User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

NSAID/triptan combination improves treatment-resistant migraine

The combination (AXS-07), in development by Axsome Therapeutics, was also safe and well tolerated, according to Cedric O’Gorman, MD, Axsome senior vice president for clinical development and medical affairs. It was tested in subjects who had inadequately responded to previous treatment and who had an average of 2-8 migraines per month.

The therapy combines 10-mg rizatriptan with 20-mg meloxicam delivered by the company’s MoSEIC technology. “Treatment with AXS-07 resulted in rapid, sustained, substantial, and statistically significant effect as compared with rizatriptan and placebo. The enhanced effect of AXS-07 may be especially relevant for patients with more difficult-to-treat migraine,” said Dr. O’Gorman during a presentation of the study at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Matthew Robbins, MD, said in an interview, “This combination may be particularly useful for patients who want to take an oral medication but still need rapid and sustained pain freedom.” Dr. Robbins is the neurology residency program director at New York Presbyterian Hospital and an associate professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. He was not involved in the research.

The study randomized 1,594 patients 2:2:2:1 to AXS-07, rizatriptan alone, MoSEIC meloxicam alone, or placebo, which could be administered immediately after a migraine event. Between 35% and 40% of participants across the groups had previously used triptans. The mean migraine treatment optimization questionnaire (mTOQ4) score was 3.6, indicating that the population was made up of people with poor responses to medication. Among patients in the study group, 37%-43% had severe pain intensity, 41%-47% were obese, and 35%-37% had morning migraine.

At 2 hours, more patients in the AXS-07 group than in the placebo group were pain free (19.9% vs. 6.7%; P < 0.001). They were also more likely to experience freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours (36.9% vs. 24.4%; P = 0.002). Secondary outcome measures favored the AXS-07 group when compared with the rizatriptan-only group, including 1-hour pain relief (44% vs. 37%; P = 0.04), 2- to 24-hour sustained pain relief (53% vs. 44%; P = 0.006), 2- to 48-hour sustained pain relief (47% vs. 37%; P = 0.003), 2- to 24-hour sustained pain freedom (16% vs. 11%; P = 0.038), 2- to 48-hour sustained pain freedom (15% vs. 8.8%; P = 0.003), rescue medication use (23% vs. 35%; P < 0.001), a rating of much or very much improved on the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C) scale (47% vs. 39%; P = 0.022), and functional improvement at 24 hours (64% vs. 56%; P = 0.027).

“The percentage of patients achieving pain relief with AXS-07 was numerically greater than with rizatriptan at every time point measure, starting at 15 minutes, and was statistically significant by 60 minutes. This is significant because rizatriptan is widely recognized as the fastest-acting and one of the most effective oral triptans,” said Dr. O’Gorman.

The frequency of adverse events was 11.0% in the AXS-07, 15.4% in the rizatriptan group, 11.5% in the meloxicam group, and 6.0% in the placebo group.

“The added benefit of this study was the demonstration of efficacy in patients who have previously failed other acute treatments. We know that ineffective acute treatments are a likely risk factor for the progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine, and the more options that we have for our patients, the better,” Dr. Robbins commented.

He remains concerned about cost and access, however. A limited number of tablets per month for acute treatments prompt clinicians to prescribe the medications individually and advise patients to take them in combination. “Rizatriptan is generally available in 12 monthly tablets by many coverage plans, and I would hope that, if ultimately FDA approved, a similar allotment is made affordable and accessible,” he said.

The study was funded by Axsome Therapeutics. Dr. O’Gorman is an employee of Axsome. Dr. Robbins has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: O’Gorman C et al. AHS 2020, Abstract 840673.

The combination (AXS-07), in development by Axsome Therapeutics, was also safe and well tolerated, according to Cedric O’Gorman, MD, Axsome senior vice president for clinical development and medical affairs. It was tested in subjects who had inadequately responded to previous treatment and who had an average of 2-8 migraines per month.

The therapy combines 10-mg rizatriptan with 20-mg meloxicam delivered by the company’s MoSEIC technology. “Treatment with AXS-07 resulted in rapid, sustained, substantial, and statistically significant effect as compared with rizatriptan and placebo. The enhanced effect of AXS-07 may be especially relevant for patients with more difficult-to-treat migraine,” said Dr. O’Gorman during a presentation of the study at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Matthew Robbins, MD, said in an interview, “This combination may be particularly useful for patients who want to take an oral medication but still need rapid and sustained pain freedom.” Dr. Robbins is the neurology residency program director at New York Presbyterian Hospital and an associate professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. He was not involved in the research.

The study randomized 1,594 patients 2:2:2:1 to AXS-07, rizatriptan alone, MoSEIC meloxicam alone, or placebo, which could be administered immediately after a migraine event. Between 35% and 40% of participants across the groups had previously used triptans. The mean migraine treatment optimization questionnaire (mTOQ4) score was 3.6, indicating that the population was made up of people with poor responses to medication. Among patients in the study group, 37%-43% had severe pain intensity, 41%-47% were obese, and 35%-37% had morning migraine.

At 2 hours, more patients in the AXS-07 group than in the placebo group were pain free (19.9% vs. 6.7%; P < 0.001). They were also more likely to experience freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours (36.9% vs. 24.4%; P = 0.002). Secondary outcome measures favored the AXS-07 group when compared with the rizatriptan-only group, including 1-hour pain relief (44% vs. 37%; P = 0.04), 2- to 24-hour sustained pain relief (53% vs. 44%; P = 0.006), 2- to 48-hour sustained pain relief (47% vs. 37%; P = 0.003), 2- to 24-hour sustained pain freedom (16% vs. 11%; P = 0.038), 2- to 48-hour sustained pain freedom (15% vs. 8.8%; P = 0.003), rescue medication use (23% vs. 35%; P < 0.001), a rating of much or very much improved on the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C) scale (47% vs. 39%; P = 0.022), and functional improvement at 24 hours (64% vs. 56%; P = 0.027).

“The percentage of patients achieving pain relief with AXS-07 was numerically greater than with rizatriptan at every time point measure, starting at 15 minutes, and was statistically significant by 60 minutes. This is significant because rizatriptan is widely recognized as the fastest-acting and one of the most effective oral triptans,” said Dr. O’Gorman.

The frequency of adverse events was 11.0% in the AXS-07, 15.4% in the rizatriptan group, 11.5% in the meloxicam group, and 6.0% in the placebo group.

“The added benefit of this study was the demonstration of efficacy in patients who have previously failed other acute treatments. We know that ineffective acute treatments are a likely risk factor for the progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine, and the more options that we have for our patients, the better,” Dr. Robbins commented.

He remains concerned about cost and access, however. A limited number of tablets per month for acute treatments prompt clinicians to prescribe the medications individually and advise patients to take them in combination. “Rizatriptan is generally available in 12 monthly tablets by many coverage plans, and I would hope that, if ultimately FDA approved, a similar allotment is made affordable and accessible,” he said.

The study was funded by Axsome Therapeutics. Dr. O’Gorman is an employee of Axsome. Dr. Robbins has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: O’Gorman C et al. AHS 2020, Abstract 840673.

The combination (AXS-07), in development by Axsome Therapeutics, was also safe and well tolerated, according to Cedric O’Gorman, MD, Axsome senior vice president for clinical development and medical affairs. It was tested in subjects who had inadequately responded to previous treatment and who had an average of 2-8 migraines per month.

The therapy combines 10-mg rizatriptan with 20-mg meloxicam delivered by the company’s MoSEIC technology. “Treatment with AXS-07 resulted in rapid, sustained, substantial, and statistically significant effect as compared with rizatriptan and placebo. The enhanced effect of AXS-07 may be especially relevant for patients with more difficult-to-treat migraine,” said Dr. O’Gorman during a presentation of the study at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Matthew Robbins, MD, said in an interview, “This combination may be particularly useful for patients who want to take an oral medication but still need rapid and sustained pain freedom.” Dr. Robbins is the neurology residency program director at New York Presbyterian Hospital and an associate professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. He was not involved in the research.

