User login

How family medicine has changed over the past half century

From my residency training graduation date, June 1978, many changes to the family medicine specialty have occurred. These are not due to certification requirements but to the dilution of physician control in health care.

The need to provide more affordable health care by insurance companies while maintaining quality prompted more changes. Additionally, employer-based decisions to change insurance plans, since they were the payer for employer-based health insurance, sometimes yearly, prompted mandatory changes in health insurance.

To achieve hospital-based goals and cost containment the advent and use of hospitalists and the expanded use of physician extenders emerged. While I have some support for these changes, they have redefined elements of the Folsom report, which concluded that every American should have a personal physician to care for them and help integrate them into the health care system.

Changes in the health care delivery system and insurance companies’ need to contain costs, while expanding preventative medicine, coupled with a decreasing number of trained family medicine physicians, represents the background of some of the changes in family medicine over the past 50 years. Managed health care, I believe, was certainly part of the answer to implementing the following recommendation of the Folsom report: every American should have a physician-manager for their health care.

Despite the continual output of new family physicians, a shortage of physicians trained in this specialty remained. Advances in health care, which lengthened life expectancy and the fact that most health insurance companies required its members to name a primary care physician expanded the population requiring primary health care services. This only exacerbated the shortage of family physicians and lowered earning power for doctors practicing family medicine, and it created greater professional demands on family physicians, compared with those in other, more limited-scope specialties. The primary care physician shortage needed to be addressed, prompting a redefinition in the traditional nurse practitioner role.

The expansion of nurse practitioners and physician assistants’ roles

The nursing profession began training advanced-placement nurses and instituted a Doctor of Nurse Practitioner degree. At the same time physician assistants, a program that began while I was a resident, had a further role expansion, including training confined to a single specialty area of medicine. These roles were expanded by state legislators who added them to the list of primary care providers, in some locations, permitting independent practice and placing the physician assistant under the state medical boards and the nurse practitioner and Doctor of Nurse Practitioners under the nursing boards, for expanded regulations and the implementation of the new provider requirements for licensure.

The effects of insurance companies on primary care physicians and patients

When I started practicing medicine the physician was truly the manager of a person’s health care. With the advent of managed health care, that has changed. Physicians are no longer the managers; an uninvited marriage between physician, physician extender, insurance company, employer, and patient jointly controls health care.

Patients are opting for less care at the cheapest price based on incentives driven by cost and abetted by insurance companies and employers. The cost of medications has increased and provider services, coupled with medication and specialty costs have nearly priced many beyond their economic limits to pay. As a result, the patient is not always as committed as their provider to meeting the metrics of their insurance company, especially if that is increasing their out-of-pocket cost.

In addition to usual services, the primary care physician is required to demonstrate the adequacy of services provided through meeting certain practice quality metrics for nearly all insurance carriers, including Medicare and Medicaid. Because meeting these metrics carries a significant economic incentive many practices are retaining fewer noncompliant patients and have opted to bolster their bottom line with the more complaint. This adversely impacts the delivery of primary care to a significant portion of the population.

Patients that reside in poorer neighborhoods, rural areas, as well the marginalized compose a significant portion of many primary care provider’s practices and make up a significant percentage of noncompliant patients. Recognizing that the primary care physician’s overhead is high, coupled with the amount of financial and personal resources put into place to meet metrics, it costs much more to care for the marginalized, poor, and rural populations than easier-to-care for patient groups. This creates a disparity in health care.

A study that revisited the Folsom report concluded that “the 21st century primary care physician must be a true public health professional, forming partnerships and assisting data sharing with community organizations to facilitate healthy changes.” These observations have redefined primary care. This type of medicine is no longer tied to a physician; it is tied to a fairly expensive team of providers, which includes a nurse manager, physician, physician extender, social worker, and in some cases, a pharmacist. The days of mostly solo practitioners are waning and the days of the traditional family medicine residency training requires continuous nuancing, to accommodate the expanded list of practice-related responsibilities assigned to the family doctor.

Low reimbursements rates and high office overhead

The last change I have observed in the practice of family medicine over the past 50 years is a decline in the ratio of reimbursement rate for services to practice expenses. Many practitioners opt out of Medicaid or have certainly curtailed the number of Medicaid recipients on their panel because of its unacceptably low reimbursement rates combined with their high office overhead. The requirements for organizing community resources, including nursing agencies and church and community groups, carry no reimbursement for time invested. The primary care provider is responsible and evaluated on patient outcomes despite the noncompliant behavior of the patient.

What is the future of the primary care physician or provider?

The factors that determine this answer lie in what will be required of the provider and the role of the insurance company in assisting the provider of services. Insurance companies have a responsibility because they receive money to pay for metrics while remaining profitable. They must be brought into the success formula and assist the provider in order for the latter to survive. Currently the primary care provider, in an abundance of caution, is required to seek more specialty services, which drives up the cost of health care. Instead, the insurance company should allow the primary care provider to direct the health care and stop being the manager, approving or disapproving services. In summary, much has happened in family medicine over the past 50 years. The ongoing personal doctor-patient relationship has turned into a doctor-patient-insurance company relationship. The introduction of the third party has created an economic incentive for the physician to meet practice metrics, which sometimes, from the patient’s economic perspective, creates economic hardship.

Some patients enlist a primary care physician in name only but continue to drive their health care by the older model, thanks to the advent of the urgent care centers. These patients see participating in the crisis-care model as resulting in lower out-of-pocket costs. Insurance companies should enlist patient support by expanding their patient education to include the benefits of health, the benefits of meeting quality metrics by their physician, and the necessity of maintaining a compliant doctor-patient relationship. Just as they offer incentives to the primary care practitioner for meeting quality metrics incentives should be offered to those patients that meet quality metrics as well.

In the 21st century, a new model of health care emerged, which includes a primary care practitioner, nurse manager-educator, social worker, and a pharmacist. To deliver quality health care one person can’t be responsible for this burden and do it effectively. Many family practice residencies already use this model and most likely advise their graduates to seek employment where this model exists. Additionally, I am sure that family practice residencies are continually nuanced to achieve the teaching mantra required for successful postgraduate employment and good patient outcomes.

What is the future of family medicine?

The family medicine specialty is represented by a practice that looks at outcome metrics primarily without an incentive for helping the marginalized, poor, homeless, and displaced members of our society.

Urban family medicine, much like what I have practiced in this my 43rd year, is different. My practice community includes every segment of society and my approach lies in the improvement of outcomes from all that I serve. It is my impression that the future of family medicine education must include all members of our society and train residents to effectively care for all, irrespective of economic status, and evolve ways to improve the health outcomes for all.

The federal government, through reimbursement and incentive programs, needs to include such efforts in the model of care for these individuals to reduce the expense burden on the practitioner achieving better practice success and less burnout.

Dr. Betton practices family medicine in Little Rock, Ark. He also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News.

From my residency training graduation date, June 1978, many changes to the family medicine specialty have occurred. These are not due to certification requirements but to the dilution of physician control in health care.

The need to provide more affordable health care by insurance companies while maintaining quality prompted more changes. Additionally, employer-based decisions to change insurance plans, since they were the payer for employer-based health insurance, sometimes yearly, prompted mandatory changes in health insurance.

To achieve hospital-based goals and cost containment the advent and use of hospitalists and the expanded use of physician extenders emerged. While I have some support for these changes, they have redefined elements of the Folsom report, which concluded that every American should have a personal physician to care for them and help integrate them into the health care system.

Changes in the health care delivery system and insurance companies’ need to contain costs, while expanding preventative medicine, coupled with a decreasing number of trained family medicine physicians, represents the background of some of the changes in family medicine over the past 50 years. Managed health care, I believe, was certainly part of the answer to implementing the following recommendation of the Folsom report: every American should have a physician-manager for their health care.

