cause ACD in gardeners.16 Exposure to Compositae species also has been implicated in photoallergic reactions, and studies have demonstrated that some patients with chronic actinic dermatitis also have positive patch test reactions to Compositae species and/or sesquiterpene lactones.17,18

In addition to direct contact with Compositae plants, airborne exposure to sesquiterpene lactones can cause ACD.14 The pattern of airborne contact dermatitis typically involves exposed areas such as the eyelids, central face, and/or neck. The beak sign also can be a clue to airborne contact dermatitis, which involves dermatitis of the face that spares the nasal tip and/or nasal ridge. It is thought that the beak sign may result from increased sebaceous gland concentration on the nose, which prevents penetration of allergens and irritants.19 Unlike photoallergic contact dermatitis, which also can involve the face, airborne ACD frequently involves photoprotected areas such as the submandibular chin and the upper lip. Davies and Kersey20 reported the case of a groundsman who was cutting grass with dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) and was found to have associated airborne ACD of the face, neck, and forearms due to Compositae allergy. In a different setting, the aromas of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) have been reported to cause airborne ACD in a tea drinker.21 Paulsen22 found that ingestion of chamomile tea can induce systemic ACD in sensitized individuals.

Alstroemeriaceae, Liliaceae, and Primulaceae

Florists are exposed to many plant species and have a high prevalence of ACD. Thiboutot et al23 found that 15 of 57 (26%) floral workers experienced hand dermatitis that cleared with time away from work. The Peruvian lily (Alstroemeria, Alstroemeriaceae family), which contains tuliposide A, was found to be the leading cause of sensitization.23 Tulips (Tulipa, Liliaceae family), as the flower name suggests, also contain tuliposide A, which along with mechanical irritation from the course tecta fibers on the bulbs lead to a dermatitis known as tulip fingers.24,25 Poison primrose (Primula obconica, Primulaceae family), cultivated for its highly colorful flowers, contains the contact allergen primin.6 A common clinical presentation of ACD for any of these culprit flowers is localized dermatitis of the thumb and index finger in a florist or gardener.

Plants That Cause Irritant Reactions

Cactuses

Although the long spines of the Cactaceae family of cactuses is a warning for passersby, it is the small and nearly invisible barbed hairs (glochids) that inflict a more dramatic cutaneous reaction. The prickly pear cactus (Opuntia species) is a good example of such a plant, as its glochids cause mechanical irritation but also can become embedded in the skin and result in subcutaneous granulomas known as sabra dermatitis.26

Stinging Nettle

The dermatologic term urticaria owes its namesake to the stinging nettle plant, which comes from the family Urticaceae. The stinging nettle has small hairs on its leaves, referred to as stinging trichomes, which have needlelike tips that pierce the skin and inject a mix of histamine, formic acid, and acetylcholine, causing a pruritic dermatitis that may last up to 12 hours.27 The plant is found worldwide and is a common weed in North America.

Phytophotodermatitis

Lemons and limes (Rutaceae family) are common culprits of phytophotodermatitis, often causing what is known as a margarita burn after outdoor consumption or preparation of this tasty citrus beverage.28 An accidental spray of lime juice on the skin while adding it to a beer, guacamole, salsa, or any other food or beverage also can cause phytophotodermatitis.29-31 Although the juice of lemons and limes contains psoralens, the rind can contain a 6- to 186-fold increased concentration.32 Psoralen is the photoactive agent in Rutaceae plants that intercalates in double-stranded DNA and promotes intrastrand cross-links when exposed to UVA light, which ultimately leads to dermatitis.9 Phytophotodermatitis commonly causes erythema, edema, and painful bullae on sun-exposed areas and classically heals with hyperpigmentation.

