User login

Does an early COPD diagnosis improve long-term outcomes?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Early Dx didn’t improve smoking cessation rates or treatment outcomes

A 2016 evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) identified no studies directly comparing the effectiveness of COPD screening on patient outcomes, so the authors looked first at studies on the outcomes of screening, followed by studies exploring the effects of early treatment.1

The authors identified 5 fair-quality RCTs (N = 1694) addressing the effect of screening asymptomatic patients for COPD with spirometry on the outcome of smoking cessation. One trial (n = 561) found better 12-month smoking cessation rates in patients who underwent spirometry screening and were given their “lung age” (13.6% vs 6.4% not given a lung age; P < .005; number needed to treat [NNT] = 14). However, a similar study (n = 542) published a year later found no significant difference in quit rates with or without “lung age” discussions (10.9% vs 13%, respectively; P not significant). In the other 3 studies, screening produced no significant effect on smoking cessation rates.1

As for possible early treatment benefits, the review authors identified only 1 RCT (n = 1175) that included any patients with mild COPD (defined as COPD with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] ≥ 80% of predicted normal value). It assessed treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in patients with mild COPD who continued to smoke. The trial did not record symptoms (if any) at intake. ICS therapy reduced the frequency of COPD exacerbations (relative risk = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-0.85), although patients with milder COPD benefitted little in absolute terms (by 0.02 exacerbations/year).1 The review authors further noted that data were insufficient to make definitive statements about the effect of ICS on dyspnea or health-related quality of life.

But later diagnosis is associated with poorer outcomes

Two recent, large retrospective observational cohort studies, however, have examined the impact of an early vs late COPD diagnosis in patients with dyspnea or other symptoms of COPD.2,3 A later diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes.

In the first study, researchers in Sweden identified patients older than 40 years who had received a new diagnosis of COPD between 2000 and 2014.2 They examined electronic health record data for 6 different “indicators” of COPD during the 5 years prior to date of diagnosis: pneumonia, other respiratory disease, oral steroids, antibiotics for respiratory infection, prescribed drugs for respiratory symptoms, and lung function measurement. Researchers categorized patients as early diagnosis (if they had ≤ 2 indicators prior to diagnosis) or late diagnosis (≥ 3 indicators prior to diagnosis). Compared with early diagnosis (n = 3870), late diagnosis (n = 8827) was associated with

- a higher annual rate of exacerbations within the first 2 years after diagnosis (2.67 vs 1.41; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.89; 95% CI, 1.83-1.96; P < .0001; number of early diagnoses needed to prevent 1 exacerbation in 1 year = 79),

- shorter time to first exacerbation (HR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.54-1.69; P < .0001), and

- higher direct health care costs (by €1500 per year; no P value given).

Mortality was not different between the groups (HR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.11; P = .18).

The second investigation was a similarly designed retrospective observational cohort study using a large UK database.3 Researchers enrolled patients who were at least 40 years old and received a new diagnosis of COPD between 2011 and 2014.

Continue to: Researchers examined electronic...

Researchers examined electronic health record data in the 5 years prior to diagnosis for 7 possible indicators of early COPD: pneumonia, respiratory disease other than pneumonia, chest radiograph, prescription of oral steroids, prescription of antibiotics for lung infection, prescription to manage respiratory disease symptoms, and lung function measurement. Researchers categorized patients as early diagnosis (≥ 2 indicators prior to diagnosis) or late diagnosis (≥ 3 indicators prior to diagnosis). Compared with early diagnosis (n = 3375), late diagnosis (n = 6783) was associated with a higher annual rate of exacerbations over 3-year follow-up (1.09 vs 0.57; adjusted HR = 1.68; 95% CI, 1.59-1.79; P < .0001; or 1 additional exacerbation in 192 patients in 1 year), shorter mean time to first exacerbation (HR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.38-1.55; P < .0001), and a higher risk of hospitalization within 3 years (rate ratio = 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28; P = .0001). The researchers did not evaluate for mortality.

Importantly, patients in the late COPD diagnosis group in both trials had higher rates of other severe illnesses that cause dyspnea, including cardiovascular disease and other pulmonary diseases. As a result, dyspnea of other etiologies may have contributed to both the later diagnoses and the poorer clinical outcomes of the late-diagnosis group. Both studies had a high risk of lead-time bias.

Recommendations from others

In 2016, the USPSTF gave a “D” rating (moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits) to screening asymptomatic adults without respiratory symptoms for COPD.4 Likewise, the 2017 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report did not recommend routine screening with spirometry but did advocate trying to make an accurate diagnosis using spirometry in patients with risk factors for COPD and chronic, progressive symptoms.5

Editor’s takeaway

Reasonably good evidence failed to find a benefit from an early COPD diagnosis. Even smoking cessation rates were not improved. Without better disease-modifying treatments, spirometry—the gold standard for confirming a COPD diagnosis—should not be used for screening asymptomatic patients.

1. Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:1378-1393. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2654

2. Larsson K, Janson C, Ställberg B, et al. Impact of COPD diagnosis timing on clinical and economic outcomes: the ARCTIC observational cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:995-1008. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S195382

3. Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical impact and healthcare resource utilization associated with early versus late COPD diagnosis in patients from UK CPRD database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729-1738. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S255414

4. US Preventive Services Task Force; Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:1372-1377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2638

5. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557-582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Early Dx didn’t improve smoking cessation rates or treatment outcomes

A 2016 evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) identified no studies directly comparing the effectiveness of COPD screening on patient outcomes, so the authors looked first at studies on the outcomes of screening, followed by studies exploring the effects of early treatment.1

The authors identified 5 fair-quality RCTs (N = 1694) addressing the effect of screening asymptomatic patients for COPD with spirometry on the outcome of smoking cessation. One trial (n = 561) found better 12-month smoking cessation rates in patients who underwent spirometry screening and were given their “lung age” (13.6% vs 6.4% not given a lung age; P < .005; number needed to treat [NNT] = 14). However, a similar study (n = 542) published a year later found no significant difference in quit rates with or without “lung age” discussions (10.9% vs 13%, respectively; P not significant). In the other 3 studies, screening produced no significant effect on smoking cessation rates.1

As for possible early treatment benefits, the review authors identified only 1 RCT (n = 1175) that included any patients with mild COPD (defined as COPD with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] ≥ 80% of predicted normal value). It assessed treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in patients with mild COPD who continued to smoke. The trial did not record symptoms (if any) at intake. ICS therapy reduced the frequency of COPD exacerbations (relative risk = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-0.85), although patients with milder COPD benefitted little in absolute terms (by 0.02 exacerbations/year).1 The review authors further noted that data were insufficient to make definitive statements about the effect of ICS on dyspnea or health-related quality of life.

But later diagnosis is associated with poorer outcomes

Two recent, large retrospective observational cohort studies, however, have examined the impact of an early vs late COPD diagnosis in patients with dyspnea or other symptoms of COPD.2,3 A later diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes.

In the first study, researchers in Sweden identified patients older than 40 years who had received a new diagnosis of COPD between 2000 and 2014.2 They examined electronic health record data for 6 different “indicators” of COPD during the 5 years prior to date of diagnosis: pneumonia, other respiratory disease, oral steroids, antibiotics for respiratory infection, prescribed drugs for respiratory symptoms, and lung function measurement. Researchers categorized patients as early diagnosis (if they had ≤ 2 indicators prior to diagnosis) or late diagnosis (≥ 3 indicators prior to diagnosis). Compared with early diagnosis (n = 3870), late diagnosis (n = 8827) was associated with

- a higher annual rate of exacerbations within the first 2 years after diagnosis (2.67 vs 1.41; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.89; 95% CI, 1.83-1.96; P < .0001; number of early diagnoses needed to prevent 1 exacerbation in 1 year = 79),

- shorter time to first exacerbation (HR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.54-1.69; P < .0001), and

- higher direct health care costs (by €1500 per year; no P value given).

Mortality was not different between the groups (HR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.11; P = .18).

The second investigation was a similarly designed retrospective observational cohort study using a large UK database.3 Researchers enrolled patients who were at least 40 years old and received a new diagnosis of COPD between 2011 and 2014.

Continue to: Researchers examined electronic...

Researchers examined electronic health record data in the 5 years prior to diagnosis for 7 possible indicators of early COPD: pneumonia, respiratory disease other than pneumonia, chest radiograph, prescription of oral steroids, prescription of antibiotics for lung infection, prescription to manage respiratory disease symptoms, and lung function measurement. Researchers categorized patients as early diagnosis (≥ 2 indicators prior to diagnosis) or late diagnosis (≥ 3 indicators prior to diagnosis). Compared with early diagnosis (n = 3375), late diagnosis (n = 6783) was associated with a higher annual rate of exacerbations over 3-year follow-up (1.09 vs 0.57; adjusted HR = 1.68; 95% CI, 1.59-1.79; P < .0001; or 1 additional exacerbation in 192 patients in 1 year), shorter mean time to first exacerbation (HR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.38-1.55; P < .0001), and a higher risk of hospitalization within 3 years (rate ratio = 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28; P = .0001). The researchers did not evaluate for mortality.

Importantly, patients in the late COPD diagnosis group in both trials had higher rates of other severe illnesses that cause dyspnea, including cardiovascular disease and other pulmonary diseases. As a result, dyspnea of other etiologies may have contributed to both the later diagnoses and the poorer clinical outcomes of the late-diagnosis group. Both studies had a high risk of lead-time bias.

