User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Flu hospitalizations drop amid signs of an early peak

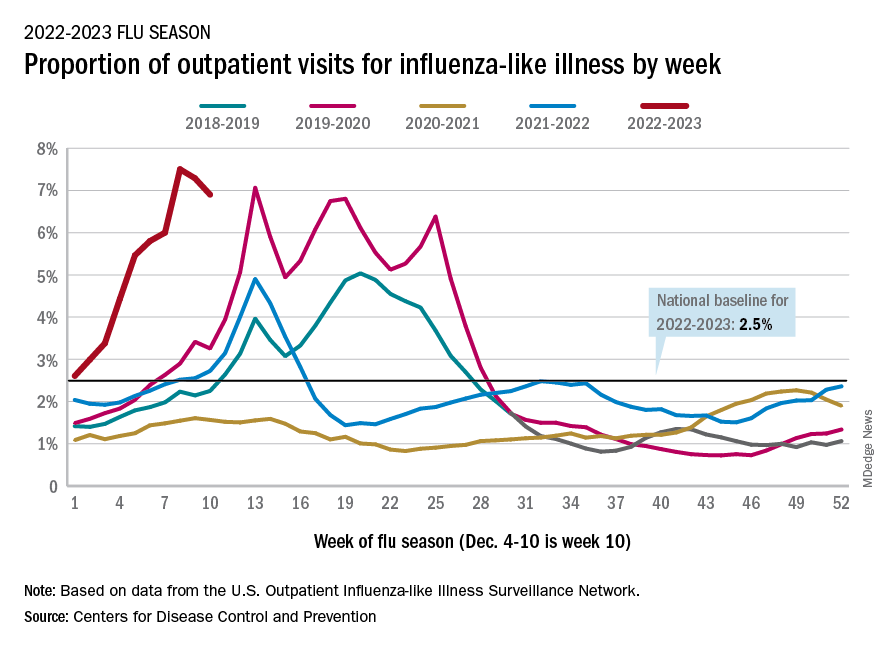

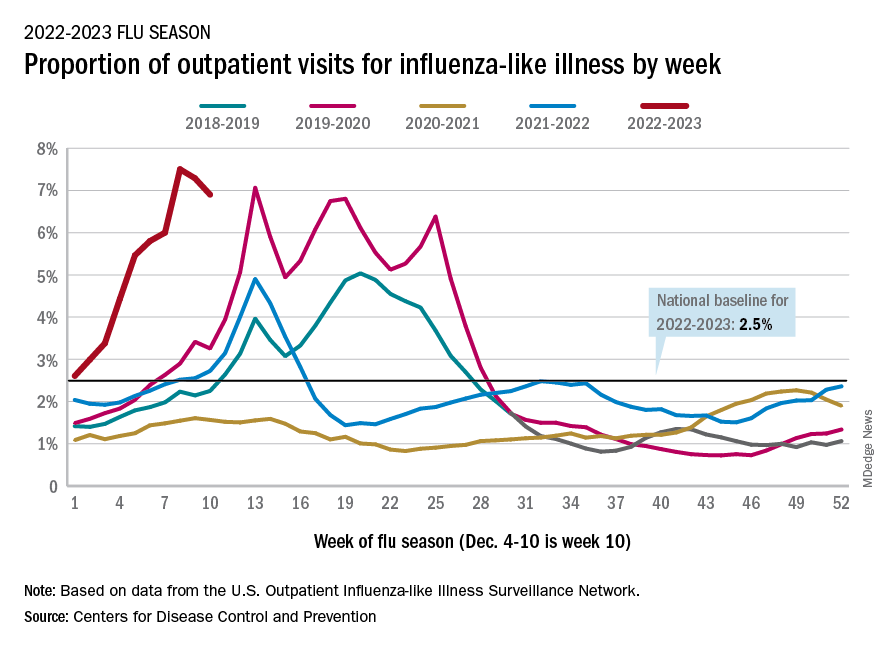

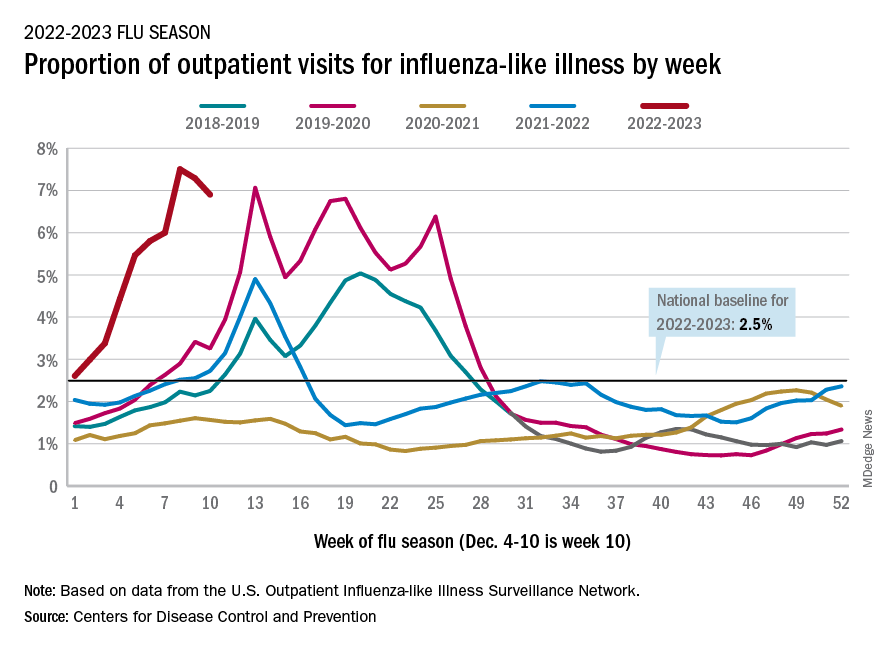

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Docs treating other doctors: What can go wrong?

It’s not unusual for physicians to see other doctors as patients – often they’re colleagues or even friends.

“When doctors don’t get the proper care, that’s when things go south. Any time physicians lower their standard of care, there is a risk of missing something that could affect their differential diagnosis, ultimate working diagnosis, and treatment plan,” said Michael Myers, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, who saw only medical students, physicians, and their family members in his private practice for over 3 decades.

