User login

Multiple Sclerosis: Treatment & Management

Does vitamin D benefit only those who are deficient?

, suggests a new large-scale analysis.

Data on more than 380,000 participants gathered from 35 studies showed that, overall, there is no significant relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations, a clinical indicator of vitamin D status, and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or all-cause death, in a Mendelian randomization analysis.

However, Stephen Burgess, PhD, and colleagues showed that, in vitamin D–deficient individuals, each 10 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentrations reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 31%.

The research, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, also suggests there was a nonsignificant link between 25(OH)D concentrations and stroke and CHD, but again, only in vitamin D deficient individuals.

In an accompanying editorial, Guillaume Butler-Laporte, MD, and J. Brent Richards, MD, praise the researchers on their study methodology.

They add that the results “could have important public health and clinical consequences” and will “allow clinicians to better weigh the potential benefits of supplementation against its risk,” such as financial cost, “for better patient care – particularly among those with frank vitamin D deficiency.”

They continue: “Given that vitamin D deficiency is relatively common and vitamin D supplementation is safe, the rationale exists to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation in those with deficiency in large-scale randomized controlled trials.”

However, Dr. Butler-Laporte and Dr. Richards, of the Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, also note the study has several limitations, including the fact that the lifetime exposure to lower vitamin D levels captured by Mendelian randomization may result in larger effect sizes than in conventional trials.

Prior RCTS underpowered to detect effects of vitamin D supplements

“There are several potential mechanisms by which vitamin D could be protective for cardiovascular mortality, including mechanisms linking low vitamin D status with hyperparathyroidism and low serum calcium and phosphate,” write Dr. Burgess of the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge (England), and coauthors.

They also highlight that vitamin D is “further implicated in endothelial cell function” and affects the transcription of genes linked to cell division and apoptosis, providing “potential mechanisms implicating vitamin D for cancer.”

The researchers note that, while epidemiologic studies have “consistently” found a link between 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and other chronic diseases, several large trials of vitamin D supplementation have reported “null results.”

They argue, however, that many of these trials have recruited individuals “irrespective of baseline 25(OH)D concentration” and have been underpowered to detect the effects of supplementation.

To overcome these limitations, the team gathered data from the UK Biobank, the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cardiovascular Disease (EPIC-CVD) study, 31 studies from the Vitamin D Studies Collaboration (VitDSC), and two Copenhagen population-based studies.

They first performed an observational study that included 384,721 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who had a valid 25(OH)D measurement and no previously known cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Researchers also included 67,992 participants from the VitDSC studies who did not have previously known cardiovascular disease. They analyzed 25(OH)D concentrations, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and major incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality using individual participant data.

The results showed that, at low 25(OH)D concentrations, there was an inverse association between 25(OH)D and incident CHD, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Next, the team conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis on 333,002 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who were of European ancestry and had both a valid 25(OH)D measurement and genetic data that passed quality-control steps.

Information on 31,362 participants in the Copenhagen population-based studies was also included, giving a total of 386,406 individuals, of whom 33,546 had CHD, 18,166 had a stroke, and 27,885 died.

The mean age of participants ranged from 54.8 to 57.5 years, and between 53.4% and 55.4% were female.

Up to 7% of study participants were vitamin D deficient

The 25(OH)D analysis indicated that 3.9% of UK Biobank and 3.7% of Copenhagen study participants were deficient, compared with 6.9% in EPIC-CVD.

Across the full range of 25(OH)D concentrations, there was no significant association between genetically predicted 25(OH)D levels and CHD, stroke, or all-cause mortality.

However, restricting the analysis to individuals deemed vitamin D deficient (25[OH]D concentration < 25 nmol/L) revealed there was “strong evidence” for an inverse association with all-cause mortality, at an odds ratio per 10 nmol/L increase in genetically predicted 25(OH)D concentration of 0.69 (P < .0001), the team notes.

There were also nonsignificant associations between being in the deficient stratum and CHD, at an odds ratio of 0.89 (P = .14), and stroke, at an odds ratio of 0.85 (P = .09).

Further analysis suggests the association between 25(OH)D concentrations and all-cause mortality has a “clear threshold shape,” the researchers say, with evidence of an inverse association at concentrations below 40 nmol/L and null associations above that threshold.

They acknowledge, however, that their study has several potential limitations, including the assumption in their Mendelian randomization that the “only causal pathway from the genetic variants to the outcome is via 25(OH)D concentrations.”

Moreover, the genetic variants may affect 25(OH)D concentrations in a different way from “dietary supplementation or other clinical interventions.”

They also concede that their study was limited to middle-aged participants of European ancestries, which means the findings “might not be applicable to other populations.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Health Data Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and International Agency for Research on Cancer. Dr. Burgess has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggests a new large-scale analysis.

