User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Mask-wearing cuts new COVID-19 cases by 53%, study says

Social distancing and handwashing were also effective at lowering the number of cases, but wearing masks was the most effective tool against the coronavirus.

“Personal and social measures, including handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing are effective at reducing the incidence of COVID-19,” the study authors wrote.

The research team, which included public health and infectious disease specialists in Australia, China, and the U.K., evaluated 72 studies of COVID-19 precautions during the pandemic. They later looked at eight studies that focused on handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing.

Among six studies that looked at mask wearing, the researchers found a 53% reduction in COVID-19 cases. In the broader analysis with additional studies, wearing a mask reduced coronavirus transmission, cases, and deaths.

In one study across 200 countries, mandatory mask wearing resulted in nearly 46% fewer negative outcomes from COVID-19. In another study in the U.S., coronavirus transmission was reduced 29% in states where masks were mandatory.

But the research team couldn’t analyze the impact of the type of face mask used, the frequency of mask wearing, or the overall compliance with wearing face masks.

Among five studies that looked at physical distancing, the researchers found a 25% reduction in the rate of COVID-19. A study in the U.S. showed a 12% decrease in coronavirus transmission, while another study in Iran reported a reduction in COVID-19 mortality.

Handwashing interventions also suggested a substantial reduction of COVID-19 cases up to 53%, the researchers wrote. But in adjusted models, the results weren’t statistically significant due to the small number of studies included.

Other studies found significant decreases related to other public health measures, such as quarantines, broad lockdowns, border closures, school closures, business closures, and travel restrictions. Still, the research team couldn’t analyze the overall effectiveness of these measures due to the different ways the studies were conducted.

The study lines up with other research conducted so far during the pandemic, the research team wrote, which indicates that wearing masks and physical distancing can reduce transmission, cases, and deaths.

That said, more studies are needed, particularly now that vaccinations are available and contagious coronavirus variants have become prevalent.

“Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of public health measures after adequate vaccination coverage has been achieved,” they wrote.

“It is likely that further control of the COVID-19 pandemic depends not only on high vaccination coverage and its effectiveness but also on ongoing adherence to effective and sustainable public health measures,” they concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Social distancing and handwashing were also effective at lowering the number of cases, but wearing masks was the most effective tool against the coronavirus.

“Personal and social measures, including handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing are effective at reducing the incidence of COVID-19,” the study authors wrote.

The research team, which included public health and infectious disease specialists in Australia, China, and the U.K., evaluated 72 studies of COVID-19 precautions during the pandemic. They later looked at eight studies that focused on handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing.

Among six studies that looked at mask wearing, the researchers found a 53% reduction in COVID-19 cases. In the broader analysis with additional studies, wearing a mask reduced coronavirus transmission, cases, and deaths.

In one study across 200 countries, mandatory mask wearing resulted in nearly 46% fewer negative outcomes from COVID-19. In another study in the U.S., coronavirus transmission was reduced 29% in states where masks were mandatory.

But the research team couldn’t analyze the impact of the type of face mask used, the frequency of mask wearing, or the overall compliance with wearing face masks.

Among five studies that looked at physical distancing, the researchers found a 25% reduction in the rate of COVID-19. A study in the U.S. showed a 12% decrease in coronavirus transmission, while another study in Iran reported a reduction in COVID-19 mortality.

Handwashing interventions also suggested a substantial reduction of COVID-19 cases up to 53%, the researchers wrote. But in adjusted models, the results weren’t statistically significant due to the small number of studies included.

Other studies found significant decreases related to other public health measures, such as quarantines, broad lockdowns, border closures, school closures, business closures, and travel restrictions. Still, the research team couldn’t analyze the overall effectiveness of these measures due to the different ways the studies were conducted.

The study lines up with other research conducted so far during the pandemic, the research team wrote, which indicates that wearing masks and physical distancing can reduce transmission, cases, and deaths.

That said, more studies are needed, particularly now that vaccinations are available and contagious coronavirus variants have become prevalent.

“Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of public health measures after adequate vaccination coverage has been achieved,” they wrote.

“It is likely that further control of the COVID-19 pandemic depends not only on high vaccination coverage and its effectiveness but also on ongoing adherence to effective and sustainable public health measures,” they concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Social distancing and handwashing were also effective at lowering the number of cases, but wearing masks was the most effective tool against the coronavirus.

“Personal and social measures, including handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing are effective at reducing the incidence of COVID-19,” the study authors wrote.

The research team, which included public health and infectious disease specialists in Australia, China, and the U.K., evaluated 72 studies of COVID-19 precautions during the pandemic. They later looked at eight studies that focused on handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing.

Among six studies that looked at mask wearing, the researchers found a 53% reduction in COVID-19 cases. In the broader analysis with additional studies, wearing a mask reduced coronavirus transmission, cases, and deaths.

In one study across 200 countries, mandatory mask wearing resulted in nearly 46% fewer negative outcomes from COVID-19. In another study in the U.S., coronavirus transmission was reduced 29% in states where masks were mandatory.

But the research team couldn’t analyze the impact of the type of face mask used, the frequency of mask wearing, or the overall compliance with wearing face masks.

Among five studies that looked at physical distancing, the researchers found a 25% reduction in the rate of COVID-19. A study in the U.S. showed a 12% decrease in coronavirus transmission, while another study in Iran reported a reduction in COVID-19 mortality.

Handwashing interventions also suggested a substantial reduction of COVID-19 cases up to 53%, the researchers wrote. But in adjusted models, the results weren’t statistically significant due to the small number of studies included.

Other studies found significant decreases related to other public health measures, such as quarantines, broad lockdowns, border closures, school closures, business closures, and travel restrictions. Still, the research team couldn’t analyze the overall effectiveness of these measures due to the different ways the studies were conducted.

The study lines up with other research conducted so far during the pandemic, the research team wrote, which indicates that wearing masks and physical distancing can reduce transmission, cases, and deaths.

That said, more studies are needed, particularly now that vaccinations are available and contagious coronavirus variants have become prevalent.

“Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of public health measures after adequate vaccination coverage has been achieved,” they wrote.

“It is likely that further control of the COVID-19 pandemic depends not only on high vaccination coverage and its effectiveness but also on ongoing adherence to effective and sustainable public health measures,” they concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE BMJ

Growing evidence supports repurposing antidepressants to treat COVID-19

Mounting evidence suggests selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are associated with lower COVID-19 severity.

A large analysis of health records shows patients with COVID-19 taking an SSRI were significantly less likely to die of COVID-19 than a matched control group.

“We can’t tell if the drugs are causing these effects, but the statistical analysis is showing significant association. There’s power in the numbers,” Marina Sirota, PhD, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), said in a statement.

The study was published online Nov. 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Data-driven approach

, including 3,401 patients who were prescribed SSRIs.

When compared with matched patients with COVID-19 taking SSRIs, patients taking fluoxetine were 28% less likely to die (relative risk, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.54-0.97; adjusted P = .03) and those taking either fluoxetine or fluvoxamine were 26% less likely to die (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-0.99; adjusted P = .04) versus those not on these medications.

Patients with COVID-19 taking any kind of SSRI were 8% less likely to die than the matched controls (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-0.99; adjusted P = .03).

“We observed a statistically significant reduction in mortality of COVID-19 patients who were already taking SSRIs. This is a demonstration of a data-driven approach for identifying new uses for existing drugs,” Dr. Sirota said in an interview.

“Our study simply shows an association between SSRIs and COVID-19 outcomes and doesn’t investigate the mechanism of action of why the drugs might work. Additional clinical trials need to be carried out before these drugs can be used in patients going forward,” she cautioned.

“There is currently an open-label trial investigating fluoxetine to reduce intubation and death after COVID-19. To our knowledge, there are no phase 3 randomized controlled trials taking place or planned,” study investigator Tomiko Oskotsky, MD, with UCSF, told this news organization.

Urgent need

The current results “confirm and expand on prior findings from observational, preclinical, and clinical studies suggesting that certain SSRI antidepressants, including fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, could be beneficial against COVID-19,” Nicolas Hoertel, MD, PhD, MPH, with Paris University and Corentin-Celton Hospital, France, writes in a linked editorial.

Dr. Hoertel notes that the anti-inflammatory properties of SSRIs may underlie their potential action against COVID-19, and other potential mechanisms may include reduction in platelet aggregation, decreased mast cell degranulation, increased melatonin levels, interference with endolysosomal viral trafficking, and antioxidant activities.

