User login

Virtual center boosts liver transplant listings in rural area

A “virtual” liver transplant center servicing Vermont and New Hampshire has improved access to liver transplant listing among patients in rural areas of the region, according to a new analysis.

The virtual center was established in 2016 at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, and it allows patients to receive pre–liver transplant evaluations, testing, and care and posttransplant follow-up there rather than at the liver transplant center that conducts the surgery. The center includes two hepatologists, two associate care providers, and a nurse liver transplant coordinator at DHMC, and led to increased transplant listing in the vicinity, according to Margaret Liu, MD, who presented the study at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“The initiation of this Virtual Liver Transplant Center has been able to provide patients with the ability to get a full liver transplant workup and evaluation at a center near their home rather than the often time-consuming and costly process of potentially multiple trips to a liver transplant center up to 250 miles away for a full transplant evaluation,” said Dr. Liu in an interview. Dr. Liu is an internal medicine resident at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center.

“Our results did show that the initiation of a virtual liver transplant center correlated with an increased and sustained liver transplant listing rate within 60 miles of Dartmouth over that particular study period. Conversely there was no significant change in the listing rate of New Hampshire zip codes that were within 60 miles of the nearest transplant center during the same study period,” said Dr. Liu.

The center receives referrals of patients who are potential candidates for liver transplant listing from practices throughout New Hampshire and Vermont, or from their own center. Their specialists conduct full testing, including a full liver transplant workup that includes evaluation of the patient’s general health and social factors, prior to sending the patient to the actual liver transplant center for their evaluation and transplant surgery. “We essentially do all of the pre–liver transplant workup, a formal liver transplant evaluation, and then the whole packet gets sent to an actual liver transplant center to expedite the process of getting listed for liver transplant. We’re able to streamline the process, so they get everything done here at a hospital near their home. If that requires multiple trips, it’s a lot more doable for the patients,” said Dr. Liu.

The researchers defined urban areas as having more than 50,000 people per square mile and within 30 miles of the nearest hospital, and rural as fewer than 10,000 and more than 60 miles from the nearest hospital. They used the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to determine the number of liver transplant listings per zip code.

Between 2015 and 2019, the frequency of liver transplant listings per 10,000 people remained nearly unchanged in the metropolitan area of southern New Hampshire, ranging from around 0.36 to 0.75. In the rural area within 60 miles of DHMC, the frequency increased from about 0.7 per 10,000 in 2015 to about 1.4 in 2016 and 0.9 in 2017. There was an increase to nearly 3 in 10,000 in 2018, and the frequency was just over 2 in 2019.

The model has the potential to be used in other areas, according to Dr. Liu. “This could potentially be implemented in other rural areas that do not have a transplant center or don’t have a formal liver transplant evaluation process,” said Dr. Liu.

While other centers may have taken on some aspects of liver transplant evaluation and posttransplant care, the Virtual Liver Transplant Center is unique in that a great deal of effort has gone into covering all of a patient’s needs for the liver transplant evaluation. “It’s really the formalization that, from what I have researched, has not been done before,” said Dr. Liu.

The model addresses transplant-listing disparity, as well as improves patient quality of life through reduction in travel, according to Mayur Brahmania, MD, of Western University, London, Ont., who moderated the session. “They’ve proven that they can get more of their patients listed over the study period, which I think is amazing. The next step, I think, would be about whether getting them onto the transplant list actually made a difference in terms of outcome – looking at their wait list mortality, looking at how many of these patients actually got a liver transplantation. That’s the ultimate outcome,” said Dr. Brahmania.

He also noted the challenge of setting up a virtual center. “You have to have allied health staff – addiction counselors, physical therapists, dietitians, social workers. You need to have the appropriate ancillary services like cardiac testing, pulmonary function testing. It’s quite an endeavor, and if the program isn’t too enthusiastic or doesn’t have a local champion, it’s really hard to get something like this started off. So kudos to them for taking on this challenge and getting this up and running over the last 5 years,” said Dr. Brahmania.

Dr. Liu and Dr. Brahmania have no relevant financial disclosures.

A “virtual” liver transplant center servicing Vermont and New Hampshire has improved access to liver transplant listing among patients in rural areas of the region, according to a new analysis.

The virtual center was established in 2016 at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, and it allows patients to receive pre–liver transplant evaluations, testing, and care and posttransplant follow-up there rather than at the liver transplant center that conducts the surgery. The center includes two hepatologists, two associate care providers, and a nurse liver transplant coordinator at DHMC, and led to increased transplant listing in the vicinity, according to Margaret Liu, MD, who presented the study at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“The initiation of this Virtual Liver Transplant Center has been able to provide patients with the ability to get a full liver transplant workup and evaluation at a center near their home rather than the often time-consuming and costly process of potentially multiple trips to a liver transplant center up to 250 miles away for a full transplant evaluation,” said Dr. Liu in an interview. Dr. Liu is an internal medicine resident at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center.

“Our results did show that the initiation of a virtual liver transplant center correlated with an increased and sustained liver transplant listing rate within 60 miles of Dartmouth over that particular study period. Conversely there was no significant change in the listing rate of New Hampshire zip codes that were within 60 miles of the nearest transplant center during the same study period,” said Dr. Liu.

The center receives referrals of patients who are potential candidates for liver transplant listing from practices throughout New Hampshire and Vermont, or from their own center. Their specialists conduct full testing, including a full liver transplant workup that includes evaluation of the patient’s general health and social factors, prior to sending the patient to the actual liver transplant center for their evaluation and transplant surgery. “We essentially do all of the pre–liver transplant workup, a formal liver transplant evaluation, and then the whole packet gets sent to an actual liver transplant center to expedite the process of getting listed for liver transplant. We’re able to streamline the process, so they get everything done here at a hospital near their home. If that requires multiple trips, it’s a lot more doable for the patients,” said Dr. Liu.

The researchers defined urban areas as having more than 50,000 people per square mile and within 30 miles of the nearest hospital, and rural as fewer than 10,000 and more than 60 miles from the nearest hospital. They used the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to determine the number of liver transplant listings per zip code.

Between 2015 and 2019, the frequency of liver transplant listings per 10,000 people remained nearly unchanged in the metropolitan area of southern New Hampshire, ranging from around 0.36 to 0.75. In the rural area within 60 miles of DHMC, the frequency increased from about 0.7 per 10,000 in 2015 to about 1.4 in 2016 and 0.9 in 2017. There was an increase to nearly 3 in 10,000 in 2018, and the frequency was just over 2 in 2019.

The model has the potential to be used in other areas, according to Dr. Liu. “This could potentially be implemented in other rural areas that do not have a transplant center or don’t have a formal liver transplant evaluation process,” said Dr. Liu.

While other centers may have taken on some aspects of liver transplant evaluation and posttransplant care, the Virtual Liver Transplant Center is unique in that a great deal of effort has gone into covering all of a patient’s needs for the liver transplant evaluation. “It’s really the formalization that, from what I have researched, has not been done before,” said Dr. Liu.

The model addresses transplant-listing disparity, as well as improves patient quality of life through reduction in travel, according to Mayur Brahmania, MD, of Western University, London, Ont., who moderated the session. “They’ve proven that they can get more of their patients listed over the study period, which I think is amazing. The next step, I think, would be about whether getting them onto the transplant list actually made a difference in terms of outcome – looking at their wait list mortality, looking at how many of these patients actually got a liver transplantation. That’s the ultimate outcome,” said Dr. Brahmania.

He also noted the challenge of setting up a virtual center. “You have to have allied health staff – addiction counselors, physical therapists, dietitians, social workers. You need to have the appropriate ancillary services like cardiac testing, pulmonary function testing. It’s quite an endeavor, and if the program isn’t too enthusiastic or doesn’t have a local champion, it’s really hard to get something like this started off. So kudos to them for taking on this challenge and getting this up and running over the last 5 years,” said Dr. Brahmania.

Dr. Liu and Dr. Brahmania have no relevant financial disclosures.

A “virtual” liver transplant center servicing Vermont and New Hampshire has improved access to liver transplant listing among patients in rural areas of the region, according to a new analysis.

The virtual center was established in 2016 at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, and it allows patients to receive pre–liver transplant evaluations, testing, and care and posttransplant follow-up there rather than at the liver transplant center that conducts the surgery. The center includes two hepatologists, two associate care providers, and a nurse liver transplant coordinator at DHMC, and led to increased transplant listing in the vicinity, according to Margaret Liu, MD, who presented the study at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“The initiation of this Virtual Liver Transplant Center has been able to provide patients with the ability to get a full liver transplant workup and evaluation at a center near their home rather than the often time-consuming and costly process of potentially multiple trips to a liver transplant center up to 250 miles away for a full transplant evaluation,” said Dr. Liu in an interview. Dr. Liu is an internal medicine resident at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center.

“Our results did show that the initiation of a virtual liver transplant center correlated with an increased and sustained liver transplant listing rate within 60 miles of Dartmouth over that particular study period. Conversely there was no significant change in the listing rate of New Hampshire zip codes that were within 60 miles of the nearest transplant center during the same study period,” said Dr. Liu.

The center receives referrals of patients who are potential candidates for liver transplant listing from practices throughout New Hampshire and Vermont, or from their own center. Their specialists conduct full testing, including a full liver transplant workup that includes evaluation of the patient’s general health and social factors, prior to sending the patient to the actual liver transplant center for their evaluation and transplant surgery. “We essentially do all of the pre–liver transplant workup, a formal liver transplant evaluation, and then the whole packet gets sent to an actual liver transplant center to expedite the process of getting listed for liver transplant. We’re able to streamline the process, so they get everything done here at a hospital near their home. If that requires multiple trips, it’s a lot more doable for the patients,” said Dr. Liu.