Pseudophytodermatitis can occur in grain farmers and harvesters who handle wheat and/or barley and incidentally come in contact with insects and chemicals on the plant material. Pseudophytodermatitis from mites in the wheat and/or barley plant can occur at harvest time when contact with the plant material is high. Insects such as the North American itch mite (Pediculoides ventricosus) can cause petechiae, wheals, and pustules. In addition, insecticides such as malathion and arsenical sprays that are applied to plant leaves can cause pseudophytodermatitis, which may be initially diagnosed as dermatitis to the plant itself.6

Patch Testing to Plants

When a patient presents with recurrent or persistent dermatitis and a plant contact allergen is suspected, patch testing is indicated. Most comprehensive patch test series contain various plant allergens, such as sesquiterpene lactones, Compositae mix, and limonene hydroperoxides, and patch testing to a specialized plant series may be necessary. Poison ivy/oak/sumac allergens typically are not included in patch test series because of the high prevalence of allergic reactions to these chemicals and the likelihood of sensitization when patch testing with urushiol. Compositae contact sensitization can be difficult to diagnose because neither sesquiterpene lactone mix 0.1% nor parthenolide 0.1% are sensitive enough to pick up all Compositae allergies.33,34 Paulsen and Andersen34 proposed that if Compositae sensitization is suspected, testing should include sesquiterpene lactone, parthenolide, and Compositae mix II 2.5%, as well as other potential Compositae allergens based on the patient’s history.34

Because plants can have geographic variability and contain potentially unknown allergens,35 testing to plant components may increase the diagnostic yield of patch testing. Dividing the plant into component parts (ie, stem, bulb, leaf, flower) is helpful, as different components have different allergen concentrations. It is important to consult expert resources before proceeding with plant component patch testing because irritant reactions are frequent and may confound the testing.36

Prevention and Treatment

For all plant dermatoses, the mainstay of prevention is to avoid contact with the offending plant material. Gloves can be an important protective tool for plant dermatitis prevention; the correct material depends on the plant species being handled. Rubber gloves should not be worn to protect against Toxicodendron plants since the catechols in urushiol are soluble in rubber; vinyl gloves should be worn instead.6 Marks37 found that tuliposide A, the allergen in the Peruvian lily (Alstroemeria), penetrates both vinyl and latex gloves; it does not penetrate nitrile gloves. If exposed, the risk of dermatitis can be decreased if the allergen is washed away with soap and water as soon as possible. Some allergens such as Toxicodendron are absorbed quickly and need to be washed off within 10 minutes of exposure.6 Importantly, exposed gardening gloves may continue to perpetuate ACD if the allergen is not also washed off the gloves themselves.

For light-mediated dermatoses, sun avoidance or use of an effective sunscreen can reduce symptoms in an individual who has already been exposed.10 UVA light activates psoralen-mediated dermatitis but not until 30 to 120 minutes after absorption into the skin.38

Barrier creams are thought to be protective against plant ACD through a variety of mechanisms. The cream itself is meant to reduce skin contact to an allergen or irritant. Additionally, barrier creams contain active ingredients such as silicone, hydrocarbons, and aluminum chlorohydrate, which are thought to trap or transform offending agents before contacting the skin. When contact with a Toxicodendron species is anticipated, Marks et al39 found that dermatitis was absent or significantly reduced when 144 patients were pretreated with quaternium-18 bentonite lotion 5% (P<.0001).

Although allergen avoidance and use of gloves and barrier creams are the mainstays of preventing plant dermatoses, treatment often is required to control postexposure symptoms. For all plant dermatoses, topical corticosteroids can be used to reduce inflammation and pruritus. In some cases, systemic steroids may be necessary. To prevent rebound of dermatitis, patients often require a 3-week or longer course of oral steroids to quell the reaction, particularly if the dermatitis is vigorous or an id reaction is present.40 Antihistamines and cold compresses also can provide symptomatic relief.

