User login

The interesting history of dermatologist-developed skin care

Those of you who have visited my dermatology practice in Miami know that the art in my office is dedicated to the history of the skin care industry. I collect , and I have written this historical column in honor of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News.

The first doctor to market his own cosmetic product, Erasmus Wilson, MD, faced scrutiny from his colleagues. Although he had contributed much to the field of dermatology, he was criticized by other dermatologists when he promoted a hair wash. The next doctor in my story, William Pusey, MD, was criticized for helping the company that manufactured Camay soap because he allowed his name to be used in Camay advertisements. The scrutiny that these two well-respected dermatologists endured from their colleagues deterred dermatologists from entering the skin care business for decades. The professional jealousy from dermatologic colleagues left the skin care field wide open for imposters, charlatans, and nondermatologists who had no concern for efficacy and patient outcomes to flourish. This is the story of a group of brilliant entrepreneurial dermatologists and one chiropractor who misrepresented himself as a dermatologist and how they influenced skin care as we know it.

Erasmus Wilson, MD1 (1809-1884): In 1840, Erasmus Wilson2 was a physician in London who chose to specialize in dermatology at a time when that specialization was frowned upon. He was a subeditor for The Lancet and wrote several books on dermatology including “Diseases of the Skin – A Practical and Theoretical Treatise,” “Portraits of the Diseases of the Skin,” and “Student’s Book on Diseases of the Skin.” He was the first professor of dermatology in the College of Surgeons and by 1869, was the leading English-speaking dermatologist in the world. He contributed much to dermatology, including his pioneering characterizations of Demodex mites, lichen planus, exfoliative dermatitis, neurotic excoriations, and roseola. Dr. Wilson was knighted in 1881 for his good works and notable generosity. (He was known for giving his poor patients money for food, endowing chairs in dermatology, and donating a famous obelisk in London).

In 1854, Dr. Wilson wrote a book for laypeople called “Healthy Skin: A Popular Treatise on the Skin and Hair, Their Preservation and Management,” in which he advocated cleanliness and bathing, which led to the popularity of Turkish baths and bathing resorts in Europe. Despite his undeniable contributions to dermatology, he was widely criticized by his colleagues for promoting a “Hair Wash” and a turtle oil soap. I cannot find any information about whether or not he developed the hair wash and turtle soap himself, but it seems that he earned income from sales of these two products, even though he was said to have donated it all to charities.

William A. Pusey MD (1865-1940): Dr. Pusey was the first chairman of dermatology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago. He published several books, including “Care of the Skin and Hair,” “Syphilis as a Modern Problem,” “The Principles and Practices of Dermatology,” and “History of Dermatology” among others. He is best known for his work in developing the use of x-rays (roentgen rays) and phototherapy in dermatology, and in 1907, he was the first dermatologist to describe the use of solid carbon dioxide to treat skin lesions. He was president of the American Dermatological Association in 1910, president of the Chicago Medical Society in 1918, editor of the Archives of Dermatology in 1920, and president of the American Medical Association in 1924.

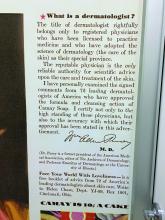

In the early 1920s, skin care companies were beginning to advertise their products using endorsements from celebrities and socialites, and were making misleading claims. Dr. Pusey wanted to work with these companies to help them perform evidence-based trials so they could make scientifically correct claims. Proctor & Gamble asked Dr. Pusey to advise them on how they could advertise honestly about their new soap, “Camay.” In Dr. Pusey’s words,3 “they (Proctor & Gamble) wanted to give the public authoritative advice about the use of soap and water. They suggested that I get a group of dermatologists of my selection to examine the soap and prepare instructions for bathing and the use of soap, and, if they found this soap was of high quality, to certify to that effect.” The research was performed as he suggested, and he allowed his name to be used in the Camay soap ads from 1926 to 1929. He said that he allowed them to use his name hoping to promote the need for evidence-based research, in contrast to the skin care products endorsed by socialites and celebrities that were flooding the market around that time.

Herbert Rattner, MD, at Northwestern University, Chicago, was his friend and one of the many dermatologists who criticized Dr. Pusey for allowing his name to be used in the Camay ads. Dr. Pusey’s reply to the criticism (according to Dr. Rattner) was that Proctor & Gamble was “proposing to do what the medical profession always is criticizing commercial concerns for not doing, namely, coming to physicians for information on medical matters. Could the profession hope to have any influence with business concerns if it was always eager to criticize bad commercial practices but never willing to support good ones?”3

While Dr. Pusey felt his reasons for adding his name to the Camay ads and research were justified, many of his friends stated that in hindsight, he regretted the action because of the negative response of his colleagues. It was years before dermatologists began providing input again into the skin care industry. During that time, radio, television and print ads were rampant with misleading claims – which led the way for a dermatologic imposter to make a fortune on skin care.

John Woodbury (1851-1909): John Woodbury, a chiropractor, never went to medical school, but that did not stop him from claiming he was a dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon. In 1889, he opened the John H. Woodbury Dermatological Institute in New York City, and over the next few years, opened Woodbury Dermatological Institutes in at least 5 states and employed 25 “physicians” who were not licensed to practice medicine. He came out with face soaps, tonics, and cold creams and spent a fortune on advertising these products and his institutes. In 1901, he sold his “Woodbury Soap” to the Andrew Jergens Company for $212,500 and 10% in royalties.

Multiple lawsuits occurred from 1898 to 1907 because he continued using the Woodbury name on his own products, despite having sold the “Woodbury” trademark to Jergens. He was sued for practicing medicine without a medical license and claiming to be a dermatologist when he was not. He lost most of these lawsuits, including one in 1907 in which the court ruled that corporations may not employ unlicensed professionals to practice medicine. In 1909, John Woodbury committed suicide. The Woodbury Soap company flourished in the 1930s and 1940s, as part of Jergens, until the brand was discontinued in 1970 when Jergens was acquired by American Brands.

The next dermatologists to come along did not make the same mistakes as those of their predecessors. They all made scientific discoveries through their basic science research in the laboratory, filed patents, formed skin care companies, perfected the formulations, and conducted research trials of the final product. Their marketing focused on science and efficacy and only rarely used their names and images in advertising, allowing them to maintain their reputations in the dermatology field.

Eugene Van Scott, MD (1922-present): Dermatologist Dr. Van Scott and dermatopharmacologist Ruey Yu, PhD, filed a method patent in the early 1970s on the effectiveness of alpha hydroxy acids to treat ichthyosis. They invented the abbreviation “AHA” and have continued their work on organic acids to this day. They now have more than 125 patents, which they have licensed to 60 companies in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries.

In 1988, 14 years after their initial publication, they founded the company they named Polystrata, which grew into today’s NeoStrata.4 Over the years, they had to defend their patents because many personal care companies used their technologies without licensing them. In 2007, they won a $41 million settlement in a patent infringement suit against Mary Kay filed in March 2005. They have both been very philanthropic in the dermatology world5 and are highly respected in the field. Among many other honors, Dr. Van Scott was named a Master Dermatologist by the American Academy of Dermatology in 1998 and received the Dermatology Foundation’s Distinguished Service Medallion in 2004.