Data on more than 380,000 participants gathered from 35 studies showed that, overall, there is no significant relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations, a clinical indicator of vitamin D status, and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or all-cause death, in a Mendelian randomization analysis.

However, Stephen Burgess, PhD, and colleagues showed that, in vitamin D–deficient individuals, each 10 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentrations reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 31%.

The research, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, also suggests there was a nonsignificant link between 25(OH)D concentrations and stroke and CHD, but again, only in vitamin D deficient individuals.

In an accompanying editorial, Guillaume Butler-Laporte, MD, and J. Brent Richards, MD, praise the researchers on their study methodology.

They add that the results “could have important public health and clinical consequences” and will “allow clinicians to better weigh the potential benefits of supplementation against its risk,” such as financial cost, “for better patient care – particularly among those with frank vitamin D deficiency.”

They continue: “Given that vitamin D deficiency is relatively common and vitamin D supplementation is safe, the rationale exists to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation in those with deficiency in large-scale randomized controlled trials.”

However, Dr. Butler-Laporte and Dr. Richards, of the Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, also note the study has several limitations, including the fact that the lifetime exposure to lower vitamin D levels captured by Mendelian randomization may result in larger effect sizes than in conventional trials.

Prior RCTS underpowered to detect effects of vitamin D supplements

“There are several potential mechanisms by which vitamin D could be protective for cardiovascular mortality, including mechanisms linking low vitamin D status with hyperparathyroidism and low serum calcium and phosphate,” write Dr. Burgess of the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge (England), and coauthors.

They also highlight that vitamin D is “further implicated in endothelial cell function” and affects the transcription of genes linked to cell division and apoptosis, providing “potential mechanisms implicating vitamin D for cancer.”

The researchers note that, while epidemiologic studies have “consistently” found a link between 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and other chronic diseases, several large trials of vitamin D supplementation have reported “null results.”

They argue, however, that many of these trials have recruited individuals “irrespective of baseline 25(OH)D concentration” and have been underpowered to detect the effects of supplementation.

To overcome these limitations, the team gathered data from the UK Biobank, the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cardiovascular Disease (EPIC-CVD) study, 31 studies from the Vitamin D Studies Collaboration (VitDSC), and two Copenhagen population-based studies.

They first performed an observational study that included 384,721 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who had a valid 25(OH)D measurement and no previously known cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Researchers also included 67,992 participants from the VitDSC studies who did not have previously known cardiovascular disease. They analyzed 25(OH)D concentrations, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and major incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality using individual participant data.

The results showed that, at low 25(OH)D concentrations, there was an inverse association between 25(OH)D and incident CHD, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Next, the team conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis on 333,002 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who were of European ancestry and had both a valid 25(OH)D measurement and genetic data that passed quality-control steps.

Information on 31,362 participants in the Copenhagen population-based studies was also included, giving a total of 386,406 individuals, of whom 33,546 had CHD, 18,166 had a stroke, and 27,885 died.

The mean age of participants ranged from 54.8 to 57.5 years, and between 53.4% and 55.4% were female.

Up to 7% of study participants were vitamin D deficient

The 25(OH)D analysis indicated that 3.9% of UK Biobank and 3.7% of Copenhagen study participants were deficient, compared with 6.9% in EPIC-CVD.

Across the full range of 25(OH)D concentrations, there was no significant association between genetically predicted 25(OH)D levels and CHD, stroke, or all-cause mortality.

However, restricting the analysis to individuals deemed vitamin D deficient (25[OH]D concentration < 25 nmol/L) revealed there was “strong evidence” for an inverse association with all-cause mortality, at an odds ratio per 10 nmol/L increase in genetically predicted 25(OH)D concentration of 0.69 (P < .0001), the team notes.

There were also nonsignificant associations between being in the deficient stratum and CHD, at an odds ratio of 0.89 (P = .14), and stroke, at an odds ratio of 0.85 (P = .09).

Further analysis suggests the association between 25(OH)D concentrations and all-cause mortality has a “clear threshold shape,” the researchers say, with evidence of an inverse association at concentrations below 40 nmol/L and null associations above that threshold.

They acknowledge, however, that their study has several potential limitations, including the assumption in their Mendelian randomization that the “only causal pathway from the genetic variants to the outcome is via 25(OH)D concentrations.”

Moreover, the genetic variants may affect 25(OH)D concentrations in a different way from “dietary supplementation or other clinical interventions.”

They also concede that their study was limited to middle-aged participants of European ancestries, which means the findings “might not be applicable to other populations.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Health Data Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and International Agency for Research on Cancer. Dr. Burgess has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggests a new large-scale analysis.

Data on more than 380,000 participants gathered from 35 studies showed that, overall, there is no significant relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations, a clinical indicator of vitamin D status, and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or all-cause death, in a Mendelian randomization analysis.

