User login

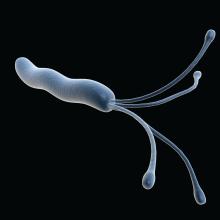

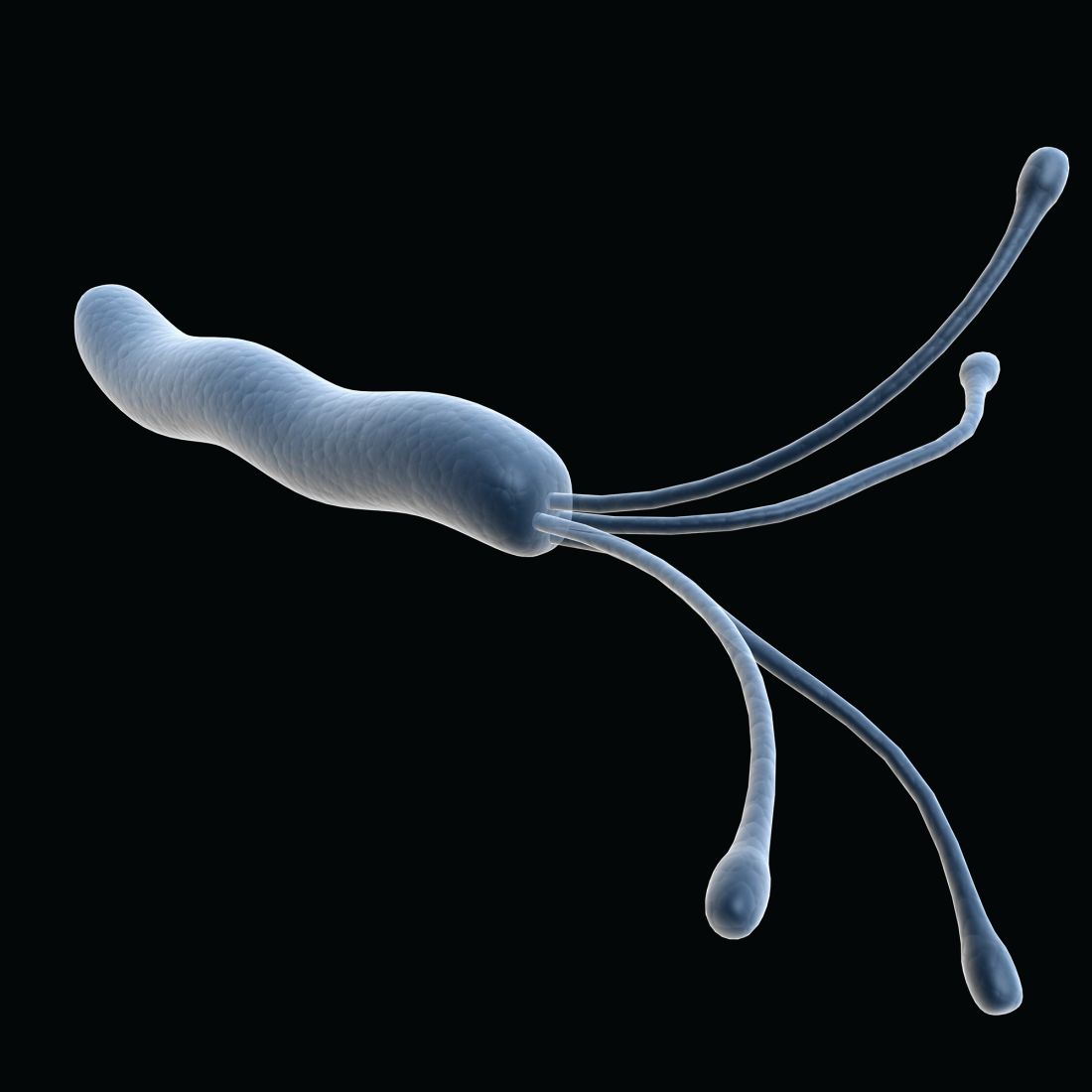

Gastric cancer: Family history–based H. pylori strategy would be cost effective

Testing for and treating Helicobacter pylori infection among individuals with a family history of gastric cancer could be a cost-effective strategy in the United States, according to a new model published in the journal Gastroenterology.

As many as 10% of gastric cancers aggregate within families, though just why this happens is unclear, according to Sheila D. Rustgi, MD, and colleagues. Shared environmental or genetic factors, or combinations of both, may be responsible. First-degree family history and H. pylori infection each raise gastric cancer risk by roughly 2.5-fold.

In the United States, universal screening for H. pylori infection is not currently recommended, but some studies have suggested a possible benefit in some high-risk populations. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines suggest that a patient’s family history should be a factor when considering surveillance strategies for intestinal metaplasia.

Furthermore, a study by Il Ju Choi, MD, and colleagues in 2020 showed that H. pylori treatment with bismuth-based quadruple therapy reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 73% among individuals with a first-degree relative who had gastric cancer. The combination included a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days.

“We hypothesize that, given the dramatic reduction in GC demonstrated by Choi et al., that the screening strategy can be a cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Rustgi and colleagues wrote.

In the new study, the researchers used a Markov state-transition mode, employing a hypothetical cohort of 40-year-old U.S. men and women with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. It simulated a follow-up period of 60 years or until death. The model assumed a 7-day treatment with triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin) followed by a 14-day treatment period with quadruple therapy if needed. Although the model was analyzed from the U.S. perspective, the trial that informed the risk reduction was performed in a South Korean population.

No screening had a cost of $2,694.09 and resulted in 21.95 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). 13C-Urea Breath Test screening had a cost of $2,105.28 and led to 22.37 QALYs. Stool antigen testing had a cost of $2,126.00 and yielded 22.30 QALYs.

In the no-screening group, an estimated 2.04% of patients would develop gastric cancer, and 1.82% would die of it. With screening, the frequency of gastric cancer dropped to 1.59%-1.65%, with a gastric cancer mortality rate of 1.41%-1.46%. Overall, screening was modeled to lead to a 19.1%-22.0% risk reduction.

The researchers validated their model by an assumption of an H. pylori infection rate of 100% and then compared the results of the model to the outcome of the study by Dr. Choi and colleagues. In the trial, there was a 55% reduction in gastric cancer among treated patients at a median of 9 years of follow-up. Those who had successful eradication of H. pylori had a 73% reduction. The new model estimated reductions from a testing and treatment strategy of 53.3%-64.5%.

The findings aren’t surprising, according to Joseph Jennings, MD, of the department of medicine at Georgetown University, Washington, and director of the Center for GI Bleeding at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “Even eliminating one person getting gastric cancer, where they will then need major surgery, chemotherapy, all these very expensive interventions [is important],” said Dr. Jennings. “We have very efficient ways to test for these things that don’t involve endoscopy.”

One potential caveat to identifying and treating H. pylori infection is whether elimination of H. pylori may lead to some adverse effects. Some patients can experience increased acid reflux as a result, while others suffer no ill effects. “But when you’re dealing with the alternative, which is stomach cancer, those negatives would have to stack up really, really high to outweigh the positives of preventing a cancer that’s really hard to treat,” said Dr. Jennings.

Dr. Jennings pointed out that the model also projected testing and an intervention conducted in a South Korean population, and extrapolated it to a U.S. population, where the incidence of gastric cancer is lower. “There definitely are some questions about how well it would translate if applied to the general United States population,” said Dr. Jennings.

