User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

New guidance on management of acute CVD during COVID-19

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA issues EUA allowing hydroxychloroquine sulfate, chloroquine phosphate treatment in COVID-19

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

Are psychiatrists more prepared for COVID-19 than we think?

Helping patients navigate surreal situations is what we do

A meme has been going around the Internet in which a Muppet is dressed as a doctor, and the caption declares: “If you don’t want to be intubated by a psychiatrist, stay home!” This meme is meant as a commentary on health care worker shortages. But it also touches on the concerns of psychiatrists who might be questioning our role in the pandemic, given that we are physicians who do not regularly rely on labs or imaging to guide treatment. And we rarely even touch our patients.

As observed by Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, editor in chief of Current Psychiatry, who referred to anxiety as endemic during a viral pandemic (Current Psychiatry. 2020 April;19[4]:e3-5), our society is experiencing intense psychological repercussions from the pandemic. These repercussions will evolve from anxiety to despair, and for some, to resilience.

All jokes aside about the medical knowledge of psychiatrists, we are on the cutting edge of how to address the pandemic of fear and uncertainty gripping individuals and society across the nation.

Isn’t it our role as psychiatrists to help people face the reality of personal and societal crises? Aren’t we trained to help people find their internal reserves, bolster them with medications and/or psychotherapy, and prepare them to respond to challenges? I propose that our training and particular experience of hearing patients’ stories has indeed prepared us to receive surreal information and package it into a palatable, even therapeutic, form for our patients.

I’d like to present two cases I’ve recently seen during the first stages of the COVID-19 pandemic juxtaposed with patients I saw during “normal” times. These cases show that, as psychiatrists, we are prepared to face the psychological impact of this crisis.

A patient called me about worsened anxiety after she’d been sidelined at home from her job as a waitress and was currently spending 12 hours a day with her overbearing mother. She had always used her work to buffer her anxiety, as the fast pace of the restaurant kept her from ruminating.

The call reminded me of ones I’d receive from female patients during the MeToo movement and particularly during the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court, in which a sexual assault victim and alleged perpetrator faced off on television. During therapy and medication management sessions alike, I would talk to women struggling with the number of news stories about victims coming forward after sexual assault. They were reliving their humiliations, and despite the empowering nature of the movement, they felt vulnerable in the shadow of memories of their perpetrators.

The advice I gave then is similar to the guidance I give now, and also is closely related to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice on its website on how to manage the mental health impact of COVID-19. People can be informed without suffering by taking these steps:

- Limit the amount of news and social media consumed, and if possible, try to schedule news consumption into discrete periods that are not close to bedtime or other periods meant for relaxation.

- Reach out to loved ones and friends who remind you of strength and better times.

- Make time to relax and unwind, either through resting or engaging in an activity you enjoy.

- Take care of your body and mind with exercise.

- Try for 8 hours of sleep a night (even if it doesn’t happen).

- Use techniques such as meditating, doing yoga, or breathing to practice focusing your attention somewhere.

All of our lives have been disrupted by COVID-19 and acknowledging this to patients can help them feel less isolated and vulnerable. Our patients with diagnosed psychiatric disorders will be more susceptible to crippling anxiety, exacerbations in panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, and resurgence of suicidal ideation in the face of uncertainty and despair. They may also be more likely to experience the socioeconomic fallout of this pandemic. But it’s not just these individuals who will be hit with intense feelings as we wonder what the next day, month, or 6 months hold for us, our families, our friends, our country, and our world.

Recently, I had one of the more surreal experiences of my professional life. I work as a consulation-liaison psychiatrist on the medical wards, and I was consulted to treat a young woman from Central America with schizophrenia who made a serious suicide attempt in mid-February before COVID-19 was part of the lexicon.

After an overdose, she developed aspiration pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome and ended up in the ICU on a respirator for 3 weeks. Her doctors and family were certain she would die, but she miraculously survived. By the time she was extubated and less delirious from her medically induced coma, the hospital had restricted all visitors because of COVID-19.

Because I speak Spanish, we developed as decent a working relationship as we could, considering the patient’s delirium and blunted affect. On top of restarting her antipsychotics, I had to inform her that her family was no longer allowed to come visit her. Outside of this room, I vacillated on how to tell a woman with a history of paranoia that the hospital would not allow her family to visit because we were in the middle of a pandemic. A contagious virus had quickly spread around the world, cases were now spiking in the United States, much of the country was on lockdown, and the hospital was limiting visitors because asymptomatic individuals could bring the virus into the hospital or be infected by asymptomatic staff.

As the words came out of my mouth, she looked at me as I have looked at psychotic individuals as they spin me yarns of impossible explanation for their symptoms when I know they’re simply psychotic and living in an alternate reality. Imagine just waking up from a coma and your doctor coming in to tell you: “The U.S. is on lockdown because a deadly virus is spreading throughout our country.” You’d think you’ve woken up in a zombie film. Yet, the patient simply nodded and asked: “Will I be able to use the phone to call my family?” I sighed with relief and helped her dial her brother’s number.

Haven’t we all listened to insane stories while keeping a straight face and then answered with a politely bland question? Just a few months ago, I treated a homeless woman with schizophrenia who calmly explained to me that her large malignant ovarian tumor (which I could see protruding under her gown) was the unborn heir of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. If she allowed the doctors to take it out (that is, treat her cancer) she’d be assassinated by the Russian intelligence agency. She refused to let the doctors sentence her to death. Ultimately, we allowed her to refuse treatment. Despite a month of treatment with antipsychotic medication, her psychotic beliefs did not change, and we could not imagine forcing her through surgery and chemotherapy. She died in hospice.

I’ve walked the valleys of bizarro land many times. Working through the dark reality of COVID-19 should be no match for us psychiatrists who have listened to dark stories and responded with words of comfort or empathic silence. As mental health clinicians, I believe we are well equipped to fight on the front lines of the pandemic of fear that has arrested our country. We can make ourselves available to our patients, friends, family, and institutions – medical or otherwise – that are grappling with how to cope with the psychological impact of COVID-19.

Dr. Posada is a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow with the Inova Fairfax Hospital/George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and associate producer of the MDedge Psychcast. She changed key details about the patients discussed to protect their confidentiality. Dr. Posada has no conflicts of interest.