Sheldon Pinnell, MD (1937-2013): After Dr. Pinnell completed his dermatology residency at Harvard Medical School, he spent 2 years studying collagen chemistry at the Max Planck Institute in Munich, Germany. In 1973, he returned to Duke University where he had earned his undergraduate degree before attending Yale University. He remained at Duke for the duration of his career and was professor and chief of dermatology there for many years. Early in his career, he focused on the role of vitamin C in collagen biosynthesis and discovered some of the mechanisms by which sun exposure causes photoaging. He described the use of the first (and most popular) topically applied L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) to prevent and treat skin aging.

Dr. Pinnell’s many discoveries include showing that the addition of ascorbic acid to fibroblast cultures increases collagen production and that topically applied L-ascorbic acid penetrates into the skin best at a pH of 2-2.5. Dr. Pinnell changed the way the world uses topical antioxidants today; he was widely respected and was a member of the American Dermatological Association and an honorary member of the Society of Investigative Dermatology. He published more than 200 scientific articles and held 10 patents. He started the skin care company Skinceuticals, based on his antioxidant technologies. It was acquired by L’Oreal in 2005.

Richard Fitzpatrick, MD (1944-2014): The dermatologist affectionately known as “Fitz” is credited with being the first to use lasers for skin resurfacing. He went to medical school at Emory University and did his dermatology residency at the University of California, Los Angeles. He authored more than 130 publications and was one of the first doctors to specialize in cosmetic dermatology. He realized that fibroblast cell cultures used to produce the collagen filler CosmoPlast (no longer on the market) generated many growth factors that could rejuvenate the skin, and in 1999, he launched the skin care brand SkinMedica. In 2000, he received a patent for fibroblast-derived growth factors used topically for antiaging – a formula he called Tissue Nutrient Solution. In 2001, the popular product TNS Recovery Complex was launched based on the patented growth factor technology. It is still the most popular growth factor technology on the market.

What can we learn from these pioneers? I have had several interesting discussions about this topic with Leonard Hoenig, MD, section editor for Reflections on Dermatology: Past, Present, and Future, in Clinics in Dermatology. (Dr. Hoenig told me the interesting story that Listerine mouthwash was named in honor of Joseph Lister but accounts vary as to whether he gave permission to do so. This makes Dr. Lister the most famous physician to endorse a personal care product.) When Dr. Hoenig and I discussed the ethics of dermatologists creating a skin care line or retailing skin care in their medical practice, he stated my sentiments perfectly: “We should rely on professional, ethical, and legal guidelines to help us do what is right. Most importantly, we should have the best interests of our patients at heart when recommending any treatments.”

Dermatologists have unique knowledge, experience, and perspective on treating the skin with topical agents and have the true desire to improve skin health. If we do not discover, research, patent, and develop efficacious skin care products, someone else will do it – and I do not think they will do it as well as a dermatologist can.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Everett MA. Int J Dermatol. 1978 May;17(4):345-52.

2. Moxon RK. N Engl J Med. 1976 Apr 1;294(14):762-4.

3. Rattner H. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1937;35(1):25-66.

4. Neostrata: More than Hope, by Elaine Strauss, U.S. 1 Newspaper, Feb. 24, 1999.

5. Two legends in the field of dermatology provide $1 million gift to Temple University school of medicine’s department of dermatology, Temple University, June 5, 2015.

Those of you who have visited my dermatology practice in Miami know that the art in my office is dedicated to the history of the skin care industry. I collect , and I have written this historical column in honor of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News.

The first doctor to market his own cosmetic product, Erasmus Wilson, MD, faced scrutiny from his colleagues. Although he had contributed much to the field of dermatology, he was criticized by other dermatologists when he promoted a hair wash. The next doctor in my story, William Pusey, MD, was criticized for helping the company that manufactured Camay soap because he allowed his name to be used in Camay advertisements. The scrutiny that these two well-respected dermatologists endured from their colleagues deterred dermatologists from entering the skin care business for decades. The professional jealousy from dermatologic colleagues left the skin care field wide open for imposters, charlatans, and nondermatologists who had no concern for efficacy and patient outcomes to flourish. This is the story of a group of brilliant entrepreneurial dermatologists and one chiropractor who misrepresented himself as a dermatologist and how they influenced skin care as we know it.

Erasmus Wilson, MD1 (1809-1884): In 1840, Erasmus Wilson2 was a physician in London who chose to specialize in dermatology at a time when that specialization was frowned upon. He was a subeditor for The Lancet and wrote several books on dermatology including “Diseases of the Skin – A Practical and Theoretical Treatise,” “Portraits of the Diseases of the Skin,” and “Student’s Book on Diseases of the Skin.” He was the first professor of dermatology in the College of Surgeons and by 1869, was the leading English-speaking dermatologist in the world. He contributed much to dermatology, including his pioneering characterizations of Demodex mites, lichen planus, exfoliative dermatitis, neurotic excoriations, and roseola. Dr. Wilson was knighted in 1881 for his good works and notable generosity. (He was known for giving his poor patients money for food, endowing chairs in dermatology, and donating a famous obelisk in London).

In 1854, Dr. Wilson wrote a book for laypeople called “Healthy Skin: A Popular Treatise on the Skin and Hair, Their Preservation and Management,” in which he advocated cleanliness and bathing, which led to the popularity of Turkish baths and bathing resorts in Europe. Despite his undeniable contributions to dermatology, he was widely criticized by his colleagues for promoting a “Hair Wash” and a turtle oil soap. I cannot find any information about whether or not he developed the hair wash and turtle soap himself, but it seems that he earned income from sales of these two products, even though he was said to have donated it all to charities.

William A. Pusey MD (1865-1940): Dr. Pusey was the first chairman of dermatology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago. He published several books, including “Care of the Skin and Hair,” “Syphilis as a Modern Problem,” “The Principles and Practices of Dermatology,” and “History of Dermatology” among others. He is best known for his work in developing the use of x-rays (roentgen rays) and phototherapy in dermatology, and in 1907, he was the first dermatologist to describe the use of solid carbon dioxide to treat skin lesions. He was president of the American Dermatological Association in 1910, president of the Chicago Medical Society in 1918, editor of the Archives of Dermatology in 1920, and president of the American Medical Association in 1924.

In the early 1920s, skin care companies were beginning to advertise their products using endorsements from celebrities and socialites, and were making misleading claims. Dr. Pusey wanted to work with these companies to help them perform evidence-based trials so they could make scientifically correct claims. Proctor & Gamble asked Dr. Pusey to advise them on how they could advertise honestly about their new soap, “Camay.” In Dr. Pusey’s words,3 “they (Proctor & Gamble) wanted to give the public authoritative advice about the use of soap and water. They suggested that I get a group of dermatologists of my selection to examine the soap and prepare instructions for bathing and the use of soap, and, if they found this soap was of high quality, to certify to that effect.” The research was performed as he suggested, and he allowed his name to be used in the Camay soap ads from 1926 to 1929. He said that he allowed them to use his name hoping to promote the need for evidence-based research, in contrast to the skin care products endorsed by socialites and celebrities that were flooding the market around that time.

Herbert Rattner, MD, at Northwestern University, Chicago, was his friend and one of the many dermatologists who criticized Dr. Pusey for allowing his name to be used in the Camay ads. Dr. Pusey’s reply to the criticism (according to Dr. Rattner) was that Proctor & Gamble was “proposing to do what the medical profession always is criticizing commercial concerns for not doing, namely, coming to physicians for information on medical matters. Could the profession hope to have any influence with business concerns if it was always eager to criticize bad commercial practices but never willing to support good ones?”3

While Dr. Pusey felt his reasons for adding his name to the Camay ads and research were justified, many of his friends stated that in hindsight, he regretted the action because of the negative response of his colleagues. It was years before dermatologists began providing input again into the skin care industry. During that time, radio, television and print ads were rampant with misleading claims – which led the way for a dermatologic imposter to make a fortune on skin care.

