User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, potential lifesavers in bipolar disorder

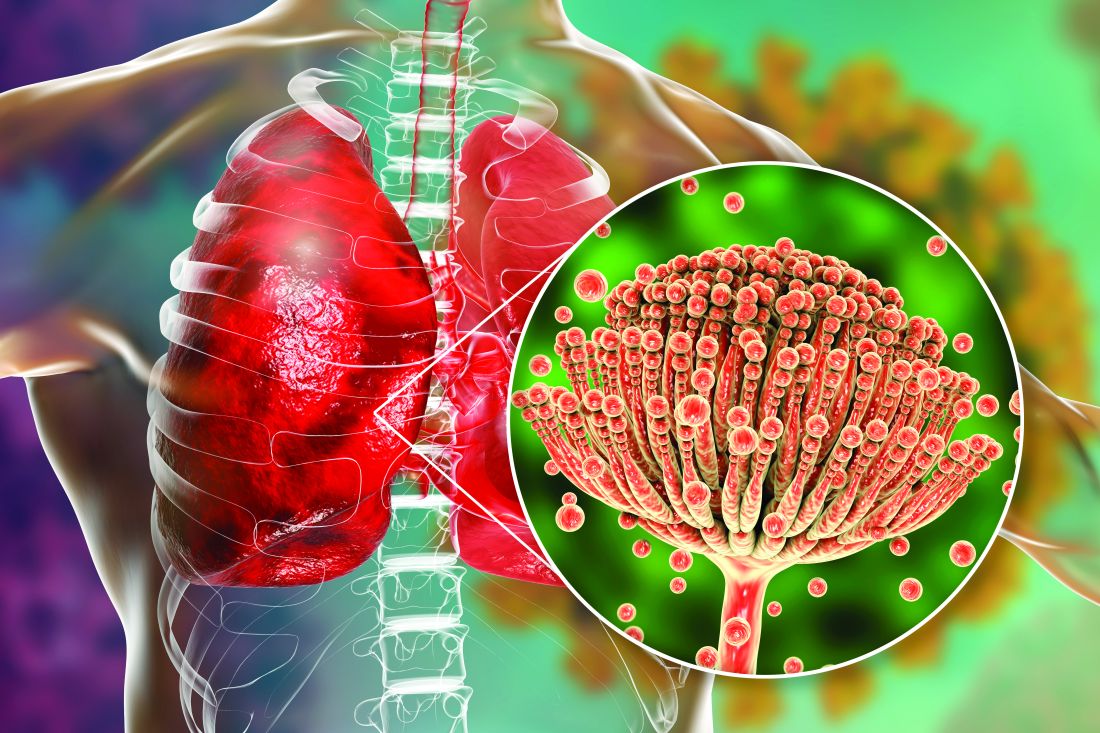

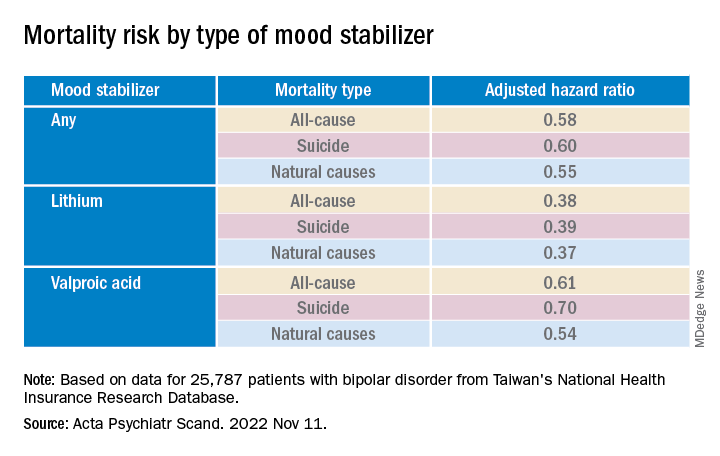

Investigators led by Pao-Huan Chen, MD, of the department of psychiatry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, evaluated the association between the use of mood stabilizers and the risks for all-cause mortality, suicide, and natural mortality in more than 25,000 patients with BD and found that those with BD had higher mortality.

However, they also found that patients with BD had a significantly decreased adjusted 5-year risk of dying from any cause, suicide, and natural causes. Lithium was associated with the largest risk reduction compared with the other mood stabilizers.

“The present findings highlight the potential role of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, in reducing mortality among patients with bipolar disorder,” the authors write.

“The findings of this study could inform future clinical and mechanistic research evaluating the multifaceted effects of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, on the psychological and physiological statuses of patients with bipolar disorder,” they add.

The study was published online in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Research gap

Patients with BD have an elevated risk for multiple comorbidities in addition to mood symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction, with previous research suggesting a mortality rate due to suicide and natural causes that is at least twice as high as that of the general population, the authors write.

Lithium, in particular, has been associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality and suicide in patients with BD, but findings regarding anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have been “inconsistent.”

To fill this research gap, the researchers evaluated 16 years of data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes information about more than 23 million residents of Taiwan. The current study, which encompassed 25,787 patients with BD, looked at data from the 5-year period after index hospitalization.

The researchers hypothesized that mood stabilizers “would decrease the risk of mortality” among patients with BD and that “different mood stabilizers would exhibit different associations with mortality, owing to their varying effects on mood symptoms and physiological function.”

Covariates included sex, age, employment status, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs.

Of the patients with BD, 4,000 died within the 5-year period. Suicide and natural causes accounted for 19.0% and 73.7% of these deaths, respectively.

Cardioprotective effects?

The standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) – the ratios of observed mortality in the BD cohort to the number of expected deaths in the general population – were 5.26 for all causes (95% confidence interval, 5.10-5.43), 26.02 for suicide (95% CI, 24.20-27.93), and 4.68 for natural causes (95% CI, 4.51-4.85).

The cumulative mortality rate was higher among men vs. women, a difference that was even larger among patients who had died from any cause or natural causes (crude hazard ratios, .60 and .52, respectively; both Ps < .001).

The suicide risk peaked between ages 45 and 65 years, whereas the risks for all-cause and natural mortality increased with age and were highest in those older than 65 years.

Patients who had died from any cause or from natural causes had a higher risk for physical and psychiatric comorbidities, whereas those who had died by suicide had a higher risk for primarily psychiatric comorbidities.

Mood stabilizers were associated with decreased risks for all-cause mortality and natural mortality, with lithium and valproic acid tied to the lowest risk for all three mortality types (all Ps < .001).

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine were “not significantly associated with any type of mortality,” the authors report.

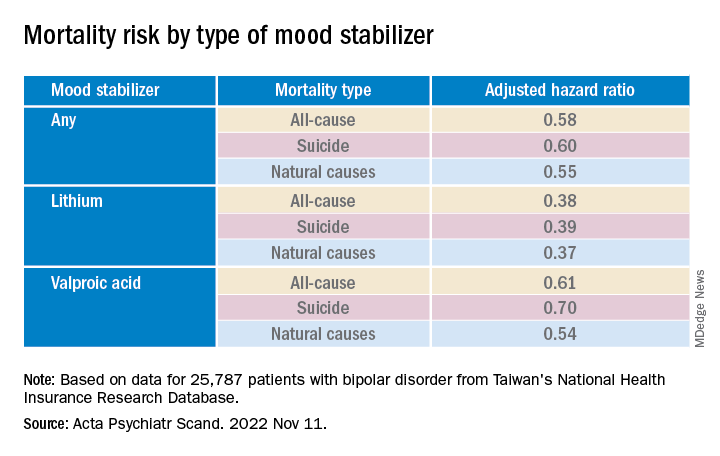

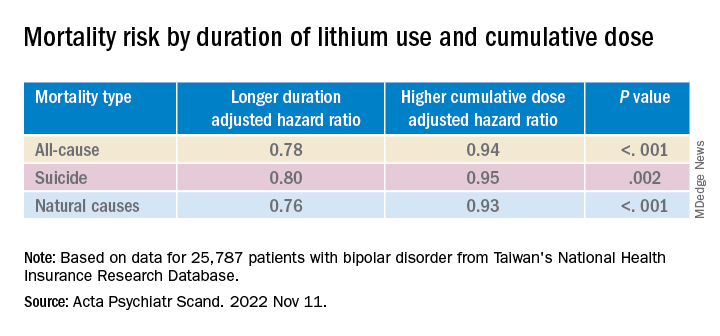

Longer duration of lithium use and a higher cumulative dose of lithium were both associated with lower risks for all three types of mortality (all Ps < .001).