Of the more than 200 physicians who responded to a recent Medscape poll, more than half said they treated physician-patients differently from other patients.

They granted their peers special privileges: They spent more time with them than other patients, gave out their personal contact information, and granted them professional courtesy by waiving or discounting their fees.

Published studies have reported that special treatment of physician-patients, such as giving personal contact information or avoiding uncomfortable testing, can create challenges for the treating physicians who may feel pressure to deviate from the standard of care.

The American Medical Association has recognized the challenges that physicians have when they treat other physicians they know personally or professionally, including a potential loss of objectivity, privacy, or confidentiality.

The AMA recommends that physicians treat physician-patients the same way they would other patients. The guidance states that the treating physician should exercise objective professional judgment and make unbiased treatment recommendations; be sensitive to the potential psychological discomfort of the physician-patient, and respect the physical and informational privacy of physician-patients.

Dr. Myers recalled that one doctor-patient said his primary care physician was his business partner in the practice. They ordered tests for each other and occasionally examined each other, but the patient never felt comfortable asking his partner for a full physical, said Dr. Myers, the author of “Becoming a Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir.”

“I recommended that he choose a primary care doctor whom he didn’t know so that he could truly be a patient and the doctor could truly be a treating doctor,” said Dr. Myers.

Physician-patients may also be concerned about running into their physicians and being judged, or that they will break confidentiality and tell their spouse or another colleague, said Dr. Myers.

“When your doctor is a complete and total stranger, and especially if you live in a sizable community and your paths never cross, you don’t have that added worry,” he said.

Do docs expect special treatment as patients?

Some doctors expect special treatment from other doctors when they’re patients – 14% of physician poll respondents said that was their experience.

Dr. Myers recommends setting boundaries with doctor-patients early on in the relationship. “Some doctors expected me to go over my regular appointment time and when they realized that I started and stopped on time, they got upset. Once, one doctor insisted to my answering service that he had to talk to me although I was at home. When he started talking, I interrupted him and asked if the matter was urgent. He said no, so I offered to fit him in before his next appointment if he felt it couldn’t wait,” said Dr. Myers.

Some doctors also give physician-patients “professional courtesy” when it comes to payment. One in four poll respondents said they waived or discounted their professional fees for a doctor-patient. As most doctors have health insurance, doctors may waive copayments or other out-of-pocket fees, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

However, waiving or discounting health insurance fees, especially for government funded insurance, may be illegal under federal anti-fraud and abuse laws and payer contracts as well as state laws, the AAP says. It’s best to check with an attorney.

Treating other physicians can be rewarding

“Physicians can be the most rewarding patients because they are allies and partners in the effort to overcome whatever is ailing them,” said one doctor who responded to the Medscape poll.

Over two-thirds of respondents said that doctor-patients participated much more in their care than did other patients – typically, they discussed their care in more depth than did other patients.

Most doctors also felt that it was easier to communicate with their physician-patients than other patients because they understood medicine and were knowledgeable about their conditions.

Being judged by your peers can be stressful

How physicians feel about treating physician-patients is complicated. Nearly half of respondents said that it was more stressful than treating other patients.

One respondent said, “If we are honest, treating other physicians as patients is more stressful because we know that our skills are being assessed by someone who is at our level. There is no training for treating physicians, as there is for the Pope’s confessor. And we can be challenging in more ways than one!”

About one-third of poll respondents said they were afraid of disappointing their physician-patients.

“I’m not surprised,” said Dr. Myers, when told of that poll response. “This is why some doctors are reluctant to treat other physicians; they may wonder whether they’re up to speed. I have always thrived on having a high bar set for me – it spurs me on to really stay current with the literature and be humble,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not unusual for physicians to see other doctors as patients – often they’re colleagues or even friends.

“When doctors don’t get the proper care, that’s when things go south. Any time physicians lower their standard of care, there is a risk of missing something that could affect their differential diagnosis, ultimate working diagnosis, and treatment plan,” said Michael Myers, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, who saw only medical students, physicians, and their family members in his private practice for over 3 decades.

Of the more than 200 physicians who responded to a recent Medscape poll, more than half said they treated physician-patients differently from other patients.

They granted their peers special privileges: They spent more time with them than other patients, gave out their personal contact information, and granted them professional courtesy by waiving or discounting their fees.

Published studies have reported that special treatment of physician-patients, such as giving personal contact information or avoiding uncomfortable testing, can create challenges for the treating physicians who may feel pressure to deviate from the standard of care.

The American Medical Association has recognized the challenges that physicians have when they treat other physicians they know personally or professionally, including a potential loss of objectivity, privacy, or confidentiality.

The AMA recommends that physicians treat physician-patients the same way they would other patients. The guidance states that the treating physician should exercise objective professional judgment and make unbiased treatment recommendations; be sensitive to the potential psychological discomfort of the physician-patient, and respect the physical and informational privacy of physician-patients.

Dr. Myers recalled that one doctor-patient said his primary care physician was his business partner in the practice. They ordered tests for each other and occasionally examined each other, but the patient never felt comfortable asking his partner for a full physical, said Dr. Myers, the author of “Becoming a Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir.”

“I recommended that he choose a primary care doctor whom he didn’t know so that he could truly be a patient and the doctor could truly be a treating doctor,” said Dr. Myers.

Physician-patients may also be concerned about running into their physicians and being judged, or that they will break confidentiality and tell their spouse or another colleague, said Dr. Myers.

“When your doctor is a complete and total stranger, and especially if you live in a sizable community and your paths never cross, you don’t have that added worry,” he said.

Do docs expect special treatment as patients?

Some doctors expect special treatment from other doctors when they’re patients – 14% of physician poll respondents said that was their experience.

Dr. Myers recommends setting boundaries with doctor-patients early on in the relationship. “Some doctors expected me to go over my regular appointment time and when they realized that I started and stopped on time, they got upset. Once, one doctor insisted to my answering service that he had to talk to me although I was at home. When he started talking, I interrupted him and asked if the matter was urgent. He said no, so I offered to fit him in before his next appointment if he felt it couldn’t wait,” said Dr. Myers.

