User login

New data on worldwide mental health impact of COVID-19

A new survey that assessed the mental health impact of COVID-19 across the globe shows high rates of trauma and clinical mood disorders related to the pandemic.

The survey, carried out by Sapien Labs, was conducted in eight English-speaking countries and included 49,000 adults. It showed that 57% of respondents experienced some COVID-19–related adversity or trauma.

Roughly one-quarter showed clinical signs of or were at risk for a mood disorder, and 40% described themselves as “succeeding or thriving.”

Those who reported the poorest mental health were young adults and individuals who experienced financial adversity or were unable to receive care for other medical conditions. Nonbinary gender and not getting enough sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialization also increased the risk for poorer mental well-being.

“The data suggest that there will be long-term fallout from the pandemic on the mental health front,” Tara Thiagarajan, PhD, Sapien Labs founder and chief scientist, said in a press release.

Novel initiative

Dr. Thiagarajan said in an interview that she was running a company that provided microloans to 30,000 villages in India. The company included a research group the goal of which was to understand what predicts success in an individual and in a particular ecosystem, she said – “Why did some villages succeed and others didn’t?”

Dr. Thiagarajan and associates thought that “something big is happening in our life circumstances that causes changes in our brain and felt that we need to understand what they are and how they affect humanity. This was the impetus for founding Sapien Labs. “

The survey, which is part of the company’s Mental Health Million project, is an ongoing research initiative that makes data freely available to other researchers.

The investigators developed a “free and anonymous assessment tool,” the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ), which “encompasses a comprehensive view of our emotional, social, and cognitive function and capability,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

The MHQ consists of 47 “elements of mental well-being.” Respondents’ MHQ scores ranged from –100 to +200. Negative scores indicate poorer mental well-being. Respondents were categorized as clinical, at risk, enduring, managing, succeeding, and thriving.

MHQ scores were computed for six “broad dimensions” of mental health: Core cognition, complex cognition, mood and outlook, drive and motivation, social self, and mind-body connection.

