User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

A new (old) drug joins the COVID fray, and guess what? It works

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

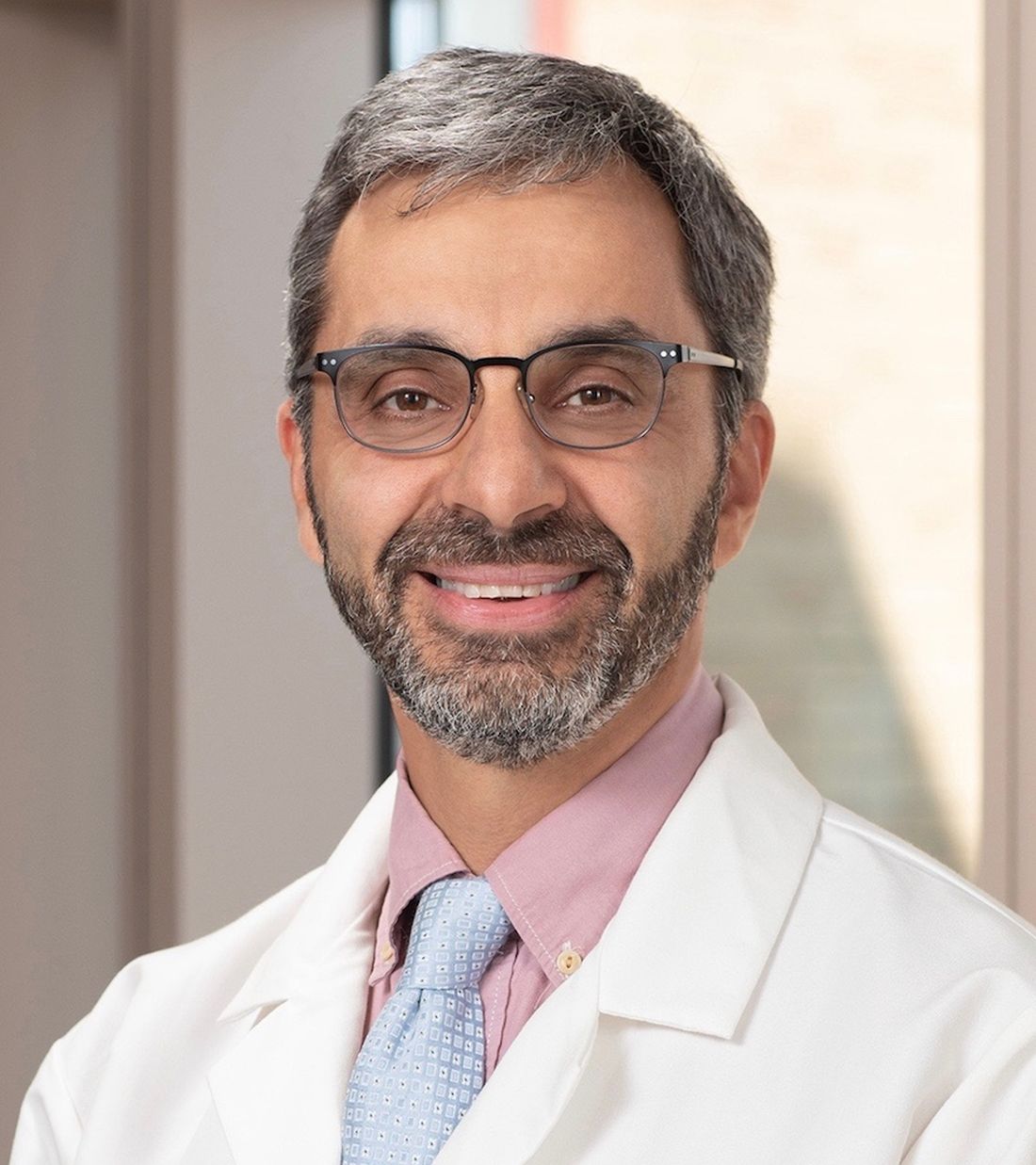

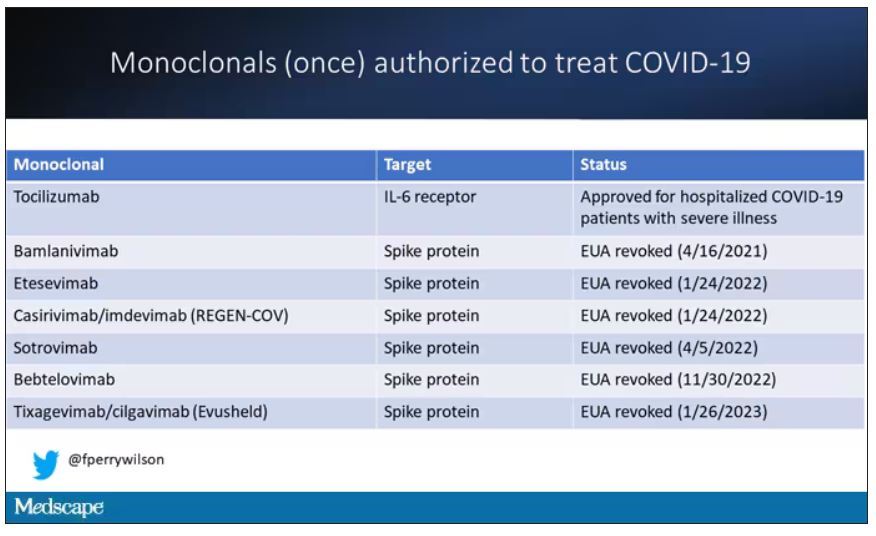

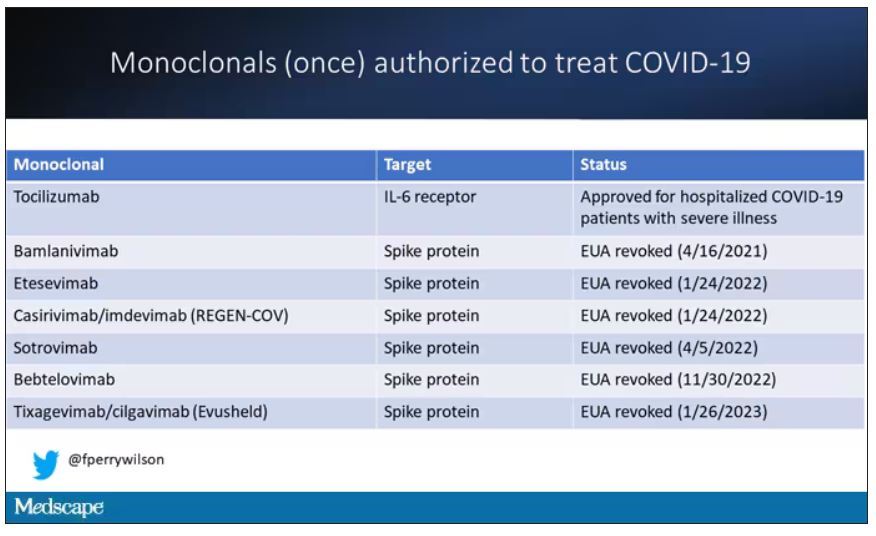

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

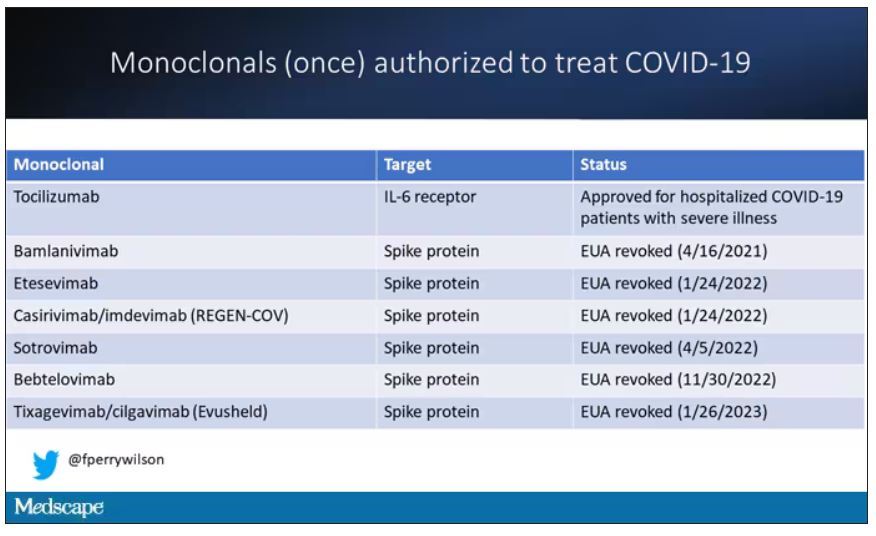

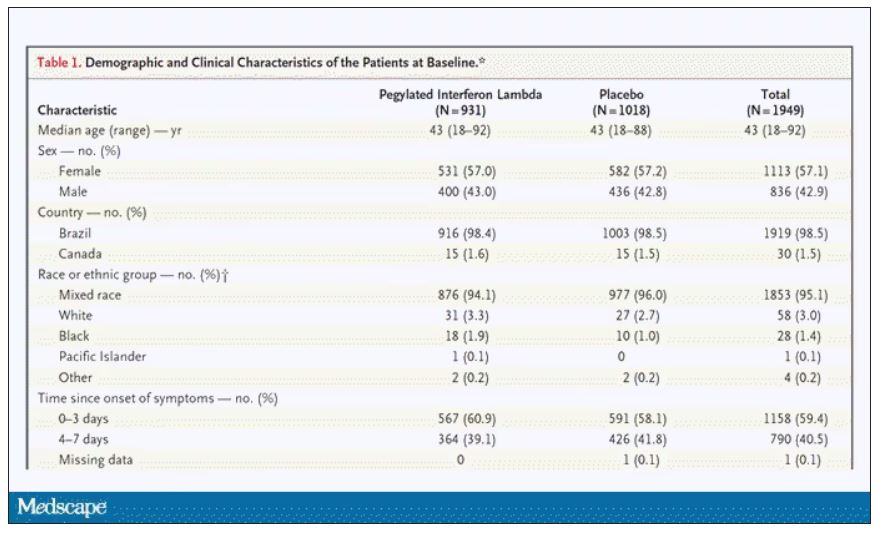

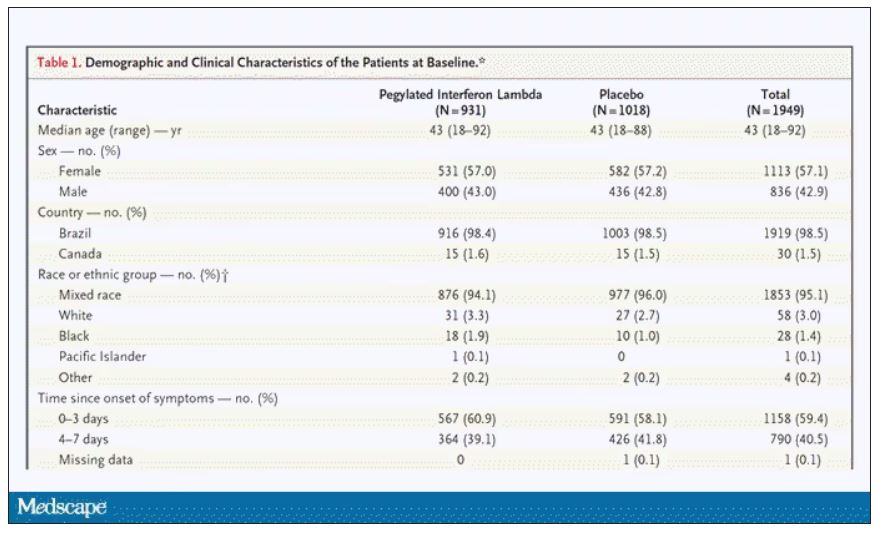

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

