User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

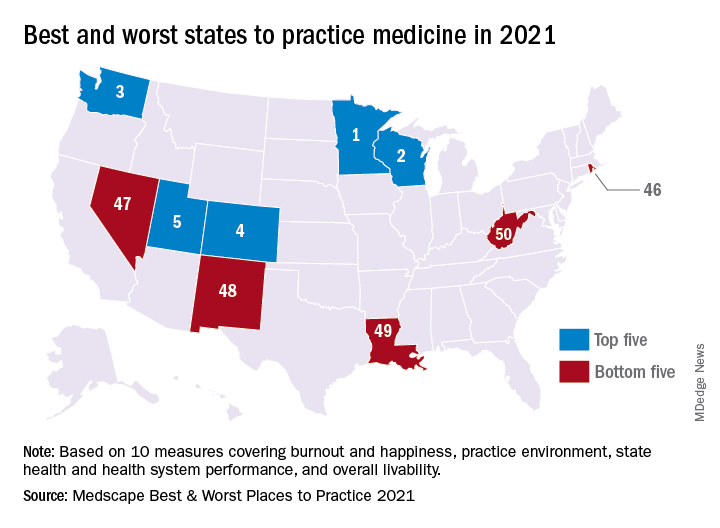

Minnesota named best place to practice in 2021

For physicians who are just starting out or thinking about moving, the “Land of 10,000 Lakes” could be the land of opportunity, according to a recent Medscape analysis.

In a ranking of the 50 states, Minnesota “claimed top marks for livability, low incidence of adverse actions against doctors, and the performance of its health system,” Shelly Reese wrote in Medscape’s “Best & Worst Places to Practice 2021.”

Minnesota is below average where it’s good to be below average – share of physicians reporting burnout and/or depression – but above average in the share of physicians who say they’re “very happy” outside of work, Medscape said in the annual report.

and adverse actions and a high level of livability. Third place went to Washington (called the most livable state in the country by U.S. News and World Report), fourth to Colorado (physicians happy at and outside of work, high retention rate for residents), and fifth to Utah (low crime rate, high quality of life), Medscape said.

At the bottom of the list for 2021 is West Virginia, where physicians “may confront a bevy of challenges” in the form of low livability, a high rate of adverse actions, and relatively high malpractice payouts, Ms. Reese noted in the report.

State number 49 is Louisiana, where livability is low, malpractice payouts are high, and more than half of physicians say that they’re burned out and/or depressed. New Mexico is 48th (very high rate of adverse actions, poor resident retention), Nevada is 47th (low marks for avoidable hospital use and disparity in care), and Rhode Island is 46th (high malpractice payouts, low physician compensation), Medscape said.

Continuing with the group-of-five theme, America’s three most populous states finished in the top half of the ranking – California 16th, Texas 11th, and Florida 21st – but New York and Pennsylvania, numbers four and five by population size, did not.

The rankings are based on states’ performance in 10 different measures, three of which were sourced from Medscape surveys – happiness at work, happiness outside of work, and burnout/depression – and seven from other organizations: adverse actions against physicians, malpractice payouts, compensation (adjusted for cost of living), overall health, health system performance, overall livability, resident retention.

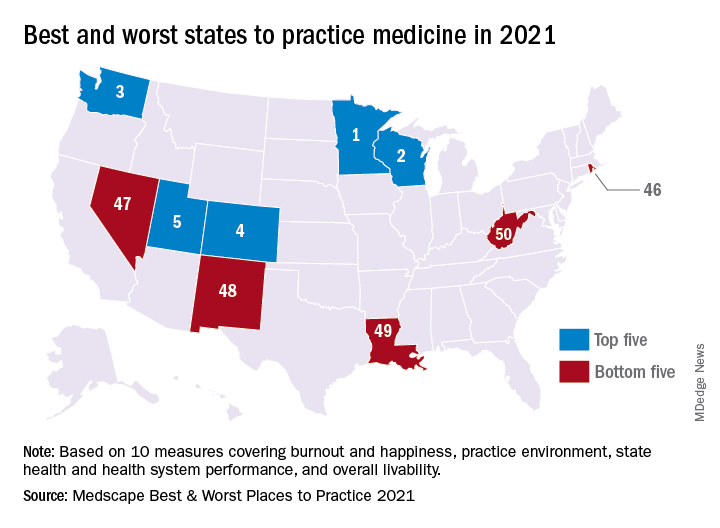

For physicians who are just starting out or thinking about moving, the “Land of 10,000 Lakes” could be the land of opportunity, according to a recent Medscape analysis.

In a ranking of the 50 states, Minnesota “claimed top marks for livability, low incidence of adverse actions against doctors, and the performance of its health system,” Shelly Reese wrote in Medscape’s “Best & Worst Places to Practice 2021.”

Minnesota is below average where it’s good to be below average – share of physicians reporting burnout and/or depression – but above average in the share of physicians who say they’re “very happy” outside of work, Medscape said in the annual report.

and adverse actions and a high level of livability. Third place went to Washington (called the most livable state in the country by U.S. News and World Report), fourth to Colorado (physicians happy at and outside of work, high retention rate for residents), and fifth to Utah (low crime rate, high quality of life), Medscape said.

At the bottom of the list for 2021 is West Virginia, where physicians “may confront a bevy of challenges” in the form of low livability, a high rate of adverse actions, and relatively high malpractice payouts, Ms. Reese noted in the report.

State number 49 is Louisiana, where livability is low, malpractice payouts are high, and more than half of physicians say that they’re burned out and/or depressed. New Mexico is 48th (very high rate of adverse actions, poor resident retention), Nevada is 47th (low marks for avoidable hospital use and disparity in care), and Rhode Island is 46th (high malpractice payouts, low physician compensation), Medscape said.

Continuing with the group-of-five theme, America’s three most populous states finished in the top half of the ranking – California 16th, Texas 11th, and Florida 21st – but New York and Pennsylvania, numbers four and five by population size, did not.

The rankings are based on states’ performance in 10 different measures, three of which were sourced from Medscape surveys – happiness at work, happiness outside of work, and burnout/depression – and seven from other organizations: adverse actions against physicians, malpractice payouts, compensation (adjusted for cost of living), overall health, health system performance, overall livability, resident retention.

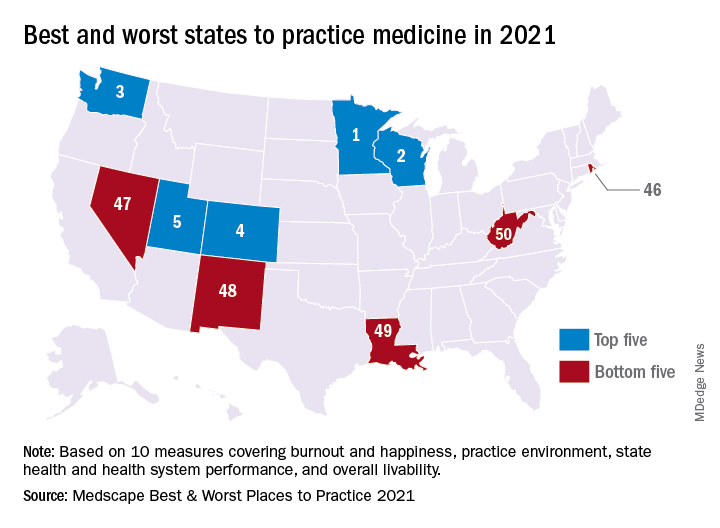

For physicians who are just starting out or thinking about moving, the “Land of 10,000 Lakes” could be the land of opportunity, according to a recent Medscape analysis.

