User login

Loan forgiveness and med school debt: What about me?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I run the division of medical ethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Many of you know that President Biden created a loan forgiveness program, forgiving up to $10,000 against federal student loans, including graduate and undergraduate education. The Department of Education is supposed to provide up to $20,000 in debt cancellation to Pell Grant recipients who have loans that are held by the Department of Education. Borrowers can get this relief if their income is less than $125,000 for an individual or $250,000 for married couples.

Many people have looked at this and said, “Hey, wait a minute. I paid off my loans. I didn’t get any reimbursement. That isn’t fair.”

who often still have huge amounts of debt, and either because of the income limits or because they don’t qualify because this debt was accrued long in the past, they’re saying, “What about me? Don’t you want to give any relief to me?”

This is a topic near and dear to my heart because I happen to be at a medical school, NYU, that has decided for the two medical schools it runs – our main campus, NYU in Manhattan and NYU Langone out on Long Island – that we’re going to go tuition free. We’ve done it for a couple of years.

We did it because I think all the administrators and faculty understood the tremendous burden that debt poses on people who both carry forward their undergraduate debt and then have medical school debt. This really leads to very difficult situations – which we have great empathy for – about what specialty you’re going to go into, whether you have to moonlight, and how you’re going to manage a huge burden of debt.

Many people don’t have sympathy out in the public. They say doctors make a large amount of money and they live a nice lifestyle, so we’re not going to relieve their debt. The reality is that, whoever you are, short of Bill Gates or Elon Musk, having hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt is no easy task to live with and to work off.

Still, when we created free tuition at NYU for our medical school, there were many people who paid high tuition fees in the past. Some of them said to us, “What about me?” We decided not to try to do anything retrospectively. The plan was to build up enough money so that we could handle no-cost tuition going forward. We didn’t really have it in our pocketbook to help people who’d already paid their debts or were saddled with NYU debt. Is it fair? No, it’s probably not fair, but it’s an improvement.

That’s what I want people to think about who are saying, “What about my medical school debt? What about my undergraduate plus medical school debt?” I think we should be grateful when efforts are being made to reduce very burdensome student loans that people have. It’s good to give that benefit and move it forward.

Does that mean no one should get anything unless everyone with any kind of debt from school is covered? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s fair either.

It is possible that we could continue to agitate politically and say, let’s go after some of the health care debt. Let’s go after some of the things that are still driving people to have to work more than they would or to choose specialties that they really don’t want to be in because they have to make up that debt.

It doesn’t mean the last word has been said about the politics of debt relief or, for that matter, the price of going to medical school in the first place and trying to see whether that can be driven down.

I don’t think it’s right to say, “If I can’t benefit, given the huge burden that I’m carrying, then I’m not going to try to give relief to others.” I think we’re relieving debt to the extent that we can do it. The nation can afford it. Going forward is a good thing. It’s wrong to create those gigantic debts in the first place.

What are we going to do about the past? We may decide that we need some sort of forgiveness or reparations for loans that were built up for others going backwards. I wouldn’t hold hostage the future and our children to what was probably a very poor, unethical practice about saddling doctors and others in the past with huge debt.

I’m Art Caplan at the division of medical ethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Thank you for watching.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I run the division of medical ethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Many of you know that President Biden created a loan forgiveness program, forgiving up to $10,000 against federal student loans, including graduate and undergraduate education. The Department of Education is supposed to provide up to $20,000 in debt cancellation to Pell Grant recipients who have loans that are held by the Department of Education. Borrowers can get this relief if their income is less than $125,000 for an individual or $250,000 for married couples.

Many people have looked at this and said, “Hey, wait a minute. I paid off my loans. I didn’t get any reimbursement. That isn’t fair.”

who often still have huge amounts of debt, and either because of the income limits or because they don’t qualify because this debt was accrued long in the past, they’re saying, “What about me? Don’t you want to give any relief to me?”

This is a topic near and dear to my heart because I happen to be at a medical school, NYU, that has decided for the two medical schools it runs – our main campus, NYU in Manhattan and NYU Langone out on Long Island – that we’re going to go tuition free. We’ve done it for a couple of years.

We did it because I think all the administrators and faculty understood the tremendous burden that debt poses on people who both carry forward their undergraduate debt and then have medical school debt. This really leads to very difficult situations – which we have great empathy for – about what specialty you’re going to go into, whether you have to moonlight, and how you’re going to manage a huge burden of debt.

Many people don’t have sympathy out in the public. They say doctors make a large amount of money and they live a nice lifestyle, so we’re not going to relieve their debt. The reality is that, whoever you are, short of Bill Gates or Elon Musk, having hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt is no easy task to live with and to work off.

Still, when we created free tuition at NYU for our medical school, there were many people who paid high tuition fees in the past. Some of them said to us, “What about me?” We decided not to try to do anything retrospectively. The plan was to build up enough money so that we could handle no-cost tuition going forward. We didn’t really have it in our pocketbook to help people who’d already paid their debts or were saddled with NYU debt. Is it fair? No, it’s probably not fair, but it’s an improvement.

That’s what I want people to think about who are saying, “What about my medical school debt? What about my undergraduate plus medical school debt?” I think we should be grateful when efforts are being made to reduce very burdensome student loans that people have. It’s good to give that benefit and move it forward.

Does that mean no one should get anything unless everyone with any kind of debt from school is covered? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s fair either.

It is possible that we could continue to agitate politically and say, let’s go after some of the health care debt. Let’s go after some of the things that are still driving people to have to work more than they would or to choose specialties that they really don’t want to be in because they have to make up that debt.

It doesn’t mean the last word has been said about the politics of debt relief or, for that matter, the price of going to medical school in the first place and trying to see whether that can be driven down.

I don’t think it’s right to say, “If I can’t benefit, given the huge burden that I’m carrying, then I’m not going to try to give relief to others.” I think we’re relieving debt to the extent that we can do it. The nation can afford it. Going forward is a good thing. It’s wrong to create those gigantic debts in the first place.

What are we going to do about the past? We may decide that we need some sort of forgiveness or reparations for loans that were built up for others going backwards. I wouldn’t hold hostage the future and our children to what was probably a very poor, unethical practice about saddling doctors and others in the past with huge debt.

I’m Art Caplan at the division of medical ethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Thank you for watching.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I run the division of medical ethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Many of you know that President Biden created a loan forgiveness program, forgiving up to $10,000 against federal student loans, including graduate and undergraduate education. The Department of Education is supposed to provide up to $20,000 in debt cancellation to Pell Grant recipients who have loans that are held by the Department of Education. Borrowers can get this relief if their income is less than $125,000 for an individual or $250,000 for married couples.

Many people have looked at this and said, “Hey, wait a minute. I paid off my loans. I didn’t get any reimbursement. That isn’t fair.”

who often still have huge amounts of debt, and either because of the income limits or because they don’t qualify because this debt was accrued long in the past, they’re saying, “What about me? Don’t you want to give any relief to me?”

This is a topic near and dear to my heart because I happen to be at a medical school, NYU, that has decided for the two medical schools it runs – our main campus, NYU in Manhattan and NYU Langone out on Long Island – that we’re going to go tuition free. We’ve done it for a couple of years.

We did it because I think all the administrators and faculty understood the tremendous burden that debt poses on people who both carry forward their undergraduate debt and then have medical school debt. This really leads to very difficult situations – which we have great empathy for – about what specialty you’re going to go into, whether you have to moonlight, and how you’re going to manage a huge burden of debt.

