User login

Intraoperative Tissue Expansion to Allow Primary Linear Closure of 2 Large Adjacent Surgical Defects

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

The Gips Procedure for Pilonidal Disease: A Retrospective Review of Adolescent Patients

Pilonidal disease (PD) is common in Turkey. In a study in Turkey, 19,013 young patients aged 17 to 28 years were examined; PD was detected in 6.6% of patients (0.37% of females in the cohort and 6.23% of males).1 The incidence of PD in military personnel (women 18 years and older; men 22 years and older) is remarkably higher, with an incidence of 9% reported in Turkish soldiers.2

Pilonidal disease has become common in Turkish adolescents, who now experience an increase in desk time because of computer use and a long duration of preparation for high school and university entrance examinations. In adolescent and adult population studies, Yildiz et al3 and Harlak et al4 reported that sitting for 6 hours or more per day was found to significantly increase the risk for PD compared to the control group (P=.028 and P<.001, respectively).

Surgery for PD often is followed by a considerable and unpleasant postoperative course, with a long period of limited physical activity, loss of school time, and reduced social relationships. The recurrence rate of PD is reported to be as high as 40% to 50% after incision and drainage, 40% to 55% with rigorous hygiene and weekly shaving, and as high as 30% following operative intervention. Drawbacks of operative intervention include associated morbidity; lost work and school time; and prolonged wound healing, which can take days to months.5-7

For these reasons, minimally invasive surgical techniques have become popular for treating PD in adolescents, as surgery can cause less disruption of the school and examination schedule and provide an earlier return to normal activities. Gips et al8—who operated on 1358 adults using skin trephines to extirpate pilonidal pits and the underlying fistulous tract and hair debris—reported a low recurrence rate and good postoperative functional outcomes with this technique. Herein, we present our short-duration experience with the Gips procedure of minimally invasive sinusectomy in adolescent PD.

Methods

Patients

We performed a retrospective medical record review of patients with symptomatic PD who were treated in our clinic between January 2018 and February 2019 using the Gips procedure of minimally invasive sinusectomy. We identified 19 patients younger than 17 years. Patients with acute inflammation and an acute undrained collection of pits were treated with incision and drainage, with close clinical follow-up until inflammation resolved. We also recommended that patients take a warm sitz bath at least once daily and chemically epilate the hair in the affected area if they were hirsute.

Gips Procedure

For all patients, the Gips procedure was performed in the left lateral position under general anesthesia using a laryngeal mask airway for anesthesia. Patients were closely shaved (if hirsute) then prepared with povidone-iodine solution. First, each fistulous opening was probed to assess depth and direction of underlying tracts using a thin (0.5–1.0 mm), round-tipped probe. Next, a trephine—comprising a cylindrical blade on a handle—was used to remove cylindrical cores of tissue. All visible median pits and lateral fistulous skin openings were excised using skin trephines of various diameters (Figure, A and B). Once the pilonidal cavity was reached, attention was directed to removing all residual underlying tissue—granulation tissue, debris, and hair—through all available accesses. The cavity was cleaned with hydrogen peroxide and normal saline. Then, all trephine-made openings were left unpacked or were packed for only a few hours and were not sutured (Figure, C and D); a light gauze bandage was eventually applied with a minimum of tape and skin traction. Patients were kept supine during a 1- or 2-hour clinical observation period before they were discharged.

Postoperatively, no regular medications other than analgesics were recommended; routine daily activities were allowed. Patients were encouraged to sleep supine and wash the sacrococcygeal region with running water several times a day after the second postoperative day. Frequent showering, application of povidone-iodine to the wound after defecation, and regular epilation of the sacrococcygeal area also were recommended to all patients.

All patients were routinely followed by the same surgical group weekly until wound healing was complete (Figure, E).

Medical Record Review

Patients’ electronic medical records were reviewed retrospectively, and parameters including age at surgery, surgical history, symptoms, duration of operation and hospital stay, time to return to activity, wound healing time, and recurrence were recorded.

Results

Of the 19 patients who underwent the Gips procedure, 17 (90%) were male; 2 (10%) were female. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) body mass index was 25 (3.7). (Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.) The mean age (SD) of patients was 15 (1.1) years (range, 12–17 years). The most common symptom at presentation was purulent discharge (11/19 [58%]). Other common symptoms included pain (8/19 [42%]), pilonidal abscess (6/19 [32%]), and bleeding (4/19 [21%]). Nine patients (47%) had prior abscess drainage at presentation; 1 (5%) had previously undergone surgery, and 5 (26%) previously had phenol injections.

The median (SD) length of stay in the hospital was 15 (3.2) hours (range, 11–22 hours). The mean (SD) time before returning to daily activities and school was 2 (0.6) days (range, 1–3 days). In our patients, the Gips procedure was performed on either a Thursday or more often a Friday; therefore, patients could be scheduled to be discharged from the hospital and return to home the next day, and then return to school on Monday. All patients were advised to take an oral analgesic for 2 days following the procedure.

The mean (SD) duration of the operative procedure was 14 (3) minutes (range, 10–20 minutes). One patient (5%) developed bleeding that ceased spontaneously. The mean (SD) complete wound healing time was 3 (0.6) weeks (range, 2–4 weeks).

Postoperative clinical examination and telephone interviews were performed for follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 5 months (range, 1–13 months); 17 of 19 patients (89%) made a complete recovery. Two patients (11%) reported recurrence in the third and fourth months following the procedure and were treated with a repeat Gips procedure 6 months after the first treatment. Improvement was noted after a second Gips procedure in 1 of 2 patients who had recurrence, leaving the success rate of the procedure in our practice at 95% (18/19).

Comment

Various treatment methods for PD have been postulated,5-7 including incision and drainage, hair removal and hygiene alone, excision and primary wound closure, excision and secondary wound closure, and various flap techniques. More recently, there has been a dramatic shift to management of patients with PD in an outpatient setting. The Gips procedure, an innovative minimally surgical technique for PD, was introduced in 2008 based on a large consecutive series of more than 1300 patients.8 Studies have shown promising results and minimal recovery time for the Gips procedure in adult and pediatric patients.8-10

Nevertheless, conventional excision down to the sacral fascia, with or without midline or asymmetrical closure, is still the procedure performed most often for PD worldwide.

Advantages of the Gips Procedure

Advantages of the Gips procedure are numerous. It is easily applicable, inexpensive, well tolerated, and requires minimal postoperative care. Placing the patient in the lateral position for the procedure—rather than the prone position that is required for more extensive surgical procedures—is highly feasible, permitting the easy application of a laryngeal mask for anesthesia. The Gips procedure can be performed on patients with severe PD after a period of improved hygiene and hair control and allows for less morbidity than older surgical techniques. Overall, results are satisfactory.