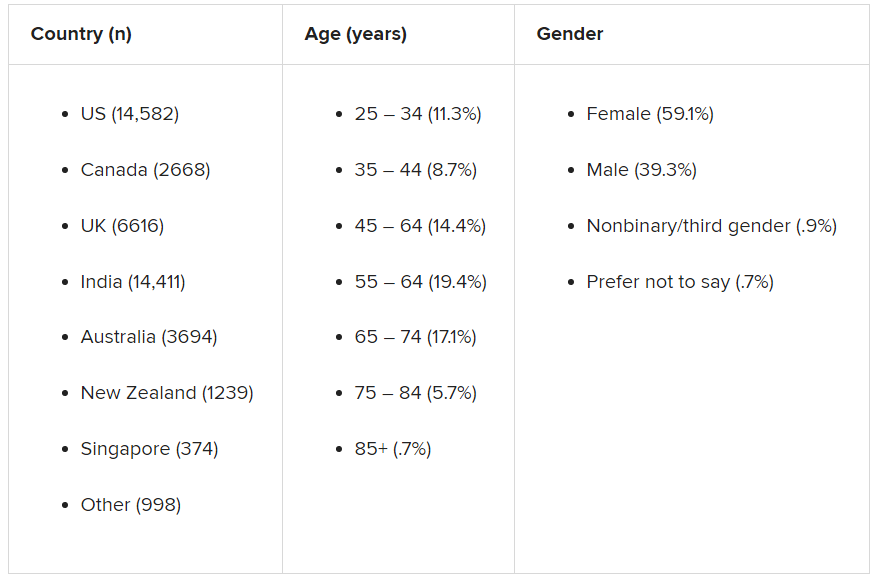

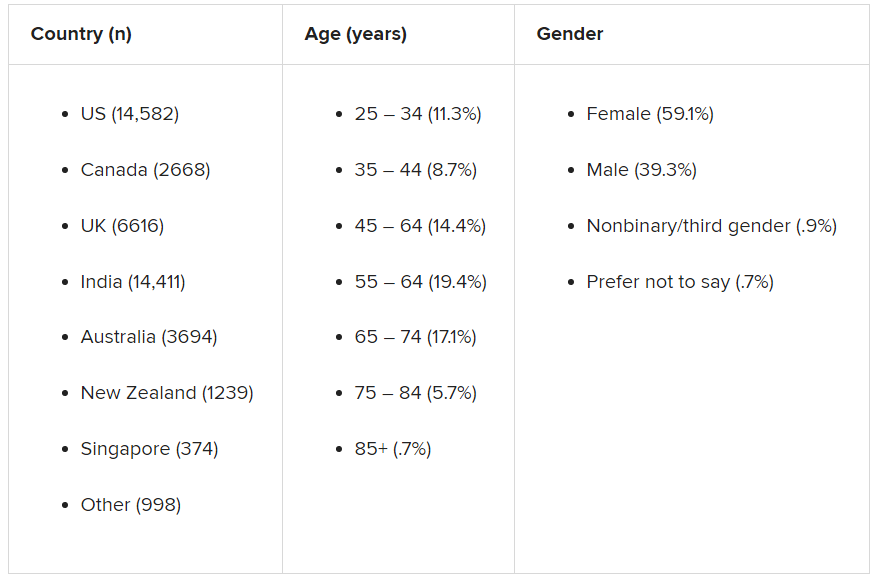

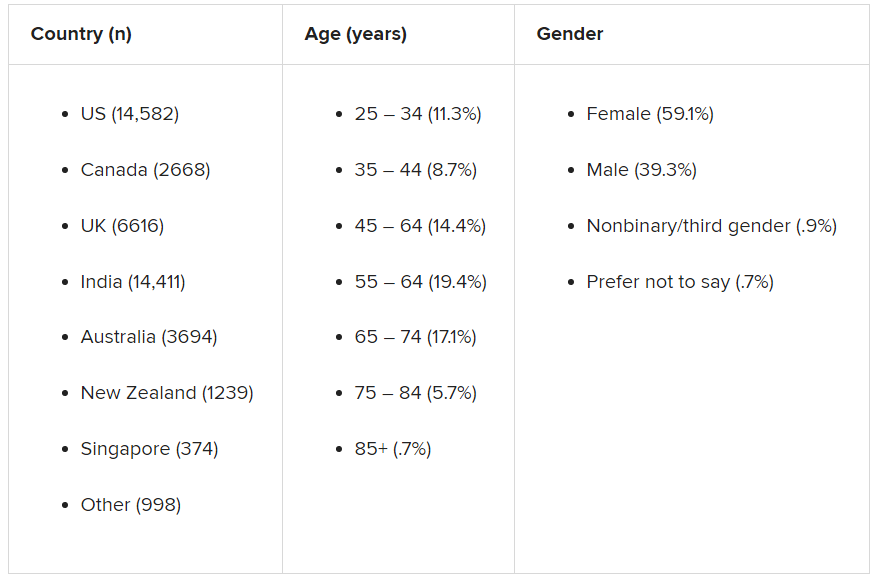

Participants were recruited through advertising on Google and Facebook in eight English-speaking countries – Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and India. The researchers collected demographic information, including age, education, and gender.

First step

The assessment was completed by 48,808 respondents between April 8 and Dec. 31, 2020.

A smaller sample of 2,000 people from the same countries who were polled by the investigators in 2019 was used as a comparator.

Taken together, the overall mental well-being score for 2020 was 8% lower than the score obtained in 2019 from the same countries, and the percentage of respondents who fell into the “clinical” category increased from 14% in 2009 to 26% in 2020.

Residents of Singapore had the highest MHQ score, followed by residents of the United States. At the other extreme, respondents from the United Kingdom and South Africa had the poorest MHQ scores.

“It is important to keep in mind that the English-speaking, Internet-enabled populace is not necessarily representative of each country as a whole,” the authors noted.