Final Interpretation

Plants can cause a variety of dermatoses. Although Toxicodendron plants are the most frequent cause of ACD, it is important to keep in mind that florists, gardeners, and farmers are exposed to a large variety of allergens, irritants, and phototoxic agents that cause dermatoses as well. Confirmation of plant-induced ACD involves patch testing against suspected species. Prevention involves use of appropriate barriers and avoidance of implicated plants. Treatment includes topical steroids, antihistamines, and prednisone.

Plants can contribute to a variety of dermatoses. The Toxicodendron genus, which includes poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, is a well-known and common cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), but many other plants can cause direct or airborne contact dermatitis, especially in gardeners, florists, and farmers. This article provides an overview of different plant-related dermatoses and culprit plants as well as how these dermatoses should be diagnosed and treated.

Epidemiology

Plant dermatoses affect more than 50 million individuals each year.1,2 In the United States, the Toxicodendron genus causes ACD in more than 70% of exposed individuals, leading to medical visits.3 An urgent care visit for a plant-related dermatitis is estimated to cost $168, while an emergency department visit can cost 3 times as much.4 Although less common, Compositae plants are another important culprit of plant dermatitis, particularly in gardeners, florists, and farmers. Data from the 2017-2018 North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series (N=4947) showed sesquiterpene lactones and Compositae to be positive in 0.5% of patch-tested patients.5

Plant Dermatitis Classifications

Plant dermatitis can be classified into 5 main categories: ACD, mechanical irritant contact dermatitis, chemical irritant contact dermatitis, light-mediated dermatitis, and pseudophytodermatitis.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immune-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The common molecular allergens in plants include phenols, α-methylene-γ-butyrolactones, quinones, terpenes, disulfides, isothiocyanates, and polyacetylenic derivatives.6

Plant contact dermatitis due to mechanical and chemical irritants is precipitated by multiple mechanisms, including disruption of the epidermal barrier and subsequent cytokine release from keratinocytes.7 Nonimmunologic contact urticaria from plants is thought to be a type of irritant reaction precipitated by mechanical or chemical trauma.8

Light-mediated dermatitis includes phytophotodermatitis and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Phytophotodermatitis is a phototoxic reaction triggered by exposure to both plant-derived furanocoumarin and UVA light.9 By contrast, photoallergic contact dermatitis is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction from prior sensitization to a light-activated antigen.10

Pseudophytodermatitis, as its name implies, is not truly mediated by an allergen or irritant intrinsic to the plant but rather by dyes, waxes, insecticides, or arthropods that inhabit the plant or are secondarily applied.6

Common Plant Allergens

Anacardiaceae Family

Most of the allergenic plants within the Anacardiaceae family belong to the Toxicodendron genus, which encompasses poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens,Toxicodendron quercifolium, Toxicodendron diversiloum), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). Poison ivy is the celebrity of the Anacardiaceae family and contributes to most cases of plant-related ACD. It is found in every state in the continental United States. Poison oak is another common culprit found in the western and southeastern United States.11 Plants within the Anacardiaceae family contain an oleoresin called urushiol, which is the primary sensitizing substance. Although poison ivy and poison oak grow well in full sun to partial shade, poison sumac typically is found in damp swampy areas east of the Rocky Mountains. Most cases of ACD related to Anacardiaceae species are due to direct contact with urushiol from a Toxicodendron plant, but burning of brush containing Toxicodendron can cause airborne exposure when urushiol oil is carried by smoke particles.12 Sensitization to Toxicodendron can cause ACD to other Anacardiaceae species such as the Japanese lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), mango tree (Mangifera indica), cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale), and Indian marking nut tree (Semecarpus anacardium).6 Cross-reactions to components of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba) also are possible.

