User login

Standing up to ‘injustice in health’: The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.” – Martin Luther King Jr., March 25, 1966. 1

This single disparity – health care injustice – too often results in needless mental anguish, physical suffering, or death. In the spring of 2020, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the convergence of injustices in health care and policing led to the disproportionate preventable physical deaths of Black men and women. This became the watershed moment for 11 gastroenterologists and hepatologists who collectively grieved but heeded the call of social responsibility to form the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists.

The mission of ABGH is laser focused. It is to promote health equity in Black communities, advance science, and develop the careers of Black gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and scientists. The vision is to improve gastrointestinal health outcomes in Black communities; to develop the pipeline of Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists given that currently only 4% in the United States identify as Black; to foster networking, mentoring, and sponsorship among Black students, clinical trainees, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists; and to promote the scholarship of Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists.

Through community engagement, ABGH stands to empower the Black community with knowledge and choices, which inherently strengthens the physician-patient relationship. ABGH also exists to implement positive change in long term outcome statistics in Black communities. Black Americans are 20% more likely to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 40% more likely to die from the disease. In addition to colorectal cancer, rates of esophageal squamous cancer, as well as cancer of the small bowel and pancreas, are highest in Black people.2 Through scientific research and clinical care, we aim to eradicate digestive health disparities.

Yet in this space, we know first-hand that, in the United States, the wellness of a community is not measured by the medical fitness of its members alone but also by the availability of equitable opportunities for fulfillment of nonmedical but health-impacting social needs. These needs, also known as social determinants of health, are made inaccessible to vulnerable populations because of systemic racism. Importantly, we recognize that dismantling racist systems is not a singular effort, nor are we pioneers in this work, but we look forward to executing health equity goals collaboratively with our fellow gastrointestinal national societies and other leading community and grassroots organizations.

The founders of ABGH are a distinctive group of practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists from across the United States with a strong track record in DEI work through their community, clinical, and research activities. The board of directors reflects only the depth of talent shared throughout the ABGH membership. The strength of the organization lies in its diverse and energetic constituents who all exemplify outstanding training and the readiness to redefine the standard of health care delivery to the Black community. From medical students to senior level gastroenterologists, we collectively embody a considerable momentum for formation of this organization at this point in our history.

ABGH fulfills a professional career development need for budding gastroenterologists not so readily available from other organizations. The compelling impact of representing the embodiment of what many of us were told we could not become is limitless. The personal and professional growth enabled by our networking and learning from each other is both motivating and empowering since, even after overcoming the obstacles needed to become a medical provider, Black professionals are often not afforded the bandwidth, range of emotion, and protection to reveal their specific needs. For this author personally, the ABGH provides a psychological safety that allows authentic self-identity without code-switching.3 Through this authenticity has arisen formidable strength, creativity, and productivity. The leadership and innovation cultivated in ABGH stands to benefit many generations to come, both within and outside the organization.

Reflections from a junior member of ABGH: Dr. Kafayat Busari

My desire to pursue gastroenterology was bolstered by determination, curiosity, and passion, yet ironically was often met with skepticism by many in position to help advance this goal. Although projections of incertitude on members of a community that are often made to feel inadequate can diminish even the brightest of lights, conversely it can fuel the creation of an organization emboldened to specifically address GI-related health disparities. When I was a second-year internal medicine resident, I encountered a GI physician who told me GI “wasn’t something I wanted to do”—despite me expressing my interest.

Confused by the statement, I reached out to Renee L. Williams, MD, of NYU Langone Health, who I had met during my medical school training. She suggested I join a conference call later that week. On that call and the many that took place thereafter, I was introduced to Black gastroenterologists who are luminal disease experts, chair members, journal editors, transplant hepatologists, interventional endoscopists, researchers, and professors (in other words, GI professional leaders). My time on the initial call lasted perhaps less than 20 minutes, but the impact has been immeasurable.

I was provided the emotional reassurance that GI was indeed for me and told “there’s always a seat, and if it feels like there’s not, we just need to get more chairs.” Little did I know, but those metaphorical chairs were being gathered so that I and other aspiring gastroenterologists will be able to sit comfortably at these tables one day. I was witnessing these GI professional leaders set in motion the beginning of what will undoubtedly be a pivotal component in the way I approach my career as a gastroenterologist. The experience reignited my mental determination to one day attain the level of success represented by the ABGH board members and to persevere in my quest to help redefine how Black medical students and residents serve their communities as physicians.

The creation of the ABGH could not have come at a better time in my training. In the wake of recent public protests for equity of African Americans within every institution (academia, housing, banks, policing, health care, and beyond), which were fundamentally built on racism, being a junior member of ABGH has not only given me a platform to speak my truth but has also provided me with tools to help others do so as well. As someone very passionate about research, primarily in colorectal cancer, I have been given an opportunity to connect with a dream team of mentors who have taken research ideas to new levels and have challenged me to dig deeper and expand my curiosity to investigate what still needs to be uncovered. It has created opportunity after opportunity for actively building relationships, leading to meaningful collaborations and the sharing of innovative ideas and discoveries.

It is important to emphasize that ABGH is not an organization wanting to exclude themselves on the basis of ethnicity. ABGH is an example of how shared health goals within a medical discipline can be achieved when inclusion and equity is at the helm. ABGH led and represented events that raise awareness of diseases affecting all patients and aim to make the GI community more culturally competent. ABGH is future-oriented and embraces all members who align with the mission regardless of ethnicity, gender, orientation, or disability. The institution that is and will be the ABGH impresses upon me a feeling of excitement, gratitude, and humility. I look forward to continuing the mission created by the founding members and being to others what ABGH is to me.

For more information on this organization, please visit blackingastro.org.

Dr. Busari is a resident physician at Florida State University-SMH and a junior member of ABGH. Dr. Guillaume director of the Gastrointestinal Motility Center at Stony Brook (New York) University Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. They have no disclosures.

References

1. Galarneau C. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):5-8.

2. Ashktorab H et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Oct;153(4):910-923.

3. Blanchard AK. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun 10;384(23):e87.

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.” – Martin Luther King Jr., March 25, 1966. 1

This single disparity – health care injustice – too often results in needless mental anguish, physical suffering, or death. In the spring of 2020, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the convergence of injustices in health care and policing led to the disproportionate preventable physical deaths of Black men and women. This became the watershed moment for 11 gastroenterologists and hepatologists who collectively grieved but heeded the call of social responsibility to form the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists.

The mission of ABGH is laser focused. It is to promote health equity in Black communities, advance science, and develop the careers of Black gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and scientists. The vision is to improve gastrointestinal health outcomes in Black communities; to develop the pipeline of Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists given that currently only 4% in the United States identify as Black; to foster networking, mentoring, and sponsorship among Black students, clinical trainees, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists; and to promote the scholarship of Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists.

Through community engagement, ABGH stands to empower the Black community with knowledge and choices, which inherently strengthens the physician-patient relationship. ABGH also exists to implement positive change in long term outcome statistics in Black communities. Black Americans are 20% more likely to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 40% more likely to die from the disease. In addition to colorectal cancer, rates of esophageal squamous cancer, as well as cancer of the small bowel and pancreas, are highest in Black people.2 Through scientific research and clinical care, we aim to eradicate digestive health disparities.

Yet in this space, we know first-hand that, in the United States, the wellness of a community is not measured by the medical fitness of its members alone but also by the availability of equitable opportunities for fulfillment of nonmedical but health-impacting social needs. These needs, also known as social determinants of health, are made inaccessible to vulnerable populations because of systemic racism. Importantly, we recognize that dismantling racist systems is not a singular effort, nor are we pioneers in this work, but we look forward to executing health equity goals collaboratively with our fellow gastrointestinal national societies and other leading community and grassroots organizations.

