User login

IBD online: What do patients search for?

A new online survey of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients found that individuals seeking information on social media are generally satisfied with the care that they get from their health care providers. However, the online activity suggested a desire for more information, especially with respect to supportive needs like diet and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM).

The study was led by Idan Goren, MD, and Henit Yanai, MD, of Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel.

The researchers suspected that social media users with IBD were looking for information they weren’t getting from their provider, so the researchers set out to identify those specific unmet needs. In a pilot exploratory phase of their investigation, they conducted an initial survey followed by an analysis of social media posts, then they conducted a second phase with a survey based on the findings in the pilot exploration.

The initial survey was conducted within a social media platform in Israel called Camoni, where patients can interact with each other and with health care providers who have experience treating IBD, including gastroenterologists, dietitians, and psychologists. The survey included 10 items about disease characteristics, information needs, information search habits, and other factors. The subsequent analysis step included individual posts on the network between January 2014 and January 2019; the investigators categorized posts by the topics of interest brought up in the initial survey and determined the frequency of posts related to each category.

Out of the 255 respondents to this initial survey, 72% reported satisfaction with the information they received in person. In addition, 67% said that search engines like Google were their most important source of disease-related information, 58% reported relying heavily on websites, and 53% reported relying on health care providers. The most common topics of interest were diet (65%), medications and their potential adverse effects (58%), disease management (48%), and CAM (43%).

After this pilot exploratory phase, the researchers developed a structured survey that they used in IBD-based forums on Facebook and other social networks. Data were collected from this survey during a 4-week period in November 2019.

About half of the 534 respondents to the more widely distributed follow-up survey were in Israel. Overall, 83% reported using IBD-related medications, 45% of which were biologics. Out of the 534 respondents, 70% primarily received treatment from IBD referral centers. Interestingly, 77% said that they would prefer to rely on social media that is guided by health care providers, but only 22% reported that they actually used such a network. Responding along a visual analog scale, they reported general satisfaction with their routine IBD care (mean score, 79 ± 27 out of 100), their providers’ effectiveness of communication (82 ± 24), and the providers’ ability to understand patient concerns (73 ± 28). Those who were active in social media rated accessibility of IBD service as 68 ± 30. Exploration of topical interest found the most common to be diet (46%), lifestyle (45%), CAM (43%), diagnostic test interpretation (34%), and specialist referrals and reviews (31%).

The general satisfaction with information from health care providers contrasted with some previous studies that had shown that patients seeking information online often felt the opposite: For example, a 2019 Canadian survey found that only 10%-36% of IBD patients believed they received adequate information on IBD issues during clinical visits. The authors of the current study speculated that the incongruence might be explained by the fact that the current survey included patients with greater disease burden, who might get more attention during clinic visits than might patients with milder illness.

“In conclusion, our results indicate that patients’ activity on [social media] appears to be independent of their satisfaction with formal IBD care and rather reflects the contemporary need for ongoing information, particularly focused on supportive needs, such as diet and CAM,” the investigators wrote.

“Try not to Google everything”

The findings weren’t surprising, but the researchers found that patients seeking information online often have a high level of disease burden, as evidenced by biologics use and a majority being seen by specialists. That’s worrisome, said Jason Reich, MD, a gastroenterologist in Fall River, Mass., who has also studied social media use among IBD patients but was not involved in this study. “The last person you want getting poor-quality information is someone with pretty active disease,” said Dr. Reich in an interview.

Dr. Reich agreed with the authors that IBD specialists should consider having a dietitian in their clinic, or at least refer patients to dietitians early on. He also advocated for gastroenterologists (and all physicians, really) to have an online presence, if possible. “At least make themselves and their office accessible. I always tell my patients, if you have questions, try not to Google everything online and just shoot me a message through the portal instead,” said Dr. Reich. He added that nurses can handle such duties, especially those trained in IBD. “Personally, I don’t mind sending my short messages back and forth. Especially if it’s just a question. That’s easy enough to do when it takes maybe a minute or 2.”

The authors disclosed no funding sources. Dr. Reich has no relevant financial disclosures.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

A new online survey of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients found that individuals seeking information on social media are generally satisfied with the care that they get from their health care providers. However, the online activity suggested a desire for more information, especially with respect to supportive needs like diet and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM).

The study was led by Idan Goren, MD, and Henit Yanai, MD, of Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel.

The researchers suspected that social media users with IBD were looking for information they weren’t getting from their provider, so the researchers set out to identify those specific unmet needs. In a pilot exploratory phase of their investigation, they conducted an initial survey followed by an analysis of social media posts, then they conducted a second phase with a survey based on the findings in the pilot exploration.

The initial survey was conducted within a social media platform in Israel called Camoni, where patients can interact with each other and with health care providers who have experience treating IBD, including gastroenterologists, dietitians, and psychologists. The survey included 10 items about disease characteristics, information needs, information search habits, and other factors. The subsequent analysis step included individual posts on the network between January 2014 and January 2019; the investigators categorized posts by the topics of interest brought up in the initial survey and determined the frequency of posts related to each category.

Out of the 255 respondents to this initial survey, 72% reported satisfaction with the information they received in person. In addition, 67% said that search engines like Google were their most important source of disease-related information, 58% reported relying heavily on websites, and 53% reported relying on health care providers. The most common topics of interest were diet (65%), medications and their potential adverse effects (58%), disease management (48%), and CAM (43%).

After this pilot exploratory phase, the researchers developed a structured survey that they used in IBD-based forums on Facebook and other social networks. Data were collected from this survey during a 4-week period in November 2019.

About half of the 534 respondents to the more widely distributed follow-up survey were in Israel. Overall, 83% reported using IBD-related medications, 45% of which were biologics. Out of the 534 respondents, 70% primarily received treatment from IBD referral centers. Interestingly, 77% said that they would prefer to rely on social media that is guided by health care providers, but only 22% reported that they actually used such a network. Responding along a visual analog scale, they reported general satisfaction with their routine IBD care (mean score, 79 ± 27 out of 100), their providers’ effectiveness of communication (82 ± 24), and the providers’ ability to understand patient concerns (73 ± 28). Those who were active in social media rated accessibility of IBD service as 68 ± 30. Exploration of topical interest found the most common to be diet (46%), lifestyle (45%), CAM (43%), diagnostic test interpretation (34%), and specialist referrals and reviews (31%).

The general satisfaction with information from health care providers contrasted with some previous studies that had shown that patients seeking information online often felt the opposite: For example, a 2019 Canadian survey found that only 10%-36% of IBD patients believed they received adequate information on IBD issues during clinical visits. The authors of the current study speculated that the incongruence might be explained by the fact that the current survey included patients with greater disease burden, who might get more attention during clinic visits than might patients with milder illness.

“In conclusion, our results indicate that patients’ activity on [social media] appears to be independent of their satisfaction with formal IBD care and rather reflects the contemporary need for ongoing information, particularly focused on supportive needs, such as diet and CAM,” the investigators wrote.

“Try not to Google everything”

The findings weren’t surprising, but the researchers found that patients seeking information online often have a high level of disease burden, as evidenced by biologics use and a majority being seen by specialists. That’s worrisome, said Jason Reich, MD, a gastroenterologist in Fall River, Mass., who has also studied social media use among IBD patients but was not involved in this study. “The last person you want getting poor-quality information is someone with pretty active disease,” said Dr. Reich in an interview.

Dr. Reich agreed with the authors that IBD specialists should consider having a dietitian in their clinic, or at least refer patients to dietitians early on. He also advocated for gastroenterologists (and all physicians, really) to have an online presence, if possible. “At least make themselves and their office accessible. I always tell my patients, if you have questions, try not to Google everything online and just shoot me a message through the portal instead,” said Dr. Reich. He added that nurses can handle such duties, especially those trained in IBD. “Personally, I don’t mind sending my short messages back and forth. Especially if it’s just a question. That’s easy enough to do when it takes maybe a minute or 2.”

The authors disclosed no funding sources. Dr. Reich has no relevant financial disclosures.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

A new online survey of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients found that individuals seeking information on social media are generally satisfied with the care that they get from their health care providers. However, the online activity suggested a desire for more information, especially with respect to supportive needs like diet and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM).

The study was led by Idan Goren, MD, and Henit Yanai, MD, of Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel.

The researchers suspected that social media users with IBD were looking for information they weren’t getting from their provider, so the researchers set out to identify those specific unmet needs. In a pilot exploratory phase of their investigation, they conducted an initial survey followed by an analysis of social media posts, then they conducted a second phase with a survey based on the findings in the pilot exploration.

The initial survey was conducted within a social media platform in Israel called Camoni, where patients can interact with each other and with health care providers who have experience treating IBD, including gastroenterologists, dietitians, and psychologists. The survey included 10 items about disease characteristics, information needs, information search habits, and other factors. The subsequent analysis step included individual posts on the network between January 2014 and January 2019; the investigators categorized posts by the topics of interest brought up in the initial survey and determined the frequency of posts related to each category.