Youth hardest hit

whose average MHQ score was 29% lower than those aged at least 65 years.

Worldwide, 70% of respondents aged at least 65 years fell into the categories of “succeeding” or “thriving,” compared with just 17% of those aged 18-24 years.

“We saw a massive trend of diminishing mental well-being in younger individuals, suggesting that some societal force is at play that we need to get to the bottom of,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

“Young people are still learning how to calibrate themselves in the world, and with age comes maturity, leading to a difference in emotional resilience,” she said.

Highest risk group

Mental well-being was poorest among nonbinary/third-gender respondents. Among those persons, more than 50% were classified as being at clinical risk, in comparison with males and females combined, and their MHQ scores were about 47 points lower.

Nonbinary individuals “are universally doing very poorly, relative to males or females,” said Dr. Thiagarajan. “This is a demographic at very high risk with a lot of suicidal thoughts.”

Respondents who had insufficient sleep, who lacked social interaction, and whose level of exercise was insufficient had lower MHQ scores of an “unexpected magnitude,” compared with their counterparts who had sufficient sleep, more social interaction, and more exercise (a discrepancy of 82, 66, and 46 points, respectively).

Only 3.9% of respondents reported having had COVID-19; 0.7% reported having had a severe case. Yet 57% of respondents reported that the pandemic had had negative consequences with regard to their health or their finances or social situation.

Those who were unable to get care for their other health conditions because of the pandemic (2% of all respondents) reported the worst mental well-being, followed by those who struggled for basic necessities (1.4%).

Reduced household income was associated with a 4% lower score but affected a higher percentage of people (17%). Social isolation was associated with a score of about 20 less. Higher rates of lifetime traumas and adversities were likewise associated with lower scores for mental well-being.

Creative, generous approach

Commenting on the survey results, Ken Duckworth, MD, clinical professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and chief medical officer of the National Alliance of Mental Illness, noted that the findings were similar to findings from studies in the United States, which showed disproportionately higher rates of mental health problems in younger individuals. Dr. Duckworth was not involved with the survey.

“The idea that this is an international phenomenon and the broad-stroke finding that younger people are suffering across nations is compelling and important for policymakers to look at,” he said.

Dr. Duckworth noted that although the findings are not “representative” of entire populations in a given country, the report is a “first step in a long journey.”

He described the report as “extremely brilliant, creative, and generous, allowing any academician to get access to the data.”

He saw it “less as a definitive report and more as a directionally informative survey that will yield great fruit over time.”

In a comment, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster, said: “One of the important things a document like this highlights is the importance of understanding more where risk [for mental health disorders] is concentrated and what things have occurred or might occur that can buffer against that risk or protect us from it. We see that each nation has similar but also different challenges.”

Dr. Thiagarajan is the founder and chief scientist of Sapien Labs. Her coauthors are employees of Sapien Labs. Dr. Duckworth and Dr. Morganstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey that assessed the mental health impact of COVID-19 across the globe shows high rates of trauma and clinical mood disorders related to the pandemic.

The survey, carried out by Sapien Labs, was conducted in eight English-speaking countries and included 49,000 adults. It showed that 57% of respondents experienced some COVID-19–related adversity or trauma.

Roughly one-quarter showed clinical signs of or were at risk for a mood disorder, and 40% described themselves as “succeeding or thriving.”

Those who reported the poorest mental health were young adults and individuals who experienced financial adversity or were unable to receive care for other medical conditions. Nonbinary gender and not getting enough sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialization also increased the risk for poorer mental well-being.

“The data suggest that there will be long-term fallout from the pandemic on the mental health front,” Tara Thiagarajan, PhD, Sapien Labs founder and chief scientist, said in a press release.

Novel initiative

Dr. Thiagarajan said in an interview that she was running a company that provided microloans to 30,000 villages in India. The company included a research group the goal of which was to understand what predicts success in an individual and in a particular ecosystem, she said – “Why did some villages succeed and others didn’t?”