Some doctors also give physician-patients “professional courtesy” when it comes to payment. One in four poll respondents said they waived or discounted their professional fees for a doctor-patient. As most doctors have health insurance, doctors may waive copayments or other out-of-pocket fees, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

However, waiving or discounting health insurance fees, especially for government funded insurance, may be illegal under federal anti-fraud and abuse laws and payer contracts as well as state laws, the AAP says. It’s best to check with an attorney.

Treating other physicians can be rewarding

“Physicians can be the most rewarding patients because they are allies and partners in the effort to overcome whatever is ailing them,” said one doctor who responded to the Medscape poll.

Over two-thirds of respondents said that doctor-patients participated much more in their care than did other patients – typically, they discussed their care in more depth than did other patients.

Most doctors also felt that it was easier to communicate with their physician-patients than other patients because they understood medicine and were knowledgeable about their conditions.

Being judged by your peers can be stressful

How physicians feel about treating physician-patients is complicated. Nearly half of respondents said that it was more stressful than treating other patients.

One respondent said, “If we are honest, treating other physicians as patients is more stressful because we know that our skills are being assessed by someone who is at our level. There is no training for treating physicians, as there is for the Pope’s confessor. And we can be challenging in more ways than one!”

About one-third of poll respondents said they were afraid of disappointing their physician-patients.

“I’m not surprised,” said Dr. Myers, when told of that poll response. “This is why some doctors are reluctant to treat other physicians; they may wonder whether they’re up to speed. I have always thrived on having a high bar set for me – it spurs me on to really stay current with the literature and be humble,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not unusual for physicians to see other doctors as patients – often they’re colleagues or even friends.

“When doctors don’t get the proper care, that’s when things go south. Any time physicians lower their standard of care, there is a risk of missing something that could affect their differential diagnosis, ultimate working diagnosis, and treatment plan,” said Michael Myers, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, who saw only medical students, physicians, and their family members in his private practice for over 3 decades.

Of the more than 200 physicians who responded to a recent Medscape poll, more than half said they treated physician-patients differently from other patients.

They granted their peers special privileges: They spent more time with them than other patients, gave out their personal contact information, and granted them professional courtesy by waiving or discounting their fees.

Published studies have reported that special treatment of physician-patients, such as giving personal contact information or avoiding uncomfortable testing, can create challenges for the treating physicians who may feel pressure to deviate from the standard of care.

The American Medical Association has recognized the challenges that physicians have when they treat other physicians they know personally or professionally, including a potential loss of objectivity, privacy, or confidentiality.

The AMA recommends that physicians treat physician-patients the same way they would other patients. The guidance states that the treating physician should exercise objective professional judgment and make unbiased treatment recommendations; be sensitive to the potential psychological discomfort of the physician-patient, and respect the physical and informational privacy of physician-patients.

Dr. Myers recalled that one doctor-patient said his primary care physician was his business partner in the practice. They ordered tests for each other and occasionally examined each other, but the patient never felt comfortable asking his partner for a full physical, said Dr. Myers, the author of “Becoming a Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir.”

“I recommended that he choose a primary care doctor whom he didn’t know so that he could truly be a patient and the doctor could truly be a treating doctor,” said Dr. Myers.

Physician-patients may also be concerned about running into their physicians and being judged, or that they will break confidentiality and tell their spouse or another colleague, said Dr. Myers.

“When your doctor is a complete and total stranger, and especially if you live in a sizable community and your paths never cross, you don’t have that added worry,” he said.

Do docs expect special treatment as patients?

Some doctors expect special treatment from other doctors when they’re patients – 14% of physician poll respondents said that was their experience.

Dr. Myers recommends setting boundaries with doctor-patients early on in the relationship. “Some doctors expected me to go over my regular appointment time and when they realized that I started and stopped on time, they got upset. Once, one doctor insisted to my answering service that he had to talk to me although I was at home. When he started talking, I interrupted him and asked if the matter was urgent. He said no, so I offered to fit him in before his next appointment if he felt it couldn’t wait,” said Dr. Myers.

Some doctors also give physician-patients “professional courtesy” when it comes to payment. One in four poll respondents said they waived or discounted their professional fees for a doctor-patient. As most doctors have health insurance, doctors may waive copayments or other out-of-pocket fees, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

However, waiving or discounting health insurance fees, especially for government funded insurance, may be illegal under federal anti-fraud and abuse laws and payer contracts as well as state laws, the AAP says. It’s best to check with an attorney.

Treating other physicians can be rewarding

“Physicians can be the most rewarding patients because they are allies and partners in the effort to overcome whatever is ailing them,” said one doctor who responded to the Medscape poll.

Over two-thirds of respondents said that doctor-patients participated much more in their care than did other patients – typically, they discussed their care in more depth than did other patients.

Most doctors also felt that it was easier to communicate with their physician-patients than other patients because they understood medicine and were knowledgeable about their conditions.

Being judged by your peers can be stressful

How physicians feel about treating physician-patients is complicated. Nearly half of respondents said that it was more stressful than treating other patients.

One respondent said, “If we are honest, treating other physicians as patients is more stressful because we know that our skills are being assessed by someone who is at our level. There is no training for treating physicians, as there is for the Pope’s confessor. And we can be challenging in more ways than one!”

About one-third of poll respondents said they were afraid of disappointing their physician-patients.

“I’m not surprised,” said Dr. Myers, when told of that poll response. “This is why some doctors are reluctant to treat other physicians; they may wonder whether they’re up to speed. I have always thrived on having a high bar set for me – it spurs me on to really stay current with the literature and be humble,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New test that detects 14 cancers focuses on sugars, not DNA

The leader in this field is the Galleri test (from GRAIL) which is already in clinical use in some health care networks across the United States. That test uses next-generation sequencing to analyze the arrangement of methyl groups on circulating tumor (or cell-free) DNA (cfDNA) in a blood sample.

The new test, under development by Swedish biotechnology company Elypta AB, has a different premise. It can detect 14 cancer types based on the analysis of glycosaminoglycans, which are a diverse group of polysaccharides that are altered by the presence of tumors. Using plasma and urine samples, the method had a 41.6%-62.3% sensitivity for detecting stage I cancer at 95% specificity.

In comparison, say the authors, other assays have reported 39%-73% sensitivity to stage I cancers, but these estimates are usually limited to 12 cancer types that are considered “high-signal,” and the assays perform poorly in cancers that emit little cfDNA, such as genitourinary and brain malignancies.