Valproic acid was associated with dose-dependent decreases in all-cause and natural mortality risks.

The findings suggest that mood stabilizers “may improve not only psychosocial outcomes but also the physical health of patients with BD,” the investigators note.

The association between mood stabilizer use and reduced natural mortality risk “may be attributable to the potential benefits of psychiatric care” but may also “have resulted from the direct effects of mood stabilizers on physiological functions,” they add.

Some research suggests lithium treatment may reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with BD. Mechanistic studies have also pointed to potential cardioprotective effects from valproic acid.

The authors note several study limitations. Focusing on hospitalized patients “may have led to selection bias and overestimated mortality risk.” Moreover, the analyses were “based on the prescription, not the consumption, of mood stabilizers” and information regarding adherence was unavailable.

The absence of a protective mechanism of lamotrigine and carbamazepine may be attributable to “bias toward the relatively poor treatment responses” of these agents, neither of which is used as a first-line medication to treat BD in Taiwan. Patients taking these agents “may not receive medical care at a level equal to those taking lithium, who tend to receive closer surveillance, owing to the narrow therapeutic index.”

First-line treatment

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the data “add to a growing confluence of data from observational studies indicating that lithium especially is capable of reducing all-cause mortality, suicide mortality, and natural mortality.”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, agreed with the authors that lamotrigine is “not a very popular drug in Taiwan, therefore we may not have sufficient assay sensitivity to document the effect.”

But lamotrigine “does have recurrence prevention effects in BD, especially bipolar depression, and it would be expected that it would reduce suicide potentially especially in such a large sample.”

The study’s take-home message “is that the extant evidence now indicates that lithium should be a first-line treatment in persons who live with BD who are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or behavior and these data should inform algorithms of treatment selection and sequencing in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. McIntyre.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan and Taipei City Hospital. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators led by Pao-Huan Chen, MD, of the department of psychiatry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, evaluated the association between the use of mood stabilizers and the risks for all-cause mortality, suicide, and natural mortality in more than 25,000 patients with BD and found that those with BD had higher mortality.

However, they also found that patients with BD had a significantly decreased adjusted 5-year risk of dying from any cause, suicide, and natural causes. Lithium was associated with the largest risk reduction compared with the other mood stabilizers.

“The present findings highlight the potential role of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, in reducing mortality among patients with bipolar disorder,” the authors write.

“The findings of this study could inform future clinical and mechanistic research evaluating the multifaceted effects of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, on the psychological and physiological statuses of patients with bipolar disorder,” they add.

The study was published online in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Research gap

Patients with BD have an elevated risk for multiple comorbidities in addition to mood symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction, with previous research suggesting a mortality rate due to suicide and natural causes that is at least twice as high as that of the general population, the authors write.

Lithium, in particular, has been associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality and suicide in patients with BD, but findings regarding anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have been “inconsistent.”

To fill this research gap, the researchers evaluated 16 years of data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes information about more than 23 million residents of Taiwan. The current study, which encompassed 25,787 patients with BD, looked at data from the 5-year period after index hospitalization.

The researchers hypothesized that mood stabilizers “would decrease the risk of mortality” among patients with BD and that “different mood stabilizers would exhibit different associations with mortality, owing to their varying effects on mood symptoms and physiological function.”

Covariates included sex, age, employment status, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs.

Of the patients with BD, 4,000 died within the 5-year period. Suicide and natural causes accounted for 19.0% and 73.7% of these deaths, respectively.

Cardioprotective effects?

The standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) – the ratios of observed mortality in the BD cohort to the number of expected deaths in the general population – were 5.26 for all causes (95% confidence interval, 5.10-5.43), 26.02 for suicide (95% CI, 24.20-27.93), and 4.68 for natural causes (95% CI, 4.51-4.85).

The cumulative mortality rate was higher among men vs. women, a difference that was even larger among patients who had died from any cause or natural causes (crude hazard ratios, .60 and .52, respectively; both Ps < .001).

The suicide risk peaked between ages 45 and 65 years, whereas the risks for all-cause and natural mortality increased with age and were highest in those older than 65 years.

Patients who had died from any cause or from natural causes had a higher risk for physical and psychiatric comorbidities, whereas those who had died by suicide had a higher risk for primarily psychiatric comorbidities.

Mood stabilizers were associated with decreased risks for all-cause mortality and natural mortality, with lithium and valproic acid tied to the lowest risk for all three mortality types (all Ps < .001).

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine were “not significantly associated with any type of mortality,” the authors report.

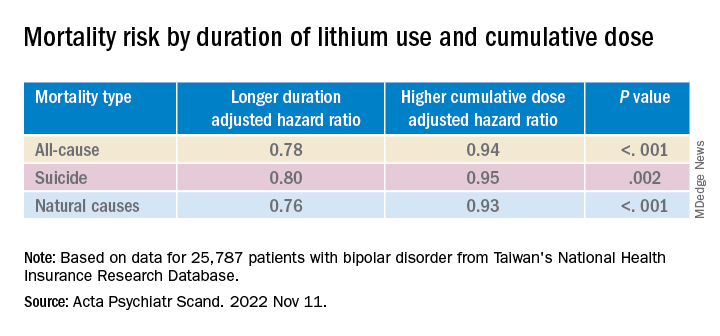

Longer duration of lithium use and a higher cumulative dose of lithium were both associated with lower risks for all three types of mortality (all Ps < .001).

Valproic acid was associated with dose-dependent decreases in all-cause and natural mortality risks.

The findings suggest that mood stabilizers “may improve not only psychosocial outcomes but also the physical health of patients with BD,” the investigators note.

The association between mood stabilizer use and reduced natural mortality risk “may be attributable to the potential benefits of psychiatric care” but may also “have resulted from the direct effects of mood stabilizers on physiological functions,” they add.

Some research suggests lithium treatment may reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with BD. Mechanistic studies have also pointed to potential cardioprotective effects from valproic acid.

The authors note several study limitations. Focusing on hospitalized patients “may have led to selection bias and overestimated mortality risk.” Moreover, the analyses were “based on the prescription, not the consumption, of mood stabilizers” and information regarding adherence was unavailable.

The absence of a protective mechanism of lamotrigine and carbamazepine may be attributable to “bias toward the relatively poor treatment responses” of these agents, neither of which is used as a first-line medication to treat BD in Taiwan. Patients taking these agents “may not receive medical care at a level equal to those taking lithium, who tend to receive closer surveillance, owing to the narrow therapeutic index.”

First-line treatment

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the data “add to a growing confluence of data from observational studies indicating that lithium especially is capable of reducing all-cause mortality, suicide mortality, and natural mortality.”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, agreed with the authors that lamotrigine is “not a very popular drug in Taiwan, therefore we may not have sufficient assay sensitivity to document the effect.”

But lamotrigine “does have recurrence prevention effects in BD, especially bipolar depression, and it would be expected that it would reduce suicide potentially especially in such a large sample.”