Toxicodendron plants can be more easily identified and avoided with knowledge of their characteristic leaf patterns. The most dependable way to identify poison ivy and poison oak species is to look for plants with 3 leaves, giving rise to the common saying, “Leaves of three, leave them be.” Poison sumac plants have groups of 7 to 13 leaves arranged as pairs along a central rib. Another helpful finding is a black deposit that Toxicodendron species leave behind following trauma to the leaves. Urushiol oxidizes when exposed to air and turns into a black deposit that can be seen on damaged leaves themselves or can be demonstrated in a black spot test to verify if a plant is a Toxicodendron species. The test is performed by gathering (carefully, without direct contact) a few leaves in a paper towel and crushing them to release sap. Within minutes, the sap will turn black if the plant is indeed a Toxicodendron species.13Pruritic, edematous, erythematous papules, plaques, and eventual vesicles in a linear distribution are suspicious for Toxicodendron exposure. Although your pet will not develop Toxicodendron ACD, oleoresin-contaminated pets can transfer the oils to their owners after coming into contact with these plants. Toxicodendron dermatitis also can be acquired from oleoresin-contaminated fomites such as clothing and shoes worn in the garden or when hiking. Toxicodendron dermatitis can appear at different sites on the body at different times depending on the amount of oleoresin exposure as well as epidermal thickness. For example, the oleoresin can be transferred from the hands to body areas with a thinner stratum corneum (eg, genitalia) and cause subsequent dermatitis.1

Compositae Family

The Compositae family (also known as Asteraceae) is a large plant family with more than 20,000 species, including numerous weeds, wildflowers, and vegetables. The flowers, leaves, stems, and pollens of the Compositae family are coated by cyclic esters called sesquiterpene lactones. Mitchell and Dupuis14 showed that sesquiterpene lactones are the allergens responsible for ACD to various Compositae plants, including ragweed (Ambrosia), sneezeweed (Helenium), and chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum). Common Compositae vegetables such as lettuce (Lactuca sativa) have been reported to cause ACD in chefs, grocery store produce handlers, gardeners, and even owners of lettuce-eating pet guinea pigs and turtles.15 Similarly, artichokes (Cynara scolymus) can cause ACD in gardeners.16 Exposure to Compositae species also has been implicated in photoallergic reactions, and studies have demonstrated that some patients with chronic actinic dermatitis also have positive patch test reactions to Compositae species and/or sesquiterpene lactones.17,18

In addition to direct contact with Compositae plants, airborne exposure to sesquiterpene lactones can cause ACD.14 The pattern of airborne contact dermatitis typically involves exposed areas such as the eyelids, central face, and/or neck. The beak sign also can be a clue to airborne contact dermatitis, which involves dermatitis of the face that spares the nasal tip and/or nasal ridge. It is thought that the beak sign may result from increased sebaceous gland concentration on the nose, which prevents penetration of allergens and irritants.19 Unlike photoallergic contact dermatitis, which also can involve the face, airborne ACD frequently involves photoprotected areas such as the submandibular chin and the upper lip. Davies and Kersey20 reported the case of a groundsman who was cutting grass with dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) and was found to have associated airborne ACD of the face, neck, and forearms due to Compositae allergy. In a different setting, the aromas of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) have been reported to cause airborne ACD in a tea drinker.21 Paulsen22 found that ingestion of chamomile tea can induce systemic ACD in sensitized individuals.

Alstroemeriaceae, Liliaceae, and Primulaceae

Florists are exposed to many plant species and have a high prevalence of ACD. Thiboutot et al23 found that 15 of 57 (26%) floral workers experienced hand dermatitis that cleared with time away from work. The Peruvian lily (Alstroemeria, Alstroemeriaceae family), which contains tuliposide A, was found to be the leading cause of sensitization.23 Tulips (Tulipa, Liliaceae family), as the flower name suggests, also contain tuliposide A, which along with mechanical irritation from the course tecta fibers on the bulbs lead to a dermatitis known as tulip fingers.24,25 Poison primrose (Primula obconica, Primulaceae family), cultivated for its highly colorful flowers, contains the contact allergen primin.6 A common clinical presentation of ACD for any of these culprit flowers is localized dermatitis of the thumb and index finger in a florist or gardener.

