User login

Acute otitis media pneumococcal disease burden in children due to serotypes not included in vaccines

My group in Rochester, N.Y., examined the current pneumococcal serotypes causing AOM in children. From our data, we can determine the PCV13 vaccine types that escape prevention and cause AOM and understand what effect to expect from the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) that will be coming soon. There are limited data from middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures on which to base such analyses. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for securing MEF for culture and our group is unique in providing such data to the Centers for Disease Control and publishing our results on a periodic basis to inform clinicians.

Pneumococci are the second most common cause of acute otitis media (AOM) since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) more than 2 decades ago.1,2 Pneumococcal AOM causes more severe acute disease and more often causes suppurative complications than Haemophilus influenzae, which is the most common cause of AOM. Prevention of pneumococcal AOM will be a highly relevant contributor to cost-effectiveness analyses for the anticipated introduction of PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer). Both PCV15 and PCV20 have been licensed for adult use; PCV15 licensure for infants and children occurred in June 2022 for invasive pneumococcal disease and is anticipated in the near future for PCV20. They are improvements over PCV13 because they add serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases, although less so for prevention of AOM, on the basis of our data.

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a necessary pathogenic step in progression to pneumococcal disease. However, not all strains of pneumococci expressing different capsular serotypes are equally virulent and likely to cause disease. In PCV-vaccinated populations, vaccine pressure and antibiotic resistance drive PCV serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs), gradually reducing the net effectiveness of the vaccines. Therefore, knowledge of prevalent NVTs colonizing the nasopharynx identifies future pneumococcal serotypes most likely to emerge as pathogenic.

We published an effectiveness study of PCV13.3 A relative reduction of 86% in AOM caused by strains expressing PCV13 serotypes was observed in the first few years after PCV13 introduction. The greatest reduction in MEF samples was in serotype 19A, with a relative reduction of 91%. However, over time the vaccine type efficacy of PCV13 against MEF-positive pneumococcal AOM has eroded. There was no clear efficacy against serotype 3, and we still observed cases of serotype 19A and 19F. PCV13 vaccine failures have been even more frequent in Europe (nearly 30% of pneumococcal AOM in Europe is caused by vaccine serotypes) than our data indicate, where about 10% of AOM is caused by PCV13 serotypes.

In our most recent publication covering 2015-2019, we described results from 589 children, aged 6-36 months, from whom we collected 2,042 nasopharyngeal samples.2,4 During AOM, 495 MEF samples from 319 AOM-infected children were collected (during bilateral infections, tympanocentesis was performed in both ears). Whether bacteria were isolated was based per AOM case, not per tap. The average age of children with AOM was 15 months (range 6-31 months). The three most prevalent nasopharyngeal pneumococcal serotypes were 35B, 23B, and 15B/C. Serotype 35B was the most common at AOM visits in both the nasopharynx and MEF samples followed by serotype 15B/C. Nonsusceptibility among pneumococci to penicillin, azithromycin, and multiple other antibiotics was high. Increasing resistance to ceftriaxone was also observed.