The founders of ABGH are a distinctive group of practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists from across the United States with a strong track record in DEI work through their community, clinical, and research activities. The board of directors reflects only the depth of talent shared throughout the ABGH membership. The strength of the organization lies in its diverse and energetic constituents who all exemplify outstanding training and the readiness to redefine the standard of health care delivery to the Black community. From medical students to senior level gastroenterologists, we collectively embody a considerable momentum for formation of this organization at this point in our history.

ABGH fulfills a professional career development need for budding gastroenterologists not so readily available from other organizations. The compelling impact of representing the embodiment of what many of us were told we could not become is limitless. The personal and professional growth enabled by our networking and learning from each other is both motivating and empowering since, even after overcoming the obstacles needed to become a medical provider, Black professionals are often not afforded the bandwidth, range of emotion, and protection to reveal their specific needs. For this author personally, the ABGH provides a psychological safety that allows authentic self-identity without code-switching.3 Through this authenticity has arisen formidable strength, creativity, and productivity. The leadership and innovation cultivated in ABGH stands to benefit many generations to come, both within and outside the organization.

Reflections from a junior member of ABGH: Dr. Kafayat Busari

My desire to pursue gastroenterology was bolstered by determination, curiosity, and passion, yet ironically was often met with skepticism by many in position to help advance this goal. Although projections of incertitude on members of a community that are often made to feel inadequate can diminish even the brightest of lights, conversely it can fuel the creation of an organization emboldened to specifically address GI-related health disparities. When I was a second-year internal medicine resident, I encountered a GI physician who told me GI “wasn’t something I wanted to do”—despite me expressing my interest.

Confused by the statement, I reached out to Renee L. Williams, MD, of NYU Langone Health, who I had met during my medical school training. She suggested I join a conference call later that week. On that call and the many that took place thereafter, I was introduced to Black gastroenterologists who are luminal disease experts, chair members, journal editors, transplant hepatologists, interventional endoscopists, researchers, and professors (in other words, GI professional leaders). My time on the initial call lasted perhaps less than 20 minutes, but the impact has been immeasurable.

I was provided the emotional reassurance that GI was indeed for me and told “there’s always a seat, and if it feels like there’s not, we just need to get more chairs.” Little did I know, but those metaphorical chairs were being gathered so that I and other aspiring gastroenterologists will be able to sit comfortably at these tables one day. I was witnessing these GI professional leaders set in motion the beginning of what will undoubtedly be a pivotal component in the way I approach my career as a gastroenterologist. The experience reignited my mental determination to one day attain the level of success represented by the ABGH board members and to persevere in my quest to help redefine how Black medical students and residents serve their communities as physicians.

The creation of the ABGH could not have come at a better time in my training. In the wake of recent public protests for equity of African Americans within every institution (academia, housing, banks, policing, health care, and beyond), which were fundamentally built on racism, being a junior member of ABGH has not only given me a platform to speak my truth but has also provided me with tools to help others do so as well. As someone very passionate about research, primarily in colorectal cancer, I have been given an opportunity to connect with a dream team of mentors who have taken research ideas to new levels and have challenged me to dig deeper and expand my curiosity to investigate what still needs to be uncovered. It has created opportunity after opportunity for actively building relationships, leading to meaningful collaborations and the sharing of innovative ideas and discoveries.

It is important to emphasize that ABGH is not an organization wanting to exclude themselves on the basis of ethnicity. ABGH is an example of how shared health goals within a medical discipline can be achieved when inclusion and equity is at the helm. ABGH led and represented events that raise awareness of diseases affecting all patients and aim to make the GI community more culturally competent. ABGH is future-oriented and embraces all members who align with the mission regardless of ethnicity, gender, orientation, or disability. The institution that is and will be the ABGH impresses upon me a feeling of excitement, gratitude, and humility. I look forward to continuing the mission created by the founding members and being to others what ABGH is to me.

For more information on this organization, please visit blackingastro.org.

Dr. Busari is a resident physician at Florida State University-SMH and a junior member of ABGH. Dr. Guillaume director of the Gastrointestinal Motility Center at Stony Brook (New York) University Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. They have no disclosures.

References

1. Galarneau C. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):5-8.

2. Ashktorab H et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Oct;153(4):910-923.

3. Blanchard AK. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun 10;384(23):e87.

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.” – Martin Luther King Jr., March 25, 1966. 1

This single disparity – health care injustice – too often results in needless mental anguish, physical suffering, or death. In the spring of 2020, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the convergence of injustices in health care and policing led to the disproportionate preventable physical deaths of Black men and women. This became the watershed moment for 11 gastroenterologists and hepatologists who collectively grieved but heeded the call of social responsibility to form the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists.

The mission of ABGH is laser focused. It is to promote health equity in Black communities, advance science, and develop the careers of Black gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and scientists. The vision is to improve gastrointestinal health outcomes in Black communities; to develop the pipeline of Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists given that currently only 4% in the United States identify as Black; to foster networking, mentoring, and sponsorship among Black students, clinical trainees, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists; and to promote the scholarship of Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists.

Through community engagement, ABGH stands to empower the Black community with knowledge and choices, which inherently strengthens the physician-patient relationship. ABGH also exists to implement positive change in long term outcome statistics in Black communities. Black Americans are 20% more likely to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 40% more likely to die from the disease. In addition to colorectal cancer, rates of esophageal squamous cancer, as well as cancer of the small bowel and pancreas, are highest in Black people.2 Through scientific research and clinical care, we aim to eradicate digestive health disparities.

Yet in this space, we know first-hand that, in the United States, the wellness of a community is not measured by the medical fitness of its members alone but also by the availability of equitable opportunities for fulfillment of nonmedical but health-impacting social needs. These needs, also known as social determinants of health, are made inaccessible to vulnerable populations because of systemic racism. Importantly, we recognize that dismantling racist systems is not a singular effort, nor are we pioneers in this work, but we look forward to executing health equity goals collaboratively with our fellow gastrointestinal national societies and other leading community and grassroots organizations.

The founders of ABGH are a distinctive group of practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists from across the United States with a strong track record in DEI work through their community, clinical, and research activities. The board of directors reflects only the depth of talent shared throughout the ABGH membership. The strength of the organization lies in its diverse and energetic constituents who all exemplify outstanding training and the readiness to redefine the standard of health care delivery to the Black community. From medical students to senior level gastroenterologists, we collectively embody a considerable momentum for formation of this organization at this point in our history.

ABGH fulfills a professional career development need for budding gastroenterologists not so readily available from other organizations. The compelling impact of representing the embodiment of what many of us were told we could not become is limitless. The personal and professional growth enabled by our networking and learning from each other is both motivating and empowering since, even after overcoming the obstacles needed to become a medical provider, Black professionals are often not afforded the bandwidth, range of emotion, and protection to reveal their specific needs. For this author personally, the ABGH provides a psychological safety that allows authentic self-identity without code-switching.3 Through this authenticity has arisen formidable strength, creativity, and productivity. The leadership and innovation cultivated in ABGH stands to benefit many generations to come, both within and outside the organization.

Reflections from a junior member of ABGH: Dr. Kafayat Busari

My desire to pursue gastroenterology was bolstered by determination, curiosity, and passion, yet ironically was often met with skepticism by many in position to help advance this goal. Although projections of incertitude on members of a community that are often made to feel inadequate can diminish even the brightest of lights, conversely it can fuel the creation of an organization emboldened to specifically address GI-related health disparities. When I was a second-year internal medicine resident, I encountered a GI physician who told me GI “wasn’t something I wanted to do”—despite me expressing my interest.