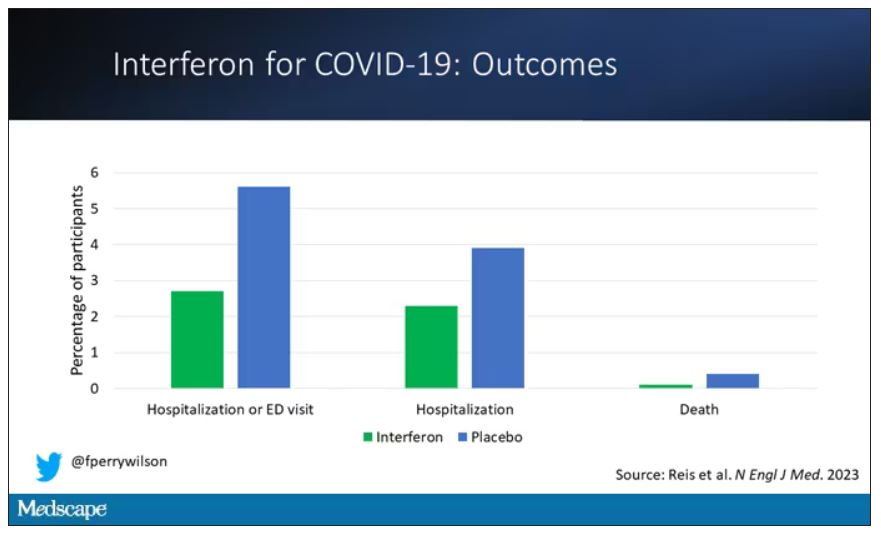

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

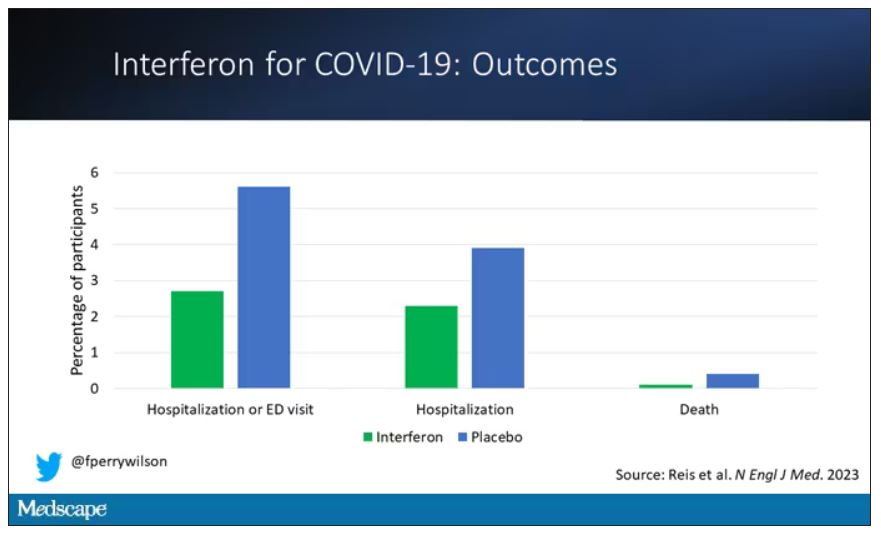

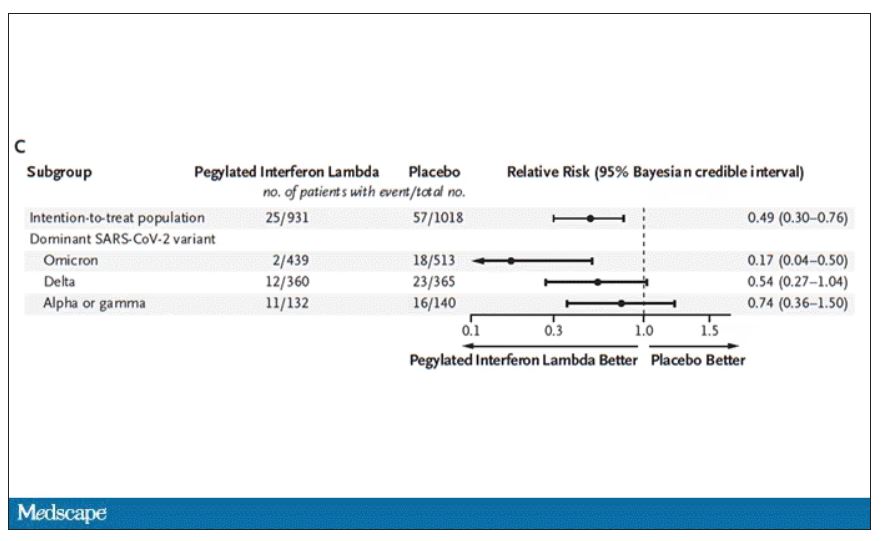

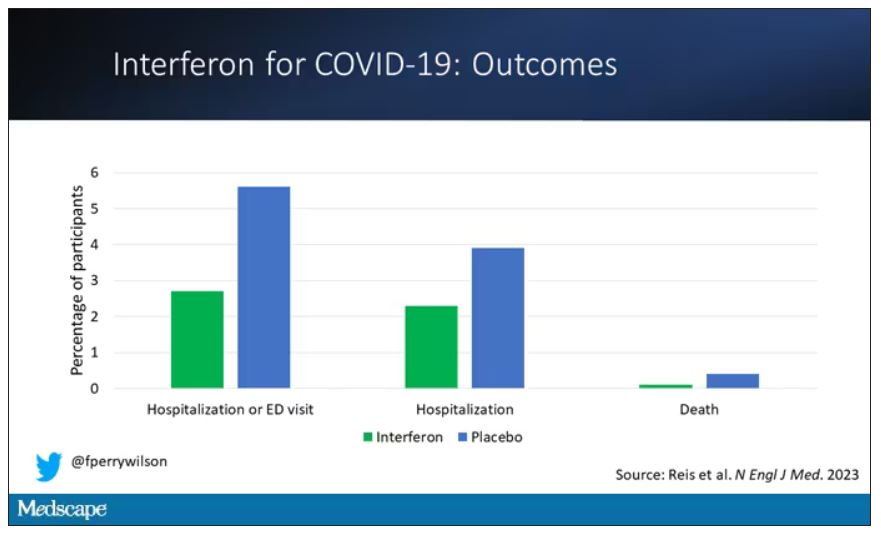

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

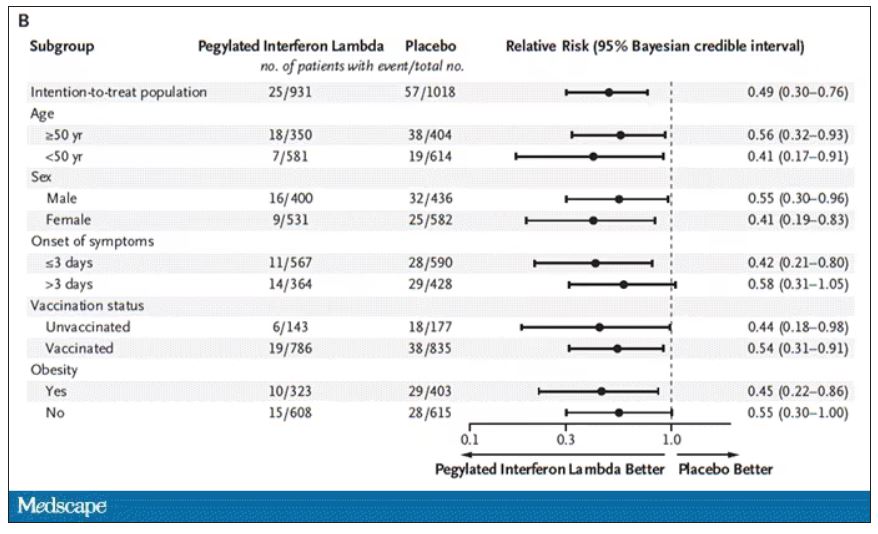

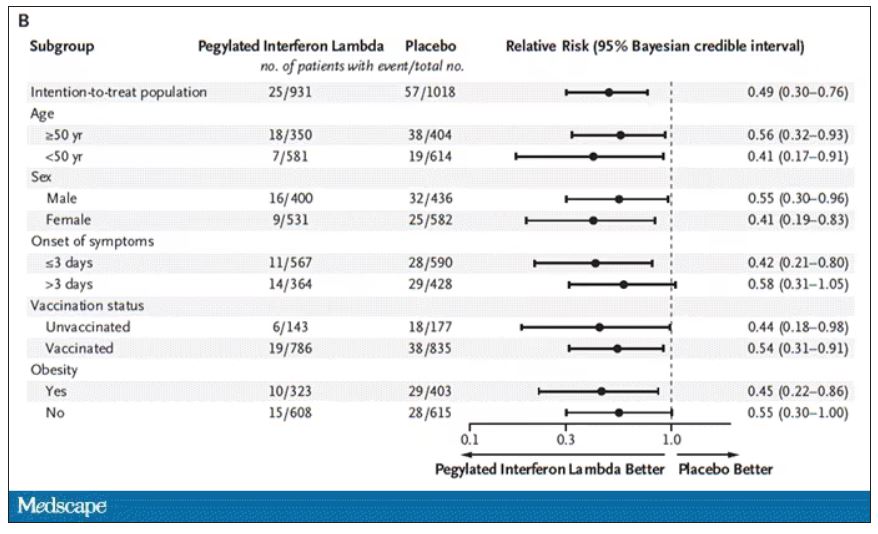

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

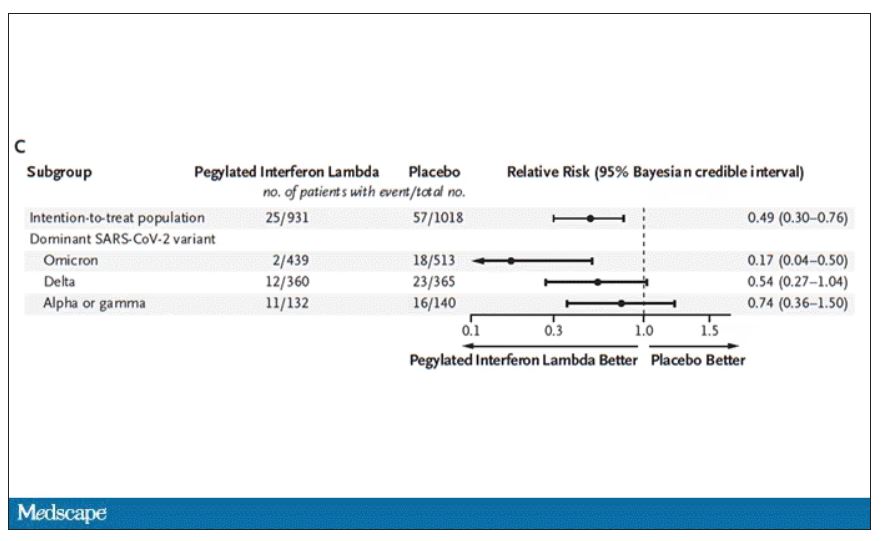

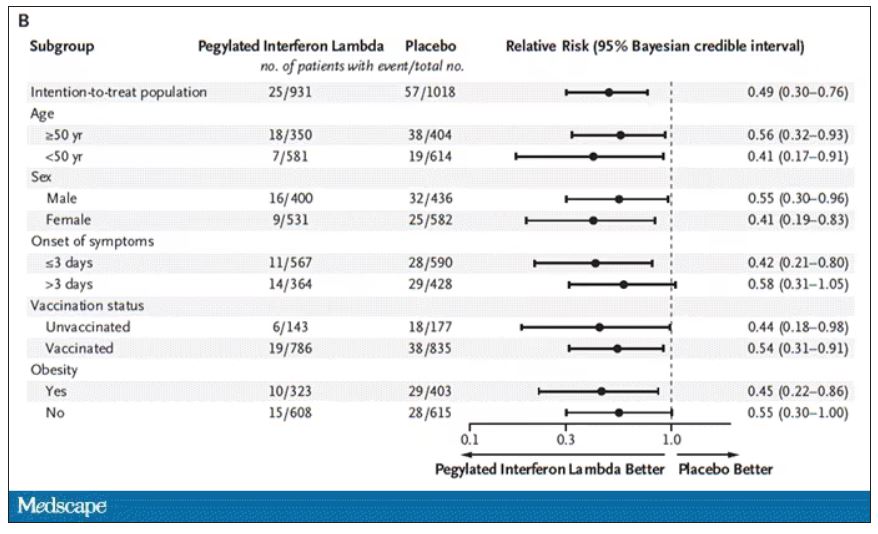

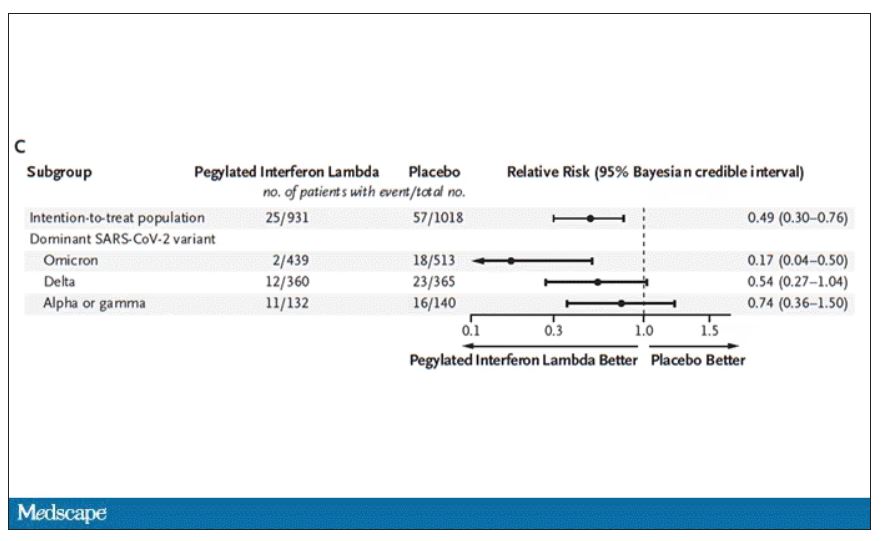

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