John Woodbury (1851-1909): John Woodbury, a chiropractor, never went to medical school, but that did not stop him from claiming he was a dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon. In 1889, he opened the John H. Woodbury Dermatological Institute in New York City, and over the next few years, opened Woodbury Dermatological Institutes in at least 5 states and employed 25 “physicians” who were not licensed to practice medicine. He came out with face soaps, tonics, and cold creams and spent a fortune on advertising these products and his institutes. In 1901, he sold his “Woodbury Soap” to the Andrew Jergens Company for $212,500 and 10% in royalties.

Multiple lawsuits occurred from 1898 to 1907 because he continued using the Woodbury name on his own products, despite having sold the “Woodbury” trademark to Jergens. He was sued for practicing medicine without a medical license and claiming to be a dermatologist when he was not. He lost most of these lawsuits, including one in 1907 in which the court ruled that corporations may not employ unlicensed professionals to practice medicine. In 1909, John Woodbury committed suicide. The Woodbury Soap company flourished in the 1930s and 1940s, as part of Jergens, until the brand was discontinued in 1970 when Jergens was acquired by American Brands.

The next dermatologists to come along did not make the same mistakes as those of their predecessors. They all made scientific discoveries through their basic science research in the laboratory, filed patents, formed skin care companies, perfected the formulations, and conducted research trials of the final product. Their marketing focused on science and efficacy and only rarely used their names and images in advertising, allowing them to maintain their reputations in the dermatology field.

Eugene Van Scott, MD (1922-present): Dermatologist Dr. Van Scott and dermatopharmacologist Ruey Yu, PhD, filed a method patent in the early 1970s on the effectiveness of alpha hydroxy acids to treat ichthyosis. They invented the abbreviation “AHA” and have continued their work on organic acids to this day. They now have more than 125 patents, which they have licensed to 60 companies in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries.

In 1988, 14 years after their initial publication, they founded the company they named Polystrata, which grew into today’s NeoStrata.4 Over the years, they had to defend their patents because many personal care companies used their technologies without licensing them. In 2007, they won a $41 million settlement in a patent infringement suit against Mary Kay filed in March 2005. They have both been very philanthropic in the dermatology world5 and are highly respected in the field. Among many other honors, Dr. Van Scott was named a Master Dermatologist by the American Academy of Dermatology in 1998 and received the Dermatology Foundation’s Distinguished Service Medallion in 2004.

Sheldon Pinnell, MD (1937-2013): After Dr. Pinnell completed his dermatology residency at Harvard Medical School, he spent 2 years studying collagen chemistry at the Max Planck Institute in Munich, Germany. In 1973, he returned to Duke University where he had earned his undergraduate degree before attending Yale University. He remained at Duke for the duration of his career and was professor and chief of dermatology there for many years. Early in his career, he focused on the role of vitamin C in collagen biosynthesis and discovered some of the mechanisms by which sun exposure causes photoaging. He described the use of the first (and most popular) topically applied L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) to prevent and treat skin aging.

Dr. Pinnell’s many discoveries include showing that the addition of ascorbic acid to fibroblast cultures increases collagen production and that topically applied L-ascorbic acid penetrates into the skin best at a pH of 2-2.5. Dr. Pinnell changed the way the world uses topical antioxidants today; he was widely respected and was a member of the American Dermatological Association and an honorary member of the Society of Investigative Dermatology. He published more than 200 scientific articles and held 10 patents. He started the skin care company Skinceuticals, based on his antioxidant technologies. It was acquired by L’Oreal in 2005.

Richard Fitzpatrick, MD (1944-2014): The dermatologist affectionately known as “Fitz” is credited with being the first to use lasers for skin resurfacing. He went to medical school at Emory University and did his dermatology residency at the University of California, Los Angeles. He authored more than 130 publications and was one of the first doctors to specialize in cosmetic dermatology. He realized that fibroblast cell cultures used to produce the collagen filler CosmoPlast (no longer on the market) generated many growth factors that could rejuvenate the skin, and in 1999, he launched the skin care brand SkinMedica. In 2000, he received a patent for fibroblast-derived growth factors used topically for antiaging – a formula he called Tissue Nutrient Solution. In 2001, the popular product TNS Recovery Complex was launched based on the patented growth factor technology. It is still the most popular growth factor technology on the market.

What can we learn from these pioneers? I have had several interesting discussions about this topic with Leonard Hoenig, MD, section editor for Reflections on Dermatology: Past, Present, and Future, in Clinics in Dermatology. (Dr. Hoenig told me the interesting story that Listerine mouthwash was named in honor of Joseph Lister but accounts vary as to whether he gave permission to do so. This makes Dr. Lister the most famous physician to endorse a personal care product.) When Dr. Hoenig and I discussed the ethics of dermatologists creating a skin care line or retailing skin care in their medical practice, he stated my sentiments perfectly: “We should rely on professional, ethical, and legal guidelines to help us do what is right. Most importantly, we should have the best interests of our patients at heart when recommending any treatments.”

Dermatologists have unique knowledge, experience, and perspective on treating the skin with topical agents and have the true desire to improve skin health. If we do not discover, research, patent, and develop efficacious skin care products, someone else will do it – and I do not think they will do it as well as a dermatologist can.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Everett MA. Int J Dermatol. 1978 May;17(4):345-52.

2. Moxon RK. N Engl J Med. 1976 Apr 1;294(14):762-4.

3. Rattner H. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1937;35(1):25-66.

4. Neostrata: More than Hope, by Elaine Strauss, U.S. 1 Newspaper, Feb. 24, 1999.

5. Two legends in the field of dermatology provide $1 million gift to Temple University school of medicine’s department of dermatology, Temple University, June 5, 2015.

Those of you who have visited my dermatology practice in Miami know that the art in my office is dedicated to the history of the skin care industry. I collect , and I have written this historical column in honor of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News.

The first doctor to market his own cosmetic product, Erasmus Wilson, MD, faced scrutiny from his colleagues. Although he had contributed much to the field of dermatology, he was criticized by other dermatologists when he promoted a hair wash. The next doctor in my story, William Pusey, MD, was criticized for helping the company that manufactured Camay soap because he allowed his name to be used in Camay advertisements. The scrutiny that these two well-respected dermatologists endured from their colleagues deterred dermatologists from entering the skin care business for decades. The professional jealousy from dermatologic colleagues left the skin care field wide open for imposters, charlatans, and nondermatologists who had no concern for efficacy and patient outcomes to flourish. This is the story of a group of brilliant entrepreneurial dermatologists and one chiropractor who misrepresented himself as a dermatologist and how they influenced skin care as we know it.

Erasmus Wilson, MD1 (1809-1884): In 1840, Erasmus Wilson2 was a physician in London who chose to specialize in dermatology at a time when that specialization was frowned upon. He was a subeditor for The Lancet and wrote several books on dermatology including “Diseases of the Skin – A Practical and Theoretical Treatise,” “Portraits of the Diseases of the Skin,” and “Student’s Book on Diseases of the Skin.” He was the first professor of dermatology in the College of Surgeons and by 1869, was the leading English-speaking dermatologist in the world. He contributed much to dermatology, including his pioneering characterizations of Demodex mites, lichen planus, exfoliative dermatitis, neurotic excoriations, and roseola. Dr. Wilson was knighted in 1881 for his good works and notable generosity. (He was known for giving his poor patients money for food, endowing chairs in dermatology, and donating a famous obelisk in London).