In a ranking of the 50 states, Minnesota “claimed top marks for livability, low incidence of adverse actions against doctors, and the performance of its health system,” Shelly Reese wrote in Medscape’s “Best & Worst Places to Practice 2021.”

Minnesota is below average where it’s good to be below average – share of physicians reporting burnout and/or depression – but above average in the share of physicians who say they’re “very happy” outside of work, Medscape said in the annual report.

and adverse actions and a high level of livability. Third place went to Washington (called the most livable state in the country by U.S. News and World Report), fourth to Colorado (physicians happy at and outside of work, high retention rate for residents), and fifth to Utah (low crime rate, high quality of life), Medscape said.

At the bottom of the list for 2021 is West Virginia, where physicians “may confront a bevy of challenges” in the form of low livability, a high rate of adverse actions, and relatively high malpractice payouts, Ms. Reese noted in the report.

State number 49 is Louisiana, where livability is low, malpractice payouts are high, and more than half of physicians say that they’re burned out and/or depressed. New Mexico is 48th (very high rate of adverse actions, poor resident retention), Nevada is 47th (low marks for avoidable hospital use and disparity in care), and Rhode Island is 46th (high malpractice payouts, low physician compensation), Medscape said.

Continuing with the group-of-five theme, America’s three most populous states finished in the top half of the ranking – California 16th, Texas 11th, and Florida 21st – but New York and Pennsylvania, numbers four and five by population size, did not.

The rankings are based on states’ performance in 10 different measures, three of which were sourced from Medscape surveys – happiness at work, happiness outside of work, and burnout/depression – and seven from other organizations: adverse actions against physicians, malpractice payouts, compensation (adjusted for cost of living), overall health, health system performance, overall livability, resident retention.

Third COVID-19 vaccine dose helped some transplant recipients

All of those with low titers before the third dose had high titers after receiving the additional shot, but only about 33% of those with negative initial responses had detectable antibodies after the third dose, according to the paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, who keep a COVID-19 vaccine registry, perform antibody tests on all registry subjects and inform them of their results. Registry participants were asked to inform the research team if they received a third dose, and, the research team tracked the immune responses of those who did.

The participants in this case series had low antibody levels and received a third dose of the vaccine on their own between March 20 and May 10 of 2021.

Third dose results

In this cases series – thought to be the first to look at third vaccine shots in this type of patient group – all six of those who had low antibody titers before the third dose had high-positive titers after the third dose.

Of the 24 individuals who had negative antibody titers before the third dose, just 6 had high titers after the third dose.

Two of the participants had low-positive titers, and 16 were negative.

“Several of those boosted very nicely into ranges seen, using these assays, in healthy persons,” said William Werbel, MD, a fellow in infectious disease at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who helped lead the study. Those with negative levels, even if they responded, tended to have lower titers, he said.

“The benefits at least from an antibody perspective were not the same for everybody and so this is obviously something that needs to be considered when thinking about selecting patients” for a COVID-19 prevention strategy, he said.

Reactions to the vaccine were low to moderate, such as some arm pain and fatigue.

“Showing that something is safe in that special, vulnerable population is important,” Dr. Werbel said. “We’re all wanting to make sure that we’re doing no harm.”

Dr. Werbel noted that there was no pattern in the small series based on the organ transplanted or in the vaccines used. As their third shot, 15 of the patients received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine; 9 received Moderna; and 6 received Pfizer-BioNTech.

Welcome news, but larger studies needed

“To think that a third dose could confer protection for a significant number of people is of course extremely welcome news,” said Christian Larsen, MD, DPhil, professor of surgery in the transplantation division at Emory University, Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. “It’s the easiest conceivable next intervention.”

He added, “We just want studies to confirm that – larger studies.”

Dr. Werbel stressed the importance of looking at third doses in these patients in a more controlled fashion in a randomized trial, to more carefully monitor safety and how patients fare when starting with one type of vaccine and switching to another, for example.

Richard Wender, MD, chair of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings are a reminder that there is still a lot that is unknown about COVID-19 and vaccination.

“We still don’t know who will or will not benefit from a third dose,” he said. “And our knowledge is evolving. For example, a recent study suggested that people with previous infection and who are vaccinated may have better and longer protection than people with vaccination alone. We’re still learning.”

He added that specialists, not primary care clinicians, should be relied upon to respond to this emerging vaccination data. Primary care doctors are very busy in other ways – such as in getting children caught up on vaccinations and helping adults return to managing their chronic diseases, Dr. Wender noted.

“Their focus needs to be on helping to overcome hesitancy, mistrust, lack of information, or antivaccination sentiment to help more people feel comfortable being vaccinated – this is a lot of work and needs constant focus. In short, primary care clinicians need to focus chiefly on the unvaccinated,” he said.

“Monitoring immunization recommendations for unique at-risk populations should be the chief responsibility of teams providing subspecialty care, [such as for] transplant patients, people with chronic kidney disease, cancer patients, and people with other chronic illnesses. This will allow primary care clinicians to tackle their many complex jobs.”

Possible solutions for those with low antibody responses

Dr. Larsen said that those with ongoing low antibody responses might still have other immune responses, such as a T-cell response. Such patients also could consider changing their vaccine type, he said.

“At the more significant intervention level, there may be circumstances where one could change the immunosuppressive drugs in a controlled way that might allow a better response,” suggested Dr. Larsen. “That’s obviously going to be something that requires a lot more thought and careful study.”

Dr. Werbel said that other options might need to be considered for those having no response following a third dose. One possibility is trying a vaccine with an adjuvant, such as the Novavax version, which might be more widely available soon.

“If you’re given a third dose of a very immunogenic vaccine – something that should work – and you just have no antibody development, it seems relatively unlikely that doing the same thing again is going to help you from that perspective, and for all we know might expose you to more risk,” Dr. Werbel noted.

Participant details

None of the 30 patients were thought to have ever had COVID-19. On average, patients had received their transplant 4.5 years before their original vaccination. In 25 patients, maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus or cyclosporine along with mycophenolate. Corticosteroids were also used for 24 patients, sirolimus was used for one patient, and belatacept was used for another patient.

Fifty-seven percent of patients had received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine originally, and 43% the Moderna vaccine. Most of the patients were kidney recipients, with two heart, three liver, one lung, one pancreas and one kidney-pancreas.

Dr. Werbel, Dr. Wender, and Dr. Larsen reported no relevant disclosures.

All of those with low titers before the third dose had high titers after receiving the additional shot, but only about 33% of those with negative initial responses had detectable antibodies after the third dose, according to the paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, who keep a COVID-19 vaccine registry, perform antibody tests on all registry subjects and inform them of their results. Registry participants were asked to inform the research team if they received a third dose, and, the research team tracked the immune responses of those who did.

The participants in this case series had low antibody levels and received a third dose of the vaccine on their own between March 20 and May 10 of 2021.

Third dose results

In this cases series – thought to be the first to look at third vaccine shots in this type of patient group – all six of those who had low antibody titers before the third dose had high-positive titers after the third dose.

Of the 24 individuals who had negative antibody titers before the third dose, just 6 had high titers after the third dose.

Two of the participants had low-positive titers, and 16 were negative.

“Several of those boosted very nicely into ranges seen, using these assays, in healthy persons,” said William Werbel, MD, a fellow in infectious disease at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who helped lead the study. Those with negative levels, even if they responded, tended to have lower titers, he said.

“The benefits at least from an antibody perspective were not the same for everybody and so this is obviously something that needs to be considered when thinking about selecting patients” for a COVID-19 prevention strategy, he said.