Confused by the statement, I reached out to Renee L. Williams, MD, of NYU Langone Health, who I had met during my medical school training. She suggested I join a conference call later that week. On that call and the many that took place thereafter, I was introduced to Black gastroenterologists who are luminal disease experts, chair members, journal editors, transplant hepatologists, interventional endoscopists, researchers, and professors (in other words, GI professional leaders). My time on the initial call lasted perhaps less than 20 minutes, but the impact has been immeasurable.

I was provided the emotional reassurance that GI was indeed for me and told “there’s always a seat, and if it feels like there’s not, we just need to get more chairs.” Little did I know, but those metaphorical chairs were being gathered so that I and other aspiring gastroenterologists will be able to sit comfortably at these tables one day. I was witnessing these GI professional leaders set in motion the beginning of what will undoubtedly be a pivotal component in the way I approach my career as a gastroenterologist. The experience reignited my mental determination to one day attain the level of success represented by the ABGH board members and to persevere in my quest to help redefine how Black medical students and residents serve their communities as physicians.

The creation of the ABGH could not have come at a better time in my training. In the wake of recent public protests for equity of African Americans within every institution (academia, housing, banks, policing, health care, and beyond), which were fundamentally built on racism, being a junior member of ABGH has not only given me a platform to speak my truth but has also provided me with tools to help others do so as well. As someone very passionate about research, primarily in colorectal cancer, I have been given an opportunity to connect with a dream team of mentors who have taken research ideas to new levels and have challenged me to dig deeper and expand my curiosity to investigate what still needs to be uncovered. It has created opportunity after opportunity for actively building relationships, leading to meaningful collaborations and the sharing of innovative ideas and discoveries.

It is important to emphasize that ABGH is not an organization wanting to exclude themselves on the basis of ethnicity. ABGH is an example of how shared health goals within a medical discipline can be achieved when inclusion and equity is at the helm. ABGH led and represented events that raise awareness of diseases affecting all patients and aim to make the GI community more culturally competent. ABGH is future-oriented and embraces all members who align with the mission regardless of ethnicity, gender, orientation, or disability. The institution that is and will be the ABGH impresses upon me a feeling of excitement, gratitude, and humility. I look forward to continuing the mission created by the founding members and being to others what ABGH is to me.

For more information on this organization, please visit blackingastro.org.

Dr. Busari is a resident physician at Florida State University-SMH and a junior member of ABGH. Dr. Guillaume director of the Gastrointestinal Motility Center at Stony Brook (New York) University Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. They have no disclosures.

References

1. Galarneau C. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):5-8.

2. Ashktorab H et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Oct;153(4):910-923.

3. Blanchard AK. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun 10;384(23):e87.

Long COVID appears to ‘impair’ survival in cancer patients

More than one in six cancer patients experience long-term sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection, placing them at increased risk of discontinuing their cancer treatment or dying, according to European registry data.

Given the “high lethality” of COVID-19 in cancer patients and the risk for long-term complications following infection in the general population, Alessio Cortellini, MD, a consultant medical oncologist at Hammersmith Hospital and Imperial College London, and colleagues wanted to explore the “prevalence and clinical significance of COVID-19 sequelae in cancer patients and their oncological continuity of care.”

Dr. Cortellini presented the OnCovid registry research on Sept. 21 at the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress. He reported that overall, the data suggest that post–COVID-19 complications may “impair” patients’ cancer survival as well as their cancer care.

The OnCovid registry data showed that the 15% of cancer patients who had long-term COVID-19 complications were 76% more likely to die than those without sequelae. Cancer patients with COVID-19 sequelae were significantly more likely to permanently stop taking their systemic anticancer therapy, and they were more than 3.5 times more likely to die than those who continued their treatment as planned. In terms of long-term complications, almost half of patients experienced dyspnea, and two-fifths reported chronic fatigue.

“This data confirms the need to continue to prioritize cancer patients,” Antonio Passaro, MD, PhD, division of thoracic oncology, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, Milan, commented in a press release. “In the fight against the pandemic, it is of the utmost importance that we do not neglect to study and understand the curves of cancer incidence and mortality.”

Invited to discuss the results, Anne-Marie C. Dingemans, MD, PhD, a pulmonologist and professor of thoracic oncology at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, said COVID-19 remains a “very important” issue for cancer patients.

Interestingly, Dr. Dingemans noted that COVID-19 sequelae in patients with cancer appear to occur slightly less frequently, compared with estimates in the general population – which range from 13% to 60% – though patients with cancer tend to have more respiratory problems.

However, Dr. Dingemans added, the difficulty with comparing sequelae rates between cancer patients and the general population is that cancer patients “probably already have a lot of symptoms” associated with long COVID, such as dyspnea and fatigue, and may not be aware that they are experiencing COVID sequelae.

The registry results

To investigate the long-term impact of COVID-19 on survival and continuity of care, the team examined data from the OnCovid registry, which was established at the beginning of the pandemic to study consecutive patients aged 18 years and older with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and a history of solid or hematologic malignancies.

At the data cutoff on March 1, 2021, the registry included 35 institutions in six European countries. The institutions collected information on patient demographics and comorbidities, cancer history, anticancer therapy, COVID-19 investigations, and COVID-19–specific therapies.

For the current analysis, the team included 1,557 of 2,634 patients who had undergone a clinical reassessment after recovering from COVID-19. Information sufficient to conduct multivariate analysis was available for 840 of these patients.

About half of the patients were younger than 60 years, and just over half were women. The most common cancer diagnoses were breast cancer (23.4%), gastrointestinal tumors (16.5%), gynecologic/genitourinary tumors (19.3%), and hematologic cancers (14.1%), with even distribution between local/locoregional and advanced disease.

The median interval between COVID-19 recovery and reassessment was 44 days, and the mean post–COVID-19 follow-up period was 128 days.

About 15% of patients experienced at least one long-term sequela from COVID-19. The most common were dyspnea/shortness of breath (49.6%), fatigue (41.0%), chronic cough (33.8%), and other respiratory complications (10.7%).

Dr. Cortellini noted that cancer patients who experienced sequelae were more likely to be male, aged 65 years or older, to have at least two comorbidities, and to have a history of smoking. In addition, cancer patients who experienced long-term complications were significantly more likely to have had COVID-19 complications, to have required COVID-19 therapy, and to have been hospitalized for the disease.

Factoring in gender, age, comorbidity burden, primary tumor, stage, receipt of anticancer and anti–COVID-19 therapy, COVID-19 complications, and hospitalization, the team found that COVID-19 sequelae were independently associated with an increased risk for death (hazard ratio, 1.76).

Further analysis of patterns of systemic anticancer therapy in 471 patients revealed that 14.8% of COVID-19 survivors permanently discontinued therapy and that a dose or regimen adjustment occurred for 37.8%.

Patients who permanently discontinued anticancer therapy were more likely to be former or current smokers, to have had COVID-19 complications or been hospitalized for COVID-19, and to have had COVID-19 sequelae at reassessment. The investigators found no association between permanent discontinuation of therapy and cancer disease stage.

Dr. Cortellini and colleagues reported that permanent cessation of systemic anticancer therapy was associated with an increased risk for death. A change in dose or regimen did not affect survival.

The most common reason for stopping therapy permanently was deterioration of the patient’s performance status (61.3%), followed by disease progression (29.0%). Dose or regimen adjustments typically occurred to avoid immune suppression (50.0%), hospitalization (25.8%), and intravenous drug administration (19.1%).

Dr. Cortellini concluded his presentation by highlighting the importance of increasing awareness of long COVID in patients with cancer as well as early treatment of COVID-19 sequelae to improve patient outcomes.