That question could prompt researchers to conduct a U.S.-based study modeled after the test and treat study in South Korea to see if the regimen produced similar results. The model should add weight to that argument, said Dr. Jennings: “This is raising the point that, at least from an intellectual level, it might be worth now designing the study to see if it works in our population,” said Dr. Jennings.

The authors and Dr. Jennings have no relevant financial disclosures.

Testing for and treating Helicobacter pylori infection among individuals with a family history of gastric cancer could be a cost-effective strategy in the United States, according to a new model published in the journal Gastroenterology.

As many as 10% of gastric cancers aggregate within families, though just why this happens is unclear, according to Sheila D. Rustgi, MD, and colleagues. Shared environmental or genetic factors, or combinations of both, may be responsible. First-degree family history and H. pylori infection each raise gastric cancer risk by roughly 2.5-fold.

In the United States, universal screening for H. pylori infection is not currently recommended, but some studies have suggested a possible benefit in some high-risk populations. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines suggest that a patient’s family history should be a factor when considering surveillance strategies for intestinal metaplasia.

Furthermore, a study by Il Ju Choi, MD, and colleagues in 2020 showed that H. pylori treatment with bismuth-based quadruple therapy reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 73% among individuals with a first-degree relative who had gastric cancer. The combination included a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days.

“We hypothesize that, given the dramatic reduction in GC demonstrated by Choi et al., that the screening strategy can be a cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Rustgi and colleagues wrote.

In the new study, the researchers used a Markov state-transition mode, employing a hypothetical cohort of 40-year-old U.S. men and women with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. It simulated a follow-up period of 60 years or until death. The model assumed a 7-day treatment with triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin) followed by a 14-day treatment period with quadruple therapy if needed. Although the model was analyzed from the U.S. perspective, the trial that informed the risk reduction was performed in a South Korean population.

No screening had a cost of $2,694.09 and resulted in 21.95 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). 13C-Urea Breath Test screening had a cost of $2,105.28 and led to 22.37 QALYs. Stool antigen testing had a cost of $2,126.00 and yielded 22.30 QALYs.

In the no-screening group, an estimated 2.04% of patients would develop gastric cancer, and 1.82% would die of it. With screening, the frequency of gastric cancer dropped to 1.59%-1.65%, with a gastric cancer mortality rate of 1.41%-1.46%. Overall, screening was modeled to lead to a 19.1%-22.0% risk reduction.

The researchers validated their model by an assumption of an H. pylori infection rate of 100% and then compared the results of the model to the outcome of the study by Dr. Choi and colleagues. In the trial, there was a 55% reduction in gastric cancer among treated patients at a median of 9 years of follow-up. Those who had successful eradication of H. pylori had a 73% reduction. The new model estimated reductions from a testing and treatment strategy of 53.3%-64.5%.

The findings aren’t surprising, according to Joseph Jennings, MD, of the department of medicine at Georgetown University, Washington, and director of the Center for GI Bleeding at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “Even eliminating one person getting gastric cancer, where they will then need major surgery, chemotherapy, all these very expensive interventions [is important],” said Dr. Jennings. “We have very efficient ways to test for these things that don’t involve endoscopy.”

One potential caveat to identifying and treating H. pylori infection is whether elimination of H. pylori may lead to some adverse effects. Some patients can experience increased acid reflux as a result, while others suffer no ill effects. “But when you’re dealing with the alternative, which is stomach cancer, those negatives would have to stack up really, really high to outweigh the positives of preventing a cancer that’s really hard to treat,” said Dr. Jennings.

Dr. Jennings pointed out that the model also projected testing and an intervention conducted in a South Korean population, and extrapolated it to a U.S. population, where the incidence of gastric cancer is lower. “There definitely are some questions about how well it would translate if applied to the general United States population,” said Dr. Jennings.

That question could prompt researchers to conduct a U.S.-based study modeled after the test and treat study in South Korea to see if the regimen produced similar results. The model should add weight to that argument, said Dr. Jennings: “This is raising the point that, at least from an intellectual level, it might be worth now designing the study to see if it works in our population,” said Dr. Jennings.

The authors and Dr. Jennings have no relevant financial disclosures.

Testing for and treating Helicobacter pylori infection among individuals with a family history of gastric cancer could be a cost-effective strategy in the United States, according to a new model published in the journal Gastroenterology.

As many as 10% of gastric cancers aggregate within families, though just why this happens is unclear, according to Sheila D. Rustgi, MD, and colleagues. Shared environmental or genetic factors, or combinations of both, may be responsible. First-degree family history and H. pylori infection each raise gastric cancer risk by roughly 2.5-fold.

In the United States, universal screening for H. pylori infection is not currently recommended, but some studies have suggested a possible benefit in some high-risk populations. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines suggest that a patient’s family history should be a factor when considering surveillance strategies for intestinal metaplasia.

Furthermore, a study by Il Ju Choi, MD, and colleagues in 2020 showed that H. pylori treatment with bismuth-based quadruple therapy reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 73% among individuals with a first-degree relative who had gastric cancer. The combination included a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days.

“We hypothesize that, given the dramatic reduction in GC demonstrated by Choi et al., that the screening strategy can be a cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Rustgi and colleagues wrote.

In the new study, the researchers used a Markov state-transition mode, employing a hypothetical cohort of 40-year-old U.S. men and women with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. It simulated a follow-up period of 60 years or until death. The model assumed a 7-day treatment with triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin) followed by a 14-day treatment period with quadruple therapy if needed. Although the model was analyzed from the U.S. perspective, the trial that informed the risk reduction was performed in a South Korean population.

No screening had a cost of $2,694.09 and resulted in 21.95 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). 13C-Urea Breath Test screening had a cost of $2,105.28 and led to 22.37 QALYs. Stool antigen testing had a cost of $2,126.00 and yielded 22.30 QALYs.

In the no-screening group, an estimated 2.04% of patients would develop gastric cancer, and 1.82% would die of it. With screening, the frequency of gastric cancer dropped to 1.59%-1.65%, with a gastric cancer mortality rate of 1.41%-1.46%. Overall, screening was modeled to lead to a 19.1%-22.0% risk reduction.

The researchers validated their model by an assumption of an H. pylori infection rate of 100% and then compared the results of the model to the outcome of the study by Dr. Choi and colleagues. In the trial, there was a 55% reduction in gastric cancer among treated patients at a median of 9 years of follow-up. Those who had successful eradication of H. pylori had a 73% reduction. The new model estimated reductions from a testing and treatment strategy of 53.3%-64.5%.

The findings aren’t surprising, according to Joseph Jennings, MD, of the department of medicine at Georgetown University, Washington, and director of the Center for GI Bleeding at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “Even eliminating one person getting gastric cancer, where they will then need major surgery, chemotherapy, all these very expensive interventions [is important],” said Dr. Jennings. “We have very efficient ways to test for these things that don’t involve endoscopy.”

One potential caveat to identifying and treating H. pylori infection is whether elimination of H. pylori may lead to some adverse effects. Some patients can experience increased acid reflux as a result, while others suffer no ill effects. “But when you’re dealing with the alternative, which is stomach cancer, those negatives would have to stack up really, really high to outweigh the positives of preventing a cancer that’s really hard to treat,” said Dr. Jennings.