“Because most of the world’s population is currently unvaccinated and the COVID-19 pandemic is still active, effective treatments of COVID-19 – especially those that are easy to use, show good tolerability, can be administered orally, and have widespread availability at low cost to allow their use in resource-poor countries – are urgently needed to reduce COVID-19-related mortality and morbidity,” Dr. Hoertel points out.

“In this context, short-term use of fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, if proven effective, should be considered as a potential means of reaching this goal,” he adds.

The study was supported by the Christopher Hess Research Fund and, in part, by UCSF and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sirota has reported serving as a scientific advisor at Aria Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hoertel has reported being listed as an inventor on a patent application related to methods of treating COVID-19, filed by Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, and receiving consulting fees and nonfinancial support from Lundbeck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mounting evidence suggests selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are associated with lower COVID-19 severity.

A large analysis of health records shows patients with COVID-19 taking an SSRI were significantly less likely to die of COVID-19 than a matched control group.

“We can’t tell if the drugs are causing these effects, but the statistical analysis is showing significant association. There’s power in the numbers,” Marina Sirota, PhD, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), said in a statement.

The study was published online Nov. 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Data-driven approach

, including 3,401 patients who were prescribed SSRIs.

When compared with matched patients with COVID-19 taking SSRIs, patients taking fluoxetine were 28% less likely to die (relative risk, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.54-0.97; adjusted P = .03) and those taking either fluoxetine or fluvoxamine were 26% less likely to die (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-0.99; adjusted P = .04) versus those not on these medications.

Patients with COVID-19 taking any kind of SSRI were 8% less likely to die than the matched controls (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-0.99; adjusted P = .03).

“We observed a statistically significant reduction in mortality of COVID-19 patients who were already taking SSRIs. This is a demonstration of a data-driven approach for identifying new uses for existing drugs,” Dr. Sirota said in an interview.

“Our study simply shows an association between SSRIs and COVID-19 outcomes and doesn’t investigate the mechanism of action of why the drugs might work. Additional clinical trials need to be carried out before these drugs can be used in patients going forward,” she cautioned.

“There is currently an open-label trial investigating fluoxetine to reduce intubation and death after COVID-19. To our knowledge, there are no phase 3 randomized controlled trials taking place or planned,” study investigator Tomiko Oskotsky, MD, with UCSF, told this news organization.

Urgent need

The current results “confirm and expand on prior findings from observational, preclinical, and clinical studies suggesting that certain SSRI antidepressants, including fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, could be beneficial against COVID-19,” Nicolas Hoertel, MD, PhD, MPH, with Paris University and Corentin-Celton Hospital, France, writes in a linked editorial.

Dr. Hoertel notes that the anti-inflammatory properties of SSRIs may underlie their potential action against COVID-19, and other potential mechanisms may include reduction in platelet aggregation, decreased mast cell degranulation, increased melatonin levels, interference with endolysosomal viral trafficking, and antioxidant activities.

“Because most of the world’s population is currently unvaccinated and the COVID-19 pandemic is still active, effective treatments of COVID-19 – especially those that are easy to use, show good tolerability, can be administered orally, and have widespread availability at low cost to allow their use in resource-poor countries – are urgently needed to reduce COVID-19-related mortality and morbidity,” Dr. Hoertel points out.

“In this context, short-term use of fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, if proven effective, should be considered as a potential means of reaching this goal,” he adds.

The study was supported by the Christopher Hess Research Fund and, in part, by UCSF and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sirota has reported serving as a scientific advisor at Aria Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hoertel has reported being listed as an inventor on a patent application related to methods of treating COVID-19, filed by Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, and receiving consulting fees and nonfinancial support from Lundbeck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mounting evidence suggests selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are associated with lower COVID-19 severity.

A large analysis of health records shows patients with COVID-19 taking an SSRI were significantly less likely to die of COVID-19 than a matched control group.

“We can’t tell if the drugs are causing these effects, but the statistical analysis is showing significant association. There’s power in the numbers,” Marina Sirota, PhD, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), said in a statement.

The study was published online Nov. 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Data-driven approach

, including 3,401 patients who were prescribed SSRIs.

When compared with matched patients with COVID-19 taking SSRIs, patients taking fluoxetine were 28% less likely to die (relative risk, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.54-0.97; adjusted P = .03) and those taking either fluoxetine or fluvoxamine were 26% less likely to die (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-0.99; adjusted P = .04) versus those not on these medications.

Patients with COVID-19 taking any kind of SSRI were 8% less likely to die than the matched controls (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-0.99; adjusted P = .03).

“We observed a statistically significant reduction in mortality of COVID-19 patients who were already taking SSRIs. This is a demonstration of a data-driven approach for identifying new uses for existing drugs,” Dr. Sirota said in an interview.

“Our study simply shows an association between SSRIs and COVID-19 outcomes and doesn’t investigate the mechanism of action of why the drugs might work. Additional clinical trials need to be carried out before these drugs can be used in patients going forward,” she cautioned.

“There is currently an open-label trial investigating fluoxetine to reduce intubation and death after COVID-19. To our knowledge, there are no phase 3 randomized controlled trials taking place or planned,” study investigator Tomiko Oskotsky, MD, with UCSF, told this news organization.

Urgent need

The current results “confirm and expand on prior findings from observational, preclinical, and clinical studies suggesting that certain SSRI antidepressants, including fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, could be beneficial against COVID-19,” Nicolas Hoertel, MD, PhD, MPH, with Paris University and Corentin-Celton Hospital, France, writes in a linked editorial.

Dr. Hoertel notes that the anti-inflammatory properties of SSRIs may underlie their potential action against COVID-19, and other potential mechanisms may include reduction in platelet aggregation, decreased mast cell degranulation, increased melatonin levels, interference with endolysosomal viral trafficking, and antioxidant activities.

“Because most of the world’s population is currently unvaccinated and the COVID-19 pandemic is still active, effective treatments of COVID-19 – especially those that are easy to use, show good tolerability, can be administered orally, and have widespread availability at low cost to allow their use in resource-poor countries – are urgently needed to reduce COVID-19-related mortality and morbidity,” Dr. Hoertel points out.

“In this context, short-term use of fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, if proven effective, should be considered as a potential means of reaching this goal,” he adds.

The study was supported by the Christopher Hess Research Fund and, in part, by UCSF and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sirota has reported serving as a scientific advisor at Aria Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hoertel has reported being listed as an inventor on a patent application related to methods of treating COVID-19, filed by Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, and receiving consulting fees and nonfinancial support from Lundbeck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospitalists helped plan COVID-19 field hospitals

‘It’s a great thing to be overprepared’

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic’s terrifying first wave in the spring of 2020, dozens of hospitals in high-incidence areas either planned or opened temporary, emergency field hospitals to cover anticipated demand for beds beyond the capacity of local permanent hospitals.

Chastened by images of overwhelmed health care systems in Northern Italy and other hard-hit areas,1 the planners used available modeling tools and estimates for projecting maximum potential need in worst-case scenarios. Some of these temporary hospitals never opened. Others opened in convention centers, parking garages, or parking lot tents, and ended up being used to a lesser degree than the worst-case scenarios.

But those who participated in the planning – including, in many cases, hospitalists – believe they created alternate care site manuals that could be quickly revived in the event of future COVID surges or other, similar crises. Better to plan for too much, they say, than not plan for enough.

Field hospitals or alternate care sites are defined in a recent journal article in Prehospital Disaster Medicine as “locations that can be converted to provide either inpatient and/or outpatient health services when existing facilities are compromised by a hazard impact or the volume of patients exceeds available capacity and/or capabilities.”2

The lead author of that report, Sue Anne Bell, PhD, FNP-BC, a disaster expert and assistant professor of nursing at the University of Michigan (UM), was one of five members of the leadership team for planning UM’s field hospital. They used an organizational unit structure based on the U.S. military’s staffing structure, with their work organized around six units of planning: personnel and labor, security, clinical operations, logistics and supply, planning and training, and communications. This team planned a 519-bed step-down care facility, the Michigan Medicine Field Hospital, for a 73,000-foot indoor track and performance facility at the university, three miles from UM’s main hospital. The aim was to provide safe care in a resource-limited environment.

“We were prepared, but the need never materialized as the peak of COVID cases started to subside,” Dr. Bell said. The team was ready to open within days using a “T-Minus” framework of days remaining on an official countdown clock. But when the need and deadlines kept getting pushed back, that gave them more time to develop clearer procedures.

Two Michigan Medicine hospitalists, Christopher Smith, MD, and David Paje, MD, MPH, both professors at UM’s medical school, were intimately involved in the process. “I was the medical director for the respiratory care unit that was opened for COVID patients, so I was pulled in to assist in the field hospital planning,” said Dr. Smith.