Plants That Cause Irritant Reactions

Cactuses

Although the long spines of the Cactaceae family of cactuses is a warning for passersby, it is the small and nearly invisible barbed hairs (glochids) that inflict a more dramatic cutaneous reaction. The prickly pear cactus (Opuntia species) is a good example of such a plant, as its glochids cause mechanical irritation but also can become embedded in the skin and result in subcutaneous granulomas known as sabra dermatitis.26

Stinging Nettle

The dermatologic term urticaria owes its namesake to the stinging nettle plant, which comes from the family Urticaceae. The stinging nettle has small hairs on its leaves, referred to as stinging trichomes, which have needlelike tips that pierce the skin and inject a mix of histamine, formic acid, and acetylcholine, causing a pruritic dermatitis that may last up to 12 hours.27 The plant is found worldwide and is a common weed in North America.

Phytophotodermatitis

Lemons and limes (Rutaceae family) are common culprits of phytophotodermatitis, often causing what is known as a margarita burn after outdoor consumption or preparation of this tasty citrus beverage.28 An accidental spray of lime juice on the skin while adding it to a beer, guacamole, salsa, or any other food or beverage also can cause phytophotodermatitis.29-31 Although the juice of lemons and limes contains psoralens, the rind can contain a 6- to 186-fold increased concentration.32 Psoralen is the photoactive agent in Rutaceae plants that intercalates in double-stranded DNA and promotes intrastrand cross-links when exposed to UVA light, which ultimately leads to dermatitis.9 Phytophotodermatitis commonly causes erythema, edema, and painful bullae on sun-exposed areas and classically heals with hyperpigmentation.

Pseudophytodermatitis can occur in grain farmers and harvesters who handle wheat and/or barley and incidentally come in contact with insects and chemicals on the plant material. Pseudophytodermatitis from mites in the wheat and/or barley plant can occur at harvest time when contact with the plant material is high. Insects such as the North American itch mite (Pediculoides ventricosus) can cause petechiae, wheals, and pustules. In addition, insecticides such as malathion and arsenical sprays that are applied to plant leaves can cause pseudophytodermatitis, which may be initially diagnosed as dermatitis to the plant itself.6

Patch Testing to Plants

When a patient presents with recurrent or persistent dermatitis and a plant contact allergen is suspected, patch testing is indicated. Most comprehensive patch test series contain various plant allergens, such as sesquiterpene lactones, Compositae mix, and limonene hydroperoxides, and patch testing to a specialized plant series may be necessary. Poison ivy/oak/sumac allergens typically are not included in patch test series because of the high prevalence of allergic reactions to these chemicals and the likelihood of sensitization when patch testing with urushiol. Compositae contact sensitization can be difficult to diagnose because neither sesquiterpene lactone mix 0.1% nor parthenolide 0.1% are sensitive enough to pick up all Compositae allergies.33,34 Paulsen and Andersen34 proposed that if Compositae sensitization is suspected, testing should include sesquiterpene lactone, parthenolide, and Compositae mix II 2.5%, as well as other potential Compositae allergens based on the patient’s history.34

Because plants can have geographic variability and contain potentially unknown allergens,35 testing to plant components may increase the diagnostic yield of patch testing. Dividing the plant into component parts (ie, stem, bulb, leaf, flower) is helpful, as different components have different allergen concentrations. It is important to consult expert resources before proceeding with plant component patch testing because irritant reactions are frequent and may confound the testing.36

Prevention and Treatment

For all plant dermatoses, the mainstay of prevention is to avoid contact with the offending plant material. Gloves can be an important protective tool for plant dermatitis prevention; the correct material depends on the plant species being handled. Rubber gloves should not be worn to protect against Toxicodendron plants since the catechols in urushiol are soluble in rubber; vinyl gloves should be worn instead.6 Marks37 found that tuliposide A, the allergen in the Peruvian lily (Alstroemeria), penetrates both vinyl and latex gloves; it does not penetrate nitrile gloves. If exposed, the risk of dermatitis can be decreased if the allergen is washed away with soap and water as soon as possible. Some allergens such as Toxicodendron are absorbed quickly and need to be washed off within 10 minutes of exposure.6 Importantly, exposed gardening gloves may continue to perpetuate ACD if the allergen is not also washed off the gloves themselves.

