User login

The Importance of Emotional Intelligence When Leading in a Time of Crisis

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created innumerable challenges on scales both global and personal while straining health systems and their personnel. Hospitalists and hospital medicine groups are experiencing unique burdens as they confront the pandemic on the frontlines. Hospital medicine groups are being challenged by the rapid operational changes necessary in preparing for and caring for patients with COVID-19. These challenges include drafting new diagnostic and management algorithms, establishing and enacting policies on personal protective equipment (PPE) and patient and provider testing, modifying staffing protocols including deploying staff to new roles or integrating non-hospitalists into hospital medicine roles, and developing capacity for patient surges1—all in the setting of uncertainty about how the pandemic may affect individual hospitals or health systems and how long these repercussions may last. In this perspective, we describe key lessons we have learned in leading our hospital medicine group during the COVID-19 pandemic: how to apply emotional intelligence to proactively address the emotional effects of the crisis.

LEARNING FROM EARLY MISSTEPS

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the evolving knowledge of the disease process, changing national and local public health guidelines, and instability of the PPE supply chain necessitated rapid change. This pace no longer allowed for our typical time frame of weeks to months for implementation of large-scale operational changes; instead, it demanded adaptation in hours to days. We operated under a strategy of developing new workflows and policies that were logical and reflected the best available information at the time.

For instance, our hospital medicine service cared for some of the earliest-identified COVID-19 patients in the United States in early February 2020. Our initial operational plan for caring for patients with COVID-19 involved grouping these patients on a limited number of direct-care hospitalist teams. The advantages of this approach, which benefitted from low numbers of initial patients, were clear: consolidation of clinical and operational knowledge (including optimal PPE practices) in a few individuals, streamlining communication with infectious diseases specialists and public health departments, and requiring change on only a couple of teams while allowing others to continue their usual workflow. However, we soon learned that providers caring for COVID-19 patients were experiencing an onslaught of negative emotions: fear of contracting the virus themselves or carrying it home to infect loved ones, anxiety of not understanding the clinical disease or having treatments to offer, resentment of having been randomly assigned to the team that would care for these patients, and loneliness of being a sole provider experiencing these emotions. We found ourselves in the position of managing these emotional responses reactively.

APPLYING EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE TO LEADING IN A CRISIS

To reduce the distress experienced by our hospitalists and to lead more effectively, we realized the need to proactively address the emotional effects that the pandemic was having. Several authors who have written about valuable leadership lessons during this time have noted the importance of acknowledging the emotional tolls of such a crisis and creating venues for hospitalists to share their experiences.1-4 However, solely adding “wellness” as a checklist item for leaders to address fails to capture the nuances of the complex human emotions that hospitalists may endure at this time and how these emotions influence frontline hospitalists’ responses to operational changes. It is critically important for hospital medicine leaders to employ emotional intelligence, defined as “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.”5-7 Integrating emotional intelligence allows hospital medicine leaders to anticipate, identify, articulate, and manage the emotional responses to necessary changes and stresses that occur during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

As we applied principles of emotional intelligence to our leadership response to the COVID crisis, we found the following seven techniques effective (Appendix Table):

1. ASK. Leaders should ask individual hospitalists “How are you feeling?” instead of “How are you doing?” or “How can I help?” This question may feel too intimate for some, or leaders may worry that the question feels patronizing; however, in our experience, hospitalists respond positively to this prompt, welcome the opportunity to communicate their feelings, and value being heard. Moreover, when hospitalists feel overwhelmed, they may not be able to determine what help they do or do not need. By understanding the emotions of frontline hospitalists, leaders may be better able to address those emotions directly, find solutions to problems, and anticipate reactions to future policies.4

2. SHARE. Leaders should model what they ask of frontline hospitalists and share their own feelings, even if they are experiencing mixed or negative emotions. For instance, a leader who is feeling saddened about the death of a patient can begin a meeting by sharing this sentiment. By allowing themselves to display vulnerability, leaders demonstrate courage and promote a culture of openness, honesty, and mutual trust.

3. INITIATE. Leaders should embrace difficult conversations and be transparent about uncertainty, although they may not have the answers and may need to take local responsibility for consequences of decisions made externally, such as those made by the health system or government. Confronting difficult discussions and being transparent about “unknowns” provides acknowledgement, reassurance, and shared experience that expresses to the hospitalist group that, while the future may be unsettled, they will face it together.

4. ANTICIPATE. Leaders should anticipate the emotional responses to operational changes while designing them and rolling them out. While negative emotions may heavily outweigh positive emotions in times of crisis, we have also found that harnessing positive emotions when designing operational initiatives can assist with successful implementation. For example, by surveying our hospitalists, we found that many felt enthusiastic about caring for patients with COVID-19, curious about new skill sets, and passionate about helping in a time of crisis. By generating a list of these hospitalists up front, we were able to preferentially staff COVID-19 teams with providers who were eager to care for those patients and, thereby, minimize anxiety among those who were more apprehensive.

5. ENCOURAGE. Leaders should provide time and space (including virtually) for hospitalists to discuss their emotions.8 We found that creating multiple layers of opportunity for expression allows for engagement with a wider range of hospitalists, some of whom may be reluctant to share feelings openly or to a group, whereas others may enjoy the opportunity to reveal their feelings publicly. These varied venues for emotional expression may range from brief individual check-ins to open “office hours” to dedicated meetings such as “Hospitalist Town Halls.” For instance, spending the first few minutes of a meeting with a smaller group by encouraging each participant to share something personal can build community and mutual understanding, as well as cue leaders in to where participants may be on the emotional landscape.

6. NURTURE. Beyond inviting the expression of emotions, leaders should ensure that hospitalists have access to more formal systems of support, especially for hospitalists who may be experiencing more intense negative emotions. Support may be provided through unit- or team-based debriefing sessions, health-system sponsored support programs, or individual counseling sessions.4,8

7. APPRECIATE. Leaders should deliberately foster gratitude by sincerely and frequently expressing their appreciation. Because expressing gratitude builds resiliency,9 cultivating a culture of gratitude may bolster resilience in the entire hospital medicine group. Opportunities for thankfulness abound as hospitalists volunteer for extra shifts, cover for ill colleagues, participate in new working groups and task forces, and sacrifice their personal safety on the front lines. We often incorporate statements of appreciation into one-on-one conversations with hospitalists, during operational and divisional meetings, and in email. We also built gratitude expressions into the daily work on the Respiratory Isolation Unit at our hospital via daily interdisciplinary huddles for frontline providers to share their experiences and emotions. During huddles, providers are asked to pair negative emotions with suggestions for improvement and to share a moment of gratitude. This helps to engender a spirit of camaraderie, shared mission, and collective optimism.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists are experiencing a wide range of emotions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospital medicine leaders must have strategies to understand the emotions providers are experiencing. Being aware of and acknowledging these emotions up front can help leaders plan and implement the operational changes necessary to manage the crisis. Because our health system and city have fortunately been spared the worst of the pandemic so far without large volumes of patients with COVID-19, we recognize that the strategies above may be challenging for leaders in overwhelmed health systems. However, we hope that leaders at all levels can apply the lessons we have learned: to ask hospitalists how they are feeling, share their own feelings, initiate difficult conversations when needed, anticipate the emotional effects of operational changes, encourage expressions of emotion in multiple venues, nurture hospitalists who need more formal support, and appreciate frontline hospitalists. While the emotional needs of hospitalists will undoubtedly change over time as the pandemic evolves, we suspect that these strategies will continue to be important over the coming weeks, months, and longer as we settle into the postpandemic world.

1. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

2. Garg M, Wray CM. Hospital medicine management in the time of COVID-19: preparing for a sprint and a marathon. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):305-307. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3427

3. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis : lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

4. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Published online April 7, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5893

5. Mintz LJ, Stoller JK. A systematic review of physician leadership and emotional intelligence. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):21-31. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-13-00012.1

6. Goleman D, Boyatzis R. Emotional intelligence has 12 elements. Which do you need to work on? Harvard Business Review. February 6, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://hbr.org/2017/02/emotional-intelligence-has-12-elements-which-do-you-need-to-work-on

7. Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers. 1990;9(3):185-211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

8. Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1642

9. Kopans D. How to evaluate, manage, and strengthen your resilience. Harvard Business Review. June 14, 2016. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://hbr.org/2016/06/how-to-evaluate-manage-and-strengthen-your-resilience

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created innumerable challenges on scales both global and personal while straining health systems and their personnel. Hospitalists and hospital medicine groups are experiencing unique burdens as they confront the pandemic on the frontlines. Hospital medicine groups are being challenged by the rapid operational changes necessary in preparing for and caring for patients with COVID-19. These challenges include drafting new diagnostic and management algorithms, establishing and enacting policies on personal protective equipment (PPE) and patient and provider testing, modifying staffing protocols including deploying staff to new roles or integrating non-hospitalists into hospital medicine roles, and developing capacity for patient surges1—all in the setting of uncertainty about how the pandemic may affect individual hospitals or health systems and how long these repercussions may last. In this perspective, we describe key lessons we have learned in leading our hospital medicine group during the COVID-19 pandemic: how to apply emotional intelligence to proactively address the emotional effects of the crisis.

LEARNING FROM EARLY MISSTEPS

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the evolving knowledge of the disease process, changing national and local public health guidelines, and instability of the PPE supply chain necessitated rapid change. This pace no longer allowed for our typical time frame of weeks to months for implementation of large-scale operational changes; instead, it demanded adaptation in hours to days. We operated under a strategy of developing new workflows and policies that were logical and reflected the best available information at the time.

For instance, our hospital medicine service cared for some of the earliest-identified COVID-19 patients in the United States in early February 2020. Our initial operational plan for caring for patients with COVID-19 involved grouping these patients on a limited number of direct-care hospitalist teams. The advantages of this approach, which benefitted from low numbers of initial patients, were clear: consolidation of clinical and operational knowledge (including optimal PPE practices) in a few individuals, streamlining communication with infectious diseases specialists and public health departments, and requiring change on only a couple of teams while allowing others to continue their usual workflow. However, we soon learned that providers caring for COVID-19 patients were experiencing an onslaught of negative emotions: fear of contracting the virus themselves or carrying it home to infect loved ones, anxiety of not understanding the clinical disease or having treatments to offer, resentment of having been randomly assigned to the team that would care for these patients, and loneliness of being a sole provider experiencing these emotions. We found ourselves in the position of managing these emotional responses reactively.

APPLYING EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE TO LEADING IN A CRISIS

To reduce the distress experienced by our hospitalists and to lead more effectively, we realized the need to proactively address the emotional effects that the pandemic was having. Several authors who have written about valuable leadership lessons during this time have noted the importance of acknowledging the emotional tolls of such a crisis and creating venues for hospitalists to share their experiences.1-4 However, solely adding “wellness” as a checklist item for leaders to address fails to capture the nuances of the complex human emotions that hospitalists may endure at this time and how these emotions influence frontline hospitalists’ responses to operational changes. It is critically important for hospital medicine leaders to employ emotional intelligence, defined as “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.”5-7 Integrating emotional intelligence allows hospital medicine leaders to anticipate, identify, articulate, and manage the emotional responses to necessary changes and stresses that occur during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

As we applied principles of emotional intelligence to our leadership response to the COVID crisis, we found the following seven techniques effective (Appendix Table):

1. ASK. Leaders should ask individual hospitalists “How are you feeling?” instead of “How are you doing?” or “How can I help?” This question may feel too intimate for some, or leaders may worry that the question feels patronizing; however, in our experience, hospitalists respond positively to this prompt, welcome the opportunity to communicate their feelings, and value being heard. Moreover, when hospitalists feel overwhelmed, they may not be able to determine what help they do or do not need. By understanding the emotions of frontline hospitalists, leaders may be better able to address those emotions directly, find solutions to problems, and anticipate reactions to future policies.4

2. SHARE. Leaders should model what they ask of frontline hospitalists and share their own feelings, even if they are experiencing mixed or negative emotions. For instance, a leader who is feeling saddened about the death of a patient can begin a meeting by sharing this sentiment. By allowing themselves to display vulnerability, leaders demonstrate courage and promote a culture of openness, honesty, and mutual trust.

3. INITIATE. Leaders should embrace difficult conversations and be transparent about uncertainty, although they may not have the answers and may need to take local responsibility for consequences of decisions made externally, such as those made by the health system or government. Confronting difficult discussions and being transparent about “unknowns” provides acknowledgement, reassurance, and shared experience that expresses to the hospitalist group that, while the future may be unsettled, they will face it together.

4. ANTICIPATE. Leaders should anticipate the emotional responses to operational changes while designing them and rolling them out. While negative emotions may heavily outweigh positive emotions in times of crisis, we have also found that harnessing positive emotions when designing operational initiatives can assist with successful implementation. For example, by surveying our hospitalists, we found that many felt enthusiastic about caring for patients with COVID-19, curious about new skill sets, and passionate about helping in a time of crisis. By generating a list of these hospitalists up front, we were able to preferentially staff COVID-19 teams with providers who were eager to care for those patients and, thereby, minimize anxiety among those who were more apprehensive.