Reactions to the vaccine were low to moderate, such as some arm pain and fatigue.

“Showing that something is safe in that special, vulnerable population is important,” Dr. Werbel said. “We’re all wanting to make sure that we’re doing no harm.”

Dr. Werbel noted that there was no pattern in the small series based on the organ transplanted or in the vaccines used. As their third shot, 15 of the patients received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine; 9 received Moderna; and 6 received Pfizer-BioNTech.

Welcome news, but larger studies needed

“To think that a third dose could confer protection for a significant number of people is of course extremely welcome news,” said Christian Larsen, MD, DPhil, professor of surgery in the transplantation division at Emory University, Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. “It’s the easiest conceivable next intervention.”

He added, “We just want studies to confirm that – larger studies.”

Dr. Werbel stressed the importance of looking at third doses in these patients in a more controlled fashion in a randomized trial, to more carefully monitor safety and how patients fare when starting with one type of vaccine and switching to another, for example.

Richard Wender, MD, chair of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings are a reminder that there is still a lot that is unknown about COVID-19 and vaccination.

“We still don’t know who will or will not benefit from a third dose,” he said. “And our knowledge is evolving. For example, a recent study suggested that people with previous infection and who are vaccinated may have better and longer protection than people with vaccination alone. We’re still learning.”

He added that specialists, not primary care clinicians, should be relied upon to respond to this emerging vaccination data. Primary care doctors are very busy in other ways – such as in getting children caught up on vaccinations and helping adults return to managing their chronic diseases, Dr. Wender noted.

“Their focus needs to be on helping to overcome hesitancy, mistrust, lack of information, or antivaccination sentiment to help more people feel comfortable being vaccinated – this is a lot of work and needs constant focus. In short, primary care clinicians need to focus chiefly on the unvaccinated,” he said.

“Monitoring immunization recommendations for unique at-risk populations should be the chief responsibility of teams providing subspecialty care, [such as for] transplant patients, people with chronic kidney disease, cancer patients, and people with other chronic illnesses. This will allow primary care clinicians to tackle their many complex jobs.”

Possible solutions for those with low antibody responses

Dr. Larsen said that those with ongoing low antibody responses might still have other immune responses, such as a T-cell response. Such patients also could consider changing their vaccine type, he said.

“At the more significant intervention level, there may be circumstances where one could change the immunosuppressive drugs in a controlled way that might allow a better response,” suggested Dr. Larsen. “That’s obviously going to be something that requires a lot more thought and careful study.”

Dr. Werbel said that other options might need to be considered for those having no response following a third dose. One possibility is trying a vaccine with an adjuvant, such as the Novavax version, which might be more widely available soon.

“If you’re given a third dose of a very immunogenic vaccine – something that should work – and you just have no antibody development, it seems relatively unlikely that doing the same thing again is going to help you from that perspective, and for all we know might expose you to more risk,” Dr. Werbel noted.

Participant details

None of the 30 patients were thought to have ever had COVID-19. On average, patients had received their transplant 4.5 years before their original vaccination. In 25 patients, maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus or cyclosporine along with mycophenolate. Corticosteroids were also used for 24 patients, sirolimus was used for one patient, and belatacept was used for another patient.

Fifty-seven percent of patients had received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine originally, and 43% the Moderna vaccine. Most of the patients were kidney recipients, with two heart, three liver, one lung, one pancreas and one kidney-pancreas.

Dr. Werbel, Dr. Wender, and Dr. Larsen reported no relevant disclosures.

All of those with low titers before the third dose had high titers after receiving the additional shot, but only about 33% of those with negative initial responses had detectable antibodies after the third dose, according to the paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, who keep a COVID-19 vaccine registry, perform antibody tests on all registry subjects and inform them of their results. Registry participants were asked to inform the research team if they received a third dose, and, the research team tracked the immune responses of those who did.

The participants in this case series had low antibody levels and received a third dose of the vaccine on their own between March 20 and May 10 of 2021.

Third dose results

In this cases series – thought to be the first to look at third vaccine shots in this type of patient group – all six of those who had low antibody titers before the third dose had high-positive titers after the third dose.

Of the 24 individuals who had negative antibody titers before the third dose, just 6 had high titers after the third dose.

Two of the participants had low-positive titers, and 16 were negative.

“Several of those boosted very nicely into ranges seen, using these assays, in healthy persons,” said William Werbel, MD, a fellow in infectious disease at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who helped lead the study. Those with negative levels, even if they responded, tended to have lower titers, he said.

“The benefits at least from an antibody perspective were not the same for everybody and so this is obviously something that needs to be considered when thinking about selecting patients” for a COVID-19 prevention strategy, he said.

Reactions to the vaccine were low to moderate, such as some arm pain and fatigue.

“Showing that something is safe in that special, vulnerable population is important,” Dr. Werbel said. “We’re all wanting to make sure that we’re doing no harm.”

Dr. Werbel noted that there was no pattern in the small series based on the organ transplanted or in the vaccines used. As their third shot, 15 of the patients received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine; 9 received Moderna; and 6 received Pfizer-BioNTech.

Welcome news, but larger studies needed

“To think that a third dose could confer protection for a significant number of people is of course extremely welcome news,” said Christian Larsen, MD, DPhil, professor of surgery in the transplantation division at Emory University, Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. “It’s the easiest conceivable next intervention.”

He added, “We just want studies to confirm that – larger studies.”

Dr. Werbel stressed the importance of looking at third doses in these patients in a more controlled fashion in a randomized trial, to more carefully monitor safety and how patients fare when starting with one type of vaccine and switching to another, for example.

Richard Wender, MD, chair of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings are a reminder that there is still a lot that is unknown about COVID-19 and vaccination.

“We still don’t know who will or will not benefit from a third dose,” he said. “And our knowledge is evolving. For example, a recent study suggested that people with previous infection and who are vaccinated may have better and longer protection than people with vaccination alone. We’re still learning.”

He added that specialists, not primary care clinicians, should be relied upon to respond to this emerging vaccination data. Primary care doctors are very busy in other ways – such as in getting children caught up on vaccinations and helping adults return to managing their chronic diseases, Dr. Wender noted.

“Their focus needs to be on helping to overcome hesitancy, mistrust, lack of information, or antivaccination sentiment to help more people feel comfortable being vaccinated – this is a lot of work and needs constant focus. In short, primary care clinicians need to focus chiefly on the unvaccinated,” he said.

“Monitoring immunization recommendations for unique at-risk populations should be the chief responsibility of teams providing subspecialty care, [such as for] transplant patients, people with chronic kidney disease, cancer patients, and people with other chronic illnesses. This will allow primary care clinicians to tackle their many complex jobs.”

Possible solutions for those with low antibody responses

Dr. Larsen said that those with ongoing low antibody responses might still have other immune responses, such as a T-cell response. Such patients also could consider changing their vaccine type, he said.

“At the more significant intervention level, there may be circumstances where one could change the immunosuppressive drugs in a controlled way that might allow a better response,” suggested Dr. Larsen. “That’s obviously going to be something that requires a lot more thought and careful study.”

Dr. Werbel said that other options might need to be considered for those having no response following a third dose. One possibility is trying a vaccine with an adjuvant, such as the Novavax version, which might be more widely available soon.

“If you’re given a third dose of a very immunogenic vaccine – something that should work – and you just have no antibody development, it seems relatively unlikely that doing the same thing again is going to help you from that perspective, and for all we know might expose you to more risk,” Dr. Werbel noted.