The study’s take-home message “is that the extant evidence now indicates that lithium should be a first-line treatment in persons who live with BD who are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or behavior and these data should inform algorithms of treatment selection and sequencing in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. McIntyre.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan and Taipei City Hospital. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

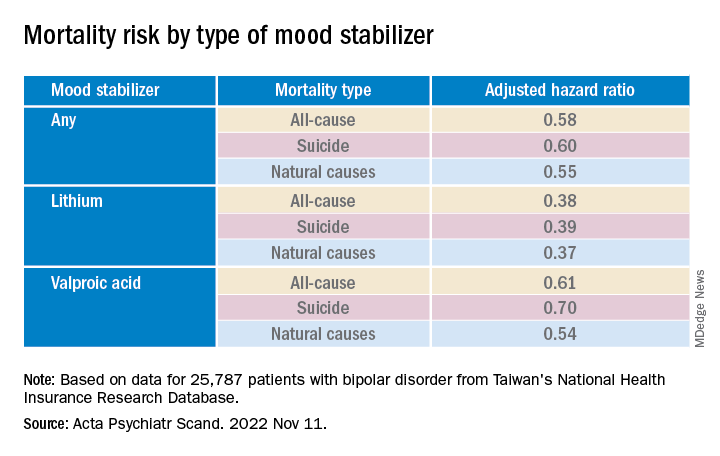

Investigators led by Pao-Huan Chen, MD, of the department of psychiatry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, evaluated the association between the use of mood stabilizers and the risks for all-cause mortality, suicide, and natural mortality in more than 25,000 patients with BD and found that those with BD had higher mortality.

However, they also found that patients with BD had a significantly decreased adjusted 5-year risk of dying from any cause, suicide, and natural causes. Lithium was associated with the largest risk reduction compared with the other mood stabilizers.

“The present findings highlight the potential role of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, in reducing mortality among patients with bipolar disorder,” the authors write.

“The findings of this study could inform future clinical and mechanistic research evaluating the multifaceted effects of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, on the psychological and physiological statuses of patients with bipolar disorder,” they add.

The study was published online in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Research gap

Patients with BD have an elevated risk for multiple comorbidities in addition to mood symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction, with previous research suggesting a mortality rate due to suicide and natural causes that is at least twice as high as that of the general population, the authors write.

Lithium, in particular, has been associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality and suicide in patients with BD, but findings regarding anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have been “inconsistent.”

To fill this research gap, the researchers evaluated 16 years of data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes information about more than 23 million residents of Taiwan. The current study, which encompassed 25,787 patients with BD, looked at data from the 5-year period after index hospitalization.

The researchers hypothesized that mood stabilizers “would decrease the risk of mortality” among patients with BD and that “different mood stabilizers would exhibit different associations with mortality, owing to their varying effects on mood symptoms and physiological function.”

Covariates included sex, age, employment status, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs.

Of the patients with BD, 4,000 died within the 5-year period. Suicide and natural causes accounted for 19.0% and 73.7% of these deaths, respectively.

Cardioprotective effects?

The standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) – the ratios of observed mortality in the BD cohort to the number of expected deaths in the general population – were 5.26 for all causes (95% confidence interval, 5.10-5.43), 26.02 for suicide (95% CI, 24.20-27.93), and 4.68 for natural causes (95% CI, 4.51-4.85).

The cumulative mortality rate was higher among men vs. women, a difference that was even larger among patients who had died from any cause or natural causes (crude hazard ratios, .60 and .52, respectively; both Ps < .001).

The suicide risk peaked between ages 45 and 65 years, whereas the risks for all-cause and natural mortality increased with age and were highest in those older than 65 years.

Patients who had died from any cause or from natural causes had a higher risk for physical and psychiatric comorbidities, whereas those who had died by suicide had a higher risk for primarily psychiatric comorbidities.

Mood stabilizers were associated with decreased risks for all-cause mortality and natural mortality, with lithium and valproic acid tied to the lowest risk for all three mortality types (all Ps < .001).

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine were “not significantly associated with any type of mortality,” the authors report.

Longer duration of lithium use and a higher cumulative dose of lithium were both associated with lower risks for all three types of mortality (all Ps < .001).

Valproic acid was associated with dose-dependent decreases in all-cause and natural mortality risks.

The findings suggest that mood stabilizers “may improve not only psychosocial outcomes but also the physical health of patients with BD,” the investigators note.

The association between mood stabilizer use and reduced natural mortality risk “may be attributable to the potential benefits of psychiatric care” but may also “have resulted from the direct effects of mood stabilizers on physiological functions,” they add.

Some research suggests lithium treatment may reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with BD. Mechanistic studies have also pointed to potential cardioprotective effects from valproic acid.

The authors note several study limitations. Focusing on hospitalized patients “may have led to selection bias and overestimated mortality risk.” Moreover, the analyses were “based on the prescription, not the consumption, of mood stabilizers” and information regarding adherence was unavailable.

The absence of a protective mechanism of lamotrigine and carbamazepine may be attributable to “bias toward the relatively poor treatment responses” of these agents, neither of which is used as a first-line medication to treat BD in Taiwan. Patients taking these agents “may not receive medical care at a level equal to those taking lithium, who tend to receive closer surveillance, owing to the narrow therapeutic index.”

First-line treatment

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the data “add to a growing confluence of data from observational studies indicating that lithium especially is capable of reducing all-cause mortality, suicide mortality, and natural mortality.”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, agreed with the authors that lamotrigine is “not a very popular drug in Taiwan, therefore we may not have sufficient assay sensitivity to document the effect.”

But lamotrigine “does have recurrence prevention effects in BD, especially bipolar depression, and it would be expected that it would reduce suicide potentially especially in such a large sample.”

The study’s take-home message “is that the extant evidence now indicates that lithium should be a first-line treatment in persons who live with BD who are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or behavior and these data should inform algorithms of treatment selection and sequencing in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. McIntyre.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan and Taipei City Hospital. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACTA PSYCHIATRICA SCANDINAVICA

Have you heard of VEXAS syndrome?

Its name is an acronym: Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic. The prevalence of this syndrome is unknown, but it is not so rare. As it is an X-linked disease, men are predominantly affected.

First identification

The NIH team screened the exomes and genomes of 2,560 individuals. Of this group, 1,477 had been referred because of undiagnosed recurrent fevers, systemic inflammation, or both, and 1,083 were affected by atypical, unclassified disorders. The researchers identified 25 men with a somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 (UBA1) gene, which is involved in the protein ubiquitylation system. This posttranslational modification has a pleiotropic function that likely explains the clinical heterogeneity seen in VEXAS patients: regulation of protein turnover, especially those involved in the cell cycle, cell death, and signal transduction. Ubiquitylation is also involved in nonproteolytic functions, such as assembly of multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, inflammatory signaling, and DNA repair.

Clinical presentation

The clinicobiological presentation of VEXAS syndrome is very heterogeneous. Typically, patients present with a systemic inflammatory disease with unexplained episodes of fever, involvement of the lungs, skin, blood vessels, and joints. Molecular diagnosis is made by the sequencing of UBA1.

Most patients present with the characteristic clinical signs of other inflammatory diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa and recurrent polychondritis. But VEXAS patients are at high risk of developing hematologic conditions. Indeed, the following were seen among the 25 participants in the NIH study: macrocytic anemia (96%), venous thromboembolism (44%), myelodysplastic syndrome (24%), and multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (20%).

In VEXAS patients, levels of serum inflammatory markers are increased. These markers include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-8, interleukin-6, interferon-inducible protein-10, interferon-gamma, C-reactive protein. In addition, there is aberrant activation of innate immune-signaling pathways.