Recommendations from others

In 2016, the USPSTF gave a “D” rating (moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits) to screening asymptomatic adults without respiratory symptoms for COPD.4 Likewise, the 2017 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report did not recommend routine screening with spirometry but did advocate trying to make an accurate diagnosis using spirometry in patients with risk factors for COPD and chronic, progressive symptoms.5

Editor’s takeaway

Reasonably good evidence failed to find a benefit from an early COPD diagnosis. Even smoking cessation rates were not improved. Without better disease-modifying treatments, spirometry—the gold standard for confirming a COPD diagnosis—should not be used for screening asymptomatic patients.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Early Dx didn’t improve smoking cessation rates or treatment outcomes

A 2016 evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) identified no studies directly comparing the effectiveness of COPD screening on patient outcomes, so the authors looked first at studies on the outcomes of screening, followed by studies exploring the effects of early treatment.1

The authors identified 5 fair-quality RCTs (N = 1694) addressing the effect of screening asymptomatic patients for COPD with spirometry on the outcome of smoking cessation. One trial (n = 561) found better 12-month smoking cessation rates in patients who underwent spirometry screening and were given their “lung age” (13.6% vs 6.4% not given a lung age; P < .005; number needed to treat [NNT] = 14). However, a similar study (n = 542) published a year later found no significant difference in quit rates with or without “lung age” discussions (10.9% vs 13%, respectively; P not significant). In the other 3 studies, screening produced no significant effect on smoking cessation rates.1

As for possible early treatment benefits, the review authors identified only 1 RCT (n = 1175) that included any patients with mild COPD (defined as COPD with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] ≥ 80% of predicted normal value). It assessed treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in patients with mild COPD who continued to smoke. The trial did not record symptoms (if any) at intake. ICS therapy reduced the frequency of COPD exacerbations (relative risk = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-0.85), although patients with milder COPD benefitted little in absolute terms (by 0.02 exacerbations/year).1 The review authors further noted that data were insufficient to make definitive statements about the effect of ICS on dyspnea or health-related quality of life.

But later diagnosis is associated with poorer outcomes

Two recent, large retrospective observational cohort studies, however, have examined the impact of an early vs late COPD diagnosis in patients with dyspnea or other symptoms of COPD.2,3 A later diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes.

In the first study, researchers in Sweden identified patients older than 40 years who had received a new diagnosis of COPD between 2000 and 2014.2 They examined electronic health record data for 6 different “indicators” of COPD during the 5 years prior to date of diagnosis: pneumonia, other respiratory disease, oral steroids, antibiotics for respiratory infection, prescribed drugs for respiratory symptoms, and lung function measurement. Researchers categorized patients as early diagnosis (if they had ≤ 2 indicators prior to diagnosis) or late diagnosis (≥ 3 indicators prior to diagnosis). Compared with early diagnosis (n = 3870), late diagnosis (n = 8827) was associated with

- a higher annual rate of exacerbations within the first 2 years after diagnosis (2.67 vs 1.41; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.89; 95% CI, 1.83-1.96; P < .0001; number of early diagnoses needed to prevent 1 exacerbation in 1 year = 79),

- shorter time to first exacerbation (HR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.54-1.69; P < .0001), and

- higher direct health care costs (by €1500 per year; no P value given).

Mortality was not different between the groups (HR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.11; P = .18).

The second investigation was a similarly designed retrospective observational cohort study using a large UK database.3 Researchers enrolled patients who were at least 40 years old and received a new diagnosis of COPD between 2011 and 2014.

Continue to: Researchers examined electronic...

Researchers examined electronic health record data in the 5 years prior to diagnosis for 7 possible indicators of early COPD: pneumonia, respiratory disease other than pneumonia, chest radiograph, prescription of oral steroids, prescription of antibiotics for lung infection, prescription to manage respiratory disease symptoms, and lung function measurement. Researchers categorized patients as early diagnosis (≥ 2 indicators prior to diagnosis) or late diagnosis (≥ 3 indicators prior to diagnosis). Compared with early diagnosis (n = 3375), late diagnosis (n = 6783) was associated with a higher annual rate of exacerbations over 3-year follow-up (1.09 vs 0.57; adjusted HR = 1.68; 95% CI, 1.59-1.79; P < .0001; or 1 additional exacerbation in 192 patients in 1 year), shorter mean time to first exacerbation (HR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.38-1.55; P < .0001), and a higher risk of hospitalization within 3 years (rate ratio = 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28; P = .0001). The researchers did not evaluate for mortality.

Importantly, patients in the late COPD diagnosis group in both trials had higher rates of other severe illnesses that cause dyspnea, including cardiovascular disease and other pulmonary diseases. As a result, dyspnea of other etiologies may have contributed to both the later diagnoses and the poorer clinical outcomes of the late-diagnosis group. Both studies had a high risk of lead-time bias.

Recommendations from others

In 2016, the USPSTF gave a “D” rating (moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits) to screening asymptomatic adults without respiratory symptoms for COPD.4 Likewise, the 2017 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report did not recommend routine screening with spirometry but did advocate trying to make an accurate diagnosis using spirometry in patients with risk factors for COPD and chronic, progressive symptoms.5

Editor’s takeaway

Reasonably good evidence failed to find a benefit from an early COPD diagnosis. Even smoking cessation rates were not improved. Without better disease-modifying treatments, spirometry—the gold standard for confirming a COPD diagnosis—should not be used for screening asymptomatic patients.

1. Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:1378-1393. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2654

2. Larsson K, Janson C, Ställberg B, et al. Impact of COPD diagnosis timing on clinical and economic outcomes: the ARCTIC observational cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:995-1008. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S195382

3. Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical impact and healthcare resource utilization associated with early versus late COPD diagnosis in patients from UK CPRD database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729-1738. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S255414

4. US Preventive Services Task Force; Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:1372-1377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2638

5. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557-582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP

1. Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:1378-1393. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2654

2. Larsson K, Janson C, Ställberg B, et al. Impact of COPD diagnosis timing on clinical and economic outcomes: the ARCTIC observational cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:995-1008. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S195382

3. Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical impact and healthcare resource utilization associated with early versus late COPD diagnosis in patients from UK CPRD database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729-1738. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S255414

4. US Preventive Services Task Force; Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:1372-1377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2638

5. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557-582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

It depends. A diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) made using screening spirometry in patients without symptoms does not change the course of the disease or alter smoking rates (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, preponderance of evidence from multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). However, once a patient develops symptoms of lung disease, a delayed diagnosis is associated with poorer outcomes (SOR: B, cohort studies). Active case finding (including the use of spirometry) is recommended for patients with risk factors for COPD who present with consistent symptoms (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Check biases when caring for children with obesity

Counting calories should not be the focus of weight-loss strategies for children with obesity, according to an expert who said pediatricians need to change the way they discuss weight with their patients.

During a plenary session of the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference, Joseph A. Skelton, MD, professor of pediatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., said pediatricians should recognize the behavioral, physical, environmental, and genetic factors that contribute to obesity. For instance, food deserts are on the rise, and they undermine the ability of parents to feed their children healthy meals. In addition, more children are less physically active.

“Obesity is a lot more complex than calories in, calories out,” Dr. Skelton said. “We choose to treat issues of obesity as personal responsibility – ‘you did this to yourself’ – but when you look at how we move around and live our lives, our food systems, our policies, the social and environmental changes have caused shifts in our behavior.”

According to Dr. Skelton, bias against children with obesity can harm their self-image and weaken their motivations for losing weight. In addition, doctors may change how they deliver care on the basis of stereotypes regarding obese children. These stereotypes are often reinforced in media portrayals, Dr. Skelton said.

“When children or when adults who have excess weight or obesity are portrayed, they are portrayed typically in a negative fashion,” Dr. Skelton said. “There’s increasing evidence that weight bias and weight discrimination are increasing the morbidity we see in patients who develop obesity.”

For many children with obesity, visits to the pediatrician often center on weight, regardless of the reason for the appointment. Weight stigma and bias on the part of health care providers can increase stress, as well as adverse health outcomes in children, according to a 2019 study (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000453). Dr. Skelton recommended that pediatricians listen to their patients’ concerns and make a personalized care plan.

Dr. Skelton said doctors can pull from projects such as Health at Every Size, which offers templates for personalized health plans for children with obesity. It has a heavy focus on a weight-neutral approach to pediatric health.

“There are various ways to manage weight in a healthy and safe way,” Dr. Skelton said.

Evidence-based methods of treating obesity include focusing on health and healthy behaviors rather than weight and using the body mass index as a screening tool for further conversations about overall health, rather than as an indicator of health based on weight.

Dr. Skelton also encouraged pediatricians to be on the alert for indicators of disordered eating, which can include dieting, teasing, or talking excessively about weight at home and can involve reading misinformation about dieting online.

“Your job is to educate people on the dangers of following unscientific information online,” Dr. Skelton said. “We can address issues of weight health in a way that is patient centered and is very safe, without unintended consequences.” Brooke Sweeney, MD, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at University of Missouri–Kansas City, said problems with weight bias in society and in clinical practice can lead to false assumptions about people who have obesity.