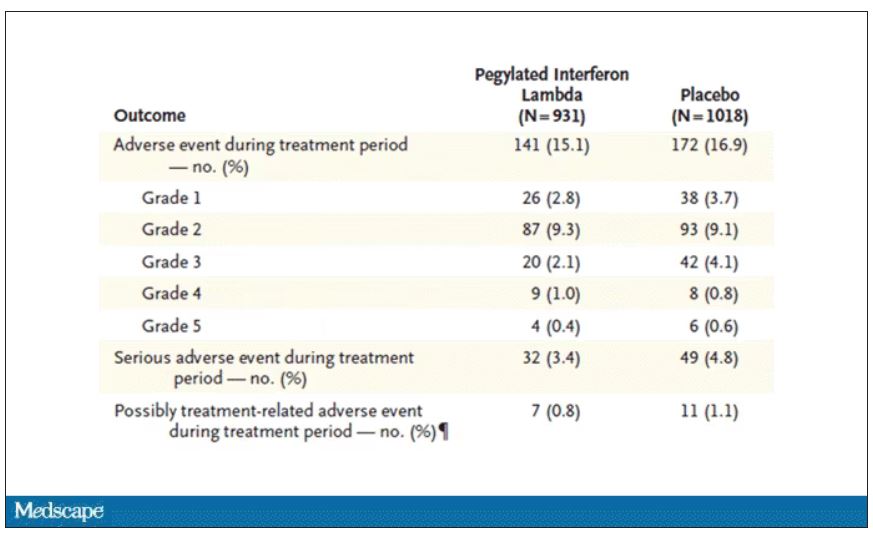

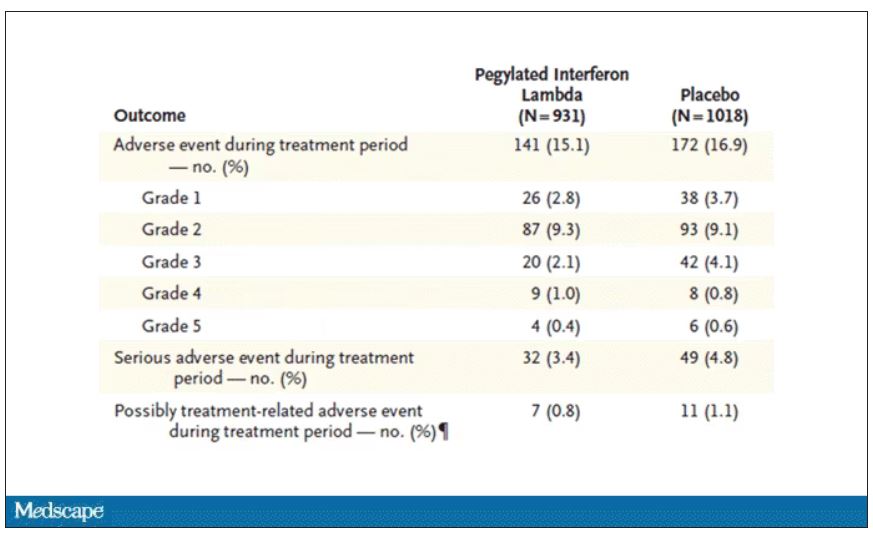

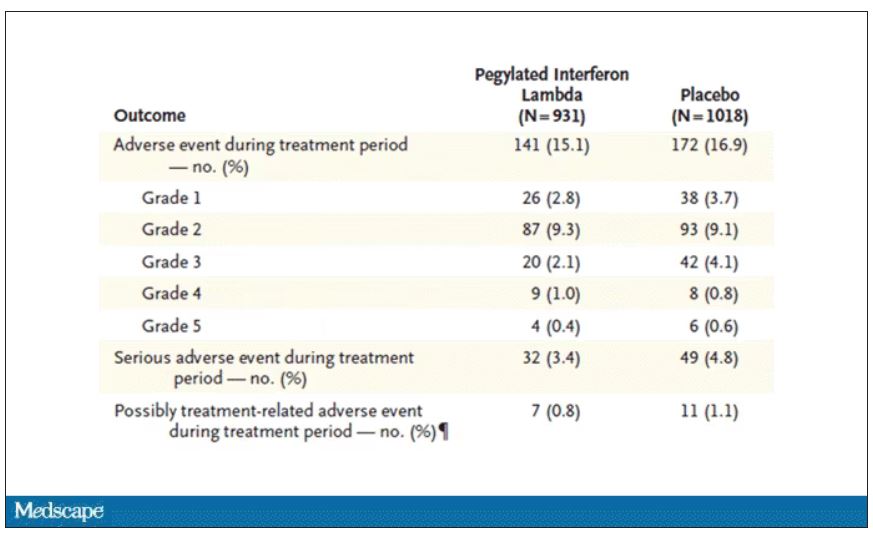

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

We should all have more Shakespeare in our lives. Yeah, yeah, Shakespeare is meant to be played, not read, and it can be a struggle to herd teenagers through the Bard’s interesting and bloody tragedies, but even a perfunctory reading of “The Merchant of Venice” would hopefully have prevented the dystopian nightmare Massachusetts has presented us with today.