In a large-scale analysis of a multicenter case series of 116 French patients, researchers found that VEXAS syndrome primarily affected men. The disease was progressive, and onset occurred after age 50 years. These patients can be divided into three phenotypically distinct clusters on the basis of integration of clinical and biological data. In the 58 cases in which myelodysplastic syndrome was present, the mortality rates were higher. The researchers also reported that the UBA1 p.Met41L mutation was associated with a better prognosis.

Treatment data

VEXAS syndrome resists the classical therapeutic arsenal. Patients require high-dose glucocorticoids, and prognosis appears to be poor. The available treatment data are retrospective. Of the 25 participants in the NIH study, 40% died within 5 years from disease-related causes or complications related to treatment. Among the promising therapeutic avenues is the use of inhibitors of the Janus kinase pathway.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Its name is an acronym: Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic. The prevalence of this syndrome is unknown, but it is not so rare. As it is an X-linked disease, men are predominantly affected.

First identification

The NIH team screened the exomes and genomes of 2,560 individuals. Of this group, 1,477 had been referred because of undiagnosed recurrent fevers, systemic inflammation, or both, and 1,083 were affected by atypical, unclassified disorders. The researchers identified 25 men with a somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 (UBA1) gene, which is involved in the protein ubiquitylation system. This posttranslational modification has a pleiotropic function that likely explains the clinical heterogeneity seen in VEXAS patients: regulation of protein turnover, especially those involved in the cell cycle, cell death, and signal transduction. Ubiquitylation is also involved in nonproteolytic functions, such as assembly of multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, inflammatory signaling, and DNA repair.

Clinical presentation

The clinicobiological presentation of VEXAS syndrome is very heterogeneous. Typically, patients present with a systemic inflammatory disease with unexplained episodes of fever, involvement of the lungs, skin, blood vessels, and joints. Molecular diagnosis is made by the sequencing of UBA1.

Most patients present with the characteristic clinical signs of other inflammatory diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa and recurrent polychondritis. But VEXAS patients are at high risk of developing hematologic conditions. Indeed, the following were seen among the 25 participants in the NIH study: macrocytic anemia (96%), venous thromboembolism (44%), myelodysplastic syndrome (24%), and multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (20%).

In VEXAS patients, levels of serum inflammatory markers are increased. These markers include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-8, interleukin-6, interferon-inducible protein-10, interferon-gamma, C-reactive protein. In addition, there is aberrant activation of innate immune-signaling pathways.

In a large-scale analysis of a multicenter case series of 116 French patients, researchers found that VEXAS syndrome primarily affected men. The disease was progressive, and onset occurred after age 50 years. These patients can be divided into three phenotypically distinct clusters on the basis of integration of clinical and biological data. In the 58 cases in which myelodysplastic syndrome was present, the mortality rates were higher. The researchers also reported that the UBA1 p.Met41L mutation was associated with a better prognosis.

Treatment data

VEXAS syndrome resists the classical therapeutic arsenal. Patients require high-dose glucocorticoids, and prognosis appears to be poor. The available treatment data are retrospective. Of the 25 participants in the NIH study, 40% died within 5 years from disease-related causes or complications related to treatment. Among the promising therapeutic avenues is the use of inhibitors of the Janus kinase pathway.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Its name is an acronym: Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic. The prevalence of this syndrome is unknown, but it is not so rare. As it is an X-linked disease, men are predominantly affected.

First identification

The NIH team screened the exomes and genomes of 2,560 individuals. Of this group, 1,477 had been referred because of undiagnosed recurrent fevers, systemic inflammation, or both, and 1,083 were affected by atypical, unclassified disorders. The researchers identified 25 men with a somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 (UBA1) gene, which is involved in the protein ubiquitylation system. This posttranslational modification has a pleiotropic function that likely explains the clinical heterogeneity seen in VEXAS patients: regulation of protein turnover, especially those involved in the cell cycle, cell death, and signal transduction. Ubiquitylation is also involved in nonproteolytic functions, such as assembly of multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, inflammatory signaling, and DNA repair.

Clinical presentation

The clinicobiological presentation of VEXAS syndrome is very heterogeneous. Typically, patients present with a systemic inflammatory disease with unexplained episodes of fever, involvement of the lungs, skin, blood vessels, and joints. Molecular diagnosis is made by the sequencing of UBA1.

Most patients present with the characteristic clinical signs of other inflammatory diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa and recurrent polychondritis. But VEXAS patients are at high risk of developing hematologic conditions. Indeed, the following were seen among the 25 participants in the NIH study: macrocytic anemia (96%), venous thromboembolism (44%), myelodysplastic syndrome (24%), and multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (20%).

In VEXAS patients, levels of serum inflammatory markers are increased. These markers include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-8, interleukin-6, interferon-inducible protein-10, interferon-gamma, C-reactive protein. In addition, there is aberrant activation of innate immune-signaling pathways.

In a large-scale analysis of a multicenter case series of 116 French patients, researchers found that VEXAS syndrome primarily affected men. The disease was progressive, and onset occurred after age 50 years. These patients can be divided into three phenotypically distinct clusters on the basis of integration of clinical and biological data. In the 58 cases in which myelodysplastic syndrome was present, the mortality rates were higher. The researchers also reported that the UBA1 p.Met41L mutation was associated with a better prognosis.

Treatment data

VEXAS syndrome resists the classical therapeutic arsenal. Patients require high-dose glucocorticoids, and prognosis appears to be poor. The available treatment data are retrospective. Of the 25 participants in the NIH study, 40% died within 5 years from disease-related causes or complications related to treatment. Among the promising therapeutic avenues is the use of inhibitors of the Janus kinase pathway.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New AHA statement on complementary medicine in heart failure

There are some benefits and potentially serious risks associated with complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) patients with heart failure (HF) may use to manage symptoms, the American Heart Association noted in a new scientific statement on the topic.

For example, yoga and tai chi can be helpful for people with HF, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may also have benefits. However, there are safety concerns with other commonly used over-the-counter CAM therapies, including vitamin D, blue cohosh, and Lily of the Valley, the writing group said.

It’s estimated that roughly one in three patients with HF use CAM. But often patients don’t report their CAM use to their clinicians and clinicians may not routinely ask about CAM use or have the resources to evaluate CAM therapies, writing group chair Sheryl L. Chow, PharmD, told this news organization.

“This represents a major public health problem given that consumers are frequently purchasing these potentially dangerous and minimally regulated products without the knowledge or advice from a health care professional,” said Dr. Chow, of Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, Calif., and University of California, Irvine.

The 27-page statement was published online in Circulation.

CAM use common in HF

The statement defines CAM as medical practices, supplements, and approaches that do not conform to the standards of conventional, evidence-based practice guidelines. CAM products are available without prescriptions or medical guidance at pharmacies, health food stores, and online retailers.

“These agents are largely unregulated by the [Food and Drug Administration] and manufacturers do not need to demonstrate efficacy or safety. It is important that both health care professionals and consumers improve communication with respect to OTC therapies and are educated about potential efficacy and risk of harm so that shared and informed decision-making can occur,” Dr. Chow said.

The writing group reviewed research published before November 2021 on CAM among people with HF.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as fish oil, have the strongest evidence among CAM agents for clinical benefit in HF and may be used safely by patients in moderation and in consultation with their health care team, the writing group said.

Research has shown that omega-3 PUFAs are associated with a lower risk of developing HF as well as improvements in left ventricular systolic function in those with existing HF, they pointed out.

However, two clinical trials found a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation with high-dose omega-3 PUFA administration. “This risk appears to be dose-related and increased when exceeding 2 g/d of fish oil,” the writing group said.