“It’s normal to gain adipose, or fat tissue, at different times in life, during puberty or pregnancy, and some people normally gain more weight than others,” Dr. Sweeney said.

The body will try to maintain a weight set point. That set point is influenced by many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

“When you lose weight, your body tries to get you back to the set point, decreasing energy expenditure and increasing hunger and reward pathways,” she said. “We have gained so much knowledge through research to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity, and we are making good progress on improving advanced treatments for increased weight in children.”

Dr. Skelton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Counting calories should not be the focus of weight-loss strategies for children with obesity, according to an expert who said pediatricians need to change the way they discuss weight with their patients.

During a plenary session of the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference, Joseph A. Skelton, MD, professor of pediatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., said pediatricians should recognize the behavioral, physical, environmental, and genetic factors that contribute to obesity. For instance, food deserts are on the rise, and they undermine the ability of parents to feed their children healthy meals. In addition, more children are less physically active.

“Obesity is a lot more complex than calories in, calories out,” Dr. Skelton said. “We choose to treat issues of obesity as personal responsibility – ‘you did this to yourself’ – but when you look at how we move around and live our lives, our food systems, our policies, the social and environmental changes have caused shifts in our behavior.”

According to Dr. Skelton, bias against children with obesity can harm their self-image and weaken their motivations for losing weight. In addition, doctors may change how they deliver care on the basis of stereotypes regarding obese children. These stereotypes are often reinforced in media portrayals, Dr. Skelton said.

“When children or when adults who have excess weight or obesity are portrayed, they are portrayed typically in a negative fashion,” Dr. Skelton said. “There’s increasing evidence that weight bias and weight discrimination are increasing the morbidity we see in patients who develop obesity.”

For many children with obesity, visits to the pediatrician often center on weight, regardless of the reason for the appointment. Weight stigma and bias on the part of health care providers can increase stress, as well as adverse health outcomes in children, according to a 2019 study (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000453). Dr. Skelton recommended that pediatricians listen to their patients’ concerns and make a personalized care plan.

Dr. Skelton said doctors can pull from projects such as Health at Every Size, which offers templates for personalized health plans for children with obesity. It has a heavy focus on a weight-neutral approach to pediatric health.

“There are various ways to manage weight in a healthy and safe way,” Dr. Skelton said.

Evidence-based methods of treating obesity include focusing on health and healthy behaviors rather than weight and using the body mass index as a screening tool for further conversations about overall health, rather than as an indicator of health based on weight.

Dr. Skelton also encouraged pediatricians to be on the alert for indicators of disordered eating, which can include dieting, teasing, or talking excessively about weight at home and can involve reading misinformation about dieting online.

“Your job is to educate people on the dangers of following unscientific information online,” Dr. Skelton said. “We can address issues of weight health in a way that is patient centered and is very safe, without unintended consequences.” Brooke Sweeney, MD, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at University of Missouri–Kansas City, said problems with weight bias in society and in clinical practice can lead to false assumptions about people who have obesity.

“It’s normal to gain adipose, or fat tissue, at different times in life, during puberty or pregnancy, and some people normally gain more weight than others,” Dr. Sweeney said.

The body will try to maintain a weight set point. That set point is influenced by many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

“When you lose weight, your body tries to get you back to the set point, decreasing energy expenditure and increasing hunger and reward pathways,” she said. “We have gained so much knowledge through research to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity, and we are making good progress on improving advanced treatments for increased weight in children.”

Dr. Skelton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Counting calories should not be the focus of weight-loss strategies for children with obesity, according to an expert who said pediatricians need to change the way they discuss weight with their patients.

During a plenary session of the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference, Joseph A. Skelton, MD, professor of pediatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., said pediatricians should recognize the behavioral, physical, environmental, and genetic factors that contribute to obesity. For instance, food deserts are on the rise, and they undermine the ability of parents to feed their children healthy meals. In addition, more children are less physically active.

“Obesity is a lot more complex than calories in, calories out,” Dr. Skelton said. “We choose to treat issues of obesity as personal responsibility – ‘you did this to yourself’ – but when you look at how we move around and live our lives, our food systems, our policies, the social and environmental changes have caused shifts in our behavior.”

According to Dr. Skelton, bias against children with obesity can harm their self-image and weaken their motivations for losing weight. In addition, doctors may change how they deliver care on the basis of stereotypes regarding obese children. These stereotypes are often reinforced in media portrayals, Dr. Skelton said.

“When children or when adults who have excess weight or obesity are portrayed, they are portrayed typically in a negative fashion,” Dr. Skelton said. “There’s increasing evidence that weight bias and weight discrimination are increasing the morbidity we see in patients who develop obesity.”

For many children with obesity, visits to the pediatrician often center on weight, regardless of the reason for the appointment. Weight stigma and bias on the part of health care providers can increase stress, as well as adverse health outcomes in children, according to a 2019 study (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000453). Dr. Skelton recommended that pediatricians listen to their patients’ concerns and make a personalized care plan.

Dr. Skelton said doctors can pull from projects such as Health at Every Size, which offers templates for personalized health plans for children with obesity. It has a heavy focus on a weight-neutral approach to pediatric health.

“There are various ways to manage weight in a healthy and safe way,” Dr. Skelton said.

Evidence-based methods of treating obesity include focusing on health and healthy behaviors rather than weight and using the body mass index as a screening tool for further conversations about overall health, rather than as an indicator of health based on weight.

Dr. Skelton also encouraged pediatricians to be on the alert for indicators of disordered eating, which can include dieting, teasing, or talking excessively about weight at home and can involve reading misinformation about dieting online.

“Your job is to educate people on the dangers of following unscientific information online,” Dr. Skelton said. “We can address issues of weight health in a way that is patient centered and is very safe, without unintended consequences.” Brooke Sweeney, MD, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at University of Missouri–Kansas City, said problems with weight bias in society and in clinical practice can lead to false assumptions about people who have obesity.

“It’s normal to gain adipose, or fat tissue, at different times in life, during puberty or pregnancy, and some people normally gain more weight than others,” Dr. Sweeney said.

The body will try to maintain a weight set point. That set point is influenced by many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

“When you lose weight, your body tries to get you back to the set point, decreasing energy expenditure and increasing hunger and reward pathways,” she said. “We have gained so much knowledge through research to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity, and we are making good progress on improving advanced treatments for increased weight in children.”

Dr. Skelton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAP 2022

A “no-biopsy” approach to diagnosing celiac disease

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 43-year-old woman presents to the clinic with diffuse, intermittent abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea that has slowly but steadily worsened over the past few years to now-daily symptoms. She states her overall health is otherwise good. Her review of systems is pertinent only for 8 lbs of unintentional weight loss over the past year and increased fatigue. She takes no supplements or routine over-the-counter or prescription medications, except for low-dose combination oral contraceptives, and is unaware of any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. She does not drink or smoke. She is up to date with immunizations and with cervical and breast cancer screening. Her body mass index is 23, her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam is normal except for mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness without any masses, organomegaly, or peritoneal signs.

Her diagnostic work-up includes a complete metabolic panel, magnesium level, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, cytomegalovirus IgG and IgM serology, and stool studies for fecal leukocytes, ova and parasites, and fecal fat, in addition to a kidney, ureter, and bladder noncontrast computed tomography scan. All diagnostic testing is negative except for slightly elevated fecal fat, thereby decreasing the likelihood of infection, thyroid disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, or malignancy as a source of her symptoms.

She says that based on her online searches, her symptoms seem consistent with CD—with which you concur. However, she is fearful of an endoscopic procedure and asks if there is any other way to diagnose CD.

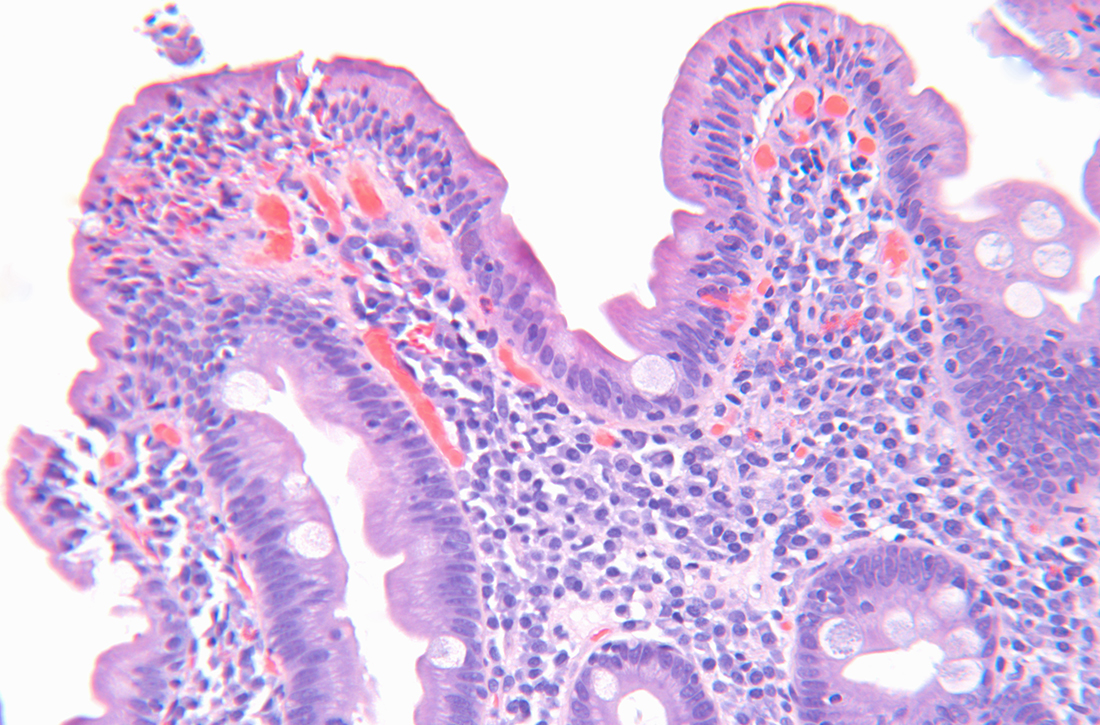

CD is an immune-mediated disorder in genetically susceptible people that is triggered by dietary gluten, causing damage to the small intestine.1-6 The estimated worldwide prevalence of CD is approximately 1%, with greater prevalence in females.1-6 A strong genetic predisposition also has been noted: prevalence among first-degree relatives is 10% to 44%.2,3,6 Although CD can be diagnosed at any age, in the United States the mean age at diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life.6