In 1854, Dr. Wilson wrote a book for laypeople called “Healthy Skin: A Popular Treatise on the Skin and Hair, Their Preservation and Management,” in which he advocated cleanliness and bathing, which led to the popularity of Turkish baths and bathing resorts in Europe. Despite his undeniable contributions to dermatology, he was widely criticized by his colleagues for promoting a “Hair Wash” and a turtle oil soap. I cannot find any information about whether or not he developed the hair wash and turtle soap himself, but it seems that he earned income from sales of these two products, even though he was said to have donated it all to charities.

William A. Pusey MD (1865-1940): Dr. Pusey was the first chairman of dermatology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago. He published several books, including “Care of the Skin and Hair,” “Syphilis as a Modern Problem,” “The Principles and Practices of Dermatology,” and “History of Dermatology” among others. He is best known for his work in developing the use of x-rays (roentgen rays) and phototherapy in dermatology, and in 1907, he was the first dermatologist to describe the use of solid carbon dioxide to treat skin lesions. He was president of the American Dermatological Association in 1910, president of the Chicago Medical Society in 1918, editor of the Archives of Dermatology in 1920, and president of the American Medical Association in 1924.

In the early 1920s, skin care companies were beginning to advertise their products using endorsements from celebrities and socialites, and were making misleading claims. Dr. Pusey wanted to work with these companies to help them perform evidence-based trials so they could make scientifically correct claims. Proctor & Gamble asked Dr. Pusey to advise them on how they could advertise honestly about their new soap, “Camay.” In Dr. Pusey’s words,3 “they (Proctor & Gamble) wanted to give the public authoritative advice about the use of soap and water. They suggested that I get a group of dermatologists of my selection to examine the soap and prepare instructions for bathing and the use of soap, and, if they found this soap was of high quality, to certify to that effect.” The research was performed as he suggested, and he allowed his name to be used in the Camay soap ads from 1926 to 1929. He said that he allowed them to use his name hoping to promote the need for evidence-based research, in contrast to the skin care products endorsed by socialites and celebrities that were flooding the market around that time.

Herbert Rattner, MD, at Northwestern University, Chicago, was his friend and one of the many dermatologists who criticized Dr. Pusey for allowing his name to be used in the Camay ads. Dr. Pusey’s reply to the criticism (according to Dr. Rattner) was that Proctor & Gamble was “proposing to do what the medical profession always is criticizing commercial concerns for not doing, namely, coming to physicians for information on medical matters. Could the profession hope to have any influence with business concerns if it was always eager to criticize bad commercial practices but never willing to support good ones?”3

While Dr. Pusey felt his reasons for adding his name to the Camay ads and research were justified, many of his friends stated that in hindsight, he regretted the action because of the negative response of his colleagues. It was years before dermatologists began providing input again into the skin care industry. During that time, radio, television and print ads were rampant with misleading claims – which led the way for a dermatologic imposter to make a fortune on skin care.

John Woodbury (1851-1909): John Woodbury, a chiropractor, never went to medical school, but that did not stop him from claiming he was a dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon. In 1889, he opened the John H. Woodbury Dermatological Institute in New York City, and over the next few years, opened Woodbury Dermatological Institutes in at least 5 states and employed 25 “physicians” who were not licensed to practice medicine. He came out with face soaps, tonics, and cold creams and spent a fortune on advertising these products and his institutes. In 1901, he sold his “Woodbury Soap” to the Andrew Jergens Company for $212,500 and 10% in royalties.

Multiple lawsuits occurred from 1898 to 1907 because he continued using the Woodbury name on his own products, despite having sold the “Woodbury” trademark to Jergens. He was sued for practicing medicine without a medical license and claiming to be a dermatologist when he was not. He lost most of these lawsuits, including one in 1907 in which the court ruled that corporations may not employ unlicensed professionals to practice medicine. In 1909, John Woodbury committed suicide. The Woodbury Soap company flourished in the 1930s and 1940s, as part of Jergens, until the brand was discontinued in 1970 when Jergens was acquired by American Brands.

The next dermatologists to come along did not make the same mistakes as those of their predecessors. They all made scientific discoveries through their basic science research in the laboratory, filed patents, formed skin care companies, perfected the formulations, and conducted research trials of the final product. Their marketing focused on science and efficacy and only rarely used their names and images in advertising, allowing them to maintain their reputations in the dermatology field.

Eugene Van Scott, MD (1922-present): Dermatologist Dr. Van Scott and dermatopharmacologist Ruey Yu, PhD, filed a method patent in the early 1970s on the effectiveness of alpha hydroxy acids to treat ichthyosis. They invented the abbreviation “AHA” and have continued their work on organic acids to this day. They now have more than 125 patents, which they have licensed to 60 companies in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries.

In 1988, 14 years after their initial publication, they founded the company they named Polystrata, which grew into today’s NeoStrata.4 Over the years, they had to defend their patents because many personal care companies used their technologies without licensing them. In 2007, they won a $41 million settlement in a patent infringement suit against Mary Kay filed in March 2005. They have both been very philanthropic in the dermatology world5 and are highly respected in the field. Among many other honors, Dr. Van Scott was named a Master Dermatologist by the American Academy of Dermatology in 1998 and received the Dermatology Foundation’s Distinguished Service Medallion in 2004.

Sheldon Pinnell, MD (1937-2013): After Dr. Pinnell completed his dermatology residency at Harvard Medical School, he spent 2 years studying collagen chemistry at the Max Planck Institute in Munich, Germany. In 1973, he returned to Duke University where he had earned his undergraduate degree before attending Yale University. He remained at Duke for the duration of his career and was professor and chief of dermatology there for many years. Early in his career, he focused on the role of vitamin C in collagen biosynthesis and discovered some of the mechanisms by which sun exposure causes photoaging. He described the use of the first (and most popular) topically applied L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) to prevent and treat skin aging.

Dr. Pinnell’s many discoveries include showing that the addition of ascorbic acid to fibroblast cultures increases collagen production and that topically applied L-ascorbic acid penetrates into the skin best at a pH of 2-2.5. Dr. Pinnell changed the way the world uses topical antioxidants today; he was widely respected and was a member of the American Dermatological Association and an honorary member of the Society of Investigative Dermatology. He published more than 200 scientific articles and held 10 patents. He started the skin care company Skinceuticals, based on his antioxidant technologies. It was acquired by L’Oreal in 2005.

Richard Fitzpatrick, MD (1944-2014): The dermatologist affectionately known as “Fitz” is credited with being the first to use lasers for skin resurfacing. He went to medical school at Emory University and did his dermatology residency at the University of California, Los Angeles. He authored more than 130 publications and was one of the first doctors to specialize in cosmetic dermatology. He realized that fibroblast cell cultures used to produce the collagen filler CosmoPlast (no longer on the market) generated many growth factors that could rejuvenate the skin, and in 1999, he launched the skin care brand SkinMedica. In 2000, he received a patent for fibroblast-derived growth factors used topically for antiaging – a formula he called Tissue Nutrient Solution. In 2001, the popular product TNS Recovery Complex was launched based on the patented growth factor technology. It is still the most popular growth factor technology on the market.