“The main advantage of glycosaminoglycans appears to be that they change in the blood and urine at the earliest stages of cancer,” said study author Francesco Gatto, PhD, founder and chief scientific officer at Elypta. “Consequently, this method showed an impressive detection rate in stage I compared to other emerging methods.”

The study was published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Combine tests?

Dr. Gatto commented that he “could envision that one day we may be able to combine these methods.”

“The same blood specimen could be used to test both glycosaminoglycans and genomic biomarkers,” said Dr. Gatto. “This strategy could hopefully detect even more cancers than with either method alone, and the resulting performance may well be sufficient as a one-stop-shop screening program.”

So how does the new test from Elypta compare with the Galleri test?

“Galleri and similar methods mostly focused on information coming from molecules of DNA naturally floating in the blood,” explained Dr. Gatto. “It makes sense to conduct research there because cancers typically start with events in the DNA.”

He noted that the current study explored a new layer of information, molecules called glycosaminoglycans, that participate in the metabolism of cancer.

“This method detected many cancers that the previous methods missed, and a substantial proportion of these were at stage I,” said Dr. Gatto. “Cancer is a complex disease, so the most layers of information we can probe noninvasively, say with a blood test, the more likely we can catch more cancers at its earliest stage.”

Other platforms typically rely on sequencing and detecting cancer-derived fractions of cfDNA, but these methods have challenges that can interfere with their usage. For example, some cancer types do not shed sufficient cfDNA and it cannot be accurately measured.

“An advantage on focusing on glycosaminoglycans is that the method does not require next-generation sequencing or similarly complex assays because glycosaminoglycans are informative with less than 10 simultaneous measurements as opposed to Galleri that looks at over 1 million DNA methylation sites,” he said.

“This makes the assay behind the test much cheaper and robust – we estimated a 5-10 times lower cost difference,” Dr. Gatto said.

Prospective and comparative data needed

In a comment, Eric Klein, MD, emeritus chair of the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute at the Cleveland Clinic explained that the “only accurate way to know how a test will perform in an intended-use population is to actually test it in that population. It’s not possible to extrapolate results directly from a case-control study.”

Cancers shed many different biologic markers into body fluids, but which of these signals will be best to serve as the basis of an MCED (multi-cancer detection test) that has clinical utility in a screening population has yet to be determined, he noted. “And it’s possible that no single test will be optimum for every clinical situation.”

“The results of this study appear promising, but it is not possible to claim superiority of one test over another based on individual case-control studies because of uncontrolled differences in the selected populations,” Dr. Klein continued. “The only scientifically accurate way to do this is to perform different tests on the same patient samples in a head-to-head comparison.”

There is only one study that he is aware of that has done this recently, in which multiple different assays looking at various signals in cell-free DNA were directly compared on the same samples (Cancer cell. 2022;40:1537-49.e12). “A targeted methylation assay that is the basis for Galleri was best for the lowest limit of detection and for predicting cancer site of origin,” said Dr. Klein.

Another expert agreed that a direct head-to-head study is needed to compare assays. “Based on this data, you cannot say that this method is better than the other one because that requires a comparative study,” said Fred Hirsch, MD, PhD, executive director of the Center for Thoracic Oncology, Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai, New York.

Metabolomics is interesting, and the data are encouraging, he continued. “But this is a multicancer early detection test and metabolism changes may vary from cancer type to cancer type. I’m not sure that the metabolism of lung cancer is the same as that of a gynecologic cancer.”

Dr. Hirsch also pointed out that there could also be confounding factors. “They have excluded inflammatory disease, but there can be other variables such as smoking,” he said. “Overall it gives some interesting perspectives but I would like to see more prospective validation and studies in specific disease groups, and eventually comparative studies with other methodologies.”

Study details

The authors evaluated if plasma and urine free GAGomes (free glycosaminoglycan profiles) deviated from baseline physiological levels in 14 cancer types and could serve as metabolic cancer biomarkers. They also then validated using free GAGomes for MCED in an external population with 2,064 samples obtained from 1,260 patients with cancer and healthy individuals.

In an in vivo cancer progression model, they observed widespread cancer-specific changes in biofluidic free GAGomes and then developed three machine-learning models based on urine (nurine = 220 cancer vs. 360 healthy) and plasma (nplasma = 517 cancer vs. 425 healthy) free GAGomes that were able to detect any cancer with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.83-0.93 (with up to 62% sensitivity to stage I disease at 95% specificity).

To assess if altered GAGome features associated with cancer suggested more aggressive tumor biology, they correlated each score with overall survival. The median follow-up time was 17 months in the plasma cohort (n = 370 across 13 cancer types), 15 months in the urine cohort (n = 162 across 4 cancer types), and 15 months in the combined cohort (n = 152 across 4 cancer types).

They found that all three scores independently predicted overall survival in a multivariable analysis (hazard ratio, 1.29; P = .0009 for plasma; HR, 1.79; P = .0009 for urine; HR, 1.91; P = .0004 for combined) after adjusting for cancer type, age, sex, and stage IV or high-grade disease.

These findings showed an association of free GAGome alterations with aggressive cancer phenotypes and suggested that scores below the 95% specificity cutoff might have a better prognosis, the authors comment.

In addition, other analyses showed that free GAGomes predicted the putative cancer location with 89% accuracy. And finally, to confirm whether the free GAGome MCED scores could be used for screening, a validation analysis was conducted using a typical “screening population,” which requires at least 99% specificity. The combined free GAGomes were able to predict a poor prognosis of any cancer type within 18 months and with 43% sensitivity (21% in stage I; n = 121 and 49 cases).

Dr. Gatto believes that these results, as well as those from other studies looking at glycosaminoglycans as cancer biomarkers, will lead to the next steps of development. “But I speculate that this test could be most useful to assess in a cheap, practical, and noninvasive manner if a person at increased risk of cancer should be selected for cancer screening as part of established or emerging screening programs.”

The study was sponsored by Elypta. Dr. Gatto is listed as an inventor in patent applications related to the biomarkers described in this study and later assigned to Elypta, and is a shareholder and employed at Elypta. Dr. Hirsch reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Klein is a consultant for GRAIL and an investigator for CCGA and Pathfinder.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The leader in this field is the Galleri test (from GRAIL) which is already in clinical use in some health care networks across the United States. That test uses next-generation sequencing to analyze the arrangement of methyl groups on circulating tumor (or cell-free) DNA (cfDNA) in a blood sample.