Many people don’t have sympathy out in the public. They say doctors make a large amount of money and they live a nice lifestyle, so we’re not going to relieve their debt. The reality is that, whoever you are, short of Bill Gates or Elon Musk, having hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt is no easy task to live with and to work off.

Still, when we created free tuition at NYU for our medical school, there were many people who paid high tuition fees in the past. Some of them said to us, “What about me?” We decided not to try to do anything retrospectively. The plan was to build up enough money so that we could handle no-cost tuition going forward. We didn’t really have it in our pocketbook to help people who’d already paid their debts or were saddled with NYU debt. Is it fair? No, it’s probably not fair, but it’s an improvement.

That’s what I want people to think about who are saying, “What about my medical school debt? What about my undergraduate plus medical school debt?” I think we should be grateful when efforts are being made to reduce very burdensome student loans that people have. It’s good to give that benefit and move it forward.

Does that mean no one should get anything unless everyone with any kind of debt from school is covered? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s fair either.

It is possible that we could continue to agitate politically and say, let’s go after some of the health care debt. Let’s go after some of the things that are still driving people to have to work more than they would or to choose specialties that they really don’t want to be in because they have to make up that debt.

It doesn’t mean the last word has been said about the politics of debt relief or, for that matter, the price of going to medical school in the first place and trying to see whether that can be driven down.

I don’t think it’s right to say, “If I can’t benefit, given the huge burden that I’m carrying, then I’m not going to try to give relief to others.” I think we’re relieving debt to the extent that we can do it. The nation can afford it. Going forward is a good thing. It’s wrong to create those gigantic debts in the first place.

What are we going to do about the past? We may decide that we need some sort of forgiveness or reparations for loans that were built up for others going backwards. I wouldn’t hold hostage the future and our children to what was probably a very poor, unethical practice about saddling doctors and others in the past with huge debt.

I’m Art Caplan at the division of medical ethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Thank you for watching.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The marked contrast in pandemic outcomes between Japan and the United States

This article was originally published Oct. 8 on Medscape Editor-In-Chief Eric Topol’s “Ground Truths” column on Substack.

Over time it has the least cumulative deaths per capita of any major country in the world. That’s without a zero-Covid policy or any national lockdowns, which is why I have not included China as a comparator.

Before we get into that data, let’s take a look at the age pyramids for Japan and the United States. The No. 1 risk factor for death from COVID-19 is advanced age, and you can see that in Japan about 25% of the population is age 65 and older, whereas in the United States that proportion is substantially reduced at 15%. Sure there are differences in comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes, but there is also the trade-off of a much higher population density in Japan.

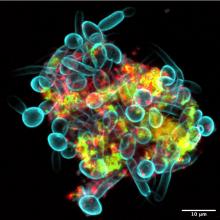

Besides masks, which were distributed early on by the government to the population in Japan, there was the “Avoid the 3Cs” cluster-busting strategy, widely disseminated in the spring of 2020, leveraging Pareto’s 80-20 principle, long before there were any vaccines available. For a good portion of the pandemic, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan maintained a strict policy for border control, which while hard to quantify, may certainly have contributed to its success.

Besides these factors, once vaccines became available, Japan got the population with the primary series to 83% rapidly, even after getting a late start by many months compared with the United States, which has peaked at 68%. That’s a big gap.

But that gap got much worse when it came to boosters. Ninety-five percent of Japanese eligible compared with 40.8% of Americans have had a booster shot. Of note, that 95% in Japan pertains to the whole population. In the United States the percentage of people age 65 and older who have had two boosters is currently only 42%. I’ve previously reviewed the important lifesaving impact of two boosters among people age 65 and older from five independent studies during Omicron waves throughout the world.

Now let’s turn to cumulative fatalities in the two countries. There’s a huge, nearly ninefold difference, per capita. Using today’s Covid-19 Dashboard, there are cumulatively 45,533 deaths in Japan and 1,062,560 American deaths. That translates to 1 in 2,758 people in Japan compared with 1 in 315 Americans dying of COVID.

And if we look at excess mortality instead of confirmed COVID deaths, that enormous gap doesn’t change.

Obviously it would be good to have data for other COVID outcomes, such as hospitalizations, ICUs, and Long COVID, but they are not accessible.

Comparing Japan, the country that has fared the best, with the United States, one of the worst pandemic outcome results, leaves us with a sense that Prof Ian MacKay’s “Swiss cheese model” is the best explanation. It’s not just one thing. Masks, consistent evidence-based communication (3Cs) with attention to ventilation and air quality, and the outstanding uptake of vaccines and boosters all contributed to Japan’s success.

There is another factor to add to that model – Paxlovid. Its benefit of reducing hospitalizations and deaths for people over age 65 is unquestionable.

That’s why I had previously modified the Swiss cheese model to add Paxlovid.

But in the United States, where 15% of the population is 65 and older, they account for over 75% of the daily death toll, still in the range of 400 per day. Here, with a very high proportion of people age 65 and older left vulnerable without boosters, or primary vaccines, Paxlovid is only being given to less than 25% of the eligible (age 50+), and less people age 80 and older are getting Paxlovid than those age 45. The reasons that doctors are not prescribing it – worried about interactions for a 5-day course and rebound – are not substantiated.

Bottom line: In the United States we are not protecting our population anywhere near as well as Japan, as grossly evident by the fatalities among people at the highest risk. There needs to be far better uptake of boosters and use of Paxlovid in the age 65+ group, but the need for amped up protection is not at all restricted to this age subgroup. Across all age groups age 18 and over there is an 81% reduction of hospitalizations with two boosters with the most updated CDC data available, through the Omicron BA.5 wave.

No less the previous data through May 2022 showing protection from death across all ages with two boosters

And please don’t forget that around the world, over 20 million lives were saved, just in 2021, the first year of vaccines.

We can learn so much from a model country like Japan. Yes, we need nasal and variant-proof vaccines to effectively deal with the new variants that are already getting legs in places like XBB in Singapore and ones not on the radar yet. But right now we’ve got to do far better for people getting boosters and, when a person age 65 or older gets COVID, Paxlovid. Take a look at the Chris Hayes video segment when he pleaded for Americans to get a booster shot. Every day that vaccine waning of the U.S. population exceeds the small percentage of people who get a booster, our vulnerability increases. If we don’t get that on track, it’s likely going to be a rough winter ahead.

Dr. Topol is director of the Scripps Translational Science Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health and reported conflicts of interest involving Dexcom, Illumina, Molecular Stethoscope, Quest Diagnostics, and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was originally published Oct. 8 on Medscape Editor-In-Chief Eric Topol’s “Ground Truths” column on Substack.

Over time it has the least cumulative deaths per capita of any major country in the world. That’s without a zero-Covid policy or any national lockdowns, which is why I have not included China as a comparator.

Before we get into that data, let’s take a look at the age pyramids for Japan and the United States. The No. 1 risk factor for death from COVID-19 is advanced age, and you can see that in Japan about 25% of the population is age 65 and older, whereas in the United States that proportion is substantially reduced at 15%. Sure there are differences in comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes, but there is also the trade-off of a much higher population density in Japan.