For light-mediated dermatoses, sun avoidance or use of an effective sunscreen can reduce symptoms in an individual who has already been exposed.10 UVA light activates psoralen-mediated dermatitis but not until 30 to 120 minutes after absorption into the skin.38

Barrier creams are thought to be protective against plant ACD through a variety of mechanisms. The cream itself is meant to reduce skin contact to an allergen or irritant. Additionally, barrier creams contain active ingredients such as silicone, hydrocarbons, and aluminum chlorohydrate, which are thought to trap or transform offending agents before contacting the skin. When contact with a Toxicodendron species is anticipated, Marks et al39 found that dermatitis was absent or significantly reduced when 144 patients were pretreated with quaternium-18 bentonite lotion 5% (P<.0001).

Although allergen avoidance and use of gloves and barrier creams are the mainstays of preventing plant dermatoses, treatment often is required to control postexposure symptoms. For all plant dermatoses, topical corticosteroids can be used to reduce inflammation and pruritus. In some cases, systemic steroids may be necessary. To prevent rebound of dermatitis, patients often require a 3-week or longer course of oral steroids to quell the reaction, particularly if the dermatitis is vigorous or an id reaction is present.40 Antihistamines and cold compresses also can provide symptomatic relief.

Final Interpretation

Plants can cause a variety of dermatoses. Although Toxicodendron plants are the most frequent cause of ACD, it is important to keep in mind that florists, gardeners, and farmers are exposed to a large variety of allergens, irritants, and phototoxic agents that cause dermatoses as well. Confirmation of plant-induced ACD involves patch testing against suspected species. Prevention involves use of appropriate barriers and avoidance of implicated plants. Treatment includes topical steroids, antihistamines, and prednisone.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128.

- Pariser D, Ceilley R, Lefkovits A, et al. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm Insights. 2003;4:26-28.

- Wolff K, Johnson R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Education; 2009.

- Zomorodi N, Butt M, Maczuga S, et al. Cost and diagnostic characteristics of Toxicodendron dermatitis in the USA: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:772-773.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123.

- Fowler JF, Zirwas MJ. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 7th ed. Contact Dermatitis Institute; 2019.

- Smith HR, Basketter DA, McFadden JP. Irritant dermatitis, irritancy and its role in allergic contact dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:138-146.

- Wakelin SH. Contact urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:132-136.

- Ellis CR, Elston DM. Psoralen-induced phytophotodermatitis. Dermatitis. 2021;32:140-143.

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Poisonous plants. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 1, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/plants/geographic.html

- Schloemer JA, Zirwas MJ, Burkhart CG. Airborne contact dermatitis: common causes in the USA. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:271-274.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Mitchell J, Dupuis G. Allergic contact dermatitis from sesquiterpenoids of the Compositae family of plants. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:139-150.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Lettuce contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:67-75.

- Samaran Q, Clark E, Dereure O, et al. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis caused by artichoke. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:395-397.

- Du H, Ross JS, Norris PG, et al. Contact and photocontact sensitization in chronic actinic dermatitis: sesquiterpene lactone mix is an important allergen. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:543-547.

- Wrangsjo K, Marie Ros A, Walhberg JE. Contact allergy to Compositae plants in patients with summer-exacerbated dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:148-154.

- Staser K, Ezra N, Sheehan MP, et al. The beak sign: a clinical clue to airborne contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2014;25:97-98.

- Davies M, Kersey J. Contact allergy to yarrow and dandelion. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:256-257.