The study randomized 1,594 patients 2:2:2:1 to AXS-07, rizatriptan alone, MoSEIC meloxicam alone, or placebo, which could be administered immediately after a migraine event. Between 35% and 40% of participants across the groups had previously used triptans. The mean migraine treatment optimization questionnaire (mTOQ4) score was 3.6, indicating that the population was made up of people with poor responses to medication. Among patients in the study group, 37%-43% had severe pain intensity, 41%-47% were obese, and 35%-37% had morning migraine.

At 2 hours, more patients in the AXS-07 group than in the placebo group were pain free (19.9% vs. 6.7%; P < 0.001). They were also more likely to experience freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours (36.9% vs. 24.4%; P = 0.002). Secondary outcome measures favored the AXS-07 group when compared with the rizatriptan-only group, including 1-hour pain relief (44% vs. 37%; P = 0.04), 2- to 24-hour sustained pain relief (53% vs. 44%; P = 0.006), 2- to 48-hour sustained pain relief (47% vs. 37%; P = 0.003), 2- to 24-hour sustained pain freedom (16% vs. 11%; P = 0.038), 2- to 48-hour sustained pain freedom (15% vs. 8.8%; P = 0.003), rescue medication use (23% vs. 35%; P < 0.001), a rating of much or very much improved on the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C) scale (47% vs. 39%; P = 0.022), and functional improvement at 24 hours (64% vs. 56%; P = 0.027).

“The percentage of patients achieving pain relief with AXS-07 was numerically greater than with rizatriptan at every time point measure, starting at 15 minutes, and was statistically significant by 60 minutes. This is significant because rizatriptan is widely recognized as the fastest-acting and one of the most effective oral triptans,” said Dr. O’Gorman.

The frequency of adverse events was 11.0% in the AXS-07, 15.4% in the rizatriptan group, 11.5% in the meloxicam group, and 6.0% in the placebo group.

“The added benefit of this study was the demonstration of efficacy in patients who have previously failed other acute treatments. We know that ineffective acute treatments are a likely risk factor for the progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine, and the more options that we have for our patients, the better,” Dr. Robbins commented.

He remains concerned about cost and access, however. A limited number of tablets per month for acute treatments prompt clinicians to prescribe the medications individually and advise patients to take them in combination. “Rizatriptan is generally available in 12 monthly tablets by many coverage plans, and I would hope that, if ultimately FDA approved, a similar allotment is made affordable and accessible,” he said.

The study was funded by Axsome Therapeutics. Dr. O’Gorman is an employee of Axsome. Dr. Robbins has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: O’Gorman C et al. AHS 2020, Abstract 840673.

FROM AHS 2020

Lung ultrasound works well in children with COVID-19

researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

They also noted the benefits that modality provides over other imaging techniques.

Marco Denina, MD, and colleagues from the pediatric infectious diseases unit at Regina Margherita Children’s Hospital in Turin, Italy, performed an observational study of eight children aged 0-17 years who were admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 between March 8 and 26, 2020. In seven of eight patients, the findings were concordant between imaging modalities; in the remaining patient, lung ultrasound (LUS) found an interstitial B-lines pattern that was not seen on radiography. In seven patients with pathologic ultrasound findings at baseline, the improvement or resolution of the subpleural consolidations or interstitial patterns was consistent with concomitant radiologic findings.

The authors cited the benefits of using point-of-care ultrasound instead of other modalities, such as CT. “First, it may reduce the number of radiologic examinations, lowering the radiation exposure of the patients,” they wrote. “Secondly, when performed at the bedside, LUS allows for the reduction of the patient’s movement within the hospital; thus, it lowers the number of health care workers and medical devices exposed to [SARS-CoV-2].”

One limitation of the study is the small sample size; however, the researchers felt the high concordance still suggests LUS is a reasonable method for COVID-19 patients.

There was no external funding for this study and the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Denina M et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157.

researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

They also noted the benefits that modality provides over other imaging techniques.

Marco Denina, MD, and colleagues from the pediatric infectious diseases unit at Regina Margherita Children’s Hospital in Turin, Italy, performed an observational study of eight children aged 0-17 years who were admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 between March 8 and 26, 2020. In seven of eight patients, the findings were concordant between imaging modalities; in the remaining patient, lung ultrasound (LUS) found an interstitial B-lines pattern that was not seen on radiography. In seven patients with pathologic ultrasound findings at baseline, the improvement or resolution of the subpleural consolidations or interstitial patterns was consistent with concomitant radiologic findings.

The authors cited the benefits of using point-of-care ultrasound instead of other modalities, such as CT. “First, it may reduce the number of radiologic examinations, lowering the radiation exposure of the patients,” they wrote. “Secondly, when performed at the bedside, LUS allows for the reduction of the patient’s movement within the hospital; thus, it lowers the number of health care workers and medical devices exposed to [SARS-CoV-2].”

One limitation of the study is the small sample size; however, the researchers felt the high concordance still suggests LUS is a reasonable method for COVID-19 patients.

There was no external funding for this study and the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Denina M et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157.

researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

They also noted the benefits that modality provides over other imaging techniques.

Marco Denina, MD, and colleagues from the pediatric infectious diseases unit at Regina Margherita Children’s Hospital in Turin, Italy, performed an observational study of eight children aged 0-17 years who were admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 between March 8 and 26, 2020. In seven of eight patients, the findings were concordant between imaging modalities; in the remaining patient, lung ultrasound (LUS) found an interstitial B-lines pattern that was not seen on radiography. In seven patients with pathologic ultrasound findings at baseline, the improvement or resolution of the subpleural consolidations or interstitial patterns was consistent with concomitant radiologic findings.

The authors cited the benefits of using point-of-care ultrasound instead of other modalities, such as CT. “First, it may reduce the number of radiologic examinations, lowering the radiation exposure of the patients,” they wrote. “Secondly, when performed at the bedside, LUS allows for the reduction of the patient’s movement within the hospital; thus, it lowers the number of health care workers and medical devices exposed to [SARS-CoV-2].”

One limitation of the study is the small sample size; however, the researchers felt the high concordance still suggests LUS is a reasonable method for COVID-19 patients.

There was no external funding for this study and the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Denina M et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157.

FROM PEDIATRICS

CGRPs in real world: Similar efficacy, more AEs

and has found that patients who fail on one of the treatments are likely to fail again if they’re switched to another.

At the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Larry Robbins, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Chicago Medical School, North Chicago, reported on the results of his postapproval study of 369 migraine patients taking one of the three approved CGRP mAbs. “If patients do not do well on one mAb, it is sometimes worthwhile to switch, but most patients do not do well from the second or third mAb as well,” Dr. Robbins said in an interview. “In addition, there are numerous adverse effects that were not captured in the official phase 3 studies. Efficacy has held up well, but for a number of reasons, the true adverse event profile is often missed.”

Assessing efficacy and adverse events

In evaluating the efficacy of the three approved CGRP mAbs, Dr. Robbins used measures of degree of relief based on percentage decrease of symptoms versus baseline and the number of migraine days, combined with the number of moderate or severe headache days. Most of the patients kept calendars and were interviewed by two headache specialists. The study also utilized a 10-point visual analog scale and averaged relief over 3 months.

Of the patients on erenumab (n = 220), 10% described 95%-100% relief of symptoms, 24% reported 71%-100% relief, 34% described 31%-70% relief, and 43% experienced 0%-30% relief. Adverse events among this group included constipation (20%), nausea (7%), increased headache and fatigue (5% for each), and joint pain and depression (3% for each). Three patients on erenumab experienced unspecified serious adverse reactions.

In the fremanezumab group (n = 79), 8% described 95%-100% relief, 18% had 71%-100% relief, 33% experienced 31%-70% improvement, and 50% had 30% improvement or less. Adverse events in these patients included nausea, constipation, and depression (6% each); increased headache and muscle pain or cramps (5% each); rash, joint pain, anxiety, fatigue, or weight gain (4% for each ); and injection-site reactions, irritability, or alopecia (3% combined).

Patients taking galcanezumab (n = 70) reported the following outcomes: 3% had 95%-100% relief of symptoms, 14% had 71%-100% relief, 46% with 31%-70% relief, and 40% had 0%-30% relief. This group’s adverse events included constipation (10%); depression and increased headache (6% for each); nausea, fatigue, or injection-site reactions (4% each ); and muscle pain or cramps, rash, anxiety, weight gain, or alopecia (3% each).