However, Stephen Burgess, PhD, and colleagues showed that, in vitamin D–deficient individuals, each 10 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentrations reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 31%.

The research, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, also suggests there was a nonsignificant link between 25(OH)D concentrations and stroke and CHD, but again, only in vitamin D deficient individuals.

In an accompanying editorial, Guillaume Butler-Laporte, MD, and J. Brent Richards, MD, praise the researchers on their study methodology.

They add that the results “could have important public health and clinical consequences” and will “allow clinicians to better weigh the potential benefits of supplementation against its risk,” such as financial cost, “for better patient care – particularly among those with frank vitamin D deficiency.”

They continue: “Given that vitamin D deficiency is relatively common and vitamin D supplementation is safe, the rationale exists to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation in those with deficiency in large-scale randomized controlled trials.”

However, Dr. Butler-Laporte and Dr. Richards, of the Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, also note the study has several limitations, including the fact that the lifetime exposure to lower vitamin D levels captured by Mendelian randomization may result in larger effect sizes than in conventional trials.

Prior RCTS underpowered to detect effects of vitamin D supplements

“There are several potential mechanisms by which vitamin D could be protective for cardiovascular mortality, including mechanisms linking low vitamin D status with hyperparathyroidism and low serum calcium and phosphate,” write Dr. Burgess of the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge (England), and coauthors.

They also highlight that vitamin D is “further implicated in endothelial cell function” and affects the transcription of genes linked to cell division and apoptosis, providing “potential mechanisms implicating vitamin D for cancer.”

The researchers note that, while epidemiologic studies have “consistently” found a link between 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and other chronic diseases, several large trials of vitamin D supplementation have reported “null results.”

They argue, however, that many of these trials have recruited individuals “irrespective of baseline 25(OH)D concentration” and have been underpowered to detect the effects of supplementation.

To overcome these limitations, the team gathered data from the UK Biobank, the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cardiovascular Disease (EPIC-CVD) study, 31 studies from the Vitamin D Studies Collaboration (VitDSC), and two Copenhagen population-based studies.

They first performed an observational study that included 384,721 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who had a valid 25(OH)D measurement and no previously known cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Researchers also included 67,992 participants from the VitDSC studies who did not have previously known cardiovascular disease. They analyzed 25(OH)D concentrations, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and major incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality using individual participant data.

The results showed that, at low 25(OH)D concentrations, there was an inverse association between 25(OH)D and incident CHD, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Next, the team conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis on 333,002 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who were of European ancestry and had both a valid 25(OH)D measurement and genetic data that passed quality-control steps.

Information on 31,362 participants in the Copenhagen population-based studies was also included, giving a total of 386,406 individuals, of whom 33,546 had CHD, 18,166 had a stroke, and 27,885 died.

The mean age of participants ranged from 54.8 to 57.5 years, and between 53.4% and 55.4% were female.

Up to 7% of study participants were vitamin D deficient

The 25(OH)D analysis indicated that 3.9% of UK Biobank and 3.7% of Copenhagen study participants were deficient, compared with 6.9% in EPIC-CVD.

Across the full range of 25(OH)D concentrations, there was no significant association between genetically predicted 25(OH)D levels and CHD, stroke, or all-cause mortality.

However, restricting the analysis to individuals deemed vitamin D deficient (25[OH]D concentration < 25 nmol/L) revealed there was “strong evidence” for an inverse association with all-cause mortality, at an odds ratio per 10 nmol/L increase in genetically predicted 25(OH)D concentration of 0.69 (P < .0001), the team notes.

There were also nonsignificant associations between being in the deficient stratum and CHD, at an odds ratio of 0.89 (P = .14), and stroke, at an odds ratio of 0.85 (P = .09).

Further analysis suggests the association between 25(OH)D concentrations and all-cause mortality has a “clear threshold shape,” the researchers say, with evidence of an inverse association at concentrations below 40 nmol/L and null associations above that threshold.

They acknowledge, however, that their study has several potential limitations, including the assumption in their Mendelian randomization that the “only causal pathway from the genetic variants to the outcome is via 25(OH)D concentrations.”

Moreover, the genetic variants may affect 25(OH)D concentrations in a different way from “dietary supplementation or other clinical interventions.”

They also concede that their study was limited to middle-aged participants of European ancestries, which means the findings “might not be applicable to other populations.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Health Data Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and International Agency for Research on Cancer. Dr. Burgess has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves first drug for treatment of resistant cytomegalovirus infection

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for posttransplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) that is resistant to other drugs.

There are an estimated 200,000 adult transplants every year globally. CMV, a type of herpes virus, is one of the most common infections in transplant patients, occurring in 16%-56% of solid organ transplant recipients and 30%-70% of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, according to Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the company that manufactures Livtencity. For immunosuppressed transplant patients, CMV infection can lead to complications that include loss of the transplanted or organ or even death.