The new test, under development by Swedish biotechnology company Elypta AB, has a different premise. It can detect 14 cancer types based on the analysis of glycosaminoglycans, which are a diverse group of polysaccharides that are altered by the presence of tumors. Using plasma and urine samples, the method had a 41.6%-62.3% sensitivity for detecting stage I cancer at 95% specificity.

In comparison, say the authors, other assays have reported 39%-73% sensitivity to stage I cancers, but these estimates are usually limited to 12 cancer types that are considered “high-signal,” and the assays perform poorly in cancers that emit little cfDNA, such as genitourinary and brain malignancies.

“The main advantage of glycosaminoglycans appears to be that they change in the blood and urine at the earliest stages of cancer,” said study author Francesco Gatto, PhD, founder and chief scientific officer at Elypta. “Consequently, this method showed an impressive detection rate in stage I compared to other emerging methods.”

The study was published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Combine tests?

Dr. Gatto commented that he “could envision that one day we may be able to combine these methods.”

“The same blood specimen could be used to test both glycosaminoglycans and genomic biomarkers,” said Dr. Gatto. “This strategy could hopefully detect even more cancers than with either method alone, and the resulting performance may well be sufficient as a one-stop-shop screening program.”

So how does the new test from Elypta compare with the Galleri test?

“Galleri and similar methods mostly focused on information coming from molecules of DNA naturally floating in the blood,” explained Dr. Gatto. “It makes sense to conduct research there because cancers typically start with events in the DNA.”

He noted that the current study explored a new layer of information, molecules called glycosaminoglycans, that participate in the metabolism of cancer.

“This method detected many cancers that the previous methods missed, and a substantial proportion of these were at stage I,” said Dr. Gatto. “Cancer is a complex disease, so the most layers of information we can probe noninvasively, say with a blood test, the more likely we can catch more cancers at its earliest stage.”

Other platforms typically rely on sequencing and detecting cancer-derived fractions of cfDNA, but these methods have challenges that can interfere with their usage. For example, some cancer types do not shed sufficient cfDNA and it cannot be accurately measured.

“An advantage on focusing on glycosaminoglycans is that the method does not require next-generation sequencing or similarly complex assays because glycosaminoglycans are informative with less than 10 simultaneous measurements as opposed to Galleri that looks at over 1 million DNA methylation sites,” he said.

“This makes the assay behind the test much cheaper and robust – we estimated a 5-10 times lower cost difference,” Dr. Gatto said.

Prospective and comparative data needed

In a comment, Eric Klein, MD, emeritus chair of the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute at the Cleveland Clinic explained that the “only accurate way to know how a test will perform in an intended-use population is to actually test it in that population. It’s not possible to extrapolate results directly from a case-control study.”

Cancers shed many different biologic markers into body fluids, but which of these signals will be best to serve as the basis of an MCED (multi-cancer detection test) that has clinical utility in a screening population has yet to be determined, he noted. “And it’s possible that no single test will be optimum for every clinical situation.”

“The results of this study appear promising, but it is not possible to claim superiority of one test over another based on individual case-control studies because of uncontrolled differences in the selected populations,” Dr. Klein continued. “The only scientifically accurate way to do this is to perform different tests on the same patient samples in a head-to-head comparison.”

There is only one study that he is aware of that has done this recently, in which multiple different assays looking at various signals in cell-free DNA were directly compared on the same samples (Cancer cell. 2022;40:1537-49.e12). “A targeted methylation assay that is the basis for Galleri was best for the lowest limit of detection and for predicting cancer site of origin,” said Dr. Klein.

Another expert agreed that a direct head-to-head study is needed to compare assays. “Based on this data, you cannot say that this method is better than the other one because that requires a comparative study,” said Fred Hirsch, MD, PhD, executive director of the Center for Thoracic Oncology, Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai, New York.

Metabolomics is interesting, and the data are encouraging, he continued. “But this is a multicancer early detection test and metabolism changes may vary from cancer type to cancer type. I’m not sure that the metabolism of lung cancer is the same as that of a gynecologic cancer.”

Dr. Hirsch also pointed out that there could also be confounding factors. “They have excluded inflammatory disease, but there can be other variables such as smoking,” he said. “Overall it gives some interesting perspectives but I would like to see more prospective validation and studies in specific disease groups, and eventually comparative studies with other methodologies.”

Study details

The authors evaluated if plasma and urine free GAGomes (free glycosaminoglycan profiles) deviated from baseline physiological levels in 14 cancer types and could serve as metabolic cancer biomarkers. They also then validated using free GAGomes for MCED in an external population with 2,064 samples obtained from 1,260 patients with cancer and healthy individuals.

In an in vivo cancer progression model, they observed widespread cancer-specific changes in biofluidic free GAGomes and then developed three machine-learning models based on urine (nurine = 220 cancer vs. 360 healthy) and plasma (nplasma = 517 cancer vs. 425 healthy) free GAGomes that were able to detect any cancer with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.83-0.93 (with up to 62% sensitivity to stage I disease at 95% specificity).

To assess if altered GAGome features associated with cancer suggested more aggressive tumor biology, they correlated each score with overall survival. The median follow-up time was 17 months in the plasma cohort (n = 370 across 13 cancer types), 15 months in the urine cohort (n = 162 across 4 cancer types), and 15 months in the combined cohort (n = 152 across 4 cancer types).

They found that all three scores independently predicted overall survival in a multivariable analysis (hazard ratio, 1.29; P = .0009 for plasma; HR, 1.79; P = .0009 for urine; HR, 1.91; P = .0004 for combined) after adjusting for cancer type, age, sex, and stage IV or high-grade disease.

These findings showed an association of free GAGome alterations with aggressive cancer phenotypes and suggested that scores below the 95% specificity cutoff might have a better prognosis, the authors comment.

In addition, other analyses showed that free GAGomes predicted the putative cancer location with 89% accuracy. And finally, to confirm whether the free GAGome MCED scores could be used for screening, a validation analysis was conducted using a typical “screening population,” which requires at least 99% specificity. The combined free GAGomes were able to predict a poor prognosis of any cancer type within 18 months and with 43% sensitivity (21% in stage I; n = 121 and 49 cases).