Dr. Robbins also assessed switching from one CGRP mAb to another for various reasons. “When the reason for switching was poor efficacy, only 27% of patients did well,” he stated in the presentation. “If the reason was adverse events, 33% did well. When insurance/financial reasons alone were the reason, but efficacy was adequate, 58% did well after switching.”

Overall, postapproval efficacy of the medications “held up well,” Dr. Robbins noted. “Efficacy after 2 months somewhat predicted how patients would do after 6 months.” Among the predictors of poor response his study identified were opioid use and moderate or severe refractory chronic migraine at baseline.

However, the rates of adverse events he reported were significantly greater than those reported in the clinical trials, Dr. Robbins said. He noted four reasons to explain this discrepancy: the trials did not use an 18-item supplemental checklist that he has advocated to identify patients at risk of side effects, the trials weren’t powered for adverse events, patients in the trials tended to be less refractory than those in the clinic, and that adverse events tend to be underreported in trials.

“Adverse events become disaggregated, with the same descriptors used for an adverse event,” Dr. Robbins said. “Examples include fatigue, somnolence, and tiredness; all may be 1%, while different patients are describing the same adverse event. It is possible to reaggregate the adverse events after the study, but this is fraught with error.”

Uncovering shortcomings in clinical trials

Emily Rubenstein Engel, MD, director of the Dalessio Headache Center at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., noted that Dr. Robbins’ findings are significant for two reasons. “Dr. Robbins has uncovered a general flaw in clinical trials, whereby the lack of consistency of adverse event terminology as well as the lack of a standardized questionnaire format for adverse events can result in significant under-reporting of adverse events,” she said.

“Specifically for the CGRPs,” Dr. Engel continued, “he has raised awareness that this new class of medication, however promising from an efficacy standpoint, has side effects that are much more frequent and severe than seen in the initial clinical trials.”

Dr. Robbins reported financial relationships with Allergan, Amgen and Teva. Dr. Engel has no financial relationships to disclose.

and has found that patients who fail on one of the treatments are likely to fail again if they’re switched to another.

At the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Larry Robbins, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Chicago Medical School, North Chicago, reported on the results of his postapproval study of 369 migraine patients taking one of the three approved CGRP mAbs. “If patients do not do well on one mAb, it is sometimes worthwhile to switch, but most patients do not do well from the second or third mAb as well,” Dr. Robbins said in an interview. “In addition, there are numerous adverse effects that were not captured in the official phase 3 studies. Efficacy has held up well, but for a number of reasons, the true adverse event profile is often missed.”

Assessing efficacy and adverse events

In evaluating the efficacy of the three approved CGRP mAbs, Dr. Robbins used measures of degree of relief based on percentage decrease of symptoms versus baseline and the number of migraine days, combined with the number of moderate or severe headache days. Most of the patients kept calendars and were interviewed by two headache specialists. The study also utilized a 10-point visual analog scale and averaged relief over 3 months.

Of the patients on erenumab (n = 220), 10% described 95%-100% relief of symptoms, 24% reported 71%-100% relief, 34% described 31%-70% relief, and 43% experienced 0%-30% relief. Adverse events among this group included constipation (20%), nausea (7%), increased headache and fatigue (5% for each), and joint pain and depression (3% for each). Three patients on erenumab experienced unspecified serious adverse reactions.

In the fremanezumab group (n = 79), 8% described 95%-100% relief, 18% had 71%-100% relief, 33% experienced 31%-70% improvement, and 50% had 30% improvement or less. Adverse events in these patients included nausea, constipation, and depression (6% each); increased headache and muscle pain or cramps (5% each); rash, joint pain, anxiety, fatigue, or weight gain (4% for each ); and injection-site reactions, irritability, or alopecia (3% combined).

Patients taking galcanezumab (n = 70) reported the following outcomes: 3% had 95%-100% relief of symptoms, 14% had 71%-100% relief, 46% with 31%-70% relief, and 40% had 0%-30% relief. This group’s adverse events included constipation (10%); depression and increased headache (6% for each); nausea, fatigue, or injection-site reactions (4% each ); and muscle pain or cramps, rash, anxiety, weight gain, or alopecia (3% each).

Dr. Robbins also assessed switching from one CGRP mAb to another for various reasons. “When the reason for switching was poor efficacy, only 27% of patients did well,” he stated in the presentation. “If the reason was adverse events, 33% did well. When insurance/financial reasons alone were the reason, but efficacy was adequate, 58% did well after switching.”

Overall, postapproval efficacy of the medications “held up well,” Dr. Robbins noted. “Efficacy after 2 months somewhat predicted how patients would do after 6 months.” Among the predictors of poor response his study identified were opioid use and moderate or severe refractory chronic migraine at baseline.

However, the rates of adverse events he reported were significantly greater than those reported in the clinical trials, Dr. Robbins said. He noted four reasons to explain this discrepancy: the trials did not use an 18-item supplemental checklist that he has advocated to identify patients at risk of side effects, the trials weren’t powered for adverse events, patients in the trials tended to be less refractory than those in the clinic, and that adverse events tend to be underreported in trials.

“Adverse events become disaggregated, with the same descriptors used for an adverse event,” Dr. Robbins said. “Examples include fatigue, somnolence, and tiredness; all may be 1%, while different patients are describing the same adverse event. It is possible to reaggregate the adverse events after the study, but this is fraught with error.”

Uncovering shortcomings in clinical trials

Emily Rubenstein Engel, MD, director of the Dalessio Headache Center at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., noted that Dr. Robbins’ findings are significant for two reasons. “Dr. Robbins has uncovered a general flaw in clinical trials, whereby the lack of consistency of adverse event terminology as well as the lack of a standardized questionnaire format for adverse events can result in significant under-reporting of adverse events,” she said.

“Specifically for the CGRPs,” Dr. Engel continued, “he has raised awareness that this new class of medication, however promising from an efficacy standpoint, has side effects that are much more frequent and severe than seen in the initial clinical trials.”

Dr. Robbins reported financial relationships with Allergan, Amgen and Teva. Dr. Engel has no financial relationships to disclose.

and has found that patients who fail on one of the treatments are likely to fail again if they’re switched to another.

At the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Larry Robbins, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Chicago Medical School, North Chicago, reported on the results of his postapproval study of 369 migraine patients taking one of the three approved CGRP mAbs. “If patients do not do well on one mAb, it is sometimes worthwhile to switch, but most patients do not do well from the second or third mAb as well,” Dr. Robbins said in an interview. “In addition, there are numerous adverse effects that were not captured in the official phase 3 studies. Efficacy has held up well, but for a number of reasons, the true adverse event profile is often missed.”

Assessing efficacy and adverse events

In evaluating the efficacy of the three approved CGRP mAbs, Dr. Robbins used measures of degree of relief based on percentage decrease of symptoms versus baseline and the number of migraine days, combined with the number of moderate or severe headache days. Most of the patients kept calendars and were interviewed by two headache specialists. The study also utilized a 10-point visual analog scale and averaged relief over 3 months.

Of the patients on erenumab (n = 220), 10% described 95%-100% relief of symptoms, 24% reported 71%-100% relief, 34% described 31%-70% relief, and 43% experienced 0%-30% relief. Adverse events among this group included constipation (20%), nausea (7%), increased headache and fatigue (5% for each), and joint pain and depression (3% for each). Three patients on erenumab experienced unspecified serious adverse reactions.

In the fremanezumab group (n = 79), 8% described 95%-100% relief, 18% had 71%-100% relief, 33% experienced 31%-70% improvement, and 50% had 30% improvement or less. Adverse events in these patients included nausea, constipation, and depression (6% each); increased headache and muscle pain or cramps (5% each); rash, joint pain, anxiety, fatigue, or weight gain (4% for each ); and injection-site reactions, irritability, or alopecia (3% combined).