The United States has a massive shortage of donor organs. This is an unfortunate truth. So, to combat this issue, a pair of Massachusetts congresspeople have proposed HD 3822, which would allow prisoners to donate organs and/or bone marrow (a pound of flesh, so to speak) in exchange for up to a year in reduced prison time. Yes, that’s right. Give up pieces of yourself and the state of Massachusetts will deign to reduce your long prison sentence.

Oh, and before you dismiss this as typical Republican antics, the bill was sponsored by two Democrats, and in a statement one of them hoped to address racial disparities in organ donation, as people of color are much less likely to receive organs. Never mind that Black people are imprisoned at a much higher rate than Whites.

Yeah, this whole thing is what people in the business like to call an ethical disaster.

Fortunately, the bill will likely never be passed and it’s probably illegal anyway. A federal law from 1984 (how’s that for a coincidence) prevents people from donating organs for use in human transplantation in exchange for “valuable consideration.” In other words, you can’t sell your organs for profit, and in this case, reducing prison time would probably count as valuable consideration in the eyes of the courts.

Oh, and in case you’ve never read Merchant of Venice, Shylock, the character looking for the pound of flesh as payment for a debt? He’s the villain. In fact, it’s pretty safe to say that anyone looking to extract payment from human dismemberment is probably the bad guy of the story. Apparently that wasn’t clear.

How do you stop a fungi? With a deadly guy

Thanks to the new HBO series “The Last of Us,” there’s been a lot of talk about the upcoming fungi-pocalypse, as the show depicts the real-life “zombie fungus” Cordyceps turning humans into, you know, zombies.

No need to worry, ladies and gentleman, because science has discovered a way to turn back the fungal horde. A heroic, and environmentally friendly, alternative to chemical pesticides “in the fight against resistant fungi [that] are now resistant to antimycotics – partly because they are used in large quantities in agricultural fields,” investigators at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Jena, Germany, said in a written statement.

We are, of course, talking about Keanu Reeves. Wait a second. He’s not even in “The Last of Us.” Sorry folks, we are being told that it really is Keanu Reeves. Our champion in the inevitable fungal pandemic is movie star Keanu Reeves. Sort of. It’s actually keanumycin, a substance produced by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas.

Really? Keanumycin? “The lipopeptides kill so efficiently that we named them after Keanu Reeves because he, too, is extremely deadly in his roles,” lead author Sebastian Götze, PhD, explained.

Dr. Götze and his associates had been working with pseudomonads for quite a while before they were able to isolate the toxins responsible for their ability to kill amoebae, which resemble fungi in some characteristics. When then finally tried the keanumycin against gray mold rot on hydrangea leaves, the intensely contemplative star of “The Matrix” and “John Wick” – sorry, wrong Keanu – the bacterial derivative significantly inhibited growth of the fungus, they said.

Additional testing has shown that keanumycin is not highly toxic to human cells and is effective against fungi such as Candida albicans in very low concentrations, which makes it a good candidate for future pharmaceutical development.

To that news there can be only one response from the substance’s namesake.

High fat, bye parasites

Fat. Fat. Fat. Seems like everyone is trying to avoid it these days, but fat may be good thing when it comes to weaseling out a parasite.

The parasite in this case is the whipworm, aka Trichuris trichiura. You can find this guy in the intestines of millions of people, where it causes long-lasting infections. Yikes … Researchers have found that the plan of attack to get rid of this invasive species is to boost the immune system, but instead of vitamin C and zinc it’s fat they’re pumping in. Yes, fat.

The developing countries with poor sewage that are at the highest risk for contracting parasites such as this also are among those where people ingest cheaper diets that are generally higher in fat. The investigators were interested to see how a high-fat diet would affect immune responses to the whipworms.

And, as with almost everything else, the researchers turned to mice, which were introduced to a closely related species, Trichuris muris.

A high-fat diet, rather than obesity itself, increases a molecule on T-helper cells called ST2, and this allows an increased T-helper 2 response, effectively giving eviction notices to the parasites in the intestinal lining.

To say the least, the researchers were surprised since “high-fat diets are mostly associated with increased pathology during disease,” said senior author Richard Grencis, PhD, of the University of Manchester (England), who noted that ST2 is not normally triggered with a standard diet in mice but the high-fat diet gave it a boost and an “alternate pathway” out.

Now before you start ordering extra-large fries at the drive-through to keep the whipworms away, the researchers added that they “have previously published that weight loss can aid the expulsion of a different gut parasite worm.” Figures.

Once again, though, signs are pointing to the gut for improved health.

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

We should all have more Shakespeare in our lives. Yeah, yeah, Shakespeare is meant to be played, not read, and it can be a struggle to herd teenagers through the Bard’s interesting and bloody tragedies, but even a perfunctory reading of “The Merchant of Venice” would hopefully have prevented the dystopian nightmare Massachusetts has presented us with today.

The United States has a massive shortage of donor organs. This is an unfortunate truth. So, to combat this issue, a pair of Massachusetts congresspeople have proposed HD 3822, which would allow prisoners to donate organs and/or bone marrow (a pound of flesh, so to speak) in exchange for up to a year in reduced prison time. Yes, that’s right. Give up pieces of yourself and the state of Massachusetts will deign to reduce your long prison sentence.

Oh, and before you dismiss this as typical Republican antics, the bill was sponsored by two Democrats, and in a statement one of them hoped to address racial disparities in organ donation, as people of color are much less likely to receive organs. Never mind that Black people are imprisoned at a much higher rate than Whites.

Yeah, this whole thing is what people in the business like to call an ethical disaster.

Fortunately, the bill will likely never be passed and it’s probably illegal anyway. A federal law from 1984 (how’s that for a coincidence) prevents people from donating organs for use in human transplantation in exchange for “valuable consideration.” In other words, you can’t sell your organs for profit, and in this case, reducing prison time would probably count as valuable consideration in the eyes of the courts.

Oh, and in case you’ve never read Merchant of Venice, Shylock, the character looking for the pound of flesh as payment for a debt? He’s the villain. In fact, it’s pretty safe to say that anyone looking to extract payment from human dismemberment is probably the bad guy of the story. Apparently that wasn’t clear.

How do you stop a fungi? With a deadly guy

Thanks to the new HBO series “The Last of Us,” there’s been a lot of talk about the upcoming fungi-pocalypse, as the show depicts the real-life “zombie fungus” Cordyceps turning humans into, you know, zombies.

No need to worry, ladies and gentleman, because science has discovered a way to turn back the fungal horde. A heroic, and environmentally friendly, alternative to chemical pesticides “in the fight against resistant fungi [that] are now resistant to antimycotics – partly because they are used in large quantities in agricultural fields,” investigators at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Jena, Germany, said in a written statement.

We are, of course, talking about Keanu Reeves. Wait a second. He’s not even in “The Last of Us.” Sorry folks, we are being told that it really is Keanu Reeves. Our champion in the inevitable fungal pandemic is movie star Keanu Reeves. Sort of. It’s actually keanumycin, a substance produced by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas.

Really? Keanumycin? “The lipopeptides kill so efficiently that we named them after Keanu Reeves because he, too, is extremely deadly in his roles,” lead author Sebastian Götze, PhD, explained.

Dr. Götze and his associates had been working with pseudomonads for quite a while before they were able to isolate the toxins responsible for their ability to kill amoebae, which resemble fungi in some characteristics. When then finally tried the keanumycin against gray mold rot on hydrangea leaves, the intensely contemplative star of “The Matrix” and “John Wick” – sorry, wrong Keanu – the bacterial derivative significantly inhibited growth of the fungus, they said.

Additional testing has shown that keanumycin is not highly toxic to human cells and is effective against fungi such as Candida albicans in very low concentrations, which makes it a good candidate for future pharmaceutical development.

To that news there can be only one response from the substance’s namesake.

High fat, bye parasites

Fat. Fat. Fat. Seems like everyone is trying to avoid it these days, but fat may be good thing when it comes to weaseling out a parasite.

The parasite in this case is the whipworm, aka Trichuris trichiura. You can find this guy in the intestines of millions of people, where it causes long-lasting infections. Yikes … Researchers have found that the plan of attack to get rid of this invasive species is to boost the immune system, but instead of vitamin C and zinc it’s fat they’re pumping in. Yes, fat.

The developing countries with poor sewage that are at the highest risk for contracting parasites such as this also are among those where people ingest cheaper diets that are generally higher in fat. The investigators were interested to see how a high-fat diet would affect immune responses to the whipworms.

And, as with almost everything else, the researchers turned to mice, which were introduced to a closely related species, Trichuris muris.