Helping patients navigate surreal situations is what we do

Helping patients navigate surreal situations is what we do

A meme has been going around the Internet in which a Muppet is dressed as a doctor, and the caption declares: “If you don’t want to be intubated by a psychiatrist, stay home!” This meme is meant as a commentary on health care worker shortages. But it also touches on the concerns of psychiatrists who might be questioning our role in the pandemic, given that we are physicians who do not regularly rely on labs or imaging to guide treatment. And we rarely even touch our patients.

As observed by Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, editor in chief of Current Psychiatry, who referred to anxiety as endemic during a viral pandemic (Current Psychiatry. 2020 April;19[4]:e3-5), our society is experiencing intense psychological repercussions from the pandemic. These repercussions will evolve from anxiety to despair, and for some, to resilience.

All jokes aside about the medical knowledge of psychiatrists, we are on the cutting edge of how to address the pandemic of fear and uncertainty gripping individuals and society across the nation.

Isn’t it our role as psychiatrists to help people face the reality of personal and societal crises? Aren’t we trained to help people find their internal reserves, bolster them with medications and/or psychotherapy, and prepare them to respond to challenges? I propose that our training and particular experience of hearing patients’ stories has indeed prepared us to receive surreal information and package it into a palatable, even therapeutic, form for our patients.

I’d like to present two cases I’ve recently seen during the first stages of the COVID-19 pandemic juxtaposed with patients I saw during “normal” times. These cases show that, as psychiatrists, we are prepared to face the psychological impact of this crisis.

A patient called me about worsened anxiety after she’d been sidelined at home from her job as a waitress and was currently spending 12 hours a day with her overbearing mother. She had always used her work to buffer her anxiety, as the fast pace of the restaurant kept her from ruminating.

The call reminded me of ones I’d receive from female patients during the MeToo movement and particularly during the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court, in which a sexual assault victim and alleged perpetrator faced off on television. During therapy and medication management sessions alike, I would talk to women struggling with the number of news stories about victims coming forward after sexual assault. They were reliving their humiliations, and despite the empowering nature of the movement, they felt vulnerable in the shadow of memories of their perpetrators.

The advice I gave then is similar to the guidance I give now, and also is closely related to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice on its website on how to manage the mental health impact of COVID-19. People can be informed without suffering by taking these steps:

- Limit the amount of news and social media consumed, and if possible, try to schedule news consumption into discrete periods that are not close to bedtime or other periods meant for relaxation.

- Reach out to loved ones and friends who remind you of strength and better times.

- Make time to relax and unwind, either through resting or engaging in an activity you enjoy.

- Take care of your body and mind with exercise.

- Try for 8 hours of sleep a night (even if it doesn’t happen).

- Use techniques such as meditating, doing yoga, or breathing to practice focusing your attention somewhere.

All of our lives have been disrupted by COVID-19 and acknowledging this to patients can help them feel less isolated and vulnerable. Our patients with diagnosed psychiatric disorders will be more susceptible to crippling anxiety, exacerbations in panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, and resurgence of suicidal ideation in the face of uncertainty and despair. They may also be more likely to experience the socioeconomic fallout of this pandemic. But it’s not just these individuals who will be hit with intense feelings as we wonder what the next day, month, or 6 months hold for us, our families, our friends, our country, and our world.

Recently, I had one of the more surreal experiences of my professional life. I work as a consulation-liaison psychiatrist on the medical wards, and I was consulted to treat a young woman from Central America with schizophrenia who made a serious suicide attempt in mid-February before COVID-19 was part of the lexicon.

After an overdose, she developed aspiration pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome and ended up in the ICU on a respirator for 3 weeks. Her doctors and family were certain she would die, but she miraculously survived. By the time she was extubated and less delirious from her medically induced coma, the hospital had restricted all visitors because of COVID-19.

Because I speak Spanish, we developed as decent a working relationship as we could, considering the patient’s delirium and blunted affect. On top of restarting her antipsychotics, I had to inform her that her family was no longer allowed to come visit her. Outside of this room, I vacillated on how to tell a woman with a history of paranoia that the hospital would not allow her family to visit because we were in the middle of a pandemic. A contagious virus had quickly spread around the world, cases were now spiking in the United States, much of the country was on lockdown, and the hospital was limiting visitors because asymptomatic individuals could bring the virus into the hospital or be infected by asymptomatic staff.

As the words came out of my mouth, she looked at me as I have looked at psychotic individuals as they spin me yarns of impossible explanation for their symptoms when I know they’re simply psychotic and living in an alternate reality. Imagine just waking up from a coma and your doctor coming in to tell you: “The U.S. is on lockdown because a deadly virus is spreading throughout our country.” You’d think you’ve woken up in a zombie film. Yet, the patient simply nodded and asked: “Will I be able to use the phone to call my family?” I sighed with relief and helped her dial her brother’s number.

Haven’t we all listened to insane stories while keeping a straight face and then answered with a politely bland question? Just a few months ago, I treated a homeless woman with schizophrenia who calmly explained to me that her large malignant ovarian tumor (which I could see protruding under her gown) was the unborn heir of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. If she allowed the doctors to take it out (that is, treat her cancer) she’d be assassinated by the Russian intelligence agency. She refused to let the doctors sentence her to death. Ultimately, we allowed her to refuse treatment. Despite a month of treatment with antipsychotic medication, her psychotic beliefs did not change, and we could not imagine forcing her through surgery and chemotherapy. She died in hospice.

I’ve walked the valleys of bizarro land many times. Working through the dark reality of COVID-19 should be no match for us psychiatrists who have listened to dark stories and responded with words of comfort or empathic silence. As mental health clinicians, I believe we are well equipped to fight on the front lines of the pandemic of fear that has arrested our country. We can make ourselves available to our patients, friends, family, and institutions – medical or otherwise – that are grappling with how to cope with the psychological impact of COVID-19.

Dr. Posada is a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow with the Inova Fairfax Hospital/George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and associate producer of the MDedge Psychcast. She changed key details about the patients discussed to protect their confidentiality. Dr. Posada has no conflicts of interest.

A meme has been going around the Internet in which a Muppet is dressed as a doctor, and the caption declares: “If you don’t want to be intubated by a psychiatrist, stay home!” This meme is meant as a commentary on health care worker shortages. But it also touches on the concerns of psychiatrists who might be questioning our role in the pandemic, given that we are physicians who do not regularly rely on labs or imaging to guide treatment. And we rarely even touch our patients.