Patients taking galcanezumab (n = 70) reported the following outcomes: 3% had 95%-100% relief of symptoms, 14% had 71%-100% relief, 46% with 31%-70% relief, and 40% had 0%-30% relief. This group’s adverse events included constipation (10%); depression and increased headache (6% for each); nausea, fatigue, or injection-site reactions (4% each ); and muscle pain or cramps, rash, anxiety, weight gain, or alopecia (3% each).

Dr. Robbins also assessed switching from one CGRP mAb to another for various reasons. “When the reason for switching was poor efficacy, only 27% of patients did well,” he stated in the presentation. “If the reason was adverse events, 33% did well. When insurance/financial reasons alone were the reason, but efficacy was adequate, 58% did well after switching.”

Overall, postapproval efficacy of the medications “held up well,” Dr. Robbins noted. “Efficacy after 2 months somewhat predicted how patients would do after 6 months.” Among the predictors of poor response his study identified were opioid use and moderate or severe refractory chronic migraine at baseline.

However, the rates of adverse events he reported were significantly greater than those reported in the clinical trials, Dr. Robbins said. He noted four reasons to explain this discrepancy: the trials did not use an 18-item supplemental checklist that he has advocated to identify patients at risk of side effects, the trials weren’t powered for adverse events, patients in the trials tended to be less refractory than those in the clinic, and that adverse events tend to be underreported in trials.

“Adverse events become disaggregated, with the same descriptors used for an adverse event,” Dr. Robbins said. “Examples include fatigue, somnolence, and tiredness; all may be 1%, while different patients are describing the same adverse event. It is possible to reaggregate the adverse events after the study, but this is fraught with error.”

Uncovering shortcomings in clinical trials

Emily Rubenstein Engel, MD, director of the Dalessio Headache Center at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., noted that Dr. Robbins’ findings are significant for two reasons. “Dr. Robbins has uncovered a general flaw in clinical trials, whereby the lack of consistency of adverse event terminology as well as the lack of a standardized questionnaire format for adverse events can result in significant under-reporting of adverse events,” she said.

“Specifically for the CGRPs,” Dr. Engel continued, “he has raised awareness that this new class of medication, however promising from an efficacy standpoint, has side effects that are much more frequent and severe than seen in the initial clinical trials.”

Dr. Robbins reported financial relationships with Allergan, Amgen and Teva. Dr. Engel has no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM AHS 2020

Intranasal DHE shows promise in migraine

, according to results from a phase 3 clinical trial. In development by Impel NeuroPharma, the new formulation could offer patients an at-home alternative to intramuscular infusions or intravenous injections currently used to deliver DHE.

“Our analysis of the data suggests that nothing new or untoward seemed to be happening as a result of delivering DHE to the upper nasal space,” Stephen Shrewsbury, MD, chief medical officer of Impel NeuroPharma, said in an interview. The company released key results from its phase 3 clinical trial, while a poster examining patient satisfaction was presented by Dr. Shrewsbury at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

An improved intranasal formulation

The product isn’t the first effort to develop an inhaled form of DHE. An inhaled version called Migranal, marketed by Bausch Health, delivers DHE to the front part of the nose, where it may be lost to the upper lip or down the throat, according to Dr. Shrewsbury. Impel’s formulation (INP104) delivers the drug to the upper nasal space, where an earlier phase 1 trial demonstrated it could achieve higher serum concentrations compared with Migranal.

In 2018, MAP Pharmaceuticals came close to a product, but it was ultimately rejected by the Food and Drug Administration because DHE was not stable in the propellant used in the formulation. This time is different, said Dr. Shrewsbury, who was chief medical officer at MAP before joining Impel. The new device holds DHE and the propellant in separate compartments until they are combined right before use, which should circumvent stability problems.

Dr. Shrewsbury believes that patients will welcome an inhaled version of DHE. “People with migraines don’t want to have to go into hospital or even an infusion center if they can help it,” he said.

The study was one of a number of presentations at the AHS meeting that focused on novel delivery methods for established drugs. “The idea of taking things that we know work and improving upon them, both in terms of formulation and then delivery, that’s a common theme. My impression is that this will be an interesting arrow to have in our sling,” said Andrew Charles, MD, professor of neurology and director of the UCLA Goldberg Migraine Program, who was not involved in the study.

Open-label trial results

The STOP 301 phase 3 open-label safety and tolerability trial treated over 5,650 migraine attacks in 354 patients who self-administered INP104 for up to 52 weeks. They were provided up to three doses per week (1.45 mg in a dose of two puffs, one per nostril). Maximum doses included two per day and three per week.

There were no new safety signals or concern trends in nasal safety findings. 15.0% of patients experienced nasal congestion, 6.8% nausea, 5.1% nasal discomfort, and 5.1% unpleasant taste.

A total of 66.3% of participants reported pain relief by 2 hours (severe or moderate pain reduced to mild or none, or mild pain reduced to none) following a dose, and 38% had freedom from pain. 16.3% reported pain relief onset at 15 minutes, with continued improvement over time. During weeks 21-24 of the study, 98.4% and 95% of patients reporting no recurrence of their migraine or use of rescue medications during the 24- and 48-hour periods after using INP104. “Once they got rid of the pain, it didn’t come back, and that’s been one of the shortcomings of many of the available oral therapies – although some of them can be quite effective, that effect can wear off and people can find their migraine comes back within a 24- or 48-hour period,” said Dr. Shrewsbury.

The drug was also rated as convenient, with 83.6% of participants strongly agreeing (50%) or agreeing (33.6%) that it is easy to use.

“It certainly looks like compliance will be good. The possibility is that this will be quite useful,” said Dr. Charles, who is also enthusiastic about some of the other drug formulations announced at the meeting. “It really is just fun times for us as clinicians to be able to have so many different options for patients,” he said.

Dr. Shrewsbury is an employee of Impel NeuroPharma, which funded the study.* Dr. Charles consults for Amgen, BioHaven, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Shrewsbury S, et al. AHS 2020. Abstract 832509.

*Correction, 6/19/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Impel NeuroPharma.

, according to results from a phase 3 clinical trial. In development by Impel NeuroPharma, the new formulation could offer patients an at-home alternative to intramuscular infusions or intravenous injections currently used to deliver DHE.

“Our analysis of the data suggests that nothing new or untoward seemed to be happening as a result of delivering DHE to the upper nasal space,” Stephen Shrewsbury, MD, chief medical officer of Impel NeuroPharma, said in an interview. The company released key results from its phase 3 clinical trial, while a poster examining patient satisfaction was presented by Dr. Shrewsbury at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

An improved intranasal formulation

The product isn’t the first effort to develop an inhaled form of DHE. An inhaled version called Migranal, marketed by Bausch Health, delivers DHE to the front part of the nose, where it may be lost to the upper lip or down the throat, according to Dr. Shrewsbury. Impel’s formulation (INP104) delivers the drug to the upper nasal space, where an earlier phase 1 trial demonstrated it could achieve higher serum concentrations compared with Migranal.

In 2018, MAP Pharmaceuticals came close to a product, but it was ultimately rejected by the Food and Drug Administration because DHE was not stable in the propellant used in the formulation. This time is different, said Dr. Shrewsbury, who was chief medical officer at MAP before joining Impel. The new device holds DHE and the propellant in separate compartments until they are combined right before use, which should circumvent stability problems.

Dr. Shrewsbury believes that patients will welcome an inhaled version of DHE. “People with migraines don’t want to have to go into hospital or even an infusion center if they can help it,” he said.

The study was one of a number of presentations at the AHS meeting that focused on novel delivery methods for established drugs. “The idea of taking things that we know work and improving upon them, both in terms of formulation and then delivery, that’s a common theme. My impression is that this will be an interesting arrow to have in our sling,” said Andrew Charles, MD, professor of neurology and director of the UCLA Goldberg Migraine Program, who was not involved in the study.

Open-label trial results

The STOP 301 phase 3 open-label safety and tolerability trial treated over 5,650 migraine attacks in 354 patients who self-administered INP104 for up to 52 weeks. They were provided up to three doses per week (1.45 mg in a dose of two puffs, one per nostril). Maximum doses included two per day and three per week.

There were no new safety signals or concern trends in nasal safety findings. 15.0% of patients experienced nasal congestion, 6.8% nausea, 5.1% nasal discomfort, and 5.1% unpleasant taste.