Dr. Jennings pointed out that the model also projected testing and an intervention conducted in a South Korean population, and extrapolated it to a U.S. population, where the incidence of gastric cancer is lower. “There definitely are some questions about how well it would translate if applied to the general United States population,” said Dr. Jennings.

That question could prompt researchers to conduct a U.S.-based study modeled after the test and treat study in South Korea to see if the regimen produced similar results. The model should add weight to that argument, said Dr. Jennings: “This is raising the point that, at least from an intellectual level, it might be worth now designing the study to see if it works in our population,” said Dr. Jennings.

The authors and Dr. Jennings have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Buprenorphine offers a way to rise from the ashes of addiction

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physician is having a direct impact on alleviating patient suffering. On the other hand, one of the more difficult elements is a confrontational patient with unreasonable expectations or inappropriate demands. I have experienced both ends of the spectrum while engaging with patients who have opioid use disorder (OUD).

An untreated patient with OUD might provide an untruthful history, attempt to falsify exam findings, or even become threatening or abusive in an attempt to secure opiate pain medication. Managing a patient with OUD by providing buprenorphine treatment, however, is a completely different experience.

There is no controversy about the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Patients seeking it are not looking for inappropriate care but rather a treatment that is established as an unequivocal standard with proven results for better treatment outcomes1-3 and reduced mortality.4 Personally, I’ve found offering buprenorphine treatment to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practicing medicine. It is a real joy to witness people turn their lives around with meaningful outcomes such as gainful employment, eradication of hepatitis C, reconciliation of broken relationships, resolution of legal troubles, and long-term sobriety. Being a part of lives that are practically resurrected from the ashes of addiction by prescribing medicine is indeed an exceptional experience.

On April 28, 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services provided notice for immediate action allowing for any DEA-licensed provider to obtain an X-waiver to treat 30 active patients without educational prerequisite or certification of behavioral health referral capacity.5 The X-waiver requirements were reduced, as outlined by SAMSHA,6 to a simple online notice of intent7 that can be completed in less than 5 minutes.

I encourage my colleagues to obtain the X-waiver by the simplified process, start prescribing buprenorphine, and be a part of the solution to the opioid epidemic. Of course, there will be struggles and lessons learned, but these can most certainly be eclipsed by a focus on the rewarding experience of restoring wholeness to the lives of many patients.

Aaron Newcomb, DO

Carbondale, IL

1. Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, et al. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015

2. Evans EA, Zhu Y, Yoo C, et al. Criminal justice outcomes over 5 years after randomization to buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1396-1404. doi: 10.1111/add.14620

3. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane. Published February 6, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.cochrane.org/CD002207/ADDICTN_buprenorphine-maintenance-versus-placebo-or-methadone-maintenance-for-opioid-dependence

4. Methadone and buprenorphine reduce risk of death after opioid overdose. National Institutes of Health. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/methadone-buprenorphine-reduce-risk-death-after-opioid-overdose

5. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

6. US Department of Health & Human Services. Become a buprenorphine waivered practitioner. SAMHSA. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner

7. Buprenorphine waiver notification. SAMHSA. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/forms/select-practitioner-type.php

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physician is having a direct impact on alleviating patient suffering. On the other hand, one of the more difficult elements is a confrontational patient with unreasonable expectations or inappropriate demands. I have experienced both ends of the spectrum while engaging with patients who have opioid use disorder (OUD).

An untreated patient with OUD might provide an untruthful history, attempt to falsify exam findings, or even become threatening or abusive in an attempt to secure opiate pain medication. Managing a patient with OUD by providing buprenorphine treatment, however, is a completely different experience.

There is no controversy about the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Patients seeking it are not looking for inappropriate care but rather a treatment that is established as an unequivocal standard with proven results for better treatment outcomes1-3 and reduced mortality.4 Personally, I’ve found offering buprenorphine treatment to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practicing medicine. It is a real joy to witness people turn their lives around with meaningful outcomes such as gainful employment, eradication of hepatitis C, reconciliation of broken relationships, resolution of legal troubles, and long-term sobriety. Being a part of lives that are practically resurrected from the ashes of addiction by prescribing medicine is indeed an exceptional experience.

On April 28, 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services provided notice for immediate action allowing for any DEA-licensed provider to obtain an X-waiver to treat 30 active patients without educational prerequisite or certification of behavioral health referral capacity.5 The X-waiver requirements were reduced, as outlined by SAMSHA,6 to a simple online notice of intent7 that can be completed in less than 5 minutes.

I encourage my colleagues to obtain the X-waiver by the simplified process, start prescribing buprenorphine, and be a part of the solution to the opioid epidemic. Of course, there will be struggles and lessons learned, but these can most certainly be eclipsed by a focus on the rewarding experience of restoring wholeness to the lives of many patients.

Aaron Newcomb, DO

Carbondale, IL

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physician is having a direct impact on alleviating patient suffering. On the other hand, one of the more difficult elements is a confrontational patient with unreasonable expectations or inappropriate demands. I have experienced both ends of the spectrum while engaging with patients who have opioid use disorder (OUD).

An untreated patient with OUD might provide an untruthful history, attempt to falsify exam findings, or even become threatening or abusive in an attempt to secure opiate pain medication. Managing a patient with OUD by providing buprenorphine treatment, however, is a completely different experience.

There is no controversy about the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Patients seeking it are not looking for inappropriate care but rather a treatment that is established as an unequivocal standard with proven results for better treatment outcomes1-3 and reduced mortality.4 Personally, I’ve found offering buprenorphine treatment to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practicing medicine. It is a real joy to witness people turn their lives around with meaningful outcomes such as gainful employment, eradication of hepatitis C, reconciliation of broken relationships, resolution of legal troubles, and long-term sobriety. Being a part of lives that are practically resurrected from the ashes of addiction by prescribing medicine is indeed an exceptional experience.

On April 28, 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services provided notice for immediate action allowing for any DEA-licensed provider to obtain an X-waiver to treat 30 active patients without educational prerequisite or certification of behavioral health referral capacity.5 The X-waiver requirements were reduced, as outlined by SAMSHA,6 to a simple online notice of intent7 that can be completed in less than 5 minutes.

I encourage my colleagues to obtain the X-waiver by the simplified process, start prescribing buprenorphine, and be a part of the solution to the opioid epidemic. Of course, there will be struggles and lessons learned, but these can most certainly be eclipsed by a focus on the rewarding experience of restoring wholeness to the lives of many patients.