5. ENCOURAGE. Leaders should provide time and space (including virtually) for hospitalists to discuss their emotions.8 We found that creating multiple layers of opportunity for expression allows for engagement with a wider range of hospitalists, some of whom may be reluctant to share feelings openly or to a group, whereas others may enjoy the opportunity to reveal their feelings publicly. These varied venues for emotional expression may range from brief individual check-ins to open “office hours” to dedicated meetings such as “Hospitalist Town Halls.” For instance, spending the first few minutes of a meeting with a smaller group by encouraging each participant to share something personal can build community and mutual understanding, as well as cue leaders in to where participants may be on the emotional landscape.

6. NURTURE. Beyond inviting the expression of emotions, leaders should ensure that hospitalists have access to more formal systems of support, especially for hospitalists who may be experiencing more intense negative emotions. Support may be provided through unit- or team-based debriefing sessions, health-system sponsored support programs, or individual counseling sessions.4,8

7. APPRECIATE. Leaders should deliberately foster gratitude by sincerely and frequently expressing their appreciation. Because expressing gratitude builds resiliency,9 cultivating a culture of gratitude may bolster resilience in the entire hospital medicine group. Opportunities for thankfulness abound as hospitalists volunteer for extra shifts, cover for ill colleagues, participate in new working groups and task forces, and sacrifice their personal safety on the front lines. We often incorporate statements of appreciation into one-on-one conversations with hospitalists, during operational and divisional meetings, and in email. We also built gratitude expressions into the daily work on the Respiratory Isolation Unit at our hospital via daily interdisciplinary huddles for frontline providers to share their experiences and emotions. During huddles, providers are asked to pair negative emotions with suggestions for improvement and to share a moment of gratitude. This helps to engender a spirit of camaraderie, shared mission, and collective optimism.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists are experiencing a wide range of emotions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospital medicine leaders must have strategies to understand the emotions providers are experiencing. Being aware of and acknowledging these emotions up front can help leaders plan and implement the operational changes necessary to manage the crisis. Because our health system and city have fortunately been spared the worst of the pandemic so far without large volumes of patients with COVID-19, we recognize that the strategies above may be challenging for leaders in overwhelmed health systems. However, we hope that leaders at all levels can apply the lessons we have learned: to ask hospitalists how they are feeling, share their own feelings, initiate difficult conversations when needed, anticipate the emotional effects of operational changes, encourage expressions of emotion in multiple venues, nurture hospitalists who need more formal support, and appreciate frontline hospitalists. While the emotional needs of hospitalists will undoubtedly change over time as the pandemic evolves, we suspect that these strategies will continue to be important over the coming weeks, months, and longer as we settle into the postpandemic world.

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created innumerable challenges on scales both global and personal while straining health systems and their personnel. Hospitalists and hospital medicine groups are experiencing unique burdens as they confront the pandemic on the frontlines. Hospital medicine groups are being challenged by the rapid operational changes necessary in preparing for and caring for patients with COVID-19. These challenges include drafting new diagnostic and management algorithms, establishing and enacting policies on personal protective equipment (PPE) and patient and provider testing, modifying staffing protocols including deploying staff to new roles or integrating non-hospitalists into hospital medicine roles, and developing capacity for patient surges1—all in the setting of uncertainty about how the pandemic may affect individual hospitals or health systems and how long these repercussions may last. In this perspective, we describe key lessons we have learned in leading our hospital medicine group during the COVID-19 pandemic: how to apply emotional intelligence to proactively address the emotional effects of the crisis.

LEARNING FROM EARLY MISSTEPS

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the evolving knowledge of the disease process, changing national and local public health guidelines, and instability of the PPE supply chain necessitated rapid change. This pace no longer allowed for our typical time frame of weeks to months for implementation of large-scale operational changes; instead, it demanded adaptation in hours to days. We operated under a strategy of developing new workflows and policies that were logical and reflected the best available information at the time.

For instance, our hospital medicine service cared for some of the earliest-identified COVID-19 patients in the United States in early February 2020. Our initial operational plan for caring for patients with COVID-19 involved grouping these patients on a limited number of direct-care hospitalist teams. The advantages of this approach, which benefitted from low numbers of initial patients, were clear: consolidation of clinical and operational knowledge (including optimal PPE practices) in a few individuals, streamlining communication with infectious diseases specialists and public health departments, and requiring change on only a couple of teams while allowing others to continue their usual workflow. However, we soon learned that providers caring for COVID-19 patients were experiencing an onslaught of negative emotions: fear of contracting the virus themselves or carrying it home to infect loved ones, anxiety of not understanding the clinical disease or having treatments to offer, resentment of having been randomly assigned to the team that would care for these patients, and loneliness of being a sole provider experiencing these emotions. We found ourselves in the position of managing these emotional responses reactively.

APPLYING EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE TO LEADING IN A CRISIS

To reduce the distress experienced by our hospitalists and to lead more effectively, we realized the need to proactively address the emotional effects that the pandemic was having. Several authors who have written about valuable leadership lessons during this time have noted the importance of acknowledging the emotional tolls of such a crisis and creating venues for hospitalists to share their experiences.1-4 However, solely adding “wellness” as a checklist item for leaders to address fails to capture the nuances of the complex human emotions that hospitalists may endure at this time and how these emotions influence frontline hospitalists’ responses to operational changes. It is critically important for hospital medicine leaders to employ emotional intelligence, defined as “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.”5-7 Integrating emotional intelligence allows hospital medicine leaders to anticipate, identify, articulate, and manage the emotional responses to necessary changes and stresses that occur during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

As we applied principles of emotional intelligence to our leadership response to the COVID crisis, we found the following seven techniques effective (Appendix Table):

1. ASK. Leaders should ask individual hospitalists “How are you feeling?” instead of “How are you doing?” or “How can I help?” This question may feel too intimate for some, or leaders may worry that the question feels patronizing; however, in our experience, hospitalists respond positively to this prompt, welcome the opportunity to communicate their feelings, and value being heard. Moreover, when hospitalists feel overwhelmed, they may not be able to determine what help they do or do not need. By understanding the emotions of frontline hospitalists, leaders may be better able to address those emotions directly, find solutions to problems, and anticipate reactions to future policies.4

2. SHARE. Leaders should model what they ask of frontline hospitalists and share their own feelings, even if they are experiencing mixed or negative emotions. For instance, a leader who is feeling saddened about the death of a patient can begin a meeting by sharing this sentiment. By allowing themselves to display vulnerability, leaders demonstrate courage and promote a culture of openness, honesty, and mutual trust.

3. INITIATE. Leaders should embrace difficult conversations and be transparent about uncertainty, although they may not have the answers and may need to take local responsibility for consequences of decisions made externally, such as those made by the health system or government. Confronting difficult discussions and being transparent about “unknowns” provides acknowledgement, reassurance, and shared experience that expresses to the hospitalist group that, while the future may be unsettled, they will face it together.