Dr. Paje was director of the short-stay unit and had been a medical officer in the U.S. Army, with training in how to set up military field hospitals. He credits that background as helpful for UM’s COVID field hospital planning, along with his experience in hospital medicine operations.

“We expected that these patients would need the expertise of hospitalists, who had quickly become familiar with the peculiarities of the new disease. That played a role in the decisions we made. Hospitalists were at the front lines of COVID care and had unique clinical insights about managing those with severe disease,” Dr. Paje added.

“When we started, the projections were dire. You don’t want to believe something like that is going to happen. When COVID started to cool off, it was more of a relief to us than anything else,” Dr. Smith said. “Still, it was a very worthwhile exercise. At the end of the day, we put together a comprehensive guide, which is ready for the next crisis.”

Baltimore builds a convention center hospital

A COVID-19 field hospital was planned and executed at an exhibit hall in the Baltimore Convention Center, starting in March 2020 under the leadership of Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who eventually handed over responsibilities as chief medical officer when he assumed the position of CEO for the Society of Hospital Medicine in July of that year.

Hopkins collaborated with the University of Maryland health system and state leaders, including the Secretary of Health, to open a 252-bed temporary facility, which at its peak carried a census of 48 patients, with no on-site mortality or cardiac arrests, before it was closed in June 2021 – ready to reopen if necessary. It also served as Baltimore’s major site for polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 testing, vaccinations, and monoclonal antibody infusions, along with medical research.

“My belief at the time we started was that my entire 20-year career as a hospitalist had prepared me for the challenge of opening a COVID field hospital,” Dr. Howell said. “I had learned how to build clinical programs. The difference was that instead of months and years to build a program, we only had a few weeks.”

His first request was to bring on an associate medical director for the field hospital, Melinda E. Kantsiper, MD, a hospitalist and director of clinical operations in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview. She became the field hospital’s CMO when Dr. Howell moved to SHM. “As hospitalists, we are trained to care for the patient in front of us while at the same time creating systems that can adjust to rapidly changing circumstances,” Dr. Kantsiper said. “We did what was asked and set up a field hospital that cared for a total of 1,500 COVID patients.”

Hospitalists have the tools that are needed for this work, and shouldn’t be reluctant to contribute to field hospital planning, she said. “This was a real eye-opener for me. Eric explained to me that hospitalists really practice acute care medicine, which doesn’t have to be within the four walls of a hospital.”

The Baltimore field hospital has been a fantastic experience, Dr. Kantsiper added. “But it’s not a building designed for health care delivery.” For the right group of providers, the experience of working in a temporary facility such as this can be positive and exhilarating. “But we need to make sure we take care of our staff. It takes a toll. How we keep them safe – physically and emotionally – has to be top of mind,” she said.

The leaders at Hopkins Medicine and their collaborators truly engaged with the field hospital’s mission, Dr. Howell added.

“They gave us a lot of autonomy and helped us break down barriers. They gave us the political capital to say proper PPE was absolutely essential. As hard and devastating as the pandemic has been, one take-away is that we showed that we can be more flexible and elastic in response to actual needs than we used to think.”

Range of challenges

Among the questions that need to be answered by a field hospital’s planners, the first is ‘where to put it?’ The answer is, hopefully, someplace not too far away, large enough, with ready access to supplies and intake. The next question is ‘who is the patient?’ Clinicians must determine who goes to the field hospital versus who stays at the standing hospital. How sick should these patients be? And when do they need to go back to the permanent hospital? Can staff be trained to recognize when patients in the field hospital are starting to decompensate? The EPIC Deterioration Index3 is a proprietary prediction model that was used by more than a hundred hospitals during the pandemic.

The hospitalist team may develop specific inclusion and exclusion criteria – for example, don’t admit patients who are receiving oxygen therapy above a certain threshold or who are hemodynamically unstable. These criteria should reflect the capacity of the field hospital and the needs of the permanent hospital. At Michigan, as at other field hospital sites, the goal was to offer a step-down or postacute setting for patients with COVID-19 who were too sick to return home but didn’t need acute or ICU-level care, thereby freeing up beds at the permanent hospital for patients who were sicker.

Other questions: What is the process for admissions and discharges? How will patients be transported? What kind of staffing is needed, and what levels of care will be provided? What about rehabilitation services, or palliative care? What about patients with substance abuse or psychiatric comorbidities?

“Are we going to do paper charting? How will that work out for long-term documentation and billing?” Dr. Bell said. A clear reporting structure and communication pathways are essential. Among the other operational processes to address, outlined in Dr. Bell’s article, are orientation and training, PPE donning and doffing procedures, the code or rapid response team, patient and staff food and nutrition, infection control protocols, pharmacy services, access to radiology, rounding procedures, staff support, and the morgue.

One other issue that shouldn’t be overlooked is health equity in the field hospital. “Providing safe and equitable care should be the focus. Thinking who goes to the field hospital should be done within a health equity framework,” Dr. Bell said.4 She also wonders if field hospital planners are sharing their experience with colleagues across the country and developing more collaborative relationships with other hospitals in their communities.

“Field hospitals can be different things,” Dr. Bell said. “The important take-home is it doesn’t have to be in a tent or a parking garage, which can be suboptimal.” In many cases, it may be better to focus on finding unused space within the hospital – whether a lobby, staff lounge, or unoccupied unit – closer to personnel, supplies, pharmacy, and the like. “I think the pandemic showed us how unprepared we were as a health care system, and how much more we need to do in preparation for future crises.”

Limits to the temporary hospital

In New York City, which had the country’s worst COVID-19 outbreak during the first surge in the spring of 2020, a 1,000-bed field hospital was opened at the Jacob Javits Center in March 2020 and closed that June. “I was in the field hospital early, in March and April, when our hospitals were temporarily overrun,” said hospitalist Mona Krouss, MD, FACP, CPPS, NYC Health + Hospitals’ director of patient safety. “My role was to figure out how to get patients on our medical floors into these field hospitals, with responsibility for helping to revise admission criteria,” she said.

“No one knew how horrible it would become. This was so unanticipated, so difficult to operationalize. What they were able to create was amazing, but there were just too many barriers to have it work smoothly,” Dr. Krouss said.

“The military stepped in, and they helped us so much. We wouldn’t have been able to survive without their help.” But there is only so much a field hospital can do to provide acute medical care. Later, military medical teams shifted to roles in temporary units inside the permanent hospitals. “They came to the hospital wanting to be deployed,” she said.

“We could only send patients [to the field hospital] who were fairly stable, and choosing the right ones was difficult.” Dr. Krouss said. In the end, not a lot of COVID-19 patients from NYC Health + Hospitals ended up going to the Javits Center, in part because the paperwork and logistics of getting someone in was a barrier, Dr. Krouss said. A process was established for referring doctors to call a phone number and speak with a New York City Department of Health employee to go through the criteria for admission to the field hospital.

“That could take up to 30 minutes before getting approval. Then you had to go through the same process all over again for sign-out to another physician, and then register the patient with a special bar code. Then you had to arrange ambulance transfer. Doctors didn’t want to go through all of that – everybody was too busy,” she explained. Hospitalists have since worked on streamlining the criteria. “Now we have a good process for the future. We made it more seamless,” she noted.

Susan Lee, DO, MBA, hospitalist and chief medical officer for Renown Regional Medical Center in Reno, Nev., helped to plan an alternate care site in anticipation of up to a thousand COVID patients in her community – far beyond the scope of the existing hospitals. Hospitalists were involved the entire time in planning, design of the unit, design of staffing models, care protocols, and the like, working through an evidence-based medical committee and a COVID-19 provider task force for the Renown Health System.

“Because of a history of fires and earthquakes in this region, we had an emergency planning infrastructure in place. We put the field hospital on the first and second floors of a parking garage, with built-in negative pressure capacity. We also built space for staff break rooms and desk space. It took 10 days to build the hospital, thanks to some very talented people in management and facility design,” Dr. Lee said.

Then, the hospital was locked up and sat empty for 7 months, until the surge in December 2020, when Reno was hit by a bigger wave – this time exceeding the hospitals’ capacity. Through mid-January of 2021, clinicians cared for approximately 240 COVID-19 patients, up to 47 at a time, in the field hospital. A third wave in the autumn of 2021 plateaued at a level lower than the previous fall, so the field hospital is not currently needed.