The study was funded by the Imperial College Biomedical Research Center. Dr. Cortellini has relationships with MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Astellas, and Sun Pharma. Dr. Dingemans has relationships with Roche, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Jansen, Chiesi, Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Takeda, Pharmamar, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than one in six cancer patients experience long-term sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection, placing them at increased risk of discontinuing their cancer treatment or dying, according to European registry data.

Given the “high lethality” of COVID-19 in cancer patients and the risk for long-term complications following infection in the general population, Alessio Cortellini, MD, a consultant medical oncologist at Hammersmith Hospital and Imperial College London, and colleagues wanted to explore the “prevalence and clinical significance of COVID-19 sequelae in cancer patients and their oncological continuity of care.”

Dr. Cortellini presented the OnCovid registry research on Sept. 21 at the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress. He reported that overall, the data suggest that post–COVID-19 complications may “impair” patients’ cancer survival as well as their cancer care.

The OnCovid registry data showed that the 15% of cancer patients who had long-term COVID-19 complications were 76% more likely to die than those without sequelae. Cancer patients with COVID-19 sequelae were significantly more likely to permanently stop taking their systemic anticancer therapy, and they were more than 3.5 times more likely to die than those who continued their treatment as planned. In terms of long-term complications, almost half of patients experienced dyspnea, and two-fifths reported chronic fatigue.

“This data confirms the need to continue to prioritize cancer patients,” Antonio Passaro, MD, PhD, division of thoracic oncology, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, Milan, commented in a press release. “In the fight against the pandemic, it is of the utmost importance that we do not neglect to study and understand the curves of cancer incidence and mortality.”

Invited to discuss the results, Anne-Marie C. Dingemans, MD, PhD, a pulmonologist and professor of thoracic oncology at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, said COVID-19 remains a “very important” issue for cancer patients.

Interestingly, Dr. Dingemans noted that COVID-19 sequelae in patients with cancer appear to occur slightly less frequently, compared with estimates in the general population – which range from 13% to 60% – though patients with cancer tend to have more respiratory problems.

However, Dr. Dingemans added, the difficulty with comparing sequelae rates between cancer patients and the general population is that cancer patients “probably already have a lot of symptoms” associated with long COVID, such as dyspnea and fatigue, and may not be aware that they are experiencing COVID sequelae.

The registry results

To investigate the long-term impact of COVID-19 on survival and continuity of care, the team examined data from the OnCovid registry, which was established at the beginning of the pandemic to study consecutive patients aged 18 years and older with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and a history of solid or hematologic malignancies.

At the data cutoff on March 1, 2021, the registry included 35 institutions in six European countries. The institutions collected information on patient demographics and comorbidities, cancer history, anticancer therapy, COVID-19 investigations, and COVID-19–specific therapies.

For the current analysis, the team included 1,557 of 2,634 patients who had undergone a clinical reassessment after recovering from COVID-19. Information sufficient to conduct multivariate analysis was available for 840 of these patients.

About half of the patients were younger than 60 years, and just over half were women. The most common cancer diagnoses were breast cancer (23.4%), gastrointestinal tumors (16.5%), gynecologic/genitourinary tumors (19.3%), and hematologic cancers (14.1%), with even distribution between local/locoregional and advanced disease.

The median interval between COVID-19 recovery and reassessment was 44 days, and the mean post–COVID-19 follow-up period was 128 days.

About 15% of patients experienced at least one long-term sequela from COVID-19. The most common were dyspnea/shortness of breath (49.6%), fatigue (41.0%), chronic cough (33.8%), and other respiratory complications (10.7%).

Dr. Cortellini noted that cancer patients who experienced sequelae were more likely to be male, aged 65 years or older, to have at least two comorbidities, and to have a history of smoking. In addition, cancer patients who experienced long-term complications were significantly more likely to have had COVID-19 complications, to have required COVID-19 therapy, and to have been hospitalized for the disease.

Factoring in gender, age, comorbidity burden, primary tumor, stage, receipt of anticancer and anti–COVID-19 therapy, COVID-19 complications, and hospitalization, the team found that COVID-19 sequelae were independently associated with an increased risk for death (hazard ratio, 1.76).

Further analysis of patterns of systemic anticancer therapy in 471 patients revealed that 14.8% of COVID-19 survivors permanently discontinued therapy and that a dose or regimen adjustment occurred for 37.8%.

Patients who permanently discontinued anticancer therapy were more likely to be former or current smokers, to have had COVID-19 complications or been hospitalized for COVID-19, and to have had COVID-19 sequelae at reassessment. The investigators found no association between permanent discontinuation of therapy and cancer disease stage.

Dr. Cortellini and colleagues reported that permanent cessation of systemic anticancer therapy was associated with an increased risk for death. A change in dose or regimen did not affect survival.

The most common reason for stopping therapy permanently was deterioration of the patient’s performance status (61.3%), followed by disease progression (29.0%). Dose or regimen adjustments typically occurred to avoid immune suppression (50.0%), hospitalization (25.8%), and intravenous drug administration (19.1%).

Dr. Cortellini concluded his presentation by highlighting the importance of increasing awareness of long COVID in patients with cancer as well as early treatment of COVID-19 sequelae to improve patient outcomes.

The study was funded by the Imperial College Biomedical Research Center. Dr. Cortellini has relationships with MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Astellas, and Sun Pharma. Dr. Dingemans has relationships with Roche, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Jansen, Chiesi, Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Takeda, Pharmamar, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than one in six cancer patients experience long-term sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection, placing them at increased risk of discontinuing their cancer treatment or dying, according to European registry data.

Given the “high lethality” of COVID-19 in cancer patients and the risk for long-term complications following infection in the general population, Alessio Cortellini, MD, a consultant medical oncologist at Hammersmith Hospital and Imperial College London, and colleagues wanted to explore the “prevalence and clinical significance of COVID-19 sequelae in cancer patients and their oncological continuity of care.”

Dr. Cortellini presented the OnCovid registry research on Sept. 21 at the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress. He reported that overall, the data suggest that post–COVID-19 complications may “impair” patients’ cancer survival as well as their cancer care.

The OnCovid registry data showed that the 15% of cancer patients who had long-term COVID-19 complications were 76% more likely to die than those without sequelae. Cancer patients with COVID-19 sequelae were significantly more likely to permanently stop taking their systemic anticancer therapy, and they were more than 3.5 times more likely to die than those who continued their treatment as planned. In terms of long-term complications, almost half of patients experienced dyspnea, and two-fifths reported chronic fatigue.

“This data confirms the need to continue to prioritize cancer patients,” Antonio Passaro, MD, PhD, division of thoracic oncology, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, Milan, commented in a press release. “In the fight against the pandemic, it is of the utmost importance that we do not neglect to study and understand the curves of cancer incidence and mortality.”

Invited to discuss the results, Anne-Marie C. Dingemans, MD, PhD, a pulmonologist and professor of thoracic oncology at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, said COVID-19 remains a “very important” issue for cancer patients.

Interestingly, Dr. Dingemans noted that COVID-19 sequelae in patients with cancer appear to occur slightly less frequently, compared with estimates in the general population – which range from 13% to 60% – though patients with cancer tend to have more respiratory problems.

However, Dr. Dingemans added, the difficulty with comparing sequelae rates between cancer patients and the general population is that cancer patients “probably already have a lot of symptoms” associated with long COVID, such as dyspnea and fatigue, and may not be aware that they are experiencing COVID sequelae.

The registry results

To investigate the long-term impact of COVID-19 on survival and continuity of care, the team examined data from the OnCovid registry, which was established at the beginning of the pandemic to study consecutive patients aged 18 years and older with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and a history of solid or hematologic malignancies.

At the data cutoff on March 1, 2021, the registry included 35 institutions in six European countries. The institutions collected information on patient demographics and comorbidities, cancer history, anticancer therapy, COVID-19 investigations, and COVID-19–specific therapies.