Participant details

None of the 30 patients were thought to have ever had COVID-19. On average, patients had received their transplant 4.5 years before their original vaccination. In 25 patients, maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus or cyclosporine along with mycophenolate. Corticosteroids were also used for 24 patients, sirolimus was used for one patient, and belatacept was used for another patient.

Fifty-seven percent of patients had received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine originally, and 43% the Moderna vaccine. Most of the patients were kidney recipients, with two heart, three liver, one lung, one pancreas and one kidney-pancreas.

Dr. Werbel, Dr. Wender, and Dr. Larsen reported no relevant disclosures.

The Cures Act: Is the “cure” worse than the disease?

There is a sudden spill of icy anxiety down your spine as you pick up your phone in your shaking hands. It’s 6 p.m.; your doctor’s office is closed. You open the message, and your worst fears are confirmed ... the cancer is back.

Or is it? You’re not sure. The biopsy sure sounds bad. But you’re an English teacher, not a doctor, and you spend the rest of the night Googling words like “tubulovillous” and “high-grade dysplasia.” You sit awake, terrified in front of the computer screen desperately trying to make sense of the possibly life-changing results. You wish you knew someone who could help you understand; you consider calling your doctor’s emergency line, or your cousin who is an ophthalmologist – anybody who can help you make sense of the results.

Or imagine another scenario: you’re a trans teen who has asked your doctor to refer to you by your preferred pronouns. You’re still presenting as your birth sex, in part because your family would disown you if they knew, and you’re not financially or emotionally ready for that step. You feel proud of yourself for advocating for your needs to your long-time physician, and excited about the resources they’ve included in your after visit summary and the referrals they’d made to gender-confirming specialists.

When you get home, you are confronted with a terrible reality that your doctor’s notes, orders, and recommendations are immediately viewable to anybody with your MyChart login – your parents knew the second your doctor signed the note. They received the notification, logged on as your guardians, and you have effectively been “outed” by the physician who took and oath to care for you and who you trusted implicitly.

How the Cures Act is affecting patients

While these examples may sound extreme, they are becoming more and more commonplace thanks to a recently enacted 21st Century Cures Act. The act was originally written to improve communication between physicians and patients. Part of the act stipulates that nearly all medical information – from notes to biopsies to lab results – must be available within 24 hours, published to a patient portal and a notification be sent to the patient by phone.

Oftentimes, this occurs before the ordering physician has even seen the results, much less interpreted them and made a plan for the patient. What happens now, not long after its enactment date, when it has become clear that the Cures Act is causing extreme harm to our patients?

Take, for example, the real example of a physician whose patient found out about her own intrauterine fetal demise by way of an EMR text message alert of “new imaging results!” sent directly to her phone. Or a physician colleague who witnessed firsthand the intrusive unhelpfulness of the Cures Act when she was informed via patient portal releasing her imaging information that she had a large, possibly malignant breast mass. “No phone call,” she said. “No human being for questions or comfort. Just a notification on my phone.”

The stories about the impact of the Cures Act across the medical community are an endless stream of anxiety, hurt, and broken trust. The relationship between a physician and a patient should be sacred, bolstered by communication and mutual respect.

In many ways, the new act feels like a third party to the patient-physician relationship – a digital imposter, oftentimes blurting out personal and life-altering medical information without any of the finesse, context, and perspective of an experienced physician.

Breaking ‘bad news’ to a patient

In training, some residents are taught how to “break bad news” to a patient. Some good practices for doing this are to have information available for the patient, provide emotional support, have a plan for their next steps already formulated, and call the appropriate specialist ahead of time if you can.

Above all, it’s most important to let the patient be the one to direct their own care. Give them time to ask questions and answer them honestly and clearly. Ask them how much they want to know and help them to understand the complex change in their usual state of health.

Now, unless physicians are keeping a very close eye on their inbox, results are slipping out to patients in a void. The bad news conversations aren’t happening at all, or if they are, they’re happening at 8 p.m. on a phone call after an exhausted physician ends their shift but has to slog through their results bin, calling all the patients who shouldn’t have to find out their results in solitude.

Reaching out to these patients immediately is an honorable, kind thing to, but for a physician, knowing they need to beat the patient to opening an email creates anxiety. Plus, making these calls at whatever hour the results are released to a patient is another burden added to doctors’ already-full plates.

Interpreting results

None of us want to harm our patients. All of us want to be there for them. But this act stands in the way of delivering quality, humanizing medical care.

It is true that patients have a right to access their own medical information. It is also true that waiting anxiously on results can cause undue harm to a patient. But the across-the-board, breakneck speed of information release mandated in this act causes irreparable harm not only to patients, but to the patient-physician relationship.

No patient should find out their cancer recurred while checking their emails at their desk. No patient should first learn of a life-altering diagnosis by way of scrolling through their smartphone in bed. The role of a physician is more than just a healer – we should also be educators, interpreters, partners and, first and foremost, advocates for our patients’ needs.

Our patients are depending on us to stand up and speak out about necessary changes to this act. Result releases should be delayed until they are viewed by a physician. Our patients deserve the dignity and opportunity of a conversation with their medical provider about their test results, and physicians deserve the chance to interpret results and frame the conversation in a way which is conducive to patient understanding and healing.

Dr. Persampiere is a first-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. You can contact them at [email protected].

There is a sudden spill of icy anxiety down your spine as you pick up your phone in your shaking hands. It’s 6 p.m.; your doctor’s office is closed. You open the message, and your worst fears are confirmed ... the cancer is back.

Or is it? You’re not sure. The biopsy sure sounds bad. But you’re an English teacher, not a doctor, and you spend the rest of the night Googling words like “tubulovillous” and “high-grade dysplasia.” You sit awake, terrified in front of the computer screen desperately trying to make sense of the possibly life-changing results. You wish you knew someone who could help you understand; you consider calling your doctor’s emergency line, or your cousin who is an ophthalmologist – anybody who can help you make sense of the results.

Or imagine another scenario: you’re a trans teen who has asked your doctor to refer to you by your preferred pronouns. You’re still presenting as your birth sex, in part because your family would disown you if they knew, and you’re not financially or emotionally ready for that step. You feel proud of yourself for advocating for your needs to your long-time physician, and excited about the resources they’ve included in your after visit summary and the referrals they’d made to gender-confirming specialists.

When you get home, you are confronted with a terrible reality that your doctor’s notes, orders, and recommendations are immediately viewable to anybody with your MyChart login – your parents knew the second your doctor signed the note. They received the notification, logged on as your guardians, and you have effectively been “outed” by the physician who took and oath to care for you and who you trusted implicitly.

How the Cures Act is affecting patients

While these examples may sound extreme, they are becoming more and more commonplace thanks to a recently enacted 21st Century Cures Act. The act was originally written to improve communication between physicians and patients. Part of the act stipulates that nearly all medical information – from notes to biopsies to lab results – must be available within 24 hours, published to a patient portal and a notification be sent to the patient by phone.

Oftentimes, this occurs before the ordering physician has even seen the results, much less interpreted them and made a plan for the patient. What happens now, not long after its enactment date, when it has become clear that the Cures Act is causing extreme harm to our patients?

Take, for example, the real example of a physician whose patient found out about her own intrauterine fetal demise by way of an EMR text message alert of “new imaging results!” sent directly to her phone. Or a physician colleague who witnessed firsthand the intrusive unhelpfulness of the Cures Act when she was informed via patient portal releasing her imaging information that she had a large, possibly malignant breast mass. “No phone call,” she said. “No human being for questions or comfort. Just a notification on my phone.”

The stories about the impact of the Cures Act across the medical community are an endless stream of anxiety, hurt, and broken trust. The relationship between a physician and a patient should be sacred, bolstered by communication and mutual respect.