Replicating hospital work flows

“We ensured that everybody who needed to be within the walls of the permanent hospitals was able to stay there,” said Dr. Lee’s colleague, hospitalist Adnan (Eddy) Akbar, MD. “The postacute system we ordinarily rely on was no longer accepting patients. Other hospitals in the area were able to manage within their capacity because Renown’s field hospital could admit excess patients. We tried to replicate in the field hospital, as much as possible, the work flows and systems of our main hospital.”

When the field hospital finally opened, Dr. Akbar said, “we had a good feeling. We were ready. If something more catastrophic had come down, we were ready to care for more patients. In the field hospital you have to keep monitoring your work flow – almost on a daily basis. But we felt privileged to be working for a system where you knew you can go and care for everyone who needed care.”

One upside of the field hospital experience for participating clinicians, Dr. Lee added, is the opportunity to practice creatively. “The downside is it’s extremely expensive, and has consequences for the mental health of staff. Like so many of these things, it wore on people over time – such as all the time spent donning and doffing protective equipment. And recently the patients have become a lot less gracious.”

Amy Baughman, MD, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was co-medical director of the postacute care section of a 1,000-bed field hospital, Boston Hope Medical Center, opened in April 2020 at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. The other half of the facility was dedicated to undomiciled COVID-19 patients who had no place else to go. Peak census was around 100 patients, housed on four units, each with a clinical team led by a physician.

Dr. Baughman’s field hospital experience has taught her the importance of “staying within your domain of expertise. Physicians are attracted to difficult problems and want to do everything themselves. Next time I won’t be the one installing hand sanitizer dispensers.” A big part of running a field hospital is logistics, she said, and physicians are trained clinicians, not necessarily logistics engineers.

“So it’s important to partner with logistics experts. A huge part of our success in building a facility in 9 days of almost continuous construction was the involvement of the National Guard,” she said. An incident command system was led by an experienced military general incident commander, with two clinical codirectors. The army also sent in full teams of health professionals.

The facility admitted a lot fewer patients than the worst-case projections before it closed in June 2020. “But at the end of the day, we provided a lot of excellent care,” Dr. Baughman said. “This was about preparing for a disaster. It was all hands on deck, and the hands were health professionals. We spent a lot of money for the patients we took care of, but we had no choice, based on what we believed could happen. At that time, so many nursing facilities and homeless shelters were closed to us. It was impossible to predict what utilization would be.”

Subsequent experience has taught that a lot of even seriously ill COVID-19 patients can be managed safely at home, for example, using accelerated home oxygen monitoring with telelinked pulse oximeters. But in the beginning, Dr. Baughman said, “it was a new situation for us. We had seen what happened in Europe and China. It’s a great thing to be overprepared.”

References

1. Horowitz J. Italy’s health care system groans under coronavirus – a warning to the world. New York Times. 2020 Mar 12.

2. Bell SA et al. T-Minus 10 days: The role of an academic medical institution in field hospital planning. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021 Feb 18:1-6. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X21000224.

3. Singh K et al. Evaluating a widely implemented proprietary deterioration index model among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021 Jul;18(7):1129-37. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-698OC.

4. Bell SA et al. Alternate care sites during COVID-19 pandemic: Policy implications for pandemic surge planning. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021 Jul 23;1-3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.241.

‘It’s a great thing to be overprepared’

‘It’s a great thing to be overprepared’

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic’s terrifying first wave in the spring of 2020, dozens of hospitals in high-incidence areas either planned or opened temporary, emergency field hospitals to cover anticipated demand for beds beyond the capacity of local permanent hospitals.

Chastened by images of overwhelmed health care systems in Northern Italy and other hard-hit areas,1 the planners used available modeling tools and estimates for projecting maximum potential need in worst-case scenarios. Some of these temporary hospitals never opened. Others opened in convention centers, parking garages, or parking lot tents, and ended up being used to a lesser degree than the worst-case scenarios.

But those who participated in the planning – including, in many cases, hospitalists – believe they created alternate care site manuals that could be quickly revived in the event of future COVID surges or other, similar crises. Better to plan for too much, they say, than not plan for enough.

Field hospitals or alternate care sites are defined in a recent journal article in Prehospital Disaster Medicine as “locations that can be converted to provide either inpatient and/or outpatient health services when existing facilities are compromised by a hazard impact or the volume of patients exceeds available capacity and/or capabilities.”2

The lead author of that report, Sue Anne Bell, PhD, FNP-BC, a disaster expert and assistant professor of nursing at the University of Michigan (UM), was one of five members of the leadership team for planning UM’s field hospital. They used an organizational unit structure based on the U.S. military’s staffing structure, with their work organized around six units of planning: personnel and labor, security, clinical operations, logistics and supply, planning and training, and communications. This team planned a 519-bed step-down care facility, the Michigan Medicine Field Hospital, for a 73,000-foot indoor track and performance facility at the university, three miles from UM’s main hospital. The aim was to provide safe care in a resource-limited environment.

“We were prepared, but the need never materialized as the peak of COVID cases started to subside,” Dr. Bell said. The team was ready to open within days using a “T-Minus” framework of days remaining on an official countdown clock. But when the need and deadlines kept getting pushed back, that gave them more time to develop clearer procedures.

Two Michigan Medicine hospitalists, Christopher Smith, MD, and David Paje, MD, MPH, both professors at UM’s medical school, were intimately involved in the process. “I was the medical director for the respiratory care unit that was opened for COVID patients, so I was pulled in to assist in the field hospital planning,” said Dr. Smith.

Dr. Paje was director of the short-stay unit and had been a medical officer in the U.S. Army, with training in how to set up military field hospitals. He credits that background as helpful for UM’s COVID field hospital planning, along with his experience in hospital medicine operations.

“We expected that these patients would need the expertise of hospitalists, who had quickly become familiar with the peculiarities of the new disease. That played a role in the decisions we made. Hospitalists were at the front lines of COVID care and had unique clinical insights about managing those with severe disease,” Dr. Paje added.

“When we started, the projections were dire. You don’t want to believe something like that is going to happen. When COVID started to cool off, it was more of a relief to us than anything else,” Dr. Smith said. “Still, it was a very worthwhile exercise. At the end of the day, we put together a comprehensive guide, which is ready for the next crisis.”

Baltimore builds a convention center hospital

A COVID-19 field hospital was planned and executed at an exhibit hall in the Baltimore Convention Center, starting in March 2020 under the leadership of Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who eventually handed over responsibilities as chief medical officer when he assumed the position of CEO for the Society of Hospital Medicine in July of that year.

Hopkins collaborated with the University of Maryland health system and state leaders, including the Secretary of Health, to open a 252-bed temporary facility, which at its peak carried a census of 48 patients, with no on-site mortality or cardiac arrests, before it was closed in June 2021 – ready to reopen if necessary. It also served as Baltimore’s major site for polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 testing, vaccinations, and monoclonal antibody infusions, along with medical research.

“My belief at the time we started was that my entire 20-year career as a hospitalist had prepared me for the challenge of opening a COVID field hospital,” Dr. Howell said. “I had learned how to build clinical programs. The difference was that instead of months and years to build a program, we only had a few weeks.”

His first request was to bring on an associate medical director for the field hospital, Melinda E. Kantsiper, MD, a hospitalist and director of clinical operations in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview. She became the field hospital’s CMO when Dr. Howell moved to SHM. “As hospitalists, we are trained to care for the patient in front of us while at the same time creating systems that can adjust to rapidly changing circumstances,” Dr. Kantsiper said. “We did what was asked and set up a field hospital that cared for a total of 1,500 COVID patients.”

Hospitalists have the tools that are needed for this work, and shouldn’t be reluctant to contribute to field hospital planning, she said. “This was a real eye-opener for me. Eric explained to me that hospitalists really practice acute care medicine, which doesn’t have to be within the four walls of a hospital.”

The Baltimore field hospital has been a fantastic experience, Dr. Kantsiper added. “But it’s not a building designed for health care delivery.” For the right group of providers, the experience of working in a temporary facility such as this can be positive and exhilarating. “But we need to make sure we take care of our staff. It takes a toll. How we keep them safe – physically and emotionally – has to be top of mind,” she said.

The leaders at Hopkins Medicine and their collaborators truly engaged with the field hospital’s mission, Dr. Howell added.

“They gave us a lot of autonomy and helped us break down barriers. They gave us the political capital to say proper PPE was absolutely essential. As hard and devastating as the pandemic has been, one take-away is that we showed that we can be more flexible and elastic in response to actual needs than we used to think.”