Out of the 255 respondents to this initial survey, 72% reported satisfaction with the information they received in person. In addition, 67% said that search engines like Google were their most important source of disease-related information, 58% reported relying heavily on websites, and 53% reported relying on health care providers. The most common topics of interest were diet (65%), medications and their potential adverse effects (58%), disease management (48%), and CAM (43%).

After this pilot exploratory phase, the researchers developed a structured survey that they used in IBD-based forums on Facebook and other social networks. Data were collected from this survey during a 4-week period in November 2019.

About half of the 534 respondents to the more widely distributed follow-up survey were in Israel. Overall, 83% reported using IBD-related medications, 45% of which were biologics. Out of the 534 respondents, 70% primarily received treatment from IBD referral centers. Interestingly, 77% said that they would prefer to rely on social media that is guided by health care providers, but only 22% reported that they actually used such a network. Responding along a visual analog scale, they reported general satisfaction with their routine IBD care (mean score, 79 ± 27 out of 100), their providers’ effectiveness of communication (82 ± 24), and the providers’ ability to understand patient concerns (73 ± 28). Those who were active in social media rated accessibility of IBD service as 68 ± 30. Exploration of topical interest found the most common to be diet (46%), lifestyle (45%), CAM (43%), diagnostic test interpretation (34%), and specialist referrals and reviews (31%).

The general satisfaction with information from health care providers contrasted with some previous studies that had shown that patients seeking information online often felt the opposite: For example, a 2019 Canadian survey found that only 10%-36% of IBD patients believed they received adequate information on IBD issues during clinical visits. The authors of the current study speculated that the incongruence might be explained by the fact that the current survey included patients with greater disease burden, who might get more attention during clinic visits than might patients with milder illness.

“In conclusion, our results indicate that patients’ activity on [social media] appears to be independent of their satisfaction with formal IBD care and rather reflects the contemporary need for ongoing information, particularly focused on supportive needs, such as diet and CAM,” the investigators wrote.

“Try not to Google everything”

The findings weren’t surprising, but the researchers found that patients seeking information online often have a high level of disease burden, as evidenced by biologics use and a majority being seen by specialists. That’s worrisome, said Jason Reich, MD, a gastroenterologist in Fall River, Mass., who has also studied social media use among IBD patients but was not involved in this study. “The last person you want getting poor-quality information is someone with pretty active disease,” said Dr. Reich in an interview.

Dr. Reich agreed with the authors that IBD specialists should consider having a dietitian in their clinic, or at least refer patients to dietitians early on. He also advocated for gastroenterologists (and all physicians, really) to have an online presence, if possible. “At least make themselves and their office accessible. I always tell my patients, if you have questions, try not to Google everything online and just shoot me a message through the portal instead,” said Dr. Reich. He added that nurses can handle such duties, especially those trained in IBD. “Personally, I don’t mind sending my short messages back and forth. Especially if it’s just a question. That’s easy enough to do when it takes maybe a minute or 2.”

The authors disclosed no funding sources. Dr. Reich has no relevant financial disclosures.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Microaggressions, Accountability, and Our Commitment to Doing Better

We recently published an article in our Leadership & Professional Development series titled “Tribalism: The Good, the Bad, and the Future.” Despite pre- and post-acceptance manuscript review and discussion by a diverse and thoughtful team of editors, we did not appreciate how particular language in this article would be hurtful to some communities. We also promoted the article using the hashtag “tribalism” in a journal tweet. Shortly after we posted the tweet, several readers on social media reached out with constructive feedback on the prejudicial nature of this terminology. Within hours of receiving this feedback, our editorial team met to better understand our error, and we made the decision to immediately retract the manuscript. We also deleted the tweet and issued an apology referencing a screenshot of the original tweet.1,2 We have republished the original article with appropriate language.3 Tweets promoting the new article will incorporate this new language.

From this experience, we learned that the words “tribe” and “tribalism” have no consistent meaning, are associated with negative historical and cultural assumptions, and can promote misleading stereotypes.4 The term “tribe” became popular as a colonial construct to describe forms of social organization considered ”uncivilized” or ”primitive.“5 In using the term “tribe” to describe members of medical communities, we ignored the complex and dynamic identities of Native American, African, and other Indigenous Peoples and the history of their oppression.

The intent of the original article was to highlight how being part of a distinct medical discipline, such as hospital medicine or emergency medicine, conferred benefits, such as shared identity and social support structure, and caution how this group identity could also lead to nonconstructive partisan behaviors that might not best serve our patients. We recognize that other words more accurately convey our intent and do not cause harm. We used “tribe” when we meant “group,” “discipline,” or “specialty.” We used “tribalism” when we meant “siloed” or “factional.”

This misstep underscores how, even with the best intentions and diverse teams, microaggressions can happen. We accept responsibility for this mistake, and we will continue to do the work of respecting and advocating for all members of our community. To minimize the likelihood of future errors, we are developing a systematic process to identify language within manuscripts accepted for publication that may be racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic, or otherwise harmful. As we embrace a growth mindset, we vow to remain transparent, responsive, and welcoming of feedback. We are grateful to our readers for helping us learn.

1. Shah SS [@SamirShahMD]. We are still learning. Despite review by a diverse group of team members, we did not appreciate how language in…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/SamirShahMD/status/1388228974573244431

2. Journal of Hospital Medicine [@JHospMedicine]. We want to apologize. We used insensitive language that may be hurtful to Indigenous Americans & others. We are learning…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/JHospMedicine/status/1388227448962052097

3. Kanjee Z, Bilello L. Specialty silos in medicine: the good, the bad, and the future. J Hosp Med. Published online May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3647

4. Lowe C. The trouble with tribe: How a common word masks complex African realities. Learning for Justice. Spring 2001. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2001/the-trouble-with-tribe

5. Mungai C. Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. January 30, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

We recently published an article in our Leadership & Professional Development series titled “Tribalism: The Good, the Bad, and the Future.” Despite pre- and post-acceptance manuscript review and discussion by a diverse and thoughtful team of editors, we did not appreciate how particular language in this article would be hurtful to some communities. We also promoted the article using the hashtag “tribalism” in a journal tweet. Shortly after we posted the tweet, several readers on social media reached out with constructive feedback on the prejudicial nature of this terminology. Within hours of receiving this feedback, our editorial team met to better understand our error, and we made the decision to immediately retract the manuscript. We also deleted the tweet and issued an apology referencing a screenshot of the original tweet.1,2 We have republished the original article with appropriate language.3 Tweets promoting the new article will incorporate this new language.

From this experience, we learned that the words “tribe” and “tribalism” have no consistent meaning, are associated with negative historical and cultural assumptions, and can promote misleading stereotypes.4 The term “tribe” became popular as a colonial construct to describe forms of social organization considered ”uncivilized” or ”primitive.“5 In using the term “tribe” to describe members of medical communities, we ignored the complex and dynamic identities of Native American, African, and other Indigenous Peoples and the history of their oppression.

The intent of the original article was to highlight how being part of a distinct medical discipline, such as hospital medicine or emergency medicine, conferred benefits, such as shared identity and social support structure, and caution how this group identity could also lead to nonconstructive partisan behaviors that might not best serve our patients. We recognize that other words more accurately convey our intent and do not cause harm. We used “tribe” when we meant “group,” “discipline,” or “specialty.” We used “tribalism” when we meant “siloed” or “factional.”

This misstep underscores how, even with the best intentions and diverse teams, microaggressions can happen. We accept responsibility for this mistake, and we will continue to do the work of respecting and advocating for all members of our community. To minimize the likelihood of future errors, we are developing a systematic process to identify language within manuscripts accepted for publication that may be racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic, or otherwise harmful. As we embrace a growth mindset, we vow to remain transparent, responsive, and welcoming of feedback. We are grateful to our readers for helping us learn.

We recently published an article in our Leadership & Professional Development series titled “Tribalism: The Good, the Bad, and the Future.” Despite pre- and post-acceptance manuscript review and discussion by a diverse and thoughtful team of editors, we did not appreciate how particular language in this article would be hurtful to some communities. We also promoted the article using the hashtag “tribalism” in a journal tweet. Shortly after we posted the tweet, several readers on social media reached out with constructive feedback on the prejudicial nature of this terminology. Within hours of receiving this feedback, our editorial team met to better understand our error, and we made the decision to immediately retract the manuscript. We also deleted the tweet and issued an apology referencing a screenshot of the original tweet.1,2 We have republished the original article with appropriate language.3 Tweets promoting the new article will incorporate this new language.

From this experience, we learned that the words “tribe” and “tribalism” have no consistent meaning, are associated with negative historical and cultural assumptions, and can promote misleading stereotypes.4 The term “tribe” became popular as a colonial construct to describe forms of social organization considered ”uncivilized” or ”primitive.“5 In using the term “tribe” to describe members of medical communities, we ignored the complex and dynamic identities of Native American, African, and other Indigenous Peoples and the history of their oppression.

