User login

Diagnostic criterion may hide borderline personality disorder

Investigators compared characteristics of almost 400 psychiatric outpatients diagnosed with BPD. About half of the participants met the suicidality/self-injury diagnostic criterion for the disorder, while the other half did not.

Results showed no differences between the two groups in degree of impairment in occupational or social functioning, comorbid psychiatric disorders, history of childhood trauma, or severity of depression, anxiety, or anger.

“Just because a person doesn’t engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior doesn’t mean that the person is free of borderline personality disorder,” lead author Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“Clinicians need to screen for borderline personality disorder in patients with other suggestive symptoms, even if those patients don’t self-harm, just as they would for similar patients who do self-harm,” said Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the Outpatient Division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

The findings were published online in Psychological Medicine.

A ‘polythetic diagnosis’

Dr. Zimmerman noted the impetus for conducting the study originated with a patient he saw who had all of the features of BPD except for self-harm and suicidality. However, because she didn’t have those two features, she was told by her therapist she could not have BPD.

“This sparked the idea that perhaps there are other individuals whose BPD may not be recognized because they don’t engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

“Most individuals with BPD don’t present for treatment saying, ‘I’m here because I don’t have a sense of myself’ or ‘I feel empty inside’ – but they do say, ‘I’m here because I’m cutting myself’ or ‘I’m suicidal,’ ” he added.

The investigators wondered if there were other “hidden” cases of BPD that were being missed by therapists.

They had previously analyzed each diagnostic criterion for BPD to ascertain its sensitivity. “We had been interested in wanting to see whether there was a criterion so frequent in BPD that every patient with BPD has it,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

BPD is a “polythetic diagnosis,” he added. It is “based on a list of features, with a certain minimum number of those features necessary to make the diagnosis rather than one specific criterion.”

His group’s previous research showed affective instability criterion to be present in more than 90% of individuals with BPD. “It had a very high negative predictive value, meaning that if you didn’t have affective instability, you didn’t have the disorder,” he said.

“Given the clinical and public health significance of suicidal and self-harm behavior in patients with BPD, an important question is whether the absence of this criterion, which might attenuate the likelihood of recognizing and diagnosing the disorder, identifies a subgroup of patients with BPD who are ‘less borderline’ than patients with BPD who do not manifest this criterion,” the investigators write.

The researchers wanted to see if a similar finding applied to self-injury and suicidal behavior and turned to the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with BPD who do and do not engage in repeated suicidal and self-harm behavior.

MIDAS project

The study population was derived from 3,800 psychiatric outpatients who had been evaluated in the MIDAS project with semi-structured diagnostic interviews.

Of these, 390 patients were diagnosed with BPD. Since the suicidality/self-harm item was not rated in one patient, the analyzed sample consisted of 389 individuals with BPD (28.3% male; mean age, 32.6 years; 86.3% White). A little more than half the participants (54%) met the BPD suicidality/ self-harm criterion.

Only one-fifth (20.5%) of patients with BPD presented with a chief complaint that was related to a feature of BPD and had received BPD as their principal diagnosis.

Patients who met the suicidality/self-injury criterion were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with BPD as the principal diagnosis, compared with those who did not have that criterion (24.8% vs. 14.5%, respectively; P < .01).

On the other hand, there was no difference in the mean number of BPD criteria that were met, other than suicidality/self-harm, between those who did and did not present with suicidality/self-harm (5.5 ± 1.2 vs. 5.7 ± 0.8, t = 1.44). The investigators note that this finding was “not significant.”

There also was no difference between patients who did and did not meet the criterion in number of psychiatric diagnoses at time of evaluation (3.4 ± 1.9 vs. 3.5 ± 1.8, t = 0.56).

Hidden BPD

Similarly, there was no difference in any specific Axis I or personality disorder – except for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and histrionic personality disorder. Both were more frequent in the patients who did not meet the suicidality/self-injury criterion. However, after controlling for age, the group difference in GAD was no longer deemed significant (F = 3.45, P = .064).

By contrast, histrionic personality disorder remained significant with age as the covariate (F = 6.03, P = .015).

“The patients who met the suicidality/self-injury criterion were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized and reported more suicidal ideation at the time of the evaluation,” the researchers write. Both variables remained significant even after including age as a covariate.

There were no between-group differences on severity of depression, anxiety, or anger at initial evaluation nor were there differences in social functioning, adolescent social functioning, likelihood of persistent unemployment or receiving disability payments, childhood trauma, or neglect.

“I suspect that there are a number of individuals whose BPD is not recognized because they don’t have the more overt feature of self-injury or suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Zimmerman, noting that these patients might be considered as having “hidden” BPD.

“Repeated self-injurious and suicidal behavior is not synonymous with BPD, and clinicians should be aware that the absence of these behaviors does not rule out a diagnosis of BPD,” he added.

Stigmatizing diagnosis?

Monica Carsky, PhD, clinical assistant professor of psychology in psychiatry and senior fellow, Personality Disorders Institute, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said the study “will be particularly useful in the education of clinicians about the characteristics of individuals with BPD.”

Dr. Carsky, who is also an adjunct assistant professor in the NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy, was not involved with the study. She noted that other factors “can contribute to misdiagnosis of the borderline patients who do not have suicidality/self-harm.”

Clinicians and patients “may see BPD as a stigmatizing diagnosis so that clinicians become reluctant to make, share, and explain this personality disorder diagnosis,” she said.

Dr. Carsky suggested that increasing use of the Alternate Model for Personality Disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), which first rates the severity level of personality by assessing identity and relationship problems and then notes traits of specific personality disorders, “will help clinicians who dread telling patients they are ‘borderline.’ ”

No source of study funding has been reported. The investigators and Dr. Carsky reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators compared characteristics of almost 400 psychiatric outpatients diagnosed with BPD. About half of the participants met the suicidality/self-injury diagnostic criterion for the disorder, while the other half did not.

Results showed no differences between the two groups in degree of impairment in occupational or social functioning, comorbid psychiatric disorders, history of childhood trauma, or severity of depression, anxiety, or anger.

“Just because a person doesn’t engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior doesn’t mean that the person is free of borderline personality disorder,” lead author Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“Clinicians need to screen for borderline personality disorder in patients with other suggestive symptoms, even if those patients don’t self-harm, just as they would for similar patients who do self-harm,” said Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the Outpatient Division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

The findings were published online in Psychological Medicine.

A ‘polythetic diagnosis’

Dr. Zimmerman noted the impetus for conducting the study originated with a patient he saw who had all of the features of BPD except for self-harm and suicidality. However, because she didn’t have those two features, she was told by her therapist she could not have BPD.

“This sparked the idea that perhaps there are other individuals whose BPD may not be recognized because they don’t engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

“Most individuals with BPD don’t present for treatment saying, ‘I’m here because I don’t have a sense of myself’ or ‘I feel empty inside’ – but they do say, ‘I’m here because I’m cutting myself’ or ‘I’m suicidal,’ ” he added.

The investigators wondered if there were other “hidden” cases of BPD that were being missed by therapists.

They had previously analyzed each diagnostic criterion for BPD to ascertain its sensitivity. “We had been interested in wanting to see whether there was a criterion so frequent in BPD that every patient with BPD has it,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

BPD is a “polythetic diagnosis,” he added. It is “based on a list of features, with a certain minimum number of those features necessary to make the diagnosis rather than one specific criterion.”