A total of 66.3% of participants reported pain relief by 2 hours (severe or moderate pain reduced to mild or none, or mild pain reduced to none) following a dose, and 38% had freedom from pain. 16.3% reported pain relief onset at 15 minutes, with continued improvement over time. During weeks 21-24 of the study, 98.4% and 95% of patients reporting no recurrence of their migraine or use of rescue medications during the 24- and 48-hour periods after using INP104. “Once they got rid of the pain, it didn’t come back, and that’s been one of the shortcomings of many of the available oral therapies – although some of them can be quite effective, that effect can wear off and people can find their migraine comes back within a 24- or 48-hour period,” said Dr. Shrewsbury.

The drug was also rated as convenient, with 83.6% of participants strongly agreeing (50%) or agreeing (33.6%) that it is easy to use.

“It certainly looks like compliance will be good. The possibility is that this will be quite useful,” said Dr. Charles, who is also enthusiastic about some of the other drug formulations announced at the meeting. “It really is just fun times for us as clinicians to be able to have so many different options for patients,” he said.

Dr. Shrewsbury is an employee of Impel NeuroPharma, which funded the study.* Dr. Charles consults for Amgen, BioHaven, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Shrewsbury S, et al. AHS 2020. Abstract 832509.

*Correction, 6/19/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Impel NeuroPharma.

, according to results from a phase 3 clinical trial. In development by Impel NeuroPharma, the new formulation could offer patients an at-home alternative to intramuscular infusions or intravenous injections currently used to deliver DHE.

“Our analysis of the data suggests that nothing new or untoward seemed to be happening as a result of delivering DHE to the upper nasal space,” Stephen Shrewsbury, MD, chief medical officer of Impel NeuroPharma, said in an interview. The company released key results from its phase 3 clinical trial, while a poster examining patient satisfaction was presented by Dr. Shrewsbury at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

An improved intranasal formulation

The product isn’t the first effort to develop an inhaled form of DHE. An inhaled version called Migranal, marketed by Bausch Health, delivers DHE to the front part of the nose, where it may be lost to the upper lip or down the throat, according to Dr. Shrewsbury. Impel’s formulation (INP104) delivers the drug to the upper nasal space, where an earlier phase 1 trial demonstrated it could achieve higher serum concentrations compared with Migranal.

In 2018, MAP Pharmaceuticals came close to a product, but it was ultimately rejected by the Food and Drug Administration because DHE was not stable in the propellant used in the formulation. This time is different, said Dr. Shrewsbury, who was chief medical officer at MAP before joining Impel. The new device holds DHE and the propellant in separate compartments until they are combined right before use, which should circumvent stability problems.

Dr. Shrewsbury believes that patients will welcome an inhaled version of DHE. “People with migraines don’t want to have to go into hospital or even an infusion center if they can help it,” he said.

The study was one of a number of presentations at the AHS meeting that focused on novel delivery methods for established drugs. “The idea of taking things that we know work and improving upon them, both in terms of formulation and then delivery, that’s a common theme. My impression is that this will be an interesting arrow to have in our sling,” said Andrew Charles, MD, professor of neurology and director of the UCLA Goldberg Migraine Program, who was not involved in the study.

Open-label trial results

The STOP 301 phase 3 open-label safety and tolerability trial treated over 5,650 migraine attacks in 354 patients who self-administered INP104 for up to 52 weeks. They were provided up to three doses per week (1.45 mg in a dose of two puffs, one per nostril). Maximum doses included two per day and three per week.

There were no new safety signals or concern trends in nasal safety findings. 15.0% of patients experienced nasal congestion, 6.8% nausea, 5.1% nasal discomfort, and 5.1% unpleasant taste.

A total of 66.3% of participants reported pain relief by 2 hours (severe or moderate pain reduced to mild or none, or mild pain reduced to none) following a dose, and 38% had freedom from pain. 16.3% reported pain relief onset at 15 minutes, with continued improvement over time. During weeks 21-24 of the study, 98.4% and 95% of patients reporting no recurrence of their migraine or use of rescue medications during the 24- and 48-hour periods after using INP104. “Once they got rid of the pain, it didn’t come back, and that’s been one of the shortcomings of many of the available oral therapies – although some of them can be quite effective, that effect can wear off and people can find their migraine comes back within a 24- or 48-hour period,” said Dr. Shrewsbury.

The drug was also rated as convenient, with 83.6% of participants strongly agreeing (50%) or agreeing (33.6%) that it is easy to use.

“It certainly looks like compliance will be good. The possibility is that this will be quite useful,” said Dr. Charles, who is also enthusiastic about some of the other drug formulations announced at the meeting. “It really is just fun times for us as clinicians to be able to have so many different options for patients,” he said.

Dr. Shrewsbury is an employee of Impel NeuroPharma, which funded the study.* Dr. Charles consults for Amgen, BioHaven, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Shrewsbury S, et al. AHS 2020. Abstract 832509.

*Correction, 6/19/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Impel NeuroPharma.

FROM AHS 2020

Face mask type matters when sterilizing, study finds

according to researchers. The greatest reduction in filtration efficiency after sterilization occurred with surgical face masks.

With plasma vapor hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sterilization, filtration efficiency of N95 and KN95 masks was maintained at more than 95%, but for surgical face masks, filtration efficiency was reduced to less than 95%. With chlorine dioxide (ClO2) sterilization, on the other hand, filtration efficiency was maintained at above 95% for N95 masks, but for KN95 and surgical face masks, filtration efficiency was reduced to less than 80%.

In a research letter published online June 15 in JAMA Network Open, researchers from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, report the results of a study of the two sterilization techniques on the pressure drop and filtration efficiency of N95, KN95, and surgical face masks.

“The H2O2 treatment showed a small effect on the overall filtration efficiency of the tested masks, but the ClO2 treatment showed marked reduction in the overall filtration efficiency of the KN95s and surgical face masks. All pressure drop changes were within the acceptable range,” the researchers write.

The study did not evaluate the effect of repeated sterilizations on face masks.

Five masks of each type were sterilized with either H2O2 or ClO2. Masks were then placed in a test chamber, and a salt aerosol was nebulized to assess both upstream and downstream filtration as well as pressure drop. The researchers used a mobility particle sizer to measure particle number concentration from 16.8 nm to 514 nm. An acceptable pressure drop was defined as a drop of less than 1.38 inches of water (35 mm) for inhalation.

Although pressure drop changes were within the acceptable range for all three mask types following sterilization with either method, H2O2 sterilization yielded the least reduction in filtration efficacy in all cases. After sterilization with H2O2, filtration efficiencies were 96.6%, 97.1%, and 91.6% for the N95s, KN95s, and the surgical face masks, respectively. In contrast, filtration efficiencies after ClO2 sterilization were 95.1%, 76.2%, and 77.9%, respectively.

The researchers note that, although overall filtration efficiency was maintained with ClO2 sterilization, there was a significant drop in efficiency with respect to particles of approximately 300 nm (0.3 microns) in size. For particles of that size, mean filtration efficiency decreased to 86.2% for N95s, 40.8% for KN95s, and 47.1% for surgical face masks.

The testing described in the report is “quite affordable at $350 per mask type, so it is hard to imagine any health care provider cannot set aside a small budget to conduct such an important test,” author Evan Floyd, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

Given the high demand for effective face masks and the current risk for counterfeit products, Floyd suggested that individual facilities test all masks intended for use by healthcare workers before and after sterilization procedures.

“However, if for some reason testing is not an option, we would recommend sticking to established brands and suppliers, perhaps reach out to your state health department or a local representative of the strategic stockpile of PPE,” he noted.

The authors acknowledge that further studies using a larger sample size and a greater variety of masks, as well as studies to evaluate different sterilization techniques, are required. Further, “measuring the respirator’s filtration efficiency by aerosol size instead of only measuring the overall filtration efficiency” should also be considered. Such an approach would enable researchers to evaluate the degree to which masks protect against specific infectious agents.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to researchers. The greatest reduction in filtration efficiency after sterilization occurred with surgical face masks.