Aaron Newcomb, DO

Carbondale, IL

1. Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, et al. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015

2. Evans EA, Zhu Y, Yoo C, et al. Criminal justice outcomes over 5 years after randomization to buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1396-1404. doi: 10.1111/add.14620

3. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane. Published February 6, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.cochrane.org/CD002207/ADDICTN_buprenorphine-maintenance-versus-placebo-or-methadone-maintenance-for-opioid-dependence

4. Methadone and buprenorphine reduce risk of death after opioid overdose. National Institutes of Health. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/methadone-buprenorphine-reduce-risk-death-after-opioid-overdose

5. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

6. US Department of Health & Human Services. Become a buprenorphine waivered practitioner. SAMHSA. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner

7. Buprenorphine waiver notification. SAMHSA. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/forms/select-practitioner-type.php

1. Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, et al. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015

2. Evans EA, Zhu Y, Yoo C, et al. Criminal justice outcomes over 5 years after randomization to buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1396-1404. doi: 10.1111/add.14620

3. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane. Published February 6, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.cochrane.org/CD002207/ADDICTN_buprenorphine-maintenance-versus-placebo-or-methadone-maintenance-for-opioid-dependence

4. Methadone and buprenorphine reduce risk of death after opioid overdose. National Institutes of Health. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/methadone-buprenorphine-reduce-risk-death-after-opioid-overdose

5. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

6. US Department of Health & Human Services. Become a buprenorphine waivered practitioner. SAMHSA. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner

7. Buprenorphine waiver notification. SAMHSA. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/forms/select-practitioner-type.php

Successful Recruitment of VA Patients in Precision Medicine Research Through Passive Recruitment Efforts

Background

We sought to evaluate passive recruitment efforts of VA patients into a precision medicine research program. Access to clinical trials and other research opportunities is important to discovering new disease treatments and better ways to detect, diagnose, and reduce disease risk. The WISDOM (Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of risk) Study is a multi-site, pragmatic trial with webbased participation based at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) that aims to move breast cancer screening away from its current one-size-fitsall approach to one that is personalized based on each woman’s individual risk.

Methods

We created a hub and spoke recruitment model with the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) serving as the central hub of passive recruitment activities and eligible VA facilities that agreed to participate serving as the spoke recruitment sites. Eligible facilities had at least 3,000 women patients, VA clinical genetic services available, a site lead from the VA Women’s Health-Practice-Based Research Network, and mammography on site. Site participation involved permission for the research team to email eligible patients (women aged 40-74 without prior breast cancer diagnosis) about the WISDOM Study. We evaluated the effectiveness of the recruitment by assessing trends in enrollment and monitoring participation of VA patients in the WISDOM Study. Analysis: Pre/post frequencies of women consenting to participate in the WISDOM Study.

Results

From 5/24/2021 through 6/21/2021, we emailed 27,061 eligible VA patients from six participating VA facilities. Prior to the VA emailing, an average of 22 women per week consented to participating in the WISDOM Study and none were Veterans. After the first month of the VA emailing, an average of 186 women per week consented – a 7.5-fold increase. Additionally, during the first month of VA emailing, 81% of women registering with the WISDOM Study said they heard about the study from the VA.

Implications

The VA has recently approved of emailing as a method for recruiting research subjects. Our results demonstrate this is a feasible approach for precision medicine research, a growing area of research in VA and at academic affiliates.

Background

We sought to evaluate passive recruitment efforts of VA patients into a precision medicine research program. Access to clinical trials and other research opportunities is important to discovering new disease treatments and better ways to detect, diagnose, and reduce disease risk. The WISDOM (Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of risk) Study is a multi-site, pragmatic trial with webbased participation based at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) that aims to move breast cancer screening away from its current one-size-fitsall approach to one that is personalized based on each woman’s individual risk.

Methods

We created a hub and spoke recruitment model with the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) serving as the central hub of passive recruitment activities and eligible VA facilities that agreed to participate serving as the spoke recruitment sites. Eligible facilities had at least 3,000 women patients, VA clinical genetic services available, a site lead from the VA Women’s Health-Practice-Based Research Network, and mammography on site. Site participation involved permission for the research team to email eligible patients (women aged 40-74 without prior breast cancer diagnosis) about the WISDOM Study. We evaluated the effectiveness of the recruitment by assessing trends in enrollment and monitoring participation of VA patients in the WISDOM Study. Analysis: Pre/post frequencies of women consenting to participate in the WISDOM Study.

Results

From 5/24/2021 through 6/21/2021, we emailed 27,061 eligible VA patients from six participating VA facilities. Prior to the VA emailing, an average of 22 women per week consented to participating in the WISDOM Study and none were Veterans. After the first month of the VA emailing, an average of 186 women per week consented – a 7.5-fold increase. Additionally, during the first month of VA emailing, 81% of women registering with the WISDOM Study said they heard about the study from the VA.

Implications

The VA has recently approved of emailing as a method for recruiting research subjects. Our results demonstrate this is a feasible approach for precision medicine research, a growing area of research in VA and at academic affiliates.

Background

We sought to evaluate passive recruitment efforts of VA patients into a precision medicine research program. Access to clinical trials and other research opportunities is important to discovering new disease treatments and better ways to detect, diagnose, and reduce disease risk. The WISDOM (Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of risk) Study is a multi-site, pragmatic trial with webbased participation based at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) that aims to move breast cancer screening away from its current one-size-fitsall approach to one that is personalized based on each woman’s individual risk.

Methods

We created a hub and spoke recruitment model with the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) serving as the central hub of passive recruitment activities and eligible VA facilities that agreed to participate serving as the spoke recruitment sites. Eligible facilities had at least 3,000 women patients, VA clinical genetic services available, a site lead from the VA Women’s Health-Practice-Based Research Network, and mammography on site. Site participation involved permission for the research team to email eligible patients (women aged 40-74 without prior breast cancer diagnosis) about the WISDOM Study. We evaluated the effectiveness of the recruitment by assessing trends in enrollment and monitoring participation of VA patients in the WISDOM Study. Analysis: Pre/post frequencies of women consenting to participate in the WISDOM Study.

Results

From 5/24/2021 through 6/21/2021, we emailed 27,061 eligible VA patients from six participating VA facilities. Prior to the VA emailing, an average of 22 women per week consented to participating in the WISDOM Study and none were Veterans. After the first month of the VA emailing, an average of 186 women per week consented – a 7.5-fold increase. Additionally, during the first month of VA emailing, 81% of women registering with the WISDOM Study said they heard about the study from the VA.

Implications

The VA has recently approved of emailing as a method for recruiting research subjects. Our results demonstrate this is a feasible approach for precision medicine research, a growing area of research in VA and at academic affiliates.

New COVID-19 strain has reached the U.S.

Deadline, citing a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, said 26 residents and 20 workers tested positive for COVID-19 at a skilled care nursing home. The facility has 83 residents and 116 employees.

On March 1, 28 specimens that had been subjected to whole genome sequencing were found to have “mutations aligning with the R.1 lineage,” Deadline said.

About 90% of the facility’s residents and 52% of the staff had received two COVID vaccine doses, the CDC said. Because of the high vaccination rate, the finding raises concerns about “reduced protective immunity” in relation to the R.1 variant, the CDC said.

However, the nursing home case appears to show that the vaccine keeps most people from getting extremely sick, the CDC said. The vaccine was 86.5% protective against symptomatic illness among residents and 87.1% protective for employees.

“Compared with unvaccinated persons, vaccinated persons had reduced risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptomatic COVID-19,” the CDC said. The vaccination of nursing home residents and health care workers “is essential to reduce the risk for symptomatic COVID-19, as is continued focus on infection prevention and control practices,” the CDC said.

Since being reported in Kentucky, R.1 has been detected more than 10,000 times in the United States, Forbes reported, basing that number on entries in the GISAID SARS-CoV-2 database.

Overall, more than 42 million cases of COVID have been reported since the start of the pandemic.

Deadline reported that the R.1 strain was first detected in Japan in January among three members of one family. The family members had no history of traveling abroad, Deadline said, citing an National Institutes of Health report.