His group’s previous research showed affective instability criterion to be present in more than 90% of individuals with BPD. “It had a very high negative predictive value, meaning that if you didn’t have affective instability, you didn’t have the disorder,” he said.

“Given the clinical and public health significance of suicidal and self-harm behavior in patients with BPD, an important question is whether the absence of this criterion, which might attenuate the likelihood of recognizing and diagnosing the disorder, identifies a subgroup of patients with BPD who are ‘less borderline’ than patients with BPD who do not manifest this criterion,” the investigators write.

The researchers wanted to see if a similar finding applied to self-injury and suicidal behavior and turned to the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with BPD who do and do not engage in repeated suicidal and self-harm behavior.

MIDAS project

The study population was derived from 3,800 psychiatric outpatients who had been evaluated in the MIDAS project with semi-structured diagnostic interviews.

Of these, 390 patients were diagnosed with BPD. Since the suicidality/self-harm item was not rated in one patient, the analyzed sample consisted of 389 individuals with BPD (28.3% male; mean age, 32.6 years; 86.3% White). A little more than half the participants (54%) met the BPD suicidality/ self-harm criterion.

Only one-fifth (20.5%) of patients with BPD presented with a chief complaint that was related to a feature of BPD and had received BPD as their principal diagnosis.

Patients who met the suicidality/self-injury criterion were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with BPD as the principal diagnosis, compared with those who did not have that criterion (24.8% vs. 14.5%, respectively; P < .01).

On the other hand, there was no difference in the mean number of BPD criteria that were met, other than suicidality/self-harm, between those who did and did not present with suicidality/self-harm (5.5 ± 1.2 vs. 5.7 ± 0.8, t = 1.44). The investigators note that this finding was “not significant.”

There also was no difference between patients who did and did not meet the criterion in number of psychiatric diagnoses at time of evaluation (3.4 ± 1.9 vs. 3.5 ± 1.8, t = 0.56).

Hidden BPD

Similarly, there was no difference in any specific Axis I or personality disorder – except for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and histrionic personality disorder. Both were more frequent in the patients who did not meet the suicidality/self-injury criterion. However, after controlling for age, the group difference in GAD was no longer deemed significant (F = 3.45, P = .064).

By contrast, histrionic personality disorder remained significant with age as the covariate (F = 6.03, P = .015).

“The patients who met the suicidality/self-injury criterion were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized and reported more suicidal ideation at the time of the evaluation,” the researchers write. Both variables remained significant even after including age as a covariate.

There were no between-group differences on severity of depression, anxiety, or anger at initial evaluation nor were there differences in social functioning, adolescent social functioning, likelihood of persistent unemployment or receiving disability payments, childhood trauma, or neglect.

“I suspect that there are a number of individuals whose BPD is not recognized because they don’t have the more overt feature of self-injury or suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Zimmerman, noting that these patients might be considered as having “hidden” BPD.

“Repeated self-injurious and suicidal behavior is not synonymous with BPD, and clinicians should be aware that the absence of these behaviors does not rule out a diagnosis of BPD,” he added.

Stigmatizing diagnosis?

Monica Carsky, PhD, clinical assistant professor of psychology in psychiatry and senior fellow, Personality Disorders Institute, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said the study “will be particularly useful in the education of clinicians about the characteristics of individuals with BPD.”

Dr. Carsky, who is also an adjunct assistant professor in the NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy, was not involved with the study. She noted that other factors “can contribute to misdiagnosis of the borderline patients who do not have suicidality/self-harm.”

Clinicians and patients “may see BPD as a stigmatizing diagnosis so that clinicians become reluctant to make, share, and explain this personality disorder diagnosis,” she said.

Dr. Carsky suggested that increasing use of the Alternate Model for Personality Disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), which first rates the severity level of personality by assessing identity and relationship problems and then notes traits of specific personality disorders, “will help clinicians who dread telling patients they are ‘borderline.’ ”

No source of study funding has been reported. The investigators and Dr. Carsky reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators compared characteristics of almost 400 psychiatric outpatients diagnosed with BPD. About half of the participants met the suicidality/self-injury diagnostic criterion for the disorder, while the other half did not.

Results showed no differences between the two groups in degree of impairment in occupational or social functioning, comorbid psychiatric disorders, history of childhood trauma, or severity of depression, anxiety, or anger.

“Just because a person doesn’t engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior doesn’t mean that the person is free of borderline personality disorder,” lead author Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“Clinicians need to screen for borderline personality disorder in patients with other suggestive symptoms, even if those patients don’t self-harm, just as they would for similar patients who do self-harm,” said Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the Outpatient Division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

The findings were published online in Psychological Medicine.

A ‘polythetic diagnosis’

Dr. Zimmerman noted the impetus for conducting the study originated with a patient he saw who had all of the features of BPD except for self-harm and suicidality. However, because she didn’t have those two features, she was told by her therapist she could not have BPD.

“This sparked the idea that perhaps there are other individuals whose BPD may not be recognized because they don’t engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

“Most individuals with BPD don’t present for treatment saying, ‘I’m here because I don’t have a sense of myself’ or ‘I feel empty inside’ – but they do say, ‘I’m here because I’m cutting myself’ or ‘I’m suicidal,’ ” he added.

The investigators wondered if there were other “hidden” cases of BPD that were being missed by therapists.

They had previously analyzed each diagnostic criterion for BPD to ascertain its sensitivity. “We had been interested in wanting to see whether there was a criterion so frequent in BPD that every patient with BPD has it,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

BPD is a “polythetic diagnosis,” he added. It is “based on a list of features, with a certain minimum number of those features necessary to make the diagnosis rather than one specific criterion.”

His group’s previous research showed affective instability criterion to be present in more than 90% of individuals with BPD. “It had a very high negative predictive value, meaning that if you didn’t have affective instability, you didn’t have the disorder,” he said.

“Given the clinical and public health significance of suicidal and self-harm behavior in patients with BPD, an important question is whether the absence of this criterion, which might attenuate the likelihood of recognizing and diagnosing the disorder, identifies a subgroup of patients with BPD who are ‘less borderline’ than patients with BPD who do not manifest this criterion,” the investigators write.

The researchers wanted to see if a similar finding applied to self-injury and suicidal behavior and turned to the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with BPD who do and do not engage in repeated suicidal and self-harm behavior.

MIDAS project

The study population was derived from 3,800 psychiatric outpatients who had been evaluated in the MIDAS project with semi-structured diagnostic interviews.

Of these, 390 patients were diagnosed with BPD. Since the suicidality/self-harm item was not rated in one patient, the analyzed sample consisted of 389 individuals with BPD (28.3% male; mean age, 32.6 years; 86.3% White). A little more than half the participants (54%) met the BPD suicidality/ self-harm criterion.

Only one-fifth (20.5%) of patients with BPD presented with a chief complaint that was related to a feature of BPD and had received BPD as their principal diagnosis.

Patients who met the suicidality/self-injury criterion were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with BPD as the principal diagnosis, compared with those who did not have that criterion (24.8% vs. 14.5%, respectively; P < .01).