The researchers defined urban areas as having more than 50,000 people per square mile and within 30 miles of the nearest hospital, and rural as fewer than 10,000 and more than 60 miles from the nearest hospital. They used the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to determine the number of liver transplant listings per zip code.

Between 2015 and 2019, the frequency of liver transplant listings per 10,000 people remained nearly unchanged in the metropolitan area of southern New Hampshire, ranging from around 0.36 to 0.75. In the rural area within 60 miles of DHMC, the frequency increased from about 0.7 per 10,000 in 2015 to about 1.4 in 2016 and 0.9 in 2017. There was an increase to nearly 3 in 10,000 in 2018, and the frequency was just over 2 in 2019.

The model has the potential to be used in other areas, according to Dr. Liu. “This could potentially be implemented in other rural areas that do not have a transplant center or don’t have a formal liver transplant evaluation process,” said Dr. Liu.

While other centers may have taken on some aspects of liver transplant evaluation and posttransplant care, the Virtual Liver Transplant Center is unique in that a great deal of effort has gone into covering all of a patient’s needs for the liver transplant evaluation. “It’s really the formalization that, from what I have researched, has not been done before,” said Dr. Liu.

The model addresses transplant-listing disparity, as well as improves patient quality of life through reduction in travel, according to Mayur Brahmania, MD, of Western University, London, Ont., who moderated the session. “They’ve proven that they can get more of their patients listed over the study period, which I think is amazing. The next step, I think, would be about whether getting them onto the transplant list actually made a difference in terms of outcome – looking at their wait list mortality, looking at how many of these patients actually got a liver transplantation. That’s the ultimate outcome,” said Dr. Brahmania.

He also noted the challenge of setting up a virtual center. “You have to have allied health staff – addiction counselors, physical therapists, dietitians, social workers. You need to have the appropriate ancillary services like cardiac testing, pulmonary function testing. It’s quite an endeavor, and if the program isn’t too enthusiastic or doesn’t have a local champion, it’s really hard to get something like this started off. So kudos to them for taking on this challenge and getting this up and running over the last 5 years,” said Dr. Brahmania.

Dr. Liu and Dr. Brahmania have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING

Merck’s COVID-19 pill may be less effective than first hoped

According to an analysis by scientists at the Food and Drug Administration, the experimental pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 by about 30%, compared to a placebo, and the pill showed no benefit for people with antibodies against COVID-19 from prior infection.

The updated analysis showed 48 hospitalizations or deaths among study participants who were randomly assigned to take the antiviral drug, compared to 68 among those who took a placebo.

Those results come from the full set of 1,433 patients who were randomized in the clinical trial, which just became available last week.

Initial results from the first 775 patients enrolled in the clinical trial, which were issued in a company news release in October, had said the drug cut the risk of hospitalization or death for patients at high risk of severe disease by about 50%.

Merck has been producing millions of doses of molnupiravir, which is the first antiviral pill to treat COVID-19 infections. The United Kingdom’s drug regulator authorized use of the medication in early November. The company said it expected to distribute the medication globally by the end of 2021.

In October, two Indian drug companies halted late-stage clinical trials of a generic version of molnupiravir after the studies failed to find any benefit to patients with moderate COVID-19. Trials in patients with milder symptoms are still ongoing.

On Nov. 27, the New England Journal of Medicine postponed its planned early release of the molnupiravir study results, citing “new information.”

The medication is designed to be given as four pills taken every 12 hours for 5 days. It’s most effective when taken within the first few days of new symptoms, something that requires convenient and affordable testing.

The new results seem to put molnupiravir far below the effectiveness of existing treatments.

The infused monoclonal antibody cocktail REGEN-COV, which the FDA has already authorized for emergency use, is about 85% effective at preventing hospitalization or death in patients who are at risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes, and it appears to be just as effective in people who already have antibodies against COVID-19, which is why it is being given to both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, the FDA said.

In early November, Pfizer said its experimental antiviral pill Paxlovid cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 89%.

In briefing documents posted ahead of an advisory committee meeting Nov. 30, the FDA highlights other potential safety issues with the Merck drug, which works by causing the virus to make mistakes as it copies itself, eventually causing the virus to mutate itself to death.

The agency has asked the advisory committee to weigh in on the right patient population for the drug: Should pregnant women get it? Could the drug harm a developing fetus?

Should vaccinated people with breakthrough infections get it? Would it work for them? People with reduced immune function are more likely to get a breakthrough infection. They’re also more likely to shed virus for a longer period of time, making them perfect incubators for variants. What could happen if we give this type of patient a drug that increases mutations?

And what about mutations caused by the medication? Could they increase the potential for more variants? The agency concluded the risk of this happening was low.

In animal studies, the drug impacted bone formation. For this reason, the agency has agreed with the drug company that molnupiravir should not be given to anyone under the age of 18.

Aside from these concerns, the FDA says there were no major safety issues among people who took part in the clinical trial, though they acknowledge that number is small.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

According to an analysis by scientists at the Food and Drug Administration, the experimental pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 by about 30%, compared to a placebo, and the pill showed no benefit for people with antibodies against COVID-19 from prior infection.

The updated analysis showed 48 hospitalizations or deaths among study participants who were randomly assigned to take the antiviral drug, compared to 68 among those who took a placebo.

Those results come from the full set of 1,433 patients who were randomized in the clinical trial, which just became available last week.

Initial results from the first 775 patients enrolled in the clinical trial, which were issued in a company news release in October, had said the drug cut the risk of hospitalization or death for patients at high risk of severe disease by about 50%.

Merck has been producing millions of doses of molnupiravir, which is the first antiviral pill to treat COVID-19 infections. The United Kingdom’s drug regulator authorized use of the medication in early November. The company said it expected to distribute the medication globally by the end of 2021.

In October, two Indian drug companies halted late-stage clinical trials of a generic version of molnupiravir after the studies failed to find any benefit to patients with moderate COVID-19. Trials in patients with milder symptoms are still ongoing.

On Nov. 27, the New England Journal of Medicine postponed its planned early release of the molnupiravir study results, citing “new information.”

The medication is designed to be given as four pills taken every 12 hours for 5 days. It’s most effective when taken within the first few days of new symptoms, something that requires convenient and affordable testing.

The new results seem to put molnupiravir far below the effectiveness of existing treatments.

The infused monoclonal antibody cocktail REGEN-COV, which the FDA has already authorized for emergency use, is about 85% effective at preventing hospitalization or death in patients who are at risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes, and it appears to be just as effective in people who already have antibodies against COVID-19, which is why it is being given to both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, the FDA said.

In early November, Pfizer said its experimental antiviral pill Paxlovid cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 89%.

In briefing documents posted ahead of an advisory committee meeting Nov. 30, the FDA highlights other potential safety issues with the Merck drug, which works by causing the virus to make mistakes as it copies itself, eventually causing the virus to mutate itself to death.

The agency has asked the advisory committee to weigh in on the right patient population for the drug: Should pregnant women get it? Could the drug harm a developing fetus?

Should vaccinated people with breakthrough infections get it? Would it work for them? People with reduced immune function are more likely to get a breakthrough infection. They’re also more likely to shed virus for a longer period of time, making them perfect incubators for variants. What could happen if we give this type of patient a drug that increases mutations?

And what about mutations caused by the medication? Could they increase the potential for more variants? The agency concluded the risk of this happening was low.

In animal studies, the drug impacted bone formation. For this reason, the agency has agreed with the drug company that molnupiravir should not be given to anyone under the age of 18.

Aside from these concerns, the FDA says there were no major safety issues among people who took part in the clinical trial, though they acknowledge that number is small.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

According to an analysis by scientists at the Food and Drug Administration, the experimental pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 by about 30%, compared to a placebo, and the pill showed no benefit for people with antibodies against COVID-19 from prior infection.

The updated analysis showed 48 hospitalizations or deaths among study participants who were randomly assigned to take the antiviral drug, compared to 68 among those who took a placebo.

Those results come from the full set of 1,433 patients who were randomized in the clinical trial, which just became available last week.

Initial results from the first 775 patients enrolled in the clinical trial, which were issued in a company news release in October, had said the drug cut the risk of hospitalization or death for patients at high risk of severe disease by about 50%.

Merck has been producing millions of doses of molnupiravir, which is the first antiviral pill to treat COVID-19 infections. The United Kingdom’s drug regulator authorized use of the medication in early November. The company said it expected to distribute the medication globally by the end of 2021.

In October, two Indian drug companies halted late-stage clinical trials of a generic version of molnupiravir after the studies failed to find any benefit to patients with moderate COVID-19. Trials in patients with milder symptoms are still ongoing.

On Nov. 27, the New England Journal of Medicine postponed its planned early release of the molnupiravir study results, citing “new information.”

The medication is designed to be given as four pills taken every 12 hours for 5 days. It’s most effective when taken within the first few days of new symptoms, something that requires convenient and affordable testing.

The new results seem to put molnupiravir far below the effectiveness of existing treatments.

The infused monoclonal antibody cocktail REGEN-COV, which the FDA has already authorized for emergency use, is about 85% effective at preventing hospitalization or death in patients who are at risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes, and it appears to be just as effective in people who already have antibodies against COVID-19, which is why it is being given to both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients, the FDA said.

In early November, Pfizer said its experimental antiviral pill Paxlovid cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 89%.

In briefing documents posted ahead of an advisory committee meeting Nov. 30, the FDA highlights other potential safety issues with the Merck drug, which works by causing the virus to make mistakes as it copies itself, eventually causing the virus to mutate itself to death.