Despite the continual output of new family physicians, a shortage of physicians trained in this specialty remained. Advances in health care, which lengthened life expectancy and the fact that most health insurance companies required its members to name a primary care physician expanded the population requiring primary health care services. This only exacerbated the shortage of family physicians and lowered earning power for doctors practicing family medicine, and it created greater professional demands on family physicians, compared with those in other, more limited-scope specialties. The primary care physician shortage needed to be addressed, prompting a redefinition in the traditional nurse practitioner role.

The expansion of nurse practitioners and physician assistants’ roles

The nursing profession began training advanced-placement nurses and instituted a Doctor of Nurse Practitioner degree. At the same time physician assistants, a program that began while I was a resident, had a further role expansion, including training confined to a single specialty area of medicine. These roles were expanded by state legislators who added them to the list of primary care providers, in some locations, permitting independent practice and placing the physician assistant under the state medical boards and the nurse practitioner and Doctor of Nurse Practitioners under the nursing boards, for expanded regulations and the implementation of the new provider requirements for licensure.

The effects of insurance companies on primary care physicians and patients

When I started practicing medicine the physician was truly the manager of a person’s health care. With the advent of managed health care, that has changed. Physicians are no longer the managers; an uninvited marriage between physician, physician extender, insurance company, employer, and patient jointly controls health care.

Patients are opting for less care at the cheapest price based on incentives driven by cost and abetted by insurance companies and employers. The cost of medications has increased and provider services, coupled with medication and specialty costs have nearly priced many beyond their economic limits to pay. As a result, the patient is not always as committed as their provider to meeting the metrics of their insurance company, especially if that is increasing their out-of-pocket cost.

In addition to usual services, the primary care physician is required to demonstrate the adequacy of services provided through meeting certain practice quality metrics for nearly all insurance carriers, including Medicare and Medicaid. Because meeting these metrics carries a significant economic incentive many practices are retaining fewer noncompliant patients and have opted to bolster their bottom line with the more complaint. This adversely impacts the delivery of primary care to a significant portion of the population.

Patients that reside in poorer neighborhoods, rural areas, as well the marginalized compose a significant portion of many primary care provider’s practices and make up a significant percentage of noncompliant patients. Recognizing that the primary care physician’s overhead is high, coupled with the amount of financial and personal resources put into place to meet metrics, it costs much more to care for the marginalized, poor, and rural populations than easier-to-care for patient groups. This creates a disparity in health care.

A study that revisited the Folsom report concluded that “the 21st century primary care physician must be a true public health professional, forming partnerships and assisting data sharing with community organizations to facilitate healthy changes.” These observations have redefined primary care. This type of medicine is no longer tied to a physician; it is tied to a fairly expensive team of providers, which includes a nurse manager, physician, physician extender, social worker, and in some cases, a pharmacist. The days of mostly solo practitioners are waning and the days of the traditional family medicine residency training requires continuous nuancing, to accommodate the expanded list of practice-related responsibilities assigned to the family doctor.

Low reimbursements rates and high office overhead

The last change I have observed in the practice of family medicine over the past 50 years is a decline in the ratio of reimbursement rate for services to practice expenses. Many practitioners opt out of Medicaid or have certainly curtailed the number of Medicaid recipients on their panel because of its unacceptably low reimbursement rates combined with their high office overhead. The requirements for organizing community resources, including nursing agencies and church and community groups, carry no reimbursement for time invested. The primary care provider is responsible and evaluated on patient outcomes despite the noncompliant behavior of the patient.

What is the future of the primary care physician or provider?

The factors that determine this answer lie in what will be required of the provider and the role of the insurance company in assisting the provider of services. Insurance companies have a responsibility because they receive money to pay for metrics while remaining profitable. They must be brought into the success formula and assist the provider in order for the latter to survive. Currently the primary care provider, in an abundance of caution, is required to seek more specialty services, which drives up the cost of health care. Instead, the insurance company should allow the primary care provider to direct the health care and stop being the manager, approving or disapproving services. In summary, much has happened in family medicine over the past 50 years. The ongoing personal doctor-patient relationship has turned into a doctor-patient-insurance company relationship. The introduction of the third party has created an economic incentive for the physician to meet practice metrics, which sometimes, from the patient’s economic perspective, creates economic hardship.

Some patients enlist a primary care physician in name only but continue to drive their health care by the older model, thanks to the advent of the urgent care centers. These patients see participating in the crisis-care model as resulting in lower out-of-pocket costs. Insurance companies should enlist patient support by expanding their patient education to include the benefits of health, the benefits of meeting quality metrics by their physician, and the necessity of maintaining a compliant doctor-patient relationship. Just as they offer incentives to the primary care practitioner for meeting quality metrics incentives should be offered to those patients that meet quality metrics as well.

In the 21st century, a new model of health care emerged, which includes a primary care practitioner, nurse manager-educator, social worker, and a pharmacist. To deliver quality health care one person can’t be responsible for this burden and do it effectively. Many family practice residencies already use this model and most likely advise their graduates to seek employment where this model exists. Additionally, I am sure that family practice residencies are continually nuanced to achieve the teaching mantra required for successful postgraduate employment and good patient outcomes.

What is the future of family medicine?

The family medicine specialty is represented by a practice that looks at outcome metrics primarily without an incentive for helping the marginalized, poor, homeless, and displaced members of our society.

Urban family medicine, much like what I have practiced in this my 43rd year, is different. My practice community includes every segment of society and my approach lies in the improvement of outcomes from all that I serve. It is my impression that the future of family medicine education must include all members of our society and train residents to effectively care for all, irrespective of economic status, and evolve ways to improve the health outcomes for all.

The federal government, through reimbursement and incentive programs, needs to include such efforts in the model of care for these individuals to reduce the expense burden on the practitioner achieving better practice success and less burnout.

Dr. Betton practices family medicine in Little Rock, Ark. He also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News.

From my residency training graduation date, June 1978, many changes to the family medicine specialty have occurred. These are not due to certification requirements but to the dilution of physician control in health care.

The need to provide more affordable health care by insurance companies while maintaining quality prompted more changes. Additionally, employer-based decisions to change insurance plans, since they were the payer for employer-based health insurance, sometimes yearly, prompted mandatory changes in health insurance.

To achieve hospital-based goals and cost containment the advent and use of hospitalists and the expanded use of physician extenders emerged. While I have some support for these changes, they have redefined elements of the Folsom report, which concluded that every American should have a personal physician to care for them and help integrate them into the health care system.

Changes in the health care delivery system and insurance companies’ need to contain costs, while expanding preventative medicine, coupled with a decreasing number of trained family medicine physicians, represents the background of some of the changes in family medicine over the past 50 years. Managed health care, I believe, was certainly part of the answer to implementing the following recommendation of the Folsom report: every American should have a physician-manager for their health care.

Despite the continual output of new family physicians, a shortage of physicians trained in this specialty remained. Advances in health care, which lengthened life expectancy and the fact that most health insurance companies required its members to name a primary care physician expanded the population requiring primary health care services. This only exacerbated the shortage of family physicians and lowered earning power for doctors practicing family medicine, and it created greater professional demands on family physicians, compared with those in other, more limited-scope specialties. The primary care physician shortage needed to be addressed, prompting a redefinition in the traditional nurse practitioner role.

The expansion of nurse practitioners and physician assistants’ roles

The nursing profession began training advanced-placement nurses and instituted a Doctor of Nurse Practitioner degree. At the same time physician assistants, a program that began while I was a resident, had a further role expansion, including training confined to a single specialty area of medicine. These roles were expanded by state legislators who added them to the list of primary care providers, in some locations, permitting independent practice and placing the physician assistant under the state medical boards and the nurse practitioner and Doctor of Nurse Practitioners under the nursing boards, for expanded regulations and the implementation of the new provider requirements for licensure.