On the other hand, there was no difference in the mean number of BPD criteria that were met, other than suicidality/self-harm, between those who did and did not present with suicidality/self-harm (5.5 ± 1.2 vs. 5.7 ± 0.8, t = 1.44). The investigators note that this finding was “not significant.”

There also was no difference between patients who did and did not meet the criterion in number of psychiatric diagnoses at time of evaluation (3.4 ± 1.9 vs. 3.5 ± 1.8, t = 0.56).

Hidden BPD

Similarly, there was no difference in any specific Axis I or personality disorder – except for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and histrionic personality disorder. Both were more frequent in the patients who did not meet the suicidality/self-injury criterion. However, after controlling for age, the group difference in GAD was no longer deemed significant (F = 3.45, P = .064).

By contrast, histrionic personality disorder remained significant with age as the covariate (F = 6.03, P = .015).

“The patients who met the suicidality/self-injury criterion were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized and reported more suicidal ideation at the time of the evaluation,” the researchers write. Both variables remained significant even after including age as a covariate.

There were no between-group differences on severity of depression, anxiety, or anger at initial evaluation nor were there differences in social functioning, adolescent social functioning, likelihood of persistent unemployment or receiving disability payments, childhood trauma, or neglect.

“I suspect that there are a number of individuals whose BPD is not recognized because they don’t have the more overt feature of self-injury or suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Zimmerman, noting that these patients might be considered as having “hidden” BPD.

“Repeated self-injurious and suicidal behavior is not synonymous with BPD, and clinicians should be aware that the absence of these behaviors does not rule out a diagnosis of BPD,” he added.

Stigmatizing diagnosis?

Monica Carsky, PhD, clinical assistant professor of psychology in psychiatry and senior fellow, Personality Disorders Institute, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said the study “will be particularly useful in the education of clinicians about the characteristics of individuals with BPD.”

Dr. Carsky, who is also an adjunct assistant professor in the NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy, was not involved with the study. She noted that other factors “can contribute to misdiagnosis of the borderline patients who do not have suicidality/self-harm.”

Clinicians and patients “may see BPD as a stigmatizing diagnosis so that clinicians become reluctant to make, share, and explain this personality disorder diagnosis,” she said.

Dr. Carsky suggested that increasing use of the Alternate Model for Personality Disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), which first rates the severity level of personality by assessing identity and relationship problems and then notes traits of specific personality disorders, “will help clinicians who dread telling patients they are ‘borderline.’ ”

No source of study funding has been reported. The investigators and Dr. Carsky reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

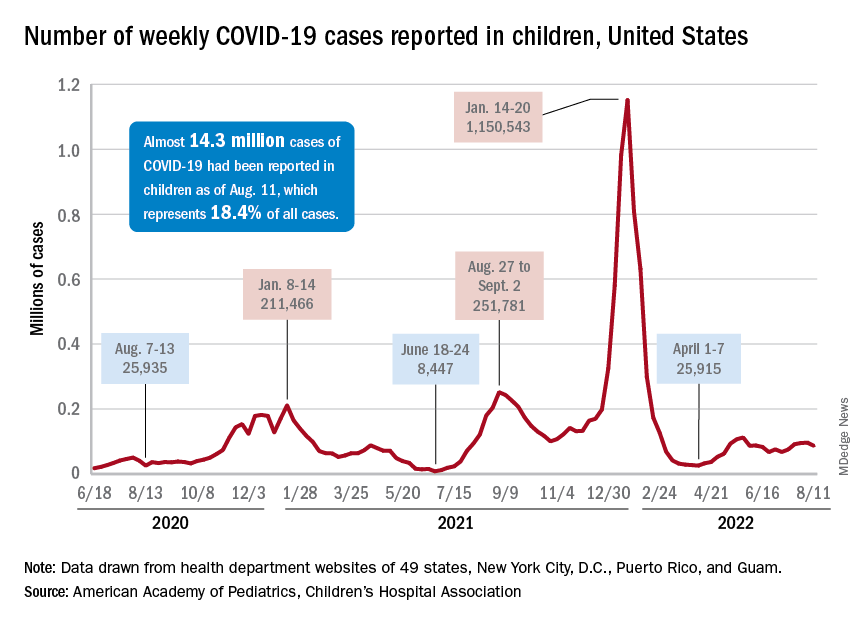

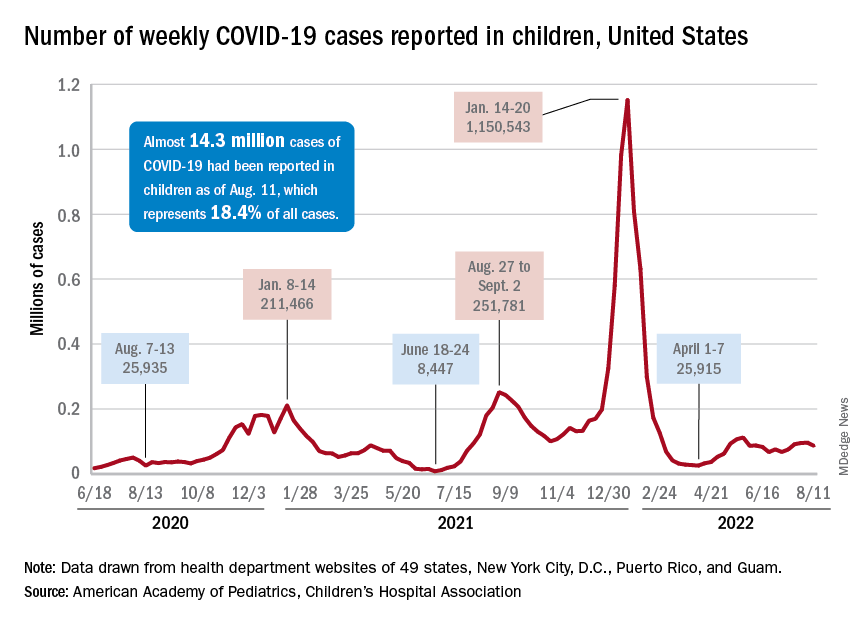

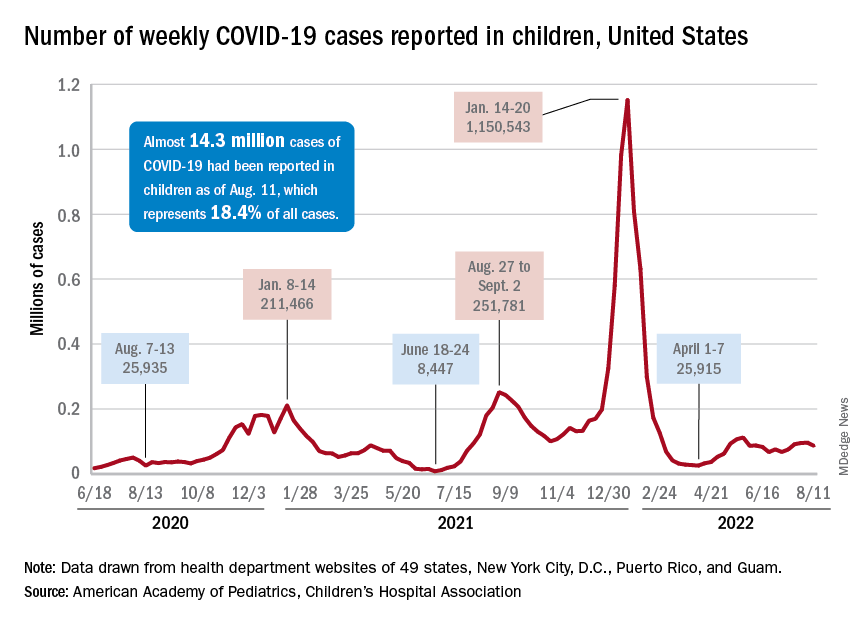

Children and COVID: ED visits and new admissions change course

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Hearing aids available in October without a prescription

The White House announced today that the Food and Drug Administration will move forward with plans to make hearing aids available over the counter in pharmacies, other retail locations, and online.