“Cytomegalovirus infections that are resistant or do not respond to available drugs are of even greater concern,” John Farley, MD, MPH, the director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “Today’s approval helps meet a significant unmet medical need by providing a treatment option for this patient population.”

Livtencity, which is taken orally, works by preventing the activity of the enzyme responsible for virus replication. The approval, announced Nov. 23, was based on a phase 3 clinical trial that compared Livtencity with conventional antiviral treatments in the achievement of CMV DNA concentration levels below what is measurable in transplant patients with CMV infection that is refractory or treatment-resistant. After 8 weeks, of the 235 patients who received Livtencity, 56% achieved this primary endpoint, compared with 24% of the 117 patients who received conventional antiviral treatments, the press release says.

The most reported adverse reactions of Livtencity were taste disturbance, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

“We are grateful for the contributions of the patients and clinicians who participated in our clinical trials, as well as the dedication of our scientists and researchers,” Ramona Sequeira, president of the Takeda’s U.S. Business Unit and Global Portfolio Commercialization, said in a statement. “People undergoing transplants have a lengthy and complex health care journey; with the approval of this treatment, we’re proud to offer these individuals a new oral antiviral to fight CMV infection and disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for posttransplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) that is resistant to other drugs.

There are an estimated 200,000 adult transplants every year globally. CMV, a type of herpes virus, is one of the most common infections in transplant patients, occurring in 16%-56% of solid organ transplant recipients and 30%-70% of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, according to Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the company that manufactures Livtencity. For immunosuppressed transplant patients, CMV infection can lead to complications that include loss of the transplanted or organ or even death.

“Cytomegalovirus infections that are resistant or do not respond to available drugs are of even greater concern,” John Farley, MD, MPH, the director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “Today’s approval helps meet a significant unmet medical need by providing a treatment option for this patient population.”

Livtencity, which is taken orally, works by preventing the activity of the enzyme responsible for virus replication. The approval, announced Nov. 23, was based on a phase 3 clinical trial that compared Livtencity with conventional antiviral treatments in the achievement of CMV DNA concentration levels below what is measurable in transplant patients with CMV infection that is refractory or treatment-resistant. After 8 weeks, of the 235 patients who received Livtencity, 56% achieved this primary endpoint, compared with 24% of the 117 patients who received conventional antiviral treatments, the press release says.

The most reported adverse reactions of Livtencity were taste disturbance, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

“We are grateful for the contributions of the patients and clinicians who participated in our clinical trials, as well as the dedication of our scientists and researchers,” Ramona Sequeira, president of the Takeda’s U.S. Business Unit and Global Portfolio Commercialization, said in a statement. “People undergoing transplants have a lengthy and complex health care journey; with the approval of this treatment, we’re proud to offer these individuals a new oral antiviral to fight CMV infection and disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for posttransplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) that is resistant to other drugs.

There are an estimated 200,000 adult transplants every year globally. CMV, a type of herpes virus, is one of the most common infections in transplant patients, occurring in 16%-56% of solid organ transplant recipients and 30%-70% of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, according to Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the company that manufactures Livtencity. For immunosuppressed transplant patients, CMV infection can lead to complications that include loss of the transplanted or organ or even death.

“Cytomegalovirus infections that are resistant or do not respond to available drugs are of even greater concern,” John Farley, MD, MPH, the director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “Today’s approval helps meet a significant unmet medical need by providing a treatment option for this patient population.”

Livtencity, which is taken orally, works by preventing the activity of the enzyme responsible for virus replication. The approval, announced Nov. 23, was based on a phase 3 clinical trial that compared Livtencity with conventional antiviral treatments in the achievement of CMV DNA concentration levels below what is measurable in transplant patients with CMV infection that is refractory or treatment-resistant. After 8 weeks, of the 235 patients who received Livtencity, 56% achieved this primary endpoint, compared with 24% of the 117 patients who received conventional antiviral treatments, the press release says.

The most reported adverse reactions of Livtencity were taste disturbance, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

“We are grateful for the contributions of the patients and clinicians who participated in our clinical trials, as well as the dedication of our scientists and researchers,” Ramona Sequeira, president of the Takeda’s U.S. Business Unit and Global Portfolio Commercialization, said in a statement. “People undergoing transplants have a lengthy and complex health care journey; with the approval of this treatment, we’re proud to offer these individuals a new oral antiviral to fight CMV infection and disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple Lesions With Recurrent Bleeding

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

A 63-year-old man with frontal bossing and a history of jaw cysts presented with numerous lesions on the scalp, trunk, and legs with recurrent bleeding. Both of his siblings had similar findings. Many lesions had been present for at least 40 years. Physical examination revealed a large, irregular, atrophic, hyperpigmented plaque on the central scalp with multiple translucent hyperpigmented papules at the periphery (top). Similar papules and plaques were present at the temples, around the waist, and on the distal lower extremities, leading to surgical excision of the largest leg lesions. In addition, there were many pinpoint pits on both palms (bottom). A biopsy was submitted for review, which confirmed basal cell carcinomas on the scalp.