Health services and the hospital admissions process are less costly in university hospitals in Turkey. This procedure costs an average of 400 Turkish liras (<US $50). For that reason, patients in our review were discharged the next day; however, patients could be discharged within a few hours. In the future, it is possible for appropriate cases to be managed in an outpatient setting with sedation and local anesthesia only. Because their postoperative courses are eventless, these patients can be managed without hospitalization.

Recovery is quick and allows for early return to school and other physical activities. Because the procedure was most often performed on the last school day of the week, we did not see any restriction of physical or social activities in our patients.

Lastly, this procedure can be applied to PD patients who have previously undergone extensive surgery or phenol injection, as was the case in our patients.

Conclusion

The Gips procedure is an easy-to-use technique in children and adolescents with PD. It has a high success rate and places fewer restrictions on school and social activities than traditional surgical therapies.

- Duman K, Gırgın M, Harlak A. Prevalence of sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease in Turkey. Asian J Surg. 2017;40:434-437.

- Akinci OF, Bozer M, Uzunköy A, et al. Incidence and aetiological factors in pilonidal sinus among Turkish soldiers. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:339-342.

- Yildiz T, Elmas B, Yucak A, et al. Risk factors for pilonidal sinus disease in teenagers. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:134-138.

- Harlak A, Mentes O, Kilic S, et al. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease: analysis of previously proposed risk factors. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:125-131.

- Delshad HR, Dawson M, Melvin P, et al. Pit-picking resolves pilonidal disease in adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:174-176.

- Humphries AE, Duncan JE. Evaluation and management of pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:113-124.

- Bascom J. Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment. Surgery. 1980;87:567-572.

- Gips M, Melki Y, Salem L, et al. Minimal surgery for pilonidal disease using trephines: description of a new technique and long-term outcomes in 1,358 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1656-1662; discussion, 1662-1663.

- Speter C, Zmora O, Nadler R, et al. Minimal incision as a promising technique for resection of pilonidal sinus in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:1484-1487.

- Di Castro A, Guerra F, Levi Sandri GB, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of pilonidal disease. the Gips procedure on 2347 patients. Int J Surg. 2016;36:201-205.

- Guerra F, Giuliani G, Amore Bonapasta S, et al. Cleft lift versus standard excision with primary midline closure for the treatment of pilonidal disease. a snapshot of worldwide current practice. Eur Surg. 2016;48:269-272.

Pilonidal disease (PD) is common in Turkey. In a study in Turkey, 19,013 young patients aged 17 to 28 years were examined; PD was detected in 6.6% of patients (0.37% of females in the cohort and 6.23% of males).1 The incidence of PD in military personnel (women 18 years and older; men 22 years and older) is remarkably higher, with an incidence of 9% reported in Turkish soldiers.2

Pilonidal disease has become common in Turkish adolescents, who now experience an increase in desk time because of computer use and a long duration of preparation for high school and university entrance examinations. In adolescent and adult population studies, Yildiz et al3 and Harlak et al4 reported that sitting for 6 hours or more per day was found to significantly increase the risk for PD compared to the control group (P=.028 and P<.001, respectively).

Surgery for PD often is followed by a considerable and unpleasant postoperative course, with a long period of limited physical activity, loss of school time, and reduced social relationships. The recurrence rate of PD is reported to be as high as 40% to 50% after incision and drainage, 40% to 55% with rigorous hygiene and weekly shaving, and as high as 30% following operative intervention. Drawbacks of operative intervention include associated morbidity; lost work and school time; and prolonged wound healing, which can take days to months.5-7

For these reasons, minimally invasive surgical techniques have become popular for treating PD in adolescents, as surgery can cause less disruption of the school and examination schedule and provide an earlier return to normal activities. Gips et al8—who operated on 1358 adults using skin trephines to extirpate pilonidal pits and the underlying fistulous tract and hair debris—reported a low recurrence rate and good postoperative functional outcomes with this technique. Herein, we present our short-duration experience with the Gips procedure of minimally invasive sinusectomy in adolescent PD.

Methods

Patients

We performed a retrospective medical record review of patients with symptomatic PD who were treated in our clinic between January 2018 and February 2019 using the Gips procedure of minimally invasive sinusectomy. We identified 19 patients younger than 17 years. Patients with acute inflammation and an acute undrained collection of pits were treated with incision and drainage, with close clinical follow-up until inflammation resolved. We also recommended that patients take a warm sitz bath at least once daily and chemically epilate the hair in the affected area if they were hirsute.

Gips Procedure

For all patients, the Gips procedure was performed in the left lateral position under general anesthesia using a laryngeal mask airway for anesthesia. Patients were closely shaved (if hirsute) then prepared with povidone-iodine solution. First, each fistulous opening was probed to assess depth and direction of underlying tracts using a thin (0.5–1.0 mm), round-tipped probe. Next, a trephine—comprising a cylindrical blade on a handle—was used to remove cylindrical cores of tissue. All visible median pits and lateral fistulous skin openings were excised using skin trephines of various diameters (Figure, A and B). Once the pilonidal cavity was reached, attention was directed to removing all residual underlying tissue—granulation tissue, debris, and hair—through all available accesses. The cavity was cleaned with hydrogen peroxide and normal saline. Then, all trephine-made openings were left unpacked or were packed for only a few hours and were not sutured (Figure, C and D); a light gauze bandage was eventually applied with a minimum of tape and skin traction. Patients were kept supine during a 1- or 2-hour clinical observation period before they were discharged.

Postoperatively, no regular medications other than analgesics were recommended; routine daily activities were allowed. Patients were encouraged to sleep supine and wash the sacrococcygeal region with running water several times a day after the second postoperative day. Frequent showering, application of povidone-iodine to the wound after defecation, and regular epilation of the sacrococcygeal area also were recommended to all patients.

All patients were routinely followed by the same surgical group weekly until wound healing was complete (Figure, E).

Medical Record Review

Patients’ electronic medical records were reviewed retrospectively, and parameters including age at surgery, surgical history, symptoms, duration of operation and hospital stay, time to return to activity, wound healing time, and recurrence were recorded.

Results

Of the 19 patients who underwent the Gips procedure, 17 (90%) were male; 2 (10%) were female. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) body mass index was 25 (3.7). (Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.) The mean age (SD) of patients was 15 (1.1) years (range, 12–17 years). The most common symptom at presentation was purulent discharge (11/19 [58%]). Other common symptoms included pain (8/19 [42%]), pilonidal abscess (6/19 [32%]), and bleeding (4/19 [21%]). Nine patients (47%) had prior abscess drainage at presentation; 1 (5%) had previously undergone surgery, and 5 (26%) previously had phenol injections.