Besides masks, which were distributed early on by the government to the population in Japan, there was the “Avoid the 3Cs” cluster-busting strategy, widely disseminated in the spring of 2020, leveraging Pareto’s 80-20 principle, long before there were any vaccines available. For a good portion of the pandemic, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan maintained a strict policy for border control, which while hard to quantify, may certainly have contributed to its success.

Besides these factors, once vaccines became available, Japan got the population with the primary series to 83% rapidly, even after getting a late start by many months compared with the United States, which has peaked at 68%. That’s a big gap.

But that gap got much worse when it came to boosters. Ninety-five percent of Japanese eligible compared with 40.8% of Americans have had a booster shot. Of note, that 95% in Japan pertains to the whole population. In the United States the percentage of people age 65 and older who have had two boosters is currently only 42%. I’ve previously reviewed the important lifesaving impact of two boosters among people age 65 and older from five independent studies during Omicron waves throughout the world.

Now let’s turn to cumulative fatalities in the two countries. There’s a huge, nearly ninefold difference, per capita. Using today’s Covid-19 Dashboard, there are cumulatively 45,533 deaths in Japan and 1,062,560 American deaths. That translates to 1 in 2,758 people in Japan compared with 1 in 315 Americans dying of COVID.

And if we look at excess mortality instead of confirmed COVID deaths, that enormous gap doesn’t change.

Obviously it would be good to have data for other COVID outcomes, such as hospitalizations, ICUs, and Long COVID, but they are not accessible.

Comparing Japan, the country that has fared the best, with the United States, one of the worst pandemic outcome results, leaves us with a sense that Prof Ian MacKay’s “Swiss cheese model” is the best explanation. It’s not just one thing. Masks, consistent evidence-based communication (3Cs) with attention to ventilation and air quality, and the outstanding uptake of vaccines and boosters all contributed to Japan’s success.

There is another factor to add to that model – Paxlovid. Its benefit of reducing hospitalizations and deaths for people over age 65 is unquestionable.

That’s why I had previously modified the Swiss cheese model to add Paxlovid.

But in the United States, where 15% of the population is 65 and older, they account for over 75% of the daily death toll, still in the range of 400 per day. Here, with a very high proportion of people age 65 and older left vulnerable without boosters, or primary vaccines, Paxlovid is only being given to less than 25% of the eligible (age 50+), and less people age 80 and older are getting Paxlovid than those age 45. The reasons that doctors are not prescribing it – worried about interactions for a 5-day course and rebound – are not substantiated.

Bottom line: In the United States we are not protecting our population anywhere near as well as Japan, as grossly evident by the fatalities among people at the highest risk. There needs to be far better uptake of boosters and use of Paxlovid in the age 65+ group, but the need for amped up protection is not at all restricted to this age subgroup. Across all age groups age 18 and over there is an 81% reduction of hospitalizations with two boosters with the most updated CDC data available, through the Omicron BA.5 wave.

No less the previous data through May 2022 showing protection from death across all ages with two boosters

And please don’t forget that around the world, over 20 million lives were saved, just in 2021, the first year of vaccines.

We can learn so much from a model country like Japan. Yes, we need nasal and variant-proof vaccines to effectively deal with the new variants that are already getting legs in places like XBB in Singapore and ones not on the radar yet. But right now we’ve got to do far better for people getting boosters and, when a person age 65 or older gets COVID, Paxlovid. Take a look at the Chris Hayes video segment when he pleaded for Americans to get a booster shot. Every day that vaccine waning of the U.S. population exceeds the small percentage of people who get a booster, our vulnerability increases. If we don’t get that on track, it’s likely going to be a rough winter ahead.

Dr. Topol is director of the Scripps Translational Science Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health and reported conflicts of interest involving Dexcom, Illumina, Molecular Stethoscope, Quest Diagnostics, and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was originally published Oct. 8 on Medscape Editor-In-Chief Eric Topol’s “Ground Truths” column on Substack.

Over time it has the least cumulative deaths per capita of any major country in the world. That’s without a zero-Covid policy or any national lockdowns, which is why I have not included China as a comparator.

Before we get into that data, let’s take a look at the age pyramids for Japan and the United States. The No. 1 risk factor for death from COVID-19 is advanced age, and you can see that in Japan about 25% of the population is age 65 and older, whereas in the United States that proportion is substantially reduced at 15%. Sure there are differences in comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes, but there is also the trade-off of a much higher population density in Japan.

Besides masks, which were distributed early on by the government to the population in Japan, there was the “Avoid the 3Cs” cluster-busting strategy, widely disseminated in the spring of 2020, leveraging Pareto’s 80-20 principle, long before there were any vaccines available. For a good portion of the pandemic, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan maintained a strict policy for border control, which while hard to quantify, may certainly have contributed to its success.

Besides these factors, once vaccines became available, Japan got the population with the primary series to 83% rapidly, even after getting a late start by many months compared with the United States, which has peaked at 68%. That’s a big gap.

But that gap got much worse when it came to boosters. Ninety-five percent of Japanese eligible compared with 40.8% of Americans have had a booster shot. Of note, that 95% in Japan pertains to the whole population. In the United States the percentage of people age 65 and older who have had two boosters is currently only 42%. I’ve previously reviewed the important lifesaving impact of two boosters among people age 65 and older from five independent studies during Omicron waves throughout the world.

Now let’s turn to cumulative fatalities in the two countries. There’s a huge, nearly ninefold difference, per capita. Using today’s Covid-19 Dashboard, there are cumulatively 45,533 deaths in Japan and 1,062,560 American deaths. That translates to 1 in 2,758 people in Japan compared with 1 in 315 Americans dying of COVID.

And if we look at excess mortality instead of confirmed COVID deaths, that enormous gap doesn’t change.

Obviously it would be good to have data for other COVID outcomes, such as hospitalizations, ICUs, and Long COVID, but they are not accessible.

Comparing Japan, the country that has fared the best, with the United States, one of the worst pandemic outcome results, leaves us with a sense that Prof Ian MacKay’s “Swiss cheese model” is the best explanation. It’s not just one thing. Masks, consistent evidence-based communication (3Cs) with attention to ventilation and air quality, and the outstanding uptake of vaccines and boosters all contributed to Japan’s success.

There is another factor to add to that model – Paxlovid. Its benefit of reducing hospitalizations and deaths for people over age 65 is unquestionable.

That’s why I had previously modified the Swiss cheese model to add Paxlovid.

But in the United States, where 15% of the population is 65 and older, they account for over 75% of the daily death toll, still in the range of 400 per day. Here, with a very high proportion of people age 65 and older left vulnerable without boosters, or primary vaccines, Paxlovid is only being given to less than 25% of the eligible (age 50+), and less people age 80 and older are getting Paxlovid than those age 45. The reasons that doctors are not prescribing it – worried about interactions for a 5-day course and rebound – are not substantiated.

Bottom line: In the United States we are not protecting our population anywhere near as well as Japan, as grossly evident by the fatalities among people at the highest risk. There needs to be far better uptake of boosters and use of Paxlovid in the age 65+ group, but the need for amped up protection is not at all restricted to this age subgroup. Across all age groups age 18 and over there is an 81% reduction of hospitalizations with two boosters with the most updated CDC data available, through the Omicron BA.5 wave.

No less the previous data through May 2022 showing protection from death across all ages with two boosters

And please don’t forget that around the world, over 20 million lives were saved, just in 2021, the first year of vaccines.