This major milestone aims to make hearing aids easier to buy and more affordable, potentially saving families thousands of dollars.

An estimated 28.8 million U.S. adults could benefit from using hearing aids, according to numbers from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. But only about 16% of people aged 20-69 years who could be helped by hearing aids have ever used them.

The risk for hearing loss increases with age. Among Americans ages 70 and older, only 30% who could hear better with these devices have ever used them, the institute reports.

Once the FDA final rule takes effect, Americans with mild to moderate hearing loss will be able to buy a hearing aid without a doctor’s exam, prescription, or fitting adjustment.

President Joe Biden announced in 2021 he intended to allow hearing aids to be sold over the counter without a prescription to increase competition among manufacturers. Congress also passed bipartisan legislation in 2017 requiring the FDA to create a new category for hearing aids sold directly to consumers. Some devices intended for minors or people with severe hearing loss will remain available only with a prescription.

“This action makes good on my commitment to lower costs for American families, delivering nearly $3,000 in savings to American families for a pair of hearing aids and giving people more choices to improve their health and wellbeing,” the president said in a statement announcing the news.

The new over-the-counter hearing aids will be considered medical devices. To avoid confusion, the FDA explains the differences between hearing aids and personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). For example, PSAPs are considered electronic devices designed for people with normal hearing to use in certain situations, like birdwatching or hunting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The White House announced today that the Food and Drug Administration will move forward with plans to make hearing aids available over the counter in pharmacies, other retail locations, and online.

This major milestone aims to make hearing aids easier to buy and more affordable, potentially saving families thousands of dollars.

An estimated 28.8 million U.S. adults could benefit from using hearing aids, according to numbers from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. But only about 16% of people aged 20-69 years who could be helped by hearing aids have ever used them.

The risk for hearing loss increases with age. Among Americans ages 70 and older, only 30% who could hear better with these devices have ever used them, the institute reports.

Once the FDA final rule takes effect, Americans with mild to moderate hearing loss will be able to buy a hearing aid without a doctor’s exam, prescription, or fitting adjustment.

President Joe Biden announced in 2021 he intended to allow hearing aids to be sold over the counter without a prescription to increase competition among manufacturers. Congress also passed bipartisan legislation in 2017 requiring the FDA to create a new category for hearing aids sold directly to consumers. Some devices intended for minors or people with severe hearing loss will remain available only with a prescription.

“This action makes good on my commitment to lower costs for American families, delivering nearly $3,000 in savings to American families for a pair of hearing aids and giving people more choices to improve their health and wellbeing,” the president said in a statement announcing the news.

The new over-the-counter hearing aids will be considered medical devices. To avoid confusion, the FDA explains the differences between hearing aids and personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). For example, PSAPs are considered electronic devices designed for people with normal hearing to use in certain situations, like birdwatching or hunting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The White House announced today that the Food and Drug Administration will move forward with plans to make hearing aids available over the counter in pharmacies, other retail locations, and online.

This major milestone aims to make hearing aids easier to buy and more affordable, potentially saving families thousands of dollars.

An estimated 28.8 million U.S. adults could benefit from using hearing aids, according to numbers from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. But only about 16% of people aged 20-69 years who could be helped by hearing aids have ever used them.

The risk for hearing loss increases with age. Among Americans ages 70 and older, only 30% who could hear better with these devices have ever used them, the institute reports.

Once the FDA final rule takes effect, Americans with mild to moderate hearing loss will be able to buy a hearing aid without a doctor’s exam, prescription, or fitting adjustment.

President Joe Biden announced in 2021 he intended to allow hearing aids to be sold over the counter without a prescription to increase competition among manufacturers. Congress also passed bipartisan legislation in 2017 requiring the FDA to create a new category for hearing aids sold directly to consumers. Some devices intended for minors or people with severe hearing loss will remain available only with a prescription.

“This action makes good on my commitment to lower costs for American families, delivering nearly $3,000 in savings to American families for a pair of hearing aids and giving people more choices to improve their health and wellbeing,” the president said in a statement announcing the news.

The new over-the-counter hearing aids will be considered medical devices. To avoid confusion, the FDA explains the differences between hearing aids and personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). For example, PSAPs are considered electronic devices designed for people with normal hearing to use in certain situations, like birdwatching or hunting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Psychiatrists’ income, net worth rise as COVID wanes

Last year brought welcome relief to psychiatrists, with incomes generally rising as practices reopened after COVID-19 restrictions lifted and patients ventured out of their homes.

Psychiatrists’ average annual income rose to $287,000, according to the Medscape Psychiatrist Wealth and Debt Report 2022. That is up about 4% from $275,000, which was listed in last year’s report.

However, psychiatrists still rank in the bottom third of all specialties when it comes to physicians’ income.

According to the overall Medscape Physician Wealth and Debt Report 2022, the highest-paying speciality is plastic surgery ($576,000), followed by orthopedics ($557,000) and cardiology ($490,000).

The lowest-paying areas of medicine are family medicine ($255,000), pediatrics ($244,000), and public health and preventive medicine ($243,000).

The report is based on responses from more than 13,000 physicians in 29 specialties. All were surveyed between Oct. 5, 2021 and Jan. 19, 2022.

Money-conscious?

Similar to last year’s report, three-quarters of psychiatrists have not done anything to reduce major expenses. Those who have taken cost-cutting measures cited deferring or refinancing loans, moving to a different home, or changing cars as ways to do so.

Most psychiatrists (80%) reported having avoided major financial losses, which is up slightly from last year (76%). Only 6% of psychiatrists (9% last year) reported monetary losses because of issues at their medical practice.

One-quarter reported having a stock or corporate investment go south, which is about the same as last year. In addition, 42% said that they have yet to make a particular investment mistake and 19% said that they have not made any investments.

This year, a somewhat smaller percentage of psychiatrists reported keeping their rates of saving in after-tax accounts level or at increased rates, compared with last year (47% vs. 52%).

About 28% of psychiatrists do not regularly put money into after-tax savings accounts, compared with 25% of physicians overall.

The vast majority said that they kept up with bills amid COVID, as they also did last year.

The percentage of psychiatrists who paid mortgages or other bills late during the pandemic is about the same this year as last year (3% and 5%, respectively).

That is in contrast to one 2021 industry survey, which showed that 46% of Americans missed one or more rent or mortgage payments because of COVID.