The CDC has not classified R.1 as a variant of concern yet but noted it has “several mutations of importance” and “demonstrates evidence of increasing virus transmissibility.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Deadline, citing a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, said 26 residents and 20 workers tested positive for COVID-19 at a skilled care nursing home. The facility has 83 residents and 116 employees.

On March 1, 28 specimens that had been subjected to whole genome sequencing were found to have “mutations aligning with the R.1 lineage,” Deadline said.

About 90% of the facility’s residents and 52% of the staff had received two COVID vaccine doses, the CDC said. Because of the high vaccination rate, the finding raises concerns about “reduced protective immunity” in relation to the R.1 variant, the CDC said.

However, the nursing home case appears to show that the vaccine keeps most people from getting extremely sick, the CDC said. The vaccine was 86.5% protective against symptomatic illness among residents and 87.1% protective for employees.

“Compared with unvaccinated persons, vaccinated persons had reduced risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptomatic COVID-19,” the CDC said. The vaccination of nursing home residents and health care workers “is essential to reduce the risk for symptomatic COVID-19, as is continued focus on infection prevention and control practices,” the CDC said.

Since being reported in Kentucky, R.1 has been detected more than 10,000 times in the United States, Forbes reported, basing that number on entries in the GISAID SARS-CoV-2 database.

Overall, more than 42 million cases of COVID have been reported since the start of the pandemic.

Deadline reported that the R.1 strain was first detected in Japan in January among three members of one family. The family members had no history of traveling abroad, Deadline said, citing an National Institutes of Health report.

The CDC has not classified R.1 as a variant of concern yet but noted it has “several mutations of importance” and “demonstrates evidence of increasing virus transmissibility.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Deadline, citing a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, said 26 residents and 20 workers tested positive for COVID-19 at a skilled care nursing home. The facility has 83 residents and 116 employees.

On March 1, 28 specimens that had been subjected to whole genome sequencing were found to have “mutations aligning with the R.1 lineage,” Deadline said.

About 90% of the facility’s residents and 52% of the staff had received two COVID vaccine doses, the CDC said. Because of the high vaccination rate, the finding raises concerns about “reduced protective immunity” in relation to the R.1 variant, the CDC said.

However, the nursing home case appears to show that the vaccine keeps most people from getting extremely sick, the CDC said. The vaccine was 86.5% protective against symptomatic illness among residents and 87.1% protective for employees.

“Compared with unvaccinated persons, vaccinated persons had reduced risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptomatic COVID-19,” the CDC said. The vaccination of nursing home residents and health care workers “is essential to reduce the risk for symptomatic COVID-19, as is continued focus on infection prevention and control practices,” the CDC said.

Since being reported in Kentucky, R.1 has been detected more than 10,000 times in the United States, Forbes reported, basing that number on entries in the GISAID SARS-CoV-2 database.

Overall, more than 42 million cases of COVID have been reported since the start of the pandemic.

Deadline reported that the R.1 strain was first detected in Japan in January among three members of one family. The family members had no history of traveling abroad, Deadline said, citing an National Institutes of Health report.

The CDC has not classified R.1 as a variant of concern yet but noted it has “several mutations of importance” and “demonstrates evidence of increasing virus transmissibility.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Sexual assault in women tied to increased stroke, dementia risk

Traumatic experiences, especially sexual assault, may put women at greater risk for poor brain health.

In the Ms Brain study, middle-aged women with trauma exposure had a greater volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) than those without trauma. In addition, the differences persisted even after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

WMHs are “an important indicator of small vessel disease in the brain and have been linked to future stroke risk, dementia risk, and mortality,” lead investigator Rebecca Thurston, PhD, from the University of Pittsburgh, told this news organization.

“What I take from this is, really, that sexual assault has implications for women’s health, far beyond exclusively mental health outcomes, but also for their cardiovascular health, as we have shown in other work and for their stroke and dementia risk as we are seeing in the present work,” Dr. Thurston added.

The study was presented at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., and has been accepted for publication in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior.

Beyond the usual suspects

As part of the study, 145 women (mean age, 59 years) free of clinical cardiovascular disease, stroke, or dementia provided their medical history, including history of traumatic experiences, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder and underwent magnetic resonance brain imaging for WMHs.

More than two-thirds (68%) of the women reported at least one trauma, most commonly sexual assault (23%).

In multivariate analysis, women with trauma exposure had greater WMH volume than women without trauma (P = .01), with sexual assault most strongly associated with greater WMH volume (P = .02).

The associations persisted after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

“A history of sexual assault was particularly related to white matter hyperintensities in the parietal lobe, and these kinds of white matter hyperintensities have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in a fairly pronounced way,” Dr. Thurston said.

“When we think about risk factors for stroke, dementia, we need to think beyond exclusively our usual suspects and also think about women [who experienced] psychological trauma and experienced sexual assault in particular. So ask about it and consider it part of your screening regimen,” she added.

‘Burgeoning’ literature

Commenting on the findings, Charles Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, and director of its Institute for Early Life Adversity Research, said the research adds to the “burgeoning literature on the long term neurobiological consequences of trauma and more specifically, sexual abuse, on brain imaging measures.”

“Our group and others reported several years ago that patients with mood disorders, more specifically bipolar disorder and major depression, had higher rates of WMH than matched controls. Those older studies did not control for a history of early life adversity such as childhood maltreatment,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

“In addition to this finding of increased WMH in subjects exposed to trauma is a very large literature documenting other central nervous system (CNS) changes in this population, including cortical thinning in certain brain areas and clearly an emerging finding that different forms of childhood maltreatment are associated with quite distinct structural brain alterations in adulthood,” he noted.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traumatic experiences, especially sexual assault, may put women at greater risk for poor brain health.

In the Ms Brain study, middle-aged women with trauma exposure had a greater volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) than those without trauma. In addition, the differences persisted even after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

WMHs are “an important indicator of small vessel disease in the brain and have been linked to future stroke risk, dementia risk, and mortality,” lead investigator Rebecca Thurston, PhD, from the University of Pittsburgh, told this news organization.

“What I take from this is, really, that sexual assault has implications for women’s health, far beyond exclusively mental health outcomes, but also for their cardiovascular health, as we have shown in other work and for their stroke and dementia risk as we are seeing in the present work,” Dr. Thurston added.

The study was presented at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., and has been accepted for publication in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior.

Beyond the usual suspects

As part of the study, 145 women (mean age, 59 years) free of clinical cardiovascular disease, stroke, or dementia provided their medical history, including history of traumatic experiences, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder and underwent magnetic resonance brain imaging for WMHs.

More than two-thirds (68%) of the women reported at least one trauma, most commonly sexual assault (23%).

In multivariate analysis, women with trauma exposure had greater WMH volume than women without trauma (P = .01), with sexual assault most strongly associated with greater WMH volume (P = .02).

The associations persisted after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

“A history of sexual assault was particularly related to white matter hyperintensities in the parietal lobe, and these kinds of white matter hyperintensities have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in a fairly pronounced way,” Dr. Thurston said.

“When we think about risk factors for stroke, dementia, we need to think beyond exclusively our usual suspects and also think about women [who experienced] psychological trauma and experienced sexual assault in particular. So ask about it and consider it part of your screening regimen,” she added.