As observed by Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, editor in chief of Current Psychiatry, who referred to anxiety as endemic during a viral pandemic (Current Psychiatry. 2020 April;19[4]:e3-5), our society is experiencing intense psychological repercussions from the pandemic. These repercussions will evolve from anxiety to despair, and for some, to resilience.

All jokes aside about the medical knowledge of psychiatrists, we are on the cutting edge of how to address the pandemic of fear and uncertainty gripping individuals and society across the nation.

Isn’t it our role as psychiatrists to help people face the reality of personal and societal crises? Aren’t we trained to help people find their internal reserves, bolster them with medications and/or psychotherapy, and prepare them to respond to challenges? I propose that our training and particular experience of hearing patients’ stories has indeed prepared us to receive surreal information and package it into a palatable, even therapeutic, form for our patients.

I’d like to present two cases I’ve recently seen during the first stages of the COVID-19 pandemic juxtaposed with patients I saw during “normal” times. These cases show that, as psychiatrists, we are prepared to face the psychological impact of this crisis.

A patient called me about worsened anxiety after she’d been sidelined at home from her job as a waitress and was currently spending 12 hours a day with her overbearing mother. She had always used her work to buffer her anxiety, as the fast pace of the restaurant kept her from ruminating.

The call reminded me of ones I’d receive from female patients during the MeToo movement and particularly during the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court, in which a sexual assault victim and alleged perpetrator faced off on television. During therapy and medication management sessions alike, I would talk to women struggling with the number of news stories about victims coming forward after sexual assault. They were reliving their humiliations, and despite the empowering nature of the movement, they felt vulnerable in the shadow of memories of their perpetrators.

The advice I gave then is similar to the guidance I give now, and also is closely related to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice on its website on how to manage the mental health impact of COVID-19. People can be informed without suffering by taking these steps:

- Limit the amount of news and social media consumed, and if possible, try to schedule news consumption into discrete periods that are not close to bedtime or other periods meant for relaxation.

- Reach out to loved ones and friends who remind you of strength and better times.

- Make time to relax and unwind, either through resting or engaging in an activity you enjoy.

- Take care of your body and mind with exercise.

- Try for 8 hours of sleep a night (even if it doesn’t happen).

- Use techniques such as meditating, doing yoga, or breathing to practice focusing your attention somewhere.

All of our lives have been disrupted by COVID-19 and acknowledging this to patients can help them feel less isolated and vulnerable. Our patients with diagnosed psychiatric disorders will be more susceptible to crippling anxiety, exacerbations in panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, and resurgence of suicidal ideation in the face of uncertainty and despair. They may also be more likely to experience the socioeconomic fallout of this pandemic. But it’s not just these individuals who will be hit with intense feelings as we wonder what the next day, month, or 6 months hold for us, our families, our friends, our country, and our world.

Recently, I had one of the more surreal experiences of my professional life. I work as a consulation-liaison psychiatrist on the medical wards, and I was consulted to treat a young woman from Central America with schizophrenia who made a serious suicide attempt in mid-February before COVID-19 was part of the lexicon.

After an overdose, she developed aspiration pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome and ended up in the ICU on a respirator for 3 weeks. Her doctors and family were certain she would die, but she miraculously survived. By the time she was extubated and less delirious from her medically induced coma, the hospital had restricted all visitors because of COVID-19.

Because I speak Spanish, we developed as decent a working relationship as we could, considering the patient’s delirium and blunted affect. On top of restarting her antipsychotics, I had to inform her that her family was no longer allowed to come visit her. Outside of this room, I vacillated on how to tell a woman with a history of paranoia that the hospital would not allow her family to visit because we were in the middle of a pandemic. A contagious virus had quickly spread around the world, cases were now spiking in the United States, much of the country was on lockdown, and the hospital was limiting visitors because asymptomatic individuals could bring the virus into the hospital or be infected by asymptomatic staff.

As the words came out of my mouth, she looked at me as I have looked at psychotic individuals as they spin me yarns of impossible explanation for their symptoms when I know they’re simply psychotic and living in an alternate reality. Imagine just waking up from a coma and your doctor coming in to tell you: “The U.S. is on lockdown because a deadly virus is spreading throughout our country.” You’d think you’ve woken up in a zombie film. Yet, the patient simply nodded and asked: “Will I be able to use the phone to call my family?” I sighed with relief and helped her dial her brother’s number.

Haven’t we all listened to insane stories while keeping a straight face and then answered with a politely bland question? Just a few months ago, I treated a homeless woman with schizophrenia who calmly explained to me that her large malignant ovarian tumor (which I could see protruding under her gown) was the unborn heir of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. If she allowed the doctors to take it out (that is, treat her cancer) she’d be assassinated by the Russian intelligence agency. She refused to let the doctors sentence her to death. Ultimately, we allowed her to refuse treatment. Despite a month of treatment with antipsychotic medication, her psychotic beliefs did not change, and we could not imagine forcing her through surgery and chemotherapy. She died in hospice.

I’ve walked the valleys of bizarro land many times. Working through the dark reality of COVID-19 should be no match for us psychiatrists who have listened to dark stories and responded with words of comfort or empathic silence. As mental health clinicians, I believe we are well equipped to fight on the front lines of the pandemic of fear that has arrested our country. We can make ourselves available to our patients, friends, family, and institutions – medical or otherwise – that are grappling with how to cope with the psychological impact of COVID-19.

Dr. Posada is a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow with the Inova Fairfax Hospital/George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and associate producer of the MDedge Psychcast. She changed key details about the patients discussed to protect their confidentiality. Dr. Posada has no conflicts of interest.

In the Phoenix area, we are in a lull before the coronavirus storm

“There is no sound save the throb of the blowers and the vibration of the hard-driven engines. There is little motion as the gun crews man their guns and the fire-control details stand with heads bent and their hands clapped over their headphones. Somewhere out there are the enemy planes.”

That’s from one of my favorite WW2 histories, “Torpedo Junction,” by Robert J. Casey. He was a reporter stationed on board the cruiser USS Salt Lake City. The entry is from a day in February 1942 when the ship was part of a force that bombarded the Japanese encampment on Wake Island. The excerpt describes the scene later that afternoon, as they awaited a counterattack from Japanese planes.