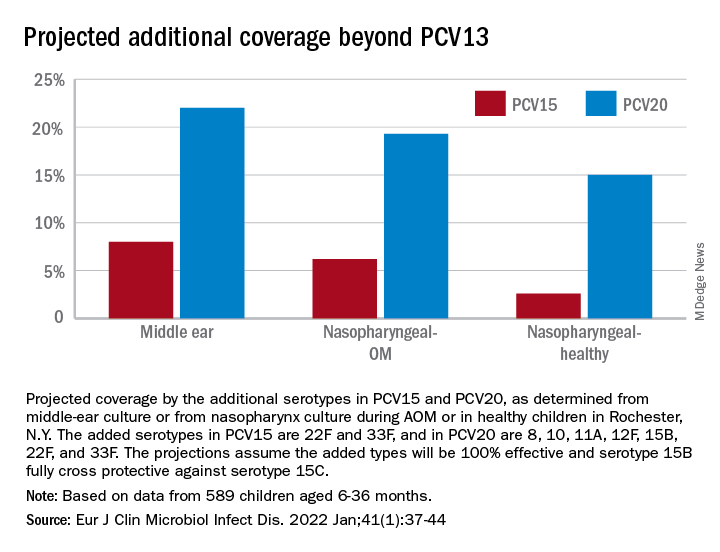

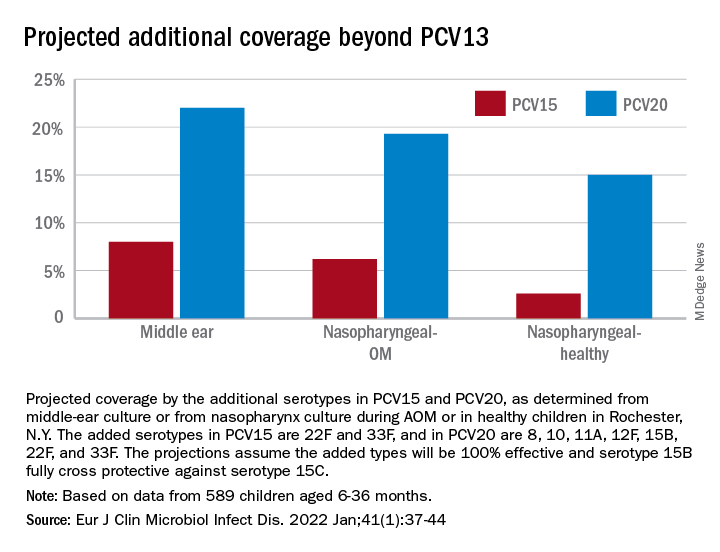

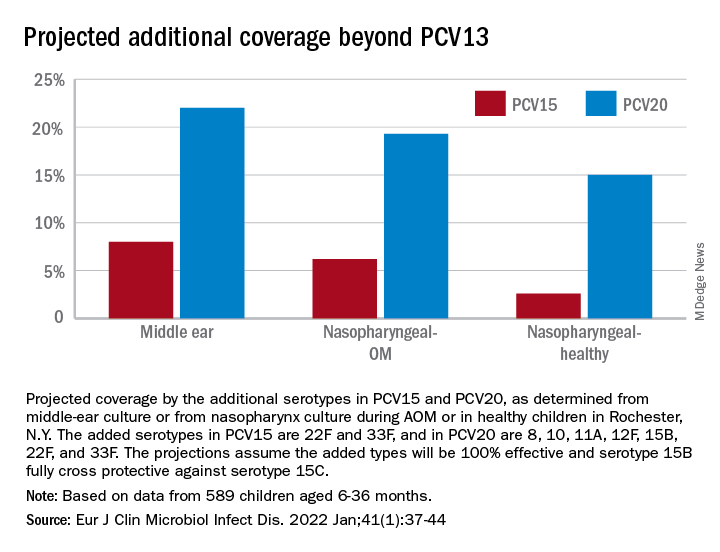

Based on our results, if PCV15 (PCV13 + 22F and 33F) effectiveness is identical to PCV13 for the included serotypes and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes is presumed, PCV15 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 8%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 6%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3%. As for the projected reductions brought about by PCV20 (PCV15 + 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B), presuming serotype 15B is efficacious against serotype 15C and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes, PCV20 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 22%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 20%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3% (Figure).

The CDC estimated that, in 2004, pneumococcal disease in the United States caused 4 million illness episodes, 22,000 deaths, 445,000 hospitalizations, 774,000 emergency department visits, 5 million outpatient visits, and 4.1 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. Direct medical costs totaled $3.5 billion. Pneumonia (866,000 cases) accounted for 22% of all cases and 72% of pneumococcal costs. AOM and sinusitis (1.5 million cases each) composed 75% of cases and 16% of direct medical costs.5 However, if indirect costs are taken into account, such as work loss by parents of young children, the cost of pneumococcal disease caused by AOM alone may exceed $6 billion annually6 and become dominant in the cost-effectiveness analysis in high-income countries.

Despite widespread use of PCV13, Pneumococcus has shown its resilience under vaccine pressure such that the organism remains a very common AOM pathogen. All-cause AOM has declined modestly and pneumococcal AOM caused by the specific serotypes in PCVs has declined dramatically since the introduction of PCVs. However, the burden of pneumococcal AOM disease is still considerable.

The notion that strains expressing serotypes that were not included in PCV7 were less virulent was proven wrong within a few years after introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of strains expressing serotype 19A, and others. The same cycle occurred after introduction of PCV13. It appears to take about 4 years after introduction of a PCV before peak effectiveness is achieved – which then begins to erode with emergence of NVTs. First, the NVTs are observed to colonize the nasopharynx as commensals and then from among those strains new disease-causing strains emerge.

At the most recent meeting of the International Society of Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases in Toronto in June, many presentations focused on the fact that PCVs elicit highly effective protective serotype-specific antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of included types. However, 100 serotypes are known. The limitations of PCVs are becoming increasingly apparent. They are costly and consume a large portion of the Vaccines for Children budget. Children in the developing world remain largely unvaccinated because of the high cost. NVTs that have emerged to cause disease vary by country, vary by adult vs. pediatric populations, and are dynamically changing year to year. Forthcoming PCVs of 15 and 20 serotypes will be even more costly than PCV13, will not include many newly emerged serotypes, and will probably likewise encounter “serotype replacement” because of high immune evasion by pneumococci.

When Merck and Pfizer made their decisions on serotype composition for PCV15 and PCV20, respectively, they were based on available data at the time regarding predominant serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in countries that had the best data and would be the market for their products. However, from the time of the decision to licensure of vaccine is many years, and during that time the pneumococcal serotypes have changed, more so for AOM, and I predict more change will occur in the future.

In the past 3 years, Dr. Pichichero has received honoraria from Merck to attend 1-day consulting meetings and his institution has received investigator-initiated research grants to study aspects of PCV15. In the past 3 years, he was reimbursed for expenses to attend the ISPPD meeting in Toronto to present a poster on potential efficacy of PCV20 to prevent complicated AOM.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3).

2. Kaur R et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44..

3. Pichichero M et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(8):561-8.

4. Zhou F et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):253-60.

5. Huang SS et al. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398-412.

6. Casey JR and Pichichero ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(9):865-73. .

My group in Rochester, N.Y., examined the current pneumococcal serotypes causing AOM in children. From our data, we can determine the PCV13 vaccine types that escape prevention and cause AOM and understand what effect to expect from the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) that will be coming soon. There are limited data from middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures on which to base such analyses. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for securing MEF for culture and our group is unique in providing such data to the Centers for Disease Control and publishing our results on a periodic basis to inform clinicians.

Pneumococci are the second most common cause of acute otitis media (AOM) since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) more than 2 decades ago.1,2 Pneumococcal AOM causes more severe acute disease and more often causes suppurative complications than Haemophilus influenzae, which is the most common cause of AOM. Prevention of pneumococcal AOM will be a highly relevant contributor to cost-effectiveness analyses for the anticipated introduction of PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer). Both PCV15 and PCV20 have been licensed for adult use; PCV15 licensure for infants and children occurred in June 2022 for invasive pneumococcal disease and is anticipated in the near future for PCV20. They are improvements over PCV13 because they add serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases, although less so for prevention of AOM, on the basis of our data.

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a necessary pathogenic step in progression to pneumococcal disease. However, not all strains of pneumococci expressing different capsular serotypes are equally virulent and likely to cause disease. In PCV-vaccinated populations, vaccine pressure and antibiotic resistance drive PCV serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs), gradually reducing the net effectiveness of the vaccines. Therefore, knowledge of prevalent NVTs colonizing the nasopharynx identifies future pneumococcal serotypes most likely to emerge as pathogenic.

We published an effectiveness study of PCV13.3 A relative reduction of 86% in AOM caused by strains expressing PCV13 serotypes was observed in the first few years after PCV13 introduction. The greatest reduction in MEF samples was in serotype 19A, with a relative reduction of 91%. However, over time the vaccine type efficacy of PCV13 against MEF-positive pneumococcal AOM has eroded. There was no clear efficacy against serotype 3, and we still observed cases of serotype 19A and 19F. PCV13 vaccine failures have been even more frequent in Europe (nearly 30% of pneumococcal AOM in Europe is caused by vaccine serotypes) than our data indicate, where about 10% of AOM is caused by PCV13 serotypes.