A high-fat diet, rather than obesity itself, increases a molecule on T-helper cells called ST2, and this allows an increased T-helper 2 response, effectively giving eviction notices to the parasites in the intestinal lining.

To say the least, the researchers were surprised since “high-fat diets are mostly associated with increased pathology during disease,” said senior author Richard Grencis, PhD, of the University of Manchester (England), who noted that ST2 is not normally triggered with a standard diet in mice but the high-fat diet gave it a boost and an “alternate pathway” out.

Now before you start ordering extra-large fries at the drive-through to keep the whipworms away, the researchers added that they “have previously published that weight loss can aid the expulsion of a different gut parasite worm.” Figures.

Once again, though, signs are pointing to the gut for improved health.

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

We should all have more Shakespeare in our lives. Yeah, yeah, Shakespeare is meant to be played, not read, and it can be a struggle to herd teenagers through the Bard’s interesting and bloody tragedies, but even a perfunctory reading of “The Merchant of Venice” would hopefully have prevented the dystopian nightmare Massachusetts has presented us with today.

The United States has a massive shortage of donor organs. This is an unfortunate truth. So, to combat this issue, a pair of Massachusetts congresspeople have proposed HD 3822, which would allow prisoners to donate organs and/or bone marrow (a pound of flesh, so to speak) in exchange for up to a year in reduced prison time. Yes, that’s right. Give up pieces of yourself and the state of Massachusetts will deign to reduce your long prison sentence.

Oh, and before you dismiss this as typical Republican antics, the bill was sponsored by two Democrats, and in a statement one of them hoped to address racial disparities in organ donation, as people of color are much less likely to receive organs. Never mind that Black people are imprisoned at a much higher rate than Whites.

Yeah, this whole thing is what people in the business like to call an ethical disaster.

Fortunately, the bill will likely never be passed and it’s probably illegal anyway. A federal law from 1984 (how’s that for a coincidence) prevents people from donating organs for use in human transplantation in exchange for “valuable consideration.” In other words, you can’t sell your organs for profit, and in this case, reducing prison time would probably count as valuable consideration in the eyes of the courts.

Oh, and in case you’ve never read Merchant of Venice, Shylock, the character looking for the pound of flesh as payment for a debt? He’s the villain. In fact, it’s pretty safe to say that anyone looking to extract payment from human dismemberment is probably the bad guy of the story. Apparently that wasn’t clear.

How do you stop a fungi? With a deadly guy

Thanks to the new HBO series “The Last of Us,” there’s been a lot of talk about the upcoming fungi-pocalypse, as the show depicts the real-life “zombie fungus” Cordyceps turning humans into, you know, zombies.

No need to worry, ladies and gentleman, because science has discovered a way to turn back the fungal horde. A heroic, and environmentally friendly, alternative to chemical pesticides “in the fight against resistant fungi [that] are now resistant to antimycotics – partly because they are used in large quantities in agricultural fields,” investigators at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Jena, Germany, said in a written statement.

We are, of course, talking about Keanu Reeves. Wait a second. He’s not even in “The Last of Us.” Sorry folks, we are being told that it really is Keanu Reeves. Our champion in the inevitable fungal pandemic is movie star Keanu Reeves. Sort of. It’s actually keanumycin, a substance produced by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas.

Really? Keanumycin? “The lipopeptides kill so efficiently that we named them after Keanu Reeves because he, too, is extremely deadly in his roles,” lead author Sebastian Götze, PhD, explained.

Dr. Götze and his associates had been working with pseudomonads for quite a while before they were able to isolate the toxins responsible for their ability to kill amoebae, which resemble fungi in some characteristics. When then finally tried the keanumycin against gray mold rot on hydrangea leaves, the intensely contemplative star of “The Matrix” and “John Wick” – sorry, wrong Keanu – the bacterial derivative significantly inhibited growth of the fungus, they said.

Additional testing has shown that keanumycin is not highly toxic to human cells and is effective against fungi such as Candida albicans in very low concentrations, which makes it a good candidate for future pharmaceutical development.

To that news there can be only one response from the substance’s namesake.

High fat, bye parasites

Fat. Fat. Fat. Seems like everyone is trying to avoid it these days, but fat may be good thing when it comes to weaseling out a parasite.

The parasite in this case is the whipworm, aka Trichuris trichiura. You can find this guy in the intestines of millions of people, where it causes long-lasting infections. Yikes … Researchers have found that the plan of attack to get rid of this invasive species is to boost the immune system, but instead of vitamin C and zinc it’s fat they’re pumping in. Yes, fat.

The developing countries with poor sewage that are at the highest risk for contracting parasites such as this also are among those where people ingest cheaper diets that are generally higher in fat. The investigators were interested to see how a high-fat diet would affect immune responses to the whipworms.

And, as with almost everything else, the researchers turned to mice, which were introduced to a closely related species, Trichuris muris.

A high-fat diet, rather than obesity itself, increases a molecule on T-helper cells called ST2, and this allows an increased T-helper 2 response, effectively giving eviction notices to the parasites in the intestinal lining.

To say the least, the researchers were surprised since “high-fat diets are mostly associated with increased pathology during disease,” said senior author Richard Grencis, PhD, of the University of Manchester (England), who noted that ST2 is not normally triggered with a standard diet in mice but the high-fat diet gave it a boost and an “alternate pathway” out.

Now before you start ordering extra-large fries at the drive-through to keep the whipworms away, the researchers added that they “have previously published that weight loss can aid the expulsion of a different gut parasite worm.” Figures.

Once again, though, signs are pointing to the gut for improved health.

Drinking tea can keep your heart healthy as you age

according to the Heart Foundation and researchers from Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia.

What to know

- Elderly women who drank black tea on a regular basis or consumed a high level of flavonoids in their diet were found to be far less likely to develop extensive AAC.

- AAC is calcification of the large artery that supplies oxygenated blood from the heart to the abdominal organs and lower limbs. It is associated with cardiovascular disorders, such as heart attack and stroke, as well as late-life dementia.

- Flavonoids are naturally occurring substances that regulate cellular activity. They are found in many common foods and beverages, such as black tea, green tea, apples, nuts, citrus fruit, berries, red wine, dark chocolate, and others.

- Study participants who had a higher intake of total flavonoids, flavan-3-ols, and flavonols were almost 40% less likely to have extensive AAC, while those who drank two to six cups of black tea per day had up to 42% less chance of experiencing extensive AAC.

- People who do not drink tea can still benefit by including foods rich in flavonoids in their diet, which protects against extensive calcification of the arteries.

This is a summary of the article, “Higher Habitual Dietary Flavonoid Intake Associates With Less Extensive Abdominal Aortic Calcification in a Cohort of Older Women,” published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology on Nov. 2, 2022. The full article can be found on ahajournals.org. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the Heart Foundation and researchers from Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia.

What to know

- Elderly women who drank black tea on a regular basis or consumed a high level of flavonoids in their diet were found to be far less likely to develop extensive AAC.

- AAC is calcification of the large artery that supplies oxygenated blood from the heart to the abdominal organs and lower limbs. It is associated with cardiovascular disorders, such as heart attack and stroke, as well as late-life dementia.

- Flavonoids are naturally occurring substances that regulate cellular activity. They are found in many common foods and beverages, such as black tea, green tea, apples, nuts, citrus fruit, berries, red wine, dark chocolate, and others.

- Study participants who had a higher intake of total flavonoids, flavan-3-ols, and flavonols were almost 40% less likely to have extensive AAC, while those who drank two to six cups of black tea per day had up to 42% less chance of experiencing extensive AAC.

- People who do not drink tea can still benefit by including foods rich in flavonoids in their diet, which protects against extensive calcification of the arteries.

This is a summary of the article, “Higher Habitual Dietary Flavonoid Intake Associates With Less Extensive Abdominal Aortic Calcification in a Cohort of Older Women,” published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology on Nov. 2, 2022. The full article can be found on ahajournals.org. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the Heart Foundation and researchers from Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia.

What to know

- Elderly women who drank black tea on a regular basis or consumed a high level of flavonoids in their diet were found to be far less likely to develop extensive AAC.

- AAC is calcification of the large artery that supplies oxygenated blood from the heart to the abdominal organs and lower limbs. It is associated with cardiovascular disorders, such as heart attack and stroke, as well as late-life dementia.

- Flavonoids are naturally occurring substances that regulate cellular activity. They are found in many common foods and beverages, such as black tea, green tea, apples, nuts, citrus fruit, berries, red wine, dark chocolate, and others.

- Study participants who had a higher intake of total flavonoids, flavan-3-ols, and flavonols were almost 40% less likely to have extensive AAC, while those who drank two to six cups of black tea per day had up to 42% less chance of experiencing extensive AAC.

- People who do not drink tea can still benefit by including foods rich in flavonoids in their diet, which protects against extensive calcification of the arteries.

This is a summary of the article, “Higher Habitual Dietary Flavonoid Intake Associates With Less Extensive Abdominal Aortic Calcification in a Cohort of Older Women,” published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology on Nov. 2, 2022. The full article can be found on ahajournals.org. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In families with gout, obesity and alcohol add to personal risk

Gout-associated genetic factors increase the risk of gout by nearly two and a half times among people with a close family history of the disease. The risk is approximately three times higher among people with a family history of gout who are also heavy drinkers; for people with a family history of gout who are also overweight, the risk is four times higher, according to a large population-based study from South Korea.

The increased familial risk of gout (hazard ratio, 2.42) dropped only slightly after adjustment for lifestyle and biological risk factors (HR, 2.29), suggesting that genes are the key drivers for the risk of gout among first-degree relatives.

Risk was highest among individuals with an affected brother (HR, 3.00), followed by father (HR, 2.33), sister (HR, 1.97), and mother (HR, 1.68).

“Although the familial aggregation of gout [where a first-degree relative has the disease] is influenced by both genetic and lifestyle/biological factors, our findings suggest that a genetic predisposition is the predominant driver of familial aggregation,” first author Kyoung-Hoon Kim, PhD, from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Wonju-si, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care and Research.