For some reason that paragraph kept going through my mind this past Sunday afternoon, in the comparatively mundane situation of sitting in the hospital library signing off on my dictations and reviewing test results. I certainly was in no danger of being bombed or strafed, yet ...

Around me, the hospital was preparing for battle. As I rounded, most of the beds were empty and many of the floors above me were shut down and darkened. Waiting rooms were empty. If you hadn’t read the news you’d think there was a sudden lull in the health care world.

But the real truth is that it’s the calm before an anticipated storm. The elective procedures have all been canceled. Nonurgent outpatient tests are on hold. Only the sickest are being admitted, and they’re being sent out as soon as possible. Every bed possible is being kept open for the feared onslaught of coronavirus patients in the coming weeks. Protective equipment, already in short supply, is being stockpiled as it becomes available. Plans have been made to erect triage tents in the parking lots.

I sit in the library and think of this. It’s quiet except for the soft hum of the air conditioning blowers as Phoenix starts to warm up for another summer. The muted purr of the computer’s hard drive as I click away on the keys. On the floors above me the nurses and respiratory techs and doctors go about their daily business of patient care, wondering when the real battle will begin (probably 2-3 weeks from the time of this writing, if not sooner).

These are scary times. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t frightened about what might happen to me, my family, my friends, my coworkers, my patients.

The people working in the hospital above me are in the same boat, all nervous about what’s going to happen. None of them is any more immune to coronavirus than the people they’ll be treating.

But, like the crew of the USS Salt Lake City, they’re ready to do their jobs. Because it’s part of what drove each of us into our own part of this field. Because we care and want to help. And health care doesn’t work unless the whole team does.

I respect them all for it. I always have and always will, and now more than ever.

Good luck.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

“There is no sound save the throb of the blowers and the vibration of the hard-driven engines. There is little motion as the gun crews man their guns and the fire-control details stand with heads bent and their hands clapped over their headphones. Somewhere out there are the enemy planes.”

That’s from one of my favorite WW2 histories, “Torpedo Junction,” by Robert J. Casey. He was a reporter stationed on board the cruiser USS Salt Lake City. The entry is from a day in February 1942 when the ship was part of a force that bombarded the Japanese encampment on Wake Island. The excerpt describes the scene later that afternoon, as they awaited a counterattack from Japanese planes.

For some reason that paragraph kept going through my mind this past Sunday afternoon, in the comparatively mundane situation of sitting in the hospital library signing off on my dictations and reviewing test results. I certainly was in no danger of being bombed or strafed, yet ...

Around me, the hospital was preparing for battle. As I rounded, most of the beds were empty and many of the floors above me were shut down and darkened. Waiting rooms were empty. If you hadn’t read the news you’d think there was a sudden lull in the health care world.

But the real truth is that it’s the calm before an anticipated storm. The elective procedures have all been canceled. Nonurgent outpatient tests are on hold. Only the sickest are being admitted, and they’re being sent out as soon as possible. Every bed possible is being kept open for the feared onslaught of coronavirus patients in the coming weeks. Protective equipment, already in short supply, is being stockpiled as it becomes available. Plans have been made to erect triage tents in the parking lots.

I sit in the library and think of this. It’s quiet except for the soft hum of the air conditioning blowers as Phoenix starts to warm up for another summer. The muted purr of the computer’s hard drive as I click away on the keys. On the floors above me the nurses and respiratory techs and doctors go about their daily business of patient care, wondering when the real battle will begin (probably 2-3 weeks from the time of this writing, if not sooner).

These are scary times. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t frightened about what might happen to me, my family, my friends, my coworkers, my patients.

The people working in the hospital above me are in the same boat, all nervous about what’s going to happen. None of them is any more immune to coronavirus than the people they’ll be treating.

But, like the crew of the USS Salt Lake City, they’re ready to do their jobs. Because it’s part of what drove each of us into our own part of this field. Because we care and want to help. And health care doesn’t work unless the whole team does.

I respect them all for it. I always have and always will, and now more than ever.

Good luck.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

“There is no sound save the throb of the blowers and the vibration of the hard-driven engines. There is little motion as the gun crews man their guns and the fire-control details stand with heads bent and their hands clapped over their headphones. Somewhere out there are the enemy planes.”

That’s from one of my favorite WW2 histories, “Torpedo Junction,” by Robert J. Casey. He was a reporter stationed on board the cruiser USS Salt Lake City. The entry is from a day in February 1942 when the ship was part of a force that bombarded the Japanese encampment on Wake Island. The excerpt describes the scene later that afternoon, as they awaited a counterattack from Japanese planes.

For some reason that paragraph kept going through my mind this past Sunday afternoon, in the comparatively mundane situation of sitting in the hospital library signing off on my dictations and reviewing test results. I certainly was in no danger of being bombed or strafed, yet ...

Around me, the hospital was preparing for battle. As I rounded, most of the beds were empty and many of the floors above me were shut down and darkened. Waiting rooms were empty. If you hadn’t read the news you’d think there was a sudden lull in the health care world.

But the real truth is that it’s the calm before an anticipated storm. The elective procedures have all been canceled. Nonurgent outpatient tests are on hold. Only the sickest are being admitted, and they’re being sent out as soon as possible. Every bed possible is being kept open for the feared onslaught of coronavirus patients in the coming weeks. Protective equipment, already in short supply, is being stockpiled as it becomes available. Plans have been made to erect triage tents in the parking lots.

I sit in the library and think of this. It’s quiet except for the soft hum of the air conditioning blowers as Phoenix starts to warm up for another summer. The muted purr of the computer’s hard drive as I click away on the keys. On the floors above me the nurses and respiratory techs and doctors go about their daily business of patient care, wondering when the real battle will begin (probably 2-3 weeks from the time of this writing, if not sooner).

These are scary times. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t frightened about what might happen to me, my family, my friends, my coworkers, my patients.

The people working in the hospital above me are in the same boat, all nervous about what’s going to happen. None of them is any more immune to coronavirus than the people they’ll be treating.

But, like the crew of the USS Salt Lake City, they’re ready to do their jobs. Because it’s part of what drove each of us into our own part of this field. Because we care and want to help. And health care doesn’t work unless the whole team does.