In our most recent publication covering 2015-2019, we described results from 589 children, aged 6-36 months, from whom we collected 2,042 nasopharyngeal samples.2,4 During AOM, 495 MEF samples from 319 AOM-infected children were collected (during bilateral infections, tympanocentesis was performed in both ears). Whether bacteria were isolated was based per AOM case, not per tap. The average age of children with AOM was 15 months (range 6-31 months). The three most prevalent nasopharyngeal pneumococcal serotypes were 35B, 23B, and 15B/C. Serotype 35B was the most common at AOM visits in both the nasopharynx and MEF samples followed by serotype 15B/C. Nonsusceptibility among pneumococci to penicillin, azithromycin, and multiple other antibiotics was high. Increasing resistance to ceftriaxone was also observed.

Based on our results, if PCV15 (PCV13 + 22F and 33F) effectiveness is identical to PCV13 for the included serotypes and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes is presumed, PCV15 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 8%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 6%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3%. As for the projected reductions brought about by PCV20 (PCV15 + 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B), presuming serotype 15B is efficacious against serotype 15C and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes, PCV20 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 22%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 20%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3% (Figure).

The CDC estimated that, in 2004, pneumococcal disease in the United States caused 4 million illness episodes, 22,000 deaths, 445,000 hospitalizations, 774,000 emergency department visits, 5 million outpatient visits, and 4.1 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. Direct medical costs totaled $3.5 billion. Pneumonia (866,000 cases) accounted for 22% of all cases and 72% of pneumococcal costs. AOM and sinusitis (1.5 million cases each) composed 75% of cases and 16% of direct medical costs.5 However, if indirect costs are taken into account, such as work loss by parents of young children, the cost of pneumococcal disease caused by AOM alone may exceed $6 billion annually6 and become dominant in the cost-effectiveness analysis in high-income countries.

Despite widespread use of PCV13, Pneumococcus has shown its resilience under vaccine pressure such that the organism remains a very common AOM pathogen. All-cause AOM has declined modestly and pneumococcal AOM caused by the specific serotypes in PCVs has declined dramatically since the introduction of PCVs. However, the burden of pneumococcal AOM disease is still considerable.

The notion that strains expressing serotypes that were not included in PCV7 were less virulent was proven wrong within a few years after introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of strains expressing serotype 19A, and others. The same cycle occurred after introduction of PCV13. It appears to take about 4 years after introduction of a PCV before peak effectiveness is achieved – which then begins to erode with emergence of NVTs. First, the NVTs are observed to colonize the nasopharynx as commensals and then from among those strains new disease-causing strains emerge.

At the most recent meeting of the International Society of Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases in Toronto in June, many presentations focused on the fact that PCVs elicit highly effective protective serotype-specific antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of included types. However, 100 serotypes are known. The limitations of PCVs are becoming increasingly apparent. They are costly and consume a large portion of the Vaccines for Children budget. Children in the developing world remain largely unvaccinated because of the high cost. NVTs that have emerged to cause disease vary by country, vary by adult vs. pediatric populations, and are dynamically changing year to year. Forthcoming PCVs of 15 and 20 serotypes will be even more costly than PCV13, will not include many newly emerged serotypes, and will probably likewise encounter “serotype replacement” because of high immune evasion by pneumococci.

When Merck and Pfizer made their decisions on serotype composition for PCV15 and PCV20, respectively, they were based on available data at the time regarding predominant serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in countries that had the best data and would be the market for their products. However, from the time of the decision to licensure of vaccine is many years, and during that time the pneumococcal serotypes have changed, more so for AOM, and I predict more change will occur in the future.

In the past 3 years, Dr. Pichichero has received honoraria from Merck to attend 1-day consulting meetings and his institution has received investigator-initiated research grants to study aspects of PCV15. In the past 3 years, he was reimbursed for expenses to attend the ISPPD meeting in Toronto to present a poster on potential efficacy of PCV20 to prevent complicated AOM.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3).

2. Kaur R et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44..

3. Pichichero M et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(8):561-8.

4. Zhou F et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):253-60.

5. Huang SS et al. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398-412.

6. Casey JR and Pichichero ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(9):865-73. .

My group in Rochester, N.Y., examined the current pneumococcal serotypes causing AOM in children. From our data, we can determine the PCV13 vaccine types that escape prevention and cause AOM and understand what effect to expect from the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) that will be coming soon. There are limited data from middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures on which to base such analyses. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for securing MEF for culture and our group is unique in providing such data to the Centers for Disease Control and publishing our results on a periodic basis to inform clinicians.

Pneumococci are the second most common cause of acute otitis media (AOM) since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) more than 2 decades ago.1,2 Pneumococcal AOM causes more severe acute disease and more often causes suppurative complications than Haemophilus influenzae, which is the most common cause of AOM. Prevention of pneumococcal AOM will be a highly relevant contributor to cost-effectiveness analyses for the anticipated introduction of PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer). Both PCV15 and PCV20 have been licensed for adult use; PCV15 licensure for infants and children occurred in June 2022 for invasive pneumococcal disease and is anticipated in the near future for PCV20. They are improvements over PCV13 because they add serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases, although less so for prevention of AOM, on the basis of our data.

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a necessary pathogenic step in progression to pneumococcal disease. However, not all strains of pneumococci expressing different capsular serotypes are equally virulent and likely to cause disease. In PCV-vaccinated populations, vaccine pressure and antibiotic resistance drive PCV serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs), gradually reducing the net effectiveness of the vaccines. Therefore, knowledge of prevalent NVTs colonizing the nasopharynx identifies future pneumococcal serotypes most likely to emerge as pathogenic.

We published an effectiveness study of PCV13.3 A relative reduction of 86% in AOM caused by strains expressing PCV13 serotypes was observed in the first few years after PCV13 introduction. The greatest reduction in MEF samples was in serotype 19A, with a relative reduction of 91%. However, over time the vaccine type efficacy of PCV13 against MEF-positive pneumococcal AOM has eroded. There was no clear efficacy against serotype 3, and we still observed cases of serotype 19A and 19F. PCV13 vaccine failures have been even more frequent in Europe (nearly 30% of pneumococcal AOM in Europe is caused by vaccine serotypes) than our data indicate, where about 10% of AOM is caused by PCV13 serotypes.