Other key findings from Medscape’s latest psychiatrist wealth and debt report include that:

- 61% live in a home of 3,000 square feet or less, which is greater that the current average size of a U.S. house (2,261 square feet)

- 22% have one or two credit cards and 42% have five or more credit cards, while the average American has four cards

- 63% differ in opinion, at least sporadically, with their significant other about spending. A Northwestern Mutual study showed that across the country, around 1 in 4 couples argue about money at least once a month.

In addition, 70% of psychiatrists said that they typically tip at least the recommended 20% for decent service, which is somewhat more generous than the average physician (64%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year brought welcome relief to psychiatrists, with incomes generally rising as practices reopened after COVID-19 restrictions lifted and patients ventured out of their homes.

Psychiatrists’ average annual income rose to $287,000, according to the Medscape Psychiatrist Wealth and Debt Report 2022. That is up about 4% from $275,000, which was listed in last year’s report.

However, psychiatrists still rank in the bottom third of all specialties when it comes to physicians’ income.

According to the overall Medscape Physician Wealth and Debt Report 2022, the highest-paying speciality is plastic surgery ($576,000), followed by orthopedics ($557,000) and cardiology ($490,000).

The lowest-paying areas of medicine are family medicine ($255,000), pediatrics ($244,000), and public health and preventive medicine ($243,000).

The report is based on responses from more than 13,000 physicians in 29 specialties. All were surveyed between Oct. 5, 2021 and Jan. 19, 2022.

Money-conscious?

Similar to last year’s report, three-quarters of psychiatrists have not done anything to reduce major expenses. Those who have taken cost-cutting measures cited deferring or refinancing loans, moving to a different home, or changing cars as ways to do so.

Most psychiatrists (80%) reported having avoided major financial losses, which is up slightly from last year (76%). Only 6% of psychiatrists (9% last year) reported monetary losses because of issues at their medical practice.

One-quarter reported having a stock or corporate investment go south, which is about the same as last year. In addition, 42% said that they have yet to make a particular investment mistake and 19% said that they have not made any investments.

This year, a somewhat smaller percentage of psychiatrists reported keeping their rates of saving in after-tax accounts level or at increased rates, compared with last year (47% vs. 52%).

About 28% of psychiatrists do not regularly put money into after-tax savings accounts, compared with 25% of physicians overall.

The vast majority said that they kept up with bills amid COVID, as they also did last year.

The percentage of psychiatrists who paid mortgages or other bills late during the pandemic is about the same this year as last year (3% and 5%, respectively).

That is in contrast to one 2021 industry survey, which showed that 46% of Americans missed one or more rent or mortgage payments because of COVID.

Other key findings from Medscape’s latest psychiatrist wealth and debt report include that:

- 61% live in a home of 3,000 square feet or less, which is greater that the current average size of a U.S. house (2,261 square feet)

- 22% have one or two credit cards and 42% have five or more credit cards, while the average American has four cards

- 63% differ in opinion, at least sporadically, with their significant other about spending. A Northwestern Mutual study showed that across the country, around 1 in 4 couples argue about money at least once a month.

In addition, 70% of psychiatrists said that they typically tip at least the recommended 20% for decent service, which is somewhat more generous than the average physician (64%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year brought welcome relief to psychiatrists, with incomes generally rising as practices reopened after COVID-19 restrictions lifted and patients ventured out of their homes.

Psychiatrists’ average annual income rose to $287,000, according to the Medscape Psychiatrist Wealth and Debt Report 2022. That is up about 4% from $275,000, which was listed in last year’s report.

However, psychiatrists still rank in the bottom third of all specialties when it comes to physicians’ income.

According to the overall Medscape Physician Wealth and Debt Report 2022, the highest-paying speciality is plastic surgery ($576,000), followed by orthopedics ($557,000) and cardiology ($490,000).

The lowest-paying areas of medicine are family medicine ($255,000), pediatrics ($244,000), and public health and preventive medicine ($243,000).

The report is based on responses from more than 13,000 physicians in 29 specialties. All were surveyed between Oct. 5, 2021 and Jan. 19, 2022.

Money-conscious?

Similar to last year’s report, three-quarters of psychiatrists have not done anything to reduce major expenses. Those who have taken cost-cutting measures cited deferring or refinancing loans, moving to a different home, or changing cars as ways to do so.

Most psychiatrists (80%) reported having avoided major financial losses, which is up slightly from last year (76%). Only 6% of psychiatrists (9% last year) reported monetary losses because of issues at their medical practice.

One-quarter reported having a stock or corporate investment go south, which is about the same as last year. In addition, 42% said that they have yet to make a particular investment mistake and 19% said that they have not made any investments.

This year, a somewhat smaller percentage of psychiatrists reported keeping their rates of saving in after-tax accounts level or at increased rates, compared with last year (47% vs. 52%).

About 28% of psychiatrists do not regularly put money into after-tax savings accounts, compared with 25% of physicians overall.

The vast majority said that they kept up with bills amid COVID, as they also did last year.

The percentage of psychiatrists who paid mortgages or other bills late during the pandemic is about the same this year as last year (3% and 5%, respectively).

That is in contrast to one 2021 industry survey, which showed that 46% of Americans missed one or more rent or mortgage payments because of COVID.

Other key findings from Medscape’s latest psychiatrist wealth and debt report include that:

- 61% live in a home of 3,000 square feet or less, which is greater that the current average size of a U.S. house (2,261 square feet)

- 22% have one or two credit cards and 42% have five or more credit cards, while the average American has four cards

- 63% differ in opinion, at least sporadically, with their significant other about spending. A Northwestern Mutual study showed that across the country, around 1 in 4 couples argue about money at least once a month.

In addition, 70% of psychiatrists said that they typically tip at least the recommended 20% for decent service, which is somewhat more generous than the average physician (64%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prematurity, family environment linked to lower rate of school readiness

Among children born prematurely, rates of school readiness were lower, compared with rates for children born full term, new data indicate.

In a Canadian cohort study that included more than 60,000 children, 35% of children born prematurely had scores on the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that indicated they were vulnerable to developmental problems, compared with 28% of children born full term.

“Our take-home message is that being born prematurely, even if all was well, is a risk factor for not being ready for school, and these families should be identified early, screened for any difficulties, and offered early intervention,” senior author Chelsea A. Ruth, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Gestational age gradient

The investigators examined two cohorts of children who were in kindergarten at the time of data collection. One of them, the population-based cohort, included children born between 2000 and 2011 whose school readiness was assessed using the EDI data. Preterm birth was defined as a gestational age (GA) of less than 37 weeks. The other, the sibling cohort, was a subset of the population cohort and included children born prematurely and their closest-in-age siblings who were born full term.

The main outcome was vulnerability in the EDI, which was defined as having a score below the 10th percentile of the Canadian population norms for one or more of the five EDI domains. These domains are physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

A total of 63,277 children were included in the analyses, of whom 4,352 were born prematurely (mean GA, 34 weeks; 53% boys) and 58,925 were born full term (mean GA, 39 weeks; 51% boys).

After data adjustment, 35% of children born prematurely were vulnerable in the EDI, compared with 28% of those born full term (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32).