The incidence of CD is on the rise due to true increases in disease incidence and prevalence, increased detection through better diagnostic tools, and increased screening of at-risk populations (eg, first-degree relatives, those with specific human leukocyte antigen variant genotypes, and those with certain chromosomal disorders, such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome).2-6 However, despite the increasing prevalence of CD, most patients remain undiagnosed.1

The diagnosis of CD in adults is typically made with elevated serum tTG-IgA and

STUDY SUMMARY

tTG-IgA titers were highly predictive of CD in 3 distinct cohorts

This 2021 hybrid prospective/retrospective study with 3 distinct cohorts aimed to assess the utility of serum tTG-IgA titers compared to traditional EGD with duodenal biopsy for the diagnosis of CD in adult participants (defined as ≥ 16 years of age). A serum tTG-IgA titer ≥ 10 times the ULN was set as the minimal cutoff value, and standardized duodenal biopsy sampling and evaluation for histologic mucosal changes consistent with

Continue to: Cohort 1 was a...

Cohort 1 was a prospective analysis of adults (N = 740) considered to have a high suspicion for CD, recruited from a single CD subspecialty clinic in the United Kingdom. Patients with a previous diagnosis of CD, those adhering to a gluten-free diet, and those with IgA deficiency were excluded. Study patients had tTG-IgA titers drawn and, within 6 weeks, underwent endoscopy with ≥ 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb and/or the second part of the duodenum. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 98.7% (95% CI, 97%-99.4%).

Cohort 2 was a retrospective analysis of adult patients (N = 532) considered to have low suspicion for CD. These patients were referred for endoscopy for generalized GI complaints in the same hospital as Cohort 1, but not the subspecialty clinic. Exclusion criteria and timing of IgA titers and endoscopy were identical to those of Cohort 1. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 100%.

Cohort 3 (which included patients in 8 countries) was a retrospective analysis of the performance of multiple assays to enhance the validity of this approach in a wide range of settings. Adult patients (N = 145) with tTG-IgA serology positive for celiac who then underwent endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsy samples were included in this analysis. Eleven distinct laboratories performed the tTG-IgA assay. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 95.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-98.6%).

In total, this study included 1417 adult patients; 431 (30%) had tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN. Of those patients, 424 (98%) had histopathologic findings on duodenal biopsy consistent with CD.

Of note, there was no standardization as to the assays used for the tTG-IgA titers: Cohort 1 used 2 different manufacturers’ assays, Cohort 2 used 1 assay, and Cohort 3 used 5 assays. Regardless, the “≥ 10 times the ULN” calculation was based on each manufacturer’s published assay ranges. The lack of assay standardization did create variance in false-positive rates, however: Across all 3 cohorts, the false-positive rate for trusting the “≥ 10 times the ULN” threshold as the sole marker for CD in adults increased from 1% (Cohorts 1 and 2) to 5% (all 3 cohorts).

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Less invasive, less costly diagnosis of celiac disease in adults

In adults with symptoms suggestive of CD, the diagnosis can be made with a high level of certainty if a serum tTG-IgA titer is ≥ 10 times the ULN. Through informed, shared decision making in the presence of such a finding, patients may accept a serologic diagnosis and forgo an invasive EGD with biopsy and its inherent costs and risks. Indeed, if the majority of patients with CD are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed, and there exists a minimally invasive blood test that is highly cost effective in the absence of “red flags,” the overall benefit of this path could be substantial.

CAVEATS

“No biopsy” does not mean no risk/benefit discussion

While the PPVs are quite high, the negative predictive value varied greatly: 13%, 98%, and 10% for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, although serum tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN are useful for diagnosis, a negative result (serum tTG-IgA titers < 10 times the ULN) should not be used to rule out CD, and other testing should be pursued.

Additionally (although rare), patients with CD who have IgA deficiency may obtain false-negative results using the tTG-IgA ≥ 10 times the ULN diagnostic criterion.7,8

Also, both Cohorts 1 and 2 took place in general or subspecialty GI clinics (Cohort 3’s site types were not specified). However, the objective interpretation of tTG-IgA serology means it could be considered as an additional diagnostic tool for primary care physicians, as well.

Finally, if a primary care physician and their patient decide to go the “no-biopsy” route, it should be with a full discussion of the possible risks and benefits of not pursuing EGD. If there are any potential “red flag” symptoms suggesting the possibility of a more concerning differential diagnosis, EGD evaluation should still be pursued. Such symptoms might include (but not be limited to) chronic dyspepsia, dysphagia, weight loss, and unexplained anemia.7

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Diagnostic guidelines still favor EGD with biopsy for adults

The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines support the use of EGD and duodenal biopsy to diagnose CD in both low- and high-risk patients, regardless of serologic findings.7 In a 2019 Clinical Practice Update, the American Gastrointestinal Association (AGA) stated that when tTG-IgA titers are ≥ 10 times the ULN and EMAs are positive, the PPV is “virtually 100%” for CD. Yet they still state that in this scenario “EGD and duodenal biopsies may then be performed for purposes of differential diagnosis.”8 Furthermore, the AGA does not discuss informed and shared decision making with patients for the option of a “no-biopsy” diagnosis.8

Additionally, there may be challenges in finding commercial laboratories that report reference ranges with a clear ULN. Although costs for the serum tTG-IgA assay vary, they are less expensive than endoscopy with biopsy and histopathologic examination, and therefore may present less of a financial barrier.

1. Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

2. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125

3. Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z

4. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

5. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391:70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

6. Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070

7. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79

8. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:885-889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

9. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 43-year-old woman presents to the clinic with diffuse, intermittent abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea that has slowly but steadily worsened over the past few years to now-daily symptoms. She states her overall health is otherwise good. Her review of systems is pertinent only for 8 lbs of unintentional weight loss over the past year and increased fatigue. She takes no supplements or routine over-the-counter or prescription medications, except for low-dose combination oral contraceptives, and is unaware of any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. She does not drink or smoke. She is up to date with immunizations and with cervical and breast cancer screening. Her body mass index is 23, her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam is normal except for mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness without any masses, organomegaly, or peritoneal signs.

Her diagnostic work-up includes a complete metabolic panel, magnesium level, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, cytomegalovirus IgG and IgM serology, and stool studies for fecal leukocytes, ova and parasites, and fecal fat, in addition to a kidney, ureter, and bladder noncontrast computed tomography scan. All diagnostic testing is negative except for slightly elevated fecal fat, thereby decreasing the likelihood of infection, thyroid disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, or malignancy as a source of her symptoms.

She says that based on her online searches, her symptoms seem consistent with CD—with which you concur. However, she is fearful of an endoscopic procedure and asks if there is any other way to diagnose CD.

CD is an immune-mediated disorder in genetically susceptible people that is triggered by dietary gluten, causing damage to the small intestine.1-6 The estimated worldwide prevalence of CD is approximately 1%, with greater prevalence in females.1-6 A strong genetic predisposition also has been noted: prevalence among first-degree relatives is 10% to 44%.2,3,6 Although CD can be diagnosed at any age, in the United States the mean age at diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life.6

The incidence of CD is on the rise due to true increases in disease incidence and prevalence, increased detection through better diagnostic tools, and increased screening of at-risk populations (eg, first-degree relatives, those with specific human leukocyte antigen variant genotypes, and those with certain chromosomal disorders, such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome).2-6 However, despite the increasing prevalence of CD, most patients remain undiagnosed.1

The diagnosis of CD in adults is typically made with elevated serum tTG-IgA and

STUDY SUMMARY

tTG-IgA titers were highly predictive of CD in 3 distinct cohorts

This 2021 hybrid prospective/retrospective study with 3 distinct cohorts aimed to assess the utility of serum tTG-IgA titers compared to traditional EGD with duodenal biopsy for the diagnosis of CD in adult participants (defined as ≥ 16 years of age). A serum tTG-IgA titer ≥ 10 times the ULN was set as the minimal cutoff value, and standardized duodenal biopsy sampling and evaluation for histologic mucosal changes consistent with

Continue to: Cohort 1 was a...