In our most recent publication covering 2015-2019, we described results from 589 children, aged 6-36 months, from whom we collected 2,042 nasopharyngeal samples.2,4 During AOM, 495 MEF samples from 319 AOM-infected children were collected (during bilateral infections, tympanocentesis was performed in both ears). Whether bacteria were isolated was based per AOM case, not per tap. The average age of children with AOM was 15 months (range 6-31 months). The three most prevalent nasopharyngeal pneumococcal serotypes were 35B, 23B, and 15B/C. Serotype 35B was the most common at AOM visits in both the nasopharynx and MEF samples followed by serotype 15B/C. Nonsusceptibility among pneumococci to penicillin, azithromycin, and multiple other antibiotics was high. Increasing resistance to ceftriaxone was also observed.

Based on our results, if PCV15 (PCV13 + 22F and 33F) effectiveness is identical to PCV13 for the included serotypes and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes is presumed, PCV15 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 8%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 6%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3%. As for the projected reductions brought about by PCV20 (PCV15 + 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B), presuming serotype 15B is efficacious against serotype 15C and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes, PCV20 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 22%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 20%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3% (Figure).

The CDC estimated that, in 2004, pneumococcal disease in the United States caused 4 million illness episodes, 22,000 deaths, 445,000 hospitalizations, 774,000 emergency department visits, 5 million outpatient visits, and 4.1 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. Direct medical costs totaled $3.5 billion. Pneumonia (866,000 cases) accounted for 22% of all cases and 72% of pneumococcal costs. AOM and sinusitis (1.5 million cases each) composed 75% of cases and 16% of direct medical costs.5 However, if indirect costs are taken into account, such as work loss by parents of young children, the cost of pneumococcal disease caused by AOM alone may exceed $6 billion annually6 and become dominant in the cost-effectiveness analysis in high-income countries.

Despite widespread use of PCV13, Pneumococcus has shown its resilience under vaccine pressure such that the organism remains a very common AOM pathogen. All-cause AOM has declined modestly and pneumococcal AOM caused by the specific serotypes in PCVs has declined dramatically since the introduction of PCVs. However, the burden of pneumococcal AOM disease is still considerable.

The notion that strains expressing serotypes that were not included in PCV7 were less virulent was proven wrong within a few years after introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of strains expressing serotype 19A, and others. The same cycle occurred after introduction of PCV13. It appears to take about 4 years after introduction of a PCV before peak effectiveness is achieved – which then begins to erode with emergence of NVTs. First, the NVTs are observed to colonize the nasopharynx as commensals and then from among those strains new disease-causing strains emerge.

At the most recent meeting of the International Society of Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases in Toronto in June, many presentations focused on the fact that PCVs elicit highly effective protective serotype-specific antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of included types. However, 100 serotypes are known. The limitations of PCVs are becoming increasingly apparent. They are costly and consume a large portion of the Vaccines for Children budget. Children in the developing world remain largely unvaccinated because of the high cost. NVTs that have emerged to cause disease vary by country, vary by adult vs. pediatric populations, and are dynamically changing year to year. Forthcoming PCVs of 15 and 20 serotypes will be even more costly than PCV13, will not include many newly emerged serotypes, and will probably likewise encounter “serotype replacement” because of high immune evasion by pneumococci.

When Merck and Pfizer made their decisions on serotype composition for PCV15 and PCV20, respectively, they were based on available data at the time regarding predominant serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in countries that had the best data and would be the market for their products. However, from the time of the decision to licensure of vaccine is many years, and during that time the pneumococcal serotypes have changed, more so for AOM, and I predict more change will occur in the future.

In the past 3 years, Dr. Pichichero has received honoraria from Merck to attend 1-day consulting meetings and his institution has received investigator-initiated research grants to study aspects of PCV15. In the past 3 years, he was reimbursed for expenses to attend the ISPPD meeting in Toronto to present a poster on potential efficacy of PCV20 to prevent complicated AOM.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3).

2. Kaur R et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44..

3. Pichichero M et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(8):561-8.

4. Zhou F et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):253-60.

5. Huang SS et al. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398-412.

6. Casey JR and Pichichero ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(9):865-73. .

Safety Profile of Mutant EGFR-TK Inhibitors in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-analysis

Lung cancer has been the leading cause of cancer-related mortality for decades. It is also predicted to remain as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality through 2030.1 Platinum-based chemotherapy, including carboplatin and paclitaxel, was introduced 3 decades ago and revolutionized the management of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A more recent advancement has been mutant epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) inhibitors.1 EGFR is a transmembrane protein that functions by transducing essential growth factor signaling from the extracellular milieu to the cell. As 60% of the advanced NSCLC expresses this receptor, blocking the mutant EGFR receptor was a groundbreaking development in the management of advanced NSCLC.2 Development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors has revolutionized the management of advanced NSCLC. This study was conducted to determine the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in the management of advanced NSCLC.

Methods

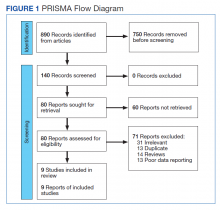

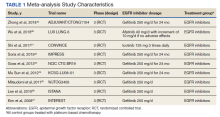

This meta-analysis was conducted according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The findings are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Two authors (MZ and MM) performed a systematic literature search using databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library using the medical search terms and their respective entry words with the following search strategy: safety, “mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors,” advanced, “non–small cell,” “lung cancer,” “adverse effect,” and literature. Additionally, unpublished trials were identified from clinicaltrials.gov, and references of all pertinent articles were also scrutinized to ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies. The search was completed on June 1, 2021, and we only included studies available in English. Two authors (MM and MZ) independently screened the search results in a 2-step process based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, 890 articles were evaluated for relevance on title and abstract level, followed by full-text screening of the final list of 140 articles. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or third-party review, and a total of 9 articles were included in the study.

The following eligibility criteria were used: original articles reporting adverse effects (AEs) of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. All the patients included in the study had an EGFR mutation but randomly assigned to either treatment or control group. All articles with subjective data on mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors AEs in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy were included in the analysis. Only 9 articles qualified the aforementioned selection criteria for eligibility. All qualifying studies were nationwide inpatient or pooled clinical trials data. The reasons for exclusion of the other 71 articles were irrelevant (n = 31), duplicate (n = 13), reviews (n = 14), and poor data reporting (n = 12). Out of the 9 included studies, 9 studies showed correlation of AEs, including rash, diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue. Seven studies showed correlation of AEs including neutropenia, anorexia, and vomiting. Six studies showed correlation of anemia, cough, and stomatitis. Five studies showed correlation of elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and leucopenia. Four studies showed correlation of fever between mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy.