‘Burgeoning’ literature

Commenting on the findings, Charles Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, and director of its Institute for Early Life Adversity Research, said the research adds to the “burgeoning literature on the long term neurobiological consequences of trauma and more specifically, sexual abuse, on brain imaging measures.”

“Our group and others reported several years ago that patients with mood disorders, more specifically bipolar disorder and major depression, had higher rates of WMH than matched controls. Those older studies did not control for a history of early life adversity such as childhood maltreatment,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

“In addition to this finding of increased WMH in subjects exposed to trauma is a very large literature documenting other central nervous system (CNS) changes in this population, including cortical thinning in certain brain areas and clearly an emerging finding that different forms of childhood maltreatment are associated with quite distinct structural brain alterations in adulthood,” he noted.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traumatic experiences, especially sexual assault, may put women at greater risk for poor brain health.

In the Ms Brain study, middle-aged women with trauma exposure had a greater volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) than those without trauma. In addition, the differences persisted even after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

WMHs are “an important indicator of small vessel disease in the brain and have been linked to future stroke risk, dementia risk, and mortality,” lead investigator Rebecca Thurston, PhD, from the University of Pittsburgh, told this news organization.

“What I take from this is, really, that sexual assault has implications for women’s health, far beyond exclusively mental health outcomes, but also for their cardiovascular health, as we have shown in other work and for their stroke and dementia risk as we are seeing in the present work,” Dr. Thurston added.

The study was presented at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., and has been accepted for publication in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior.

Beyond the usual suspects

As part of the study, 145 women (mean age, 59 years) free of clinical cardiovascular disease, stroke, or dementia provided their medical history, including history of traumatic experiences, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder and underwent magnetic resonance brain imaging for WMHs.

More than two-thirds (68%) of the women reported at least one trauma, most commonly sexual assault (23%).

In multivariate analysis, women with trauma exposure had greater WMH volume than women without trauma (P = .01), with sexual assault most strongly associated with greater WMH volume (P = .02).

The associations persisted after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

“A history of sexual assault was particularly related to white matter hyperintensities in the parietal lobe, and these kinds of white matter hyperintensities have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in a fairly pronounced way,” Dr. Thurston said.

“When we think about risk factors for stroke, dementia, we need to think beyond exclusively our usual suspects and also think about women [who experienced] psychological trauma and experienced sexual assault in particular. So ask about it and consider it part of your screening regimen,” she added.

‘Burgeoning’ literature

Commenting on the findings, Charles Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, and director of its Institute for Early Life Adversity Research, said the research adds to the “burgeoning literature on the long term neurobiological consequences of trauma and more specifically, sexual abuse, on brain imaging measures.”

“Our group and others reported several years ago that patients with mood disorders, more specifically bipolar disorder and major depression, had higher rates of WMH than matched controls. Those older studies did not control for a history of early life adversity such as childhood maltreatment,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

“In addition to this finding of increased WMH in subjects exposed to trauma is a very large literature documenting other central nervous system (CNS) changes in this population, including cortical thinning in certain brain areas and clearly an emerging finding that different forms of childhood maltreatment are associated with quite distinct structural brain alterations in adulthood,” he noted.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy may protect baby, too

Women who receive COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy pass antibodies to their babies, which could protect newborns from the disease, research has shown.

.

Researchers with New York University Langone Health conducted a study that included pregnant women who had received at least one dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna) by June 4.

All neonates had antibodies to the spike protein at high titers, the researchers found.

Unlike similar prior studies, the researchers also looked for antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, which would have indicated the presence of antibodies from natural COVID-19 infection. They did not detect antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, and the lack of these antibodies suggests that the antibodies to the spike protein resulted from vaccination and not from prior infection, the researchers said.

The participants had a median time from completion of the vaccine series to delivery of 13 weeks. The study was published online in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM.

“The presence of these anti-spike antibodies in the cord blood should, at least in theory, offer these newborns some degree of protection,” said study investigator Ashley S. Roman, MD, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at NYU Langone Health. “While the primary rationale for vaccination during pregnancy is to keep moms healthy and keep moms out of the hospital, the outstanding question to us was whether there is any fetal or neonatal benefit conferred by receiving the vaccine during pregnancy.”

Questions remain about the degree and durability of protection for newborns from these antibodies. An ongoing study, MOMI-VAX, aims to systematically measure antibody levels in mothers who receive COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy and in their babies over time.

The present study contributes welcome preliminary evidence suggesting a benefit to infants, said Emily Adhikari, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who was not involved in the study.

Still, “the main concern and our priority as obstetricians is to vaccinate pregnant women to protect them from severe or critical illness,” she said.

Although most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 recover, a significant portion of pregnant women get seriously sick, Dr. Adhikari said. “With this recent Delta surge, we are seeing more pregnant patients who are sicker,” said Dr. Adhikari, who has published research from one hospital describing this trend.

When weighing whether patients should receive COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy, the risks from infection have outweighed any risk from vaccination to such an extent that there is “not a comparison to make,” Dr. Adhikari said. “The risks of the infection are so much higher.

“For me, it is a matter of making sure that my patient understands that we have really good safety data on these vaccines and there is no reason to think that a pregnant person would be harmed by them. On the contrary, the benefit is to protect and maybe even save your life,” Dr. Adhikari said. “And now we have more evidence that the fetus may also benefit.”

The rationale for vaccinations during pregnancy can vary, Dr. Roman said. Flu shots in pregnancy mainly are intended to protect the mother, though they confer protection for newborns as well. With the whooping cough vaccine given in the third trimester, however, the primary aim is to protect the baby from whooping cough in the first months of life, Dr. Roman said.

“I think it is really important for pregnant women to understand that antibodies crossing the placenta is a good thing,” she added.

As patients who already have received COVID-19 vaccines become pregnant and may become eligible for a booster dose, Dr. Adhikari will offer it, she said, though she has confidence in the protection provided by the initial immune response.

Dr. Roman and Dr. Adhikari had no disclosures.

Women who receive COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy pass antibodies to their babies, which could protect newborns from the disease, research has shown.

.

Researchers with New York University Langone Health conducted a study that included pregnant women who had received at least one dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna) by June 4.

All neonates had antibodies to the spike protein at high titers, the researchers found.

Unlike similar prior studies, the researchers also looked for antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, which would have indicated the presence of antibodies from natural COVID-19 infection. They did not detect antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, and the lack of these antibodies suggests that the antibodies to the spike protein resulted from vaccination and not from prior infection, the researchers said.

The participants had a median time from completion of the vaccine series to delivery of 13 weeks. The study was published online in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM.

“The presence of these anti-spike antibodies in the cord blood should, at least in theory, offer these newborns some degree of protection,” said study investigator Ashley S. Roman, MD, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at NYU Langone Health. “While the primary rationale for vaccination during pregnancy is to keep moms healthy and keep moms out of the hospital, the outstanding question to us was whether there is any fetal or neonatal benefit conferred by receiving the vaccine during pregnancy.”

Questions remain about the degree and durability of protection for newborns from these antibodies. An ongoing study, MOMI-VAX, aims to systematically measure antibody levels in mothers who receive COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy and in their babies over time.

The present study contributes welcome preliminary evidence suggesting a benefit to infants, said Emily Adhikari, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who was not involved in the study.