4. ANTICIPATE. Leaders should anticipate the emotional responses to operational changes while designing them and rolling them out. While negative emotions may heavily outweigh positive emotions in times of crisis, we have also found that harnessing positive emotions when designing operational initiatives can assist with successful implementation. For example, by surveying our hospitalists, we found that many felt enthusiastic about caring for patients with COVID-19, curious about new skill sets, and passionate about helping in a time of crisis. By generating a list of these hospitalists up front, we were able to preferentially staff COVID-19 teams with providers who were eager to care for those patients and, thereby, minimize anxiety among those who were more apprehensive.

5. ENCOURAGE. Leaders should provide time and space (including virtually) for hospitalists to discuss their emotions.8 We found that creating multiple layers of opportunity for expression allows for engagement with a wider range of hospitalists, some of whom may be reluctant to share feelings openly or to a group, whereas others may enjoy the opportunity to reveal their feelings publicly. These varied venues for emotional expression may range from brief individual check-ins to open “office hours” to dedicated meetings such as “Hospitalist Town Halls.” For instance, spending the first few minutes of a meeting with a smaller group by encouraging each participant to share something personal can build community and mutual understanding, as well as cue leaders in to where participants may be on the emotional landscape.

6. NURTURE. Beyond inviting the expression of emotions, leaders should ensure that hospitalists have access to more formal systems of support, especially for hospitalists who may be experiencing more intense negative emotions. Support may be provided through unit- or team-based debriefing sessions, health-system sponsored support programs, or individual counseling sessions.4,8

7. APPRECIATE. Leaders should deliberately foster gratitude by sincerely and frequently expressing their appreciation. Because expressing gratitude builds resiliency,9 cultivating a culture of gratitude may bolster resilience in the entire hospital medicine group. Opportunities for thankfulness abound as hospitalists volunteer for extra shifts, cover for ill colleagues, participate in new working groups and task forces, and sacrifice their personal safety on the front lines. We often incorporate statements of appreciation into one-on-one conversations with hospitalists, during operational and divisional meetings, and in email. We also built gratitude expressions into the daily work on the Respiratory Isolation Unit at our hospital via daily interdisciplinary huddles for frontline providers to share their experiences and emotions. During huddles, providers are asked to pair negative emotions with suggestions for improvement and to share a moment of gratitude. This helps to engender a spirit of camaraderie, shared mission, and collective optimism.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists are experiencing a wide range of emotions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospital medicine leaders must have strategies to understand the emotions providers are experiencing. Being aware of and acknowledging these emotions up front can help leaders plan and implement the operational changes necessary to manage the crisis. Because our health system and city have fortunately been spared the worst of the pandemic so far without large volumes of patients with COVID-19, we recognize that the strategies above may be challenging for leaders in overwhelmed health systems. However, we hope that leaders at all levels can apply the lessons we have learned: to ask hospitalists how they are feeling, share their own feelings, initiate difficult conversations when needed, anticipate the emotional effects of operational changes, encourage expressions of emotion in multiple venues, nurture hospitalists who need more formal support, and appreciate frontline hospitalists. While the emotional needs of hospitalists will undoubtedly change over time as the pandemic evolves, we suspect that these strategies will continue to be important over the coming weeks, months, and longer as we settle into the postpandemic world.

1. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

2. Garg M, Wray CM. Hospital medicine management in the time of COVID-19: preparing for a sprint and a marathon. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):305-307. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3427

3. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis : lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

4. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Published online April 7, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5893

5. Mintz LJ, Stoller JK. A systematic review of physician leadership and emotional intelligence. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):21-31. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-13-00012.1

6. Goleman D, Boyatzis R. Emotional intelligence has 12 elements. Which do you need to work on? Harvard Business Review. February 6, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://hbr.org/2017/02/emotional-intelligence-has-12-elements-which-do-you-need-to-work-on

7. Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers. 1990;9(3):185-211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

8. Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1642

9. Kopans D. How to evaluate, manage, and strengthen your resilience. Harvard Business Review. June 14, 2016. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://hbr.org/2016/06/how-to-evaluate-manage-and-strengthen-your-resilience

1. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

2. Garg M, Wray CM. Hospital medicine management in the time of COVID-19: preparing for a sprint and a marathon. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):305-307. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3427

3. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis : lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

4. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Published online April 7, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5893

5. Mintz LJ, Stoller JK. A systematic review of physician leadership and emotional intelligence. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):21-31. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-13-00012.1

6. Goleman D, Boyatzis R. Emotional intelligence has 12 elements. Which do you need to work on? Harvard Business Review. February 6, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://hbr.org/2017/02/emotional-intelligence-has-12-elements-which-do-you-need-to-work-on

7. Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers. 1990;9(3):185-211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

8. Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1642

9. Kopans D. How to evaluate, manage, and strengthen your resilience. Harvard Business Review. June 14, 2016. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://hbr.org/2016/06/how-to-evaluate-manage-and-strengthen-your-resilience

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

FDA Regulation of Predictive Clinical Decision-Support Tools: What Does It Mean for Hospitals?

Recent experiences in the transportation industry highlight the importance of getting right the regulation of decision-support systems in high-stakes environments. Two tragic plane crashes resulted in 346 deaths and were deemed, in part, to be related to a cockpit alert system that overwhelmed pilots with multiple notifications.1 Similarly, a driverless car struck and killed a pedestrian in the street, in part because the car was not programmed to look for humans outside of a crosswalk.2 These two bellwether events offer poignant lessons for the healthcare industry in which human lives also depend on decision-support systems.

Clinical decision-support (CDS) systems are computerized applications, often embedded in an electronic health record (EHR), that provide information to clinicians to inform care. Although CDS systems have been used for many years,3 they have never been subjected to any enforcement of formal testing requirements. However, a draft guidance document released in 2019 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outlined new directions for the regulation of CDS systems.4 Although the FDA has thus far focused regulatory efforts on predictive systems developed by private manufacturers,5,6 this new document provides examples of software that would require regulation for CDS systems that hospitals are already using. Thus, this new guidance raises critical questions—will hospitals themselves be evaluated like private manufacturers, be exempted from federal regulation, or require their own specialized regulation? The FDA has not yet clarified its approach to hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, which leaves open numerous possibilities in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

Although the FDA has officially regulated CDS systems under section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), only recently has the FDA begun to sketch the shape of its regulatory efforts. This trend to actually regulate CDS systems began with the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) that amended the definition of software systems that qualify as medical devices and outlined criteria under which a system may be exempt from FDA oversight. For example, regulation would not apply to systems that support “population health” or a “healthy lifestyle” or to ones that qualify as “electronic patient records” as long as they do not “interpret or analyze” data within them.7 Following the rapid proliferation of many machine learning and other predictive technologies with medical applications, the FDA began the voluntary Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program in 2017. Through this program, the FDA selected nine companies from more than 100 applicants and certified them across five domains of excellence. Notably, the Pre-Cert Program currently allows for certification of software manufacturers themselves and does not approve or test actual software devices directly. This regulatory pathway will eventually allow manufacturers to apply under a modified premarket review process for individual software as a medical device (SaMD) that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. In the meantime, however, many hospitals have developed and deployed their own predictive CDS systems that cross the boundaries into the FDA’s purview and, indeed, do “interpret or analyze” data for real-time EHR alerts, population health management, and other applications.