We can learn so much from a model country like Japan. Yes, we need nasal and variant-proof vaccines to effectively deal with the new variants that are already getting legs in places like XBB in Singapore and ones not on the radar yet. But right now we’ve got to do far better for people getting boosters and, when a person age 65 or older gets COVID, Paxlovid. Take a look at the Chris Hayes video segment when he pleaded for Americans to get a booster shot. Every day that vaccine waning of the U.S. population exceeds the small percentage of people who get a booster, our vulnerability increases. If we don’t get that on track, it’s likely going to be a rough winter ahead.

Dr. Topol is director of the Scripps Translational Science Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health and reported conflicts of interest involving Dexcom, Illumina, Molecular Stethoscope, Quest Diagnostics, and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Tirzepatide’s benefits expand: Lean mass up, serum lipids down

STOCKHOLM – New insights into the benefits of treatment with the “twincretin” tirzepatide for people with overweight or obesity – with or without diabetes – come from new findings reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Additional results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which matched tirzepatide against placebo in people with overweight or obesity, provide further details on the favorable changes produced by 72 weeks of tirzepatide treatment on outcomes that included fat and lean mass, insulin sensitivity, and patient-reported outcomes related to functional health and well being, reported Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD.

And results from a meta-analysis of six trials that compared tirzepatide (Mounjaro) against several different comparators in patients with type 2 diabetes further confirm the drug’s ability to reliably produce positive changes in blood lipids, especially by significantly lowering levels of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and very LDL (VLDL) cholesterol, said Thomas Karagiannis, MD, PhD, in a separate report at the meeting.

Tirzepatide works as an agonist on receptors for both the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), and for the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and received Food and Drug Administration approval for treating people with type 2 diabetes in May 2022. On the basis of results from SURMOUNT-1, the FDA on Oct. 6 granted tirzepatide fast-track designation for a proposed labeling of the agent for treating people with overweight or obesity. This FDA decision will likely remain pending at least until results from a second trial in people with overweight or obesity but without diabetes, SURMOUNT-2, become available in 2023.

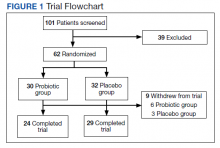

SURMOUNT-1 randomized 2,539 people with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related complication to a weekly injection of tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The study’s primary efficacy endpoints were the average reduction in weight from baseline, and the percentage of people in each treatment arm achieving weight loss of at least 5% from baseline.

For both endpoints, the outcomes with tirzepatide significantly surpassed placebo effects. Average weight loss ranged from 15%-21% from baseline, depending on dose, compared with 3% on placebo. The rate of participants with at least a 5% weight loss ranged from 85% to 91%, compared with 35% with placebo, as reported in July 2022 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cutting fat mass, boosting lean mass

New results from the trial reported by Dr. Jastreboff included a cut in fat mass from 46.2% of total body mass at baseline to 38.5% after 72 weeks, compared with a change from 46.8% at baseline to 44.7% after 72 weeks in the placebo group. Concurrently, lean mass increased with tirzepatide treatment from 51.0% at baseline to 58.1% after 72 weeks.

Participants who received tirzepatide, compared with those who received placebo, had “proportionately greater decrease in fat mass and proportionately greater increase in lean mass” compared with those who received placebo, said Dr. Jastreboff, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist with Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “I was impressed by the amount of visceral fat lost.”

These effects translated into a significant reduction in fat mass-to-lean mass ratio among the people treated with tirzepatide, with the greatest reduction in those who lost at least 15% of their starting weight. In that subgroup the fat-to-lean mass ratio dropped from 0.94 at baseline to 0.64 after 72 weeks of treatment, she said.

Focus on diet quality

People treated with tirzepatide “eat so little food that we need to improve the quality of what they eat to protect their muscle,” commented Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, a professor in the Diabetes Complications Research Centre of University College Dublin. “You no longer need a dietitian to help people lose weight, because the drug does that. You need dietitians to look after the nutritional health of patients while they lose weight,” Dr. le Roux said in a separate session at the meeting.

Additional tests showed that blood glucose and insulin levels were all significantly lower among trial participants on all three doses of tirzepatide compared with those on placebo, and the tirzepatide-treated subjects also had significant, roughly twofold elevations in their insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda Index.

The impact of tirzepatide on glucose and insulin levels and on insulin sensitivity was similar regardless of whether study participants had normoglycemia or prediabetes at entry. By design, no study participants had diabetes.

The trial assessed patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Participants had significant increases in all eight domains within the SF-36 at all three tirzepatide doses, compared with placebo, at 72 weeks, Dr. Jastreboff reported. Improvements in the physical function domain increased most notably among study participants on tirzepatide who had functional limitations at baseline. Heart rate rose among participants who received either of the two highest tirzepatide doses by 2.3-2.5 beats/min, comparable with the effect of other injected incretin-based treatments.

Lipids improve in those with type 2 diabetes

Tirzepatide treatment also results in a “secondary effect” of improving levels of several lipids in people with type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis of findings from six randomized trials. The meta-analysis collectively involved 4,502 participants treated for numerous weeks with one of three doses of tirzepatide and 2,144 people in comparator groups, reported Dr. Karagiannis, a diabetes researcher at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece).

Among the significant lipid changes linked with tirzepatide treatment, compared with placebo, were an average 13 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol, an average 6 mg/dL decrease in VLDL cholesterol, and an average 50 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides. In comparison to a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an average 25 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides and an average 4 mg/dL reduction in VLDL cholesterol were seen. And trials comparing tirzepatide with basal insulin saw average reductions of 7% in LDL cholesterol, 15% in VLDL cholesterol, 15% in triglycerides, and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.

Dr. Karagiannis highlighted that the clinical impact of these effects is unclear, although he noted that the average reduction in LDL cholesterol relative to placebo is of a magnitude that could have a modest effect on long-term outcomes.

These lipid effects of tirzepatide “should be considered alongside” tirzepatide’s “key metabolic effects” on weight and hemoglobin A1c as well as the drug’s safety, concluded Dr. Karagiannis.

The tirzepatide trials were all funded by Eli Lilly, which markets tirzepatide (Mounjaro). Dr. Jastreboff has been an adviser and consultant to Eli Lilly, as well as to Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Scholars, Roche, and Weight Watchers, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Karagiannis had no disclosures. Dr. le Roux has had financial relationships with Eli Lilly, as well as with Boehringer Ingelheim, Consilient Health, Covidion, Fractyl, GL Dynamics, Herbalife, Johnson & Johnson, Keyron, and Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – New insights into the benefits of treatment with the “twincretin” tirzepatide for people with overweight or obesity – with or without diabetes – come from new findings reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Additional results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which matched tirzepatide against placebo in people with overweight or obesity, provide further details on the favorable changes produced by 72 weeks of tirzepatide treatment on outcomes that included fat and lean mass, insulin sensitivity, and patient-reported outcomes related to functional health and well being, reported Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD.

And results from a meta-analysis of six trials that compared tirzepatide (Mounjaro) against several different comparators in patients with type 2 diabetes further confirm the drug’s ability to reliably produce positive changes in blood lipids, especially by significantly lowering levels of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and very LDL (VLDL) cholesterol, said Thomas Karagiannis, MD, PhD, in a separate report at the meeting.

Tirzepatide works as an agonist on receptors for both the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), and for the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and received Food and Drug Administration approval for treating people with type 2 diabetes in May 2022. On the basis of results from SURMOUNT-1, the FDA on Oct. 6 granted tirzepatide fast-track designation for a proposed labeling of the agent for treating people with overweight or obesity. This FDA decision will likely remain pending at least until results from a second trial in people with overweight or obesity but without diabetes, SURMOUNT-2, become available in 2023.