In many ways, the new act feels like a third party to the patient-physician relationship – a digital imposter, oftentimes blurting out personal and life-altering medical information without any of the finesse, context, and perspective of an experienced physician.

Breaking ‘bad news’ to a patient

In training, some residents are taught how to “break bad news” to a patient. Some good practices for doing this are to have information available for the patient, provide emotional support, have a plan for their next steps already formulated, and call the appropriate specialist ahead of time if you can.

Above all, it’s most important to let the patient be the one to direct their own care. Give them time to ask questions and answer them honestly and clearly. Ask them how much they want to know and help them to understand the complex change in their usual state of health.

Now, unless physicians are keeping a very close eye on their inbox, results are slipping out to patients in a void. The bad news conversations aren’t happening at all, or if they are, they’re happening at 8 p.m. on a phone call after an exhausted physician ends their shift but has to slog through their results bin, calling all the patients who shouldn’t have to find out their results in solitude.

Reaching out to these patients immediately is an honorable, kind thing to, but for a physician, knowing they need to beat the patient to opening an email creates anxiety. Plus, making these calls at whatever hour the results are released to a patient is another burden added to doctors’ already-full plates.

Interpreting results

None of us want to harm our patients. All of us want to be there for them. But this act stands in the way of delivering quality, humanizing medical care.

It is true that patients have a right to access their own medical information. It is also true that waiting anxiously on results can cause undue harm to a patient. But the across-the-board, breakneck speed of information release mandated in this act causes irreparable harm not only to patients, but to the patient-physician relationship.

No patient should find out their cancer recurred while checking their emails at their desk. No patient should first learn of a life-altering diagnosis by way of scrolling through their smartphone in bed. The role of a physician is more than just a healer – we should also be educators, interpreters, partners and, first and foremost, advocates for our patients’ needs.

Our patients are depending on us to stand up and speak out about necessary changes to this act. Result releases should be delayed until they are viewed by a physician. Our patients deserve the dignity and opportunity of a conversation with their medical provider about their test results, and physicians deserve the chance to interpret results and frame the conversation in a way which is conducive to patient understanding and healing.

Dr. Persampiere is a first-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. You can contact them at [email protected].

There is a sudden spill of icy anxiety down your spine as you pick up your phone in your shaking hands. It’s 6 p.m.; your doctor’s office is closed. You open the message, and your worst fears are confirmed ... the cancer is back.

Or is it? You’re not sure. The biopsy sure sounds bad. But you’re an English teacher, not a doctor, and you spend the rest of the night Googling words like “tubulovillous” and “high-grade dysplasia.” You sit awake, terrified in front of the computer screen desperately trying to make sense of the possibly life-changing results. You wish you knew someone who could help you understand; you consider calling your doctor’s emergency line, or your cousin who is an ophthalmologist – anybody who can help you make sense of the results.

Or imagine another scenario: you’re a trans teen who has asked your doctor to refer to you by your preferred pronouns. You’re still presenting as your birth sex, in part because your family would disown you if they knew, and you’re not financially or emotionally ready for that step. You feel proud of yourself for advocating for your needs to your long-time physician, and excited about the resources they’ve included in your after visit summary and the referrals they’d made to gender-confirming specialists.

When you get home, you are confronted with a terrible reality that your doctor’s notes, orders, and recommendations are immediately viewable to anybody with your MyChart login – your parents knew the second your doctor signed the note. They received the notification, logged on as your guardians, and you have effectively been “outed” by the physician who took and oath to care for you and who you trusted implicitly.

How the Cures Act is affecting patients

While these examples may sound extreme, they are becoming more and more commonplace thanks to a recently enacted 21st Century Cures Act. The act was originally written to improve communication between physicians and patients. Part of the act stipulates that nearly all medical information – from notes to biopsies to lab results – must be available within 24 hours, published to a patient portal and a notification be sent to the patient by phone.

Oftentimes, this occurs before the ordering physician has even seen the results, much less interpreted them and made a plan for the patient. What happens now, not long after its enactment date, when it has become clear that the Cures Act is causing extreme harm to our patients?

Take, for example, the real example of a physician whose patient found out about her own intrauterine fetal demise by way of an EMR text message alert of “new imaging results!” sent directly to her phone. Or a physician colleague who witnessed firsthand the intrusive unhelpfulness of the Cures Act when she was informed via patient portal releasing her imaging information that she had a large, possibly malignant breast mass. “No phone call,” she said. “No human being for questions or comfort. Just a notification on my phone.”

The stories about the impact of the Cures Act across the medical community are an endless stream of anxiety, hurt, and broken trust. The relationship between a physician and a patient should be sacred, bolstered by communication and mutual respect.

In many ways, the new act feels like a third party to the patient-physician relationship – a digital imposter, oftentimes blurting out personal and life-altering medical information without any of the finesse, context, and perspective of an experienced physician.

Breaking ‘bad news’ to a patient

In training, some residents are taught how to “break bad news” to a patient. Some good practices for doing this are to have information available for the patient, provide emotional support, have a plan for their next steps already formulated, and call the appropriate specialist ahead of time if you can.

Above all, it’s most important to let the patient be the one to direct their own care. Give them time to ask questions and answer them honestly and clearly. Ask them how much they want to know and help them to understand the complex change in their usual state of health.

Now, unless physicians are keeping a very close eye on their inbox, results are slipping out to patients in a void. The bad news conversations aren’t happening at all, or if they are, they’re happening at 8 p.m. on a phone call after an exhausted physician ends their shift but has to slog through their results bin, calling all the patients who shouldn’t have to find out their results in solitude.

Reaching out to these patients immediately is an honorable, kind thing to, but for a physician, knowing they need to beat the patient to opening an email creates anxiety. Plus, making these calls at whatever hour the results are released to a patient is another burden added to doctors’ already-full plates.

Interpreting results

None of us want to harm our patients. All of us want to be there for them. But this act stands in the way of delivering quality, humanizing medical care.

It is true that patients have a right to access their own medical information. It is also true that waiting anxiously on results can cause undue harm to a patient. But the across-the-board, breakneck speed of information release mandated in this act causes irreparable harm not only to patients, but to the patient-physician relationship.

No patient should find out their cancer recurred while checking their emails at their desk. No patient should first learn of a life-altering diagnosis by way of scrolling through their smartphone in bed. The role of a physician is more than just a healer – we should also be educators, interpreters, partners and, first and foremost, advocates for our patients’ needs.

Our patients are depending on us to stand up and speak out about necessary changes to this act. Result releases should be delayed until they are viewed by a physician. Our patients deserve the dignity and opportunity of a conversation with their medical provider about their test results, and physicians deserve the chance to interpret results and frame the conversation in a way which is conducive to patient understanding and healing.

Dr. Persampiere is a first-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. You can contact them at [email protected].

Judge tosses hospital staff suit over vaccine mandate

A federal judge in Texas has dismissed a lawsuit from 117 Houston Methodist Hospital workers who refused to get a COVID-19 vaccine and said it was illegal to require them to do so.

In the ruling issued June 12, U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes upheld the hospital’s policy and said the vaccination requirement didn’t break any federal laws.

“This is not coercion,” Judge Hughes wrote in the ruling.

“Methodist is trying to do their business of saving lives without giving them the COVID-19 virus,” he wrote. “It is a choice made to keep staff, patients, and their families safer.”