Cohort 1 was a prospective analysis of adults (N = 740) considered to have a high suspicion for CD, recruited from a single CD subspecialty clinic in the United Kingdom. Patients with a previous diagnosis of CD, those adhering to a gluten-free diet, and those with IgA deficiency were excluded. Study patients had tTG-IgA titers drawn and, within 6 weeks, underwent endoscopy with ≥ 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb and/or the second part of the duodenum. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 98.7% (95% CI, 97%-99.4%).

Cohort 2 was a retrospective analysis of adult patients (N = 532) considered to have low suspicion for CD. These patients were referred for endoscopy for generalized GI complaints in the same hospital as Cohort 1, but not the subspecialty clinic. Exclusion criteria and timing of IgA titers and endoscopy were identical to those of Cohort 1. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 100%.

Cohort 3 (which included patients in 8 countries) was a retrospective analysis of the performance of multiple assays to enhance the validity of this approach in a wide range of settings. Adult patients (N = 145) with tTG-IgA serology positive for celiac who then underwent endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsy samples were included in this analysis. Eleven distinct laboratories performed the tTG-IgA assay. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 95.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-98.6%).

In total, this study included 1417 adult patients; 431 (30%) had tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN. Of those patients, 424 (98%) had histopathologic findings on duodenal biopsy consistent with CD.

Of note, there was no standardization as to the assays used for the tTG-IgA titers: Cohort 1 used 2 different manufacturers’ assays, Cohort 2 used 1 assay, and Cohort 3 used 5 assays. Regardless, the “≥ 10 times the ULN” calculation was based on each manufacturer’s published assay ranges. The lack of assay standardization did create variance in false-positive rates, however: Across all 3 cohorts, the false-positive rate for trusting the “≥ 10 times the ULN” threshold as the sole marker for CD in adults increased from 1% (Cohorts 1 and 2) to 5% (all 3 cohorts).

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Less invasive, less costly diagnosis of celiac disease in adults

In adults with symptoms suggestive of CD, the diagnosis can be made with a high level of certainty if a serum tTG-IgA titer is ≥ 10 times the ULN. Through informed, shared decision making in the presence of such a finding, patients may accept a serologic diagnosis and forgo an invasive EGD with biopsy and its inherent costs and risks. Indeed, if the majority of patients with CD are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed, and there exists a minimally invasive blood test that is highly cost effective in the absence of “red flags,” the overall benefit of this path could be substantial.

CAVEATS

“No biopsy” does not mean no risk/benefit discussion

While the PPVs are quite high, the negative predictive value varied greatly: 13%, 98%, and 10% for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, although serum tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN are useful for diagnosis, a negative result (serum tTG-IgA titers < 10 times the ULN) should not be used to rule out CD, and other testing should be pursued.

Additionally (although rare), patients with CD who have IgA deficiency may obtain false-negative results using the tTG-IgA ≥ 10 times the ULN diagnostic criterion.7,8

Also, both Cohorts 1 and 2 took place in general or subspecialty GI clinics (Cohort 3’s site types were not specified). However, the objective interpretation of tTG-IgA serology means it could be considered as an additional diagnostic tool for primary care physicians, as well.

Finally, if a primary care physician and their patient decide to go the “no-biopsy” route, it should be with a full discussion of the possible risks and benefits of not pursuing EGD. If there are any potential “red flag” symptoms suggesting the possibility of a more concerning differential diagnosis, EGD evaluation should still be pursued. Such symptoms might include (but not be limited to) chronic dyspepsia, dysphagia, weight loss, and unexplained anemia.7

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Diagnostic guidelines still favor EGD with biopsy for adults

The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines support the use of EGD and duodenal biopsy to diagnose CD in both low- and high-risk patients, regardless of serologic findings.7 In a 2019 Clinical Practice Update, the American Gastrointestinal Association (AGA) stated that when tTG-IgA titers are ≥ 10 times the ULN and EMAs are positive, the PPV is “virtually 100%” for CD. Yet they still state that in this scenario “EGD and duodenal biopsies may then be performed for purposes of differential diagnosis.”8 Furthermore, the AGA does not discuss informed and shared decision making with patients for the option of a “no-biopsy” diagnosis.8

Additionally, there may be challenges in finding commercial laboratories that report reference ranges with a clear ULN. Although costs for the serum tTG-IgA assay vary, they are less expensive than endoscopy with biopsy and histopathologic examination, and therefore may present less of a financial barrier.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 43-year-old woman presents to the clinic with diffuse, intermittent abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea that has slowly but steadily worsened over the past few years to now-daily symptoms. She states her overall health is otherwise good. Her review of systems is pertinent only for 8 lbs of unintentional weight loss over the past year and increased fatigue. She takes no supplements or routine over-the-counter or prescription medications, except for low-dose combination oral contraceptives, and is unaware of any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. She does not drink or smoke. She is up to date with immunizations and with cervical and breast cancer screening. Her body mass index is 23, her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam is normal except for mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness without any masses, organomegaly, or peritoneal signs.

Her diagnostic work-up includes a complete metabolic panel, magnesium level, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, cytomegalovirus IgG and IgM serology, and stool studies for fecal leukocytes, ova and parasites, and fecal fat, in addition to a kidney, ureter, and bladder noncontrast computed tomography scan. All diagnostic testing is negative except for slightly elevated fecal fat, thereby decreasing the likelihood of infection, thyroid disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, or malignancy as a source of her symptoms.

She says that based on her online searches, her symptoms seem consistent with CD—with which you concur. However, she is fearful of an endoscopic procedure and asks if there is any other way to diagnose CD.

CD is an immune-mediated disorder in genetically susceptible people that is triggered by dietary gluten, causing damage to the small intestine.1-6 The estimated worldwide prevalence of CD is approximately 1%, with greater prevalence in females.1-6 A strong genetic predisposition also has been noted: prevalence among first-degree relatives is 10% to 44%.2,3,6 Although CD can be diagnosed at any age, in the United States the mean age at diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life.6

The incidence of CD is on the rise due to true increases in disease incidence and prevalence, increased detection through better diagnostic tools, and increased screening of at-risk populations (eg, first-degree relatives, those with specific human leukocyte antigen variant genotypes, and those with certain chromosomal disorders, such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome).2-6 However, despite the increasing prevalence of CD, most patients remain undiagnosed.1

The diagnosis of CD in adults is typically made with elevated serum tTG-IgA and

STUDY SUMMARY

tTG-IgA titers were highly predictive of CD in 3 distinct cohorts

This 2021 hybrid prospective/retrospective study with 3 distinct cohorts aimed to assess the utility of serum tTG-IgA titers compared to traditional EGD with duodenal biopsy for the diagnosis of CD in adult participants (defined as ≥ 16 years of age). A serum tTG-IgA titer ≥ 10 times the ULN was set as the minimal cutoff value, and standardized duodenal biopsy sampling and evaluation for histologic mucosal changes consistent with

Continue to: Cohort 1 was a...

Cohort 1 was a prospective analysis of adults (N = 740) considered to have a high suspicion for CD, recruited from a single CD subspecialty clinic in the United Kingdom. Patients with a previous diagnosis of CD, those adhering to a gluten-free diet, and those with IgA deficiency were excluded. Study patients had tTG-IgA titers drawn and, within 6 weeks, underwent endoscopy with ≥ 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb and/or the second part of the duodenum. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 98.7% (95% CI, 97%-99.4%).

Cohort 2 was a retrospective analysis of adult patients (N = 532) considered to have low suspicion for CD. These patients were referred for endoscopy for generalized GI complaints in the same hospital as Cohort 1, but not the subspecialty clinic. Exclusion criteria and timing of IgA titers and endoscopy were identical to those of Cohort 1. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 100%.

Cohort 3 (which included patients in 8 countries) was a retrospective analysis of the performance of multiple assays to enhance the validity of this approach in a wide range of settings. Adult patients (N = 145) with tTG-IgA serology positive for celiac who then underwent endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsy samples were included in this analysis. Eleven distinct laboratories performed the tTG-IgA assay. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 95.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-98.6%).

In total, this study included 1417 adult patients; 431 (30%) had tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN. Of those patients, 424 (98%) had histopathologic findings on duodenal biopsy consistent with CD.

Of note, there was no standardization as to the assays used for the tTG-IgA titers: Cohort 1 used 2 different manufacturers’ assays, Cohort 2 used 1 assay, and Cohort 3 used 5 assays. Regardless, the “≥ 10 times the ULN” calculation was based on each manufacturer’s published assay ranges. The lack of assay standardization did create variance in false-positive rates, however: Across all 3 cohorts, the false-positive rate for trusting the “≥ 10 times the ULN” threshold as the sole marker for CD in adults increased from 1% (Cohorts 1 and 2) to 5% (all 3 cohorts).

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Less invasive, less costly diagnosis of celiac disease in adults

In adults with symptoms suggestive of CD, the diagnosis can be made with a high level of certainty if a serum tTG-IgA titer is ≥ 10 times the ULN. Through informed, shared decision making in the presence of such a finding, patients may accept a serologic diagnosis and forgo an invasive EGD with biopsy and its inherent costs and risks. Indeed, if the majority of patients with CD are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed, and there exists a minimally invasive blood test that is highly cost effective in the absence of “red flags,” the overall benefit of this path could be substantial.