Range of challenges

Among the questions that need to be answered by a field hospital’s planners, the first is ‘where to put it?’ The answer is, hopefully, someplace not too far away, large enough, with ready access to supplies and intake. The next question is ‘who is the patient?’ Clinicians must determine who goes to the field hospital versus who stays at the standing hospital. How sick should these patients be? And when do they need to go back to the permanent hospital? Can staff be trained to recognize when patients in the field hospital are starting to decompensate? The EPIC Deterioration Index3 is a proprietary prediction model that was used by more than a hundred hospitals during the pandemic.

The hospitalist team may develop specific inclusion and exclusion criteria – for example, don’t admit patients who are receiving oxygen therapy above a certain threshold or who are hemodynamically unstable. These criteria should reflect the capacity of the field hospital and the needs of the permanent hospital. At Michigan, as at other field hospital sites, the goal was to offer a step-down or postacute setting for patients with COVID-19 who were too sick to return home but didn’t need acute or ICU-level care, thereby freeing up beds at the permanent hospital for patients who were sicker.

Other questions: What is the process for admissions and discharges? How will patients be transported? What kind of staffing is needed, and what levels of care will be provided? What about rehabilitation services, or palliative care? What about patients with substance abuse or psychiatric comorbidities?

“Are we going to do paper charting? How will that work out for long-term documentation and billing?” Dr. Bell said. A clear reporting structure and communication pathways are essential. Among the other operational processes to address, outlined in Dr. Bell’s article, are orientation and training, PPE donning and doffing procedures, the code or rapid response team, patient and staff food and nutrition, infection control protocols, pharmacy services, access to radiology, rounding procedures, staff support, and the morgue.

One other issue that shouldn’t be overlooked is health equity in the field hospital. “Providing safe and equitable care should be the focus. Thinking who goes to the field hospital should be done within a health equity framework,” Dr. Bell said.4 She also wonders if field hospital planners are sharing their experience with colleagues across the country and developing more collaborative relationships with other hospitals in their communities.

“Field hospitals can be different things,” Dr. Bell said. “The important take-home is it doesn’t have to be in a tent or a parking garage, which can be suboptimal.” In many cases, it may be better to focus on finding unused space within the hospital – whether a lobby, staff lounge, or unoccupied unit – closer to personnel, supplies, pharmacy, and the like. “I think the pandemic showed us how unprepared we were as a health care system, and how much more we need to do in preparation for future crises.”

Limits to the temporary hospital

In New York City, which had the country’s worst COVID-19 outbreak during the first surge in the spring of 2020, a 1,000-bed field hospital was opened at the Jacob Javits Center in March 2020 and closed that June. “I was in the field hospital early, in March and April, when our hospitals were temporarily overrun,” said hospitalist Mona Krouss, MD, FACP, CPPS, NYC Health + Hospitals’ director of patient safety. “My role was to figure out how to get patients on our medical floors into these field hospitals, with responsibility for helping to revise admission criteria,” she said.

“No one knew how horrible it would become. This was so unanticipated, so difficult to operationalize. What they were able to create was amazing, but there were just too many barriers to have it work smoothly,” Dr. Krouss said.

“The military stepped in, and they helped us so much. We wouldn’t have been able to survive without their help.” But there is only so much a field hospital can do to provide acute medical care. Later, military medical teams shifted to roles in temporary units inside the permanent hospitals. “They came to the hospital wanting to be deployed,” she said.

“We could only send patients [to the field hospital] who were fairly stable, and choosing the right ones was difficult.” Dr. Krouss said. In the end, not a lot of COVID-19 patients from NYC Health + Hospitals ended up going to the Javits Center, in part because the paperwork and logistics of getting someone in was a barrier, Dr. Krouss said. A process was established for referring doctors to call a phone number and speak with a New York City Department of Health employee to go through the criteria for admission to the field hospital.

“That could take up to 30 minutes before getting approval. Then you had to go through the same process all over again for sign-out to another physician, and then register the patient with a special bar code. Then you had to arrange ambulance transfer. Doctors didn’t want to go through all of that – everybody was too busy,” she explained. Hospitalists have since worked on streamlining the criteria. “Now we have a good process for the future. We made it more seamless,” she noted.

Susan Lee, DO, MBA, hospitalist and chief medical officer for Renown Regional Medical Center in Reno, Nev., helped to plan an alternate care site in anticipation of up to a thousand COVID patients in her community – far beyond the scope of the existing hospitals. Hospitalists were involved the entire time in planning, design of the unit, design of staffing models, care protocols, and the like, working through an evidence-based medical committee and a COVID-19 provider task force for the Renown Health System.

“Because of a history of fires and earthquakes in this region, we had an emergency planning infrastructure in place. We put the field hospital on the first and second floors of a parking garage, with built-in negative pressure capacity. We also built space for staff break rooms and desk space. It took 10 days to build the hospital, thanks to some very talented people in management and facility design,” Dr. Lee said.

Then, the hospital was locked up and sat empty for 7 months, until the surge in December 2020, when Reno was hit by a bigger wave – this time exceeding the hospitals’ capacity. Through mid-January of 2021, clinicians cared for approximately 240 COVID-19 patients, up to 47 at a time, in the field hospital. A third wave in the autumn of 2021 plateaued at a level lower than the previous fall, so the field hospital is not currently needed.

Replicating hospital work flows

“We ensured that everybody who needed to be within the walls of the permanent hospitals was able to stay there,” said Dr. Lee’s colleague, hospitalist Adnan (Eddy) Akbar, MD. “The postacute system we ordinarily rely on was no longer accepting patients. Other hospitals in the area were able to manage within their capacity because Renown’s field hospital could admit excess patients. We tried to replicate in the field hospital, as much as possible, the work flows and systems of our main hospital.”

When the field hospital finally opened, Dr. Akbar said, “we had a good feeling. We were ready. If something more catastrophic had come down, we were ready to care for more patients. In the field hospital you have to keep monitoring your work flow – almost on a daily basis. But we felt privileged to be working for a system where you knew you can go and care for everyone who needed care.”

One upside of the field hospital experience for participating clinicians, Dr. Lee added, is the opportunity to practice creatively. “The downside is it’s extremely expensive, and has consequences for the mental health of staff. Like so many of these things, it wore on people over time – such as all the time spent donning and doffing protective equipment. And recently the patients have become a lot less gracious.”

Amy Baughman, MD, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was co-medical director of the postacute care section of a 1,000-bed field hospital, Boston Hope Medical Center, opened in April 2020 at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. The other half of the facility was dedicated to undomiciled COVID-19 patients who had no place else to go. Peak census was around 100 patients, housed on four units, each with a clinical team led by a physician.

Dr. Baughman’s field hospital experience has taught her the importance of “staying within your domain of expertise. Physicians are attracted to difficult problems and want to do everything themselves. Next time I won’t be the one installing hand sanitizer dispensers.” A big part of running a field hospital is logistics, she said, and physicians are trained clinicians, not necessarily logistics engineers.

“So it’s important to partner with logistics experts. A huge part of our success in building a facility in 9 days of almost continuous construction was the involvement of the National Guard,” she said. An incident command system was led by an experienced military general incident commander, with two clinical codirectors. The army also sent in full teams of health professionals.

The facility admitted a lot fewer patients than the worst-case projections before it closed in June 2020. “But at the end of the day, we provided a lot of excellent care,” Dr. Baughman said. “This was about preparing for a disaster. It was all hands on deck, and the hands were health professionals. We spent a lot of money for the patients we took care of, but we had no choice, based on what we believed could happen. At that time, so many nursing facilities and homeless shelters were closed to us. It was impossible to predict what utilization would be.”

Subsequent experience has taught that a lot of even seriously ill COVID-19 patients can be managed safely at home, for example, using accelerated home oxygen monitoring with telelinked pulse oximeters. But in the beginning, Dr. Baughman said, “it was a new situation for us. We had seen what happened in Europe and China. It’s a great thing to be overprepared.”

References

1. Horowitz J. Italy’s health care system groans under coronavirus – a warning to the world. New York Times. 2020 Mar 12.

2. Bell SA et al. T-Minus 10 days: The role of an academic medical institution in field hospital planning. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021 Feb 18:1-6. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X21000224.

3. Singh K et al. Evaluating a widely implemented proprietary deterioration index model among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021 Jul;18(7):1129-37. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-698OC.

4. Bell SA et al. Alternate care sites during COVID-19 pandemic: Policy implications for pandemic surge planning. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021 Jul 23;1-3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.241.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic’s terrifying first wave in the spring of 2020, dozens of hospitals in high-incidence areas either planned or opened temporary, emergency field hospitals to cover anticipated demand for beds beyond the capacity of local permanent hospitals.