In April, the Houston Methodist Hospital system announced a policy that required employees to be vaccinated by June 7 or request an exemption. After the deadline, 178 of 26,000 employees refused to get inoculated and were placed on suspension without pay. The employees said the vaccine was unsafe and “experimental.” In his ruling, Judge Hughes said their claim was false and irrelevant.

“Texas law only protects employees from being terminated for refusing to commit an act carrying criminal penalties to the worker,” he wrote. “Receiving a COVID-19 vaccination is not an illegal act, and it carries no criminal penalties.”

He denounced the “press-release style of the complaint” and the comparison of the hospital’s vaccine policy to forced experimentation by the Nazis against Jewish people during the Holocaust.

“Equating the injection requirement to medical experimentation in concentration camps is reprehensible,” he wrote. “Nazi doctors conducted medical experiments on victims that caused pain, mutilation, permanent disability, and in many cases, death.”

Judge Hughes also said that employees can “freely choose” to accept or refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. If they refuse, they “simply need to work somewhere else,” he wrote.

“If a worker refuses an assignment, changed office, earlier start time, or other directive, he may be properly fired,” Judge Hughes said. “Every employment includes limits on the worker’s behavior in exchange for his remuneration. This is all part of the bargain.”

The ruling could set a precedent for similar COVID-19 vaccine lawsuits across the country, NPR reported. Houston Methodist was one of the first hospitals to require staff to be vaccinated. After the ruling on June 12, the hospital system wrote in a statement that it was “pleased and reassured” that Judge Hughes dismissed a “frivolous lawsuit.”

The hospital system will begin to terminate the 178 employees who were suspended if they don’t get a vaccine by June 21.

Jennifer Bridges, a nurse who has led the campaign against the vaccine policy, said she and the other plaintiffs will appeal the decision, according to KHOU.

“We’re OK with this decision. We are appealing. This will be taken all the way to the Supreme Court,” she told the news station. “This is far from over. This is literally only the beginning.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A federal judge in Texas has dismissed a lawsuit from 117 Houston Methodist Hospital workers who refused to get a COVID-19 vaccine and said it was illegal to require them to do so.

In the ruling issued June 12, U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes upheld the hospital’s policy and said the vaccination requirement didn’t break any federal laws.

“This is not coercion,” Judge Hughes wrote in the ruling.

“Methodist is trying to do their business of saving lives without giving them the COVID-19 virus,” he wrote. “It is a choice made to keep staff, patients, and their families safer.”

In April, the Houston Methodist Hospital system announced a policy that required employees to be vaccinated by June 7 or request an exemption. After the deadline, 178 of 26,000 employees refused to get inoculated and were placed on suspension without pay. The employees said the vaccine was unsafe and “experimental.” In his ruling, Judge Hughes said their claim was false and irrelevant.

“Texas law only protects employees from being terminated for refusing to commit an act carrying criminal penalties to the worker,” he wrote. “Receiving a COVID-19 vaccination is not an illegal act, and it carries no criminal penalties.”

He denounced the “press-release style of the complaint” and the comparison of the hospital’s vaccine policy to forced experimentation by the Nazis against Jewish people during the Holocaust.

“Equating the injection requirement to medical experimentation in concentration camps is reprehensible,” he wrote. “Nazi doctors conducted medical experiments on victims that caused pain, mutilation, permanent disability, and in many cases, death.”

Judge Hughes also said that employees can “freely choose” to accept or refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. If they refuse, they “simply need to work somewhere else,” he wrote.

“If a worker refuses an assignment, changed office, earlier start time, or other directive, he may be properly fired,” Judge Hughes said. “Every employment includes limits on the worker’s behavior in exchange for his remuneration. This is all part of the bargain.”

The ruling could set a precedent for similar COVID-19 vaccine lawsuits across the country, NPR reported. Houston Methodist was one of the first hospitals to require staff to be vaccinated. After the ruling on June 12, the hospital system wrote in a statement that it was “pleased and reassured” that Judge Hughes dismissed a “frivolous lawsuit.”

The hospital system will begin to terminate the 178 employees who were suspended if they don’t get a vaccine by June 21.

Jennifer Bridges, a nurse who has led the campaign against the vaccine policy, said she and the other plaintiffs will appeal the decision, according to KHOU.

“We’re OK with this decision. We are appealing. This will be taken all the way to the Supreme Court,” she told the news station. “This is far from over. This is literally only the beginning.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A federal judge in Texas has dismissed a lawsuit from 117 Houston Methodist Hospital workers who refused to get a COVID-19 vaccine and said it was illegal to require them to do so.

In the ruling issued June 12, U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes upheld the hospital’s policy and said the vaccination requirement didn’t break any federal laws.

“This is not coercion,” Judge Hughes wrote in the ruling.

“Methodist is trying to do their business of saving lives without giving them the COVID-19 virus,” he wrote. “It is a choice made to keep staff, patients, and their families safer.”

In April, the Houston Methodist Hospital system announced a policy that required employees to be vaccinated by June 7 or request an exemption. After the deadline, 178 of 26,000 employees refused to get inoculated and were placed on suspension without pay. The employees said the vaccine was unsafe and “experimental.” In his ruling, Judge Hughes said their claim was false and irrelevant.

“Texas law only protects employees from being terminated for refusing to commit an act carrying criminal penalties to the worker,” he wrote. “Receiving a COVID-19 vaccination is not an illegal act, and it carries no criminal penalties.”

He denounced the “press-release style of the complaint” and the comparison of the hospital’s vaccine policy to forced experimentation by the Nazis against Jewish people during the Holocaust.

“Equating the injection requirement to medical experimentation in concentration camps is reprehensible,” he wrote. “Nazi doctors conducted medical experiments on victims that caused pain, mutilation, permanent disability, and in many cases, death.”

Judge Hughes also said that employees can “freely choose” to accept or refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. If they refuse, they “simply need to work somewhere else,” he wrote.

“If a worker refuses an assignment, changed office, earlier start time, or other directive, he may be properly fired,” Judge Hughes said. “Every employment includes limits on the worker’s behavior in exchange for his remuneration. This is all part of the bargain.”

The ruling could set a precedent for similar COVID-19 vaccine lawsuits across the country, NPR reported. Houston Methodist was one of the first hospitals to require staff to be vaccinated. After the ruling on June 12, the hospital system wrote in a statement that it was “pleased and reassured” that Judge Hughes dismissed a “frivolous lawsuit.”

The hospital system will begin to terminate the 178 employees who were suspended if they don’t get a vaccine by June 21.

Jennifer Bridges, a nurse who has led the campaign against the vaccine policy, said she and the other plaintiffs will appeal the decision, according to KHOU.

“We’re OK with this decision. We are appealing. This will be taken all the way to the Supreme Court,” she told the news station. “This is far from over. This is literally only the beginning.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

OSHA issues new rules on COVID-19 safety for health care workers

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration issued its long-awaited Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) for COVID-19 June 10, surprising many by including only health care workers in the new emergency workplace safety rules.

“The ETS is an overdue step toward protecting health care workers, especially those working in long-term care facilities and home health care who are at greatly increased risk of infection,” said George Washington University, Washington, professor and former Obama administration Assistant Secretary of Labor David Michaels, PhD, MPH. “OSHA’s failure to issue a COVID-specific standard in other high-risk industries, like meat and poultry processing, corrections, homeless shelters, and retail establishments is disappointing. If exposure is not controlled in these workplaces, they will continue to be important drivers of infections.”

With the new regulations in place, about 10.3 million health care workers at hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities, as well as emergency responders and home health care workers, should be guaranteed protection standards that replace former guidance.