The effects of insurance companies on primary care physicians and patients

When I started practicing medicine the physician was truly the manager of a person’s health care. With the advent of managed health care, that has changed. Physicians are no longer the managers; an uninvited marriage between physician, physician extender, insurance company, employer, and patient jointly controls health care.

Patients are opting for less care at the cheapest price based on incentives driven by cost and abetted by insurance companies and employers. The cost of medications has increased and provider services, coupled with medication and specialty costs have nearly priced many beyond their economic limits to pay. As a result, the patient is not always as committed as their provider to meeting the metrics of their insurance company, especially if that is increasing their out-of-pocket cost.

In addition to usual services, the primary care physician is required to demonstrate the adequacy of services provided through meeting certain practice quality metrics for nearly all insurance carriers, including Medicare and Medicaid. Because meeting these metrics carries a significant economic incentive many practices are retaining fewer noncompliant patients and have opted to bolster their bottom line with the more complaint. This adversely impacts the delivery of primary care to a significant portion of the population.

Patients that reside in poorer neighborhoods, rural areas, as well the marginalized compose a significant portion of many primary care provider’s practices and make up a significant percentage of noncompliant patients. Recognizing that the primary care physician’s overhead is high, coupled with the amount of financial and personal resources put into place to meet metrics, it costs much more to care for the marginalized, poor, and rural populations than easier-to-care for patient groups. This creates a disparity in health care.

A study that revisited the Folsom report concluded that “the 21st century primary care physician must be a true public health professional, forming partnerships and assisting data sharing with community organizations to facilitate healthy changes.” These observations have redefined primary care. This type of medicine is no longer tied to a physician; it is tied to a fairly expensive team of providers, which includes a nurse manager, physician, physician extender, social worker, and in some cases, a pharmacist. The days of mostly solo practitioners are waning and the days of the traditional family medicine residency training requires continuous nuancing, to accommodate the expanded list of practice-related responsibilities assigned to the family doctor.

Low reimbursements rates and high office overhead

The last change I have observed in the practice of family medicine over the past 50 years is a decline in the ratio of reimbursement rate for services to practice expenses. Many practitioners opt out of Medicaid or have certainly curtailed the number of Medicaid recipients on their panel because of its unacceptably low reimbursement rates combined with their high office overhead. The requirements for organizing community resources, including nursing agencies and church and community groups, carry no reimbursement for time invested. The primary care provider is responsible and evaluated on patient outcomes despite the noncompliant behavior of the patient.

What is the future of the primary care physician or provider?

The factors that determine this answer lie in what will be required of the provider and the role of the insurance company in assisting the provider of services. Insurance companies have a responsibility because they receive money to pay for metrics while remaining profitable. They must be brought into the success formula and assist the provider in order for the latter to survive. Currently the primary care provider, in an abundance of caution, is required to seek more specialty services, which drives up the cost of health care. Instead, the insurance company should allow the primary care provider to direct the health care and stop being the manager, approving or disapproving services. In summary, much has happened in family medicine over the past 50 years. The ongoing personal doctor-patient relationship has turned into a doctor-patient-insurance company relationship. The introduction of the third party has created an economic incentive for the physician to meet practice metrics, which sometimes, from the patient’s economic perspective, creates economic hardship.

Some patients enlist a primary care physician in name only but continue to drive their health care by the older model, thanks to the advent of the urgent care centers. These patients see participating in the crisis-care model as resulting in lower out-of-pocket costs. Insurance companies should enlist patient support by expanding their patient education to include the benefits of health, the benefits of meeting quality metrics by their physician, and the necessity of maintaining a compliant doctor-patient relationship. Just as they offer incentives to the primary care practitioner for meeting quality metrics incentives should be offered to those patients that meet quality metrics as well.

In the 21st century, a new model of health care emerged, which includes a primary care practitioner, nurse manager-educator, social worker, and a pharmacist. To deliver quality health care one person can’t be responsible for this burden and do it effectively. Many family practice residencies already use this model and most likely advise their graduates to seek employment where this model exists. Additionally, I am sure that family practice residencies are continually nuanced to achieve the teaching mantra required for successful postgraduate employment and good patient outcomes.

What is the future of family medicine?

The family medicine specialty is represented by a practice that looks at outcome metrics primarily without an incentive for helping the marginalized, poor, homeless, and displaced members of our society.

Urban family medicine, much like what I have practiced in this my 43rd year, is different. My practice community includes every segment of society and my approach lies in the improvement of outcomes from all that I serve. It is my impression that the future of family medicine education must include all members of our society and train residents to effectively care for all, irrespective of economic status, and evolve ways to improve the health outcomes for all.

The federal government, through reimbursement and incentive programs, needs to include such efforts in the model of care for these individuals to reduce the expense burden on the practitioner achieving better practice success and less burnout.

Dr. Betton practices family medicine in Little Rock, Ark. He also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News.

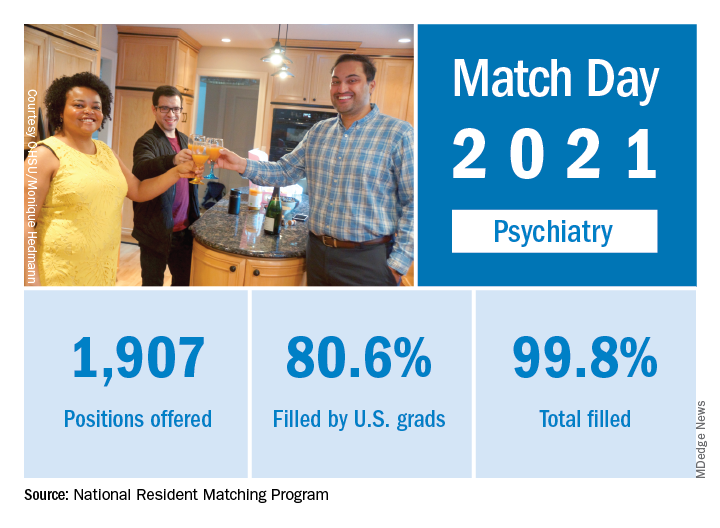

Match Day 2021: Psychiatry continues strong growth

In a record year for the Match, psychiatry residencies filled 99.8% of their available positions in 2021, which were up 2.6% over last year, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

“Rather than faltering in these uncertain times, program fill rates increased across the board,” the NRMP said in a written statement. Overall, the 2021 Main Residency Match offered (35,194) and filled (33,353) more first-year (PGY-1) slots than ever before, for a fill rate of 94.8%, which was up from 94.6% the year before.

Psychiatry offered 1,907 positions in this year’s Match, up by 2.6% over 2020, and filled 1,904, for a 1-year increase of 3.6% and a fill rate of 99.8%. The corresponding PGY-1 numbers for the Match as a whole were 70.4% U.S. and 21.1% international medical graduates, based on NRMP data.

The number of positions offered in psychiatry residencies has increased by 412 (27.6%) since 2017, and such growth over time may “be a predictor of future physician workforce supply,” the NRMP suggested. Psychiatry also increased its share of all available residency positions from 5.1% in 2018 to 5.4% in 2021.

“Concerns about the impact of virtual recruitment on applicants’ matching into PGY-1 positions were not realized,” the NRMP noted, as “growth in registration was seen in every applicant group.” Compared with 2020, submissions of rank-order lists of programs were up by 2.8% for U.S. MD seniors, 7.9% for U.S. DO seniors, 2.5% among U.S.-citizen IMGs, and 15.0% for non–U.S.-citizen IMGs.

“The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” said Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN, president and CEO of the NRMP.