I respect them all for it. I always have and always will, and now more than ever.

Good luck.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Physician couples draft wills, face tough questions amid COVID-19

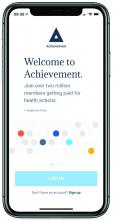

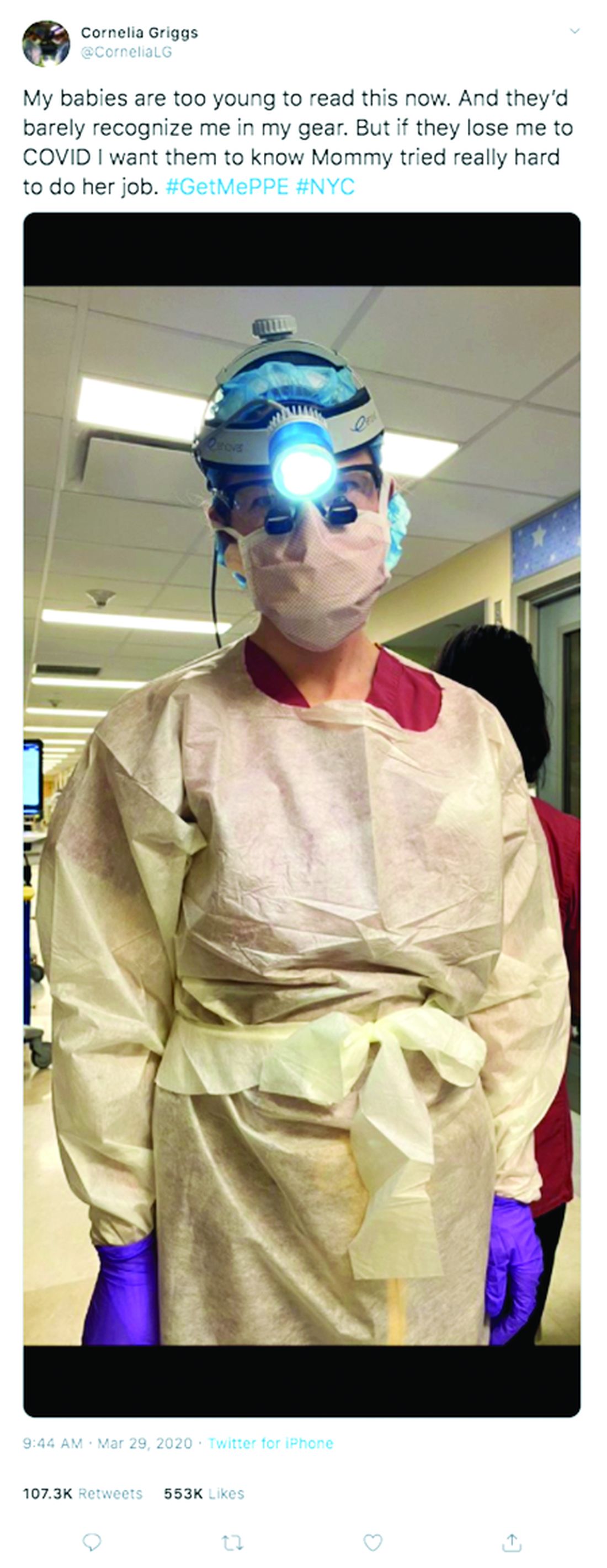

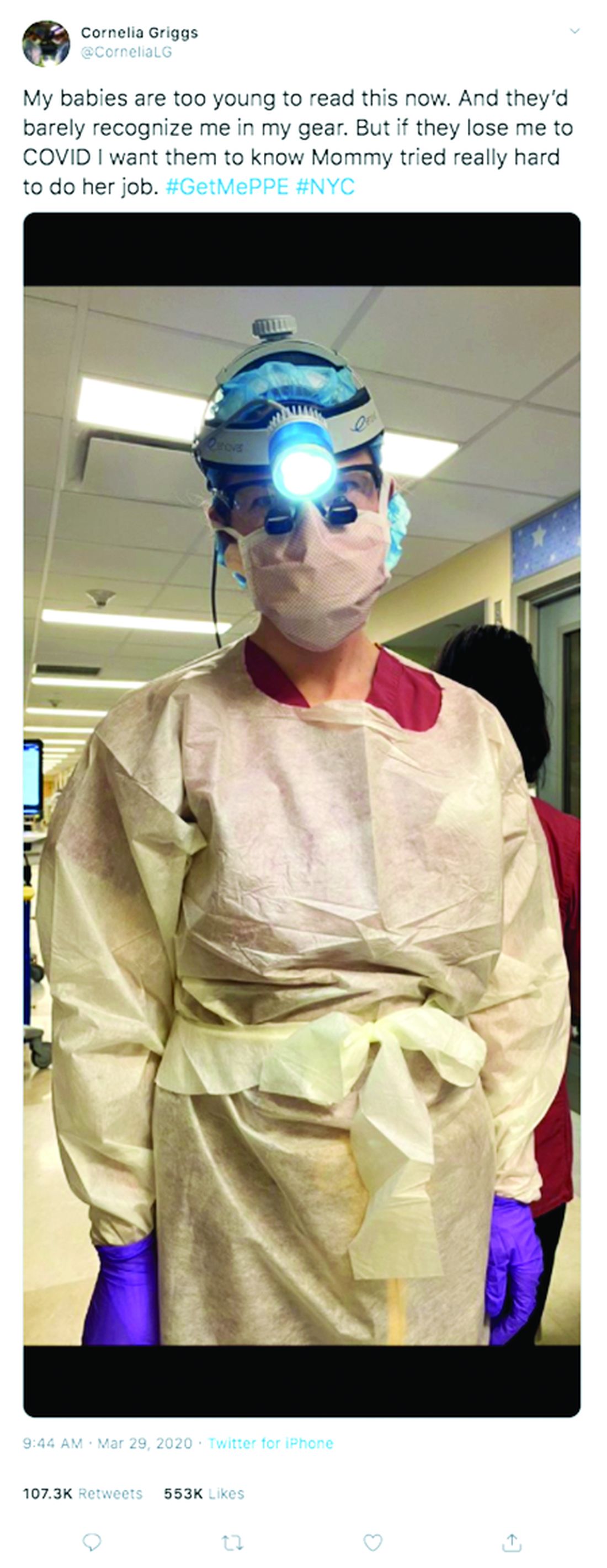

Not long ago, weekends for Cornelia Griggs, MD, meant making trips to the grocery store, chasing after two active toddlers, and eating brunch with her husband after a busy work week. But life has changed dramatically for the family since the spread of COVID-19. On a recent weekend, Dr. Griggs and her husband, Robert Goldstone, MD, spent their days off drafting a will.