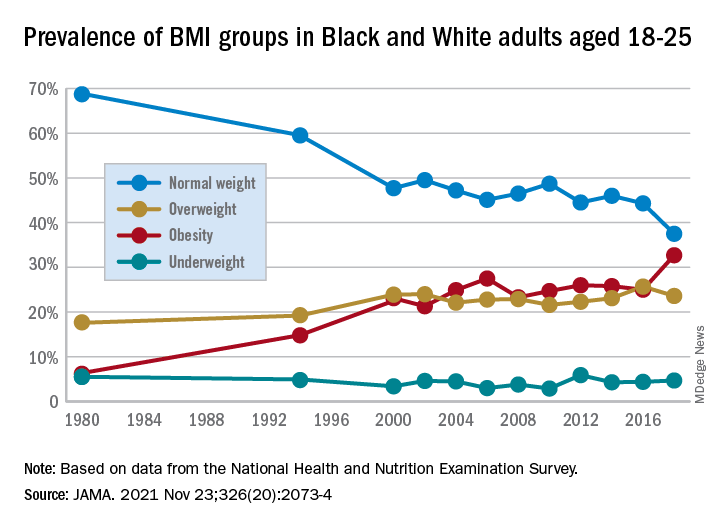

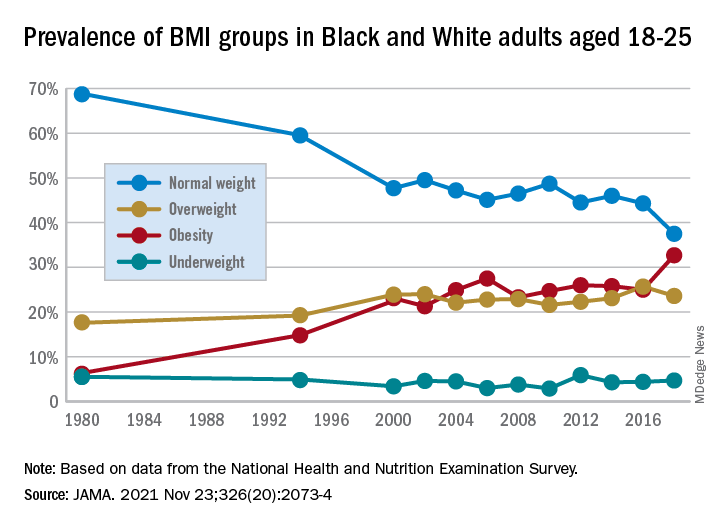

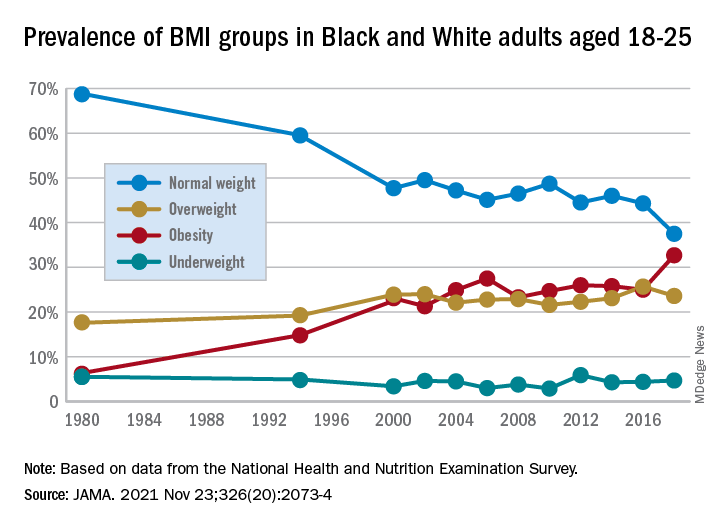

U.S. obesity rates soar in early adulthood

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Malpractice case: What really killed this patient? Experts disagree

A patient with many comorbidities undergoing surgery presents a number of challenges to the healthcare team. This case highlights why solid preparation for the pre-and post-op care of such patients is so important.

A 56-year-old morbidly obese man with a history of hypertension, diabetes, sleep apnea, and elevated cholesterol presented to an ambulatory surgery center for knee arthroscopy. Following a brief pre-op assessment, his airway was rated a III using both the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and Mallampati classification systems. It was decided to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) with 100 µg of fentanyl and 2 mgmidazolam, followed by inhalation anesthesia.