However, lifestyle is still important, as suggested by comparisons with members of the general population who do not have a family history of gout or a high body mass index (BMI). The risk increased for persons with a family history of gout who were also overweight (HR, 4.39), and it increased further for people with obesity (HR, 6.62), suggesting a dose-response interaction, the authors wrote.

When family history was combined with heavy alcohol consumption, the risk rose (HR, 2.95) in comparison with the general population who had neither risk factor.

The study fills a gap in evidence on “familial risk of gout as opposed to hereditary risk of gout, which has long been recognized,” the researchers wrote.

In addition, the findings suggest the possibility of a dose-dependent gene-environment interaction, “as the combination of both a family history of gout and either high BMI or heavy alcohol consumption was associated with a markedly increased risk of disease, which was even further elevated among obese individuals.”

Abhishek Abhishek, MD, professor of rheumatology and honorary consultant rheumatologist at Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, reflected on the minimal attenuation after adjustment for lifestyle and demographic factors. “This suggests that most of the familial impact is, in fact, genetic rather than due to shared environmental factors and is an important finding.”

He said in an interview that the findings also confirmed the synergistic effect of genetic and lifestyle factors in causing gout. “Lifestyle factors such as alcohol excess and obesity should be addressed more aggressively in those with a first-degree relative with gout.

“Although not directly evaluated in this study, aggressive management of excess weight and high alcohol consumption may prevent the onset of gout or improve its outcomes in those who already have this condition,” he added.

Study of over 5 million individuals with familial aggregation of gout

The researchers drew on data from the government-operated mandatory insurance service that provides for South Korea’s entire population of over 50 million people (the National Health Insurance database), as well as the National Health Screening Program database. Information on familial relationships and risk factor data were identified for 5,524,403 individuals from 2002 to 2018 who had a blood-related first-degree relative.

Familial risk was calculated by comparing the risk of individuals with and those without affected first-degree relatives. Interactions between family history and obesity or alcohol consumption were assessed using a scale that measured gout risk due to interaction of two factors.

Initially, adjustments to familial risk were made with respect to age and sex. Subsequently, possible risk factors included smoking, BMI, hypertension, and hyperglycemia.

Alcohol consumption levels were noted and categorized as nondrinker, moderate drinker, or heavy drinker, with different consumption levels for men and women. For men, heavy drinking was defined as having at least two drinks per week and at least five drinks on any day; for women, heavy drinking was defined as having at least two drinks per week and at least four drinks on any day.

Overweight and obesity were determined on the basis of BMI, using standard categories: overweight was defined as BMI of 25 to less than 30 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as BMI of 30 or higher.

Dr. Kim and coauthors noted that both high BMI and heavy drinking were associated with an increased risk of gout, regardless of whether there was a family history of the disease, and that the findings suggest “a dose-dependent interactive relationship in which genetic factors and obesity potentiate each other rather than operating independently.”

People who are both overweight and have a family history of disease had a combined risk of gout that was significantly higher than the sum of their individual risk factors (HR, 4.39 vs. 3.43). This risk was accentuated among people with obesity (HR, 6.62 vs. 4.74) and was more pronounced in men than in women.

In other risk analyses in which familial and nonfamilial gout risk groups were compared, the risk associated with obesity was higher in the familial, compared with the nonfamilial group (HR, 5.50 vs. 5.36).

Bruce Rothschild, MD, a rheumatologist with Indiana University Health, Muncie, and research associate at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, shared his thoughts on the study in an interview and noted some limitations. “The findings of this study do not conflict with what is generally believed, but there are several issues that complicate interpretation,” he began. “The first is how gout is diagnosed. Since crystal presence confirmation is rare in clinical practice, and by assumption of the database used, diagnosis is based on fulfillment of a certain number of criteria, one of which is hyperuricemia – this is not actual confirmation of diagnosis.”

He pointed out that the incidence of gout depends on who received treatment, and the study excluded those who were not receiving treatment and those who were not prescribed allopurinol or febuxostat. “Single parents were also excluded, and this may also have affected results.

“Overweight and obesity were not adjusted for age, and the interpretation is age dependent,” he added. “It really comes down to the way gout is diagnosed, and this is a worldwide problem because the diagnosis has been so dumbed down that we don’t really know what is claimed as gout.”

Dr. Kim and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abhishek has received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca and Oxford Immunotech and personal fees from UpToDate, Springer, Cadilla Pharmaceuticals, NGM Bio, Limbic, and Inflazome. Dr. Rothschild disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gout-associated genetic factors increase the risk of gout by nearly two and a half times among people with a close family history of the disease. The risk is approximately three times higher among people with a family history of gout who are also heavy drinkers; for people with a family history of gout who are also overweight, the risk is four times higher, according to a large population-based study from South Korea.

The increased familial risk of gout (hazard ratio, 2.42) dropped only slightly after adjustment for lifestyle and biological risk factors (HR, 2.29), suggesting that genes are the key drivers for the risk of gout among first-degree relatives.

Risk was highest among individuals with an affected brother (HR, 3.00), followed by father (HR, 2.33), sister (HR, 1.97), and mother (HR, 1.68).

“Although the familial aggregation of gout [where a first-degree relative has the disease] is influenced by both genetic and lifestyle/biological factors, our findings suggest that a genetic predisposition is the predominant driver of familial aggregation,” first author Kyoung-Hoon Kim, PhD, from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Wonju-si, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care and Research.

However, lifestyle is still important, as suggested by comparisons with members of the general population who do not have a family history of gout or a high body mass index (BMI). The risk increased for persons with a family history of gout who were also overweight (HR, 4.39), and it increased further for people with obesity (HR, 6.62), suggesting a dose-response interaction, the authors wrote.

When family history was combined with heavy alcohol consumption, the risk rose (HR, 2.95) in comparison with the general population who had neither risk factor.

The study fills a gap in evidence on “familial risk of gout as opposed to hereditary risk of gout, which has long been recognized,” the researchers wrote.

In addition, the findings suggest the possibility of a dose-dependent gene-environment interaction, “as the combination of both a family history of gout and either high BMI or heavy alcohol consumption was associated with a markedly increased risk of disease, which was even further elevated among obese individuals.”

Abhishek Abhishek, MD, professor of rheumatology and honorary consultant rheumatologist at Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, reflected on the minimal attenuation after adjustment for lifestyle and demographic factors. “This suggests that most of the familial impact is, in fact, genetic rather than due to shared environmental factors and is an important finding.”

He said in an interview that the findings also confirmed the synergistic effect of genetic and lifestyle factors in causing gout. “Lifestyle factors such as alcohol excess and obesity should be addressed more aggressively in those with a first-degree relative with gout.

“Although not directly evaluated in this study, aggressive management of excess weight and high alcohol consumption may prevent the onset of gout or improve its outcomes in those who already have this condition,” he added.

Study of over 5 million individuals with familial aggregation of gout

The researchers drew on data from the government-operated mandatory insurance service that provides for South Korea’s entire population of over 50 million people (the National Health Insurance database), as well as the National Health Screening Program database. Information on familial relationships and risk factor data were identified for 5,524,403 individuals from 2002 to 2018 who had a blood-related first-degree relative.

Familial risk was calculated by comparing the risk of individuals with and those without affected first-degree relatives. Interactions between family history and obesity or alcohol consumption were assessed using a scale that measured gout risk due to interaction of two factors.

Initially, adjustments to familial risk were made with respect to age and sex. Subsequently, possible risk factors included smoking, BMI, hypertension, and hyperglycemia.

Alcohol consumption levels were noted and categorized as nondrinker, moderate drinker, or heavy drinker, with different consumption levels for men and women. For men, heavy drinking was defined as having at least two drinks per week and at least five drinks on any day; for women, heavy drinking was defined as having at least two drinks per week and at least four drinks on any day.

Overweight and obesity were determined on the basis of BMI, using standard categories: overweight was defined as BMI of 25 to less than 30 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as BMI of 30 or higher.

Dr. Kim and coauthors noted that both high BMI and heavy drinking were associated with an increased risk of gout, regardless of whether there was a family history of the disease, and that the findings suggest “a dose-dependent interactive relationship in which genetic factors and obesity potentiate each other rather than operating independently.”

People who are both overweight and have a family history of disease had a combined risk of gout that was significantly higher than the sum of their individual risk factors (HR, 4.39 vs. 3.43). This risk was accentuated among people with obesity (HR, 6.62 vs. 4.74) and was more pronounced in men than in women.

In other risk analyses in which familial and nonfamilial gout risk groups were compared, the risk associated with obesity was higher in the familial, compared with the nonfamilial group (HR, 5.50 vs. 5.36).

Bruce Rothschild, MD, a rheumatologist with Indiana University Health, Muncie, and research associate at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, shared his thoughts on the study in an interview and noted some limitations. “The findings of this study do not conflict with what is generally believed, but there are several issues that complicate interpretation,” he began. “The first is how gout is diagnosed. Since crystal presence confirmation is rare in clinical practice, and by assumption of the database used, diagnosis is based on fulfillment of a certain number of criteria, one of which is hyperuricemia – this is not actual confirmation of diagnosis.”

He pointed out that the incidence of gout depends on who received treatment, and the study excluded those who were not receiving treatment and those who were not prescribed allopurinol or febuxostat. “Single parents were also excluded, and this may also have affected results.

“Overweight and obesity were not adjusted for age, and the interpretation is age dependent,” he added. “It really comes down to the way gout is diagnosed, and this is a worldwide problem because the diagnosis has been so dumbed down that we don’t really know what is claimed as gout.”

Dr. Kim and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abhishek has received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca and Oxford Immunotech and personal fees from UpToDate, Springer, Cadilla Pharmaceuticals, NGM Bio, Limbic, and Inflazome. Dr. Rothschild disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gout-associated genetic factors increase the risk of gout by nearly two and a half times among people with a close family history of the disease. The risk is approximately three times higher among people with a family history of gout who are also heavy drinkers; for people with a family history of gout who are also overweight, the risk is four times higher, according to a large population-based study from South Korea.