SURMOUNT-1 randomized 2,539 people with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related complication to a weekly injection of tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The study’s primary efficacy endpoints were the average reduction in weight from baseline, and the percentage of people in each treatment arm achieving weight loss of at least 5% from baseline.

For both endpoints, the outcomes with tirzepatide significantly surpassed placebo effects. Average weight loss ranged from 15%-21% from baseline, depending on dose, compared with 3% on placebo. The rate of participants with at least a 5% weight loss ranged from 85% to 91%, compared with 35% with placebo, as reported in July 2022 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cutting fat mass, boosting lean mass

New results from the trial reported by Dr. Jastreboff included a cut in fat mass from 46.2% of total body mass at baseline to 38.5% after 72 weeks, compared with a change from 46.8% at baseline to 44.7% after 72 weeks in the placebo group. Concurrently, lean mass increased with tirzepatide treatment from 51.0% at baseline to 58.1% after 72 weeks.

Participants who received tirzepatide, compared with those who received placebo, had “proportionately greater decrease in fat mass and proportionately greater increase in lean mass” compared with those who received placebo, said Dr. Jastreboff, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist with Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “I was impressed by the amount of visceral fat lost.”

These effects translated into a significant reduction in fat mass-to-lean mass ratio among the people treated with tirzepatide, with the greatest reduction in those who lost at least 15% of their starting weight. In that subgroup the fat-to-lean mass ratio dropped from 0.94 at baseline to 0.64 after 72 weeks of treatment, she said.

Focus on diet quality

People treated with tirzepatide “eat so little food that we need to improve the quality of what they eat to protect their muscle,” commented Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, a professor in the Diabetes Complications Research Centre of University College Dublin. “You no longer need a dietitian to help people lose weight, because the drug does that. You need dietitians to look after the nutritional health of patients while they lose weight,” Dr. le Roux said in a separate session at the meeting.

Additional tests showed that blood glucose and insulin levels were all significantly lower among trial participants on all three doses of tirzepatide compared with those on placebo, and the tirzepatide-treated subjects also had significant, roughly twofold elevations in their insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda Index.

The impact of tirzepatide on glucose and insulin levels and on insulin sensitivity was similar regardless of whether study participants had normoglycemia or prediabetes at entry. By design, no study participants had diabetes.

The trial assessed patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Participants had significant increases in all eight domains within the SF-36 at all three tirzepatide doses, compared with placebo, at 72 weeks, Dr. Jastreboff reported. Improvements in the physical function domain increased most notably among study participants on tirzepatide who had functional limitations at baseline. Heart rate rose among participants who received either of the two highest tirzepatide doses by 2.3-2.5 beats/min, comparable with the effect of other injected incretin-based treatments.

Lipids improve in those with type 2 diabetes

Tirzepatide treatment also results in a “secondary effect” of improving levels of several lipids in people with type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis of findings from six randomized trials. The meta-analysis collectively involved 4,502 participants treated for numerous weeks with one of three doses of tirzepatide and 2,144 people in comparator groups, reported Dr. Karagiannis, a diabetes researcher at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece).

Among the significant lipid changes linked with tirzepatide treatment, compared with placebo, were an average 13 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol, an average 6 mg/dL decrease in VLDL cholesterol, and an average 50 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides. In comparison to a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an average 25 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides and an average 4 mg/dL reduction in VLDL cholesterol were seen. And trials comparing tirzepatide with basal insulin saw average reductions of 7% in LDL cholesterol, 15% in VLDL cholesterol, 15% in triglycerides, and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.

Dr. Karagiannis highlighted that the clinical impact of these effects is unclear, although he noted that the average reduction in LDL cholesterol relative to placebo is of a magnitude that could have a modest effect on long-term outcomes.

These lipid effects of tirzepatide “should be considered alongside” tirzepatide’s “key metabolic effects” on weight and hemoglobin A1c as well as the drug’s safety, concluded Dr. Karagiannis.

The tirzepatide trials were all funded by Eli Lilly, which markets tirzepatide (Mounjaro). Dr. Jastreboff has been an adviser and consultant to Eli Lilly, as well as to Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Scholars, Roche, and Weight Watchers, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Karagiannis had no disclosures. Dr. le Roux has had financial relationships with Eli Lilly, as well as with Boehringer Ingelheim, Consilient Health, Covidion, Fractyl, GL Dynamics, Herbalife, Johnson & Johnson, Keyron, and Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – New insights into the benefits of treatment with the “twincretin” tirzepatide for people with overweight or obesity – with or without diabetes – come from new findings reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Additional results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which matched tirzepatide against placebo in people with overweight or obesity, provide further details on the favorable changes produced by 72 weeks of tirzepatide treatment on outcomes that included fat and lean mass, insulin sensitivity, and patient-reported outcomes related to functional health and well being, reported Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD.

And results from a meta-analysis of six trials that compared tirzepatide (Mounjaro) against several different comparators in patients with type 2 diabetes further confirm the drug’s ability to reliably produce positive changes in blood lipids, especially by significantly lowering levels of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and very LDL (VLDL) cholesterol, said Thomas Karagiannis, MD, PhD, in a separate report at the meeting.

Tirzepatide works as an agonist on receptors for both the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), and for the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and received Food and Drug Administration approval for treating people with type 2 diabetes in May 2022. On the basis of results from SURMOUNT-1, the FDA on Oct. 6 granted tirzepatide fast-track designation for a proposed labeling of the agent for treating people with overweight or obesity. This FDA decision will likely remain pending at least until results from a second trial in people with overweight or obesity but without diabetes, SURMOUNT-2, become available in 2023.

SURMOUNT-1 randomized 2,539 people with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related complication to a weekly injection of tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The study’s primary efficacy endpoints were the average reduction in weight from baseline, and the percentage of people in each treatment arm achieving weight loss of at least 5% from baseline.

For both endpoints, the outcomes with tirzepatide significantly surpassed placebo effects. Average weight loss ranged from 15%-21% from baseline, depending on dose, compared with 3% on placebo. The rate of participants with at least a 5% weight loss ranged from 85% to 91%, compared with 35% with placebo, as reported in July 2022 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cutting fat mass, boosting lean mass

New results from the trial reported by Dr. Jastreboff included a cut in fat mass from 46.2% of total body mass at baseline to 38.5% after 72 weeks, compared with a change from 46.8% at baseline to 44.7% after 72 weeks in the placebo group. Concurrently, lean mass increased with tirzepatide treatment from 51.0% at baseline to 58.1% after 72 weeks.

Participants who received tirzepatide, compared with those who received placebo, had “proportionately greater decrease in fat mass and proportionately greater increase in lean mass” compared with those who received placebo, said Dr. Jastreboff, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist with Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “I was impressed by the amount of visceral fat lost.”

These effects translated into a significant reduction in fat mass-to-lean mass ratio among the people treated with tirzepatide, with the greatest reduction in those who lost at least 15% of their starting weight. In that subgroup the fat-to-lean mass ratio dropped from 0.94 at baseline to 0.64 after 72 weeks of treatment, she said.