The agency has asked the advisory committee to weigh in on the right patient population for the drug: Should pregnant women get it? Could the drug harm a developing fetus?

Should vaccinated people with breakthrough infections get it? Would it work for them? People with reduced immune function are more likely to get a breakthrough infection. They’re also more likely to shed virus for a longer period of time, making them perfect incubators for variants. What could happen if we give this type of patient a drug that increases mutations?

And what about mutations caused by the medication? Could they increase the potential for more variants? The agency concluded the risk of this happening was low.

In animal studies, the drug impacted bone formation. For this reason, the agency has agreed with the drug company that molnupiravir should not be given to anyone under the age of 18.

Aside from these concerns, the FDA says there were no major safety issues among people who took part in the clinical trial, though they acknowledge that number is small.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Best of MS

Good data is lacking on best first-line MS drug strategies

Personalized medicine is just about the biggest buzzword in health. But neurologist Ellen M. Mowry, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, steers patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) away from the concept when she first starts talking to them about initial therapy options and possible ways to forestall disability down the line.

Good data is lacking on best first-line MS drug strategies

Personalized medicine is just about the biggest buzzword in health. But neurologist Ellen M. Mowry, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, steers patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) away from the concept when she first starts talking to them about initial therapy options and possible ways to forestall disability down the line.

Good data is lacking on best first-line MS drug strategies

Personalized medicine is just about the biggest buzzword in health. But neurologist Ellen M. Mowry, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, steers patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) away from the concept when she first starts talking to them about initial therapy options and possible ways to forestall disability down the line.

Take action: Medicare rules

First the bad news: GIs and other specialties face millions of dollars in cuts as Medicare finalized a 3.71% cut to the Physician Fee Schedule conversion factor, which could increase to near 9% if Congress doesn’t act.

Here are highlights from the 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) and Hospital Outpatient Department (HOPD)/Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) final rules.

Good news

- Telehealth reimbursement continues through December 2023.

- Medicare coverage changes from the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act were finalized and coinsurance reduction will start Jan. 1, 2022, with full phase out by 2030.

Bad news

- A 3.71% cut to MPFS 2022 conversion factor, which could result in a up to 9% cut to our practices. Email your lawmaker now.

- HOPD and ASC conversion factors will increase 2% for those that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

- New MPFS payments for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and some capsule endoscopy CPT codes not as high as expected.

First the bad news: GIs and other specialties face millions of dollars in cuts as Medicare finalized a 3.71% cut to the Physician Fee Schedule conversion factor, which could increase to near 9% if Congress doesn’t act.

Here are highlights from the 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) and Hospital Outpatient Department (HOPD)/Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) final rules.

Good news

- Telehealth reimbursement continues through December 2023.

- Medicare coverage changes from the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act were finalized and coinsurance reduction will start Jan. 1, 2022, with full phase out by 2030.

Bad news

- A 3.71% cut to MPFS 2022 conversion factor, which could result in a up to 9% cut to our practices. Email your lawmaker now.

- HOPD and ASC conversion factors will increase 2% for those that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

- New MPFS payments for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and some capsule endoscopy CPT codes not as high as expected.

First the bad news: GIs and other specialties face millions of dollars in cuts as Medicare finalized a 3.71% cut to the Physician Fee Schedule conversion factor, which could increase to near 9% if Congress doesn’t act.

Here are highlights from the 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) and Hospital Outpatient Department (HOPD)/Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) final rules.

Good news

- Telehealth reimbursement continues through December 2023.

- Medicare coverage changes from the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act were finalized and coinsurance reduction will start Jan. 1, 2022, with full phase out by 2030.

Bad news

- A 3.71% cut to MPFS 2022 conversion factor, which could result in a up to 9% cut to our practices. Email your lawmaker now.

- HOPD and ASC conversion factors will increase 2% for those that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

- New MPFS payments for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and some capsule endoscopy CPT codes not as high as expected.

People of color missing in inflammatory bowel disease trials

LAS VEGAS – Clinical trials of treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have disproportionately enrolled White people, researchers say.

These skewed demographics could result in researchers overlooking differences in how the disease and its treatments might affect other racial and ethnic groups, said Jellyana Peraza, MD, a chief resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

“The only way we can determine that therapies work differently in different populations is by including those populations in these clinical trials,” she said in an interview. “We think that diversity should be present, and that will answer some questions about the pathogenesis of the disease in general.”

Dr. Peraza presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Previous studies have found that, in trials of other conditions, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, White people have been disproportionately represented. However, little research has been conducted regarding race and ethnicity in IBD trials.

To fill that gap, Dr. Peraza and colleagues analyzed data from completed trials through the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, for the period from 2000 to 2020.

They found 22 trials conducted exclusively in the United States and 56 conducted in other countries that reported the race or ethnicity of participants; 54 trials did not include this information.

With regard to the prevalence of IBD in White people and Asian people, these populations were overrepresented in U.S. clinical trials. All other groups were underrepresented.

The researchers calculated the odds ratio of being included in an IBD clinical trial for each group. Compared with White people, all the other groups were less likely to be included except for Asian people, who were 85% more likely to be included. These ORs were all statistically significant (P < .03) except for Hispanic people (OR, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.01; P = .06).

It’s not clear why Asian people are overrepresented, Dr. Peraza said. “Honestly, that was kind of surprising for us. We initially thought that could be related to where these studies were conducted, for example, if some of them were conducted on the West Coast, where maybe more Asian communities are located. However, we didn’t find any specific association between location and Asian representation.”

IBD is more prevalent among White people, although its prevalence is increasing among other groups, Dr. Peraza said. However, that is not reflected in the trials. In an analysis of data in 5-year increments, the researchers found that the participation of White and Hispanic people in IBD trials had not changed much, whereas the participation of Black people had declined, and the participation of Asian and Native American people had increased.

On the basis of work of other researchers, Dr. Peraza said that people of color are as willing to participate in trials as White people. “There is not so much a mistrust as a lack of education and a lack of access to the tertiary centers or the centers where these studies are conducted,” she said.

Clinical trial investigators should recruit more participants from community centers, and health care practitioners should talk about the trials with people in underrepresented groups, she said. “They should have the conversation with their patients about how these clinical trials can benefit the evolution of their diseases.”

One research center that is working hard to diversify its IBD trials is the Ohio State University IBD Center, Columbus, said Anita Afzali, MD, its medical director.

“We have a great team that works actively on the recruitment of all patients,” she said in an interview. “Oftentimes, it just takes a little bit of education and spending time with the patient on discussing what the options are for them.”

Some research indicates that Black people with IBD are more likely to have fistulizing disease, Dr. Afzali said. “However, it doesn’t come so much of their differences in phenotype that we’re seeing but more so the differences in access to care and getting the appropriate therapy in a timely way.”

Dr. Peraza and Dr. Afzali disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AGA applauds researchers who are working to raise our awareness of health disparities in digestive diseases. AGA is committed to addressing this important societal issue head on. Learn more about AGA’s commitment through the AGA Equity Project.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LAS VEGAS – Clinical trials of treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have disproportionately enrolled White people, researchers say.

These skewed demographics could result in researchers overlooking differences in how the disease and its treatments might affect other racial and ethnic groups, said Jellyana Peraza, MD, a chief resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

“The only way we can determine that therapies work differently in different populations is by including those populations in these clinical trials,” she said in an interview. “We think that diversity should be present, and that will answer some questions about the pathogenesis of the disease in general.”

Dr. Peraza presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Previous studies have found that, in trials of other conditions, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, White people have been disproportionately represented. However, little research has been conducted regarding race and ethnicity in IBD trials.

To fill that gap, Dr. Peraza and colleagues analyzed data from completed trials through the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, for the period from 2000 to 2020.

They found 22 trials conducted exclusively in the United States and 56 conducted in other countries that reported the race or ethnicity of participants; 54 trials did not include this information.

With regard to the prevalence of IBD in White people and Asian people, these populations were overrepresented in U.S. clinical trials. All other groups were underrepresented.

The researchers calculated the odds ratio of being included in an IBD clinical trial for each group. Compared with White people, all the other groups were less likely to be included except for Asian people, who were 85% more likely to be included. These ORs were all statistically significant (P < .03) except for Hispanic people (OR, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.01; P = .06).

It’s not clear why Asian people are overrepresented, Dr. Peraza said. “Honestly, that was kind of surprising for us. We initially thought that could be related to where these studies were conducted, for example, if some of them were conducted on the West Coast, where maybe more Asian communities are located. However, we didn’t find any specific association between location and Asian representation.”

IBD is more prevalent among White people, although its prevalence is increasing among other groups, Dr. Peraza said. However, that is not reflected in the trials. In an analysis of data in 5-year increments, the researchers found that the participation of White and Hispanic people in IBD trials had not changed much, whereas the participation of Black people had declined, and the participation of Asian and Native American people had increased.

On the basis of work of other researchers, Dr. Peraza said that people of color are as willing to participate in trials as White people. “There is not so much a mistrust as a lack of education and a lack of access to the tertiary centers or the centers where these studies are conducted,” she said.

Clinical trial investigators should recruit more participants from community centers, and health care practitioners should talk about the trials with people in underrepresented groups, she said. “They should have the conversation with their patients about how these clinical trials can benefit the evolution of their diseases.”

One research center that is working hard to diversify its IBD trials is the Ohio State University IBD Center, Columbus, said Anita Afzali, MD, its medical director.

“We have a great team that works actively on the recruitment of all patients,” she said in an interview. “Oftentimes, it just takes a little bit of education and spending time with the patient on discussing what the options are for them.”

Some research indicates that Black people with IBD are more likely to have fistulizing disease, Dr. Afzali said. “However, it doesn’t come so much of their differences in phenotype that we’re seeing but more so the differences in access to care and getting the appropriate therapy in a timely way.”