Still, “the main concern and our priority as obstetricians is to vaccinate pregnant women to protect them from severe or critical illness,” she said.

Although most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 recover, a significant portion of pregnant women get seriously sick, Dr. Adhikari said. “With this recent Delta surge, we are seeing more pregnant patients who are sicker,” said Dr. Adhikari, who has published research from one hospital describing this trend.

When weighing whether patients should receive COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy, the risks from infection have outweighed any risk from vaccination to such an extent that there is “not a comparison to make,” Dr. Adhikari said. “The risks of the infection are so much higher.

“For me, it is a matter of making sure that my patient understands that we have really good safety data on these vaccines and there is no reason to think that a pregnant person would be harmed by them. On the contrary, the benefit is to protect and maybe even save your life,” Dr. Adhikari said. “And now we have more evidence that the fetus may also benefit.”

The rationale for vaccinations during pregnancy can vary, Dr. Roman said. Flu shots in pregnancy mainly are intended to protect the mother, though they confer protection for newborns as well. With the whooping cough vaccine given in the third trimester, however, the primary aim is to protect the baby from whooping cough in the first months of life, Dr. Roman said.

“I think it is really important for pregnant women to understand that antibodies crossing the placenta is a good thing,” she added.

As patients who already have received COVID-19 vaccines become pregnant and may become eligible for a booster dose, Dr. Adhikari will offer it, she said, though she has confidence in the protection provided by the initial immune response.

Dr. Roman and Dr. Adhikari had no disclosures.

Women who receive COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy pass antibodies to their babies, which could protect newborns from the disease, research has shown.

.

Researchers with New York University Langone Health conducted a study that included pregnant women who had received at least one dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna) by June 4.

All neonates had antibodies to the spike protein at high titers, the researchers found.

Unlike similar prior studies, the researchers also looked for antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, which would have indicated the presence of antibodies from natural COVID-19 infection. They did not detect antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, and the lack of these antibodies suggests that the antibodies to the spike protein resulted from vaccination and not from prior infection, the researchers said.

The participants had a median time from completion of the vaccine series to delivery of 13 weeks. The study was published online in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM.

“The presence of these anti-spike antibodies in the cord blood should, at least in theory, offer these newborns some degree of protection,” said study investigator Ashley S. Roman, MD, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at NYU Langone Health. “While the primary rationale for vaccination during pregnancy is to keep moms healthy and keep moms out of the hospital, the outstanding question to us was whether there is any fetal or neonatal benefit conferred by receiving the vaccine during pregnancy.”

Questions remain about the degree and durability of protection for newborns from these antibodies. An ongoing study, MOMI-VAX, aims to systematically measure antibody levels in mothers who receive COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy and in their babies over time.

The present study contributes welcome preliminary evidence suggesting a benefit to infants, said Emily Adhikari, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who was not involved in the study.

Still, “the main concern and our priority as obstetricians is to vaccinate pregnant women to protect them from severe or critical illness,” she said.

Although most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 recover, a significant portion of pregnant women get seriously sick, Dr. Adhikari said. “With this recent Delta surge, we are seeing more pregnant patients who are sicker,” said Dr. Adhikari, who has published research from one hospital describing this trend.

When weighing whether patients should receive COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy, the risks from infection have outweighed any risk from vaccination to such an extent that there is “not a comparison to make,” Dr. Adhikari said. “The risks of the infection are so much higher.

“For me, it is a matter of making sure that my patient understands that we have really good safety data on these vaccines and there is no reason to think that a pregnant person would be harmed by them. On the contrary, the benefit is to protect and maybe even save your life,” Dr. Adhikari said. “And now we have more evidence that the fetus may also benefit.”

The rationale for vaccinations during pregnancy can vary, Dr. Roman said. Flu shots in pregnancy mainly are intended to protect the mother, though they confer protection for newborns as well. With the whooping cough vaccine given in the third trimester, however, the primary aim is to protect the baby from whooping cough in the first months of life, Dr. Roman said.

“I think it is really important for pregnant women to understand that antibodies crossing the placenta is a good thing,” she added.

As patients who already have received COVID-19 vaccines become pregnant and may become eligible for a booster dose, Dr. Adhikari will offer it, she said, though she has confidence in the protection provided by the initial immune response.

Dr. Roman and Dr. Adhikari had no disclosures.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY MFM

Smart watch glucose monitoring on the horizon

Earlier this year, technology news sites reported that the Apple Watch Series 7 and the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 were going to have integrated optical sensors for checking interstitial fluid glucose levels with no blood sampling needed. By the summer, new articles indicated that the glucose sensing watches would not be released this year for either Apple or Samsung.

For now, the newest technology available for monitoring glucose is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which involves a tiny sensor being inserted under the skin. The sensor tests glucose every few minutes, and a transmitter wirelessly sends the information to a monitor, which may be part of an insulin pump or a separate device. Some CGMs send information directly to a smartphone or tablet, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first CGM, which was only approved for downloading 3 days of data at a doctor’s office. Interestingly, the first real-time CGM device for patients to use on their own was a watch, the Glucowatch Biographer. Because of irritation and other issues, that watch never caught on. In 2006 and 2008, Dexcom and then Abbott released the first real-time CGMs that allowed patients to frequently check their own blood sugars.1,2

How CGM has advanced diabetes management

The advent of CGM has advanced the field of diabetes management in many ways.

It has allowed patients to get real time feedback on how their behavior affects their blood sugar. The use of CGM along with the ensuing behavioral changes actually leads to a decrease in hemoglobin A1c, along with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. CGM has also resulted in patients having a better understanding of several aspects of glucose control, including glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Affordable, readily accessible CGM monitors that allow patients to intermittently use CGM have become available over the last 3 years.

In the United States alone, 34.2 million people have diabetes – nearly 1 in every 10 people. Many do not do self-monitoring of blood glucose and most do not use CGM. The current alternative to CGM – self monitoring of blood glucose – is cumbersome, and, since it requires regular finger sticks, is painful. Also, there is significant cost to each test strip that is used to self-monitor, and most insurance limits the number of times a day a patient can check their blood sugar. CGM used to be reserved only for patients who use multiple doses of insulin daily, and only began being approved for use for patients on basal insulin alone in June 2021.3

Most primary care doctors are just beginning to learn how to interpret CGM data.

Smart watch glucose monitoring predictions

When smart watch glucose monitoring arrives, it will suddenly change the playing field for patients with diabetes and their doctors alike.

We expect it to bring down the price of CGM and make it readily available to any patient who owns a smart watch with that function.

For doctors, the new technology will result in them suddenly being asked to advise their patients on how to use the data generated by watch-based CGM.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. You can contact them at [email protected].

References

1. Hirsh I. Introduction: History of Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association. 2018.

2. Peters A. The Evidence Base for Continuous Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association 2018.

3. “Medicare Loosening Restrictions for Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Coverage,” Healthline. 2021 Jul 13.

Earlier this year, technology news sites reported that the Apple Watch Series 7 and the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 were going to have integrated optical sensors for checking interstitial fluid glucose levels with no blood sampling needed. By the summer, new articles indicated that the glucose sensing watches would not be released this year for either Apple or Samsung.