Focus on diet quality

People treated with tirzepatide “eat so little food that we need to improve the quality of what they eat to protect their muscle,” commented Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, a professor in the Diabetes Complications Research Centre of University College Dublin. “You no longer need a dietitian to help people lose weight, because the drug does that. You need dietitians to look after the nutritional health of patients while they lose weight,” Dr. le Roux said in a separate session at the meeting.

Additional tests showed that blood glucose and insulin levels were all significantly lower among trial participants on all three doses of tirzepatide compared with those on placebo, and the tirzepatide-treated subjects also had significant, roughly twofold elevations in their insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda Index.

The impact of tirzepatide on glucose and insulin levels and on insulin sensitivity was similar regardless of whether study participants had normoglycemia or prediabetes at entry. By design, no study participants had diabetes.

The trial assessed patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Participants had significant increases in all eight domains within the SF-36 at all three tirzepatide doses, compared with placebo, at 72 weeks, Dr. Jastreboff reported. Improvements in the physical function domain increased most notably among study participants on tirzepatide who had functional limitations at baseline. Heart rate rose among participants who received either of the two highest tirzepatide doses by 2.3-2.5 beats/min, comparable with the effect of other injected incretin-based treatments.

Lipids improve in those with type 2 diabetes

Tirzepatide treatment also results in a “secondary effect” of improving levels of several lipids in people with type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis of findings from six randomized trials. The meta-analysis collectively involved 4,502 participants treated for numerous weeks with one of three doses of tirzepatide and 2,144 people in comparator groups, reported Dr. Karagiannis, a diabetes researcher at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece).

Among the significant lipid changes linked with tirzepatide treatment, compared with placebo, were an average 13 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol, an average 6 mg/dL decrease in VLDL cholesterol, and an average 50 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides. In comparison to a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an average 25 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides and an average 4 mg/dL reduction in VLDL cholesterol were seen. And trials comparing tirzepatide with basal insulin saw average reductions of 7% in LDL cholesterol, 15% in VLDL cholesterol, 15% in triglycerides, and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.

Dr. Karagiannis highlighted that the clinical impact of these effects is unclear, although he noted that the average reduction in LDL cholesterol relative to placebo is of a magnitude that could have a modest effect on long-term outcomes.

These lipid effects of tirzepatide “should be considered alongside” tirzepatide’s “key metabolic effects” on weight and hemoglobin A1c as well as the drug’s safety, concluded Dr. Karagiannis.

The tirzepatide trials were all funded by Eli Lilly, which markets tirzepatide (Mounjaro). Dr. Jastreboff has been an adviser and consultant to Eli Lilly, as well as to Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Scholars, Roche, and Weight Watchers, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Karagiannis had no disclosures. Dr. le Roux has had financial relationships with Eli Lilly, as well as with Boehringer Ingelheim, Consilient Health, Covidion, Fractyl, GL Dynamics, Herbalife, Johnson & Johnson, Keyron, and Novo Nordisk.

AT EASD 2022

Playing the fat shame game in medicine: It needs to stop

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.

Upon finishing medical school, many of us recited this passage from a modernized version of the Hippocratic Oath. Though there has been controversy regarding the current relevancy of this oath, it can still serve as a reminder of the promises we made on behalf of our patients: To treat them ethically, with empathy and respect, and without pretension. Though I hadn’t thought about the Hippocratic Oath in ages, it came to mind recently after I read an article about weight trends in adults during the COVID pandemic.

No surprise – we gained weight during the initial surge at a rate of roughly a pound and a half per month following the initial shelter-in-place period. For some of us, that trend in weight gain worsened as the pandemic persisted. A survey conducted in February 2021 suggested that over 40% of adults who experienced undesired weight changes since the start of the pandemic gained an average of 29 pounds (significantly more than the typical gain of 15 pounds, often referred to as the “Quarantine 15” or “COVID-15”).

Updated data, obtained via a review of electronic health records for over 15 million patients, shows that 39% of patients gained weight during the pandemic (10% of them gained more than 12.5 pounds, while 2% gained over 27.5 pounds). Though these recent numbers may be lower than previously reported, they still aren’t reassuring.

Research has already confirmed that sizeism has a negative impact on both a patient’s physical health and psychological well-being, and as medical providers, we’re part of the problem. We cause distress in our patients through disrespectful treatment and medical fat shaming, which can lead to cycles of disordered eating, reduced physical activity, and more weight gain. We discriminate based on weight, causing our patients to delay health care visits and other provider interactions, resulting in increased risks for morbidity and even mortality. We make assumptions that a patient’s presenting complaints are due to weight rather than other causes, resulting in missed diagnoses. And we recommend different treatments for obese patients with the same condition as nonobese patients simply because of their weight.

One study has suggested that over 40% of adults in the United States have suffered from weight stigma, and physicians and coworkers are listed as some of the most common sources. Another study suggests that nearly 70% of overweight or obese patients report feeling stigmatized by physicians, whether through expressed biases or purposeful avoidance (patients have previously reported that their providers addressed weight loss in fewer than 20% of their examinations).

As health care providers, we need to do better. We should all be willing to consider our own biases about body size, and there are self-assessments to help with this, including the Implicit Associations Test: Weight Bias. By becoming more self-aware, hopefully we can change the doctor-patient conversation about weight management.

Studies have shown that meaningful conversations with physicians can have a significant impact on patients’ attempts to change behaviors related to weight. Yet, many medical providers are not trained in how to counsel patients on nutrition, weight loss, and physical activity (if we bring it up at all). We need to better educate ourselves about weight science and treatments.

In the meantime, we can work on how we interact with our patients:

- Make sure that your practice space is accommodating and nondiscriminatory, with appropriately sized furniture in the waiting and exam rooms, large blood pressure cuffs and gowns, and size-inclusive reading materials.

- Ensure that your workplace has an antiharassment policy that includes sizeism.

- Be an ally and speak up against weight discrimination.

- Educate your office staff about weight stigma and ensure that they avoid commenting on the weight or body size of others (being recognized only for losing weight isn’t a compliment, and sharing “fat jokes” isn’t funny).

- Remember that a person’s body size tells you nothing about that person’s health behaviors. Stop assuming that larger body sizes are related to laziness, overeating, or a lack of motivation.

- Ask your overweight or obese patients if they are willing to talk about their weight before jumping into the topic.

- Practice (patients are more likely to report changing their exercise routine and attempting to lose weight with these techniques).

- Be mindful of your word choices; for example, it can be more helpful to focus on comorbidities (such as high blood pressure or prediabetes) rather than body weight, nutrition rather than dieting, and physical activity rather than specific exercises.

Regardless of how you feel about reciting the Hippocratic Oath, our patients, no matter their body size, deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, as others have said in more eloquent ways than I. Let’s stop playing the fat shame game and help fight weight bias in medicine.

Dr. Devlin is president, Locum Infectious Disease Services, and an independent contractor for Weatherby Healthcare. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.

Upon finishing medical school, many of us recited this passage from a modernized version of the Hippocratic Oath. Though there has been controversy regarding the current relevancy of this oath, it can still serve as a reminder of the promises we made on behalf of our patients: To treat them ethically, with empathy and respect, and without pretension. Though I hadn’t thought about the Hippocratic Oath in ages, it came to mind recently after I read an article about weight trends in adults during the COVID pandemic.