The primary endpoints were reported AEs including rash, diarrhea, elevated ALT, elevated AST, stomatitis, nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever, respectively. Data on baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were then extracted, and summary tables were created. Summary estimates of the clinical endpoints were then calculated with risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was examined with the Cochran Q I2 statistic which can be defined as low (25% to 50%), moderate (50% to 75%), or high (> 75%). Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software CMA Version 3.0.

Results

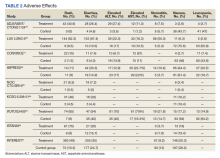

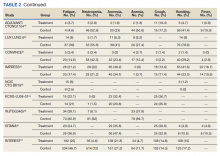

A total of 9 studies including 3415 patients (1775 in EGFR-TK inhibitor treatment group while 1640 patients in platinum-based chemotherapy control group) were included in the study. All 9 studies were phase III randomized control clinical trials conducted to compare the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC. Mean age was 61 years in both treatment and control groups. Further details on study and participant characteristics and safety profile including AEs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. No evidence of publication bias was found.

Rash developed in 45.8% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs only 5.6% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 7.38 with the 95% CI noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher rash event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 2).

Diarrhea occurred in 33.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 13.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 2.63 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher diarrheal rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 3).

Elevated ALT levels developed in 27.9% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 15.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher ALT levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 4).

Elevated AST levels occurred in 40.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 12.8% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.77 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming elevated AST levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 5).

Stomatitis developed in 17.2% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 7.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.53 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher stomatitis event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 6).

Nausea occurred in 16.5% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 42.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher nausea rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 7).

Leucopenia developed in 9.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 51.3% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.18 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher leucopenia incidence in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 8).

Fatigue was reported in 17% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 29.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.59 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fatigue rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 9).

Neutropenia developed in 6.1% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 48.2% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.11 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher neutropenia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 10).

Anorexia developed in 21.3% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 31.4% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.44 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 11).

Anemia occurred in 8.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 32.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.24 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 12).

Cough was reported in 17.8% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 18.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.99 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming slightly higher cough rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 13).

Vomiting developed in 11% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.35 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher vomiting rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 14).

Fever occurred in 5.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.41 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fever rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 15).

Discussion

Despite the advancement in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC, lung cancer stays as most common cause of cancer-related death in North America and European countries, as patients usually have an advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.3 In the past, platinum-based chemotherapy remained the standard of care for most of the patients affected with advanced NSCLC, but the higher recurrence rate and increase in frequency and intensity of AEs with platinum-based chemotherapy led to the development of targeted therapy for NSCLC, one of which includes

Smoking is the most common reversible risk factor associated with lung cancer. The EURTAC trial was the first perspective study in this regard, which compared safety and efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. Results analyzed in this study were in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors except in the group of former smokers.5 On the contrary, the OPTIMAL trial showed results in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors both in active and former smokers; this trial also confirmed the efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in European and Asian populations, confirming the rationale for routine testing of EGFR mutation in all the patients being diagnosed with advanced NSCLC.6 Similarly, osimertinib is one of the most recent mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in patients with EGFR-positive receptors.

According to the FLAURA trial, patients receiving osimertinib showed significantly longer progression-free survival compared with platinum-based chemotherapy and early mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors. Median progression-free survival was noted to be 18.9 months, which showed 54% lower risk of disease progression in the treatment group receiving osimertinib.7 The ARCHER study emphasized a significant improvement in overall survival as well as progression-free survival among a patient population receiving dacomitinib compared with platinum-based chemotherapy.8,9

Being a potent targeted therapy, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors do come with some AEs including diarrhea, which was seen in 33.6% of the patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study vs 53% in the chemotherapy group, as was observed in the study conducted by Pless and colleagues.10 Similarly, only 16.5% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed nausea compared with 66% being observed in patients receiving chemotherapy. Correspondingly, only a small fraction of patients (9.7%) receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed leucopenia, which was 10 times less reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with patients receiving chemotherapy having a percentage of 100%. A similar trend was reported for neutropenia and anemia in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with an incidence of 6.1% and 8.7%, compared with the platinum-based chemotherapy group in which the incidence was found to be 80% and 100%, respectively. It was concluded that platinum-based chemotherapy had played a vital role in the treatment of advanced NSCLC but at an expense of serious and severe AEs which led to discontinuation or withdrawal of treatment, leading to relapse and recurrence of lung cancer.10,11

Zhong and colleagues conducted a phase 2 randomized clinical trial comparing mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. They concluded that in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy, incidence of rash, vomiting, anorexia, neutropenia, and nausea were 29.4%, 47%, 41.2%, 55.8%, and 32.4% compared with 45.8%, 11%, 21.3%, 6.1%, and 16.5%, respectively, reported in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC.12

Another study was conducted in 2019 by Noronha and colleagues to determine the impact of platinum-based chemotherapy combined with gefitinib on patients with advanced NSCLC.13 They concluded that 70% of the patients receiving combination treatment developed rash, which was significantly higher compared with 45.8% patients receiving the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors alone in our study. Also, 56% of patients receiving combination therapy developed diarrhea vs 33.6% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors only. Similarly, 96% of patients in the combination therapy group developed some degree of anemia compared with only 8.7% patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. In the same way, neutropenia was observed in 55% of patients receiving combination therapy vs 6.1% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors solely. They concluded that mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy increase the incidence of AEs of chemotherapy by many folds.13,14

Kato and colleagues conducted a study to determine the impact on AEs when erlotinib was combined with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors like bevacizumab, they stated that 98.7% of patient in combination therapy developed rash, the incidence of which was only 45.8% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was observed in our study. Similar trends were noticed with other AEs, including diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and elevated liver enzymes.15