Dr. Peraza and Dr. Afzali disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AGA applauds researchers who are working to raise our awareness of health disparities in digestive diseases. AGA is committed to addressing this important societal issue head on. Learn more about AGA’s commitment through the AGA Equity Project.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LAS VEGAS – Clinical trials of treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have disproportionately enrolled White people, researchers say.

These skewed demographics could result in researchers overlooking differences in how the disease and its treatments might affect other racial and ethnic groups, said Jellyana Peraza, MD, a chief resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

“The only way we can determine that therapies work differently in different populations is by including those populations in these clinical trials,” she said in an interview. “We think that diversity should be present, and that will answer some questions about the pathogenesis of the disease in general.”

Dr. Peraza presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Previous studies have found that, in trials of other conditions, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, White people have been disproportionately represented. However, little research has been conducted regarding race and ethnicity in IBD trials.

To fill that gap, Dr. Peraza and colleagues analyzed data from completed trials through the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, for the period from 2000 to 2020.

They found 22 trials conducted exclusively in the United States and 56 conducted in other countries that reported the race or ethnicity of participants; 54 trials did not include this information.

With regard to the prevalence of IBD in White people and Asian people, these populations were overrepresented in U.S. clinical trials. All other groups were underrepresented.

The researchers calculated the odds ratio of being included in an IBD clinical trial for each group. Compared with White people, all the other groups were less likely to be included except for Asian people, who were 85% more likely to be included. These ORs were all statistically significant (P < .03) except for Hispanic people (OR, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.01; P = .06).

It’s not clear why Asian people are overrepresented, Dr. Peraza said. “Honestly, that was kind of surprising for us. We initially thought that could be related to where these studies were conducted, for example, if some of them were conducted on the West Coast, where maybe more Asian communities are located. However, we didn’t find any specific association between location and Asian representation.”

IBD is more prevalent among White people, although its prevalence is increasing among other groups, Dr. Peraza said. However, that is not reflected in the trials. In an analysis of data in 5-year increments, the researchers found that the participation of White and Hispanic people in IBD trials had not changed much, whereas the participation of Black people had declined, and the participation of Asian and Native American people had increased.

On the basis of work of other researchers, Dr. Peraza said that people of color are as willing to participate in trials as White people. “There is not so much a mistrust as a lack of education and a lack of access to the tertiary centers or the centers where these studies are conducted,” she said.

Clinical trial investigators should recruit more participants from community centers, and health care practitioners should talk about the trials with people in underrepresented groups, she said. “They should have the conversation with their patients about how these clinical trials can benefit the evolution of their diseases.”

One research center that is working hard to diversify its IBD trials is the Ohio State University IBD Center, Columbus, said Anita Afzali, MD, its medical director.

“We have a great team that works actively on the recruitment of all patients,” she said in an interview. “Oftentimes, it just takes a little bit of education and spending time with the patient on discussing what the options are for them.”

Some research indicates that Black people with IBD are more likely to have fistulizing disease, Dr. Afzali said. “However, it doesn’t come so much of their differences in phenotype that we’re seeing but more so the differences in access to care and getting the appropriate therapy in a timely way.”

Dr. Peraza and Dr. Afzali disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AGA applauds researchers who are working to raise our awareness of health disparities in digestive diseases. AGA is committed to addressing this important societal issue head on. Learn more about AGA’s commitment through the AGA Equity Project.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACG 2021

Spin doctors

The 1992 presidential election fell during my last year of medical school. I remember watching the three-way debates over at a friend’s apartment.

After each one they’d cut to representatives of each candidate, and for the first time I heard the phrase “spin” or “spin doctors” referring to those who put a very selective angle on their candidates performance, no matter how bad it may have been, to make it sound like something amazingly awesome. This trend, driven now by the Internet and the 24/7 news cycle, has only accelerated over time.

Recently, I’ve been reading slides, press releases, and preliminary reports for the many agents that are seeking to cure Alzheimer’s disease. A desperately needed effort if ever there was one.

Yet, I get the same feeling I did in 1992. It seems like a lot of the statements are more selective than real: a carefully worded attempt to emphasize the good points and minimize the bad. Granted that’s the nature of many things, but here, in a world of a few percentage points, it seems more conspicuous than usual.

After all, even a non–statistically significant improvement of 1%-2% can look really good if you use the right graph style or comparison scale.

When I read such articles now, I find myself wondering if the drug really works or if the spin doctors have gotten so good at making even the most minuscule numbers look impressive that I can’t tell the difference. In theory many of these drugs should work, but, in Alzheimer’s disease “should” and “does” haven’t matched up particularly well to date.

To be clear, I’m not cheering for these drugs to fail. On the contrary, if one showed overwhelming evidence of benefit (as opposed to having to be spun to look good), I’d be thrilled. Along with the patients and their support circles, it’s their doctors who watch the sad downhill slide of dementia, with the patients dying long before their bodies do. I would be thrilled to be able to offer them something that had clearly meaningful benefit with a decent safety profile.

But, barring more solid data,

I hope I’m wrong.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The 1992 presidential election fell during my last year of medical school. I remember watching the three-way debates over at a friend’s apartment.

After each one they’d cut to representatives of each candidate, and for the first time I heard the phrase “spin” or “spin doctors” referring to those who put a very selective angle on their candidates performance, no matter how bad it may have been, to make it sound like something amazingly awesome. This trend, driven now by the Internet and the 24/7 news cycle, has only accelerated over time.

Recently, I’ve been reading slides, press releases, and preliminary reports for the many agents that are seeking to cure Alzheimer’s disease. A desperately needed effort if ever there was one.

Yet, I get the same feeling I did in 1992. It seems like a lot of the statements are more selective than real: a carefully worded attempt to emphasize the good points and minimize the bad. Granted that’s the nature of many things, but here, in a world of a few percentage points, it seems more conspicuous than usual.

After all, even a non–statistically significant improvement of 1%-2% can look really good if you use the right graph style or comparison scale.

When I read such articles now, I find myself wondering if the drug really works or if the spin doctors have gotten so good at making even the most minuscule numbers look impressive that I can’t tell the difference. In theory many of these drugs should work, but, in Alzheimer’s disease “should” and “does” haven’t matched up particularly well to date.

To be clear, I’m not cheering for these drugs to fail. On the contrary, if one showed overwhelming evidence of benefit (as opposed to having to be spun to look good), I’d be thrilled. Along with the patients and their support circles, it’s their doctors who watch the sad downhill slide of dementia, with the patients dying long before their bodies do. I would be thrilled to be able to offer them something that had clearly meaningful benefit with a decent safety profile.

But, barring more solid data,

I hope I’m wrong.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The 1992 presidential election fell during my last year of medical school. I remember watching the three-way debates over at a friend’s apartment.

After each one they’d cut to representatives of each candidate, and for the first time I heard the phrase “spin” or “spin doctors” referring to those who put a very selective angle on their candidates performance, no matter how bad it may have been, to make it sound like something amazingly awesome. This trend, driven now by the Internet and the 24/7 news cycle, has only accelerated over time.

Recently, I’ve been reading slides, press releases, and preliminary reports for the many agents that are seeking to cure Alzheimer’s disease. A desperately needed effort if ever there was one.

Yet, I get the same feeling I did in 1992. It seems like a lot of the statements are more selective than real: a carefully worded attempt to emphasize the good points and minimize the bad. Granted that’s the nature of many things, but here, in a world of a few percentage points, it seems more conspicuous than usual.

After all, even a non–statistically significant improvement of 1%-2% can look really good if you use the right graph style or comparison scale.

When I read such articles now, I find myself wondering if the drug really works or if the spin doctors have gotten so good at making even the most minuscule numbers look impressive that I can’t tell the difference. In theory many of these drugs should work, but, in Alzheimer’s disease “should” and “does” haven’t matched up particularly well to date.

To be clear, I’m not cheering for these drugs to fail. On the contrary, if one showed overwhelming evidence of benefit (as opposed to having to be spun to look good), I’d be thrilled. Along with the patients and their support circles, it’s their doctors who watch the sad downhill slide of dementia, with the patients dying long before their bodies do. I would be thrilled to be able to offer them something that had clearly meaningful benefit with a decent safety profile.