With plasma vapor hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sterilization, filtration efficiency of N95 and KN95 masks was maintained at more than 95%, but for surgical face masks, filtration efficiency was reduced to less than 95%. With chlorine dioxide (ClO2) sterilization, on the other hand, filtration efficiency was maintained at above 95% for N95 masks, but for KN95 and surgical face masks, filtration efficiency was reduced to less than 80%.

In a research letter published online June 15 in JAMA Network Open, researchers from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, report the results of a study of the two sterilization techniques on the pressure drop and filtration efficiency of N95, KN95, and surgical face masks.

“The H2O2 treatment showed a small effect on the overall filtration efficiency of the tested masks, but the ClO2 treatment showed marked reduction in the overall filtration efficiency of the KN95s and surgical face masks. All pressure drop changes were within the acceptable range,” the researchers write.

The study did not evaluate the effect of repeated sterilizations on face masks.

Five masks of each type were sterilized with either H2O2 or ClO2. Masks were then placed in a test chamber, and a salt aerosol was nebulized to assess both upstream and downstream filtration as well as pressure drop. The researchers used a mobility particle sizer to measure particle number concentration from 16.8 nm to 514 nm. An acceptable pressure drop was defined as a drop of less than 1.38 inches of water (35 mm) for inhalation.

Although pressure drop changes were within the acceptable range for all three mask types following sterilization with either method, H2O2 sterilization yielded the least reduction in filtration efficacy in all cases. After sterilization with H2O2, filtration efficiencies were 96.6%, 97.1%, and 91.6% for the N95s, KN95s, and the surgical face masks, respectively. In contrast, filtration efficiencies after ClO2 sterilization were 95.1%, 76.2%, and 77.9%, respectively.

The researchers note that, although overall filtration efficiency was maintained with ClO2 sterilization, there was a significant drop in efficiency with respect to particles of approximately 300 nm (0.3 microns) in size. For particles of that size, mean filtration efficiency decreased to 86.2% for N95s, 40.8% for KN95s, and 47.1% for surgical face masks.

The testing described in the report is “quite affordable at $350 per mask type, so it is hard to imagine any health care provider cannot set aside a small budget to conduct such an important test,” author Evan Floyd, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

Given the high demand for effective face masks and the current risk for counterfeit products, Floyd suggested that individual facilities test all masks intended for use by healthcare workers before and after sterilization procedures.

“However, if for some reason testing is not an option, we would recommend sticking to established brands and suppliers, perhaps reach out to your state health department or a local representative of the strategic stockpile of PPE,” he noted.

The authors acknowledge that further studies using a larger sample size and a greater variety of masks, as well as studies to evaluate different sterilization techniques, are required. Further, “measuring the respirator’s filtration efficiency by aerosol size instead of only measuring the overall filtration efficiency” should also be considered. Such an approach would enable researchers to evaluate the degree to which masks protect against specific infectious agents.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to researchers. The greatest reduction in filtration efficiency after sterilization occurred with surgical face masks.

With plasma vapor hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sterilization, filtration efficiency of N95 and KN95 masks was maintained at more than 95%, but for surgical face masks, filtration efficiency was reduced to less than 95%. With chlorine dioxide (ClO2) sterilization, on the other hand, filtration efficiency was maintained at above 95% for N95 masks, but for KN95 and surgical face masks, filtration efficiency was reduced to less than 80%.

In a research letter published online June 15 in JAMA Network Open, researchers from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, report the results of a study of the two sterilization techniques on the pressure drop and filtration efficiency of N95, KN95, and surgical face masks.

“The H2O2 treatment showed a small effect on the overall filtration efficiency of the tested masks, but the ClO2 treatment showed marked reduction in the overall filtration efficiency of the KN95s and surgical face masks. All pressure drop changes were within the acceptable range,” the researchers write.

The study did not evaluate the effect of repeated sterilizations on face masks.

Five masks of each type were sterilized with either H2O2 or ClO2. Masks were then placed in a test chamber, and a salt aerosol was nebulized to assess both upstream and downstream filtration as well as pressure drop. The researchers used a mobility particle sizer to measure particle number concentration from 16.8 nm to 514 nm. An acceptable pressure drop was defined as a drop of less than 1.38 inches of water (35 mm) for inhalation.

Although pressure drop changes were within the acceptable range for all three mask types following sterilization with either method, H2O2 sterilization yielded the least reduction in filtration efficacy in all cases. After sterilization with H2O2, filtration efficiencies were 96.6%, 97.1%, and 91.6% for the N95s, KN95s, and the surgical face masks, respectively. In contrast, filtration efficiencies after ClO2 sterilization were 95.1%, 76.2%, and 77.9%, respectively.

The researchers note that, although overall filtration efficiency was maintained with ClO2 sterilization, there was a significant drop in efficiency with respect to particles of approximately 300 nm (0.3 microns) in size. For particles of that size, mean filtration efficiency decreased to 86.2% for N95s, 40.8% for KN95s, and 47.1% for surgical face masks.

The testing described in the report is “quite affordable at $350 per mask type, so it is hard to imagine any health care provider cannot set aside a small budget to conduct such an important test,” author Evan Floyd, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

Given the high demand for effective face masks and the current risk for counterfeit products, Floyd suggested that individual facilities test all masks intended for use by healthcare workers before and after sterilization procedures.

“However, if for some reason testing is not an option, we would recommend sticking to established brands and suppliers, perhaps reach out to your state health department or a local representative of the strategic stockpile of PPE,” he noted.

The authors acknowledge that further studies using a larger sample size and a greater variety of masks, as well as studies to evaluate different sterilization techniques, are required. Further, “measuring the respirator’s filtration efficiency by aerosol size instead of only measuring the overall filtration efficiency” should also be considered. Such an approach would enable researchers to evaluate the degree to which masks protect against specific infectious agents.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Daily Recap 6/17