The intent of the original article was to highlight how being part of a distinct medical discipline, such as hospital medicine or emergency medicine, conferred benefits, such as shared identity and social support structure, and caution how this group identity could also lead to nonconstructive partisan behaviors that might not best serve our patients. We recognize that other words more accurately convey our intent and do not cause harm. We used “tribe” when we meant “group,” “discipline,” or “specialty.” We used “tribalism” when we meant “siloed” or “factional.”

This misstep underscores how, even with the best intentions and diverse teams, microaggressions can happen. We accept responsibility for this mistake, and we will continue to do the work of respecting and advocating for all members of our community. To minimize the likelihood of future errors, we are developing a systematic process to identify language within manuscripts accepted for publication that may be racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic, or otherwise harmful. As we embrace a growth mindset, we vow to remain transparent, responsive, and welcoming of feedback. We are grateful to our readers for helping us learn.

1. Shah SS [@SamirShahMD]. We are still learning. Despite review by a diverse group of team members, we did not appreciate how language in…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/SamirShahMD/status/1388228974573244431

2. Journal of Hospital Medicine [@JHospMedicine]. We want to apologize. We used insensitive language that may be hurtful to Indigenous Americans & others. We are learning…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/JHospMedicine/status/1388227448962052097

3. Kanjee Z, Bilello L. Specialty silos in medicine: the good, the bad, and the future. J Hosp Med. Published online May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3647

4. Lowe C. The trouble with tribe: How a common word masks complex African realities. Learning for Justice. Spring 2001. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2001/the-trouble-with-tribe

5. Mungai C. Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. January 30, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

1. Shah SS [@SamirShahMD]. We are still learning. Despite review by a diverse group of team members, we did not appreciate how language in…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/SamirShahMD/status/1388228974573244431

2. Journal of Hospital Medicine [@JHospMedicine]. We want to apologize. We used insensitive language that may be hurtful to Indigenous Americans & others. We are learning…. April 30, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://twitter.com/JHospMedicine/status/1388227448962052097

3. Kanjee Z, Bilello L. Specialty silos in medicine: the good, the bad, and the future. J Hosp Med. Published online May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3647

4. Lowe C. The trouble with tribe: How a common word masks complex African realities. Learning for Justice. Spring 2001. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2001/the-trouble-with-tribe

5. Mungai C. Pundits who decry ‘tribalism’ know nothing about real tribes. Washington Post. January 30, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/pundits-who-decry-tribalism-know-nothing-about-real-tribes/2019/01/29/8d14eb44-232f-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Leadership & Professional Development: Specialty Silos in Medicine

Siloed, adj.:

Kept in isolation in a way that hinders communication and cooperation . . .

—Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary

Humans naturally separate into groups, and the medical field is no exception. Being a member of a likeminded group, such as one’s specialty, can improve self-esteem and provide social organization: it feels good to identify with people we admire. Through culture, these specialty-based groups implicitly and explicitly guide and encourage positive attributes or behaviors like a hospitalist’s thoroughness or an emergency medicine physician’s steady management of unstable patients. Our specialties also provide support and understanding in challenging times.

Despite these positive aspects, such divisions can negatively affect interprofessional relationships when our specialties become siloed. A potential side-effect of building up ourselves and our own groups is that we can implicitly put others down. For example, a hospitalist who spends extra time on the phone regularly updating each patient’s family will appropriately take pride in their practice, but over time this can also lead to an unreasonable assumption that physicians in other departments with different routines are not as committed to outstanding communication.

These rigid separations facilitate the fundamental attribution error, the tendency to ascribe a problem or disagreement to a colleague’s substandard character or ability. Imagine that the aforementioned hospitalist’s phone call delays a response to an admission page from the emergency room. The emergency medicine physician, who is waiting to sign out the admission while simultaneously managing many sick and complex patients, could assume the hospitalist is being disrespectful, rather than also working hard to provide the best care. Our siloed specialty identities can lead us to imagine the worst in each other and exacerbate intergroup conflict.1

Silos in medicine also adversely affect patients. Poor communication and lack of information-sharing across disciplines can lead to medical error2 and stifle dissemination of safer practices.3 Further, the unintentional disparaging of other medical specialties undermines the confidence our patients have in all of us; a patient within earshot of the hospitalist expressing annoyance at the “impatient” emergency medicine physician who “won’t stop paging,” or the emergency medicine physician complaining about the hospitalist who “refuses to call back,” will lose trust in each of their providers.

We suggest three steps to reduce the negative impact of specialty silos in medicine:

- Get to know each other personally. Friendly conversation during work hours and social interaction outside the hospital can inoculate against interspecialty conflict by putting a human face on our colleagues. The resultant relationships make it easier to work together and see things from another’s perspective.

- Emphasize our shared affiliations.4 The greater the salience of a mutual identity as “healthcare providers,” the more likely we are to recognize each other’s unique contributions and question the stereotypes we imagine about one another.

- Consider projects across specialties. Interdepartmental data-sharing and joint meetings, including educational conferences, can facilitate situational awareness, synergy, and efficient problem-solving.

Our medical specialties will continue to group together. While these groups can be a source of strength and meaning, silos can interfere with professional alliances and effective patient care. Mitigating the harmful effects of silos can benefit all of us and our patients.

Authors’ note: This article was previously published using the term “tribalism,” which we have since learned is derogatory to Indigenous Americans and others. We apologize for any harm. We have retracted and republished the article without this language. We appreciate readers teaching us how to choose better words so all people feel respected and valued.

1. Fiol CM, Pratt MG, O’Connor EJ. Managing intractable identity conflicts. Acad Management Rev. 2009;34(1):32-55. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.35713276

2. Horowitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, et al. Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6): 701-710. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.007

3. Paine, LA, Baker DR, Rosenstein B, Pronovost PJ. The Johns Hopkins Hospital: identifying and addressing risks and safety issues. JT Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30(10):543-550. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30064-x

4. Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04099.x

Siloed, adj.:

Kept in isolation in a way that hinders communication and cooperation . . .

—Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary

Humans naturally separate into groups, and the medical field is no exception. Being a member of a likeminded group, such as one’s specialty, can improve self-esteem and provide social organization: it feels good to identify with people we admire. Through culture, these specialty-based groups implicitly and explicitly guide and encourage positive attributes or behaviors like a hospitalist’s thoroughness or an emergency medicine physician’s steady management of unstable patients. Our specialties also provide support and understanding in challenging times.

Despite these positive aspects, such divisions can negatively affect interprofessional relationships when our specialties become siloed. A potential side-effect of building up ourselves and our own groups is that we can implicitly put others down. For example, a hospitalist who spends extra time on the phone regularly updating each patient’s family will appropriately take pride in their practice, but over time this can also lead to an unreasonable assumption that physicians in other departments with different routines are not as committed to outstanding communication.

These rigid separations facilitate the fundamental attribution error, the tendency to ascribe a problem or disagreement to a colleague’s substandard character or ability. Imagine that the aforementioned hospitalist’s phone call delays a response to an admission page from the emergency room. The emergency medicine physician, who is waiting to sign out the admission while simultaneously managing many sick and complex patients, could assume the hospitalist is being disrespectful, rather than also working hard to provide the best care. Our siloed specialty identities can lead us to imagine the worst in each other and exacerbate intergroup conflict.1

Silos in medicine also adversely affect patients. Poor communication and lack of information-sharing across disciplines can lead to medical error2 and stifle dissemination of safer practices.3 Further, the unintentional disparaging of other medical specialties undermines the confidence our patients have in all of us; a patient within earshot of the hospitalist expressing annoyance at the “impatient” emergency medicine physician who “won’t stop paging,” or the emergency medicine physician complaining about the hospitalist who “refuses to call back,” will lose trust in each of their providers.

We suggest three steps to reduce the negative impact of specialty silos in medicine:

- Get to know each other personally. Friendly conversation during work hours and social interaction outside the hospital can inoculate against interspecialty conflict by putting a human face on our colleagues. The resultant relationships make it easier to work together and see things from another’s perspective.

- Emphasize our shared affiliations.4 The greater the salience of a mutual identity as “healthcare providers,” the more likely we are to recognize each other’s unique contributions and question the stereotypes we imagine about one another.

- Consider projects across specialties. Interdepartmental data-sharing and joint meetings, including educational conferences, can facilitate situational awareness, synergy, and efficient problem-solving.

Our medical specialties will continue to group together. While these groups can be a source of strength and meaning, silos can interfere with professional alliances and effective patient care. Mitigating the harmful effects of silos can benefit all of us and our patients.

Authors’ note: This article was previously published using the term “tribalism,” which we have since learned is derogatory to Indigenous Americans and others. We apologize for any harm. We have retracted and republished the article without this language. We appreciate readers teaching us how to choose better words so all people feel respected and valued.

Siloed, adj.:

Kept in isolation in a way that hinders communication and cooperation . . .

—Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary

Humans naturally separate into groups, and the medical field is no exception. Being a member of a likeminded group, such as one’s specialty, can improve self-esteem and provide social organization: it feels good to identify with people we admire. Through culture, these specialty-based groups implicitly and explicitly guide and encourage positive attributes or behaviors like a hospitalist’s thoroughness or an emergency medicine physician’s steady management of unstable patients. Our specialties also provide support and understanding in challenging times.

Despite these positive aspects, such divisions can negatively affect interprofessional relationships when our specialties become siloed. A potential side-effect of building up ourselves and our own groups is that we can implicitly put others down. For example, a hospitalist who spends extra time on the phone regularly updating each patient’s family will appropriately take pride in their practice, but over time this can also lead to an unreasonable assumption that physicians in other departments with different routines are not as committed to outstanding communication.

These rigid separations facilitate the fundamental attribution error, the tendency to ascribe a problem or disagreement to a colleague’s substandard character or ability. Imagine that the aforementioned hospitalist’s phone call delays a response to an admission page from the emergency room. The emergency medicine physician, who is waiting to sign out the admission while simultaneously managing many sick and complex patients, could assume the hospitalist is being disrespectful, rather than also working hard to provide the best care. Our siloed specialty identities can lead us to imagine the worst in each other and exacerbate intergroup conflict.1

Silos in medicine also adversely affect patients. Poor communication and lack of information-sharing across disciplines can lead to medical error2 and stifle dissemination of safer practices.3 Further, the unintentional disparaging of other medical specialties undermines the confidence our patients have in all of us; a patient within earshot of the hospitalist expressing annoyance at the “impatient” emergency medicine physician who “won’t stop paging,” or the emergency medicine physician complaining about the hospitalist who “refuses to call back,” will lose trust in each of their providers.

We suggest three steps to reduce the negative impact of specialty silos in medicine:

- Get to know each other personally. Friendly conversation during work hours and social interaction outside the hospital can inoculate against interspecialty conflict by putting a human face on our colleagues. The resultant relationships make it easier to work together and see things from another’s perspective.

- Emphasize our shared affiliations.4 The greater the salience of a mutual identity as “healthcare providers,” the more likely we are to recognize each other’s unique contributions and question the stereotypes we imagine about one another.

- Consider projects across specialties. Interdepartmental data-sharing and joint meetings, including educational conferences, can facilitate situational awareness, synergy, and efficient problem-solving.

Our medical specialties will continue to group together. While these groups can be a source of strength and meaning, silos can interfere with professional alliances and effective patient care. Mitigating the harmful effects of silos can benefit all of us and our patients.

Authors’ note: This article was previously published using the term “tribalism,” which we have since learned is derogatory to Indigenous Americans and others. We apologize for any harm. We have retracted and republished the article without this language. We appreciate readers teaching us how to choose better words so all people feel respected and valued.

1. Fiol CM, Pratt MG, O’Connor EJ. Managing intractable identity conflicts. Acad Management Rev. 2009;34(1):32-55. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.35713276

2. Horowitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, et al. Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6): 701-710. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.007

3. Paine, LA, Baker DR, Rosenstein B, Pronovost PJ. The Johns Hopkins Hospital: identifying and addressing risks and safety issues. JT Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30(10):543-550. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30064-x

4. Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04099.x

1. Fiol CM, Pratt MG, O’Connor EJ. Managing intractable identity conflicts. Acad Management Rev. 2009;34(1):32-55. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.35713276

2. Horowitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, et al. Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6): 701-710. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.007

3. Paine, LA, Baker DR, Rosenstein B, Pronovost PJ. The Johns Hopkins Hospital: identifying and addressing risks and safety issues. JT Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30(10):543-550. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30064-x

4. Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04099.x

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Some things pediatric hospitalists do for no reason

Converge 2021 session

High Value Care in Pediatrics – Things We Do for No Reason

Presenter

Ricardo Quinonez, MD, FAAP, FHM

Session summary

Dr. Ricardo Quinonez, associate professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, presented key topics in pediatric hospital medicine with low-value care management practices which are not supported by recent literature. This session was a continuation of the popular lecture series first presented at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference and the “Choosing Wisely: Things We Do for No Reason” article series in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Quinonez began by discussing high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) in bronchiolitis. At first, early observational studies showed a decrease in intubation rate for children placed on HFNC, which resulted in its high utilization. Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) later showed that early initiation of HFNC did not affect rates of transfer to the ICU, duration of oxygen need, or length of stay.

He then discussed the treatment of symptomatic spontaneous pneumothorax in children, which is often managed by hospital admission, needle aspiration and chest tube placement, and serial chest x-rays. Instead, recent literature supports an ambulatory approach by placing a device with an 8 French catheter with one way Heimlich valve. After placement, a chest x-ray is performed and if the pneumothorax is stable, the patient is discharged with plans for serial chest x-rays as an outpatient. The device is removed after re-expansion of the lung.

Dr. Quinonez then discussed the frequent pediatric complaint of constipation. He stated that abdominal x-rays for evaluation of “stool burden” are not reliable, and x-rays are recommended against in both U.S. and British guidelines. Furthermore, a high-fiber diet is often recommended as a treatment for constipation. However, after review of recent RCTs and cohort studies, no relationship between a low-fiber diet and constipation was seen. Instead, genetics likely plays a large part in causing constipation.

Lastly, Dr. Quinonez discussed electrolyte testing in children with acute gastroenteritis. Electrolyte testing is commonly performed, yet testing patterns vary greatly across children’s hospitals. One quality improvement project found that after decreasing electrolyte testing by more than a third during hospitalizations, no change in readmission rate or renal replacement therapy was reported.

Key takeaways

- Early use of high flow nasal cannula in bronchiolitis does not affect rates of transfer to the ICU or length of stay.

- Abdominal x-rays to assess for constipation are not recommended and are not reliable in measuring stool burden.

- A low-fiber diet does not cause constipation.

- Quality improvement projects can help physicians “choose wisely” and decrease things we do for no reason.

Dr. Tantoco is an academic med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is an instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Converge 2021 session

High Value Care in Pediatrics – Things We Do for No Reason

Presenter

Ricardo Quinonez, MD, FAAP, FHM

Session summary

Dr. Ricardo Quinonez, associate professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, presented key topics in pediatric hospital medicine with low-value care management practices which are not supported by recent literature. This session was a continuation of the popular lecture series first presented at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference and the “Choosing Wisely: Things We Do for No Reason” article series in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Quinonez began by discussing high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) in bronchiolitis. At first, early observational studies showed a decrease in intubation rate for children placed on HFNC, which resulted in its high utilization. Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) later showed that early initiation of HFNC did not affect rates of transfer to the ICU, duration of oxygen need, or length of stay.

He then discussed the treatment of symptomatic spontaneous pneumothorax in children, which is often managed by hospital admission, needle aspiration and chest tube placement, and serial chest x-rays. Instead, recent literature supports an ambulatory approach by placing a device with an 8 French catheter with one way Heimlich valve. After placement, a chest x-ray is performed and if the pneumothorax is stable, the patient is discharged with plans for serial chest x-rays as an outpatient. The device is removed after re-expansion of the lung.

Dr. Quinonez then discussed the frequent pediatric complaint of constipation. He stated that abdominal x-rays for evaluation of “stool burden” are not reliable, and x-rays are recommended against in both U.S. and British guidelines. Furthermore, a high-fiber diet is often recommended as a treatment for constipation. However, after review of recent RCTs and cohort studies, no relationship between a low-fiber diet and constipation was seen. Instead, genetics likely plays a large part in causing constipation.

Lastly, Dr. Quinonez discussed electrolyte testing in children with acute gastroenteritis. Electrolyte testing is commonly performed, yet testing patterns vary greatly across children’s hospitals. One quality improvement project found that after decreasing electrolyte testing by more than a third during hospitalizations, no change in readmission rate or renal replacement therapy was reported.

Key takeaways

- Early use of high flow nasal cannula in bronchiolitis does not affect rates of transfer to the ICU or length of stay.

- Abdominal x-rays to assess for constipation are not recommended and are not reliable in measuring stool burden.

- A low-fiber diet does not cause constipation.

- Quality improvement projects can help physicians “choose wisely” and decrease things we do for no reason.

Dr. Tantoco is an academic med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is an instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Converge 2021 session

High Value Care in Pediatrics – Things We Do for No Reason

Presenter

Ricardo Quinonez, MD, FAAP, FHM

Session summary

Dr. Ricardo Quinonez, associate professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, presented key topics in pediatric hospital medicine with low-value care management practices which are not supported by recent literature. This session was a continuation of the popular lecture series first presented at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference and the “Choosing Wisely: Things We Do for No Reason” article series in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Quinonez began by discussing high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) in bronchiolitis. At first, early observational studies showed a decrease in intubation rate for children placed on HFNC, which resulted in its high utilization. Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) later showed that early initiation of HFNC did not affect rates of transfer to the ICU, duration of oxygen need, or length of stay.