For the current analysis, the team included 1,557 of 2,634 patients who had undergone a clinical reassessment after recovering from COVID-19. Information sufficient to conduct multivariate analysis was available for 840 of these patients.

About half of the patients were younger than 60 years, and just over half were women. The most common cancer diagnoses were breast cancer (23.4%), gastrointestinal tumors (16.5%), gynecologic/genitourinary tumors (19.3%), and hematologic cancers (14.1%), with even distribution between local/locoregional and advanced disease.

The median interval between COVID-19 recovery and reassessment was 44 days, and the mean post–COVID-19 follow-up period was 128 days.

About 15% of patients experienced at least one long-term sequela from COVID-19. The most common were dyspnea/shortness of breath (49.6%), fatigue (41.0%), chronic cough (33.8%), and other respiratory complications (10.7%).

Dr. Cortellini noted that cancer patients who experienced sequelae were more likely to be male, aged 65 years or older, to have at least two comorbidities, and to have a history of smoking. In addition, cancer patients who experienced long-term complications were significantly more likely to have had COVID-19 complications, to have required COVID-19 therapy, and to have been hospitalized for the disease.

Factoring in gender, age, comorbidity burden, primary tumor, stage, receipt of anticancer and anti–COVID-19 therapy, COVID-19 complications, and hospitalization, the team found that COVID-19 sequelae were independently associated with an increased risk for death (hazard ratio, 1.76).

Further analysis of patterns of systemic anticancer therapy in 471 patients revealed that 14.8% of COVID-19 survivors permanently discontinued therapy and that a dose or regimen adjustment occurred for 37.8%.

Patients who permanently discontinued anticancer therapy were more likely to be former or current smokers, to have had COVID-19 complications or been hospitalized for COVID-19, and to have had COVID-19 sequelae at reassessment. The investigators found no association between permanent discontinuation of therapy and cancer disease stage.

Dr. Cortellini and colleagues reported that permanent cessation of systemic anticancer therapy was associated with an increased risk for death. A change in dose or regimen did not affect survival.

The most common reason for stopping therapy permanently was deterioration of the patient’s performance status (61.3%), followed by disease progression (29.0%). Dose or regimen adjustments typically occurred to avoid immune suppression (50.0%), hospitalization (25.8%), and intravenous drug administration (19.1%).

Dr. Cortellini concluded his presentation by highlighting the importance of increasing awareness of long COVID in patients with cancer as well as early treatment of COVID-19 sequelae to improve patient outcomes.

The study was funded by the Imperial College Biomedical Research Center. Dr. Cortellini has relationships with MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Astellas, and Sun Pharma. Dr. Dingemans has relationships with Roche, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Jansen, Chiesi, Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Takeda, Pharmamar, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Management of advanced endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is most commonly diagnosed at an early stage. Unfortunately, there is a trend toward the diagnosis of more advanced disease, for which cure is rare, and this is an important contributing factor toward the overall increasing mortality trend for endometrial cancer.

Histology is a major risk factor for advanced disease. For example, serous carcinoma, which accounts for approximately only 10% of all endometrial cancer diagnoses, comprises 25% of cases of advanced cases. Similarly, carcinosarcoma, a cell type known to be particularly aggressive, is relatively overrepresented among cases of advanced disease.

Advanced endometrial cancer includes cases of stage III (involvement of lymph nodes, ovaries, and vagina) and stage IV disease (with direct extension into pelvic viscera and distant metastases). In most cases of stage III disease, extrauterine metastases are microscopic and are detected only at the time of surgical staging. Bulky nodal disease within the pelvic and para-aortic nodal basins is less common but associated with worse prognosis than for patients with microscopic nodal metastases. Stage IV disease usually presents with peritoneal spread of disease including carcinomatosis, omental disease, and involvement of the small and large intestine.

Once advanced, endometrial cancer requires more than surgery alone, relying heavily on adjuvant therapies to achieve responses, particularly systemic therapy with platinum and taxane chemotherapy. In some cases, molecularly targeted therapy (such as trastuzumab for serous carcinomas that demonstrate overexpression of HER2) has been shown to be superior in efficacy.1 Surgery may involve either radical nodal dissections to the infrarenal aortic basin, and/or peritoneal debulking procedures similar to that required for ovarian cancer. Perhaps because of patterns of disease distribution so similar to ovarian cancer, historically, sequencing of therapy focused on radical primary debulking surgery (PDS) followed by chemotherapy.

In 2000, a retrospective series from Johns Hopkins University documented the outcomes of 65 patients with advanced endometrial cancer who had undergone primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy.2 They noted that survival was directly associated with degree of cytoreduction, with the best outcomes seen for those patients whose surgery resulted in no gross residual disease. Following these data, PDS with complete resection of all disease became the goal of primary therapy.

However, unlike ovarian cancer (which shares a similar disease distribution with advanced endometrial cancer) patients with endometrial cancer are more obese, older, and typically have more comorbidities. Therefore, radical primary debulking surgeries may be associated with poor patient perioperative outcomes, and feasibility of complete cytoreduction, particularly in very obese patients, can be limited. For this reason, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has been explored as an option. The potential virtue of NACT is that it allows for tumor deposits to decrease in size, or be eliminated, prior to surgery, resulting in a less morbid procedure for the patient.

Observed outcomes for NACT relative to PDS are mixed. When small series have compared the two for the treatment of advanced serous endometrial cancer, NACT was associated with decreased perioperative morbidity, with similar overall survival observed.3,4

However, in larger series exploring patients within the National Cancer Database (a collection of over 1,500 hospitals accredited by the Commission on Cancer) outcomes appear different for the two approaches.5,6 While PDS was initially associated with worse survival, at approximately 5-6 months from diagnosis, this changed and survival was observed to be consistently superior for this group. These data suggest that patients undergoing primary surgical cytoreduction may experience an early mortality risk, possibly secondary to the impact of surgery, but that if they are to survive beyond this point, they experience better outcomes. While the researchers attempted to control for risk factors of poor outcomes that might have systematically differed between the two groups, this specific database is limited in its ability to account for all fundamental differences between them. Only approximately 15% of women with advanced endometrial cancer were offered NACT during those time periods. This observation alone suggests that this likely represents a group specially selected for their poor candidacy for upfront debulking surgery, and inherently increased risk for death from all causes.

The question remains, is NACT appropriate for all patients or just those who are considered poor surgical candidates? Could all patients benefit from the decreased morbidity associated with surgery after NACT without compromising survival? Randomized controlled trials are necessary to answer this question as they are the only way to ensure that risk factors for poor outcomes (such as histology, disease distribution, medical comorbidities) are equally distributed among both groups.

In the meantime, gynecologic oncologists should take a cautious approach to decision making regarding sequencing of surgery and chemotherapy in the setting of a new diagnosis of advanced endometrial cancer. Arguably more important than surgical interventions, access to molecularly targeted systemic therapy is likely to bring the best outcomes for advanced endometrial cancer. Carboplatin and paclitaxel are the current gold standard of care for frontline systemic therapy; however, response rates with this regimen are less favorable for endometrial cancer than for ovarian cancer. Work is being done to test novel therapies against actionable targets to use as alternatives or as adjuncts to traditional chemotherapy regimens. In doing so, clinicians are learning to distinguish endometrial cancers by more than simply their histologic features, but also by their molecular profiles.

Advanced endometrial cancer is a serious disease with high lethality. Future research should focus on ways to ensure toxicities of therapy, including surgery, are minimized while improving upon existing poor clinical outcomes.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no financial disclosures.