The investigators found a clear GA gradient. Children born at earlier GAs (< 28 weeks or 28-33 weeks) were at higher risk of being vulnerable than those born at later GAs (34-36 weeks) in any EDI domain (48% vs. 40%) and in each of the five EDI domains. Earlier GA was associated with greater risk for vulnerability in physical health and well-being (34% vs. 22%) and in the Multiple Challenge Index (25% vs. 17%). It also was associated with greater risk for need for additional support in kindergarten (22% vs. 5%).

Furthermore, 12% of children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation were vulnerable in two EDI domains, and 8% were vulnerable in three domains. The corresponding proportions were 9% and 7%, respectively, for those born between 28 and 33 weeks and 7% and 5% for those born between 34 and 36 weeks.

“The study confirmed what we see in practice, that being born even a little bit early increases the chance for not being ready for school, and the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to have troubles,” said Dr. Ruth.

Cause or manifestation?

In the population cohort, prematurity (< 34 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.72; 34-36 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.23), male sex (AOR, 2.24), small for GA (AOR, 1.31), and various maternal medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with EDI vulnerability.

In the sibling subset, EDI outcomes were similar for children born prematurely and their siblings born full term, except for the communication skills and general knowledge domain (AOR, 1.39) and the Multiple Challenge Index (AOR, 1.43). Male sex (AOR, 2.19) was associated with EDI vulnerability in this cohort as well, as was maternal age at delivery (AOR, 1.53).

“Whether prematurity is a cause or a manifestation of an altered family ecosystem is difficult to ascertain,” Lauren Neel, MD, a neonatologist at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues write in an accompanying editorial. “However, research on this topic is much needed, along with novel interventions to change academic trajectories and care models that implement these findings in practice. As we begin to understand the factors in and interventions for promoting resilience in preterm-born children, we may need to change our research question to this: Could we optimize resilience and long-term academic trajectories to include the family as well?”

Six crucial years

Commenting on the study, Veronica Bordes Edgar, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, Dallas, said, “None of the findings surprised me, but I was very pleased that they looked at such a broad sample.”

Pediatricians should monitor and screen children for early academic readiness, since these factors are associated with later academic outcomes, Dr. Edgar added. “Early intervention does not stop at age 3, but rather the first 6 years are so crucial to lay the foundation for future success. The pediatrician can play a role in preparing children and families by promoting early reading, such as through Reach Out and Read, encouraging language-rich play, and providing guidance on early childhood education and developmental needs.

“Further examination of long-term outcomes for these children to capture the longitudinal trend would help to document what is often observed clinically, in that children who start off with difficulties do not always catch up once they are in the academic environment,” Dr. Edgar concluded.

The study was supported by Research Manitoba and the Children’s Research Institute of Manitoba. Dr. Ruth, Dr. Neel, and Dr. Edgar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among children born prematurely, rates of school readiness were lower, compared with rates for children born full term, new data indicate.

In a Canadian cohort study that included more than 60,000 children, 35% of children born prematurely had scores on the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that indicated they were vulnerable to developmental problems, compared with 28% of children born full term.

“Our take-home message is that being born prematurely, even if all was well, is a risk factor for not being ready for school, and these families should be identified early, screened for any difficulties, and offered early intervention,” senior author Chelsea A. Ruth, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Gestational age gradient

The investigators examined two cohorts of children who were in kindergarten at the time of data collection. One of them, the population-based cohort, included children born between 2000 and 2011 whose school readiness was assessed using the EDI data. Preterm birth was defined as a gestational age (GA) of less than 37 weeks. The other, the sibling cohort, was a subset of the population cohort and included children born prematurely and their closest-in-age siblings who were born full term.

The main outcome was vulnerability in the EDI, which was defined as having a score below the 10th percentile of the Canadian population norms for one or more of the five EDI domains. These domains are physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

A total of 63,277 children were included in the analyses, of whom 4,352 were born prematurely (mean GA, 34 weeks; 53% boys) and 58,925 were born full term (mean GA, 39 weeks; 51% boys).

After data adjustment, 35% of children born prematurely were vulnerable in the EDI, compared with 28% of those born full term (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32).

The investigators found a clear GA gradient. Children born at earlier GAs (< 28 weeks or 28-33 weeks) were at higher risk of being vulnerable than those born at later GAs (34-36 weeks) in any EDI domain (48% vs. 40%) and in each of the five EDI domains. Earlier GA was associated with greater risk for vulnerability in physical health and well-being (34% vs. 22%) and in the Multiple Challenge Index (25% vs. 17%). It also was associated with greater risk for need for additional support in kindergarten (22% vs. 5%).

Furthermore, 12% of children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation were vulnerable in two EDI domains, and 8% were vulnerable in three domains. The corresponding proportions were 9% and 7%, respectively, for those born between 28 and 33 weeks and 7% and 5% for those born between 34 and 36 weeks.

“The study confirmed what we see in practice, that being born even a little bit early increases the chance for not being ready for school, and the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to have troubles,” said Dr. Ruth.

Cause or manifestation?

In the population cohort, prematurity (< 34 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.72; 34-36 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.23), male sex (AOR, 2.24), small for GA (AOR, 1.31), and various maternal medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with EDI vulnerability.

In the sibling subset, EDI outcomes were similar for children born prematurely and their siblings born full term, except for the communication skills and general knowledge domain (AOR, 1.39) and the Multiple Challenge Index (AOR, 1.43). Male sex (AOR, 2.19) was associated with EDI vulnerability in this cohort as well, as was maternal age at delivery (AOR, 1.53).

“Whether prematurity is a cause or a manifestation of an altered family ecosystem is difficult to ascertain,” Lauren Neel, MD, a neonatologist at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues write in an accompanying editorial. “However, research on this topic is much needed, along with novel interventions to change academic trajectories and care models that implement these findings in practice. As we begin to understand the factors in and interventions for promoting resilience in preterm-born children, we may need to change our research question to this: Could we optimize resilience and long-term academic trajectories to include the family as well?”

Six crucial years

Commenting on the study, Veronica Bordes Edgar, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, Dallas, said, “None of the findings surprised me, but I was very pleased that they looked at such a broad sample.”

Pediatricians should monitor and screen children for early academic readiness, since these factors are associated with later academic outcomes, Dr. Edgar added. “Early intervention does not stop at age 3, but rather the first 6 years are so crucial to lay the foundation for future success. The pediatrician can play a role in preparing children and families by promoting early reading, such as through Reach Out and Read, encouraging language-rich play, and providing guidance on early childhood education and developmental needs.

“Further examination of long-term outcomes for these children to capture the longitudinal trend would help to document what is often observed clinically, in that children who start off with difficulties do not always catch up once they are in the academic environment,” Dr. Edgar concluded.

The study was supported by Research Manitoba and the Children’s Research Institute of Manitoba. Dr. Ruth, Dr. Neel, and Dr. Edgar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among children born prematurely, rates of school readiness were lower, compared with rates for children born full term, new data indicate.

In a Canadian cohort study that included more than 60,000 children, 35% of children born prematurely had scores on the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that indicated they were vulnerable to developmental problems, compared with 28% of children born full term.

“Our take-home message is that being born prematurely, even if all was well, is a risk factor for not being ready for school, and these families should be identified early, screened for any difficulties, and offered early intervention,” senior author Chelsea A. Ruth, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Gestational age gradient

The investigators examined two cohorts of children who were in kindergarten at the time of data collection. One of them, the population-based cohort, included children born between 2000 and 2011 whose school readiness was assessed using the EDI data. Preterm birth was defined as a gestational age (GA) of less than 37 weeks. The other, the sibling cohort, was a subset of the population cohort and included children born prematurely and their closest-in-age siblings who were born full term.