He then discussed the treatment of symptomatic spontaneous pneumothorax in children, which is often managed by hospital admission, needle aspiration and chest tube placement, and serial chest x-rays. Instead, recent literature supports an ambulatory approach by placing a device with an 8 French catheter with one way Heimlich valve. After placement, a chest x-ray is performed and if the pneumothorax is stable, the patient is discharged with plans for serial chest x-rays as an outpatient. The device is removed after re-expansion of the lung.

Dr. Quinonez then discussed the frequent pediatric complaint of constipation. He stated that abdominal x-rays for evaluation of “stool burden” are not reliable, and x-rays are recommended against in both U.S. and British guidelines. Furthermore, a high-fiber diet is often recommended as a treatment for constipation. However, after review of recent RCTs and cohort studies, no relationship between a low-fiber diet and constipation was seen. Instead, genetics likely plays a large part in causing constipation.

Lastly, Dr. Quinonez discussed electrolyte testing in children with acute gastroenteritis. Electrolyte testing is commonly performed, yet testing patterns vary greatly across children’s hospitals. One quality improvement project found that after decreasing electrolyte testing by more than a third during hospitalizations, no change in readmission rate or renal replacement therapy was reported.

Key takeaways

- Early use of high flow nasal cannula in bronchiolitis does not affect rates of transfer to the ICU or length of stay.

- Abdominal x-rays to assess for constipation are not recommended and are not reliable in measuring stool burden.

- A low-fiber diet does not cause constipation.

- Quality improvement projects can help physicians “choose wisely” and decrease things we do for no reason.

Dr. Tantoco is an academic med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is an instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

SAFE-PAD: Endovascular paclitaxel-coated devices exonerated in real-world analysis

A cohort analysis using advanced strategies to minimize the impact of confounders has concluded that the current Food and Drug Administration warning about paclitaxel-coated devices used for femoropopliteal endovascular treatment should be lifted, according to investigators of a study called SAFE-PAD.

In early 2019, an FDA letter to clinicians warned that endovascular stents and balloons coated with paclitaxel might increase mortality, recounted the principal investigator of SAFE-PAD, Eric A. Secemsky, MD, director of vascular intervention, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston.

An FDA advisory committee that was subsequently convened in 2019 did not elect to remove these devices from the market, but it did call for restrictions and for the collection of more safety data. In the absence of a clear mechanism of risk, and in the context of perceived problems with data suggesting harm, Dr. Secemsky said that there was interest in a conclusive answer.

The problem was that a randomized controlled trial, even if funding were available, was considered impractical, he noted in presenting SAFE-PAD at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

In the initial meta-analysis that suggested an increased mortality risk, no risk was seen in the first year after exposure, and it climbed to only 3.5% after 2 years. As a result, the definitive 2-year study with sufficient power to produce conclusive results was an estimated 40,000 patients. Even if extended to 5 years, 20,000 patients would be needed, according to Dr. Secemsky.

SAFE-PAD born of collaboration

An alternative solution was required, which is why “we became engaged with the FDA to design a real-world study for use in making a regulatory decision,” Dr. Secemsky said.

SAFE-PAD, designed with feedback from the FDA, employed sophisticated methodologies to account for known and unknown confounding in the Medicare cohort data used for this study.

Of 168,553 Medicare fee-for-service patients undergoing femoropopliteal artery revascularization with a stent, a balloon, or both at 2,978 institutions, 70,584 (42%) were treated with a paclitaxel drug-coated device (DCD) and the remainder were managed with a non–drug-coated device (NDCD).

The groups were compared with a primary outcome of all-cause mortality in a design to evaluate DCD for noninferiority. Several secondary outcomes, such as repeated lower extremity revascularization, were also evaluated.

To create balanced groups, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) blinded to outcome was the primary analytic strategy. In addition, several sensitivity analyses were applied, including a technique that tests for the impact of a hypothetical variable that allows adjustment for an unknown confounder.

After a median follow-up of 2.7 years (longest more than 5 years), the cumulative mortality after weighting was 53.8% in the DCD group and 55.1% in the NDCD group. The 5% advantage for the DCD group (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-0.97) ensured noninferiority (P < .001).

On unweighted analysis, the mortality difference favoring DCD was even greater (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82–0.85).

None of the sensitivity analyses – including a multivariable Cox regression analysis, an instrumental variable analysis, and a falsification endpoints analysis that employed myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and heart failure – altered the conclusion. The hypothetical variable analysis produced the same result.

“A missing confounder would need to be more prevalent and more strongly associated to outcome than any measured variable in this analysis,” reported Dr. Secemsky, indicating that this ruled out essentially any probability of this occurring.

A subgroup analysis told the same story. By hazard ratio for the outcome of mortality, DCD was consistently favored over NDCD for groups characterized by low risk (HR, 0.98), stent implantation (HR, 0.97), receipt of balloon angioplasty alone (HR, 0.94), having critical limb ischemia (HR, 0.95) or no critical limb ischemia (HR, 0.97), and being managed inpatient (HR, 0.97) or outpatient (HR, 0.95).

The results of SAFE-PAD were simultaneously published with Dr. Secemsky’s ACC presentation.

Value of revascularization questioned

In an accompanying editorial, the coauthors Rita F. Redberg, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and Mary M. McDermott, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, reiterated the findings and the conclusions, but used the forum to draw attention to the low survival rates.

“Thus, while this well-done observational study provides new information,” they wrote, “a major conclusion should be that mortality is high among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing revascularization [for peripheral artery disease] with any devices.”

‘Very impressive’ methods

Marc P. Bonaca, MD, director of vascular research, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, called the methods to ensure the validity of the conclusions of this study “very impressive.” In situations where prospective randomized trials are impractical, he suggested that this type of approach might answer an unmet need.

“We have always desired the ability to look at these large datasets with a lot of power to answer important questions,” he said. While “the issue has always been residual confounding,” he expressed interest in further verifications that this type of methodology can serve as a template for data analysis to guide other regulatory decisions.

Dr. Secemsky reports financial relationships with Abbott, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Cook, CSI, Inari, Janssen, Medtronic, and Phillips. Dr. Redford reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. McDermott reports a financial relationship with Regeneron. Dr. Bonaca reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A cohort analysis using advanced strategies to minimize the impact of confounders has concluded that the current Food and Drug Administration warning about paclitaxel-coated devices used for femoropopliteal endovascular treatment should be lifted, according to investigators of a study called SAFE-PAD.

In early 2019, an FDA letter to clinicians warned that endovascular stents and balloons coated with paclitaxel might increase mortality, recounted the principal investigator of SAFE-PAD, Eric A. Secemsky, MD, director of vascular intervention, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston.

An FDA advisory committee that was subsequently convened in 2019 did not elect to remove these devices from the market, but it did call for restrictions and for the collection of more safety data. In the absence of a clear mechanism of risk, and in the context of perceived problems with data suggesting harm, Dr. Secemsky said that there was interest in a conclusive answer.

The problem was that a randomized controlled trial, even if funding were available, was considered impractical, he noted in presenting SAFE-PAD at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

In the initial meta-analysis that suggested an increased mortality risk, no risk was seen in the first year after exposure, and it climbed to only 3.5% after 2 years. As a result, the definitive 2-year study with sufficient power to produce conclusive results was an estimated 40,000 patients. Even if extended to 5 years, 20,000 patients would be needed, according to Dr. Secemsky.

SAFE-PAD born of collaboration

An alternative solution was required, which is why “we became engaged with the FDA to design a real-world study for use in making a regulatory decision,” Dr. Secemsky said.

SAFE-PAD, designed with feedback from the FDA, employed sophisticated methodologies to account for known and unknown confounding in the Medicare cohort data used for this study.

Of 168,553 Medicare fee-for-service patients undergoing femoropopliteal artery revascularization with a stent, a balloon, or both at 2,978 institutions, 70,584 (42%) were treated with a paclitaxel drug-coated device (DCD) and the remainder were managed with a non–drug-coated device (NDCD).

The groups were compared with a primary outcome of all-cause mortality in a design to evaluate DCD for noninferiority. Several secondary outcomes, such as repeated lower extremity revascularization, were also evaluated.

To create balanced groups, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) blinded to outcome was the primary analytic strategy. In addition, several sensitivity analyses were applied, including a technique that tests for the impact of a hypothetical variable that allows adjustment for an unknown confounder.

After a median follow-up of 2.7 years (longest more than 5 years), the cumulative mortality after weighting was 53.8% in the DCD group and 55.1% in the NDCD group. The 5% advantage for the DCD group (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-0.97) ensured noninferiority (P < .001).

On unweighted analysis, the mortality difference favoring DCD was even greater (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82–0.85).

None of the sensitivity analyses – including a multivariable Cox regression analysis, an instrumental variable analysis, and a falsification endpoints analysis that employed myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and heart failure – altered the conclusion. The hypothetical variable analysis produced the same result.

“A missing confounder would need to be more prevalent and more strongly associated to outcome than any measured variable in this analysis,” reported Dr. Secemsky, indicating that this ruled out essentially any probability of this occurring.