What can we learn from these pioneers? I have had several interesting discussions about this topic with Leonard Hoenig, MD, section editor for Reflections on Dermatology: Past, Present, and Future, in Clinics in Dermatology. (Dr. Hoenig told me the interesting story that Listerine mouthwash was named in honor of Joseph Lister but accounts vary as to whether he gave permission to do so. This makes Dr. Lister the most famous physician to endorse a personal care product.) When Dr. Hoenig and I discussed the ethics of dermatologists creating a skin care line or retailing skin care in their medical practice, he stated my sentiments perfectly: “We should rely on professional, ethical, and legal guidelines to help us do what is right. Most importantly, we should have the best interests of our patients at heart when recommending any treatments.”

Dermatologists have unique knowledge, experience, and perspective on treating the skin with topical agents and have the true desire to improve skin health. If we do not discover, research, patent, and develop efficacious skin care products, someone else will do it – and I do not think they will do it as well as a dermatologist can.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Everett MA. Int J Dermatol. 1978 May;17(4):345-52.

2. Moxon RK. N Engl J Med. 1976 Apr 1;294(14):762-4.

3. Rattner H. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1937;35(1):25-66.

4. Neostrata: More than Hope, by Elaine Strauss, U.S. 1 Newspaper, Feb. 24, 1999.

5. Two legends in the field of dermatology provide $1 million gift to Temple University school of medicine’s department of dermatology, Temple University, June 5, 2015.

Convalescent plasma actions spark trial recruitment concerns

The agency’s move took many investigators by surprise. The EUA was announced at the White House the day after President Donald J. Trump accused the FDA of delaying approval of therapeutics to hurt his re-election chances.

In a memo describing the decision, the FDA cited data from some controlled and uncontrolled studies and, primarily, data from an open-label expanded-access protocol overseen by the Mayo Clinic.

At the White House, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said that plasma had been found to save the lives of 35 out of every 100 who were treated. That figure was later found to have been erroneous, and many experts pointed out that Hahn had conflated an absolute risk reduction with a relative reduction. After a firestorm of criticism, Hahn issued an apology.

“The criticism is entirely justified,” he tweeted. “What I should have said better is that the data show a relative risk reduction not an absolute risk reduction.”

About 15 randomized controlled trials – out of 54 total studies involving convalescent plasma – are underway in the United States, according to ClinicalTrials.gov. The FDA’s Aug. 23 emergency authorization gave clinicians wide leeway to employ convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

The agency noted, however, that “adequate and well-controlled randomized trials remain necessary for a definitive demonstration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma efficacy and to determine the optimal product attributes and appropriate patient populations for its use.”

But it’s not clear that people with COVID-19, especially those who are severely ill and hospitalized, will choose to enlist in a clinical trial – where they could receive a placebo – when they instead could get plasma.

“I’ve been asked repeatedly whether the EUA will affect our ability to recruit people into our hospitalized patient trial,” said Liise-anne Pirofski, MD, FIDSA, chief of the department of medicine, infectious diseases division at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. “I do not know,” she said, on a call with reporters organized by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“But,” she said, “I do know that the trial will continue and that we will discuss the evidence that we have with our patients and give them all that we can to help them weigh the evidence and make up their minds.”

Pirofski said the study being conducted at Montefiore and four other sites has since late April enrolled 190 patients out of a hoped-for 300.

When the study – which compares convalescent plasma to saline in hospitalized patients – was first designed, “there was not any funding for our trial and honestly not a whole lot of interest,” Pirofski told reporters. Individual donors helped support the initial rollout in late April and the trial quickly enrolled 150 patients as the pandemic peaked in the New York City area.

The National Institutes of Health has since given funding, which allowed the study to expand to New York University, Yale University, the University of Miami, and the University of Texas at Houston.

Hopeful, but a long way to go

Shmuel Shoham, MD, FIDSA, associate director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, said that he’s hopeful that people will continue to enroll in his trial, which is seeking to determine if plasma can prevent COVID-19 in those who’ve been recently exposed.

“Volunteers joining the study is the only way that we’re going to get to know whether this stuff works for prevention and treatment,” Shoham said on the call. He urged physicians and other healthcare workers to talk with patients about considering trial participation.

Shoham’s study is being conducted at 30 US sites and one at the Navajo Nation. It has enrolled 25 out of a hoped-for 500 participants. “We have a long way to go,” said Shoham.

Another Hopkins study to determine whether plasma is helpful in shortening illness in nonhospitalized patients, which is being conducted at the same 31 sites, has enrolled 50 out of 600.

Shoham said recruiting patients with COVID for any study had proven to be difficult. “The vast majority of people that have coronavirus do not come to centers that do clinical trials or interventional trials,” he said, adding that, in addition, most of those “who have coronavirus don’t want to be in a trial. They just want to have coronavirus and get it over with.”

But it’s important to understand how to conduct trials in a pandemic – in part to get answers quickly, he said. Researchers have been looking at convalescent plasma for months, said Shoham. “Why don’t we have the randomized clinical trial data that we want?”

Pirofski noted that trials have also been hobbled in part by “the shifting areas of the pandemic.” Fewer cases make for fewer potential plasma donors.

Both Shoham and Pirofski also said that more needed to be done to encourage plasma donors to participate.

The US Department of Health & Human Services clarified in August that hospitals, physicians, health plans, and other health care workers could contact individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 without violating the HIPAA privacy rule.

Pirofski said she believes that trial investigators know it is legal to reach out to patients. But, she said, “it probably could be better known.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency’s move took many investigators by surprise. The EUA was announced at the White House the day after President Donald J. Trump accused the FDA of delaying approval of therapeutics to hurt his re-election chances.

In a memo describing the decision, the FDA cited data from some controlled and uncontrolled studies and, primarily, data from an open-label expanded-access protocol overseen by the Mayo Clinic.

At the White House, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said that plasma had been found to save the lives of 35 out of every 100 who were treated. That figure was later found to have been erroneous, and many experts pointed out that Hahn had conflated an absolute risk reduction with a relative reduction. After a firestorm of criticism, Hahn issued an apology.

“The criticism is entirely justified,” he tweeted. “What I should have said better is that the data show a relative risk reduction not an absolute risk reduction.”

About 15 randomized controlled trials – out of 54 total studies involving convalescent plasma – are underway in the United States, according to ClinicalTrials.gov. The FDA’s Aug. 23 emergency authorization gave clinicians wide leeway to employ convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

The agency noted, however, that “adequate and well-controlled randomized trials remain necessary for a definitive demonstration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma efficacy and to determine the optimal product attributes and appropriate patient populations for its use.”

But it’s not clear that people with COVID-19, especially those who are severely ill and hospitalized, will choose to enlist in a clinical trial – where they could receive a placebo – when they instead could get plasma.

“I’ve been asked repeatedly whether the EUA will affect our ability to recruit people into our hospitalized patient trial,” said Liise-anne Pirofski, MD, FIDSA, chief of the department of medicine, infectious diseases division at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. “I do not know,” she said, on a call with reporters organized by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“But,” she said, “I do know that the trial will continue and that we will discuss the evidence that we have with our patients and give them all that we can to help them weigh the evidence and make up their minds.”

Pirofski said the study being conducted at Montefiore and four other sites has since late April enrolled 190 patients out of a hoped-for 300.