Regulatory oversight for hospitals could provide quality or safety standards where currently there are none. However, such regulations could also interfere with existing local care practices, hinder rapid development of new CDS systems, and may be perceived as interfering in hospital operations. With the current enthusiasm for AI-based technologies and the concurrent lack of evidence to suggest their effectiveness in practice, regulation could also prompt necessary scrutiny of potential harms of CDS systems, an area with even less evidence. At the same time, CDS developers—private or hospital based—may be able to avoid regulation for some devices with well-placed disclaimers about the intended use of the CDS, one of the FDA criteria for determining the degree of oversight. If the FDA were to regulate hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, there are several unanswered questions to consider so that such regulations have their intended impact.

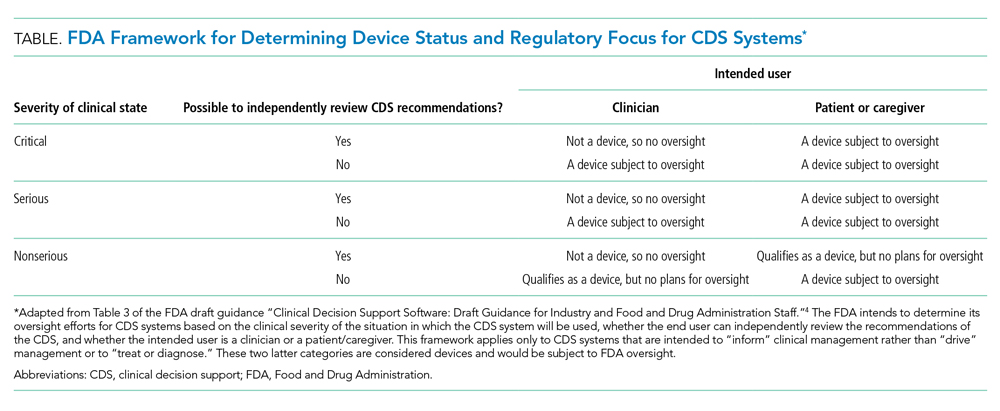

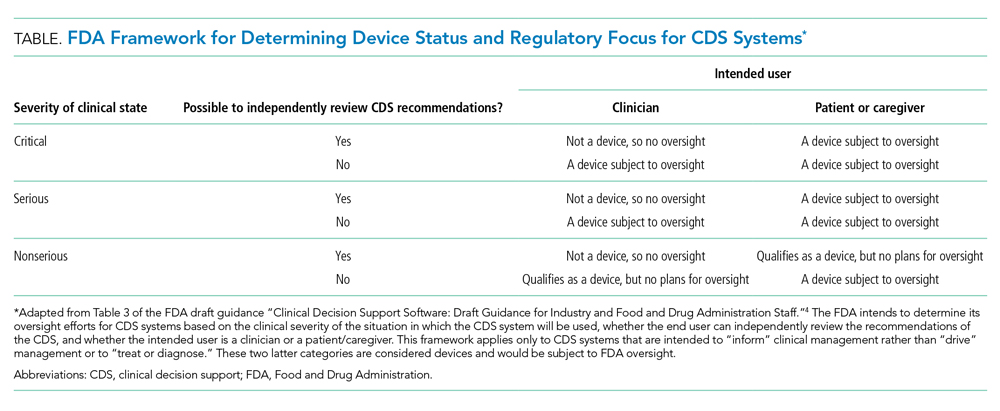

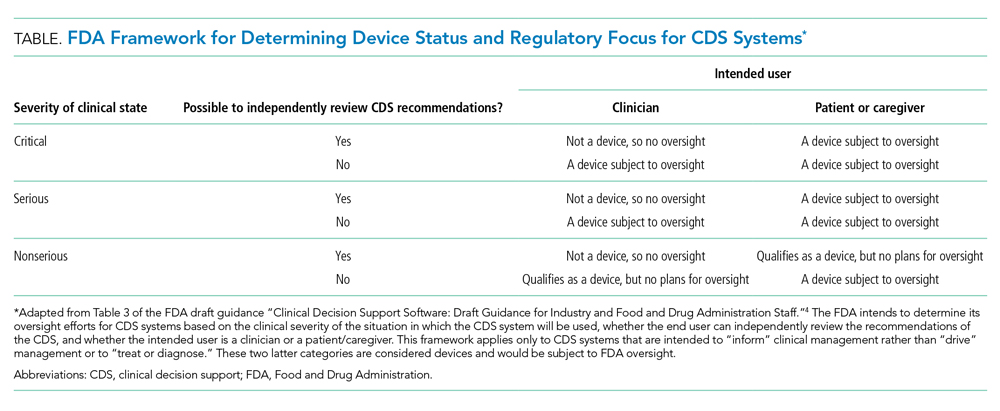

First, does the FDA intend to regulate hospitals and hospital-developed software at all? The framework for determining whether a CDS system will be regulated depends on the severity of the clinical scenario, the ability to independently evaluate the model output, and the intended user (Table). Notably, many types of CDS systems that would require regulation under this framework are already commonplace. For example, the FDA intends to regulate software that “identifies patients who may exhibit signs of opioid addiction,” a scenario similar to prediction models already developed at academic hospitals.8 The FDA also plans to regulate a software device even if it is not a CDS system if it is “intended to generate an alarm or an alert to notify a caregiver of a life-threatening condition, such as stroke, and the caregiver relies primarily on this alarm or alert to make a treatment decision.” Although there are no published reports of stroke-specific early warning systems in use, analogous nonspecific and sepsis-specific early warning systems to prompt urgent clinical care have been deployed by hospitals directly9 and developed for embedding in commercial EHRs.10 Hospitals need clarification on the FDA’s regulatory intentions for such CDS systems. FDA regulation of hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems would fill a critical oversight need and potentially strengthen processes to improve safety and effectiveness. But burdensome regulations may also restrain hospitals from tackling complex problems in medicine for which they are uniquely suited.