Chastened by images of overwhelmed health care systems in Northern Italy and other hard-hit areas,1 the planners used available modeling tools and estimates for projecting maximum potential need in worst-case scenarios. Some of these temporary hospitals never opened. Others opened in convention centers, parking garages, or parking lot tents, and ended up being used to a lesser degree than the worst-case scenarios.

But those who participated in the planning – including, in many cases, hospitalists – believe they created alternate care site manuals that could be quickly revived in the event of future COVID surges or other, similar crises. Better to plan for too much, they say, than not plan for enough.

Field hospitals or alternate care sites are defined in a recent journal article in Prehospital Disaster Medicine as “locations that can be converted to provide either inpatient and/or outpatient health services when existing facilities are compromised by a hazard impact or the volume of patients exceeds available capacity and/or capabilities.”2

The lead author of that report, Sue Anne Bell, PhD, FNP-BC, a disaster expert and assistant professor of nursing at the University of Michigan (UM), was one of five members of the leadership team for planning UM’s field hospital. They used an organizational unit structure based on the U.S. military’s staffing structure, with their work organized around six units of planning: personnel and labor, security, clinical operations, logistics and supply, planning and training, and communications. This team planned a 519-bed step-down care facility, the Michigan Medicine Field Hospital, for a 73,000-foot indoor track and performance facility at the university, three miles from UM’s main hospital. The aim was to provide safe care in a resource-limited environment.

“We were prepared, but the need never materialized as the peak of COVID cases started to subside,” Dr. Bell said. The team was ready to open within days using a “T-Minus” framework of days remaining on an official countdown clock. But when the need and deadlines kept getting pushed back, that gave them more time to develop clearer procedures.

Two Michigan Medicine hospitalists, Christopher Smith, MD, and David Paje, MD, MPH, both professors at UM’s medical school, were intimately involved in the process. “I was the medical director for the respiratory care unit that was opened for COVID patients, so I was pulled in to assist in the field hospital planning,” said Dr. Smith.

Dr. Paje was director of the short-stay unit and had been a medical officer in the U.S. Army, with training in how to set up military field hospitals. He credits that background as helpful for UM’s COVID field hospital planning, along with his experience in hospital medicine operations.

“We expected that these patients would need the expertise of hospitalists, who had quickly become familiar with the peculiarities of the new disease. That played a role in the decisions we made. Hospitalists were at the front lines of COVID care and had unique clinical insights about managing those with severe disease,” Dr. Paje added.

“When we started, the projections were dire. You don’t want to believe something like that is going to happen. When COVID started to cool off, it was more of a relief to us than anything else,” Dr. Smith said. “Still, it was a very worthwhile exercise. At the end of the day, we put together a comprehensive guide, which is ready for the next crisis.”

Baltimore builds a convention center hospital

A COVID-19 field hospital was planned and executed at an exhibit hall in the Baltimore Convention Center, starting in March 2020 under the leadership of Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who eventually handed over responsibilities as chief medical officer when he assumed the position of CEO for the Society of Hospital Medicine in July of that year.

Hopkins collaborated with the University of Maryland health system and state leaders, including the Secretary of Health, to open a 252-bed temporary facility, which at its peak carried a census of 48 patients, with no on-site mortality or cardiac arrests, before it was closed in June 2021 – ready to reopen if necessary. It also served as Baltimore’s major site for polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 testing, vaccinations, and monoclonal antibody infusions, along with medical research.

“My belief at the time we started was that my entire 20-year career as a hospitalist had prepared me for the challenge of opening a COVID field hospital,” Dr. Howell said. “I had learned how to build clinical programs. The difference was that instead of months and years to build a program, we only had a few weeks.”

His first request was to bring on an associate medical director for the field hospital, Melinda E. Kantsiper, MD, a hospitalist and director of clinical operations in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview. She became the field hospital’s CMO when Dr. Howell moved to SHM. “As hospitalists, we are trained to care for the patient in front of us while at the same time creating systems that can adjust to rapidly changing circumstances,” Dr. Kantsiper said. “We did what was asked and set up a field hospital that cared for a total of 1,500 COVID patients.”

Hospitalists have the tools that are needed for this work, and shouldn’t be reluctant to contribute to field hospital planning, she said. “This was a real eye-opener for me. Eric explained to me that hospitalists really practice acute care medicine, which doesn’t have to be within the four walls of a hospital.”

The Baltimore field hospital has been a fantastic experience, Dr. Kantsiper added. “But it’s not a building designed for health care delivery.” For the right group of providers, the experience of working in a temporary facility such as this can be positive and exhilarating. “But we need to make sure we take care of our staff. It takes a toll. How we keep them safe – physically and emotionally – has to be top of mind,” she said.

The leaders at Hopkins Medicine and their collaborators truly engaged with the field hospital’s mission, Dr. Howell added.

“They gave us a lot of autonomy and helped us break down barriers. They gave us the political capital to say proper PPE was absolutely essential. As hard and devastating as the pandemic has been, one take-away is that we showed that we can be more flexible and elastic in response to actual needs than we used to think.”

Range of challenges

Among the questions that need to be answered by a field hospital’s planners, the first is ‘where to put it?’ The answer is, hopefully, someplace not too far away, large enough, with ready access to supplies and intake. The next question is ‘who is the patient?’ Clinicians must determine who goes to the field hospital versus who stays at the standing hospital. How sick should these patients be? And when do they need to go back to the permanent hospital? Can staff be trained to recognize when patients in the field hospital are starting to decompensate? The EPIC Deterioration Index3 is a proprietary prediction model that was used by more than a hundred hospitals during the pandemic.

The hospitalist team may develop specific inclusion and exclusion criteria – for example, don’t admit patients who are receiving oxygen therapy above a certain threshold or who are hemodynamically unstable. These criteria should reflect the capacity of the field hospital and the needs of the permanent hospital. At Michigan, as at other field hospital sites, the goal was to offer a step-down or postacute setting for patients with COVID-19 who were too sick to return home but didn’t need acute or ICU-level care, thereby freeing up beds at the permanent hospital for patients who were sicker.

Other questions: What is the process for admissions and discharges? How will patients be transported? What kind of staffing is needed, and what levels of care will be provided? What about rehabilitation services, or palliative care? What about patients with substance abuse or psychiatric comorbidities?

“Are we going to do paper charting? How will that work out for long-term documentation and billing?” Dr. Bell said. A clear reporting structure and communication pathways are essential. Among the other operational processes to address, outlined in Dr. Bell’s article, are orientation and training, PPE donning and doffing procedures, the code or rapid response team, patient and staff food and nutrition, infection control protocols, pharmacy services, access to radiology, rounding procedures, staff support, and the morgue.

One other issue that shouldn’t be overlooked is health equity in the field hospital. “Providing safe and equitable care should be the focus. Thinking who goes to the field hospital should be done within a health equity framework,” Dr. Bell said.4 She also wonders if field hospital planners are sharing their experience with colleagues across the country and developing more collaborative relationships with other hospitals in their communities.

“Field hospitals can be different things,” Dr. Bell said. “The important take-home is it doesn’t have to be in a tent or a parking garage, which can be suboptimal.” In many cases, it may be better to focus on finding unused space within the hospital – whether a lobby, staff lounge, or unoccupied unit – closer to personnel, supplies, pharmacy, and the like. “I think the pandemic showed us how unprepared we were as a health care system, and how much more we need to do in preparation for future crises.”

Limits to the temporary hospital

In New York City, which had the country’s worst COVID-19 outbreak during the first surge in the spring of 2020, a 1,000-bed field hospital was opened at the Jacob Javits Center in March 2020 and closed that June. “I was in the field hospital early, in March and April, when our hospitals were temporarily overrun,” said hospitalist Mona Krouss, MD, FACP, CPPS, NYC Health + Hospitals’ director of patient safety. “My role was to figure out how to get patients on our medical floors into these field hospitals, with responsibility for helping to revise admission criteria,” she said.

“No one knew how horrible it would become. This was so unanticipated, so difficult to operationalize. What they were able to create was amazing, but there were just too many barriers to have it work smoothly,” Dr. Krouss said.

“The military stepped in, and they helped us so much. We wouldn’t have been able to survive without their help.” But there is only so much a field hospital can do to provide acute medical care. Later, military medical teams shifted to roles in temporary units inside the permanent hospitals. “They came to the hospital wanting to be deployed,” she said.

“We could only send patients [to the field hospital] who were fairly stable, and choosing the right ones was difficult.” Dr. Krouss said. In the end, not a lot of COVID-19 patients from NYC Health + Hospitals ended up going to the Javits Center, in part because the paperwork and logistics of getting someone in was a barrier, Dr. Krouss said. A process was established for referring doctors to call a phone number and speak with a New York City Department of Health employee to go through the criteria for admission to the field hospital.