No surprise – we gained weight during the initial surge at a rate of roughly a pound and a half per month following the initial shelter-in-place period. For some of us, that trend in weight gain worsened as the pandemic persisted. A survey conducted in February 2021 suggested that over 40% of adults who experienced undesired weight changes since the start of the pandemic gained an average of 29 pounds (significantly more than the typical gain of 15 pounds, often referred to as the “Quarantine 15” or “COVID-15”).

Updated data, obtained via a review of electronic health records for over 15 million patients, shows that 39% of patients gained weight during the pandemic (10% of them gained more than 12.5 pounds, while 2% gained over 27.5 pounds). Though these recent numbers may be lower than previously reported, they still aren’t reassuring.

Research has already confirmed that sizeism has a negative impact on both a patient’s physical health and psychological well-being, and as medical providers, we’re part of the problem. We cause distress in our patients through disrespectful treatment and medical fat shaming, which can lead to cycles of disordered eating, reduced physical activity, and more weight gain. We discriminate based on weight, causing our patients to delay health care visits and other provider interactions, resulting in increased risks for morbidity and even mortality. We make assumptions that a patient’s presenting complaints are due to weight rather than other causes, resulting in missed diagnoses. And we recommend different treatments for obese patients with the same condition as nonobese patients simply because of their weight.

One study has suggested that over 40% of adults in the United States have suffered from weight stigma, and physicians and coworkers are listed as some of the most common sources. Another study suggests that nearly 70% of overweight or obese patients report feeling stigmatized by physicians, whether through expressed biases or purposeful avoidance (patients have previously reported that their providers addressed weight loss in fewer than 20% of their examinations).

As health care providers, we need to do better. We should all be willing to consider our own biases about body size, and there are self-assessments to help with this, including the Implicit Associations Test: Weight Bias. By becoming more self-aware, hopefully we can change the doctor-patient conversation about weight management.

Studies have shown that meaningful conversations with physicians can have a significant impact on patients’ attempts to change behaviors related to weight. Yet, many medical providers are not trained in how to counsel patients on nutrition, weight loss, and physical activity (if we bring it up at all). We need to better educate ourselves about weight science and treatments.

In the meantime, we can work on how we interact with our patients:

- Make sure that your practice space is accommodating and nondiscriminatory, with appropriately sized furniture in the waiting and exam rooms, large blood pressure cuffs and gowns, and size-inclusive reading materials.

- Ensure that your workplace has an antiharassment policy that includes sizeism.

- Be an ally and speak up against weight discrimination.

- Educate your office staff about weight stigma and ensure that they avoid commenting on the weight or body size of others (being recognized only for losing weight isn’t a compliment, and sharing “fat jokes” isn’t funny).

- Remember that a person’s body size tells you nothing about that person’s health behaviors. Stop assuming that larger body sizes are related to laziness, overeating, or a lack of motivation.

- Ask your overweight or obese patients if they are willing to talk about their weight before jumping into the topic.

- Practice (patients are more likely to report changing their exercise routine and attempting to lose weight with these techniques).

- Be mindful of your word choices; for example, it can be more helpful to focus on comorbidities (such as high blood pressure or prediabetes) rather than body weight, nutrition rather than dieting, and physical activity rather than specific exercises.

Regardless of how you feel about reciting the Hippocratic Oath, our patients, no matter their body size, deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, as others have said in more eloquent ways than I. Let’s stop playing the fat shame game and help fight weight bias in medicine.

Dr. Devlin is president, Locum Infectious Disease Services, and an independent contractor for Weatherby Healthcare. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.

Upon finishing medical school, many of us recited this passage from a modernized version of the Hippocratic Oath. Though there has been controversy regarding the current relevancy of this oath, it can still serve as a reminder of the promises we made on behalf of our patients: To treat them ethically, with empathy and respect, and without pretension. Though I hadn’t thought about the Hippocratic Oath in ages, it came to mind recently after I read an article about weight trends in adults during the COVID pandemic.

No surprise – we gained weight during the initial surge at a rate of roughly a pound and a half per month following the initial shelter-in-place period. For some of us, that trend in weight gain worsened as the pandemic persisted. A survey conducted in February 2021 suggested that over 40% of adults who experienced undesired weight changes since the start of the pandemic gained an average of 29 pounds (significantly more than the typical gain of 15 pounds, often referred to as the “Quarantine 15” or “COVID-15”).

Updated data, obtained via a review of electronic health records for over 15 million patients, shows that 39% of patients gained weight during the pandemic (10% of them gained more than 12.5 pounds, while 2% gained over 27.5 pounds). Though these recent numbers may be lower than previously reported, they still aren’t reassuring.

Research has already confirmed that sizeism has a negative impact on both a patient’s physical health and psychological well-being, and as medical providers, we’re part of the problem. We cause distress in our patients through disrespectful treatment and medical fat shaming, which can lead to cycles of disordered eating, reduced physical activity, and more weight gain. We discriminate based on weight, causing our patients to delay health care visits and other provider interactions, resulting in increased risks for morbidity and even mortality. We make assumptions that a patient’s presenting complaints are due to weight rather than other causes, resulting in missed diagnoses. And we recommend different treatments for obese patients with the same condition as nonobese patients simply because of their weight.

One study has suggested that over 40% of adults in the United States have suffered from weight stigma, and physicians and coworkers are listed as some of the most common sources. Another study suggests that nearly 70% of overweight or obese patients report feeling stigmatized by physicians, whether through expressed biases or purposeful avoidance (patients have previously reported that their providers addressed weight loss in fewer than 20% of their examinations).

As health care providers, we need to do better. We should all be willing to consider our own biases about body size, and there are self-assessments to help with this, including the Implicit Associations Test: Weight Bias. By becoming more self-aware, hopefully we can change the doctor-patient conversation about weight management.

Studies have shown that meaningful conversations with physicians can have a significant impact on patients’ attempts to change behaviors related to weight. Yet, many medical providers are not trained in how to counsel patients on nutrition, weight loss, and physical activity (if we bring it up at all). We need to better educate ourselves about weight science and treatments.

In the meantime, we can work on how we interact with our patients:

- Make sure that your practice space is accommodating and nondiscriminatory, with appropriately sized furniture in the waiting and exam rooms, large blood pressure cuffs and gowns, and size-inclusive reading materials.

- Ensure that your workplace has an antiharassment policy that includes sizeism.

- Be an ally and speak up against weight discrimination.

- Educate your office staff about weight stigma and ensure that they avoid commenting on the weight or body size of others (being recognized only for losing weight isn’t a compliment, and sharing “fat jokes” isn’t funny).

- Remember that a person’s body size tells you nothing about that person’s health behaviors. Stop assuming that larger body sizes are related to laziness, overeating, or a lack of motivation.

- Ask your overweight or obese patients if they are willing to talk about their weight before jumping into the topic.

- Practice (patients are more likely to report changing their exercise routine and attempting to lose weight with these techniques).

- Be mindful of your word choices; for example, it can be more helpful to focus on comorbidities (such as high blood pressure or prediabetes) rather than body weight, nutrition rather than dieting, and physical activity rather than specific exercises.

Regardless of how you feel about reciting the Hippocratic Oath, our patients, no matter their body size, deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, as others have said in more eloquent ways than I. Let’s stop playing the fat shame game and help fight weight bias in medicine.

Dr. Devlin is president, Locum Infectious Disease Services, and an independent contractor for Weatherby Healthcare. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Headache for inpatients with COVID-19 may predict better survival

, according to recent research published in the journal Headache.