After the procedure, the LMA was removed and the patient was moved to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The patient was unresponsive for about 20 minutes and exhibited signs of respiratory distress. Efforts were made to open the airway with jaw thrusts and nasal trumpet. The anesthesiologist determined that the patient was suffering from congestive heart failure, aspiration, or pulmonary edema.

The anesthesiologist administered 40 µg of naloxone. The patient began to awaken but had oxygen saturation readings in the high 70s. The patient was encouraged to take slow, deep breaths. Rhonchi were heard, and the patient complained of shortness of breath. The ECG reading was unchanged from the pre-op test.

Thirty minutes after the first dose, a second dose of 40 µg naloxone was administered with no improvement. Oxygen saturation remained between 79% and 88%. Albuterol was given with little effect. The patient’s respiration rate was 44.

The patient was reintubated. Copious pink, frothy fluid was suctioned from the endotracheal tube. The patient received propofol, urosemide, and paralytic agents with the code team present to assist. The patient’s heart rate continued to decline to about 45 beats/min. The patient was transferred to a hospital emergency department.

Upon arrival in the emergency department, the patient was in asystolic arrest. Attempts to place a transvenous pacer were unsuccessful. The nasogastric tube returned 400 cc of brown coffee-grounds gastric fluid. After 30 minutes of CPR, the patient was pronounced dead.

The autopsy report noted no apparent airway obstruction, so the pathologist determined that the cause of death was flash pulmonary edema. Negative pressure pulmonary edema is a form of flash pulmonary edema caused by forceful inspiratory efforts made against a blocked airway. Toxic levels of ropivacaine were found in the patient’s blood. The pathologist noted hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a grossly enlarged heart.

The patient’s family filed a claim after his death. The plaintiffs argued that the LMA was removed too soon for a patient with sleep apnea and a class III Mallampati score. They raised questions about the high levels of ropivacaine and wondered whether it contributed to bradycardia. They claimed that the reintubation took too long, resulting in high end-tidal CO2. They also noted inconsistent documentation between PACU nurses and the anesthesiologist.

Some defense experts were supportive of the care, stating that the cause of death was probably from a fatal arrhythmia due to hypotension and an enlarged heart. The defense experts questioned whether undiagnosed pulmonary hypertension would explain the failure to respond to furosemide. It was noted that both of the patient’s parents had died suddenly following surgeries. The assumed cause of their deaths was coronary artery disease. This case settled.

How the claim may have been prevented: Dr. Feldman’s tips

Prevent adverse events by managing clinical decisions based on the individual patient’s needs. The history of sleep apnea and a rating of a Mallampati class III airway in this ASA III patient indicated a high risk for a difficult intubation. Consideration should have been given to performing the procedure in a hospital rather than in an ambulatory surgery center. The overall goal is to maintain a secure airway until the patient is able to maintain it on their own.

Preclude malpractice claims by having good communication with patients. Unfortunately, anesthesiologists don’t typically have an opportunity to develop a relationship with patients, but for patients at high risk, like this one, mandatory visits or calls to an anesthesiology-run pre-op clinic or ambulatory surgery center would give the anesthesiologist the opportunity to have a lengthy and informative discussion about risks, benefits, and alternatives. In addition, it would give the anesthesiologist time to discuss risks with both the surgeon and the patient.

Prevail in lawsuits by fully documenting the preoperative anesthesia assessment. There were questions about inconsistencies in documentation between the PACU nurses and anesthesiologists. Frequent huddles between the PACU staff (including nurses and physicians) may lead not only to more coordinated care but also to more consistent documentation, which will show that the care team acted together in caring for the patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A patient with many comorbidities undergoing surgery presents a number of challenges to the healthcare team. This case highlights why solid preparation for the pre-and post-op care of such patients is so important.

A 56-year-old morbidly obese man with a history of hypertension, diabetes, sleep apnea, and elevated cholesterol presented to an ambulatory surgery center for knee arthroscopy. Following a brief pre-op assessment, his airway was rated a III using both the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and Mallampati classification systems. It was decided to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) with 100 µg of fentanyl and 2 mgmidazolam, followed by inhalation anesthesia.

After the procedure, the LMA was removed and the patient was moved to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The patient was unresponsive for about 20 minutes and exhibited signs of respiratory distress. Efforts were made to open the airway with jaw thrusts and nasal trumpet. The anesthesiologist determined that the patient was suffering from congestive heart failure, aspiration, or pulmonary edema.

The anesthesiologist administered 40 µg of naloxone. The patient began to awaken but had oxygen saturation readings in the high 70s. The patient was encouraged to take slow, deep breaths. Rhonchi were heard, and the patient complained of shortness of breath. The ECG reading was unchanged from the pre-op test.

Thirty minutes after the first dose, a second dose of 40 µg naloxone was administered with no improvement. Oxygen saturation remained between 79% and 88%. Albuterol was given with little effect. The patient’s respiration rate was 44.