“We’re both doctors, and we know that health care workers have an increased risk of contracting COVID,” said Dr. Griggs, a pediatric surgery fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “It felt like the responsible thing to do: Have a will in place to make sure our wishes are clear about who would manage our property and assets, and who would take care of our kids – God forbid.”

Outlining their final wishes is among many difficult decisions the doctors, both 36, have been forced to make in recent weeks. Dr. Goldstone, a general surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is no longer returning to New York during his time off, said Dr. Griggs, who has had known COVID-19 exposures. The couple’s children, aged 4 and almost 2, are temporarily living with their grandparents in Connecticut to decrease their exposure risk.

“I felt like it was safer for all of them to be there while I was going back and forth from the hospital,” Dr. Griggs said. “My husband is in Boston. The kids are in Connecticut and I’m in New York. That inherently is hard because our whole family is split up. I don’t know when it will be safe for me to see them again.”

Health professional couples across the country are facing similar challenges as they navigate the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, while trying to protect their families at home. From childcare dilemmas to quarantine quandaries to end-of-life considerations, partners who work in health care are confronting tough questions as the pandemic continues.

The biggest challenge is the uncertainty, says Angela Weyand, MD, an Ann Arbor, Mich.–based pediatric hematologist/oncologist who shares two young daughters with husband Ted Claflin, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician. Dr. Weyand said she and her husband are primarily working remotely now, but she knows that one or both could be deployed to the hospital to help care for patients, if the need arises. Nearby Detroit has been labeled a coronavirus “hot spot” by the U.S. Surgeon General.

“Right now, I think our biggest fear is spreading coronavirus to those we love, especially those in higher risk groups,” she said. “At the same time, we are also concerned about our own health and our future ability to be there for our children, a fear that, thankfully, neither one of us has ever had to face before. We are trying to take things one day at a time, acknowledging all that we have to be grateful for, and also learning to accept that many things right now are outside of our control.”

Dr. Weyand, 38, and her husband, 40, finalized their wills in March.

“We have been working on them for quite some time, but before now, there has never been any urgency,” Dr. Weyand said. “Hearing about the high rate of infection in health care workers and the increasing number of deaths in young healthy people made us realize that this should be a priority.”

Dallas internist Bethany Agusala, MD, 36, and her husband, Kartik Agusala, MD, 41, a cardiologist, recently spent time engaged in the same activity. The couple, who work for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, have two children, aged 2 and 4.

“The chances are hopefully small that something bad would happen to either one of us, but it just seemed like a good time to get [a will] in place,” Dr. Bethany Agusala said in an interview. “It’s never an easy thing to think about.

Pediatric surgeon Chethan Sathya, MD, 34, and his wife, 31, a physician assistant, have vastly altered their home routine to prevent the risk of exposure to their 16-month-old daughter. Dr. Sathya works for the Northwell Health System in New York, which has hundreds of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Dr. Sathya said in an interview. He did not want to disclose his wife's name or institution, but said she works in a COVID-19 unit at a New York hospital.

When his wife returns home, she removes all of her clothes and places them in a bag, showers, and then isolates herself in the bedroom. Dr. Sathya brings his wife meals and then remains in a different room with their baby.

“It’s only been a few days,” he said. “We’re going to decide: Does she just stay in one room at all times or when she doesn’t work for a few days then after 1 day, can she come out? Should she get a hotel room elsewhere? These are the considerations.”

They employ an older nanny whom they also worry about, and with whom they try to limit contact, said Dr. Sathya, who practices at Cohen Children’s Medical Center. In a matter of weeks, Dr. Sathya anticipates he will be called upon to assist in some form with the COVID crisis.

“We haven’t figured that out. I’m not sure what we’ll do,” he said. “There is no perfect solution. You have to adapt. It’s very difficult to do so when you’re living in a condo in New York.”

For Dr. Griggs, life is much quieter at home without her husband and two “laughing, wiggly,” toddlers. Weekends are now defined by resting, video calls with her family, and exercising, when it’s safe, said Dr. Griggs, who recently penned a New York Times opinion piece about the pandemic and is also active on social media regarding personal protective equipment. She calls her husband her “rock” who never fails to put a smile on her face when they chat from across the miles. Her advice for other health care couples is to take it “one day at a time.”

“Don’t try to make plans weeks in advance or let your mind go to a dark place,” she said. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed. The only way to get through this is to focus on surviving each day.”

Editor's Note, 3/31/20: Due to incorrect information provided, the hospital where Dr. Sathya's wife works was misidentified. We have removed the name of that hospital. The story does not include his wife's employer, because Dr. Sathya did not have permission to disclose her workplace and she wishes to remain anonymous.

Not long ago, weekends for Cornelia Griggs, MD, meant making trips to the grocery store, chasing after two active toddlers, and eating brunch with her husband after a busy work week. But life has changed dramatically for the family since the spread of COVID-19. On a recent weekend, Dr. Griggs and her husband, Robert Goldstone, MD, spent their days off drafting a will.

“We’re both doctors, and we know that health care workers have an increased risk of contracting COVID,” said Dr. Griggs, a pediatric surgery fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “It felt like the responsible thing to do: Have a will in place to make sure our wishes are clear about who would manage our property and assets, and who would take care of our kids – God forbid.”

Outlining their final wishes is among many difficult decisions the doctors, both 36, have been forced to make in recent weeks. Dr. Goldstone, a general surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is no longer returning to New York during his time off, said Dr. Griggs, who has had known COVID-19 exposures. The couple’s children, aged 4 and almost 2, are temporarily living with their grandparents in Connecticut to decrease their exposure risk.

“I felt like it was safer for all of them to be there while I was going back and forth from the hospital,” Dr. Griggs said. “My husband is in Boston. The kids are in Connecticut and I’m in New York. That inherently is hard because our whole family is split up. I don’t know when it will be safe for me to see them again.”