“That could take up to 30 minutes before getting approval. Then you had to go through the same process all over again for sign-out to another physician, and then register the patient with a special bar code. Then you had to arrange ambulance transfer. Doctors didn’t want to go through all of that – everybody was too busy,” she explained. Hospitalists have since worked on streamlining the criteria. “Now we have a good process for the future. We made it more seamless,” she noted.

Susan Lee, DO, MBA, hospitalist and chief medical officer for Renown Regional Medical Center in Reno, Nev., helped to plan an alternate care site in anticipation of up to a thousand COVID patients in her community – far beyond the scope of the existing hospitals. Hospitalists were involved the entire time in planning, design of the unit, design of staffing models, care protocols, and the like, working through an evidence-based medical committee and a COVID-19 provider task force for the Renown Health System.

“Because of a history of fires and earthquakes in this region, we had an emergency planning infrastructure in place. We put the field hospital on the first and second floors of a parking garage, with built-in negative pressure capacity. We also built space for staff break rooms and desk space. It took 10 days to build the hospital, thanks to some very talented people in management and facility design,” Dr. Lee said.

Then, the hospital was locked up and sat empty for 7 months, until the surge in December 2020, when Reno was hit by a bigger wave – this time exceeding the hospitals’ capacity. Through mid-January of 2021, clinicians cared for approximately 240 COVID-19 patients, up to 47 at a time, in the field hospital. A third wave in the autumn of 2021 plateaued at a level lower than the previous fall, so the field hospital is not currently needed.

Replicating hospital work flows

“We ensured that everybody who needed to be within the walls of the permanent hospitals was able to stay there,” said Dr. Lee’s colleague, hospitalist Adnan (Eddy) Akbar, MD. “The postacute system we ordinarily rely on was no longer accepting patients. Other hospitals in the area were able to manage within their capacity because Renown’s field hospital could admit excess patients. We tried to replicate in the field hospital, as much as possible, the work flows and systems of our main hospital.”

When the field hospital finally opened, Dr. Akbar said, “we had a good feeling. We were ready. If something more catastrophic had come down, we were ready to care for more patients. In the field hospital you have to keep monitoring your work flow – almost on a daily basis. But we felt privileged to be working for a system where you knew you can go and care for everyone who needed care.”

One upside of the field hospital experience for participating clinicians, Dr. Lee added, is the opportunity to practice creatively. “The downside is it’s extremely expensive, and has consequences for the mental health of staff. Like so many of these things, it wore on people over time – such as all the time spent donning and doffing protective equipment. And recently the patients have become a lot less gracious.”

Amy Baughman, MD, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was co-medical director of the postacute care section of a 1,000-bed field hospital, Boston Hope Medical Center, opened in April 2020 at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. The other half of the facility was dedicated to undomiciled COVID-19 patients who had no place else to go. Peak census was around 100 patients, housed on four units, each with a clinical team led by a physician.

Dr. Baughman’s field hospital experience has taught her the importance of “staying within your domain of expertise. Physicians are attracted to difficult problems and want to do everything themselves. Next time I won’t be the one installing hand sanitizer dispensers.” A big part of running a field hospital is logistics, she said, and physicians are trained clinicians, not necessarily logistics engineers.

“So it’s important to partner with logistics experts. A huge part of our success in building a facility in 9 days of almost continuous construction was the involvement of the National Guard,” she said. An incident command system was led by an experienced military general incident commander, with two clinical codirectors. The army also sent in full teams of health professionals.

The facility admitted a lot fewer patients than the worst-case projections before it closed in June 2020. “But at the end of the day, we provided a lot of excellent care,” Dr. Baughman said. “This was about preparing for a disaster. It was all hands on deck, and the hands were health professionals. We spent a lot of money for the patients we took care of, but we had no choice, based on what we believed could happen. At that time, so many nursing facilities and homeless shelters were closed to us. It was impossible to predict what utilization would be.”

Subsequent experience has taught that a lot of even seriously ill COVID-19 patients can be managed safely at home, for example, using accelerated home oxygen monitoring with telelinked pulse oximeters. But in the beginning, Dr. Baughman said, “it was a new situation for us. We had seen what happened in Europe and China. It’s a great thing to be overprepared.”

References

1. Horowitz J. Italy’s health care system groans under coronavirus – a warning to the world. New York Times. 2020 Mar 12.

2. Bell SA et al. T-Minus 10 days: The role of an academic medical institution in field hospital planning. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021 Feb 18:1-6. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X21000224.

3. Singh K et al. Evaluating a widely implemented proprietary deterioration index model among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021 Jul;18(7):1129-37. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-698OC.

4. Bell SA et al. Alternate care sites during COVID-19 pandemic: Policy implications for pandemic surge planning. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021 Jul 23;1-3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.241.

More tools for the COVID toolbox

I was recently asked to see a 16-year-old, unvaccinated (against COVID-19) adolescent with hypothyroidism and obesity (body mass index 37 kg/m2) seen in the pediatric emergency department with tachycardia, O2 saturation 96%, urinary tract infection, poor appetite, and nausea. Her chest x-ray had low lung volumes but no infiltrates. She was noted to be dehydrated. Testing for COVID-19 was PCR positive.1

She was observed overnight, tolerated oral rehydration, and was being readied for discharge. Pediatric Infectious Diseases was called about prescribing remdesivir.

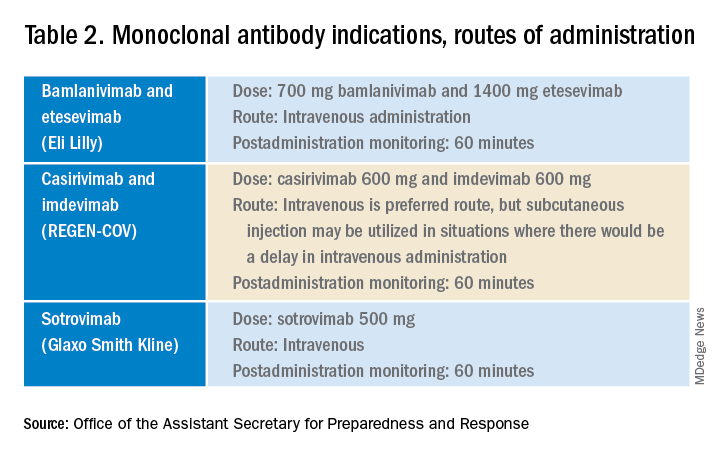

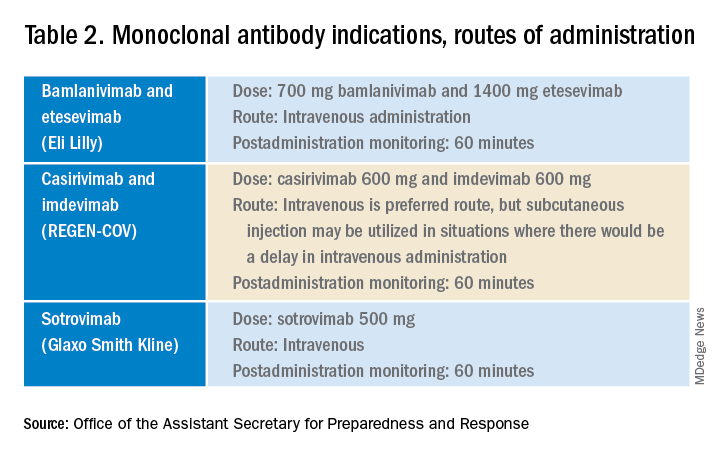

Remdesivir was not indicated as its current use is limited to inpatients with oxygen desaturations less than 94%. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines do recommend the use of monoclonal antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for prevention of COVID disease progression in high-risk individuals. Specifically, the IDSA guidelines say, “Among ambulatory patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 at high risk for progression to severe disease, bamlanivimab/etesevimab, casirivimab/imdevimab, or sotrovimab rather than no neutralizing antibody treatment.”