Dr. Gatto believes that these results, as well as those from other studies looking at glycosaminoglycans as cancer biomarkers, will lead to the next steps of development. “But I speculate that this test could be most useful to assess in a cheap, practical, and noninvasive manner if a person at increased risk of cancer should be selected for cancer screening as part of established or emerging screening programs.”

The study was sponsored by Elypta. Dr. Gatto is listed as an inventor in patent applications related to the biomarkers described in this study and later assigned to Elypta, and is a shareholder and employed at Elypta. Dr. Hirsch reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Klein is a consultant for GRAIL and an investigator for CCGA and Pathfinder.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The leader in this field is the Galleri test (from GRAIL) which is already in clinical use in some health care networks across the United States. That test uses next-generation sequencing to analyze the arrangement of methyl groups on circulating tumor (or cell-free) DNA (cfDNA) in a blood sample.

The new test, under development by Swedish biotechnology company Elypta AB, has a different premise. It can detect 14 cancer types based on the analysis of glycosaminoglycans, which are a diverse group of polysaccharides that are altered by the presence of tumors. Using plasma and urine samples, the method had a 41.6%-62.3% sensitivity for detecting stage I cancer at 95% specificity.

In comparison, say the authors, other assays have reported 39%-73% sensitivity to stage I cancers, but these estimates are usually limited to 12 cancer types that are considered “high-signal,” and the assays perform poorly in cancers that emit little cfDNA, such as genitourinary and brain malignancies.

“The main advantage of glycosaminoglycans appears to be that they change in the blood and urine at the earliest stages of cancer,” said study author Francesco Gatto, PhD, founder and chief scientific officer at Elypta. “Consequently, this method showed an impressive detection rate in stage I compared to other emerging methods.”

The study was published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Combine tests?

Dr. Gatto commented that he “could envision that one day we may be able to combine these methods.”

“The same blood specimen could be used to test both glycosaminoglycans and genomic biomarkers,” said Dr. Gatto. “This strategy could hopefully detect even more cancers than with either method alone, and the resulting performance may well be sufficient as a one-stop-shop screening program.”

So how does the new test from Elypta compare with the Galleri test?

“Galleri and similar methods mostly focused on information coming from molecules of DNA naturally floating in the blood,” explained Dr. Gatto. “It makes sense to conduct research there because cancers typically start with events in the DNA.”

He noted that the current study explored a new layer of information, molecules called glycosaminoglycans, that participate in the metabolism of cancer.

“This method detected many cancers that the previous methods missed, and a substantial proportion of these were at stage I,” said Dr. Gatto. “Cancer is a complex disease, so the most layers of information we can probe noninvasively, say with a blood test, the more likely we can catch more cancers at its earliest stage.”

Other platforms typically rely on sequencing and detecting cancer-derived fractions of cfDNA, but these methods have challenges that can interfere with their usage. For example, some cancer types do not shed sufficient cfDNA and it cannot be accurately measured.

“An advantage on focusing on glycosaminoglycans is that the method does not require next-generation sequencing or similarly complex assays because glycosaminoglycans are informative with less than 10 simultaneous measurements as opposed to Galleri that looks at over 1 million DNA methylation sites,” he said.

“This makes the assay behind the test much cheaper and robust – we estimated a 5-10 times lower cost difference,” Dr. Gatto said.

Prospective and comparative data needed

In a comment, Eric Klein, MD, emeritus chair of the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute at the Cleveland Clinic explained that the “only accurate way to know how a test will perform in an intended-use population is to actually test it in that population. It’s not possible to extrapolate results directly from a case-control study.”

Cancers shed many different biologic markers into body fluids, but which of these signals will be best to serve as the basis of an MCED (multi-cancer detection test) that has clinical utility in a screening population has yet to be determined, he noted. “And it’s possible that no single test will be optimum for every clinical situation.”

“The results of this study appear promising, but it is not possible to claim superiority of one test over another based on individual case-control studies because of uncontrolled differences in the selected populations,” Dr. Klein continued. “The only scientifically accurate way to do this is to perform different tests on the same patient samples in a head-to-head comparison.”

There is only one study that he is aware of that has done this recently, in which multiple different assays looking at various signals in cell-free DNA were directly compared on the same samples (Cancer cell. 2022;40:1537-49.e12). “A targeted methylation assay that is the basis for Galleri was best for the lowest limit of detection and for predicting cancer site of origin,” said Dr. Klein.

Another expert agreed that a direct head-to-head study is needed to compare assays. “Based on this data, you cannot say that this method is better than the other one because that requires a comparative study,” said Fred Hirsch, MD, PhD, executive director of the Center for Thoracic Oncology, Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai, New York.

Metabolomics is interesting, and the data are encouraging, he continued. “But this is a multicancer early detection test and metabolism changes may vary from cancer type to cancer type. I’m not sure that the metabolism of lung cancer is the same as that of a gynecologic cancer.”

Dr. Hirsch also pointed out that there could also be confounding factors. “They have excluded inflammatory disease, but there can be other variables such as smoking,” he said. “Overall it gives some interesting perspectives but I would like to see more prospective validation and studies in specific disease groups, and eventually comparative studies with other methodologies.”

Study details

The authors evaluated if plasma and urine free GAGomes (free glycosaminoglycan profiles) deviated from baseline physiological levels in 14 cancer types and could serve as metabolic cancer biomarkers. They also then validated using free GAGomes for MCED in an external population with 2,064 samples obtained from 1,260 patients with cancer and healthy individuals.

In an in vivo cancer progression model, they observed widespread cancer-specific changes in biofluidic free GAGomes and then developed three machine-learning models based on urine (nurine = 220 cancer vs. 360 healthy) and plasma (nplasma = 517 cancer vs. 425 healthy) free GAGomes that were able to detect any cancer with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.83-0.93 (with up to 62% sensitivity to stage I disease at 95% specificity).

To assess if altered GAGome features associated with cancer suggested more aggressive tumor biology, they correlated each score with overall survival. The median follow-up time was 17 months in the plasma cohort (n = 370 across 13 cancer types), 15 months in the urine cohort (n = 162 across 4 cancer types), and 15 months in the combined cohort (n = 152 across 4 cancer types).