With the latest advancements in the management of advanced NSCLC, nivolumab, a programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor, was developed and either used as monotherapy in patients with PD-L1 expression or was combined with platinum-based chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 expression.16,17 Patients expressing lower PD-L1 levels were not omitted from receiving nivolumab as no significant difference was noted in progression-free span and overall survival in patients receiving nivolumab irrespective of PD-L1 levels.15 Rash developed in 17% of patients after receiving nivolumab vs 45.8% patients being observed in our study. A similar trend was observed with diarrhea as only 17% of the population receiving nivolumab developed diarrhea compared with 33.6% of the population receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Likewise, only 9.9% of the patients receiving nivolumab developed nausea as an AE compared with 16.5% being observed in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Also, fatigue was observed in 14.4% of the population receiving nivolumab vs 17% observed in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was noticed in our study.7,8

Rizvi and colleagues conducted a study on the role of nivolumab when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC and reported that 40% of patients included in the study developed rash compared with 45.8% reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Similarly, only 13% of patients in the nivolumab group developed diarrhea vs 33.6% cases reported in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. Also, 7% of patients in the nivolumab group developed elevated ALT levels vs 27.9% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors included in our study, concluding that addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors like nivolumab to platinum-based chemotherapy does not increase the frequency of AEs.18

Conclusions

Our study focused on the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs platinum-based chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors are safer than platinum-based chemotherapy when compared for nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever. On the other end, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors cause slightly higher AEs, including rash, diarrhea, elevated AST and ALT levels, and stomatitis. However, considering that the development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors laid a foundation of targeted therapy, we recommend continuing using mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC especially in patients having mutant EGFR receptors. AEs caused by mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors are significant but are usually tolerable and can be avoided by reducing the dosage of it with each cycle or by skipping or delaying the dose until the patient is symptomatic.

1. Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913-2921. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155

2. da Cunha Santos G, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS. EGFR mutations and lung cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:49-69. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130206

3. Sgambato A, Casaluce F, Maione P, et al. The role of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the first-line treatment of advanced non small cell lung cancer patients harboring EGFR mutation. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(20):3337-3352. doi:10.2174/092986712801215973

4. Rossi A, Di Maio M. Platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: optimal number of treatment cycles. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(6):653-660. doi:10.1586/14737140.2016.1170596

5. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non–small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239-246. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X

6. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non–small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):735-742. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X

7. Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113-125. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1713137

8. Mok TS, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Improvement in overall survival in a randomized study that compared dacomitinib with gefitinib in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer and EGFR-activating mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2244-2250. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.7994

9. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947-957. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810699

10. Pless M, Stupp R, Ris HB, et al. Induction chemoradiation in stage IIIA/N2 non–small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9998):1049-1056. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60294-X

11. Albain KS, Rusch VW, Crowley JJ, et al. Concurrent cisplatin/etoposide plus chest radiotherapy followed by surgery for stages IIIA (N2) and IIIB non–small-cell lung cancer: mature results of Southwest Oncology Group phase II study 8805. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(8):1880-1892. doi:10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1880

12. Zhong WZ, Chen KN, Chen C, et al. Erlotinib versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant treatment of Stage IIIA-N2 EGFR-mutant non–small-cell lung cancer (EMERGING-CTONG 1103): a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(25):2235-2245. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00075

13. Noronha V, Patil VM, Joshi A, et al. Gefitinib versus gefitinib plus pemetrexed and carboplatin chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(2):124-136. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01154

14. Noronha V, Prabhash K, Thavamani A, et al. EGFR mutations in Indian lung cancer patients: clinical correlation and outcome to EGFR targeted therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61561. Published 2013 Apr 19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061561

15. Kato T, Seto T, Nishio M, et al. Erlotinib plus bevacizumab phase ll study in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (JO25567): updated safety results. Drug Saf. 2018;41(2):229-237. doi:10.1007/s40264-017-0596-0

16. Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020-2031. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910231

17. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093-2104. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801946

18. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Brahmer JR, et al. Nivolumab in combination with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(25):2969-2979. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9861

19. Zhong WZ, Wang Q, Mao WM, et al. Gefitinib versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin as adjuvant treatment for stage II-IIIA (N1-N2) EGFR-mutant NSCLC: final overall survival analysis of CTONG1104 Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):713-722. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.01820

20. Yang JC, Sequist LV, Geater SL, et al. Clinical activity of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring uncommon EGFR mutations: a combined post-hoc analysis of LUX-Lung 2, LUX-Lung 3, and LUX-Lung 6. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):830-838. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00026-1

21. Shi YK, Wang L, Han BH, et al. First-line icotinib versus cisplatin/pemetrexed plus pemetrexed maintenance therapy for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (CONVINCE): a phase 3, open-label, randomized study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2443-2450. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx359

22. Soria JC, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, et al. Gefitinib plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on first-line gefitinib (IMPRESS): a phase 3 randomized trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):990-998 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00121-7

23. Goss GD, O’Callaghan C, Lorimer I, et al. Gefitinib versus placebo in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the NCIC CTG BR19 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3320-3326. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1816

24. Sun JM, Lee KH, Kim SW, et al. Gefitinib versus pemetrexed as second-line treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (KCSG-LU08-01): an open-label, phase 3 trial. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6234-6242. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1816

25. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121-128. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X

26. Lee DH, Park K, Kim JH, Lee JS, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gefitinib versus docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer patients who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(4):1307-1314. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1903

27. Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomized phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;22;372(9652):1809-1818. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4

Lung cancer has been the leading cause of cancer-related mortality for decades. It is also predicted to remain as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality through 2030.1 Platinum-based chemotherapy, including carboplatin and paclitaxel, was introduced 3 decades ago and revolutionized the management of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A more recent advancement has been mutant epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) inhibitors.1 EGFR is a transmembrane protein that functions by transducing essential growth factor signaling from the extracellular milieu to the cell. As 60% of the advanced NSCLC expresses this receptor, blocking the mutant EGFR receptor was a groundbreaking development in the management of advanced NSCLC.2 Development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors has revolutionized the management of advanced NSCLC. This study was conducted to determine the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in the management of advanced NSCLC.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The findings are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Two authors (MZ and MM) performed a systematic literature search using databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library using the medical search terms and their respective entry words with the following search strategy: safety, “mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors,” advanced, “non–small cell,” “lung cancer,” “adverse effect,” and literature. Additionally, unpublished trials were identified from clinicaltrials.gov, and references of all pertinent articles were also scrutinized to ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies. The search was completed on June 1, 2021, and we only included studies available in English. Two authors (MM and MZ) independently screened the search results in a 2-step process based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, 890 articles were evaluated for relevance on title and abstract level, followed by full-text screening of the final list of 140 articles. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or third-party review, and a total of 9 articles were included in the study.