- Anzai A, Vázquez Herrera NE, Tosti A. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis caused by chamomile tea. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72:254-255.

- Paulsen E. Systemic allergic dermatitis caused by sesquiterpene lactones. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:1-10.

- Thiboutot DM, Hamory BH, Marks JG. Dermatoses among floral shop workers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:54-58.

- Hjorth N, Wilkinson DS. Contact dermatitis IV. tulip fingers, hyacinth itch and lily rash. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:696-698.

- Guin JD, Franks H. Fingertip dermatitis in a retail florist. Cutis. 2001;67:328-330.

- Magro C, Lipner S. Sabra dermatitis: combined features of delayed hypersensitivity and foreign body reaction to implanted glochidia. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt2157f9g0.

- Cummings AJ, Olsen M. Mechanism of action of stinging nettles. Wilderness Environ Med. 2011;22:136-139.

- Maniam G, Light KML, Wilson J. Margarita burn: recognition and treatment of phytophotodermatitis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:398-401.

- Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

- Kung AC, Stephens MB, Darling T. Phytophotodermatitis: bulla formation and hyperpigmentation during spring break. Mil Med. 2009;174:657-661.

- Smith LG. Phytophotodermatitis. Images Emerg Med. 2017;1:146-147.

- Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

- Green C, Ferguson J. Sesquiterpene lactone mix is not an adequate screen for Compositae allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:151-153.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Screening for Compositae contact sensitization with sesquiterpene lactones and Compositae mix 2.5% pet. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:368-373.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Patch testing with constituents of Compositae mixes. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:241-246.

- Frosch PJ, Geier J, Uter W, et al. Patch testing with the patients’ own products. Contact Dermatitis. 2011:929-941.

- Marks JG. Allergic contact dermatitis to Alstroemeria. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:914-916.

- Moreau JF, English JC, Gehris RP. Phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27:93-94.

- Marks JG, Fowler JF, Sherertz EF, et al. Prevention of poison ivy and poison oak allergic contact dermatitis by quaternium-18 bentonite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:212-216.

- Craig K, Meadows SE. What is the best duration of steroid therapy for contact dermatitis (rhus)? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:166-167.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128.

- Pariser D, Ceilley R, Lefkovits A, et al. Poison ivy, oak and sumac. Derm Insights. 2003;4:26-28.

- Wolff K, Johnson R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Education; 2009.

- Zomorodi N, Butt M, Maczuga S, et al. Cost and diagnostic characteristics of Toxicodendron dermatitis in the USA: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:772-773.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123.

- Fowler JF, Zirwas MJ. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 7th ed. Contact Dermatitis Institute; 2019.

- Smith HR, Basketter DA, McFadden JP. Irritant dermatitis, irritancy and its role in allergic contact dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:138-146.

- Wakelin SH. Contact urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:132-136.

- Ellis CR, Elston DM. Psoralen-induced phytophotodermatitis. Dermatitis. 2021;32:140-143.

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Poisonous plants. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 1, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/plants/geographic.html

- Schloemer JA, Zirwas MJ, Burkhart CG. Airborne contact dermatitis: common causes in the USA. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:271-274.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Mitchell J, Dupuis G. Allergic contact dermatitis from sesquiterpenoids of the Compositae family of plants. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:139-150.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Lettuce contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:67-75.

- Samaran Q, Clark E, Dereure O, et al. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis caused by artichoke. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:395-397.

- Du H, Ross JS, Norris PG, et al. Contact and photocontact sensitization in chronic actinic dermatitis: sesquiterpene lactone mix is an important allergen. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:543-547.

- Wrangsjo K, Marie Ros A, Walhberg JE. Contact allergy to Compositae plants in patients with summer-exacerbated dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:148-154.

- Staser K, Ezra N, Sheehan MP, et al. The beak sign: a clinical clue to airborne contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2014;25:97-98.