The main outcome was vulnerability in the EDI, which was defined as having a score below the 10th percentile of the Canadian population norms for one or more of the five EDI domains. These domains are physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

A total of 63,277 children were included in the analyses, of whom 4,352 were born prematurely (mean GA, 34 weeks; 53% boys) and 58,925 were born full term (mean GA, 39 weeks; 51% boys).

After data adjustment, 35% of children born prematurely were vulnerable in the EDI, compared with 28% of those born full term (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32).

The investigators found a clear GA gradient. Children born at earlier GAs (< 28 weeks or 28-33 weeks) were at higher risk of being vulnerable than those born at later GAs (34-36 weeks) in any EDI domain (48% vs. 40%) and in each of the five EDI domains. Earlier GA was associated with greater risk for vulnerability in physical health and well-being (34% vs. 22%) and in the Multiple Challenge Index (25% vs. 17%). It also was associated with greater risk for need for additional support in kindergarten (22% vs. 5%).

Furthermore, 12% of children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation were vulnerable in two EDI domains, and 8% were vulnerable in three domains. The corresponding proportions were 9% and 7%, respectively, for those born between 28 and 33 weeks and 7% and 5% for those born between 34 and 36 weeks.

“The study confirmed what we see in practice, that being born even a little bit early increases the chance for not being ready for school, and the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to have troubles,” said Dr. Ruth.

Cause or manifestation?

In the population cohort, prematurity (< 34 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.72; 34-36 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.23), male sex (AOR, 2.24), small for GA (AOR, 1.31), and various maternal medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with EDI vulnerability.

In the sibling subset, EDI outcomes were similar for children born prematurely and their siblings born full term, except for the communication skills and general knowledge domain (AOR, 1.39) and the Multiple Challenge Index (AOR, 1.43). Male sex (AOR, 2.19) was associated with EDI vulnerability in this cohort as well, as was maternal age at delivery (AOR, 1.53).

“Whether prematurity is a cause or a manifestation of an altered family ecosystem is difficult to ascertain,” Lauren Neel, MD, a neonatologist at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues write in an accompanying editorial. “However, research on this topic is much needed, along with novel interventions to change academic trajectories and care models that implement these findings in practice. As we begin to understand the factors in and interventions for promoting resilience in preterm-born children, we may need to change our research question to this: Could we optimize resilience and long-term academic trajectories to include the family as well?”

Six crucial years

Commenting on the study, Veronica Bordes Edgar, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, Dallas, said, “None of the findings surprised me, but I was very pleased that they looked at such a broad sample.”

Pediatricians should monitor and screen children for early academic readiness, since these factors are associated with later academic outcomes, Dr. Edgar added. “Early intervention does not stop at age 3, but rather the first 6 years are so crucial to lay the foundation for future success. The pediatrician can play a role in preparing children and families by promoting early reading, such as through Reach Out and Read, encouraging language-rich play, and providing guidance on early childhood education and developmental needs.

“Further examination of long-term outcomes for these children to capture the longitudinal trend would help to document what is often observed clinically, in that children who start off with difficulties do not always catch up once they are in the academic environment,” Dr. Edgar concluded.

The study was supported by Research Manitoba and the Children’s Research Institute of Manitoba. Dr. Ruth, Dr. Neel, and Dr. Edgar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Dig like an archaeologist

You can observe a lot by watching. – Yogi Berra

He was a fit man in his 40s. Thick legs. Maybe he was a long-distance walker? The bones of his right arm were more developed than his left – a right-handed thrower. His lower left fibula was fractured from a severely rolled ankle. He carried a walking stick that was glossy in the middle from where he gripped it with his left hand, dragging his bad left foot along. Dental cavities tell the story of his diet: honey, carobs, dates. Carbon 14 dating confirms that he lived during the Chalcolithic period, approximately 6,000 years ago. He was likely a shepherd in the Judean Desert.

Isn’t it amazing how much we can know about another human even across such an enormous chasm of time? If you’d asked me when I was 11 what I wanted to be, I’d have said archaeologist. .

A 64-year-old woman with a 4-cm red, brown shiny plaque on her right calf. She burned it on her boyfriend’s Harley Davidson nearly 40 years ago. She wonders where he is now.

A 58-year-old man with a 3-inch scar on his right wrist. He fell off his 6-year-old’s skimboard. ORIF.

A 40-year-old woman with bilateral mastectomy scars.

A 66-year-old with a lichenified nodule on his left forearm. When I shaved it off, a quarter inch spicule of glass came out. It was from a car accident in his first car, a Chevy Impala. He saved the piece of glass as a souvenir.

A fit 50-year-old with extensive scars on his feet and ankles. “Yeah, I went ‘whistling-in’ on a training jump,” he said. He was a retired Navy Seal and raconteur with quite a tale about the day his parachute malfunctioned. Some well placed live oak trees is why he’s around for his skin screening.

A classic, rope-like open-heart scar on the chest of a thin, young, healthy, flaxen-haired woman. Dissected aorta.

A 30-something woman dressed in a pants suit with razor-thin parallel scars on her volar forearms and proximal thighs. She asks if any laser could remove them.

A rotund, hard-living, bearded man with chest and upper-arm tattoos of flames and nudie girls now mixed with the striking face of an old woman and three little kids: His mom and grandkids. He shows me where the fourth grandkid will go and gives me a bear hug to thank me for the care when he leaves.

Attending to these details shifts us from autopilot to present. It keeps us involved, holding our attention even if it’s the 20th skin screening or diabetic foot exam of the day. And what a gift to share in the intimate details of another’s life.

Like examining the minute details of an ancient bone, dig for the history with curiosity, pity, humility. The perfect moment for asking might be when you stand with your #15 blade ready to introduce a new scar and become part of this human’s story forever.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

You can observe a lot by watching. – Yogi Berra

He was a fit man in his 40s. Thick legs. Maybe he was a long-distance walker? The bones of his right arm were more developed than his left – a right-handed thrower. His lower left fibula was fractured from a severely rolled ankle. He carried a walking stick that was glossy in the middle from where he gripped it with his left hand, dragging his bad left foot along. Dental cavities tell the story of his diet: honey, carobs, dates. Carbon 14 dating confirms that he lived during the Chalcolithic period, approximately 6,000 years ago. He was likely a shepherd in the Judean Desert.

Isn’t it amazing how much we can know about another human even across such an enormous chasm of time? If you’d asked me when I was 11 what I wanted to be, I’d have said archaeologist. .

A 64-year-old woman with a 4-cm red, brown shiny plaque on her right calf. She burned it on her boyfriend’s Harley Davidson nearly 40 years ago. She wonders where he is now.

A 58-year-old man with a 3-inch scar on his right wrist. He fell off his 6-year-old’s skimboard. ORIF.

A 40-year-old woman with bilateral mastectomy scars.

A 66-year-old with a lichenified nodule on his left forearm. When I shaved it off, a quarter inch spicule of glass came out. It was from a car accident in his first car, a Chevy Impala. He saved the piece of glass as a souvenir.