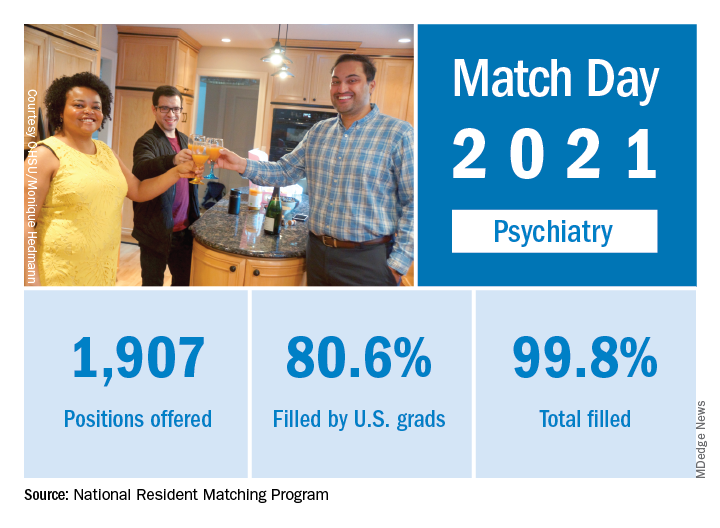

In a record year for the Match, psychiatry residencies filled 99.8% of their available positions in 2021, which were up 2.6% over last year, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

“Rather than faltering in these uncertain times, program fill rates increased across the board,” the NRMP said in a written statement. Overall, the 2021 Main Residency Match offered (35,194) and filled (33,353) more first-year (PGY-1) slots than ever before, for a fill rate of 94.8%, which was up from 94.6% the year before.

Psychiatry offered 1,907 positions in this year’s Match, up by 2.6% over 2020, and filled 1,904, for a 1-year increase of 3.6% and a fill rate of 99.8%. The corresponding PGY-1 numbers for the Match as a whole were 70.4% U.S. and 21.1% international medical graduates, based on NRMP data.

The number of positions offered in psychiatry residencies has increased by 412 (27.6%) since 2017, and such growth over time may “be a predictor of future physician workforce supply,” the NRMP suggested. Psychiatry also increased its share of all available residency positions from 5.1% in 2018 to 5.4% in 2021.

“Concerns about the impact of virtual recruitment on applicants’ matching into PGY-1 positions were not realized,” the NRMP noted, as “growth in registration was seen in every applicant group.” Compared with 2020, submissions of rank-order lists of programs were up by 2.8% for U.S. MD seniors, 7.9% for U.S. DO seniors, 2.5% among U.S.-citizen IMGs, and 15.0% for non–U.S.-citizen IMGs.

“The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” said Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN, president and CEO of the NRMP.

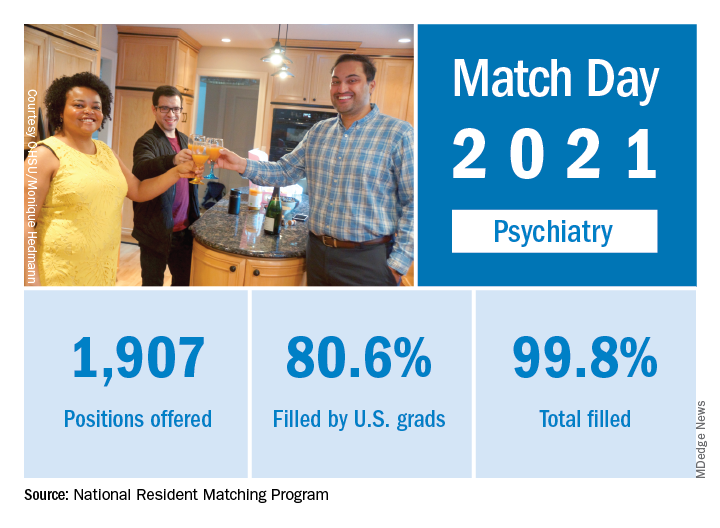

In a record year for the Match, psychiatry residencies filled 99.8% of their available positions in 2021, which were up 2.6% over last year, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

“Rather than faltering in these uncertain times, program fill rates increased across the board,” the NRMP said in a written statement. Overall, the 2021 Main Residency Match offered (35,194) and filled (33,353) more first-year (PGY-1) slots than ever before, for a fill rate of 94.8%, which was up from 94.6% the year before.

Psychiatry offered 1,907 positions in this year’s Match, up by 2.6% over 2020, and filled 1,904, for a 1-year increase of 3.6% and a fill rate of 99.8%. The corresponding PGY-1 numbers for the Match as a whole were 70.4% U.S. and 21.1% international medical graduates, based on NRMP data.

The number of positions offered in psychiatry residencies has increased by 412 (27.6%) since 2017, and such growth over time may “be a predictor of future physician workforce supply,” the NRMP suggested. Psychiatry also increased its share of all available residency positions from 5.1% in 2018 to 5.4% in 2021.

“Concerns about the impact of virtual recruitment on applicants’ matching into PGY-1 positions were not realized,” the NRMP noted, as “growth in registration was seen in every applicant group.” Compared with 2020, submissions of rank-order lists of programs were up by 2.8% for U.S. MD seniors, 7.9% for U.S. DO seniors, 2.5% among U.S.-citizen IMGs, and 15.0% for non–U.S.-citizen IMGs.

“The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” said Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN, president and CEO of the NRMP.

Diabetes prevention moves toward reality as studies published

Two newly published studies highlight recent success toward delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes in people at high risk and slowing progression in those with recent onset of the condition.

Both studies were initially presented in June 2020 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association and reported by this news organization at the time.

As yet, neither of the two strategies – preserving insulin-producing pancreatic beta-cell function soon after diagnosis or delaying type 1 diabetes onset in those at high risk – represent a cure or certain disease prevention.

However, both can potentially lead to better long-term glycemic control with less hypoglycemia and a lower risk for diabetes-related complications.

Combination treatment prolongs beta-cell function in new-onset disease

The first study, entitled, “Anti–interleukin-21 antibody and liraglutide for the preservation of beta-cell function in adults with recent-onset type 1 diabetes,” was published online March 1, 2021, in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology by Matthias von Herrath, MD, of Novo Nordisk, Søborg, Denmark, and colleagues.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 combination treatment trial involved 308 individuals aged 18-45 years who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in the previous 20 weeks and still had residual beta-cell function.

Patients were randomized with 77 per group to receive monoclonal anti-IL-21 plus liraglutide, anti-IL-21 alone, liraglutide alone, or placebo. The antibody was given intravenously every 6 weeks and liraglutide or matching placebo were self-administered by daily injections.

Compared with placebo (ratio to baseline, 0.61; 39% decrease), the decrease in mixed meal tolerance test stimulated C-peptide concentration from baseline to week 54 – the primary outcome – was significantly smaller with combination treatment (0.90, 10% decrease; estimated treatment ratio, 1.48; P = .0017), but not with anti-IL-21 alone (1.23; P = .093) or liraglutide alone (1.12; P = .38).

Despite greater insulin use in the placebo group, the decrease in hemoglobin A1c (a key secondary outcome) at week 54 was greater with all active treatments (–0.50 percentage points) than with placebo (–0.10 percentage points), although the differences versus placebo were not significant.

“The combination of anti-IL-21 and liraglutide could preserve beta-cell function in recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes,” the researchers said.

“These results suggest that this combination has the potential to offer a novel and valuable disease-modifying therapy for patients with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes. However, the efficacy and safety need to be further investigated in a phase 3 program,” Dr. von Herrath and colleagues concluded.

Teplizumab: 3-year data continue to show benefit

The other study looked at delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes. Entitled, “Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals,” the article was published online March 3, 2021, in Science Translational Medicine by Emily K. Sims, MD, of the department of pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues.

This trial of the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody adds an additional year of follow-up to the “game-changer” 2-year data reported in 2019.