Research suggests that yoga and tai chi, when added to standard HF treatment, may help improve exercise tolerance and quality of life and decrease blood pressure.

Inconclusive or potentially harmful CAM therapies

Other CAM therapies for HF have been shown as ineffective based on current data, have mixed findings, or appear to be harmful. The writers highlighted the following examples:

- Overall evidence regarding the value of vitamin D supplementation in patients with HF remains “inconclusive” and may be harmful when taken with HF medications such as digoxin, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics.

- Routine thiamine supplementation in patients with HF and without clinically significant thiamine deficiency may not be efficacious and should be avoided.

- Research on alcohol varies, with some data showing that drinking low-to-moderate amounts (one to two drinks per day) may help prevent HF, while habitual drinking or consuming higher amounts is known to contribute to HF.

- The literature is mixed on vitamin E. It may have some benefit in reducing the risk of HF with preserved ejection fraction but has also been associated with an increased risk of HF hospitalization.

- Coenzyme Q10 (Co-Q10), commonly taken as a dietary supplement, may help improve HF class, symptoms, and quality of life, but it also may interact with antihypertensive and anticoagulant medication. Co-Q10 remains of “uncertain” value in HF at this time. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed before any definitive conclusion can be reached.

- Hawthorn, a flowering shrub, has been shown in some studies to increase exercise tolerance and improve HF symptoms such as fatigue. Yet it also has the potential to worsen HF, and there is conflicting research about whether it interacts with digoxin.

- The herbal supplement blue cohosh, from the root of a flowering plant found in hardwood forests, could cause tachycardia, high blood pressure, chest pain, and increased blood glucose. It may also decrease the effect of medications taken to treat high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, they noted.

- Lily of the Valley, the root, stems, and flower of which are used in supplements, has long been used in mild HF because it contains active chemicals similar to digoxin. But when taken with digoxin, it could lead to hypokalemia.

In an AHA news release, Dr. Chow said, “Overall, more quality research and well-powered randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the risks and benefits” of CAM therapies for HF.

“This scientific statement provides critical information to health care professionals who treat people with heart failure and may be used as a resource for consumers about the potential benefit and harm associated with complementary and alternative medicine products,” Dr. Chow added.

The writing group encourages health care professionals to routinely ask their HF patients about their use of CAM therapies. They also say pharmacists should be included in the multidisciplinary health care team to provide consultations about the use of CAM therapies for HF patients.

The scientific statement does not include cannabis or traditional Chinese medicine, which have also been used in HF.

In 2020, the AHA published a separate scientific statement on the use of medical marijuana and recreational cannabis on cardiovascular health, as reported previously by this news organization.

The scientific statement on CAM for HF was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Clinical Pharmacology Committee and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There are some benefits and potentially serious risks associated with complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) patients with heart failure (HF) may use to manage symptoms, the American Heart Association noted in a new scientific statement on the topic.

For example, yoga and tai chi can be helpful for people with HF, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may also have benefits. However, there are safety concerns with other commonly used over-the-counter CAM therapies, including vitamin D, blue cohosh, and Lily of the Valley, the writing group said.

It’s estimated that roughly one in three patients with HF use CAM. But often patients don’t report their CAM use to their clinicians and clinicians may not routinely ask about CAM use or have the resources to evaluate CAM therapies, writing group chair Sheryl L. Chow, PharmD, told this news organization.

“This represents a major public health problem given that consumers are frequently purchasing these potentially dangerous and minimally regulated products without the knowledge or advice from a health care professional,” said Dr. Chow, of Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, Calif., and University of California, Irvine.

The 27-page statement was published online in Circulation.

CAM use common in HF

The statement defines CAM as medical practices, supplements, and approaches that do not conform to the standards of conventional, evidence-based practice guidelines. CAM products are available without prescriptions or medical guidance at pharmacies, health food stores, and online retailers.

“These agents are largely unregulated by the [Food and Drug Administration] and manufacturers do not need to demonstrate efficacy or safety. It is important that both health care professionals and consumers improve communication with respect to OTC therapies and are educated about potential efficacy and risk of harm so that shared and informed decision-making can occur,” Dr. Chow said.

The writing group reviewed research published before November 2021 on CAM among people with HF.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as fish oil, have the strongest evidence among CAM agents for clinical benefit in HF and may be used safely by patients in moderation and in consultation with their health care team, the writing group said.

Research has shown that omega-3 PUFAs are associated with a lower risk of developing HF as well as improvements in left ventricular systolic function in those with existing HF, they pointed out.

However, two clinical trials found a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation with high-dose omega-3 PUFA administration. “This risk appears to be dose-related and increased when exceeding 2 g/d of fish oil,” the writing group said.

Research suggests that yoga and tai chi, when added to standard HF treatment, may help improve exercise tolerance and quality of life and decrease blood pressure.

Inconclusive or potentially harmful CAM therapies

Other CAM therapies for HF have been shown as ineffective based on current data, have mixed findings, or appear to be harmful. The writers highlighted the following examples:

- Overall evidence regarding the value of vitamin D supplementation in patients with HF remains “inconclusive” and may be harmful when taken with HF medications such as digoxin, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics.

- Routine thiamine supplementation in patients with HF and without clinically significant thiamine deficiency may not be efficacious and should be avoided.

- Research on alcohol varies, with some data showing that drinking low-to-moderate amounts (one to two drinks per day) may help prevent HF, while habitual drinking or consuming higher amounts is known to contribute to HF.

- The literature is mixed on vitamin E. It may have some benefit in reducing the risk of HF with preserved ejection fraction but has also been associated with an increased risk of HF hospitalization.

- Coenzyme Q10 (Co-Q10), commonly taken as a dietary supplement, may help improve HF class, symptoms, and quality of life, but it also may interact with antihypertensive and anticoagulant medication. Co-Q10 remains of “uncertain” value in HF at this time. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed before any definitive conclusion can be reached.

- Hawthorn, a flowering shrub, has been shown in some studies to increase exercise tolerance and improve HF symptoms such as fatigue. Yet it also has the potential to worsen HF, and there is conflicting research about whether it interacts with digoxin.

- The herbal supplement blue cohosh, from the root of a flowering plant found in hardwood forests, could cause tachycardia, high blood pressure, chest pain, and increased blood glucose. It may also decrease the effect of medications taken to treat high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, they noted.

- Lily of the Valley, the root, stems, and flower of which are used in supplements, has long been used in mild HF because it contains active chemicals similar to digoxin. But when taken with digoxin, it could lead to hypokalemia.

In an AHA news release, Dr. Chow said, “Overall, more quality research and well-powered randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the risks and benefits” of CAM therapies for HF.

“This scientific statement provides critical information to health care professionals who treat people with heart failure and may be used as a resource for consumers about the potential benefit and harm associated with complementary and alternative medicine products,” Dr. Chow added.

The writing group encourages health care professionals to routinely ask their HF patients about their use of CAM therapies. They also say pharmacists should be included in the multidisciplinary health care team to provide consultations about the use of CAM therapies for HF patients.

The scientific statement does not include cannabis or traditional Chinese medicine, which have also been used in HF.

In 2020, the AHA published a separate scientific statement on the use of medical marijuana and recreational cannabis on cardiovascular health, as reported previously by this news organization.

The scientific statement on CAM for HF was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Clinical Pharmacology Committee and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There are some benefits and potentially serious risks associated with complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) patients with heart failure (HF) may use to manage symptoms, the American Heart Association noted in a new scientific statement on the topic.

For example, yoga and tai chi can be helpful for people with HF, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may also have benefits. However, there are safety concerns with other commonly used over-the-counter CAM therapies, including vitamin D, blue cohosh, and Lily of the Valley, the writing group said.