The following eligibility criteria were used: original articles reporting adverse effects (AEs) of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. All the patients included in the study had an EGFR mutation but randomly assigned to either treatment or control group. All articles with subjective data on mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors AEs in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy were included in the analysis. Only 9 articles qualified the aforementioned selection criteria for eligibility. All qualifying studies were nationwide inpatient or pooled clinical trials data. The reasons for exclusion of the other 71 articles were irrelevant (n = 31), duplicate (n = 13), reviews (n = 14), and poor data reporting (n = 12). Out of the 9 included studies, 9 studies showed correlation of AEs, including rash, diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue. Seven studies showed correlation of AEs including neutropenia, anorexia, and vomiting. Six studies showed correlation of anemia, cough, and stomatitis. Five studies showed correlation of elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and leucopenia. Four studies showed correlation of fever between mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy.

The primary endpoints were reported AEs including rash, diarrhea, elevated ALT, elevated AST, stomatitis, nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever, respectively. Data on baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were then extracted, and summary tables were created. Summary estimates of the clinical endpoints were then calculated with risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was examined with the Cochran Q I2 statistic which can be defined as low (25% to 50%), moderate (50% to 75%), or high (> 75%). Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software CMA Version 3.0.

Results

A total of 9 studies including 3415 patients (1775 in EGFR-TK inhibitor treatment group while 1640 patients in platinum-based chemotherapy control group) were included in the study. All 9 studies were phase III randomized control clinical trials conducted to compare the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC. Mean age was 61 years in both treatment and control groups. Further details on study and participant characteristics and safety profile including AEs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. No evidence of publication bias was found.

Rash developed in 45.8% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs only 5.6% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 7.38 with the 95% CI noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher rash event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 2).

Diarrhea occurred in 33.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 13.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 2.63 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher diarrheal rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 3).

Elevated ALT levels developed in 27.9% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 15.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher ALT levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 4).

Elevated AST levels occurred in 40.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 12.8% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.77 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming elevated AST levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 5).

Stomatitis developed in 17.2% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 7.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.53 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher stomatitis event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 6).

Nausea occurred in 16.5% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 42.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher nausea rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 7).

Leucopenia developed in 9.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 51.3% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.18 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher leucopenia incidence in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 8).

Fatigue was reported in 17% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 29.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.59 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fatigue rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 9).

Neutropenia developed in 6.1% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 48.2% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.11 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher neutropenia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 10).

Anorexia developed in 21.3% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 31.4% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.44 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 11).

Anemia occurred in 8.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 32.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.24 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 12).

Cough was reported in 17.8% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 18.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.99 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming slightly higher cough rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 13).

Vomiting developed in 11% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.35 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher vomiting rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 14).

Fever occurred in 5.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.41 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fever rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 15).

Discussion

Despite the advancement in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC, lung cancer stays as most common cause of cancer-related death in North America and European countries, as patients usually have an advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.3 In the past, platinum-based chemotherapy remained the standard of care for most of the patients affected with advanced NSCLC, but the higher recurrence rate and increase in frequency and intensity of AEs with platinum-based chemotherapy led to the development of targeted therapy for NSCLC, one of which includes

Smoking is the most common reversible risk factor associated with lung cancer. The EURTAC trial was the first perspective study in this regard, which compared safety and efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. Results analyzed in this study were in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors except in the group of former smokers.5 On the contrary, the OPTIMAL trial showed results in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors both in active and former smokers; this trial also confirmed the efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in European and Asian populations, confirming the rationale for routine testing of EGFR mutation in all the patients being diagnosed with advanced NSCLC.6 Similarly, osimertinib is one of the most recent mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in patients with EGFR-positive receptors.

According to the FLAURA trial, patients receiving osimertinib showed significantly longer progression-free survival compared with platinum-based chemotherapy and early mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors. Median progression-free survival was noted to be 18.9 months, which showed 54% lower risk of disease progression in the treatment group receiving osimertinib.7 The ARCHER study emphasized a significant improvement in overall survival as well as progression-free survival among a patient population receiving dacomitinib compared with platinum-based chemotherapy.8,9

Being a potent targeted therapy, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors do come with some AEs including diarrhea, which was seen in 33.6% of the patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study vs 53% in the chemotherapy group, as was observed in the study conducted by Pless and colleagues.10 Similarly, only 16.5% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed nausea compared with 66% being observed in patients receiving chemotherapy. Correspondingly, only a small fraction of patients (9.7%) receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed leucopenia, which was 10 times less reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with patients receiving chemotherapy having a percentage of 100%. A similar trend was reported for neutropenia and anemia in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with an incidence of 6.1% and 8.7%, compared with the platinum-based chemotherapy group in which the incidence was found to be 80% and 100%, respectively. It was concluded that platinum-based chemotherapy had played a vital role in the treatment of advanced NSCLC but at an expense of serious and severe AEs which led to discontinuation or withdrawal of treatment, leading to relapse and recurrence of lung cancer.10,11

Zhong and colleagues conducted a phase 2 randomized clinical trial comparing mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. They concluded that in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy, incidence of rash, vomiting, anorexia, neutropenia, and nausea were 29.4%, 47%, 41.2%, 55.8%, and 32.4% compared with 45.8%, 11%, 21.3%, 6.1%, and 16.5%, respectively, reported in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC.12

Another study was conducted in 2019 by Noronha and colleagues to determine the impact of platinum-based chemotherapy combined with gefitinib on patients with advanced NSCLC.13 They concluded that 70% of the patients receiving combination treatment developed rash, which was significantly higher compared with 45.8% patients receiving the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors alone in our study. Also, 56% of patients receiving combination therapy developed diarrhea vs 33.6% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors only. Similarly, 96% of patients in the combination therapy group developed some degree of anemia compared with only 8.7% patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. In the same way, neutropenia was observed in 55% of patients receiving combination therapy vs 6.1% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors solely. They concluded that mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy increase the incidence of AEs of chemotherapy by many folds.13,14