Among the 76 individuals aged 8-49 years who were positive for two or more type 1 diabetes–related autoantibodies, 50% of those randomized to a single 14-day infusion course of teplizumab remained diabetes free at a median follow-up of 923 days, compared with only 22% of those who received placebo infusions (hazard ratio, 0.457; P = .01).

The teplizumab group had a greater average C-peptide area under the curve, compared with placebo, reflecting improved beta-cell function (1.96 vs 1.68 pmol/mL; P = .006).

C-peptide levels declined over time in the placebo group but stabilized in those receiving teplizumab (P = .0015).

“It is very encouraging to see that a single course of teplizumab delayed insulin dependence in this high-risk population for approximately 3 years versus placebo,” said Frank Martin, PhD, JDRF director of research at Provention Bio, which is developing teplizumab.

“These exciting results have been made possible by the unwavering efforts of TrialNet and Provention Bio. Teplizumab, if approved by the FDA, could positively change the course of disease development for people at risk of developing T1D and their standard of care,” he concluded.

The teplizumab study was funded by TrialNet. Dr. von Herrath is an employee of Novo Nordisk, which funded the study involving its drug liraglutide. Dr. Sims reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two newly published studies highlight recent success toward delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes in people at high risk and slowing progression in those with recent onset of the condition.

Both studies were initially presented in June 2020 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association and reported by this news organization at the time.

As yet, neither of the two strategies – preserving insulin-producing pancreatic beta-cell function soon after diagnosis or delaying type 1 diabetes onset in those at high risk – represent a cure or certain disease prevention.

However, both can potentially lead to better long-term glycemic control with less hypoglycemia and a lower risk for diabetes-related complications.

Combination treatment prolongs beta-cell function in new-onset disease

The first study, entitled, “Anti–interleukin-21 antibody and liraglutide for the preservation of beta-cell function in adults with recent-onset type 1 diabetes,” was published online March 1, 2021, in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology by Matthias von Herrath, MD, of Novo Nordisk, Søborg, Denmark, and colleagues.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 combination treatment trial involved 308 individuals aged 18-45 years who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in the previous 20 weeks and still had residual beta-cell function.

Patients were randomized with 77 per group to receive monoclonal anti-IL-21 plus liraglutide, anti-IL-21 alone, liraglutide alone, or placebo. The antibody was given intravenously every 6 weeks and liraglutide or matching placebo were self-administered by daily injections.

Compared with placebo (ratio to baseline, 0.61; 39% decrease), the decrease in mixed meal tolerance test stimulated C-peptide concentration from baseline to week 54 – the primary outcome – was significantly smaller with combination treatment (0.90, 10% decrease; estimated treatment ratio, 1.48; P = .0017), but not with anti-IL-21 alone (1.23; P = .093) or liraglutide alone (1.12; P = .38).

Despite greater insulin use in the placebo group, the decrease in hemoglobin A1c (a key secondary outcome) at week 54 was greater with all active treatments (–0.50 percentage points) than with placebo (–0.10 percentage points), although the differences versus placebo were not significant.

“The combination of anti-IL-21 and liraglutide could preserve beta-cell function in recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes,” the researchers said.

“These results suggest that this combination has the potential to offer a novel and valuable disease-modifying therapy for patients with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes. However, the efficacy and safety need to be further investigated in a phase 3 program,” Dr. von Herrath and colleagues concluded.

Teplizumab: 3-year data continue to show benefit

The other study looked at delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes. Entitled, “Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals,” the article was published online March 3, 2021, in Science Translational Medicine by Emily K. Sims, MD, of the department of pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues.

This trial of the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody adds an additional year of follow-up to the “game-changer” 2-year data reported in 2019.

Among the 76 individuals aged 8-49 years who were positive for two or more type 1 diabetes–related autoantibodies, 50% of those randomized to a single 14-day infusion course of teplizumab remained diabetes free at a median follow-up of 923 days, compared with only 22% of those who received placebo infusions (hazard ratio, 0.457; P = .01).

The teplizumab group had a greater average C-peptide area under the curve, compared with placebo, reflecting improved beta-cell function (1.96 vs 1.68 pmol/mL; P = .006).

C-peptide levels declined over time in the placebo group but stabilized in those receiving teplizumab (P = .0015).

“It is very encouraging to see that a single course of teplizumab delayed insulin dependence in this high-risk population for approximately 3 years versus placebo,” said Frank Martin, PhD, JDRF director of research at Provention Bio, which is developing teplizumab.

“These exciting results have been made possible by the unwavering efforts of TrialNet and Provention Bio. Teplizumab, if approved by the FDA, could positively change the course of disease development for people at risk of developing T1D and their standard of care,” he concluded.

The teplizumab study was funded by TrialNet. Dr. von Herrath is an employee of Novo Nordisk, which funded the study involving its drug liraglutide. Dr. Sims reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two newly published studies highlight recent success toward delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes in people at high risk and slowing progression in those with recent onset of the condition.

Both studies were initially presented in June 2020 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association and reported by this news organization at the time.

As yet, neither of the two strategies – preserving insulin-producing pancreatic beta-cell function soon after diagnosis or delaying type 1 diabetes onset in those at high risk – represent a cure or certain disease prevention.

However, both can potentially lead to better long-term glycemic control with less hypoglycemia and a lower risk for diabetes-related complications.

Combination treatment prolongs beta-cell function in new-onset disease

The first study, entitled, “Anti–interleukin-21 antibody and liraglutide for the preservation of beta-cell function in adults with recent-onset type 1 diabetes,” was published online March 1, 2021, in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology by Matthias von Herrath, MD, of Novo Nordisk, Søborg, Denmark, and colleagues.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 combination treatment trial involved 308 individuals aged 18-45 years who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in the previous 20 weeks and still had residual beta-cell function.

Patients were randomized with 77 per group to receive monoclonal anti-IL-21 plus liraglutide, anti-IL-21 alone, liraglutide alone, or placebo. The antibody was given intravenously every 6 weeks and liraglutide or matching placebo were self-administered by daily injections.

Compared with placebo (ratio to baseline, 0.61; 39% decrease), the decrease in mixed meal tolerance test stimulated C-peptide concentration from baseline to week 54 – the primary outcome – was significantly smaller with combination treatment (0.90, 10% decrease; estimated treatment ratio, 1.48; P = .0017), but not with anti-IL-21 alone (1.23; P = .093) or liraglutide alone (1.12; P = .38).

Despite greater insulin use in the placebo group, the decrease in hemoglobin A1c (a key secondary outcome) at week 54 was greater with all active treatments (–0.50 percentage points) than with placebo (–0.10 percentage points), although the differences versus placebo were not significant.

“The combination of anti-IL-21 and liraglutide could preserve beta-cell function in recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes,” the researchers said.

“These results suggest that this combination has the potential to offer a novel and valuable disease-modifying therapy for patients with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes. However, the efficacy and safety need to be further investigated in a phase 3 program,” Dr. von Herrath and colleagues concluded.

Teplizumab: 3-year data continue to show benefit

The other study looked at delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes. Entitled, “Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals,” the article was published online March 3, 2021, in Science Translational Medicine by Emily K. Sims, MD, of the department of pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues.

This trial of the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody adds an additional year of follow-up to the “game-changer” 2-year data reported in 2019.

Among the 76 individuals aged 8-49 years who were positive for two or more type 1 diabetes–related autoantibodies, 50% of those randomized to a single 14-day infusion course of teplizumab remained diabetes free at a median follow-up of 923 days, compared with only 22% of those who received placebo infusions (hazard ratio, 0.457; P = .01).

The teplizumab group had a greater average C-peptide area under the curve, compared with placebo, reflecting improved beta-cell function (1.96 vs 1.68 pmol/mL; P = .006).