Dr. Thiagarajan and associates thought that “something big is happening in our life circumstances that causes changes in our brain and felt that we need to understand what they are and how they affect humanity. This was the impetus for founding Sapien Labs. “

The survey, which is part of the company’s Mental Health Million project, is an ongoing research initiative that makes data freely available to other researchers.

The investigators developed a “free and anonymous assessment tool,” the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ), which “encompasses a comprehensive view of our emotional, social, and cognitive function and capability,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

The MHQ consists of 47 “elements of mental well-being.” Respondents’ MHQ scores ranged from –100 to +200. Negative scores indicate poorer mental well-being. Respondents were categorized as clinical, at risk, enduring, managing, succeeding, and thriving.

MHQ scores were computed for six “broad dimensions” of mental health: Core cognition, complex cognition, mood and outlook, drive and motivation, social self, and mind-body connection.

Participants were recruited through advertising on Google and Facebook in eight English-speaking countries – Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and India. The researchers collected demographic information, including age, education, and gender.

First step

The assessment was completed by 48,808 respondents between April 8 and Dec. 31, 2020.

A smaller sample of 2,000 people from the same countries who were polled by the investigators in 2019 was used as a comparator.

Taken together, the overall mental well-being score for 2020 was 8% lower than the score obtained in 2019 from the same countries, and the percentage of respondents who fell into the “clinical” category increased from 14% in 2009 to 26% in 2020.

Residents of Singapore had the highest MHQ score, followed by residents of the United States. At the other extreme, respondents from the United Kingdom and South Africa had the poorest MHQ scores.

“It is important to keep in mind that the English-speaking, Internet-enabled populace is not necessarily representative of each country as a whole,” the authors noted.

Youth hardest hit

whose average MHQ score was 29% lower than those aged at least 65 years.

Worldwide, 70% of respondents aged at least 65 years fell into the categories of “succeeding” or “thriving,” compared with just 17% of those aged 18-24 years.

“We saw a massive trend of diminishing mental well-being in younger individuals, suggesting that some societal force is at play that we need to get to the bottom of,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

“Young people are still learning how to calibrate themselves in the world, and with age comes maturity, leading to a difference in emotional resilience,” she said.

Highest risk group

Mental well-being was poorest among nonbinary/third-gender respondents. Among those persons, more than 50% were classified as being at clinical risk, in comparison with males and females combined, and their MHQ scores were about 47 points lower.

Nonbinary individuals “are universally doing very poorly, relative to males or females,” said Dr. Thiagarajan. “This is a demographic at very high risk with a lot of suicidal thoughts.”

Respondents who had insufficient sleep, who lacked social interaction, and whose level of exercise was insufficient had lower MHQ scores of an “unexpected magnitude,” compared with their counterparts who had sufficient sleep, more social interaction, and more exercise (a discrepancy of 82, 66, and 46 points, respectively).

Only 3.9% of respondents reported having had COVID-19; 0.7% reported having had a severe case. Yet 57% of respondents reported that the pandemic had had negative consequences with regard to their health or their finances or social situation.

Those who were unable to get care for their other health conditions because of the pandemic (2% of all respondents) reported the worst mental well-being, followed by those who struggled for basic necessities (1.4%).

Reduced household income was associated with a 4% lower score but affected a higher percentage of people (17%). Social isolation was associated with a score of about 20 less. Higher rates of lifetime traumas and adversities were likewise associated with lower scores for mental well-being.

Creative, generous approach

Commenting on the survey results, Ken Duckworth, MD, clinical professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and chief medical officer of the National Alliance of Mental Illness, noted that the findings were similar to findings from studies in the United States, which showed disproportionately higher rates of mental health problems in younger individuals. Dr. Duckworth was not involved with the survey.

“The idea that this is an international phenomenon and the broad-stroke finding that younger people are suffering across nations is compelling and important for policymakers to look at,” he said.