But, barring more solid data,

I hope I’m wrong.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The third generation of therapeutic innovation and the future of psychopharmacology

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

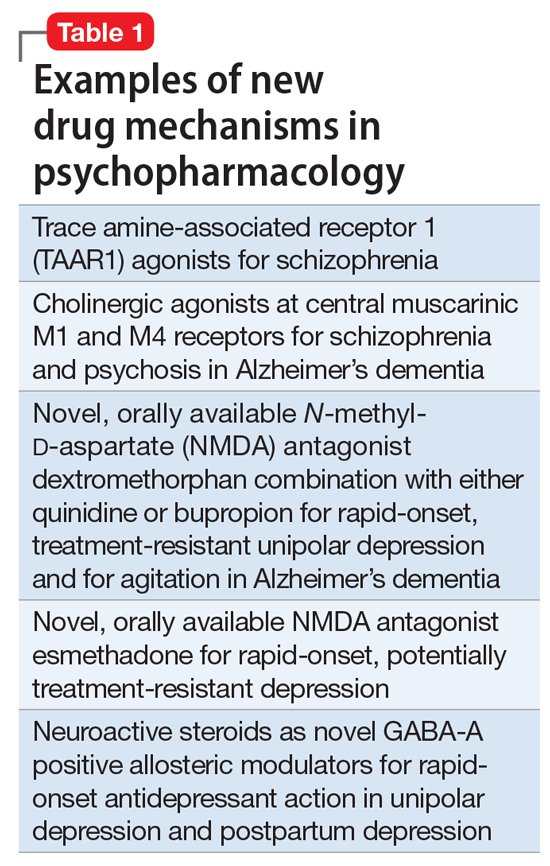

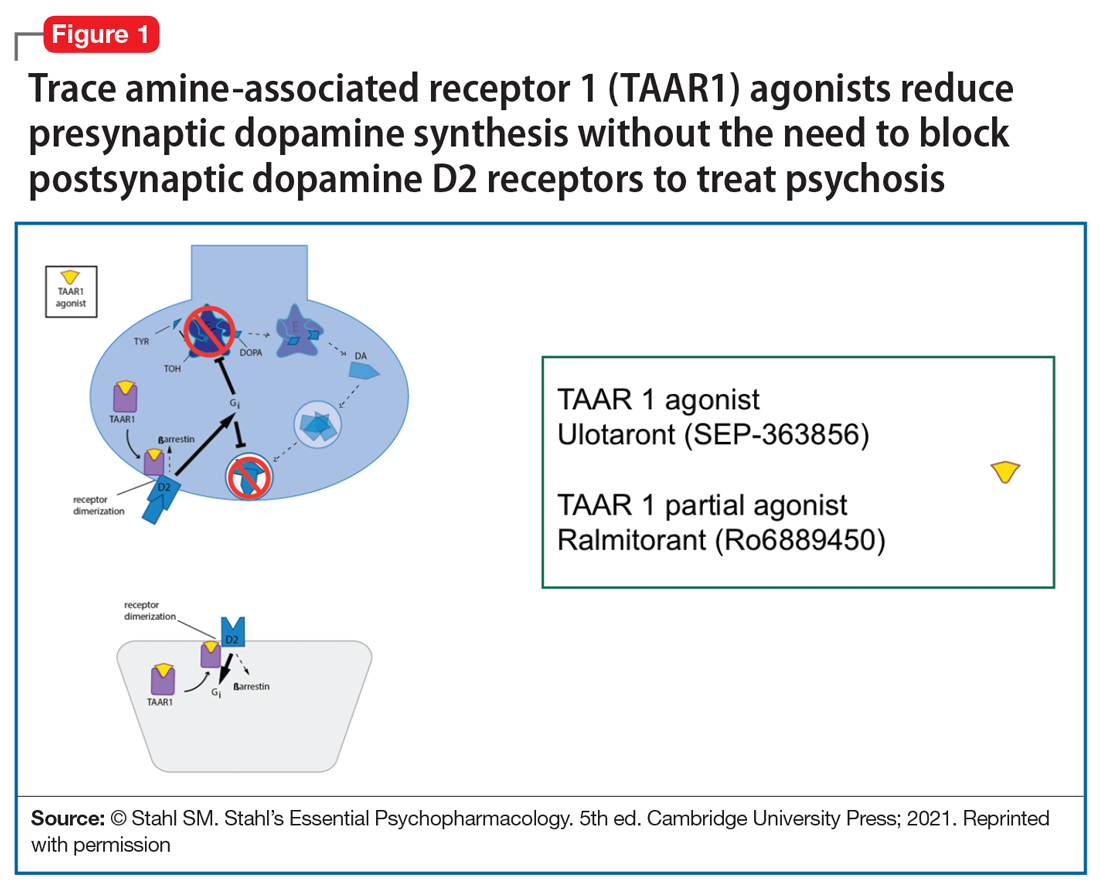

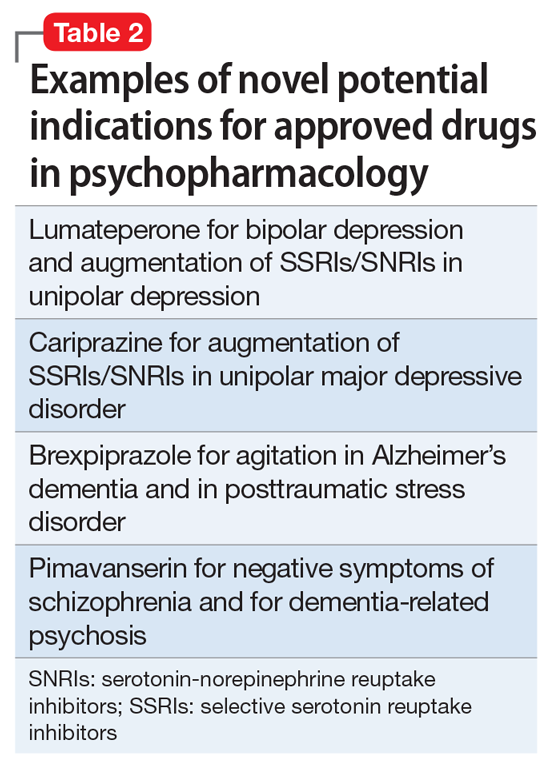

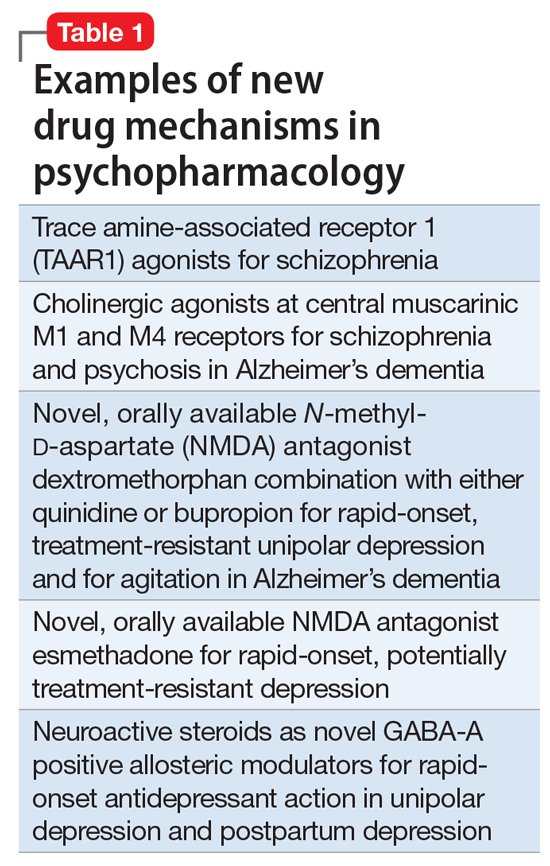

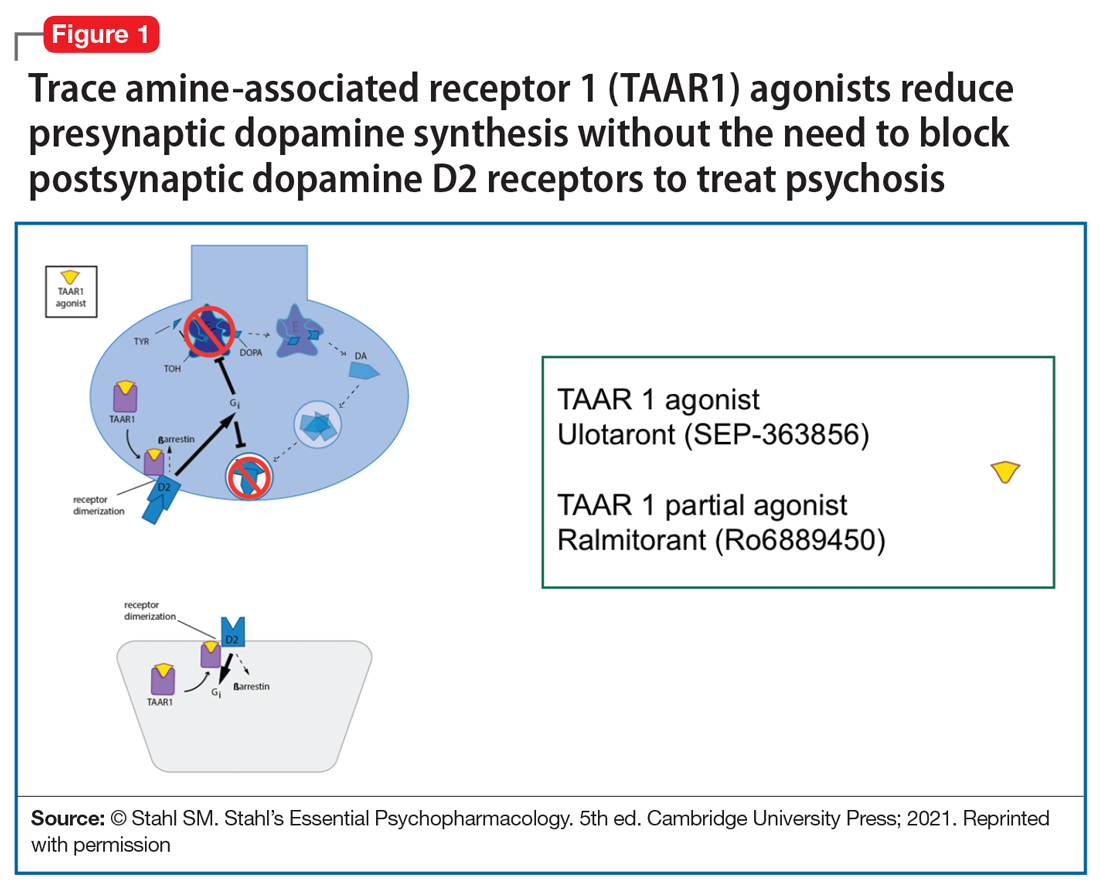

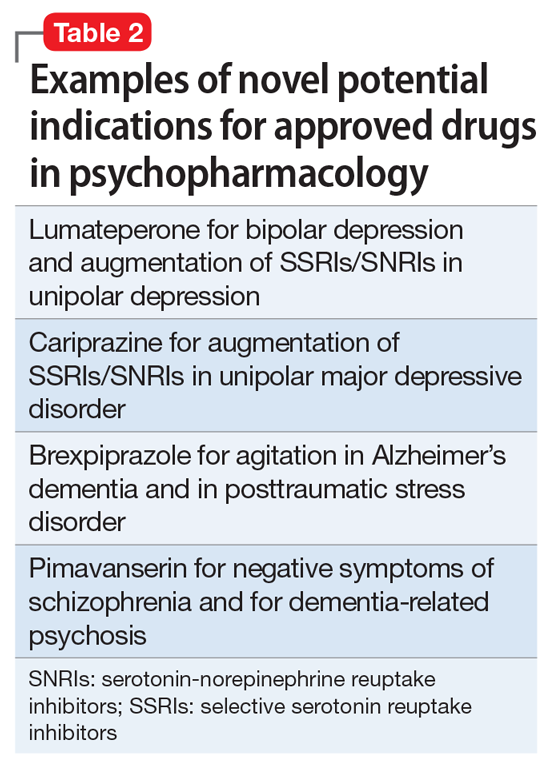

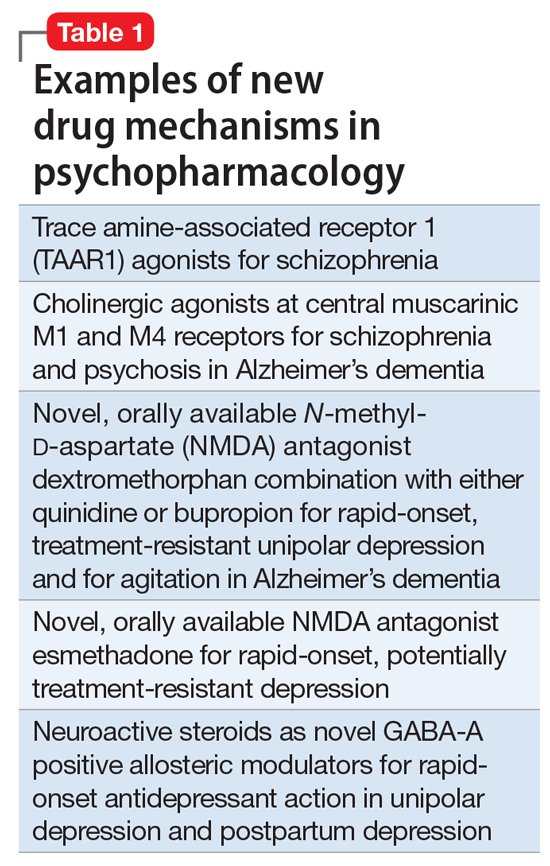