Such a regulatory environment may be especially prohibitive for safety-net hospitals that could find themselves at a disadvantage in developing their own CDS systems relative to large academic medical centers that are typically endowed with greater resources. Additionally, CDS systems developed at academic medical centers may not generalize well to populations in the community setting, which could further deepen disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies. For example, racial bias in treatment and referral patterns could bias training labels for CDS systems focused on population health management.11 Similarly, the composition of patient skin color in one population may distort predictions of a model in another with a different distribution of skin color, even when the primary outcome of a prediction model is gender.12 Additional regulatory steps may apply for models that are adapted to new populations or recalibrated across locations and time.13 Until there is more data on the clinical impact of such CDS systems, it is unknown how potential differences in evaluation and approval would actually affect clinical outcomes.

Second, would hospitals be eligible for the Pre-Cert program, and if so, would they be held to the same standards as a private technology manufacturer? The domains of excellence required for precertification approval such as “patient safety,” “clinical responsibility,” and “proactive culture” are aligned with the efforts of hospitals that are already overseen and accredited by organizations like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Nurses Credentialing Center. There is limited motivation for the FDA to be in the business of regulating these aspects of hospital functions. However, while domains like “product quality” and “cybersecurity” may be less familiar to some hospitals, these existing credentialing bodies may be better suited than the FDA to set and enforce standards for hospitals. In contrast, private manufacturers may have deep expertise in these latter domains. Therefore, as with public-private partnerships for the development of predictive radiology applications,14 synergies between hospitals and manufacturers may also prove useful for obtaining approvals in a competitive marketplace. Simultaneously, such collaborations would continue to raise questions about conflicts of interest and data privacy.

Finally, regardless of how the FDA will regulate hospitals, what will become of predictive CDS systems that fall outside of the FDA’s scope? Hospitals will continue to find themselves in the position of self-regulation without clear guidance. Although the FDA suggests that developers of unregulated CDS systems still follow best practices for software validation and cybersecurity, existing guidance documents in these domains do not cover the full range of concerns relevant to the development, deployment, and oversight of AI-based CDS systems in the clinical domain. Nor do most hospitals have the infrastructure or expertise to oversee their own CDS systems. Disparate recommendations for development, training, and oversight of AI-based medical systems have emerged but have yet to be endorsed by a federal regulatory body or become part of the hospital accreditation process.15 Optimal local oversight would require a collaboration between clinical experts, hospital operations leaders, statisticians, data scientists, and ethics experts to ensure effectiveness, safety, and fairness.

Hospitals will remain at the forefront of developing and implementing predictive CDS systems. The proposed FDA regulatory framework would mark an important step toward realizing benefit from such systems, but the FDA needs to clarify the requirements for hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems to ensure reasonable standards that account for their differences from private software manufacturers. Should the FDA choose to focus regulation on private manufacturers only, hospitals leaders may both feel more empowered to develop their own local CDS tools and feel more comfortable buying CDS systems from vendors that have been precertified. This strategy would provide an optimal balance of assurance and flexibility while maintaining quality standards that ultimately improve patient care.

1. Sumwalt RL III, Landsbert B, Homendy J. Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf

2. Becic E, Zych N, Ivarsson J. Vehicle Automation Report. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://dms.ntsb.gov/public/62500-62999/62978/629713.pdf

3. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

4. Clinical Decision Support Software: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download

5. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17216

6. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

7. Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/109622/download

8. Lo-Ciganic W-H, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

9. Smith MEB, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1454-1465. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201403-102oc

10. WAVE Clinical Platform 510(k) Premarket Notification. Food and Drug Administration. January 4, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K171056

11. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

12. Buolamwini J, Gebru T. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proc Machine Learning Res. 2018;81:1-15.

13. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Food and Drug Administration. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FDA-2019-N-1185-0001&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

14. Allen B. The role of the FDA in ensuring the safety and efficacy of artificial intelligence software and devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(2):208-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.007

15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

Recent experiences in the transportation industry highlight the importance of getting right the regulation of decision-support systems in high-stakes environments. Two tragic plane crashes resulted in 346 deaths and were deemed, in part, to be related to a cockpit alert system that overwhelmed pilots with multiple notifications.1 Similarly, a driverless car struck and killed a pedestrian in the street, in part because the car was not programmed to look for humans outside of a crosswalk.2 These two bellwether events offer poignant lessons for the healthcare industry in which human lives also depend on decision-support systems.

Clinical decision-support (CDS) systems are computerized applications, often embedded in an electronic health record (EHR), that provide information to clinicians to inform care. Although CDS systems have been used for many years,3 they have never been subjected to any enforcement of formal testing requirements. However, a draft guidance document released in 2019 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outlined new directions for the regulation of CDS systems.4 Although the FDA has thus far focused regulatory efforts on predictive systems developed by private manufacturers,5,6 this new document provides examples of software that would require regulation for CDS systems that hospitals are already using. Thus, this new guidance raises critical questions—will hospitals themselves be evaluated like private manufacturers, be exempted from federal regulation, or require their own specialized regulation? The FDA has not yet clarified its approach to hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, which leaves open numerous possibilities in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

Although the FDA has officially regulated CDS systems under section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), only recently has the FDA begun to sketch the shape of its regulatory efforts. This trend to actually regulate CDS systems began with the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) that amended the definition of software systems that qualify as medical devices and outlined criteria under which a system may be exempt from FDA oversight. For example, regulation would not apply to systems that support “population health” or a “healthy lifestyle” or to ones that qualify as “electronic patient records” as long as they do not “interpret or analyze” data within them.7 Following the rapid proliferation of many machine learning and other predictive technologies with medical applications, the FDA began the voluntary Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program in 2017. Through this program, the FDA selected nine companies from more than 100 applicants and certified them across five domains of excellence. Notably, the Pre-Cert Program currently allows for certification of software manufacturers themselves and does not approve or test actual software devices directly. This regulatory pathway will eventually allow manufacturers to apply under a modified premarket review process for individual software as a medical device (SaMD) that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. In the meantime, however, many hospitals have developed and deployed their own predictive CDS systems that cross the boundaries into the FDA’s purview and, indeed, do “interpret or analyze” data for real-time EHR alerts, population health management, and other applications.

Regulatory oversight for hospitals could provide quality or safety standards where currently there are none. However, such regulations could also interfere with existing local care practices, hinder rapid development of new CDS systems, and may be perceived as interfering in hospital operations. With the current enthusiasm for AI-based technologies and the concurrent lack of evidence to suggest their effectiveness in practice, regulation could also prompt necessary scrutiny of potential harms of CDS systems, an area with even less evidence. At the same time, CDS developers—private or hospital based—may be able to avoid regulation for some devices with well-placed disclaimers about the intended use of the CDS, one of the FDA criteria for determining the degree of oversight. If the FDA were to regulate hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, there are several unanswered questions to consider so that such regulations have their intended impact.