In the systematic review and meta-analysis, Víctor J. Gallardo, MSc, of the headache and neurologic pain research group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and colleagues performed a search of studies in PubMed involving headache symptoms, disease survival, and inpatient COVID-19 cases published between December 2019 and December 2020. Overall, 48 studies were identified, consisting of 43,169 inpatients with COVID-19. Using random-effects pooling models, Mr. Gallardo and colleagues estimated the prevalence of headache for inpatients who survived COVID-19, compared with those who did not survive.

Within those studies, 35,132 inpatients (81.4%) survived, while 8,037 inpatients (18.6%) died from COVID-19. The researchers found that inpatients with COVID-19 and headache symptoms had a significantly higher survival rate compared with inpatients with COVID-19 without headache symptoms (risk ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.47; P < .0001). There was an overall pooled prevalence of headache as a COVID-19 symptom in 10.4% of inpatients, which was reduced to an estimated pooled prevalence of 9.7% after the researchers removed outlier studies in a sensitivity analysis.

Other COVID-19 symptoms that led to improved rates of survival among inpatients were anosmia (RR, 2.94; 95% CI, 1.94-4.45) and myalgia (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34-1.83) as well as nausea or vomiting (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.08-1.82), while symptoms such as dyspnea, diabetes, chronic liver diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and chronic kidney diseases were more likely to increase the risk of dying from COVID-19.

The researchers noted several limitations in their meta-analysis that may make their findings less generalizable to future SARS-CoV-2 variants, such as including only studies that were published before COVID-19 vaccines were available and before more infectious SARS-CoV-2 variants like the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant emerged. They also included studies where inpatients were not tested for COVID-19 because access to testing was not widely available.

“Our meta-analysis points toward a novel possibility: Headache arising secondary to an infection is not a ‘nonspecific’ symptom, but rather it may be a marker of enhanced likelihood of survival. That is, we find that patients reporting headache in the setting of COVID-19 are at reduced risk of death,” Mr. Gallardo and colleagues wrote.

More data needed on association between headache and COVID-19

While headache appeared to affect a small proportion of overall inpatients with COVID-19, the researchers noted this might be because individuals with COVID-19 and headache symptoms are less likely to require hospitalization or a visit to the ED. Another potential explanation is that “people with primary headache disorders, including migraine, may be more likely to report symptoms of COVID-19, but they also may be relatively less likely to experience a life-threatening COVID-19 disease course.”

The researchers said this potential association should be explored in future studies as well as in other viral infections or postviral syndromes such as long COVID. “Defining specific headache mechanisms that could enhance survival from viral infections represents an opportunity for the potential discovery of improved viral therapeutics, as well as for understanding whether, and how, primary headache disorders may be adaptive.”

In a comment, Morris Levin, MD, director of the University of California San Francisco Headache Center, said the findings “of this very thought-provoking review suggest that reporting a headache during a COVID-19 infection seems to be associated with better recovery in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Levin, who was not involved with the study, acknowledged the researchers’ explanation for the overall low rate of headache in these inpatients as one possible explanation.

“Another could be that sick COVID patients were much more troubled by other symptoms like respiratory distress, which overshadowed their headache symptoms, particularly if they were very ill or if the headache pain was of only mild to moderate severity,” he said. “That could also be an alternate explanation for why less dangerously ill hospitalized patients seemed to have more headaches.”

One limitation he saw in the meta-analysis was how clearly the clinicians characterized headache symptoms in each reviewed study. Dr. Levin suggested a retrospective assessment of premorbid migraine history in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, including survivors and fatalities, might have helped clarify this issue. “The headaches themselves were not characterized so drawing conclusions regarding migraine is challenging.”

Dr. Levin noted it is still not well understood how acute and persistent headaches and other neurological symptoms like mental fog occur in patients with COVID-19. We also do not fully understand the natural history of post-COVID headaches and other neurologic sequelae and the management options for acute and persistent neurological sequelae.

Three authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of grants, consultancies, speaker’s bureau positions, guidelines committee member appointments, and editorial board positions for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, societies, and other organizations. Mr. Gallardo reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Levin reported no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to recent research published in the journal Headache.

In the systematic review and meta-analysis, Víctor J. Gallardo, MSc, of the headache and neurologic pain research group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and colleagues performed a search of studies in PubMed involving headache symptoms, disease survival, and inpatient COVID-19 cases published between December 2019 and December 2020. Overall, 48 studies were identified, consisting of 43,169 inpatients with COVID-19. Using random-effects pooling models, Mr. Gallardo and colleagues estimated the prevalence of headache for inpatients who survived COVID-19, compared with those who did not survive.

Within those studies, 35,132 inpatients (81.4%) survived, while 8,037 inpatients (18.6%) died from COVID-19. The researchers found that inpatients with COVID-19 and headache symptoms had a significantly higher survival rate compared with inpatients with COVID-19 without headache symptoms (risk ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.47; P < .0001). There was an overall pooled prevalence of headache as a COVID-19 symptom in 10.4% of inpatients, which was reduced to an estimated pooled prevalence of 9.7% after the researchers removed outlier studies in a sensitivity analysis.

Other COVID-19 symptoms that led to improved rates of survival among inpatients were anosmia (RR, 2.94; 95% CI, 1.94-4.45) and myalgia (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34-1.83) as well as nausea or vomiting (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.08-1.82), while symptoms such as dyspnea, diabetes, chronic liver diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and chronic kidney diseases were more likely to increase the risk of dying from COVID-19.

The researchers noted several limitations in their meta-analysis that may make their findings less generalizable to future SARS-CoV-2 variants, such as including only studies that were published before COVID-19 vaccines were available and before more infectious SARS-CoV-2 variants like the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant emerged. They also included studies where inpatients were not tested for COVID-19 because access to testing was not widely available.

“Our meta-analysis points toward a novel possibility: Headache arising secondary to an infection is not a ‘nonspecific’ symptom, but rather it may be a marker of enhanced likelihood of survival. That is, we find that patients reporting headache in the setting of COVID-19 are at reduced risk of death,” Mr. Gallardo and colleagues wrote.

More data needed on association between headache and COVID-19

While headache appeared to affect a small proportion of overall inpatients with COVID-19, the researchers noted this might be because individuals with COVID-19 and headache symptoms are less likely to require hospitalization or a visit to the ED. Another potential explanation is that “people with primary headache disorders, including migraine, may be more likely to report symptoms of COVID-19, but they also may be relatively less likely to experience a life-threatening COVID-19 disease course.”

The researchers said this potential association should be explored in future studies as well as in other viral infections or postviral syndromes such as long COVID. “Defining specific headache mechanisms that could enhance survival from viral infections represents an opportunity for the potential discovery of improved viral therapeutics, as well as for understanding whether, and how, primary headache disorders may be adaptive.”

In a comment, Morris Levin, MD, director of the University of California San Francisco Headache Center, said the findings “of this very thought-provoking review suggest that reporting a headache during a COVID-19 infection seems to be associated with better recovery in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Levin, who was not involved with the study, acknowledged the researchers’ explanation for the overall low rate of headache in these inpatients as one possible explanation.

“Another could be that sick COVID patients were much more troubled by other symptoms like respiratory distress, which overshadowed their headache symptoms, particularly if they were very ill or if the headache pain was of only mild to moderate severity,” he said. “That could also be an alternate explanation for why less dangerously ill hospitalized patients seemed to have more headaches.”