It’s estimated that roughly one in three patients with HF use CAM. But often patients don’t report their CAM use to their clinicians and clinicians may not routinely ask about CAM use or have the resources to evaluate CAM therapies, writing group chair Sheryl L. Chow, PharmD, told this news organization.

“This represents a major public health problem given that consumers are frequently purchasing these potentially dangerous and minimally regulated products without the knowledge or advice from a health care professional,” said Dr. Chow, of Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, Calif., and University of California, Irvine.

The 27-page statement was published online in Circulation.

CAM use common in HF

The statement defines CAM as medical practices, supplements, and approaches that do not conform to the standards of conventional, evidence-based practice guidelines. CAM products are available without prescriptions or medical guidance at pharmacies, health food stores, and online retailers.

“These agents are largely unregulated by the [Food and Drug Administration] and manufacturers do not need to demonstrate efficacy or safety. It is important that both health care professionals and consumers improve communication with respect to OTC therapies and are educated about potential efficacy and risk of harm so that shared and informed decision-making can occur,” Dr. Chow said.

The writing group reviewed research published before November 2021 on CAM among people with HF.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as fish oil, have the strongest evidence among CAM agents for clinical benefit in HF and may be used safely by patients in moderation and in consultation with their health care team, the writing group said.

Research has shown that omega-3 PUFAs are associated with a lower risk of developing HF as well as improvements in left ventricular systolic function in those with existing HF, they pointed out.

However, two clinical trials found a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation with high-dose omega-3 PUFA administration. “This risk appears to be dose-related and increased when exceeding 2 g/d of fish oil,” the writing group said.

Research suggests that yoga and tai chi, when added to standard HF treatment, may help improve exercise tolerance and quality of life and decrease blood pressure.

Inconclusive or potentially harmful CAM therapies

Other CAM therapies for HF have been shown as ineffective based on current data, have mixed findings, or appear to be harmful. The writers highlighted the following examples:

- Overall evidence regarding the value of vitamin D supplementation in patients with HF remains “inconclusive” and may be harmful when taken with HF medications such as digoxin, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics.

- Routine thiamine supplementation in patients with HF and without clinically significant thiamine deficiency may not be efficacious and should be avoided.

- Research on alcohol varies, with some data showing that drinking low-to-moderate amounts (one to two drinks per day) may help prevent HF, while habitual drinking or consuming higher amounts is known to contribute to HF.

- The literature is mixed on vitamin E. It may have some benefit in reducing the risk of HF with preserved ejection fraction but has also been associated with an increased risk of HF hospitalization.

- Coenzyme Q10 (Co-Q10), commonly taken as a dietary supplement, may help improve HF class, symptoms, and quality of life, but it also may interact with antihypertensive and anticoagulant medication. Co-Q10 remains of “uncertain” value in HF at this time. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed before any definitive conclusion can be reached.

- Hawthorn, a flowering shrub, has been shown in some studies to increase exercise tolerance and improve HF symptoms such as fatigue. Yet it also has the potential to worsen HF, and there is conflicting research about whether it interacts with digoxin.

- The herbal supplement blue cohosh, from the root of a flowering plant found in hardwood forests, could cause tachycardia, high blood pressure, chest pain, and increased blood glucose. It may also decrease the effect of medications taken to treat high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, they noted.

- Lily of the Valley, the root, stems, and flower of which are used in supplements, has long been used in mild HF because it contains active chemicals similar to digoxin. But when taken with digoxin, it could lead to hypokalemia.

In an AHA news release, Dr. Chow said, “Overall, more quality research and well-powered randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the risks and benefits” of CAM therapies for HF.

“This scientific statement provides critical information to health care professionals who treat people with heart failure and may be used as a resource for consumers about the potential benefit and harm associated with complementary and alternative medicine products,” Dr. Chow added.

The writing group encourages health care professionals to routinely ask their HF patients about their use of CAM therapies. They also say pharmacists should be included in the multidisciplinary health care team to provide consultations about the use of CAM therapies for HF patients.

The scientific statement does not include cannabis or traditional Chinese medicine, which have also been used in HF.

In 2020, the AHA published a separate scientific statement on the use of medical marijuana and recreational cannabis on cardiovascular health, as reported previously by this news organization.

The scientific statement on CAM for HF was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Clinical Pharmacology Committee and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CIRCULATION

Statins tied to lower ICH risk regardless of bleed location

A new study has provided further reassurance on questions about the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with statins.

The Danish case-control study, which compared statin use in 2,164 case patients with ICH and in 86,255 matched control persons, found that current statin use was associated with a lower risk of having a first ICH and that the risk was further reduced with longer duration of statin use.

The study also showed that statin use was linked to a lower risk of ICH in the more superficial lobar areas of the brain and in the deeper, nonlobar locations. There was no difference in the magnitude of risk reduction between the two locations.

“Although this study is observational, I feel these data are strong, and the results are reassuring. It certainly does not suggest any increased risk of ICH with statins,” senior author David Gaist, PhD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, said in an interview.

“On the contrary, it indicates a lower risk, which seems to be independent of the location of the bleed.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

The authors note that statins effectively reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events and ischemic stroke in high-risk populations, but early randomized trials raised concerns of an increased risk of ICH among statin users who have a history of stroke.

Subsequent observational studies, including four meta-analyses, included patients with and those without prior stroke. The results were inconsistent, although most found no increase in bleeding. More recent studies have found a lower risk of ICH among statin users; the risk was inversely associated with the duration and intensity of statin treatment.

However, the researchers point out that few studies have assessed the association between statin use and the location of ICH. Hemorrhages that occur in the lobar region of the brain and those that occur in the nonlobar areas can have different pathophysiologies. Arteriolosclerosis, which is strongly associated with hypertension, is a common histologic finding in patients with ICH, regardless of hemorrhage location, while cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is associated with lobar but not nonlobar ICH.

The current study was conducted to look more closely at the relationship between statin use and hematoma location as a reflection of differences in the underlying pathophysiologies of lobar versus nonlobar ICH.

The researchers used Danish registries to identify all first-ever cases of spontaneous ICH that occurred between 2009 and 2018 in persons older than 55 years in the Southern Denmark region. Patients with traumatic ICH or ICH related to vascular malformations and tumors were excluded.

These cases were verified through medical records. ICH diagnoses were classified as having a lobar or nonlobar location, and patients were matched for age, sex, and calendar year to general population control persons. The nationwide prescription registry was also analyzed to ascertain use of statins and other medications.

The study included 989 patients with lobar ICH who were matched to 39,500 control persons and 1,175 patients with nonlobar ICH who were matched to 46,755 control persons.

Results showed that current statin use was associated with a 16%-17% relative reduction in ICH risk. There was no difference with respect to ICH location.

For lobar ICH, statin use showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.83 (95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.98); for nonlobar ICH, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.72-0.98).

Longer duration of statin use was associated with a greater reduction in risk of ICH; use for more than 5 years was associated with a relative reduction of ICH of 33%-38%, again with no difference with regard to ICH location.

For lobar ICH, statin use for more than 5 years showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.51-0.87); and for nonlobar ICH, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.62 (95% CI, 0.48-0.80).

“We suspected that statins may have more of an effect in reducing nonlobar ICH, as this type is considered to be more associated with arteriosclerosis, compared with lobar ICH,” Dr. Gaist explained. “But we didn’t find that. We found that taking statins was associated with a similar reduction in risk of both lobar and nonlobar ICH.”

Although amyloid angiopathy can contribute to lobar ICH, arteriosclerosis is still involved in the majority of cases, he noted. He cited a recent population-based U.K. study that showed that while histologically verified CAA was present in 58% of patients with a lobar ICH, most also had evidence of arteriosclerosis, with only 13% having isolated CAA pathology.