When the study – which compares convalescent plasma to saline in hospitalized patients – was first designed, “there was not any funding for our trial and honestly not a whole lot of interest,” Pirofski told reporters. Individual donors helped support the initial rollout in late April and the trial quickly enrolled 150 patients as the pandemic peaked in the New York City area.

The National Institutes of Health has since given funding, which allowed the study to expand to New York University, Yale University, the University of Miami, and the University of Texas at Houston.

Hopeful, but a long way to go

Shmuel Shoham, MD, FIDSA, associate director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, said that he’s hopeful that people will continue to enroll in his trial, which is seeking to determine if plasma can prevent COVID-19 in those who’ve been recently exposed.

“Volunteers joining the study is the only way that we’re going to get to know whether this stuff works for prevention and treatment,” Shoham said on the call. He urged physicians and other healthcare workers to talk with patients about considering trial participation.

Shoham’s study is being conducted at 30 US sites and one at the Navajo Nation. It has enrolled 25 out of a hoped-for 500 participants. “We have a long way to go,” said Shoham.

Another Hopkins study to determine whether plasma is helpful in shortening illness in nonhospitalized patients, which is being conducted at the same 31 sites, has enrolled 50 out of 600.

Shoham said recruiting patients with COVID for any study had proven to be difficult. “The vast majority of people that have coronavirus do not come to centers that do clinical trials or interventional trials,” he said, adding that, in addition, most of those “who have coronavirus don’t want to be in a trial. They just want to have coronavirus and get it over with.”

But it’s important to understand how to conduct trials in a pandemic – in part to get answers quickly, he said. Researchers have been looking at convalescent plasma for months, said Shoham. “Why don’t we have the randomized clinical trial data that we want?”

Pirofski noted that trials have also been hobbled in part by “the shifting areas of the pandemic.” Fewer cases make for fewer potential plasma donors.

Both Shoham and Pirofski also said that more needed to be done to encourage plasma donors to participate.

The US Department of Health & Human Services clarified in August that hospitals, physicians, health plans, and other health care workers could contact individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 without violating the HIPAA privacy rule.

Pirofski said she believes that trial investigators know it is legal to reach out to patients. But, she said, “it probably could be better known.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency’s move took many investigators by surprise. The EUA was announced at the White House the day after President Donald J. Trump accused the FDA of delaying approval of therapeutics to hurt his re-election chances.

In a memo describing the decision, the FDA cited data from some controlled and uncontrolled studies and, primarily, data from an open-label expanded-access protocol overseen by the Mayo Clinic.

At the White House, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said that plasma had been found to save the lives of 35 out of every 100 who were treated. That figure was later found to have been erroneous, and many experts pointed out that Hahn had conflated an absolute risk reduction with a relative reduction. After a firestorm of criticism, Hahn issued an apology.

“The criticism is entirely justified,” he tweeted. “What I should have said better is that the data show a relative risk reduction not an absolute risk reduction.”

About 15 randomized controlled trials – out of 54 total studies involving convalescent plasma – are underway in the United States, according to ClinicalTrials.gov. The FDA’s Aug. 23 emergency authorization gave clinicians wide leeway to employ convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

The agency noted, however, that “adequate and well-controlled randomized trials remain necessary for a definitive demonstration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma efficacy and to determine the optimal product attributes and appropriate patient populations for its use.”

But it’s not clear that people with COVID-19, especially those who are severely ill and hospitalized, will choose to enlist in a clinical trial – where they could receive a placebo – when they instead could get plasma.

“I’ve been asked repeatedly whether the EUA will affect our ability to recruit people into our hospitalized patient trial,” said Liise-anne Pirofski, MD, FIDSA, chief of the department of medicine, infectious diseases division at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. “I do not know,” she said, on a call with reporters organized by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“But,” she said, “I do know that the trial will continue and that we will discuss the evidence that we have with our patients and give them all that we can to help them weigh the evidence and make up their minds.”

Pirofski said the study being conducted at Montefiore and four other sites has since late April enrolled 190 patients out of a hoped-for 300.

When the study – which compares convalescent plasma to saline in hospitalized patients – was first designed, “there was not any funding for our trial and honestly not a whole lot of interest,” Pirofski told reporters. Individual donors helped support the initial rollout in late April and the trial quickly enrolled 150 patients as the pandemic peaked in the New York City area.

The National Institutes of Health has since given funding, which allowed the study to expand to New York University, Yale University, the University of Miami, and the University of Texas at Houston.

Hopeful, but a long way to go

Shmuel Shoham, MD, FIDSA, associate director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, said that he’s hopeful that people will continue to enroll in his trial, which is seeking to determine if plasma can prevent COVID-19 in those who’ve been recently exposed.

“Volunteers joining the study is the only way that we’re going to get to know whether this stuff works for prevention and treatment,” Shoham said on the call. He urged physicians and other healthcare workers to talk with patients about considering trial participation.

Shoham’s study is being conducted at 30 US sites and one at the Navajo Nation. It has enrolled 25 out of a hoped-for 500 participants. “We have a long way to go,” said Shoham.

Another Hopkins study to determine whether plasma is helpful in shortening illness in nonhospitalized patients, which is being conducted at the same 31 sites, has enrolled 50 out of 600.

Shoham said recruiting patients with COVID for any study had proven to be difficult. “The vast majority of people that have coronavirus do not come to centers that do clinical trials or interventional trials,” he said, adding that, in addition, most of those “who have coronavirus don’t want to be in a trial. They just want to have coronavirus and get it over with.”

But it’s important to understand how to conduct trials in a pandemic – in part to get answers quickly, he said. Researchers have been looking at convalescent plasma for months, said Shoham. “Why don’t we have the randomized clinical trial data that we want?”

Pirofski noted that trials have also been hobbled in part by “the shifting areas of the pandemic.” Fewer cases make for fewer potential plasma donors.

Both Shoham and Pirofski also said that more needed to be done to encourage plasma donors to participate.

The US Department of Health & Human Services clarified in August that hospitals, physicians, health plans, and other health care workers could contact individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 without violating the HIPAA privacy rule.

Pirofski said she believes that trial investigators know it is legal to reach out to patients. But, she said, “it probably could be better known.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nine antihypertensive drugs associated with reduced risk of depression

The risk of depression is elevated in patients with cardiovascular diseases, but several specific antihypertensive therapies are associated with a reduced risk, and none appear to increase the risk, according to a population-based study that evaluated 10 years of data in nearly 4 million subjects.

“As the first study on individual antihypertensives and risk of depression, we found a decreased risk of depression with nine drugs,” reported a collaborative group of investigators from multiple institutions in Denmark where the study was undertaken.

In a study period spanning from 2005 to 2015, risk of a diagnosis of depression was evaluated in patients taking any of 41 antihypertensive therapies in four major categories. These were identified as angiotensin agents (ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers), calcium antagonists, beta-blockers, and diuretics.

Within these groups, agents associated with a reduced risk of depression were: two angiotensin agents, enalapril and ramipril; three calcium antagonists, amlodipine, verapamil, and verapamil combinations; and four beta-blockers, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, and carvedilol. The remaining drugs in these classes and diuretics were not associated with a reduced risk of depression. However, no antihypertensive agent was linked to an increased risk of depression.

All people living in Denmark are assigned a unique personal identification number that permits health information to be tracked across multiple registers. In this study, information was linked for several registries, including the Danish Medical Register on Vital Statistics, the Medicinal Product Statistics, and the Danish Psychiatric Central Register.