CAVEATS

“No biopsy” does not mean no risk/benefit discussion

While the PPVs are quite high, the negative predictive value varied greatly: 13%, 98%, and 10% for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, although serum tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN are useful for diagnosis, a negative result (serum tTG-IgA titers < 10 times the ULN) should not be used to rule out CD, and other testing should be pursued.

Additionally (although rare), patients with CD who have IgA deficiency may obtain false-negative results using the tTG-IgA ≥ 10 times the ULN diagnostic criterion.7,8

Also, both Cohorts 1 and 2 took place in general or subspecialty GI clinics (Cohort 3’s site types were not specified). However, the objective interpretation of tTG-IgA serology means it could be considered as an additional diagnostic tool for primary care physicians, as well.

Finally, if a primary care physician and their patient decide to go the “no-biopsy” route, it should be with a full discussion of the possible risks and benefits of not pursuing EGD. If there are any potential “red flag” symptoms suggesting the possibility of a more concerning differential diagnosis, EGD evaluation should still be pursued. Such symptoms might include (but not be limited to) chronic dyspepsia, dysphagia, weight loss, and unexplained anemia.7

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Diagnostic guidelines still favor EGD with biopsy for adults

The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines support the use of EGD and duodenal biopsy to diagnose CD in both low- and high-risk patients, regardless of serologic findings.7 In a 2019 Clinical Practice Update, the American Gastrointestinal Association (AGA) stated that when tTG-IgA titers are ≥ 10 times the ULN and EMAs are positive, the PPV is “virtually 100%” for CD. Yet they still state that in this scenario “EGD and duodenal biopsies may then be performed for purposes of differential diagnosis.”8 Furthermore, the AGA does not discuss informed and shared decision making with patients for the option of a “no-biopsy” diagnosis.8

Additionally, there may be challenges in finding commercial laboratories that report reference ranges with a clear ULN. Although costs for the serum tTG-IgA assay vary, they are less expensive than endoscopy with biopsy and histopathologic examination, and therefore may present less of a financial barrier.

1. Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

2. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125

3. Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z

4. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

5. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391:70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

6. Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070

7. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79

8. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:885-889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

9. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

1. Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

2. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125

3. Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z

4. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

5. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391:70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

6. Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070

7. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79

8. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:885-889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

9. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider a “no-biopsy” approach by evaluating serum immunoglobulin (Ig) A anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) antibody titers in adult patients who present with symptoms concerning for celiac disease (CD). An increase of ≥ 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) for tTG-IgA has a positive predictive value (PPV) of ≥ 95% for diagnosing CD when compared with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with duodenal biopsy—the current gold standard.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Consistent findings from 3 good-quality diagnostic cohorts presented in a single study.1

Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

COVID-19 vaccine insights: The news beyond the headlines

Worldwide and across many diseases, vaccines have been transformative in reducing mortality—an effect that has been sustained with vaccines that protect against COVID-19.1 Since the first cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported in late 2019, the pace of scientific investigation into the virus and the disease—made possible by unprecedented funding, infrastructure, and public and private partnerships—has been explosive. The result? A vast body of clinical and laboratory evidence about the safety and effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, which quickly became widely available.2-4

In this article, we review the basic underlying virology of SARS-CoV-2; the biotechnological basis of vaccines against COVID-19 that are available in the United States; and recommendations on how to provide those vaccines to your patients. Additional guidance for your practice appears in a select online bibliography, “COVID-19 vaccination resources.”

SIDEBAR

COVID-19 vaccination resources

Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently approved or authorized in the United States

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interimconsiderations-us.html

COVID-19 ACIP vaccine recommendations

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/covid-19.html

MMWR COVID-19 reports

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

www.cdc.gov/mmwr/Novel_Coronavirus_Reports.html

A literature hub for tracking up-to-date scientific information about the 2019 novel coronavirus

National Center for Biotechnology Information of the National Library of Medicine

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/coronavirus

Understanding COVID-19 vaccines

National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Research

https://covid19.nih.gov/treatments-and-vaccines/covid-19-vaccines

How COVID-19 affects pregnancy

National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Research

SARS-CoV-2 virology

As the SARS-CoV-2 virus approaches the host cell, normal cell proteases on the surface membrane cause a change in the shape of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. That spike protein conformation change allows the virus to avoid detection by the host’s immune system because its receptor-binding site is effectively hidden until just before entry into the cell.5,6 This process is analogous to a so-called lock-and-key method of entry, in which the key (ie, spike protein conformation) is hidden by the virus until the moment it is needed, thereby minimizing exposure of viral contents to the cell. As the virus spreads through the population, it adapts to improve infectivity and transmissibility and to evade developing immunity.7

After the spike protein changes shape, it attaches to an angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor on the host cell, allowing the virus to enter that cell. ACE-2 receptors are located in numerous human tissues: nasopharynx, lung, gastrointestinal tract, heart, thymus, lymph nodes, bone marrow, brain, arterial and venous endothelial cells, and testes.5 The variety of tissues that contain ACE-2 receptors explains the many sites of infection and location of symptoms with which SARS-CoV-2 infection can manifest, in addition to the respiratory system.

Basic mRNA vaccine immunology

Although messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines seem novel, they have been in development for more than 30 years.8

mRNA encodes the protein for the antigen of interest and is delivered to the host muscle tissue. There, mRNA is translated into the antigen, which stimulates an immune response. Host enzymes then rapidly degrade the mRNA in the vaccine, and it is quickly eliminated from the host.

mRNA vaccines are attractive vaccine candidates, particularly in their application to emerging infectious diseases, for several reasons:

- They are nonreplicating.

- They do not integrate into the host genome.

- They are highly effective.

- They can produce antibody and cellular immunity.

- They can be produced (and modified) quickly on a large scale without having to grow the virus in eggs.