A subgroup analysis told the same story. By hazard ratio for the outcome of mortality, DCD was consistently favored over NDCD for groups characterized by low risk (HR, 0.98), stent implantation (HR, 0.97), receipt of balloon angioplasty alone (HR, 0.94), having critical limb ischemia (HR, 0.95) or no critical limb ischemia (HR, 0.97), and being managed inpatient (HR, 0.97) or outpatient (HR, 0.95).

The results of SAFE-PAD were simultaneously published with Dr. Secemsky’s ACC presentation.

Value of revascularization questioned

In an accompanying editorial, the coauthors Rita F. Redberg, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and Mary M. McDermott, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, reiterated the findings and the conclusions, but used the forum to draw attention to the low survival rates.

“Thus, while this well-done observational study provides new information,” they wrote, “a major conclusion should be that mortality is high among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing revascularization [for peripheral artery disease] with any devices.”

‘Very impressive’ methods

Marc P. Bonaca, MD, director of vascular research, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, called the methods to ensure the validity of the conclusions of this study “very impressive.” In situations where prospective randomized trials are impractical, he suggested that this type of approach might answer an unmet need.

“We have always desired the ability to look at these large datasets with a lot of power to answer important questions,” he said. While “the issue has always been residual confounding,” he expressed interest in further verifications that this type of methodology can serve as a template for data analysis to guide other regulatory decisions.

Dr. Secemsky reports financial relationships with Abbott, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Cook, CSI, Inari, Janssen, Medtronic, and Phillips. Dr. Redford reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. McDermott reports a financial relationship with Regeneron. Dr. Bonaca reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A cohort analysis using advanced strategies to minimize the impact of confounders has concluded that the current Food and Drug Administration warning about paclitaxel-coated devices used for femoropopliteal endovascular treatment should be lifted, according to investigators of a study called SAFE-PAD.

In early 2019, an FDA letter to clinicians warned that endovascular stents and balloons coated with paclitaxel might increase mortality, recounted the principal investigator of SAFE-PAD, Eric A. Secemsky, MD, director of vascular intervention, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston.

An FDA advisory committee that was subsequently convened in 2019 did not elect to remove these devices from the market, but it did call for restrictions and for the collection of more safety data. In the absence of a clear mechanism of risk, and in the context of perceived problems with data suggesting harm, Dr. Secemsky said that there was interest in a conclusive answer.

The problem was that a randomized controlled trial, even if funding were available, was considered impractical, he noted in presenting SAFE-PAD at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

In the initial meta-analysis that suggested an increased mortality risk, no risk was seen in the first year after exposure, and it climbed to only 3.5% after 2 years. As a result, the definitive 2-year study with sufficient power to produce conclusive results was an estimated 40,000 patients. Even if extended to 5 years, 20,000 patients would be needed, according to Dr. Secemsky.

SAFE-PAD born of collaboration

An alternative solution was required, which is why “we became engaged with the FDA to design a real-world study for use in making a regulatory decision,” Dr. Secemsky said.

SAFE-PAD, designed with feedback from the FDA, employed sophisticated methodologies to account for known and unknown confounding in the Medicare cohort data used for this study.

Of 168,553 Medicare fee-for-service patients undergoing femoropopliteal artery revascularization with a stent, a balloon, or both at 2,978 institutions, 70,584 (42%) were treated with a paclitaxel drug-coated device (DCD) and the remainder were managed with a non–drug-coated device (NDCD).

The groups were compared with a primary outcome of all-cause mortality in a design to evaluate DCD for noninferiority. Several secondary outcomes, such as repeated lower extremity revascularization, were also evaluated.

To create balanced groups, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) blinded to outcome was the primary analytic strategy. In addition, several sensitivity analyses were applied, including a technique that tests for the impact of a hypothetical variable that allows adjustment for an unknown confounder.

After a median follow-up of 2.7 years (longest more than 5 years), the cumulative mortality after weighting was 53.8% in the DCD group and 55.1% in the NDCD group. The 5% advantage for the DCD group (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-0.97) ensured noninferiority (P < .001).

On unweighted analysis, the mortality difference favoring DCD was even greater (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82–0.85).

None of the sensitivity analyses – including a multivariable Cox regression analysis, an instrumental variable analysis, and a falsification endpoints analysis that employed myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and heart failure – altered the conclusion. The hypothetical variable analysis produced the same result.

“A missing confounder would need to be more prevalent and more strongly associated to outcome than any measured variable in this analysis,” reported Dr. Secemsky, indicating that this ruled out essentially any probability of this occurring.

A subgroup analysis told the same story. By hazard ratio for the outcome of mortality, DCD was consistently favored over NDCD for groups characterized by low risk (HR, 0.98), stent implantation (HR, 0.97), receipt of balloon angioplasty alone (HR, 0.94), having critical limb ischemia (HR, 0.95) or no critical limb ischemia (HR, 0.97), and being managed inpatient (HR, 0.97) or outpatient (HR, 0.95).

The results of SAFE-PAD were simultaneously published with Dr. Secemsky’s ACC presentation.

Value of revascularization questioned

In an accompanying editorial, the coauthors Rita F. Redberg, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and Mary M. McDermott, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, reiterated the findings and the conclusions, but used the forum to draw attention to the low survival rates.

“Thus, while this well-done observational study provides new information,” they wrote, “a major conclusion should be that mortality is high among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing revascularization [for peripheral artery disease] with any devices.”

‘Very impressive’ methods

Marc P. Bonaca, MD, director of vascular research, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, called the methods to ensure the validity of the conclusions of this study “very impressive.” In situations where prospective randomized trials are impractical, he suggested that this type of approach might answer an unmet need.

“We have always desired the ability to look at these large datasets with a lot of power to answer important questions,” he said. While “the issue has always been residual confounding,” he expressed interest in further verifications that this type of methodology can serve as a template for data analysis to guide other regulatory decisions.

Dr. Secemsky reports financial relationships with Abbott, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Cook, CSI, Inari, Janssen, Medtronic, and Phillips. Dr. Redford reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. McDermott reports a financial relationship with Regeneron. Dr. Bonaca reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

FROM ACC 2021

Family physicians’ compensation levels stable in pandemic

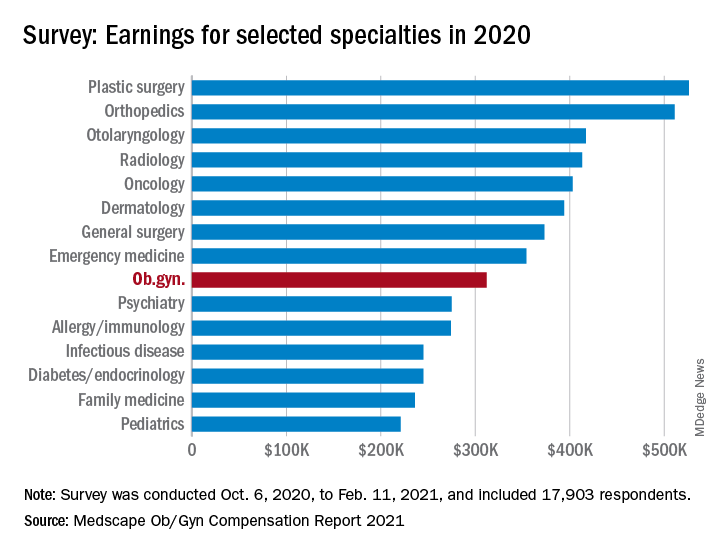

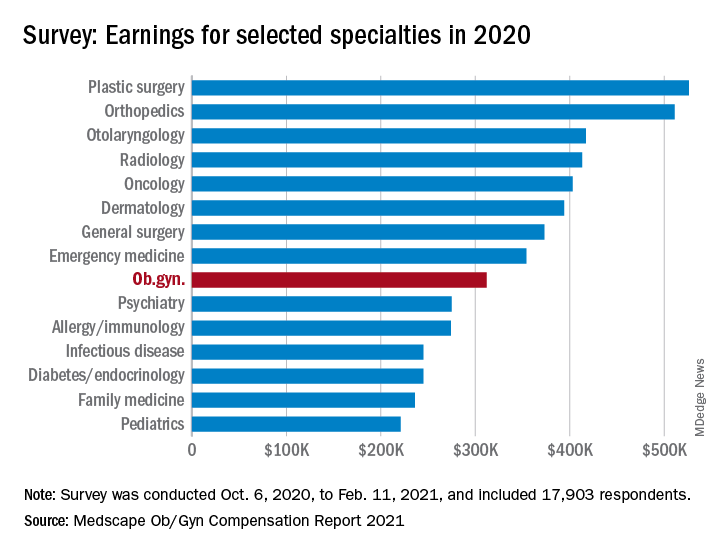

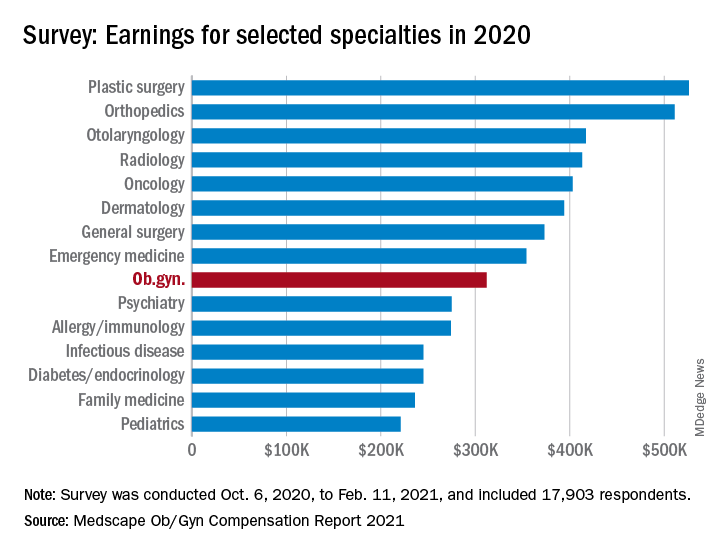

to $236,000, up from $234,000 last year, even as many practices saw a decrease in hours and patient visits during the pandemic.