The median (SD) length of stay in the hospital was 15 (3.2) hours (range, 11–22 hours). The mean (SD) time before returning to daily activities and school was 2 (0.6) days (range, 1–3 days). In our patients, the Gips procedure was performed on either a Thursday or more often a Friday; therefore, patients could be scheduled to be discharged from the hospital and return to home the next day, and then return to school on Monday. All patients were advised to take an oral analgesic for 2 days following the procedure.

The mean (SD) duration of the operative procedure was 14 (3) minutes (range, 10–20 minutes). One patient (5%) developed bleeding that ceased spontaneously. The mean (SD) complete wound healing time was 3 (0.6) weeks (range, 2–4 weeks).

Postoperative clinical examination and telephone interviews were performed for follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 5 months (range, 1–13 months); 17 of 19 patients (89%) made a complete recovery. Two patients (11%) reported recurrence in the third and fourth months following the procedure and were treated with a repeat Gips procedure 6 months after the first treatment. Improvement was noted after a second Gips procedure in 1 of 2 patients who had recurrence, leaving the success rate of the procedure in our practice at 95% (18/19).

Comment

Various treatment methods for PD have been postulated,5-7 including incision and drainage, hair removal and hygiene alone, excision and primary wound closure, excision and secondary wound closure, and various flap techniques. More recently, there has been a dramatic shift to management of patients with PD in an outpatient setting. The Gips procedure, an innovative minimally surgical technique for PD, was introduced in 2008 based on a large consecutive series of more than 1300 patients.8 Studies have shown promising results and minimal recovery time for the Gips procedure in adult and pediatric patients.8-10

Nevertheless, conventional excision down to the sacral fascia, with or without midline or asymmetrical closure, is still the procedure performed most often for PD worldwide.

Advantages of the Gips Procedure

Advantages of the Gips procedure are numerous. It is easily applicable, inexpensive, well tolerated, and requires minimal postoperative care. Placing the patient in the lateral position for the procedure—rather than the prone position that is required for more extensive surgical procedures—is highly feasible, permitting the easy application of a laryngeal mask for anesthesia. The Gips procedure can be performed on patients with severe PD after a period of improved hygiene and hair control and allows for less morbidity than older surgical techniques. Overall, results are satisfactory.

Health services and the hospital admissions process are less costly in university hospitals in Turkey. This procedure costs an average of 400 Turkish liras (<US $50). For that reason, patients in our review were discharged the next day; however, patients could be discharged within a few hours. In the future, it is possible for appropriate cases to be managed in an outpatient setting with sedation and local anesthesia only. Because their postoperative courses are eventless, these patients can be managed without hospitalization.

Recovery is quick and allows for early return to school and other physical activities. Because the procedure was most often performed on the last school day of the week, we did not see any restriction of physical or social activities in our patients.

Lastly, this procedure can be applied to PD patients who have previously undergone extensive surgery or phenol injection, as was the case in our patients.

Conclusion

The Gips procedure is an easy-to-use technique in children and adolescents with PD. It has a high success rate and places fewer restrictions on school and social activities than traditional surgical therapies.

Pilonidal disease (PD) is common in Turkey. In a study in Turkey, 19,013 young patients aged 17 to 28 years were examined; PD was detected in 6.6% of patients (0.37% of females in the cohort and 6.23% of males).1 The incidence of PD in military personnel (women 18 years and older; men 22 years and older) is remarkably higher, with an incidence of 9% reported in Turkish soldiers.2

Pilonidal disease has become common in Turkish adolescents, who now experience an increase in desk time because of computer use and a long duration of preparation for high school and university entrance examinations. In adolescent and adult population studies, Yildiz et al3 and Harlak et al4 reported that sitting for 6 hours or more per day was found to significantly increase the risk for PD compared to the control group (P=.028 and P<.001, respectively).

Surgery for PD often is followed by a considerable and unpleasant postoperative course, with a long period of limited physical activity, loss of school time, and reduced social relationships. The recurrence rate of PD is reported to be as high as 40% to 50% after incision and drainage, 40% to 55% with rigorous hygiene and weekly shaving, and as high as 30% following operative intervention. Drawbacks of operative intervention include associated morbidity; lost work and school time; and prolonged wound healing, which can take days to months.5-7

For these reasons, minimally invasive surgical techniques have become popular for treating PD in adolescents, as surgery can cause less disruption of the school and examination schedule and provide an earlier return to normal activities. Gips et al8—who operated on 1358 adults using skin trephines to extirpate pilonidal pits and the underlying fistulous tract and hair debris—reported a low recurrence rate and good postoperative functional outcomes with this technique. Herein, we present our short-duration experience with the Gips procedure of minimally invasive sinusectomy in adolescent PD.

Methods

Patients

We performed a retrospective medical record review of patients with symptomatic PD who were treated in our clinic between January 2018 and February 2019 using the Gips procedure of minimally invasive sinusectomy. We identified 19 patients younger than 17 years. Patients with acute inflammation and an acute undrained collection of pits were treated with incision and drainage, with close clinical follow-up until inflammation resolved. We also recommended that patients take a warm sitz bath at least once daily and chemically epilate the hair in the affected area if they were hirsute.

Gips Procedure

For all patients, the Gips procedure was performed in the left lateral position under general anesthesia using a laryngeal mask airway for anesthesia. Patients were closely shaved (if hirsute) then prepared with povidone-iodine solution. First, each fistulous opening was probed to assess depth and direction of underlying tracts using a thin (0.5–1.0 mm), round-tipped probe. Next, a trephine—comprising a cylindrical blade on a handle—was used to remove cylindrical cores of tissue. All visible median pits and lateral fistulous skin openings were excised using skin trephines of various diameters (Figure, A and B). Once the pilonidal cavity was reached, attention was directed to removing all residual underlying tissue—granulation tissue, debris, and hair—through all available accesses. The cavity was cleaned with hydrogen peroxide and normal saline. Then, all trephine-made openings were left unpacked or were packed for only a few hours and were not sutured (Figure, C and D); a light gauze bandage was eventually applied with a minimum of tape and skin traction. Patients were kept supine during a 1- or 2-hour clinical observation period before they were discharged.

Postoperatively, no regular medications other than analgesics were recommended; routine daily activities were allowed. Patients were encouraged to sleep supine and wash the sacrococcygeal region with running water several times a day after the second postoperative day. Frequent showering, application of povidone-iodine to the wound after defecation, and regular epilation of the sacrococcygeal area also were recommended to all patients.

All patients were routinely followed by the same surgical group weekly until wound healing was complete (Figure, E).

Medical Record Review

Patients’ electronic medical records were reviewed retrospectively, and parameters including age at surgery, surgical history, symptoms, duration of operation and hospital stay, time to return to activity, wound healing time, and recurrence were recorded.