Health professional couples across the country are facing similar challenges as they navigate the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, while trying to protect their families at home. From childcare dilemmas to quarantine quandaries to end-of-life considerations, partners who work in health care are confronting tough questions as the pandemic continues.

The biggest challenge is the uncertainty, says Angela Weyand, MD, an Ann Arbor, Mich.–based pediatric hematologist/oncologist who shares two young daughters with husband Ted Claflin, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician. Dr. Weyand said she and her husband are primarily working remotely now, but she knows that one or both could be deployed to the hospital to help care for patients, if the need arises. Nearby Detroit has been labeled a coronavirus “hot spot” by the U.S. Surgeon General.

“Right now, I think our biggest fear is spreading coronavirus to those we love, especially those in higher risk groups,” she said. “At the same time, we are also concerned about our own health and our future ability to be there for our children, a fear that, thankfully, neither one of us has ever had to face before. We are trying to take things one day at a time, acknowledging all that we have to be grateful for, and also learning to accept that many things right now are outside of our control.”

Dr. Weyand, 38, and her husband, 40, finalized their wills in March.

“We have been working on them for quite some time, but before now, there has never been any urgency,” Dr. Weyand said. “Hearing about the high rate of infection in health care workers and the increasing number of deaths in young healthy people made us realize that this should be a priority.”

Dallas internist Bethany Agusala, MD, 36, and her husband, Kartik Agusala, MD, 41, a cardiologist, recently spent time engaged in the same activity. The couple, who work for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, have two children, aged 2 and 4.

“The chances are hopefully small that something bad would happen to either one of us, but it just seemed like a good time to get [a will] in place,” Dr. Bethany Agusala said in an interview. “It’s never an easy thing to think about.

Pediatric surgeon Chethan Sathya, MD, 34, and his wife, 31, a physician assistant, have vastly altered their home routine to prevent the risk of exposure to their 16-month-old daughter. Dr. Sathya works for the Northwell Health System in New York, which has hundreds of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Dr. Sathya said in an interview. He did not want to disclose his wife's name or institution, but said she works in a COVID-19 unit at a New York hospital.

When his wife returns home, she removes all of her clothes and places them in a bag, showers, and then isolates herself in the bedroom. Dr. Sathya brings his wife meals and then remains in a different room with their baby.

“It’s only been a few days,” he said. “We’re going to decide: Does she just stay in one room at all times or when she doesn’t work for a few days then after 1 day, can she come out? Should she get a hotel room elsewhere? These are the considerations.”

They employ an older nanny whom they also worry about, and with whom they try to limit contact, said Dr. Sathya, who practices at Cohen Children’s Medical Center. In a matter of weeks, Dr. Sathya anticipates he will be called upon to assist in some form with the COVID crisis.

“We haven’t figured that out. I’m not sure what we’ll do,” he said. “There is no perfect solution. You have to adapt. It’s very difficult to do so when you’re living in a condo in New York.”

For Dr. Griggs, life is much quieter at home without her husband and two “laughing, wiggly,” toddlers. Weekends are now defined by resting, video calls with her family, and exercising, when it’s safe, said Dr. Griggs, who recently penned a New York Times opinion piece about the pandemic and is also active on social media regarding personal protective equipment. She calls her husband her “rock” who never fails to put a smile on her face when they chat from across the miles. Her advice for other health care couples is to take it “one day at a time.”

“Don’t try to make plans weeks in advance or let your mind go to a dark place,” she said. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed. The only way to get through this is to focus on surviving each day.”

Editor's Note, 3/31/20: Due to incorrect information provided, the hospital where Dr. Sathya's wife works was misidentified. We have removed the name of that hospital. The story does not include his wife's employer, because Dr. Sathya did not have permission to disclose her workplace and she wishes to remain anonymous.

Not long ago, weekends for Cornelia Griggs, MD, meant making trips to the grocery store, chasing after two active toddlers, and eating brunch with her husband after a busy work week. But life has changed dramatically for the family since the spread of COVID-19. On a recent weekend, Dr. Griggs and her husband, Robert Goldstone, MD, spent their days off drafting a will.

“We’re both doctors, and we know that health care workers have an increased risk of contracting COVID,” said Dr. Griggs, a pediatric surgery fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “It felt like the responsible thing to do: Have a will in place to make sure our wishes are clear about who would manage our property and assets, and who would take care of our kids – God forbid.”

Outlining their final wishes is among many difficult decisions the doctors, both 36, have been forced to make in recent weeks. Dr. Goldstone, a general surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is no longer returning to New York during his time off, said Dr. Griggs, who has had known COVID-19 exposures. The couple’s children, aged 4 and almost 2, are temporarily living with their grandparents in Connecticut to decrease their exposure risk.

“I felt like it was safer for all of them to be there while I was going back and forth from the hospital,” Dr. Griggs said. “My husband is in Boston. The kids are in Connecticut and I’m in New York. That inherently is hard because our whole family is split up. I don’t know when it will be safe for me to see them again.”

Health professional couples across the country are facing similar challenges as they navigate the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, while trying to protect their families at home. From childcare dilemmas to quarantine quandaries to end-of-life considerations, partners who work in health care are confronting tough questions as the pandemic continues.

The biggest challenge is the uncertainty, says Angela Weyand, MD, an Ann Arbor, Mich.–based pediatric hematologist/oncologist who shares two young daughters with husband Ted Claflin, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician. Dr. Weyand said she and her husband are primarily working remotely now, but she knows that one or both could be deployed to the hospital to help care for patients, if the need arises. Nearby Detroit has been labeled a coronavirus “hot spot” by the U.S. Surgeon General.

“Right now, I think our biggest fear is spreading coronavirus to those we love, especially those in higher risk groups,” she said. “At the same time, we are also concerned about our own health and our future ability to be there for our children, a fear that, thankfully, neither one of us has ever had to face before. We are trying to take things one day at a time, acknowledging all that we have to be grateful for, and also learning to accept that many things right now are outside of our control.”

Dr. Weyand, 38, and her husband, 40, finalized their wills in March.

“We have been working on them for quite some time, but before now, there has never been any urgency,” Dr. Weyand said. “Hearing about the high rate of infection in health care workers and the increasing number of deaths in young healthy people made us realize that this should be a priority.”