Dr. Duckworth noted that although the findings are not “representative” of entire populations in a given country, the report is a “first step in a long journey.”

He described the report as “extremely brilliant, creative, and generous, allowing any academician to get access to the data.”

He saw it “less as a definitive report and more as a directionally informative survey that will yield great fruit over time.”

In a comment, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster, said: “One of the important things a document like this highlights is the importance of understanding more where risk [for mental health disorders] is concentrated and what things have occurred or might occur that can buffer against that risk or protect us from it. We see that each nation has similar but also different challenges.”

Dr. Thiagarajan is the founder and chief scientist of Sapien Labs. Her coauthors are employees of Sapien Labs. Dr. Duckworth and Dr. Morganstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey that assessed the mental health impact of COVID-19 across the globe shows high rates of trauma and clinical mood disorders related to the pandemic.

The survey, carried out by Sapien Labs, was conducted in eight English-speaking countries and included 49,000 adults. It showed that 57% of respondents experienced some COVID-19–related adversity or trauma.

Roughly one-quarter showed clinical signs of or were at risk for a mood disorder, and 40% described themselves as “succeeding or thriving.”

Those who reported the poorest mental health were young adults and individuals who experienced financial adversity or were unable to receive care for other medical conditions. Nonbinary gender and not getting enough sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialization also increased the risk for poorer mental well-being.

“The data suggest that there will be long-term fallout from the pandemic on the mental health front,” Tara Thiagarajan, PhD, Sapien Labs founder and chief scientist, said in a press release.

Novel initiative

Dr. Thiagarajan said in an interview that she was running a company that provided microloans to 30,000 villages in India. The company included a research group the goal of which was to understand what predicts success in an individual and in a particular ecosystem, she said – “Why did some villages succeed and others didn’t?”

Dr. Thiagarajan and associates thought that “something big is happening in our life circumstances that causes changes in our brain and felt that we need to understand what they are and how they affect humanity. This was the impetus for founding Sapien Labs. “

The survey, which is part of the company’s Mental Health Million project, is an ongoing research initiative that makes data freely available to other researchers.

The investigators developed a “free and anonymous assessment tool,” the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ), which “encompasses a comprehensive view of our emotional, social, and cognitive function and capability,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

The MHQ consists of 47 “elements of mental well-being.” Respondents’ MHQ scores ranged from –100 to +200. Negative scores indicate poorer mental well-being. Respondents were categorized as clinical, at risk, enduring, managing, succeeding, and thriving.

MHQ scores were computed for six “broad dimensions” of mental health: Core cognition, complex cognition, mood and outlook, drive and motivation, social self, and mind-body connection.

Participants were recruited through advertising on Google and Facebook in eight English-speaking countries – Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and India. The researchers collected demographic information, including age, education, and gender.

First step

The assessment was completed by 48,808 respondents between April 8 and Dec. 31, 2020.

A smaller sample of 2,000 people from the same countries who were polled by the investigators in 2019 was used as a comparator.

Taken together, the overall mental well-being score for 2020 was 8% lower than the score obtained in 2019 from the same countries, and the percentage of respondents who fell into the “clinical” category increased from 14% in 2009 to 26% in 2020.

Residents of Singapore had the highest MHQ score, followed by residents of the United States. At the other extreme, respondents from the United Kingdom and South Africa had the poorest MHQ scores.

“It is important to keep in mind that the English-speaking, Internet-enabled populace is not necessarily representative of each country as a whole,” the authors noted.

Youth hardest hit

whose average MHQ score was 29% lower than those aged at least 65 years.

Worldwide, 70% of respondents aged at least 65 years fell into the categories of “succeeding” or “thriving,” compared with just 17% of those aged 18-24 years.

“We saw a massive trend of diminishing mental well-being in younger individuals, suggesting that some societal force is at play that we need to get to the bottom of,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

“Young people are still learning how to calibrate themselves in the world, and with age comes maturity, leading to a difference in emotional resilience,” she said.