Results

Of the 19 patients who underwent the Gips procedure, 17 (90%) were male; 2 (10%) were female. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) body mass index was 25 (3.7). (Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.) The mean age (SD) of patients was 15 (1.1) years (range, 12–17 years). The most common symptom at presentation was purulent discharge (11/19 [58%]). Other common symptoms included pain (8/19 [42%]), pilonidal abscess (6/19 [32%]), and bleeding (4/19 [21%]). Nine patients (47%) had prior abscess drainage at presentation; 1 (5%) had previously undergone surgery, and 5 (26%) previously had phenol injections.

The median (SD) length of stay in the hospital was 15 (3.2) hours (range, 11–22 hours). The mean (SD) time before returning to daily activities and school was 2 (0.6) days (range, 1–3 days). In our patients, the Gips procedure was performed on either a Thursday or more often a Friday; therefore, patients could be scheduled to be discharged from the hospital and return to home the next day, and then return to school on Monday. All patients were advised to take an oral analgesic for 2 days following the procedure.

The mean (SD) duration of the operative procedure was 14 (3) minutes (range, 10–20 minutes). One patient (5%) developed bleeding that ceased spontaneously. The mean (SD) complete wound healing time was 3 (0.6) weeks (range, 2–4 weeks).

Postoperative clinical examination and telephone interviews were performed for follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 5 months (range, 1–13 months); 17 of 19 patients (89%) made a complete recovery. Two patients (11%) reported recurrence in the third and fourth months following the procedure and were treated with a repeat Gips procedure 6 months after the first treatment. Improvement was noted after a second Gips procedure in 1 of 2 patients who had recurrence, leaving the success rate of the procedure in our practice at 95% (18/19).

Comment

Various treatment methods for PD have been postulated,5-7 including incision and drainage, hair removal and hygiene alone, excision and primary wound closure, excision and secondary wound closure, and various flap techniques. More recently, there has been a dramatic shift to management of patients with PD in an outpatient setting. The Gips procedure, an innovative minimally surgical technique for PD, was introduced in 2008 based on a large consecutive series of more than 1300 patients.8 Studies have shown promising results and minimal recovery time for the Gips procedure in adult and pediatric patients.8-10

Nevertheless, conventional excision down to the sacral fascia, with or without midline or asymmetrical closure, is still the procedure performed most often for PD worldwide.

Advantages of the Gips Procedure

Advantages of the Gips procedure are numerous. It is easily applicable, inexpensive, well tolerated, and requires minimal postoperative care. Placing the patient in the lateral position for the procedure—rather than the prone position that is required for more extensive surgical procedures—is highly feasible, permitting the easy application of a laryngeal mask for anesthesia. The Gips procedure can be performed on patients with severe PD after a period of improved hygiene and hair control and allows for less morbidity than older surgical techniques. Overall, results are satisfactory.

Health services and the hospital admissions process are less costly in university hospitals in Turkey. This procedure costs an average of 400 Turkish liras (<US $50). For that reason, patients in our review were discharged the next day; however, patients could be discharged within a few hours. In the future, it is possible for appropriate cases to be managed in an outpatient setting with sedation and local anesthesia only. Because their postoperative courses are eventless, these patients can be managed without hospitalization.

Recovery is quick and allows for early return to school and other physical activities. Because the procedure was most often performed on the last school day of the week, we did not see any restriction of physical or social activities in our patients.

Lastly, this procedure can be applied to PD patients who have previously undergone extensive surgery or phenol injection, as was the case in our patients.

Conclusion

The Gips procedure is an easy-to-use technique in children and adolescents with PD. It has a high success rate and places fewer restrictions on school and social activities than traditional surgical therapies.

- Duman K, Gırgın M, Harlak A. Prevalence of sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease in Turkey. Asian J Surg. 2017;40:434-437.

- Akinci OF, Bozer M, Uzunköy A, et al. Incidence and aetiological factors in pilonidal sinus among Turkish soldiers. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:339-342.

- Yildiz T, Elmas B, Yucak A, et al. Risk factors for pilonidal sinus disease in teenagers. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:134-138.

- Harlak A, Mentes O, Kilic S, et al. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease: analysis of previously proposed risk factors. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:125-131.

- Delshad HR, Dawson M, Melvin P, et al. Pit-picking resolves pilonidal disease in adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:174-176.

- Humphries AE, Duncan JE. Evaluation and management of pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:113-124.

- Bascom J. Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment. Surgery. 1980;87:567-572.

- Gips M, Melki Y, Salem L, et al. Minimal surgery for pilonidal disease using trephines: description of a new technique and long-term outcomes in 1,358 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1656-1662; discussion, 1662-1663.

- Speter C, Zmora O, Nadler R, et al. Minimal incision as a promising technique for resection of pilonidal sinus in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:1484-1487.

- Di Castro A, Guerra F, Levi Sandri GB, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of pilonidal disease. the Gips procedure on 2347 patients. Int J Surg. 2016;36:201-205.

- Guerra F, Giuliani G, Amore Bonapasta S, et al. Cleft lift versus standard excision with primary midline closure for the treatment of pilonidal disease. a snapshot of worldwide current practice. Eur Surg. 2016;48:269-272.

- Duman K, Gırgın M, Harlak A. Prevalence of sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease in Turkey. Asian J Surg. 2017;40:434-437.

- Akinci OF, Bozer M, Uzunköy A, et al. Incidence and aetiological factors in pilonidal sinus among Turkish soldiers. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:339-342.

- Yildiz T, Elmas B, Yucak A, et al. Risk factors for pilonidal sinus disease in teenagers. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:134-138.

- Harlak A, Mentes O, Kilic S, et al. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease: analysis of previously proposed risk factors. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:125-131.

- Delshad HR, Dawson M, Melvin P, et al. Pit-picking resolves pilonidal disease in adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:174-176.

- Humphries AE, Duncan JE. Evaluation and management of pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:113-124.

- Bascom J. Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment. Surgery. 1980;87:567-572.

- Gips M, Melki Y, Salem L, et al. Minimal surgery for pilonidal disease using trephines: description of a new technique and long-term outcomes in 1,358 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1656-1662; discussion, 1662-1663.

- Speter C, Zmora O, Nadler R, et al. Minimal incision as a promising technique for resection of pilonidal sinus in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:1484-1487.

- Di Castro A, Guerra F, Levi Sandri GB, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of pilonidal disease. the Gips procedure on 2347 patients. Int J Surg. 2016;36:201-205.

- Guerra F, Giuliani G, Amore Bonapasta S, et al. Cleft lift versus standard excision with primary midline closure for the treatment of pilonidal disease. a snapshot of worldwide current practice. Eur Surg. 2016;48:269-272.

Practice Points

- The Gips procedure is an easy-to-use outpatient procedure for adolescents with pilonidal disease.

- This procedure has a high success rate and does not restrict school or social activities.

FIT unfit for inpatient, emergency settings

Most fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) in the hospital setting or the ED are performed for inappropriate indications, according to new data.