References

1. Fader AN et al. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(20):2044-51.

2. Bristow RE et al. Gynecol Oncol 2000;78(2):85-91.

3. Bogani G et al. Tumori 2019;105(1):92-97.

4. Wilkinson-Ryan I et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(1):63-8.

5. Tobias CJ et al. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2028612.

6. Chambers LM et al. Gynecol Oncol 2021;160(2):405-12.

Endometrial cancer is most commonly diagnosed at an early stage. Unfortunately, there is a trend toward the diagnosis of more advanced disease, for which cure is rare, and this is an important contributing factor toward the overall increasing mortality trend for endometrial cancer.

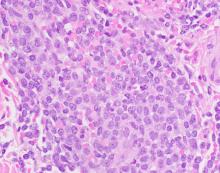

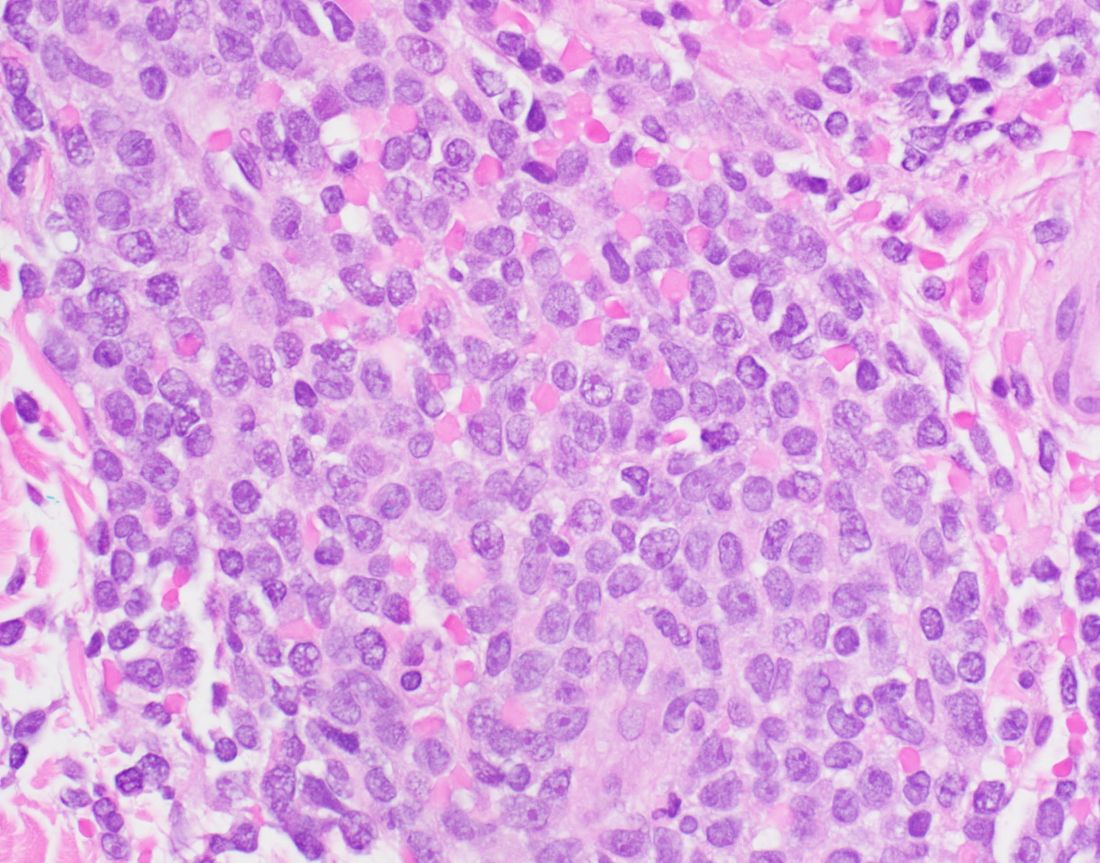

Histology is a major risk factor for advanced disease. For example, serous carcinoma, which accounts for approximately only 10% of all endometrial cancer diagnoses, comprises 25% of cases of advanced cases. Similarly, carcinosarcoma, a cell type known to be particularly aggressive, is relatively overrepresented among cases of advanced disease.

Advanced endometrial cancer includes cases of stage III (involvement of lymph nodes, ovaries, and vagina) and stage IV disease (with direct extension into pelvic viscera and distant metastases). In most cases of stage III disease, extrauterine metastases are microscopic and are detected only at the time of surgical staging. Bulky nodal disease within the pelvic and para-aortic nodal basins is less common but associated with worse prognosis than for patients with microscopic nodal metastases. Stage IV disease usually presents with peritoneal spread of disease including carcinomatosis, omental disease, and involvement of the small and large intestine.

Once advanced, endometrial cancer requires more than surgery alone, relying heavily on adjuvant therapies to achieve responses, particularly systemic therapy with platinum and taxane chemotherapy. In some cases, molecularly targeted therapy (such as trastuzumab for serous carcinomas that demonstrate overexpression of HER2) has been shown to be superior in efficacy.1 Surgery may involve either radical nodal dissections to the infrarenal aortic basin, and/or peritoneal debulking procedures similar to that required for ovarian cancer. Perhaps because of patterns of disease distribution so similar to ovarian cancer, historically, sequencing of therapy focused on radical primary debulking surgery (PDS) followed by chemotherapy.

In 2000, a retrospective series from Johns Hopkins University documented the outcomes of 65 patients with advanced endometrial cancer who had undergone primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy.2 They noted that survival was directly associated with degree of cytoreduction, with the best outcomes seen for those patients whose surgery resulted in no gross residual disease. Following these data, PDS with complete resection of all disease became the goal of primary therapy.

However, unlike ovarian cancer (which shares a similar disease distribution with advanced endometrial cancer) patients with endometrial cancer are more obese, older, and typically have more comorbidities. Therefore, radical primary debulking surgeries may be associated with poor patient perioperative outcomes, and feasibility of complete cytoreduction, particularly in very obese patients, can be limited. For this reason, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has been explored as an option. The potential virtue of NACT is that it allows for tumor deposits to decrease in size, or be eliminated, prior to surgery, resulting in a less morbid procedure for the patient.

Observed outcomes for NACT relative to PDS are mixed. When small series have compared the two for the treatment of advanced serous endometrial cancer, NACT was associated with decreased perioperative morbidity, with similar overall survival observed.3,4

However, in larger series exploring patients within the National Cancer Database (a collection of over 1,500 hospitals accredited by the Commission on Cancer) outcomes appear different for the two approaches.5,6 While PDS was initially associated with worse survival, at approximately 5-6 months from diagnosis, this changed and survival was observed to be consistently superior for this group. These data suggest that patients undergoing primary surgical cytoreduction may experience an early mortality risk, possibly secondary to the impact of surgery, but that if they are to survive beyond this point, they experience better outcomes. While the researchers attempted to control for risk factors of poor outcomes that might have systematically differed between the two groups, this specific database is limited in its ability to account for all fundamental differences between them. Only approximately 15% of women with advanced endometrial cancer were offered NACT during those time periods. This observation alone suggests that this likely represents a group specially selected for their poor candidacy for upfront debulking surgery, and inherently increased risk for death from all causes.

The question remains, is NACT appropriate for all patients or just those who are considered poor surgical candidates? Could all patients benefit from the decreased morbidity associated with surgery after NACT without compromising survival? Randomized controlled trials are necessary to answer this question as they are the only way to ensure that risk factors for poor outcomes (such as histology, disease distribution, medical comorbidities) are equally distributed among both groups.