Data from a total of 3.75 million patients exposed to antihypertensive therapy during the study period were evaluated. Roughly 1 million of them were exposed to angiotensin drugs and slightly more than a million were exposed to diuretics. For calcium antagonists or beta-blockers, the numbers were approximately 835,000 and 775,000, respectively.

After adjustment for such factors as concomitant somatic diagnoses, sex, age, and employment status, the hazard ratios for depression among drugs associated with protection identified a risk reduction of 10%-25% in most cases when those who had been given 6-10 prescriptions or more than 10 prescriptions were compared with those who received 2 or fewer.

At the level of 10 or more prescriptions, for example, the risk reductions were 17% for ramipril (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.78-0.89), 8% for enalapril (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88-0.96), 18% for amlodipine (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.79-0.86), 15% for verapamil (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.83), 28% for propranolol (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.67-0.77), 20% for atenolol (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74-0.86), 25% for bisoprolol (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.67-0.84), and 16% for carvedilol (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75-0.95).

For verapamil combinations, the risk reduction was 67% (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.17-0.63), but the investigators cautioned that only 130 individuals were exposed to verapamil combinations, limiting the reliability of this analysis.

Interpreting the findings

A study hypothesis, the observed protective effect against depression, was expected for angiotensin drugs and calcium-channel blockers, but not for beta-blockers, according to the investigators.

“The renin-angiotensin systems is one of the pathways known to modulate inflammation in the central nervous system and seems involved in the regulation of the stress response. Angiotensin agents may also exert anti-inflammatory effects,” the investigators explained. “Dysregulation of intracellular calcium is evident in depression, including receptor-regulated calcium signaling.”

In contrast, beta-blockers have been associated with increased risk of depression in some but not all studies, according to the investigators. They maintained that some clinicians avoid these agents in patients with a history of mood disorders.

In attempting to account for the variability within drug classes regarding protection and lack of protection against depression, the investigators speculated that differences in pharmacologic properties, such as relative lipophilicity or anti-inflammatory effect, might be important.

Despite the large amount of data, William B. White, MD, professor emeritus at the Calhoun Cardiology Center, University of Connecticut, Farmington, is not convinced.

“In observational studies, even those with very large samples sizes, bias and confounding are hard to extricate with controls and propensity-score matching,” Dr. White said. From his perspective, the protective effects of some but not all drugs within a class “give one the impression that the findings are likely random.”

A member of the editorial board of the journal in which this study appeared, Dr. White said he was not involved in the review of the manuscript. Ultimately, he believed that the results are difficult to interpret.

“For example, there is no plausible rationale for why 2 of the 16 ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers or 4 of the 15 beta-blockers or 3 of the 10 calcium-channel blockers would reduce depression while the others in the class would have no effect,” he said.

Despite the investigators’ conclusion that these data should drive drug choice for patients at risk of depression, “I would say the results of this analysis would not lead me to alter clinical practice,” Dr. White added.

According to the principal investigator of the study, Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DSc, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen, many variables affect choice of antihypertensive drug. However, the depression risk is elevated in patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease and hypertension.

When risk of a mood disorder is a concern, use of one of the nine drugs associated with protection from depression should be considered, “especially in patients at increased risk of developing depression, including patients with prior depression or anxiety and patients with a family history of depression,” he and his coinvestigators concluded.

However, Dr. Kessing said in an interview that the data do not help with individual treatment choices. “We do not compare different antihypertensives against each other due to the risk of confounding by indications, so, no, it is not reasonable to consider relative risk among specific agents.”

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest involving this topic.

SOURCE: Kessing LV et al. Hypertension. 2020 Aug 24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15605.

The risk of depression is elevated in patients with cardiovascular diseases, but several specific antihypertensive therapies are associated with a reduced risk, and none appear to increase the risk, according to a population-based study that evaluated 10 years of data in nearly 4 million subjects.

“As the first study on individual antihypertensives and risk of depression, we found a decreased risk of depression with nine drugs,” reported a collaborative group of investigators from multiple institutions in Denmark where the study was undertaken.

In a study period spanning from 2005 to 2015, risk of a diagnosis of depression was evaluated in patients taking any of 41 antihypertensive therapies in four major categories. These were identified as angiotensin agents (ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers), calcium antagonists, beta-blockers, and diuretics.

Within these groups, agents associated with a reduced risk of depression were: two angiotensin agents, enalapril and ramipril; three calcium antagonists, amlodipine, verapamil, and verapamil combinations; and four beta-blockers, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, and carvedilol. The remaining drugs in these classes and diuretics were not associated with a reduced risk of depression. However, no antihypertensive agent was linked to an increased risk of depression.

All people living in Denmark are assigned a unique personal identification number that permits health information to be tracked across multiple registers. In this study, information was linked for several registries, including the Danish Medical Register on Vital Statistics, the Medicinal Product Statistics, and the Danish Psychiatric Central Register.

Data from a total of 3.75 million patients exposed to antihypertensive therapy during the study period were evaluated. Roughly 1 million of them were exposed to angiotensin drugs and slightly more than a million were exposed to diuretics. For calcium antagonists or beta-blockers, the numbers were approximately 835,000 and 775,000, respectively.

After adjustment for such factors as concomitant somatic diagnoses, sex, age, and employment status, the hazard ratios for depression among drugs associated with protection identified a risk reduction of 10%-25% in most cases when those who had been given 6-10 prescriptions or more than 10 prescriptions were compared with those who received 2 or fewer.

At the level of 10 or more prescriptions, for example, the risk reductions were 17% for ramipril (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.78-0.89), 8% for enalapril (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88-0.96), 18% for amlodipine (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.79-0.86), 15% for verapamil (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.83), 28% for propranolol (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.67-0.77), 20% for atenolol (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74-0.86), 25% for bisoprolol (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.67-0.84), and 16% for carvedilol (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75-0.95).

For verapamil combinations, the risk reduction was 67% (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.17-0.63), but the investigators cautioned that only 130 individuals were exposed to verapamil combinations, limiting the reliability of this analysis.

Interpreting the findings

A study hypothesis, the observed protective effect against depression, was expected for angiotensin drugs and calcium-channel blockers, but not for beta-blockers, according to the investigators.

“The renin-angiotensin systems is one of the pathways known to modulate inflammation in the central nervous system and seems involved in the regulation of the stress response. Angiotensin agents may also exert anti-inflammatory effects,” the investigators explained. “Dysregulation of intracellular calcium is evident in depression, including receptor-regulated calcium signaling.”

In contrast, beta-blockers have been associated with increased risk of depression in some but not all studies, according to the investigators. They maintained that some clinicians avoid these agents in patients with a history of mood disorders.

In attempting to account for the variability within drug classes regarding protection and lack of protection against depression, the investigators speculated that differences in pharmacologic properties, such as relative lipophilicity or anti-inflammatory effect, might be important.

Despite the large amount of data, William B. White, MD, professor emeritus at the Calhoun Cardiology Center, University of Connecticut, Farmington, is not convinced.

“In observational studies, even those with very large samples sizes, bias and confounding are hard to extricate with controls and propensity-score matching,” Dr. White said. From his perspective, the protective effects of some but not all drugs within a class “give one the impression that the findings are likely random.”

A member of the editorial board of the journal in which this study appeared, Dr. White said he was not involved in the review of the manuscript. Ultimately, he believed that the results are difficult to interpret.