Kato and colleagues conducted a study to determine the impact on AEs when erlotinib was combined with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors like bevacizumab, they stated that 98.7% of patient in combination therapy developed rash, the incidence of which was only 45.8% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was observed in our study. Similar trends were noticed with other AEs, including diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and elevated liver enzymes.15

With the latest advancements in the management of advanced NSCLC, nivolumab, a programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor, was developed and either used as monotherapy in patients with PD-L1 expression or was combined with platinum-based chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 expression.16,17 Patients expressing lower PD-L1 levels were not omitted from receiving nivolumab as no significant difference was noted in progression-free span and overall survival in patients receiving nivolumab irrespective of PD-L1 levels.15 Rash developed in 17% of patients after receiving nivolumab vs 45.8% patients being observed in our study. A similar trend was observed with diarrhea as only 17% of the population receiving nivolumab developed diarrhea compared with 33.6% of the population receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Likewise, only 9.9% of the patients receiving nivolumab developed nausea as an AE compared with 16.5% being observed in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Also, fatigue was observed in 14.4% of the population receiving nivolumab vs 17% observed in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was noticed in our study.7,8

Rizvi and colleagues conducted a study on the role of nivolumab when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC and reported that 40% of patients included in the study developed rash compared with 45.8% reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Similarly, only 13% of patients in the nivolumab group developed diarrhea vs 33.6% cases reported in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. Also, 7% of patients in the nivolumab group developed elevated ALT levels vs 27.9% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors included in our study, concluding that addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors like nivolumab to platinum-based chemotherapy does not increase the frequency of AEs.18

Conclusions

Our study focused on the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs platinum-based chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors are safer than platinum-based chemotherapy when compared for nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever. On the other end, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors cause slightly higher AEs, including rash, diarrhea, elevated AST and ALT levels, and stomatitis. However, considering that the development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors laid a foundation of targeted therapy, we recommend continuing using mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC especially in patients having mutant EGFR receptors. AEs caused by mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors are significant but are usually tolerable and can be avoided by reducing the dosage of it with each cycle or by skipping or delaying the dose until the patient is symptomatic.

Lung cancer has been the leading cause of cancer-related mortality for decades. It is also predicted to remain as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality through 2030.1 Platinum-based chemotherapy, including carboplatin and paclitaxel, was introduced 3 decades ago and revolutionized the management of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A more recent advancement has been mutant epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) inhibitors.1 EGFR is a transmembrane protein that functions by transducing essential growth factor signaling from the extracellular milieu to the cell. As 60% of the advanced NSCLC expresses this receptor, blocking the mutant EGFR receptor was a groundbreaking development in the management of advanced NSCLC.2 Development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors has revolutionized the management of advanced NSCLC. This study was conducted to determine the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in the management of advanced NSCLC.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The findings are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Two authors (MZ and MM) performed a systematic literature search using databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library using the medical search terms and their respective entry words with the following search strategy: safety, “mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors,” advanced, “non–small cell,” “lung cancer,” “adverse effect,” and literature. Additionally, unpublished trials were identified from clinicaltrials.gov, and references of all pertinent articles were also scrutinized to ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies. The search was completed on June 1, 2021, and we only included studies available in English. Two authors (MM and MZ) independently screened the search results in a 2-step process based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, 890 articles were evaluated for relevance on title and abstract level, followed by full-text screening of the final list of 140 articles. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or third-party review, and a total of 9 articles were included in the study.

The following eligibility criteria were used: original articles reporting adverse effects (AEs) of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. All the patients included in the study had an EGFR mutation but randomly assigned to either treatment or control group. All articles with subjective data on mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors AEs in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy were included in the analysis. Only 9 articles qualified the aforementioned selection criteria for eligibility. All qualifying studies were nationwide inpatient or pooled clinical trials data. The reasons for exclusion of the other 71 articles were irrelevant (n = 31), duplicate (n = 13), reviews (n = 14), and poor data reporting (n = 12). Out of the 9 included studies, 9 studies showed correlation of AEs, including rash, diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue. Seven studies showed correlation of AEs including neutropenia, anorexia, and vomiting. Six studies showed correlation of anemia, cough, and stomatitis. Five studies showed correlation of elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and leucopenia. Four studies showed correlation of fever between mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy.

The primary endpoints were reported AEs including rash, diarrhea, elevated ALT, elevated AST, stomatitis, nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever, respectively. Data on baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were then extracted, and summary tables were created. Summary estimates of the clinical endpoints were then calculated with risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was examined with the Cochran Q I2 statistic which can be defined as low (25% to 50%), moderate (50% to 75%), or high (> 75%). Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software CMA Version 3.0.

Results

A total of 9 studies including 3415 patients (1775 in EGFR-TK inhibitor treatment group while 1640 patients in platinum-based chemotherapy control group) were included in the study. All 9 studies were phase III randomized control clinical trials conducted to compare the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC. Mean age was 61 years in both treatment and control groups. Further details on study and participant characteristics and safety profile including AEs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. No evidence of publication bias was found.

Rash developed in 45.8% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs only 5.6% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 7.38 with the 95% CI noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher rash event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 2).

Diarrhea occurred in 33.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 13.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 2.63 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher diarrheal rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 3).

Elevated ALT levels developed in 27.9% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 15.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher ALT levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 4).

Elevated AST levels occurred in 40.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 12.8% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.77 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming elevated AST levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 5).

Stomatitis developed in 17.2% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 7.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.53 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher stomatitis event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 6).

Nausea occurred in 16.5% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 42.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher nausea rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 7).

Leucopenia developed in 9.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 51.3% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.18 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher leucopenia incidence in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 8).

Fatigue was reported in 17% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 29.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.59 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fatigue rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 9).

Neutropenia developed in 6.1% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 48.2% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.11 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher neutropenia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 10).

Anorexia developed in 21.3% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 31.4% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.44 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 11).

Anemia occurred in 8.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 32.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.24 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 12).

Cough was reported in 17.8% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 18.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.99 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming slightly higher cough rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 13).

Vomiting developed in 11% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.35 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher vomiting rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 14).