“This is the largest study that focuses exclusively on the use of FIT in the ED, inpatient wards, and in the ICU, and it shows significant misuse,” said investigator Umer Bhatti, MD, from Indiana University, Indianapolis.

The only “validated indication” for FIT is to screen for colorectal cancer. However, “99.5% of the FIT tests done in our study were for inappropriate indications,” he reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, where the study was honored with an ACG Presidential Poster Award.

And the inappropriate use of FIT in these settings had no positive effect on clinical decision-making, he added.

For their study, Dr. Bhatti and colleagues looked at all instances of FIT use in their hospital’s electronic medical records from November 2017 to October 2019 to assess how often FIT was being used, the indications for which it was being used, and the impact of its use on clinical care.

They identified 550 patients, 48% of whom were women, who underwent at least one FIT test. Mean age of the study cohort was 54 years. Only three of the tests, or 0.5%, were performed to screen for colorectal cancer (95% confidence interval, 0.09%-1.52%).

Among the indications documented for FIT were anemia in 242 (44.0%) patients, suspected GI bleeding in 225 (40.9%), abdominal pain in 31 (5.6%), and change in bowel habits in 19 (3.5%).

The tests were performed most often in the ED (45.3%) and on the hospital floor (42.2%), but were also performed in the ICU (10.5%) and burn unit (2.0%).

Overall, 297 of the tests, or 54%, were negative, and 253, or 46%, were positive.

“GI consults were obtained in 46.2% of the FIT-positive group, compared with 13.1% of the FIT-negative patients” (odds ratio, 5.93; 95% CI, 3.88-9.04, P < .0001), Dr. Bhatti reported.

Among FIT-positive patients, those with overt bleeding were more likely to receive a GI consultation than those without (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.9-5.5; P < .0001).

Of the 117 FIT-positive patients who underwent a GI consultation, upper endoscopy was a more common outcome than colonoscopy (51.3% vs. 23.1%; P < .0001). Of the 34 patients who underwent colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, one was diagnosed with colorectal cancer and one with advanced adenoma.

Overt GI bleeding was a better predictor of a GI consultation than a positive FIT result. In fact, use of FIT for patients with overt GI bleeding indicates a poor understanding of the test’s utility, the investigators reported.

“For patients with overt GI bleeding, having a positive FIT made no difference on how often a bleeding source was identified on endoscopy, suggesting that FIT should not be used to guide decisions about endoscopy or hospitalization,” Dr. Bhatti said.

In light of these findings, the team urges their peers to consider measures to reduce FIT tests for unnecessary indications.

“We feel that FIT is unfit for use in the inpatient and emergency settings, and measures should be taken to curb its use,” Dr. Bhatti concluded. “We presented our data to our hospital leadership and a decision was made to remove the FIT as an orderable test from the EMR.”

These results are “striking,” said Jennifer Christie, MD, from the University, Atlanta.

“We should be educating our ER providers and inpatient providers about the proper use of FIT,” she said in an interview. “Another option – and this has been done in many settings with the fecal occult blood test – is just take FIT off the units or out of the ER, so providers won’t be tempted to use it as an assessment of these patients. Because often times, as this study showed, it doesn’t really impact outcomes.”

In fact, unnecessary FI testing could put patients at risk for unnecessary procedures. “We also know that calling for an inpatient or ER consult from a gastroenterologist may increase both length of stay and costs,” she added.

Dr. Bhatti and Dr. Christie disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Most fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) in the hospital setting or the ED are performed for inappropriate indications, according to new data.

“This is the largest study that focuses exclusively on the use of FIT in the ED, inpatient wards, and in the ICU, and it shows significant misuse,” said investigator Umer Bhatti, MD, from Indiana University, Indianapolis.

The only “validated indication” for FIT is to screen for colorectal cancer. However, “99.5% of the FIT tests done in our study were for inappropriate indications,” he reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, where the study was honored with an ACG Presidential Poster Award.

And the inappropriate use of FIT in these settings had no positive effect on clinical decision-making, he added.

For their study, Dr. Bhatti and colleagues looked at all instances of FIT use in their hospital’s electronic medical records from November 2017 to October 2019 to assess how often FIT was being used, the indications for which it was being used, and the impact of its use on clinical care.

They identified 550 patients, 48% of whom were women, who underwent at least one FIT test. Mean age of the study cohort was 54 years. Only three of the tests, or 0.5%, were performed to screen for colorectal cancer (95% confidence interval, 0.09%-1.52%).

Among the indications documented for FIT were anemia in 242 (44.0%) patients, suspected GI bleeding in 225 (40.9%), abdominal pain in 31 (5.6%), and change in bowel habits in 19 (3.5%).

The tests were performed most often in the ED (45.3%) and on the hospital floor (42.2%), but were also performed in the ICU (10.5%) and burn unit (2.0%).

Overall, 297 of the tests, or 54%, were negative, and 253, or 46%, were positive.

“GI consults were obtained in 46.2% of the FIT-positive group, compared with 13.1% of the FIT-negative patients” (odds ratio, 5.93; 95% CI, 3.88-9.04, P < .0001), Dr. Bhatti reported.

Among FIT-positive patients, those with overt bleeding were more likely to receive a GI consultation than those without (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.9-5.5; P < .0001).

Of the 117 FIT-positive patients who underwent a GI consultation, upper endoscopy was a more common outcome than colonoscopy (51.3% vs. 23.1%; P < .0001). Of the 34 patients who underwent colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, one was diagnosed with colorectal cancer and one with advanced adenoma.

Overt GI bleeding was a better predictor of a GI consultation than a positive FIT result. In fact, use of FIT for patients with overt GI bleeding indicates a poor understanding of the test’s utility, the investigators reported.

“For patients with overt GI bleeding, having a positive FIT made no difference on how often a bleeding source was identified on endoscopy, suggesting that FIT should not be used to guide decisions about endoscopy or hospitalization,” Dr. Bhatti said.

In light of these findings, the team urges their peers to consider measures to reduce FIT tests for unnecessary indications.

“We feel that FIT is unfit for use in the inpatient and emergency settings, and measures should be taken to curb its use,” Dr. Bhatti concluded. “We presented our data to our hospital leadership and a decision was made to remove the FIT as an orderable test from the EMR.”

These results are “striking,” said Jennifer Christie, MD, from the University, Atlanta.

“We should be educating our ER providers and inpatient providers about the proper use of FIT,” she said in an interview. “Another option – and this has been done in many settings with the fecal occult blood test – is just take FIT off the units or out of the ER, so providers won’t be tempted to use it as an assessment of these patients. Because often times, as this study showed, it doesn’t really impact outcomes.”

In fact, unnecessary FI testing could put patients at risk for unnecessary procedures. “We also know that calling for an inpatient or ER consult from a gastroenterologist may increase both length of stay and costs,” she added.