They found that all three scores independently predicted overall survival in a multivariable analysis (hazard ratio, 1.29; P = .0009 for plasma; HR, 1.79; P = .0009 for urine; HR, 1.91; P = .0004 for combined) after adjusting for cancer type, age, sex, and stage IV or high-grade disease.

These findings showed an association of free GAGome alterations with aggressive cancer phenotypes and suggested that scores below the 95% specificity cutoff might have a better prognosis, the authors comment.

In addition, other analyses showed that free GAGomes predicted the putative cancer location with 89% accuracy. And finally, to confirm whether the free GAGome MCED scores could be used for screening, a validation analysis was conducted using a typical “screening population,” which requires at least 99% specificity. The combined free GAGomes were able to predict a poor prognosis of any cancer type within 18 months and with 43% sensitivity (21% in stage I; n = 121 and 49 cases).

Dr. Gatto believes that these results, as well as those from other studies looking at glycosaminoglycans as cancer biomarkers, will lead to the next steps of development. “But I speculate that this test could be most useful to assess in a cheap, practical, and noninvasive manner if a person at increased risk of cancer should be selected for cancer screening as part of established or emerging screening programs.”

The study was sponsored by Elypta. Dr. Gatto is listed as an inventor in patent applications related to the biomarkers described in this study and later assigned to Elypta, and is a shareholder and employed at Elypta. Dr. Hirsch reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Klein is a consultant for GRAIL and an investigator for CCGA and Pathfinder.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Have you heard the one about the cow in the doctor’s office?

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Should you quit employment to open a practice? These docs share how they did it

“Everyone said private practice is dying,” said Omar Maniya, MD, an emergency physician who left his hospital job for family practice in New Jersey. “But I think it could be one of the best models we have to advance our health care system and prevent burnout – and bring joy back to the practice of medicine.”

But employment doesn’t necessarily mean happiness. In the Medscape “Employed Physicians: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy” ” report, more than 1,350 U.S. physicians employed by a health care organization, hospital, large group practice, or other medical group were surveyedabout their work. As the subtitle suggests, many are torn.

In the survey, employed doctors cited three main downsides to the lifestyle: They have less autonomy, more corporate rules than they’d like, and lower earning potential. Nearly one-third say they’re unhappy about their work-life balance, too, which raises the risk for burnout.

Some physicians find that employment has more cons than pros and turn to private practice instead.

A system skewed toward employment

In the mid-1990s, when James Milford, MD, completed his residency, going straight into private practice was the norm. The family physician bucked that trend by joining a large regional medical center in Wisconsin. He spent the next 20+ years working to establish a network of medical clinics.

“It was very satisfying,” Dr. Milford said. “When I started, I had a lot of input, a lot of control.”

Since then, the pendulum has been swinging toward employment. Brieanna Seefeldt, DO, a family physician outside Denver, completed her residency in 2012.

“I told the recruiter I wanted my own practice,” Dr. Seefeldt said, “They said if you’re not independently wealthy, there’s no way.”

Sonal G. Patel, MD, a pediatric neurologist in Bethesda, finished her residency the same year as Dr. Seefeldt. Dr. Patel never even considered private practice.

“I always thought I would have a certain amount of clinic time where I have my regular patients,” she said, “but I’d also be doing hospital rounds and reading EEG studies at the hospital.”

For Dr. Maniya, who completed his residency in 2021, the choice was simple. Growing up, he watched his immigrant parents, both doctors in private practice, struggle to keep up.

“I opted for a big, sophisticated health system,” he said. “I thought we’d be pushing the envelope of what was possible in medicine.”

Becoming disillusioned with employment

All four of these physicians are now in private practice and are much happier.

Within a few years of starting her job, Dr. Seefeldt was one of the top producers in her area but felt tremendous pressure to see more and more patients. The last straw came after an unpaid maternity leave.

“They told me I owed them for my maternity leave, for lack of productivity,” she said. “I was in practice for only 4 years, but already feeling the effects of burnout.”

Dr. Patel only lasted 2 years before realizing employment didn’t suit her.

“There was an excessive amount of hospital calls,” she said. “And there were bureaucratic issues that made it very difficult to practice the way I thought my practice would be.”

It took just 18 months for Dr. Maniya’s light-bulb moment. He was working at a hospital when COVID-19 hit.

“At my big health care system, it took 9 months to come up with a way to get COVID swabs for free,” he said. “At the same time, I was helping out the family business, a private practice. It took me two calls and 48 hours to get free swabs for not just the practice, not just our patients, but the entire city of Hamilton, New Jersey.”

Milford lasted the longest as an employee – nearly 25 years. The end came after a healthcare company with hospitals in 30 states bought out the medical center.

“My control gradually eroded,” he said. “It got to the point where I had no input regarding things like employees or processes we wanted to improve.”

Making the leap to private practice

Private practice can take different forms.

Dr. Seefeldt opted for direct primary care, a model in which her patients pay a set monthly fee for care whenever needed. Her practice doesn’t take any insurance besides Medicaid.

“Direct primary care is about working directly with the patient and cost-conscious, transparent care,” she said. “And I don’t have to deal with insurance.”

For Dr. Patel, working with an accountable care organization made the transition easier. She owns her practice solo but works with a company called Privia for administrative needs. Privia sent a consultant to set up her office in the company’s electronic medical record. Things were up and running within the first week.

Dr. Maniya joined his mother’s practice, easing his way in over 18 months.

And then there’s what Milford did, building a private practice from the ground up.

“We did a lot of Googling, a lot of meeting with accountants, meeting with small business development from the state of Wisconsin,” he said. “We asked people that were in business, ‘What are the things businesses fail on? Not medical practices, but businesses.’” All that research helped him launch successfully.

Making the dollars and cents add up

Moving from employment into private practice takes time, effort, and of course, money. How much of each varies depending on where you live, your specialty, whether you choose to rent or buy office space, staffing needs, and other factors.

Dr. Seefeldt, Dr. Patel, Dr. Milford, and Dr. Maniya illustrate the range.

- Dr. Seefeldt got a home equity loan of $50,000 to cover startup costs – and paid it back within 6 months.