“If statins exert their effect on reducing ICH by reducing arteriosclerosis, which is likely, then this observation of arteriosclerosis pathology being prevalent in both lobar and nonlobar ICH locations would explain our results,” Dr. Gaist commented.

“Strengths of our study include the large numbers involved and the fact that the patients are unselected. We tried to find everyone who had had a first ICH in a well-defined region of Denmark, so issues of selection are less of a concern than in some other studies,” he noted.

He also pointed out that all the ICH diagnoses were verified from medical records and that in a substudy, brain scans were evaluated, with investigators masked to clinical data to evaluate the location and characteristics of the hematoma. In addition, data on statin use were collected prospectively from a nationwide prescription registry.

Interaction with antihypertensives, anticoagulants?

Other results from the study suggest a possible interaction between statin use and antihypertensive and anticoagulant drugs.

Data showed that the lower ICH risk was restricted to patients who received statins and antihypertensive drugs concurrently. Conversely, only patients who were not concurrently taking anticoagulants had a lower risk of ICH in association with statin use.

Dr. Gaist suggested that the lack of a reduction in ICH with statins among patients taking anticoagulants could be because the increased risk of ICH with anticoagulants was stronger than the reduced risk with statins.

Regarding the fact that the reduced risk of ICH with statins was only observed among individuals who were also taking antihypertensive medication, Dr. Gaist noted that because hypertension is such an important risk factor for ICH, “it may be that to get the true benefit of statins, patients have to have their hypertension controlled.”

However, an alternative explanation could that the finding is a result of “healthy adherer” bias, in which people who take antihypertensive medication and follow a healthy lifestyle as advised would be more likely to take statins.

“The observational nature of our study does not allow us to determine the extent to which associations are causal,” the authors say.

Dr. Gaist also noted that an important caveat in this study is that they focused on individuals who had had a first ICH.

“This data does not inform us about those who have already had an ICH and are taking statins. But we are planning to look at this in our next study,” he said.

The study was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Dr. Gaist has received speaker honorarium from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer unrelated to this work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has provided further reassurance on questions about the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with statins.

The Danish case-control study, which compared statin use in 2,164 case patients with ICH and in 86,255 matched control persons, found that current statin use was associated with a lower risk of having a first ICH and that the risk was further reduced with longer duration of statin use.

The study also showed that statin use was linked to a lower risk of ICH in the more superficial lobar areas of the brain and in the deeper, nonlobar locations. There was no difference in the magnitude of risk reduction between the two locations.

“Although this study is observational, I feel these data are strong, and the results are reassuring. It certainly does not suggest any increased risk of ICH with statins,” senior author David Gaist, PhD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, said in an interview.

“On the contrary, it indicates a lower risk, which seems to be independent of the location of the bleed.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

The authors note that statins effectively reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events and ischemic stroke in high-risk populations, but early randomized trials raised concerns of an increased risk of ICH among statin users who have a history of stroke.

Subsequent observational studies, including four meta-analyses, included patients with and those without prior stroke. The results were inconsistent, although most found no increase in bleeding. More recent studies have found a lower risk of ICH among statin users; the risk was inversely associated with the duration and intensity of statin treatment.

However, the researchers point out that few studies have assessed the association between statin use and the location of ICH. Hemorrhages that occur in the lobar region of the brain and those that occur in the nonlobar areas can have different pathophysiologies. Arteriolosclerosis, which is strongly associated with hypertension, is a common histologic finding in patients with ICH, regardless of hemorrhage location, while cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is associated with lobar but not nonlobar ICH.

The current study was conducted to look more closely at the relationship between statin use and hematoma location as a reflection of differences in the underlying pathophysiologies of lobar versus nonlobar ICH.

The researchers used Danish registries to identify all first-ever cases of spontaneous ICH that occurred between 2009 and 2018 in persons older than 55 years in the Southern Denmark region. Patients with traumatic ICH or ICH related to vascular malformations and tumors were excluded.

These cases were verified through medical records. ICH diagnoses were classified as having a lobar or nonlobar location, and patients were matched for age, sex, and calendar year to general population control persons. The nationwide prescription registry was also analyzed to ascertain use of statins and other medications.

The study included 989 patients with lobar ICH who were matched to 39,500 control persons and 1,175 patients with nonlobar ICH who were matched to 46,755 control persons.

Results showed that current statin use was associated with a 16%-17% relative reduction in ICH risk. There was no difference with respect to ICH location.

For lobar ICH, statin use showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.83 (95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.98); for nonlobar ICH, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.72-0.98).

Longer duration of statin use was associated with a greater reduction in risk of ICH; use for more than 5 years was associated with a relative reduction of ICH of 33%-38%, again with no difference with regard to ICH location.

For lobar ICH, statin use for more than 5 years showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.51-0.87); and for nonlobar ICH, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.62 (95% CI, 0.48-0.80).

“We suspected that statins may have more of an effect in reducing nonlobar ICH, as this type is considered to be more associated with arteriosclerosis, compared with lobar ICH,” Dr. Gaist explained. “But we didn’t find that. We found that taking statins was associated with a similar reduction in risk of both lobar and nonlobar ICH.”

Although amyloid angiopathy can contribute to lobar ICH, arteriosclerosis is still involved in the majority of cases, he noted. He cited a recent population-based U.K. study that showed that while histologically verified CAA was present in 58% of patients with a lobar ICH, most also had evidence of arteriosclerosis, with only 13% having isolated CAA pathology.

“If statins exert their effect on reducing ICH by reducing arteriosclerosis, which is likely, then this observation of arteriosclerosis pathology being prevalent in both lobar and nonlobar ICH locations would explain our results,” Dr. Gaist commented.

“Strengths of our study include the large numbers involved and the fact that the patients are unselected. We tried to find everyone who had had a first ICH in a well-defined region of Denmark, so issues of selection are less of a concern than in some other studies,” he noted.

He also pointed out that all the ICH diagnoses were verified from medical records and that in a substudy, brain scans were evaluated, with investigators masked to clinical data to evaluate the location and characteristics of the hematoma. In addition, data on statin use were collected prospectively from a nationwide prescription registry.

Interaction with antihypertensives, anticoagulants?

Other results from the study suggest a possible interaction between statin use and antihypertensive and anticoagulant drugs.

Data showed that the lower ICH risk was restricted to patients who received statins and antihypertensive drugs concurrently. Conversely, only patients who were not concurrently taking anticoagulants had a lower risk of ICH in association with statin use.

Dr. Gaist suggested that the lack of a reduction in ICH with statins among patients taking anticoagulants could be because the increased risk of ICH with anticoagulants was stronger than the reduced risk with statins.

Regarding the fact that the reduced risk of ICH with statins was only observed among individuals who were also taking antihypertensive medication, Dr. Gaist noted that because hypertension is such an important risk factor for ICH, “it may be that to get the true benefit of statins, patients have to have their hypertension controlled.”

However, an alternative explanation could that the finding is a result of “healthy adherer” bias, in which people who take antihypertensive medication and follow a healthy lifestyle as advised would be more likely to take statins.

“The observational nature of our study does not allow us to determine the extent to which associations are causal,” the authors say.

Dr. Gaist also noted that an important caveat in this study is that they focused on individuals who had had a first ICH.

“This data does not inform us about those who have already had an ICH and are taking statins. But we are planning to look at this in our next study,” he said.

The study was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Dr. Gaist has received speaker honorarium from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer unrelated to this work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has provided further reassurance on questions about the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with statins.

The Danish case-control study, which compared statin use in 2,164 case patients with ICH and in 86,255 matched control persons, found that current statin use was associated with a lower risk of having a first ICH and that the risk was further reduced with longer duration of statin use.