Only pediatricians earned less ($221,000) according to the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2021. Plastic surgeons topped this year’s list, at $526,000, followed by orthopedists, at $511,000, and cardiologists, at $459,000.

Family physicians ranked in the middle of specialties in terms of the percentages of physicians who thought they were fairly compensated: 57% of family physicians said they were fairly paid, and 79% of oncologists said they were. Only 44% of infectious disease physicians said they were fairly compensated.

Survey answers indicate, though, that pay isn’t driving family physicians’ satisfaction.

Only 10% of family physicians in the survey said that “making good money at a job I like” was the most rewarding aspect of the job. The top two answers by far were “gratitude/relationships with patients” (chosen by 34%) and “knowing I’m making the world a better place” (27%). Respondents could choose more than one answer.

Despite the small uptick in earnings overall in the specialty, more than one-third of family physicians (36%) reported a decline in compensation in this year’s survey, which included 18,000 responses from physicians in 29 specialties.

Male family physicians continue to be paid much more than their female colleagues, this year 29% more, widening the gap from 26% last year. Overall, men in primary care earned 27% more than their female colleagues, and male specialists earned 33% more.

As for decline in patients seen in some specialties, family physicians are holding their own.

Whereas pediatricians have seen a drop of 18% in patient visits, family physicians saw a decline of just 5%, from an average of 81 to 77 patients per week.

Most expect return to normal pay within 3 years

Most family physicians (83%) who incurred financial losses this year said they expect that income will return to normal within 3 years. More than one-third of that group (38%) said they expect compensation to get back to normal in the next year.