The patient was reintubated. Copious pink, frothy fluid was suctioned from the endotracheal tube. The patient received propofol, urosemide, and paralytic agents with the code team present to assist. The patient’s heart rate continued to decline to about 45 beats/min. The patient was transferred to a hospital emergency department.

Upon arrival in the emergency department, the patient was in asystolic arrest. Attempts to place a transvenous pacer were unsuccessful. The nasogastric tube returned 400 cc of brown coffee-grounds gastric fluid. After 30 minutes of CPR, the patient was pronounced dead.

The autopsy report noted no apparent airway obstruction, so the pathologist determined that the cause of death was flash pulmonary edema. Negative pressure pulmonary edema is a form of flash pulmonary edema caused by forceful inspiratory efforts made against a blocked airway. Toxic levels of ropivacaine were found in the patient’s blood. The pathologist noted hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a grossly enlarged heart.

The patient’s family filed a claim after his death. The plaintiffs argued that the LMA was removed too soon for a patient with sleep apnea and a class III Mallampati score. They raised questions about the high levels of ropivacaine and wondered whether it contributed to bradycardia. They claimed that the reintubation took too long, resulting in high end-tidal CO2. They also noted inconsistent documentation between PACU nurses and the anesthesiologist.

Some defense experts were supportive of the care, stating that the cause of death was probably from a fatal arrhythmia due to hypotension and an enlarged heart. The defense experts questioned whether undiagnosed pulmonary hypertension would explain the failure to respond to furosemide. It was noted that both of the patient’s parents had died suddenly following surgeries. The assumed cause of their deaths was coronary artery disease. This case settled.

How the claim may have been prevented: Dr. Feldman’s tips

Prevent adverse events by managing clinical decisions based on the individual patient’s needs. The history of sleep apnea and a rating of a Mallampati class III airway in this ASA III patient indicated a high risk for a difficult intubation. Consideration should have been given to performing the procedure in a hospital rather than in an ambulatory surgery center. The overall goal is to maintain a secure airway until the patient is able to maintain it on their own.

Preclude malpractice claims by having good communication with patients. Unfortunately, anesthesiologists don’t typically have an opportunity to develop a relationship with patients, but for patients at high risk, like this one, mandatory visits or calls to an anesthesiology-run pre-op clinic or ambulatory surgery center would give the anesthesiologist the opportunity to have a lengthy and informative discussion about risks, benefits, and alternatives. In addition, it would give the anesthesiologist time to discuss risks with both the surgeon and the patient.

Prevail in lawsuits by fully documenting the preoperative anesthesia assessment. There were questions about inconsistencies in documentation between the PACU nurses and anesthesiologists. Frequent huddles between the PACU staff (including nurses and physicians) may lead not only to more coordinated care but also to more consistent documentation, which will show that the care team acted together in caring for the patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A patient with many comorbidities undergoing surgery presents a number of challenges to the healthcare team. This case highlights why solid preparation for the pre-and post-op care of such patients is so important.

A 56-year-old morbidly obese man with a history of hypertension, diabetes, sleep apnea, and elevated cholesterol presented to an ambulatory surgery center for knee arthroscopy. Following a brief pre-op assessment, his airway was rated a III using both the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and Mallampati classification systems. It was decided to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) with 100 µg of fentanyl and 2 mgmidazolam, followed by inhalation anesthesia.

After the procedure, the LMA was removed and the patient was moved to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The patient was unresponsive for about 20 minutes and exhibited signs of respiratory distress. Efforts were made to open the airway with jaw thrusts and nasal trumpet. The anesthesiologist determined that the patient was suffering from congestive heart failure, aspiration, or pulmonary edema.

The anesthesiologist administered 40 µg of naloxone. The patient began to awaken but had oxygen saturation readings in the high 70s. The patient was encouraged to take slow, deep breaths. Rhonchi were heard, and the patient complained of shortness of breath. The ECG reading was unchanged from the pre-op test.

Thirty minutes after the first dose, a second dose of 40 µg naloxone was administered with no improvement. Oxygen saturation remained between 79% and 88%. Albuterol was given with little effect. The patient’s respiration rate was 44.

The patient was reintubated. Copious pink, frothy fluid was suctioned from the endotracheal tube. The patient received propofol, urosemide, and paralytic agents with the code team present to assist. The patient’s heart rate continued to decline to about 45 beats/min. The patient was transferred to a hospital emergency department.

Upon arrival in the emergency department, the patient was in asystolic arrest. Attempts to place a transvenous pacer were unsuccessful. The nasogastric tube returned 400 cc of brown coffee-grounds gastric fluid. After 30 minutes of CPR, the patient was pronounced dead.