“For example, there is no plausible rationale for why 2 of the 16 ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers or 4 of the 15 beta-blockers or 3 of the 10 calcium-channel blockers would reduce depression while the others in the class would have no effect,” he said.

Despite the investigators’ conclusion that these data should drive drug choice for patients at risk of depression, “I would say the results of this analysis would not lead me to alter clinical practice,” Dr. White added.

According to the principal investigator of the study, Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DSc, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen, many variables affect choice of antihypertensive drug. However, the depression risk is elevated in patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease and hypertension.

When risk of a mood disorder is a concern, use of one of the nine drugs associated with protection from depression should be considered, “especially in patients at increased risk of developing depression, including patients with prior depression or anxiety and patients with a family history of depression,” he and his coinvestigators concluded.

However, Dr. Kessing said in an interview that the data do not help with individual treatment choices. “We do not compare different antihypertensives against each other due to the risk of confounding by indications, so, no, it is not reasonable to consider relative risk among specific agents.”

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest involving this topic.

SOURCE: Kessing LV et al. Hypertension. 2020 Aug 24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15605.

The risk of depression is elevated in patients with cardiovascular diseases, but several specific antihypertensive therapies are associated with a reduced risk, and none appear to increase the risk, according to a population-based study that evaluated 10 years of data in nearly 4 million subjects.

“As the first study on individual antihypertensives and risk of depression, we found a decreased risk of depression with nine drugs,” reported a collaborative group of investigators from multiple institutions in Denmark where the study was undertaken.

In a study period spanning from 2005 to 2015, risk of a diagnosis of depression was evaluated in patients taking any of 41 antihypertensive therapies in four major categories. These were identified as angiotensin agents (ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers), calcium antagonists, beta-blockers, and diuretics.

Within these groups, agents associated with a reduced risk of depression were: two angiotensin agents, enalapril and ramipril; three calcium antagonists, amlodipine, verapamil, and verapamil combinations; and four beta-blockers, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, and carvedilol. The remaining drugs in these classes and diuretics were not associated with a reduced risk of depression. However, no antihypertensive agent was linked to an increased risk of depression.

All people living in Denmark are assigned a unique personal identification number that permits health information to be tracked across multiple registers. In this study, information was linked for several registries, including the Danish Medical Register on Vital Statistics, the Medicinal Product Statistics, and the Danish Psychiatric Central Register.

Data from a total of 3.75 million patients exposed to antihypertensive therapy during the study period were evaluated. Roughly 1 million of them were exposed to angiotensin drugs and slightly more than a million were exposed to diuretics. For calcium antagonists or beta-blockers, the numbers were approximately 835,000 and 775,000, respectively.

After adjustment for such factors as concomitant somatic diagnoses, sex, age, and employment status, the hazard ratios for depression among drugs associated with protection identified a risk reduction of 10%-25% in most cases when those who had been given 6-10 prescriptions or more than 10 prescriptions were compared with those who received 2 or fewer.

At the level of 10 or more prescriptions, for example, the risk reductions were 17% for ramipril (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.78-0.89), 8% for enalapril (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88-0.96), 18% for amlodipine (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.79-0.86), 15% for verapamil (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.83), 28% for propranolol (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.67-0.77), 20% for atenolol (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74-0.86), 25% for bisoprolol (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.67-0.84), and 16% for carvedilol (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75-0.95).

For verapamil combinations, the risk reduction was 67% (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.17-0.63), but the investigators cautioned that only 130 individuals were exposed to verapamil combinations, limiting the reliability of this analysis.

Interpreting the findings

A study hypothesis, the observed protective effect against depression, was expected for angiotensin drugs and calcium-channel blockers, but not for beta-blockers, according to the investigators.

“The renin-angiotensin systems is one of the pathways known to modulate inflammation in the central nervous system and seems involved in the regulation of the stress response. Angiotensin agents may also exert anti-inflammatory effects,” the investigators explained. “Dysregulation of intracellular calcium is evident in depression, including receptor-regulated calcium signaling.”

In contrast, beta-blockers have been associated with increased risk of depression in some but not all studies, according to the investigators. They maintained that some clinicians avoid these agents in patients with a history of mood disorders.

In attempting to account for the variability within drug classes regarding protection and lack of protection against depression, the investigators speculated that differences in pharmacologic properties, such as relative lipophilicity or anti-inflammatory effect, might be important.

Despite the large amount of data, William B. White, MD, professor emeritus at the Calhoun Cardiology Center, University of Connecticut, Farmington, is not convinced.

“In observational studies, even those with very large samples sizes, bias and confounding are hard to extricate with controls and propensity-score matching,” Dr. White said. From his perspective, the protective effects of some but not all drugs within a class “give one the impression that the findings are likely random.”

A member of the editorial board of the journal in which this study appeared, Dr. White said he was not involved in the review of the manuscript. Ultimately, he believed that the results are difficult to interpret.

“For example, there is no plausible rationale for why 2 of the 16 ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers or 4 of the 15 beta-blockers or 3 of the 10 calcium-channel blockers would reduce depression while the others in the class would have no effect,” he said.

Despite the investigators’ conclusion that these data should drive drug choice for patients at risk of depression, “I would say the results of this analysis would not lead me to alter clinical practice,” Dr. White added.

According to the principal investigator of the study, Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DSc, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen, many variables affect choice of antihypertensive drug. However, the depression risk is elevated in patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease and hypertension.

When risk of a mood disorder is a concern, use of one of the nine drugs associated with protection from depression should be considered, “especially in patients at increased risk of developing depression, including patients with prior depression or anxiety and patients with a family history of depression,” he and his coinvestigators concluded.

However, Dr. Kessing said in an interview that the data do not help with individual treatment choices. “We do not compare different antihypertensives against each other due to the risk of confounding by indications, so, no, it is not reasonable to consider relative risk among specific agents.”

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest involving this topic.

SOURCE: Kessing LV et al. Hypertension. 2020 Aug 24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15605.

FROM HYPERTENSION

e-Interview With CHEST President-Elect Steven Q. Simpson, MD, FCCP

CHEST President-Elect Steven Q. Simpson, MD, FCCP, is Professor of Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Kansas. He is also senior advisor to the Solving Sepsis initiative of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

As we greet our new incoming CHEST President, we asked him for a few thoughts about his upcoming presidential year. He kindly offered these responses:

What would you like to accomplish as President of CHEST?

This is an interesting question, because a global pandemic and other developments in our world dictate that our organizational goals must adapt to a landscape that has shifted in recent months. My goals as President are somewhat different from what I stated when I ran for the office.

1. First, I will build on the efforts of my predecessors to ensure that CHEST is an inclusive and anti-racist organization. All CHEST members must have equal opportunities within our organization to advance their lives and their careers, regardless of race, ethnicity, sex, or gender. My goal is to examine our structures for participation and advancement to positions of leadership in the organization and to evaluate our educational and research offerings, all with the purpose of discovering and remedying places where we have been blind to our own systematic bias. Further, CHEST must advocate for and lead others to advocate for equality, for equal access to medical care, and for policies that promote them. We must be leaders in this arena, through both our voice and our actions.

2. We will build on CHEST’s new initiative to support the wellness of our members and to help us all perform at our best, day in and day out. I hope for our newly established Wellness Center to become a frequent stop for all CHEST members, myself included, to help us to sustain ourselves through the pandemic and beyond.