A fit 50-year-old with extensive scars on his feet and ankles. “Yeah, I went ‘whistling-in’ on a training jump,” he said. He was a retired Navy Seal and raconteur with quite a tale about the day his parachute malfunctioned. Some well placed live oak trees is why he’s around for his skin screening.

A classic, rope-like open-heart scar on the chest of a thin, young, healthy, flaxen-haired woman. Dissected aorta.

A 30-something woman dressed in a pants suit with razor-thin parallel scars on her volar forearms and proximal thighs. She asks if any laser could remove them.

A rotund, hard-living, bearded man with chest and upper-arm tattoos of flames and nudie girls now mixed with the striking face of an old woman and three little kids: His mom and grandkids. He shows me where the fourth grandkid will go and gives me a bear hug to thank me for the care when he leaves.

Attending to these details shifts us from autopilot to present. It keeps us involved, holding our attention even if it’s the 20th skin screening or diabetic foot exam of the day. And what a gift to share in the intimate details of another’s life.

Like examining the minute details of an ancient bone, dig for the history with curiosity, pity, humility. The perfect moment for asking might be when you stand with your #15 blade ready to introduce a new scar and become part of this human’s story forever.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

You can observe a lot by watching. – Yogi Berra

He was a fit man in his 40s. Thick legs. Maybe he was a long-distance walker? The bones of his right arm were more developed than his left – a right-handed thrower. His lower left fibula was fractured from a severely rolled ankle. He carried a walking stick that was glossy in the middle from where he gripped it with his left hand, dragging his bad left foot along. Dental cavities tell the story of his diet: honey, carobs, dates. Carbon 14 dating confirms that he lived during the Chalcolithic period, approximately 6,000 years ago. He was likely a shepherd in the Judean Desert.

Isn’t it amazing how much we can know about another human even across such an enormous chasm of time? If you’d asked me when I was 11 what I wanted to be, I’d have said archaeologist. .

A 64-year-old woman with a 4-cm red, brown shiny plaque on her right calf. She burned it on her boyfriend’s Harley Davidson nearly 40 years ago. She wonders where he is now.

A 58-year-old man with a 3-inch scar on his right wrist. He fell off his 6-year-old’s skimboard. ORIF.

A 40-year-old woman with bilateral mastectomy scars.

A 66-year-old with a lichenified nodule on his left forearm. When I shaved it off, a quarter inch spicule of glass came out. It was from a car accident in his first car, a Chevy Impala. He saved the piece of glass as a souvenir.

A fit 50-year-old with extensive scars on his feet and ankles. “Yeah, I went ‘whistling-in’ on a training jump,” he said. He was a retired Navy Seal and raconteur with quite a tale about the day his parachute malfunctioned. Some well placed live oak trees is why he’s around for his skin screening.

A classic, rope-like open-heart scar on the chest of a thin, young, healthy, flaxen-haired woman. Dissected aorta.

A 30-something woman dressed in a pants suit with razor-thin parallel scars on her volar forearms and proximal thighs. She asks if any laser could remove them.

A rotund, hard-living, bearded man with chest and upper-arm tattoos of flames and nudie girls now mixed with the striking face of an old woman and three little kids: His mom and grandkids. He shows me where the fourth grandkid will go and gives me a bear hug to thank me for the care when he leaves.

Attending to these details shifts us from autopilot to present. It keeps us involved, holding our attention even if it’s the 20th skin screening or diabetic foot exam of the day. And what a gift to share in the intimate details of another’s life.

Like examining the minute details of an ancient bone, dig for the history with curiosity, pity, humility. The perfect moment for asking might be when you stand with your #15 blade ready to introduce a new scar and become part of this human’s story forever.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Diagnosing children with long COVID can be tricky: Experts

When Spencer Siedlecki got COVID-19 in March 2021, he was sick for weeks with extreme fatigue, fevers, a sore throat, bad headaches, nausea, and eventually, pneumonia.

That was scary enough for the then-13-year-old and his parents, who live in Ohio. More than a year later, Spencer still had many of the symptoms and, more alarming, the once-healthy teen had postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a condition that has caused dizziness, a racing heart when he stands, and fainting. Spencer missed most of the last few months of eighth grade because of long COVID.

“He gets sick very easily,” said his mother, Melissa Siedlecki, who works in technology sales. “The common cold that he would shake off in a few days takes weeks for him to feel better.”

The transformation from regular teen life to someone with a chronic illness “sucked,” said Spencer, who will turn 15 in August. “I felt like I was never going to get better.” Fortunately, after some therapy at a specialized clinic, Spencer is back to playing baseball and golf.

Spencer’s journey to better health was difficult; his regular pediatrician told the family at first that there were no treatments to help him – a reaction that is not uncommon. “I still get a lot of parents who heard of me through the grapevine,” said Amy Edwards, MD, director of the pediatric COVID clinic at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland. “The pediatricians either are unsure of what is wrong, or worse, tell children ‘there is nothing wrong with you. Stop faking it.’ ” Dr. Edwards treated Spencer after his mother found the clinic through an internet search.

Alexandra Yonts, MD, a pediatric infectious diseases doctor and director of the post-COVID program clinic at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, has seen this too. she said.

But those who do get attention tend to be White and affluent, something Dr. Yonts said “doesn’t jibe with the epidemiologic data of who COVID has affected the most.” Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native children are more likely to be infected with COVID than White children, and have higher rates of hospitalization and death than White children.

It’s not clear whether these children have a particular risk factor, or if they are just the ones who have the resources to get to the clinics. But Dr. Yonts and Dr. Edwards believe many children are not getting the help they need. High-performing kids are coming in “because they are the ones whose symptoms are most obvious,” said Dr. Edwards. “I think there are kids out there who are getting missed because they’re already struggling because of socioeconomic reasons.”

Spencer is one of 14 million children who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 since the start of the pandemic. Many pediatricians are still grappling with how to address cases like Spencer’s. The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued only brief guidance on long COVID in children, in part because there have been so few studies to use as a basis for guidance.

The federal government is aiming to change that with a newly launched National Research Action Plan on Long COVID that includes speeding up research on how the condition affects children and youths, including their ability to learn and thrive.

A CDC study found children with COVID were significantly more likely to have smell and taste disturbances, circulatory system problems, fatigue and malaise, and pain. Those who had been infected had higher rates of acute blockage of a lung artery, myocarditis and weakening of the heart, kidney failure, and type 1 diabetes.

Difficult to diagnose

Even with increased media attention and more published studies on pediatric long COVID, it’s still hard for a busy primary care doctor “to sort through what could just be a cold or what could be a series of colds and trying to look at the bigger picture of what’s been going on in a 1- to 3-month period with a kid,” Dr. Yonts said.

Most children with potential or definite long COVID are still being seen by individual pediatricians, not in a specialized clinic with easy access to an army of specialists. It’s not clear how many of those pediatric clinics exist. Survivor Corps, an advocacy group for people with long COVID, has posted a map of locations providing care, but few are specialized or focus on pediatric long COVID.

Long COVID is different from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), which occurs within a month or so of infection, triggers high fevers and severe symptoms in the gut, and often results in hospitalization. MIS-C “is not subtle,” said Dr. Edwards.