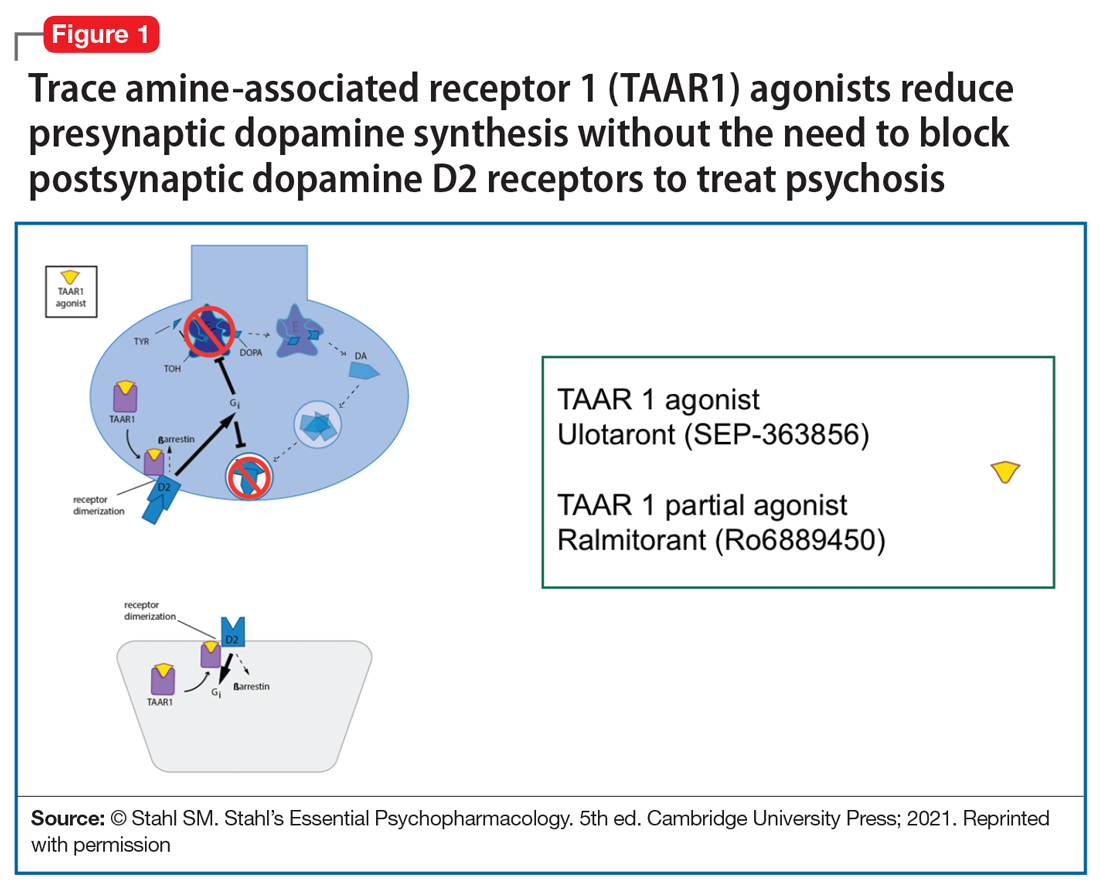

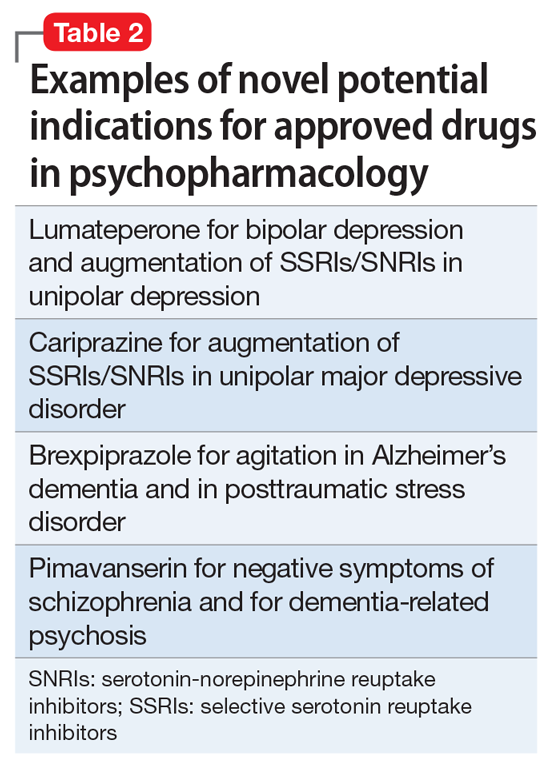

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

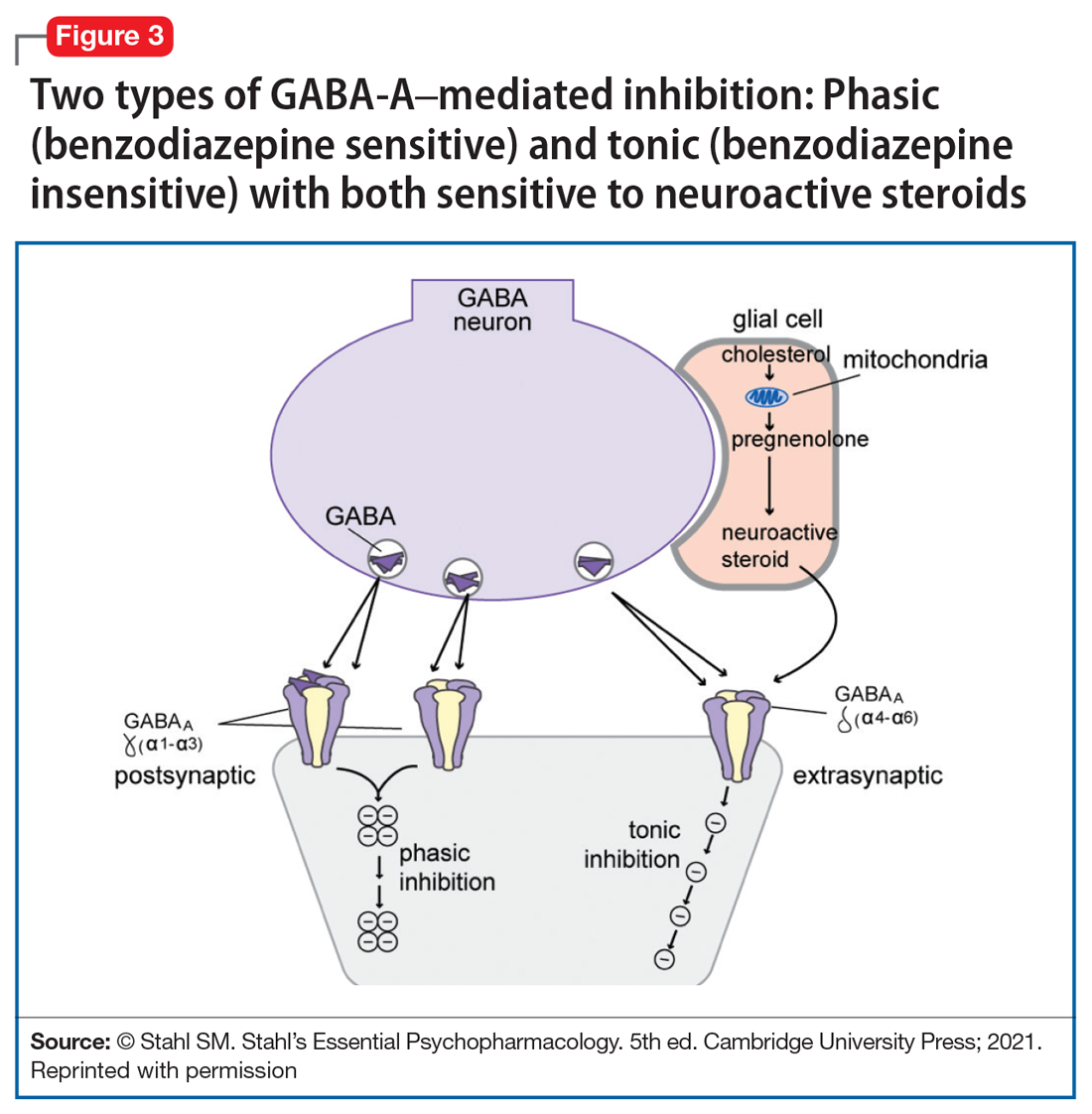

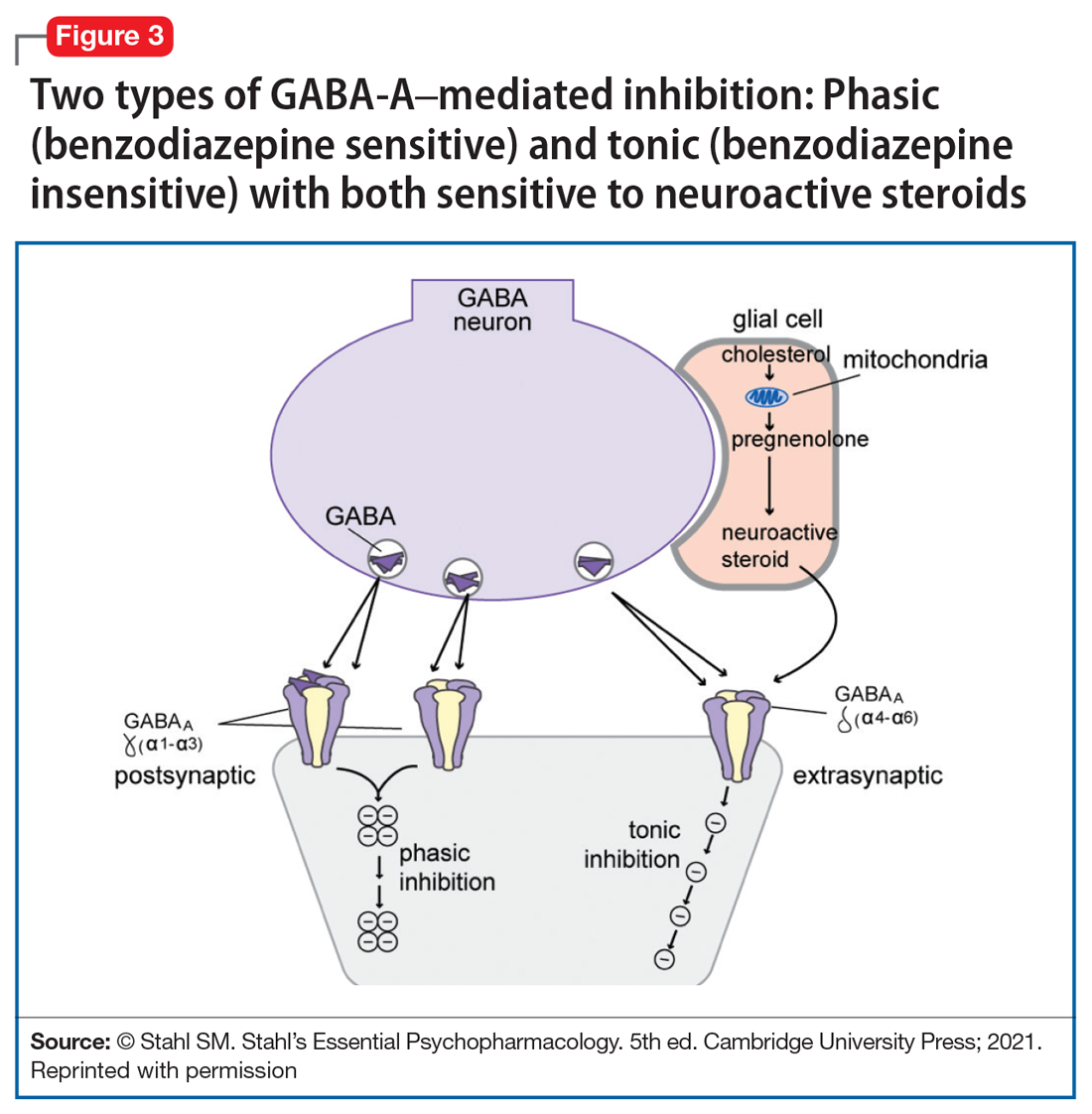

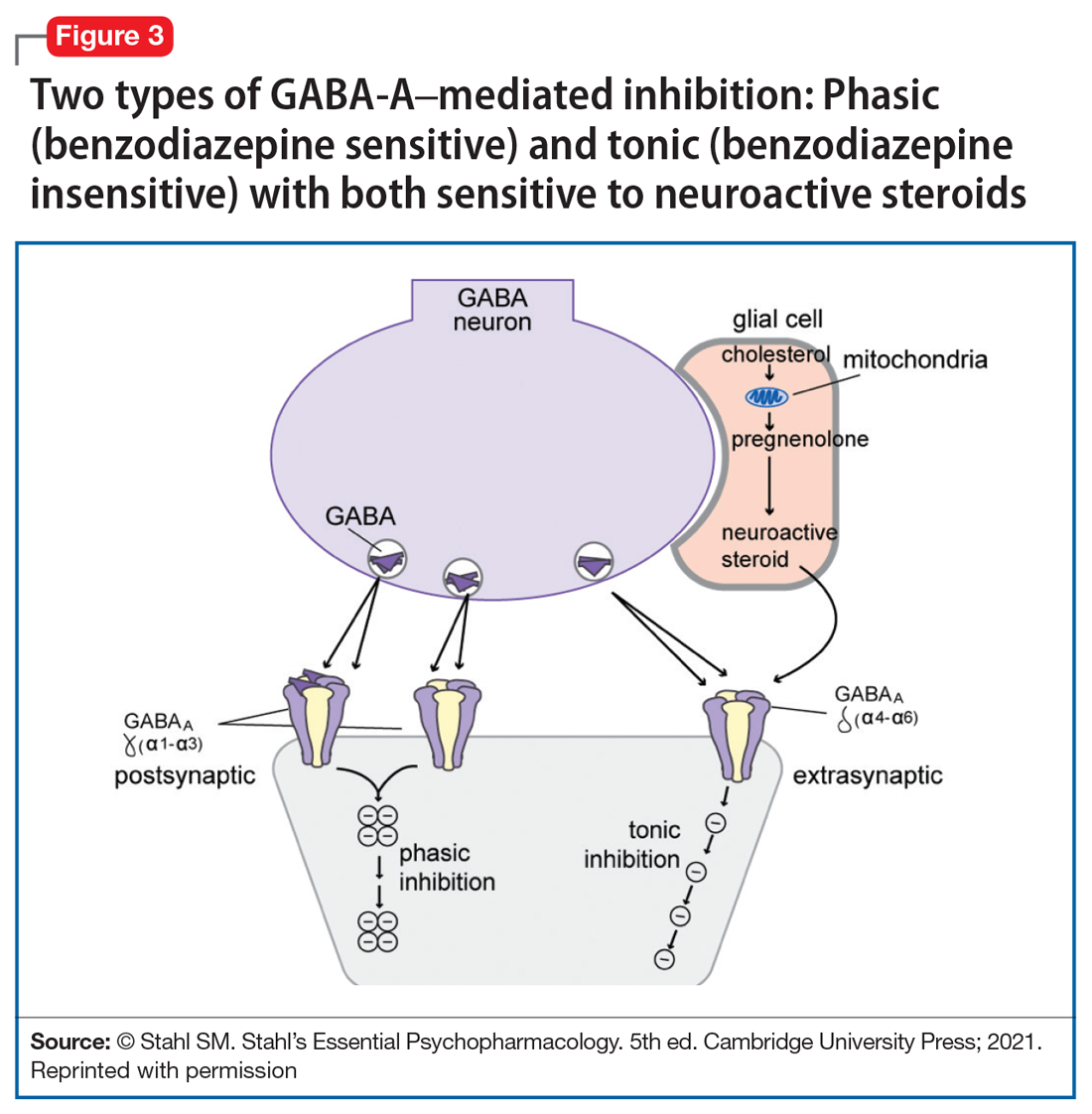

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

Congress OKs Veterans Affairs Expansive New Maternal Care Program

It’s called the Momnibus—the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 (HR 959) with 12 bills addressing “every dimension of the maternal health crisis in America.” The first bill in the Momnibus to pass Congress is the Protecting Moms Who Served act, which sets up a $15 million maternal care program within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). “There has never been a comprehensive evaluation of how our nation’s growing maternal mortality crisis is impacting our women veterans, even though they may be at higher risk due to their service,” said Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL), a co-sponsor of the Momnibus. The bill has passed Congress and awaits President Biden’s signature.

Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-IL) along with Rep. Alma Adams (D- NC-12), Sen. Cory Booker D-NJ), and members of the Black Maternal Health Caucus reintroduced the bill (first introduced last year). According to Rep. Underwood, the act would codify and strengthen the VA maternity care coordination programs. It also will require the US Government Accountability Office to report the deaths of pregnant and postpartum veterans and to focus on any racial or ethnic disparities. The bill passed overwhelmingly, 414 to 9 and awaits President Biden’s signature.

The Momnibus’s cute name represents a very serious purpose. “Maternal mortality has historically been used as a key indicator of the health of a population,” say researchers from National Vital Statistics Reports. But American mothers are dying at the highest rate in the developed world, and the numbers have been rising dramatically. Between 1987, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System in 2017, the latest year for available data, the number of reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States rose steadily from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births to 17.3 per 100,000.

The maternal morbidity crisis is particularly stark among certain groups of women. Black women are acutely at risk, dying at 3 to 4 times the rate of White women (41.7 deaths per 100,000 live births), and one-third higher than the next highest risk group, Native American women (28.3 deaths per 100,000 live births).

But just how accurate have the data been? The study published in National Vital Statistics Report found that using a checkbox for “cause of death” specifying maternal death identified more than triple the number of maternal deaths. Without the checkbox item, maternal mortality rates in 2015 and 2016 would have been reported as 8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with 8.9 in 2002. With the checkbox, the rate would be reported as 20.9 per 100,000 live births in 2015 and 21.8/100,000 in 2016.

The CDC states that the reasons for the rising numbers are unclear; advances in identification have improved over time, for one. But by and large, the women are dying of preventable causes, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic heart disease. Nearly 60% of maternal deaths are deemed preventable.

Black and other minority women, though, may be dying of biases. Researchers from Beth Israel and Harvard cite studies that have found racial and ethnic disparities in obstetric care delivery. Non-Hispanic Blacks women, Hispanic women, and Asian women, for instance, have lower odds of labor induction when compared with that of White women. The odds of receiving an episiotomy are lower in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women. The Listening to Mothers survey III found that 24% of participants perceived discrimination during birth hospitalization, predominantly among Black or Hispanic women and uninsured women.

A maternal health equity advocacy group, 4Kira4Moms, was founded by the husband of Kira Johnson who died of hemorrhage following a routine scheduled cesarean section. In the recovery room, her catheter began turning pink with blood. For 10 hours, her husband said, he and her family begged the medical staff for help but were told his wife was not a priority. Thus, the Momnibus also contains the Kira Johnson Act, which will establish funding for community-based groups to provide Black pregnant women with more support.

Among other changes, the Momnibus will:

- Make critical investments in social determinants of health that influence maternal health outcomes, such as housing, transportation, and nutrition;

- Provide funding to community-based organizations that are working to improve maternal health outcomes and promote equity;

- Comprehensively study the unique maternal health risks facing pregnant and postpartum veterans and support VA maternity care coordination programs;

- Support mothers with mental health conditions and substance use disorders; and

- Promote innovative payment models to incentivize high-quality maternity care and nonclinical perinatal support

A variety of recent bills in Congress address maternal health. The Mothers and Offspring Mortality and Morbidity Awareness (MOMMA) Act, for instance, also would specifically address maternal health disparities by improving data collection and reporting, improving maternal care, and advancing respectful, equitable care. It also would extend Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage. Katie Shea Barrett, MPH, executive director of March for Moms, a coalition of families, health care practitioners, policy makers, and partners advocating for mothers’ and families’ health, notes in an essay for thehill.com that Medicaid coverage ends about 60 days postpartum, although half of the maternal deaths happen between 42 days and 1 year postpartum.

She writes: “[W]e have to directly address the disproportionate impact of maternal mortality on women of color by training providers in offering care that is culturally competent and free of implicit bias. Health systems must be aware and respectful of cultural norms when providing care and be mindful of buying into stereotypes based on race, ethnicity, and even underlying medical conditions like diabetes, which often lead to perceived discrimination and perpetuate systems of injustice.”

In April, Vice President Kamala Harris called for sweeping action to curb racial inequities in pregnancy and childbirth. In an email Q&A with STAT, she said, “With every day that goes by and every woman who dies, the need for action grows more urgent.”

It’s called the Momnibus—the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 (HR 959) with 12 bills addressing “every dimension of the maternal health crisis in America.” The first bill in the Momnibus to pass Congress is the Protecting Moms Who Served act, which sets up a $15 million maternal care program within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). “There has never been a comprehensive evaluation of how our nation’s growing maternal mortality crisis is impacting our women veterans, even though they may be at higher risk due to their service,” said Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL), a co-sponsor of the Momnibus. The bill has passed Congress and awaits President Biden’s signature.

Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-IL) along with Rep. Alma Adams (D- NC-12), Sen. Cory Booker D-NJ), and members of the Black Maternal Health Caucus reintroduced the bill (first introduced last year). According to Rep. Underwood, the act would codify and strengthen the VA maternity care coordination programs. It also will require the US Government Accountability Office to report the deaths of pregnant and postpartum veterans and to focus on any racial or ethnic disparities. The bill passed overwhelmingly, 414 to 9 and awaits President Biden’s signature.

The Momnibus’s cute name represents a very serious purpose. “Maternal mortality has historically been used as a key indicator of the health of a population,” say researchers from National Vital Statistics Reports. But American mothers are dying at the highest rate in the developed world, and the numbers have been rising dramatically. Between 1987, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System in 2017, the latest year for available data, the number of reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States rose steadily from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births to 17.3 per 100,000.

The maternal morbidity crisis is particularly stark among certain groups of women. Black women are acutely at risk, dying at 3 to 4 times the rate of White women (41.7 deaths per 100,000 live births), and one-third higher than the next highest risk group, Native American women (28.3 deaths per 100,000 live births).

But just how accurate have the data been? The study published in National Vital Statistics Report found that using a checkbox for “cause of death” specifying maternal death identified more than triple the number of maternal deaths. Without the checkbox item, maternal mortality rates in 2015 and 2016 would have been reported as 8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with 8.9 in 2002. With the checkbox, the rate would be reported as 20.9 per 100,000 live births in 2015 and 21.8/100,000 in 2016.

The CDC states that the reasons for the rising numbers are unclear; advances in identification have improved over time, for one. But by and large, the women are dying of preventable causes, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic heart disease. Nearly 60% of maternal deaths are deemed preventable.

Black and other minority women, though, may be dying of biases. Researchers from Beth Israel and Harvard cite studies that have found racial and ethnic disparities in obstetric care delivery. Non-Hispanic Blacks women, Hispanic women, and Asian women, for instance, have lower odds of labor induction when compared with that of White women. The odds of receiving an episiotomy are lower in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women. The Listening to Mothers survey III found that 24% of participants perceived discrimination during birth hospitalization, predominantly among Black or Hispanic women and uninsured women.

A maternal health equity advocacy group, 4Kira4Moms, was founded by the husband of Kira Johnson who died of hemorrhage following a routine scheduled cesarean section. In the recovery room, her catheter began turning pink with blood. For 10 hours, her husband said, he and her family begged the medical staff for help but were told his wife was not a priority. Thus, the Momnibus also contains the Kira Johnson Act, which will establish funding for community-based groups to provide Black pregnant women with more support.

Among other changes, the Momnibus will:

- Make critical investments in social determinants of health that influence maternal health outcomes, such as housing, transportation, and nutrition;

- Provide funding to community-based organizations that are working to improve maternal health outcomes and promote equity;

- Comprehensively study the unique maternal health risks facing pregnant and postpartum veterans and support VA maternity care coordination programs;

- Support mothers with mental health conditions and substance use disorders; and

- Promote innovative payment models to incentivize high-quality maternity care and nonclinical perinatal support

A variety of recent bills in Congress address maternal health. The Mothers and Offspring Mortality and Morbidity Awareness (MOMMA) Act, for instance, also would specifically address maternal health disparities by improving data collection and reporting, improving maternal care, and advancing respectful, equitable care. It also would extend Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage. Katie Shea Barrett, MPH, executive director of March for Moms, a coalition of families, health care practitioners, policy makers, and partners advocating for mothers’ and families’ health, notes in an essay for thehill.com that Medicaid coverage ends about 60 days postpartum, although half of the maternal deaths happen between 42 days and 1 year postpartum.

She writes: “[W]e have to directly address the disproportionate impact of maternal mortality on women of color by training providers in offering care that is culturally competent and free of implicit bias. Health systems must be aware and respectful of cultural norms when providing care and be mindful of buying into stereotypes based on race, ethnicity, and even underlying medical conditions like diabetes, which often lead to perceived discrimination and perpetuate systems of injustice.”

In April, Vice President Kamala Harris called for sweeping action to curb racial inequities in pregnancy and childbirth. In an email Q&A with STAT, she said, “With every day that goes by and every woman who dies, the need for action grows more urgent.”

It’s called the Momnibus—the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 (HR 959) with 12 bills addressing “every dimension of the maternal health crisis in America.” The first bill in the Momnibus to pass Congress is the Protecting Moms Who Served act, which sets up a $15 million maternal care program within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). “There has never been a comprehensive evaluation of how our nation’s growing maternal mortality crisis is impacting our women veterans, even though they may be at higher risk due to their service,” said Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL), a co-sponsor of the Momnibus. The bill has passed Congress and awaits President Biden’s signature.