The new protections include supplying personal protective equipment and ensuring proper usage (for example, mandatory seal checks on respirators); screening everyone who enters the facility for COVID-19; ensuring proper ventilation; and establishing physical distancing requirements (6 feet) for unvaccinated workers. It also requires employers to give workers time off for vaccination. An antiretaliation clause could shield workers who complain about unsafe conditions.

“The science tells us that health care workers, particularly those who come into regular contact with the virus, are most at risk at this point in the pandemic,” Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said on a press call. “So following an extensive review of the science and data, OSHA determined that a health care–specific safety requirement will make the biggest impact.”

But questions remain, said James Brudney, JD, a professor at Fordham Law School in New York and former chief counsel of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor. The standard doesn’t amplify or address existing rules regarding a right to refuse unsafe work, for example, so employees may still feel they are risking their jobs to complain, despite the antiretaliation clause.

And although vaccinated employees don’t have to adhere to the same distancing and masking standards in many instances, the standard doesn’t spell out how employers should determine their workers’ vaccination status – instead leaving that determination to employers through their own policies and procedures. (California’s state OSHA office rules specify the mechanism for documentation of vaccination.)

The Trump administration did not issue an ETS, saying OSHA’s general duty clause sufficed. President Joe Biden took the opposite approach, calling for an investigation into an ETS on his first day in office. But the process took months longer than promised.

“I know it’s been a long time coming,” Mr. Walsh acknowledged. “Our health care workers from the very beginning have been put at risk.

While health care unions had asked for mandated safety standards sooner, National Nurses United, the country’s largest labor union for registered nurses, still welcomed the rules.

“An ETS is a major step toward requiring accountability for hospitals who consistently put their budget goals and profits over our health and safety,” Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, RN, one of NNU’s three presidents, said in a statement June 9 anticipating the publication of the rules.

The rules do not apply to retail pharmacies, ambulatory care settings that screen nonemployees for COVID-19, or certain other settings in which all employees are vaccinated and people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cannot enter.

The agency said it will work with states that have already issued local regulations, including two states that issued temporary standards of their own, Virginia and California.

Employers will have 2 weeks to comply with most of the regulations after they’re published in the Federal Register. The standards will expire in 6 months but could then become permanent, as Virginia’s did in January.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration issued its long-awaited Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) for COVID-19 June 10, surprising many by including only health care workers in the new emergency workplace safety rules.

“The ETS is an overdue step toward protecting health care workers, especially those working in long-term care facilities and home health care who are at greatly increased risk of infection,” said George Washington University, Washington, professor and former Obama administration Assistant Secretary of Labor David Michaels, PhD, MPH. “OSHA’s failure to issue a COVID-specific standard in other high-risk industries, like meat and poultry processing, corrections, homeless shelters, and retail establishments is disappointing. If exposure is not controlled in these workplaces, they will continue to be important drivers of infections.”

With the new regulations in place, about 10.3 million health care workers at hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities, as well as emergency responders and home health care workers, should be guaranteed protection standards that replace former guidance.

The new protections include supplying personal protective equipment and ensuring proper usage (for example, mandatory seal checks on respirators); screening everyone who enters the facility for COVID-19; ensuring proper ventilation; and establishing physical distancing requirements (6 feet) for unvaccinated workers. It also requires employers to give workers time off for vaccination. An antiretaliation clause could shield workers who complain about unsafe conditions.

“The science tells us that health care workers, particularly those who come into regular contact with the virus, are most at risk at this point in the pandemic,” Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said on a press call. “So following an extensive review of the science and data, OSHA determined that a health care–specific safety requirement will make the biggest impact.”

But questions remain, said James Brudney, JD, a professor at Fordham Law School in New York and former chief counsel of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor. The standard doesn’t amplify or address existing rules regarding a right to refuse unsafe work, for example, so employees may still feel they are risking their jobs to complain, despite the antiretaliation clause.

And although vaccinated employees don’t have to adhere to the same distancing and masking standards in many instances, the standard doesn’t spell out how employers should determine their workers’ vaccination status – instead leaving that determination to employers through their own policies and procedures. (California’s state OSHA office rules specify the mechanism for documentation of vaccination.)

The Trump administration did not issue an ETS, saying OSHA’s general duty clause sufficed. President Joe Biden took the opposite approach, calling for an investigation into an ETS on his first day in office. But the process took months longer than promised.

“I know it’s been a long time coming,” Mr. Walsh acknowledged. “Our health care workers from the very beginning have been put at risk.

While health care unions had asked for mandated safety standards sooner, National Nurses United, the country’s largest labor union for registered nurses, still welcomed the rules.

“An ETS is a major step toward requiring accountability for hospitals who consistently put their budget goals and profits over our health and safety,” Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, RN, one of NNU’s three presidents, said in a statement June 9 anticipating the publication of the rules.

The rules do not apply to retail pharmacies, ambulatory care settings that screen nonemployees for COVID-19, or certain other settings in which all employees are vaccinated and people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cannot enter.

The agency said it will work with states that have already issued local regulations, including two states that issued temporary standards of their own, Virginia and California.

Employers will have 2 weeks to comply with most of the regulations after they’re published in the Federal Register. The standards will expire in 6 months but could then become permanent, as Virginia’s did in January.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration issued its long-awaited Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) for COVID-19 June 10, surprising many by including only health care workers in the new emergency workplace safety rules.

“The ETS is an overdue step toward protecting health care workers, especially those working in long-term care facilities and home health care who are at greatly increased risk of infection,” said George Washington University, Washington, professor and former Obama administration Assistant Secretary of Labor David Michaels, PhD, MPH. “OSHA’s failure to issue a COVID-specific standard in other high-risk industries, like meat and poultry processing, corrections, homeless shelters, and retail establishments is disappointing. If exposure is not controlled in these workplaces, they will continue to be important drivers of infections.”

With the new regulations in place, about 10.3 million health care workers at hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities, as well as emergency responders and home health care workers, should be guaranteed protection standards that replace former guidance.

The new protections include supplying personal protective equipment and ensuring proper usage (for example, mandatory seal checks on respirators); screening everyone who enters the facility for COVID-19; ensuring proper ventilation; and establishing physical distancing requirements (6 feet) for unvaccinated workers. It also requires employers to give workers time off for vaccination. An antiretaliation clause could shield workers who complain about unsafe conditions.

“The science tells us that health care workers, particularly those who come into regular contact with the virus, are most at risk at this point in the pandemic,” Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said on a press call. “So following an extensive review of the science and data, OSHA determined that a health care–specific safety requirement will make the biggest impact.”

But questions remain, said James Brudney, JD, a professor at Fordham Law School in New York and former chief counsel of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor. The standard doesn’t amplify or address existing rules regarding a right to refuse unsafe work, for example, so employees may still feel they are risking their jobs to complain, despite the antiretaliation clause.

And although vaccinated employees don’t have to adhere to the same distancing and masking standards in many instances, the standard doesn’t spell out how employers should determine their workers’ vaccination status – instead leaving that determination to employers through their own policies and procedures. (California’s state OSHA office rules specify the mechanism for documentation of vaccination.)

The Trump administration did not issue an ETS, saying OSHA’s general duty clause sufficed. President Joe Biden took the opposite approach, calling for an investigation into an ETS on his first day in office. But the process took months longer than promised.

“I know it’s been a long time coming,” Mr. Walsh acknowledged. “Our health care workers from the very beginning have been put at risk.

While health care unions had asked for mandated safety standards sooner, National Nurses United, the country’s largest labor union for registered nurses, still welcomed the rules.

“An ETS is a major step toward requiring accountability for hospitals who consistently put their budget goals and profits over our health and safety,” Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, RN, one of NNU’s three presidents, said in a statement June 9 anticipating the publication of the rules.