Continue to: Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2

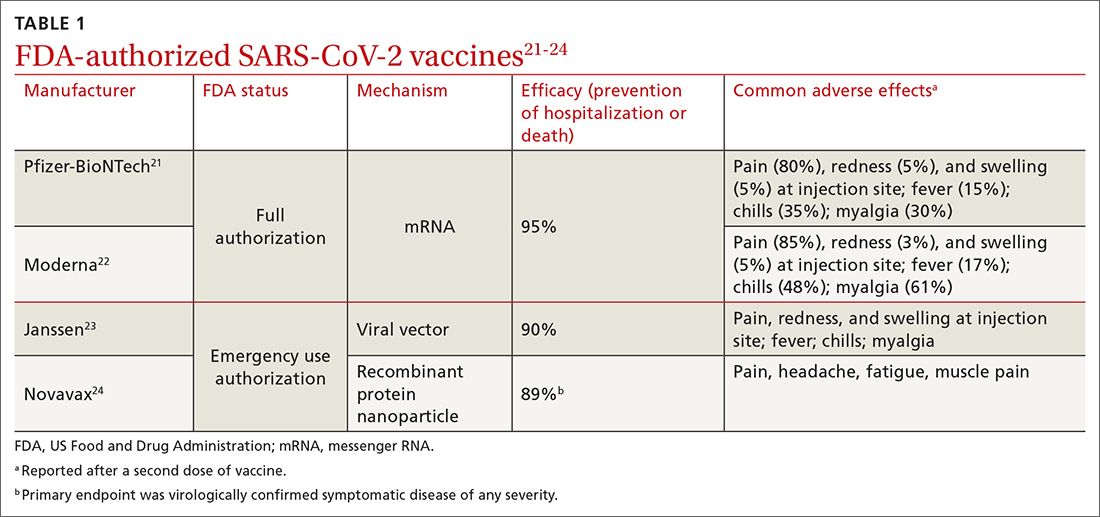

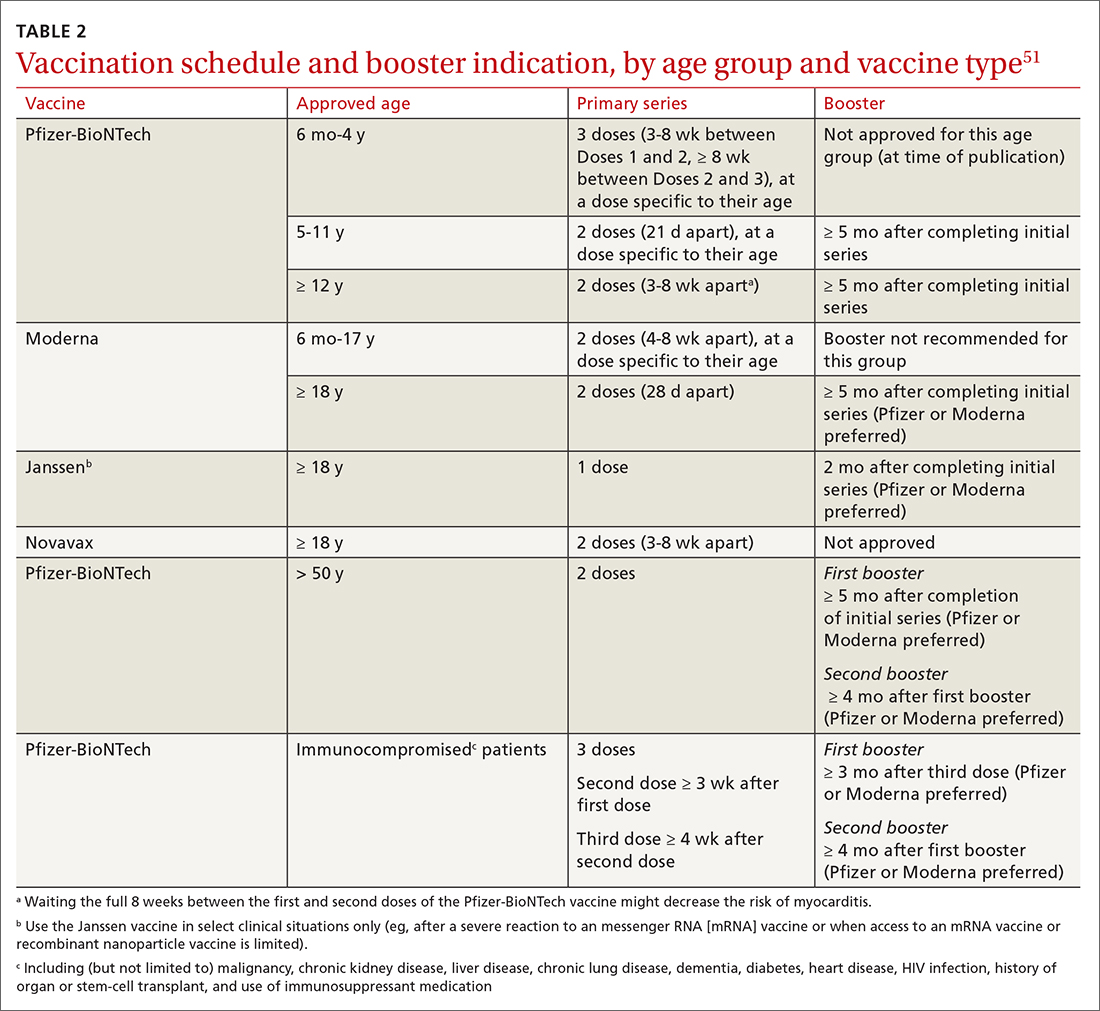

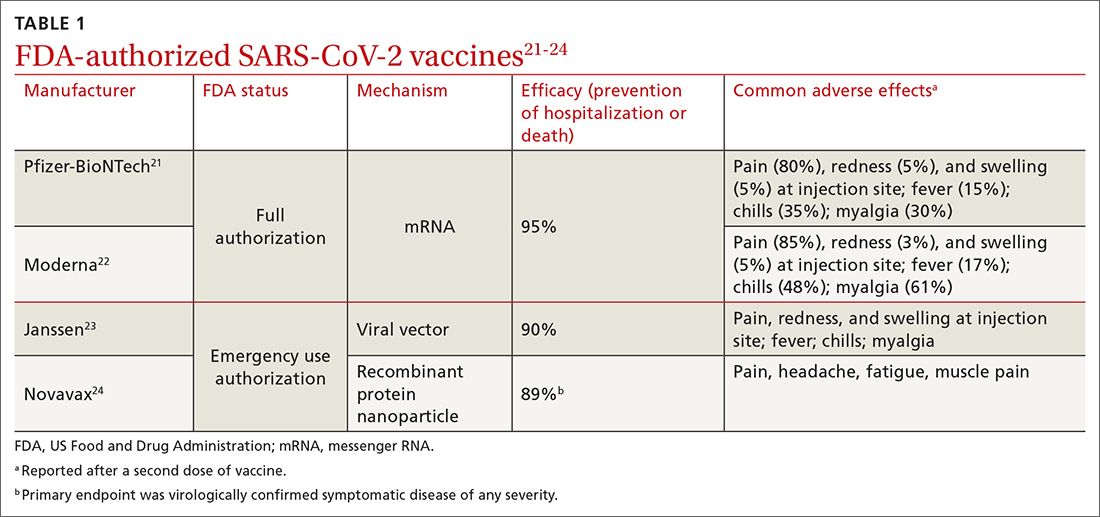

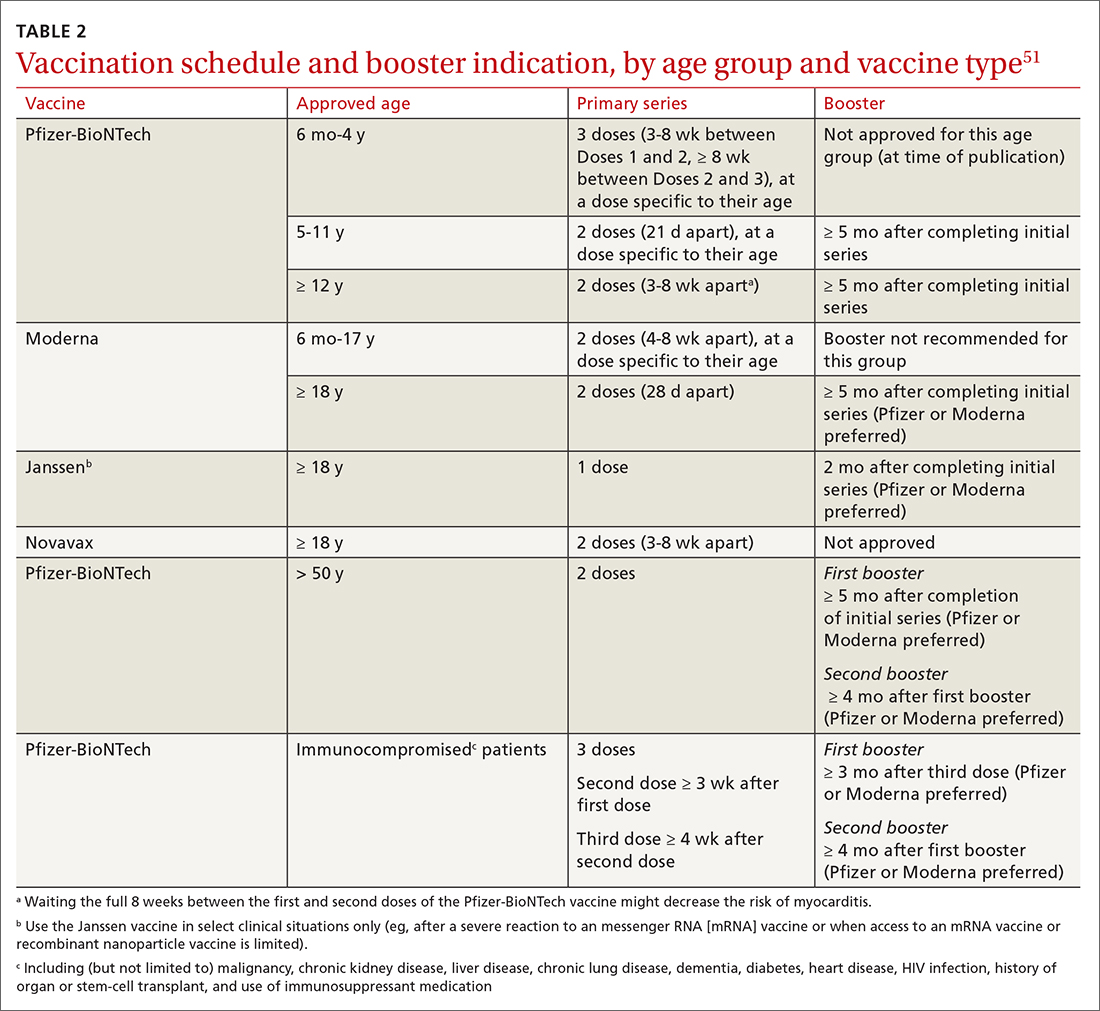

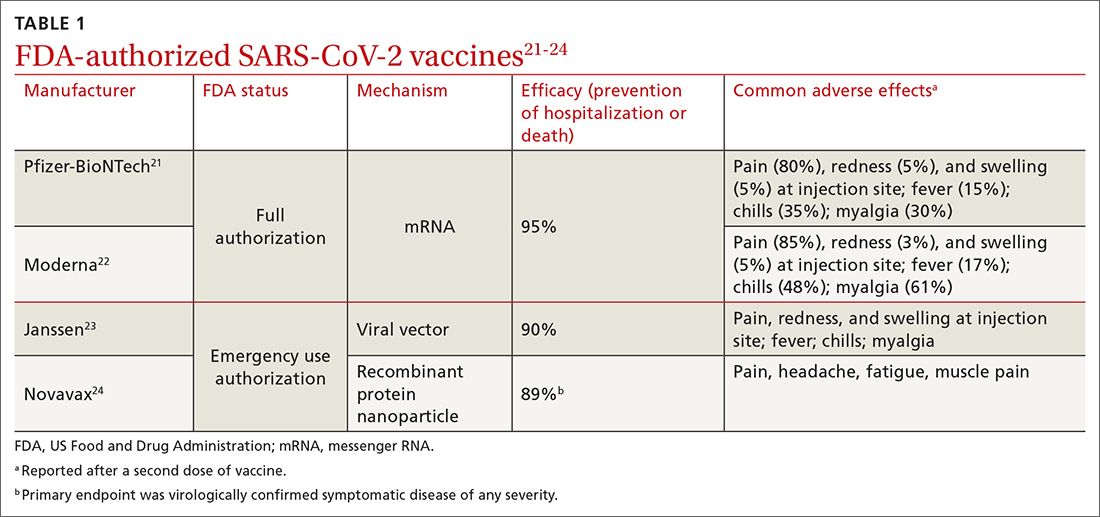

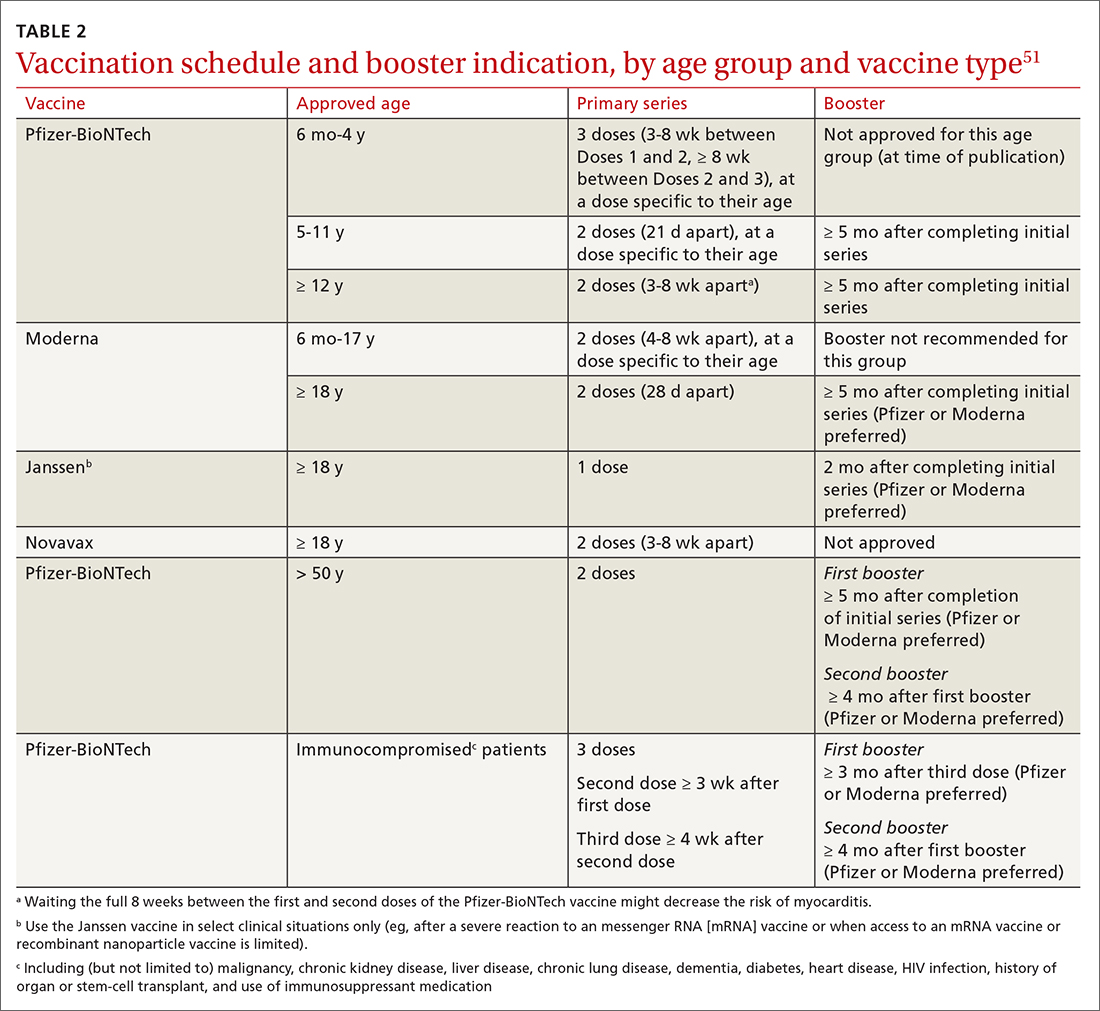

Two vaccines (from Pfizer-BioNTech [Comirnaty] and from Moderna [Spikevax]) are US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for COVID-19; both utilize mRNA technology. Two other vaccines, which do not use mRNA technology, have an FDA emergency use authorization (from Janssen Biotech, of Johnson & Johnson [Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine] and from Novavax [Novavax COVID-19 Vaccine, Adjuvanted]).9

Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. The mRNA of these vaccines encodes the entire spike protein in its pre-fusion conformation, which is the antigen that is replicated in the host, inducing an immune response.10-12 (Recall the earlier lock-and-key analogy: This conformation structure ingeniously replicates the exposed 3-dimensional key to the host’s immune system.)

The Janssen vaccine utilizes a viral vector (a nonreplicating adenovirus that functions as carrier) to deliver its message to the host for antigen production (again, the spike protein) and an immune response.

The Novavax vaccine uses a recombinant nanoparticle protein composed of the full-length spike protein.13,14 In this review, we focus on the 2 available mRNA vaccines, (1) given their FDA-authorized status and (2) because Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations indicate a preference for mRNA vaccination over viral-vectored vaccination. However, we also address key points about the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccine.

Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines

The first study to document the safety and efficacy of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine) was published just 12 months after the onset of the pandemic.10 This initial trial demonstrated a 95% efficacy in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 at 3-month follow-up.10 Clinical trial data on the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines have continued to be published since that first landmark trial.

Continue to: Data from trials...

Data from trials in Israel that became available early in 2021 showed that, in mRNA-vaccinated adults, mechanical ventilation rates declined strikingly, particularly in patients > 70 years of age.15,16 This finding was corroborated by data from a surveillance study of multiple US hospitals, which showed that mRNA vaccines were > 90% effective in preventing hospitalization in adults > 65 years of age.17

Data published in May 2021 showed that the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines were 94% effective in preventing COVID-19-related hospitalization.18 During the end of the Delta wave of the pandemic and the emergence of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, unvaccinated people were 5 times as likely to be infected as vaccinated people.19

In March 2022, data from 21 US medical centers in 18 states demonstrated that adults who had received 3 doses of the vaccine were 94% less likely to be intubated or die than those who were unvaccinated.16 A July 2022 retrospective cohort study of 231,037 subjects showed that the risk of hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction or for stroke after COVID-19 infection was reduced by more than half in fully vaccinated (ie, 2 doses of an mRNA vaccine or the viral vector [Janssen/Johnson & Johnson] vaccine) subjects, compared to unvaccinated subjects.20 The efficacy of the vaccines is summarized in TABLE 1.21-24