Highest risk group

Mental well-being was poorest among nonbinary/third-gender respondents. Among those persons, more than 50% were classified as being at clinical risk, in comparison with males and females combined, and their MHQ scores were about 47 points lower.

Nonbinary individuals “are universally doing very poorly, relative to males or females,” said Dr. Thiagarajan. “This is a demographic at very high risk with a lot of suicidal thoughts.”

Respondents who had insufficient sleep, who lacked social interaction, and whose level of exercise was insufficient had lower MHQ scores of an “unexpected magnitude,” compared with their counterparts who had sufficient sleep, more social interaction, and more exercise (a discrepancy of 82, 66, and 46 points, respectively).

Only 3.9% of respondents reported having had COVID-19; 0.7% reported having had a severe case. Yet 57% of respondents reported that the pandemic had had negative consequences with regard to their health or their finances or social situation.

Those who were unable to get care for their other health conditions because of the pandemic (2% of all respondents) reported the worst mental well-being, followed by those who struggled for basic necessities (1.4%).

Reduced household income was associated with a 4% lower score but affected a higher percentage of people (17%). Social isolation was associated with a score of about 20 less. Higher rates of lifetime traumas and adversities were likewise associated with lower scores for mental well-being.

Creative, generous approach

Commenting on the survey results, Ken Duckworth, MD, clinical professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and chief medical officer of the National Alliance of Mental Illness, noted that the findings were similar to findings from studies in the United States, which showed disproportionately higher rates of mental health problems in younger individuals. Dr. Duckworth was not involved with the survey.

“The idea that this is an international phenomenon and the broad-stroke finding that younger people are suffering across nations is compelling and important for policymakers to look at,” he said.

Dr. Duckworth noted that although the findings are not “representative” of entire populations in a given country, the report is a “first step in a long journey.”

He described the report as “extremely brilliant, creative, and generous, allowing any academician to get access to the data.”

He saw it “less as a definitive report and more as a directionally informative survey that will yield great fruit over time.”

In a comment, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster, said: “One of the important things a document like this highlights is the importance of understanding more where risk [for mental health disorders] is concentrated and what things have occurred or might occur that can buffer against that risk or protect us from it. We see that each nation has similar but also different challenges.”

Dr. Thiagarajan is the founder and chief scientist of Sapien Labs. Her coauthors are employees of Sapien Labs. Dr. Duckworth and Dr. Morganstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy With Infliximab

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

Practice Points

- Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP) is a rare and severe condition that may lead to complications in both the mother and the fetus. Effective treatment with low impact on the fetus is essential.

- Infliximab, among other biologic agents, may be considered for the rapid clearing of skin lesions in GPPP.

New Approaches in Managing Cellulite: EXPERT INSIGHTS

Tips to share with patients feeling vaccine FOMO

COVID-19 has filled our lives with so many challenges, and now we are faced with a new one. For some of our patients, getting a vaccine appointment feels a lot like winning the lottery.

At first, it might have been easy to be joyful for others’ good fortune, but after weeks and now months of seeing others get vaccinated, patience can wear thin. It also creates an imbalance when one member of a “bubble” is vaccinated and others aren’t. It can be painful to be the one who continues to miss out on activities as those around resume pleasures such as seeing friends, dining out, shopping, and traveling.

So many of our patients are feeling worn down from the chronic stress and are not in the best shape to deal with another issue: the fear of missing out. Yet,

Here are some tips to share with patients who are feeling vaccine envy.

- Acknowledge your feelings. Sure, you want to be happy for those getting vaccinated but it does hurt to be left behind. These feelings are real and deserve space. Share them with a trusted friend or therapist. It is indeed quite upsetting to have to wait. In the United States, we are used to having speedy access to medical care. It is unfortunate that so many have to wait for such an important intervention. You have a right to be upset.

- Express your concern to the family member or friend who is vaccinated. Discuss how it could affect your relationship and activities.