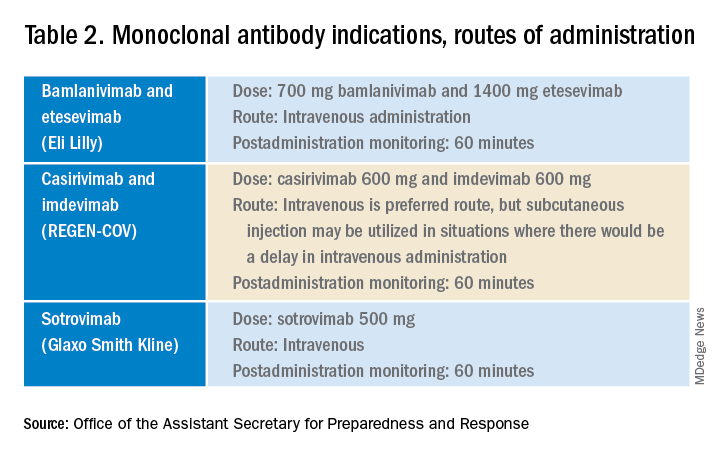

The Food and Drug Administration’s Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) allowed use of specific monoclonal antibodies (casirivimab/imdevimab in combination, bamlanivimab/etesevimab in combination, and sotrovimab alone) for individuals 12 years and above with a minimum weight of 40 kg with high-risk conditions, describing the evidence as moderate certainty.2

Several questions have arisen regarding their use. Which children qualify under the EUA? Are the available monoclonal antibodies effective for SARS-CoV-2 variants? What adverse events were observed? Are there implementation hurdles?

Unlike the EUA for prophylactic use, which targeted unvaccinated individuals and those unlikely to have a good antibody response to vaccine, use of monoclonal antibody for prevention of progression does not have such restrictions. Effectiveness may vary by local variant susceptibility and should be considered in the choice of the most appropriate monoclonal antibody therapy. Reductions in hospitalization and progression to critical disease status were reported from phase 3 studies; reductions were also observed in mortality in some, but not all, studies. Enhanced viral clearance on day 7 was observed with few subjects having persistent high viral load.

Which children qualify under the EUA? Adolescents 12 years and older and over 40 kg are eligible if a high risk condition is present. High-risk conditions include body mass index at the 85th percentile or higher, immunosuppressive disease, or receipt of immunosuppressive therapies, or baseline (pre-COVID infection) medical-related technological dependence such as tracheostomy or positive pressure ventilation. Additional high-risk conditions are neurodevelopmental disorders, sickle cell disease, congenital or acquired heart disease, asthma, or reactive airway or other chronic respiratory disease that requires daily medication for control, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or pregnancy.3

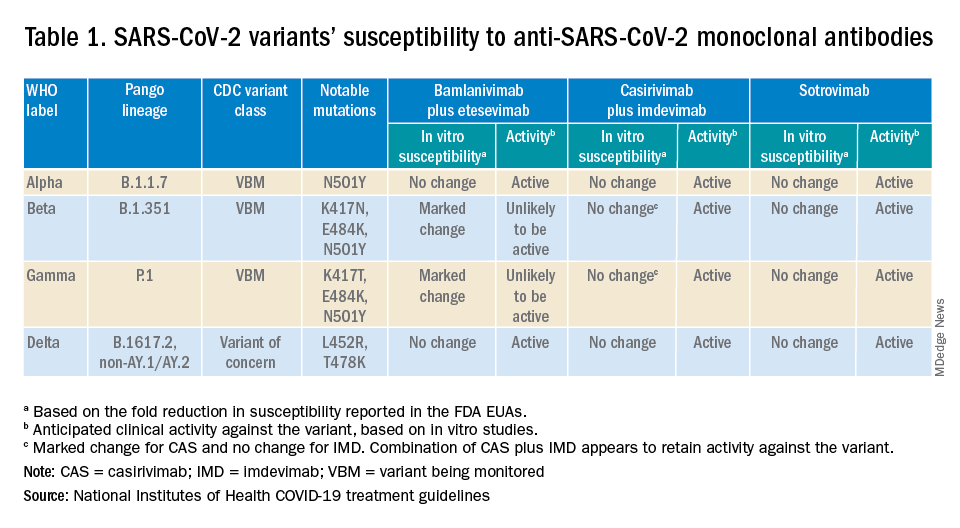

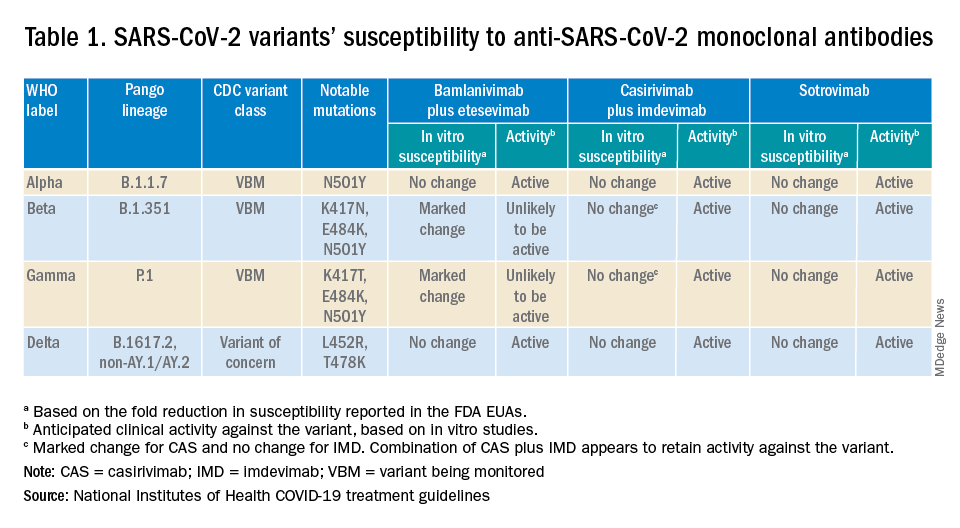

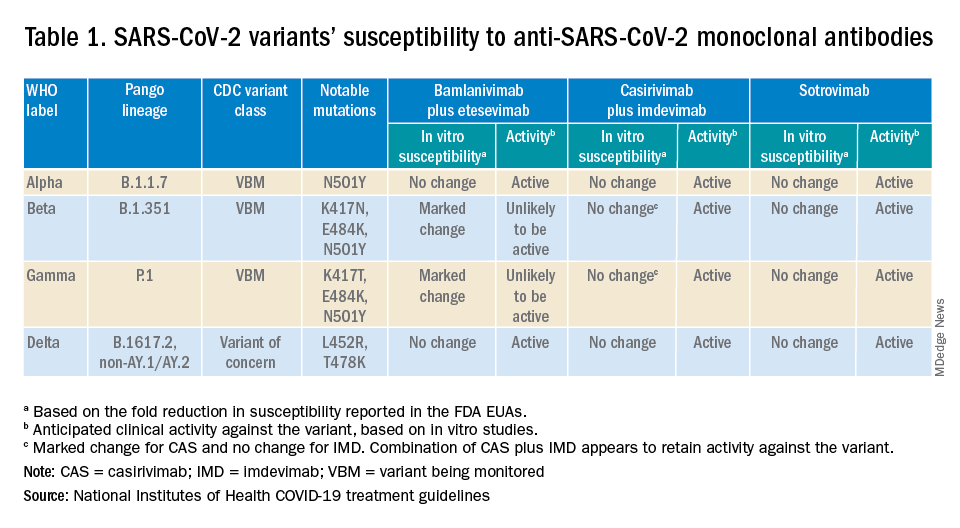

Are the available monoclonal antibodies effective for SARS-CoV-2 variants? Of course, this is a critical question and relies on knowledge of the dominant variant in a specific geographic location. The CDC data on which variants are susceptible to which monoclonal therapies were updated as of Oct. 21 online (see Table 1). Local departments of public health often will have current data on the dominant variant in the community. Currently, the dominant variant in the United States is Delta and it is anticipated to be susceptible to the three monoclonal treatments authorized under the EUA based on in vitro neutralizing assays.

What adverse events were observed? Monoclonal antibody infusions are in general safe but anaphylaxis has been reported. Other infusion-related adverse events include urticaria, pruritis, flushing, pyrexia, shortness of breath, chest tightness, nausea, vomiting, and rash. Nearly all events were grade 1, mild, or grade 2, moderate. For nonsevere infusion-related reactions, consider slowing the infusion; if necessary, the infusion should be stopped.

Implementation challenges

The first challenge is finding a location to infuse the monoclonal antibodies. Although they can be given subcutaneously, the dose is large and little, if any, time is saved as the recommendation is for observation post administration for 1 hour. The challenge we and other centers may face is that the patients are COVID PCR+ and therefore our usual infusion program, which often is occupied by individuals already compromised and at high risk for severe COVID, is an undesirable location. We are planning to use the emergency department to accommodate such patients currently, but even that solution creates challenges for a busy, urban medical center.

Summary