In the meantime, gynecologic oncologists should take a cautious approach to decision making regarding sequencing of surgery and chemotherapy in the setting of a new diagnosis of advanced endometrial cancer. Arguably more important than surgical interventions, access to molecularly targeted systemic therapy is likely to bring the best outcomes for advanced endometrial cancer. Carboplatin and paclitaxel are the current gold standard of care for frontline systemic therapy; however, response rates with this regimen are less favorable for endometrial cancer than for ovarian cancer. Work is being done to test novel therapies against actionable targets to use as alternatives or as adjuncts to traditional chemotherapy regimens. In doing so, clinicians are learning to distinguish endometrial cancers by more than simply their histologic features, but also by their molecular profiles.

Advanced endometrial cancer is a serious disease with high lethality. Future research should focus on ways to ensure toxicities of therapy, including surgery, are minimized while improving upon existing poor clinical outcomes.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no financial disclosures.

References

1. Fader AN et al. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(20):2044-51.

2. Bristow RE et al. Gynecol Oncol 2000;78(2):85-91.

3. Bogani G et al. Tumori 2019;105(1):92-97.

4. Wilkinson-Ryan I et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(1):63-8.

5. Tobias CJ et al. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2028612.

6. Chambers LM et al. Gynecol Oncol 2021;160(2):405-12.

Endometrial cancer is most commonly diagnosed at an early stage. Unfortunately, there is a trend toward the diagnosis of more advanced disease, for which cure is rare, and this is an important contributing factor toward the overall increasing mortality trend for endometrial cancer.

Histology is a major risk factor for advanced disease. For example, serous carcinoma, which accounts for approximately only 10% of all endometrial cancer diagnoses, comprises 25% of cases of advanced cases. Similarly, carcinosarcoma, a cell type known to be particularly aggressive, is relatively overrepresented among cases of advanced disease.

Advanced endometrial cancer includes cases of stage III (involvement of lymph nodes, ovaries, and vagina) and stage IV disease (with direct extension into pelvic viscera and distant metastases). In most cases of stage III disease, extrauterine metastases are microscopic and are detected only at the time of surgical staging. Bulky nodal disease within the pelvic and para-aortic nodal basins is less common but associated with worse prognosis than for patients with microscopic nodal metastases. Stage IV disease usually presents with peritoneal spread of disease including carcinomatosis, omental disease, and involvement of the small and large intestine.

Once advanced, endometrial cancer requires more than surgery alone, relying heavily on adjuvant therapies to achieve responses, particularly systemic therapy with platinum and taxane chemotherapy. In some cases, molecularly targeted therapy (such as trastuzumab for serous carcinomas that demonstrate overexpression of HER2) has been shown to be superior in efficacy.1 Surgery may involve either radical nodal dissections to the infrarenal aortic basin, and/or peritoneal debulking procedures similar to that required for ovarian cancer. Perhaps because of patterns of disease distribution so similar to ovarian cancer, historically, sequencing of therapy focused on radical primary debulking surgery (PDS) followed by chemotherapy.

In 2000, a retrospective series from Johns Hopkins University documented the outcomes of 65 patients with advanced endometrial cancer who had undergone primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy.2 They noted that survival was directly associated with degree of cytoreduction, with the best outcomes seen for those patients whose surgery resulted in no gross residual disease. Following these data, PDS with complete resection of all disease became the goal of primary therapy.

However, unlike ovarian cancer (which shares a similar disease distribution with advanced endometrial cancer) patients with endometrial cancer are more obese, older, and typically have more comorbidities. Therefore, radical primary debulking surgeries may be associated with poor patient perioperative outcomes, and feasibility of complete cytoreduction, particularly in very obese patients, can be limited. For this reason, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has been explored as an option. The potential virtue of NACT is that it allows for tumor deposits to decrease in size, or be eliminated, prior to surgery, resulting in a less morbid procedure for the patient.

Observed outcomes for NACT relative to PDS are mixed. When small series have compared the two for the treatment of advanced serous endometrial cancer, NACT was associated with decreased perioperative morbidity, with similar overall survival observed.3,4

However, in larger series exploring patients within the National Cancer Database (a collection of over 1,500 hospitals accredited by the Commission on Cancer) outcomes appear different for the two approaches.5,6 While PDS was initially associated with worse survival, at approximately 5-6 months from diagnosis, this changed and survival was observed to be consistently superior for this group. These data suggest that patients undergoing primary surgical cytoreduction may experience an early mortality risk, possibly secondary to the impact of surgery, but that if they are to survive beyond this point, they experience better outcomes. While the researchers attempted to control for risk factors of poor outcomes that might have systematically differed between the two groups, this specific database is limited in its ability to account for all fundamental differences between them. Only approximately 15% of women with advanced endometrial cancer were offered NACT during those time periods. This observation alone suggests that this likely represents a group specially selected for their poor candidacy for upfront debulking surgery, and inherently increased risk for death from all causes.

The question remains, is NACT appropriate for all patients or just those who are considered poor surgical candidates? Could all patients benefit from the decreased morbidity associated with surgery after NACT without compromising survival? Randomized controlled trials are necessary to answer this question as they are the only way to ensure that risk factors for poor outcomes (such as histology, disease distribution, medical comorbidities) are equally distributed among both groups.

In the meantime, gynecologic oncologists should take a cautious approach to decision making regarding sequencing of surgery and chemotherapy in the setting of a new diagnosis of advanced endometrial cancer. Arguably more important than surgical interventions, access to molecularly targeted systemic therapy is likely to bring the best outcomes for advanced endometrial cancer. Carboplatin and paclitaxel are the current gold standard of care for frontline systemic therapy; however, response rates with this regimen are less favorable for endometrial cancer than for ovarian cancer. Work is being done to test novel therapies against actionable targets to use as alternatives or as adjuncts to traditional chemotherapy regimens. In doing so, clinicians are learning to distinguish endometrial cancers by more than simply their histologic features, but also by their molecular profiles.

Advanced endometrial cancer is a serious disease with high lethality. Future research should focus on ways to ensure toxicities of therapy, including surgery, are minimized while improving upon existing poor clinical outcomes.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no financial disclosures.

References

1. Fader AN et al. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(20):2044-51.

2. Bristow RE et al. Gynecol Oncol 2000;78(2):85-91.

3. Bogani G et al. Tumori 2019;105(1):92-97.

4. Wilkinson-Ryan I et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(1):63-8.

5. Tobias CJ et al. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2028612.

6. Chambers LM et al. Gynecol Oncol 2021;160(2):405-12.

An appeal for equitable access to care for early pregnancy loss

Remarkable advances in care for early pregnancy loss (EPL) have occurred over the past several years. Misoprostol with mifepristone pretreatment is now the gold standard for medical management after recent research showed that this regimen improves both the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of medical management.1 Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)’s portability, effectiveness, and safety ensure that providers can offer procedural EPL management in almost any clinical setting. Medication management and in-office uterine aspiration are two evidence-based options for EPL management that may increase access for the 25% of pregnant women who experience EPL. Unfortunately, many women do not have access to either option. Equitable access to early pregnancy loss management can be achieved by expanding access to mifepristone and office-based MVA.

However, access to mifepristone and initiating office-based MVA is challenging. Mifepristone is one of several medications regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Management Strategies (REMS) program.2

The REMS guidelines restrict clinicians in prescribing and dispensing mifepristone, including the key provision that mifepristone may be dispensed only in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals. Clinicians cannot write a prescription for mifepristone for a patient to pick up at the pharmacy. Efforts are underway to roll back the REMS. Barriers to office-based MVA include time, culture shift among staff, gathering equipment, and creating protocols. Clinicians can improve access to EPL management in a variety of ways:

- MVA training: Ob.gyns. who lack training in MVA use can take advantage of several programs designed to teach the skill to clinicians, including programs such as Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management (TEAMM).3,4 MVA is easy to learn for ob.gyns. and procedural complications are uncommon. In the office setting, complications requiring transfer to a higher level of care are rare.5 With adequate training, whether during residency or afterward, ob.gyns. can learn to safely and effectively use MVA for procedural EPL management in the office and in the emergency department.