The rules do not apply to retail pharmacies, ambulatory care settings that screen nonemployees for COVID-19, or certain other settings in which all employees are vaccinated and people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cannot enter.

The agency said it will work with states that have already issued local regulations, including two states that issued temporary standards of their own, Virginia and California.

Employers will have 2 weeks to comply with most of the regulations after they’re published in the Federal Register. The standards will expire in 6 months but could then become permanent, as Virginia’s did in January.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 death toll higher for international medical graduates

researchers report.

“I’ve always felt that international medical graduates [IMGs] in America are largely invisible,” said senior author Abraham Verghese, MD, MFA, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Everyone is aware that there are foreign doctors, but very few are aware of how many there are and also how vital they are to providing health care in America.”

IMGs made up 25% of all U.S. physicians in 2020 but accounted for 45% of those whose deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 through Nov. 23, 2020, Deendayal Dinakarpandian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues report in JAMA Network Open.

IMGs are more likely to work in places where the incidence of COVID-19 is high and in facilities with fewer resources, Dr. Verghese said in an interview. “So, it’s not surprising that they were on the front lines when this thing came along,” he said.

To see whether their vulnerability affected their risk for death, Dr. Dinakarpandian and colleagues collected data from Nov. 23, 2020, from three sources of information regarding deaths among physicians: MedPage Today, which used investigative and voluntary reporting; Medscape, which used voluntary reporting of verifiable information; and a collaboration of The Guardian and Kaiser Health News, which used investigative reporting.

The Medscape project was launched on April 1, 2020. The MedPage Today and The Guardian/Kaiser Health News projects were launched on April 8, 2020.

Dr. Verghese and colleagues researched obituaries and news articles referenced by the three projects to verify their data. They used DocInfo to ascertain the deceased physicians’ medical schools.

After eliminating duplications from the lists, the researchers counted 132 physician deaths in 28 states. Of these, 59 physicians had graduated from medical schools outside the United States, a death toll 1.8 times higher than the proportion of IMGs among U.S. physicians (95% confidence interval, 1.52-2.21; P < .001).

New York, New Jersey, and Florida accounted for 66% of the deaths among IMGs but for only 45% of the deaths among U.S. medical school graduates.

Within each state, the proportion of IMGs among deceased physicians was not statistically different from their proportion among physicians in those states, with the exception of New York.

Two-thirds of the physicians’ deaths occurred in states where IMGs make up a larger proportion of physicians than in the nation as a whole. In these states, the incidence of COVID-19 was high at the start of the pandemic.

In New York, IMGs accounted for 60% of physician deaths, which was 1.62 times higher (95% CI, 1.26-2.09; P = .005) than the 37% among New York physicians overall.

Physicians who were trained abroad frequently can’t get into the most prestigious residency programs or into the highest paid specialties and are more likely to serve in primary care, Dr. Verghese said. Overall, 60% of the physicians who died of COVID-19 worked in primary care.

IMGs often staff hospitals serving low-income communities and communities of color, which were hardest hit by the pandemic and where personal protective equipment was hard to obtain, said Dr. Verghese.

In addition to these risks, IMGs sometimes endure racism, said Dr. Verghese, who obtained his medical degree at Madras Medical College, Chennai, India. “We’ve actually seen in the COVID era, in keeping with the sort of political tone that was set in Washington, that there’s been a lot more abuses of both foreign physicians and foreign looking physicians – even if they’re not foreign trained – and nurses by patients who have been given license. And I want to acknowledge the heroism of all these physicians.”

The study was partially funded by the Presence Center at Stanford. Dr. Verghese is a regular contributor to Medscape. He served on the advisory board for Gilead Sciences, serves as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Leigh Bureau, and receives royalties from Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers report.

“I’ve always felt that international medical graduates [IMGs] in America are largely invisible,” said senior author Abraham Verghese, MD, MFA, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Everyone is aware that there are foreign doctors, but very few are aware of how many there are and also how vital they are to providing health care in America.”

IMGs made up 25% of all U.S. physicians in 2020 but accounted for 45% of those whose deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 through Nov. 23, 2020, Deendayal Dinakarpandian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues report in JAMA Network Open.

IMGs are more likely to work in places where the incidence of COVID-19 is high and in facilities with fewer resources, Dr. Verghese said in an interview. “So, it’s not surprising that they were on the front lines when this thing came along,” he said.

To see whether their vulnerability affected their risk for death, Dr. Dinakarpandian and colleagues collected data from Nov. 23, 2020, from three sources of information regarding deaths among physicians: MedPage Today, which used investigative and voluntary reporting; Medscape, which used voluntary reporting of verifiable information; and a collaboration of The Guardian and Kaiser Health News, which used investigative reporting.

The Medscape project was launched on April 1, 2020. The MedPage Today and The Guardian/Kaiser Health News projects were launched on April 8, 2020.

Dr. Verghese and colleagues researched obituaries and news articles referenced by the three projects to verify their data. They used DocInfo to ascertain the deceased physicians’ medical schools.

After eliminating duplications from the lists, the researchers counted 132 physician deaths in 28 states. Of these, 59 physicians had graduated from medical schools outside the United States, a death toll 1.8 times higher than the proportion of IMGs among U.S. physicians (95% confidence interval, 1.52-2.21; P < .001).

New York, New Jersey, and Florida accounted for 66% of the deaths among IMGs but for only 45% of the deaths among U.S. medical school graduates.

Within each state, the proportion of IMGs among deceased physicians was not statistically different from their proportion among physicians in those states, with the exception of New York.

Two-thirds of the physicians’ deaths occurred in states where IMGs make up a larger proportion of physicians than in the nation as a whole. In these states, the incidence of COVID-19 was high at the start of the pandemic.

In New York, IMGs accounted for 60% of physician deaths, which was 1.62 times higher (95% CI, 1.26-2.09; P = .005) than the 37% among New York physicians overall.

Physicians who were trained abroad frequently can’t get into the most prestigious residency programs or into the highest paid specialties and are more likely to serve in primary care, Dr. Verghese said. Overall, 60% of the physicians who died of COVID-19 worked in primary care.

IMGs often staff hospitals serving low-income communities and communities of color, which were hardest hit by the pandemic and where personal protective equipment was hard to obtain, said Dr. Verghese.

In addition to these risks, IMGs sometimes endure racism, said Dr. Verghese, who obtained his medical degree at Madras Medical College, Chennai, India. “We’ve actually seen in the COVID era, in keeping with the sort of political tone that was set in Washington, that there’s been a lot more abuses of both foreign physicians and foreign looking physicians – even if they’re not foreign trained – and nurses by patients who have been given license. And I want to acknowledge the heroism of all these physicians.”

The study was partially funded by the Presence Center at Stanford. Dr. Verghese is a regular contributor to Medscape. He served on the advisory board for Gilead Sciences, serves as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Leigh Bureau, and receives royalties from Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers report.

“I’ve always felt that international medical graduates [IMGs] in America are largely invisible,” said senior author Abraham Verghese, MD, MFA, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Everyone is aware that there are foreign doctors, but very few are aware of how many there are and also how vital they are to providing health care in America.”

IMGs made up 25% of all U.S. physicians in 2020 but accounted for 45% of those whose deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 through Nov. 23, 2020, Deendayal Dinakarpandian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues report in JAMA Network Open.

IMGs are more likely to work in places where the incidence of COVID-19 is high and in facilities with fewer resources, Dr. Verghese said in an interview. “So, it’s not surprising that they were on the front lines when this thing came along,” he said.