First, does the FDA intend to regulate hospitals and hospital-developed software at all? The framework for determining whether a CDS system will be regulated depends on the severity of the clinical scenario, the ability to independently evaluate the model output, and the intended user (Table). Notably, many types of CDS systems that would require regulation under this framework are already commonplace. For example, the FDA intends to regulate software that “identifies patients who may exhibit signs of opioid addiction,” a scenario similar to prediction models already developed at academic hospitals.8 The FDA also plans to regulate a software device even if it is not a CDS system if it is “intended to generate an alarm or an alert to notify a caregiver of a life-threatening condition, such as stroke, and the caregiver relies primarily on this alarm or alert to make a treatment decision.” Although there are no published reports of stroke-specific early warning systems in use, analogous nonspecific and sepsis-specific early warning systems to prompt urgent clinical care have been deployed by hospitals directly9 and developed for embedding in commercial EHRs.10 Hospitals need clarification on the FDA’s regulatory intentions for such CDS systems. FDA regulation of hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems would fill a critical oversight need and potentially strengthen processes to improve safety and effectiveness. But burdensome regulations may also restrain hospitals from tackling complex problems in medicine for which they are uniquely suited.

Such a regulatory environment may be especially prohibitive for safety-net hospitals that could find themselves at a disadvantage in developing their own CDS systems relative to large academic medical centers that are typically endowed with greater resources. Additionally, CDS systems developed at academic medical centers may not generalize well to populations in the community setting, which could further deepen disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies. For example, racial bias in treatment and referral patterns could bias training labels for CDS systems focused on population health management.11 Similarly, the composition of patient skin color in one population may distort predictions of a model in another with a different distribution of skin color, even when the primary outcome of a prediction model is gender.12 Additional regulatory steps may apply for models that are adapted to new populations or recalibrated across locations and time.13 Until there is more data on the clinical impact of such CDS systems, it is unknown how potential differences in evaluation and approval would actually affect clinical outcomes.

Second, would hospitals be eligible for the Pre-Cert program, and if so, would they be held to the same standards as a private technology manufacturer? The domains of excellence required for precertification approval such as “patient safety,” “clinical responsibility,” and “proactive culture” are aligned with the efforts of hospitals that are already overseen and accredited by organizations like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Nurses Credentialing Center. There is limited motivation for the FDA to be in the business of regulating these aspects of hospital functions. However, while domains like “product quality” and “cybersecurity” may be less familiar to some hospitals, these existing credentialing bodies may be better suited than the FDA to set and enforce standards for hospitals. In contrast, private manufacturers may have deep expertise in these latter domains. Therefore, as with public-private partnerships for the development of predictive radiology applications,14 synergies between hospitals and manufacturers may also prove useful for obtaining approvals in a competitive marketplace. Simultaneously, such collaborations would continue to raise questions about conflicts of interest and data privacy.

Finally, regardless of how the FDA will regulate hospitals, what will become of predictive CDS systems that fall outside of the FDA’s scope? Hospitals will continue to find themselves in the position of self-regulation without clear guidance. Although the FDA suggests that developers of unregulated CDS systems still follow best practices for software validation and cybersecurity, existing guidance documents in these domains do not cover the full range of concerns relevant to the development, deployment, and oversight of AI-based CDS systems in the clinical domain. Nor do most hospitals have the infrastructure or expertise to oversee their own CDS systems. Disparate recommendations for development, training, and oversight of AI-based medical systems have emerged but have yet to be endorsed by a federal regulatory body or become part of the hospital accreditation process.15 Optimal local oversight would require a collaboration between clinical experts, hospital operations leaders, statisticians, data scientists, and ethics experts to ensure effectiveness, safety, and fairness.

Hospitals will remain at the forefront of developing and implementing predictive CDS systems. The proposed FDA regulatory framework would mark an important step toward realizing benefit from such systems, but the FDA needs to clarify the requirements for hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems to ensure reasonable standards that account for their differences from private software manufacturers. Should the FDA choose to focus regulation on private manufacturers only, hospitals leaders may both feel more empowered to develop their own local CDS tools and feel more comfortable buying CDS systems from vendors that have been precertified. This strategy would provide an optimal balance of assurance and flexibility while maintaining quality standards that ultimately improve patient care.

Recent experiences in the transportation industry highlight the importance of getting right the regulation of decision-support systems in high-stakes environments. Two tragic plane crashes resulted in 346 deaths and were deemed, in part, to be related to a cockpit alert system that overwhelmed pilots with multiple notifications.1 Similarly, a driverless car struck and killed a pedestrian in the street, in part because the car was not programmed to look for humans outside of a crosswalk.2 These two bellwether events offer poignant lessons for the healthcare industry in which human lives also depend on decision-support systems.

Clinical decision-support (CDS) systems are computerized applications, often embedded in an electronic health record (EHR), that provide information to clinicians to inform care. Although CDS systems have been used for many years,3 they have never been subjected to any enforcement of formal testing requirements. However, a draft guidance document released in 2019 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outlined new directions for the regulation of CDS systems.4 Although the FDA has thus far focused regulatory efforts on predictive systems developed by private manufacturers,5,6 this new document provides examples of software that would require regulation for CDS systems that hospitals are already using. Thus, this new guidance raises critical questions—will hospitals themselves be evaluated like private manufacturers, be exempted from federal regulation, or require their own specialized regulation? The FDA has not yet clarified its approach to hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, which leaves open numerous possibilities in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

Although the FDA has officially regulated CDS systems under section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), only recently has the FDA begun to sketch the shape of its regulatory efforts. This trend to actually regulate CDS systems began with the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) that amended the definition of software systems that qualify as medical devices and outlined criteria under which a system may be exempt from FDA oversight. For example, regulation would not apply to systems that support “population health” or a “healthy lifestyle” or to ones that qualify as “electronic patient records” as long as they do not “interpret or analyze” data within them.7 Following the rapid proliferation of many machine learning and other predictive technologies with medical applications, the FDA began the voluntary Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program in 2017. Through this program, the FDA selected nine companies from more than 100 applicants and certified them across five domains of excellence. Notably, the Pre-Cert Program currently allows for certification of software manufacturers themselves and does not approve or test actual software devices directly. This regulatory pathway will eventually allow manufacturers to apply under a modified premarket review process for individual software as a medical device (SaMD) that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. In the meantime, however, many hospitals have developed and deployed their own predictive CDS systems that cross the boundaries into the FDA’s purview and, indeed, do “interpret or analyze” data for real-time EHR alerts, population health management, and other applications.

Regulatory oversight for hospitals could provide quality or safety standards where currently there are none. However, such regulations could also interfere with existing local care practices, hinder rapid development of new CDS systems, and may be perceived as interfering in hospital operations. With the current enthusiasm for AI-based technologies and the concurrent lack of evidence to suggest their effectiveness in practice, regulation could also prompt necessary scrutiny of potential harms of CDS systems, an area with even less evidence. At the same time, CDS developers—private or hospital based—may be able to avoid regulation for some devices with well-placed disclaimers about the intended use of the CDS, one of the FDA criteria for determining the degree of oversight. If the FDA were to regulate hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, there are several unanswered questions to consider so that such regulations have their intended impact.