C-peptide levels declined over time in the placebo group but stabilized in those receiving teplizumab (P = .0015).

“It is very encouraging to see that a single course of teplizumab delayed insulin dependence in this high-risk population for approximately 3 years versus placebo,” said Frank Martin, PhD, JDRF director of research at Provention Bio, which is developing teplizumab.

“These exciting results have been made possible by the unwavering efforts of TrialNet and Provention Bio. Teplizumab, if approved by the FDA, could positively change the course of disease development for people at risk of developing T1D and their standard of care,” he concluded.

The teplizumab study was funded by TrialNet. Dr. von Herrath is an employee of Novo Nordisk, which funded the study involving its drug liraglutide. Dr. Sims reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ultraprocessed foods, many marketed as healthy, raise CVD risk

Eating ultraprocessed foods poses a significant risk to cardiovascular and coronary heart health, according to prospective data from about 3,000 people in the Framingham Offspring Cohort, the second generation of participants in the Framingham Heart Study.

Each regular, daily serving of ultraprocessed food was linked with significant elevations of 5%-9% in the relative rates of “hard” cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, hard coronary heart disease (CHD) events, overall CVD events, and CVD death, after adjustments for numerous potential confounders including energy intake, body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure, Filippa Juul, PhD, and associates wrote in a report published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Consumption of ultraprocessed foods makes up over half of the daily calories in the average American diet and are increasingly consumed worldwide. As poor diet is a major modifiable risk factor for heart disease, it represents a critical target in prevention efforts,” said Dr. Juul, a nutritional epidemiologist at New York University, in a statement released by the American College of Cardiology.

“Our findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting cardiovascular benefits of limiting ultraprocessed foods. Ultraprocessed foods are ubiquitous and include many foods that are marketed as healthy, such as protein bars, breakfast cereals, and most industrially produced breads,” she added. Other commonplace members of the ultraprocessed food group include carbonated soft drinks, packaged snacks, candies, sausages, margarines, and energy drinks. The concept of ultraprocessed foods as a distinct, wide-ranging, and dangerous food category first appeared in 2010, and then received an update from a United Nations panel in 2019 as what’s now called the NOVA classification system.

Ultraprocessed foods fly under the radar

“Although cardiovascular guidelines emphasize consuming minimally processed foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts, they give less attention to the importance of minimizing ultraprocessed food,” wrote Robert J. Ostfeld, MD, and Kathleen E. Allen, MS, in an editorial that accompanied the new report. This reduced attention may be because of a “paucity of studies examining the association cardiovascular outcomes and ultraprocessed foods.”

The new evidence demands new policies, educational efforts, and labeling changes, suggested Dr. Ostfeld, director of preventive cardiology at Montefiore Health System in New York, and Ms. Allen, a dietitian at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “The goal should be to make the unhealthy choice the hard choice and the healthy choice the easy choice.”

The new analysis used data collected from people enrolled the Framingham Offspring Cohort, with their clinical metrics and diet information collected during 1991-1995 serving as their baseline. After excluding participants with prevalent CVD at baseline and those with incomplete follow-up of CVD events, the researchers had a cohort of 3,003 adults with an average follow-up of 18 years. At baseline, the cohort averaged 54 years of age; 55% were women, their average body mass index was 27.3 kg/m2, and about 6% had diabetes. They reported eating, on average, 7.5 servings of ultraprocessed food daily.

During follow-up, the cohort tallied 648 incident CVD events, including 251 hard CVD events (coronary death, MI, or stroke) and 163 hard CHD events (coronary death or MI), and 713 total deaths including 108 CVD deaths. Other CVD events recorded but not considered hard included heart failure, intermittent claudication, and transient ischemic attack.

In a multivariate-adjusted analysis, each average daily portion of ultraprocessed food was linked with an significant 7% relative increase in the incidence of a hard CVD event, compared with participants who ate fewer ultraprocessed food portions, and a 9% relative increase in the rate of hard CHD events, the study’s two prespecified primary outcomes. The researchers also found that each ultraprocessed serving significantly was associated with a 5% relative increased rate of total CVD events, and a 9% relative rise in CVD deaths. The analysis showed no significant association between total mortality and ultraprocessed food intake. (Average follow-up for the mortality analyses was 20 years.)

The authors also reported endpoint associations with intake of specific types of ultraprocessed foods, and found significantly increased associations specifically for portions of bread, ultraprocessed meat, salty snacks, and low-calorie soft drinks.

Convenient, omnipresent, and affordable

The authors acknowledged that the associations they found need examination in ethnically diverse populations, but nonetheless the findings “suggest the need for increased efforts to implement population-wide strategies” to lower consumption of ultraprocessed foods. “Given the convenience, omnipresence, and affordability of ultraprocessed foods, careful nutrition counseling is needed to design individualized, patient-centered, heart-healthy diets,” they concluded.

“Population-wide strategies such as taxation on sugar-sweetened beverages and other ultraprocessed foods and recommendations regarding processing levels in national dietary guidelines are needed to reduce the intake of ultraprocessed foods,” added Dr. Juul in her statement. “Of course, we must also implement policies that increase the availability, accessibility, and affordability of nutritious, minimally processed foods, especially in disadvantaged populations. At the clinical level, there is a need for increased commitment to individualized nutrition counseling for adopting sustainable heart-healthy diets.”

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Juul and coauthors, Dr. Ostfeld, and Ms. Allen had no disclosures.

Eating ultraprocessed foods poses a significant risk to cardiovascular and coronary heart health, according to prospective data from about 3,000 people in the Framingham Offspring Cohort, the second generation of participants in the Framingham Heart Study.

Each regular, daily serving of ultraprocessed food was linked with significant elevations of 5%-9% in the relative rates of “hard” cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, hard coronary heart disease (CHD) events, overall CVD events, and CVD death, after adjustments for numerous potential confounders including energy intake, body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure, Filippa Juul, PhD, and associates wrote in a report published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Consumption of ultraprocessed foods makes up over half of the daily calories in the average American diet and are increasingly consumed worldwide. As poor diet is a major modifiable risk factor for heart disease, it represents a critical target in prevention efforts,” said Dr. Juul, a nutritional epidemiologist at New York University, in a statement released by the American College of Cardiology.

“Our findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting cardiovascular benefits of limiting ultraprocessed foods. Ultraprocessed foods are ubiquitous and include many foods that are marketed as healthy, such as protein bars, breakfast cereals, and most industrially produced breads,” she added. Other commonplace members of the ultraprocessed food group include carbonated soft drinks, packaged snacks, candies, sausages, margarines, and energy drinks. The concept of ultraprocessed foods as a distinct, wide-ranging, and dangerous food category first appeared in 2010, and then received an update from a United Nations panel in 2019 as what’s now called the NOVA classification system.

Ultraprocessed foods fly under the radar

“Although cardiovascular guidelines emphasize consuming minimally processed foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts, they give less attention to the importance of minimizing ultraprocessed food,” wrote Robert J. Ostfeld, MD, and Kathleen E. Allen, MS, in an editorial that accompanied the new report. This reduced attention may be because of a “paucity of studies examining the association cardiovascular outcomes and ultraprocessed foods.”

The new evidence demands new policies, educational efforts, and labeling changes, suggested Dr. Ostfeld, director of preventive cardiology at Montefiore Health System in New York, and Ms. Allen, a dietitian at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “The goal should be to make the unhealthy choice the hard choice and the healthy choice the easy choice.”

The new analysis used data collected from people enrolled the Framingham Offspring Cohort, with their clinical metrics and diet information collected during 1991-1995 serving as their baseline. After excluding participants with prevalent CVD at baseline and those with incomplete follow-up of CVD events, the researchers had a cohort of 3,003 adults with an average follow-up of 18 years. At baseline, the cohort averaged 54 years of age; 55% were women, their average body mass index was 27.3 kg/m2, and about 6% had diabetes. They reported eating, on average, 7.5 servings of ultraprocessed food daily.