- Focus on what you can control. Double down on efforts to not catch or spread COVID. Vaccines are only one very modern way out of the pandemic. Stick to the basics so you feel a sense of control over your health destiny.

- Take advantage of the remaining days or weeks of quarantine. What did you want to accomplish during your time of limited activity? Did you always want to play the piano? These last slower days or weeks might be a great time to try (over Zoom of course). Have you put off cleaning your closet and organizing your drawers? There is nothing like a deadline to kick us into gear.

- Take your best guess for when you will be vaccinated and start to plan. Start to make those plans for late summer and fall.

- Keep things in perspective. We are ALL so fortunate that several vaccines were developed so quickly. Even if the wait is a few more weeks, an end is in sight. One year ago, we had no idea what lay ahead and the uncertainty caused so much anxiety. Now we can feel hopeful that more “normal days” will be returning soon in a predictable time frame.

- Focus on the herd. By now we know that “we are all in this together.” Although we aren’t leaving at the exact same time, mere months will separate us. The more our friends and family get vaccinated, the safer we all are.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018).

COVID-19 has filled our lives with so many challenges, and now we are faced with a new one. For some of our patients, getting a vaccine appointment feels a lot like winning the lottery.

At first, it might have been easy to be joyful for others’ good fortune, but after weeks and now months of seeing others get vaccinated, patience can wear thin. It also creates an imbalance when one member of a “bubble” is vaccinated and others aren’t. It can be painful to be the one who continues to miss out on activities as those around resume pleasures such as seeing friends, dining out, shopping, and traveling.

So many of our patients are feeling worn down from the chronic stress and are not in the best shape to deal with another issue: the fear of missing out. Yet,

Here are some tips to share with patients who are feeling vaccine envy.

- Acknowledge your feelings. Sure, you want to be happy for those getting vaccinated but it does hurt to be left behind. These feelings are real and deserve space. Share them with a trusted friend or therapist. It is indeed quite upsetting to have to wait. In the United States, we are used to having speedy access to medical care. It is unfortunate that so many have to wait for such an important intervention. You have a right to be upset.

- Express your concern to the family member or friend who is vaccinated. Discuss how it could affect your relationship and activities.

- Focus on what you can control. Double down on efforts to not catch or spread COVID. Vaccines are only one very modern way out of the pandemic. Stick to the basics so you feel a sense of control over your health destiny.

- Take advantage of the remaining days or weeks of quarantine. What did you want to accomplish during your time of limited activity? Did you always want to play the piano? These last slower days or weeks might be a great time to try (over Zoom of course). Have you put off cleaning your closet and organizing your drawers? There is nothing like a deadline to kick us into gear.

- Take your best guess for when you will be vaccinated and start to plan. Start to make those plans for late summer and fall.

- Keep things in perspective. We are ALL so fortunate that several vaccines were developed so quickly. Even if the wait is a few more weeks, an end is in sight. One year ago, we had no idea what lay ahead and the uncertainty caused so much anxiety. Now we can feel hopeful that more “normal days” will be returning soon in a predictable time frame.

- Focus on the herd. By now we know that “we are all in this together.” Although we aren’t leaving at the exact same time, mere months will separate us. The more our friends and family get vaccinated, the safer we all are.

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018).

COVID-19 has filled our lives with so many challenges, and now we are faced with a new one. For some of our patients, getting a vaccine appointment feels a lot like winning the lottery.

At first, it might have been easy to be joyful for others’ good fortune, but after weeks and now months of seeing others get vaccinated, patience can wear thin. It also creates an imbalance when one member of a “bubble” is vaccinated and others aren’t. It can be painful to be the one who continues to miss out on activities as those around resume pleasures such as seeing friends, dining out, shopping, and traveling.

So many of our patients are feeling worn down from the chronic stress and are not in the best shape to deal with another issue: the fear of missing out. Yet,

Here are some tips to share with patients who are feeling vaccine envy.