First, does the FDA intend to regulate hospitals and hospital-developed software at all? The framework for determining whether a CDS system will be regulated depends on the severity of the clinical scenario, the ability to independently evaluate the model output, and the intended user (Table). Notably, many types of CDS systems that would require regulation under this framework are already commonplace. For example, the FDA intends to regulate software that “identifies patients who may exhibit signs of opioid addiction,” a scenario similar to prediction models already developed at academic hospitals.8 The FDA also plans to regulate a software device even if it is not a CDS system if it is “intended to generate an alarm or an alert to notify a caregiver of a life-threatening condition, such as stroke, and the caregiver relies primarily on this alarm or alert to make a treatment decision.” Although there are no published reports of stroke-specific early warning systems in use, analogous nonspecific and sepsis-specific early warning systems to prompt urgent clinical care have been deployed by hospitals directly9 and developed for embedding in commercial EHRs.10 Hospitals need clarification on the FDA’s regulatory intentions for such CDS systems. FDA regulation of hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems would fill a critical oversight need and potentially strengthen processes to improve safety and effectiveness. But burdensome regulations may also restrain hospitals from tackling complex problems in medicine for which they are uniquely suited.

Such a regulatory environment may be especially prohibitive for safety-net hospitals that could find themselves at a disadvantage in developing their own CDS systems relative to large academic medical centers that are typically endowed with greater resources. Additionally, CDS systems developed at academic medical centers may not generalize well to populations in the community setting, which could further deepen disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies. For example, racial bias in treatment and referral patterns could bias training labels for CDS systems focused on population health management.11 Similarly, the composition of patient skin color in one population may distort predictions of a model in another with a different distribution of skin color, even when the primary outcome of a prediction model is gender.12 Additional regulatory steps may apply for models that are adapted to new populations or recalibrated across locations and time.13 Until there is more data on the clinical impact of such CDS systems, it is unknown how potential differences in evaluation and approval would actually affect clinical outcomes.

Second, would hospitals be eligible for the Pre-Cert program, and if so, would they be held to the same standards as a private technology manufacturer? The domains of excellence required for precertification approval such as “patient safety,” “clinical responsibility,” and “proactive culture” are aligned with the efforts of hospitals that are already overseen and accredited by organizations like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Nurses Credentialing Center. There is limited motivation for the FDA to be in the business of regulating these aspects of hospital functions. However, while domains like “product quality” and “cybersecurity” may be less familiar to some hospitals, these existing credentialing bodies may be better suited than the FDA to set and enforce standards for hospitals. In contrast, private manufacturers may have deep expertise in these latter domains. Therefore, as with public-private partnerships for the development of predictive radiology applications,14 synergies between hospitals and manufacturers may also prove useful for obtaining approvals in a competitive marketplace. Simultaneously, such collaborations would continue to raise questions about conflicts of interest and data privacy.

Finally, regardless of how the FDA will regulate hospitals, what will become of predictive CDS systems that fall outside of the FDA’s scope? Hospitals will continue to find themselves in the position of self-regulation without clear guidance. Although the FDA suggests that developers of unregulated CDS systems still follow best practices for software validation and cybersecurity, existing guidance documents in these domains do not cover the full range of concerns relevant to the development, deployment, and oversight of AI-based CDS systems in the clinical domain. Nor do most hospitals have the infrastructure or expertise to oversee their own CDS systems. Disparate recommendations for development, training, and oversight of AI-based medical systems have emerged but have yet to be endorsed by a federal regulatory body or become part of the hospital accreditation process.15 Optimal local oversight would require a collaboration between clinical experts, hospital operations leaders, statisticians, data scientists, and ethics experts to ensure effectiveness, safety, and fairness.

Hospitals will remain at the forefront of developing and implementing predictive CDS systems. The proposed FDA regulatory framework would mark an important step toward realizing benefit from such systems, but the FDA needs to clarify the requirements for hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems to ensure reasonable standards that account for their differences from private software manufacturers. Should the FDA choose to focus regulation on private manufacturers only, hospitals leaders may both feel more empowered to develop their own local CDS tools and feel more comfortable buying CDS systems from vendors that have been precertified. This strategy would provide an optimal balance of assurance and flexibility while maintaining quality standards that ultimately improve patient care.

1. Sumwalt RL III, Landsbert B, Homendy J. Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf

2. Becic E, Zych N, Ivarsson J. Vehicle Automation Report. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://dms.ntsb.gov/public/62500-62999/62978/629713.pdf

3. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

4. Clinical Decision Support Software: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download

5. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17216

6. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

7. Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/109622/download

8. Lo-Ciganic W-H, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

9. Smith MEB, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1454-1465. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201403-102oc

10. WAVE Clinical Platform 510(k) Premarket Notification. Food and Drug Administration. January 4, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K171056

11. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

12. Buolamwini J, Gebru T. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proc Machine Learning Res. 2018;81:1-15.

13. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Food and Drug Administration. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FDA-2019-N-1185-0001&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

14. Allen B. The role of the FDA in ensuring the safety and efficacy of artificial intelligence software and devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(2):208-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.007

15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

1. Sumwalt RL III, Landsbert B, Homendy J. Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf

2. Becic E, Zych N, Ivarsson J. Vehicle Automation Report. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://dms.ntsb.gov/public/62500-62999/62978/629713.pdf

3. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

4. Clinical Decision Support Software: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download

5. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17216

6. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

7. Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/109622/download

8. Lo-Ciganic W-H, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

9. Smith MEB, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1454-1465. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201403-102oc

10. WAVE Clinical Platform 510(k) Premarket Notification. Food and Drug Administration. January 4, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K171056

11. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

12. Buolamwini J, Gebru T. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proc Machine Learning Res. 2018;81:1-15.

13. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Food and Drug Administration. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FDA-2019-N-1185-0001&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

14. Allen B. The role of the FDA in ensuring the safety and efficacy of artificial intelligence software and devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(2):208-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.007

15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Multiplying the Impact of Opioid Settlement Funds by Investing in Primary Prevention

There is growing momentum to hold drug manufacturers accountable for the more than 400,000 US opioid overdose deaths that have occurred since 1999.1 As state lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors wind their way through the legal system, hospitals—which may benefit from settlement funds—have been paying close attention. Recently, former Governor John Kasich (R-Ohio), West Virginia University president E. Gordon Gee, and America’s Essential Hospitals argued that adequately compensating hospitals for the costs of being on the crisis’ “front lines” requires prioritizing them as settlement fund recipients.2