During follow-up, the cohort tallied 648 incident CVD events, including 251 hard CVD events (coronary death, MI, or stroke) and 163 hard CHD events (coronary death or MI), and 713 total deaths including 108 CVD deaths. Other CVD events recorded but not considered hard included heart failure, intermittent claudication, and transient ischemic attack.

In a multivariate-adjusted analysis, each average daily portion of ultraprocessed food was linked with an significant 7% relative increase in the incidence of a hard CVD event, compared with participants who ate fewer ultraprocessed food portions, and a 9% relative increase in the rate of hard CHD events, the study’s two prespecified primary outcomes. The researchers also found that each ultraprocessed serving significantly was associated with a 5% relative increased rate of total CVD events, and a 9% relative rise in CVD deaths. The analysis showed no significant association between total mortality and ultraprocessed food intake. (Average follow-up for the mortality analyses was 20 years.)

The authors also reported endpoint associations with intake of specific types of ultraprocessed foods, and found significantly increased associations specifically for portions of bread, ultraprocessed meat, salty snacks, and low-calorie soft drinks.

Convenient, omnipresent, and affordable

The authors acknowledged that the associations they found need examination in ethnically diverse populations, but nonetheless the findings “suggest the need for increased efforts to implement population-wide strategies” to lower consumption of ultraprocessed foods. “Given the convenience, omnipresence, and affordability of ultraprocessed foods, careful nutrition counseling is needed to design individualized, patient-centered, heart-healthy diets,” they concluded.

“Population-wide strategies such as taxation on sugar-sweetened beverages and other ultraprocessed foods and recommendations regarding processing levels in national dietary guidelines are needed to reduce the intake of ultraprocessed foods,” added Dr. Juul in her statement. “Of course, we must also implement policies that increase the availability, accessibility, and affordability of nutritious, minimally processed foods, especially in disadvantaged populations. At the clinical level, there is a need for increased commitment to individualized nutrition counseling for adopting sustainable heart-healthy diets.”

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Juul and coauthors, Dr. Ostfeld, and Ms. Allen had no disclosures.

Eating ultraprocessed foods poses a significant risk to cardiovascular and coronary heart health, according to prospective data from about 3,000 people in the Framingham Offspring Cohort, the second generation of participants in the Framingham Heart Study.

Each regular, daily serving of ultraprocessed food was linked with significant elevations of 5%-9% in the relative rates of “hard” cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, hard coronary heart disease (CHD) events, overall CVD events, and CVD death, after adjustments for numerous potential confounders including energy intake, body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure, Filippa Juul, PhD, and associates wrote in a report published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Consumption of ultraprocessed foods makes up over half of the daily calories in the average American diet and are increasingly consumed worldwide. As poor diet is a major modifiable risk factor for heart disease, it represents a critical target in prevention efforts,” said Dr. Juul, a nutritional epidemiologist at New York University, in a statement released by the American College of Cardiology.

“Our findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting cardiovascular benefits of limiting ultraprocessed foods. Ultraprocessed foods are ubiquitous and include many foods that are marketed as healthy, such as protein bars, breakfast cereals, and most industrially produced breads,” she added. Other commonplace members of the ultraprocessed food group include carbonated soft drinks, packaged snacks, candies, sausages, margarines, and energy drinks. The concept of ultraprocessed foods as a distinct, wide-ranging, and dangerous food category first appeared in 2010, and then received an update from a United Nations panel in 2019 as what’s now called the NOVA classification system.

Ultraprocessed foods fly under the radar

“Although cardiovascular guidelines emphasize consuming minimally processed foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts, they give less attention to the importance of minimizing ultraprocessed food,” wrote Robert J. Ostfeld, MD, and Kathleen E. Allen, MS, in an editorial that accompanied the new report. This reduced attention may be because of a “paucity of studies examining the association cardiovascular outcomes and ultraprocessed foods.”

The new evidence demands new policies, educational efforts, and labeling changes, suggested Dr. Ostfeld, director of preventive cardiology at Montefiore Health System in New York, and Ms. Allen, a dietitian at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “The goal should be to make the unhealthy choice the hard choice and the healthy choice the easy choice.”

The new analysis used data collected from people enrolled the Framingham Offspring Cohort, with their clinical metrics and diet information collected during 1991-1995 serving as their baseline. After excluding participants with prevalent CVD at baseline and those with incomplete follow-up of CVD events, the researchers had a cohort of 3,003 adults with an average follow-up of 18 years. At baseline, the cohort averaged 54 years of age; 55% were women, their average body mass index was 27.3 kg/m2, and about 6% had diabetes. They reported eating, on average, 7.5 servings of ultraprocessed food daily.

During follow-up, the cohort tallied 648 incident CVD events, including 251 hard CVD events (coronary death, MI, or stroke) and 163 hard CHD events (coronary death or MI), and 713 total deaths including 108 CVD deaths. Other CVD events recorded but not considered hard included heart failure, intermittent claudication, and transient ischemic attack.

In a multivariate-adjusted analysis, each average daily portion of ultraprocessed food was linked with an significant 7% relative increase in the incidence of a hard CVD event, compared with participants who ate fewer ultraprocessed food portions, and a 9% relative increase in the rate of hard CHD events, the study’s two prespecified primary outcomes. The researchers also found that each ultraprocessed serving significantly was associated with a 5% relative increased rate of total CVD events, and a 9% relative rise in CVD deaths. The analysis showed no significant association between total mortality and ultraprocessed food intake. (Average follow-up for the mortality analyses was 20 years.)

The authors also reported endpoint associations with intake of specific types of ultraprocessed foods, and found significantly increased associations specifically for portions of bread, ultraprocessed meat, salty snacks, and low-calorie soft drinks.

Convenient, omnipresent, and affordable

The authors acknowledged that the associations they found need examination in ethnically diverse populations, but nonetheless the findings “suggest the need for increased efforts to implement population-wide strategies” to lower consumption of ultraprocessed foods. “Given the convenience, omnipresence, and affordability of ultraprocessed foods, careful nutrition counseling is needed to design individualized, patient-centered, heart-healthy diets,” they concluded.

“Population-wide strategies such as taxation on sugar-sweetened beverages and other ultraprocessed foods and recommendations regarding processing levels in national dietary guidelines are needed to reduce the intake of ultraprocessed foods,” added Dr. Juul in her statement. “Of course, we must also implement policies that increase the availability, accessibility, and affordability of nutritious, minimally processed foods, especially in disadvantaged populations. At the clinical level, there is a need for increased commitment to individualized nutrition counseling for adopting sustainable heart-healthy diets.”

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Juul and coauthors, Dr. Ostfeld, and Ms. Allen had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Omidubicel improves on umbilical cord blood transplants

Omidubicel, an investigational enriched umbilical cord blood product being developed by Gamida Cell for transplantation in patients with blood cancers, appears to have some advantages over standard umbilical cord blood.

The results come from a global phase 3 trial (NCT02730299) presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation.

“Transplantation with omidubicel, compared to standard cord blood transplantation, results in faster hematopoietic recovery, fewer infections, and fewer days in hospital,” said coinvestigator Guillermo F. Sanz, MD, PhD, from the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic la Fe in Valencia, Spain.

“Omidubicel should be considered as the new standard of care for patients eligible for umbilical cord blood transplantation,” Dr. Sanz concluded.

Zachariah DeFilipp, MD, from Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation specialist who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that “omidubicel significantly improves the engraftment after transplant, as compared to standard cord blood transplant. For patients that lack an HLA-matched donor, this approach can help overcome the prolonged cytopenias that occur with standard cord blood transplants in adults.”