Dr. Bhatti and Dr. Christie disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Most fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) in the hospital setting or the ED are performed for inappropriate indications, according to new data.

“This is the largest study that focuses exclusively on the use of FIT in the ED, inpatient wards, and in the ICU, and it shows significant misuse,” said investigator Umer Bhatti, MD, from Indiana University, Indianapolis.

The only “validated indication” for FIT is to screen for colorectal cancer. However, “99.5% of the FIT tests done in our study were for inappropriate indications,” he reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, where the study was honored with an ACG Presidential Poster Award.

And the inappropriate use of FIT in these settings had no positive effect on clinical decision-making, he added.

For their study, Dr. Bhatti and colleagues looked at all instances of FIT use in their hospital’s electronic medical records from November 2017 to October 2019 to assess how often FIT was being used, the indications for which it was being used, and the impact of its use on clinical care.

They identified 550 patients, 48% of whom were women, who underwent at least one FIT test. Mean age of the study cohort was 54 years. Only three of the tests, or 0.5%, were performed to screen for colorectal cancer (95% confidence interval, 0.09%-1.52%).

Among the indications documented for FIT were anemia in 242 (44.0%) patients, suspected GI bleeding in 225 (40.9%), abdominal pain in 31 (5.6%), and change in bowel habits in 19 (3.5%).

The tests were performed most often in the ED (45.3%) and on the hospital floor (42.2%), but were also performed in the ICU (10.5%) and burn unit (2.0%).

Overall, 297 of the tests, or 54%, were negative, and 253, or 46%, were positive.

“GI consults were obtained in 46.2% of the FIT-positive group, compared with 13.1% of the FIT-negative patients” (odds ratio, 5.93; 95% CI, 3.88-9.04, P < .0001), Dr. Bhatti reported.

Among FIT-positive patients, those with overt bleeding were more likely to receive a GI consultation than those without (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.9-5.5; P < .0001).

Of the 117 FIT-positive patients who underwent a GI consultation, upper endoscopy was a more common outcome than colonoscopy (51.3% vs. 23.1%; P < .0001). Of the 34 patients who underwent colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, one was diagnosed with colorectal cancer and one with advanced adenoma.

Overt GI bleeding was a better predictor of a GI consultation than a positive FIT result. In fact, use of FIT for patients with overt GI bleeding indicates a poor understanding of the test’s utility, the investigators reported.

“For patients with overt GI bleeding, having a positive FIT made no difference on how often a bleeding source was identified on endoscopy, suggesting that FIT should not be used to guide decisions about endoscopy or hospitalization,” Dr. Bhatti said.

In light of these findings, the team urges their peers to consider measures to reduce FIT tests for unnecessary indications.

“We feel that FIT is unfit for use in the inpatient and emergency settings, and measures should be taken to curb its use,” Dr. Bhatti concluded. “We presented our data to our hospital leadership and a decision was made to remove the FIT as an orderable test from the EMR.”

These results are “striking,” said Jennifer Christie, MD, from the University, Atlanta.

“We should be educating our ER providers and inpatient providers about the proper use of FIT,” she said in an interview. “Another option – and this has been done in many settings with the fecal occult blood test – is just take FIT off the units or out of the ER, so providers won’t be tempted to use it as an assessment of these patients. Because often times, as this study showed, it doesn’t really impact outcomes.”

In fact, unnecessary FI testing could put patients at risk for unnecessary procedures. “We also know that calling for an inpatient or ER consult from a gastroenterologist may increase both length of stay and costs,” she added.

Dr. Bhatti and Dr. Christie disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