For now, the newest technology available for monitoring glucose is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which involves a tiny sensor being inserted under the skin. The sensor tests glucose every few minutes, and a transmitter wirelessly sends the information to a monitor, which may be part of an insulin pump or a separate device. Some CGMs send information directly to a smartphone or tablet, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first CGM, which was only approved for downloading 3 days of data at a doctor’s office. Interestingly, the first real-time CGM device for patients to use on their own was a watch, the Glucowatch Biographer. Because of irritation and other issues, that watch never caught on. In 2006 and 2008, Dexcom and then Abbott released the first real-time CGMs that allowed patients to frequently check their own blood sugars.1,2

How CGM has advanced diabetes management

The advent of CGM has advanced the field of diabetes management in many ways.

It has allowed patients to get real time feedback on how their behavior affects their blood sugar. The use of CGM along with the ensuing behavioral changes actually leads to a decrease in hemoglobin A1c, along with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. CGM has also resulted in patients having a better understanding of several aspects of glucose control, including glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Affordable, readily accessible CGM monitors that allow patients to intermittently use CGM have become available over the last 3 years.

In the United States alone, 34.2 million people have diabetes – nearly 1 in every 10 people. Many do not do self-monitoring of blood glucose and most do not use CGM. The current alternative to CGM – self monitoring of blood glucose – is cumbersome, and, since it requires regular finger sticks, is painful. Also, there is significant cost to each test strip that is used to self-monitor, and most insurance limits the number of times a day a patient can check their blood sugar. CGM used to be reserved only for patients who use multiple doses of insulin daily, and only began being approved for use for patients on basal insulin alone in June 2021.3

Most primary care doctors are just beginning to learn how to interpret CGM data.

Smart watch glucose monitoring predictions

When smart watch glucose monitoring arrives, it will suddenly change the playing field for patients with diabetes and their doctors alike.

We expect it to bring down the price of CGM and make it readily available to any patient who owns a smart watch with that function.

For doctors, the new technology will result in them suddenly being asked to advise their patients on how to use the data generated by watch-based CGM.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. You can contact them at [email protected].

References

1. Hirsh I. Introduction: History of Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association. 2018.

2. Peters A. The Evidence Base for Continuous Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association 2018.

3. “Medicare Loosening Restrictions for Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Coverage,” Healthline. 2021 Jul 13.

Earlier this year, technology news sites reported that the Apple Watch Series 7 and the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 were going to have integrated optical sensors for checking interstitial fluid glucose levels with no blood sampling needed. By the summer, new articles indicated that the glucose sensing watches would not be released this year for either Apple or Samsung.

For now, the newest technology available for monitoring glucose is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which involves a tiny sensor being inserted under the skin. The sensor tests glucose every few minutes, and a transmitter wirelessly sends the information to a monitor, which may be part of an insulin pump or a separate device. Some CGMs send information directly to a smartphone or tablet, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first CGM, which was only approved for downloading 3 days of data at a doctor’s office. Interestingly, the first real-time CGM device for patients to use on their own was a watch, the Glucowatch Biographer. Because of irritation and other issues, that watch never caught on. In 2006 and 2008, Dexcom and then Abbott released the first real-time CGMs that allowed patients to frequently check their own blood sugars.1,2

How CGM has advanced diabetes management

The advent of CGM has advanced the field of diabetes management in many ways.

It has allowed patients to get real time feedback on how their behavior affects their blood sugar. The use of CGM along with the ensuing behavioral changes actually leads to a decrease in hemoglobin A1c, along with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. CGM has also resulted in patients having a better understanding of several aspects of glucose control, including glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Affordable, readily accessible CGM monitors that allow patients to intermittently use CGM have become available over the last 3 years.

In the United States alone, 34.2 million people have diabetes – nearly 1 in every 10 people. Many do not do self-monitoring of blood glucose and most do not use CGM. The current alternative to CGM – self monitoring of blood glucose – is cumbersome, and, since it requires regular finger sticks, is painful. Also, there is significant cost to each test strip that is used to self-monitor, and most insurance limits the number of times a day a patient can check their blood sugar. CGM used to be reserved only for patients who use multiple doses of insulin daily, and only began being approved for use for patients on basal insulin alone in June 2021.3

Most primary care doctors are just beginning to learn how to interpret CGM data.

Smart watch glucose monitoring predictions

When smart watch glucose monitoring arrives, it will suddenly change the playing field for patients with diabetes and their doctors alike.

We expect it to bring down the price of CGM and make it readily available to any patient who owns a smart watch with that function.

For doctors, the new technology will result in them suddenly being asked to advise their patients on how to use the data generated by watch-based CGM.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. You can contact them at [email protected].

References

1. Hirsh I. Introduction: History of Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association. 2018.

2. Peters A. The Evidence Base for Continuous Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association 2018.

3. “Medicare Loosening Restrictions for Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Coverage,” Healthline. 2021 Jul 13.

Investigative botulinum toxin formulation shows prolonged effect

, according to results of a phase 3 clinical trial presented at the virtual International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

The ASPEN-1 trial evaluated 301 patients with moderate to severe cervical dystonia for up to 36 weeks and found that those receiving two doses of DaxibotulinumtoxinA, known as DAXI, versus placebo improved their scores on the Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale (TWSTRS), said Joseph Jankovic, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Botulinum neurotoxin is clearly the treatment of choice for cervical dystonia,” Dr. Jankovic said in an interview. “While the majority of patients obtain satisfactory benefit from BoNT injections, some experience adverse effects such as neck weakness and difficulty swallowing.” Another limitation of BoNT is that its effects wear off after about 3 months or less and patients have to be re-injected, he said.

“This is why I am quite encouraged by the results of the DAXI study that suggest that this formulation of BoNT (type A) may have a longer response and relatively few side effects,” he said.

Patients in the study were randomized 1:3:3 to placebo, DAXI 125U or DAXI 250U. The average TWSTRS score upon enrollment was 43.3. The placebo group had a mean ± standard error TWSTRS improvement of 4.3 ± 1.8 at 4 or 6 weeks, while the treatment groups had mean ± SE improvements of 12.7 ± 1.3 for 125U and 10.9 ± 1.2 for 250U (P = .0006 vs. placebo). They translate into improvements of 12%, 31%, and 27% for the placebo and low- and high-dose treatment groups, respectively.

“Even though paradoxically it seems the high-dose group did slightly less well than the low-dose group, there was no difference between the two groups,” Dr. Jankovic said in the presentation.

The median duration of benefit was 24 weeks in the low-dose group and 20.3 weeks in the high-dose group.

The treatment groups demonstrated similar benefit compared with placebo in TWSTRS subscales for disease severity, disability, and pain, Dr. Jankovic said. “The majority of the patients had little better, moderately better, or very much better from the botulinum toxin injection with respect to clinical global impression of change and patient global impression of change,” he said.

Likewise, both the Clinician Global Impression of Change (CGIC) and Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) demonstrated improvement versus placebo: 77.6% and 76.9% in the 125U and 250U doses versus 45.7% for the former; and 71.2% and 73.1% versus 41.3% for the latter.

Side effects “were remarkably minimal,” Dr. Jankovic said, “but I want to call attention to the low frequency of neck weakness or dysphagia in comparison with other studies of botulinum toxin in cervical dystonia.” The rates of dysphagia were 1.6% and 3.9% in the 125U and 250U treatment groups, respectively. Sixteen of the 255 patients in the treatment groups reported muscular weakness or musculoskeletal pain, and seven had dysphagia.