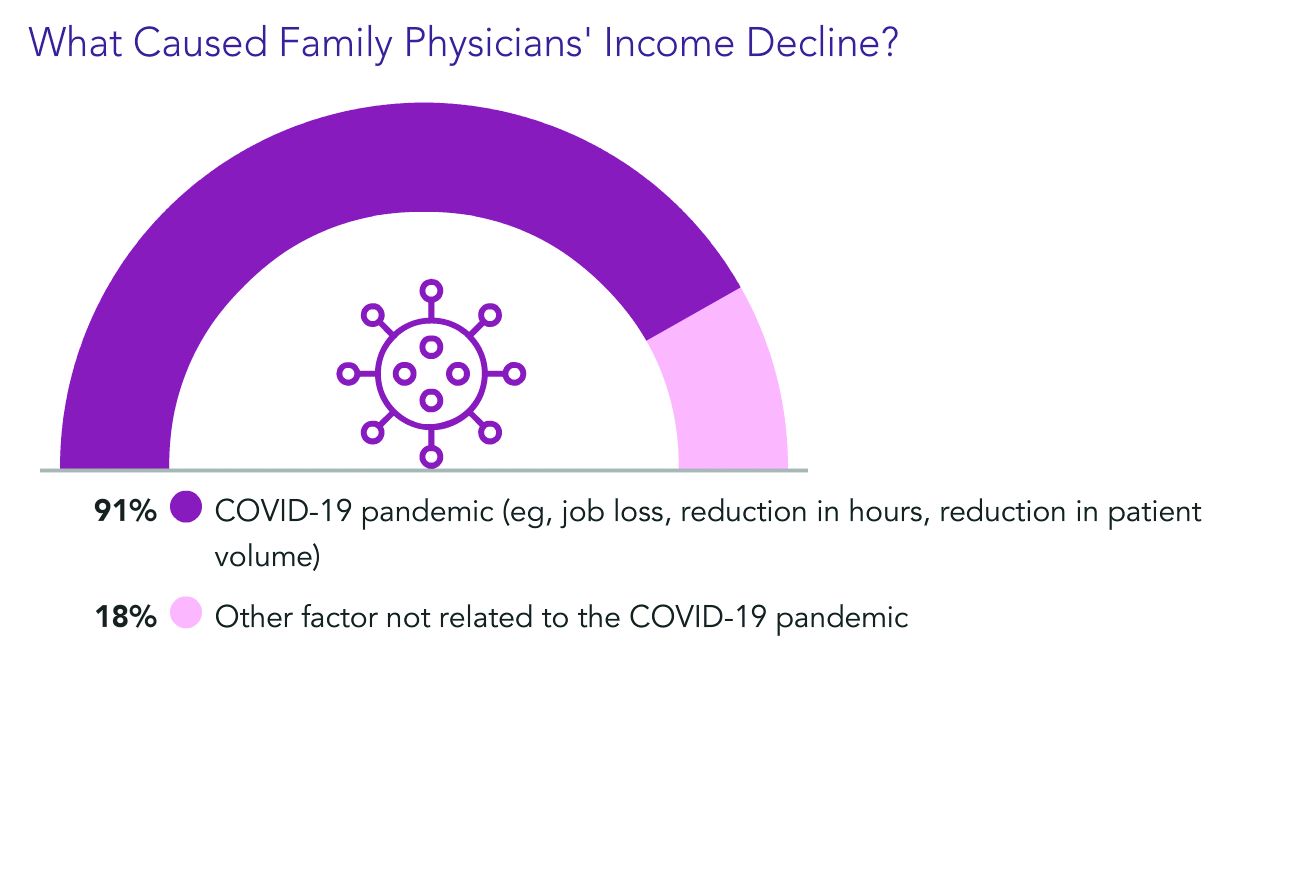

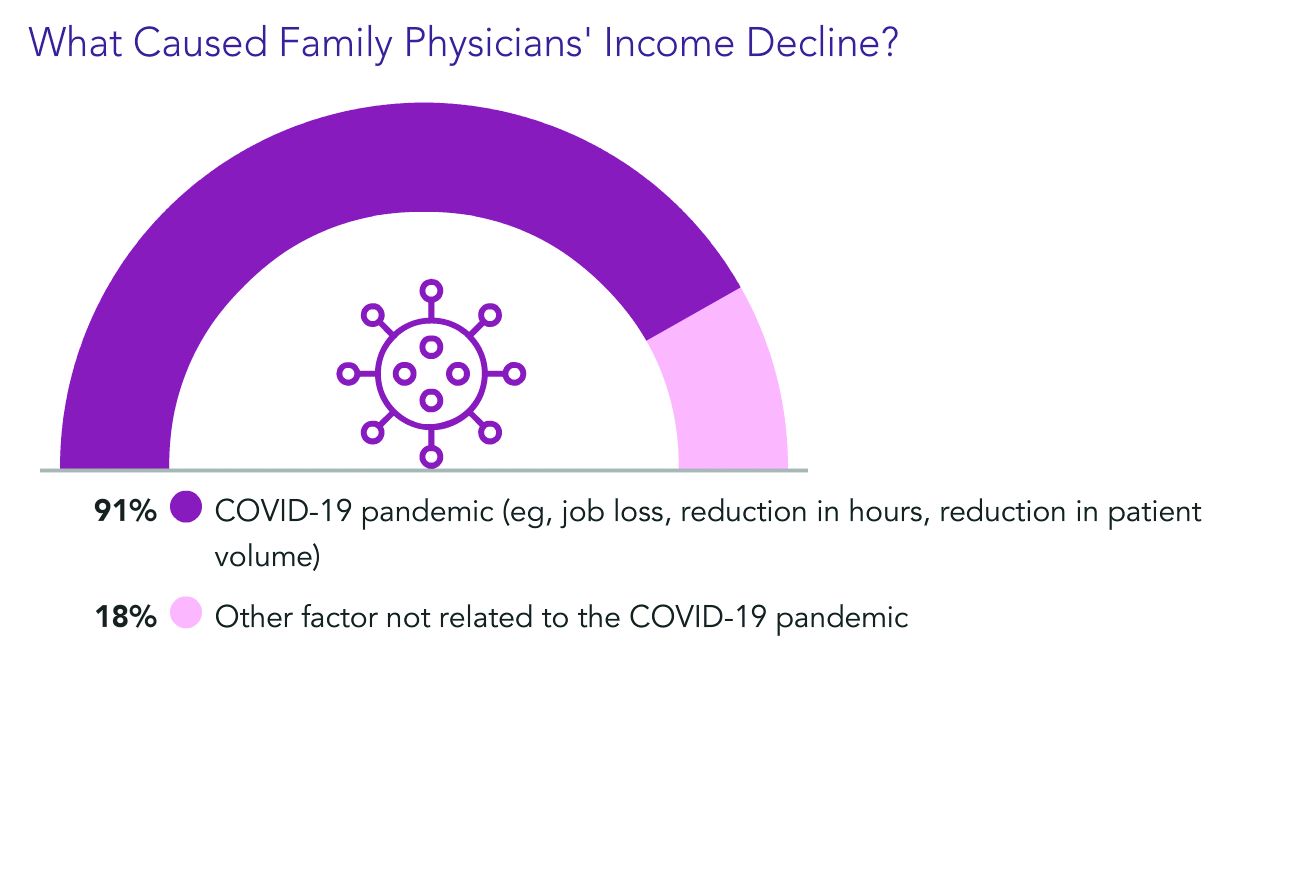

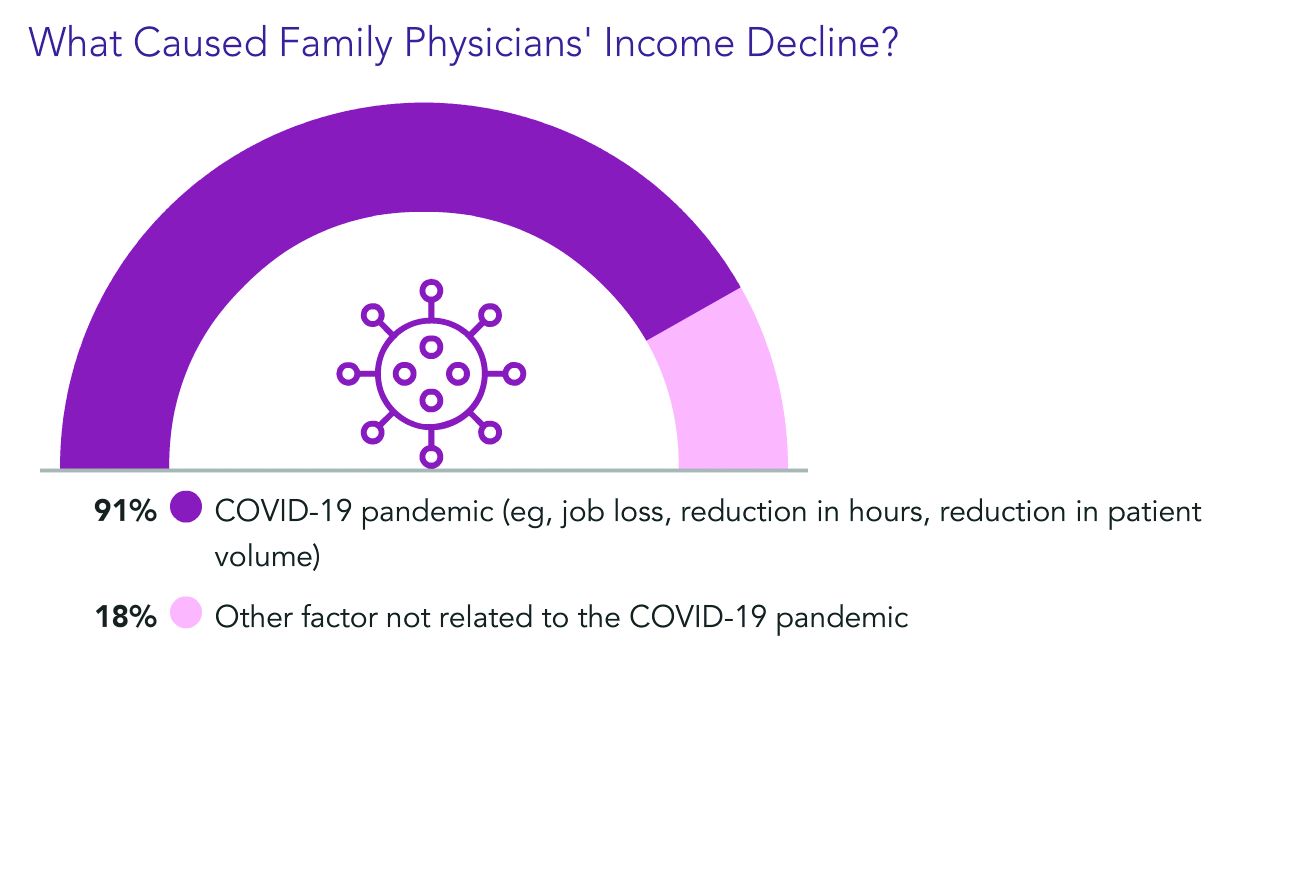

Almost all of the family physicians who lost income (91%) pointed the finger at COVID-19. Respondents could choose more than one answer, and 18% said other factors were also to blame.

Family physicians averaged $27,000 in incentive bonuses, higher than those in internal medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry. Orthopedists had by far the highest bonuses, at $116,000.

For family physicians who received a bonus this year, the amount equaled about 12% of their salary, up from 10% last year. Bonuses are usually based on productivity but can also be tied to patient satisfaction, clinical processes, and other factors.

The number of family physicians who achieved more than three-quarters of their potential annual bonus rose to 61% this year, up from 55%.

17 hours a week on administrative tasks

The survey also ranked specialties by the amount of time physicians spent on paperwork and administrative tasks, including participation in professional organizations and clinical reading.

Family physicians fell squarely in the middle, with 17 hours per week spent on such tasks. Infectious disease physicians spent the most time, at 24.2 hours a week, and anesthesiologists spent the least, at 10.1.

Work hours declined for many physicians during the pandemic, and some were furloughed.

But, like most physicians, family physicians are once more working normal hours. They average 49 hours per week, which is slightly more than before the pandemic.

Specialists whose weekly hours are above normal are infectious disease physicians, intensivists, and public health and preventive medicine physicians; all are working 6 to 7 hours a week more than usual, according to the survey responses.

Responses also turned up some uncertainty on the future makeup of patient panels.

Most family physicians (69%) said they would continue to take new and current Medicare/Medicaid patients.

However, close to one-third of family physicians said they would stop treating at least some patients they already have and will not take new ones or haven’t decided yet.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

to $236,000, up from $234,000 last year, even as many practices saw a decrease in hours and patient visits during the pandemic.

Only pediatricians earned less ($221,000) according to the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2021. Plastic surgeons topped this year’s list, at $526,000, followed by orthopedists, at $511,000, and cardiologists, at $459,000.

Family physicians ranked in the middle of specialties in terms of the percentages of physicians who thought they were fairly compensated: 57% of family physicians said they were fairly paid, and 79% of oncologists said they were. Only 44% of infectious disease physicians said they were fairly compensated.

Survey answers indicate, though, that pay isn’t driving family physicians’ satisfaction.

Only 10% of family physicians in the survey said that “making good money at a job I like” was the most rewarding aspect of the job. The top two answers by far were “gratitude/relationships with patients” (chosen by 34%) and “knowing I’m making the world a better place” (27%). Respondents could choose more than one answer.

Despite the small uptick in earnings overall in the specialty, more than one-third of family physicians (36%) reported a decline in compensation in this year’s survey, which included 18,000 responses from physicians in 29 specialties.

Male family physicians continue to be paid much more than their female colleagues, this year 29% more, widening the gap from 26% last year. Overall, men in primary care earned 27% more than their female colleagues, and male specialists earned 33% more.

As for decline in patients seen in some specialties, family physicians are holding their own.

Whereas pediatricians have seen a drop of 18% in patient visits, family physicians saw a decline of just 5%, from an average of 81 to 77 patients per week.

Most expect return to normal pay within 3 years

Most family physicians (83%) who incurred financial losses this year said they expect that income will return to normal within 3 years. More than one-third of that group (38%) said they expect compensation to get back to normal in the next year.

Almost all of the family physicians who lost income (91%) pointed the finger at COVID-19. Respondents could choose more than one answer, and 18% said other factors were also to blame.

Family physicians averaged $27,000 in incentive bonuses, higher than those in internal medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry. Orthopedists had by far the highest bonuses, at $116,000.

For family physicians who received a bonus this year, the amount equaled about 12% of their salary, up from 10% last year. Bonuses are usually based on productivity but can also be tied to patient satisfaction, clinical processes, and other factors.

The number of family physicians who achieved more than three-quarters of their potential annual bonus rose to 61% this year, up from 55%.

17 hours a week on administrative tasks

The survey also ranked specialties by the amount of time physicians spent on paperwork and administrative tasks, including participation in professional organizations and clinical reading.