Dallas internist Bethany Agusala, MD, 36, and her husband, Kartik Agusala, MD, 41, a cardiologist, recently spent time engaged in the same activity. The couple, who work for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, have two children, aged 2 and 4.

“The chances are hopefully small that something bad would happen to either one of us, but it just seemed like a good time to get [a will] in place,” Dr. Bethany Agusala said in an interview. “It’s never an easy thing to think about.

Pediatric surgeon Chethan Sathya, MD, 34, and his wife, 31, a physician assistant, have vastly altered their home routine to prevent the risk of exposure to their 16-month-old daughter. Dr. Sathya works for the Northwell Health System in New York, which has hundreds of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Dr. Sathya said in an interview. He did not want to disclose his wife's name or institution, but said she works in a COVID-19 unit at a New York hospital.

When his wife returns home, she removes all of her clothes and places them in a bag, showers, and then isolates herself in the bedroom. Dr. Sathya brings his wife meals and then remains in a different room with their baby.

“It’s only been a few days,” he said. “We’re going to decide: Does she just stay in one room at all times or when she doesn’t work for a few days then after 1 day, can she come out? Should she get a hotel room elsewhere? These are the considerations.”

They employ an older nanny whom they also worry about, and with whom they try to limit contact, said Dr. Sathya, who practices at Cohen Children’s Medical Center. In a matter of weeks, Dr. Sathya anticipates he will be called upon to assist in some form with the COVID crisis.

“We haven’t figured that out. I’m not sure what we’ll do,” he said. “There is no perfect solution. You have to adapt. It’s very difficult to do so when you’re living in a condo in New York.”

For Dr. Griggs, life is much quieter at home without her husband and two “laughing, wiggly,” toddlers. Weekends are now defined by resting, video calls with her family, and exercising, when it’s safe, said Dr. Griggs, who recently penned a New York Times opinion piece about the pandemic and is also active on social media regarding personal protective equipment. She calls her husband her “rock” who never fails to put a smile on her face when they chat from across the miles. Her advice for other health care couples is to take it “one day at a time.”

“Don’t try to make plans weeks in advance or let your mind go to a dark place,” she said. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed. The only way to get through this is to focus on surviving each day.”

Editor's Note, 3/31/20: Due to incorrect information provided, the hospital where Dr. Sathya's wife works was misidentified. We have removed the name of that hospital. The story does not include his wife's employer, because Dr. Sathya did not have permission to disclose her workplace and she wishes to remain anonymous.

Flu activity measures continue COVID-19–related divergence

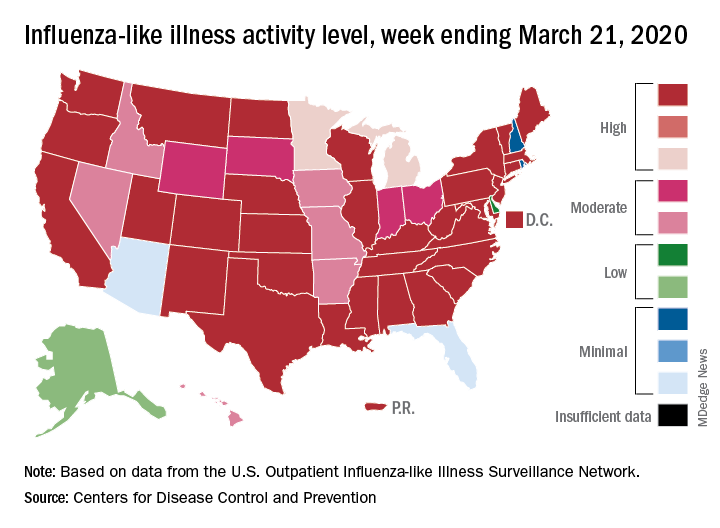

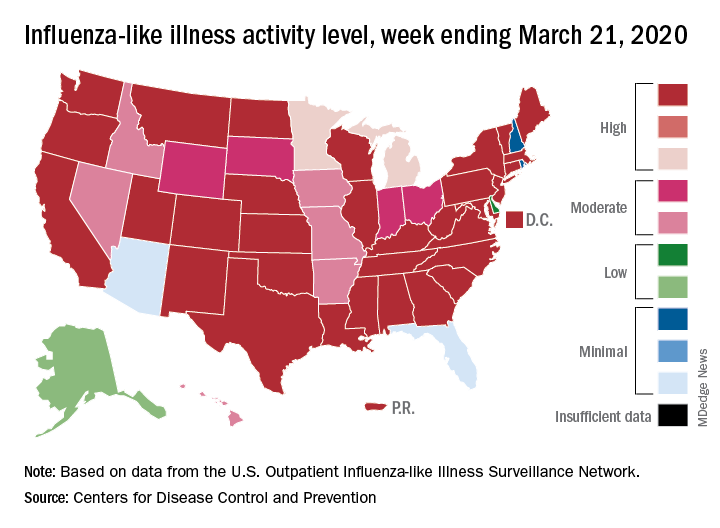

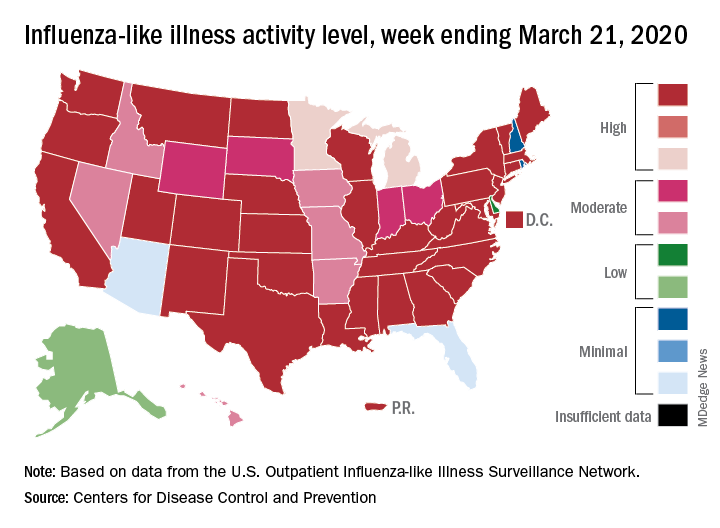

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.