The increased familial risk of gout (hazard ratio, 2.42) dropped only slightly after adjustment for lifestyle and biological risk factors (HR, 2.29), suggesting that genes are the key drivers for the risk of gout among first-degree relatives.

Risk was highest among individuals with an affected brother (HR, 3.00), followed by father (HR, 2.33), sister (HR, 1.97), and mother (HR, 1.68).

“Although the familial aggregation of gout [where a first-degree relative has the disease] is influenced by both genetic and lifestyle/biological factors, our findings suggest that a genetic predisposition is the predominant driver of familial aggregation,” first author Kyoung-Hoon Kim, PhD, from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Wonju-si, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care and Research.

However, lifestyle is still important, as suggested by comparisons with members of the general population who do not have a family history of gout or a high body mass index (BMI). The risk increased for persons with a family history of gout who were also overweight (HR, 4.39), and it increased further for people with obesity (HR, 6.62), suggesting a dose-response interaction, the authors wrote.

When family history was combined with heavy alcohol consumption, the risk rose (HR, 2.95) in comparison with the general population who had neither risk factor.

The study fills a gap in evidence on “familial risk of gout as opposed to hereditary risk of gout, which has long been recognized,” the researchers wrote.

In addition, the findings suggest the possibility of a dose-dependent gene-environment interaction, “as the combination of both a family history of gout and either high BMI or heavy alcohol consumption was associated with a markedly increased risk of disease, which was even further elevated among obese individuals.”

Abhishek Abhishek, MD, professor of rheumatology and honorary consultant rheumatologist at Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, reflected on the minimal attenuation after adjustment for lifestyle and demographic factors. “This suggests that most of the familial impact is, in fact, genetic rather than due to shared environmental factors and is an important finding.”

He said in an interview that the findings also confirmed the synergistic effect of genetic and lifestyle factors in causing gout. “Lifestyle factors such as alcohol excess and obesity should be addressed more aggressively in those with a first-degree relative with gout.

“Although not directly evaluated in this study, aggressive management of excess weight and high alcohol consumption may prevent the onset of gout or improve its outcomes in those who already have this condition,” he added.

Study of over 5 million individuals with familial aggregation of gout

The researchers drew on data from the government-operated mandatory insurance service that provides for South Korea’s entire population of over 50 million people (the National Health Insurance database), as well as the National Health Screening Program database. Information on familial relationships and risk factor data were identified for 5,524,403 individuals from 2002 to 2018 who had a blood-related first-degree relative.

Familial risk was calculated by comparing the risk of individuals with and those without affected first-degree relatives. Interactions between family history and obesity or alcohol consumption were assessed using a scale that measured gout risk due to interaction of two factors.

Initially, adjustments to familial risk were made with respect to age and sex. Subsequently, possible risk factors included smoking, BMI, hypertension, and hyperglycemia.

Alcohol consumption levels were noted and categorized as nondrinker, moderate drinker, or heavy drinker, with different consumption levels for men and women. For men, heavy drinking was defined as having at least two drinks per week and at least five drinks on any day; for women, heavy drinking was defined as having at least two drinks per week and at least four drinks on any day.

Overweight and obesity were determined on the basis of BMI, using standard categories: overweight was defined as BMI of 25 to less than 30 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as BMI of 30 or higher.

Dr. Kim and coauthors noted that both high BMI and heavy drinking were associated with an increased risk of gout, regardless of whether there was a family history of the disease, and that the findings suggest “a dose-dependent interactive relationship in which genetic factors and obesity potentiate each other rather than operating independently.”

People who are both overweight and have a family history of disease had a combined risk of gout that was significantly higher than the sum of their individual risk factors (HR, 4.39 vs. 3.43). This risk was accentuated among people with obesity (HR, 6.62 vs. 4.74) and was more pronounced in men than in women.

In other risk analyses in which familial and nonfamilial gout risk groups were compared, the risk associated with obesity was higher in the familial, compared with the nonfamilial group (HR, 5.50 vs. 5.36).

Bruce Rothschild, MD, a rheumatologist with Indiana University Health, Muncie, and research associate at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, shared his thoughts on the study in an interview and noted some limitations. “The findings of this study do not conflict with what is generally believed, but there are several issues that complicate interpretation,” he began. “The first is how gout is diagnosed. Since crystal presence confirmation is rare in clinical practice, and by assumption of the database used, diagnosis is based on fulfillment of a certain number of criteria, one of which is hyperuricemia – this is not actual confirmation of diagnosis.”

He pointed out that the incidence of gout depends on who received treatment, and the study excluded those who were not receiving treatment and those who were not prescribed allopurinol or febuxostat. “Single parents were also excluded, and this may also have affected results.

“Overweight and obesity were not adjusted for age, and the interpretation is age dependent,” he added. “It really comes down to the way gout is diagnosed, and this is a worldwide problem because the diagnosis has been so dumbed down that we don’t really know what is claimed as gout.”

Dr. Kim and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abhishek has received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca and Oxford Immunotech and personal fees from UpToDate, Springer, Cadilla Pharmaceuticals, NGM Bio, Limbic, and Inflazome. Dr. Rothschild disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE AND RESEARCH

No spike in overdose deaths from relaxed buprenorphine regulations

Researchers say the data add weight to the argument for permanently adopting the pandemic-era prescribing regulations for buprenorphine, a treatment for opioid use disorder.

“We saw no evidence that increased availability of buprenorphine through the loosening of rules around prescribing and dispensing of buprenorphine during the pandemic increased overdose deaths,” investigator Wilson Compton, MD, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, told this news organization.

“This is reassuring that, even when we opened up the doors to easier access to buprenorphine, we didn’t see that most serious consequence,” Dr. Compton said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open .

Cause and effect

Federal agencies relaxed prescribing regulations for buprenorphine in March 2020 to make it easier for clinicians to prescribe the drug via telemedicine and for patients to take the medication at home.

The number of buprenorphine prescriptions has increased since that change, with more than 1 million people receiving the medication in 2021 from retail pharmacies in the United States.

However, questions remained about whether increased access would lead to an increase in buprenorphine-involved overdose.

Researchers with NIDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, a CDC database that combines medical examiner and coroner reports and postmortem toxicology testing.

The study included information about overdose deaths from July 2019 to June 2021 in 46 states and the District of Columbia.

Between July 2019 and June 2021, there were 1,955 buprenorphine-involved overdose deaths, which accounted for 2.2% of all drug overdose deaths and 2.6% of opioid-involved overdose deaths.

However, researchers went beyond overall numbers and evaluated details from coroner’s and medical examiner reports, something they had not done before.

“For the first time we looked at the characteristics of decedents from buprenorphine because this has not been studied in this type of detail with a near-national sample,” Dr. Compton said.

“That allowed us to look at patterns of use of other substances as well as the circumstances that are recorded at the death scene that are in the data set,” he added.

Important insights

Reports from nearly all buprenorphine-involved deaths included the presence of at least one other drug, compared with opioid overdose deaths that typically involved only one drug.

“This is consistent with the pharmacology of buprenorphine being a partial agonist, so it may not be as fatal all by itself as some of the other opioids,” Dr. Compton said.

Deaths involving buprenorphine were less likely to include illicitly manufactured fentanyls, and other prescription medications were more often found on the scene, such as antidepressants.

Compared with opioid decedents, buprenorphine decedents were more likely to be women, age 35-44, White, and receiving treatment for mental health conditions, including for substance use disorder (SUD).

These kinds of characteristics provide important insights about potential ways to improve safety and clinical outcomes, Dr. Compton noted.

“When we see things like a little higher rate of SUD treatment and this evidence of other prescription drugs on the scene, and some higher rates of antidepressants in these decedents than I might have expected, I’m very curious about their use of other medical services outside of substance use treatment, because that might be a place where some interventions could be implemented,” he said.

A similar study showed pandemic-era policy changes that allowed methadone to be taken at home was followed by a decrease in methadone-related overdose deaths.

The new findings are consistent with those results, Dr. Compton said.

‘Chipping away’ at stigma

Commenting on the study, O. Trent Hall, DO, assistant professor of addiction medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said that, although he welcomed the findings, they aren’t unexpected.

“Buprenorphine is well established as a safe and effective medication for opioid use disorder and as a physician who routinely cares for patients in the hospital after opioid overdose, I am not at all surprised by these results,” said Dr. Hall, who was not involved with the research.

“When my patients leave the hospital with a buprenorphine prescription, they are much less likely to return with another overdose or serious opioid-related medical problem,” he added.

U.S. drug overdose deaths topped 100,000 for the first time in 2021, and most were opioid-related. Although the latest data from the CDC shows drug overdose deaths have been declining slowly since early 2022, the numbers remain high.

Buprenorphine is one of only two drugs known to reduce the risk of opioid overdose. While prescriptions have increased since 2020, the medication remains underutilized, despite its known effectiveness in treating opioid use disorder.

Dr. Hall noted that research such as the new study could help increase buprenorphine’s use.

“Studies like this one chip away at the stigma that has been misapplied to buprenorphine,” he said. “I hope this article will encourage more providers to offer buprenorphine to patients with opioid use disorder.”

The study was funded internally by NIDA and the CDC. Dr. Compton reported owning stock in General Electric, 3M, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr. Hall has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers say the data add weight to the argument for permanently adopting the pandemic-era prescribing regulations for buprenorphine, a treatment for opioid use disorder.

“We saw no evidence that increased availability of buprenorphine through the loosening of rules around prescribing and dispensing of buprenorphine during the pandemic increased overdose deaths,” investigator Wilson Compton, MD, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, told this news organization.

“This is reassuring that, even when we opened up the doors to easier access to buprenorphine, we didn’t see that most serious consequence,” Dr. Compton said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open .

Cause and effect

Federal agencies relaxed prescribing regulations for buprenorphine in March 2020 to make it easier for clinicians to prescribe the drug via telemedicine and for patients to take the medication at home.

The number of buprenorphine prescriptions has increased since that change, with more than 1 million people receiving the medication in 2021 from retail pharmacies in the United States.