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

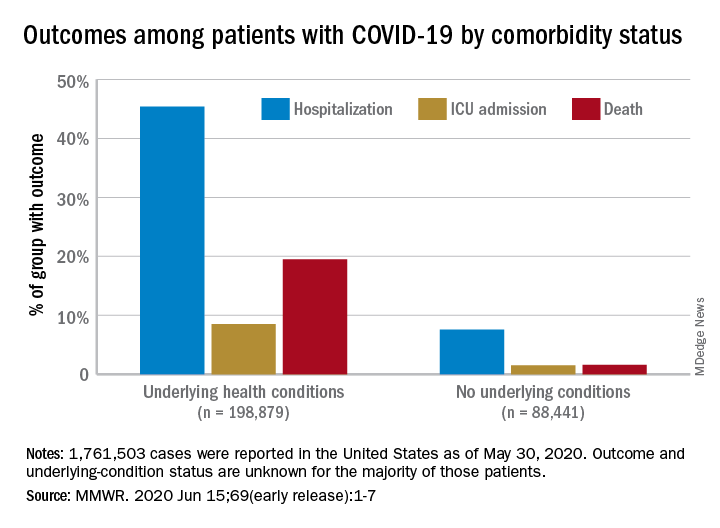

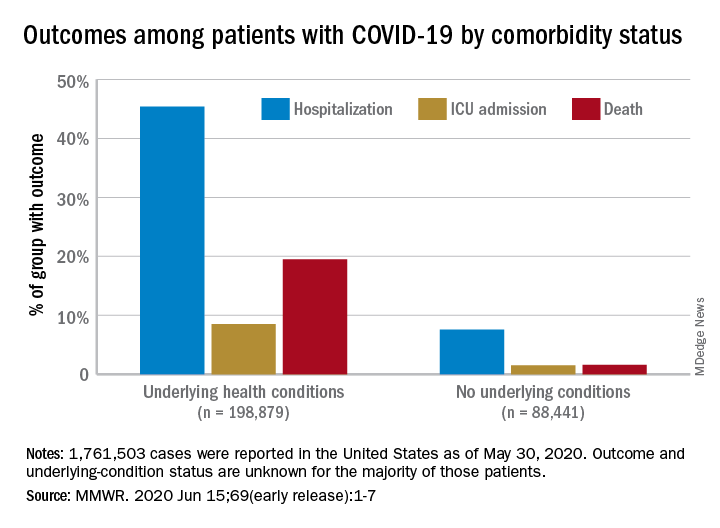

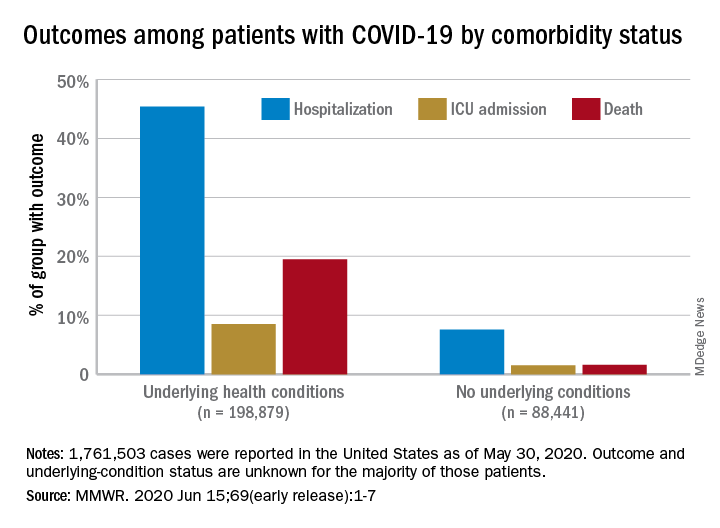

Comorbidities increase COVID-19 deaths by factor of 12

COVID-19 patients with an underlying condition are 6 times as likely to be hospitalized and 12 times as likely to die, compared with those who have no such condition, according to the CDC.

The most frequently reported underlying conditions were cardiovascular disease (32%), diabetes (30%), chronic lung disease (18%), and renal disease (7.6%), and there were no significant differences between males and females.

The pandemic “continues to affect all populations and result in severe outcomes including death,” noted the CDC, emphasizing “the continued need for community mitigation strategies, especially for vulnerable populations, to slow COVID-19 transmission.” Read more.

Preventive services coalition recommends routine anxiety screening for women

Women and girls aged 13 years and older with no current diagnosis of anxiety should be screened routinely for anxiety, according to a new recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in women in the United States is 40%, approximately twice that of men, and anxiety can be a manifestation of underlying issues including posttraumatic stress, sexual harassment, and assault.

“The WPSI based its rationale for anxiety screening on several considerations,” the researchers noted. “Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorders in women, and the problems created by untreated anxiety can impair function in all areas of a woman’s life.” Read more.

High-fat, high-sugar diet may promote adult acne

A diet higher in fat, sugar, and milk was associated with having acne in a cross-sectional study of approximately 24,000 adults in France.

Although acne patients may believe that eating certain foods exacerbates acne, data on the effects of nutrition on acne, including associations between acne and a high-glycemic diet, are limited and have produced conflicting results, noted investigators.

“The results of our study appear to support the hypothesis that the Western diet (rich in animal products and fatty and sugary foods) is associated with the presence of acne in adulthood,” the researchers concluded.

Population study supports migraine-dementia link

Preliminary results from a population-based cohort study support previous reports that migraine is a midlife risk factor for dementia later in life, but further determined that migraine with aura and frequent hospital contacts significantly increased dementia risk after age 60 years, according to results from a Danish registry presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The preliminary findings revealed that the median age at diagnosis was 49 years and about 70% of the migraine population were women. “There was a 50% higher dementia rate in individuals who had any migraine diagnosis,” Dr. Islamoska said.

“To the best of our knowledge, no previous national register–based studies have investigated the risk of dementia among individuals who suffer from migraine with aura,” Dr. Sabrina Islamoska said.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Comorbidities increase COVID-19 deaths by factor of 12

COVID-19 patients with an underlying condition are 6 times as likely to be hospitalized and 12 times as likely to die, compared with those who have no such condition, according to the CDC.

The most frequently reported underlying conditions were cardiovascular disease (32%), diabetes (30%), chronic lung disease (18%), and renal disease (7.6%), and there were no significant differences between males and females.

The pandemic “continues to affect all populations and result in severe outcomes including death,” noted the CDC, emphasizing “the continued need for community mitigation strategies, especially for vulnerable populations, to slow COVID-19 transmission.” Read more.

Preventive services coalition recommends routine anxiety screening for women

Women and girls aged 13 years and older with no current diagnosis of anxiety should be screened routinely for anxiety, according to a new recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in women in the United States is 40%, approximately twice that of men, and anxiety can be a manifestation of underlying issues including posttraumatic stress, sexual harassment, and assault.

“The WPSI based its rationale for anxiety screening on several considerations,” the researchers noted. “Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorders in women, and the problems created by untreated anxiety can impair function in all areas of a woman’s life.” Read more.

High-fat, high-sugar diet may promote adult acne

A diet higher in fat, sugar, and milk was associated with having acne in a cross-sectional study of approximately 24,000 adults in France.

Although acne patients may believe that eating certain foods exacerbates acne, data on the effects of nutrition on acne, including associations between acne and a high-glycemic diet, are limited and have produced conflicting results, noted investigators.

“The results of our study appear to support the hypothesis that the Western diet (rich in animal products and fatty and sugary foods) is associated with the presence of acne in adulthood,” the researchers concluded.

Population study supports migraine-dementia link

Preliminary results from a population-based cohort study support previous reports that migraine is a midlife risk factor for dementia later in life, but further determined that migraine with aura and frequent hospital contacts significantly increased dementia risk after age 60 years, according to results from a Danish registry presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The preliminary findings revealed that the median age at diagnosis was 49 years and about 70% of the migraine population were women. “There was a 50% higher dementia rate in individuals who had any migraine diagnosis,” Dr. Islamoska said.

“To the best of our knowledge, no previous national register–based studies have investigated the risk of dementia among individuals who suffer from migraine with aura,” Dr. Sabrina Islamoska said.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Comorbidities increase COVID-19 deaths by factor of 12

COVID-19 patients with an underlying condition are 6 times as likely to be hospitalized and 12 times as likely to die, compared with those who have no such condition, according to the CDC.

The most frequently reported underlying conditions were cardiovascular disease (32%), diabetes (30%), chronic lung disease (18%), and renal disease (7.6%), and there were no significant differences between males and females.

The pandemic “continues to affect all populations and result in severe outcomes including death,” noted the CDC, emphasizing “the continued need for community mitigation strategies, especially for vulnerable populations, to slow COVID-19 transmission.” Read more.

Preventive services coalition recommends routine anxiety screening for women

Women and girls aged 13 years and older with no current diagnosis of anxiety should be screened routinely for anxiety, according to a new recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in women in the United States is 40%, approximately twice that of men, and anxiety can be a manifestation of underlying issues including posttraumatic stress, sexual harassment, and assault.

“The WPSI based its rationale for anxiety screening on several considerations,” the researchers noted. “Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorders in women, and the problems created by untreated anxiety can impair function in all areas of a woman’s life.” Read more.

High-fat, high-sugar diet may promote adult acne

A diet higher in fat, sugar, and milk was associated with having acne in a cross-sectional study of approximately 24,000 adults in France.

Although acne patients may believe that eating certain foods exacerbates acne, data on the effects of nutrition on acne, including associations between acne and a high-glycemic diet, are limited and have produced conflicting results, noted investigators.

“The results of our study appear to support the hypothesis that the Western diet (rich in animal products and fatty and sugary foods) is associated with the presence of acne in adulthood,” the researchers concluded.

Population study supports migraine-dementia link

Preliminary results from a population-based cohort study support previous reports that migraine is a midlife risk factor for dementia later in life, but further determined that migraine with aura and frequent hospital contacts significantly increased dementia risk after age 60 years, according to results from a Danish registry presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The preliminary findings revealed that the median age at diagnosis was 49 years and about 70% of the migraine population were women. “There was a 50% higher dementia rate in individuals who had any migraine diagnosis,” Dr. Islamoska said.

“To the best of our knowledge, no previous national register–based studies have investigated the risk of dementia among individuals who suffer from migraine with aura,” Dr. Sabrina Islamoska said.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Hospitalist well-being during the pandemic

Navigating COVID-19 requires self-care

The global COVID-19 pandemic has escalated everyone’s stress levels, especially clinicians caring for hospitalized patients. New pressures have added to everyday stress, new studies have revised prior patient care recommendations, and the world generally seems upside down. What can a busy hospitalist do to maintain a modicum of sanity in all the craziness?