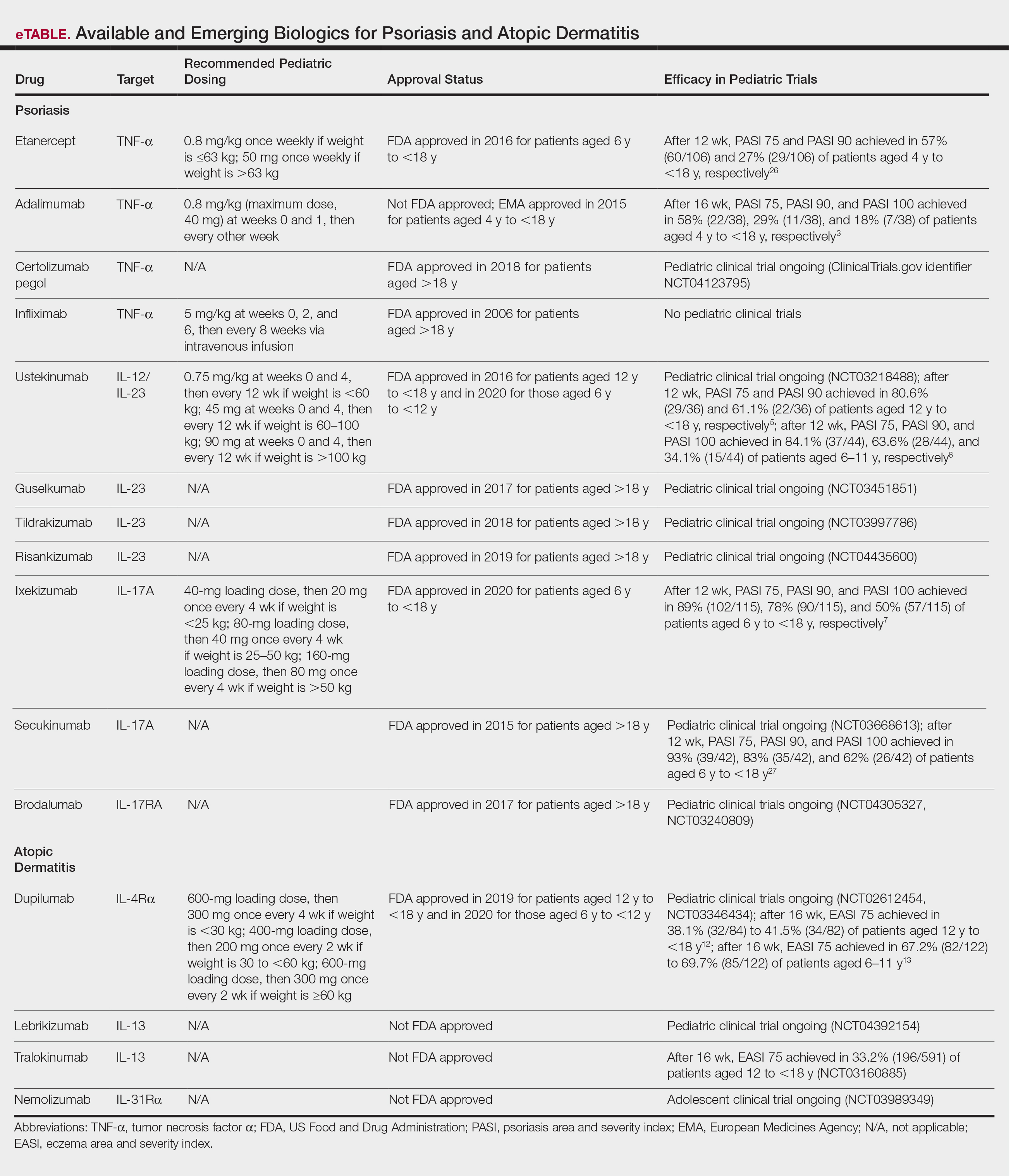

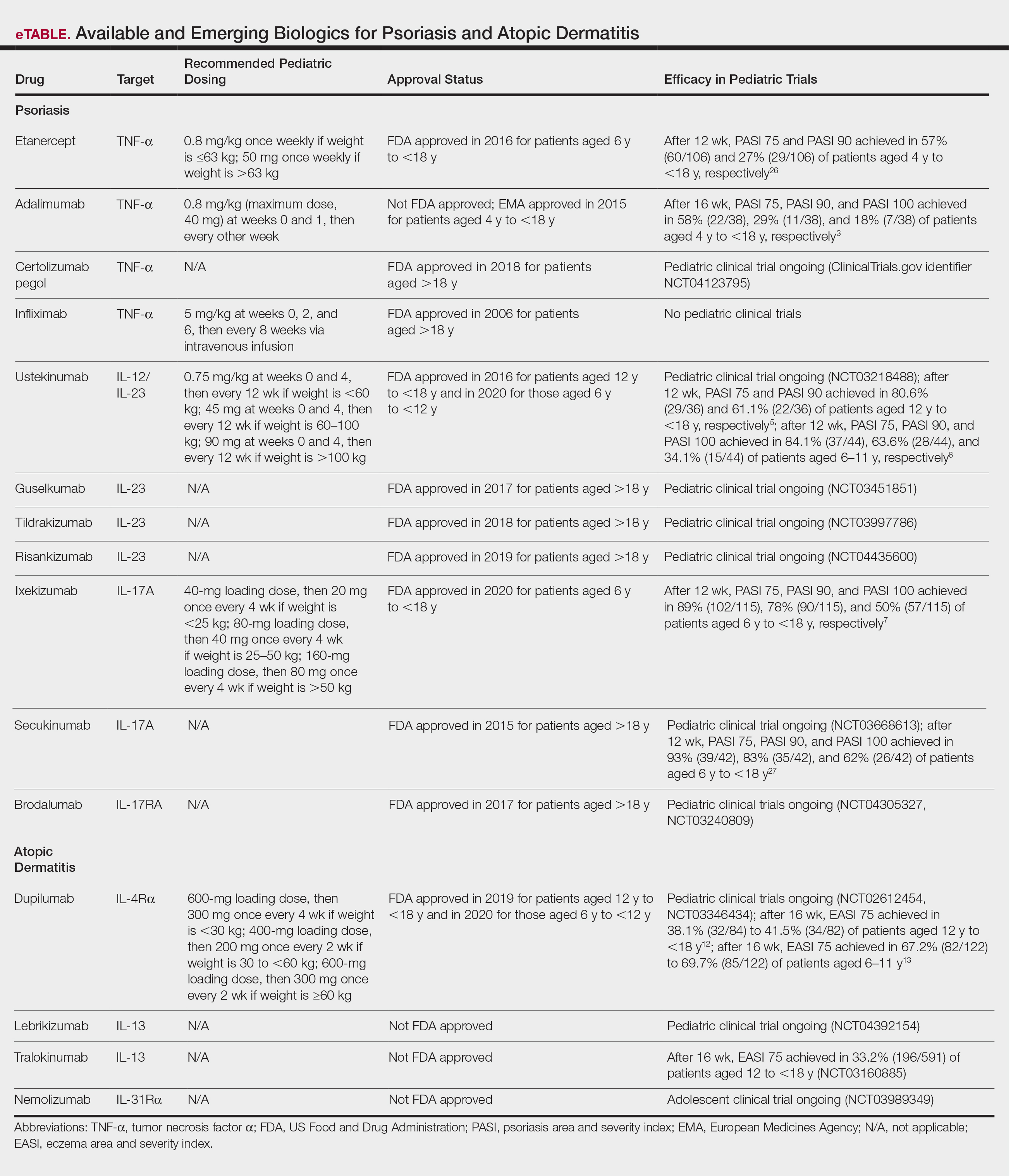

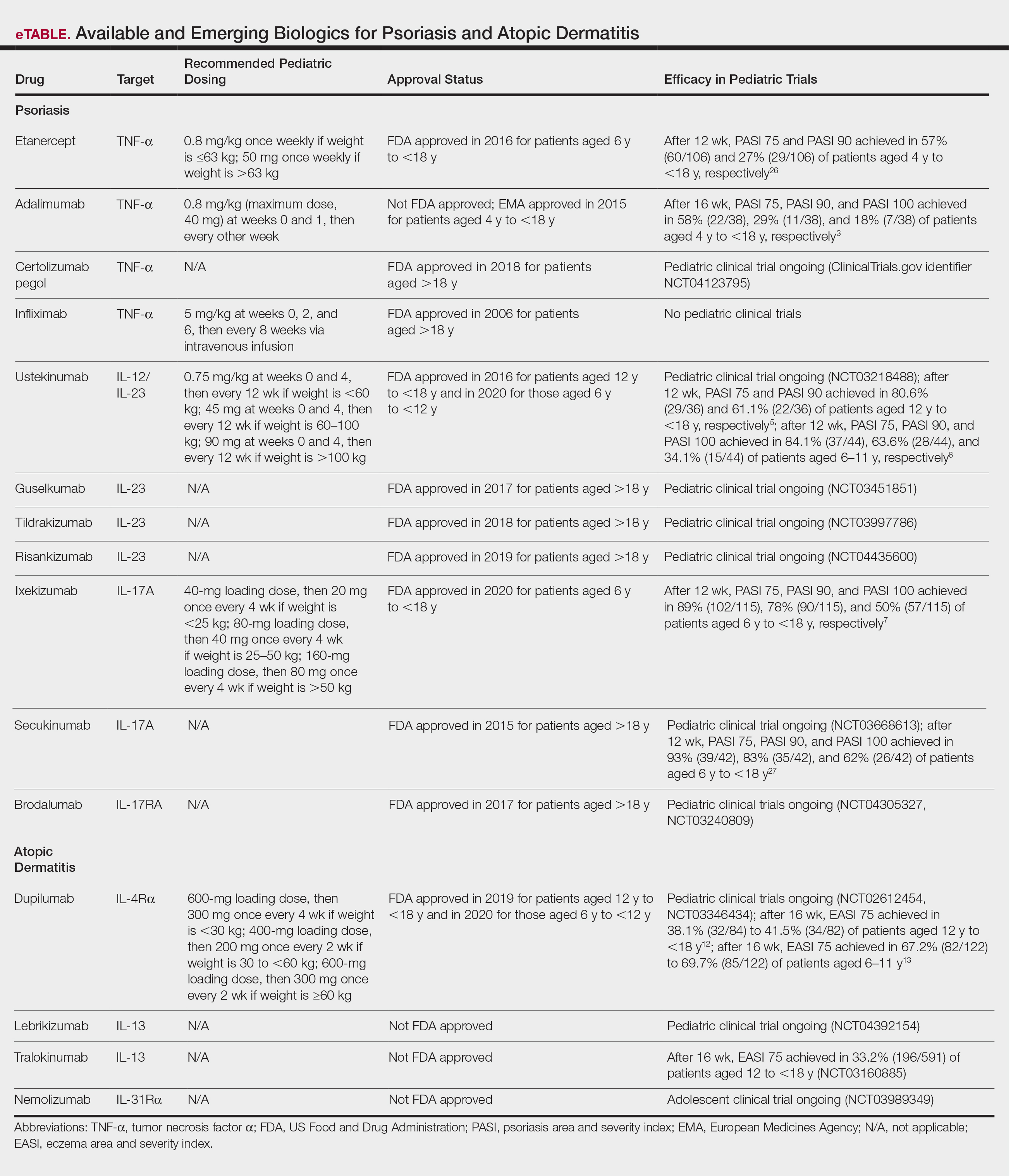

Biologics in Pediatric Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis: Revolutionizing the Treatment Landscape

Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (AD) can impact quality of life (QOL) in pediatric patients, warranting early recognition and treatment.1 Topical agents often are inadequate to treat moderate to severe disease, but the potential toxicity of systemic agents, which largely include immunosuppressives, limit their use in this population despite their effectiveness. Our expanding knowledge of the pathogenesis of psoriasis (tumor necrosis factor [TNF] α and IL-23/TH17 pathways) and AD has led to targeted interventions, particularly monoclonal antibody biologics, which have revolutionized treatment for affected adults and more recently children. Several agents are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric psoriasis, and dupilumab is approved for pediatric AD. Herein, we discuss the latest developments in the treatment landscape for pediatric psoriasis and AD.

Pediatric Psoriasis

Methotrexate (MTX) and cyclosporine have been FDA approved for psoriasis in adults since 1972 and 1997, respectively.2 Before biologics, MTX was the primary systemic agent used to treat pediatric psoriasis, given its lower toxicity vs cyclosporine. The TNF-α inhibitor etanercept became the first FDA-approved biologic for pediatric psoriasis in 2016. Adalimumab has been available in Europe for children since 2015 but is not FDA approved. Certolizumab, a pegylated TNF-α inhibitor that distinctly fails to cross the placental barrier currently is in clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04123795). Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have shown more rapid onset and greater efficacy during the first 16 weeks of use than MTX, including a head-to-head trial comparing MTX to adalimumab.3 A recent real-world study showed that pediatric patients receiving biologics, primarily TNF-α inhibitors, were more likely to achieve psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) 75 or clear/almost clear status (similar to PASI 90) than MTX and had higher drug survival rates.4

Ustekinumab targets both IL-12 and IL-23, which share the IL-23 receptor p40 subunit. It was the first biologic to target IL-23, which promotes the proliferation and survival of helper T cells (TH17). Ustekinumab has led to greater reductions in PASI scores than TNF-α inhibitors.5,6 Pediatric trials of guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab, all targeting the IL-23 receptor–specific p19 subunit, are completed or currently recruiting (NCT03451851, NCT03997786, NCT04435600). Ixekizumab is the first IL-17A–targeting biologic approved for children.7 Secukinumab and the IL-17 receptor inhibitor brodalumab are in pediatric trials (NCT03668613, NCT04305327, NCT03240809). One potential issue with