Even in patients who have natural infection, several studies have shown that COVID-19 vaccination after natural infection increases the level and durability of immune response to infection and reinfection and improves clinical outcomes.9,20,25,26 In summary, published literature shows that (1) mRNA vaccines are highly effective at preventing infection and (2) they augment immunity achieved by infection with circulating virus.

Breakthrough infection. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are associated with breakthrough infection (ie, infections in fully vaccinated people), a phenomenon influenced by the predominant viral variant circulating, the level of vaccine uptake in the studied population, and the timing of vaccination.27,28 Nevertheless, vaccinated people who experience breakthrough infection are much less likely to be hospitalized and die compared to those who are unvaccinated, and vaccination with an mRNA vaccine is more effective than immunity acquired from natural infection.29

Continue to: Vaccine adverse effects

Vaccine adverse effects: Common, rare, myths

Both early mRNA vaccine trials reported common minor adverse effects after vaccination (TABLE 121-24). These included redness and soreness at the injection site, fatigue, myalgias, fever, and nausea, and tended to be more common after the second dose. These adverse effects are similar to common adverse effects seen with other vaccines. Counseling information about adverse effects can be found on the CDC website.a

Two uncommon but serious adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination are myocarditis or pericarditis after mRNA vaccination and thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS), which occurs only with the Janssen vaccine.30,31

Myocarditis and pericarditis, particularly in young males (12 to 18 years), and mostly after a second dose of vaccine, was reported in May 2021. Since then, several studies have shown that the risk of myocarditis is slightly higher in males < 40 years of age, with a predicted case rate ranging from 1 to 10 excess cases for every 1 million patients vaccinated.30,32 This risk must be balanced against the rate of myocarditis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A large study in the United States demonstrated that the risk of myocarditis for those who contract COVID-19 is 16 times higher than it is for those who are disease free.33 Observational safety data from April 2022 showed that men ages 18 to 29 years had 7 to 8 times the risk of heart complications after natural infection, compared to men of those ages who had been vaccinated.34 In this study of 40 US health care systems, the incidence of myocarditis or pericarditis in that age group ranged from 55 to 100 cases for every 100,000 people after infection and from 6 to 15 cases for every 100,000 people after a second dose of an mRNA vaccine.34

A risk–benefit analysis conducted by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) ultimately supported the conclusions that (1) the risk of myocarditis secondary to vaccination is small and (2) clear benefits of preventing infection, hospitalization, death, and continued transmission outweigh that risk.35 Study of this question, utilizing vaccine safety and reporting systems around the world, has continued.

Continue to: There is emerging evidence...

There is emerging evidence that extending the interval between the 2 doses of vaccine decreases the risk of myocarditis, particularly in male adolescents.36 That evidence ultimately led the CDC to recommend that it might be optimal that an extended interval (ie, waiting 8 weeks between the first and second dose of vaccine), in particular for males ages 12 to 39 years, could be beneficial in decreasing the risk of myocarditis.