- Partnerships with pharmacists to reduce barriers to mifepristone: Ob.gyns. working in a variety of clinical settings, including independent clinics, critical access hospitals, community hospitals, and academic medical centers, have worked closely with on-site pharmacists to place mifepristone on their practice sites’ formularies.6 These ob.gyn.–pharmacist collaborations often require explanations to institutional Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees of the benefits of mifepristone to patients, detailed indications for mifepristone’s use, and methods to secure mifepristone on site.

- Partnerships with emergency department and outpatient nursing and administration to promote MVA: Provision of MVA is ideal for safe, effective, and cost-efficient procedural EPL management in both the emergency department and outpatient setting. However, access to MVA in emergency rooms and outpatient clinical settings is suboptimal. Some clinicians push back against MVA use in the emergency department, citing fears that performing the procedure in the emergency department unnecessarily uses staff and resources reserved for patients with more critical illnesses. Ob.gyns. should also work with emergency medicine physicians and emergency department nursing staff and hospital administrators in explaining that MVA in the emergency room is patient centered and cost effective.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and training are two strategies that can increase access to mifepristone and MVA for EPL management. Use of mifepristone/misoprostol and office/emergency department MVA for treatment of EPL is patient centered, evidence based, feasible, highly effective, and timely. These two health care interventions are practical in almost any setting, including rural and other low-resource settings. By using these strategies to overcome the logistical and institutional challenges, ob.gyns. can help countless women with EPL gain access to the best EPL care.

Dr. Espey is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Jackson is an obstetrician/gynecologist at Michigan State University in Flint. They have no disclosures to report.

References

1. Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 7;378(23):2161-70.

2. Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information.

3. The TEAMM (Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management) Project. Training interprofessional teams to manage miscarriage. Accessed March 15, 2021.

4. Quinley KE et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;72(1):86-92.

5. Milingos DS et al. BJOG. 2009 Aug;116(9):1268-71.

6. Calloway D et al. Contraception. 2021 Jul;104(1):24-8.

Remarkable advances in care for early pregnancy loss (EPL) have occurred over the past several years. Misoprostol with mifepristone pretreatment is now the gold standard for medical management after recent research showed that this regimen improves both the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of medical management.1 Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)’s portability, effectiveness, and safety ensure that providers can offer procedural EPL management in almost any clinical setting. Medication management and in-office uterine aspiration are two evidence-based options for EPL management that may increase access for the 25% of pregnant women who experience EPL. Unfortunately, many women do not have access to either option. Equitable access to early pregnancy loss management can be achieved by expanding access to mifepristone and office-based MVA.

However, access to mifepristone and initiating office-based MVA is challenging. Mifepristone is one of several medications regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Management Strategies (REMS) program.2

The REMS guidelines restrict clinicians in prescribing and dispensing mifepristone, including the key provision that mifepristone may be dispensed only in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals. Clinicians cannot write a prescription for mifepristone for a patient to pick up at the pharmacy. Efforts are underway to roll back the REMS. Barriers to office-based MVA include time, culture shift among staff, gathering equipment, and creating protocols. Clinicians can improve access to EPL management in a variety of ways:

- MVA training: Ob.gyns. who lack training in MVA use can take advantage of several programs designed to teach the skill to clinicians, including programs such as Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management (TEAMM).3,4 MVA is easy to learn for ob.gyns. and procedural complications are uncommon. In the office setting, complications requiring transfer to a higher level of care are rare.5 With adequate training, whether during residency or afterward, ob.gyns. can learn to safely and effectively use MVA for procedural EPL management in the office and in the emergency department.

- Partnerships with pharmacists to reduce barriers to mifepristone: Ob.gyns. working in a variety of clinical settings, including independent clinics, critical access hospitals, community hospitals, and academic medical centers, have worked closely with on-site pharmacists to place mifepristone on their practice sites’ formularies.6 These ob.gyn.–pharmacist collaborations often require explanations to institutional Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees of the benefits of mifepristone to patients, detailed indications for mifepristone’s use, and methods to secure mifepristone on site.

- Partnerships with emergency department and outpatient nursing and administration to promote MVA: Provision of MVA is ideal for safe, effective, and cost-efficient procedural EPL management in both the emergency department and outpatient setting. However, access to MVA in emergency rooms and outpatient clinical settings is suboptimal. Some clinicians push back against MVA use in the emergency department, citing fears that performing the procedure in the emergency department unnecessarily uses staff and resources reserved for patients with more critical illnesses. Ob.gyns. should also work with emergency medicine physicians and emergency department nursing staff and hospital administrators in explaining that MVA in the emergency room is patient centered and cost effective.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and training are two strategies that can increase access to mifepristone and MVA for EPL management. Use of mifepristone/misoprostol and office/emergency department MVA for treatment of EPL is patient centered, evidence based, feasible, highly effective, and timely. These two health care interventions are practical in almost any setting, including rural and other low-resource settings. By using these strategies to overcome the logistical and institutional challenges, ob.gyns. can help countless women with EPL gain access to the best EPL care.

Dr. Espey is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Jackson is an obstetrician/gynecologist at Michigan State University in Flint. They have no disclosures to report.

References

1. Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 7;378(23):2161-70.

2. Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information.

3. The TEAMM (Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management) Project. Training interprofessional teams to manage miscarriage. Accessed March 15, 2021.

4. Quinley KE et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;72(1):86-92.

5. Milingos DS et al. BJOG. 2009 Aug;116(9):1268-71.

6. Calloway D et al. Contraception. 2021 Jul;104(1):24-8.

Remarkable advances in care for early pregnancy loss (EPL) have occurred over the past several years. Misoprostol with mifepristone pretreatment is now the gold standard for medical management after recent research showed that this regimen improves both the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of medical management.1 Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)’s portability, effectiveness, and safety ensure that providers can offer procedural EPL management in almost any clinical setting. Medication management and in-office uterine aspiration are two evidence-based options for EPL management that may increase access for the 25% of pregnant women who experience EPL. Unfortunately, many women do not have access to either option. Equitable access to early pregnancy loss management can be achieved by expanding access to mifepristone and office-based MVA.

However, access to mifepristone and initiating office-based MVA is challenging. Mifepristone is one of several medications regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Management Strategies (REMS) program.2

The REMS guidelines restrict clinicians in prescribing and dispensing mifepristone, including the key provision that mifepristone may be dispensed only in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals. Clinicians cannot write a prescription for mifepristone for a patient to pick up at the pharmacy. Efforts are underway to roll back the REMS. Barriers to office-based MVA include time, culture shift among staff, gathering equipment, and creating protocols. Clinicians can improve access to EPL management in a variety of ways:

- MVA training: Ob.gyns. who lack training in MVA use can take advantage of several programs designed to teach the skill to clinicians, including programs such as Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management (TEAMM).3,4 MVA is easy to learn for ob.gyns. and procedural complications are uncommon. In the office setting, complications requiring transfer to a higher level of care are rare.5 With adequate training, whether during residency or afterward, ob.gyns. can learn to safely and effectively use MVA for procedural EPL management in the office and in the emergency department.

- Partnerships with pharmacists to reduce barriers to mifepristone: Ob.gyns. working in a variety of clinical settings, including independent clinics, critical access hospitals, community hospitals, and academic medical centers, have worked closely with on-site pharmacists to place mifepristone on their practice sites’ formularies.6 These ob.gyn.–pharmacist collaborations often require explanations to institutional Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees of the benefits of mifepristone to patients, detailed indications for mifepristone’s use, and methods to secure mifepristone on site.