Skin disease can profoundly affect QOL during childhood and adolescence, a critical time for psychosocial development. In psoriasis, improvement in QOL is proportional to clearance and is greater when PASI 90 is achieved vs PASI 75.8 The high efficacy of IL-23 and IL-17A pathway inhibitors now makes achieving at least PASI 90 the new standard, which can be reached in most patients.

Pediatric AD

For AD in the pediatric population, systemic treatments primarily include corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and MTX. Although cyclosporine was the favored systemic agent among pediatric dermatologists in one study,9 claims data analyses show that systemic corticosteroids are used much more often overall, prescribed in 24.4% (116,635 total cases) of children with AD vs nonsteroidal immunosuppressants in less than 0.5%.10 Systemic steroids are impractical given their side effects and risk for disease rebound; however, no immunosuppressants are safe for long-term use, and all require frequent laboratory monitoring. The development of biologics for AD largely involves targeting TH2-driven inflammation.11 Dupilumab is the only FDA-approved biologic for moderate to severe pediatric AD, including in patients as young as 6 years of age. Dupilumab inhibits activation of the IL-4Rα subunit, thereby blocking responses to its ligands, IL-4 and IL-13. Phase 3 trials are now underway in children aged 6 months to 5 years (NCT02612454, NCT03346434). The concomitant ameliorative effects of dupilumab on asthma and other allergic disorders, occurring in approximately 90% of children with moderate to severe AD, is an added benefit.12 Although dupilumab does not appear to modify the disease course in children with AD, the possibility that early introduction could reduce the risk for later developing allergic disease is intriguing.

Adolescent trials have been started for lebrikizumab (NCT04392154) and have been completed for tralokinumab (NCT03160885). Both agents selectively target IL-13 to block TH2 pathway inflammation. The only reported adverse effects of IL-4Rα and IL-13 inhibitors have been injection-site pain/reactions and increased conjunctivitis.13

The only other biologic for AD currently in clinical trials for adolescents is nemolizumab, targeting the receptor for IL-31, a predominantly TH2 cytokine that causes pruritus (NCT03989349). In adults, nemolizumab has shown rapid and potent suppression of itch (but not inflammation) without adding topical corticosteroids.14

Advantages of Biologics and Laboratory Monitoring

By targeting specific cytokines, biologics have greater and more rapid efficacy, fewer side effects, fewer drug interactions, less frequent dosing, and less immunosuppression compared to other systemic agents.3,4,15,16

Recent pediatric-specific guidelines for psoriasis recommend baseline monitoring for tuberculosis for all biologics but yearly tuberculosis testing only for TNF-α inhibitors unless the individual patient is at increased risk.2 No tuberculosis testing is needed for dupilumab, and no other laboratory monitoring is recommended for any biologic in children unless warranted by risk. This difference in recommended monitoring suggests the safety of biologics and is advantageous in managing pediatric therapy.

Unanswered Questions: Vaccines and Antidrug Antibodies