The stressors facing hospitalists

Uncertainty

Of all the burdens COVID-19 has unleashed, the biggest may be uncertainty. Not only is there unease about the virus itself, there also is legitimate concern about the future of medicine, said Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and senior director of clinical affairs at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora.

“What does it look like after an event like this, particularly in areas like academic medicine and teaching our next generation and getting funding for research? And how do we continue to produce physicians that can provide excellent care?” she asked.

There is also uncertainty in the best way to care for patients, said Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

“There are some models that are emerging to predict who will have a worse outcome, but they’re still not great models, so we have uncertainty for a given patient.” And, she noted, as the science continues to evolve, there exists a constant worry that “you might have inadvertently caused someone harm.”

The financial implications of the pandemic are creating uncertainty too. “When you fund a health care system with elective procedures and you can’t do those, and instead have to shift to the most essential services, a lot of places are seeing a massive deficit, which is going to affect staff morale and some physician offices are going to close,” said Elisabeth Poorman, MD, MPH, a primary care and internal medicine physician and chair of the King County Medical Society Physician Wellness Committee in Seattle.

Fear

When the pandemic began in the United States, “fear of the unknown was perhaps the scariest part, particularly as it pertained to personal protective equipment,” said Mark Rudolph, MD, SFHM, chief experience officer and vice president of patient experience and physician development at Sound Physicians in Tacoma, Wash. “For most clinicians, this is the first time that they are themselves in harm’s way while they do their jobs. And worse, they risk bringing the virus home to their families. That is the concern I hear most.”

Anxiety

Worrying about being able to provide excellent patient care is a big stressor, especially since this is the heart and soul of why most hospitalists have gone into their line of work.

“Part of providing excellent care to your patients is providing excellent supportive care to their families,” Dr. Harry said. “There’s some dissonance there in not being able to allow the family to come visit, but wanting to keep them safe, and it feels really hard to support your patients and support their families in the best way. It can feel like you’re just watching and waiting to see what will happen, and that we don’t have a lot of agency over which direction things take.”

There is concern for health care team members as well, Dr. Harry added. “Physicians care a lot about their teams and how they’re doing. I think there’s a sense of esprit de corps among folks and worry for each other there.”

Guilt

Although you may be at the hospital all day, you may feel guilty when you are not providing direct patient care. Or maybe you or someone on your team has an immunodeficiency and can’t be on the front line. Perhaps one of your team members contracted COVID-19 and you did not. Whatever the case, guilt is another emotion that is rampant among hospitalists right now, Dr. Barrett said.

Burnout

Unfortunately, burnout is a potential reality in times of high stress. “Burnout is dynamic,” said Dr. Poorman. “It’s a process by which your emotional and cognitive reserves are exhausted. The people with the highest burnout are the ones who are still trying to provide the standard of care, or above the standard of care in dysfunctional systems.”

Dr. Harry noted that burnout presents in different ways for different people, but Dr. Rudolph added that it’s crucial for hospitalist team members to watch for signs of burnout so they can intervene and/or get help for their colleagues.

Warning signs in yourself or others that burnout could be on the horizon include:

- Fatigue/exhaustion – Whether emotional or physical (or both), this can become a problem if it “just doesn’t seem to go away despite rest and time away from work,” said Dr. Rudolph.

- Behavioral changes – Any behavior that’s out of the ordinary may be a red flag, like lashing out at someone at work.

- Overwork – Working too much can be caused by an inability to let go of patient care, Dr. Barrett said.

- Not working enough – This may include avoiding tasks and having difficulty meeting deadlines.

- Maladaptive coping behaviors – Excessive consumption of alcohol or drugs is a common coping mechanism. “Even excessive consumption of news is something that people are using to numb out a little bit,” said Dr. Harry.

- Depersonalization – “This is where you start to look at patients, colleagues, or administrators as ‘them’ and you can’t connect as deeply,” Dr. Harry said. “Part of that’s protective and a normal thing to do during a big trauma like this, but it’s also incredibly distancing. Any language that people start using that feels like ‘us’ or ‘them’ is a warning sign.”

- Disengagement – Many people disengage from their work, but Dr. Poorman said physicians tend to disengage from other parts of their lives, such as exercise and family interaction.

Protecting yourself while supporting others

Like the illustration of putting the oxygen mask on yourself first so you can help others, it’s important to protect your own mental and physical health as you support your fellow physicians. Here’s what the experts suggest.

Focus on basic needs

“When you’re in the midst of a trauma, which we are, you don’t want to open all of that up and go to the depths of your thoughts about the grief of all of it because it can actually make the trauma worse,” said Dr. Harry. “There’s a lot of literature that debriefing is really helpful after the event, but if you do it during the event, it can be really dangerous.”

Instead, she said, the goal should be focusing on your basic needs and what you need to do to get through each day, like keeping you and your family in good health. “What is your purpose? Staying connected to why you do this and staying focused on the present is really important,” Dr. Harry noted.

Do your best to get a good night’s sleep, exercise as much as you can, talk to others, and see a mental health provider if your anxiety is too high, advises Dr. Barrett. “Even avoiding blue light from phones and screens within 2 hours of bedtime, parking further away from the hospital and walking, and taking the stairs are things that add up in a big way.”

Keep up your normal routine

“Right now, it’s really critical for clinicians to keep up components of their routine that feel ‘normal,’ ” Dr. Rudolph said. “Whether it’s exercise, playing board games with their kids, or spending time on a hobby, it’s critical to allow yourself these comfortable, predictable, and rewarding detours.”

Set limits

People under stress tend to find unhealthy ways to cope. Instead, try being intentional about what you are consuming by putting limits on things like your news, alcohol consumption, and the number of hours you work, said Dr. Harry.

Implement a culture of wellness

Dr. Barrett believes in creating the work culture we want to be in, one that ensures people have psychological safety, allows them to ask for help, encourages them to disconnect completely from work, and makes them feel valued and listened to. She likes the example of “the pause,” which is called by a team member right after a patient expires.

“It’s a 30-second moment of silence where we reflect on the patient, their loved ones, and every member of the health care team who helped support and treat them,” said Dr. Barrett. “At the conclusion, you say: ‘Thank you. Is there anything you need to be able to go back to the care of other patients?’ Because it’s unnatural to have this terrible thing that happened and then just act like nothing happened.”

Target resources

Be proactive and know where to find resources before you need them, advised Dr. Harry. “Most institutions have free mental health resources, either through their employee assistance programs or HR, plus there’s lots of national organizations that are offering free resources to health care providers.”

Focus on what you can control

Separating what is under your control from what is not is a struggle for everyone, Dr. Poorman said, but it’s helpful to think about the ways you can have an impact and what you’re able to control.

“There was a woman who was diagnosed with early-onset Parkinson’s that I heard giving an interview at the beginning of this pandemic,” she said. “It was the most helpful advice I got, which was: ‘Think of the next good thing you can do.’ You can’t fix everything, so what’s the next good thing you can do?”

Maintain connectivity

Make sure you are utilizing your support circle and staying connected. “That sense of connection is incredibly protective on multiple fronts for depression, for burnout, for suicide ideation, etc.,” Dr. Harry said.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s your teammates at work, your family at home, your best friend from medical school – whomever you can debrief with, vent with, and just share your thoughts and feelings with, these outlets are critical for all of us to process our emotions and diffuse stress and anxiety,” said Dr. Rudolph.

Dr. Poorman is concerned that there could be a spike in physician suicides caused by increased stress, so she also encourages talking openly about what is going on and about getting help when it’s necessary. “Many of us are afraid to seek care because we can actually have our ability to practice medicine questioned, but now is not the time for heroes. Now is the time for people who are willing to recognize their own strengths and limitations to take care of one another.”

Be compassionate toward others

Keep in mind that everyone is stressed out and offer empathy and compassion. “I think everybody’s struggling to try to figure this out and the more that we can give each other the benefit of the doubt and a little grace, the more protective that is,” said Dr. Harry.