- Purchasing EEG equipment added to Dr. Patel’s budget; she spent $130,000 of her own money to launch her practice in a temporary office and took out a $150,000 loan to finance the buildout of her final space. It took her 3 years to pay it back.

- When Dr. Milford left employment, he borrowed the buildout and startup costs for his practice from his father, a retired surgeon, to the tune of $500,000.

- Dr. Maniya assumed the largest risk. When he took over the family practice, he borrowed $1.5 million to modernize and build a new office. The practice has now quintupled in size. “It’s going great,” he said. “One of our questions is, should we pay back the loan at a faster pace rather than make the minimum payments?”

Several years in, Dr. Patel reports she’s easily making three to four times as much as she would have at a hospital. However, Dr. Maniya’s guaranteed compensation is 10% less than his old job.

“But as a partner in a private practice, if it succeeds, it could be 100%-150% more in a good year,” he said. On the flip side, if the practice runs into financial trouble, so does he. “Does the risk keep me up at night, give me heartburn? You betcha.”

Dr. Milford and Dr. Seefeldt have both chosen to take less compensation than they could, opting to reinvest in and nurture their practices.

“I love it,” said Dr. Milford. “I joke that I have half as much in my pocketbook, twice as much in my heart. But it’s not really half as much, 5 years in. If I weren’t growing the business, I’d be making more than before.”

Private practice is not without challenges

Being the big cheese does have drawbacks. In the current climate, staffing is a persistent issue for doctors in private practice – both maintaining a full staff and managing their employees.

And without the backing of a large corporation, doctors are sometimes called on to do less than pleasant tasks.

“If the toilet gets clogged and the plumber can’t come for a few hours, the patients still need a bathroom,” Dr. Maniya said. “I’ll go in with my $400 shoes and snake the toilet.”

Dr. Milford pointed out that when the buck stops with you, small mistakes can have enormous ramifications. “But with the bad comes the great potential for good. You have the ability to positively affect patients and healthcare, and to make a difference for people. It creates great personal satisfaction.”

Is running your own practice all it’s cracked up to be?

If it’s not yet apparent, all four doctors highly recommend moving from employment to private practice when possible. The autonomy and the improved work-life balance have helped them find the satisfaction they’d been missing while making burnout less likely.

“When you don’t have to spend 30% of your day apologizing to patients for how bad the health care system is, it reignites your passion for why you went into medicine in the first place,” said Dr. Maniya. In his practice, he’s made a conscious decision to pursue a mix of demographics. “Thirty percent of our patients are Medicaid. The vast majority are middle to low income.”

For physicians who are also parents, the ability to set their own schedules is life-changing.

“My son got an award ... and the teacher invited me to the assembly. In a corporate-based world, I’d struggle to be able to go,” said Dr. Seefeldt. As her own boss, she didn’t have to forgo this special event. Instead, she coordinated directly with her scheduled patient to make time for it.

In Medscape’s report, 61% of employed physicians indicated that they don’t have a say on key management decisions. However, doctors who launch private practices embrace the chance to set their own standards.

“We make sure from the minute someone calls they know they’re in good hands, we’re responsive, we address concerns right away. That’s the difference with private practice – the one-on-one connection is huge,” said Dr. Patel.

“This is exactly what I always wanted. It brings me joy knowing we’ve made a difference in these children’s lives, in their parents’ lives,” she concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Everyone said private practice is dying,” said Omar Maniya, MD, an emergency physician who left his hospital job for family practice in New Jersey. “But I think it could be one of the best models we have to advance our health care system and prevent burnout – and bring joy back to the practice of medicine.”

But employment doesn’t necessarily mean happiness. In the Medscape “Employed Physicians: Loving the Focus, Hating the Bureaucracy” ” report, more than 1,350 U.S. physicians employed by a health care organization, hospital, large group practice, or other medical group were surveyedabout their work. As the subtitle suggests, many are torn.

In the survey, employed doctors cited three main downsides to the lifestyle: They have less autonomy, more corporate rules than they’d like, and lower earning potential. Nearly one-third say they’re unhappy about their work-life balance, too, which raises the risk for burnout.

Some physicians find that employment has more cons than pros and turn to private practice instead.

A system skewed toward employment

In the mid-1990s, when James Milford, MD, completed his residency, going straight into private practice was the norm. The family physician bucked that trend by joining a large regional medical center in Wisconsin. He spent the next 20+ years working to establish a network of medical clinics.

“It was very satisfying,” Dr. Milford said. “When I started, I had a lot of input, a lot of control.”

Since then, the pendulum has been swinging toward employment. Brieanna Seefeldt, DO, a family physician outside Denver, completed her residency in 2012.

“I told the recruiter I wanted my own practice,” Dr. Seefeldt said, “They said if you’re not independently wealthy, there’s no way.”

Sonal G. Patel, MD, a pediatric neurologist in Bethesda, finished her residency the same year as Dr. Seefeldt. Dr. Patel never even considered private practice.

“I always thought I would have a certain amount of clinic time where I have my regular patients,” she said, “but I’d also be doing hospital rounds and reading EEG studies at the hospital.”

For Dr. Maniya, who completed his residency in 2021, the choice was simple. Growing up, he watched his immigrant parents, both doctors in private practice, struggle to keep up.

“I opted for a big, sophisticated health system,” he said. “I thought we’d be pushing the envelope of what was possible in medicine.”

Becoming disillusioned with employment

All four of these physicians are now in private practice and are much happier.

Within a few years of starting her job, Dr. Seefeldt was one of the top producers in her area but felt tremendous pressure to see more and more patients. The last straw came after an unpaid maternity leave.

“They told me I owed them for my maternity leave, for lack of productivity,” she said. “I was in practice for only 4 years, but already feeling the effects of burnout.”

Dr. Patel only lasted 2 years before realizing employment didn’t suit her.

“There was an excessive amount of hospital calls,” she said. “And there were bureaucratic issues that made it very difficult to practice the way I thought my practice would be.”

It took just 18 months for Dr. Maniya’s light-bulb moment. He was working at a hospital when COVID-19 hit.

“At my big health care system, it took 9 months to come up with a way to get COVID swabs for free,” he said. “At the same time, I was helping out the family business, a private practice. It took me two calls and 48 hours to get free swabs for not just the practice, not just our patients, but the entire city of Hamilton, New Jersey.”