The study also showed that statin use was linked to a lower risk of ICH in the more superficial lobar areas of the brain and in the deeper, nonlobar locations. There was no difference in the magnitude of risk reduction between the two locations.

“Although this study is observational, I feel these data are strong, and the results are reassuring. It certainly does not suggest any increased risk of ICH with statins,” senior author David Gaist, PhD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, said in an interview.

“On the contrary, it indicates a lower risk, which seems to be independent of the location of the bleed.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

The authors note that statins effectively reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events and ischemic stroke in high-risk populations, but early randomized trials raised concerns of an increased risk of ICH among statin users who have a history of stroke.

Subsequent observational studies, including four meta-analyses, included patients with and those without prior stroke. The results were inconsistent, although most found no increase in bleeding. More recent studies have found a lower risk of ICH among statin users; the risk was inversely associated with the duration and intensity of statin treatment.

However, the researchers point out that few studies have assessed the association between statin use and the location of ICH. Hemorrhages that occur in the lobar region of the brain and those that occur in the nonlobar areas can have different pathophysiologies. Arteriolosclerosis, which is strongly associated with hypertension, is a common histologic finding in patients with ICH, regardless of hemorrhage location, while cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is associated with lobar but not nonlobar ICH.

The current study was conducted to look more closely at the relationship between statin use and hematoma location as a reflection of differences in the underlying pathophysiologies of lobar versus nonlobar ICH.

The researchers used Danish registries to identify all first-ever cases of spontaneous ICH that occurred between 2009 and 2018 in persons older than 55 years in the Southern Denmark region. Patients with traumatic ICH or ICH related to vascular malformations and tumors were excluded.

These cases were verified through medical records. ICH diagnoses were classified as having a lobar or nonlobar location, and patients were matched for age, sex, and calendar year to general population control persons. The nationwide prescription registry was also analyzed to ascertain use of statins and other medications.

The study included 989 patients with lobar ICH who were matched to 39,500 control persons and 1,175 patients with nonlobar ICH who were matched to 46,755 control persons.

Results showed that current statin use was associated with a 16%-17% relative reduction in ICH risk. There was no difference with respect to ICH location.

For lobar ICH, statin use showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.83 (95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.98); for nonlobar ICH, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.72-0.98).

Longer duration of statin use was associated with a greater reduction in risk of ICH; use for more than 5 years was associated with a relative reduction of ICH of 33%-38%, again with no difference with regard to ICH location.

For lobar ICH, statin use for more than 5 years showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.51-0.87); and for nonlobar ICH, the adjusted odds ratio was 0.62 (95% CI, 0.48-0.80).

“We suspected that statins may have more of an effect in reducing nonlobar ICH, as this type is considered to be more associated with arteriosclerosis, compared with lobar ICH,” Dr. Gaist explained. “But we didn’t find that. We found that taking statins was associated with a similar reduction in risk of both lobar and nonlobar ICH.”

Although amyloid angiopathy can contribute to lobar ICH, arteriosclerosis is still involved in the majority of cases, he noted. He cited a recent population-based U.K. study that showed that while histologically verified CAA was present in 58% of patients with a lobar ICH, most also had evidence of arteriosclerosis, with only 13% having isolated CAA pathology.

“If statins exert their effect on reducing ICH by reducing arteriosclerosis, which is likely, then this observation of arteriosclerosis pathology being prevalent in both lobar and nonlobar ICH locations would explain our results,” Dr. Gaist commented.

“Strengths of our study include the large numbers involved and the fact that the patients are unselected. We tried to find everyone who had had a first ICH in a well-defined region of Denmark, so issues of selection are less of a concern than in some other studies,” he noted.

He also pointed out that all the ICH diagnoses were verified from medical records and that in a substudy, brain scans were evaluated, with investigators masked to clinical data to evaluate the location and characteristics of the hematoma. In addition, data on statin use were collected prospectively from a nationwide prescription registry.

Interaction with antihypertensives, anticoagulants?

Other results from the study suggest a possible interaction between statin use and antihypertensive and anticoagulant drugs.

Data showed that the lower ICH risk was restricted to patients who received statins and antihypertensive drugs concurrently. Conversely, only patients who were not concurrently taking anticoagulants had a lower risk of ICH in association with statin use.

Dr. Gaist suggested that the lack of a reduction in ICH with statins among patients taking anticoagulants could be because the increased risk of ICH with anticoagulants was stronger than the reduced risk with statins.

Regarding the fact that the reduced risk of ICH with statins was only observed among individuals who were also taking antihypertensive medication, Dr. Gaist noted that because hypertension is such an important risk factor for ICH, “it may be that to get the true benefit of statins, patients have to have their hypertension controlled.”

However, an alternative explanation could that the finding is a result of “healthy adherer” bias, in which people who take antihypertensive medication and follow a healthy lifestyle as advised would be more likely to take statins.

“The observational nature of our study does not allow us to determine the extent to which associations are causal,” the authors say.

Dr. Gaist also noted that an important caveat in this study is that they focused on individuals who had had a first ICH.

“This data does not inform us about those who have already had an ICH and are taking statins. But we are planning to look at this in our next study,” he said.

The study was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Dr. Gaist has received speaker honorarium from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer unrelated to this work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No, you can’t see a different doctor: We need zero tolerance of patient bias

It was 1970. I was in my second year of medical school. I can remember the hurt and embarrassment as if it were yesterday.

Coming from the Deep South, I was very familiar with racial bias, but I did not expect it at that level and in that environment. From that point on, I was anxious at each patient encounter, concerned that this might happen again. And it did several times during my residency and fellowship.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines workplace violence as “any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults.”

There is considerable media focus on incidents of physical violence against health care workers, but when patients, their families, or visitors openly display bias and request a different doctor, nurse, or technician for nonmedical reasons, the impact is profound. This is extremely hurtful to a professional who has worked long and hard to acquire skills and expertise. And, while speech may not constitute violence in the strictest sense of the word, there is growing evidence that it can be physically harmful through its effect on the nervous system, even if no physical contact is involved.

Incidents of bias occur regularly and are clearly on the rise. In most cases the request for a different health care worker is granted to honor the rights of the patient. The healthcare worker is left alone and emotionally wounded; the healthcare institutions are complicit.

This bias is mostly racial but can also be based on religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, body size, accent, or gender.

An entire issue of the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics was devoted to this topic. From recognizing that there are limits to what clinicians should be expected to tolerate when patients’ preferences express unjust bias, the issue also explored where those limits should be placed, why, and who is obliged to enforce them.

The newly adopted Mass General Patient Code of Conduct is evidence that health care systems are beginning to recognize this problem and that such behavior will not be tolerated.

But having a zero-tolerance policy is not enough. We must have procedures in place to discourage and mitigate the impact of patient bias.

A clear definition of what constitutes a bias incident is essential. All team members must be made aware of the procedures for reporting such incidents and the chain of command for escalation. Reporting should be encouraged, and resources must be made available to impacted team members. Surveillance, monitoring, and review are also essential as is clarification on when patient preferences should be honored.

The Mayo Clinic 5 Step Plan is an excellent example of a protocol to deal with patient bias against health care workers and is based on a thoughtful analysis of what constitutes an unreasonable request for a different clinician. I’m pleased to report that my health care system (Inova Health) is developing a similar protocol.

The health care setting should be a bias-free zone for both patients and health care workers. I have been a strong advocate of patients’ rights and worked hard to guard against bias and eliminate disparities in care, but health care workers have rights as well.

We should expect to be treated with respect.

The views expressed by the author are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of the Inova Health System. Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was 1970. I was in my second year of medical school. I can remember the hurt and embarrassment as if it were yesterday.