Gamida Cell plans to submit these data for approval of omidubicel by the Food and Drug Administration in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Omidubicel is also being evaluated in a phase 1/2 clinical study in patients with severe aplastic anemia (NCT03173937).

Expanding possibilities

Although umbilical cord blood stem cell grafts come from a readily available source and show greater tolerance across HLA barriers than other sources (such as bone marrow), the relatively low dose of stem cells in each unit results in delayed hematopoietic recovery, increased transplant-related morbidity and mortality, and longer hospitalizations, Dr. Sanz said.

Omidubicel consists of two cryopreserved fractions from a single cord blood unit. The product contains both noncultured CD133-negative cells, including T cells, and CD133-positive cells that are then expanded ex vivo for 21 days in the presence of nicotinamide.

“Nicotinamide increases stem and progenitor cells, inhibits differentiation and increases migration, bone marrow homing, and engraftment efficiency while preserving cellular functionality and phenotype,” Dr. Sanz explained during his presentation.

In an earlier phase 1/2 trial in 36 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies, omidubicel was associated with hematopoietic engraftment lasting at least 10 years.

Details of phase 3 trial results

The global phase 3 trial was conducted in 125 patients (aged 13-65 years) with high-risk malignancies, including acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemias, myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myeloid leukemia, lymphomas, and rare leukemias. These patients were all eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplantation but did not have matched donors.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive hematopoietic reconstitution with either omidubicel (n = 52) or standard cord blood (n = 58).

At 42 days of follow-up, the median time to neutrophil engraftment in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, the primary endpoint, was 12 days with omidubicel versus 22 days with standard cord blood (P < .001).

In the as-treated population – the 108 patients who actually received omidubicel or standard cord blood – median time to engraftment was 10.0 versus 20.5 days, respectively (P < .001).

Rates of neutrophil engraftment at 42 days were 96% with omidubicel versus 89% with standard cord blood.

The secondary endpoint of time-to-platelet engraftment in the ITT population also favored omidubicel, with a cumulative day 42 incidence rate of 55%, compared with 35% with standard cord blood (P = .028).

In the as-treated population, median times to platelet engraftment were 37 days and 50 days, respectively (P = .023). The cumulative rates of platelet engraftment at 100 days of follow-up were 83% and 73%, respectively.

The incidence of grade 2 or 3 bacterial or invasive fungal infections by day 100 in the ITT population was 37% among patients who received omidubicel, compared with 57% for patients who received standard cord blood (P = .027). Viral infections occurred in 10% versus 26% of patients, respectively.

The incidence of acute graft versus host disease at day 100 was similar between treatment groups, and there was no significant difference at 1 year.

Relapse and nonrelapse mortality rates, as well as disease-free and overall survival rates also did not differ between groups.

In the first 100 days post transplant, patients who received omidubicel were alive and out of the hospital for a median of 60.5 days, compared with 48 days for patients who received standard cord blood (P = .005).

The study was funded by Gamida Cell. Dr. Sanz reported receiving research funding from the company and several others, and consulting fees, honoraria, speakers bureau activity, and travel expenses from other companies. Dr. DeFilipp reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Omidubicel, an investigational enriched umbilical cord blood product being developed by Gamida Cell for transplantation in patients with blood cancers, appears to have some advantages over standard umbilical cord blood.

The results come from a global phase 3 trial (NCT02730299) presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation.

“Transplantation with omidubicel, compared to standard cord blood transplantation, results in faster hematopoietic recovery, fewer infections, and fewer days in hospital,” said coinvestigator Guillermo F. Sanz, MD, PhD, from the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic la Fe in Valencia, Spain.

“Omidubicel should be considered as the new standard of care for patients eligible for umbilical cord blood transplantation,” Dr. Sanz concluded.

Zachariah DeFilipp, MD, from Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation specialist who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that “omidubicel significantly improves the engraftment after transplant, as compared to standard cord blood transplant. For patients that lack an HLA-matched donor, this approach can help overcome the prolonged cytopenias that occur with standard cord blood transplants in adults.”

Gamida Cell plans to submit these data for approval of omidubicel by the Food and Drug Administration in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Omidubicel is also being evaluated in a phase 1/2 clinical study in patients with severe aplastic anemia (NCT03173937).

Expanding possibilities

Although umbilical cord blood stem cell grafts come from a readily available source and show greater tolerance across HLA barriers than other sources (such as bone marrow), the relatively low dose of stem cells in each unit results in delayed hematopoietic recovery, increased transplant-related morbidity and mortality, and longer hospitalizations, Dr. Sanz said.

Omidubicel consists of two cryopreserved fractions from a single cord blood unit. The product contains both noncultured CD133-negative cells, including T cells, and CD133-positive cells that are then expanded ex vivo for 21 days in the presence of nicotinamide.

“Nicotinamide increases stem and progenitor cells, inhibits differentiation and increases migration, bone marrow homing, and engraftment efficiency while preserving cellular functionality and phenotype,” Dr. Sanz explained during his presentation.

In an earlier phase 1/2 trial in 36 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies, omidubicel was associated with hematopoietic engraftment lasting at least 10 years.

Details of phase 3 trial results

The global phase 3 trial was conducted in 125 patients (aged 13-65 years) with high-risk malignancies, including acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemias, myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myeloid leukemia, lymphomas, and rare leukemias. These patients were all eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplantation but did not have matched donors.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive hematopoietic reconstitution with either omidubicel (n = 52) or standard cord blood (n = 58).

At 42 days of follow-up, the median time to neutrophil engraftment in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, the primary endpoint, was 12 days with omidubicel versus 22 days with standard cord blood (P < .001).

In the as-treated population – the 108 patients who actually received omidubicel or standard cord blood – median time to engraftment was 10.0 versus 20.5 days, respectively (P < .001).

Rates of neutrophil engraftment at 42 days were 96% with omidubicel versus 89% with standard cord blood.

The secondary endpoint of time-to-platelet engraftment in the ITT population also favored omidubicel, with a cumulative day 42 incidence rate of 55%, compared with 35% with standard cord blood (P = .028).

In the as-treated population, median times to platelet engraftment were 37 days and 50 days, respectively (P = .023). The cumulative rates of platelet engraftment at 100 days of follow-up were 83% and 73%, respectively.

The incidence of grade 2 or 3 bacterial or invasive fungal infections by day 100 in the ITT population was 37% among patients who received omidubicel, compared with 57% for patients who received standard cord blood (P = .027). Viral infections occurred in 10% versus 26% of patients, respectively.

The incidence of acute graft versus host disease at day 100 was similar between treatment groups, and there was no significant difference at 1 year.

Relapse and nonrelapse mortality rates, as well as disease-free and overall survival rates also did not differ between groups.

In the first 100 days post transplant, patients who received omidubicel were alive and out of the hospital for a median of 60.5 days, compared with 48 days for patients who received standard cord blood (P = .005).

The study was funded by Gamida Cell. Dr. Sanz reported receiving research funding from the company and several others, and consulting fees, honoraria, speakers bureau activity, and travel expenses from other companies. Dr. DeFilipp reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Omidubicel, an investigational enriched umbilical cord blood product being developed by Gamida Cell for transplantation in patients with blood cancers, appears to have some advantages over standard umbilical cord blood.

The results come from a global phase 3 trial (NCT02730299) presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation.

“Transplantation with omidubicel, compared to standard cord blood transplantation, results in faster hematopoietic recovery, fewer infections, and fewer days in hospital,” said coinvestigator Guillermo F. Sanz, MD, PhD, from the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic la Fe in Valencia, Spain.

“Omidubicel should be considered as the new standard of care for patients eligible for umbilical cord blood transplantation,” Dr. Sanz concluded.