However, questions remained about whether increased access would lead to an increase in buprenorphine-involved overdose.

Researchers with NIDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, a CDC database that combines medical examiner and coroner reports and postmortem toxicology testing.

The study included information about overdose deaths from July 2019 to June 2021 in 46 states and the District of Columbia.

Between July 2019 and June 2021, there were 1,955 buprenorphine-involved overdose deaths, which accounted for 2.2% of all drug overdose deaths and 2.6% of opioid-involved overdose deaths.

However, researchers went beyond overall numbers and evaluated details from coroner’s and medical examiner reports, something they had not done before.

“For the first time we looked at the characteristics of decedents from buprenorphine because this has not been studied in this type of detail with a near-national sample,” Dr. Compton said.

“That allowed us to look at patterns of use of other substances as well as the circumstances that are recorded at the death scene that are in the data set,” he added.

Important insights

Reports from nearly all buprenorphine-involved deaths included the presence of at least one other drug, compared with opioid overdose deaths that typically involved only one drug.

“This is consistent with the pharmacology of buprenorphine being a partial agonist, so it may not be as fatal all by itself as some of the other opioids,” Dr. Compton said.

Deaths involving buprenorphine were less likely to include illicitly manufactured fentanyls, and other prescription medications were more often found on the scene, such as antidepressants.

Compared with opioid decedents, buprenorphine decedents were more likely to be women, age 35-44, White, and receiving treatment for mental health conditions, including for substance use disorder (SUD).

These kinds of characteristics provide important insights about potential ways to improve safety and clinical outcomes, Dr. Compton noted.

“When we see things like a little higher rate of SUD treatment and this evidence of other prescription drugs on the scene, and some higher rates of antidepressants in these decedents than I might have expected, I’m very curious about their use of other medical services outside of substance use treatment, because that might be a place where some interventions could be implemented,” he said.

A similar study showed pandemic-era policy changes that allowed methadone to be taken at home was followed by a decrease in methadone-related overdose deaths.

The new findings are consistent with those results, Dr. Compton said.

‘Chipping away’ at stigma

Commenting on the study, O. Trent Hall, DO, assistant professor of addiction medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said that, although he welcomed the findings, they aren’t unexpected.

“Buprenorphine is well established as a safe and effective medication for opioid use disorder and as a physician who routinely cares for patients in the hospital after opioid overdose, I am not at all surprised by these results,” said Dr. Hall, who was not involved with the research.

“When my patients leave the hospital with a buprenorphine prescription, they are much less likely to return with another overdose or serious opioid-related medical problem,” he added.

U.S. drug overdose deaths topped 100,000 for the first time in 2021, and most were opioid-related. Although the latest data from the CDC shows drug overdose deaths have been declining slowly since early 2022, the numbers remain high.

Buprenorphine is one of only two drugs known to reduce the risk of opioid overdose. While prescriptions have increased since 2020, the medication remains underutilized, despite its known effectiveness in treating opioid use disorder.

Dr. Hall noted that research such as the new study could help increase buprenorphine’s use.

“Studies like this one chip away at the stigma that has been misapplied to buprenorphine,” he said. “I hope this article will encourage more providers to offer buprenorphine to patients with opioid use disorder.”

The study was funded internally by NIDA and the CDC. Dr. Compton reported owning stock in General Electric, 3M, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr. Hall has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers say the data add weight to the argument for permanently adopting the pandemic-era prescribing regulations for buprenorphine, a treatment for opioid use disorder.

“We saw no evidence that increased availability of buprenorphine through the loosening of rules around prescribing and dispensing of buprenorphine during the pandemic increased overdose deaths,” investigator Wilson Compton, MD, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, told this news organization.

“This is reassuring that, even when we opened up the doors to easier access to buprenorphine, we didn’t see that most serious consequence,” Dr. Compton said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open .

Cause and effect

Federal agencies relaxed prescribing regulations for buprenorphine in March 2020 to make it easier for clinicians to prescribe the drug via telemedicine and for patients to take the medication at home.

The number of buprenorphine prescriptions has increased since that change, with more than 1 million people receiving the medication in 2021 from retail pharmacies in the United States.

However, questions remained about whether increased access would lead to an increase in buprenorphine-involved overdose.

Researchers with NIDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, a CDC database that combines medical examiner and coroner reports and postmortem toxicology testing.

The study included information about overdose deaths from July 2019 to June 2021 in 46 states and the District of Columbia.

Between July 2019 and June 2021, there were 1,955 buprenorphine-involved overdose deaths, which accounted for 2.2% of all drug overdose deaths and 2.6% of opioid-involved overdose deaths.

However, researchers went beyond overall numbers and evaluated details from coroner’s and medical examiner reports, something they had not done before.

“For the first time we looked at the characteristics of decedents from buprenorphine because this has not been studied in this type of detail with a near-national sample,” Dr. Compton said.

“That allowed us to look at patterns of use of other substances as well as the circumstances that are recorded at the death scene that are in the data set,” he added.

Important insights

Reports from nearly all buprenorphine-involved deaths included the presence of at least one other drug, compared with opioid overdose deaths that typically involved only one drug.

“This is consistent with the pharmacology of buprenorphine being a partial agonist, so it may not be as fatal all by itself as some of the other opioids,” Dr. Compton said.

Deaths involving buprenorphine were less likely to include illicitly manufactured fentanyls, and other prescription medications were more often found on the scene, such as antidepressants.

Compared with opioid decedents, buprenorphine decedents were more likely to be women, age 35-44, White, and receiving treatment for mental health conditions, including for substance use disorder (SUD).

These kinds of characteristics provide important insights about potential ways to improve safety and clinical outcomes, Dr. Compton noted.

“When we see things like a little higher rate of SUD treatment and this evidence of other prescription drugs on the scene, and some higher rates of antidepressants in these decedents than I might have expected, I’m very curious about their use of other medical services outside of substance use treatment, because that might be a place where some interventions could be implemented,” he said.

A similar study showed pandemic-era policy changes that allowed methadone to be taken at home was followed by a decrease in methadone-related overdose deaths.

The new findings are consistent with those results, Dr. Compton said.

‘Chipping away’ at stigma

Commenting on the study, O. Trent Hall, DO, assistant professor of addiction medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said that, although he welcomed the findings, they aren’t unexpected.

“Buprenorphine is well established as a safe and effective medication for opioid use disorder and as a physician who routinely cares for patients in the hospital after opioid overdose, I am not at all surprised by these results,” said Dr. Hall, who was not involved with the research.

“When my patients leave the hospital with a buprenorphine prescription, they are much less likely to return with another overdose or serious opioid-related medical problem,” he added.

U.S. drug overdose deaths topped 100,000 for the first time in 2021, and most were opioid-related. Although the latest data from the CDC shows drug overdose deaths have been declining slowly since early 2022, the numbers remain high.

Buprenorphine is one of only two drugs known to reduce the risk of opioid overdose. While prescriptions have increased since 2020, the medication remains underutilized, despite its known effectiveness in treating opioid use disorder.

Dr. Hall noted that research such as the new study could help increase buprenorphine’s use.

“Studies like this one chip away at the stigma that has been misapplied to buprenorphine,” he said. “I hope this article will encourage more providers to offer buprenorphine to patients with opioid use disorder.”

The study was funded internally by NIDA and the CDC. Dr. Compton reported owning stock in General Electric, 3M, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr. Hall has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Keeping physician stress in check

Fahri Saatcioglu, PhD, and colleagues, whose report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, described it as a “dire situation” with resolutions needed “urgently” to “mitigate the negative consequences of physician burnout.” Both individual and whole-system approaches are needed, wrote Dr. Saatcioglu, a researcher with Oslo University Hospital in Norway who reviewed well-being interventions designed to mitigate physician stress.

When burnout sets in it is marked by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a lack of confidence in one’s ability to do his or her job effectively (often because of lack of support or organizational constraints). It can lead to reduced work efficacy, medical errors, job dissatisfaction, and turnover, Fay J. Hlubocky, PhD, and colleagues, wrote in a report published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients postponed doctor visits and procedures. Telemedicine was adopted in place of in-person visits, surgeries were delayed, and oral chemotherapy was prescribed over intravenous therapies, wrote Dr. Hlubocky and colleagues, who addressed the heightened sense of burnout oncologists experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But before the pandemic, oncologists were already overburdened by a system unable to meet the demand for services. And now, because patients delayed doctor visits, more patients are being diagnosed with advanced malignancies.

According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the demand for cancer-related services is expected to grow by 40% over the next 6 years. And, by 2025, there will be a shortage of more than 2,200 oncologists in the United States.

Addressing physician burnout can affect the bottom line. According to a report published in Annals of Internal Medicine, physician turnover and reduced clinical hours due to burnout costs the United States $4.6 billion each year.

“It is estimated that 30%-50% of physicians either have burnout symptoms or they experience burnout. A recent study on oncologists in Canada found that symptoms of burnout may reach 73%,” wrote Dr. Saatcioglu and colleagues. “It is clear, for example, that an appropriate workload, resource sufficiency, positive work culture and values, and sufficient social and community support are all very critical for a sustainable and successful health care organization. All of these are also required for the professional satisfaction and well-being of physicians.”

Physician stress has become so serious, that Dr. Saatcioglu and colleagues recommend that hospital administrators “firmly establish the culture of wellness at the workplace” by including physician wellness under the institutional initiatives umbrella. Hospital leadership, they wrote, should strive to mitigate burnout at all levels by addressing issues and adopting strategies for physicians as a workforce and as individuals.

“There is a distinct need to approach the personal needs of the physician as an individual who is experiencing chronic stress that can trigger psychologic symptoms, which further affects not only their own health, family life, etc., but also their clinical performance, quality of the resulting health care, patient satisfaction, and finally the health economy,” the authors wrote.

Some health care organizations have adopted programs and made institutional changes designed to reduce burnout for health care workers. These include online wellness programs both free and paid, but there is little data on the efficacy of these programs.