The autopsy report noted no apparent airway obstruction, so the pathologist determined that the cause of death was flash pulmonary edema. Negative pressure pulmonary edema is a form of flash pulmonary edema caused by forceful inspiratory efforts made against a blocked airway. Toxic levels of ropivacaine were found in the patient’s blood. The pathologist noted hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a grossly enlarged heart.

The patient’s family filed a claim after his death. The plaintiffs argued that the LMA was removed too soon for a patient with sleep apnea and a class III Mallampati score. They raised questions about the high levels of ropivacaine and wondered whether it contributed to bradycardia. They claimed that the reintubation took too long, resulting in high end-tidal CO2. They also noted inconsistent documentation between PACU nurses and the anesthesiologist.

Some defense experts were supportive of the care, stating that the cause of death was probably from a fatal arrhythmia due to hypotension and an enlarged heart. The defense experts questioned whether undiagnosed pulmonary hypertension would explain the failure to respond to furosemide. It was noted that both of the patient’s parents had died suddenly following surgeries. The assumed cause of their deaths was coronary artery disease. This case settled.

How the claim may have been prevented: Dr. Feldman’s tips

Prevent adverse events by managing clinical decisions based on the individual patient’s needs. The history of sleep apnea and a rating of a Mallampati class III airway in this ASA III patient indicated a high risk for a difficult intubation. Consideration should have been given to performing the procedure in a hospital rather than in an ambulatory surgery center. The overall goal is to maintain a secure airway until the patient is able to maintain it on their own.

Preclude malpractice claims by having good communication with patients. Unfortunately, anesthesiologists don’t typically have an opportunity to develop a relationship with patients, but for patients at high risk, like this one, mandatory visits or calls to an anesthesiology-run pre-op clinic or ambulatory surgery center would give the anesthesiologist the opportunity to have a lengthy and informative discussion about risks, benefits, and alternatives. In addition, it would give the anesthesiologist time to discuss risks with both the surgeon and the patient.

Prevail in lawsuits by fully documenting the preoperative anesthesia assessment. There were questions about inconsistencies in documentation between the PACU nurses and anesthesiologists. Frequent huddles between the PACU staff (including nurses and physicians) may lead not only to more coordinated care but also to more consistent documentation, which will show that the care team acted together in caring for the patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescents, THC, and the risk of psychosis

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

Since the recent legalization and decriminalization of cannabis (marijuana) use throughout the United States, adolescents’ access to, and use of, cannabis has increased.1 Cannabis products have been marketed in ways that attract adolescents, such as edible gummies, cookies, and hard candies, as well as by vaping.1 The adolescent years are a delicate period of development during which individuals are prone to psychiatric illness, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2,3 Here we discuss the relationship between adolescent cannabis use and the development of psychosis.

How cannabis can affect the adolescent brain

The 2 main psychotropic substances found within the cannabis plant are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).1,4 Endocannabinoids are fatty acid derivatives produced in the brain that bind to cannabinoid (CB) receptors found in the brain and the peripheral nervous system.1,4

During adolescence, neurodevelopment and neurochemical balances are evolving, and it’s during this period that the bulk of prefrontal pruning occurs, especially in the glutamatergic and gamma aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) neural pathways.5 THC affects the CB1 receptors by downregulating the neuron receptors, which then alters the maturation of the prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons. Also, THC affects the upregulation of the microglia located on the CB2 receptors, thereby altering synaptic pruning even further.2,5

All of these changes can cause brain insults that can contribute to the precipitation of psychotic decompensation in adolescents who ingest products that contain THC. In addition, consuming THC might hasten the progression of disorder in adolescents who are genetically predisposed to psychotic disorders. However, existing studies must be interpreted with caution because there are other contributing risk factors for psychosis, such as social isolation, that can alter dopamine signaling as well as oligodendrocyte maturation, which can affect myelination in the prefrontal area of the evolving brain. Factors such as increased academic demand can alter the release of cortisol, which in turn affects the dopamine response as well as the structure of the hippocampus as it responds to cortisol. With all of these contributing factors, it is difficult to attribute psychosis in adolescents solely to the use of THC.5

How to discuss cannabis usewith adolescents

Clinicians should engage in open-ended therapeutic conversations about cannabis use with their adolescent patients, including the various types of cannabis and methods of use (ingestion vs inhalation, etc). Educate patients about the acute and long-term effects of THC use, including an increased risk of depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse in adulthood.

For a patient who has experienced a psychotic episode, early intervention has proven to result in greater treatment response and functional improvement because it reduces brain exposure to neurotoxic effects in adolescents.3 Access to community resources such as school counselors can help to create coping strategies and enhance family support, which can optimize treatment outcomes and medication adherence, all of which will minimize the likelihood of another psychotic episode. Kelleher et al6 found an increased risk of suicidal behavior after a psychotic experience from any cause in adolescents and young adults, and thereby recommended that clinicians conduct continuous assessment of suicidal ideation in such patients.